Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.3 Cape Town 2017

ARTICLES

North-South Migration and Problems of Migrant Traders in Agbogbloshie

Razak Jaha Imoro

Assistant Lecturer, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Email: jaha792001@yahoo.com / rimoro1@ucc.edu.gh

ABSTRACT

In this paper, the problems of labour migrants in their destination areas will be investigated, owing to the need for a deeper understanding of their specific livelihood problems in these areas. Using a mixed method approach to data collection, 100 migrant traders in Agbogbloshie, in the south industrial area of Accra, were interviewed about their livelihood problems. The data analysed revealed that the majority of labour migrants were not formally educated and were primarily involved in the trading of consumables. Additionally, conflict, poverty, decline in agriculture productivity and unavailability of social amenities were important factors that influenced their north-south migration in Ghana. Furthermore, inability to access credit facilities, theft of migrant traders' wares, discrimination against migrants, exploitation of migrants by market leaders and harassment by city authorities were some of the problems that migrant traders faced. Dependent on these findings, to effectively minimise these problems, it is suggested that migrant traders should unionise as this can help them access credit from formal financial institutions. It would also present migrants with a common voice to engage in dialogue with city authorities on the appropriate ways of managing their activities in the market.

Keywords: Internal Migration, migrant traders, destination, livelihoods, Ghana.

Introduction

Internal migration is a common global phenomenon. The United Nations Development Programme (2012) shows that people are engaged in more internal than international migration. Available statistics suggest that approximately 244 million people migrated internationally in 2015 up from 222 million in 2010 and 173 million in 2000, while approximately 740 million people migrated internally throughout the world within the same period (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2016). This raises questions about factors accounting for the disparity. Though it is easy for one to think of issues of distance, visas and costs involved in immigration, other multifaceted factors contribute to the preponderance of internal migration the world over and are thus worthy of attention. The internal migration situation in West Africa is no different from the global trend. Evidence shows high rates of internal migration within the sub-region (Cote d'lvoire and Senegal, 62%; Mauritania, 54%; Mali and Guinea, 51%; Niger, 47%; and Burkina Faso 30%) (Tanle, 2010). The relative statistic for Ghana is 52%, showing little difference between it and the stated West African countries above. In light of this evidence showing the global dominance of internal migration over international migration, continentally and within the West African sub-region, an important aspect of the migration process that calls for research is the situation of migrants in their destination areas within countries.

In Ghana, a trend that calls for investigation into migrant problems in destination areas is the north-south migration. Apart from its historical antecedent, this remains an enduring phenomenon. The colonial agenda promoted the movement of people from northern Ghana to the south in order to serve as labourers in the mines and in cocoa growing areas (Plange, 1979; Songsore, 2003). During the independence era, migrations were dominated by independent individual motives. Subsequently, the post-independence era has witnessed an increased number of females joining the migration stream to southern Ghana (Songsore, 1983; Abdul-Korah, 2008; Tanle, 2010). Some women migrate to southern Ghana to serve as 'kayayei', female porters who carry goods on their heads for a negotiated fee. Others work in 'chop bars' (local restaurants) as cleaners (Awumbila, 2015). Tanle (2003) also cited as a key factor in their north-south migration, the desire of certain women to save money in order to enter into large-scale trading at their places of origin. Other women saved money to buy personal effects, such as clothes, shoes, jewels and kitchenware in preparation for marriage. Samsu-deen (2015) has indicated in his study that north-south female migration in Ghana is driven by the quest for wealth and the escape from poverty and the lack of social amenities in communities of origin. The gendered nature of the female north-south migration is also characterised by women working in low-skilled jobs in destination areas, in domestic and care work, hotel and catering services, the entertainment and sex industry, agriculture and on assembly lines (Awumbila et al., 2015). Additionally, these sectors are quite regularly characterised by poor working conditions, low pay, withheld wages, considerable insecurity and a high risk of sexual harassment, exploitation and abuse (Akter, 2015).

From colonial to post-independence times, the northern sector of Ghana has kept this trend of out-migrations to the south, but the reasons for these migrations have changed over time (Imoro, 2011; Van der Geest, 2011; Kwankye, 2012a). For instance, socio-economic and climatic variables have induced north-south migrations (Abdul-Korah, 2008; Anamzoya, 2010; Van der Geest, 2011; Alenoma, 2013). Additional important factors, such as unemployment, poverty, the desire to acquire life's necessities, marital-related issues, the desire to invest and protracted conflicts, have been cited as reasons behind north-south migration streams in Ghana (Awumbila et al., 2011; Participatory Poverty and Vulnerability Assessment Ghana, 2011).

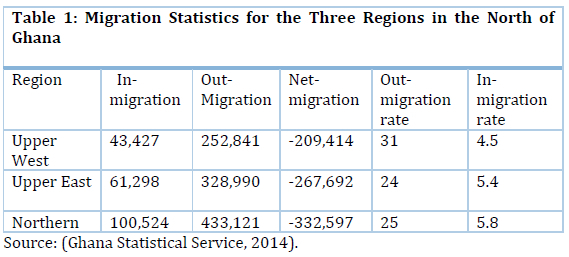

Furthermore, an infrastructure deficit in the areas of transportation, housing, energy and education in the northern parts of Ghana has contributed to north-south migratory movement (Awumbila & Ardayfio, 2008; Imoro, 2011). Adaawen and Owusu (2013) indicated that migrants strongly anticipate earning income that will enable them to remit funds to support and improve the well-being of family members back home, hence their north-south migration. The literature reviewed above on the north-south migration flow can be supported by the data from the Ghana Statistical Service (2014), which indicate that three regions in the north of Ghana are net migrant regions, as shown in Table 1.

