Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.4 no.2 Cape Town Ago. 2018

ARTICLES

African Migrants' Characteristics and Remittance Behaviour: Empirical Evidence from Cape Town in South Africa

Jonas Nzabamwita

PhD Candidate in Development Studies, Institute for Social Development, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. Email: nzabajonas@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

South Africa experienced an increase in the number of mixed categories of migrants from the African continent. Central to these migrants is the issue of their remittances. Using remittance motives in a prospect theoretical framing, this paper presents the findings of a study that explored remittance patterns and behaviour along a range of migrants' characteristics. The data are premised on questionnaires, interviews and focus groups with migrants from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Somalia and Zimbabwe who live in Cape Town, South Africa. The results show that economic migrants remit cash and goods more frequently, while forced migrants remit more both socially and in terms of the value of cash and goods. In addition, income, education and family size are significantly associated with remittance behaviour in respect to the amount of cash remitted as well as value of goods. Furthermore, there is a strong correlation between the type of remittance channels and income, education and immigration status.

Keywords: African migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, migration, remittances, South Africa.

Introduction

South Africa has witnessed the greatest recorded rate of increase in various categories of migrants from the African continent. The flow of these migrants into South Africa has always been intrinsically linked to several distinct periods. For instance, in the pre-colonial period, the discovery of diamonds in 1867 and gold in 1886 by the Apartheid regime lured low wage and low skilled labour migrants from Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Tanzania into South Africa's rich mining centres (Tsietsi, 1998; Adepoju, 2003b; Makhema, 2009; Dinbabo & Nyasulu, 2015). In addition to the use of inexpensive migrant labour in the mining industry, the South African go vernment recruited African migrants for domestic service, work on commercial farms and factories and the transportation and construction sectors (Crush et al., 2006; Kok et al., 2006). Towards the colonial period, foreign labour migration became not only keystone for government policies, but also pivotal for upholding South Africa's industrial revolution, which bolstered the economy and development, thereby attracting a massive influx of white migrants escaping political uncertainty and hostility in newly-independent African countries (Breyetenbach, 1979; Adepoju, 2000b; Peberdy, 2009).

For much of the colonial period, the Apartheid regime adopted protectionist and nationalistic migration policies with a particular emphasis on tight border control and restrictions on Africans who were considered undesirable (Segatti & Landau, 2011). When Apartheid was officially abolished in 1994, South Africa re-entered a global economic and political sphere, and the new government led by the African National Congress (ANC) felt obliged to repay a political debt to other countries for their role in the liberation struggle (Anderson, 2006; Crush et al., 2006). Subsequently, South Africa opened up its borders, which sparked a large-scale flow of refugees and asylum seekers running away from the deepening political crisis in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Somalia, Rwanda, Burundi, Angola, Nigeria, the Central African Republic (CAR), Ethiopia and others further afield (Adepojo, 2000b; Adepojo 2003b; Dinbabo & Carciotto, 2015). Likewise, the fall of Apartheid encouraged increased clandestine cross-border movement of economic migrants from as far as Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Cameroon, Uganda, Ghana, Senegal, Mali, Kenya, Algeria, Morocco and elsewhere in search of a better life and opportunities in South Africa (Mukasa, 2012).

By the end of the 20th century, restrictive immigration policies were still in place; however, the post-Apartheid government slowly dismantled border control policies (Kok et al., 2006; Segatti & Landau, 2011). The number of migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa in South Africa dramatically surged as a result of a booming economy coupled with amnesties to political refugees and asylum seekers (Crush, 2000; Crush et al., 2005). Along with the influx of short-term contract miners, long-term white migrants and migrants forced to flee persecution in their home countries, in 2000, South Africa recorded other categories of voluntary migrants that included skilled migrants (i.e. professionals, semi-professional, managerial and technical migrants), documented migrants (i.e. temporary residents in possession of tourism, study or medicine or those holding work permits) and undocumented or clandestine migrants (Wentzel et al., 2006; Wentzel & Tlabela, 2006).

While South Africa has a range of migrant categories, determining a precise figure of African migrants has proven to be extremely difficult. In addition, a number of sources have challenged the accuracy of data provided by the South African government (Stupart, 2016; Africa Check, 2017). Nonetheless, using the stream of contract and voluntary economic migrants, as well as forced refugees and asylum seekers, the 2011 Census placed the total number of international migrants in South Africa at 2,173,409. This was approximately 4.2% of the country's total population at that time, and 73.5% of these migrants originated from African countries (World Bank, 2018: 3). This figure is unlikely to include all illegal migrants, however, the projections from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2016) and International Labour Organization (ILO) (2017) show that the stock of migrants, particularly those from African countries, will continue to steadily and considerably rise, largely due to on-going protracted political instability and persistent economic collapse and deprivation.

The rising population of African migrants in South Africa brings to the fore the issue of remittances. In practice, remittances are a proportion of a migrant's income in his or her domiciled country that is sent to the country of origin (Van Doorn, 2002; Ratha et al., 2009). In the past, global financial institutions often confined remittances to financial transfers. However, this restriction underestimates and ignores the main essence of remittances, as the World Bank (2014) and Suliman, et al. (2014) estimate that a substantial share of overall remittance outflows to developing countries is in fact in-kind transfers. In a broader sense, beyond economic transfers of cash, migrants also buy consumable commodities that they send to their dependents in their home countries (Tavera & Chikanda, 2009; Chisasa, 2014). By the same token, international migrants establish social and political networks in their countries of residence through which they acquire a wealth of information, values, technology, intellectual capacity and social capital (knowledge, experience and expertise) as well as other tools that are transmitted to their respective countries in the form of social remittances (Levit, 1988; Goldring 2002; Goldring, 2004; Mohamoud & Fréchaut, 2006; Levitt & Lamba-Nieves, 2011). From this vantage point, migrants' remittances can potentially be defined as one part of a system of strong transnational connections that link people across distances and diverse cultural practices (Cohen & Rodriquez, 2005; Paerregaard, 2008). For that reason, cash, goods and social remittances are an essential and enduring linkage between migrant and home country at family and community levels, as well as local government and national levels (Taylor, 2000; Styan, 2007).

In relation to migrants' resource flows, remittances can further be classified either as formal or informal. The transfer of remittances is formal when sent using registered channels. Informal remittances, on the other hand, as the name suggests, are remittances sent through informal channels and, by definition, this type of remittance is not registered (Buencamino & Gurbonov, 2002; World Bank, 2012). In remittance markets, the transfers of cash primarily take place formally in the commercial banks, post offices, Money Transfer Operators (such as Western Union and MoneyGram), telecommunication companies, retails outlets and authorised dealers with limited authority (Orozco, 2006; Bester et al., 2010). They may also be transferred informally by the migrants when they visit the home country, or by family, friends, networks of transfer agencies, unregistered travel agencies, taxis, buses, call shops and ethnic stores (Truen et al., 2005; Truen & Chisadza, 2012; World Bank, 2014).

