Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.4 no.1 Cape Town 2018

ARTICLES

The Regularization of Zimbabwean Migrants: a Case of Permanent Temporariness

Sergio Carciotto

Associate Director at the Scalabrini Institute for Human Mobility in Africa (SIHMA). Email: director@sihma.org.za

ABSTRACT

Since the early 2000s there has been a proliferation of policy initiatives in high income countries to attract highly skilled migrants who are perceived to be net contributors to host societies. Generally, highly skilled migrants enjoy numerous socio-economic opportunities and benefit from fast-track procedures to switch from temporary visas to permanent residency. South Africa has sought to capitalize on this trend through domestic legislation and policy that promotes economic growth by facilitating the admission of highly skilled workers. However, these measures have also prevented low-skilled workers from applying for permanent residency, irrespective of their length of time in the country. These policies beg the question whether it is morally acceptable for a liberal democracy to deny a pathway to permanent residency based on skill level.

The paper draws on Joseph H. Carens' theory of citizenship and the principle that "the longer one stays in a society, the stronger one's claim to remain. " It uses the example of the Dispensation for Zimbabwean Project, a large regularization programme for temporary workers introduced in South Africa in 2010 to argue that temporary status should not be "permanent," but should lead to permanent residency after a period of time.

Keywords: Permanent residence, temporary migration, dispensation for Zimbabwean project, ethics.

Introduction

In his article titled "Back to the future? Can Europe meet its labor needs through temporary, migration?" Stephen Castles inquires whether temporary worker schemes introduced in Europe in the 2000s would resemble past guest worker programs which were abolished in 1974. Such programmes provided employers with young unskilled workers who were unmarried or had left their families at home and worked on a "rotation basis" (Rotationsprinzip) in agriculture, construction, mining, and manufacturing (Jurgens, 2010:348). His answer to the question is no. However, he argues that "some current approaches do share important common features with past guest worker programs, especially through discriminatory rules that deny rights to migrant workers" (Castles, 2006:1). Castles further observes that unlike older guest worker programs, immigration policies and temporary migration schemes in Europe target highly skilled migrants, while restricting entry for less qualified workers and limiting their rights.

With regard to working conditions, Castle writes, "lower-skilled workers experience highly restrictive conditions, with limitations on duration of stay and the right to change jobs" (Castles and Ozkul, 2014:30). They face exploitation and abuses, "have a time-limited right to residence and employment in the host country and time spent in employment as a guest worker usually does not count or help them to earn permanent residence rights" (Ruhs and Martin, 2008:250). Temporary migrant workers, particularly low-skilled migrants, are treated as "second-class citizens" at risk of becoming part of a new model of "indentured servitude" (De Genova as cited in Castles, 2014:41).

Temporary forms of migration raise a normative question about the socioeconomic rights of those who are neither citizens nor long-term residents. They also pose the question of whether the number of years spent in a country should be considered a legitimate and morally acceptable criteria to access permanent residency. If the answer to this question is no, as some argue, temporary workers should not be able to qualify for permanent residency, irrespective of how long they have been in the host country. The term "temporary migrant" refers here to migrant workers employed in low-skilled jobs and excludes other categories of temporary migrants such as asylum seekers, highly skilled workers, foreign investors and international students, to whom many countries offer a fast-track from temporary to permanent residency and full socio-economic rights.

Temporary Workers and Rights

As noted by Ruhs (2012:1288) "the question about rights involves questions about the rights migrants should receive after admission and whether and how these rights should change over time." He further argues that the legal rights of migrants depend on their immigration status in the host country and that selective immigration policies are used to "tightly regulate migrants" access to citizenship status and to specific citizenship rights' (ibid: 1288). Some theorists (Ruhs and Martin, 2008) argue that denying temporary low-skilled workers equal rights is justified by economic needs. They maintain that there is, in fact, a "trade-off, i.e. an inverse relationship between the number of migrants employed in low-skilled jobs in high-income countries, and the rights afforded these migrants. The primary reason for this trade-off is that employer demand for labor is negatively sloped with respect to labor costs, and that more rights for migrants typically means higher costs." (ibid: 251). In this kind of situation, both employers and migrant workers have something to gain: the former benefits from a reduction in labor costs or to meet a labor shortage, while the latter has an opportunity to migrate safely and legally. According to the "number-rights/trade-off principle" described above, granting more employment rights to migrant workers would simply reduce employers' demand and, therefore, the number of low-skilled migrants legally employed.

