Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.2 Cape Town 2017

ARTICLES

Informal Entrepreneurship and Cross-Border Trade between Mozambique and South Africa

Abel ChikandaI; Ines RaimundoII

IDepartment of Geography & Atmospheric Science, African & African-American Studies, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas State, USA 66045. Email address: achikanda@ku.edu

IIFaculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, Mozambique

ABSTRACT

Informal cross-border trading is an essential part of Maputo's informal economy. This paper presents the results of a 2014 SAMP survey of informal entrepreneurs involved in cross-border trade between Johannesburg and Maputo. A questionnaire was administered to a sample of 403 informal traders in 7 markets in Maputo. The study showed that most of the entrepreneurs began their business activities as vendors and only later moved into cross-border trading. The overwhelming majority used their personal savings to start their business and they face significant barriers in accessing business loans from formal banking channels. The study demonstrates the importance of cross-border traders to both the Mozambican and South African economy. In South Africa, the cross-border traders make a significant contribution by buying local goods and utilising the services provided by the country's travel and hospitality industry. In Mozambique, they supply affordable products to the country's growing informal sector and play an important role in generating employment.

Keywords: Cross-border traders, informal economy, informal sector, migration, South Africa.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the Mozambican economy has experienced GDP growth rates above 6% (ADB, 2016). This has made Mozambique the fastest growing non-oil economy in Sub-Saharan Africa (Nucifora & da Silva, 2011). However, there has been limited formal employment generation (Jones & Tarp, 2013). Most of the country's urban working population is still in the informal economy (Jenkins, 2013) and nearly two-thirds of the economically active population in Maputo City is involved in the informal economy in some way (Jenkins, 2012). A 2007 survey found that 70% of households were involved in informal economic activities, with a significantly higher participation rate by female-headed (86%) than male-headed (62%) households (Paulo et al., 2007). Maputo's informal economy is firmly integrated into the national and local economies of neighbouring states such as Mozambique and Swaziland and the primary mechanism of integration is informal cross-border trade or ICBT.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, female ICBT traders became important players in the Mozambican economy, particularly in the supply of food as well as non-agricultural products such as electrical goods and building materials (Macamo, 1999). A SAMP border monitoring study in Mozambique in 20062007 showed that women made up 71% of the total number of cross-border traders (Peberdy et al., 2015). A significant feature of the post-2000 crossborder trade from Mozambique was its diversity. A number of Mozambican traders (36.5%) said they also traded between Swaziland and Mozambique, buying goods in Swaziland to sell in Maputo (Peberdy, 2000a). Those travelling to South Africa to buy goods for resale tended to gravitate towards Johannesburg and Durban, while the rest travelled to towns in the neighbouring province of Mpumalanga (Peberdy, 2000b).

Among Mozambicans, the expressions dumba nengue (trust your feet) and dumba kutsutsuma (run if you can) are used to describe the informal economy (War on Want, 2006). This terminology clearly reflects the tension that exists between informal traders and law enforcement agents. Compared with other cities in the region, however, Maputo has traditionally adopted a more tolerant approach to the informal economy (Kamete & Lindell, 2010; Rogerson, 2016). Policy interventions aim to discourage informality through registration and formalisation rather than by eradication and punishment (Dibben et al., 2015). Two main strategies have been pursued by the municipal government. First, formal urban markets have been established, existing informal markets have been upgraded and vendors now pay rent for stands. When Xikhelene market was upgraded, for example, all trading on the streets around the old market was eliminated (Ulset, 2010). Second, a simplified tax system was introduced that requires traders to pay business tax either as a lump sum or as a percentage of turnover (Dibben et al., 2015). This initiative has been hampered by low uptake and strong resistance from the informal traders.

Informal trade is a major catalyst for involvement in informal economies globally (Desai, 2009). The ECA (2010: 143) has noted that "informal trade is as old as the informal economy. It is the main source of job creation in Africa, providing between 20 per cent and 75 per cent of total employment in most countries." Informal trade also plays a vital role in linking informal economies in different Southern African cities. This requires a perspective on informality that takes into account the impacts of interaction between different urban informal economies across the region (Akinboade, 2005). The volume of cross border trade has been monitored at the Mozambique and South Africa border in the past but this paper provides the opportunity to engage in an in-depth analysis of different types of cross-border trade and how ICBT is integrated into Maputo's informal economy (Dlela, 2006; Peberdy, 2007; Peberdy & Crush, 1998). There has been a tendency in the past to view informal traders as sole operators rather than micro-enterprises with the potential to grow significantly, to create jobs and to generate the capital to branch out into other sectors of the informal and formal economy. By viewing informal traders as entrepreneurs per se and their activities as a potentially strong promoter of growth and employment, we are in a position to move beyond the idea that ICBT traders are "survivalists" struggling to make ends meet, and rather towards an analysis of the potential for growing their businesses, the obstacles they face and the kinds of policy environment they require in order to realise their entrepreneurial ambitions (Lesser & Moisé-Leeman, 2009; Peberdy & Crush, 2001; Söderbaum, 2007).

Research Methodology

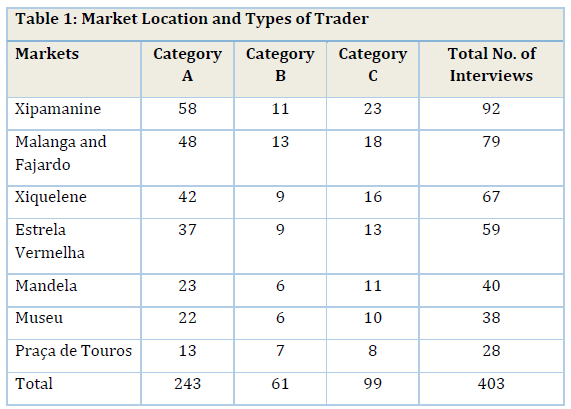

In the first phase of the research on which this paper is based, a survey questionnaire was administered to a sample of 403 informal traders in 7 Maputo markets. The sample was divided into 3 entrepreneurial categories (Table 1):

■ Category A: 243 Mozambican traders who travel to and from Johannesburg as part of their business, buying goods in South Africa and selling them in Maputo.

