Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.8 no.2 Cape Town Mai./Ago. 2022

ARTICLES

Destination Substitution and Social Networks among Urban Refugees in Kampala, Uganda

Francis AnyanzuI; Nicole De Wet-BillingsII

IUniversity of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

IIUniversity of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

ABSTRACT

A significant number of refugees and asylum seekers live in Kampala as opposed to the rural settlement areas. However, what is less known is the extent of destination substitution among these refugees and factors associated with changes in destination. Using a survey of 479 refugees from eight nationalities, this study examined the influences of social networks on destination substitution among refugees in Kampala. It found that more than half of the refugees substituted their initially intended destination with Kampala. Refugees with social network ties in Kampala are likely to substitute their preferred destination for Kampala compared to those who do not have social network ties in Kampala. The study contributes to the literature on destination choices and social networks by showing that the refugees have destination preferences, but these preferences can be constrained by prevailing circumstances. Facilitated by social networks with alternative destinations, refugees may substitute their preferred destinations with a proxy destination in cities in neighboring countries.

Keywords: social networks, change, destination, refugees, Kampala

INTRODUCTION

Over 6% of the refugees and asylum seekers in Uganda live in Kampala and its metropolitan areas (UNHCR, 2020). The majority of the refugees are from the Horn of Africa, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Kampala also hosts a significant number of refugees from Burundi, South Sudan, Rwanda, and Sudan. Moreover, Ugandan laws allow free movement of refugees, implying that refugees can relocate from settlement areas, cities, and rural areas in Uganda to Kampala. However, free movement is possible where one has evidence of self-sufficiency and the prevailing political regime remains favorable to refugees (Republic of Uganda, 2006; Iazzolino and Mohamed, 2019). Refugees also cross to Kampala from their first countries of asylum in the neighboring countries. Refugees and asylum seekers are among the main contributors to the urbanization of Kampala (UBOS, 2019). Some of these refugees have lived in a protracted refugee situation in Kampala for over five years (Gusman, 2018). However, many urban refugees face difficulties in securing stable livelihoods, accessing social services, and building trust across communities (Den Boer, 2015; Lyytinen, 2015; AGORA, 2018; Kasozi et al., 2018). The restrictions on movements during the COVID-19 pandemic also aggravated loss of livelihoods among refugees who depend on informal livelihoods (Bukuluki et al., 2020). It is important to investigate destination substitution because this phenomenon will likely add to these already existing challenges affecting refugee response (Buscher, 2012; Monteith and Lwasa, 2017; Ahimbisibwe, 2019). However, the extent of destination substitution and how social networks of the refugees associated with changes in destination plans are less established in Kampala.

To some extent, refugees make preferences about certain destinations according to regulations regarding refugee admissions and socio-economic conditions of destination countries (McAuliffe and Jayasuriya, 2016). However, studies on urban refugees in Africa have shown that refugees' motivations change as they live their experiences of displacement where refugees imagine settling elsewhere other than the current city (Landau, 2006; 2021). Whereas socio-political factors may compel migrants and refugees to move to some cities in Africa, their mooring in such cities may owe to their inability to move onwards due to changes in management of migration flows (Fusari, 2018). Some cities may also be chosen as intermediate destinations when the ultimate destination is perceived to be more accessible through such intermediate cities (Shaffer et al., 2018). External and internal restrictions regarding refugee movements may result in refugees getting stuck or stranded in certain places (Snel et al., 2021). Currently, only 1% of the refugees can get resettlement to third countries through official channels (Hansen, 2018: 137). Because of the limited third-country resettlement opportunities, refugees who initially intended to relocate to more developed countries may end up getting stuck in intermediate cities (Jacobsen et al., 2014).

The classical approach to migration tends to dichotomize population movement in terms of origin and destination with a neglect of in-between destinations (Crawley and Hagen-Zanker, 2019; Crawley and Jones, 2021; Snel et al., 2021). In destination choices, scholars investigating refugees at the destination look at why refugees choose particular destinations (McAuliffe and Jayasuriya, 2016; Suzuki, 2020). On the other hand, scholars investigating prospective migrants from their origin inquire about the intentions to migrate to certain destinations (Bohra-Mishra and Massey, 2011; Sandu, 2017; Ikanda, 2018). Others who use macro-level spatial flows of refugees focus on ties and patterns of flows between two points of origin and destination (Suleimenova et al., 2017; Ruegger and Bohnet, 2018). These approaches may overlook the impacts of migration on intermediate destinations, particularly when migrants get stuck in certain places. This aspect is important for Kampala and other cities in the Global South where refugees conglomerate when attempting to make onward migrations. Refugees who, unintentionally, end up living in such cities might find further difficulties in integration since these cities are not chosen out of desire but because of prevailing circumstances.

For refugees, their decision to leave their home country is circumscribed by the persecution or armed conflict. However, where the conflict takes a gradual deterioration of conditions or flight occurs in stages, the refugee might have some limited aspirations about better destinations (Kunz, 1973). The ability to reach such destinations may depend on a range of factors, including the availability of financial resources, individuals' knowledge and skills, and availability of social capital (De Haas, 2021). Without disregarding other factors such as human and financial capital, the focus of this study is on social networks, which also constitute a source of social capital. Available family members, friends, or relatives at the destination are important because they can support the movement to the destination not only by providing emotional support but also providing information and financial resources to migrate. Migration studies have underlined the importance of social networks in channeling migrants to specific locations and thereby perpetuating migratory flows (Massey et al., 1993; Munshi, 2003; Haug, 2008; Zell and Skop, 2010). Increasingly, the need to extend factors such as social networks in the investigation of forced migration has also been recognized (FitzGerald and Arar, 2018: 810). Some studies have, for instance, shown that social networks can facilitate internal migration of resettled refugees from one city to another (Mossaad et al., 2020). The presence of kinship and friendship ties in cities also encourages and supports the relocation of refugees from camps to urban areas (Rhoden, 2019). Once in the urban areas, these social networks provide support for newly arrived refugees, particularly given the dearth of humanitarian assistance (WRC, 2011). Most of this social capital is linked to the ready availability of co-ethnic or co-nationals in the urban areas (Lyytinen and Kullenberg, 2013). Social ties elsewhere can also be instrumental in identifying alternative routes and transit destinations as the refugees' journey to their desired destinations (Shaffer et al., 2018). In the context of Uganda, it is therefore possible that social networks play a role in rerouting refugees to Kampala when access to destinations with the best options are constrained by immigration policies and fluctuating security conditions in refugee settlements. This study investigates the effects of social networks in destination substitution among refugees in Kampala.

