Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.9 no.2 Cape Town Mai./Ago. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.14426/ahmr.v9i2.1242

ARTICLES

Framing Chinese Treatment of Africans in Guangzhou: A Study of Nigerian and Ghanaian Online Newspapers

Abdul-Gafar Tobi Oshodi

Department of Political Science, Lagos State University, Nigeria. Email: oshoditobi@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The treatment of Africans in Guangzhou, China in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic - here referred to as the "Guangzhou episode" - generated strong criticisms and made news headlines within and outside Africa. This paper analyzes the reportage of the episode in four online African newspapers: two each from Nigeria and Ghana. Specifically, it sheds light on how the episode was framed, comparing coverage between both countries. Using a discourse analysis that prioritizes language, source, and focus, the paper demonstrates that while Western media were important influences and sources for the newspapers, the African migrants' experiences in the episode were largely framed within (ahistorical) victimhood. Yet the idea of "African" migrants had a noticeable Nigerian dimension.

Keywords: African migrants, Guangzhou episode, media, victimhood, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

The growing Africa-China relationship has intensified migration from both sides. There are about 500,000 Africans in China - although some consider this figure to be lower, around 16,000 - and 1-2 million Chinese citizens in Africa (Amoah et al., 2020; Bodomo, 2020; Yan, 2020; Cissé, 2021). The number of African students studying in China has also increased. Not only do students form the second largest group of African diaspora in China (Li, 2018), but that category in China also surpassed those studying in the United States and Britain (Makundi, 2020). In 2018, for instance, China was the most popular destination for African students after France (Makundi, 2020). In the case of African students in China, there is the "intersection of educational and trading-led migration" (Ho, 2018), making a simplistic categorization of students as non-migrants problematic. As Africa-China relationships develop, however, the media dimension is increasingly becoming crucial (Li, 2017; van Staden and Wu, 2018). Although academic interest in this dimension appears slow-paced (Wekesa, 2017a, 2017b) when compared to other aspects, the literature on the former has nonetheless increased in recent times. Not only has the media become an arena for highlighting the perceived role(s) of China in Africa (Umejei, 2017), but it also represents a space for criticism and engagement. Thus, just as there have been copious reports on Chinese investment (and soft power) in Africa, there have been episodes of negative reports on China (Mudasiru and Oshodi, 2020). Even the much-reported Chinese-built African Union (AU) secretariat headquarters, a gift from Beijing to African governments in 2012, had its share of negative news in 2018 when reports emerged that the Chinese had been spying on Africans in the building (Dahir, 2018) - an allegation first made by the French newspaper, Le Monde, but that quickly spread across media outlets. Similarly, reports about the treatment of Africans in Guangzhou, a port city in southern China - hereafter referred to as the "Guangzhou episode" (Oshodi, 2021) - during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic generated even more negative reportage for China. Not only did the Guangzhou episode force Beijing to respond to questions about anti-African racism, but it also challenged officious Chinese statements on Africa-China relations. This paper focuses on the Guangzhou episode, especially on how it was framed by Africa-based media.

Guangzhou has a population of 18.7 million (Global Times, 2023). The official figure of 20,000 Africans in 2009 reportedly reduced to an estimated 16,000 in 2016 and 4,553 registered Africans by April 2020 (Marsh, 2016; Kirton, 2020). Two reasons can explain the decrease: frequent visa checks on Africans by the local government and the registration of traders (Jin et al., 2023). Nonetheless, the Guangzhou episode - a coinage used here to represent the reports on the treatment of Africans in the city and how African media, migrants, politicians, civil societies, and China responded -merits attention for four interrelated reasons. First, it represents a blight on a cordial Africa-China relationship, one that generated significant coverage in traditional and new media. Second, it happened in a unique context of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, when movement was restricted and work was done online in many places. The impact of and response to the pandemic varied across countries - from the ones that closed their borders for months to the ones that witnessed high fatalities. China, for example, did not relax its COVID-19 restrictions until December 2022. By focusing on online reports, this paper offers some insight into how Africa-China migration is mediated and framed through the media. Third, while it raises the ghost of racism and xenophobia against African migrants in China (see Sautman, 1994; Cheng, 2011) that generated several media reports, the Guangzhou episode offers a useful example of African media's agency. In this context, the media functioned as "a point of engagement" (Oshodi, 2015) when African governments were slow, weak, unable, and reluctant to respond to China. Although African governments summoned Chinese ambassadors and petitioned Beijing during the episode, there were instances when the media criticized both the Nigerian and the Chinese governments for their handling of the treatment of Africans in Guangzhou. An example is The Guardians editorial against the Nigerian Foreign Affairs minister's explanation that the Guangzhou episode was caused by miscommunication (see Onochie, 2020). Fourth, the Guangzhou episode merits attention because of its potential to promote anti-Chinese sentiments and reprisal attacks on Chinese migrants in Africa (see Oluwasegun and Akowe, 2020; Tarlue, 2020a; Oshodi, 2021).

To shed a deeper light on the Guangzhou episode, this paper analyzes reports from Nigerian and Ghanaian newspapers. Specifically, it sets out to achieve two objectives: (i) to understand how the four African newspapers framed the episode, and (ii) to ascertain convergence - or divergence - between both countries. The paper is significant because it sheds light on the complexities and dynamism of the African media in their coverage of Africa-China relations. Given that it is through the media that many Africans gain knowledge of what happened in Guangzhou, the paper offers a lens to understand the frames through which the African media present to their audience what was arguably the most challenging period in Africa-China relations during the COVID-19 period. Structurally, the rest of this paper is divided into four parts. Section two locates the researcher in the research and discusses the methodology. Section three revisits the discourse about the news media as a framer and reviews the literature on the mediascape of Africa-China relations. Section four discusses the case of the selected newspapers. Section five is the conclusion.

NOTES ON POSITIONALITY AND METHODOLOGY

Although uncommon in the literature on Africa-China relations, before discussing my methodology, it is important to situate myself in the research. I do not approach the research as a tabula rasa. Aside from being an African who has never been to China but followed the reportage of the Guangzhou episode on local and international news platforms, my views on the episode have been publicly expressed in The Conversation (Oshodi, 2020). Yet, my views on the Guangzhou episode are not unchangeable. I can respond to new ideas and data. Since 2009, I have situated my understanding of "China in Africa" within a broader context of events happening within China itself, within Africa and beyond. I am also a former journalist, an experience that contributes to my (re)imagination of "China in Africa" beyond a dominant thin perspective that focuses on events within - and not outside of - Africa. Specifically, since working on a postdoctoral project on China in African newspapers, I have been advancing a thick conceptualization of "China in Africa." A thin conceptualization of "China in Africa" focuses on a description of Chinese activities in Africa without attempting to connect it to events beyond Africa. Conversely, a thick conceptualization situates it within a broader international setting wherein students of the subject aim to situate both China and Africa beyond their respective geographies. Thus, the fact that an event that happened within China generated protests and actions within and outside Africa gives impetus to the need to interrogate Africa-China relations beyond the geography of continental Africa or China itself. By interrogating the Guangzhou episode through the lens of Africa-based newspapers, therefore, this paper fits into my thick conceptualization of "China in Africa."

