Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.5 no.1 Cape Town Abr. 2019

ARTICLES

The Migration Processes in Ghana: The Case of Northern Migrants

Shamsu Deen-ZiblimI; Adadow YidanaII

IDepartment of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Science, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana. Email: zshamsu72@gmail.com

IIDepartment of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Science, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana. Email: adadowy@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

Over the past four decades, Accra has witnessed an increasing influx of young women who migrate to the city with the sole aim of carrying goods. This paper examines the migration processes of these young women, who mostly migrate from the northern part of Ghana to Accra, in the South. A sample of 216 female porters were selected for the study. A survey, personal interviews, and focus group discussions were the main tools for data collection. The reasons for their migration, the parties involved in the decision to migrate, and how their migration was financed were explored. The study revealed that the migration process of female porters is enabled by social networks; the women have varying levels of social capital, which facilitates movement and settlement. These social networks increase the social asset base of female porters and provide safety nets for them. It is found that the reasons for their migration are related to the declining importance of agriculture and the non-availability of jobs at their origin, which can be blamed on the liberalisation of the Ghanaian economy. It is also found that mothers are deeply involved in their daughters' migration decisions.

Keywords: Migration, processes, female porters, social network, Ghana.

Introduction

Migration is a common phenomenon in Ghana, with at least one internal or international migrant living in 43% of all households in 2005/2006 (Ackah and Medvedev, 2010). It is estimated that approximately 50% of the Ghanaian population is comprised of internal migrants (Awumbila, 2015). What this means is that half of the Ghanaian population migrated to settle in cities other than those in which they were born. The pattern of internal migration in Ghana has been one of continual movement of people from the less-developed North (which includes the Northern, Savannah, North East, Upper East, and Upper West Regions) to the well-developed South (Central, Western, Ashanti, and Greater Accra regions). This study focuses on the migration of people to the Greater Accra Region from the five regions that form the Northern part of Ghana. Internal migration has resulted from a spatial dichotomy of an underdeveloped North and a relatively developed South (Anarfi and Kwankye 2005; Kwankye, & Anarfi 2006). This spatial dichotomy is due to pre-colonial and post-colonial policies that made the North a labour reserve for the South (Saaka, 2002). The establishment of infrastructures in the South to the neglect of the North also increased this dichotomy (Stephen, 2006). However, the desire to travel is often times facilitated by the existing social networks that have been established.

Head porters are highly networked in both the source communities and the destination communities. In the networking process, head porters relate to one another from network positions that both constrain and facilitates their interactions, while the networks provide some stability to the broader social structure. According to Rahman and Lee (2005), social networks play a crucial role in reducing the risks of migration. The decision by the individual to migrate is largely influenced by existing social networks and kinship capital (Stark and Bloom, 1985), with the networks in the destination acting as a form of social insurance (Kuhn, 2003). A strong and viable network reduces the level of uncertainty in finding jobs and enables migrant head porters to secure work (in kiosks and storefronts) and accommodation prior to moving (Afsar, 2000; Rakib and Islam, 2009). Through this social network, migrants at the destination community affect the labour market outcomes of newly arriving migrants at these destinations, thereby reducing migration costs and consequently influencing the selection patterns of migrants ( McKenzie and Rapoport, 2012; Munshi, 2015). Other researchers, like Mishra (2007), have observed an interplay between migration and inequality in the source community, as the network in the destination community can reduce inequality through regular remittances to the country of origin.

According to Van der Geest (2011), female migration in Ghana is a common response to unfavourable cultural and social issues and is a survival strategy to cope with economic inequality. According to Action Aid (2012), female migration in Ghana is attributed to livelihood insecurity. Until recently, the North-South migration in Ghana used to be the preserve of men for economic and social reasons. However, this pattern has changed and today the dominant migration stream from North to South is of young women moving independently of their families towards the cities of Accra and Kumasi (Iddrisu, 2001; Litchfield and Weddington, 2003; Whitehead and Hashim, 2007; GSS, 2012). Due to the enormous benefits associated with remittances, families (mostly mothers) consciously support their daughters' migration by aiding their decision-making process and funding the migration (Awumbila, Owusu, and Teye, 2014; Awumbila, 1997).

The movement has brought about spatial imbalances in levels of development and has contributed to the North having the highest incidence of poverty (GSS/GHS, 2009). Consequently, the northern part of Ghana has been the major supplier of labour to the industries and the cocoa farms in the South, and this has contributed to high migration rates from the North to the large towns and the cocoa growing areas in the South.