■ Category B: 61 Mozambican traders who travel to and from Johannesburg, buying goods in South Africa and supplying other informal traders in Maputo. These traders supply vendors in the markets and small shops.

■ Category C: 99 Mozambican informal traders who do not travel, but purchase goods from cross-border traders for resale.

In sum, 61% of the sample were cross-border traders who travel to and from South Africa as part of their business, 14% were trader intermediaries who travel to South Africa to buy goods and sell to other traders on return, and 29% did not cross international borders but obtained their goods from those who did.

The sampling procedure tried to capture the range of products sold in different markets as markets are getting more specialised, primarily because of their geographical location and potential customer base. Most customers who buy at Museu Market, for example, come from the relatively wealthy areas of Museu, Polana and Sommerschield, while people who buy at Xiquelene mainly come from poor wards. Foodstuffs are the primary product at Xiquelene, while Museu's main products are alcohol and cigarettes. Praca de Touros market is situated in one of the busiest areas of Maputo and mainly caters to vehicle owners who need spare parts and also has a car-repair garage. Estrela Vermelha market, also known as Red Star Shopping Centre, sells a variety of goods including household furniture, alcohol and cigarettes. This market is located between Central and Alto Mae wards, and suburbs such as Mafalala, and serves people in both middle- and low-income brackets.

Not all of the goods in the markets come from South Africa. In addition to locally sourced agricultural products, goods come from as far afield as Europe and South America. For instance, frozen chicken from Brazil is a common sight in many of the markets (de Oliveira et al., 2015). There is also a major trade in imported second-hand clothes. At the Xipamanine market in Maputo, for instance, hundreds of traders sell second-hand clothing from Australia, Europe and North America (Brooks, 2012, 2013; Ericsson & Brooks, 2014). Many of the clothes that reach Xipamanine are of low quality and, according to one researcher, neither improve the lives of the vendors nor the consumers, an outcome which he terms "clothing poverty" (Brooks, 2015).

In the second phase of the research, four focus group discussions were conducted with traders from the following markets: Xiquelene, Zimpeto, Malanga and Museu. Key informant interviews were also conducted with different government, private sector and international organisation stakeholders with an interest in the informal economy. Among the issues covered in the interviews were the history of cross-border trade in the country, the role of cross-border trade in economic development, legislation governing the informal economy and the challenges faced by cross-border traders.

Profile of ICBT Traders

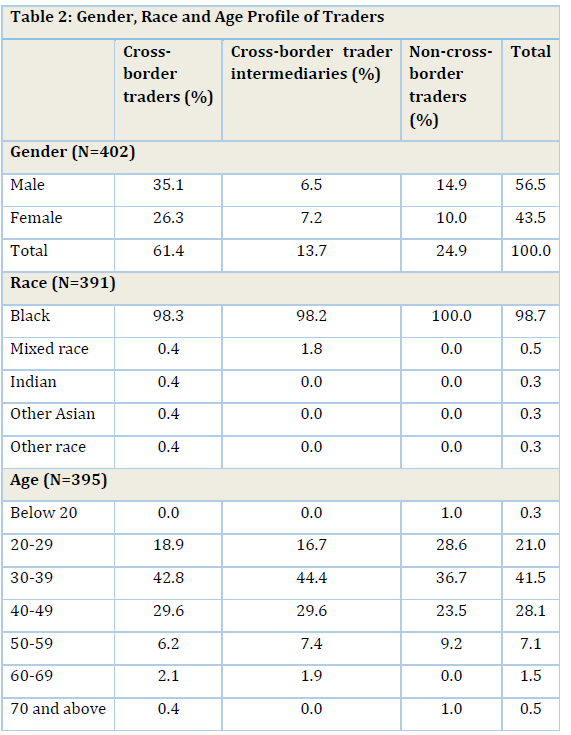

There is a general perception that cross-border trading in Mozambique is predominantly undertaken by women, while men tend to stay at home and sell products brought into the country by women (de Vletter & Polanda, 2001; Peberdy 2000a; Peberdy et al., 2015). However, some studies have shown greater participation of men in Mozambican informal cross-border trade over time (Macamo, 1999). In this study, 56% of those interviewed were men (Table 2). It is likely that the profile of the respondents would have weighted more heavily in favour of women if the study had been conducted at the border. Women tend to find it easier to be involved in cross-border trade and leave the marketing of the products to either their husbands or sons (Raimundo, 2010). The predominance of women in cross-border trade has been attributed to their long experience in crossing borders dating back to the early days of Mozambique's 16-year civil war; their business acumen; their familiarity with managers of wholesale storehouses in Johannesburg; and the fact that they find it more difficult than men to access formal employment (Raimundo, 2010). Male respondents claimed that females are better equipped to deal with customs officials and have strategies for avoiding paying import duties; that they themselves viewed trading as more of a hobby or a way to generate extra income; and that they have greater access to jobs in the formal sector.

Racially, the overwhelming majority of the respondents (99%) were Black, while a minority were of mixed race, Indian or Asian. The mean age of the sample was 37 years with 42% aged between 30 and 39 and 28% between 40 and 49. Around 10% were over the age of 50, and the oldest respondent was 78. Participation by young people in the trade was relatively limited with only 20% under the age of 30. Across all the categories, individuals aged between 20 and 49 made up more than 90% of the total participants.

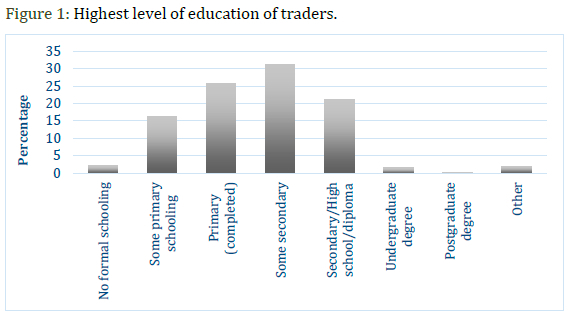

Involvement in the informal economy is usually associated with low levels of educational attainment (Amaral & Quintin, 2006; Wilson et al., 2006). As many as 75% of the respondents had less than high school qualifications, and fewer than 2% had completed an undergraduate degree (Figure 1). Interestingly, traders who do not travel to Johannesburg themselves but obtain goods from cross-border traders, had the highest level of education, with 28% having completed at least high school, compared to 22% of the cross-border traders who travel to Johannesburg as part of their business and 16% of the intermediaries who supply goods to non-cross-border traders in Maputo.