The definition of a refugee in this study is based on the African Union's (former Organisation of African Unity (OAU)) Convention on Specific Aspects of Refugees in Africa, which includes victims of identity-based persecution and generalized violence (AU, 1969). "Urban refugee" here refers to a refugee whose habitual area of residence is a government-designated urban area, as opposed to a camp or settlement (Jacobsen, 2006: 274). De Haas et al.'s (2019: 907) concept of "spatial substitution effect" was used to frame the study. Spatial substitution occurs when migrants are redirected to some destinations with fewer restrictions about migrants of certain characteristics (Czaika and De Haas, 2017). The concept is used not so much in examining the relationships between regional and global restrictions and diversion of refugees, but the extent to which the current place of residence is not the initially targeted destination. Destination substitution is used here in two ways: the first is when refugees prefer to come to Kampala because they could not go to their primary desired destination. The second is when the refugees choose to come through Kampala instead of moving directly to their desired destination as a step to their primary destination.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Migration, refugees, and social networks at global level

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR, 2019), by the end of 2018, about 61% of the total refugee population lived in urban areas. Most of these urban refugees reside in the Global South on a protracted basis (Netto et al., 2022). Prolonged conflicts lead to refugees not returning to their home countries, resulting in onward migration to urban areas (IOM, 2019). Refugees sometimes prefer to settle in urban areas because of unstable security in camp areas (UNHCR, 2018). Cities are also the locus for reunification of families and friends, and for accessing remittances from abroad (Verghis and Balasundrum, 2019). Refugees are thus part of a broader processes of urbanization (Hoffstaedter, 2015). Refugees sometimes make preferences about a destination prior to moving to a destination (McAuliffe and Jayasuriya, 2016). In addition to financial resources and perceptions about places, one crucial factor that facilitates decisions about subsequent destinations are social networks (Mallett and Hagen-Zanker, 2018).

This study draws on the field of social networks and migration studies to explore how refugees moved to Kampala (Massey et al., 1993). Social networks refer to interpersonal ties of kinship, friendship, community, or organizational memberships that link migrants between their places of origin and destination (Boyd, 1989; Massey et al., 1993). Actors in the social networks, especially at the destination, act as sources of information and social support impacting on migration to a destination (Massey et al., 1993; Munshi, 2003). Information, knowledge, and social support provided by the actors in the social networks reduce the costs and risks of migration and settlement (Boyd, 1989; Awumbila et al., 2017). Additionally, migrants in the destination areas link non-migrants from places of origin through the "weak ties" to non-migrants and organizations (Granovetter, 1973). These latter actors in the social networks assist in matters pertaining to documentation and advocate for migrants in the destination areas (Keely, 2000; FitzGerald and Arar, 2018).

The role of social networks in explaining the patterns of refugee movement has been recognized in migration studies (FitzGerald and Arar, 2018). Najem and Faour (2018) show that refugees tend to disperse to various destinations along patterns of existing ethnic networks. Social networks ties of family, kinship, ethnic members, and friends link migrants to home, transit, and destination (Icduygu and Karadag, 2018). In addition to financial availability and perceptions about destinations, actors in the social network ties may influence when, where, and how to move (Mallett and Hager-Zanker, 2018; Najem and Faour, 2018). Refugees who migrated to cities and other destinations serve as nodes of social capital and information sources that perpetuate refugee movements to cities (Palmgren, 2014). The likelihood of a refugee living in a camp or city may also be influenced by the presence of family members or relatives in the camp or city (Rhoden, 2018). Social network ties in places of origin, transit and destination are important sources of social support and information about the prevailing policy context in the destination (Brekke and Brochmann, 2015; Fiedler, 2019). Further, weak ties in the social networks can be consolidated through social media that further support information transmission (Dekker and Engbersen, 2014). Information obtained from people met at different locations may aid the individual in discovering potential destinations (Bakewell and Jolivet, 2015). Information received from social networks can influence the decisions of refugees because of the trust established within the networks (Carlson et al., 2018; Dekker et al., 2018).

Migration, refugees, and social networks in Africa

In most African countries, the camps or settlements have been used to settle refugees to contain refugees in rural settings (Marfleet, 2007). Despite the camp system of refugee management, a significant number of refugees resided in urban areas long before the UNHCR's policy on refugee protection in urban areas (Jacobsen, 2006). Both micro and macro level factors pertaining to migrants in general and specifically to refugees contribute to flows to cities (Hopkins, 2015). Refugees' movement to cities has been associated with a search for better health care and other social services that are lacking in camps, employment opportunities, humanitarian assistance, and resettlement opportunities (Jacobsen, 2006; Muggah and Abdenur, 2018). More often, movements to urban areas are linked to the harsh socio-economic conditions and unstable security in the settlement and camp areas (Willems, 2005; Hopkins, 2015).

One critical factor that sustains refugees in urban areas are their social networks (Lyytinen and Kullenberg, 2013). The importance of social networks for refugees grew concomitantly with the urban socio-economic problems that refugees experience and the limited humanitarian support in urban areas (Jacobsen, 2006). Several studies show that refugees in urban areas of Africa rely on their social networks for their livelihoods (see, for example, Landau and Duponchel, 2011; Betts et al., 2018). In Cape Town, relatives and non-relatives were identified as major sources of financial support for business start-ups (Crush and McCordic, 2017). Similarly, in Nairobi fellow refugees are the main sources of social support and finance (Betts et al., 2018). Further, refugee flows in Africa are patterned on existing social networks of co-ethnics (Rüegger and Bohnet, 2018). Among the Somali refugees in South Africa, the narratives shared through migrant networks shaped the refugee's migration decision to South Africa (Shaffer et al., 2018). Similarly, through interactions with kinship networks in the diaspora, Somali refugees in Danghaly camp in Kenya idealize Minnesota (home of Somali-born American politician Ilhan Omar) and the desire to migrate there (Ikanda, 2018).

