Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Human Mobility Review

On-line version ISSN 2410-7972

Print version ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.9 n.2 Cape Town May./Aug. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.14426/ahmr.v9i2.1333

ARTICLES

Higher Education as "Strategic Power"? An Assessment of China-Africa Higher Education Partnerships and Collaborations

Obert HodziI; Padmore AmoahII

IUniversity of Liverpool, United Kingdom. Corresponding author.o.hodzi@liverpool.ac.uk

IILignan University, Hong Kong

ABSTRACT

China is internationalizing its higher education sector - setting up several bilateral and multilateral partnerships between public and private institutions across the globe. However, as the "West" is disentangling itself from partnerships with Chinese institutions of higher education and the Confucius Institutes (CIs), African countries seem to be turning to Beijing. As a result, China overtook France to become the most preferred destination for African students. But, is higher education Beijing's new strategy to enhance its global status? What is the effect of the shift toward Chinese higher education on Africa's migration trends, and what is the agency of actors in Africa? Focusing on these questions, and premised on the concepts of student mobility, South-South Cooperation (SSC), and people-to-people exchange to explain the novelty and exceptionality of the partnerships, this paper explores the typology, nature, and processes involved in these partnerships and collaborations.

Keywords: education, internationalization, mobility, students, cooperation

INTRODUCTION

This paper elucidates the evolution and characteristics of the China-Africa educational partnership at macro-level. It sets out proposals for advancing debates to the micro-levels within the broader discourse on higher education internationalization in the context of South-South Cooperation (SSC). Kevin Gray and Barry Gills (2016: 557) describe SSC as,

... a key organizing concept and a set of practices in pursuit of historical changes through a vision of mutual benefit and solidarity among the disadvantaged of the world system ... conveying the hope that development may be achieved by the poor themselves through their mutual assistance to one another, and the whole world order transformed to reflect their mutual interests vis-ä-vis the dominant global north.

With knowledge production being at the core of North-South inequalities, China-Africa cooperation in education, seemingly, seeks to challenge the asymmetries in global education production and consumption.

This paper examines the nature and processes of the making of the China-Africa partnerships and collaborations. It also addresses critical questions such as: Who initiates the collaborations? Who pays for them? Who benefits? What objectives are they meant to achieve? The discussion then extends current debates from the macro- to the micro-level by examining the career and social mobility of the students involved in the China-Africa educational partnerships at the backdrop of the rising student numbers and academic collaborations. By exploring these key issues, the paper sheds light on how countries that were traditionally seen as sources of international students are strategically positioning themselves as destination countries in the global higher education landscape and the impact of these efforts on the career prospects and quality of life of the students. This is a significant departure from existing studies that have predominantly focused on the discourse at the macro-level. The paper therefore makes four critical contributions to the discourse on higher education internationalization - the contributions center on the South-South dynamic between China and Africa; the type of both equal and unequal relationships between China and specific African countries; the primacy of the state instead of the universities in this exchange; and how this influences future global leadership in higher education.

SITUATING CHINA-AFRICA HIGHER EDUCATION IN GLOBAL EDUCATION MOBILITY TRENDS

In response to current global transitions in higher education, governments, state, and non-state institutions are intensifying higher education internationalization efforts (Altbach and Knight, 2007; Mihut et al., 2017). This is because the number of international students has increased exponentially. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2020), the number of international students grew from a mere 2 million in 2000 to about 5.3 million students in 2017. The majority of these international students are from China, India, France, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and South Korea. Beyond this international mobility of students, other main characteristics of the global transitions in higher education internationalization include: rising flows and exchanges of scholars (for research, teaching, seminars, and conferences), academic materials and resources, joint programs, creation of diverse funding schemes, international campus branches, an intensified collaboration between governments, universities and markets to drive change (Altbach and Knight, 2007; Altbach et al., 2009; Chen, 2016; Knight and de Wit, 2018).

Several factors have contributed to this growing global interest in internationalization of higher education. First, the cutting of government funding for higher education compelled institutions in Western Europe, the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, the United States (US), and Nordic countries such as Finland to look for alternative sources of financing. International students, mostly from emerging economies such as China and India became sources of income for most Western universities. To remain competitive in the global race for external students, internationalization became a marketization strategy that underpins the now entrenched neo-liberal governance approaches at higher education institutions (HEIs) (Mok, 2000; Lynch, 2006; Knight and de Wit, 2018; McCaig et al., 2018; Nixon et al., 2018). Internationalization is therefore a means for universities to attract international students - thus maximizing their income potentials.

