Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.2 Cape Town 2017

ARTICLES

The Owners of Xenophobia: Zimbabwean Informal Enterprise and Xenophobic Violence in South Africa

Jonathan CrushI; Godfrey TawodzeraII; Abel ChikandaIII; Daniel TeveraIV

IInternational Migration Research Centre, Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb St West, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada N2L6C2. Email address: jcrush@balsillieschool.ca

IIDepartment of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Limpopo, P. Bag X1106, Sovenga. Email address: godfreyltawodzera@yahoo.com

IIIDepartment of Geography & Atmospheric Science, and African & African-American Studies, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas State, USA 66045. Email address: achikanda@ku.edu

IVDepartment of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Western Cape, Robert Sobukwe Road, Bellville 7535. Email: dtevera@uwc.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This paper is a contribution to our understanding of the intertwined economic and political crises in Zimbabwe and the crisis of xenophobia in South Africa. There have been few studies to date specifically examining the impact of xenophobic violence on Zimbabweans trying to make a living in the South African informal economy. The paper first provides a picture of Zimbabwean migrant entrepreneurship using survey data from a 2015 study of migrants in the informal economy. All of the Zimbabwean entrepreneurs interviewed in depth for the study in 2016 had either witnessed or been the victims of xenophobic violence or both. The interviews focused on the experience and impact of xenophobic violence on personal safety and business operations. The migrant accounts clearly demonstrate that they see xenophobia as a key driver of the hostility, looting and violence that they experience. The paper argues that the deep-rooted crisis in Zimbabwe, which has driven many to South Africa in the first place, makes return home in the face of xenophobia a non-viable option. Zimbabweans are forced to adopt a number of self-protection strategies, none of which ultimately provide insurance against future attack.

Keywords: Zimbabwean Informal Enterprise and Xenophobic Violence.

"South Africans are very xenophobic - they are the owners of xenophobia" (Zimbabwean migrant, Cape Town, 2016).

Introduction

The above arresting image of South Africans as the "owners of xenophobia" is confirmed by numerous surveys suggesting that levels of xenophobia in South Africa are unprecedented globally (Crush et al., 2013). South Africa's crisis of xenophobia is defined by the discrimination and intolerance to which migrants are exposed on a daily basis. According to Misago et al. (2015: 17), xenophobia manifests in "a broad spectrum of behaviours including discriminatory, stereotyping and dehumanizing remarks; discriminatory policies and practices by government and private officials such as exclusion from public services to which target groups are entitled; selective enforcement of by-laws by local authorities; assault and harassment by state agents particularly the police and immigration officials; as well as public threats and violence [...]that often results in massive loss of lives and livelihoods."

The nub of the crisis of xenophobia in South Africa is when feelings of hostility and intolerance manifest as extreme xenophobia, which Crush and Ramachandran (2015a) define as "a heightened form of xenophobia in which hostility and opposition to those perceived as outsiders and foreigners is strongly embedded and expressed through aggressive acts directed at migrants and refugees [and] recurrent episodes of violence." Xenophobic violence represents 'tipping points' or intense moments in the general ongoing crisis of xenophobia. Southern African Migration Project's (SAMP) national surveys have consistently found that a significant minority of South African citizens are willing to resort to violence to rid their communities of migrants (Crush, 2008; Crush et al., 2013). The deadliest examples of extreme xenophobia in South Africa to date were high-profile and widespread violence against migrants and refugees in May 2008 and March 2015. The nature and impacts of the 2008 crisis are now well-documented, although there remain differences of opinion about its causes (Bekker, 2015; Cabane, 2015; Desai, 2015; Everatt, 2011; Hassim et al., 2008; Hayem, 2013; Landau, 2012; Steinberg, 2012).

For all its strengths, the literature on May 2008 tends to treat the victims of xenophobic violence in an undifferentiated fashion, leading to the assumption that all migrants - irrespective of national origin, legal status, length of time in the country and livelihood activity - were equally at risk. Yet, attitudinal surveys clearly show that South Africans differentiate between migrants of different national origin and that Zimbabweans are amongst the most disliked (Crush et al., 2013). Discussions of May 2008 also do not differentiate sufficiently between the types of targets that were attacked. For example, many African migrants and refugees operated small businesses in the informal economy of affected urban areas and these enterprises came under sustained attack during the pogrom. In 2015, one of the explicit targets of the xenophobic attacks was informal businesses run by migrants and refugees. Violent attacks on migrant and refugee entrepreneurs and their businesses have not been confined to acute episodes of extreme xenophobia such as those in May 2008 and March 2015 (Charman & Piper, 2012; Crush et al., 2015; Crush & Ramachandran, 2015a, 2015b; Tevera, 2013). Ongoing acts of extreme xenophobia have increasingly manifested in the form of collective violence targeted at migrant and refugee-owned businesses.