Migration, refugees, and social networks in Uganda

The settlement system, where refugees are allocated land to regain their livelihoods, is the de facto model Uganda employs for refugee management (Schiltz et al., 2019). Indeed, a limited period of residence in cities, specifically Kampala, is accepted, conditional on proof of self-sufficiency, as determined by Uganda's Refugee Act (Republic of Uganda, 2006). In addition, refugees in UNHCR caseloads for resettlement or special protection needs are permitted to reside in Kampala (Mulumba, 2010). Yet, for a variety of reasons, including those less related to self-sufficiency and special protection needs, refugees choose to settle in Kampala. Some studies have pointed to the lack of information on registration at borders, the need to search for gainful employment, and access to basic services that have contributed to refugee flows to urban areas (Bernstein and Okello, 2007). The lack of security in the settlement areas also account for the migration to Kampala (Mulumba, 2010). The settlement areas also have limited market opportunities, thus contributing to movement to urban areas where market opportunities are available. Over the years, there has been a sustained decline in land size in settlement areas, leading to migration to urban areas (Crawford and O'Callaghan, 2019). Although some of the refugees move to Kampala without specific intentions, a few others, especially those who have families, had specific plans to move to Kampala (Lyytinen, 2015). There are also cases of mixed motives where some individuals from conflict-affected countries move to Kampala to pursue career opportunities and to attain refugee status (Iazzolino and Mohamed, 2019). Despite the attraction to Kampala, a good number of refugees envision onward migration as the only permanent solution to their future (Den Boer, 2015). Hence, a few others move from elsewhere to Kampala with the aim of relocating, usually to developed countries (Iazzolino and Mohamed, 2019).

With the limited humanitarian and state assistance in urban areas, many of these refugees turn to their social networks to sustain themselves (WRC, 2011). Existing studies on urban refugees demonstrate how refugees use their social networks to access livelihood opportunities in urban areas - a pattern that is similar elsewhere in Africa (Clark, 2006; Mulumba, 2010; WRC, 2011) Mulumba (2010) found that the Eritreans, Ethiopians, and Somalis use their national-based networks as channels for receiving remittances from family members resettled in other countries. In a similar way, members of the Somali community - especially men - rely on ethnic networks to access employment opportunities and sell their goods to fellow Somalis (WRC, 2011; Buscher, 2012). Further, a few refugees also use their cross-border networks to run their businesses in selling animal products or to access cross-border employment opportunities (WRC, 2011). Although these studies reveal the importance of social networks, the focus on livelihood strategies falls short in explaining the role of social networks in influencing the decisions to move in Kampala.

A few studies in Uganda also explored the role of social networks in destination choices. Rwandan refugees in Uganda, for instance, were not willing to return due to the need to maintain the social ties established during exile (Karooma, 2014). Furthermore, one study among the Somali refugee community shows that the established ethnic ties in Uganda sustained onward movements to Kampala (Iazzolino and Mohamed, 2019). This study also shows that the Somalis use their social networks to connect through Kampala to other countries (Iazzolino and Mohamed, 2019).

The reviewed literature confirms that the refugees move to Kampala for various motives, including movement to a city with an intention of onward movement, and that social networks play a crucial role for movement and settlement in the city. However, none of these studies adequately discuss the relationships between social networks and destination changes. This study fills this gap by showing how having social ties at a destination may enable refugees to move to some alternative destinations. This study differs from a similar study by employing a cross-sectional survey of broader refugee communities (Iazzolino and Mohamed, 2019). Within regional and global discussions, the study contributes to the case of Uganda where refugees do not only have trajectories of movement to more developed countries but also to the settlement areas within Uganda.

METHODS OF THE STUDY

Study population and sampling strategy

The study is a cross-sectional survey conducted in Kampala, Uganda, between November 2020 and March 2021. The sample was drawn from the urban refugees who were 18 years and older. Respondents were drawn from the Somali, Congolese (DRC), Eritrean, Burundian, Ethiopian, South Sudanese, and Sudanese refugee communities. A nationality was included in the study if it had at least 1,000 refugees in Kampala as per 2020 refugee statistics. A sample of 500 participants was targeted using Cochrane's method of sample size determination. The study successfully interviewed a total of 479 refugees and asylum seekers.

The researchers employed non-probability sampling strategies due to the hidden or transient nature of the urban refugees (Singh and Clark, 2013; Bozdag and Twose, 2019). The researchers first inquired from refugee community leaders, local authorities, and organizations about the key locations of the selected refugee communities within the city. The researchers then identified places such as bistros, restaurants, internet cafés, shops, refugee centers, and meeting places where refugees congregate. The researchers then invited those who were willing to participate. From the gatherings, participants were then randomly selected using a ballot draw according to the required number. Where there were fewer people than the required number within a gathering, all the participants were interviewed. The participants were then asked where potential participants could be found, and that set up a chain referral process. To cater for some communities such as the Burundians and Congolese who did not have common meeting places, the snowball method was used, commencing usually with a seed.

Study variables and data analysis

Researchers used a pre-coded questionnaire to capture information about the refugees' demographic characteristics, patterns of migration, and social networks. To assess the extent of destination substitution, refugees were asked in the questionnaire whether the respondent had "planned to move to some other destination before coming to Kampala" from their last place of residence, with a "Yes" or "No" response. This question was used as an indicator for the dependent variable for the destination of interest, which is Kampala. Respondents were further asked about the descriptions of the places they had planned to travel to and the reasons why they did not go to the proposed place. They were also asked whether they moved to Kampala directly from their home countries or lived in camps, cities, towns, or rural areas elsewhere in Uganda or another country between leaving their home country and arrival in Kampala. Without disregarding the limitations, those who moved to Kampala directly from their home countries were included in the study because a few individuals might have moved to Kampala directly from their home areas, with the intention of onward migration. Hence, focusing only on cases of secondary movements from settlements or other proximate cities would exclude a few refugees in such category. The indicator used here was retrospectively measured by posing these questions to refugees who were already in Kampala. While this approach may have some limitations in measuring migration intentions, it was deemed a better approach to measure changes in the intention given the lack of longitudinal data that follow up refugee movements to Uganda.