Although there are significant differences between traditional and new media, some traditional newspapers operate online (having a website and social media presence), straddling between supposed traditional modes and modernity. All the newspapers selected for this study (The Guardian and The Nation in Nigeria and the Graphic and the Daily Guide in Ghana) fall into this category. Starting as traditional media selling hard copies, they do not only have online versions but have incorporated audio-visuals like The Nations videos, "GuardianTV" "Graphic Video Gallery," and "Guide Radio." Although not all stories in the print copies are available online (and vice versa), online versions have the advantage of being accessible, shareable, and read across national borders in a timely manner.

The Graphic and the Daily Guide are based in Ghana's capital city, Accra. The Nation and The Guardian are based in Lagos, Nigeria's commercial center and former capital. Nonetheless, while there are several other newspapers in Ghana and Nigeria, the four newspapers are purposively selected for three reasons. First, they have websites and published at least seven online reports on the Guangzhou episode during the four months of study (8 April - 8 August 2020). Based on a preliminary survey of newspapers in the two countries, seven stories on the Guangzhou episode were published. Second, two of the newspapers were selected because of their widespread and relatively longstanding existence (i.e., the Graphic was established in 1950 and The Guardian in 1983). Third, the study selected the Daily Guide and The Nation because they are owned by members of ruling parties. The Daily Guide was established in 1984 and owned by the Blay family, with links to the New Patriotic Party that won presidential elections in 2016 and 2020. The Nation was established in 2006 by Mr. Bola Tinubu, a leading member of the ruling All Progressive Congress that won Nigeria's 2015 and 2019 presidential election.

I accessed data for this study - reports of the Guangzhou episode - from the newspapers' websites and accessed reports through the search function on websites. Using the key location of the episode, the word that was searched is "Guangzhou." I carefully read the reports generated by the search and analyzed their contents manually. I read the headlines to ascertain frequently used words. But beyond the search function, selection of reports for analysis was also guided by two processes. First, I limited the search to reports between 8 April 2020, when the news of the Guangzhou episode broke in many news outlets, and 8 August 2020. I based my decision to select 8 August 2020 as the end date on the view that four months was a sufficient time to understand how the selected newspapers framed the Guangzhou episode. This decision was guided by the view that the life spans of news stories in media outfits are not necessarily long and often compete with many other news items. Second, after generating several search results from "Guangzhou," I then carefully read each report to ensure that they were relevant and connected to the Guangzhou episode.

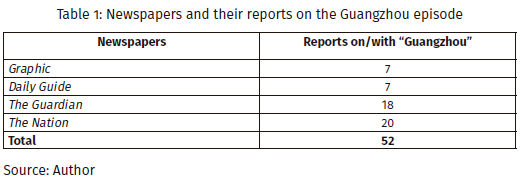

As illustrated in Table 1, the search identified 52 relevant reports on the Guangzhou episode. Given the small number, I analyzed all the reports by reading and coding them by hand. I analyzed the reports using discourse analysis that consider "the social, political, historical and intertextual contexts which go beyond analysis of the language within texts" (Baker et al., 2008: 273-274). To this end, not only would the key frame - i.e., victimhood - be highlighted and analyzed but would be linked to the source question.

AFRICA-CHINA MEDIASCAPE AND FRAMING

The media occupies an important position in migration. It mediates the narrative by highlighting, gate-keeping, or sustaining discussions. While there are other factors that shape perceptions of migration and the experiences of migrants, the role of the media in intergroup relations must not be underestimated. In addition to signposting government's actions such as deportation of migrants (Peil, 1974; Aremu, 2013; Akinyoade, 2015), elsewhere there is more direct evidence of the connection between media reportage and the outbreaks of violent intergroup conflict, as in Rwanda (Forges, 2007). Yet the role of the media remains Janus-headed. Even in places where they contributed to conflict, as in Rwanda, the media also plays a positive role in intergroup relations and building tolerance (Paluck, 2007). Some reports have highlighted the role of the media in framing migration in Europe (Berry et al., 2015; CCME and WACC, 2017; EJN, 2017). As one report notes: "Media narratives continue to shape public opinion, but it also reveals how in all countries journalism is a distorting lens as much as a magnifying glass" (EJN, 2017: 7).

As in migration reportage, newspaper reports on Africa-China relations can mediate the dominant narrative of state actors, offering new perspectives. For instance, while former Nigerian President, Olusegun Obasanjo, notes in his autobiography that, "Although some Marxist socialists in 'Biafra' appealed to China for help, we have no tangible evidence of any material support or assistance to Biafra by the Chinese" (Obasanjo, 2015: 219), newspaper reports during the war suggested that Biafran forces had an "arms deal with China" (Daily Graphic, 1968: 1). Media reports have also emerged as important sources of data for understanding Africa-China encounters. The Media-Based Data Collection (MBDC), for example, offers "a comprehensive database of Chinese development finance flows to Africa from 2000-2011" (Strange et al., 2013: 2).

At this juncture, it is important to stress that the Africa-China relations mediascape remains a contested arena where "China in Africa" can be seen from differing lenses. Thus, while Africa-China relations have attracted significant academic and media interest in the last 20 years, details of the relations have been marred in several unknowns, creating room for rumors and myths (Yan and Sautman, 2012). This has perhaps prompted some to view the field as some sort of salad where non-Chinese views that "know nothing about either China or Africa" on the one hand and "Chinese scholarly commentary" that "tends to observe Party lines closely" on the other hand (Chan, 2013: 7) survive and flourish in their respective spaces. Sometimes there is competition in these views. The "real China in Africa" may therefore vary across spaces. If Chan's description of the field is correct (in spite of his own troublesome reference to a "Dark Continent" instead of "Africa" in his book's title), to therefore understand the coverage of Africa-China relations is to accommodate the role - and in some instances, goals - of the media in the framing of stories. Li's work, Mediatized China-Africa Relations, captures the media dimension of knowing, positing that the "role of media and mass communication should never be underestimated, especially in our understanding of China in Africa" (2017: 5). Yet the media is itself not immune from the broader contestations about what the true picture is. One expert offers this picture: "The Chinese press painted a consistently rosy picture of friendship and mutual benefit. ... Journalists in Africa and in the West were much more skeptical" (Bräutigam, 2009: 3). Given this situation, observers must be continuously wary of the media as an objective source and reflection of the state of Africa-China relations. In other words, we must be wary of how "news" is framed in a context where information does not always emanate from news sources. This study illustrates in the section on the source question that news about Africa-China relations in African media can be influenced by Western media reportage and frames.