Others (Bell, 2006) have argued that a system of unequal rights, as in the case of East Asia, is tolerable because migrant workers accept terms and conditions of employment before they go abroad. This raises the question whether temporary migrants "are better off because they are more likely to be employed or less well off because they endure poorer working conditions" (Fauvelle-Aymar, 2015:14). This paper argues that temporary workers should enjoy the same employment rights that citizens and permanent residents possess. A contractual approach to temporary migration might, in fact, be convenient from the point of view of practical politics, but it cannot be justified on moral grounds as it tolerates a system of "second class" residents with fewer rights. But nonetheless, if those migrants who enter into this kind of working agreement do so voluntarily and, therefore, are willing to receive less rights, this should only be temporary and limited to short term non-renewable visas. An exploitative system where migrant workers' rights are restricted ad infinitum would not be acceptable and should not be justified even when migrants are willing to accept fewer rights.

The question about what rights migrants should receive after their admission and how these rights should change over time remains a highly contentious issue. Political theorist Joseph H. Carens (2008a; 2008b; 2008c; 2013) provides an answer to this ethical dilemma. He notes that democratic states can admit migrants for a limited period of time and restrict their access to public assistance programs but other restrictions are morally problematic. His argument is based on the assumption that the claim to be a member of a political community grows as time spent in a country increases, irrespective of the condition of sojourn or immigration status. Moreover, democratic legitimacy "lies upon the inclusion of the entire settled population, including those migrants who have spent numerous years in a society and deserve to be included in the citizenry" (Carens, 2008b:22). Membership acquired over an extended period of time spent in a society explains why prolonged temporary status ought to lead automatically to permanent residency first and to citizenship (naturalization) afterwards:

[I]f people admitted to work on a temporary visa have no other moral claim to residence than their presence in the state, it is normally reasonable to expect people who have only been present for a year or two to leave when their visa expires. On the other hand, if a temporary visa of this sort is renewed, it ought at some point to be converted into a right of permanent residence. That is also the implication of the principle that the longer the stay, the stronger the claim to remain. (Carens, 2008a:422).

The importance of continuous residency leading to permanent residency is echoed by Mares (2017:20) who notes that "the starting point for a consistent liberal response to temporary migration must be a pathway to permanent residence that is, after a certain period of time, unconditional." It therefore follows that, according to Carens' point of view, temporary workers must not be allowed "to morph into a permanent underclass" (UN General Assembly, 2017:10) and should enjoy the same universal legal rights as native workers. He argues that after a given time (five to ten years) the moral claim of temporary workers for permanent residency and citizenship can be considered legitimate. Carens' theory of citizenship, labeled social membership, is based on the principle that "the longer a person stays, the stronger is his or her claim to remain" (Carens, 2008a; 2008b; 2008c).

Still the main question remains. Is it legitimate for temporary migrants to acquire, after a set number of years, the legal rights afforded to citizens and long-term residents? Let me try to answer this question with a concrete example: the Dispensation of Zimbabweans Project approved by the Cabinet in South Africa in 2009.