For several years, there has been an increase in the number of unskilled and uneducated women, and young girls who have dropped out of school to migrate to the market centres in Southern Ghana. The high school dropout rates of the female porters is not as a result of parents' inability to pay school fees; rather it is largely due to cultural practices, such as early marriage and the desire of young girls to migrate to earn money to prepare themselves for marriage. These young women migrate to the South to engage exclusively in work as porters, carrying luggage on their heads for a negotiable fee. Any woman who engages in such trade is called a 'Kayayoo'. In the Hausa language, 'kaya' means 'load' or 'goods'. In the Ga language, the language of the indigenous people of Accra, 'yoo' means 'woman'. Therefore, 'Kayayoo' i refers to any woman or young girl who carries a load on her head for a fee. The plural form of 'yoo' is 'yei'; hence, 'Kayayei' are female head porters in the market centres in Ghana, especially in Accra and Kumasi.

Materials and Methods

This study draws on a wide range of data collection and analysis methods. According to Bryman (2008), the use of triangulation helps to capture different dimensions, that is, the choice of different methods provides this synergy in data capture. Therefore, the research employed the mixed method approach (qualitative and quantitative). The tools employed in the data collection included a survey, focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and individual interviews. About 216 respondents were selected from 4 locations in Accra. The areas selected for the survey were Agbogloshie, Tema Lorry Station, Mallam Attah Market and the Cocoa Marketing Board Market (CMB). These areas were purposively selected because they are noted to be the major areas in Accra where migrant female porters reside and work.

A convenient sampling technique was used to select the respondents. This was deemed appropriate as the porters are always moving, depending on where they are tasked to carry their loads. Because the concentration of porters in these four locations varied, the selection of respondents was made in proportion to the concentration.

Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews were employed to capture the wide range of experiences of the Kayayei, which are useful in complementing the data collected through the survey (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004). A questionnaire was used to elicit information for the quantitative arm of the study. Two analytical procedures were used that contribute to the mixed-method approach employed. The quantitative data analysis followed the conventional variable identification, entry, and manipulation using the SPSS software (Version 20), while the qualitative data analysis used manual coding procedures. First, the qualitative data were analysed using thematic and content analysis approaches. Second, the survey data were analysed by means of univariate, bivariate, and multivariate analytic techniques.

Results and Discussion

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

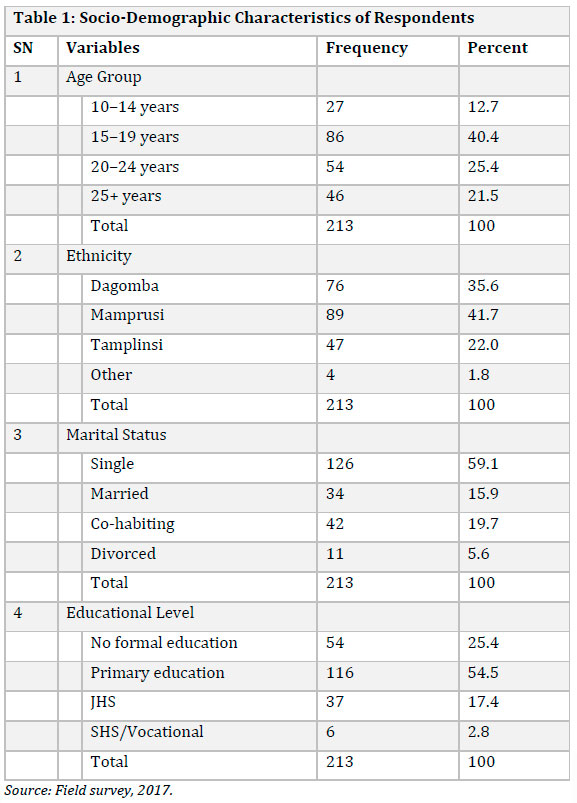

The study selected a total of 213 respondents from the 4 locations. From the results, the majority (44.4%) of the respondents were within the ages 15-19 years, 25.4% were within 20-24 years, and 21.5% were 25 years and over. This ties in well with the findings of Zaami (2010) and Baah-Ennumh et al. (2012), who claim that more teenage girls than matured women develop an interest in migration. In terms of ethnicity, 41.7% were Mamprusi, 35.6% were Dagombas, and 22% were Tamplinsi. Tmajority of the respondents were not married (59.1%), 15.9% were married, and 5.6% were divorced. In terms of the education levels of respondents, 54.5% of them had a primary level of education, 25.4% had no formal education, and only 2.8% had SHS/Vocational education (see Table 1). From the results, those with primary education all dropped out due to lack of interest, and those with junior and senior high levels of education left school due to failure.

The Migration Process and Experience

Until recently, analysis of the migration process as a whole has received very little attention (Schapendonk, 2012); rather, there has been a focus on migration in different areas, particularly relating to the causes and consequences of migration. The actual process, involving the reasons, the nature of movement, and the arrival and settling of the migrant, has been either viewed separately or ignored. This has led to suggestions that to obtain a nuanced understanding of people's migration, it is imperative to consider the entire process as a whole. These processes relate to push and pull factors from the source to the destination communities.