All studies cited above have made important contributions to the literature on north-south migration in Ghana. However, an area within this migration discourse that is little known is the nature of migrants' livelihood strategies and their problems within their destination areas. Migrants in these areas are confronted daily with survival necessities such as food, shelter, accommodation, health and security issues. These are woven into their livelihood activities, or the daily strategies of migrants, which implies that the ability of migrants to survive in destination areas is dependant on the livelihood survival mechanisms available and the migrants' assets in the destination areas. Such livelihood problems and activities are often glossed over by researchers. Therefore, in this paper, investigation of the livelihood strategies and problems of migrants in a destination area is aimed at broadening the scope of literature in the field of migration in general, and in Ghana in particular. The paper is also intended to contribute to a better understanding of migrant problems in destination areas and could serve as a significant information source for city authorities on problems of migrant traders in Agbogbloshie, Accra, Ghana. It also offers a policy recommendation to the general problem of migrant adjustment to urban economic life.

Migration and Sustainable Livelihoods

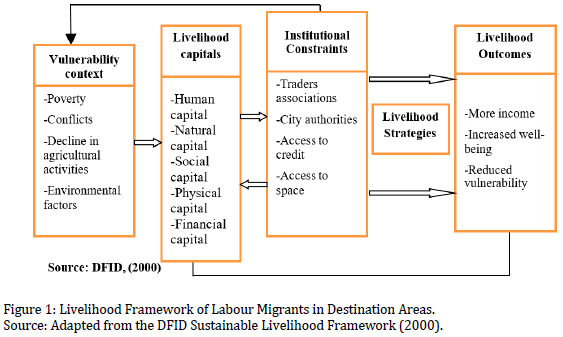

Migrants' in destination areas are generally confronted with livelihood problems. How they are able to overcome these problems shows their resilience and ability to improve their socio-economic existence. Their conditions of work and the problems they face mirror the broader frame of a livelihood strategy. In the case of migrants, the sustainability of their livelihoods is dependent on the conditions and situations that confront them in destination areas and how they are able to navigate these situations. In order to grasp the livelihood activities of migrant traders in Agbogbloshie in Accra, a Department for International Development (DFID) version of a sustainable livelihood framework was used to understand the intricacies that surround and affect the livelihood outcomes of migrant traders. This DFID version of a livelihood framework addressed the key issues in this paper, including the vulnerability, livelihood assets, institutional constraints, livelihood strategies and livelihood outcomes of these migrants, as shown in Figure 1.

Concept of Sustainable Livelihood

The concept is popular both in development planning and urban studies and is applied here to help illuminate the discourse on migrant traders in urban destinations. The concept emerged in the early 1990s and has received different interpretations based on its applications in different disciplines; for instance, in development research, sociology, economics and agriculture (Scoones, 2009). The broad term, 'sustainable livelihood', is used to explain and analyse how individuals, groups, localities and societies, in general, utilise their available resources in such a way so as to guarantee them continuous survival on a daily basis (Scoones, 2009; Chambers, 1983). Therefore, just how sustainable livelihoods are depends on the context within which livelihoods operate. In the case of migrants, the sustainability of their livelihoods is dependent on the conditions and situations that confront them in destination areas, and how they are able to navigate within these situations. The simplest definition of 'livelihood' can be traced to Chambers (1995), who defined the concept as the means of gaining a living, or as a combination of the resources used and the activities undertaken in order to live. But a more popular and workable definition postulated earlier by Chambers and Conway (1992) is worthy of note: a livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (including both material and social resources) and activities required for a means of living; a livelihood is sustainable when it can cope with and recover from stresses and shocks and maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets, while not undermining the natural resource base. Hence, a livelihood approach is a nuanced picture of a web of activities in which people engage in order to secure a means of living. This paper views a livelihood as the totality of activities, resources and networks that migrants in urban areas can access as a means of living.

Vulnerability Context of Migrant Traders

Vulnerability is a concept that has emerged in the development literature to explain the situations or conditions that expose people to challenges in their daily lives. In the context of sustainable livelihood, vulnerability is influenced by the external environment, over which people have little or no control. The vulnerability contexts of people impose on them shocks and stresses that tend to influence their asset base, reduce their capabilities or restrict household activities (Department for International Development, 2000).

To be in a vulnerable situation may stem from several sources. For instance, vulnerability in development discourse may refer to conditions of poverty, unemployment, inflation, weak governance structures and external debts. These may affect people differently. This further implies that vulnerability is the way and manner in which people exposed to risk factors tackle these risk factors, given their entire range of livelihood options (Scoones, 1998). One of these livelihood options includes out-migration. In the context of this study, vulnerability meant poverty, conflicts, environmental factors and decline in agricultural activities. These factors influenced migrant traders to leave their communities of origin for their destination in Accra. However, these factors were not mutually exclusive. People in these vulnerable contexts resort to other means to escape such conditions; one of these means is migration. Vulnerability could also be explained as a lack of entitlements to things like food, security, sustainable livelihoods and social structures, owing to institutional, political, technological and other constraints (Sen, 1984).

Livelihood Assets and Capital

The idea of assets is central to the sustainable livelihoods approach. This is because people's abilities to convert these assets into positive livelihood outcomes demonstrates their resilience to risk and shocks (Ellis, 2000). Therefore, the sustainable livelihood framework identifies five types of assets or capital upon which livelihoods are built. These five sets of assets include: human, social, physical, financial and natural capital (Ellis, 2000). These assets are the stock of endowments that people possess in order to make a living. In the context of this paper, capital or assets form part of migrants' stock of assets that can aid them in their survival in their destinations area. For example, social capital refers to the connections migrants have with individuals, family members, friends, networks and other associations available to them in both destination and origin areas. Financial capital means savings, credit and debt (formal and informal), remittances, pensions and wages owed by migrants, while human assets or capital refer to the accumulated skills and knowledge of migrants. The term 'capital' also includes migrants' health, nutrition, education, capacity to work and capacity to adapt to the environment. The natural assets refer to land and, space, while physical assets imply the energy and physical worth of migrants. These assets are all very important building blocks for livelihood strategies and outcomes. They are described as the stocks of capital, used either directly or indirectly, to generate a means of survival or growth (Carney & Ashley, 1999; Department for International Development, 2000).

