Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.3 Cape Town 2017

ARTICLES

Post-Migration Outcomes and the Decision to Return: Processes and Consequences

Mary Boatemaa Setrana

Centre for Migration Studies University of Ghana. Email: mbsetrana@ug.edu.gh/ mobkjowat@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the decision-making processes of return migrants, especially since the 2001 introduction of government programmes to encourage the return of skilled migrants who have the capacity to contribute their quota to the development agenda of Ghana. Structured questionnaires were used to gather information on the migration trajectories of 120 return migrants. This was followed by interviews that primarily sought in-depth understanding of the decision-making processes of the return migrants. The findings indicate that these migrants were motivated by, among other factors, the availability of investment opportunities in Ghana, completion of education abroad, loss of jobs abroad, the decision to join family, feeling homesick and difficulty in integrating abroad. The paper recommends that home country governments should develop conducive policies appropriate for addressing the needs of the categories of returnees based on their decisions for coming home and how their skills and resources could be channelled into development.

Keywords: Return migration, voluntary and involuntary return, Ghana, motivation.

Introduction

International migration is a complex global issue that affects every country in the world. As noted by Ghosh (2000: 4), "international migration is essentially a multidimensional phenomenon [because] it defies a unisectoral approach." The magnitude of population movement on a global scale is increasing rapidly. The number of migrants who live in a country other than the one in which they were born has more than doubled from 191 million in 2005 (International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2005; United Nations, 2006) to 232 million in 2013 (OECD and UNDESA, 2013) and 244 million in 2015 (UNDESA, 2016). The occurrence of mass migration, including both regular and irregular movements, coupled with the growing complexity of migration systems, led Lidgard (1992: 12) to argue that "current immigration theories do little to explain the life span of these movements or predict future migrations." Thus, it is not surprising when other researchers, such as Ghosh (2000), suggest that we need a new comprehensive, coherent and internationally harmonised regime to manage international migration and, in this situation, return migration.

In recent times, African governments have been positively strategising to reverse the brain drain into a brain gain for the development of Africa (Tonah & Setrana, 2017). Since 2001, various governments have introduced programmes to encourage the return of skilled migrants who have the capacity to contribute their quota to the development agenda of Ghana. However, in Ghana, only a handful of researchers have dealt with certain aspects of return migration. Some have assessed the effect of migration experience on return and development in the countries of origin (Anarfi et al., 2005; Black & King, 2004; Black, King & Tiemoko, 2003; Setrana & Tonah, 2016), while others have examined the extent to which return migration contributes to the development of the home country. Still others have considered the effects of return migration on the migrant networks (Anarfi et al. 2010; Grant, 2009) and have highlighted the challenges associated with return migration (Setrana & Tonah, 2014; Setrana, 2017; Taylor, 2009). Among this limited number of studies, there are few studies (Wong 2013) that explore the post-migration outcomes and return decisions for development.

This paper contributes to the knowledge on return migration by providing an in-depth understanding of the return decision and analysing, comparatively, the migration and return decisions for development. First, the paper reviews the literature on why migrants return. This is followed by a presentation of the research methods, the characteristics of the return migrants and an analysis of the motives for return. This paper sums up with conclusions and recommendations.

Theoretical Perspectives on Return Migration

The process of return migration is usually conceptualised under four main theoretical perspectives, namely the Transnational Approach, the Structural Approach, the Neoclassical Migration Models (NE) and the New Economics of Labour Migration (NELM).

Transnationalism explains migration beyond the unidirectional movement of migrants to emphasise the frequent interaction between the home and host countries through the use of advanced technology (Glick Schiller et al., 1992).

Some scholars have argued that these constant contacts (known as transnational activities) between host and home countries may serve as preparatory strategies for the migrants' eventual return (Cassarino, 2004). However, this theory is inappropriate for this study because it endorses circular rather than return migration. It views migrants as individuals who may not return to their country of origin or to their parents' birthplace and therefore does not explain the potential factors driving their return.

Structural theories highlight the significance of contextual factors in the return process. They argue that no matter the resources acquired by the migrant, upon return, the political, economic and social factors have an impact on the productiveness of these resources in the home country (Diatta & Mbow, 1999; Thomas-Hope, 1999; Cassarino, 2004). These home country factors have an impact on migrants' decisions to return. Once again, this theory was not extensively employed because it pays little attention to how migration experience, particularly in the destination country, influences return decisions.

Both the NE and NELM theories emphasise economic factors as the reasons for migration. While the NE perceives wage differentials between origin and destination countries as reasons for migration (Massey et al., 1998), the NELM explains migrants' departure from the home country as a strategic plan with the aim of accumulating enough resources in the host country to then return to the home country (Galor & Stark, 1990; Stark, 1991). According to the NE, migrants may extend their stay in the host country because of higher wages (Borjas, 1989). However, if the migrant returns without any indication of higher wages in the home country, the return is seen as a failure. These two theories are limited in their explanations of the reasons for return; they only explain some economic factors, leaving out social factors such as family.