Reasons for Migration

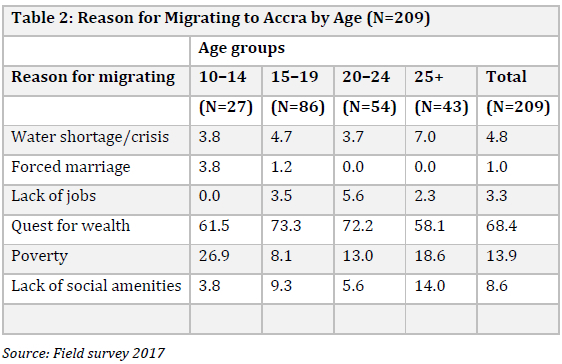

From the results, different reasons were provided to explain why the porters migrate. These include water crisis, forced marriage, lack of jobs, quest for wealth or 'looking for money', and high poverty rates in the North. A little over two-thirds of the female head porters (68.4%) reported that they travelled to Accra to look for money. Similarly, 13.9% of the respondents reported that they migrated to Accra due to poverty. About 4.8% reported water crisis in their places of origin as the reason for their migration. A small percentage (1.0%) attributed their migration to forced marriage, while about 3.3% mentioned lack of jobs at the source communities as the reason for the migration. Across all the age groups, the most significant reason for migration was to look for money or, relatedly, to escape from poverty. In all, 73.3% of the respondents aged 15-19 years migrated to look for money, while those aged 10-14 years had the highest percentage (27%) migrating as a result of poverty. Those who migrated as a result of forced marriage were in the 15-19 years and 20-24 years age groups. There was also a significant proportion of respondents in the age group of 25 years and above who migrated for other reasons, such as escaping conflicts, joining a partner, and family pressure at the place of origin (see Table 2).

Respondents provided different accounts to explain why they moved from the northern part of Ghana to Accra. Though they did not indicate this in the survey, it appears that some of them travel because of the perceived success of their colleagues returning to their origin communities.

My friends came from Accra the previousyear with a lot of things (assets) so I also wanted to go and see what I could get. I harvested groundnuts from people's farms and was given my share which amounted to four bags. So I borrowed money from a woman under the pretext of buying a nice cloth a friend had brought from Accra. We took a vehicle to the Tamale town from our village where we boarded a bigger bus to Accra (Abiba, 16-year-old Kayayoo).

Others gave account of how the journey was embarked upon and who was given prior notice of the impending trip.

I migrated to Accra from Zian in the Savelegu-Naton District. The very day I left the house, a friend I had already planned to travel with came to my house with the intention that we were going to the river to fetch water. I took some of my important things along with me. I did not inform my father, it was only my mother that I informed about my trip which she agreed to, but advised me not to inform my father. It was my mother who assisted me with transportation cost and some monies for my upkeep on the way. When we got to the river, I left my container there and joined my boy lover on a motor bike to Tamale to join a car to Accra fSalma, 20-year-old kayayoo).

As illustrated by the cases of Abiba and Salma, some women provide assistance to their daughters to migrate, since they share in the aspirations to migrate. Additionally, the case of Abiba shows that boyfriends of some girls provided their initial transport and other related travel costs. This is understandable as the items bought by these girls form the basis for subsequent marriage. Unless a female partner has accumulated basic 'feminine' assets, such as cooking utensils and cloths, a marriage cannot be consummated.

These findings support those of Abdulai (2010) who argued that mothers are the main propellers of their daughters' migration, while fathers often oppose the process. Additionally, the findings support those of Awumbila et al. (2014) who found that family relations tend to provide financial and moral support for rural migrants leaving for cities. Lack of social amenities that are important in sustainable livelihoods, especially water and good roads, are critical push factors associated with the porters' migration. This is because women and girls are responsible for fetching water and carting produce from the farm to the home and to the market. The poor roads and long distances to water sources increases the drudgery women suffer in their daily activities.

This finding resonates with the findings of Awumbila and Ardayfio-Schandorf (2008) that the reasons for migration from the rural North to the urban South include not only the limited economic opportunities but also the poor social amenities and cultural restrictions that partly account for female poverty. While socio-economic and cultural factors act as push factors for female migration from the North, relatively favourable factors act as pull factors in various destinations in the South. For example, Awumbila et al. (2014) argues that the pattern of internal migration in Ghana has also been influenced by the stark differences in the levels of poverty between the North and the South. Employment opportunities resulting from the growth of industries in urban areas like Accra have contributed to the rise in the movement of young people from the North to the South (Yaro, 2004; Van der Geest, 2011).

