Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.9 no.1 Cape Town Jan./Abr. 2023

ARTICLES

Migrant Networks, Food Remittances, and Zimbabweans in Cape Town: A Social Media Perspective

Sean Sithole

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Institute for Social Development, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. seansithole263@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This study examines the evolving connection between migrant networking on social media and cross-border food remittances in Southern Africa. Emerging research and academic debates have shown that social media platforms transform migration networks. But the role and link between migrant remittances and social media are generally overlooked and neglected. This paper contributes to the ongoing debates by examining the role of social media as a valuable networking tool for food-remitting Zimbabwean migrants. The research is founded on a mixed-methods approach, thus utilizing both questionnaire surveys and in-depth interviews of Zimbabwean migrants in Cape Town, South Africa. The research findings uncover the role of social media in facilitating a regular flow of food remittances back to urban and rural areas of Zimbabwe. A related result is how social media enabled information pathways associated with cross-border food remitting when the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown restrictions limited face-to-face contact. This research can provide valuable insights for academics, researchers, and development practitioners interested in the evolving migration, remittances, and food security nexus in the global South.

Keywords: Food remittances, food security, social media, migrant networks, Zimbabwean migrants

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Social media transforms migration networks (Dekker and Engbersen, 2014), mainly because of the multifaceted ways social media sites such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, and Instagram facilitate inexpensive, accessible, and speedy information pathways for migrants and their networks. Research by McGregor and Siegel (2013) highlights that the utilization of social media initiates and promotes migration, diaspora engagement, integration, and undertaking of migration research. The emergence of social media can offer more prospects for diaspora relations, engagement, discussion, and identity creation (Crush et al., 2011). Dekker and Engbersen (2014) underscore that social media enriches the social networking between migrants and their social ties, such as friends, family, and individuals that can assist in the migration and integration processes. Studies by Pourmehdi and Shahrani (2021), Vilhelmson and Thulin (2013), and Thulin and Vilhelmson (2016) reveal that social media reinforces social networks, which are crucial in impacting migration decisions. Komito (2011) argues that social media also enables social capital among migrants and their networks. Tevera (2014) argues that in Southern Africa, the internet has been pivotal in facilitating transnational urbanism through which the continuity of interrelationships between the country of origin and destination country is maintained. The advancement of social media enables the networking of migrants and their families, relatives, and associates in their homeand host countries.

Social media platforms also minimize the geographical, location, and distance constraints in the communication between migrants and their networks through online interactions. The emerging studies on migration and social media have enriched the comprehension of the role of social media in facilitating migrant networking. However, most of the research and literature that have examined the connection between migration and social media are situated in the global North countries (see Komito, 2011; Charmarkeh, 2013; Dekker et al., 2016; Borkert et al., 2018; Dekker et al., 2018). There is considerably limited evidence on the utilization of social media and information communication technology (ICT) in African migration routes (Stremlau and Tsalapatanis, 2022). According to Akanle et al. (2021), there is a scarcity of research that pays attention to the influential part of ICT and social media in the connections between remittances and international migration in Sub-Saharan Africa. Noteworthy is the emerging attention on the relationship between migration, integration, and social media as a pivotal pathway for communication and information exchange in migration decisions (see Dekker and Engbersen, 2014; Borkert et al., 2018; Akakpo and Bokpin, 2021). But the relationship between social media and migration outcomes - such as remittances - is understudied. To this end, there is a need for research attention on the link between remittances and social media. The latter has the potential to facilitate information flows in migrant networks that can enable the channeling of remittances, such as food transfers.

Previous studies by Crush and Caesar (2018, 2020) have depicted the importance of food remittances, which are commonly overlooked compared to cash transfers. Crush and Caesar (2016) note that the transmission of in-kind remittances, particularly food remittances, has attracted limited attention, mainly because the transfers happen through informal channels. In Africa, there is substantial evidence of vast cross-border and informal transportation of food (Crush and Caesar, 2016) and, more recently, the emergence of digital and mobile technology-based channels to remit food (Sithole et al., 2022). In-kind transfers, such as food remittances are equally important because they reduce food insecurity and enhance access to healthy and adequate food consumption for poor communities. Regarding international transfers to Zimbabwe and the persistent social, economic, and political crisis in the country, studies have illustrated how remittances have been a vital support unit for the livelihoods and consumption of many households (Tevera and Chikanda, 2009; Crush and Tevera, 2010; Sithole and Dinbabo, 2016; Crush and Tawodzera, 2017). This study aims to contribute to the research and dialogues on South-South international migration, remittances, and food security. The article examines the emergence and importance of social media and migrant networks in transmitting food remittance by Zimbabwean migrants in Cape Town, South Africa. The primary facets of the study include the role of social media in the drivers of food transfers, channels of food remittances, characteristics of food remittances, and food remitting challenges.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Narratives on the connection between social media and migration facets have underscored the significance of social networks in human mobility (McGregor and Siegel, 2013; Dekker and Engbersen, 2014). Studies have emphasized how online activity and social media utilization influence migration decisions (McGregor and Siegel, 2013; Vilhelmson and Thulin, 2013; Thulin and Vilhelmson, 2014, 2016; Dekker et al., 2018; Merisalo and Jauhiainen, 2021). Social media enables social networking, group relations, and virtual communities for migrants (Bates and Komito, 2012). Dekker et al. (2018) assert that social media used on smartphones is a vital source of information in migration choices or determinations. Social media causes life to be easier for migrants through the benefits of social networking (Merisalo and Jauhiainen, 2021). Thus, social media platforms are valuable in creating or improving migrant networks, communication, and supplying helpful information. Similarly, Akanle et al. (2021) argue that social media utilization assists international migrants in host locations and their relatives at home to uphold their kinship ties. Social media empowers users to interact and preserve strong links via inexpensive calls/texts and interconnections on numerous sites.