The aforementioned influence on the "news" in Africa is not limited to Western media. China understands the importance of the media in its relationship with Africa. For instance, Li (2017: 9) notes that "Chinese media houses in Africa ... act as a mouthpiece of the Chinese party-state and boost China's image internationally, an objective that has to be implemented through the media organizations' own decision-making processes." The Chinese media presence in Africa predates the official recognition of China by many African countries in the 1970s. Xinhua News Agency bureaus were present in more than 25 countries in the 1960s and 1970s and China Radio International (CRI) was the third largest international broadcaster in sub-Saharan Africa in the mid-1960s (Li, 2017). It is against this background that "mediatization" - i.e., "a process in which the mechanisms of media involvement and media evolvement serve to shape, reinforce, refute or challenge public understandings, just as in other mega-processes like modernization, globalization and industrialization" (Li, 2017: 12) - becomes useful in understanding the Western and Chinese influence in Africa's mediascape. This paper, however, adopts framing as a conceptual framework for its analysis. This is because it allows the study to account for the specific choices of the sampled newspapers and how they reported the Guangzhou episode.

Like many concepts in the social sciences, framing does not have a universally accepted definition and has been used inconsistently (de Vreese, 2005: 51). As McQuail (2003: 454) puts it, "The idea of framing is an attractive one, but how it works as an effect process is less easy to account for." Nonetheless, "a frame is an emphasis in salience of different aspects of a topic" (de Vreese, 2005: 53, original emphasis). Thus, framing has been described as the "construction of social reality" (Scheufele, 1999: 104) and "a way of giving some interpretation to isolated items of fact" - an action that "is almost unavoidable for journalists" and "in so doing departing from pure 'objectivity' and introducing some (albeit unintended) bias" (McQuail, 2003: 343). Framing, it must be stressed, goes beyond the journalist or the media outfit. It entails "both presenting and comprehending news" - which means that it also encapsulates the individual level (Scheufele, 1999). In any case, communication, as the dynamic process that it is, entails frame-building and frame-setting (de Vreese, 2005). Frame-building relates to how frames emerge as influenced by factors internal and external to journalism and manifests in the text. Frame-setting represents "the interplay between media frames and audience predispositions;" it "refers to the interaction between media frames and individuals' prior knowledge and predispositions" (de Vreese, 2005: 51-52). As already hinted in Li's work, "China in Africa" is a mediated space. The mediascape is particularly made more complex by the differing control and ownership regulations that operate in China and Africa.

Western media, with or without their bias and frames, interject this duality. Thus, although "the entry of Chinese media into Africa is an integral part of Chinese media spreading tentacles globally" (Wekesa, 2017b: 11), the media ecology on the continent remains contested. Bräutigam appears to present this contestation in her seminal work, The Dragon's Gift:

Journalists have given us quick sketches, but these impressions are often very partial, and sometimes, even in the best newspapers, surprisingly wrong. Chinese journalists do not enjoy freedom of the press. Other journalists are more balanced in their presentation, but lack the background to distinguish between foreign aid and the broader range of economic cooperation activities sponsored by China's developmental state. Such a differentiation is important if we are going to understand how China operates as a donor, and how Chinese aid and economic cooperation affect development (Bräutigam, 2009: 20).

The differentiation that Bräutigam talks about accentuates "frame-building" and "frame-setting." This can become more pronounced when there are contestations and real interests in shaping what is real as in the Guangzhou episode. On the one hand, Chinese media aiming to fight off the negative reports countered the narrative of maltreatment of Africans and called out the United States and Western media for polluting Africa-China relations. On the other hand, African and indeed global media reported otherwise, often adhering to the line that Africans were maltreated by their Chinese host in Guangzhou. But the rigid bifurcation of Chinese and nonChinese media, as in the Guangzhou episode, must also not be taken as the ultimate divisions in the unfolding context. There are indeed overlapping relationships that could have implications. One writer drew attention to this, noting the influence of China on private media in Africa wherein they hold stakes or invite local journalists to "special Beijing-sponsored seminars" (Essa, 2018). It is in this context that this appraisal of newspapers as an arena of contestation and the Guangzhou episode is located. This serves as an opportunity to investigate the investigator: the media.

FRAMING THE GUANGZHOU EPISODE

In this section, I offer a discussion of the framing of the Guangzhou episode in the four newspapers. As highlighted in Table 1, the selected Nigerian newspapers (The Guardian and The Nation) had more reports - and for a longer period - than the Ghanaian ones (the Graphic and the Daily Guide). One reason that might have accounted for this is the "Nigerian dimension" as discussed in this section. This dimension provides more incentive to the Nigerian newspapers to keep their main audience (i.e., Nigerians) informed relative to their Ghanaian counterparts. Indeed, only a Nigerian newspaper published an editorial on the Guangzhou episode. Nonetheless, there are important similarities and differences across the four newspapers. For instance, while reports generally suggest a geographical definition of "Africans" to mean migrants from continental Africa, one newspaper, The Guardian, reports the United States's advice to its African-American citizens to avoid Guangzhou (Adekanye, 2020). This section discusses the framing of the Guangzhou episode under three main subsections: the source question, victimhood, and the Nigerian dimension.

The source question

Media reports have their sources; sources that can determine whose voices are heard, silenced, neglected, or displaced. Journalists frame their stories, but the sources available to them can limit or shape these frames. Thus, a critical understanding of framing requires a careful interrogation of the news sources. This study acknowledges the influence of Western media on reports in the newspapers. For instance, all the African migrants reported on in the Graphic and the Daily Guide were sourced from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Indeed, five of the seven reports in the Daily Guide cited the BBC. Some reports used pictures of Africans on Chinese streets similar to those used in Western media. The first story by Ghana's Graphic entitled "Africans 'evicted from Chinese hotels over Covid-19 fears'" published on 8 April 2020 is credited to the BBC (2020a). On 11 April 2020, the newspaper credited the Cable News Network (CNN) with the story, "Virus fears spark xenophobia in China" that partly read:

CNN interviewed more than two dozen Africans living in Guangzhou many of whom told of the same experiences: being left without a home, being subject to random testing for Covid-19, and being quarantined for 14 days in their homes, despite having no symptoms or contact with known patients (CNN, 2020).

The source of the Graphics first report was the BBC, and the accompanying pictures for the story were also used by the BBC (see BBC, 2020a, 2020c). Like the Graphic, The Guardians first report on the Guangzhou episode quoted Dailymail.co.uk (Guardian, 2020b). The newspaper also credited Agence France-Presse (AFP) for a story entitled "Nigeria says treatment of nationals in China 'unacceptable' " (AFP, 2020b). Interestingly, a similar report was in The Nation but was written by local Nigerian journalists (Ikuomola et al., 2020). That some reports were influenced by the framing of Western media is not in doubt and it is noted in Chinese media. For instance, one Chinese media house describes the situation thus: "Western media have a great influence on many media in African countries and their unbalanced China reports also affect local media's understanding of China" (Global Times, 2020b). The fact that reports were sourced from Western media does not mean that Chinese voices were silenced. With the exception of the Daily Guide, reliance on Western media was not static in the Graphic and in the two Nigerian newspapers. In fact, Chinese media (like Xinhua, Southcn.com, and China Daily) and voices (like Chinese government officials, ambassadors, investors, and activists) were accommodated in reports.