The Decision to Migrate

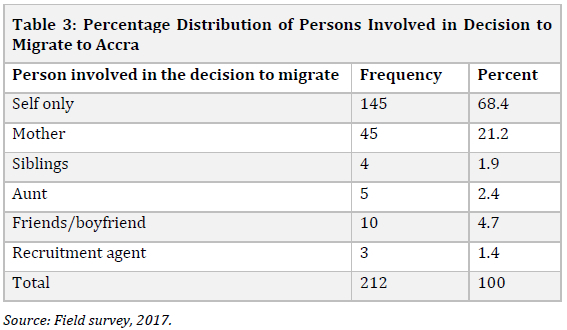

The percentage distribution of the main person involved in each female porter's decision to migrate to Accra is shown in Table 3. Most of the female porters (68.4%) made their independent decision to move to Accra. In addition, 21.2% were influenced by their mothers. Siblings (1.9%), aunts (2.4%), and friends/boy lovers (4.7%) also had some influence. The fewest number of porters (1.4%) listed recruiting agents as their main influence.

The decision-making process, however, is more complex than what the quantitative data depicts. The quantitative data only depicts the main sources of influence in the decision to migrate and does not convey how the interaction of various sources impact the decision. How is the role of other people or intermediaries in the decision to migrate played out? Focus group discussions suggest that aunts and sisters play substantial roles in the decision-making process.

Based on what I saw from those girls in our community who had come to Accra and returned home, I also wanted to come to Accra. So I talked to my mother and my father. My father strongly disagreed and it was a very difficult thing for me. It was my mother who agreed that I should go and even supported me with GH¢ 30 for transport. When I finally got here I had the phone call from my father that if I fail to return to the village within 3 days he will disown me and that I should look for my father. I had to get an elder in our village to talk to my father on my behalf and the first thing I did to make my father happy was to buy him a bicycle within my first month of working as a Kayayoo. In the third month I sent to him an amount of GH¢ 100 to enable him buy fertilizer for his farm. All these I was doing for him to forgive me and also to know that my being here is not to misbehave but rather to look for money to support the family and to prepare myself for marriage (Azara, 19 year-old Kayayoo).

As shown by the case of Azara, most fathers in rural Ghana are not in support of the migration of their daughters to the city to work as Kayayei. This finding resonates well with Abdulai (2010) who argues that the reasons why most fathers oppose the migration of their daughters to the city is that it tarnishes their image and reputation, especially when the girl is given out in marriage.

The Kayayei is good, but girls of today can do anything to disgrace the parents. I don't support it because I am a victim because my first daughter was given to a man to marry we collected the bride price and she requested to go to Accra to work and get money for the marriage. Hmm! After 4 months I was told that a different man in Accra has put my daughter in the family way. It was a big disappointment and disgrace to the entire family. Since then I do not encourage any girl in my house to go to Accra for Kayayei (Mba Alidu, an elder).

Another parent in Kasulyili in the Tolon District whose 17-year-old daughter had migrated to Accra explained:

If I had the means in providing her all what she need to prepare her to join her husband, or if I could send her to learn a profession or provide her with capital to do business, then she would not go. But because we can't provide her any of these, she has to go.

This quotation, similar to that of Salma presented earlier in this study, demonstrates the position of many in the focus group discussions: that most women provide assistance to their daughters to migrate as they share in their daughters' aspirations to migrate. The findings support those of Awumbila et al. (2014) who found that family relations tend to provide financial and moral support to rural migrants leaving for cities.

Other factors emerged from the in-depth interviews with parents in the porters' origin communities. These include the influence of peers, with peers acting not only as a major source of information about the destination areas, but also as persuasive agents who ask their colleagues to come along to see and enjoy the city life. According to some of the parents, when young girls see their peers returning home from cities with items like clothing, cooking utensils, and cell phones, they also yearn to go in order to acquire these items. During a focus group discussion, one parent whose daughter migrated without her knowledge corroborated this when he said:

Their peers go and come back with clothes and home utensils, so if they see these, they also feel the urge to migrate to Accra so that they can also come with those items. When the returned porters ask them to go with them to the city, they just jump high in sky and go along, they hide away usually in the morning or late in the evening when we thought they have gone to search for water at the river (Mba Salifu, a 51-year-old parent).

Recruiting Agents

Although the results of the data analysis show that recruiting agents play a smaller role in the decision to migrate, their influence seems to be on the rise. Focus groups and interviews with the female head porters in Accra showed that the experienced Kayayei who have established strong social networks with potential employers now act as job brokers to recruiting agents. These experienced female porters return to their home villages and surrounding villages to recruit more young girls to the city to work as porters, as is reported by this porter:

I was in my village when a woman from the nearby village who works in Accra came and told me that she wants to pick me to Accra to help her in her work. I agreed but when we got here I ended up working for her because I pay a commission of 10 cedis every day to her.

Besides the experienced Kayayei, family members and friends also recruit people from the origin communities, as a female porter explained:

One of the market women in Accra told me to bring someone I trusted, someone like me, to assist her in her work. So I quickly called my brother's daughter who had failed her JHS exams and was just sitting in the house doing nothing. She was happy and I sent her money to come the following week to help the woman in her shop" (Amina, 30-year-old Kayayoo).