Therefore, ICT facilitates international migration, affords access to sought-after information that stimulates interests, and access to resources, and sustains or reinforces valued kinship networks (Akanle et al., 2021). Correspondingly, social media or social networking tools are crucial in distributing pictures, text, videos, and voice-supported media - rich for robust social groups of friends and other associations to arise among migrants (Komito, 2011). Komito's (2011) research on migrants in Ireland highlights that social media enables virtual communities, strong relations, and bonding capital. Charmarkeh (2013) indicates that migrants, such as refugees in France, utilize social media, which is vital for navigating migratory routes and settling in locations that accept migrants. A study by Dekker et al. (2016) of migrants in Western European countries shows that online and social media are vital for interaction in migration networks. Alencar (2018) shows that refugees in the Netherlands utilize social media to integrate into the host country and communicate with friends and family in their countries of origin to acquire emotional and social support. Borkert et al. (2018), in their study of migrants in Germany, illuminate that smartphones, online interactive tools, and social media facilitate communication between migrants and their families and associates.

Social media is also significant for forming and sustaining social networks between migrating people and those who migrated before (Borkert et al., 2018). Ulla (2021) illustrates how Filipino transnational migrants in Thailand use social media sites to be updated on occurrences, news, and political events in their country of origin and reconnect with associates, relatives, and families. Ennaji and Bignami (2019) underscore the importance of social media and smartphones in expanding migration movements in Morocco. Mobile technologies and smartphones enable the utilization of social media apps such as WhatsApp and Facebook and global positioning apps and maps, which facilitate access to valuable online information when migrating. The above literature expands the understanding of the link between migration and social media. Nevertheless, most studies have mainly centered on migration and social media; limited attention has been given to migration outcomes such as remittances. For example, the connection between remittances and social media has been scarcely investigated. Studies by Crush and Caesar (2016, 2018, 2020) and Sithole et al. (2022) on food remittances note the role of reciprocity and social networks in transmitting goods. Social networks, ties, and trust between migrants and their networks, such as families and associates, offer helpful information essential for the transfer of remittances. Therefore, social media can enable interactions and information exchange in migrant networks to facilitate the transfer of goods, such as food remittances.

SOCIAL CAPITAL THEORY

This paper used the social capital theory as the theoretical basis to examine the utilization of social media in food remittances because it affords insights into how social networking is vital in the food remitting process. Putnam (1993) refers to social capital as the "features of social organisation, such as networks, norms, and trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit." Accordingly, social capital can help people use social ties to access resources (Agbaam and Dinbabo, 2014; Dinbabo et al., 2021). There are three forms of social capital:

bonding, bridging, and linking. First, Woolcock (2001) posits that bonding social capital occurs in homogeneous social ties with strong links like family, neighbors, or close friends. Second, bridging social capital involves weak connections or heterogeneous social links (Mahmood et al., 2018). Third, linking social capital comprises the relations between the public and those in power or authority (Kyne and Aldrich, 2020). Importantly, social capital, especially bonding and bridging, can be utilized to illuminate the significance of social media use in the setting of food remittances. For example, bonding and bridging social capital between migrants and their close and distant ties, such as household and family members, associates, and other compatriots, help to reveal insights into the role of migrant networks on social media in cross-border food remitting.

METHODOLOGY

This study is based on research undertaken in Cape Town, South Africa, on Zimbabwean migrants. South Africa is one of the leading destinations for these migrants (Crush et al., 2015). Also, Cape Town is a popular destination for international migrants (Rule, 2018). South Africa and cities such as Cape Town attract international migrants because of employment and economic prospects. The researcher conducted the primary data gathering in 2020 in the northern and southern suburbs of Cape Town in Bellville, Wynberg, Claremont, Kenilworth, and Rondebosch. The specific study areas are popular spaces among international (African) migrants because of the residential, entrepreneurial, and educational prospects and being social and economically vibrant spaces. To ensure diverse representation in the research, the researcher included respondents from various categories: backgrounds, locations, professions, education, gender, and age.

The study used a questionnaire instrument on 100 participants and in-depth interviews with ten respondents in a mixed-methods approach, collecting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data. The researcher used STATA 13.0 statistical software for quantitative data analysis, and adopted a thematic approach for qualitative data analysis. The combination of questionnaire and in-depth interviews was valuable in providing comprehensive data on the connection between food remittances, migrant networks, and social media. The sampling techniques employed in the research were purposive and snowballing for the in-depth interviews and questionnaire surveys - interviewed Zimbabwean migrants provided referrals that helped reach more participants. This was decisive in accessing participants, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic environment. The limitation of the study was that the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns, and mobility restrictions made it challenging to locate participants. However, social networks and referrals were crucial in reaching the participants. The researcher observed all ethical practices in the study, including obtaining consent, being granted permission, obtaining ethical clearance, and maintaining confidentiality and anonymity.

FINDINGS

Demographic and background data

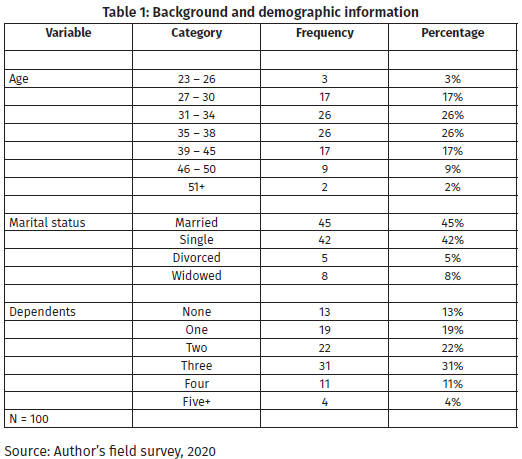

The respondents in the study were from diverse profiles and backgrounds. The age groups comprised economically active persons between 23 and 60 years old (see Table 1), with 50 males and 50 females (not predetermined). Most respondents (75%) were household breadwinners, with 15% of husbands and 10% of wives as breadwinners. The majority of the participants had one or more dependents, and most of the respondents were married (45%) or single (42%) (see Table 1). The respondents were from varying income groups and diverse economic circumstances.

