Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.4 no.2 Cape Town Ago. 2018

ARTICLES

Age Selectivity among Labour Migrants (Majoni Joni) From South-Eastern Zimbabwe to South Africa during a Prolonged Crisis

Dick Ranga

Faculty of Applied Social Sciences, Zimbabwe Open University. Email: rangadic@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

Focusing on unskilled Zimbabweans, this paper assesses the influence of the prolonged Zimbabwean crisis (2000-2016) on age differences in migration to South Africa. It is based on a questionnaire survey conducted among 166 households in 4 south-eastern districts in 2016/2017. Three-fifths of the households had migrant members in South Africa driven by the lack of jobs, poverty or food shortages at home. Labour migration to South Africa was male-dominated and involved younger people (below 30) than older people. Most of the migrants aged 30 or older moved during the peak of the crisis (2006-2010), most likely under the pressure of finding a means of survival for their families left behind. Young men who have a pre-crisis history in this migration predominated again after the crisis peak (after 2010). Most of this labour migration was clandestine and involved people with low levels of education. Hence, most of these migrants worked as 'general hands' earning ZAR 1,500 or less per month in South Africa. In this paper, it is argued that the Zimbabwean government should control such risky youth migration by creating jobs or income-generating projects in Zimbabwe and educating youth about unsafe migration.

Keywords: Selectivity, migration, youth, majoni-joni, Zimbabwean crisis.

Introduction

Recently, there has been a renewed interest in migration selectivity, that is, the tendency among migrants to "self-select according to specific characteristics" (Kanbur & Rapoport, 2003: 4). This is due to increased international migration resulting from globalisation. Some scholars have argued that in Africa women are increasingly involved in economic migration rather than merely accompanying their male partners (Adepoju, 2005). However, this paper argues that this change may not have dawned everywhere in Africa, even in West Africa, the region about which the author writes. For instance, the British Broadcasting Corporation News (BBC) (2015) documented the case of a small town in Burkina Faso where women formed the majority of the population because most men migrated to Italy for waged labour. Although the BBC News highlighted some economic benefits associated with this migration, it also noted that these unaware young girls are trapped into celibacy as their newly wedded husbands stay for prolonged periods in the diaspora and only visit home for short periods. This is because with the meagre salaries they earn on Italian farms they cannot afford airfares to frequently travel between Italy and Burkina Faso.

The plight of these young women is similar to that of their counterparts in southern Zimbabwe, where most young men migrate to South Africa in search of better wages or employment opportunities, leaving their wives in the 'custody' of their parents or other relatives (Manamere, 2014). Muzondidya (2008: 6) reported that it was in the late 1980s and 1990s that young single men from drought-prone southern Zimbabwe (Masvingo, Midlands and Matebeleland provinces) started migrating in search of "better-paying jobs in South Africa, Botswana and Namibia [...]". Known as injiva in the Matebeleland region and majoni joni in south-eastern Zimbabwe, these young men usually visit home during the Christmas holidays and are popular among young girls who regard them as better suitors than local men (Manamere, 2014). After marrying these girls and leaving them with their parents, these young men return to South Africa for prolonged periods.

Manamere (2014) cited other scholars who observe the tendency among young men from Chiredzi district in south-eastern Zimbabwe and neighbouring Mozambique to migrate in search of jobs in South Africa. For these young men, labour migration has become a 'rite of passage' into adulthood since it is often meant to raise money for lobola (payment made to one's in-laws), as best described by Manamere (2014: 92):

From the late nineteenth century, many young rural men in Southern Mozambique and Zimbabwe came to see their movement across the border as a necessary 'rite of passage', and step to marriage and social adulthood (Harries 1994; van Onselen 1980). As Native Commissioners observed in relation to Chiredzi's Shangaan labour migrants, for a male Shangaan youth to become a 'man' he must have "rubbed shoulders with workers in South Africa", braving the dangers of the journey and the hardships of migrant life in the township compounds.

The study informing this paper assessed whether the prolonged Zimbabwean crisis (2000-2016) led to any changes in labour migration from south-eastern Zimbabwe to South Africa, especially in terms of selectivity by age and other characteristics such as gender and marital status. Politically, the Zimbabwean crisis was characterised by corruption involving some members of the ruling party (ZANU-PF), unilateral decisions meant to strengthen the ruling party or benefit a few within the party, the use of violence during the 'fast track' land reform programme and towards elections and disputed election results. This led to hyperinflation of the local currency, a shortage of basic commodities, closure and relocation of many companies and increasing unemployment and poverty. All this led to a mass exodus of Zimbabweans by those from all walks of life in search of employment, particularly in neighbouring countries such as South Africa, Botswana, Mozambique and Zambia. South Africa was the major host of these migrants with an estimated 3-4 million Zimbabweans having relocated there.

According to Muzondidya (2008), the migration of Zimbabweans to South Africa that took place during the peak of the crisis in the 2000s was less selective as it involved both the young and old, married and single, southerners and northerners, skilled and unskilled. A combination of both the young and old could be discerned in some of the studies conducted among Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa during the peak of the crisis in the 2000s. For instance, Mosala (2008) found that most of the Zimbabwean migrants were between 21 and 40 years of age (Mosala, 2008). Studies conducted by Rutherford (2010) among Zimbabweans who worked on South African farms close to the Zimbabwe border found that most of them were married men who migrated because they were heads of their households and were responsible for caring for their families in Zimbabwe. These studies suggested the increased migration of Zimbabwean men who were older, married and motivated by the need to provide for their families affected by the crisis at home.

Studies conducted in the early 2010s, especially from traditional migrant sending districts in south-eastern Zimbabwe, are silent about the potential impact of the crisis in terms of increasing the migration of both the old and young. Instead, they continued to emphasize the migration of young men, which was also associated with challenges. For instance, the Zimbabwe Youth Council (ZYC) (2014: XI) reported that the migration of young men was associated with illegal migration to South Africa "upon completing grade seven (7) [...] in search of jobs in South Africa". This organisation reported that young women were also increasingly involved in illegal migration, with some of them being subjected to rape on transit to South Africa (ZYC, 2014). These young men and women would do jobs considered unappealing by many South Africans, such as domestic and farm work.