Remittances in the form of money or goods may be sent by migrants using a broad array of informal and formal channels, ranging from hand deliveries by migrants themselves or third parties to less regulated conduits of delivering goods (Truen et al., 2005; Truen & Chisadza, 2012; Chisasa, 2014). Social remittances, on the other hand, are intangible assets. As such, the potential pathways along which they are transmitted are cross-linking modalities such as letters, telephone calls, emails, online chats, videos, face-to-face conversations and meetings with key political figures from migrants' homelands (Levitt, 1998; Levitt & Joworsky, 2007).

Different types of remittances and varieties of channels have made it extremely difficult to establish the total size of the remittance market. Similarly, ensuring that all remittance outflows are accurately and consistently reported has always been challenging in South Africa. Given this complexity, being the largest economy of the region and the only middle-income country in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa is among the continent's largest remittance markets (Bakewell, 2011: 35). The remittance outflows account for about 0.4% of South Africa's total Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and the approximate size of the total remittance market from South Africa to other African countries is $2 billion per annum (Technoserve, 2015: 4).

While migrant remittances from South Africa to other African countries continue to grow, and despite a plethora of literature, there has been a knowledge gap as to how and in what respect remittances might differ among migrants. The continued deficiency in the understanding of the fundamental aspects of remittances requires answering questions such as: Who remits? What is remitted? How much is remitted? Why and how? As a contribution to these academic debates, this paper sets out to explore the link between African migrants' characteristics and remittance behaviour. The next section of this paper presents the theoretical literature. Section 3 presents the methodology and a summary of the main variables used in the analysis. Section 4 presents and discusses empirical findings and the last section presents a conclusion.

Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

A substantial number of theories have been advanced to analyse what motivates a rational migrant to send remittances (e.g. Lucas & Stark, 1985; Stark & Lucas, 1988; Poirine, 1997). Since the decision to remit funds and other resources is underpinned in the behavioural approach, a combination of remittance motives and prospect theory would provide better insights into remittance behaviours. The original prospect theory was developed by Kahnerman and Tversky (1979) and was later revised and improved by other authors (i.e., Kahnerman & Tversky, 1991; Tversky & Kahnerman, 1992; Wakker & Tversky, 1993; Kahnerman & Tversky, 2000; Wakker & Zank, 2002) to explain the decision-making process. This descriptive theory departs from the normal utility approach to include the psychological and economic principle of decision making under conditions of risk, uncertainty and ambiguity (Wakker & Zank, 2002). Using the utility approach, Opong (2012) and Barberis (2013) argue that when faced with decisions, the behavioural patterns of all decision makers will seek to maximize their utility, by first weighing each possible outcome with the probability of occurrence and summing this up over all possible outcomes, and then selecting the strategy that guarantees the highest possible returns or payoffs.

In a prospect theoretical perspective, individual decisions are anchored around a reference point and a decision maker evaluates the outcomes in terms of loss and gains relative to the selection of choices. What influence a decision maker the most and thereby act as carriers of value or utility are circumstances, rather than the final asset position that includes current wealth (Kahnerman & Tversky, 1991; Carmerer, 2005). In a similar view, Opong (2012) reasons that, much like all theoretic prospect decision makers, the frame of reference of most migrants guides their decision making, and their reference points are deep seated in the prevailing conditions in their home countries. This reference point is affected by and interlinked with the migrants' social-economic conditions in the country of destination, which in turn shapes migrants' perceptions of the current situation in their home countries. According to Stark and Lucas (1988) and Rapoport and Docquier (2006), the reality of conditions in migrants' home countries influence their behavioural patterns and judgment, and in the long run determine how money is sent home, how often, how much is sent and to whom.

Prospect theory contains many remarkable insights that link with the social and economic milieu of migrants, and in incorporating remittance motives Opong (2012) maintains that remittance behaviour depends on both migrants' abilities (i.e. their income and savings) and their motives to remit. From this perspective, remittance decision making and behaviour is a function of a migrant's characteristics, willingness and ability to remit (Lucas & Stark 1985, Rapoport & Docquier, 2006). Based on this notion, the willingness and motivation of the prospective remitter has been hypothesized as related to altruism and self-interest (Lucas & Stark, 1985; Taylor, 1999) as well as tempered or enlightened motives (Poirine, 1997; Lillard & Willis, 1997). The self-enlightened motive of remittances was expanded by Hagen-Zanker and Siegel (2007) to include contractual arrangements, such as co-insurance, loan repayment and exchange between migrant and household members in the country of origin.

Under an altruistic model, the intuitive motive to remit is the migrants' concern about relatives left behind in the home country. In a nutshell, a migrant may derive satisfaction from ensuring the welfare of his or her relatives (Lucas & Stark, 1988; Stark, 1991; Solimano, 2003). In a behavioural sense, altruism implies a utility function in which the migrant cares about the consumption needs of the family members left behind (Banerjee, 1984; Lillard & Willis, 1997; Agarwal & Horowitz, 2002). Further to altruistic assumptions, migrants with higher earning potential tend to remit more money and goods, and remittances tend to increase if the migrant is married and the spouse and/or children are in the country of origin (Frankhouser, 1995; Von Burgsdorff, 2010; Von Burgsdorff, 2012; Chisasa, 2014). However, in a post-hoc strategy that follows migration, when the families join migrants, the ties and links with the home country become weaker and the amount of remittances decrease and are sent less frequently (Sana & Massey, 2005; Kosse & Vermeulen, 2014).

In addition, intentions to return are positively correlated with the tendency to remit more (Konica & Filer, 2005; Lindley, 2007; Lindley, 2008), and the amount that a migrant sends to relatives in the home country is negatively correlated with the number of migrants from the same household. Furthermore, the time profile of remittances as propounded in the remittance decay hypothesis (that remittances decline as the length of residence increases) depends on the profile of migrants, i.e. migrants who stay longer abroad tend to remit at a decreasing rate (Stark, 1978; Agunias, 2006; Amuedo-Dorantes & Pozo, 2006; Vargas-Silva, 2006; Makina & Massenge, 2014; Echazarram, 2011). Likewise, remittances are positively correlated with income, while the number of dependents in the host country affects remittances adversely (Frankhouser, 1995; Holst & Schrooten, 2006).

In a similar view to the above, migrants who perceive the business environment in their countries of origin to be favorable will remit more money and goods in the form of investments (Lucas & Stark, 1985), and migrants who regularly visit their home countries are more likely to send remittances (Lindley, 2007; Lindley, 2009; Lindley, 2010). Much like the altruistic hypothesis, in the self-interest motive, migrants who maintain links with home countries are more likely to remit, especially when they are willing to return to their countries of origin (Hoddinott, 1994; Cox et al., 1998; De la Briere et al., 2002; Agunias, 2006).