With respect to the limitations above, my study relies mainly on the 'push-pull' model of migration that was propounded by Lee (1966). According to Lee (1966), migration from one place to the other is reliant on factors existing in the home and host countries. The 'pull' factors are the favourable conditions that attract the migrant to a place, while the 'push' factors are the unfavourable conditions that drive migrants to a place. However, these factors were used by Lee (1966) to explain the movements of migrants from their countries of origin to their destination countries without linking this discussion to the issue of return migration. King (2000), in his study of return migration, applied these push and pull concepts, although he did not refer to Lee's model. Yet, these ideas are found relevant for this study in that they assist in explaining the reasons why Ghanaians return (either temporarily or permanently) to their home country after a period abroad. The study mainly relies on King's (2000) explanation of pull and push factors for return.

King (2000) identified individual, economic, political and social factors as both pull and push factors. The economic pull factors are higher wages and economic development, while the economic push factor is economic downturn in the country to which migrants had emigrated (King, 2000). The social push factors include difficulty integrating in the host country, loss of job opportunities and death of a spouse or parents in the host country (King, 2000). On the other hand, the social pull factors may include the privilege to enjoy prestige status once a migrant's status has improved, the desire to find a marriage partner, the decision to return to the home country after retirement, the need to raise children in the home country's culture, the need to care for the elderly and the need to be cared for by kinsfolk after retirement (King, 2000; Gmelch, 1980).

The push-pull model suggests that there are also intervening obstacles that slow down movement between the two areas (de Haas, 2010). Intervening obstacles may include issues such as instituted restrictive policies that prevent or result in a more cumbersome situation for families to reunite, change jobs, receive social protection and enjoy certain citizenship benefits (de Haas, 2010). Based on this analytical framework, the researcher examines the intersection between factors that push migrants from developed countries to Ghana and factors that pull migrants to return to Ghana. Despite the use of the push-pull model as the main theoretical framework, the researcher also relies on aspects of the other theories to explain some of the findings.

Research Methods and Data

The study employed a mixed methods approach that provided an opportunity for the researcher to combine quantitative and qualitative methods. Such a triangulation of methods was deemed appropriate in view of the strengths and weaknesses of the individual methods (Bryman, 2012; Cresswell, 2009). It also allowed for a better understanding of the problem than using either quantitative or qualitative methods alone (Creswell & Clark, 2007).

Like most African countries, Ghana has no universal registration of returnees on which to base a random sample. However, Anarfi et al. (2003) found that, overall, returnees largely mirrored national demographics; thus, an effort was made in this study to find a balanced sample with regards to age and sex. A representative ethnic mix was a more difficult task because of the diverse groups as well as the absence of records on the ethnicity of emigrants or returnees. The study also improved on the quality of data by purposively selecting four sites, namely Accra and Kumasi Metropolitan Areas and Dormaa/Berekum and New Juaben Municipal Areas. The international migration literature (Anarfi et al., 2000; Taylor, 2009) cites these locations as the established migration flow regions in Ghana. Accra and Kumasi Metropolitan Areas are more developed than Dormaa/Berekum and New Juaben Municipal Areas. These differences attract more international return migrants to the former two study areas than the latter two. However, the New Juaben Municipal Area is strategically positioned because it is closer to the capital city of Ghana (Accra), and international return migrants make choices to live close-by. Dormaa and Berekum were combined because the researcher experienced difficulty in finding international return migrants in Berekum. The decision on the field was to work in Berekum and Dormaa since these areas were not far from each other. Based on the outlined differences, the researcher assigned a quota of 28% and 22%, respectively, to the four study sites (Accra and Kumasi Metropolitan Areas, Dormaa/Berekum and New Juaben Municipal Areas).

The researcher used the snowball technique in identifying respondents, though this technique has some advantages and setbacks. In order to have as many diverse responses as possible, key informants with in-depth knowledge on the survey areas were recruited to assist the researcher in identifying returnees. In the first round of the survey, 14 returnees were selected. Through chain referrals by the 14 respondents in the first wave and personal contacts, the researcher obtained a second wave of respondents who, in turn, assisted in identifying further respondents for the study.

Out of the total number of respondents, 34 (28%) lived in Accra and Kumasi Metropolitan Areas and 26 (22%) lived in Dormaa/Berekum and New Juaben Municipal Areas. In all, the researcher interviewed 120 return migrants. The survey asked questions relating to the migrants' socio-economic circumstances before and after return. The survey instrument was pre-tested by ten international return migrants in the Greater Accra Region in order to help establish consistency and clarity of questions in the questionnaire. It was self-administered and the advantage was that all of the questions that were relevant to respondents were answered. At the end of the structured questionnaires, respondents were asked to give their consent by providing their contact details for further in-depth-interviews. Twenty-five of these respondents were selected based on their sex, age and mode of return. The qualitative information was a follow-up on the structured questionnaires and focused primarily on prior and post-return experiences.