In understanding how household structure affects participation in the business of informal trade, marital status needs to be considered. For example, are the traders independent operators looking out for themselves? Are they heads of households that depend on them for a livelihood? Or are they just contributing to household income? Given that this business can require cross-border traders to be away from the household for several days at a time, there was an expectation that it might be dominated by single, widowed and divorced people. However, the survey found that only 29% were single (which tallies with the more mature age profile of the entrepreneurs) and 6% were divorced or widowed. Of the rest, 38% were married or in a common law relationship and a further 26% were co-habiting.

More than half of the respondents (52%) came from nuclear households (defined as a family made up of husband/male partner and wife/female partner with or without children). About 16% came from male-centred households, where there is no wife/female partner in the household and 13% were from female-centred households. Another 11% were from extended households, while only 7% lived alone. An AFSUN survey in Maputo in 2008/2009 showed that the majority of residents in the poorer areas of the city came from extended households, even though female-centred and nuclear households were also common (Raimundo et al., 2014). This seems to suggest variation in patterns of participation by type of household. In total, 66% of households are male-headed nuclear and extended family households. These households constitute 63% of the traders' households (although the reason why extended families are far less likely to participate than nuclear families is unclear). The major difference is in female-centred household participation where these households constitute 27% of all households but only supply 13% of traders, suggesting that these household heads are inhibited from participation because they cannot leave their children. Male-centred households appear not to have a problem, with 8% of the total number of households supplying 16% of the traders.

Business Start-Up and Ownership

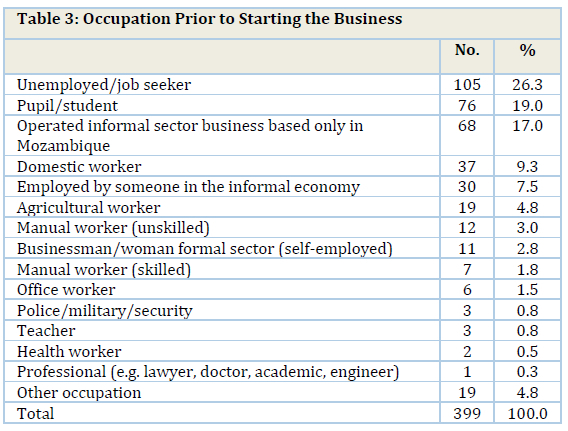

There is an assumption in the literature that many informal entrepreneurs are pushed into participation by unemployment (Jones & Tarp, 2013; Sparks & Barnett, 2010). However, only 26% of the respondents were unemployed before they started their business. Another 19% had been students (Table 3). Around 30% had been employed, primarily in low-paying jobs such as domestic work (9%), agriculture (5%) and unskilled manual labour (3%). Less than 5% had occupied skilled or semi-skilled positions. The rest were already employed (8%) or self-employed (17%) in the informal economy in another enterprise.

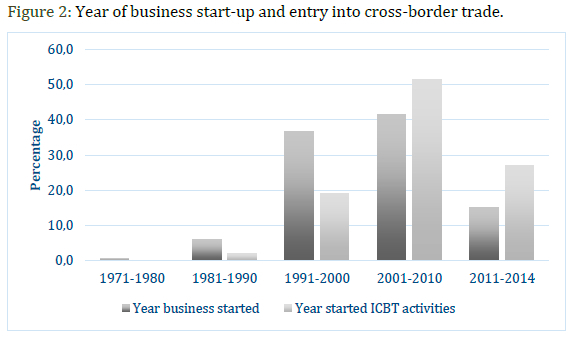

In contrast to ICBT traders from countries such as Zimbabwe, the majority of the Maputo City entrepreneurs had been involved in the informal economy for many years. As many as 43% had established informal businesses before 2000 and another 41% had done so between 2000 and 2010. Less than 20% had set up shop in the last five years, which may suggest that entry into a highly competitive business is becoming more difficult. The survey also showed that most of the entrepreneurs began their business activities as vendors and only later moved into cross-border trading. So, while over 40% had started their businesses before 2000, only 21% were engaged in ICBT at that time (Figure 2). Conversely, while 57% established their businesses after 2000, the proportion who started ICBT activities during this period was close to 80%. This indicates that most ICBT traders are post-2000 entrants to that market, a direct result of various economic factors and market opportunities. Factors of relevance include the devastating floods of 2000, which impacted many households; the lifting of South African visa restrictions in 2005; and the strengthening of the metical in comparison to the rand (Christie & Hanlon, 2001).

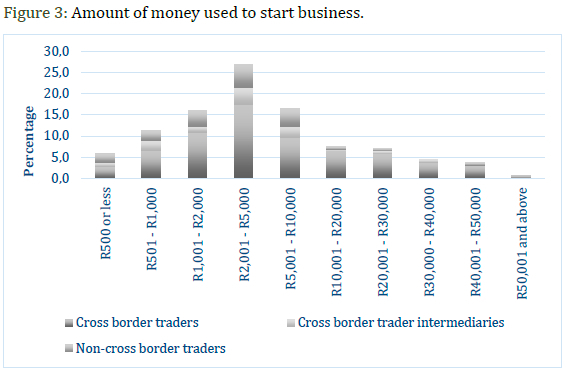

The overwhelming majority of the respondents started their businesses from a very low base with three-quarters having less than ZAR 10,000 (approximately USD850) to invest (Figure 3). Of these, the majority had between ZAR 2,001 and ZAR 5,000 (USD170-USD425). Just 15% had invested ZAR 20,000 (USD 1,700) or more. This group was most likely to be crossborder traders (83%) rather than cross-border intermediaries or non-crossborder traders. The non-cross-border traders tended to have the lowest levels of start-up capital with nearly 90% investing ZAR 10,000 or less in their businesses. The sources of capital used to start the business varied but the majority (82%) had used personal savings. Other sources of start-up business capital included loans from relatives (used by 33%), bank loans (9%) and loans from informal financial sources (8%). Access to formal sources of business capital was limited, constituting a general reflection of the lack of support given to informal enterprises by formal financial institutions.