Migrants move from north to south with some form of assets (social, financial, physical, natural and human capital). These assets are the building blocks upon which migrants are able to undertake productive activities in their destination areas (Ellis, 2000; Carney, 2002). The natural assets include the spaces or land available to migrants in destination areas and the physical assets include all items that migrants acquired in their destination areas or brought with them from their origin communities, which aided their livelihood activities in the destination area. Based on those assets, and shaped by the vulnerability context and the transforming structures and processes or institutional constraints, migrants are able to undertake a range of livelihood strategies and choices that ultimately influence their livelihood outcomes (Department for International Development, 2000).

Institutional Constraints

Livelihood strategies and outcomes are not just dependent on access to capital and assets, or constrained by the vulnerability context; they are also influenced by the institutions that operate within the given environment. These institutions effectively influence access to the various types of capitals and to livelihood strategies (Department for International Development, 2000). Contextually, as migrants find their way to the city centre in Agbogbloshie in the south industrial area of Accra, specifically to trade, institutional structures and processes act on them, which either improve or worsen the livelihood outcomes of these migrants. City authorities, with a host of by-laws to regulate market activities, constitute the institutional structures and processes with which migrant traders have to contend as they engage in their livelihood activities at Agbogbloshie.

Livelihood Strategies

Livelihood strategies comprise the range and combination of activities and choices that people make, or undertake, in order to achieve their livelihood goals. They relate to the individual's available and implemented options for pursuing livelihood goals (Department for International Development, 2000). Livelihood strategies for these migrants emerge as a result of institutional structures and processes instituted by those in authority. These could include compliance, lobbying and establishing relationships with institutions to enable them engage in their livelihood activities without coercion (Department for International Development, 2000). Therefore, migrant traders adopt different strategies in order to overcome these institutional constraints, in order to make a living in the destination area. For instance, petty trading is a strategy adopted by migrants in order to survive or sustain themselves in destination areas. The constant moving around market places, soliciting for prospective customers, by migrant traders is another strategy to keep these institutional constraints in check for them. Livelihood strategies are directly dependent on assets, status and policies, institutions and processes. The main aim of livelihood strategies is to achieve full or partial livelihood outcomes.

Livelihood Outcomes

Potential livelihood outcomes can include more income, increased well-being, reduced vulnerability, improved food security and more sustainable usage of the natural resource base (Carney, 2002). Livelihood outcomes are the achievements or outputs of livelihood strategies, such as more income, increased well-being and reduced vulnerability (Department for International Development, 2000). Therefore, the livelihood outcomes of these migrant traders depends on the extent to which they are able to survive in the midst of the institutional constraints, and how they are able to maximise their assets. Generally speaking, if people have better access to assets, they have more ability to influence structures and processes, so that these become more responsive to their needs (Carney, 2002).

Methodology

Study area

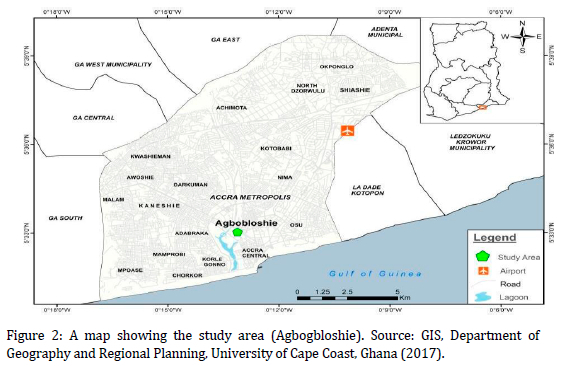

Agbogbloshie, an urban suburb predominantly occupied by migrant traders, is the study area. The area covers approximately four acres and is situated on the banks of the Korle Lagoon, northeast of the Central Business District of Accra, Ghana (Accra Metropolitan Assembly, 2015). It is estimated that about 79,684 Ghanaians inhabit the area (Accra Metropolitan Assembly, 2015). The area is mostly known for its trading activities, scrap dealers and e-waste dumping ground (Afenah, 2010). It is one of the busiest informal suburbs in Accra (Afenah, 2010). The structures of the market are mostly made of wood. The area has been categorised into three zones: Zone One includes the Nzema Market and the Dagonba Lane; Zone Two is the Konkomba Yam Market and Zone Three comprises the Cargo Station (Accra Metropolitan Assembly, 2015). Below is a map of the study area.

Target Population, Sample and Sampling Techniques

The target population for this particular study of the South Industrial Area in Accra (Agbogbloshie) constituted migrant traders from the three regions north of the country who were 18 years and older. This distribution of people from the three regions of the north, in Accra, confirms the presence of migrant traders (Northern region, 93,677; Upper East region, 40,809 and Upper West region, 16,489) (Ghana Statistical Service, 2012). These people are engaged in all kinds of activities for their livelihoods in Accra, including trading. It is also estimated that about 79,684 Ghanaians inhabit the Agbogbloshie area (Accra Metropolitan Assembly, 2015). From these figures, it can be deduced that some inhabitants in the area (Agbogbloshie) are from the three regions of the north. This is further supported by the existence of names like the Dagomba Lane and the Konkomba Yam Market as trading zones in the area.