Results and Discussion

Profile of Study Sample

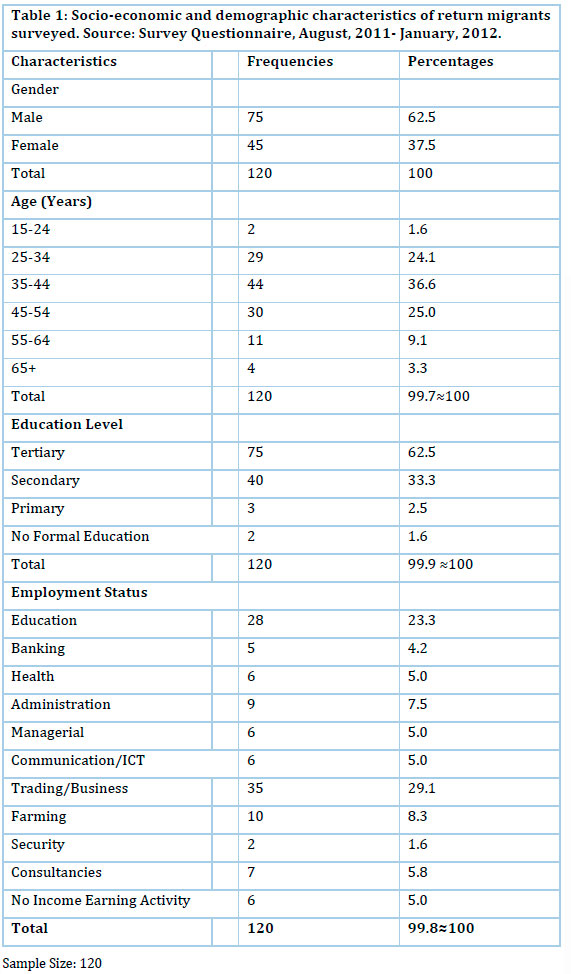

Most of the respondents were within working age; the average age was 42.40 years, with males dominating (63%). The educational level of return migrants was generally high, with 61% having either a university or diploma certificate. Out of the total 120 respondents, 54% either furthered their education or earned some kind of qualification or skills abroad. Respondents were found in all sectors of the Ghanaian labour market, with the majority (23%) of the skilled returnees working in the educational sector as lecturers, researchers and high school teachers. Other skilled returnees were involved in banking, administration, sales/marketing and health. This relates to the high unemployment situation in the country and the fact that recruitment of skilled personnel appears limited to the teaching and telecommunication sectors as well as some non-governmental organisations (Anarfi & Jagare, 2005). Most of the low or unskilled returnees were engaged in trading/businesses (29%), including mechanics, drivers, traders, masons, hairdressers and tailors. 8% are farmers, while 5% have no income earning activity; it must be stressed that included in the latter category were a student and a housewife (refer to Table 1). More than half (69%) of the respondents were married, while the rest were single (22%), separated or divorced (8%) and widowed (1%). About 87.5% returned voluntarily, while 10.8% were involuntary return migrants.

Migration History of the Return Migrants

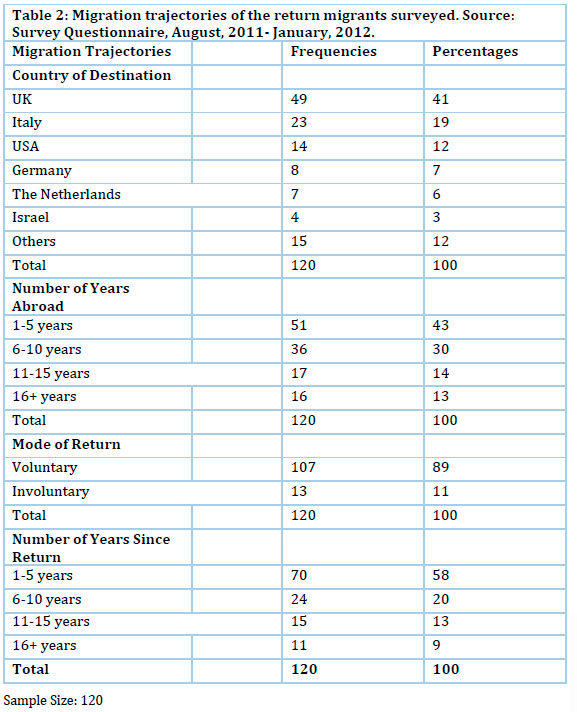

The return migrants had stayed in different countries in Europe and North America, with the majority coming from the United Kingdom (41%). This could be due to the common language and similar educational systems of Ghana and Britain (Ghana's former colonial master). The average time spent abroad was approximately 9 years, with a minimum of 1 year and a maximum of 44 years.

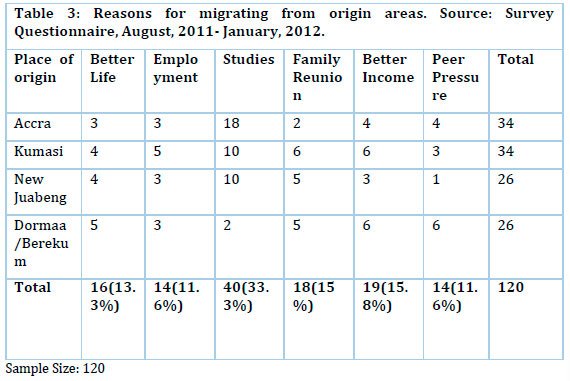

The most important reasons that motivated respondents to migrate out of Ghana were to find a better life (16, representing 13.3%), employment opportunities (14, representing 11.6%), studies (40, representing 33.3%), family reunion (18, representing 15%), better income (19, representing 15.8%) and peer pressure (14, representing 11.6%). The historical analysis of Ghanaian international migration shows that migration has been a means by which Ghanaians improve their human capital and better their living conditions (Anarfi et al., 2003; Awumbila et al., 2008). This finding is also evident among the respondents of this study, since many of them had aims to secure better living conditions, better income or pursue further education abroad.