Elsewhere, Kanbur and Rapoport (2003) argue that on average immigrants are less skilled than natives of the United States (US). Nevertheless, these scholars refer to US statistics, which show that few immigrants migrated with no more than primary education. They found that migrants to the US tended to have better education than average persons in their home countries. This is relevant for Zimbabweans who have migrated to South Africa, since most of them have secondary education (Mosala, 2008).

Ray, Marlar and Esipova (2010) argue that everywhere in the world, young people are more likely than older people to express the intention to relocate to another country, irrespective of their current occupation. This suggests that older people are likely to migrate only when the pressure to do so is strong, such as in the case of an economic crisis. Even under such circumstances, migrants are unlikely to be older than non-migrants. In the case of Zimbabwe, studies have found that most of the Zimbabwean immigrants in South Africa were below 40 years of age (Tevera & Chikanda, 2009) or between 21 and 40 years (Mosala, 2008: 11), which are the peak years of work and family life.

Classical micro-economic theory of migration explains why both younger and older people migrate. It propounds that migration is performed by rational actors who, after a cost-benefit analysis, decide to migrate in expectation of a positive net return, which is usually monetary (Massey et al., 1993). Young men who migrate from Zimbabwe to South Africa often believe that there are better opportunities for employment or earning higher wages than those paid in Zimbabwe. This argument has become more relevant recently given the early deindustrialisation, which increased unemployment in Zimbabwe. In keeping with this argument, a village head interviewed by Manamere (2014) in rural Chiredzi suggested that young majoni-joni were 'forced' to migrate to South Africa by the economic situation in Zimbabwe.

In other cases, the migrant does not come up with this decision alone but a larger unit, such as the household, may be involved in making the decision to migrate, as argued in the household decision-making model or new economics of migration by Lucas and Stark (1985). This is usually meant to minimize risks to the household, such as imperfect markets, crop failures and unemployment. This is also a relevant explanation for the migration of young single men and adult married men from south-eastern Zimbabwe, a region that is largely drought prone. Furthermore, the lack of jobs due to early deindustrialisation in Zimbabwe was likely to make survival increasingly uncertain for households in this region.

The possibility of networking cannot be ruled out in this migration since some migrants were likely to connect with migrants who migrated earlier, including kin, friends and those with shared community origins (Massey et al., 1993). Having a family member abroad increases the chances that information might flow to those who had stayed behind, lessening the costs of migrating for other family members (Fischer et al., 1997). Achievements made by those who migrated earlier such as higher incomes, improved quality of life, ability to purchase land or improved agricultural productivity may also lure others into migration, as they may experience feelings deprivation relative to those who migrated.

The migration of young men from the sending communities in south-eastern Zimbabwe has been associated with several challenges. For instance, some of these young men are undocumented immigrants in South Africa, as they migrate clandestinely through informal routes. A headman interviewed by Manamere (2014: 96) in rural Chiredzi suggested that this was "[...] because they do not have the necessary travel documents so they 'jump' the border with the help of their friends". Although the ZYC (2014) suggested that young women are increasingly involved in clandestine migration, probably due to the crisis, the risks involved are likely to explain why more young men than women migrate to South Africa. In addition, young women risk being raped by their male accomplices along these informal routes to South Africa. Clandestine migration is also likely to account for age differences in migration to South Africa, since some older men are unlikely to take the risks involved or have worked and raised money to obtain the necessary travel documents.

Perhaps a challenge that is more related to age is that youth migration occurs "upon completing grade seven (7)" (ZYC, 2014: XI). Manamere (2014) argues that young men prefer crossing the border over completing their schooling. At the same time, their education helps shape "the type of work they have been able to secure in South Africa" (Manamere, 2014: 93). While young majoni joni drop out of school in search of jobs in South Africa, young girls also have high drop-out rates in these communities as they "enter into early marriages with these men whom they believe to be better off than unemployed young men at home" (Manamere, 2014: 94). Manamere (2014) discusses some of the challenges facing the young girls who get married to majoni joni in detail.

As previously mentioned, in many instances, majoni-joni enter into relationships with young girls and leave their new wives under the care of their parents, often returning home at very infrequent intervals. A range of problems have ensued from the subsequent misunderstandings and infidelity, including escalating divorce rates, an apparent rise in wife-battering as well as the spread of HIV-AIDS. Rural elders see young male border crossers as violent immoral criminals, people who break marriages, spread HIV/AIDS (returning having contracted the disease) and abandon their wives and children, creating diaspora orphans.

The fact that some young men enter South Africa clandestinely may exacerbate these challenges. Having 'jumped' the border, these young migrants are unlikely to visit home more frequently. South Africa has tried to reduce clandestine migration by formalising immigration through the issuing of work permits in the 2011 dispensation for Zimbabweans. Furthermore, most of these young men migrate at ages during which they are sexually active, which increases their risk of being trapped in the pleasures of the host country. According to Muzondidya (2008: 15), young migrants are less likely to remit home due to "the excitement of being away from home and the excitement of the 'bright lights' of egoli".

The objectives of this study are to (1) determine the ages at which the labour migrants left south-eastern Zimbabwe for South Africa during the crisis; (2) analyse age differences in the period during which the labour migrants left for South Africa during the crisis; (3) assess for association between age at migration and migrating clandestinely; (4) explore the contribution of other personal characteristics of the migrants to age differences in labour migration to South Africa and (5) investigate the role played by household and district-level factors in age differences in labour migration to South Africa.

Methodology

The study mainly adopted the quantitative research approach, whereby household heads, with assistance from other household members to crosscheck the accuracy of the information, responded to a household questionnaire. The sampling strategy involved the purposive selection of four districts in south-eastern Zimbabwe including Zaka, Bikita, Chipinge and Chimanimani districts. These districts have a tradition of labour migration to South Africa and, therefore, would best show any changes that occurred in age selectivity as a result of the crisis. Parts of them are also drought prone such that livelihoods based on rain-fed peasant agriculture cannot be sustained.

In each of the four selected districts, two Wards were purposively selected. This was meant to reduce travelling costs as those Wards in close proximity to each other were selected. Efforts were also made to include Wards in urban and rural areas. This is because the crisis was likely to influence labour migration to South Africa from both urban and rural setups.

Snowball sampling (also known as referral sampling) was used to select both households with labour migrants in South Africa and those without, for the sake of comparison. The researcher or assistant first identified an initial household with a migrant who once moved to South Africa for labour reasons. He or she was then referred to other households with similar migrant members. Although it is a non-probability sampling technique, snowball sampling allows the researcher to reach populations that are difficult to sample when using other sampling methods (Creswell, 2011). More so, the process is cheap, simple and cost-efficient.