Second, the growth in Information and Communications Technology (ICT) underlies higher education internationalization. Using ICT, remote teaching and learning enable universities to reach international students without incurring expenses that accompany a physical campus. For students needing to attain a higher education without physically relocating, distance learning has become an alternative. In addition, it has enabled students to circumvent the often-stringent visa requirements in the UK, the US, and other European countries. This has revolutionized how knowledge is produced and communicated globally (Altbach et al., 2009; Knight and de Wit, 2018), and enabled universities to increase their student numbers and revenue beyond what they could have with only physical learning. With the COVID-19 pandemic restricting student movement, universities that provided distance learning gained popularity, forcing traditional universities to consider hybrid learning to tap into the distance-learning market.

Third, states are regarding higher education as a source of "soft power." Joseph Nye (1990) defines soft power as the ability of a country to shape preferences of other countries, through the attractiveness of its culture, values, political, social, and economic advancement, so that they desire the outcomes it wants. Due to their cosmopolitan nature, universities are a bastion of multiculturalism and a tool for dispensing a country's culture, values, and norms beyond its citizens. Previously, this was limited to the developed West but now, even emerging powers in the Global South, including China, consider internationalization of higher education as a diplomacy strategy (Yang, 2010; Fijalkowski, 2011; Bodomo, 2015; Knight and de Wit, 2018). Even for Africa, the exploits of African economic and educational migrants have been described as a form of soft power, even though African universities are still finding their footing in the global higher education space (Altbach et al., 2009).

Based on international student mobility, China and Chinese universities are becoming key players in the global higher education industry. For the Chinese government, the ultimate goal is making the country highly competitive as a destination for international students (Mok and Chan, 2008). Therefore, the country, through its decentralized arms has initiated numerous policies and strategies to restructure the education and governance systems to meet internal needs and be globally competitive (Mok and Chan, 2008; Zha, 2012; Chen, 2016). Popular among such policies are those relating to quality assurance of academic practices, international benchmarking teaching and research, the transformation of selected universities into world-class institutions, diversifying funding sources, promoting international partnerships, creating opportunities for international branch campuses in China, and aggressively developing English-language programs (Mok and Lo, 2007; Mok and Chan, 2008; Zha, 2012; Chen, 2016).

Operationalization of these policies has attracted African students to further their education in China. Similarly, African institutions, in need of infrastructural development and education development assistance, also are intensifying efforts to build partnerships with their Chinese counterparts (King, 2014; Li, 2018). As noted by several authors (Bodomo, 2011; Niu, 2013; King, 2014), China's educational internationalization has, since the turn of the century, been particularly notable in its partnership with African nations. Indeed, "the Chinese government attaches high symbolic value to the scholarships offered to Africa and it has a long history of using educational aid as a means to reinforce ties with African countries" (Haugen, 2013: 315). The result, as noted by Li Anshan (2018), is that the growth rate of African students in the past decade is highest among all international student arrivals in China.

China-Africa education partnership: Nature and typologies

Afro-Sino relations have a long history dating back to the 1950s when the primary focus was on the anti-colonial and ideological struggles in Africa (Besada and O'Bright, 2017). Over the past two decades, relations have significantly expanded to include trade, education, and training. Despite educational exchanges being put on hold in 1966 due to the Cultural Revolution in China, the education sector is now considered a key area of collaboration (Niu, 2013; King, 2014; Li, 2018). While the policy for educational support and cooperation between China and Africa has been generally fragmented, spanning from technical cooperation, education and training, and human resource development cooperation (King, 2014), the 2018 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) action plan offered a more specific theme, education, and human resources (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). The Government of China initiated FOCAC in 2000 as a multi-purpose vehicle for engaging with Africa on all development fronts, including [higher] education (Niu, 2013; King, 2014; FOCAC, 2020). Among others, the areas of higher education cooperation between China and Africa includes staff exchange; promoting exchanges and cooperation in culture, art, and media; infrastructure development; support for human and institutional capacity building; supply of academic materials; joint research; recruitment of African students; and other collaborative programs (Niu, 2013; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). A typical example of exchange partnerships is embodied in the renowned 20+20 Cooperation Plan that was launched in 2009 (King, 2014; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). The plan encourages intensive one-to-one cooperation between 20 Chinese universities and colleges and 20 African institutions at the same level.

These policies and the respective programs emerging from them are facilitated through various public and private funding sources, mainly initiated and originating from China. The funding mix comprises provincial scholarships, special scholarships by private corporations (e.g., China National Petroleum Corporation), Chinese central and local government scholarships, as well as opportunities for self-funded studies (He, 2010; Haugen, 2013; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). The Chinese government, as announced at the 2018 FOCAC summit in Beijing, plans to continue on this path by providing Africa with 50,000 government scholarships and 50,000 places for seminars and workshops for professionals of different disciplines (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). Thus, in the spirit of cooperation and mutual development, China's approach to higher education has become more targeted. For instance, the FOCAC 2019-2021 action plan sought to offer tailor-made training for high-caliber Africans (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). In recent years, programs such as Master's in Public Administration have been specifically designed and delivered to numerous government officials of African nations (King, 2014). These policies and others alike have since 2000 been operated under the aegis of the FOCAC framework and these are partly why China's education cooperation has been described as Africa-based (Niu, 2013; FOCAC, 2020).