Regional analysis of the data shows that the reasons for migrating from origin communities were diverse. Migrating for further studies was predominant among respondents who migrated from Accra, Kumasi and New Juabeng. This was followed by better incomes and family reunion, especially among respondents from Domaa/Berekum, Kumasi and New Juabeng.

Motivation for Return

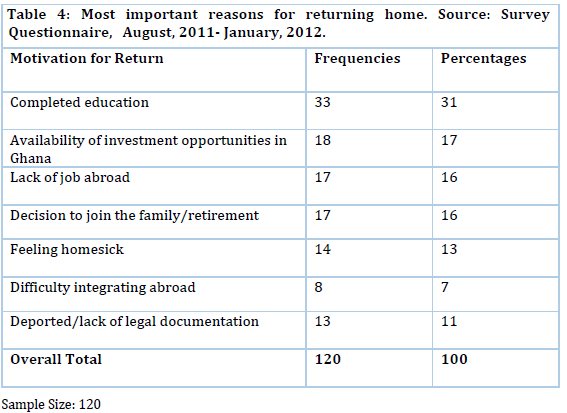

Respondents were asked to choose their most important motivations to return.

The most important reason for participants' return was completion of education in the host country. This was followed by the availability of investment opportunities in Ghana, the loss of employment abroad, the decision to join family in Ghana, homesickness and difficulty integrating abroad. The returned migrants expressed their emotions through statements such as "remember your home whenever you travel out of your home" and "home is home" (Fieldwork, August, 2011-January, 2012). Indeed, this finding confirms Manuh's (2001) description of "home is home" as a place of "quietness and rest." Some female return migrants found it necessary to come home with their husbands and children in order to save their marriages. Though she had completed her Master's degree programme, Nancy, the wife of Edmond, returned for the following reasons:

I came because my husband wanted me to come home with him. I thought about it. As a married woman I couldn't just abandon my children and husband like that. Who would take care of them? Had it not been that, I would have stayed in Germany. After all, the system is far, far better than Ghana's; our system is bad. I wonder! Anytime I visited, the differences were so obvious. Ghanaians don't follow or obey any laws (Nancy, interview in Accra, 9th November 2011).

Although Wong (2013) noted that females had power to make decisions that were not in favour of their male partners, this study presents a contrary situation. In Nancy's case, she preferred to live the rest of her life abroad; yet, she had to make a decision to come to Ghana to take care of her children and husband. In addition, families such as Nancy's who had children found it tiring and expensive raising the children abroad. However, families who left their children behind returned to Ghana to provide the best of care for their wards. The desire to spend more time with the nuclear family was noted as a crucial expectation of the return migrants. Spending more time with the family is central to ensuring a happy marriage and a unified family life. Such expectations of return are particularly ignited by the isolation that characterises migrants in the western world. It was observed that the western environment, with its secluding and secular lifestyle, was viewed by return migrants raising children as not conducive to the children's upbringing (Fieldwork, August, 2011-January, 2012). The respondents argued that though the host countries offered better facilities for their children's academic development than Ghana, the moral development of their children could not be guaranteed in such environments. The concern for the moral development of children is seen as a form of social investment. Alternatively, other return migrants with children were of the view that training children in Ghana was much more preferable than their country of destination because they wanted their children to imbibe Ghanaian values.

The retiree returnees said that they returned home because they were more likely to receive better care from their extended families in Ghana than abroad. They found solace and incentive in the reception and comfort that the elderly receive within the Ghanaian traditional system. Some respondents had quality care from extended families because of their age. This is to be expected if contact with kinsmen was frequent and contribution towards festivities was regular whilst abroad. Particularly in the matrilineal lineage, the caretaking of aged uncles and aunts by nieces and nephews is expected from diligent family members. In this situation, the intervening variable to receiving quality care upon return was linked to the returnees' contact with home while abroad (Lee, 1966). One of the respondents echoed these sentiments during the interviews, noting:

If for nothing at all, in Ghana, when I am here, my grandchildren and nephews are around [...] I can send them on errands anytime, ask them to fetch me water and cook for me, at least. Who will do this for me in Italy? I can only get help when I am admitted to the elderly home ('Teacher Burger', interview in Kumasi, 23rd January 2013).

Others also decided to return to Ghana to inherit leadership positions in their families and communities. For example, in Dormaa, there is a suburb called 'Burger Anane' Street. The return migrants in this community revealed that the area was named after a wealthy return migrant called 'Anane [the name of an Akan male]'. The title Burger was given to him by the community because, first, he had returned from abroad; second, he returned with "flashy goods" (visible wealth) and third, he had bought and settled on a large portion of land. Burger Anane was an accountant who left Ghana for Germany in 1990, with the aim of finding better living conditions for himself and his wife and children. Having earned enough money, he purchased this vast plot of land and the street named after him. In 2005, he returned to Ghana to start and manage his own businesses.