The focus groups suggested that the form of recruitment depicted in the narration of Amina was becoming rather common. This is said to be facilitated by telephone communication, as the messages and discussions can be communicated more quickly by phone than by passing them through returnees. Recruitment in the migration industry is increasingly becoming an important factor in the migration of females worldwide. However, empirical works on this topic have been limited in the case of internal migration (Adepoju, 2010, 2004, 2002). Several emerging studies accounting for the processes that facilitate the international migration of women show that recruitment agencies, both formal and informal, are increasingly recruiting women, particularly from Asia, to work in the service industry in Europe.

Financing the Migration

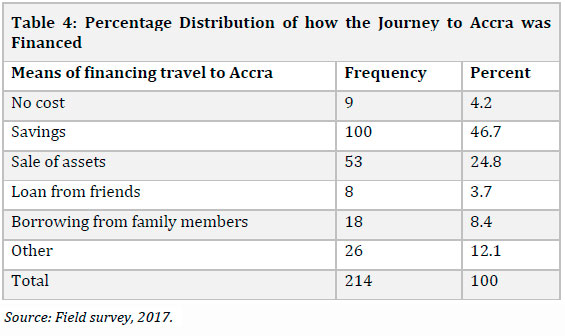

This section examines how the female porters' journeys to Accra were financed. Here, the study tried to analyse the various mechanisms the female porters adopted in financing their journeys to Accra. The percentage distribution of how their trips were financed is shown in Table 4. The highest percentage of (46.7%) said that they used their savings to make their journeys. In addition, about one-quarter (24.8%) of the respondents obtained money for their travel through sale of assets. Others reported that their journeys were funded through borrowing from family members (8.4%). Some migrants used other means (12.1%), while 4.2% said their travel did not involve any cost. Those who reported that their journey did not involve any cost were those who were assisted by recruiting agents. Lastly, those who took a loan (usually from a friend or relative) constituted the least proportion (3.7%).

Some migrants secure loans for their travel by presenting an asset to the lender as collateral. This, according to several focus group discussions, is a new way of sourcing loans. One of the respondents explained as follows:

I sold all my farm produce to enable me to finance my trip to Accra. The money I got was not enough so I had to give some of my cloths to a friend that enabled me to take some monies from her. I thank God because I had enough that I can pay and collect my cloths and I return to the North (Amama, 19-year-old Kayayoo).

The practice of offering collateral is said to have evolved as a result of the failure of migrants or returnees to honour their debts. This finding supports the argument by Stephen (2006) that the female porters use their assets at their origins as a collateral to obtain the funds necessary to travel to the city to work as head porters. There are various means of financing the trip to Accra.

My coming here was supported by an agent. She came to our village and requested the service of young girls she will send to Accra to assist her in her business. My aunty handed me over to her. She paid for my transportation. I cannot even say the amount she paid in transporting me here. Even when we were coming, she bought food for me and when we got to Accra she took a taxi cab that brought as to our present location. For this reason I did not pay anything in coming here (Amama, 17-year-old Kayayoo).

Amama was one of the respondents who reported that they did not spend any money of their own in travelling to Accra. These findings support those of Abdulai (2010) that most of the migrations of female porters are financed by agents who come to the rural areas, recruit young girls, and transport them to the South to work for them for a fee.

While some migrant female porters went directly to Accra from their villages, others had to stop temporarily in towns along the route before eventually arriving in Accra several months or years later, depending on the intervening circumstances. The places in which they stopped on their way to Accra included Tamale, Kintampo, Techiman, and Kumasi. Far less than one tenth (6.6%) of them stopped somewhere before arriving in their current place of residence in Accra, while the majority (93.4%) did not have any stop. Of those who migrated to Accra from another place rather than directly from their home village, the majority (64.2%) had intentions to eventually migrate to Accra, while a smaller proportion (35.7%) continued to Accra after their initial destinations were perceived to be unfavourable or less beneficial. Thus, 64.2% embarked on stepwise migration.

According to the focus group discussions and interviews, the main reasons for stepwise migration include the lack of capital to reach Accra, as depicted in Asana's situation narrated earlier, and the need to garner information from friends and relations about the location of other friends and relatives in Accra. Some of the migrants explained that they had to stop in places 'to look for money' that would enable them pay for their transport to Accra.

It is important to stay over for a few days so that they can teach you a few things about Accra before you enter that city. (A 16-year-old porter in Agbogloshie Market)

When asked whether learning about Accra was the reason for her stepwise migration, she answered in the affirmative. She further explained:

I was not the only one who stopped over for fear of just coming to Accra without knowing someone; this one sitting here also did the same.