The Regularization of Zimbabwean Migrants

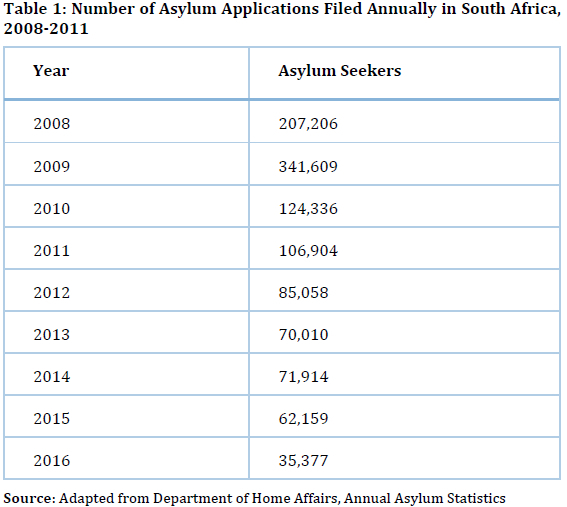

From 2008 to 2011, South Africa received the highest number of individual asylum applications globally, with a peak of over 300,000 applications in 2009 (Table 1) making it the world's largest recipient of asylum seekers that year. This fact caused delays in adjudication times and allowed economic migrants without a legitimate asylum claim to reside and work legally in the country. The increase in asylum claims led the Department of Home Affairs "to implement restrictive practices and policies, stemming both physical access at the border and at the refugee reception offices (RROs), as well as access to protection in adjudication procedures" (Johnson and Carciotto, 2016:169).

In response to this crisis, one policy adopted to ease the pressure on the asylum system was the implementation of a large regularization program for Zimbabwean nationals in South Africa. In 2009, the Cabinet approved the Dispensation of Zimbabweans Project - or 'DZP' - allowing Zimbabwean holders of this special permit to work, conduct business and study in South Africa. At the launch of the DZP in 2010, the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) estimated that there were approximately 1.5 million undocumented Zimbabweans in South Africa (Bimha, 2017).

The DZP relaxed the normal requirements for work, study, or business permits. Applicants were required to submit a valid Zimbabwean passport, evidence of employment in the case of a work permit, evidence of business in the case of an application for a business permit, and an admission letter from a recognized learning institution in the case of a study permit (Amit 2011). The objectives of the 'DZP' then were to: a) regularize Zimbabweans residing in South Africa illegally; b) curb the deportation of Zimbabweans who were in South Africa illegally; c) reduce pressure on the asylum seeker and refugee regime, and d) provide amnesty to Zimbabweans who obtained South African documents fraudulently. Just over 245,000 non-renewable temporary permits were issued with a validity of four years.

In August 2014, four months before the expiration date of the Zimbabwean special permits (31 December 2014), the Minister of Home Affairs announced the launch of a new Zimbabwean Special Dispensation Permit (ZSP) targeting DZP permit-holders who wished to remain in South Africa after the expiry of their permits. The ZSP allowed permit-holders to live, work, conduct business and study in South Africa for an additional three years until 31 December, 2017.

Despite having announced in 2016 that the ZSP would be terminated at the end of 2017, the DHA later announced the availability of the new Zimbabwean Exemption Permit (ZEP) which allowed ZSP holders to work, study and conduct business for an additional period of four years until 31 December 2021. The then Minister of Home Affairs, Hlengiwe Mkhize, remarked that the ZEP was in line with the White Paper on International Migration Policy, approved by the Cabinet in 2017, and was part of a larger effort to address the inflows of low-skilled labor migrants from neighboring South African Development Community (SADC) countries. This is not the first time that South African government has attempted to address the issue of irregular migration within the region: between 1995 and 2000 three regularization projects for contract and undocumented migrant workers from SADC countries were implemented. However, unlike the three previous regularizations which "were designed to give target populations permanent residence status in South Africa" (Peberdy, 2001:20), the DZP, ZSP and ZEP programmes did not allow permit-holders to apply for permanent residence despite their long, continuous tenure in the country. This exclusionary practice raises numerous concerns. Given the fact that "the eligibility criterion for accessing most social assistance benefits is South African citizenship or permanent residence" (Deacon, et al., 2014) the lack of a pathway to permanent residency restricts migrants' access to social benefits.