On the other hand, some respondents indicated that they returned to Ghana because they were divorced. In order to avoid the shame from the Ghanaian Diaspora community, some decided to return to Ghana where they could begin a new life. This finding is confirmed by Manuh (1998), who notes that Ghanaians abroad adhere to some cultural practices and behaviours such as the stigma of divorce.

The other factors that influenced migrants' return are political in nature, ranging from forced expulsion to incentives for voluntary return. All of the respondents who ticked political causes were deportees (13, representing 11%).

Characteristics Associated with Motives for Return

This section highlights some socio-demographic and migration characteristics related to migrants' reasons for return to their home countries. The main characteristics analysed include education, age, gender and number of years spent abroad.

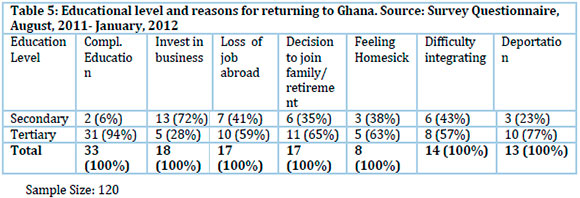

A large majority of the respondents with tertiary education returned with the motive of finding jobs in Ghana after completing their education abroad. Some of the respondents with tertiary education returned due to loss of employment abroad, while only a little below a third of respondents with tertiary education returned to invest in Ghana. However, the story is slightly different for respondents with investment opportunity motives. 72% of returnees with the motive of investing in Ghana had relatively low academic qualifications compared to their counterparts with other motives. On the other hand, more than half of the respondents who returned due to problems integrating abroad had tertiary rather than secondary education (37%). Among those who came to join their families, 65% had tertiary education, while more than half (57%) of those who returned due to feelings of homesickness had tertiary education. From the findings, it is evident that migrants' motives for finding jobs in the formal sector are influenced by their higher levels of education; but those who had the intention to access the investment opportunities of the home country may have realised that their lower levels of education were not competitive enough to secure them 'white collar' jobs. In this regard, they sought resources or means other than their educational backgrounds.

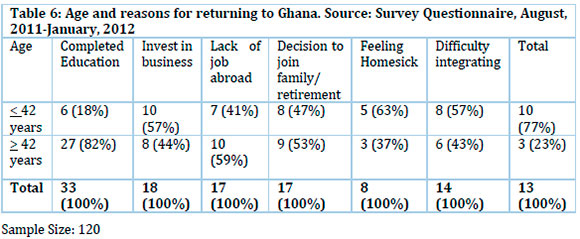

Table 6 presents the age categories of the returnees. The majority (82%) of the return migrants who were above the average age of 42 years had the motive of accessing job opportunities compared to their counterparts of the same age with investment (44%) and loss of job (34%) motives. Thus, return migrants are returning home at younger ages and are actively working. More than half (63%) of the returnees who were 42 years and below were motivated due to problems integrating abroad, while 57% of them returned due to homesickness. The finding confirms Anarfi et al.'s (2005) conclusion that more than half of Ghanaian return migrants are in the economically active age group of 30-49 years.

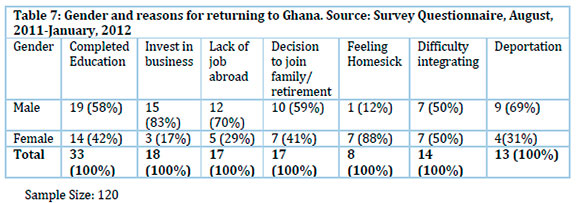

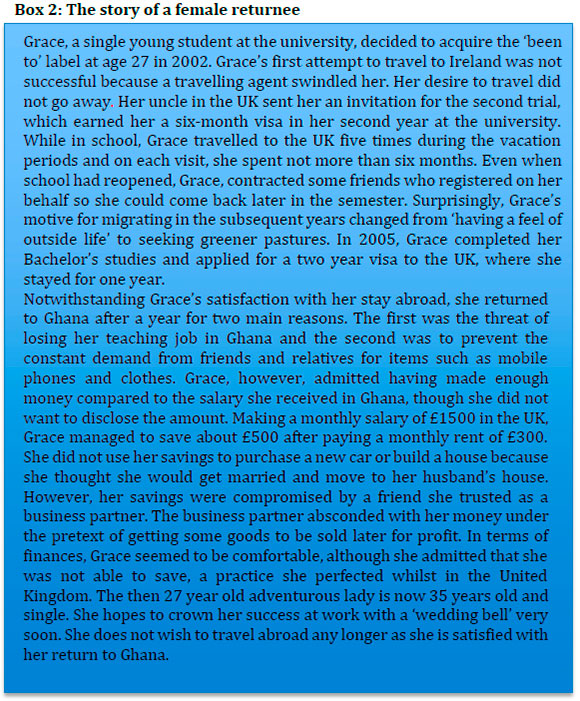

The proportion of males (83%) is higher among returnees who came home for investment opportunities (refer to Table 7). This is followed by 65% who returned due to loss of jobs abroad, while slightly more than half (55%) had the motive of accessing job opportunities in the home country (refer to Table 7). Indeed, the finding indicates that more male returnees than female returnees would make the decision to invest in the home country. For return migrants who had the intention to join their families, more than half (59%) of them were females and about 41% were males. The motive to join family at home is the only motive with more female representation than male representation. Additionally, 50% of the respondents that noted homesickness as their motivation were female. Implied in these statistics is the idea that return decisions such as problems integrating abroad, feelings of homesickness and joining family were not determined by the gender of the return migrant.