Chinese versions of the Guangzhou episode, however, often viewed it as a result of miscommunication, fake news, conspiracy, or exaggeration (e.g., CGTN, 2020; Global Times, 2020a, 2020b; Reuters, 2020). Some of these views were reflected in the reports of the African newspapers. Chinese media like Xinhua (Adekanye, 2020; Guardian, 2020a) and China News Service (AFP, 2020a) were cited in The Guardian. Again, the fact that the African newspapers cited Western media (as in the preceding paragraph) does not necessarily mean the absence of Chinese voices in such reports. The Guardian offers an example.

A report in The Guardian was credited to AFP, but the same report offered information from a Chinese state-run media source, China News Service, that "businesses and residential compounds "must implement non-discriminatory service ... treat all Chinese and foreigners in Guangdong equally, and firmly oppose any racist or discriminatory speech and behaviour" (AFP, 2020a). Similarly, although sourced from Dailymail.co.uk, the first story in The Guardian on the Guangzhou episode - "Five Nigerians test positive for coronavirus in China" with a rider, "Investigate humiliations of Nigerians in China, FG urged" - credited the Guangzhou Health Commission as a source for the announcement of the infected Nigerians (Guardian, 2020b). Although it published a strong editorial that criticized the treatment of Africans in Guangzhou, The Guardian accommodated Chinese views by publishing a features report written by Chinese ambassador to Nigeria, Zhou Pingjian, entitled "Pandemic: Solidarity and cooperation most potent weapon" (Pingjian, 2020). In his piece, Pingjian articulated the official Chinese position, for instance, that "What happened in Guangdong recently is a similar story like Wuhan, in essence. All the measures taken there aim to fight against the COVID-19, not against any Nigerian, any African, or any foreign national." Similarly, The Nation published a story on the Chinese ambassador's responses (Ikuomola, 2020b). Chinese migrants in Nigeria were also given a voice in reports.

The voices of a diverse group of African stakeholders were reflected in the reports. These included African migrants in China, many of whose names were omitted in reports. It is understandable that mentioning the names of African migrants in China in reports could have unexpected implications for them. The media control in China means that it is risky for African migrants to be publicly identified to be a source of the reports on the mistreatment of Africans in Guangzhou. Hence, Nigerian newspapers that reported the views of migrants sometimes used anonymous labels like "Nigerian businessman," "an insider," or just first names - e.g., "Thiam" or "Denny" - that could make tracing difficult (Guardian, 2020a; Ikuomola et al., 2020). Importantly, giving a voice to migrants provides some nuance. For instance, beyond the general reportage of maltreatment in all the newspapers, The Nation added:

Those who had earlier been quarantined were also said to be included in the new isolation arrangement; a situation which did not go down well with the Nigerians, who were said to have paid $100 per night in the hotel where they were isolated for the 14 days, including that "the new hotel they were moving them to was said to cost $400 per night; an amount they considered to be far too high, especially as they were to pick the bills themselves" (Ikuomola et al., 2020).

Such details about the quarantine were not reported in the other newspapers. The response of the Chinese government to the cost of quarantine was also absent in reports.

Other African voices in reports on the Guangzhou episode included those of foreign affairs ministers, ambassadors, parliamentarians, individuals, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) within and outside Africa. It also included African media. For instance, the Graphic (on 11 April 2020) quoted Nigeria's Vanguard newspapers and Kenya's The Nation (Yeboah, 2020) and it published an interview conducted with Ghana's ambassador to China on Citi FM (Arku, 2020). Similarly, The Nation reported stories from the News Agency of Nigeria (NAN, 2020b). The Ghanaian and Nigerian newspapers, however, differed in terms of how they gave a voice to migrants. Unlike the Ghanaian newspapers that relied on African migrants interviewed by the BBC, the Nigerian newspapers directly reported the views of the migrants in China. Although Ghanaian newspapers referred to Ghanaians as victims in Guangzhou, little mention was made of their views as compared to the Nigerian newspapers.

After its seventh reports on the Guangzhou episode within the study period, it is important to note that the Graphic's next report entitled "China to cancel interest-free loans to African nations" was obtained from a Western media source (BBC, 2020b). Thus, the Graphic started its reportage on the Guangzhou episode with a report from the BBC and moved on to another issue on Africa-China relations from the same international media source. Although this appears to confirm the view about the influence of Western media in Africa (Global Times, 2020b) or "the domineering role played by the BBC, from the colonial era until today" (Serwornoo, 2019: 1371), the real picture, as highlighted above, is more complex, as news sources on the Guangzhou episode are more diverse than limited to Western media like the BBC. African and Chinese sources and voices were also reflected in reports.

Victimhood

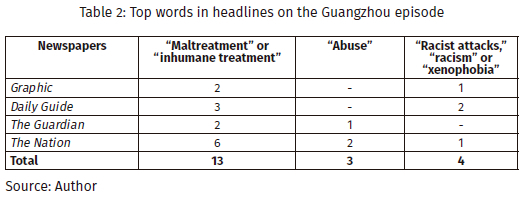

In many instances, African migrants were framed as the victims of the Guangzhou episode. Five important points are worth highlighting in the language of victimhood. First, all the newspapers framed the treatment of African migrants in Guangzhou in negative terms. In the 52 reports, words like "maltreatment," "inhumane treatment," "abuse," "racist attack," "racism," or "xenophobia" were used 20 times. Other words used in headlines to describe the episode included "discrimination," "unacceptable," "victimization," and "humiliating." As illustrated in Table 2, "maltreatment" was the most frequently used words in headlines. It was used 11 times across newspapers. The second point relates to how they framed the "African" victims. Although "Africans" were commonly used, this was interjected with the use of specific African nationalities. "Nigerians" and "Ghanaians" were used in the two Ghanaian newspapers, although references were also made to "Kenyans" in the Graphic, and "Sierra Leonean," "Togolese," "Nigerians," "Beninois," and "Ethiopian" nationals in the Daily Guide. Sometimes, the use of the nationality is emphatic, such as "maltreatment of Africans particularly Ghanaians by Chinese officials in China" (Tarlue, 2020b). "Africans," "Nigerians," "Ugandans," "Guineans," and "South Africans" were identified as victims in the Nigerian newspapers. As noted above, only one newspaper, The Guardian, referred to African-Americans in the Guangzhou episode (Adekanye, 2020). As discussed later, there was more focus on "Nigerians" than other African nationals.