Social networks are the independent variable of interest. The social network indicator was obtained by asking whether the respondent "knew someone who was either living in, or ever lived in Kampala at the time of migration to Kampala" ("Yes" or "No"). In addition, questions were asked about the number of ties at the destination, nature of relationship, frequency of communication, and support received from the actor. However, these latter variables are not included in the current study because they are outside the domain of the current study. The questionnaire also included questions about the demographic characteristics of the respondents at their previous place of residence. The questionnaire was pre-tested with 10 refugees selected from the different nationalities.

The study used descriptive statistics to present the profiles of the respondents from their previous places of origin, their desired destinations, and the reasons for not moving to the desired destinations. Researchers used a binary logistic regression to assess the effects of social networking on destination substitution. The results were interpreted in odds ratios; an odd ratio greater than one indicates a greater likelihood in destination substitution given a covariate. An odds ratio of less than one indicates a lesser likelihood in destination substitution given a covariate. An odds ratio of one indicates no significant effect of a covariate on substitution of destination. A P-value of 0.05 (or 0.5%) and 95% confidence interval were used to interpret the level of significance of the variables.

The study was conducted under the ethical standards provided by the Human Subject Research Ethics Committee (Non-medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand (H20/04/02), and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (SS519ES).

RESULTS

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the profiles of the refugees at their last place of residence before Kampala, indicating whether they had planned to settle elsewhere other than Kampala. For over half of the refugees, Kampala is more of a substitute destination than an initially intended final destination. There are also significant differences among these refugees in terms of their nationalities, occupations and the characteristics of the places from which they came to Kampala. In terms of demographic representations, slightly more adults (53.62%) had planned for some other destinations compared to children (42.55%) and youths (53.06%), as expected. However, the difference between adults and youths is marginal. There is also a marginal difference between male and female, although slightly more male respondents (54.07%) reported having planned to move to some other destination compared to female respondents (50.21%). Most of these refugees who had other destinations in mind apart from Kampala were mostly from Eritrea (63.38%), Somalia (63.25%), and South Sudan (61.7%). On the other hand, respondents from the Burundian and the Congolese refugee communities reported the least changes in destination plans as seen in 23.08% and 37.7% respectively.

Regarding the socio-economic backgrounds of the refugees, those who changed their destinations for Kampala were mainly single (53.76%) by the time they left their previous place of residence. Those who already had tertiary education by the time of arrival in Kampala also had higher representation among those who changed their previously planned destinations (58.5%). Similarly, 57.89% of respondents who came to Kampala as students or who were unemployed also changed their initially preferred destinations. This level is higher than all the other categories of occupational status. Further, 73.1% of the respondents who substituted the initially intended destinations lived in refugee camps or settlement areas before proceeding to Kampala. In contrast, only 44.8% of those who came from urban areas, and 35.94% of those who came from rural areas substituted their intended destinations with Kampala.

Figure 3 shows the characteristics of the intended destinations and the reasons for failing to move to such destinations. The sample focused only on those who had planned for alternative destinations. The finding indicates that the majority of refugees in the study reside in Kampala due to failure to reach cities outside Uganda. Over 85% of these refugees had planned to settle in cities or urban areas outside Uganda. Fewer than 10% had planned to settle somewhere else in Uganda before changing their decisions to settle in Kampala. The least-intended destinations were rural areas and camps outside Uganda, represented by 2% each for the two categories. Considering the reasons for moving to Kampala, as opposed to the desired destination, the lack of opportunities for resettlement to third countries was the leading reason (39.6%), followed by the lack of security in the desired destination (34%). Interestingly, only 3.6% of the respondents came to Kampala because of lack of socio-economic opportunities at their desired destinations.

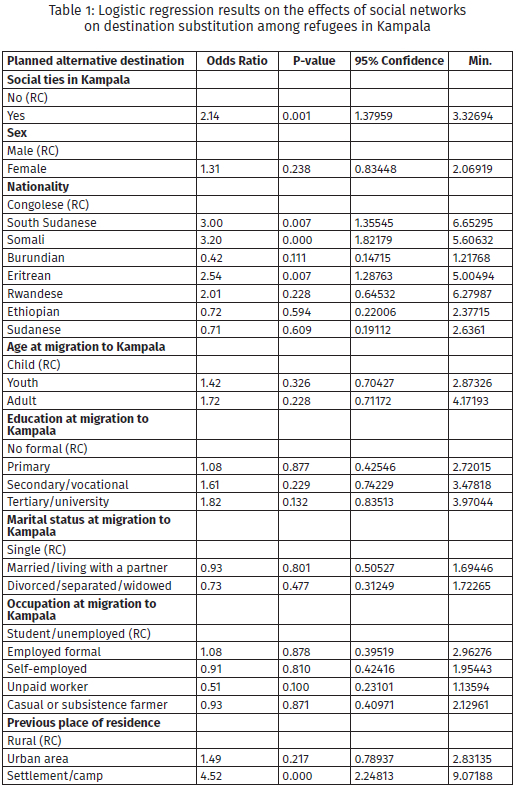

In the final analysis, the effects of social networks on destination substitution were modeled using a binary logistic regression, only reporting the results for the adjusted models. All the first categories in the independent variables were fitted as referent categories. The Likelihood Ratio is significant at Pr.< 0.05, indicating that the model is a good fit. However, the McFadden's Pseudo R2 for the model is 15% indicating that much of the variances in the model were not explained by the predictor variables. The results are shown in Table 1 below.

The social network variable in the model remained a significant predictor of destination substitution at Pr.< 0.05 even after controlling for all the other variables. Respondents with social connections in Kampala are more likely to substitute their desired destinations for Kampala (OR 2.14, Confidence Interval (CI): 1.37959 -3.32694).