Accessing the total population of northern traders in the area was difficult, since such data did not exist in the population census; and even though associations exist for traders of various goods, it was difficult to identify which traders were from northern Ghana. Therefore, migrant traders were identified through non-probability sampling techniques. These included snowball, convenient and purposive sampling techniques. First, a snowball sampling technique was employed, where one migrant trader helped the researcher to identify other migrant traders. Second, convenient sampling was employed to identify migrant traders. In using this method the researcher with his research assistant were stationed at certain vantage points in the market and seized the opportunity to interview migrant traders. This was done by using a common language (Hausa) and enquiring as to the origin of traders, if they were of northern origin, and whether or not they were prepared to answer questions. This research was carried out through a research assistant; a man who was fluent in the Hausa language and thus was able to interview the respondents. This method was both easy and inexpensive, and it helped to reduce the time that was spent collecting data. Furthermore, through such purposive sampling, other migrant traders were similarly identified. This was particularly the case for the in-depth interviews with key participants. Using these sampling techniques, a total of 100 respondents were sampled and interviewed.

Methods

The paper adopted a mixed methods approach to data collection. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected. The use of mixed methods offered the opportunity to address all issues in the research without bias and to make up for the inherent weaknesses that one method may have had over the other. The two methods of data collection used were structured and in-depth interviews. Structured interviews were administered on a face-to-face basis using an interview schedule. The use of this method for data collection allowed for common language to be used; given that the literacy status of respondents was low. The common language employed was Hausa since it is a common language spoken in the northern parts of Ghana. Therefore, the researcher, through the research assistant, conducted interviews that were recorded. This voice recording was later transcribed into English for analysis and interpretation. Additionally, an in-depth interview technique was necessary to gain an in-depth knowledge about the problems of migrant traders at the South Industrial Area in Accra. The in-depth interviews were targeted at six key participants who were purposefully selected and interviewed by means of this method.

The quantitative data was analysed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Version 21, where responses were entered and an analysis was generated. This included frequencies, percentages and a table. On the other hand, the qualitative data was analysed manually by transcribing recorded information and useful themes generated from the transcripts. These were used to support the quantitative data. Direct quotations were also used to place emphasis where necessary.

Results and Discussions

Introduction

To help illuminate the subject matter of this paper, it is important to discuss migrants' demographic variables of age, gender, marital status, religious affiliation and ethnic origin. This is followed by a discussion of the factors that influenced the migrants' north-south migration. In addition, the nature of migrants' livelihood activities or strategies is discussed in detail in this section.

The section concludes with an explanation of the problems experienced by migrant traders.

Demographic Characteristics of Migrants

Migrant traders exhibited different characteristics in terms of age, gender, marital status, religious affiliation, ethnic origin, region of origin, number of years spent in the destination region and number of children or dependants. Most of the migrant traders were youthful (18-27 years), with more than half of them being males (56%) and more than a quarter of them females (44%). 69% of them were between ages 18-27 years, with a 28-32year age group constituting 17% of the sample. The smallest age group among migrant traders consisted of those who were 40 years and above. They constituted 14% of the sample. Additionally, more than half (59%) were married at the time of the research, with the rest either being single (17%), in consensual union (17%), widowed (4%) or divorced (3%). Married migrants also confirmed that they had children, with the majority (76%) having 1-6 children and 7% of migrants having more than 7 children.

In terms of the region of origin, it was observed that more than half (70%) of migrant traders were from the northern region, less than a quarter (23%) from the Upper East region and only 7% from the Upper West region. These migrants were primarily Christians (54%) and Muslims (43%), with 3% being traditionalist. Migrants were dominated by three ethnic groups including the Konkonbas (34%), Dagombas (29%) and Frafras (24%). Other ethnic groups included Gonjas (8%) and Sisala (5%). Their duration of stay was long enough, as three quarters of migrant traders had been in Accra for 2-10 years. 17% had stayed longer than 10 years (11-15 years) and 3% had stayed in Accra for just under a year.

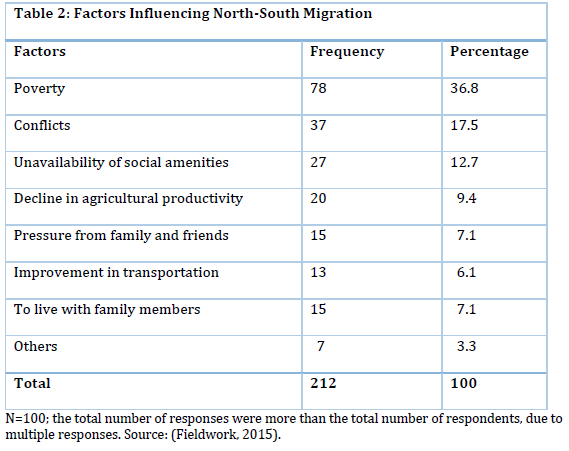

Factors that Influenced North-South Migration

Migration from the north to the south of Ghana could be due to several factors, however, with respect to this research. The key factors that induced migrant traders' north-south migration included poverty, conflicts, unavailability of social amenities and the decline in agricultural productivity (Table 2).

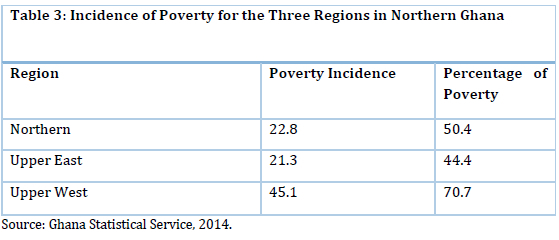

From the livelihood framework perspective, poverty put migrants in a vulnerability context. The three regions to the north of Ghana over the past decades have been recognised as some of the poorest regions in the country (Ghana Statistical Service, 2012; Participatory Poverty and Vulnerability Assessment Ghana, 2011). Poverty is also an indicator of underdevelopment, and the three regions of the north of Ghana lag behind other regions in terms of development (World Development Report, 2006; Kuu-ire, 2009; Van der Geest, 2011). In the face of poverty, sluggish development and declining agricultural productivity, many families in northern Ghana see migration as an investment to recoup some income in the form of remittances (Van der Geest, 2011; Kwankye, 2012b). The situation in the north, with its particular environment, colonial policies and lack of economic opportunities, partly explains the poor state of the region (Songsore, 2003; Kuu-ire, 2009; Anamzoya, 2010; Obeng-Odoom, 2012). Additionally, important factors such as unemployment, poverty, the need to acquire life's necessities, marital-related issues, the desire to invest, and protracted conflicts have been cited as reasons behind north-south migration streams in Ghana (Awumbila et al., 2011; Participatory Poverty and Vulnerability Assessment Ghana, 2011). The state of poverty is further explained from a cursory look at the poverty statistics for 2012/2013 shown in Table 3.