A 30 year-old-woman and mother of two, Mariama, was the one referred to by the above respondent. Mariama echoed the story of the earlier respondent when she stated:

That place (Accra) is not home and most of these people living on the way to Accra has worked in Accra before and has tasted the life in Accra before, so they know what it is. They know people in Accra who could help you, they will also not letyou just go like that, some wantyou to stay and work with them, others want you to return home, but you want to go on the road and also to see things for yourself (Mariama, 30-year-old Kayayoo).

One could then say that the friends and relations who are located on the way to Accra enable the process of migration by acting as 'information brokers' and by offering migrants a place to stay, jobs, moral support, and advice. Thus, the need to earn enough money for the journey to Accra and the fear of migrating to Accra without the necessary networks is an important factor for stepwise migration among female porters. Stepwise migration enables female porter's access to important information and establishes networks at the destination, which helps in 'settling down'. Paul has already noted the relevance of stepwise migration. He noted that this was crucial for migrants as it enabled them to make enough money and find out enough about the advantages of the next destination. Stepwise migration could result from intervening obstacles or deliberate stop overs (Ravenstein, 1867; Paul, 2011).

The Journey to Accra

This section explains the strategies that young girls from the North adopted when preparing to migrate to Accra to work as Kayayei. The study revealed that some of the young girls leave their houses without saying goodbye to their parents or guardians. The following quotation illustrates some of the strategies they employed when planning to migrate to Accra.

Before coming here I made a stop in Tamale to work in a chop bar for 14 days, which enabled me to get money to transport myself to Accra. I would have wished to continue working in Tamale but the daily wage was very small [...] My people in the village always knew that I was in Accra but about a week after I arrived in Tamale I called my mother on phone and told her I was in Tamale. Although I didn't tell anybody I was going to Tamale or Accra they guessed that I had run away to Accra to look for money to buy nice things. I had planned to go to Accra but the money I took from my mother was not enough. I didn't even have time to count the money, I just run to the station and waited for a bus, but I realized that if my mum looked for the money and didn't see it she would immediately look for me, so I joined a tricycle and left to Walewale where I then boarded a big car. It was when I was going to pay the collector that I saw that the money couldn't take me to Accra [...]. What did I do? I could go back home of course, would you have? So I paid the bus collector to drop at Tamale and looked for work to get money to continue my trip to Accra (Asana, 21-year-old Kayayoo).

Two key issues are depicted in Salmas's and Asan's narrations: migration capital (financial capital and network capital), and the nature of the journey (i.e., whether it is made in one go or in a stepwise manner). This section has explored how potential female migrants finance and begin their journeys and arrive at their intended destinations.

Social Capital and Social Networks of Female Porters

Social network is a resource upon which migrant female porters rely. It entails a network of support and reciprocity that exists between individual porters within communities (Derham and Gzirishvili, 1998; Moser, 1998; Meikle et al., 2001). According to Carney (1998), such social support can be grouped into two categories: personal social resources and public good social capital. The public good social capital allows other resources to be utilised in a community. These include community-based organisations capable of negotiating on behalf of poor people. The personal resources, on the other hand, include personal loans, child-care support, and sharing of food, accommodation, and information. The value of the social networks of migrant female porters are demonstrated by their ability to migrate from their origins in the North to Accra. The study revealed that the female porters rely heavily on their personalised social networks in Accra.

In a focus group discussion with female porters in Mallam Atta Market in Accra, the porters mentioned that they always get information about Accra, the Kayayei work, and other economic activities in the city before making a decision to migrate. Such information was obtained from friends, family members, and young women in their villages that had already been to Accra and survived there as Kayayei (Beuachemin, 2000; Tanle, 2003). During the migration process, the women are usually escorted to Accra by friends, sisters, and other girls from their villages who have already been to Accra to work as porters.

In situations where an individual had to travel alone to Accra, word was sent out to friends and relatives or or other acquaintances of the woman to meet her at the bus station upon arrival. Communication technologies allow the travelling woman to call her host at intervals to provide updates on the progress of her travel.

Before coming to Accra, I had never been here before. So the day I was to leave I called Amina who is working here as a Kayayei on phone for her to assist me to come. She asked me to go to Tamale and ask of Imperial Bus Station. When I got to Tamale I went to the station and had my ticket ready for the journey to unknown Accra. Amina had already told me to arrive at the last stop. So when we got to Accra in the morning by 4am, my friend was there to receive me. She picked me to her sleeping place and there I saw about ten young girls from my village. Amina took me through the work for almost two weeks just to introduce me to the Kayayei work. The first day she gave me a head pan and led me to the market. Hmmm friendship is good (Damata, 17-year-old Kayayoo).

Reliance on social network goes beyond information-sharing to include care, financial assistance, and the sharing of food and tools for work between old and new arrivals in the Kayayei business. According to the migrant female porters, when one does not have money to travel to the city, one relies on friends in Accra to lend money which is repaid after the woman has arrived and worked for some days.