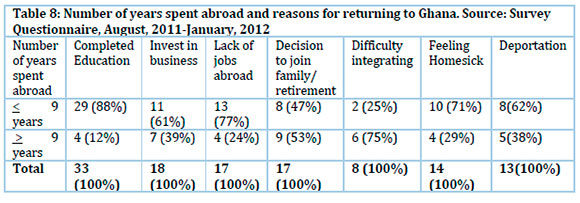

A higher proportion (88%) of returnees who had lived abroad for nine or fewer years returned for job opportunities in the home country; 77% returned due to loss of jobs abroad, while 61% came home for investment opportunities (refer to Table 7). For respondents who returned for job opportunities, the time spent abroad was crucial in their decision-making, particularly with regard to meeting their objectives for travelling. For instance, respondents who pursued further education had to do so within a limited time frame before deciding to come home for job opportunities. The majority (75%) of the returnees who had spent nine or more years came to Ghana due to problems of integration abroad, while the majority (71%) of those who had spent nine or fewer years abroad returned due to homesickness. These categories of returnees could not adjust to the cold weather, racism and other difficulties integrating after spending some time abroad.

This last paragraph presents some characteristics on the 13 (representing 11%) deportees. 9 out of the 13 deportees (69%) were males; 10 of them (77%) had tertiary education, while the remaining 3 (23%) had secondary education. Again, 10 out of the 13 (77%) were 42 years and below. The majority of these respondents were educated, economically active and could establish themselves in the home country if proper reintegration strategies were put in place.

Exploring the Possible Links between the 'Reasons for Migration' and the 'Reasons for Return'

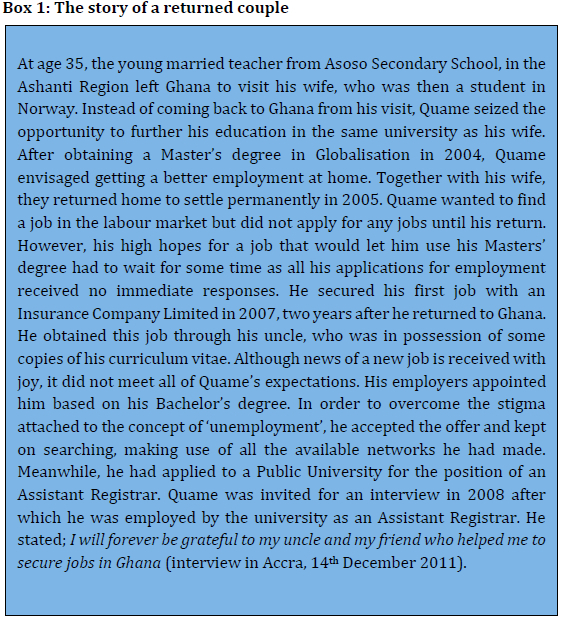

This segment outlines the most important reasons for departure from home and compares these reasons with the essential motives for return. In exploring the reasons for 'departing from' and 'returning to' Ghana, qualitatively, the data shows that migrants who migrated to pursue further studies returned because they had completed their education. These return migrants decided on their return at a time when they knew they had what was required for them to compete in the Ghanaian labour market. During the in-depth interviews, some respondents said that their frequent contact with 'home' made them discover that their classmates in Ghana had 'made it big' (secured lucrative jobs) with similar or even lower qualifications and, therefore, felt the need to return after the acquisition of similar qualifications (see Box 1).

For respondents who returned home due to investment opportunities in Ghana, it was observed that their main motive for moving abroad was to obtain "better living conditions." This finding supports the NELM view that following the original plans, return migrants would find it prudent to return home after accumulating resources abroad that could help them continue to achieve their "better lives" (Stark, 1991).

For respondents who returned home due to loss of job abroad, two main motives influenced their trips overseas, namely the pursuit of better living conditions and further studies. Some respondents expanded the description of loss of job to include temporary occupation, collapse of personal business or loss of job. Some of the respondents indicated that menial jobs were usually not permanent, while return migrants from Europe, especially those from Italy and the UK, said that they were laid off from their jobs. This finding supports the pull analysis that recent global economic crises have led to the closure of several industries in some parts of Europe. So, return is possible if migrants experience such conditions in the destination country. This finding does not support the proposition by the NE that return migrants would only return when they experience the loss of a job abroad and fail to achieve their intentions of having a better life or employment (Stark, 1991). It is more likely that respondents weighed the costs and benefits of return and realised that with their levels of education or accumulated capital, they could fare better in Ghana than abroad.