Besides poverty, a factor that exposed migrants to vulnerability was conflict. The northern sector of the country plays host to a number of violent conflicts that bring in their wake insecurity and general destruction. According to Kendie et al. (2014), 105 ethnic related conflicts can be identified in Ghana and it is argued that most of these conflicts occurred in the three regions in the north of Ghana. In a compilation of violent conflicts in Ghana, about 30 related intra- and inter-ethnic conflicts were recorded in the country; and the three regions of the north were involved in a total of 15 out of the 30 conflicts (Mahama, 2003; M'bowura, 2014). These conflicts negate prospects of peace and security in the area and this forces people to migrate to areas where there is relative peace; hence the migrant traders' presence in Accra. Some migrant traders explained how conflict had orchestrated their migration to Accra. This was what a 33 year old male trader had to say about conflict:

I left Bimbila to Accra because of the persistent conflicts in Bimbila; conflicts stalls many activities from progressing and a continuous stay in Bimbila with my family will hinder my children's dream of furthering their education - hence my presence here in Agbogbloshie, Accra (33 year old male trader).

Persistent conflicts in northern Ghana have compelled many families to abandon their home regions and move to urban centers like Accra, where there is relative peace and tranquillity. Van der Geest (2011) has acknowledged the crucial role of ethnic conflict in the out-migration phenomenon from the northern to the southern parts of Ghana. But more importantly, conflict exposes these migrants to risks and stress. Therefore, within that vulnerability context, the route to a livelihood is to migrate to Accra. A 45 year old male trader noted:

I was a student back in the northern region (Yendi) when the Dagomba and Konkomba war occurred in 1994. In the process our house was burnt down and other properties destroyed. This made me to move from Yendi to Accra where I thought I could do some business save money and continue my education. But due to several reasons iI could not continue my education and am still in thisyam trading business (45 year old male trader interviewed).

Conflicts push people into vulnerable situations and thus compel many to migrate to areas where there is safety. The migrants' exposure to vulnerability was enormous, as unavailability of social amenities further exacerbated their plight, occasioning their migration to Accra. This was not surprising because north-south migration is also spurred by factors such as inadequate infrastructure, unemployment and inadequate social services (Yeboah, 2008; Alenoma, 2013). A 22 year old male trader epitomises the situation in this narrative:

Lack of social amenities in the Nanumba North district has made me to move from there to Accra. There are no amenities like schools, hospitals and recreational facilities. I chose Accra because of the availability of social amenities (22 year old male trader interviewed).

Furthermore, 20% of respondents also revealed that decline in agricultural productivity in their home regions had made them leave their home destinations for Accra. Declining agricultural productivity compelled many families in northern Ghana to accept out-migration to southern Ghana, as an alternative means of reducing risk and vulnerability (Van der Geest, 2011; Kwankye, 2012b). Other factors that pushed people from the north to the south included pressure from family and friends to migrate to 'greener pastures' (7.1% percent), to seek improvement in transportation networks (6.1%) and the presence of relatives in Accra (7.1%). Some people migrated to towns and urban areas because they followed their spouses and relatives, while others migrated because of the presence of their relatives and friends in destination areas (Owuor, 2006). A 35 year old male trader remarked the following in relation to the presence of relatives in destination areas prompting an out-migration:

You know in my culture we have strong belief in extended family. Most of my family members have stayed in Accra since 1999 and I migrated to Accra because of my family relatives especially my uncle who takes care of me (35 year old male trader).

In sum, the factors that influenced the migration of traders to Accra, within the livelihood framework, can be described as the vulnerability context in which migrants found themselves. This is because these factors were considered external to migrants, hence their inability to control them. These imposed shocks and stresses on them. Therefore, migrants within this context opted for out-migration to Agbogbloshie as a way to escape these risks and stresses over which they had little or no control. Nonetheless, in their migration, they carried with them their assets or capital which could enable them to engage in a livelihood strategy for survival. Hence, the livelihood strategies of migrants explain the ability of migrants to put into use their livelihoods assets.

Livelihood Strategies of Migrants at Agbogbloshie in the South Industrial Area of Accra

A cardinal objective of this paper was to provide a vivid description of the livelihood activities or strategies of migrant traders at Agbogbloshie, Accra, within the framework of the sustainable livelihood approach. Migrants' presence in Agbogbloshie was occasioned by their 'vulnerability context' in northern Ghana, which can be attributed to poverty, conflicts and decline in agricultural and environmental factors. Such factors caused migrants' out-migration to Accra (Timalsina, 2000; Anamzoya, 2010; Awumbila et al., 2011; Imoro, 2011). It was, therefore, worthwhile to explore the livelihood activities or strategies of migrants, since these were people who did not have predetermined jobs in the destination area before their in-migration; and given their low level of skills, it was expected that livelihood activities would be diverse and cut across various spectrums of life survival mechanisms. Livelihood strategies comprise of the range and combination of activities and choices that people undertake in order to achieve their livelihood goals. This means that livelihood activities of migrant traders in destination areas embody a range of activities in which migrants are engaged for their survival (Carney, 1998; Scoones, 2009). Migrants making use of their livelihood assets, such as their physical, human and financial resources, were mostly engaged in trading of consumable and non-consumable goods, such as yams, tomatoes, grains and used products such as bicycles and motorbikes. Physical and human assets were vigorously utilised by migrant traders, as they were generally found around main roads, paths, kiosks, open spaces, bars and shops competing for prospective customers for their products. Revenue from these activities was the primary source of income for migrants in destination areas.