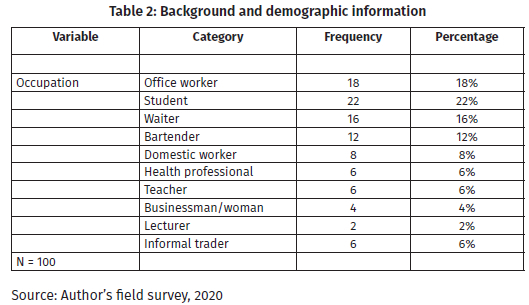

Table 2 portrays that the participants' occupations ranged from lecturers, teachers, health professionals, and office workers to blue-collar workers such as informal traders and domestic workers. Most respondents (77%) completed university education, 17% attained secondary education, and 6% completed primary education. The researcher obtained the qualitative results from the narratives of individuals aged between 27 and 59 - six males and four females. The participants' occupations were lecturers, office workers, postgraduate students, teachers, waiters (servers), gardeners, and bartenders.

Drivers of food transfers and social media

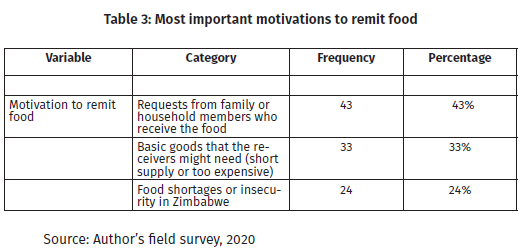

Table 3 depicts the most important motivations to remit food: 43% of the respondents transferred food because of requests from households or family members back in their home country; 33% because the food items were essential groceries that the recipients might need; and 24% because of food shortages or food insecurity back in the country of origin.

The participants' narratives explained that the drivers of transmitting food items were socioeconomic constraints in the country of origin, requests from relatives and family members, and high food prices in Zimbabwe. One of the respondents (Participant 5, 23 August 2020, Bellville) stated, "I am influenced by the shortages, you know, they communicate with me sometimes to say, 'We have run out of basics." In addition, a participant (Participant 1, 28 April 2020, Claremont) remarked: "My reasons for sending back food are mainly based on the requests made by my family."

The part played by social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter as the drivers of the transfer of food was evident in the study. Consequently, 66% of the respondents noted that they were inspired to transfer food items to Zimbabwe because of the communication- or information-sharing on social media by the household or family members in the country of origin. Furthermore, 54% indicated that they are linked to and interact with family or household members, who request them, on social media, to transfer food and groceries. Additionally, 44% revealed that they transmit food items to Zimbabwe because of the content they see on social media, such as socioeconomic circumstances, food prices, food insecurity, food shortages in Zimbabwe, and remitting channels.

Moreover, 40% of the participants specified that the decision to transfer food items was influenced by their interaction with friends and the content they share or post on social media. Similarly, the participants highlighted the influence of the interactions on social media on their reasons for transferring food back home. For example, one participant (Participant 2, 10 September 2020, Bellville) explained:

So, I communicate with a lot of my siblings through WhatsApp. So, you know, sometimes they tell you about the situation back home, and in that way, you are aware that, okay, maybe you need to try and make sure you can send something and make sure you know, they get something to eat.

The respondents also revealed the importance of news updates on social media that illustrated the challenging conditions back in Zimbabwe that prompted them to remit food items. These challenges included food shortages, food insecurity, and starvation. In this regard, a participant (Participant 1, 28 April 2020, Claremont) explained:

I have also connected on social media to news reporting. So, you will find that certain things also come up there. But I mean, when I read some things, and you read, you know, the statistics of the individuals or the numbers of individuals that are starving or the individuals that are struggling with food security.

This respondent added that the challenges revealed on social media news updates, such as hunger and food insecurity initiated the decision to find solutions and communicate with family members in Zimbabwe:

The automatic reaction becomes to engage. I engage with my own family about, you know, the situation that they are in because I have a sibling at home. I also engage about how I can assist. So, the awareness is there. It then triggers me to investigate how much it relates or how the food insecurity in Zimbabwe is affecting my family.

The Zimbabwean migrants explained that the information shared by the digital/ mobile food remittance service providers and the content shared by the companies influence their decisions to remit. For example, the information shared by Malaicha and Mukuru on their social media pages regarding specials and discounts impacted the food remitting decisions.

Characteristics, channels of food remittances, and social media

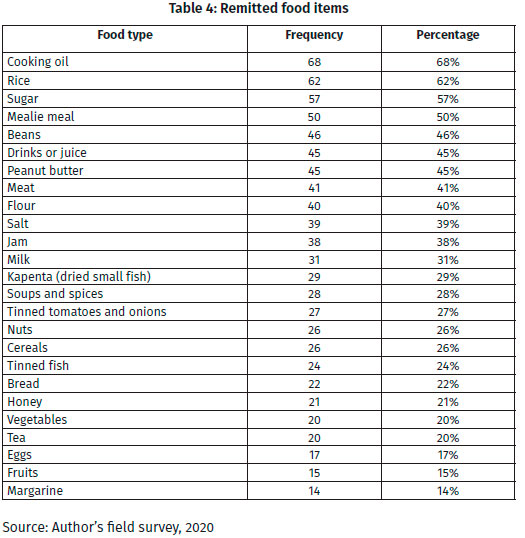

Table 4 shows that the transferred food items generally comprised cooking oil, rice, sugar, mealie meal, beans, juice or drinks, peanut butter, meat, flour, and salt, among others. The common foodstuffs transferred are diverse, comprising staple foods in Zimbabwe, grain-based food, perishable and non-perishable foods. The majority of the respondents indicated that they did not predetermine the regularity of the food transfers to their home country. Resultantly, most individuals transferred food remittances whenever possible (59%), whereas only 14% tranferred every month, another 14% once a year, 9% twice a year, and 4% every three months.