One recent study showed that nearly 80% of Mozambicans have no access to any sort of banking or microfinance services (Finmark Trust, 2009). Only 12% of the sample had access to banking services; 10% to the informal microfinance sector and 1% to formal microfinance services. However, this study of informal entrepreneurs in Maputo found that although most could not get bank loans, as many as 44% had a bank account. Lack of access to business financing from formal sources is common among informal entrepreneurs. Benjamin and Mbaye (2012) have noted that informal entrepreneurs in Africa frequently fail to access business finance because of the onerous procedures required for loan applications as well as the collateral requirements. The situation is no different in Mozambique: 27% indicated that they cannot apply for bank loans because of the high interest rates and 24% do not have interest at all in applying for bank loans. In an effort to improve financial access to informal entrepreneurs, Moza Bank became the first private bank of Mozambique to give loans to informal traders through the ASSOTSI - Informal Cross-Border Trade Association. The loans are only available to ASSOTSI members who can present a reference from ASSOTSI and a simplified tax return. The loans may be up to one-third of the annual business turnover shown in the tax return, to a maximum loan of MZN100,000 (Baxter & Allwright, 2015).

The programme officer of the Competitiveness and Private Sector Development Project noted that several government funding schemes are available to small and medium-scale enterprises, but not to businesses in the informal economy:

The Government of Mozambique through the Ministry of Commerce and Industry has established the Enterprise Competitiveness and Private Sector Development Project, which funds small and middle enterprises for competitiveness. The State does not recognise unlicensed businesses which are run by cross-border traders. To be funded one needs to be licensed. The informal economy is not eligible for funds (Interview, 25 November 2015).

Just over one-third of the respondents were aware of the scheme but only 2% had applied, suggesting that they are aware of the ineligibility of informal enterprises for government assistance.

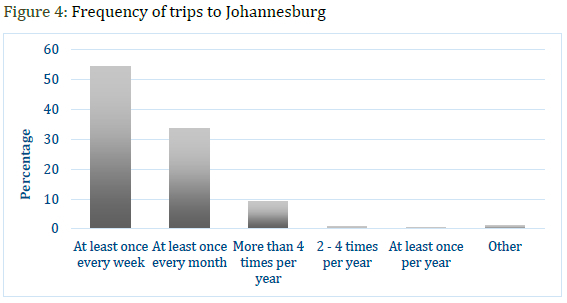

Business Strategies

The research sought to examine the ICBT linkages and flows between Maputo and Johannesburg. Johannesburg was the primary place, and beneficiary, of the purchase of goods by Mozambican traders. On average, the cross-border traders spend 1.52 days in South Africa on each trip. As many as 54% travel to Johannesburg at least once a week, which translates to nearly 80 days per year spent in South Africa. A further 34% travel there at least once a month, which translates to 18 days per year in South Africa (Figure 4). As many as 8% of the respondents indicated that they also buy goods in other places in Gauteng, such as Pretoria and Randfontein. More than one-third of the respondents purchased goods from other places in South Africa, especially from towns close to the Mozambican border such as Nelspruit, Malelane and Komatipoort. The traders are therefore able to conduct their business activities in South Africa and return to Mozambique within the same day. A small number of respondents (around 12%) also travel to other countries to conduct their business, including Swaziland, China and Dubai. As many as 27% of those who travel to these other countries for business are non-Mozambican nationals.

Most of the traders sell the goods from South Africa in Maputo, the capital, while a small number (less than 5%) also sell their goods in other cities such as Xai Xai and Beira. The goods are sold mainly in their own shops in the informal sector (38%) or in their own stalls in an informal market (24%). However, there is also evidence of informal-formal sector linkages with 9% selling in their own shops in the formal sector, 8% selling to retailers, 3% to wholesalers and 1% to restaurant owners.

A total of 424 other people were employed directly in the businesses interviewed (Figure 5). Around half (51%) provide employment to others, or an average of 2.1 jobs per business. A significant proportion of the traders employ more than one person: 27% of those providing employment had two employees, 10% had three employees and 5% had four or more employees. There was a major difference in the employment practices between those who travel to South Africa and those who do not (58% versus 31% providing jobs). This confirms that many cross-border traders prefer to focus on their crossborder activities and employ others to sell the goods on their behalf in Maputo. Non-family members made up 69% of the paid employees and the rest were family members, with a total of eight employees below the age of 18. Some 71% of the employees were men, confirming that there is an explicit focus on male employment in the businesses supported by ICBT. This seems to support our earlier observation that men prefer not to cross borders but are employed by women in the sale of goods in Mozambique.

The involvement of children in the informal economy is a controversial issue (ILO, 2004; Thorsen, 2012). Some regard their involvement as an essential part of household survival strategy (Becker, 2004). Others view it as child labour that limits the proper development of children and should therefore be eliminated (Burra, 2005). The survey found that 16% of enterprises involve children in their business in different capacities. Participation was higher among children of cross-border traders (20%) than non-cross-border traders (7%). Among those who involve their children, 53% said their children help them to sell goods, 43% sometimes ask their children to look after the stall and 5% involve them in other ways.

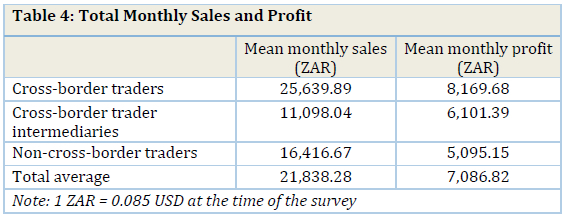

Participation in cross-border trading is sometimes viewed as a part-time activity to supplement income from other sources. The overwhelming majority of respondents (90%) have no other income-generating activity and rely solely on their ICBT-supported business for survival. Discussions of informal entrepreneurship have focused on whether the sector can create viable enterprises that can provide decent incomes to the participants (ILO, 2009; Sparks & Barnett, 2010). In other words, can cross-border traders generate incomes comparable to formal sector jobs? The traders generate an average of ZAR 21,838 per month (USD 1,850) in total sales and a profit of ZAR 7,087 per month (USD 600) (Table 4). Cross-border traders who travel to Johannesburg as part of their business activities are likely to generate more monthly sales and profit than non-cross-border traders or cross-border trader intermediaries.