Regarding the control variables, some nationalities and places of residence yielded significant results (Pr.<0.05), while occupation lost its significance in the adjusted model. Two of the nationalities with significant results were Horn of Africa countries, namely Somalia and Eritrea. The Somalis and Eritreans are 3.20 (CI: 1.82179 - 5.60632) and 2.54 (CI: 1.28763 - 5.00494) times more likely to substitute their destinations for Kampala respectively, when compared to Congolese refugees (the referent category). Apart from the two Horn of Africa countries, the South Sudanese, also with significant results (Pr. < 0.05), have 3.00 times (CI: 1.35545 -6.65295) more likelihood of substituting their intended destinations. Originating from camp or settlement areas, whether or not the camp or settlement is within Uganda, has positive effects on destination changes when compared to those who came from rural areas. Refugees who came to Kampala from settlement or camp areas are 4.52 times more likely to have substituted their preferred destinations for Kampala (CI: 2.24813 - 9.07188).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The objective of this study was to investigate the extent to which changes in destination plans have contributed to refugee flows to Kampala, and the influences of social networks in diversion of refugees to Kampala. This study is important, given that a significant number of refugees live in Kampala, yet access to social services, and social integration in the city have, hitherto, remained a challenge (Kasozi et al., 2018; Bukuluki et al., 2020). For instance, the recent restrictions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the loss of livelihoods of refugees (Bukuluki et al., 2020). Refugees often rely on informal livelihood activities for self-sufficiency (Monteith and Lwasa, 2017). Yet, the difficulties that refugees experience in Kampala are concomitant with the reduced resettlement options to more developed countries (Hansen, 2018). The reduced resettlement options and limited socio-economic opportunities in settlement areas imply that some refugees are likely to substitute Kampala for other destinations, adding to the already existing challenges that refugees experience in Kampala.

The key finding in this study is that social network factors facilitate the rechanneling of refugees to Kampala. Moreover, individuals who had knowledge of someone living in Kampala or who had ever lived in Kampala were more likely to move to the city after having considered going to alternative destinations. The finding thus agrees with previous empirical literature on social network-based patterns of refugee flows (Bertoli and Ruyssen, 2016; leduygu and Karadag, 2018; Ruegger and Bohnet, 2018). It further confirms that migrants move to specific locations because social capital, as a component of social networks, is location-specific (Massey et al., 1993). More importantly, knowledge of families, relatives, friends, or acquaintances residing in Kampala contributed to the alteration of the trajectories of the refugees, redirecting them to Kampala (Mallett and Hagen-Zanker, 2018). This is possible, given that refugees who had specific considerations about coming to Kampala, had some families, relatives, or friends prior to their movement to Kampala (Lyytinen, 2017). Individuals with knowledge of Kampala could have advised the refugees to move to Kampala either as an alternative to the desired destination, or as a transit route to access the desired destination. In addition, social networks have been important sources of social support for refugees in urban areas (Lyytinen and Kullenberg, 2013). Hence, the social support provided by the networks in the city compensated for the emotional and psychological stress of pursuing destinations with better socio-economic opportunities but were unattainable. In this sense, social networks play a vital role in the flow of refugees to cities in low-income countries that neighbor refugee-sending countries.

In addition to social networks, the Somali, Eritrean, and South Sudanese refugees are more likely to alter their destinations. Changes in destination among the Somali and the Eritrean refugee communities are not unique to refugees living in Kampala. One study using a threshold approach shows that Somali refugees seeking to resettle in the United States divert to South Africa, hoping the process of resettlement would be easier (Shaffer et al., 2018: 161). Similarly, Eritrean refugees in Milan and Rome did not intend to live in Italy but their objectives were affected by the regulations regarding migrant movements within the European Union (Brekke and Brochmann, 2015). The findings of this study add to the magnitude of this destination alteration previously explored in qualitative studies. The diversion of refugees toward Uganda, and then to Kampala is likely to be motivated by the relatively relaxed regulations regarding freedom of movement, livelihood activities, access to resources, and the perceptions that resettlement is easier once in Uganda compared to the neighboring countries (Crawford and O'Callaghan, 2019). However, as in the case of the Somalis in South Africa, substitution for Kampala does not necessarily entail ideal conditions or lasting solutions for the refugees (Shaffer et al., 2018). Difficulties regarding employment and access to resources persist once refugees live in the city, further driving the desire to be resettled, which often does not occur. The substituted destination once again becomes temporary and undesirable, perpetuating a dream for onward migration (Shaffer et al., 2018).

Furthermore, refugees originating from refugee settlement areas are more likely to engage in destination substitution than those originating from non-institutionalized refugee hosting areas. This result reflects resettlement to third countries as one of the main reasons why refugees leave camp areas and move to Kampala (Bernstein and Okello, 2007; Mulumba, 2010). The result also confirms the fact that refugees leave their countries without any specific destinations in mind (Lyytinen, 2017: 505). The idea about destination substitution evolves when refugees cross borders to camps and settlements in Uganda or in the neighboring countries due to security and socio-economic problems in these areas (Betts et al., 2020; Bagonza et al., 2021). The result is as expected, since cases of refugees who applied for resettlement are handled in Kampala (Bernstein and Okello, 2007). The bureaucracies surrounding resettlements, however, result in refugees getting stuck in urban areas, perpetuating a protracted refugee situation.

There are some limitations to this study. Firstly, this study is limited to urban refugees in Kampala. Refugee situations in other urban spaces in Uganda might be different. Kampala's context may also differ from that of other regional cities traversed by refugees. A comparative study of different cities might yield a more generalizable result. Secondly, owing to the nature of urban refugees as a "hidden population", the study employed non-probability sampling strategies. Therefore, the study may not be representative of the characteristics of the entire urban refugee population. Moreover, the small sample size implies that there might be some problems with precision of the sample in this study. Thirdly, participants were asked about their characteristics in previous places of residence when they were already in Kampala. This retrospective approach might result in recall biases and inaccuracy in measuring changes in migration intentions. Future studies can employ a longitudinal approach that follows refugees from their previous places of residence to their destination. Fourthly, there may be some ambiguities regarding the indicators. A "Yes" response to whether a refugee had planned for some alternative destination could imply that the initially preferred destination either is second to Kampala, in case of failure, or at the same level with Kampala. Lastly, the study is a cross-sectional study and therefore causal processes cannot be inferred. Future studies can build on those that can trace causal processes. Qualitative studies can also be used to better understand the mechanisms through which the social networks operate.