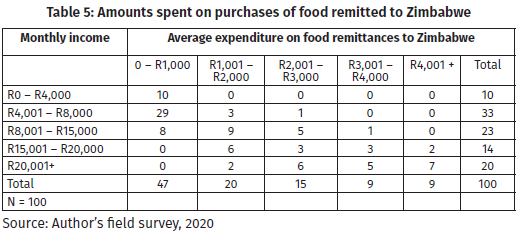

Noteworthy in the research was an association between the amount used on purchasing food each time they remitted food and the average monthly incomes. For instance, all those who had monthly incomes of R0-R4,000 transmitted food items priced at R1,000 or less, and most of those who transferred food items valued between R3,001-R4,000+ had monthly earnings of R15,001 or more (see Table 5).

The research results specified that 48% of the participants primarily transferred food items to Zimbabwe through digital/mobile channels, 33% via transport carriers, 11% via family, relatives, friends, or associates, and 8% personally. To demonstrate the importance of digital/mobile channels, one participant (Participant 9, 19 September 2020, Wynberg) indicated that, "I was using buses to send my family some groceries. But because the pandemic caused the border to close, I decided to use the Malaicha and Mukuru services on my phone." The significance of digital/ mobile channels as reliable, inexpensive, accessible, and speedy channels was also highlighted in the narratives of the Zimbabwean migrants. Informal channels were also crucial, particularly during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions, and lockdowns. These migrants displayed resilience and coping strategies by using uncommon channels of transmitting food remittances to their home country. For example, one respondent (Participant 3, 20 May 2020, Kenilworth) revealed that,

... so, the regular forms of transportation I used could not work because the borders were closed, but because funeral companies were allowed to move around for repatriation purposes, I also had to resort to using that [channel]

The respondents explained that the information sharing and interaction on social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp provided helpful information or awareness of the dependable, accessible, and inexpensive channels to use for sending food. For example, one respondent (Participant 3, 20 May 2020, Kenilworth) explained:

On the Zimbabweans in Cape Town's Facebook page, and when we were under level-five lockdown, many people were also asking on social media how people who have urgent requests from Zimbabwe are sending through the things . somebody wrote that they were also working with a funeral company that repatriates bodies of deceased Zimbabweans. And that's how they were getting their goods through.

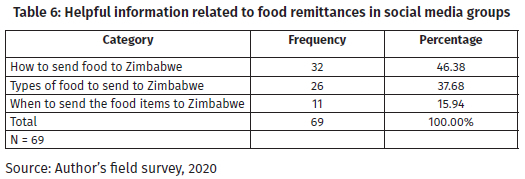

The participants used social media sites like Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp to communicate and acquire valuable information related to food remittance transfers. Social capital and social networking in social media groups proved to be invaluable. For instance, 69 participants were in various social media groups. Among the 69 participants in social media groups, several groups were with friends (24.64%), family or household members (53.62%) and fellow Zimbabweans (21.74%). Interaction and information in social media groups assisted remittance-sending migrants in choosing the channels to remit food (46.38%), the frequency of food transfer (15.94%) and the types of food to transmit (37.68%) (see Table 6).

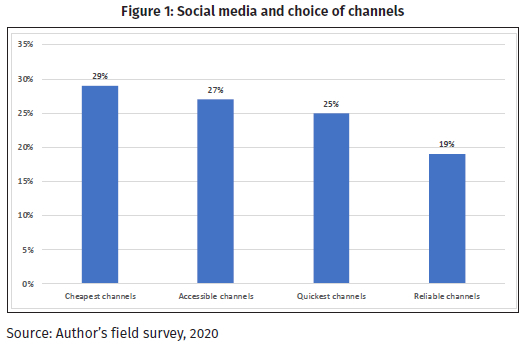

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of the respondents in the study indicated that social media interaction through texts or voice-messaging influenced their choice of most-frequently used channels to remit food. Additionally, 58% of the participants noted that social media content such as news and posts influenced their choice of preferred food transferring channels. Furthermore, the study showed the significance of social media communication and content in accessing the channels deemed dependable (19%), reachable (27%), affordable (29%), and the speediest (25%) (See Figure 1).

Also, the findings confirmed that social media plays a central role as a pathway to remitting food. For example, one Zimbabwean migrant explained that digital/mobile remittance service providers like Mukuru allow consumers to complete orders and create transactions on social media platforms like WhatsApp. Another respondent (Participant 3, 20 May 2020, Kenilworth) indicated how social media helped channel food to Zimbabwe by saying, "When I had to decide who to use and how to send [food], I needed to do some social media research to find out what people are saying about the service that I'm intending on using." Another participant (Participant 1, 28 April 2020, Claremont) explained how social media facilitates interactions, information flow, and the purchase of proposed food items to remit:

Social media enables individuals to communicate via WhatsApp even, you know, engaging and making purchases. You can find links on social media to shops you might want to buy from. And also, you can share all of this information via WhatsApp and social media.