Cross-border entrepreneurial activity is certainly financially beneficial to the participants. Nearly two-thirds (64%) said that their income status had increased compared to the period before they started their business and only 6% said it had decreased. Another 26% said that their income was variable, fluctuating according to market conditions. The greatest improvement was reported by the cross-border traders. The profits generated from informal business play an important role in meeting personal (79%) and family (77%) needs. One-quarter of respondents were investing the proceeds in education of family members, more than the proportion re-investing income in the business itself (only 19%). One-third said that profits were being saved for future use. Just under 10% send money outside of Mozambique as remittances either to support the needs of their family members or for investment in business.

Contributions to the South African Economy

Who benefits most in South Africa from the purchasing behaviour of Mozambican cross-border entrepreneurs? This section examines the activities of those cross-border traders who travel to South Africa and seeks to identify the South African beneficiaries of Mozambican ICBT (Peberdy et al., 2015). First, ICBT between South Africa and Mozambique contributes to South Africa's massive trade surplus by exporting South African goods and importing far less from Mozambique. Only 5% of the traders sell products from Mozambique in South Africa (including cigarettes, fabric/capulana, fresh fruit and vegetables and alcohol). Most of these products are sold through personal networks, but they are also sold to wholesalers and informal vendors.

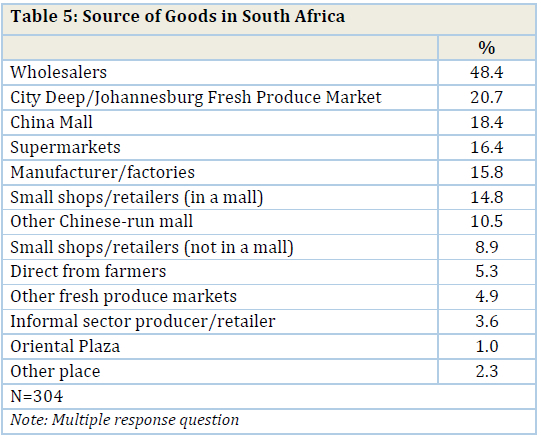

Second, a wide variety of outlets in South Africa benefit from patronage by Mozambican traders, including wholesalers, supermarkets, small retailers (formal and informal), factories, farms and fresh produce markets. Easily the most important beneficiaries of Mozambican patronage are South African wholesalers (used by 48%). Other important sources of goods for the traders include the Johannesburg Fresh Produce Market (21%), supermarkets (16%), manufacturers (16%) and small shops or retailers either in a mall (15%) or outside a mall (9%) (Table 5). Chinese shops are also popular with the crossborder traders, with 19% buying goods from the China Mall and 11% buying goods from other Chinese-run malls.

The goods bought in South Africa can be grouped into five main categories: food and beverages, household/home goods, personal goods, electrical goods and miscellaneous. In the first category of food and beverages, the most common items were cooking oil (purchased by 22% on their last visit), eggs (20%), alcohol (20%), mealie meal (18%) and fresh fruit and vegetables (18%). The most popular household/home goods were household products (26%) and bedding material such as blankets and duvets (8%). Personal goods were dominated by new clothing and footwear (19%), while electronics and cellphones and phone accessories were the most popular electrical goods bought in South Africa.

A third party benefitting from the presence of the Mozambican traders is the South African Treasury. Most of the prices that the traders pay for their goods include VAT, although VAT refunds can be claimed as these goods are not consumed within South Africa. VAT refunds ensure that the traders are not double taxed through paying VAT in South Africa and customs duty at the border. However, on their last trip to South Africa, only 55% of traders had claimed the VAT to which they were entitled. Of the 45% who did not claim VAT, nearly half said they did not know the procedure and 36% said that the procedure takes too long. In focus group discussions, it emerged that one of the reasons was that bus drivers did not want to spend time at the border while customs officials searched for goods. This makes it extremely difficult for the traders using public transport to submit VAT refund claims. Those using taxis or their own vehicles are more likely to claim VAT refunds. While it is advantageous for South Africa if people do not claim these refunds when they leave the country, it is fundamentally unfair to the traders. The Mozambican Government and civil society should certainly launch a campaign aimed at educating the cross-border traders on their rights and the procedures to claim VAT refunds. In addition, the Mozambican Government needs to work with its South African counterparts to clear the bureaucratic bottlenecks related to claiming VAT refunds.

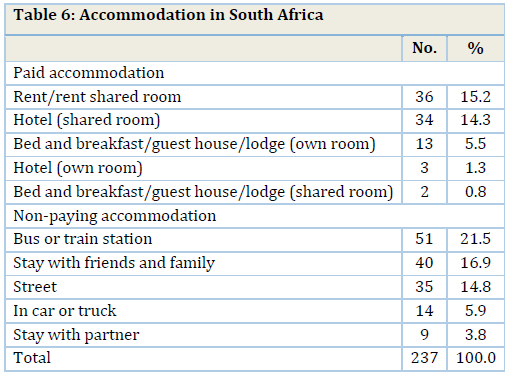

Fourth, ICBT traders spent money on transportation, accommodation and food when in South Africa. About 37% usually stay in paid accommodation, including rented rooms, hotels, guesthouses and B&Bs (Table 6). Those who do not pay for accommodation sleep at the bus or train station, on the street, in an automobile or stay with friends and family. Public transport is the most common way for traders to travel to and from Johannesburg, including buses (used by 43%), trucks (15%), taxis (11%) and trains (1%). Others use private transport including their own vehicles (13%), individually-rented vehicles (11%) and vehicles rented with others (6%), but still pay for petrol and other costs such as parking in South Africa.