In a pure self-interest motive, migrants driven by the prospect of inheritance send remittances to maintain family income and financial stability. Under this hypothesis, remitters are expected to have a higher chance to inherit assets, whereas the higher the value of assets to be inherited is likely to be associated with the higher remittances. For example, Osili (2007 and Hoddinott (1994) found that migrants remit more in wealthier areas. Likewise, Schrieder and Knerr (2000), Garip (2006) and Holst and Schrooten (2006) affirmed that with an inheritance seeking motive, male emigrants remit significantly more compared to female emigrants. However, according to Cracium (2006), the exceptions are that women remit a substantially larger proportion of their wages than men.

In reaction to pure altruism and pure self-interest motives, Stark and Lucas (1988) used an eclectic model termed "tempered altruism" and "enlightened self-interest" to explain contractual arrangements of co-insurance, exchange motives and loan repayment in driving remittances. A number of sources stress that in the eclectic model, remittances are utilized as a familial strategy to maximize an income and to insure against future shocks (Stark, 1991; Poirine, 1997; Brown & Ahlburh, 1999; Solimano, 2003). The family enters into an implicit pre-determined agreement in which they either invest in the education of the remitter or finance the cost of migration, while the remittances they receive are used to repay the loan that financed the cost of migration and education. Under this assumption, scholars report that educated migrants are likely to remit more (Hoddinott, 1994; Ilahi & Jffarey, 1999).

From the behaviour and motivation theoretical synthetic models, it is evident that the complex mixture of altruism, self-interest and self-enlightenment best describes the theoretical aspect of remittances. However, when combined with micro-variables representing migrants' characteristics, remittance behaviours are difficult to predict. Therefore, to ascertain whether there is a link between migrants' characteristics and remittance behaviour, the researcher developed the function consisting of principal independent variables. These variables have been prominently linked to remittances in the literature.

Remittance behaviour (RB) = N + A + Ge + MS + EL + IRSA + DTISA + RI + DSSA + IL + ABSA + FHV + A

Variable description:

• Nationality = N

• Age = A

• Gender = Ge

• Marital status = MS

• Educational level = EL

• Immigration reasons to South Africa = IRSA

• Document types in South Africa = DTSA

• Return intentions = RI

• Duration of stay in South Africa = DSSA

• Income level = IL

• Access to banks in South Africa = ABSA

• Frequency of home visits = FHV

• Associations = A

Methodology

The study used both quantitative and qualitative methods. The information was collected using structured survey questionnaires administered to 83 migrants. Additionally, interviews and focus group discussions were conducted with 12 migrants from the DRC, Rwanda, Somalia and Zimbabwe who live in Cape Town, South Africa. Cape Town is of interest as it is a cosmopolitan city that receives migrants from the African continent and has a history of migrant settlement (Lefko-Everett, 2008). Similarly, from the researcher's observations, Cape Town's largest inner-city sections account for a high number of migrants from the case study. The sample was selected by means of non-probabilistic method, where the researcher applied the purposive approach to select the sample of migrants as an entry point based on his knowledge and the nature of the research aims. The sample was then extended by means of snowballing to reach more participants by referral.

To mitigate the risks of bias and errors associated with the non-probability sampling method, a considerable effort was made to include migrants of varied demographics in terms of age, gender, occupation, nationality and legal status. In addition, the non-probability sampling approach enabled the researcher to overcome the difficulty of locating undocumented migrants. In a similar view, combining purposive and snowballing sampling methods enabled the researcher to choose the respondents included in the study and increase subjects' variability, thus minimizing the challenges of finding the representative sample (Babbie & Mouton, 2001; Mertens & Gisenberg, 2009).

On the one hand, variables representing characteristics of migrants were categorised according to demographic information, such as nationality, age, gender, education, marital status, duration of stay in South Africa, income level, migration history, family context (i.e., migration status, reason for immigration and return intention), family size in both South Africa and the home country, level of social capital and access to financial institutions and banking facilities. On the other hand, remittance patterns and behaviour-specific variables were disaggregated to include remittance type (i.e., cash, goods and social remittances) propensity to remit, value and amount of remittances, frequency of remittances, as well as channels used to send remittances.

The data analysis was based on a combination of both primary and secondary data, and the goal was to link remittance behaviour with migrants' characteristics. To do so, a statistical analysis was performed on the data collected from the survey questionnaires using STATA software. In order to describe, explain, interpret and summarise the characteristics of the migrants and their remittances, descriptive statistics in the form of mathematical quantities were used, while inferential statistics were employed to ascertain whether remittance behaviour differs depending upon migration characteristics. The qualitative data were analysed using thematic content analysis. This involved breaking data from the interviews into more manageable themes, triangulating them with those from the focus group and comparing the findings with information from the literature review.

Disaggregating remittances into many types posed a challenge and incorporating and analysing the aspects of social remittances created incoherence in this paper. This was due to the fact that these kinds of remittances are intangible in nature and difficult to measure compared to financial transfers (Mohamoud & Fréchaut, 2006: 34). Similarly, the quantitative approach did not provide detailed or nuanced narratives from migrants' responses. Nonetheless, these methodological shortcomings were offset by the qualitative method employed. A quantitative method provides data that may be effectively used to predict and measure relationships and phenomena (Babbie & Mouton, 2001; Mertens & Gisenberg, 2009). As such, the quantitative method was selected for this research as it proved to be more affordable and faster than the qualitative method, especially when testing hypotheses.

Results and Discussions

Demographic Characteristics

Out of a sample of 83 respondents, 20 participants (24%) are from Zimbabwe, 20 (24%) are from Rwanda, 20 (24%) are from Somalia, and the remaining 23 (28%) are from the DRC. There is no considerable difference in terms of educational background across nationalities, apart from the Rwandese, of whom half attained university degrees. Otherwise, many of the pooled sample (31%) indicated they had completed secondary school, 17% had attained primary school, 23% had achieved a college qualification, 28% had completed tertiary education and 1% had obtained another type of education. The average monthly income of 34% of respondents falls between R4000-8000, 22% receive R1500-4000, 26% receive R8000-15000 and 18% receive R15000 or more.

Relating to migration context and family history of migrants, 63% of the respondents belong to an association or diaspora organisation, compared to the remaining 37% who do not. A relatively high number of migrants have access to banking institutions in both South Africa and their countries of origin, and 64% of the respondents indicated they have bank accounts in South Africa, compared to 36% who do not. 58% of the respondents indicated that their relatives have access to financial and banking institutions in their home countries. With regard to returning home, in this study, 61% of participants reported that they intended to return home permanently at some point in time, while 39% said that they did not have such intentions. Out of those who intend to return to and settle permanently in their countries of origin, the majority (65%) are planning to do so in a period of four years or more.