Third, rather than a static one-sided perspective that blames Chinese authorities for the plight of the migrants, the newspapers adopted a fluid approach that tended to adjust to the news source and their priorities at particular points. For instance, on 18 April 2020, about ten days after the news of maltreatment broke, The Nation still reported that African envoys "denounced the manner Chinese authorities in Guangzhou, a city in Guangdong Province, dehumanized Africans who were being unfairly blamed for fresh outbreaks of coronavirus disease in the province" (NAN, 2020a). Indeed, after initial reports that blamed China for the plight of the African migrants in Guangzhou, subsequent reports shifted the blame to fears of COVID-19 spreading in China, Nigerian government and citizens, and largely miscommunication. Reports about the fear of COVID-19 spreading among African communities in China were noticeable in a Graphic report on 16 April 2020. Three days earlier, the Daily Guide reported concerns by local Chinese health officials that there could be a second outbreak after a spike in imported COVID-19 cases. The headlines for the next two reports in the Graphic, which were the last in the study period, emphasized the safety of Ghanaians in China. Beyond the Guangzhou episode, however, a piece in The Nation drew attention to the tendency to "criminalize the disease or stigmatize infected individuals or those presumed to be" - such as Africans in China, Asians in the United States and COVID-19-infected Nigerians in Nigeria (Basikoro, 2020).

Though "miscommunication" was noticeable in views credited to representatives of Nigerian and Ghanaian government and Chinese officials, this was usually absent in African migrants' voices. However, it is important to stress that a shift to other issues was not a repudiation of the language of victimhood. For instance, The Nation and The Guardian ended their coverage on the Guangzhou episode with a report about a group that petitioned the UK Parliament for the "abuse," "racism," and "discriminatory treatment" against Africans in China. Similarly, the last two reports in Ghana's Daily Guide that related to the Guangzhou episode used "maltreatment" and "stigmatization." Interestingly, the voices that highlighted this were those of Ghanaians in Norway and a Member of Parliament in Ghana respectively. They were not those of the Ghanaian or African migrants in Ghana.

Fourth, although victimhood is largely constructed in terms of migrants' reported experiences in Guangzhou, there are instances where the (in)capacity or (in)actions of African leaders were highlighted. Such references are noticeable in the Nigerian newspapers. This is captured in their blaming of the ruling elites for failing to rise to the challenge confronting African (particularly Nigerian) migrants in China. For example, The Nation on 21 April 2020 published an article entitled "China mocks Africa," where the author contends that the "muted responses of the governments of African countries show clearly that they are ill-equipped and indisposed to defend their interests, when confronted by the emerging Chinese hegemony" (Amalu, 2020). Yet African leaders and ambassadors - individually and collectively - responded to the maltreatment of Africans. Nonetheless, The Guardian, in its editorial of 5 May 2020 expressed a stronger criticism of government: "Nigeria that should be aggrieved was initially apologetic on behalf of the 'accused'" (Guardian, 2020c).

Fifth, the victimhood is generally framed as ahistorical. Reports were not linked to past reports of Chinese racism against Africans (Sautman, 1994; Sullivan, 1994; Cheng, 2011) or to more recent reports of racism during Chinese New Year celebration (BBC, 2018; McDonald, 2021). Interestingly, one report that linked the Guangzhou episode to an earlier event was a story credited to CNN, a Western media outfit, in the Graphic that stated: "African residents say local hostility to their presence is nothing new. But when coronavirus cases emerged in the African community this month it served to amplify existing tensions" (CNN, 2020). Although not a news report, one exception to the ahistoricity was The Guardian editorial of 5 May 2020 that stated:

Lest we forget, a recent exhibition of visual arts in China was replete with designs that present Black Africans in comparison with animals of various types. Besides that, this was no art as understood by decent values and universal standards of creativity, we should think that exhibition was disrespectful and despicable (Guardian, 2020c).

Aside from the few exceptions, most reports framed the maltreatment of Africans within the COVID-19 context. This context included reports of COVID-19 spreading within African communities and how that could lead to another wave of spread, implying that some Nigerians failed to quarantine, miscommunication by Chinese authorities, fear of the spread within the Chinese population, and an allegation that a Nigerian who tested positive for COVID-19 attacked a Chinese nurse who tried to stop him from leaving an isolation ward at a Guangzhou hospital (Arku, 2020; CNN, 2020). Although the fear element in Guangzhou is similar to a report in December 1988 where there was an allegation that "African students began a class boycott to protest against accusations that they were AIDS carriers" (Sautman, 1994: 420), no historical connection was made in many of the reports. But a Nigerian dimension was popular in all the newspapers.

The Nigerian dimension

Reports in the newspapers about the Guangzhou episode focused on the treatment of African migrants in China, but this was framed against a noticeable Nigerian backdrop. One of the most detailed reports on the Nigerian dimension in the two Ghanaian newspapers was a 17 April 2020 report in the Graphic entitled "COVID-19: Ghanaians in China safe amid discrimination against Africans" (Arku, 2020). The report is based on Ghana's ambassador to China, Edward Boateng's interview with an Accra-based radio station, Citi FM. The report states that the Guangzhou episode was escalated by the actions of Nigerian migrants (who did not self-quarantine, ate at a popular restaurant, and later tested positive for COVID-19) and by the Nigerian government (that delayed stopping travels to China unlike Ghana that issued an early alert in January). In addition, two days before the Graphics story, The Guardian reported that Nigeria's Foreign Affairs Minister, Geoffrey Onyeama, and the Chinese Ambassador to Nigeria, Zhou Pingjian, emphasized "poor communications" (Onochie, 2020), a frame that became popular across newspapers. Emphasizing poor communication, The Nation quoted Nigeria's foreign minister saying, "If the authorities in Guangzhou had informed the African Consulates in Guangzhou that this was the situation and these were the measures they were putting in place, it could have become a joint effort" (Ikuomola, 2020a). However, The Guardian offered a critique of this argument:

The intolerably weak excuse offered by Foreign Minister Geoffrey Onyeama was that the mistreatment of Nigerians and the attendant strong response to it by a Nigerian embassy official as glaringly captured on video was due to "poor communication." He even advised his fellow Nigerians who were appalled to be objective in assessing such incidents - as if Nigerians were hasty in their reaction to so obvious an appalling incident. But later, wiser counsel prevailed and this minister felt the need to speak up for his country and his countrymen. "We are extremely disappointed with the treatment meted out to our people because we have good relations with the government and people of China" he said, somewhat meekly (Guardian, 2020c).