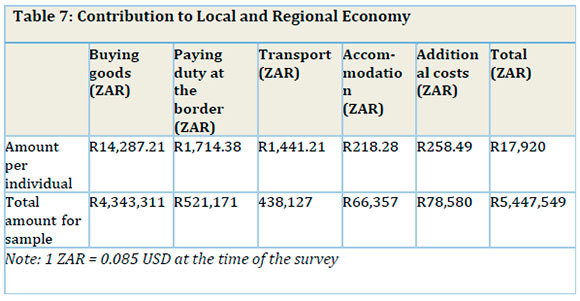

In terms of the monetary spend in South Africa, the cross-border traders reported spending an average of ZAR 14,287 on goods, ZAR 1,714 on customs duties, ZAR 1,441 on transport, ZAR 218 on accommodation and ZAR 258 on other expenses on their last trip to South Africa. In total, a trader travelling from Maputo to Johannesburg thus spent approximately ZAR 17,900 per trip on business-related costs. This translates to nearly ZAR 5.4 million per trip for the entire sample, most of which directly benefits the South African economy (Table 7). The financial contribution of cross-border traders to the South African economy is clearly significant.

Business Challenges

In general, the ICBT traders do not have problems with their documentation and immigration status when in South Africa. The introduction of the visa exemption for Mozambicans certainly played a significant role in reducing undocumented migration from Mozambique. Most significantly, only 2% travel to South Africa with no official documentation. As such, the vast maj ority of the Mozambican ICBT traders enter the country using legal channels.

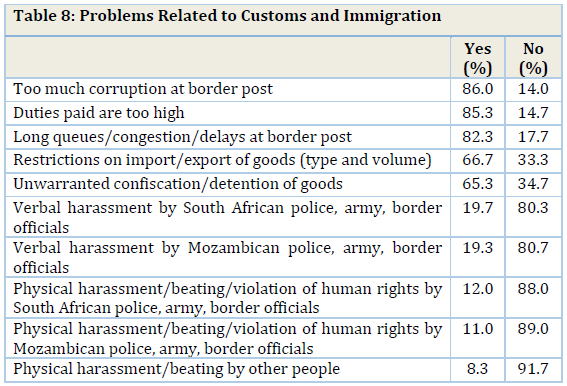

The most important border or customs-related problem cited by the crossborder traders was corruption, experienced often or sometimes by 86% of the respondents (Table 8). Corruption leads to a reduction in government customs revenue collection and may also result in a reduction of the profit margins of the cross-border traders, which ultimately reduces prospects for business expansion. Others claimed that the duties that they pay at the border are too high (85% often/sometimes), while long queues, congestion and delays at the border are experienced often/sometimes by 82% of the cross-border traders. Clearly, the cross-border traders are dissatisfied with the time it takes them to clear customs at the border and there is evidence to suggest that paying bribes can help speed up the process. Some of the study participants noted that they use the magaigai or intermediaries with experience in dealing with customs officials in an attempt to avoid paying the high duties.

Other respondents noted that they experience restrictions on the types and volumes of goods that they can either import or export (experienced often/sometimes by 67% of respondents). During the focus group discussions, one trader noted that "we can import spare vehicles, vegetables, groceries, fruit, meat, furniture, alcohol. The only limitation is related with duties and some do not know the Common Customs Tariff, which is a heavy book to be read." The Common Customs Tariff is composed of 97 categories of products and sub products. The president of the Mukhero Association commented on the Common Customs Tariff as follows:

Mukheristas get advice from the association about their rights and obligations and some were trained. All the time that the Government updates duties or other related issues the associations are informed. As a matter of fact, before any increase or changes on Common Customs Tariff, the Government calls the associations to inform them, otherwise we block the streets. When the Government of South Africa introduced a new regulation that every crosser should prove they had an amount of ZAR 3,000, we felt that was a decision that had to be discussed between the two governments. We were concerned about security and not every trader carries that amount of money. South African should understand that we bring money to them and we are no longer poor as it was in the past during civil war.1

Others cited the unwarranted confiscation/detention of goods at the border (56% often/sometimes). A focus group participant noted that they are sometimes forced to leave their goods at the border if they fail to reach a reasonable agreement with customs officials. Participants noted that it was not worthwhile trying to get goods back because of the high cost of import duty, especially on goods such as cigarettes and alcohol. The customs department is said to auction confiscated goods.

Even though only a small number of respondents reported cases of harassment and abuse, these are significant enough to warrant attention. Verbal harassment by police, army and border officials had been experienced often/sometimes by the cross-border traders on both the South African (16%) and Mozambican (16%) sides of the border. Physical harassment/beating/violation of human rights by police, army and border officials had also been experienced often/sometimes on both the South African (11%) and Mozambican (10%) sides of the border.

The president of the Mukhero Association described the border as a site of struggle between traders and customs officials:

It is a titanic fight as both officers and traders are strong. Traders have their way of fighting and avoiding customs, while customs use their power as official authority, but we do have our own ways of counteracting them. However, this fight ended by the time the cross-border traders realised that the only way of this fight was to meet with the authorities, as the government did in Rome with RENAMO. Conversation is the only way to avoid death of people, because the authorities were using fire weapons as well as some traders also had weapons.2

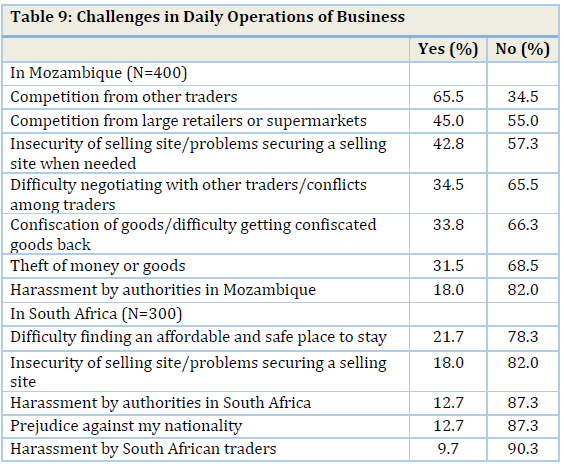

The challenges faced by the traders in their daily operations can be divided into two categories: those experienced while conducting business operations in Mozambique and those encountered when travelling to South Africa for business. In Mozambique, the most common problems related to competition from other traders (65.5%), competition from large retailers or supermarkets (45%), insecurity or problems securing a selling site (43%), conflicts with other traders (35%) and confiscation of merchandise (34%) (Table 9).