Admittedly, the nature of the work in which these migrant traders were engaged required physical strength. Essentially, traders operated as hawkers, carrying goods such as yams on their shoulders and moving around the market space seeking prospective buyers. Some hawked in between cars on pavements and on the main roads, attracting prospective buyers in that way. Trading activities among migrants at Agbogbloshie can be described as solely the preserve of the strong, since most of the trading activities require some degree of energy. Migrants would normally 'hustle' from one job to the other; in most cases the jobs involved exerting much physical energy in order to earn as much as possible in a day (Adaawen & Owosu, 2013).

Problems of Migrant Traders at Agbobgloshie in the South Industrial Area of Accra

As migrants hustled in their day-to-day activities, trading all kinds of consumable and non-consumables, they were bound to face problems. Some of these problems included inadequate market stalls and theft of wares (25.3%), lack of credit to expand their businesses (24.4%), harassment by city authorities (10.6%), discrimination against migrants (5.6%) and exploitation by market leaders (3.6%). These problems within the broader context of a livelihood framework also constitute institutional constraints that migrants face. These constraints determine the success, or failure, of migrants' livelihood outcomes in destination areas.

The struggle of migrant traders to maintain and sustain a livelihood strategy at Agbogbloshie included an attempt to navigate institutional constraints within the livelihood framework. Credit to migrants in destination areas is crucial for the running of businesses and livelihoods in general. Therefore, where migrants cannot get credit to stimulate the growth of their businesses, it creates problems for their survival and livelihood outcomes (Barr, 2004; Okojie et al., 2010; Eboreime, 2008). Lack of collateral and the inability of migrants to provide banks with guarantors, as well as improper locations and identifications, make it difficult for migrants to access credit from formal institutions such as banks (Awumbila et al., 2014). This is what a 35 year old male trader had to say:

My problem as a trader is money. The money I have now is not enough to buy more mobile phones and because of that I cannot bring every phone here and people are asking for phones. My money is not enough to go and bring a lot of phones. I manage the little I have. Interest rates from the banks are high and I have ever been to a bank and they said I should bring collateral. I need capital to enable me expand my business and bring more mobile phones (35year old male trader).

Inadequate market stalls and theft of wares (25.3%) were other nagging problems that migrants faced. Theft was a common phenomenon reported by migrant traders. Given the nature of the market area where shops do not have proper security, as well as the open nature of the market, one cannot guarantee security of personal belongings; hence stealing becomes the order of the day. The goods and wares of these migrants were often heavy and could not be conveyed back home to their places of abode after close of work. Thus, they were compelled to keep wares in places that lacked proper security; hence the persistent stealing. A 35 year old male trader explained his problem:

I have lived in Agbogbloshie for five years. I trade in yams for a living; as a trader I have encountered several problems like accommodation, inadequate funds and other personal problems, but the most serious problem I have faced as a yam trader is frequent stealing of yams and I incur losses (35 year old male trader).

This situation is further exacerbated by the inadequate number of stalls available for traders, including migrant traders. Admittedly, the area is not a well-constructed market with stalls and sheds in which traders can feel comfortable to go about their daily businesses. It is an open market where traders have to grapple with open spaces, having no shelves or stores to arrange their wares. Therefore, the few market stalls that are available are often rented out at exorbitant prices, which migrant traders are often unable to afford. Hence, it becomes daily drudgery for traders, as some have to contend with bare floors on which to display their wares, including consumables, for prospective buyers. The situation is lamented by a 25 year old male trader as follows:

A serious problem that I face as a migrant trader here in Agbogbloshie is the cost of rent for my shop. It is just too much for me to pay! So the little profit I get from the sale of mobile phones is being used for rent. This money should have been used to expand the business. I think when I work hard I can overcome some of these problems (25 year old male trader).

Their daily market activities are also regularly hampered by the harassment of city authorities. Harassment by city authorities took the form of chasing, seizure of wares and instant charges imposed by city guards on traders in the market. Due to the unstructured nature of activities in the market, the only way city authorities raised revenue was through the collection of tolls from these traders, and since the market was in an open space, which makes it difficult to regulate the entry and exit of both traders and the general public, city guards who collected tolls for the city authorities harass traders without toll receipts. This created problems for traders, particularly where traders may not have been issued with receipts. The inhumane manner in which city guards harassed traders, including migrant traders, called for concern. It could sometimes take the form of physically heckling traders out of the market, or even hitting traders with batons; leading to the use of a popular term among traders - 'abaayefo' - meaning, the people with sticks or canes. In other cases, traders' wares were seized or destroyed in order to punish traders for non-compliance. This generally created uneasiness and discomfort among traders and migrant traders alike. This is a common phenomenon in most open markets places within the African setting; city guards in a bid to enforce bylaws by city authorities, turn to harassment and sometimes exploit traders (Asiedu & Agyei-Mensah, 2008).

Migrant traders' problems were further compounded by the exploitation that they undergo at the hands of their market leaders. Loose market associations exist and leaders of these associations take advantage of their positions to exploit traders, including migrant traders. Apart from the tolls that migrant traders pay to city authorities, they also pay fees to market associations such the Yam Traders Association and the Tomatoes Sellers Association, among others. Hence, unscrupulous market leaders take advantage of this and exploit traders by charging them more money; particularly where traders defaulted in their payments for some days. In addition, these market leaders seized some products from traders, including migrant traders. The worst of these conditions was lamented by this 45 year old male yam trader.

When a truck of yam comes to the market before the trucks enters the inner perimeter of the market to discharge the tubers of yam, each truck is charged 10 GHS as entry fee; after the yams have been discharged, counted, and packaged for sale by traders, market leaders take 2 Ghana cedi each and one tuber of yam from every one hundred and ten (110) tubers of yam bundled for sale and this is pure exploitation we quarrel with them but what do we do (45 year old yam trader).