Among the respondents who returned home to join their families (for reasons such as retirement), the primary reason for migration out of Ghana was to better their lives. For respondents who returned home due to homesickness/retirement, their reasons for migrating included pursuing further studies, employment, better living conditions and family reunion. For respondents who came home because of the challenges associated with integration abroad, their initial migration was motivated by education. Indeed, the returnees had a well-defined plan prior to their migration that was influenced more by a social than an economic motive. Alternatively, this also reflects the strong attachment Ghanaians have to their extended and nuclear families.

The experiences that occurred during migration processes led to changes in the original migration intention. This finding confirms du Toit's (1990) statement that migration is a process instead of an act or static event. So, pre-migration intentions may not always match with real migration outcomes because many obstacles or opportunities may compel the migrants to adjust their initial plan. For this reason, the migrant may decide to explore better opportunities, move on to new goals or return to the point of departure with the same plan. The dynamic nature of migration experiences moves the argument beyond the 'calculated strategy' or 'set targets' based on economic factors as proposed by the NELM.

For many of the deported returnees, two main motives influenced their trips overseas. These were to further their studies abroad and the desire for better living conditions. Only one respondent took the risk of reaching Italy via the desert; all of the other respondents travelled with the correct documents, namely three months tourist visas, student visas or working visas. Respondents said that even after their documents had expired, they kept on with their normal duties until they were arrested. In these instances, the goal of the migration could not be achieved because of circumstances beyond the migrants' control.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Similar to previous studies (King, 2000), the decision to return by these groups of Ghanaian returnees was based on both social and economic factors, including available income, accumulated skills or capital, family circumstances in the home country, old age, retirement and the need for care. These social reasons could be explained by the structural approach to return migration, which stipulates that the family and home structures are influential in the return decision-making. Migrants' accumulated resources, be they skill or capital, are invested in job creation and this has multiple effects on the national economy. On the other hand, the social reasons, though prestigious, Setrana and Tonah (2016) conclude that they may pose challenges to these returnees as they attempt to satisfy their own expectations as well as the high expectations from the community and family. In between the push and pull factors, the study also identified intervening variables (such as migration experience factors, age, immigration policies, travel documentation, education and marriage), which changed the prior-migration decisions as well as the return decisions. This study supports the argument that migration is not a onetime event, but a process (du Toit, 1990) that is imbued with several opportunities and obstacles (de Haas, 2010) that can challenge pre-migration decisions and influence real migration outcomes.

Furthermore, the positive attractions such as job and investment opportunities in Ghana were dominant among these respondents in the return decision. This finding provides evidence that suggests that migrants are mostly returning for better opportunities in the home country and not only due to economic crisis or negative circumstances in the host countries, as suggested in the literature. Indeed, the structural approach to return explains that migrants who return home are attracted by the home country's political or economic conditions that enable them to utilise their acquired resources. Thus, they invest their financial resources into businesses or set up enterprises, which has a ripple effect on the economy of Ghana. Based on their profiles, some of these returnees are also working in the formal sector and are thereby using their knowledge acquired abroad for the improvement of some sectors of the economy.

The study, therefore, recommends that Ghana develop reintegration programmes for addressing the needs of the different categories of returnees based on their decisions for return and how their skills and resources could be channelled into development. The reintegration programmes should not only operate in the capital city but in all the regional capitals and districts of Ghana in order to serve return migrants who prefer to live outside of the capital towns.

References

Ammassari, S. 2004. From nation-building to entrepreneurship: The impact of Élite Return Migrants in Cöte d'Ivoire and Ghana. Population, Space and Place, 10(2):133-154. [ Links ]

Anarfi, J.K. Awusabo-Asare, K. and Nsowah-Nuamah, N. 2000. Push and Pull Factors of International Migration: Country Report Ghana. Working Paper No. 10, Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Anarfi, J.K., Kwankye, S. Ababio, O.M. and Tiemoko, R. 2003. Migration from and to Ghana: A Background Paper, Working Paper No. C4, Brighton: Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty, University of Sussex. [ Links ]

Anarfi, J., Quartey, P. and Agyei, J. 2010. Key Determinants of Migration among Health Professionals in Ghana. Sussex, UK: Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalization and Poverty, University of Sussex. [ Links ]

Anarfi, J.K. and Jagare, S. 2005. Towards the sustainable return of West African transnational migrants: What are the options? Paper presented at a conference on New Frontiers of Social Policy, Arusha, December 12-15, 2005.