Theft of goods is experienced by the traders on their way home from South Africa. This is related to renewed conflict in Mozambique where armed opposition party members are said to attack travellers in order to loot their cash and goods. One of the focus group discussion participants noted that:

Bandits assault the Mukheristas taxis. They use mats with nails to punch the tyres. Then they steal their money. Some of Mukheristas do carry a lot of money, sometimes more than R 10, 000 in one trip. Last year one of our mates was on her way to Johannesburg when the taxi she was travelling in was ambushed near Machado. She lost more than R 40,000 cash in the robbery. There were 10 traders in that taxi.3

In South Africa, the biggest challenges relate to the difficulty of finding an affordable and safe place to stay in Johannesburg (22%), insecure trading sites (18%), prejudice against their nationality (13%), harassment by the police or municipal authorities (13%) and harassment by South African traders (10%).

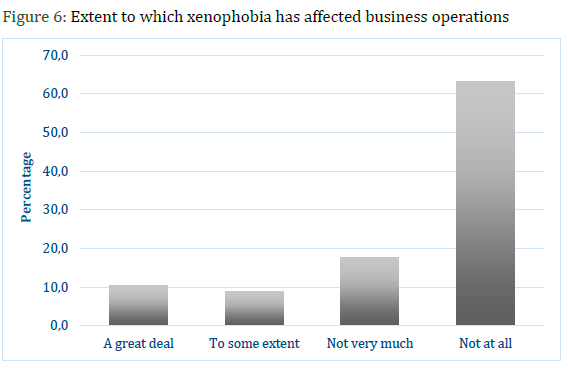

The study also sought to understand the cross-border traders' experiences of xenophobia in South Africa. Nearly one in five of the respondents (19%) noted that their business had been affected by xenophobia a great deal or to some extent (Figure 6). However, as many as 63% said that xenophobia had not affected their business at all. While these findings are encouraging, given the widespread xenophobic attitudes and attacks on informal entrepreneurs, it is likely that Mozambicans are able to avoid the worst forms of victimisation by having a legal right to be in the country, by not remaining long and by not competing directly with South African informal businesses (Crush & Ramachandran, 2015).

Finally, the respondents were asked about their treatment while conducting their business activities in both Mozambique and South Africa. Across all but one of the measures, the traders experienced more problems in Mozambique than in South Africa. They have had their business goods looted more often in Mozambique than in South Africa (47% versus 19%). They have been robbed more in Mozambique than in South Africa (39% versus 15%) and they have also been assaulted more (19% versus 12%). In addition, harassment by local authorities was more frequent in Mozambique (11%) than in South Africa (5%), as were incidents of unlawful arrest (6% and 1%, respectively).

Conclusion

Cross-border trading has become a way of life for many in Mozambique, geographically encompassing every part of the country and also involving migrants from other countries residing in Mozambique. Cross-border trade in Mozambique is primarily done by women with men mainly involved in the sale of the products brought back from South Africa. The traders are clearly playing a key role in supplying commodities that are in scarce supply in Mozambique.

Even though the sector is an important part of the Mozambican economy, little support is granted to the traders by local and municipal authorities or the private sector. Access to finance remains a major obstacle to business success as neither the government nor private banks provide loans to the traders.

This paper has demonstrated the specific roles played by the cross-border traders in the economies of both Mozambique and South Africa. It has shown that cross-border traders contribute to the South African economy through buying goods, as well as paying for accommodation and transport costs. The cross-border traders are directly contributing to the retail, hospitality and transport sectors in South Africa, thereby creating and sustaining jobs in those sectors. In Mozambique, the traders pay import duty for the goods bought in South Africa and they play a significant role in reducing poverty and unemployment in the country. Therefore, the policy environment should encourage rather than discourage the operation of ICBT. A change in the attitude of government towards cross-border traders is required as they do contribute to poverty alleviation, and there is a definite need for a forum that involves government and municipal officials and the traders.

Therefore, there is scope to include the informal traders in Mozambique's poverty alleviation strategy. Although they are regarded as informal, they pay taxes to the local authorities for access to trading sites. They also buy goods in South Africa, some of which are sold to formal retailers, thereby blurring the formal-informal boundary. The informal tag becomes a hindrance when considering the functioning of the Mozambican economy. The traders need to be seen as an essential component of the Mozambican (and South African) economy because, in their absence, both would be poorer than they are today.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) for its support of the SAMP Growing Informal Cities Project.

References

African Development Bank (ADB). 2016. African Economic Outlook 2016. Abidjan: ADB. [ Links ]

Akinboade, O. 2005. A review of women, poverty, and informal trade issues in East and Southern Africa. International Social Science Journal, 57: 255-275. [ Links ]

Amaral, P. and Quintin, E. 2006. A competitive model of the informal sector. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53: 1541-1553. [ Links ]

Baxter, M. and Allwright, L. 2015. Opportunities to Improve Financial Inclusion in Mozambique: Building on Investments and Economic Activities Associated with the Extractives Sector. Report by OzMozis for FSDMoç (Financial Sector Deepening - Mozambique), Maputo: OzMozis Lda. [ Links ]

Becker, K. 2004. The Informal Economy: Fact Finding Study. Stockholm: SIDA. [ Links ]

Benjamin, N. and Mbaye, A. 2012. The Informal Sector in Francophone Africa: Firm Size, Productivity and Institutions. Washington DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

Brooks, A. 2012. Riches from rags or persistent poverty? The working lives of secondhand clothing vendors in Maputo, Mozambique. Textile: The Journal of Cloth & Culture, 10: 222-237. [ Links ]

Brooks, A. 2013. Stretching global production networks: The international second-hand clothing trade. Geoforum, 44: 10-22. [ Links ]

Brooks, A. 2015. Clothing Poverty: The Hidden World of Fast Fashion and Second-Hand Clothes. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Burra, N. 2005. Crusading for children in India's informal economy. Economic and Political Weekly, 40: 5199-5208. [ Links ]