Regarding the study's contributions: it addresses a gap in discussions about destination intentions, and destination preferences among refugees in Uganda's context of a settlement system by highlighting the importance of investigating refugee flows to initially unintended destinations. Scholarship on refugees in African cities has shown how refugees sometimes reside in cities that were not intended as final destination. These cities are chosen either out of circumstances that circumscribe refugee movement, or as a strategy to reach some other destinations. This study adds to this body of literature by presenting the case of Kampala in a context where the focus has been on refugee settlements by showing how social networks may redirect refugees to, or through Kampala when refugees find it difficult to access their intended destinations. Moreover, the study provides useful data on refugee movements in countries of first asylum that can be utilized in designing programs for planning refugee assistance. In this sense, the concept of substitution effect was extended to the prevalence in destination changes.

In conclusion, with the protracted refugee situation and limited third-country resettlement options, refugees may be diverted to cities of low-income countries.

Connections through social networks would play a central role in this diversion through encouraging migration to the destination and providing alternative support systems. However, since these cities do not necessarily provide lasting solutions, exploration of further substitute destinations is likely to continue. In the meantime, a burden will also be shifted to these cities in low-income countries as well as social ties providing support in the interim time. The implication of destination substitution is that the protection of urban refugees that focuses on assisting refugees on special cases or the acceptance of refugees on the basis of self-reliance is likely to exclude those who reside in urban areas because of their inability to access their desired destinations -whether that desired destination is a settlement area in Uganda or abroad - thus perpetuating their vulnerabilities. Hence, it is important that the protection of refugees in urban areas should also focus on those who for some reasons cannot reach their intended destinations. Since the substitution of destination is associated with social networks, refugee families and communities could be appropriate channels to use to identify and assist refugees who diverted to Kampala. In addition, alternative pathways to resettlement - such as family reunification - should be expanded for those who cannot move. Lastly, this study opens the possibilities for more exhaustive study on the challenges associated with destination substitution, including long-term impacts of the destination substitution on refugees and host communities. Focusing on destination substitution will contribute to addressing challenges involved with refugee burden-sharing across different countries and locations within a country.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the financial assistance from the Society of Jesus, Eastern Africa province for the field work. The authors also acknowledge the technical support received from the Department of Demography and Population Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. .

REFERENCES

African Union (AU). 1969. OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. Ethiopia. Available at: https://bit.ly/auconvention. Accessed on 24 January 2022.

AGORA. 2018. Understanding the needs of urban refugees and host communities residing in vulnerable neighbourhoods of Kampala. Available at: https://bit.ly/3vvmZZn. Accessed on 24 October 2018.

Ahimbisibwe, F. 2019. Uganda and the refugee problem: Challenges and opportunities. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 13(5): 62-72. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajpsir2018.1101. [ Links ]

Awumbila, M., Teye, J. K. and Yaro, J. A. 2017. Social networks, migration trajectories and livelihood strategies of migrant domestic and construction workers in Accra, Ghana. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 52(7): 982-996. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909616634743. [ Links ]

Bagonza, P., Kyaligonza, T. and Bagonza, A. 2021. "Some refugees move because the health facilities in the settlement are not good": A qualitative study of factors influencing movement of Somali refugees from Nakivale settlement to Kampala City. Preprint. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-832372/v1

Bakewell, O. and Jolivet, D. 2015. Broadcast feedback as causal mechanisms for migration. Working Paper No. 113, International Migration Institute (IMI), University of Oxford. Available at: www.rsc.ox.ac.uk. Accessed on 07 March 2022.

Bernstein, J. and Okello, M. C. 2007. To be or not to be: Urban refugees in Kampala. Refuge, 24(1): 46-56. Available at: https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.21367. [ Links ]

Bertoli, S. and Ruyssen, I. 2016. Networks and migrants' intended destination. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10213. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/147899. Accessed on 28 February 2019.

Betts, A., Omata, N. and Sterck, O. 2018. Refugee economies in Kenya. Research Report, Refugee Studies Centre (RSC), University of Oxford. Available at: https://bit.ly/3zftf8z. Accessed on 21 July 2022.

Betts, A., Omata, N. and Sterck, O. 2020. Self-reliance and social networks: Explaining refugees' reluctance to relocate from Kakuma to Kalobeyei. Journal of Refugee Studies, 33(1): 62-85. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez084. [ Links ]

Bohra-Mishra, P. and Massey, D. S. 2011. Individual decisions to migrate during civil conflict. Demography, 48(2): 401-424. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0016-5. [ Links ]

Boyd, M. 1989. Family and personal networks in international migration: Recent developments and new agendas. International Migration Review, 23(3): 638-670. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2546433. [ Links ]

Bozdag, I. and Twose, A. 2019. Reaching hidden populations with an innovative two-stage sampling method: A case study from the refugee population in Turkey. Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping (VAM), World Food Programme (WFP). Available at: https://bit.ly/3JSM6tY. Accessed on 07 February 2020.

Brekke, J. P. and Brochmann, G. 2015. Stuck in transit: Secondary migration of asylum seekers in Europe, national differences, and the Dublin regulation. Journal of Refugee Studies, 28(2): 145-162. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feu028. [ Links ]

Bukuluki, P., Mwenyango, H., Katongole, S. P., Sidhva, D. and Palattiyil, G. 2020. The socio-economic and psychosocial impact of Covid-19 pandemic on urban refugees in Uganda. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1): 100045. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/ussaho.2020.100045. [ Links ]

Buscher, D. 2012. New approaches to urban refugee livelihood. Refuge, 28(2): 17-29. Available at: https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.36473. [ Links ]

Carlson, M., Jakli, L. and Linos K. 2018. Rumors and refugees: How government-created information vacuums undermine effective crisis management. International Studies Quarterly, 62(3): 671-685. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqy018. [ Links ]

Clark, C. 2006. Livelihood networks and decision-making among Congolese young people in formal and informal refugee contexts in Uganda. Households in Conflict Network (HiCN) Working Paper No. 13. Available at: https://hicn.org/working-paper/livelihood-networks-and-decision-making-among-congolese-young-people-in-formal-and-informal-refugee-contexts-in-uganda/. Accessed on 05 March 2015.

Crawford, N. and O'Callaghan, S. 2019. The comprehensive refugee response framework. Responsibility-sharing and self-reliance in East Africa. Humanitarian Policy Group Working Paper, HPG. Available at: http://cdn-odi-production.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/media/documents/12935.pdf.