While the desired number of households was 200, 50 from each of the 4 districts, the actual number enumerated was 166 households, indicating a response rate of 83%. This included 49 households from Bikita, 48 Zaka, 39 Chipinge and 30 from Chimanimani district. In one of the districts with the lowest response rates (Chipinge), some migrant households were reluctant to participate in the study, fearing that their members who were clandestine migrants in South Africa would be deported. Others mistook the research assistants for donors and were afraid they would not get aid if it was known that they had members in the diaspora.

Results and findings

Level of labour Migration from South-Eastern Zimbabwe to South Africa

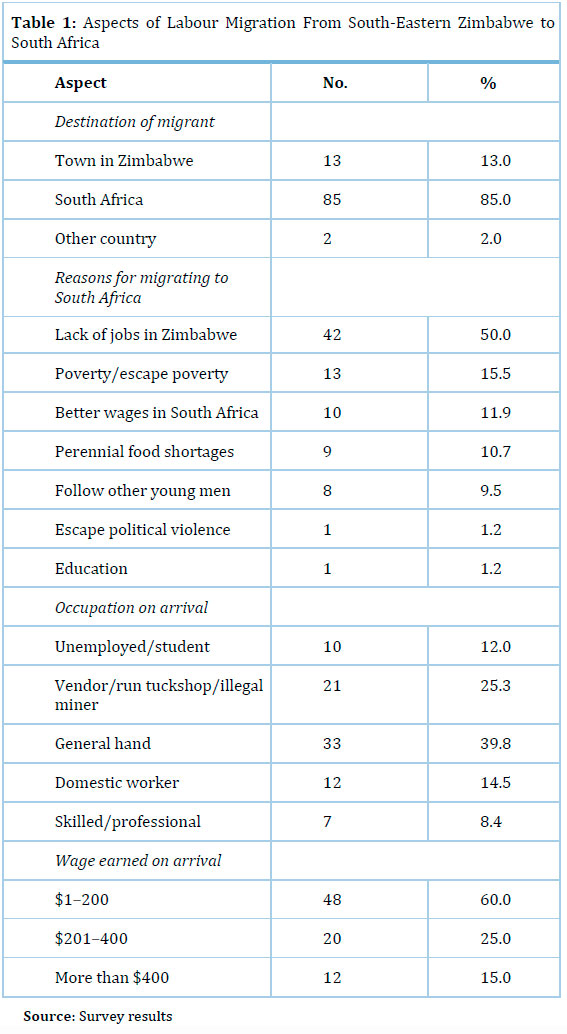

100 out of 166 (approximately 60%) of the studied households had at least one migrant member (result not shown). Among the migrant households, 87 out of 100 (87%) had international migrants. 85 of the international migrants were in South Africa, one was in another African country and yet another was overseas (Table 1). The remainder (13%) of the migrant households had internal migrants, most of whom migrated to cities or towns in Zimbabwe.

Most of the labour migrants from south-eastern Zimbabwe migrated to South Africa. This can be explained by the fact that this region is located close to the South African border and parts of this region are arid such that their rural economies "[...] cannot provide stable livelihoods based on small-scale rain-fed agriculture" (Manamere, 2014: 91). The prolonged crisis is likely to have worsened migrants' prospects of ever finding wage employment at home.

Consistently, half (42 out of 84) of the household heads confirmed that their members migrated to South Africa because of the lack of jobs in Zimbabwe (Table 1). Other reasons mentioned by relatively large proportions of the heads included poverty or need to escape poverty (15.5%), better wages in South Africa (11.9%), perennial food shortages (10.7%) and following other young men (9.5%) (Table 1). In other words, most of the members of these households were 'pushed' into migrating to South Africa by the lack of jobs in Zimbabwe and poverty, which was related to perennial food shortages given that some parts of this region are arid and cannot support livelihoods based on rain-fed agriculture. Those attracted to South Africa by better wages were fewer than those 'pushed' by the challenges at home. Only one was 'pushed' into migrating to South Africa by political violence and another by the need to conduct further education, which confirmed the predominance of economic over political reasons for migration.

Upon arrival in South Africa, nearly two-fifths of the migrant members were employed as general hands (Table 1). Some of these immigrants were employed on a temporary basis to do odd jobs, such as assistant mechanics, farm-workers, etc. Other studies have confirmed the presence of many unskilled and semi-skilled Zimbabweans who work on South African farms, especially in Limpopo province (Muzondidya, 2008; Manamere, 2014). In most cases, these immigrants are paid wages that are lower than the minimum wage, less than ZAR885 per month (Muzondidya, 2008).

This was followed by enterprising immigrants who operated as vendors, owners of Spaza shops (or tuckshops) and illegal miners, especially in the abandoned gold mines of the Gauteng province of South Africa. Although these activities helped them earn quick money, some of them were risky. For instance, South African newspapers have often reported stories of Zimbabweans who have lost their lives when the mines collapsed or were mugged by other illegal miners.

Three-fifths of the migrant members in South Africa earned incomes of up to USD200 (ZAR1,500) per month, which were small amounts. Other studies found that Zimbabwean migrant households in selected urban areas of South Africa earned ZAR1,433 per month on average (Crush & Tawodzera, 2016). According to these scholars, about half of them earned up to ZAR1,000, which was insufficient to meet many urban expenses. Nevertheless, this was better than being in Zimbabwe where there were no jobs.