Concerning a visit to their home countries, more than half of the pooled sample (51%) stated they had not visited their home country, 18% indicated that they have travelled home once, 12% indicated that they visit every few years, 11% visit once a year, 6% twice a year and the remaining 2% visit their home country every three months. In addition, the majority of the respondents (not including Zimbabweans) are holders of refugee status (33%) and asylum seeker permits (17%). Other types of documents held are as follows: work permit (12%), partnership permits (4%), permanent residence permit (14%), study permit (6%), business permit (2%), other permits (1%). The remaining 11% are undocumented.

Zimbabweans' frequency of home visits is high and the intention to return permanently is common, while on average the majority of respondents from Rwanda, Somalia and the DRC do not visit their respective countries very often. The low incidence of return intentions among migrants from these countries could be linked to the fact that their countries experienced insecurity and civil wars in the past. According to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2010), Somalia is still characterised by insurgency. Similarly, their low frequency of home visits is linked to the type of documents the migrants hold and their motives of migration. According to Lawyers for Human Rights Watch (LHRW) (2009) and the UNHCR (2010), the South African Department of Home Affairs revokes the residence permits of asylum seekers and refugees who travel to their native countries.

In terms of their motivation for coming to South Africa, 51% of the surveyed respondents cited political instability in their respective countries, 7% cited study reasons, 18% cited economic reasons, 13% cited family reunification, 10% cited business opportunity and 1% cited other reasons. When disaggregated across nationality, many respondents from Zimbabwe cited perceived economic and business opportunities as the motive for coming to South Africa, as opposed to those from the DRC, Rwanda and Somalia, who indicated political instability.

To sum up, the majority of the Zimbabwean participants' movement to South Africa was voluntary. According to the LHRW (2009) and UNHCR (2010), a person who leaves his or her home country for fear of persecution can apply for asylum and, if accepted, will be called a 'refugee'. Using a combination of the reason for migration, type of documentation, frequency of home visits and return intentions, one can conclude that the majority of Zimbabweans are economic migrants (voluntary), as opposed to Rwandese, Congolese and Somalis, whose movement to South Africa is forced and who thus qualify as 'refugees' or 'forced migrants'.

Remittance Patterns and Behaviour of African Immigrants

All respondents agreed that they send some kind of remittances home. The types of remittances identified were cash, goods or commodities and social remittances. 80% of the respondents transmit social remittances, 53% remit cash and goods simultaneously, 41% remit cash only and 6% remit goods only. When disaggregated according to nationality, the remittance patterns do not vary considerably. However, Somalis remit slightly more socially. This finding was reinforced by the information gleaned from qualitative data, as explained by a participant from Somalia:

South Africa is technologically advanced with modernized learning and strong democratic institutions that can help our countries to develop. We have learnt a lot in terms of skills and democratic practices, next time when we go home, we will ensure accountability and transparency in the public sector.

The study also revealed that Zimbabweans tend to remit more than any other nationality in terms of cash and goods, while goods only predominate among those from the DRC and Somalia. The high transfers among Zimbabweans corresponds with other studies (e.g. Makina, 2007; Maphosa, 2007; Von Burgsdorff, 2010), which found that remittances to Zimbabwe have increased because of its rapidly declining economic conditions that have been accentuated by severe drought.

The prominence of social remittances among migrants from Somalia is undoubtedly associated with the fact that they belong to the Somali Association of South Africa (SASA), with one of its missions being to facilitate Somali migrants' learning and integration in South Africa. Nevertheless, for the study cohort as a whole, further investigations divulged that apart from skills, technology and democratic values, some social and cultural practices that are perceived to be negative (participants referred to these aspects as negative social remittances) are also transmitted to the countries of origin, as highlighted by a female Rwandan participant from the focus group:

South Africa is a country where everything is tolerated and accepted. In our countries, homosexuality and lesbianism are taboo, this Western like culture has been adopted and promoted by the South African constitution and passed to us and our children and when they go back home, they take it with.

In terms of remittances in the form of goods, a relatively high level of transfers of goods among Congolese (the majority of whom are refugees) is likely linked to the availability of channels. This is described by a male Congolese participant in the excerpt below:

[...] Nowadays, we don't struggle to send something home; it is just the matter of waiting for the bus to arrive from Lubumbashi, and then send something home through the passengers.

These findings on the sending of remittances by Congolese refugees give testament to other studies (e.g. Akuei, 2005; Jacobsen, 2005; Loschmann & Siegel, 2014), which found that temporary forced migrants hoping to return home in non-distant future are likely to remit. This is not surprising, as under an altruistic motive, refugee remittances constitute an important mechanism that provides support to family members through periods of famine, conflict and war (Lindley, 2007; Lindley, 2008; Lindley, 2009). They also provide real and substantial bulwarks to protect family members' human rights (Cockayne & Shetret, 2012).

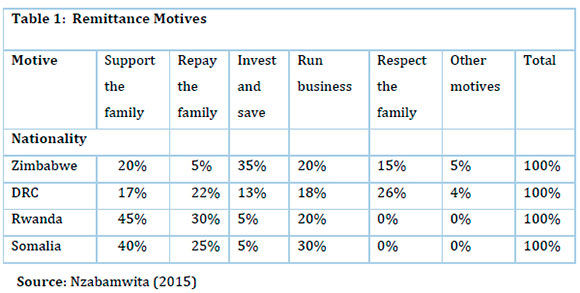

This study found that 30% of the respondents remit to support their families. The remaining 20% of the respondents remit to repay their families, 13% remit to save and invest in their countries, 11% remit to inject cash in their businesses, 23% remit to respect their families and the remaining 2% remit for other reasons. These findings again substantiate all aspects of the prospect hypotheses that remittances are determined by altruism (Lucas & Stark, 1988; Stark, 1991; Solimano, 2003), self-interest (Hoddinott, 1994; Cox, et al., 1998; De la Briere, et al., 2002; Agunias, 2006), enlightened self-interests, which include familial arrangements of co-insurance, loan repayment and inheritance motives (Lucas & Stark, 1985; Stark, 1991; Hoddinott, 1994; Poirine, 1997; Brown & Ahlburh, 1999; Taylor, 1999; Osili, 2004).

A deeper analysis of Table 1 reveals that many Zimbabweans remit to invest and save in their home countries, while Somalis and Rwandese remit for family-related reasons. Again, this is not surprising as the study found the majority of Zimbabweans to be economic migrants, and Rwandese, Congolese and Somalis to be refugees. According to Phyillis and Kathrin (2008), refugees mainly remit to help family members left behind escape human rights violations. The implication of this is that economic migrants' remittances are driven by pure self- interest, while forced migrants' remittances are based on altruistic motives. This is in line with Cockyane and Shetret's (2012) report that refugees mainly remit to help family members left behind.