In South Africa, all temporary workers are excluded from accessing social assistance, are not entitled to claim unemployment funds and are excluded from accessing unemployment insurance if they are ill or on maternity or adoption leave (ibid, 2014:24). Access to housing and basic education for temporary workers is also restricted by the government (See Table 2). Moreover, low-skilled temporary workers are much more likely to occupy low-wage, precarious jobs than South Africans (ACMS, 2017). In addition, temporary workers are tied to a specific kind of work and are not allowed to change employers. Such restrictions can make migrant workers vulnerable, as recounted by a Zimbabwean national who was granted a permit to work as a gardener under the DZP dispensation and later secured a job in the construction industry:

I worked for a month at the construction site because it paid better than working as a gardener. After the first month we were taken to Kimberley to do some work for a few weeks. However, when we got there we encountered people from Home Affairs who were checking for papers [legal documentation]. I was immediately arrested because I was doing a job that was not mentioned in my permit. It was a nightmare. I was told that I would be deported but it took long for me to be deported. I spent one and a half months at a holding centre in Kimberley. They keep you there for some time till they have arrested enough people to fill a truck. (Deacon, et al., 2014:50).

The Constitution of South Africa guarantees equality before the law and the right to equal protection and does not justify discrimination based purely on residency. Yet temporary low-skilled workers are vulnerable to exploitation and are not afforded equal protection. Regularization programmes such as the ZDP, the ZSP and the ZEP address permanent labor shortages and fill permanent jobs with temporary workers. Such workers should not be denied a path to permanent residency.

The 2017 White Paper on International Migration

The Immigration Act of 2002 provides for various types of temporary visas with worker rights, and makes holders of work visas eligible for permanent residency after a period of five consecutive years. Section 31(2)(b) of the Act allows the Minister of Home Affairs "to grant, under specific terms and conditions, a foreigner or a category of foreigners the rights of permanent residence for a specified or unspecified period when special circumstances exist which should justify such a decision." (South Africa, 2002).

Provided certain conditions are met, this system "effectively creates automatic qualification for permanent residency and subsequently for citizenship. Thus one of the main criteria used to qualify for permanent residency is the period of stay in the country, irrespective of the type of temporary residence visa initially issued, or purpose of entry" (DHA, 2017:41). However, the 2017 White Paper on International Migration seeks to modify this approach so that the guiding principle to grant permanent residency and naturalization would be the type of residence visa rather than the number of years spent in the country. This policy framework -- which restricts citizenship rights for temporary low-skilled migrants-- is morally questionable and contravenes the principle that "the longer the stay, the stronger the claim to full membership in society and to the enjoyment of the same rights as citizens."

The White Paper was approved by the Cabinet in March 2017 with the aim of providing a policy framework to guide the review of immigration and related legislation. According to the South African government, the rationale for an overhaul of migration legislation is the economic, social and legislative changes that have occurred in South Africa during the past eighteen years. The White Paper attempts to respond to the needs of a country that has become a major destination for economic migrants, refugees, students, cross-border traders and entrepreneurs from Africa and the rest of the world. It recommends strategic interventions in eight policy areas: management of admission and departure; management of residency and naturalization; management of international migrants with skills and capital; management of ties with South African expatriates; management of international migration within the African context; management of asylum seekers and refugees; management of the international process for international migrants, and; management of enforcement.

The White Paper argues that the current system fails to address the challenges posed by mixed migration flows from neighboring countries "with regard to semi-skilled and unskilled economic migrants, who have been largely unable to obtain visas and permits through the mainstream immigration regime" (ibid:52). This system has had some negative consequences, including a national asylum system overwhelmed and abused by economic migrants, the exploitation of African workers by some South African employers, corruption by police and immigration officials, and costly and ineffective deportation measures.

In line with the National Development Plan (NDP) the new migration policy seeks to attract, acquire, and retain the necessary skills by recruiting migrants in a more strategic way in order to achieve national priorities and economic growth. It attempts to align South Africa's international migration policy with its African-centered foreign policy to better address economic migration of low-skilled and unskilled migrants from the SADC region. To address the growth of undocumented migration and the existing gaps in legislation, the White Paper suggests three strategic initiatives to improve the management of low-skilled economic migrants by expanding the current visa regime (ibid: 56).