Christie, F. and Hanlon, J. 2001. Mozambique and the Great Flood of 2000. London and Oxford: IAI and James Currey. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Ramachandran, S. 2015. Doing business with xenophobia. In: Crush, J. Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Ottawa and Cape Town: IDRC and SAMP. [ Links ]

de Oliveira, C., Pivoto, D., Spanhol, C. and Corte, V. 2015. Developments and competitiveness of Mozambican chicken meat industry. RAIMED - Revista de Administração IMED, 5: 205-216. [ Links ]

de Vletter, F. and Polana, E. 2001. Female Itinerant Maize Traders in Southern Mozambique: A Study of a Higher-End Informal Sector Activity and its Potential for Poverty Reduction. ILO/SAMAT Discussion Paper No. 17. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [ Links ]

Desai, M. 2009. Women cross-border traders: Rethinking global trade. Development, 52: 377-86. [ Links ]

Dibben, P., Wood, G. and Williams, C. 2015. Towards and against formalization: regulation and change in informal work in Mozambique. International Labour Review, 154: 373-392. [ Links ]

Dlela, D. 2006. Informal Cross Border Trade: The Case for Zimbabwe. Occasional Paper No. 52, Johannesburg: Institute for Global Dialogue. [ Links ]

ECA (Economic Commission for Africa). 2010. Assessing Regional Integration in Africa IV: Enhancing Intra-African Trade. Addis Ababa: Economic Commission for Africa. [ Links ]

Ericsson, A. and Brooks, A. 2014. African second-hand clothes: Mima-te and the development of sustainable fashion. In: Fletcher, K. and Tham, M. (Eds.). Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Finmark Trust, 2009. FinScope Mozambique Survey, 2009: Survey Report. Johannesburg: Finmark Trust. [ Links ]

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2004. Child Labour and the Urban Informal Sector in Uganda. Kampala: ILO and Government of Uganda. [ Links ]

ILO. 2009. Global Employment Trends - Update. Geneva: ILO. [ Links ]

Jenkins, P. 2012. Home Space: Context Report. Copenhagen: Danish Research Council. [ Links ]

Jenkins, P. 2013. Urbanization, Urbanism and Urbanity: Home Spaces and House Cultures in an African City. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Jones, S. and Tarp, F. 2013. Jobs and Welfare in Mozambique. WIDER Working Paper No. 2013/045, Helsinki: UNU-WIDER. [ Links ]

Kamete, A. and Lindell, I. 2010. The politics of 'non-planning' interventions in African cities: Unravelling the international and local dimensions in Harare and Maputo. Journal of Southern African Studies, 36: 889-912. [ Links ]

Lesser, C. and Moisé-Leeman, E. 2009. Informal Cross-Border Trade and Trade Facilitation Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa. OECD Trade Policy Working Papers No 86, Paris, OECD. [ Links ]

Macamo, J. 1999. Estimates of Unrecorded Cross-Border Trade between Mozambique and her Neighbors: Implications for Food Security. USAID Technical Paper No. 88, Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). [ Links ]

Nucifora, A. and da Silva, L. 2011. Rapid growth and economic transformation in Mozambique 1993-2009. In: Chuhan-Pole, P. and Angwafo, M. (Eds.). Yes, Africa Can: Success Stories from a Dynamic Continent. Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

Paulo, M., Rosário, C. and Tvedten, I. 2007. Xiculongo: Social Relations of Urban Poverty in Maputo, Mozambique. Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) Report No 13, Chr. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute. [ Links ]

Peberdy, S. 2000a. Border crossings: Small entrepreneurs and informal sector cross border trade between South Africa and Mozambique. Tjidschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geographie, 91: 361-378. [ Links ]

Peberdy, S. 2000b. Mobile entrepreneurship: informal sector cross-border trade and street trade in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 17: 201219. [ Links ]

Peberdy, S. 2007. Monitoring Small Scale Cross Border Trade in Southern Africa. SAMP Report for Regional Trade Facilitation Programme. Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Peberdy, S. and Crush, J. 1998. Trading Places: Cross Border Traders and the South African Informal Sector. SAMP Migration Policy Series No 6, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Peberdy, S. and Crush, J. 2001. Invisible trade, invisible travellers: The Maputo Corridor Spatial Development Initiative and informal cross border trading. South African Geographical Journal, 83: 115-123. [ Links ]

Peberdy, S., Crush, J., Tevera, D., Campbell, E., Zindela, N., Raimundo, I., Green, T., Chikanda, A. and Tawodzera, G. 2015. Transnational entrepreneurship and informal cross border trade with South Africa. In: Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Ottawa and Cape Town: IDRC and SAMP. [ Links ]

Raimundo, I. 2010. Gender, Choice and Migration: Household Dynamics and Urbanisation in Mozambique. Saarbrucken, Germany: Verlag Dr. Muller Aktiengesellschaft & Co. KG. [ Links ]

Raimundo, I., Crush, J. and Pendleton, W. 2014. The State of Food Insecurity in Maputo, Mozambique. AFSUN Urban Food Security Series No. 20, Cape Town: AFSUN. [ Links ]

Rogerson, C. 2016. Policy responses to informality in urban Africa: The example of Maputo, Mozambique. GeoJournal, doi: 10.1007/s10708-016-9735-x.

Söderbaum, F. 2007. Blocking human potential: How formal policies block the informal economy in the Maputo Corridor. In: Guha-Khasnobis, B., Kanbur, R. and Ostrom, E. (Eds.). Linking the Formal and Informal Economy: Concepts and Policies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sparks, D. and Barnett, S. 2010. The informal sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: Out of the shadows to foster sustainable employment and equity? International Business & Economics Research Journal, 9: 1-11. [ Links ]

Thorsen, D. 2012. Children Working in the Urban Informal Economy: Evidence from West and Central Africa. Briefing Paper No. 3, Dakar: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Ulset, A. 2010. Formalization of Informal Marketplaces: A Case Study of the Xikhelene Market, Maputo, Mozambique. MA Thesis. Oslo: University of Oslo. [ Links ]

War on Want. 2006. Forces for Change Informal Economy Organisations in Africa. London: War on Want. [ Links ]

Wilson, D., Velis, C. and Cheeseman, C. 2006. Role of informal sector recycling in waste management in developing countries. Habitat International, 30: 797808. [ Links ]

1 Interview, 3 September 2014.

2 Ibid.

3 Focus Group Participant, Zimpeto market, 5 December 2014.