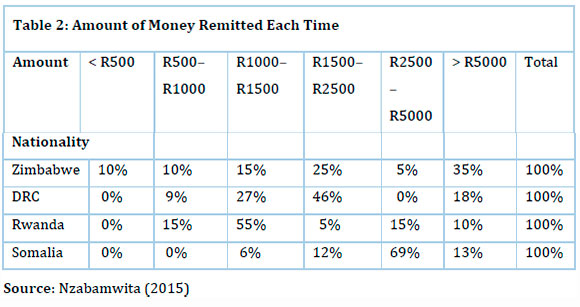

With regards to the values of remittances, out of 78 respondents who indicated that they send cash, the majority (39%) noted that they send R1000-R2500, and the rest of the remittance transactions vary as follows: 9% remit R500-R1000, 32% remit R2500-R5000, and the remaining 19% remit R5000 and above. As indicated in Table 2, the amount of cash remitted does not follow a specific pattern based on nationality, however, Zimbabweans tend to remit the highest amounts, followed by Congolese. This confirms other studies that found that economic migrants remit more than refugees (Phyillis & Kathrin, 2008). A possible explanation is that conflict-induced migration happens to save migrants' lives rather than diversifying income (Lindley, 2008; Lindley, 2009) and forced migrants are not likely to have enough resources in the initial period of their arrival compared to voluntary migrants, so they only tend to remit long after full integration into the host country (Ghosh, 2006).

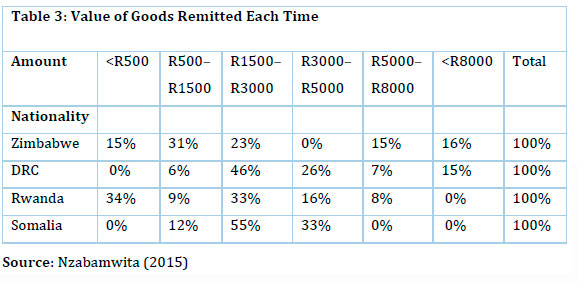

Regarding the value of goods, the majority of the respondents (66%) indicated that they send goods worth R500-R3000 each time goods are sent, 12% remit goods to the value of less than R500, 8% remit goods worth R5000-R8000 and the remaining 8% remit goods worth R5000 or more. Table 3 indicates that the Congolese and Zimbabweans remit relatively high values of goods compared to the rest of the group. Goods remittances to Zimbabwe are perhaps related to production that dwindled after the implementation of land reform policies (see Kerzner, 2006; Kerzner, 2009; Polzer, 2010). Another potential explanation is the close proximity between South Africa and Zimbabwe (Makina, 2007; Makina, 2010; Chisasa, 2014) coupled with a shortage of currency as acknowledged by two Zimbabwean participants during an interview:

Let me tell you something, every time I sent money to my son for school fees, he travels from the village to town to get it, he is always told to come back the following day, because the bank does not have money (P1: Participant from Zimbabwe).

With the lack of American Dollars in the Zimbabwean banks, I prefer to buy stuff in South Africa, so that I can get cash when I re-sell them in Harare (P2: Participant from Zimbabwe).

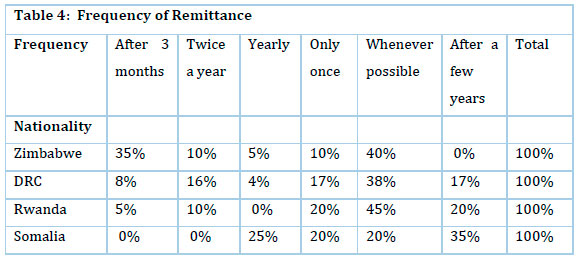

When asked about the kinds of goods that are most commonly remitted, electronics are the most preferred goods at 43%, cosmetic products at 18%, clothing items at 4%, furniture at 16% and other items such as motor spare parts, medicine and stationery at 18%. This is a true reflection of the assumptions of prospect theory that remittances are anchored in the needs and conditions arising in the migrants' countries of origin. The Rwandese have the highest percentage in sending electronics (67%), while the Zimbabweans lead in furniture. This is not a coincidence. The geographical proximity of Zimbabwe and South Africa facilitates the remittance of non-durable goods (Von Burgsdorff, 2012; Chisasa, 2014; Makina & Masenge, 2014), while tax exemption concessions on Information Computer Technology (ICT) items provided by the Rwandan Revenue Services (Harrison, 2005) could encourage Rwandese migrants to remit electronic goods. Furthermore, migrants tend to remit irregularly; 12% do so every three months, 10% twice a year, 8% once a year, 17% every few years, 17% remitted only once, and the remaining 36% remit whenever it is possible. Table 4 notes that Zimbabweans tend to remit more frequently and Somalis less frequently; this is consistent with the view that economic migrants remit more often than forced migrants (Briant, 2005).

Relationships between the Characteristics of African Migrants and Remittance Patterns/Behaviour

To ascertain whether a relationship exists between migrants' characteristics and remittance behaviour, inferential statistics were used along with a non-parametric technique and the Pearson's Chi-square test. The non-parametric technique involved cross-tabulation of remittance behaviour and patterns with the characteristics of migrants.

In carrying out the test, a significant level of 0.05 (5%) was used for the test of 1 degree of freedom. The decision rule is that the significance level of 0.05 is allowed, and a Pearson chi-square value or p-value higher than the significance level indicates that the difference between the groups is not significant (Pallant, 2005: 286).

The chi-square test provided mixed results. This section only reports on the variables representing migrants' characteristics that are statistically associated with remittance behaviour. The full chi-square test results are indicated in Appendix 1. The test revealed that there is a significant relationship between nationality and type of remittances (x2=14.31, P=0.026), amount of cash remitted (x2=46.83, P=0.000), type of goods remitted (x2=23.33, P=0.025), remittance frequency (x2=34.88, P=0.003), goods remittance channels (x2=47.74, P=0.000), and cash remittances channels (x2=62.896, P=0.000). Remittance patterns by nationality show that Zimbabweans more frequently remit goods of high value using informal channels, compared to immigrants from other countries in this study. This is not surprising as Zimbabweans are mainly economic migrants and Phyillis and Kathrin (2008) note that economic migrants remit more than refugees.

With regard to education, the test results show a significant relationship between education and the amount of cash remitted (x2=33.14, P=0.032), channels for cash remittances (x2=36.17, P=0.050) and channels for social remittances (x2=40.73, P=0.004). In this study, the finding indicates that more educated migrants are likely to send more in terms of goods and cash through formal channels. In a similar view, highly educated African migrants are more likely to remit socially upon their return home. This finding on social remittances corresponds with Perez-Armendariz and Crow's (2009) idea that education influences social remittance. The results on material remittances contradict the original claim of Evtimova and Koekoek (2010) that educated migrants remit less and invest more in host countries. This, however, substantiates and supports the view of Orozco (2006) that educated migrants remit more formally.

In addition, the income level is significantly related to social remittances (x2=7.42, P=0.060), amount of cash remitted (x2=76.31, P=0.000) and the value of goods remitted (x2=52.35, P=0.000). The current study revealed that migrants earning a high income remit more in the form of cash and goods and are also more likely to remit socially. These results are not surprising, as they corroborate the findings of other authors who have suggested that there is a positive relationship between income and remittance (De Haas & Plague, 2006; DMA, 2011).