The relationship between China and Africa as regards higher education is, therefore, somewhat unique relative to those of Africa's arrangements with other established and emerging powers. China presents itself more as a development partner to African nations and institutions instead of the traditional development aid approach and mechanisms adopted by the UK (DFID), USA (USAID), and South Korea (KOICA) (King, 2014). Educational cooperation is, therefore, considered part of China's broader development assistance to Africa. For instance, in Nigeria, due to the lack of qualified Nigerian railway engineers, as part of its corporate social responsibility, the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation is constructing a University of Transportation in Nigeria. Nigeria's president, Muhammadu Buhari described the project as paving the "way for the domestication of railway engineering and general transportation sciences in Nigeria, thereby bridging the technology and skill gap in the railway and ultimately transportation sector" (Xinhua, 2019). This approach, according to China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs is inspired by China's fundamental principles of equality, mutual benefit, win-win economic development, solidarity, mutual trust, mutual support, and support for its partner nations to explore their preferred development paths (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). This is what has been termed as "overseas aid with its own [Chinese] characteristics" (King, 2014: 3). The linking of education cooperation with broader development cooperation means that China-Africa educational cooperation centers the state. Accordingly, China's [higher] education engagement with African institutions and nations has taken the form of support for various countries to pursue their priority education programs and projects, as has been witnessed in the construction of Science University in Malawi, and the building and equipping of the Polytechnic College in Ethiopia (King, 2014).

The implication is that China's internationalization agenda in the context of its relations with Africa departs from the purely market-driven approach adopted by many Western nations (Lynch, 2006; Altbach and Knight, 2007; King, 2014). Although the Ministry of Education of China established the China Scholarship Council as the primary vehicle through which the Chinese government awards scholarships, heads of state, through bilateral and multilateral agreements and forums such as FOCAC, still play a role in determining the nature of education and human resource exchange and training, which form part of China's internationalization process. It appears that the Chinese universities follow what the Chinese central government decides at the state level - giving an impression of a state-led higher education internationalization process. The result is that the state-driven process is geared toward achieving political and diplomatic objectives as opposed to an economic-led strategy. Moreover, China's involvement is gradually positioning African educational systems as internationalized, contrary to the situation a decade ago (Altbach and Knight, 2007; Haugen, 2013). However, the use of education as a soft power instrument to enhance a country's external image is not unique to China. The soft power dimensions of China's educational engagement, such as the language and cultural services offered by its Confucius Institutes (CIs) through various institutional partnerships do not, in theory, differ from those of other high-income nations and emerging powers. For instance, Germany and France use the Goethe Institute and the Alliance Fran^aise respectively, to promote their national languages and cultures. In Germany, scholarships awarded to international recipients by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) often require recipients to undertake mandatory German language courses. Arguably, China's CIs are imitating these strategies, in their quest to promote the Chinese language and culture. The difference, however, is that in practice, in the case of the CIs, unlike the Goethe Institute and the Alliance Française, the visibility of the Communist Party of China (CPC) is obvious. In addition, CIs are normally established at foreign universities as joint ventures between the host university or school, a university in China, and the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF), which is supposedly a nongovernmental and nonprofit organization, although it "is under the supervision of the Chinese Ministry of Education and is funded by the Chinese government" (Peterson et al., 2022: 27) - so the Chinese government remains with indirect influence over the CIs. Each CI abroad has two directors - one from the local university or school and another from the Chinese partner university. Over the past five years, CIs in the US and Europe have come under criticism due to allegations that they restrict academic freedom by prohibiting topics that are sensitive to the Chinese government. Resultantly, there are growing perceptions that the CIs advance the interests of the CPC more than the Chinese language and culture. This perception is, however, not shared by African universities that have CIs - none of the African universities have raised complaints about the CIs restricting academic freedom or advancing the interests of the CPC on their campuses.