Crawley, H. and Hagen-Zanker, J. 2019. Deciding where to go: Policies, people and perceptions shaping destination preferences. International Migration, 57(1): 20-35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12537. [ Links ]

Crawley, H. and Jones, K. 2021. Beyond here and there: (Re)conceptualising migrant journeys and the "in-between". Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(14): 3226-3242. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804190. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and McCordic, C. 2017. Comparing refugees and South Africans in the urban informal sector. African Human Mobility Review, 3(2): 820-853. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14426/ahmr.v3i2.827. [ Links ]

Czaika, M. and De Haas, H. 2017. The effect of visas on migration processes. International Migration Review, 51(4): 893-926. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.l2261. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2021. A theory of migration: The aspirations-capabilities framework. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1): 1-35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4. [ Links ]

De Haas, H., Czaika, M., Flahaux, M. L., Mahendra, E., Natter, K., Vezzoli, S. and Villares-Varela, M. 2019. International migration: Trends, determinants, and policy effects. Population and Development Review, 45(4): 885-922. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12291. [ Links ]

Dekker, R., and Engbersen, G. 2014. How social media transform migrant networks and facilitate migration. Global Networks, 14(4): 401-418. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12040. [ Links ]

Dekker, R., Engbersen, G., Klaver, J. and Vonk, H. 2018. Smart refugees: How Syrian asylum migrants use social media information in migration decision-making. Social Media + Society, 4(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118764439. [ Links ]

Den Boer, R. 2015. Liminal space in protracted exile: The meaning of place in Congolese refugees' narratives of home and belonging in Kampala. Journal of Refugee Studies, 28(4): 486-504. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feu047. [ Links ]

Fiedler, A. 2019. The gap between here and there: Communication and information processes in the migration context of Syrian and Iraqi refugees on their way to Germany. International Communication Gazette, 81(4): 327-345. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048518775001. [ Links ]

FitzGerald, D. S. and Arar, R. 2018. The sociology of refugee migration in the Arab world. Annual Review of Sociology, 11(6): 649-660. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041204. [ Links ]

Fusari, V. 2018. Libya: Hosting or transit country for migrants from the Horn of Africa? Afriche E Orienti, 20(3): 95-112. Available at: https://doi.org/10.23810/1345.FUSARI. [ Links ]

Granovetter, M. S. 1973. The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/225469. [ Links ]

Gusman, A. 2018. Stuck in Kampala. Cahiers d'études africaines, (231-232): 793-815. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.22554. [ Links ]

Hansen, R. 2018. The comprehensive refugee response framework: A commentary. Journal of Refugee Studies, 31(2): 131-151. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fey020. [ Links ]

Haug, S. 2008. Migration networks and migration decision-making. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(4): 585-605. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830801961605. [ Links ]

Hoffstaedter, G. 2015. Between a rock and a hard place: Urban refugees in a global context. In Koizumi, K. and Hoffstaedter, G. (eds). Urban refugees: Challenges in protection, service and policy. London: Routledge, pp. 1-10. [ Links ]

Hopkins, G. 2015. Casamance refugees in urban locations of the Gambia. In Koizumi, K. and Hoffstaedter, G. (eds). Urban refugees: Challenges in protection, service and policy. London: Routledge, pp. 42-75. [ Links ]

Iazzolino, G. and Mohamed, H. 2019. Shelter from the storm: Somali migrant networks in Uganda between international business and regional geopolitics. Journal of Eastern African Studies 133: 371-88. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2019.1575513. [ Links ]

Icduygu, A. and Karadag, S. 2018. Afghan migration through Turkey to Europe: Seeking refuge, forming diaspora, and becoming citizens. Turkish Studies, 19(3): 482-502. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2018.1454317. [ Links ]

Ikanda, F. N. 2018. Somali refugees in Kenya and social resilience: Resettlement imaginings and the longing for Minnesota. African Affairs, 117(469): 569-591. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/ady028. [ Links ]

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. World Migration Report, 2020. Available at: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr2020.pdf. Accessed on 20 August 2022.

Jacobsen, K. 2006. Refugees and asylum seekers in urban areas: A livelihoods perspective. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(3): 273-286. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fel017. [ Links ]

Jacobsen, K., Ayoub, M. and Johnson, A. 2014. Sudanese refugees in Cairo: Remittances and livelihoods. Journal of Refugee Studies, 27(1): 146-159. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fet029. [ Links ]

Karooma, C. 2014. Reluctant to return? The primacy of social networks in the repatriation of Rwandan refugees in Uganda. Working Paper No. 103. Oxford. Available at: https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/files/files-1/wp103-reluctant-to-return-2014.pdf. Accessed on 07 March 2019.

Kasozi, J., Kasozi, G. K., Mayega, R. W. and Orach, C. G. 2018. Access to health care by urban refugees and surrounding host population in Uganda. World Journal of Public Health, 3(2): 32-41. Available at: https://doi.org/10.11648/j.wjph.20180302.11. [ Links ]

Keely, C. B. 2000. Demography and international migration. In Brettell C. B. and Hollifield J.F. (eds). Migration theory. New York: Routledge, pp. 43-60. [ Links ]

Kunz, E. F. 1973. The refugee in flight: Kinetic models and forms of displacement. International Migration Review, 7(2): 125-146. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/019791837300700201. [ Links ]

Landau, L. B. 2006. Transplants and transients: Idioms of belonging and dislocation in inner-city Johannesburg. African Studies Review, 49(2): 125-145. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1353/arw.2006.0109. [ Links ]

Landau, L. B. 2021. Asynchronous mobilities: Hostility, hospitality, and possibilities of justice. Mobilities, 16(5): 656-669. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2021.1967092. [ Links ]

Landau, L. B. and Duponchel, M. 2011. Laws, policies, or social position? Capabilities and the determinants of effective protection in four African cities. Journal of Refugee Studies, 24(1): 1-22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feq049. [ Links ]

Lyytinen, E. 2015. Congolese refugees' "right to the city" and urban (in)security in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 9(4): 593-61. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2015.1116142. [ Links ]

Lyytinen, E. 2017. Refugees' "journeys of trust": Creating an analytical framework to examine refugees' exilic journeys with a focus on trust. Journal of Refugee Studies, 30(4): 489-510. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/few035. [ Links ]

Lyytinen, E. and Kullenberg, J. 2013. An Analytical Report on Urban Refugee Research. International Rescue Committee (IRC) and the Women's Refugee Commission (WRC) Roundtable Report and Literature Review. Available at: https://bit.ly/3povWR8. Accessed on 15 October 2014.