For other variables, the reason for coming to South Africa is significantly related to the cash remittance channels (x2=58.77, P=0.001), as well as goods remittance channels (x2=48.57, P=0.003). In a similar view to the above, there is a significant relationship between immigration status and cash remittance channels (x2=67.95, P=0.030). Additionally, the intention to return home is significantly related to the frequency of remittances (x2=32.69, P=0.005), as well as the cash remittance channels (x2=25.13, P=0.048). Access to banks or financial institutions in South Africa is significantly related to cash remittance channels (x2=17.84, P=0.007). Furthermore, the frequency of visits to the home country is significantly related to the value of goods remitted (x2=41.63, P=0.020), cash remittance channels (x2=46.33, P=0.029) and goods remittance channels (x2=38.67, P=0.040). Lastly, the level of association in South Africa is significantly related to social remittances. For details, please see Appendix 1.

Although, variables of age, gender, marital status and duration of stay in South Africa are not factors influencing remittance behaviour among African migrants in South Africa, a thorough examination of the chi-square test results in Appendix 1 demonstrates that more than half of variables representing migrants' characteristics (10 variables out of 15) are significantly associated with remittance behaviour. Therefore, one can conclude that, overall, the characteristics of migrants are linked to remittance patterns and behaviour.

Conclusion

The aim of the study reported in this paper was to link the characteristics of African migrants with their remittance behaviour. This paper has shown that the decisions to migrate and remit are inherently interlinked. The fact that migrants from Somalia, Rwanda and the DRC hold refugee status and asylum seeker permits and migrated because of political insecurity make them forced migrants. Zimbabweans, on the other hand, are voluntary migrants whose motive for immigration to South Africa is economic. With regards to remittance behaviour, this study found that African migrants send all types of remittances (i.e., cash, goods and social remittances) to their respective countries, and their nature and characteristics have a significant impact on what types of remittances are sent, how they sent, how often they are sent and to whom. In this regard, economic migrants remit to invest and save in their home countries, while refugees remit to support their family members.

Regarding migrants' characteristics, this study further revealed that the nationality of migrants determines type of remittances, the amount of cash remitted, the type of goods remitted, the frequency of remittances, the channels used to remit cash, as well as the channels used to remit goods. Education and income determine the value of remittances as well as the channels used to remit. Among migrants who remit, Zimbabweans tend to remit cash and goods more frequently. Somalis, on the other hand, take advantage of their associations to send social remittances. Rwandese remit the highest amounts of electronic goods and they tend to use formal channels. Highly educated and high-income African migrants remit more in terms of both amount of cash and value of goods, and they also tend to use formal channels.

References

Adepoju, A. 2000b. Regional migration trends: Sub-Saharan Africa, World Migration Report. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. [ Links ]

Adepoju, A. 2003b. Continuity and changing configurations of migration to and from the Republic of South Africa. International Migration, 43: 2-28. [ Links ]

Africa Check, 2017. How many Zimbabweans live in South Africa? The Numbers are unreliable. From <https://africacheck.org/reports/how-many-zimbabweans-livein-south-africa-the-numbers-are-unreliable/> (Retrieved December 14,.2017).

Agarwal, R. and Horowitz, A. 2002. Are international remittances altruism or insurance? Evidence from Guyana using multiple-migrant households. World Development, 30 (11): 2033-2044. [ Links ]

Agunias, D.R. 2006. Remittances and development: Trends, impact and policy option- Review of the literature. Washington, D.C: Migration Policy Institute. [ Links ]

Akuei, S. 2005. Remittances as unforeseen burdens: The Livelihoods and social obligations of Sudanese refugees, Global Migration Perspectives. Geneva: Global Commission in International Migration. [ Links ]

Amuedo-Dorantes, C. and Pozo, S. 2006. Remittances as insurance: Evidence from Mexican immigrants. Journal of Population Economics, 19(2): 227-254. [ Links ]

Anderson, B.A. 2006. Migration in South Africa in comparative perspective. In: Kok, P., et al, (Eds.). Migration in South Africa and Southern Africa: Dynamics and determinants. Cape Town: Human Science Research Council. pp. 97-117. [ Links ]

Babbie, E. and Mouton, J. 2001. The Practice of social research. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bakewell, O. 2011. Migration and development in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Phillips, N., (ed.). Migration in the global political economy. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. [ Links ]

Banerjee, B. 1984. The probability, size and uses of remittances from urban to rural areas in India. Journal of Development Economics, 16(3): 293-311. [ Links ]

Barberis, N.C. 2013. Thirteen years of prospect theory in economics: A Review and assessment. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(1): 173-199. [ Links ]

Bester, H., Hougard, C. and Chamberlain, D. 2010. Reviewing the policy framework for money transfers. Cape Town: The Centre for Financial Regulation and Inclusion of the University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Breyetenbach, W.J. 1979. Migratory labour arrangements in Southern Africa. Pretoria: Africa Institute of South Africa. [ Links ]

Briant, S. 2005. The Remittances sending behaviour of Liberian refugees in Providence. Thesis for MA Development Studies, Brown: Brown University. [ Links ]

Brown, R. and Ahlburh, D. 1999. Remittances in the South Pacific. International Journal of Social Economics, 26(1): 325-344. [ Links ]

Buencamino, L. and Gurbonov, S. 2002. Informal money transfer systems: Opportunities and challenges for development finance. DESA Discussion Paper No. 27, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Carmerer, C. 2005. Three cheers: Psychological, theoretical, and empirical for loss aversion. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(2): 129-133. [ Links ]

Chisasa, J. 2014. Natures and characteristics of informal migrant remittance transfer channels: Empirical study of remittances from South Africa to Zimbabwe. Banks and Bank Systems, 9(2). [ Links ]

Cockayne. J. and Shetret, L. 2012. Harsening Somali remittances for counterterrorism, Human Rights and State Building. Washington, D.C.: Centre for Counterterrorism and Cooperation. [ Links ]

Cohen, J.H. and Rodriguez, L. 2005. Remittance outcomes in rural Oaxaca, Mexico: Challenges, options and opportunities for migrant households. Population Space and Place, 1(1): 49-63. [ Links ]

Cox, D., Eser, Z. and Jimenez, E. 1998. Motives for private transfers over the life cycle: An Analytical framework and evidence for Peru. Journal of Development Economics, 55(1): 57-80. [ Links ]

Cracium, C. 2006. Migration and remittances in the Republic of Molodova: Empirical evidence at Micro Level. Kiev National University: Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