African students in China: Trends

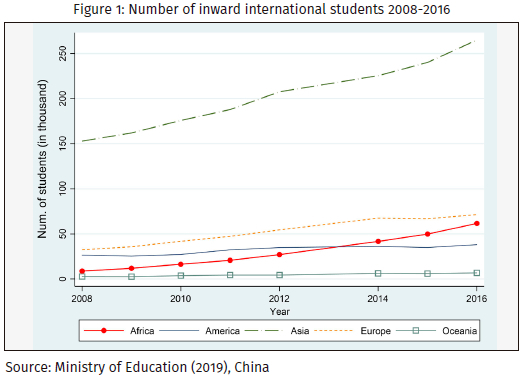

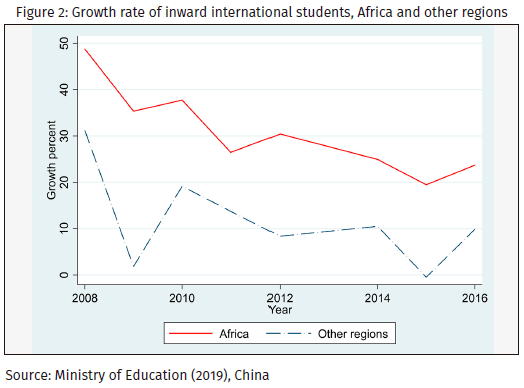

Following the background to the China-Africa educational partnership above, we now examine the status and trends of African students' engagement with China's higher education system. This, as argued by Robin Helms and Laura Rumbley (2017), is critical to an inquiry on whether higher education internationalization policies are essential to attaining academic, political, social, and cultural goals. On the surface, based on the increase of students from African countries studying at universities in China, China's internationalization process seems to be successful (Li, 2018). Pronouncements made at the 2018 FOCAC summit on increased scholarships, tailored study programs, and human resource capacity building initiatives announced by China indicate that the trend is likely to continue (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2018). The total number of students from Africa in China is third in relation to those from Asia and Europe, having surpassed the Americas since 2013 (see Figure 1) (Ministry of Education, 2019). As of 2018, 81,562 Africans were studying in China, a more than 40-fold increase in 15 years, from just 1,793 in 2003 (Li, 2018; Lau, 2020). Given that the growth rate of African students in China has remained the highest among all other international students since 2008 (see Figure 2) (Ministry of Education, 2019), it is expected that African students will remain the second most populous group of international students in China, second only to students from the Asian region.

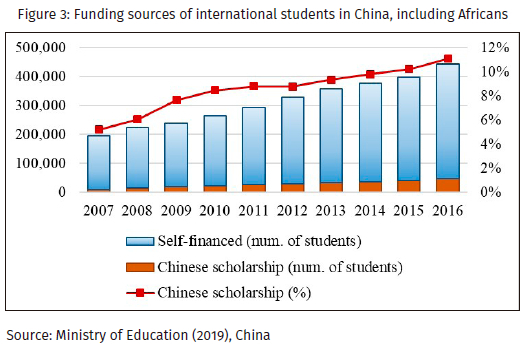

Moreover, while there is a notion that African students in China are motivated by financial incentives (scholarship incentives mainly) (Haugen, 2013), current trends depict a different situation (Li, 2018). From 1976 to 1988, all African students in China were on scholarships. This trend changed from 1989 with two students studying in China on a self-financed basis and the number of those without scholarship exceeding scholarship holders for the first time in 1994 (Li, 2018). Since 2006, the number of self-financed African students in China has always exceeded their counterparts on financial aid, and this was as a result of the 2006 FOCAC summit when new forms of educational exchanges and partnerships, as well as more flexible visa application processes, were introduced (King, 2014; Li, 2018). In addition, the demand for alternatives to the expensive Western education, coupled with increased awareness of China as a destination for education among Africans of middle- and upper-middle-class status, and Africans doing business in China who are able to fund their education also contributed to this increase in self-financing African students in China. Consequently, there were as many as 41,322 self-financed students compared to 8,470 students on scholarships as at 2015 (Li, 2018). In fact, the proportion of overall international students on scholarships in China as at 2016 was approximately 11%, rising from about 5% in 2007, as shown in Figure 3 (Ministry of Education, 2019). Therefore, one could argue that China has been able to ground its higher education internationalization agenda in Africa in the institutional realities of the most crucial partners, universities, and colleges (Helms and Rumbley, 2017). This reality notwithstanding, it must be emphasized that the success in drawing educational institutions in the China-Africa educational partnership is attributable to the prevailing political and governance structure of China, which has strategically used the HEIs as instruments to achieve the desired soft power and internationalization outcomes (Mok, 2000, 2014; Mok and Chan, 2008; Mok and Ong, 2014).