The narratives of the Zimbabwean migrants emphasized the crucial nature of social networking and social capital in social media groups on platforms such as WhatsApp and Facebook in transferring food remittances, as expressed by this participant:

I mean, on almost all the groups I'm part of, I think we have several family groups with different family members. I mean, we have a group for our nuclear family, we have groups who are extended families from the mother's side, from the father's side, we have church groups that I'm part of, I'm in groups with friends. And in all those groups, at some point, we discussed the escalating food prices in Zimbabwe (Participant 3, 20 May 2020, Kenilworth).

The discussions in the social media groups included transfer channels, food prices, and the circumstances in the migrants' home country. For instance, this participant (Participant 3, 20 May 2020, Kenilworth) added:

... as those conversations go, we talk about how we, as migrants in South Africa, can send things home, and we also get the opportunity to ask how other people are also sending home, so in all those groups. I can't think of any group where at some point, we have not had a discussion on sending things to Zimbabwe and just sharing ideas and suggestions on which way or method is best to use.

Social media is also helpful in facilitating the transfer of remittances through interactions between migrants and their networks. For example, because of the long distance between Cape Town and food delivery locations in Zimbabwe, migrants use social media to facilitate the cheaper transfer of remittances from other South African cities closer to Zimbabwe, such as Johannesburg. A respondent (Participant 4, 12 July 2020, Claremont) said:

You could get information, for example, who's in Joburg, and who's going back home. And some of the contacts of the people that I used to check stuff in Joburg, and people that I've met on social media, and I get information from them, or they give you contact details of the cheapest driver, or they are the ones that go and collect the stuff for me or buy stuff for me. So social media has provided the human resources and information.

Food remittance challenges and social media

Informal ways of transferring food remittances present problems such as confiscation of goods by border officials, import-duty issues, delivery delays, and broken/ destroyed/stolen/misplaced goods. In this study, the challenges encountered when transferring food remittances comprised: delivery delays (22%), broken/destroyed goods (11%), misplaced/stolen goods (11%), high remittance costs (21%), while 35% of participants experienced no challenges. Other challenges were internet problems, erroneous transactions, and bureaucratic registration to use digital/mobile channels. This study's findings highlighted the importance of social media platforms in addressing the challenges encountered by Zimbabwean migrants when transmitting food back to their home country. In this regard, 44% of participants indicated that social media posts, exchange of information, and communication assisted in solving some of the challenges they encountered when sending food to Zimbabwe. This was corroborated in the narratives of the Zimbabwean migrants. For instance, a respondent (Participant 3, 20 May 2020, Kenilworth) remarked:

Sometimes you find a post that somebody would have posted; we encounter a similar problem by the same person or with the same person. And sometimes you'll find that the person is in the habit of lying to people to say, "I've been arrested, and I need you to pay an extra 500." You get people that will also tell you, maybe five or ten people will come up and say, "No, this guy is a crook; he's not telling the truth."

The narratives of the Zimbabwean migrants also revealed the importance of content sharing, feedback, and reviews on social media regarding the remittance channels. For example, the above participant added:

Because sometimes their service is not good. And when there is an outcry on social media, people call out the bus company, naming and shaming them. It always invites the top or senior management of those bus services to come up and say, "You know, we apologize."

The respondents demonstrated how social media helps address challenges, such as access to specific channels during the COVID-19 pandemic and resultant border closures. This was done by asking questions on social media and using feedback to make decisions. For example, the above participant also said:

On Facebook, we have done that, asked the question, and people responded to say, "Well, use this person or use this company, they can move"... During the lockdown, I asked how I could send groceries since the borders were closed.

The use of mobile devices, smartphones, and social media was valuable in online communication and facilitating the information flow in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and limited physical contact. A participant (Participant 1, 28 April 2020, Claremont) stated:

I think, you know, the biggest challenge with food remitting on the basis of COVID is human-to-human contact. So, social media assists in communicating specific information .

Social media also facilitates virtual communities and online interactions for migrants and their networks that enable the transfer of food remittances. This proved to be useful in overcoming the practicality and challenges of having face-to-face communication. The above respondent added:

... social media allows people to remit and send their items without physical contact. By this, what I mean is, be it via courier or even via a family member, you don't necessarily have to get in physical contact with anyone to get the food you would like to courier across.

DISCUSSION

Diasporas utilize social media or social networking sites (SNSs) for various online networking actions (Crush et al., 2011). Borkert et al. (2018: 8) note that "migrants are digital agents of change who themselves post and share information in social media and digital social networks." The Zimbabwean migrants demonstrated the vital role social media platforms, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Twitter, play in migrant social networking and the transfer of food remittances. The study results are consistent with the studies that have drawn attention to the importance of social media, migrant networks, and migration decisions (McGregor and Siegel, 2013; Dekker and Engbersen, 2014; Akakpo and Bokpin, 2021). From the perspectives of the Zimbabwean migrants, their decisions to transfer food remittances were influenced by content viewing, information sharing and communications on social media with household or family members, friends, and associates. Notably, the information sharing and interactions on social media important to the transfer of food were about food requests, food shortages, food insecurity, food prices, socioeconomic situations in the country of origin, remittance needs, and transfer channels. Similar perspectives emerge in previous studies by Crush and Tevera (2010), Tevera and Chikanda (2009), Ramachandran et al. (2022), and Sithole et al. (2022) that underscore the persistent economic crisis (including unemployment, food insecurity, food shortages, and hyper-inflation) in Zimbabwe as one of the main drivers of remittances to Zimbabwe. Migrant remittances support households and family members back in Zimbabwe, especially during economic shocks.