Crush, J. 2000. An Historical overview of cross-border movement in Southern Africa. In: McDonald, D. (Ed.). On Borders: Perspectives on international migration in Southern Africa. New York: St. Martin's Press. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Williams, V. and Perbedy, S. 2005. International migration and development dynamics and challenges in South and Southern Africa. New York: United Nations Secretariat. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Peberdy, S. & Williams, V. 2006. International migration and good governance in the Southern African Region: Migration Policy Brief 17, Kingston and Cape Town: Southern Africa Migration Project. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. and Plague, R. 2006. Cherishing the goose with golden eggs: Trends in migrant remittances from Europe to Morocco 1970-2004. International Migration Review, 40(3): 603-634. [ Links ]

De la Briere, B., Sadoulet, E., de Janvry, A. and Lamberts, S. 2002. The Roles of destination, gender and household composition in explaining remittances: An Analysis for the Dominican Sierra. Journal of Development Economics, 68(2): 309-328. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M.F. and Carciotto, S. 2015. International migration in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): A Call for a global research agenda. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 1(2): 154-177. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M.F. and Nyasulu, T. 2015. Macroeconomic determinants: Analysis of 'Pull' factors of international migration in South Africa. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 1(1): 27-52. [ Links ]

Developing Markets Associates (DMA). 2011. Constraints in the UK to Ghana remittances market: Survey analysis and recommendations. From <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67581/Constraints-UK-Ghana.pdf> (Retrieved September 06, 2015).

Echazarram A., 2011. Accounting for the time pattern of remittances in the Spanish context. Working Paper No. 5-2010. Manchester: Centre for Census and Survey Research. [ Links ]

Evtimova, A. and Koekoek, R. 2010. Mobile money as an option for facilitating remittances, Case study: Research within Indian migrant workers. Amsterdam: Dialogues Incubator. [ Links ]

Frankhouser, E. 1995. Remittances from international migration: A Comparison of El Salvador and Nicaragua. Review of Economics and Statistics, 77(1): 137-46. [ Links ]

Garip, F. 2006. Social and economic determinants of migration and remittances: An Analysis of 22 Thai Villages. Princeton: Princeton University. [ Links ]

Ghosh, B. 2006. Migrants' remittances and development: Myths, rhetoric and realities. Netherlands: The Hague Process on Refugees and Migration.

Goldring, L., 2002. The Mexican state and trans-migrant organizations: Negotiating the boundaries of membership and participation. Latin American Research Review, 37(3): 55-99. [ Links ]

Goldring, L. 2004. Family and collective remittances to Mexico: A Multidimensional typology. Development and Change, 35(4): 799-840. [ Links ]

Hagen-Zanker, J. and Siegel, M. 2007. The Determinants of remittances: A review of the literature, Working Paper 2007/03. Maastricht: Maastricht Graduate School of Governance. [ Links ]

Harrison, B. 2005. Information and communication technology in Rwanda. From <http://www.rita.gov.rw/index.html> (Retrieved October 14, 2015).

Hoddinott, J. 1994. A Model of migration and remittances applied to Western Kenya. Oxford Economic Papers, 46(3): 459-476. [ Links ]

Holst, E. and Schrooten, M. 2006. Migration and money: What determines remittances? Evidence from Germany. Discussion paper No. 556. Berlin: German Institute for Economic Research. [ Links ]

Ilahi, N. and Jafarey, S. 1999. Guest-worker migration, remittances and the extended family: Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Development Economics, 58: 485-512. [ Links ]

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017. Challenges in migration in Southern Africa. IOM, Regional Office for Southern Africa. From <http://www.europarl.europa.eu/intcoop/acp/2016_botswana/pdf/warn-en.pdf> (Retrieved July 17, 2018).

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2016. Strategic approach: Migration regional strategy for Southern Africa for 2014-2016. From <https://southafrica.iom.int/system/files/drupal-private/IOM_Regional_Strategy_forSouthernAfrica.pdf> (Retrieved July 13, 2018).

Jacobsen, K. 2005. The Economic life of refugees. Bloomfield: Kumarian Press. [ Links ]

Kahnerman, A. and Tversky, A. 1979. Prospect theory: An Analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2): 263-290. [ Links ]

Kahnerman, D. and Tversky, A. 1991. Risk aversion in riskless choice: A Reference dependent model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4): 1039-1061. [ Links ]

Kahnerman, D. and Tversky, A. 2000. Choices, values and frames. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kerzner, S. 2006. Annual remittance for Zimbabwean corridor. A Think piece prepared for FinMark Trust. From <http://www.cenfri.org> (Retrieved October 10, 2014).

Kerzner, S. 2009. Cash and curry: Understanding the Johannesburg- Zimbabwe remittance corridor. Discussion Document prepared for the FinMark Trust. From <https://bit.ly/2AheftF> (Retrieved July 10, 2017).

Kok, P., Gelderblom, D., Oucho, J.O. and Van Zyl, J. 2006. Migration in South Africa and Southern Africa: Dynamics and determinants. Cape Town: Human Science Research Council. [ Links ]

Konica, N. and Filer, R.K. 2005. Albanian emigration: Causes and consequences. Working Paper. Prague: CERGE-EI. [ Links ]

Kosse, A. and Vermeulen, R. 2014. Migrants' choice of remittance channel: Do General payment habits play a role? European Central Bank Working Paper Series No 1683, June 2014.

Lefko-Everett, K. 2008. Aliens, migrants, refugees and interlopers: Perceptions of foreigners in South Africa. Pretoria: Institute for Democracy in South Africa (IDASA). [ Links ]

Levitt, P. 1998. Social remittances: Migration driven local level forms of cultural diffusion. International Migration Review, 32(4): 926-948. [ Links ]

Levitt, P. and Joworsky, B.N. 2007. Transnational migration studies: Past developments and future trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 33: 129-156. [ Links ]

Levitt, P. and Lamba-Nieves, D. 2011. Social remittances revisited. Journal of Ethnics and Migration Studies, 37: 1-22. [ Links ]

Lawyers for Human Rights Watch (LHRW). 2009. Protecting refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in South Africa. From <https://bit.ly/2P8uWjb> (Retrieved November 10, 2015).

Lillard, L. and Willis, L.J. 1997. Motives for intergenerational transfers: Evidence from Malaysia. Demography, 34: 115-34. [ Links ]

Lindley, A. 2007. Protracted displacement and remittances: The View from Eastleigh in Nairobi. UNHCR New Issues in Refugee Research No. 143. Geneva: UNHCR. [ Links ]

Lindley, A. 2008. Conflict-induced migration and remittances: Exploring conceptual frameworks. Working Paper Series No. 47. Oxford: Oxford University Refugee Study Centre. [ Links ]

Lindley, A. 2009. The Early-morning phone call: Remittances from a refugee diaspora perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Study, 35(8): 13151334. [ Links ]

Lindley, A. 2010. The Early morning phone call: Somali refugees' remittances. New York: Berghahn. [ Links ]

Loschmann, C. and Siegel, M. 2014. Revisiting the motivations behind remittance behaviour: Evidence of debt-financed migration in Afghanistan. Migration Letters, 12(1): 38-49. [ Links ]

Lucas, R. and Stark O. 1985. Motivations to remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy, 93(5): 901-918. [ Links ]

Makhema, M. 2009. Social protection for refugees and asylum seekers in the Southern Africa Development Community. Discussion paper No. 0906. Special Protection and Labour. Washington DC: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Makina, D. 2007. Survey of profile of Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa: A Pilot study. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Makina, D. 2010. Zimbabweans in Johannesburg. In: Crush, J. and Tavera, D. (Eds.). Zimbabwe's exodus: Crisis, migration and survival. Cape Town: SAMP Publications. [ Links ]

Makina, D. and Masenge, A. 2014. The Time pattern of remittances and the decay hypothesis: Evidence from migrants in South Africa. Migration Letters, 12(1): 79-90. [ Links ]

Maphosa, F. 2007. The Impact of remittances from Zimbabweans working in South Africa on rural livelihoods in the Southern Districts of Zimbabwe. The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA).