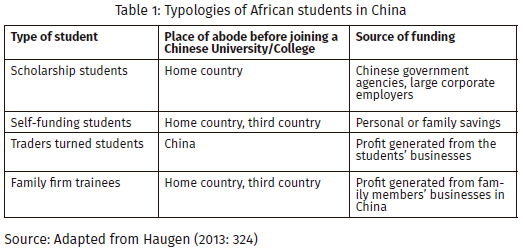

While the policy aspect of the engagement is intriguing, the nature, conditions, and prospects of the students involved in the multi-faceted arrangements between China and the African nations require further inquiry. African students in China are far from homogenous, at least from a financial point of view as well as their pre-schooling situation. A previous study by Heidi Haugen (2013) provided a typology of African students in China, which serves as a significant starting point to understanding the nature of the people involved in the educational engagement and their aspirations. In that study, various kinds of students were identified in terms of: funding arrangements (four kinds), their schooling journey (four kinds), and the places of origin before commencing their studies, as shown in Table 1. Thus, while various policies are encouraging several Africans to seek higher education in China, attention must be given to the varying current and prospective integration and development of the students involved, given their heterogeneity. More importantly, this call is essential to the sustainability of the China-Africa education collaboration, as the experiences of the students during and after their studies are critical to others planning on embarking on similar journeys. As Haugen (2013) demonstrates, the negative experiences of African students can create a serious dent on the ambition of China to increase its soft power in Africa through educational engagements.

MAKING SENSE OF CHINA-AFRICA EDUCATIONAL PARTNERSHIPS

China-Africa educational cooperation is framed by the Chinese government as part of South-South Cooperation (SSC). Broadly defined, according to Meibo Huang (2019: 1) SSC is "cooperation at bilateral, regional, or interregional levels that is initiated, organized, and managed by developing countries themselves, in order to promote political, economic, social, cultural, and scientific development." In 2015, Beijing launched the South-South Cooperation Fund to support developing countries to implement and achieve their development objectives. At the end of 2017, China had supported more than 200 development cooperation projects, including projects on education and training, in more than 27 countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Earlier on, in 2015, President Xi had announced the establishment of the Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development (ISSCAD) - a flagship institute that subsequently launched at Peking University. According to the Institute's website, it "provides both degree education and non-degree executive training programs for mid-level to senior officials, as well as managers, researchers from government, academia, the media, NGOs and other organizations in developing countries." Several government officials from African countries, have been trained at ISSCAD - graduating with degrees up to PhD level. For China, funds and institutions like these provide ample evidence of its commitment to knowledge sharing, technical skills transfer and transformative learning in its relations with countries in the Global South. Importantly, it provides China an opportunity to train middle- to senior-level officials from Africa on development and governance - thus promoting its development and governance model. Therefore, internationalization of higher education is linked to China's foreign policy objectives while addressing educational and skills gaps in Africa.

The centrality of the state in China's internationalization of higher education and educational cooperation with African countries gives credence to Jurgen Enders's (2004: 367) definition of internationalization, as referring "mainly to processes of greater cooperation between states, and consequently to activities which take place across state borders. Located within the SSC framework, internationalization and educational cooperation builds strategic relationships, based on mutual cooperation and mutual observation." The implication, in the case of China-Africa educational cooperation is the absence of the market in China's higher education internationalization because, for instance, the Chinese government announces, after consultation with African governments, training and education scholarships at FOCAC summits, then requests universities to accommodate the students selected by governments in Africa to study at Chinese universities.

Between China and Africa, internationalization is mostly a government rather than an institutional initiative aimed at the "generation and transmission of ideology, the selection and formation of elites, the social development and educational upgrading of societies, the production and application of knowledge and the training of highly skilled labour force" (Enders, 2004: 362). For instance, with regard to most of the scholarships, African governments link areas of study with their national priorities, thus reducing Chinese universities to implementers of bilateral agreements between China and African governments. The implication is that internationalization of higher education in China in the context of China-Africa educational cooperation is limited to student mobility and human resource training of Africans. Africans are receivers of training and education from Chinese universities and experts. This dynamic mimics the North-South dynamic in which the Global North is the producer of knowledge consumed by the Global South. In place of the Global North, by establishing educational centers such as ISSCAD, providing scholarships and tailor-making professional and technical training to suit the needs of African states, China is establishing itself as a producer of knowledge and expertise relevant to the African continent. While in the past, China was hesitant, increasingly it is asserting itself as a major developing country with development and poverty-reduction experience that other countries in the Global South can learn from. Therefore, instead of China-Africa higher education cooperation challenging the Western- and Euro-centric perspectives, it exposes the asymmetrical power dynamics between "South-South" countries like China and different African countries - where China is the producer of knowledge and expertise consumed by African countries.

To the contrary, internationalization of higher education should go beyond international student mobility. Instead, as argued by Foskett (2010: 37):

Internationalization reaches to the heart of the very meaning of "university" and into every facet of its operation, from teaching and education to research and scholarship, to enterprise and innovation and to the culture and ethos of the institution.