Additionally, the Zimbabwean migrants highlighted that news updates, posts, and reviews on social media influenced food-remitting decisions. The interaction and content on social media platforms also consisted of issues related to food remittances, such as food promotions or discounts by remitting businesses. The marketing, promotions, and discounts on social media can attract consumers to use food-remitting services. Thus, the advertising and marketing by food-remitting companies can drive migrants to utilize their affordable services and purchase food to remit. Social media is resourceful for valuable information flows that impact the decisions to transfer food items, such as sharing information within or between the host and origin locations. The study corroborates Dekker and Engbersen's (2014) assertion that social media platforms transform migrant networks and provide a wealthy base for insider information on migration that is distinct and informal. Hence, social media sites offer valuable tools that facilitate the flow of information and trigger the decisions to remit food. From the standpoint of the Zimbabwean migrants, social media enables the formation of online communities that enhance mutual decision-making. Hence, it facilitates a collective sense of obligation to support and transfer food remittances to family members back home.

The Zimbabwean migrants utilize various channels to transfer food remittances, such as digital/mobile and informal sources (personally, associates, family members, relatives, and transport carriers). This study mirrors the viewpoints in earlier works by Nzima (2017), Nyamunda (2014), Maphosa (2007) and more recently by Sithole et al. (2022), that Zimbabwean migrants utilize both formal and informal channels to transfer remittances to their family members and households back home. Also, in Southern Africa, new patterns show that mobile and digital technologies are now facilitating the transmission of groceries, including food remittances through companies such as Malaicha and Mukuru Groceries (Sithole, 2022; Sithole et al., 2022). A study by Tevera and Chikanda (2009) posits that social ties, social networks, information flows and personal relations between migrants, family members, and associates impact the decisions to use specific channels when transferring remittances to Zimbabwe from neighboring countries. Strikingly, the Zimbabwean migrants illustrated that social networking on social media with family and household members, friends, and companions helped them decide on the most accessible, cheapest, speediest, and most reliable channel to use in transmitting food. Social media sites also facilitated the interaction between Zimbabwean migrants and transport carriers at various stages before and after the transportation of food items. For instance, the communication between food-sending migrants and transporting carriers comprised the channeling costs, border tariffs, delivery status, and situation in Zimbabwe.

Social media is an essential source of information for migrants (Dekker et al., 2018). The Zimbabwean migrants narrated that their preferences for specific channels were based on social media reviews, sentiments, and information regarding the dependability of these channels. Remarkably, social media was used as a channel to transfer food. Accordingly, it was illustrated that digital/mobile remitting companies have alternatives to complete transactions or make orders on social media platforms. Social media provides informative information on the most accessible channel, especially during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic and resultant limitations such as movement or transport restrictions. For example, information on social media provided insights into border closures and limited transport movement. And decisively, social media information provided details on how funeral firms were permitted to carry on their business. And in turn, the Zimbabwean migrants were clandestinely transferring foodstuffs through the funeral companies. Social media enables the virtual interaction and flow of information that facilitates the channeling of food remittances.

Scholars have indicated the connection between migration, remittances, and social capital (Akanle et al., 2021). The study highlighted the significance of social capital and social networking on social media sites like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Twitter among the Zimbabwean migrants and their associates, which are essential in transferring food remittances. Accordingly, the article indicated that personal and group ties were beneficial in deciding on the foodstuffs to remit, the period to remit, and choosing the dependable, inexpensive, and accessible remittance channels. For example, communication and exchange of ideas on social media groups between the Zimbabwean migrants and their strong and close relations, like friends, household and family members, were crucial in transmitting food. Social networking with strong and close ties, such as among family members and friends, is described as bonding social capital (Dressel et al., 2020). Social media efficiently enables strong relations and bonding social capital, indicating a new manifestation of virtual migrant communities (Komito, 2011). Also, social media can assist migrants and their networks in navigating the spaces and places they occupy by enabling communication and exchanging helpful information. Social media networking and content exchanges are not restricted by location and distance because contact occurs online.

Social networking on social media groups between the Zimbabwean migrants and distant ties, like other Zimbabweans and associated church members, was crucial in providing helpful information on low-cost and accessible food remittance channels. The distant or weak links in social capital are known as bridging social capital (Woolcock, 2001). Thus, bonding and bridging social capital on social media were essential in providing valuable information on food remittance and facilitating the channeling of food items. Correspondingly, a study by Merisalo and Jauhiainen (2021) demonstrates that social media usage is associated with social ties and social capital among migrant networks. Social media promotes networking and social capital that assist in channeling food remittances. Zimbabwean migrants operate in transnational spaces and engage in virtual communities on the internet that enable them to maintain ties between origin and destination spaces (Tevera, 2014). Social media groups facilitate the creation of online networks for migrants and their family members, relatives, and associates, which generate a rich source of helpful information on migration and remittance issues.

When remitting food through informal channels, the challenges included delivery delays, and broken, lost, or stolen goods. The study's findings support previous studies by Tevera and Chikanda (2009), Maphosa (2007), and Nzima (2017). They note that migrants who transferred remittances to their households and families in Zimbabwe through informal channels regularly encountered challenges, such as theft, delivery delays, and undependable remittance carriers. However, undocumented and unbanked migrants without regular jobs continued to depend mainly on informal channels because the passages were cheap and more accessible. Digital/mobile or formal channels presented challenges, such as poor internet access, transaction problems, and costly charges. Social media plays a crucial role in addressing some of the difficulties encountered when remitting food because of being accessible, affordable, and speedy. Pourmehdi and Shahrani (2021) concur on the importance of social media sites by indicating that they are essential to migrant networks because they offer smooth, accessible communication resources. The capability of social media as a resource that facilitates information flow was vital for the Zimbabwean migrants. Social media reviews and posts also addressed the challenges of poor service delivery and unreliable transfer channels. For example, reviews on social media uncovered undependable remittance carriers and provided valuable information on reliable remittance carriers. The posts, reviews, and communication on social media can provide information on untrustworthy transport carriers and afford suggestions on the cheapest, dependable, and accessible transport carriers to use when transmitting food. Therefore, social media can link virtual communities and offline activities, such as arranging and transferring food remittances.