First, a new SADC visa would be tied to a programme to regularize existing undocumented SADC migrants residing in South Africa along the same lines as the ZSP and other amnesties that South Africa has conducted over the years.

Second, the White Paper would expand the visa regime to address economic migration from neighboring countries. At least three types of visas are recommended for piloting. The SADC special work visa would allow the holder to work in South Africa in a specific sector for a prescribed period of time. It would be based on a quota-regime implemented through bilateral agreements. The number of visas would be based on labor market dynamics like employment levels and the share of jobs held by foreign nationals. The SADC traders' visa would be a long-term, multiple-entry visa for cross border traders who frequently enter and exit the Republic. The SADC small medium enterprise (SME) visa would be available for the self-employed and for small business owners.

Third, the White Paper provides for stronger enforcement of immigration and labor laws. It seeks to strengthen the enforcement of labor and migration laws in order to ensure fair employment practices and that unscrupulous employers do not pay lower wages to migrants.

One of the most significant features of these new temporary schemes for low-skilled migrants is the absence of pathways to permanent legal status. At present, the Immigration Act of 2002 allows holders of certain temporary residence visas under specific conditions to apply for a permanent residence permit and subsequently for citizenship. Thus, access to permanent residency is based on the number of years spent in the country, irrespective of the type of temporary visa initially issued.

In the government's view, this approach "does not allow the granting of residency and naturalization to be used strategically" (ibid: 42) and in the best interest of national priorities. Hence, there should not be any automatic progression from residency to citizenship, in order to "dispel a misconception that immigrants have a constitutional right to progress towards citizenship status on the basis of a number of years spent in the country" (ibid:42).

In the future, long-term visas may replace permanent permits and be granted only to those migrants who possess high levels of human and financial capital. This new policy will mean that highly skilled workers, investors and international students graduating in critical skill occupations will receive preferential admission conditions and easy access to permanent residency, while temporary low-skilled migrants will not.

Thus, the White Paper would negatively impact the rights and social conditions of temporary low-skilled African migrants, who will no longer have the right to settle permanently. The granting of permanent residency based on highly selective criteria is, in fact, a tool to control and restrict access to civic, political and social rights, including the substantive rights of citizenship.

The planned measures to introduce a new visa regime for low-skilled temporary workers acknowledge the demand for low-skilled workers in specific economic sectors, as well as the existence of prevailing colonial circular movements and migration patterns to South Africa. However, this policy plan falls short in addressing issues of "employee portability rights" for temporary contract workers and gives the impression of replicating circular and temporary schemes "which tie migrant workers to certain sectors and employers for a pre-defined period of time, limiting the duration of stay and the right to change job" (Castles, 2014:41). Furthermore, the idea presented in the White Paper of delinking permanent residency from the duration of stay is problematic and morally questionable.

This policy runs afoul of human rights and the common good, which demand policies that benefit all members of a given community. In this regard, "long-term settlement does carry moral weight and eventually even grounds a moral right to stay that ought to be recognized in law" (Carens, 2008b:36).

Conclusion

In South Africa, temporary and exploitative forms of migration date back to colonial times when migrant workers were considered a source of cheap labor for white-owned farms and mines, thus setting the foundation for separate development and the apartheid regime. Since the inception of democracy in 1994 and particularly over the past two decades, South Africa has undergone a protracted process of developing policy and legislation on migration. One of the key policy documents issued by the South African government is the White Paper on International Migration, which supports the enlargement of the current visa regime through the implementation of regularization programmes to accommodate temporary low-skilled workers and reduce the influx of undocumented migrants from neighbouring countries. Examples of these interventions are the Dispensation for Zimbabwean Project, the Zimbabwean Special Dispensation and the Zimbabwean Exemption Permit to regularize migrant workers in South Africa.