Effects of the Crisis on Age Differences in Labour Migration to South Africa

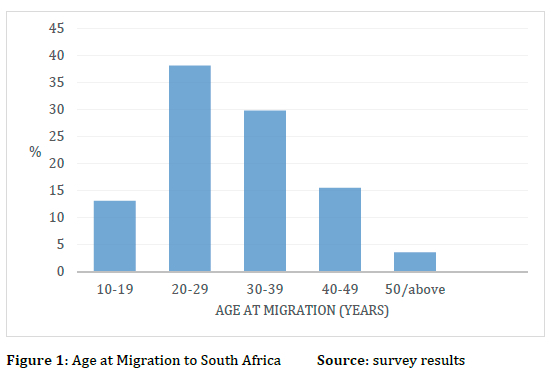

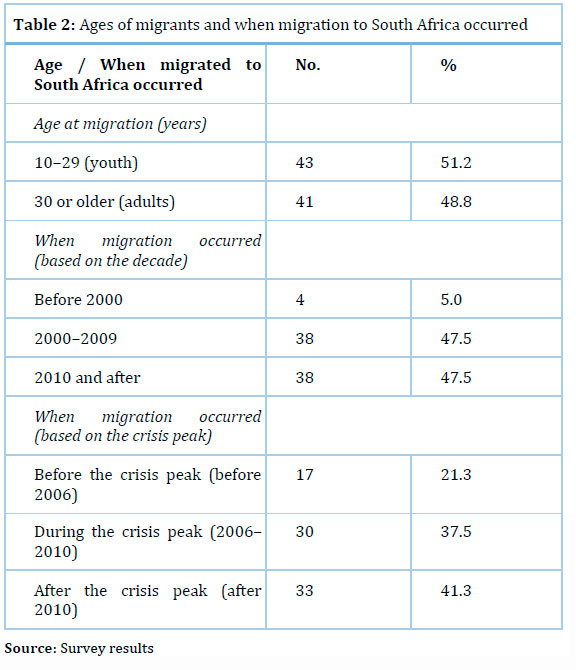

The study assessed for association between the ages of migrants and when they migrated to South Africa in order to analyse the effects of the crisis on age differences in labour migration to South Africa. Regarding the ages of the migrants, most of them (34 out of 84, or 38.1%) were young people in their twenties (20-29), followed by those aged 30-39 (29.8%). This indicated that most of the labour migrants from this region to South Africa were aged 20-39, their prime active ages (Figure 1). This confirmed other studies conducted in the host country, which found that most of the Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa were aged 21-40 years old and in the middle of their work and family life (Mosala, 2008). The crisis also contributed to the migration of people aged 40 years or over (15.5%) since they were also under pressure to provide for their families. Under normal circumstances such people are less likely to migrate than their younger counterparts. The remainder (13.1%) constituted members who migrated in their teens. This indicates a serious problem since most of them had barely completed secondary school at the time of migration.

The age variable was then reclassified in order to separate young migrants (below 30 years of age) from their older counterparts (aged 30 years or over). The proportions of younger and older migrants were almost equal (50.7% and 49.3%, respectively) (Table 1). Although this suggested that both the young and old were involved in this labour migration, results discussed so far have already indicated that these two age groups predominated in this migration at different stages of the crisis, with older men aged 30 or over more likely to have migrated during the peak of the crisis (2006-2010). Out of the forty-three young migrants, 44% were single and 56% were married (results not shown).

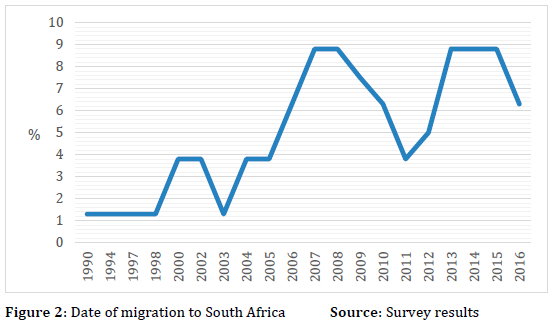

Regarding the period of migration, the study identified three major peaks during which most of the migration occurred (Figure 2). The first peak, though small, occurred at the dawn of the new millennium in 2000 and 2002, which was around the same time the crisis started. The second and more significant peak was associated with the peak of the crisis in 2007-2008. Like for the rest of the country, labour migration from this region to South Africa also reached its highest level during the crisis peak (2007-2008). In other words, most of the migrant members left the country between 2007 and 2008, obviously as a strategy to survive the crisis.

Thereafter, the level of labour migration to South Africa started to decline as a result of the stabilisation brought to the economy by the country's official adoption of multiple currencies dominated by the United States dollar (USD) in 2009. Foodstuffs returned to the shelves of Zimbabwean supermarkets after having been absent during the peak of the crisis. In the social sector, service delivery improved given the availability of foreign currency to import the necessary equipment and machinery. Most workers starting with civil servants were paid their salaries in foreign currencies. This positive change should have discouraged fresh emigrations and encourage return migration.

The third peak, which was unexpected and more difficult to explain, occurred between 2013 and 2015. During this period, the companies that had remained operational further retrenched workers in order to remain viable in the shrinking economy (Southern Eye, 2015). This further shattered whatever hopes citizens still had of finding employment locally. At the same time, the country, especially the south-eastern region, was severely affected by consecutive droughts associated with the El Nino effect (World Food Programme, 2016).

When the periods during which migration occurred were categorised according to the decade, the period 2000-2009 and 2010-2016 had the same proportions of migrants who left for South Africa (47.5% each). In other words, labour migration from this region to South Africa continued unabated from 2010 onwards (Table 2). The migration periods were then categorised based on the crisis peak including the period before the crisis peak (before 2006), the crisis peak (2006-2010) and after the peak (after 2010). Slightly more members migrated to South Africa after 2010 than during the peak of the crisis (41.9% compared with 37.6%) (Table 1). In other words, slightly more members of these households migrated to South Africa after the crisis peak (2006-2010) than during it, probably due to the factors already cited.

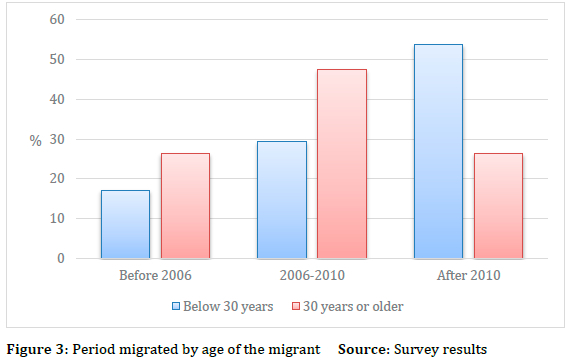

A test of association between the ages of the migrants and the period migrated revealed a significant result [Pearson Chi-square value 6.124, Asymptotic significance (2-sided) 0.047] (Figure 3). While the majority (53.7%) of young migrants aged below 30 relocated to South Africa after 2010, the largest proportion (47.4%) of older migrants aged 30 years or over migrated during the peak of the crisis (2006-2010). In other words, the crisis peak was more associated with the migration of older migrants aged 30 years or over than younger migrants aged below 30. This suggested that the migration of older married migrants increased during the crisis peak, signifying change from the previous dominance in this migration stream by young single men. This is because they were responsible for taking care of their families whose survival was at stake during the peak of the crisis. After the crisis peak, young men both married and single predominated in labour migration to South Africa. Muzondidya (2008) missed the point that older men were more likely to migrate to South Africa during the crisis peak as it was their responsibility to take care of families left ack home.