Given the actions of Nigeria(ns), the Graphic, based on Mr. Edward Boateng's interview, reported that the Guangzhou authorities panicked, and decided "to test all Black Africans regardless of nationality" (Arku, 2020), thus shifting the language of discrimination to one of moral panic on both sides: where Chinese authorities reacted based on the fear of COVID-19 spreading while Nigeria's response was about the morality of discriminating against its citizens in Guangzhou. The moral panic in both the Chinese and the Nigerian governments' voices is also discernible in the Nigerian newspapers' coverage. The Graphics reportorial shift marked the end of its reports on the maltreatment of Africans in China. Indeed, its next report on "Guangzhou" was published two months later, on 16 June 2020 and entitled "COVID-19: Over 600 stranded Ghanaians due home this week" (Annang, 2020). Conversely, the Nigerian newspapers continued with their reports on the Guangzhou episode after their Ghanaian counterparts stopped. In fact, while the Daily Guide's and the Graphics reports on the Chinese treatment of Africans in Guangzhou ended on 12 April 2020 and 17 April 2020 respectively, The Guardian still reported on the Nigerian dimension on 29 April 2020 (Akeregba et al., 2020) and published its last report entitled "NGO petitions UK House of Lords, others over abuse of Africans in China" on 4 July 2020. The Nations last report was similar to those of The Guardian but published earlier on 29 June 2020 with the headline "NGO petitions UK House of Lords, others over abuse of Africans in China."

Two reasons can be adduced for the difference in the life cycles of reports on the Guangzhou episode in the Ghanaian and Nigerian newspapers. First, is the Nigerian dimension, as discussed above. It is worth noting that there is a significant population of Nigerians in Guangzhou; one estimate puts their figure at about 10,000 in 2014 as compared to 264 Ghanaians in 2013 (Premium Times, 2014; Sundiata, 2015; Obeng, 2018). The relatively high population compared to Ghanaians or migrants from many other African countries might have increased Nigerians' visibility in Guangzhou. Nigerians were more involved in the Guangzhou episode than Ghanaians because Nigerians tested negative to COVID-19 in China and there was the circulation of a video of a Nigerian diplomat in China seen criticizing the Chinese authorities for how they treated Nigerians. This visibility of Nigerians in the episode likely sustained the interests of Nigerian newspapers in covering the story. Second, the Ghanaian newspapers relied more on Western news sources for their reports. For instance, the first three stories in the Daily Guide quoted Western media. Ghanaian newspapers gave voice to government but hardly interviewed Ghanaian or African migrants in China, except when they quoted interviews conducted by Western media. When their Western sources shifted focus from the Guangzhou episode to other issues, they also appeared to have shifted interest.

CONCLUSION

Given its ability to paint an image of the experiences of African migrants in China, the media occupies an important position in Africa-China relations. In this paper, I analyzed how four African-based newspapers framed the treatment of African migrants during the Guangzhou episode. I discussed their framing under three subheadings: source question, victimhood, and the Nigerian dimension. The paper contends that while the newspapers relied on Western media coverage for some of their own reports, they nonetheless accommodated Chinese and African voices. Although the Guangzhou episode was generally framed in terms of the victimhood of migrants, the "African" identity was reduced to national, and more importantly, a Nigerian dimension in many instances. The focus on the Nigerian dimension, while introducing some nuance in the discourse in terms of Chinese justification, frames the Guangzhou episode as moral panic.

Beyond the aforementioned, however, accessibility of online reports - as the ones analyzed in this paper - offers more space for interrogating knotty issues like racism, that is both controversial and recurring in Africa-China migration discourse. It democratizes access to information about Africa-China migration exchanges, even in a difficult global moment. Unlike in the past, when tensions between African migrants and their Chinese host were covered on traditional media (like radio, television, or newspapers), the Guangzhou episode demonstrates that online African-based media can publish their independent reports as well as cull reports from other media sources around the world. By generating and sustaining a particular image of Africa-China relations, local media can therefore influence how stakeholders within Africa respond to Chinese migrants on the continent. This is because the main audience of the local newspapers is Africa. This could have implications for Chinese migrants in Africa in particular and Africa-China relations in general. Even if their reports cannot be accessed in China, it could have an impact on the perception of Chinese citizens in African countries, as was the case when some members of parliament in Nigeria following the spread of reports on the maltreatment of Africans in Guangzhou initiated moves to deport Chinese migrants (Core News, 2020). Nonetheless, this paper calls for further research into the role of the media in shaping Africa-China migration. Aside from the need to further interrogate the timing, focus, and sources of reports on African migrants in China (and vice versa) using interviews, it is not yet known whether the media coverage of the Guangzhou episode had any impact on African migrants in China. Investigating this impact could provide deeper insights into the role of the media on African migrants' experiences in China.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I thank the organizers and participants of the webinar on "Emerging dimensions of Sino-African migrations" hosted by the Canadian Excellence Research Chair (CERC) Ryerson University's Migration Working Group, on 30 November 2021 where the paper was first presented. I am particularly grateful to Anna Triandafyllidou and Oreva Olakpe for their useful comments on the original paper and for their patience. I am also grateful to the reviewers for their critical but useful comments on an earlier version of the paper.

REFERENCES

Adekanye, M. 2020. McDonald's apologises after China store bans Black people. The Guardian, 14 April. Available at: https://guardian.ng/life/mcdonalds-apologises-after-china-store-bans-black-people/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Adekoya, F. 2020. Issues with Nigeria's bilateral ties with China post-pandemic. The Guardian, 29 April. Available at: https://guardian.ng/business-services/issues-with-nigerias-bilateral-ties-with-china-post-pandemic/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Agence France-Presse (AFP). 2020a. China province launches anti-racism push after outrage. The Guardian, 4 May. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/world/china-province-launches-anti-racism-push-after-outrage/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Agence France-Presse (AFP). 2020b. Nigeria says treatment of nationals in China "unacceptable." The Guardian, 14 April. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/nigeria/nigeria-says-treatment-of-nationals-in-china-unacceptable/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Akeregha, I., Abuh, A. and Njoku, L. 2020. Reps deplore alleged maltreatment of Nigerians in China, urge evacuation. The Guardian, 29 April. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/reps-deplore-alleged-maltreatment-of-nigerians-in-china-urge-evacuation/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Akinyoade, A. 2015. Nigerians in transit: The trader and the religious in Jerusalem House, Ghana. In Akinyoade, A. and Gewald, J-B (eds.), African road to prosperity: People en route to socio-cultural and economic transformations. Leiden: Brill, pp. 211-231. [ Links ]

Amalu, G. 2020. China mocks Africa. The Nation, 21 April. Available at: https://thenationonlineng.net/china-mocks-africa/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Amoah, P.A, Hodzi, O. and Castillo, R. 2020. Africans in China and Chinese in Africa: Inequalities, social identities, and wellbeing. Asian Ethnicity, 21(4): 457-463. [ Links ]

Annang, P. 2020. COVID-19: Over 600 stranded Ghanaians due home this week. Graphic, 16 June. Available at: https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/250-ghanaians-expected-to-arrive-from-the-united-arab-emirates-today.html. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Aremu, J.O. 2013. Responses to the 1983 expulsion of aliens from Nigeria: A critique. African Research Review, 7(3): 340-352. [ Links ]

Arku, J. 2020. COVID-19: Ghanaians in China safe amid discrimination against Africans. Graphic, 17 April. Available at: https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/covid-19-ghanaians-in-china-safe-amid-discrimination-against-africans.html. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., KhosravNik, M., Krzyzanowski, M., McEnery, T., et al. 2008. A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse & Society, 19(3): 273-306. [ Links ]

Basikoro, E.E. 2020. COVID-19: An emerging source of stigma. The Nation, 19 April. Available at: https://thenationonlineng.net/covid-19-an-emerging-source-of-stigma/. Accessed on 20 September 2020.