Originally meant to last only for a period of four years, these programmes, which allow temporary migrants to be employed in different areas such as the hospitality and construction industries, are, at the time of writing, in their eighth year of implementation. Such programmes do not intend to address short term labor shortages in South Africa, as the nature of the work that permit-holders conduct is not temporary. Yet permit holders will be excluded from a pathway to permanent residency.

The fact that after a long period of time Zimbabweans are not allowed to graduate to a permanent legal status under the law indicates how recent policy interventions in South Africa aim to weaken the nexus between the continuous period of residence in the country and permanent residency. This contravenes Carens' ethical principle that "the longer people stay in a society, the stronger they are morally entitled to the same civil, economic, and social rights as citizens, whether they acquire formal citizenship status or not" (Carens, 2013: 89). According to Carens' theory of social membership, the claim to membership grows over time and it is the length of residence, not the legal status that is the key moral variable. Moreover, democratic legitimacy rests upon the meaningful participation in civic life of the entire population, including temporary workers who have spent a large part of their lives in the country.

Temporary schemes such as the DZP, the ZSP and the ZEP do not resemble European guest worker programmes aimed at filling the demand for cheap labor which were abolished in the late 1970s. However, they introduce limitations on the right to change jobs and to access some work-related social programs.

The limitation of certain legal rights (e.g., right to vote or to hold high public office) is justifiable when temporary migrants are only permitted to remain for a limited time but not when temporary visas are renewed numerous times for multiple consecutive years. In this case, at some point, temporary visa holders should be converted into permanent residence and temporariness should come to an end. Non-access to permanent residency, in fact, makes migrant workers more vulnerable and their "temporary status" creates barriers to a meaningful assertion to work-related and social rights.

Recommendations

Temporary labor schemes represent one of the most controversial topics addressed by the Zero Draft of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, which was released by the United Nations on 5 February 2018. The following recommendations on these programs are drawn from the TEN ACTS document drafted by civil society and the 20 Action Points prepared by the Vatican Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development's Section on Migrants and Refugees.

1. Ensure that all migrants are protected by their countries of destination, in order to prevent exploitation, forced labor and human trafficking. This can be achieved by prohibiting employers from withholding employees' documents; by ensuring access to justice for all migrants, independently of their legal status and without negative repercussions on their right to remain; by ensuring that all immigrants can open a personal bank account; by establishing a minimum wage applicable to all workers; and by ensuring that wages are paid at least once a month.

2. The integrity and well-being of the family should always be protected and promoted, independently of legal status. This can be achieved by embracing broader family reunification (grandparents, grandchildren and siblings) independent of financial requirements; allowing reunified family members to work; undertaking the search for lost family members; combating the exploitation of minors; and ensuring that, if employed, minors' work does not adversely affect their health or their right to education

3. Strengthen the role of the International Labour Organization (ILO), in cooperation with other international agencies, to ensure public availability, transparency, accountability, and human rights norms and standards in bilateral, regional and international agreements on labor mobility, rights and decent work; ensure the implementation of these agreements; and ratify, implement and cooperate transnationally on the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, as well as other human and labor rights conventions.

4. Ensure that all recruitment-related fees are borne by the employer, not the migrant worker; operationalize international standards and cooperation to regulate and monitor migrant labor recruitment and employment; and eliminate abuses of migrant workers and the use of forced labor in supply chains.

5. Enact national policies that provide foreign residents with access to justice, regardless of their migratory status, allowing them to report human rights abuses and violence without fear of reprisal, including abuses suffered in detention and deportation.

6. Access to welfare should be assured to all migrants, respecting their right to health and basic healthcare independent of legal status, and ensuring access to national pension schemes and the transferability of benefits in case of moving to another country.

7. Implement the SADC Protocol on the Facilitation of the Free Movement of Persons, the draft Protocol on Employment and Labour, and the SADC portability of Social Security Benefits Framework.