Mallett, R. and Hagen-Zanker, J. 2018. Forced migration trajectories: An analysis of journey- and decision-making among Eritrean and Syrian arrivals to Europe. Migration and Development, 7(3): 341-351. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2018.1459244. [ Links ]

Marfleet, P. 2007. "Forgotten," "hidden": Predicaments of the urban refugee. Refuge, 24(1): 36-45. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.21366. [ Links ]

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A. and Taylor, J. E. 1993. Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3): 431-466. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2938462. [ Links ]

McAuliffe, M. and Jayasuriya, D. 2016. Do asylum seekers and refugees choose destination countries? Evidence from large-scale surveys in Australia, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. International Migration, 54(4): 44-59. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12240. [ Links ]

Monteith, W. and Lwasa, S. 2017. The participation of urban displaced populations in (in)formal markets: Contrasting experiences in Kampala, Uganda. Environment and Urbanization, 29(2): 383-402. [ Links ]

Mossaad, N., Ferwerda, J., Lawrence, D., Weinstein, J. and Hainmueller, J. 2020. In search of opportunity and community: Internal migration of refugees in the United States. Science Advances, 6(32): 1-8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb0295. [ Links ]

Muggah, R. and Abdenur, A. E. 2018. Refugees and the city: The twenty-first-century front line. World Refugee Council Research Paper No. 2. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Q1570V. Accessed on 07 July 2020.

Mulumba, D. 2010. African refugees: Challenges and survival strategies of rural and urban integration in Uganda. Mawazo, 9(1): 220-234. Available at: https://www.africabib.org/rec.php?RID=Q00050745. [ Links ]

Munshi, K. 2003. Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the U.S. labor market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(2): 549-599. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25053914. [ Links ]

Najem, S. and Faour. G. 2018. Debye-Hückel theory for refugees' migration. EPJ Data Science, 7(1): 22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-018-0154-8. [ Links ]

Netto, G., Baillie, L., Georgiou, T., Wan Teng, L., Endut, N., Strani, K. and O'Rourke, B. 2022. Resilience, smartphone use and language among urban refugees in the Global South. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(3): 542-559. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1941818. [ Links ]

Palmgren, P. A. 2014. Irregular networks: Bangkok refugees in the city and region. Journal of Refugee Studies, 27(1): 21-41. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fet004 [ Links ]

Republic of Uganda. 2006. The Refugee Act 2006 (Uganda) Act 21, 24 May 2006. Available at: https://bit.ly/3Sccm7r. Accessed on 30 June 2015.

Rhoden, T. F. 2019. Beyond the refugee-migrant binary? Refugee camp residency along the Myanmar-Thailand border. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 20(1): 49-65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0595-8. [ Links ]

Rüegger, S. and Bohnet, H. 2018. The ethnicity of refugees (ER): A new dataset for understanding flight patterns. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 35(1): 65-88. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894215611865. [ Links ]

Sandu, D. 2017. Destination selection among Romanian migrants in times of crisis: An origin integrated approach. Romanian Journal of Population Studies, XI(2): 145-192. Available at: https://doi.org/10.24193/rjps.2017.2.07. [ Links ]

Schiltz, J., Derluyn, I., Vanderplasschen, W. and Vindevogel, S. 2019. Resilient and self-reliant life: South Sudanese refugees imagining futures in the Adjumani refugee setting, Uganda. Children and Society 33(1): 39-52. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12304. [ Links ]

Shaffer, M., Ferrato, G. and Jinnah, Z. 2018. Routes, locations, and social imaginary: A comparative study of the on-going production of geographies in Somali forced migration. African Geographical Review, 37(2): 159-171. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2017.1354308. [ Links ]

Singh, G. and Clark, B. D. 2013. Creating a frame: A spatial approach to random sampling of immigrant households in inner city Johannesburg. Journal of Refugee Studies, 26(1): 126-144. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fes031. [ Links ]

Snel, E., Bilgili, O. and Staring, R. 2021. Migration trajectories and transnational support within and beyond Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(14): 3209-3225. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804189. [ Links ]

Suleimenova, D., Bell, D. and Groen, D. 2017. A generalized simulation development approach for predicting refugee destinations. Scientific Reports, 7(1): 1-13. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13828-9. [ Links ]

Suzuki, T. 2020. Destination choice of asylum applicants in Europe from three conflict-affected countries. Migration and Development, 11(3): 1-13. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2020.1855738. [ Links ]

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). 2019. Statistical Abstract for Kampala City. Kampala. Available at: https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/0120202019_Statistical_Abstract-Final.pdf. Accessed on 14 September 2021.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2018. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2017. Available at: https://bit.ly/3S8zioa. Accessed on 06 September 2018.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2019. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2018. Available at: https://bit.ly/3JdDsHr. Accessed 12 February 2020.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. Uganda - Active Population 2020. Kampala.

Verghis, S. and Balasundrum, S. 2019. Urban refugees: The hidden population. In Allotey, P. and Reidpath, D. D. (eds.), The health of refugees: Public health perspectives from crisis to settlement. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Chapter 7. [ Links ]

Willems, R. 2005. Coping with displacement: Social networking among urban refugees in an East African context. In Ohta, I. and Gebre, Y. D. (eds.), Displacement risks in Africa: Refugees, resettlers and their host populations. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press, pp. 53-77. [ Links ]

Women's Refugee Commission (WRC). 2011. The living ain't easy: Urban refugees in Kampala. New York: WRC. Available at: https://bit.ly/3BYVycm. Accessed on 17 November 2014. [ Links ]

Zell, S. and Skop, E. 2010. Social networks and selectivity in Brazilian migration to Japan and the United States. Population, Space and Place, 17: 469-488. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.615. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Francis Anyanzu

1757378@students.wits.ac.za

Received 01 March 2022

Accepted 02 August 2022

Published 31 August 2022