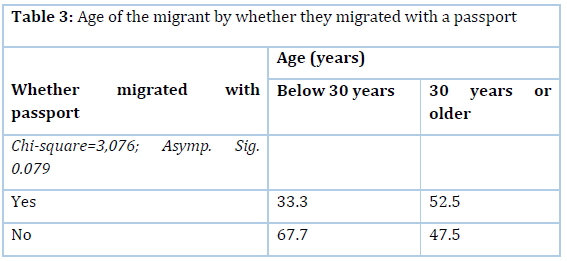

Age of the Migrant and Whether They Migrated Clandestinely

Young men have been associated with illegal migration to South Africa due to their inability to afford official documents such as Zimbabwean passports (Manamere, 2014). The study assessed for association between age at migration and migrating clandestinely. This would show which of the two age groups, younger and older people, was more desperate to leave the country during the crisis. More than half (48 out of 83, or 57.8%) of the migrants relocated to South Africa without passports (result not shown). Although there was no significant association between age at migration and whether migrants migrated without a passport, some patterns could be discerned in the distribution. Two-thirds (67.7%) of young migrants aged below 30 and half of those aged 30 years or older (52.5%) migrated to South Africa without official documents (Table 3). In other words, young migrants were slightly more likely to migrate to South Africa clandestinely than their older counterparts. This was probably because they were less positioned to have raised enough money to secure official travelling documents, especially Zimbabwean passports.

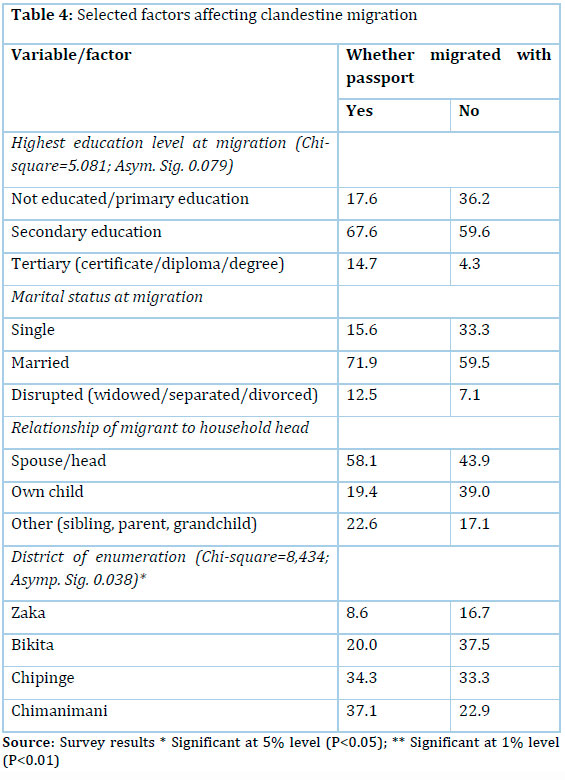

This confirmed other studies that found that young men from this region often migrate clandestinely to South Africa (ZYC, 2014; Manamere, 2014). For instance, Manamere (2014: 96) interviewed a headman in rural Chiredzi who said young men migrate from this area to South Africa clandestinely "[...] because they do not have the necessary travel documents, so they jump the border with the help of their friends". Results not displayed here revealed that the majority (29 out 48, or 60.4%) used informal routes through the forest, followed by those who were helped to cross the border by middlemen (35.4%) and those who bribed officials (4.2%). Crossing the border through forests is risky, which explains why it mainly involved men. Furthermore, clandestine migration was associated with the migrants' level of education; those having tertiary education (certificates, diplomas or degrees) were least likely to have migrated to South Africa without an official passport (Table 4). Although those migrants with primary or no education constituted the second majority among both the illegal and legal migrants, their proportion was higher among the illegal than the legal migrants. This suggested that clandestine migration was associated with low levels of education. This is probably because the educated are more likely to calculate the risks of migrating clandestinely than their uneducated counterparts. Besides increasing one's level of awareness of the dangers of clandestine migration, education also increases one's chances of being employed or having accessed enough money to secure the necessary travel documents before. This is different from someone who migrates soon after completing Grade 7. This also explains why clandestine migration involved children of the household head rather than the spouse or the male head of the household. This implies that the parents of some of the young men who migrated clandestinely could not afford or did not prioritise securing travelling documents for them; hence, the young men would connive with others to migrate clandestinely. Migrating clandestinely was also more associated with migrants from Bikita and Chipinge districts than those from Chimanimani and Zaka.

Further analysis of the issue of illegal migration revealed that the proportion of the migrant members who were legal immigrants in South Africa was higher at the time of the survey in 2016/2017 (71.8%) than at the time of migration (42.2%). This was probably due to the efforts made by the South African government to legalise this migration by issuing Zimbabweans with work permits during the 2011 Zimbabwean dispensation. However, some labour migrants remained in SA, working illegally, despite these efforts.

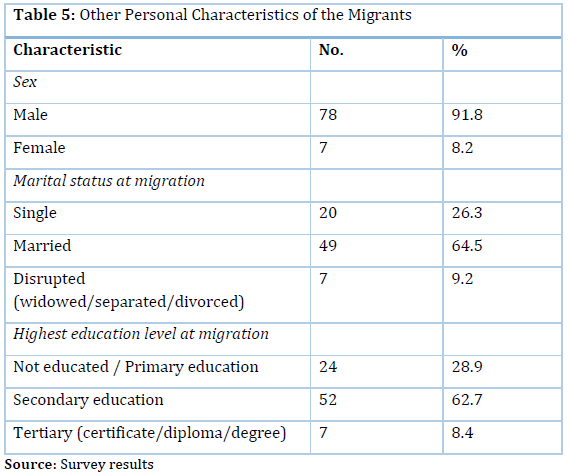

Contribution of Other Personal Characteristics to Age Differences in Labour Migration

An overwhelming majority (78 out of 85, or 91.8%) of the migrant members was male, which indicates that labour migration from south-eastern Zimbabwe to South Africa remains male dominated (Table 5). This means that there was no change in the gender composition of labour migrants from these districts in south-eastern Zimbabwe to South Africa. This was contrary to the study by the ZYC (2014) and others, which suggested increased feminisation of labour migration in Africa. Instead, the current study confirmed the tradition among males to migrate alone, leaving women and children behind. This confirmed the BBC's (2015) documentary on the 'city of women' in Burkina Faso where most young men migrate to Italy. This is likely to be associated with negative consequences for women who, besides being denied of their conjugal rights for prolonged periods, raise families alone.