Scholars have indicated how the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the food systems and the movement of people and goods (Crush and Si, 2020; Paganini et al., 2020; Crush et al., 2021). Dinbabo (2020) asserts that the COVID-19 pandemic threatens the stability of people's economic and social well-being, as well as their overall health care. Some of the challenges encountered because of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as movement restrictions, were lessened by social media. For example, social media enabled virtual communication between Zimbabwean migrants, associates, and transport carriers. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, social media can offer valuable and speedy distribution channels for vital information (Chan et al., 2020). Social media can lessen the hindrance of the distance between migrants and their networks by providing online communication opportunities. Also, social media facilitated the online purchase of food items and enabled the remitting of the food items. Social media sites can assist in the buying and transferring of food remittances through their capacity to facilitate transactions, content sharing and information flow in text, image, video, and audio forms. Social media has valuable tools that offer inexpensive, instant, and reachable channels for unlimited information pathways, which migrants and their networks can utilize to facilitate undertakings such as remittances. However, as highlighted in the study, access to social media sometimes has constraints such as limited access to smartphones, mobile devices, mobile data, power, or internet connectivity.

CONCLUSION

This study has contributed to the discussions and research on South-South migration, remittance flows, and food security. At the center of the study is the influence of social media on how Zimbabwean migrants in Cape Town are transferring food remittances to their families left behind in their home country. Social media enables online interactions and virtual communities for migrants and their networks, which are valuable for migration and remittance choices. The study illustrated how the drivers, channels, and nature of transferring foodstuffs back home are influenced by the content sharing, information flow, and communication between the migrants and friends, associates, family members, and carriers. A noteworthy finding of the research was that social media offered reachable, convenient, and inexpensive communication channels during the COVID-19 pandemic when movement restrictions and lockdowns disrupted face-to-face interactions. Social media can provide rapid, affordable, reliable, and accessible communication passages that are useful for migrant communities and the transfer of remittances. This article provided insights into how social media facilitates information pathways for migrants and their networks when transferring food remittances. Accordingly, researchers and development policymakers need to pay more attention to food remittances and digital innovations, such as social media, that facilitate the cross-border flow of food. Social media influences migrant networks and transmission of cross-border remittances, such as food transfers, which are essential for food security in the global South.

REFERENCES

Agbaam, C. and Dinbabo, M.F. 2014. Social grants and poverty reduction at the household level: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Journal of Social Sciences, 39(3): 293-302. [ Links ]

Akakpo, M.G. and Bokpin, H.A. 2021. Use of social media in migration decision making. Journal of Internet and Information Systems, 10(1): 1-5. [ Links ]

Akanle, O., Fayehun, O.A. and Oyelakin, S. 2021. The information communication technology, social media, international migration and migrants' relations with kin in Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(6): 1212-1225. [ Links ]

Alencar, A. 2018. Refugee integration and social media: A local and experiential perspective. Information, Communication & Society, 21(11): 1588-1603. [ Links ]

Bates, J. and Komito, L. 2012. Migration, community and social media. In Boucher, G., Grindsted, A. and Vicente, T.L. (eds.), Transnationalism in the global city. Maior Series, Vol 6. Bilbao: University of Deusto, pp. 97-112. [ Links ]

Borkert, M., Fisher, K.E. and Yafi, E. 2018. The best, the worst, and the hardest to find: How people, mobiles, and social media connect migrants in(to) Europe. Social Media + Society, 4(1): 1-11. [ Links ]

Chan, A.K., Nickson, C.P., Rudolph, J.W., Lee, A. and Joynt, G.M. 2020. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: Early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia, 75(12): 1579-1582. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057 [ Links ]

Charmarkeh, H. 2013. Social media usage, tahriib (migration), and settlement among Somali refugees in France. Refuge: Canada's Journal on Refugees, 29(1): 43-52. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Caesar, M. 2016. Food remittances: Migration and food security in Africa. SAMP Migration Policy Series, No 72. Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), Waterloo, ON.

Crush, J. and Caesar, M. 2018. Food remittances and food security: A review. Migration and Development, 7(2): 180-200. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Caesar, M. 2020. Food remittances and food security. In Crush, J., Frayne, B. and Haysom, G. (eds.), Handbook on urban food security in the Global South. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 282-306. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786431516

Crush, J. and Si, Z. 2020. COVID-19 containment and food security in the Global South. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(4): 1-3. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Tawodzera, G. 2017. South-South migration and urban food security: Zimbabwean migrants in South African cities. International Migration, 55(4): 88-102. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Tevera, D.S. (eds.). 2010. Zimbabwe's exodus: Crisis, migration, survival. Cape Town and Ottawa: SAMP and IDRC. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Tawodzera, G. 2015. The third wave: Mixed migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa. Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines, 49(2): 363-382. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Thomaz, D. and Ramachandran, S. 2021. South-South migration, food insecurity and the COVID-19 pandemic. MiFood Paper No 1, Waterloo, ON.

Crush, J., Eberhardt, C., Caesar, M., Chikanda, A., Pendleton, W. and Hill, A. 2011. Social media, the internet and diasporas for development. SAMP Migration Policy Brief, No 26. Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), Waterloo, ON.