The frequency and ferocity of such attacks have increased over time and cannot simply be written off, as the state seeks to do, as 'mere criminality.' Chronic extreme xenophobia has prompted various responses and remedial actions by migrants and refugees including paying protection money, beefing up business security, arming in self-defence, avoiding neighbourhoods known to be particularly dangerous and moving away from the major cities to smaller urban centres (Crush et al., 2015a). Zimbabweans are not the only small business owners who have become victims of extreme xenophobia in South Africa; attacks on migrants and refugees from other countries are also well documented (Gastrow, 2013; Gastrow & Amit, 2015; Piper & Charman, 2016). However, there have been few studies to date specifically examining the impact of xenophobic violence on Zimbabweans trying to make a living in the South African informal economy (Duri, 2016; Hungwe, 2014; Sibanda & Sibanda, 2014).

This paper is based on two sources of data. First, SAMP's Growing Informal Cities Project surveyed over 1,000 randomly selected migrant-owned informal sector enterprises in Cape Town and Johannesburg in 2015 (Peberdy, 2016; Tawodzera et al., 2016). The survey sample included 304 Zimbabwean-owned enterprises. For the purposes of this paper, we extracted this data from the larger database. Second, 50 in-depth interviews were conducted in 2016 with Zimbabwean informal business-owners in Cape Town, Johannesburg and Polokwane as part of SAMP participation in the Migrants in Countries in Crisis (MICIC) project. This paper is a contribution to our understanding of the intertwined economic and political crises in Zimbabwe and the crisis of xenophobia in South Africa. It also aims to contribute to the more general literature on migrants in countries in crisis in a situation of intersectionality where migrants are forced to navigate a state of crisis in both the country of origin and the country of destination. The term "migration in countries in crisis" is usually taken to refer to the plight of migrants caught up in an unexpected crisis situation in a "host country" (Koser, 2014; Martin et al., 2014; Weerasinghe & Taylor, 2015). Although emergencies affecting migrants are becoming increasingly complex and multifaceted, the intersection of crisis situations in countries of origin and destination have been given insufficient attention (IOM, 2012; McAdam, 2014). A dual or multiple crisis situation spanning origin and destination presents new, and not easily resolved, challenges for the management of crisis and the safety of migrants (Hendow et al., 2016; Perching, 2016).

Crisis-Driven Migration

Betts and Kaytaz (2009: 2) label the exodus from Zimbabwe an example of "survival migration," which they define as refugees and "people who are forced to cross an international border to flee state failure, severe environmental distress, or widespread livelihood collapse." Under conditions of survival migration, the traditional distinction between refugees and economic migrants breaks down (Betts, 2013). The argument that all Zimbabwean migrants should be defined as "survival migrants" requires closer scrutiny. For example, it is based in part on the view that conditions in Zimbabwe are so dire that out-migration for survival is the only option. However, this does not explain why the majority of Zimbabweans have not left nor the role of migration in reducing pressures for further out-migration through remittances (Crush & Tevera, 2010).

The argument that all Zimbabweans are "survival migrants" also runs the risk of homogenising migrant flows and downplaying the heterogeneity of migration movement out of the country. The idea that all migrants from Zimbabwe are "survival migrants" also seems to rest on the admittedly desperate situation of migrants in squalid transit shelters in the border town of Musina and at overcrowded safe havens such as churches (Betts & Kaytaz, 2009; Kuljian, 2013). The idea of "survival migration" fits this sub-set of Zimbabwean migrants but certainly does not encompass them all. Far from being the desperate and destitute people conveyed by images of "survival migration," many Zimbabwean migrants to South Africa exhibit considerable ingenuity, industry and energy.

A recent survey of Zimbabwean migrants in Cape Town and Johannesburg found that over 60% of migrants who had come to South Africa in the previous decade were formally employed and only 18% were unemployed (Crush et al., 2015b). At the same time, increasing numbers were doing more menial jobs including 25% in manual work, 13% in the service industry and 8% in domestic work. A longitudinal study of day labourers in Tshwane demonstrates the increase in Zimbabweans seeking casual work, which rose from 7% in 2004 to 33% in 2007 to 45% of workseekers in 2015 (Blaauw et al., 2016).