Before coming here I called my friend Amina who has been working here for four month to help me with transportation cost and also share information with me about my new destination. She agreed and sent down to me one hundred Ghana cedis (GHS 100) through mobile money transfer. She also told me which car to take and how to get to the station. She directed me to a young man in Tamale called Abukari who is a loading boy at the Tamale station who always assists new Kayayei to get to Accra. When I got to Tamale, Abukari handed me to the driver of the Benz bus and instructed him that my friend Amina would be at the station to receive me. With this assistance it was easy for me to find my way to Accra to join my friend for Kayayei business (Zalia, a 20-year-old Kayayoo).

The statement above was confirmed by a driver in Tamale who indicated the role drivers play in the migration processes of the female porters who often join their vehicles to Accra and Kumasi. He narrated the following:

Most of the young girls who migrate from the North to the South, especially Accra, do not know their way to their destination. What we do is that those who are there direct them to come to us at the station in Tamale. So when they come, their friends will call us on phone and plead with us to bring them to Accra. Because they are to depend on us till we hand them over to their friends in Accra, their lorry fare is different. We charge them additional ten Ghana cedis (GHS 10) because we have to make series of phone calls before we hand them over to their friends and also the risk involve in carrying them (Haruna, 38-year-old bus driver in Tamale).

The findings here support the argument by Awumbila (2010) that migrant female porters are usually aided by transport owners and drivers to get to Accra. They are assisted by their social networks of their friends from their home villages who are already working in Accra as porters and domestic workers.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Migration is seen by the female porters as a means to gain autonomy in their lives, a means of livelihood diversification, or as an alternative livelihood source. Migration has always been an alternative or additional source of livelihood for rural people, especially in times of crisis (Ellis, 2000; Ellis, 2003). The rapid urbanisation of Ghana, with Accra playing a primary role, accounts for its magnetic attraction. This finding is in line with those of several other researchers who argue that structural and economic reform policies have great effects on livelihoods, thereby contributing to rural-urban migration, especially of women to cities to work as head porters (Adepoju, 2010, 2004, 2002; Kwankye, Anarfi, Tagoe, & Castaldo, 2009). The migration process of female porters is enabled by their mothers and social networks, including boy lovers, friends, and family in the origin communities, along the way, and at the destination. The study recommends that the government, through the Northern Development Authority which seeks to bridge the gap between the North and the South, should make funds available for the young women in the North, so as to engage them in economic activities that will prevent them from migrating to the South to work as Kayayei. In particular, the policy of revamping the shea nut industry should target the young women.

References

Abdulai A. (2010). There is no place like home: the female porters in Ghana. Journal of Development Studies. 41(4) 48-72 [ Links ]

Ackah, C. and Medvedev, D. (2010). Internal migration in Ghana: Determinants and welfare impacts. The World Bank. From: <http://ideas.repec.org/p/wbk/wbrwps/5273.html> (Retrieved December 08, 2017.

Action Aid. (2012). Young urban women: Life choices and livelihood. From <https://bit.ly/2VkUixA> (RetrievedJune 13, 2017).

Adepoju, A. (2010). Migration in West Africa. Development, 46(3): 37-41. [ Links ]

Adepoju, A. (2004). Changing Configurations of Migrations in Africa. Migration Information Sources, 1 Sept.

Adepoju, A. (2002). Fostering Free Movement of Persons in West Africa: Achievements, Constraints, and Prospects for Intra-regional Migration. International Migration Quarterly Review, 40(2). [ Links ]

Afsar, R. (2000). Rural-Urban Migration in Bangladesh: Causes, Consequences and Challenges. University Press Limited: Dhaka.

Anarfi, J. and Kwankye, S. (2005). 'The Costs and Benefits of Children's Independent Migration from Northern to Southern Ghana'. Paper presented at the International Conference on Childhoods: Children and Youth in Emerging and Transforming Societies. Oslo, Norway, 29 June - July 3, 2005.

Awumbila, M, (2015). Women moving within borders: Gender and Internal Migration dynamics in Ghana; Ghana Journal of Geography, 7(2): 132-145 [ Links ]

Awumbila, M. (2010). Women Moving Within Borders: Gender and Internal Migration dynamics in Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography Vol. 7(2), 2015 pages 132-145 [ Links ]

Awumbila, M. (1997). 'Gender and structural adjustment in Ghana: A case study in Northeast Ghana'. In Awotoma, A. and Teymur, N. (eds.) Tradition, Location and Community: Place making and Development. Avebury Aldershot and Brookfield, USA, 161-172.

Awumbila, M., and Ardayfio-Schandorf, E. (2008). Gendered poverty, migration and livelihood strategies of female porters in Accra, Ghana. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 62(3): 171-179. [ Links ]

Awumbila M., Owusu, G., and Teye J.K., (2014) Can rural-urban migration into slums reduce poverty? Evidence from Ghana; Migrating out of poverty, poverty research program consortium, working paper 13.