The majority (49 out of 76, or 64.5%) of the migrants were married at the time of migration. Those who were single constituted slightly more than a quarter (26.3%) of the migrants. The rest (9.2%) had disrupted marriages (Table 5). This was similar to studies conducted among professionals, such as teachers (Ranga, 2015), where an overwhelming majority of the migrants were married men looking for means to help their families left back home to survive the crisis. The proportion (26.3%) of single men was, however, far higher among the current sample of unskilled Zimbabweans than that of teachers. This is because professionals go through many years of schooling and are required to have enough working experience before being recruited outside the country, unlike unskilled migrants, some of whom migrated after completing Grade 7.

The largest proportion (52 out of 83, or 62.7%) of the migrants had some secondary education (Table 5). This confirmed other studies that found that Zimbabwean immigrants in South Africa were more educated relative to nationals of other African countries (Mosala, 2008). This is because of Zimbabwe's emphasis on secondary education since independence in 1980. This was followed by those with primary or no education, who constituted more than a quarter (28.9%) of the migrants. Lastly, very few (7 out of 83, or 8.4%) had post-secondary or professional qualifications. This confirmed other studies which have argued that labour migrants leave for South Africa with low levels of education, such as after completing Grade 7 (ZYC, 2014). Although this involved only a quarter of the migrants, this explained why most of them worked as general hands earning low wages while in South Africa. Some of the migrants might not see the importance of completing secondary schooling given the low chances of finding employment at home in Zimbabwe.

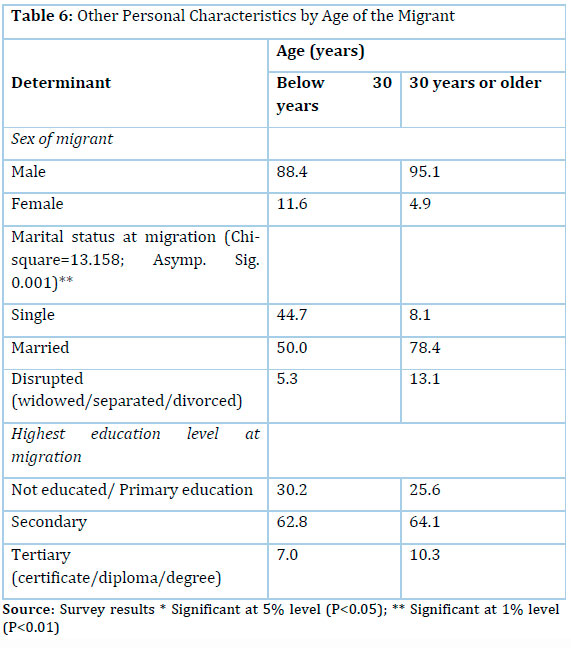

Age selectivity did not vary together with most of the other personal characteristics except marital status (Table 6). There was a highly significant association between age at migration and marital status. The majorities of both older migrants aged 30 or over and young migrants below 30 were married. But, the proportion for older migrants was significantly higher than that of their younger counterparts (78.3% and 50.0%, respectively) (Table 6). In other words, older migrants, most of whom migrated to South Africa during the peak of the crisis (2006-2010), were also married. On the other hand, young migrants aged below 30 included both married and single individuals. The peak of the crisis did not only increase the migration of older men, but also those who were married and sought a means of surviving the crisis for their families left back home.

The result for sex of the migrant was insignificant, probably because of the skewed distribution in favour of males. As for the insignificant result for education of the migrant, there was no difference between the ages as both the younger and older migrants were equally likely to migrate with low levels of education.

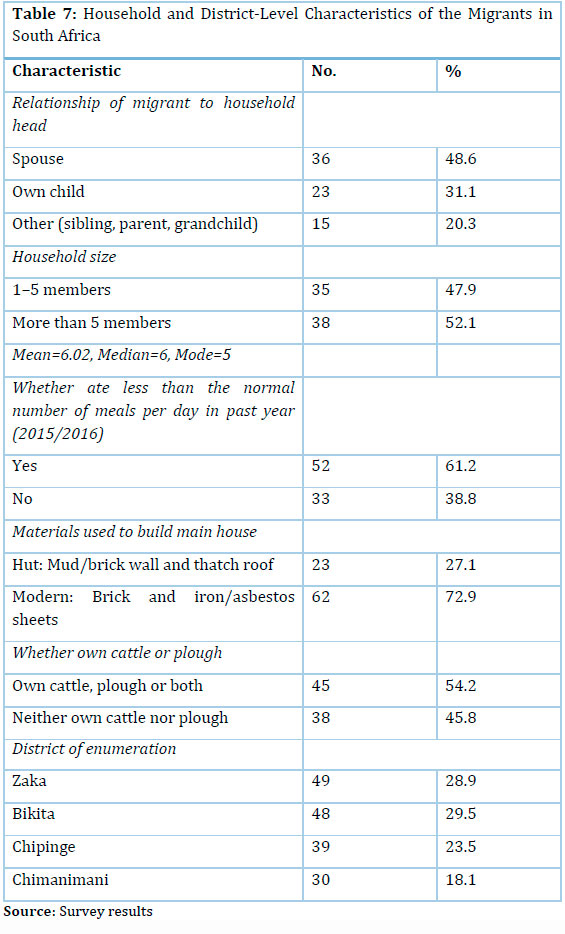

Effects of Household and District-Level Characteristics on Age Differences in Migration

Nearly half (48.6%) of the migrant members, the majority, were husbands of the female heads of households who participated in the study (Table 7). In other words, they were absent household heads. This supported the argument by Yabiku, Agadjanian and Sevoyan (2010) that in several Southern African countries, including Botswana, Lesotho, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, men use labour migration to South Africa as a way of coping with droughts and the cash economy since they cannot earn enough income at home given the lack of jobs. In this case, adult men from south-eastern Zimbabwe also used labour migration to South Africa as a way of coping with the Zimbabwean crisis. The second majority (31.1%) of the migrant members were children of the household head. As already found, this included both young men who were married and those who were single. The rest (20.3%) were siblings, parents or grandchildren of the household head.