That means internationalization involves transformative changes in what is taught, how it is taught, why it is taught, where and who teaches it. From that perspective, internationalization in China's higher education in the context of China-Africa educational cooperation is still conceptualized as an outcome rather than a process -the outcomes focused on being student mobility, training programs, and educational development assistance. There is, therefore, no meaningful integration of African and Chinese institutions, let alone the integration of African students in Chinese society and educational system. Accordingly, there is a need for China and African countries to regard internationalization as,

... the intentional process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions and delivery of post-secondary education, in order to enhance the quality of education and research for all students and staff, and to make a meaningful contribution to society (de Wit et al., 2015: 283, italics in original).

Without integration, China-Africa educational cooperation and internationalization of higher education between the two replicates the North-South asymmetries of power in knowledge production and consumption. For instance, as at 2018, there were 81,562 Africans studying in China compared to an estimated total of no more than 800 Chinese students in Africa, according to UNESCO (2020) statistics. A majority of Chinese students study in the US, UK, and Australia - together, the three countries make up almost 60 percent of Chinese international students. "These uneven flows of students and capital are an indication of the markedly different ways that the global political economy affects HEIs around the world" (Vavrus and Pekol, 2015: 6). Faculty exchanges in China-Africa education cooperation also reflect similar evidence of asymmetry - they challenge China's notion of people-to-people exchange, upon which its cooperation with Africa hinges. The impression is that Africans are consumers of China's knowledge and expertise. Kenneth King (2019: 337) argues that such evident asymmetry does not preclude the mutual equality in China-Africa relations because the principles of people-to-people exchange and "win-win economic, cultural or educational cooperation do not depend on precisely equal activities within the education sector but rather on a shared appreciation that the other party is equal." Nonetheless, the fact that fewer than 800 out of an estimated 600,000 Chinese students studying abroad consider Africa a destination for their higher education means that global inequalities in the knowledge production are taking root. With only about 800 Chinese students across Africa, institutions of higher education on the continent miss the revenue that Chinese students bring to universities in the West - thus they remain under-resourced and unable to benefit from the global internationalization drive.

Internationalization of higher education has in the past decade become a symbol of hierarchies of knowledge, influenced by "asymmetries of power and expertise" (Larsen, 2016: 6). The effect is that Africa is peripheralized in the global knowledge production hierarchies, leaving its internationalization process in the hands of foreign donors, China included. The reliance on development assistance for development of higher education in Africa means that African institutions of higher education are the last resort for universities in China seeking cooperation partners because they lack in global reputation and "struggle to carry out the most basic teaching and research functions" (Vavrus and Pekol, 2015: 6). Consequently, regardless of the South-South cooperation and people-to-people exchanges rhetoric, China-Africa educational cooperation replicates the North-South cooperation inequalities that it seeks to redress. As argued by Marianne Larsen (2016: 6), as redress to the global imbalances in higher education cooperation, internationalization should "reflect an understanding of the globalized world characterized by flows of people, ideas, objects, and capital, that is, the movement of higher education students, academics, programs, and providers." In other words, internationalization ought to be transformative, seeking to understand and respond to the complexities of knowledge production and higher education cooperation between the "developed" Global South and the "developing" Global South.

CONCLUSIONS AND WAY FORWARD

Notwithstanding the asymmetries in China-Africa educational cooperation, principles of South-South cooperation and people-to-people exchange provide a framework to reframe internationalization of higher education and mobility in relational terms. As put by Larsen (2016: 10), "Thinking relationally allows us to see how mobile students, academics, knowledge, programs and providers are enmeshed in networks that both enable and constrain possible individual and institutional actions." Making an argument for mobilities theories, Larsen (2016: 2) argues that,

[A] theoretical framework based on spatial network, and mobilities theories can provoke us to shift our attention from linear, binary, deterministic, Western-centric accounts of internationalization to understand the complex, multi-centered ways in which internationalization processes have played out across higher education landscapes worldwide.

Thus, enabling us to deconstruct why higher education internationalization perpetuate inequalities and asymmetrical hierarchies in higher education, which relegate Africa to consumption of knowledge produced in the West and China. As discussed in this paper, even though internationalization of higher education in China and the West is driven by different objectives - revenue in the West and soft power in China - the effect on the role and position of Africa in the global distribution of power is the same. Africa is still regarded by both China and the West as a consumer of their knowledge. The effect is that even though China-Africa educational cooperation is described by both parties as a form of South-South cooperation, symbolizing mutual benefit and equality, the power asymmetries between China and Africa are similar to those that existed in Africa's relations with the Global North.

In essence, China-Africa educational cooperation has accelerated internationalization of higher education in China, with a focus on outcomes rather than processes. As discussed above, this is because there has been little integration of institutions of higher education, poor funding of HEIs in Africa, and state-driven higher education cooperation and student mobility that is not based on HEIs' needs. With institutions of higher education reduced to implementers of government policy, African students in China are often confronted by university non-responsiveness to their needs, particularly if they are self-financing. It is therefore imperative that institutions of higher learning in China be part of the bilateral China-Africa educational cooperation arrangements. Such participation will help them understand the purpose and intentions underlying China-Africa education cooperation and focus on internationalization as a process of integration rather than an outcome measured by how many African students graduate from their universities.