Baah-Ennumh, T.Y., Amponsah, O., and Adoma, M.O. (2012). The living condition of female head porters in Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Journal of Social and Development Sciences, 3(7): 229-244. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. (2008). Introduction to Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Ellis, F. (2003). A Livelihoods Approach to Migration and Poverty Reduction, Paper Commissioned by the Department for International Development (DFID). Contract No: CNTR 03 4890 Date accessed: 15/6/17

Ellis, F. (2000). Rural livelihood diversification in developing countries. The case of the female migrant in Zanziba, Zambia. Date accessed: 15/6/17

GSS (2007). Patterns and Trends of Poverty in Ghana 1991-2006. Ghana Statistical Services: Legon.

GSS/GHS (2009) Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Accra, Ghana

GSS (2012). Population Census Report. Ghana Statistical Service: Accra.

Johnson, R.B. and Onwuegbuzie, A.J (2004) Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come; Educational Researcher; 33(70):14-26 [ Links ]

Kuhn, R. (2003). Identities in motion: Social exchange networks and rural-urban migration in Bangladesh. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 37(1-2): 311-337. [ Links ]

Kwankye, S. and Anarfi J. (2006). Migration from and to Ghana: A background paper. Country Background Paper C4. Migration DRC, University of Sussex, Brighton.

Kwankye, S., Anarfi, J., Tagoe, C. and Castaldo, A. (2009). Independent North-South Migration in Ghana: The Decision-making Process. Working paper T-29. Brighton: Sussex Centre for Migration Research. [ Links ]

McKenzie, D. and Rapoport, H. (2012). Self-selection patterns in Mexico-U.S. migration: The role of migration networks. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4): 811-821. [ Links ]

Mishra, P. (2007). Emigration and wages in source countries: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 82(1): 180-199. [ Links ]

Munshi, K. (2015). Community networks and migration. In: Bramoullé, J., Galeotti, A. & Rogers, B.W. (Eds.). Oxford Handbook on the Economics of Networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Paul, A.M. (2010). Stepwise International Migration: A multistage Migration Pattern for the Aspiring Migrant; American Journal of Sociology; 116(6): 184286. [ Links ]

Rahman, M.M. & Lee, L.K. (2005). Bangladeshi migrant workers in Singapore: The view from inside. Asia Pacific Population Journal, 20(1): 63-88. [ Links ]

Rakib A. & Islam, R. (2009). Effects of some selected socio-demographic variables on male migrants in Bangladesh. Current Research Journal of Economic Theory: 1(1): 10-14. [ Links ]

Ravenstein, E.G. (1867). The laws of migration- 1, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 48 (2), 167-235. [ Links ]

Saaka, Y. (2002) North-South Relations and the Colonial Enterprise in Ghana in Saaka,Y.(Ed.) Regionalism and public policy in Northern Ghana

Schapendonk, J. (2012). Turbulent Trajectories: Sub-Saharan African Migrants Heading North, Societies: 2, 27-41; doi: 10.3390/soc2020027.

Stark, O. and Bloom, D.E. (1985). The new economics of labour migration. The American Economic Review: 173-178.

Shepherd A, Gyimah-Boadi, E., Gariba, S., and Plagerson S. (2006), Bridging the north south divide in Ghana World Development Report, 4773831118673432908.

Stephen, J. (2006). 'Population Growth and Rural Urban Migration with Special Reference to Ghana'. International Labour Review 99: 481-85. [ Links ]

Stephen, C. (2006) Factors that make and unmake migration policies. International Migration Review; 38(3): 852-884. [ Links ]

Tanle, A. (2003). Rural-Urban Migration of Females from the Wa District to Kumasi and Accra: A case Study of the Kayayei Phenomenon. Thesis (Unpublished). University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast.

Teye, J. (2012). Benefits, challenges and dynamism of positionality associated with mixed method research in developing countries: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(4): 379-391. [ Links ]

Van der Geest, K. (2011). North-South migration in Ghana: What role for the environment. International Migration, 49(l): 69-94. [ Links ]

Whitehead, A., Hashim, I. & Iversen, V. (2007). Child Migration, Child Agency and Inter-generational Relations in Africa and South Asia. Working Paper Series, T24. Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty: University of Sussex.

Yaro, J. A. (2004). Combating Food Insecurity in Northern Ghana. Food Insecurity and Rural Livelihood Strategies in Kajelo, China and Korania. PhD thesis, Department of Sociology and Human Geography, University of Oslo. [ Links ]

Zaami, M. (2010). Gendered strategies among migrants from northern Ghana in Accra: A case study of Madina. Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of master of philosophy in resource human adaptations, University of Bergen, Bergen.