8. Include provisions for low-skilled workers in regional labor mobility protocols and assure that labor migration programs guarantee full labor rights and protections for migrants.

9. Ensure that anyone who is allowed to remain in the country for more than a specific time is allowed to graduate to a permanent legal status. On this topic, the Zero Draft of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration falls short as it does not encourage the adoption of a pathway to permanent residency for all migrant workers.

10. As indicated by the Zero Draft of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, temporary migrants should be allowed to change employers.

11. Adopt laws which allow for the regularization of status for long term residents of the host country.

References

African Centre for Migration & Society (ACMS). 2017. Fact sheet on foreign workers in South Africa. Unpublished Report. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Amit, R. 2011. The Zimbabwean documentation process: Lessons learned. African Centre for Migration and Society.

Bell, D. A. 2006. Beyond Liberal Democracy: Political Thinking for an East Asian Context. Princeton: University Press. [ Links ]

Bimha, P. Z. J. 2017. Legalising the illegal: An assessment of the Dispensation of Zimbabweans Project (DZP) and Zimbabwe Special Dispensation Permit (ZSP) regularisation projects. Master Thesis (Unpublished). Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Carens, J. H. 2008a. Live-In Domestics, Seasonal Workers, and Others Hard to Locate on the Map of Democracy. Journal of political philosophy 16(4): 419445. [ Links ]

Carens, J. H. 2008b. Of States, Rights, and Social Closure. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Carens, J. H. 2008c: The Rights of Irregular Migrants. Ethics & international affairs 22 (2): 163-186. [ Links ]

Carens, J. H. 2013. The Ethics of Immigration. Oxford: University. [ Links ]

Castles, S. 2006. Guestworkers in Europe: A resurrection? International Migration Review 40(4): 741-766. [ Links ]

Castles, S. and Derya O. 2014. Circular Migration: Triple Win, or a New Label for Temporary Migration? In: Battistella, G. (Ed.). Global and Asian perspectives on international migration. Vol. 4. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Deacon, B. Marius P. O. and Reason B. 2014. Social Security and Social Protection of Migrants in South Africa and SADC. African Centre for Migration and Society, University of the Witwatersrand.

Department of Home Affairs (DHA). 2017. White Paper on International Migration. Policy Report.

Fauvelle-Aymar, C. 2015. Immigration and the South African labour market. MiWORC Working Paper 2. From <http://bit.ly/2BEMskr> (Retrieved April 17, 2018).

Mares, P. 2017. Locating Temporary Migrants on the Map of Australian Democracy. Migration, Mobility, & Displacement 3 (1): 9-31. [ Links ]

Mpedi, L. George. 2011. Code on social security in the Southern African development community. De Jure 44 (1):18-31. [ Links ]

Johnson, C, and Carciotto, S. 2016. The State of Asylum System in South Africa. In: O'Sullivan, M. and Stevens, D. (Eds.). States, the Law and Access to Refugee Protection: Fortresses and Fairness. Bloomsbury, 167-179.

Jurgens, J. 2010. The Legacies of Labor Recruitment: The Guest Worker and Green Card Programs in the Federal Republic of Germany. Policy and Society 29 (4): 345-355. [ Links ]

Peberdy, S. (2001). Imagining Immigration: Inclusive Identities and Exclusive Policies in Post-1994 South Africa. Africa Today 48 (3), 15-32. [ Links ]

Ruhs, M. and Philip M. 2008. Numbers vs. Rights: Trade-Offs and Guest Worker Programs. International Migration Review 42 (1): 249-265. [ Links ]

Ruhs, M. 2012. The Human Rights of Migrant Workers: Why Do So Few Countries Care? American Behavioral Scientist 56 (9): 1277-1293. [ Links ]

South Africa. Immigration Act 13 of 2002. From <https://bit.ly/2vm5LBc> (Retrieved April 17, 2018).

UN General Assembly, 2017. Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary General on Migration. From <http://bit.ly/2q6mrrK> (Retrieved April 17, 2018).