Exploitation of migrants in destination areas can take several forms and the experiences of these migrants constitute one way that migrants are exploited in their destinations. Stella (2012) identified labour exploitation, physical abuse and personal illness, among others, as problems that confronted migrants in their destination areas. Beyond the exploitation that migrants experienced in the destination area, discrimination was also inherently present in the discourse of problems faced by migrant traders. Migrant traders at Agbogbloshie were usually discriminated against, sometimes by city guards and other times by their market leaders. City guards treated them differently from other traders and called them names, such as 'pepeni' or 'tarni', among others. These are names used to refer to people mostly from the northern part of Ghana. Market leaders also offered preferential treatment to other traders, as compared to migrant traders. This was done by exempting other traders from paying fees and enforcing fees on migrant traders.

The myriad of problems with which migrant traders are confronted test their abilities to devise successful livelihood outcomes. This is because livelihood outcomes depend on the success, or otherwise, of livelihood strategies, and in this situation the livelihood strategies of migrants are constantly being hampered by nagging problems. The extent to which migrants can sustain a livelihood outcome therefore diminishes with the persistence of these problems. However, migrants traders showed resilience and knew that their livelihood depended on how they were able to confront these problems. It was indicated by 79% of the migrants that their primary source of livelihood was dependent on the sale of consumable and non-consumable goods, while admitting that they do extra jobs (moonlighting) to supplement their daily activities in the marketplace at Agbogbloshie.

Conclusion and Recommendations

It can be established that north-south migration still persists, particularly among the youth, given that the majority of migrant traders were between the ages of 18 and 27. Key drivers of the north-south migration included poverty, conflicts and unavailability of social amenities. More importantly, destination areas presented a complex mix of livelihood survival strategies and mechanisms for migrants; and, therefore, the success of the migrants depended on their abilities to navigate these problems. Problems such as lack of access to credit or loans, harassment by city authorities, the problem of stealing of wares, among others, can only be surmounted if migrants can first form cooperative unions or societies that would enable them to seek financial support from financial institutions. Second, it would present migrants with one voice with which to dialogue with city authorities on the problems they face, since they also contribute in terms of revenue and productivity to the economy of the area. On the part of the government, NGOs and other policymakers, cooperative unions or societies are recommended for the establishment of a market complex that would serve both migrant and nonmigrant traders, as the market is presently in a deplorable state.

References

Abdul-Korah, G.B. 2008. "KaBiε Ba Yor": Labour migration among the Dagaaba of the Upper West Region of Ghana, 1936-1957. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 17 (1): 1-19. [ Links ]

Accra Metropolitan Assembly. 2015. Feasibility study for Accra metro waste transfer stations Republic of Ghana: Accra Metropolitan Assembly.

Adaawen, S.A. & Owusu, B. 2013. North-South Migration and Remittances in Ghana African. Review of Economics and Finance, 5(1): 1-17. [ Links ]

Afenah, A. 2010. Re-claiming Citizenship Rights in Accra: Community Mobilization against the illegal Forced Eviction of Residents in the Old Fadama Settlement. In Habitat International Coalition. 2010. Cities for All: Proposals and Experiences towards the Right to the City. From <ugspace.ug.edu.gh> [Retrieved 27 July 2017].

Akter, T. 2015. Migration and living conditions in urban slums: implications for food security. From <www.unnayan.org> [Retrieved on 27 September, 2017].

Asiedu, A.B. & Agyei-Mensah, S. 2008. Traders on the run: Activities of street vendors in the Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 62(3): 191-202. [ Links ]

Alenoma, G. 2013. Rural-Urban migration in Nadowli District of the Upper West Region Ghana: A curse or Blessing to the Aged? Journal of Arts and Social Sciences, 1(2): 148-169. [ Links ]

Anamzoya, A.S. 2010. Chieftaincy Conflicts in Northern Ghana: The Case of the Bimbilla Skin Succession Dispute. University of Ghana Inter-Faculty Journal, 12: 41-68. From <http://bit.ly/2sBlFWV> [Retrieved 29 July 2017]. [ Links ]

Awumbila, M. & Ardayfio S.E. 2008. Gendered Poverty, Migration and Livelihood Strategies of Female Porters in Accra, Ghana. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 62(3):171-179. [ Links ]

Awumbila, M., Alhassan, O., Badasu, D.M., Antwi Bosiakoh, T. & Dankyi, K.E. 2011. Socio-cultural Dimensions of Migration in Ghana. Centre for Migration Studies Technical Paper Series, No. 3.

Awumbila, M., Owusu, G. & Teye, J.K. 2014. Can Rural-Urban Migration into slums reduce poverty? Evidence from Ghana. Migrating Out of Poverty Research Project Working Paper No.13.

Awumbila, M. 2015. Women Moving Within Borders: Gender and Internal Migration dynamics in Ghana. Ghana Journal of Geography Vol. 7(2), 2015 pp 132-145. [ Links ]

Awumbila, Mariama, Darkwah, Akosua, and Teye, Joseph. K. (2015). Migration, Intra- Household Dynamics and Youth Aspirations. Unpublished Paper. Migrating out of Poverty, University of Sussex.

Barr, M. S. 2004, Banking the Poor. Yale Journal on Regulation 21 (1): 121-237. [ Links ]

Carney, D. & Ashley, C. 1999. Livelihood Approaches Compared: A Brief Comparison of the Livelihoods Approaches of the UK Department for International Development (DFID), CARE, Oxfam and the UNDP. A Brief Review of the Fundamental Principles behind the Sustainable Livelihood Approach of Donor Agencies. Livelihoods Connect. London: DFID.