Berry, M., Garcia-Blanco, I. and Moore, K. 2015. Press coverage of the refugee and migrant crisis in the EU: A content analysis of five European countries. Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies. UNHCR.

Bodomo, A. 2020. Historical and contemporary perspectives on inequalities and well-being of Africans in China, Asian Ethnicity, 21(4): 526-541. [ Links ]

Bräutigam, D. 2009. The dragon's gift: The real story of China in Africa. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2018. Lunar New Year: Chinese TV gala includes "racist blackface" sketch. BBC News, 16 February. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-43081218. Accessed on 23 November 2021.

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2020a. Africans "evicted from Chinese hotels over Covid-19 fears." Graphic, 8 April. Available at: https://www.graphic.com.gh/international/international-news/africans-evicted-from-chinese-hotels-over-covid-19-fears.html. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2020b. China to cancel interest-free loans to African nations. Graphic, 18 June. Available at: https://www.graphic.com.gh/international/international-news/china-to-cancel-interest-free-loans-to-african-nations.html. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). 2020c. Covid-19 stigma: Chinese hotels & apartments don pursue Africans comot from dia property for fear of coronavirus. BBC News Pidgin, 8 April. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/pidgin/tori-52211995. Accessed 16 August 2021.

Cable News Network (CNN). 2020. Virus fears spark xenophobia in China. Graphic, 11 April. Available at: https://www.graphic.com.gh/international/international-news/virus-fears-spark-xenophobia-in-china.html. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Chan, S. 2013. The morality of China in Africa: The middle kingdom and the dark continent. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Cheng, Y. 2011. From campus racism to cyber racism: Discourse of race and Chinese nationalism. The China Quarterly, 207(3): 561-579. [ Links ]

China Global Television Network (CGTN). 2020. China denies discrimination against Africans in Guangzhou. 14 April. Available at: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-04-13/China-denies-discrimination-against-Africans-in-Guangzhou-PEPqwgJ8qY/index.html. Accessed on 16 August 2020.

Churches' Commission for Migrants in Europe (CCME) and World Association for Christian Communication (WACC). 2017. Changing the narrative: Media representation of refugees and migrants in Europe. Christian Communication - Europe Region (CCER) and the Churches' Commission for Migrants in Europe (CCME).

Cissé, D. 2021. As migration and trade increase between China and Africa, traders at both ends often face precarity. 21 July. Migration Policy Institute. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/migration-trade-china-africa-traders-face-precarity. Accessed on 12 July 2023.

Core News. 2020. Lawmakers want illegal Chinese migrants deported. 29 April. Available at: https://corengr.com/lawmakers-set-to-deport-chinese-nationals-as-evacuation-begins-on-monday/. Accessed on 20 July 2023.

Dahir, A-L. 2018. Hacking Africa: China "gifted" the African Union a headquarters building and then allegedly bugged it for state secrets. Quartz Africa, January 30. Available at: https://qz.com/africa/1192493/china-spied-on-african-union-headquarters-for-five-years/. Accessed on 1 August 2020.

Daily Graphic. 1968. Arms deal with China. October 8. Accra, Ghana.

de Vreese, C. 2005. News framing: Theory and typology. Information Design Journal + Document Design, 13(1): 51-62. [ Links ]

Essa, A. 2018. China is buying African media's silence. Foreign Policy, 14 September. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/14/china-is-buying-african-medias-silence/. Accessed on 29 August 2020.

Ethical Journalism Network (EJN). 2017. How does the media on both sides of the Mediterranean report on migration? London: EJN. [ Links ]

Forges, A.D. 2007. Call to genocide: Radio in Rwanda, 1994. In A. Thompson (ed.), The media and the Rwanda genocide. London: Pluto Press, pp. 41-54. [ Links ]

Global Times. 2020a. Necessary for China to carry out quarantine, passport check: Nigerian FM. 15 April. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1185726.shtml. Accessed on 28 August 2020.

Global Times. 2020b. Who is behind the fake news of "discrimination" against Africans in China? 16 April. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1185845.shtml. Accessed on 30 August 2020.

Global Times. 2023. 4 first-tier cities in China record temporary population declines: Metropolitans retain gravity for talent, focus on quality development. 15 May. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202305/1290759.shtml. Accessed on 18 July 2023.

Guardian. 2020a. African community targeted in China virus crackdown. Editorial, 11 April. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/world/african-community-targeted-in-china-virus-crackdown/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Guardian. 2020b. Five Nigerians test positive for coronavirus in China. Editorial, 8 April. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/five-nigerians-test-positive-for-coronavirus-in-china/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Guardian. 2020c. Stop maltreating Africans in China! Editorial, 5 May. Available at: https://guardian.ng/opinion/stop-maltreating-africans-in-china/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Ho, E.L. 2018. African students in China: The intersection of educational and trading-led migration. Asia Dialogue. 2 April. Available at: https://theasiadialogue.com/2018/04/02/african-students-in-china-the-intersection-of-educational-and-trading-led-migration/. Accessed on 11 July 2023.

Ikuomola, V. 2020a. Onyeama debunks alleged maltreatment of Nigerians in China. The Nation, 15 April. Available at: https://thenationonlineng.net/onyeama-debunks-alleged-maltreatment-of-nigerians-in-china/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Ikuomola, V. 2020b. Why we enforce strict measures against Nigerians, others -China. The Nation, 14 April. Available at: https://thenationonlineng.net/why-we-enforce-strict-measures-against-nigerians-others-china/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Ikuomola, V., Akowe, T. and Oluwasegun, V. 2020. FG protests alleged maltreatment of stranded Nigerians in China. The Nation, 11 April. Available at: https://thenationonlineng.net/fg-protests-alleged-maltreatment-of-stranded-nigerians-in-china/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Jin, X., Spierings, B., Bolt, G. and Hooimeijer, P. 2023. Nigerian migrants, daily life domains and bordering processes in the city of Guangzhou. Urban Geography. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2023.2179839.

Kirton, D. 2020. In China's "Little Africa," a struggle to get back to business after lockdown. Reuters, 26 June, Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-china-africans-idUSKBN23X0HO. Accessed on 18 July 2023.

Li, A. 2018. African students in China: Research, reality and reflection. African Studies Quarterly, 17(4): 5-44. [ Links ]

Li, S. 2017. Mediatized China-Africa relations: How media discourses negotiate the shifting of global order. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Makundi, H. 2020. I asked Tanzanians about studying in China: Here's what they said. The Conversation, January 23.

Marsh, J. 2016. The African migrants giving up on the Chinese dream. CNN, 26 September. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2016/06/26/asia/africans-leaving-guangzhou-china/index.html. Accessed on 18 July 2023.