Anarfi, .J.K., Kwankye, S. and Ahiadeke, C. 2005. Migration, return and impact in Ghana: A comparative study of skilled and unskilled transnational migrants. In: Manuh, T. (ed). At Home in the World? International Migration and Development in Contemporary Ghana and West Africa. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers. [ Links ]

Awumbila, M., Takyiwaa, M., Quartey, P., Tagoe, A.C. and Bosiakoh, A.T. 2008. Migration Country Paper: Ghana. Accra: Centre for Migration Research, University of Ghana. [ Links ]

Black, R. and King, R. 2004. Editorial introduction: Migration, return and development in West Africa, Population, Space and Place, 10(2): 75-83. [ Links ]

Black, K., King, R. and Tiemoko, R. 2003. Migration, Return and Small Enterprise Development in West Africa: A Route Away from Poverty? Sussex: Centre for Migration Research, University of Sussex. [ Links ]

Borjas, G.J. 1989. Economic theory and international migration, special silver anniversary issue: Evidence from Uganda 671 international migration an assessment for the 90s. International Migration Review, 23(3): 457-485. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods, 4th edition. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cassarino, J.P. 2004. Theorising return migration: A visited conceptual approach to return migrants. International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 6(2): 253-279. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, Sage, London.

Creswell, J.W. and Plano Clark, V.L. 2007. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Diatta, M.A. and Mbow, N. 1999. Releasing the development potential of return migration: The case of Senegal. International Migration, 37(1): 243-266. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2010. Migration and development: A theoretical perspective. International Migration Review, 44(1): 1-38. [ Links ]

Du Toit, B.M. 1990. People on the Move. Rural-urban migration with special reference to the third world: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Human Organisation, 49(4): 305-319. [ Links ]

Galor, O. and Stark, O. 1990. Migrants' savings, the probability of return migration and migrants' performance. International Economic Review, 31(2): 463-467. [ Links ]

Ghosh, B. (ed.). 2000. Return Migration: Journey of Hope or Despair? Geneva: International Organisation for Migration and United Nations. [ Links ]

Glick-Schiller, N., Basch, L. and Blanc, C.S. 1992. Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration. In: Glick Schiller, N., Basch, L. and Blanc, C.S. (eds). Toward a Transnational Perspective on Migration: Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Nationalism Reconsidered. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, pp.1-24. [ Links ]

Gmelch, G. 1980. Return migration. Annual Review of Anthropology, 9(1): 135-140. [ Links ]

Grant, R. 2009. Globalizing City: The Urban and Economic Transformation of Accra, Ghana. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. [ Links ]

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2005. World Migration: Costs and Benefits of International Migration. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. [ Links ]

Jach, Regina 2005. Migration, Religion und Raum. Ghanaische Kirchen in Accra, Kumasi und Hamburg in Prozessen von Kontinuitaet und Kulturwandel. Lit Verlag, Muenster.

King, R. (ed.). 2000. Return Migration: Journey of Hope or Despair? Geneva: International Organisation for Migration and United Nations. [ Links ]

Lidgard, J.M. 1992. Return Migration of New Zealanders: A Rising Tide? MA Thesis (Unpublished), Hamilton, New Zealand: University of Waikato. [ Links ]

Lee, E. 1966. A theory of migration. Demography, 3(1): 47-57. [ Links ]

Manuh, T. 1998. Ghanaians, Ghanaian Canadians, and Asantes: Citizenship and identity among migrants in Toronto. Africa Today, 45(3-4): 481-494. [ Links ]

Manuh, T. 2001. Diasporas, unities and the marketplace: Tracing changes in Ghanaian fashion. Journal of African Studies, 16(1):13-19. [ Links ]

Massey, D.S., et al. 1998. Worlds in Motion: International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Nieswand, Boris. 2011. Theorising Transnational Migration: The Status Paradox of Migration, Routeldge, United Kingdom.

Setrana, M.B. and Tonah, S. 2014. Return migrants and the challenge of reintegration: The case of returnees to Kumasi, Ghana. A Journal of African Migration, 7: 116-142. [ Links ]

Setrana, M.B. 2017. Back Home at Last: Factors affecting reintegration of Ghanaian Return Migrants. Journal of Identity and Migration Studies, 11(1):27-195. [ Links ]

Setrana, M.B. and Tonah, S. 2016. Do transnational links matter? Labour market participation of Ghanaian return migrants. Journal of Development Studies, 52(4):549-560. [ Links ]

Stark, O. 1991. The Migration of Labour. MA Thesis (Published), Cambridge: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

Taylor, L. 2009. Return Migrants in Ghana. London, UK: Institute for Public Policy Research. [ Links ]

Thomas-Hope, E. 1999. Return migration to Jamaica and its development potential. International Migration, 37(1):183-207. [ Links ]

Tonah, S. and Setrana, M.B. 2017. Introduction: Migration and Development in Africa: Trends, Challenges and Policy Implications. In Tonah, S., Setrana, M.B. and Arthur, J. (eds). Migration and Development in Africa: Trends, Challenges, and Policy Implications, Maryland, USA: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

UNDESA. 2013. Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2013 Revision. New York: Population Division, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. [ Links ]

United Nations, 2006, International Migration and Development, United Nations General Assembly, 60th Session, Agenda item 54(c) A/60/871. From: <http://bit.ly/2CpeAIy> [Retrieved August 22, 2012].

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). 2016. Trends in International Migration Stock: Migrants by Destination and Origin 2015.

OECD-UNDESA. 2013. World Migration in Figures. From: <http://bit.ly/2CouUt6 >

Wong, M. 2013. Navigating return: The gendered geographies of skilled return migration to Ghana. Global Networks, 14: 438-457. From: <http://bit.ly/2o3pgIA> [ Links ]