Carney, D. 1998. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: What Contributions Can We Make? London: Department for International Development. [ Links ]

Carney, D. 2002. Sustainable Livelihoods Approaches: Progress and Possibilities for Change. London: Department for International Development (DFID). [ Links ]

Chambers, R. 1983. Rural development: putting the last first. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Chambers, R. and G. Conway. 1992. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century". IDS discussion paper, 296. Brighton: IDS. [ Links ]

Chambers, R. 1995. "Poverty and livelihoods: whose reality counts"?. ID discussion paper, 347. Brighton: IDS. [ Links ]

Department for International Development (DFID). 2000. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. From <www.livelihoods.org> [Retrieved 10 January 2017].

Eboreime, I. M. 2008, Environmental and Socio-Economic Issues in the Niger Delta: A Comparative Perception Analysis of Selected Oil Multinationals. Journal of Applied Economics, 1 (1):7-23. [ Links ]

Ellis, F. 2000. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Ghana Statistical Service. 2012. 2010 Population and Housing Census: Summary of Final Report. Accra: Ghana Publishers. [ Links ]

Ghana Statistical Services. 2014. Ghana Living Standards Survey 6. Accra: Ghana Publishers. [ Links ]

Imoro, R.J. 2011. The migration of teachers from the Upper West Region. Legon Journal of Sociology, 4(2): 27-57. [ Links ]

Kendie, S.B., Osei-Kufour, P. & Boakye, K.A. 2014. Spatial Analysis of Violent Conflicts inGhana: 2007-2013. University of Cape Coast: University of Cape Coast Printing Press.

Kuu-ire, S.M.A. 2009. Poverty reduction in northern Ghana: A review of colonial and post-independence development strategies. Ghana Journal of Development Studies. 6(1): 175-203. [ Links ]

Kwankye, S.O. 2012a. Independent north-south child migration as a parental investment in northern Ghana. Population, Space and Place, 18(5): 535-550. [ Links ]

Kwankye, S.O. 2012b. Transition into adulthood: Experiences of return independent child migrants in northern Ghana. Omnes The Journal of Multicultural Society, 3(1): 1-24. [ Links ]

Mahama, I. 2003. Ethnic conflicts in Northern Ghana. Tamale: Cyber Systems. [ Links ]

M'bowura, C. K. 2014, The British Colonial Factor in Inter-Ethnic Conflicts in Contemporary Northern Ghana: The Case of the Nawuri-Gonja Conflict. The International Journal of Humanities and Social Studies, 2 (5):270-278. [ Links ]

Obeng-Odoom, F. (2012). 'Neoliberalism and the Urban Economy in Ghana', Urban Employment, Inequality, and Poverty. Growth and Change, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 85-109. [ Links ]

Okojie, C., Monye-Emina, A., Eghafona, K., Osaghae, G., & Ehiakhamen, J. O. 2010. Institutional environment and access to microfinance by self-employed women in the rural areas of Edo State. Washington. DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. NSSP Brief No. 14. From <http://bit.ly/2jnWYJc> [Retrieved 31 July ,2017]. [ Links ]

Owuor, S.O. 2006. Bridging the Urban-Rural Divide: Multi-Spatial Livelihoods in Nakuru Town, Kenya. Leiden: African Studies Centre, Netherlands. [ Links ]

Participatory Poverty and Vulnerability Assessment Ghana. 2011. Understanding the Regional Dynamics of Poverty with Particular Focus on Ghana's Northern, Upper East and Upper West Region. UK: Department for International Development. From <http://bit.ly/2C8Mkyl> [Retrieved 31 July, 2017].

Plange, N.K. 1979. Underdevelopment in Northern Ghana: Natural Causes or Colonial Capitalism Review of African Political Economy 6(15): 4-14. [ Links ]

Samsu-deen, Z., 2015 Migration and Health among Female Porters (kayayei) in Accra, Ghana. Unpublished Dissertation, submitted to the University of Ghana, Legon in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Award of a Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Migration Studies.

Scoones, I.1998. Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. IDS Working Paper No. 72. Inst. Dev. Studies, Sussex, UK.

Scoones, I. 2009. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1):1-26. [ Links ]

Sen, A. 1984, Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 32 (4):881-886. [ Links ]

Songsore, J. 1983. Intraregional and Interregional Labour Migrations in Historical Perspectives: The Case of North Western Ghana. Port Harcourt: University of Port Harcourt. [ Links ]

Songsore, J. 2003. Regional Development in Ghana: The Theory and the Reality. Accra: Woeli Publishing Services. [ Links ]

Stella, P.G. 2012. The Philippines and Return Migration. Rapid Appraisal of the Return and Re-integration Policies and Service Delivery. International Labour Office, ILO Country Office for the Philippines.

Tanle, A. 2003. Rural-Urban Migration of Females from the Wa District to Kumasi and Accra. A Case Study of the Kayayei Phenomenon. Unpublished M.Phil. Thesis. Presented to the Department of Geography and Tourism, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast. [ Links ]

Tanle, A. 2010. Livelihood Status of Migrants from the Northern Savannah Zone Resident in the Obuasi and Techiman Municipalities. Ph.D. Thesis. Submitted to the Department of Population and Health, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana. [ Links ]

Timalsina, K.P. 2000. Rural Urban Migration and Livelihood in the Informal Sector: A Study of Street Vendors of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, Nepal. Unpublished MPhil. Thesis Department of Geography Norwegian University of Science and Technology. [ Links ]

United Nations Development Programme, 2012. Africa Human Development Report 2012. Towards a food Secure Future. United Nations publications: New York.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2016. International Migration Report 2015: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/375).

United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (2012)

Van der Geest, K. 2011. North-South Migration in Ghana: What Role for the Environment? Oxford UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

World Development Report. 2009. Equity and Development: World Development Report 2006 Background Papers. From <http://bit.ly/2oa9rzO> [Retrieved 27 December, 2017].

Yeboah, M.A. 2008. Gender and Livelihoods: Mapping the Economic Strategies of Porters in Accra Ghana. Unpublished Doctor of Philosophy Thesis. West Virginia University. [ Links ]