Internationalization in China-Africa relations is aimed at achieving political and diplomatic goals - the balancing of political objectives with educational objectives, not just of the states but of African students is imperative. This means that instead of internationalization being imposed on least-prepared universities and higher education teachers, universities of higher learning in China will see that African students are equally important. Similarly, it will enable more capacity development for African universities to be able competitors in the internationalization competition and provide meaningful partnership to their Chinese counterparts. As it stands, there is insignificant consideration for "the active involvement of academics in internationalization, their perceptions of other cultures and people, the value they place on internationalization and their competence in speaking and reading other languages" (Harman, 2005: 131). The effect is that the internationalization of Chinese universities is to a greater extent linear, binary, and deterministic - focused on channeling out African graduates to meet the demand from Africa and advance Beijing's foreign policy objectives. The effect is that the boundaries between the state, universities, and the market are blurred, leading to non-transformative cooperation.

Overall, a relational approach to internationalization will enable internationalization programs and providers to confront the representations that disadvantage African institutions. Broadly, leading universities in China and across the globe only collaborate with equally prestigious universities, unless their intention is to capacitate African universities. Most of the existing capacity-building programs reinforce representations of African universities as inferior and not worthy of student and faculty exchanges. Accordingly, China-Africa educational cooperation and internationalization of higher education in both China and Africa should be transformational and to a greater extent revolutionary, if principles of people-to-people exchange and South-South cooperation are to be meaningful and usher Africa into the ongoing internationalization and global education competition. Yet, as discussed in this paper, China-Africa educational engagements challenge the dominant notions of South-South cooperation as an alternative to North-South cooperation. Instead, it shows that as China becomes more assertive and confident of exporting its development and governance model through institutions such as ISSCAD, the South-South dynamic is largely a replacement of the Global North with China; hence, a new "center" and an old periphery. China-Africa educational cooperation is therefore a betrayal of the South-South cooperation hope that Gray and Gills (2016) argued would transform the world order that favored the Global North because China is taking the place of the Global North in its relations with Africa.

REFERENCES

Altbach, P.G., and Knight, J. 2007. The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3-4), 290-305. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307303542 [ Links ]

Altbach, P.G., Reisberg, L., and Rumbley, L.E. 2009. Trends in global higher education: Tracking an academic revolution. Paper presented at the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education, Paris.

Besada, H., and O'Bright, B. 2017. Maturing Sino-Africa relations. Third World Quarterly, 38(3): 655-677. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1191343 [ Links ]

Bodomo, A. 2011. African students in China. A case study of newly arrived students on FOCAC funds at Chongqing University. Paper presented at the Comparative Education Research Centre (CERC) Seminar, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Bodomo, A. 2015. African soft power in China. African East-Asian Affairs: The China Monitor (1-2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.7552/0-1-2-160 [ Links ]

Chen, Q. 2016. Globalization and transnational academic mobility: The experiences of Chinese academic returnees. Singapore: Springer, Higher Education Press.

de Wit, H., Hunter, F., Howard, L., and Egron-Polak, E. 2015. Internationalization of higher education study. Report for the European Parliament's Committee on Culture and Education. Brussels: European Union. [ Links ]

Enders, J. 2004. Higher education, internationalization, and the nation-state: Recent developments and challenges to governance theory. Higher Education, 47: 361382. [ Links ]

Fijahkowski, L. 2011. China's "soft power" in Africa? Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 29(2): 223-232. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.201L555197 [ Links ]

Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). 2020. About Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. Available at: https://www.focac.org/eng/ltjj3/ltjz/

Foskett, N. 2010. Global markets, national challenges, local strategies: The strategic challenge of internationalization. In Maringe, F., and Foskett, N. (eds.), Globalization and internationalisation in higher education: Theoretical, strategic and management perspectives. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 35-50. [ Links ]

Gray, K., and Gills, B.K. 2016. South-South cooperation and the rise of the Global South. Third World Quarterly, 37(4): 557-574. [ Links ]

Harman, G. 2005. Internationalization of Australian higher education: A critical review of literature and research. In Ninnes, P., and Hellsten, M. (eds.), Internationalising higher education: Critical explorations of pedagogy and policy. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, pp. 119-140. [ Links ]

Haugen, H.0. 2013. China's recruitment of African university students: Policy efficacy and unintended outcomes. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 11(3): 315-334. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2012.750492 [ Links ]

He, W. 2010. The Darfur issue: A new test for China's African policy. In Cheru, F. and Obi, C.I. (eds.), The rise of China and India in Africa. Challenges, opportunities and critical interventions. London: Zed Books, pp. 155-166. [ Links ]

Helms, R., and Rumbley, L.E. 2017. National policies for internationalization-Do they work? In Mihut, G., Altbach, P.G., and de Wit, H. (eds.), Understanding higher education internationalization: Insights from key global publications. Rotterdam, Boston and Taipei: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Huang, M. 2019. Introduction: South-South cooperation and Chinese foreign aid. In Huang, M., Xu, X. and Mao, X. (eds.), South-South cooperation and Chinese foreign aid. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1-22. [ Links ]

King, K. 2014. China's higher education engagement with Africa: A different partnership and cooperation model? International Development Policy: The Graduate Institute of Geneva.