McDonald, J. 2021. Chinese TV features blackface performers in New Year's gala. AP, 12 February. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/china-tv-blackface-performers-new-years-7da7eb251c3e2e26f67f673769266823. Accessed on 23 November 2021.

McQuail, D. 2003. McQuails mass communication theory. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mudasiru, S. and Oshodi, A.T. 2020. Reporting the dragon: A thematic study of antiChinese sentiments in "China in Africa" news coverage. In Abidde, S.O. and Ayoola, T.A. (eds.), China in Africa: Imperialist or partnership in humanitarian development. Maryland: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

News Agency of Nigeria (NAN). 2020a. African diplomats upbraid China on COVID-19 excesses. The Nation, 18 April. Available at: https://thenationonlineng.net/african-diplomats-upbraid-china-on-covid-19-excesses/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

News Agency of Nigeria (NAN). 2020b. South Africa coronavirus cases rise to 2,415, China donates equipment. The Nation, 14 April. Available at: https://thenationonlineng.net/south-africa-coronavirus-cases-rise-to-2415-china-donates-equipment/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Obasanjo, O. 2015. My command: An account of the Nigerian civil war, 1967-1970. Lagos: Prestige. [ Links ]

Obeng, M. 2018. Journey to the East: A study of Ghanaian migrants in Guangzhou, China. Canadian Journal of African Affairs, 53(1): 67-87. [ Links ]

Oluwasegun, V. and Akowe, T. 2020. Maltreatment against Nigerians: Repatriate illegal Chinese immigrants, Reps urge FG. The Nation, 28 April. Available at: https://thenationonlineng.net/maltreatment-against-nigerians-repatriate-illegal-chinese-immigrants-reps-urge-fg/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Onochie, B. 2020. Onyeama, Chinese envoy blame victimisation of Nigerians on poor communication. The Guardian, 15 April. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/onyeama-chinese-envoy-blame-victimisation-of-nigerians-on-poor-communication/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Oshodi, A.T. 2015. Between the dragon's gift and its claws: China in Africa and the (un)civil fostering of ILO's Decent Work Agenda. In Marx, A., Wouters, J., Rayp, G. and Beke, L. (eds.), Global governance of labor rights. Massachusetts: Edward Elgar, pp. 190-208. [ Links ]

Oshodi, A.T. 2020. Why maltreatment of Nigerians in China may not end soon. The Conversation, 28 May. Available at: https://theconversation.com/why-maltreatment-of-nigerians-in-china-may-not-end-soon-137828. Accessed on 20 July 2023.

Oshodi, A.T. 2021. China's relations with the African continent: Three elephants in the room. OpenDemocracy, 23 March. Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/pandemic-border/chinas-relations-with-the-african-continent-three-elephants-in-the-room/. Accessed on 20 August 2021.

Paluck, E.L. 2007. Reducing intergroup prejudice and conflict with the media: A field experiment in Rwanda. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Harvard University. [ Links ]

Peil, M. 1974. Ghana's aliens. International Migration Review, 8(3): 367-381. [ Links ]

Pingjian, Z. 2020. Pandemic: Solidarity and cooperation most potent weapon. The Guardian, 11 May. Available at: https://guardian.ng/opinion/pandemic-solidarity-and-cooperation-most-potent-weapon/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Premium Times. 2014. Nigeria "will fight Boko Haram with every resource at our disposal," - Mark. 12 May. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/160584-nigeria-will-fight-boko-haram-every-resource-disposal-mark.html?tztc=1. Accessed on 19 July 2023.

Reuters. 2020. China denies city discriminating against "African brothers." 13 April. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-china-africa/china-denies-city-discriminating-against-african-brothers-idUSKCN21V0HV?il=0. Accessed on 28 August 2020.

Sautman, B. 1994. Anti-black racism in post-Mao China. China Quarterly, 138: 413437. [ Links ]

Scheufele, D.A. 1999. Framing as a theory of media effects. Journal of Communication, 49(1): 103-122. [ Links ]

Serwornoo, M.Y. 2019. Postcolonial trajectories of foreign news selection in the Ghanaian press. Journalism Studies, 20(9): 1357-1375. [ Links ]

Strange, A., Park, B., Tierney, M., Fuchs, A., Dreher, A., et al. 2013. China's development finance to Africa: A media-based approach to data collection. Working Paper No. 323, Center for Global Development.

Sullivan, M. 1994. The 1988-89 Nanjing anti-African protests: Racial nationalism or national racism? The China Quarterly, 138: 438-457. [ Links ]

Sundiata Post. 2015. Nigerians constitute biggest African population in China, says Ambassador. 11 August. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20180201075320/https://sundiatapost.com/2015/08/11/nigerians-constitute-biggest-african-population-in-china-says-ambassador/. Accessed on 19 July 2023.

Tarlue, M. 2020a. Ambassadors protest China's racist Covid-19 testing of Africans. Daily Guide, 12 April. Available at: https://dailyguidenetwork.com/ambassadors-protest-chinas-racist-covid-19-testing-of-africans/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Tarlue, M. 2020b. Ghana condemns China over racist attacks. Daily Guide, 11 April. Available at: https://dailyguidenetwork.com/ghana-condemns-china-over-racist-attacks/. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Umejei, E. 2017. Newspaper coverage of China's engagement with Nigeria: Partner or predator? In Batchelor, K. and Zhang, X. (eds.), China-Africa relations: Building images through cultural cooperation, media representation and communication. London: Routledge, pp. 167-183. [ Links ]

van Staden, C. and Wu, Y. 2018. Media as a site of contestation in China-Africa relations. In Alden, C. and Large, D. (eds.), New directions in Africa-China studies. London: Routledge, pp. 88-103. [ Links ]

Wekesa, B. 2017a. Chinese media and diplomacy in Africa: Theoretical pathways. In Batchelor, K and Zhang, X. (eds.), China-Africa relations: Building images through cultural cooperation, media representation and communication. London: Routledge, pp. 149-166. [ Links ]

Wekesa, B. 2017b. New directions in the study of Africa-China media and communications engagements. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 29(1): 1124. [ Links ]

Yan, H. 2020. The truth about Chinese migrants in Africa and their self-segregation. Quartz Africa, 5 June. Available at: https://qz.com/africa/1865111/chinese-migrant-workers-in-africa-and-myths-of-self-segregation/. Accessed on 21 August 2022.

Yan, H. and Sautman, B. 2012. Chasing ghosts: Rumours and representations of the export of Chinese convict labour to developing countries. China Quarterly, 210: 398-418. [ Links ]

Yeboah, I. 2020. Nigeria, Kenya protest maltreatment of nationals in China. Graphic, 11 April. Available at: https://www.graphic.com.gh/international/international-news/nigeria-kenya-protest-maltreatment-of-nationals-in-china.html. Accessed on 20 August 2020.

Received 13 December 2022

Accepted 25 July 2023

Published 18 August 2023