Dekker, R. and Engbersen, G. 2014. How social media transform migrant networks and facilitate migration. Global Networks, 14(4): 401-418. [ Links ]

Dekker, R., Engbersen, G. and Faber, M. 2016. The use of online media in migration networks. Population, Space and Place, 22(6): 539-551. [ Links ]

Dekker, R., Engbersen, G., Klaver, J. and Vonk, H. 2018. Smart refugees: How Syrian asylum migrants use social media information in migration decision-making. Social Media + Society, 4(1): 1-11. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M.F. 2020. COVID-19 and evidence-based policymaking (EBP): A call for a continental-level research agenda in Africa. African Journal of Governance & Development, 9(1.1): 226-243. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M.F., Badewa, A.S. and Yeboah, C. 2021. Socio-economic inequity and decision-making under uncertainty: West African migrants' journey across the Mediterranean to Europe. Social Inclusion 9(1): 216-225. [ Links ]

Dressel, S., Johansson, M., Ericsson, G. and Sandström, C. 2020. Perceived adaptive capacity within a multi-level governance setting: The role of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital. Environmental Science & Policy, 104: 88-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.11.011 [ Links ]

Ennaji, M. and Bignami, F. 2019. Logistical tools for refugees and undocumented migrants: Smartphones and social media in the city of Fès. Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisation, 13(1): 62-78. [ Links ]

Komito, L. 2011. Social media and migration: Virtual community 2.0. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(6): 1075- 1086. [ Links ]

Kyne, D. and Aldrich, D.P. 2020. Capturing bonding, bridging, and linking social capital through publicly available data. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 11(1): 61-86. [ Links ]

Mahmood, Q.K., Zakar, R. and Zakar, M.Z. 2018. Role of Facebook use in predicting bridging and bonding social capital of Pakistani university students. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 28(7): 856-873. [ Links ]

Maphosa, F. 2007. Remittances and development: The impact of migration to South Africa on rural livelihoods in southern Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa, 24(1): 123-136. [ Links ]

McGregor, E. and Siegel, M. 2013. Social media and migration research (No. 2013068). United Nations University-Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute on Innovation and Technology (MERIT). Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/unm/unumer/2013068.html

Merisalo, M. and Jauhiainen, J.S. 2021. Asylum-related migrants' social-media use, mobility decisions, and resilience. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 19(2): 184-198. [ Links ]

Nyamunda, T. 2014. Cross-border couriers as symbols of regional grievance? The Malayitsha remittance system in Matabeleland, Zimbabwe. African Diaspora, 7(1): 38-62. [ Links ]

Nzima, D. 2017. Channelling migrant remittances from South Africa to Zimbabwe: Opportunities and obstacles. Alternation Journal, 24(1): 294-313. [ Links ]

Paganini, N., Adinata, K., Buthelezi, N., Harris, D., Lemke, S., Luis, A., Koppelin, J., Karriem, A., Ncube, F., Nervi Aguirre, E., Ramba, T., Raimundo, I., Sulejmanovic, N., Swanby, H., Tevera, D. and Stöber, S. 2020. Growing and eating food during the COVID-19 pandemic: Farmers' perspectives on local food system resilience to shocks in Southern Africa and Indonesia. Sustainability, 12(20): 8556. [ Links ]

Pourmehdi, M. and Shahrani, H.A. 2021. The role of social media and network capital in assisting migrants in search of a less precarious existence in Saudi Arabia. Migration and Development, 10(3): 388-402. [ Links ]

Putnam, R. 1993. The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect, 13: 35-42. [ Links ]

Ramachandran, S., Crush, J., Tawodzera, G. and Onyango, E. 2022. Pandemic food precarity, crisis-living and translocality: Zimbabwean migrant households in South Africa during COVID-19. SAMP Migration Policy Series, No 85. Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), Waterloo, ON.

Rule, S. 2018. Migrants in Cape Town: Settlement patterns. HSRC Review, 16(4): 1921. [ Links ]

Sithole, S. 2022. The evolving role of social media in food remitting: Evidence from Zimbabwean migrants in Cape Town, South Africa. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Sithole, S. and Dinbabo, M.F. 2016. Exploring youth migration and the food security nexus: Zimbabwean youths in Cape Town, South Africa. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 2(2): 512-537. [ Links ]

Sithole, S., Tevera, D. and Dinbabo, M.F. 2022. Cross-border food remittances and mobile transfers: The experiences of Zimbabwean migrants in Cape Town, South Africa. Eutopía. Revista de Desarrollo Económico Territorial, 22: 10-32. [ Links ]

Stremlau, N. and Tsalapatanis, A. 2022. Social media, mobile phones and migration in Africa: A review of the evidence. Progress in Development Studies, 22(1): 56-71. [ Links ]

Tevera, D. 2014. Remaking life in transnational urban space: Zimbabwean migrant teachers in Manzini, Swaziland. Migracijske i etnicke teme, 30(2): 155-170. [ Links ]

Tevera, D. and Chikanda, A. 2009. Migrant remittances and household survival in Zimbabwe. SAMP Migration Policy Series, No 51. Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), Waterloo, ON.

Thulin, E. and Vilhelmson, B. 2014. Virtual practices and migration plans: A qualitative study of urban young adults. Population, Space and Place, 20(5): 389-401. [ Links ]

Thulin, E. and Vilhelmson, B. 2016. The internet and desire to move: The role of virtual practices in the inspiration phase of migration. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 107(3): 257-269. [ Links ]

Ulla, M. 2021. Understanding the social media news consumption among Filipinos as transnational-migrants in Thailand. Asia-Pacific Social Science Review, 21(1): 60-70. [ Links ]

Vilhelmson, B. and Thulin, E. 2013. Does the internet encourage people to move? Investigating Swedish young adults' internal migration experiences and plans. Geoforum, 47: 209-216. [ Links ]

Woolcock, M. 2001. The place of social capital in understanding social and economic outcomes. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1): 11-17. [ Links ]

Received 01 March 2022

Accepted 17 January 2023

Published 30 April 2023