King, K. 2019. Education, skills and international cooperation: Comparative historical perspectives. Hong Kong: Springer. [ Links ]

Knight, J., and de Wit, H. 2018. Internationalization of higher education: Past and future. International Higher Education, 95, 2-4. Available at: https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2018.95.10715 [ Links ]

Larsen, M.A. 2016. Internationalization of higher education: An analysis through spatial, network, and mobilities theories. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Lau, J. 2020. Racism a "barrier" for African students in China. Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/racism-barrier-african-students-china#survey-answer

Li, A. 2018. African students in China: Research, reality, and reflection. African Studies Quarterly, 17(4): 5-44. [ Links ]

Lynch, K. 2006. Neo-liberalism and marketisation: The implications for higher education. European Educational Research Journal, 5(1), 1-17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2006.5.1.1 [ Links ]

McCaig, C., Bowl, M., and Hughes, J. 2018. Conceptualising equality, equity and differentiation in marketised higher education: Fractures and fault lines in the neoliberal imaginary. In Bowl, M., McCaig, C. and Hughes, J. (eds.), Equality and differentiation in marketised higher education: A new level playing field? Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 195-210. [ Links ]

Mihut, G., Altbach, P.G., and de Wit, H. (eds.). 2017. Understanding higher education internationalization: Insights from key global publications. Rotterdam, Boston and Taipei: Sense Publishers. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2019. Statistics for international students in China (20082016). Beijing: Ministry of Education, The People's Republic of China.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2018. Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan (2019-2021). Beijing: Ministry of Education, The People's Republic of China.

Mok, K.H. 2000. Marketizing higher education in post-Mao China. International Journal of Educational Development, 20(2), 109-126. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-0593(99)00062-0 [ Links ]

Mok, K.H. (ed.). 2014. Internationalization of higher education in East Asia: Trends of student mobility and impact on education governance. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mok, K.H., and Chan, Y. 2008. International benchmarking with the best universities: Policy and practice in mainland China and Taiwan. Higher Education Policy, 21(4), 469-486. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2008.21 [ Links ]

Mok, K.H., and Lo, W.Y. 2007. The impacts of neo-liberalism on China's higher education. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 5(1), 316-348. [ Links ]

Mok, K.H., and Ong, K.C. 2014. Transforming from "economic power" to "soft power": Transnationalization and internationalization of higher education in China. In Li, Q. and Gerstl-Pepin, C. (eds.), Survival of the fittest: The shifting contours of higher education in China and the United States. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 133-155.

Niu, C. 2013. China's educational cooperation with Africa: Toward new strategic partnerships. Asian Education and Development Studies, 3(1), 31-45. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-09-2013-0057 [ Links ]

Nixon, E., Scullion, R., and Hearn, R. 2018. Her majesty the student: Marketised higher education and the narcissistic (dis)satisfactions of the student-consumer. Studies in Higher Education, 43(6), 927-943. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1196353 [ Links ]

Nye, J.S. 1990. Soft power. Foreign Policy (80), 153-171. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/1148580 [ Links ]

Peterson, R., Yan, F., and Oxnevad, I. 2022. After Confucius Institutes: China's enduring influence on American higher education. New York: National Association of Scholars. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2020. Outbound internationally mobile students by host region. Available at: http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx?queryid=172

Vavrus, F., and Pekol, A. 2015. Critical internationalization: Moving from theory to practice. FIRE-Forum for International Research in Education, 2(2), 5-21. [ Links ]

Xinhua. 2019. Chinese firm to support Nigeria in building first transportation university. Available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-12/03/c138602801.htm

Yang, R. 2010. Soft power and higher education: An examination of China's Confucius Institutes. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 8(2), 235-245. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14767721003779746 [ Links ]

Zha, Q. 2012. Understanding China's move to mass higher education from a policy perspective. In Hayhoe, R., Li, J., Lin, J., and Zha, Q. (eds.), Portraits of 21st century Chinese universities: In the move to mass higher education. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 20-57. [ Links ]

Received 07 February 2023

Accepted 06 June 2023

Published 18 August 2023