Slightly more than half of the migrant members (52.1%) came from large households made up of six or more members. The average household size was six members. This was typical of rural areas in Zimbabwe where the total fertility rate (TFR) is six children per woman on average. Large households were likely to be poor and experience food shortages, making them likely to send one of their members into migration to South Africa. As found already, poverty and food shortages were the reasons for migration for the second and fourth largest proportions of the migrants in South Africa (Table 1). Southeastern Zimbabwe is vulnerable to droughts since most of it belongs to agro-ecological regions IV and V, which receive low rainfall of below 500mm per annum. This region was not spared during the drought that hit the country during the 2015/2016 farming season. For instance, The Standard (2016) reported that Chipinge district in south-eastern Zimbabwe was one of the most affected areas. Consistent with the effects of this drought, the majority (61.2%) of the households reported that they ate fewer meals than usual in the past year (Table 7). This should have contributed to the large proportions of members of these households that migrated to South Africa during 20132015.

Household socio-economic status was further assessed through the materials used to build the main house and ownership of cattle or a plough. The main houses of the majority (72.9%) of the households with migrants to South Africa were 'modern' as they were built of brick walls and iron or asbestos sheets (Table 7). The remainder (27.1%) of the households had a traditional hut as their main house. In other words, slightly more than a quarter of the households with labour migrants in South Africa were poor, as they lived in traditional huts. The proportion living in poverty increased when ownership of cattle or a plough was used as the criterion. 38 out of 83 (45.8%) of the households with labour migrants in South Africa neither possessed cattle nor a plough. Field notes revealed that for some of these households, especially those in Chipinge District, this was because they had just lost their cattle during the 2015/2016 drought.

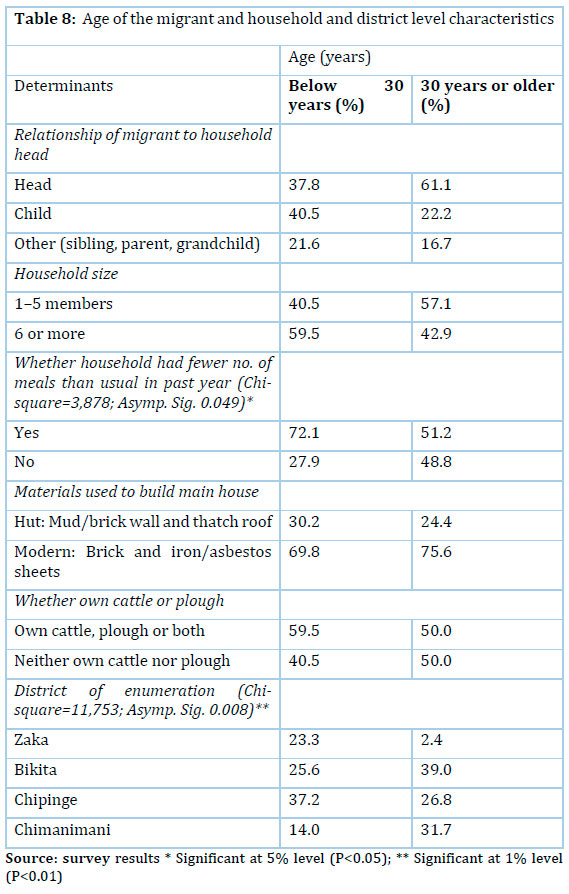

A significant result (P<0.05) indicted that the majority (72.1%) of young migrants aged below 30 and about half (51.4%) of older migrants aged 30 or over came from households that ate fewer meals than normal per day in the past year (Table 7). In other words, the households of young migrants were more associated with food insecurity during the 2015/2016 drought than their older counterparts. This probably explained why most of the young migrants migrated after 2010, especially during 2013-2015. This further confirmed the arguments made by The Standard (2016) that households in south-eastern Zimbabwe use the migration of young men to South Africa to cope with droughts.

This weekly newspaper reported that in Chipinge, one of the areas hardest hit by successive droughts in recent years, many families resorted to having one meal a day while thousands of livestock, particularly cattle, died due to lack of pastures and water (The Standard, 2016). It went on to argue that households in this district have coped with successive droughts through the migration of young men to South Africa and food relief from non-governmental organisations.

A highly significant result (P<0.01) indicated that the majority (37.2%) of young migrants aged below 30 came from Chipinge district, while the largest proportion (39.0%) of older migrants aged 30 or over came from Bikita district (Table 8). This further confirmed The Standard (2016), which argued that the migration of young men to South Africa, especially in Chipinge district, is a strategy used by their households to cope with successive droughts. On the other hand, Bikita district does not have a history of young men who migrate to South Africa but household heads in this district should have been 'pushed' by the crisis peak into looking for means of survival in South Africa given the lack of employment at home.

Although the result for household size was insignificant, the majority (59.5%) of young migrants aged below 30 came from large households with more than 5 members. In other words, the young migrants did not only come from households that were food insecure during the 2015/2016 drought but also large households, which further increased the risk of food insecurity. On the other hand, the largest proportion (57.1%) of older migrants aged 30 years or over came from smaller households (1-5 members), which suggested that they were the sole breadwinners of their young families. In the other insignificant results for materials used to build the main house and ownership of cattle or a plough, there were no differences among the classes. For instance, both young and older migrants were equally likely to come from households with a modern main house made of brick walls and a roof of iron sheets/asbestos/tiles and households that owned cattle or did not own cattle, a plough or both (Table 8).

Conclusion

There was a high level of labour migration from these districts in southeastern Zimbabwe to South Africa since about three-fifths of the households had at least a migrant in South Africa. The main reason for migration was the lack of jobs at home followed by poverty, better wages in South Africa, food shortages and the need to follow other men. Most of the migrants were men, aged 20-39, married and with some secondary education. However, about a quarter had primary or no education at all. This confirmed that labour migration from this region to South Africa remains a men's affair. This is probably because most of it, especially that involving young men, was clandestine. Once in South Africa, most of them worked as 'general hands' earning wages as low as USD200 (ZAR1,500) or less per month. This was mainly because most of them were not professionally qualified and some of them had primary or no education at all. Although generally low, these incomes were 'something' compared to the lack of jobs at home.