Mertens, M. and Gisenberg, E. 2009. The Handbook of social research ethics, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Mohamoud, A.A. and Fréchaut, M. 2006. Social remittances of the African Diaspora in Europe. Lisbon: North-South Centre of the Council of Europe. [ Links ]

Mukasa, R. 2012. Determinants of migrant remittances: A Case of Ugandan community in Cape Town, South Africa. Unpublished MA Thesis. University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Nzabamwita, J. 2015. Exploring the link between international migration and remittances: A Case study of African immigrants in Cape Town, South Africa. Master's Thesis. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Opong, K.K. 2012. Prospect theory and migrant remittance decision making. From <http://ssrn.com/abstract=2127615> (Retrieved February 13, 2015).

Orozco, M. 2006. Global remittances and the law: A Review of regional trends and regulatory issues. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Dialogue. [ Links ]

Osili, O.U. 2007. Remittances and savings from international migration: Theory and evidence using a matched sample. Journal of Development Economics, 83(2): 446-465. [ Links ]

Paerregaard K. 2008. Peruvians dispersed: A Global ethnography of migration. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Pantoja AD. [ Links ]

Pallant, J. 2005. SPSS Survival manual: A Step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS Windows. Sydney: National Library of Australia. [ Links ]

Peberdy, S. 2009. Selecting immigrants: National identity and South Africa's immigration policies 1910-2008. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Perez-Armendariz, C. and Crow, D. 2009. Do Migrants remit democracy? International migration, political beliefs and behaviour in Mexico. Berkley: University of Texas. [ Links ]

Polzer, T. 2010. Silence and fragmentation: South African responses to Zimbabwean migration. In: Crush, J. and Tavera, D. (Eds.). Zimbabwe's exodus: Crisis, migration and survival. Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Poirine, B. 1997. A Theory of remittances as an implicit family loan arrangement. World Development, 25: 589-611. [ Links ]

Phyillis, J.J. and Kathrin, S. 2008. Remittance patterns of Southern Sudanese refugee men: Enacting the global breadwiner role. Consumer Interests Annual, 5. [ Links ]

Rapoport, H. and Docquier, F. 2006. The Economics of migrants' remittances. In: S.C. Kolm and J.M. Ythier (Eds.). Handbook of the economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland. [ Links ]

Ratha, D., Mohapatra, S. and Silwal, A. 2009. Outlook for remittance flows 2009-2011: Remittances expected to fall by 7-10 per cent in 2009. Migration and Development Brief Report 10. Washington DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

Sana, M. and Massey, D.S. 2005. Household composition, family migration and community context: Migrant remittances in four countries. Social Science Quarterly, 86(2): 509-528. [ Links ]

Schrieder, G. and Knerr, B. 2000. Labour migration as a social security mechanism for smallholder households in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Cameroon. Oxford Development Studies, 28(2): 223-236. [ Links ]

Segatti, A. and Landau, B.L. 2011. Contemporary migration to South Africa: A Regional development issues. Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. [ Links ]

Solimano, A. 2003. Remittances by emigrants: Issues and evidence. In: Cheru, F. (Ed.). The Millennium Goals: Raising the resources to tackle World Poverty. Chicago: Chicago University Press. pp. 73-96. [ Links ]

Stark, O. 1978. Economic-demographic interaction in Agricultural development: The Case of rural to urban migration. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [ Links ]

Stark, O. 1991. The Migration of labor. Blackwell, Oxford.

Stark, O. and Lucas, R.E.B. 1988. Migration, remittances and family. Journal of Economic Development and Cultural Changes, 36(3): 465-481. [ Links ]

Stupart, R. 2016. Is South Africa home to more than a million asylum seekers? The numbers don't add up. From <http://bit.ly/2cEcHxI> (Retrieved November 15, 2017).

Styan, D. 2007. The security of Africans beyond borders: Migration, remittances and London's transnational entrepreneurs. International Affairs, 83(1): 1171-1191. [ Links ]

Suliman, A.H.E., Ebaidalla, E.M. and Ahmed, A.A. 2014. The impact of migrant remittances on national economy and household income: Some evidence from selected Sudanese states. In: Bariagaber, A. (Eds.). International migration and development in Eastern and Southern Africa. Addis-Ababa: OSSREA. [ Links ]

Taylor, J.E. 1999. The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration, 37(1): 63-88. [ Links ]

Taylor, J.E. 2000. Do government programs 'crowd in' remittances? Washington, DC: Inter-American Dialogue and Tom'as Rivera Policy Institute. [ Links ]

Tavera, D. and Chikanda, A. 2009. Migrant remittances and household survival in Zimbabwe. Migration Policy Series. No. 51, IDASA.

Technoserve, 2015. The digital remittance revolution in South Africa: Challenge and next steps for Africa's largest cross-border payments market. From <http://www.technoserve.org/files/downloads/South-Africa-international-remittances-report.pdf> (Retrieved July 10, 2018).

Truen, S., Bester, H., Ketley, R., Davis, B., Hutchson, H.D., Kwakwa, K. and Mogapi, S. 2005. Supporting remittances in Southern Africa: Estimating market potential and assessing regulatory obstacles. Report prepared by Genesis Analytics for CGAP and FinMark Trust. From <http://www.finmark.org.za> (Retrieved February 10, 2014).

Truen, S. and Chisadza, S. 2012. The South Africa- SADC remittance channel. Prepared by DNA Economics for FinMark Trust. From <http://www.finmark.org.za> (Retrieved January 15, 2015).

Tsietsi, M., 1998. Country report: Lesotho's trends and prospects for the 21st century. Paper presented at the regional meeting, Gaborone, 2-5 June, UNESCO.

Tversky, A. and Kahnerman, D. 1992. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4): 297-324. [ Links ]

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2010. Asylum level and trends in Industrialised countries. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. [ Links ]

Van Doorn, J. 2002. Migration, remittances and development. From <http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/gurn/00073.pdf> (Retrieved March 12, 2015).