Almost equal proportions of the migrants left for South Africa during the crisis peak (2006-2010) and after 2010. Most of those who migrated during the crisis peak were older men aged 30 or over. The year 2010 was included in the crisis peak period since it still witnessed high numbers of fresh emigrations although they had declined after having reached a peak in 2007-2008. Hence, Muzondidya (2008) missed the point when he argued that both the young and old migrated during the crisis in the 2000s. Instead, the current study showed that older men who were also married heads of households were more likely than younger men to migrate to South Africa during the crisis peak, as it was their responsibility to take care of families left back home. As Muzondidya (2008) indicates, young men tend to easily forget their responsibility of remitting to the household of origin. In other words, the crisis in Zimbabwe 'pushed' adult men with family responsibilities into migrating to South Africa in search of survival for families left behind. This number was more than young single men, who predominated in migration from south-eastern Zimbabwe to South Africa before the crisis.

On the other hand, most of those who migrated after 2010, especially during 2013-2015 when the country was affected by consecutive droughts related to the El Nino effect, were young men below 30 years of age. Most of them came from households in the Chipinge district that ate fewer than their usual number of meals in the previous year (2015/2016). This suggested that the 2015/2016 drought contributed to their migration to South Africa. This further confirmed the arguments made in The Standard (2016) that households in Chipinge, an area most affected by the 2015/16 drought, use the migration of young men to South Africa as a way of coping with droughts. Finally, this indicated that labour migration from these districts returned to its pre-crisis trends of predominance by young men (Muzondidya, 2008) after 2010, having been dominated by older men during the crisis peak (20062010).

Based on these findings, the following recommendations are proposed:

1. The government of Zimbabwe and its development partners should create jobs or income-generating projects to benefit the youth in south-east Zimbabwe in order to control their migration to South Africa.

2. The government, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), local leaders, school teachers, parents and peers should educate the youth against migrating to South Africa before completing secondary or post-secondary education.

3. They should also educate the youth, especially those about to complete Grade 7, regarding the dangers of migrating clandestinely to South Africa, such as being apprehended and deported or being prey to wild animals when crossing the border through forests.

4. They should find diverse ways to help households in south-eastern Zimbabwe to cope with droughts and desist from using the migration of young men to South Africa as the main coping strategy.

5. There is need for further research to verify whether clandestine migration to South Africa is more associated with young migrants than older migrants and to compare traditional migrant sending districts with other Zimbabwean districts on the feminisation of labour migration to South Africa.

References

Adepoju, A. 2005. Migration in West Africa. A paper prepared for the Policy Analysis and Research Programme of the Global Commission on International Migration. From < https://bit.ly/2R7imhr > (Retrieved October 4, 2018).

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News. 2015. The Town of Women. BBC News, December 2, 2015. From <https://bbc.in/1MZBSDC> (Retrieved January 22, 2016).

Creswell, J.W. 2011. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Tawodzera, G. 2016. Migration and food security: Zimbabwean migrants in urban South Africa. AFSUN Food Security Series, 23. [ Links ]

Fischer, P.A., Martin, R. and Straubhaar, T. 1997. Should I stay or should I go? In: Hammer, T (Ed.). International Migration, Immobility and Development: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. London: Oxford International Publishers Ltd, pp. 49-89. [ Links ]

Kanbur, R. and Rapoport, H. 2003. Migration selectivity and the evolution of spatial inequality. Stanford Center for International Development (SCID), Stanford University. From <https://bit.ly/2R8r3bl> (Retrieved October 4, 2018).

Lucas, R. E. B. and Stark, O. 1985 Motivations to remit: evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy, 93 (5): 901-2 [ Links ]

Manamere, K.T. 2014. Majoni joni - Wayward criminals or a good catch? Labour migrancy, masculinity and marriage in rural south eastern Zimbabwe. African Diaspora 7: 89-113. [ Links ]

Massey, D.S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A. and Taylor, J.E. 1993. Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3): 431-466. [ Links ]

Mosala, G.S.M. 2008. The work experience of Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa. Issues Paper 33. Harare: ILO Sub-Regional Office for Southern Africa. [ Links ]

Muzondidya, J. 2008. Majoni joni: Survival strategies among Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa. Paper presented at the International Conference on the Political Economies of Displacement in Zimbabwe at Wits University, 9-11 June 2008. From <https://bit.ly/2EExMIB> (Retrieved March 7, 2018)

Ranga, D. 2015. Gender differences in the migration of Zimbabwean teachers to South Africa. East African Social Science Research Review, XXX1 (1): 43-61 [ Links ]

Ray, J., Marlar, J. and Esipova, N. 2010. Employed or not, many young people desire to migrate. From <https://bit.ly/2yXYXIv> (Retrieved December 15, 2014).

Rutherford, B. 2010. Zimbabwean farm workers in Limpopo Province, South Africa. In: McGregor, J. and Primorac, R (Eds.). Zimbabwe's New Diaspora: Displacement and Cultural Politics of Survival. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 59-76. [ Links ]

Southern Eye. 2015. Companies Retrench over 200,000 Workers. Southern Eye, 6 May 2015. From < https://bit.ly/2JbR07b> (Retrieved March 3, 2018).

Tevera, D. and Chikanda, A. 2009. Migrant remittances and household survival in Zimbabwe. Southern African Migration Project: Migration Policy Series, Cape Town: Idasa. [ Links ]

The Standard. 2016. Severe Drought Ravages Chipinge Villagers' Livestock.

The Standard, 17 January 2016. From <https://www.thestandard.co.zw/2016/01/17/severe-drought-ravages-chipinge-villagers-livestock/> (Retrieved July 20, 2017).

World Food Programme. 2016. El Nino: Faces of the drought in Zimbabwe. From <https://bit.ly/2PPGkxC> (Retrieved October 4, 2018).

Yabiku, S.T., Agadjanian,V. and Sevoyan, A. 2010. Husbands' labour migration and wives' autonomy. Population Studies 64(3): 293-306. [ Links ]

Zimbabwe Youth Council (ZYC). 2014. Harmful cultural and social practices affecting children: Our collective responsibility. From < https://uni.cf/2Ao83QB > (Retrieved July 25, 2017).