The extent of participation by Zimbabwean migrants in the South African informal sector is unknown. SAMP's 2005 national survey of migrant-sending households in Zimbabwe found that 21% of working migrants outside the country were in the informal economy (Crush & Tevera, 2010: 12). A 2007 survey of migrants in Johannesburg found that 19% were working as hawkers or artisans (Makina, 2010). SAMP's 2010 survey of recent Zimbabwean migrants in Johannesburg and Cape Town found that 27% were working or deriving income from the informal economy (Crush et al., 2015a). Crush and Tawodzera's (2017) survey of poorer Zimbabwean households in South Africa found that 36% of household members in employment were working in the informal economy. While indicative, these studies suggest that somewhere between 20-30% of Zimbabwean migrants in major South African cities could be involved in the informal economy. They also suggest that the importance of informal sector employment to Zimbabweans has increased over time.

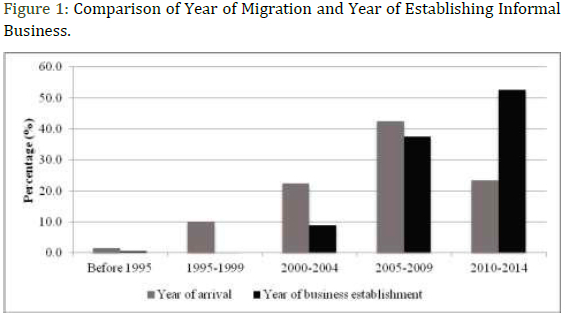

The 2015 SAMP survey of migrant enterprises found a distinct gender bias in both cities with 60% of Zimbabwe entrepreneurs in Cape Town and 65% in Johannesburg being male. This was a marked contrast to the business of informal cross-border trading between Zimbabwe and South Africa which is dominated by female Zimbabweans (Chikanda & Tawodzera, 2017). The number of migrant entrepreneurs who arrived in South Africa peaked in the years between 2005 and 2010, at the height of the economic crisis in Zimbabwe, and appears to have fallen since (Figure 1). Less than 2% had migrated to South Africa before 1994. Nearly 18% of the Johannesburg migrant entrepreneurs had moved there before 2000 compared to only 2% of those in Cape Town. Over time, Cape Town has become an increasingly attractive destination. As many as 88% of the migrants in Cape Town arrived in the city after 2005 (compared to 52% of those who moved to Johannesburg).

Only 5% of the survey respondents had experience working in the Zimbabwean informal economy prior to migrating to South Africa. Those with prior experience had generally been involved in informal cross-border trading and were therefore familiar with South Africa. One male migrant described the transition as follows:

I used to come here as a trader from the early 2000s. I stopped in 2005 and came here to South Africa to live. My business is about making and selling electric jugs and brooms. I used to come here and sell them and go back home. There are some reasons why I came to stay. One is that the economic situation was getting bad. [Zimbabwe] was no longer the same. I was selling things and not making much money. I wanted to build a house in Zimbabwe and I was failing to do so. The cost of living was high. I had just married and things were tough. Then there was the issue of politics. My wife was harassed when I was in Johannesburg buying goods. They came and searched our house and they found nothing. They wanted evidence that I was a sell-out, but they did not find anything. My wife was pregnant so I saw that they could injure her if they came back next time. That is when I moved to South Africa (Johannesburg Interview No. 4).

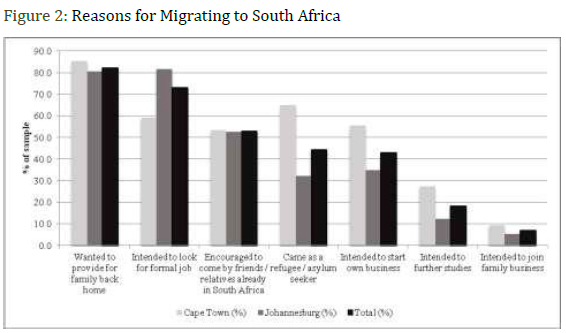

In this case, economic hardship and political harassment were additional factors in the decision to move to South Africa. The overall reasons for migration to South Africa were clearly related to the ongoing economic crisis in Zimbabwe. Over 80% agreed with the proposition that they had come to South Africa in order to provide for family back home. As many as 73% said they had come to South Africa to look for employment (Figure 2). There was a marked difference here between the Johannesburg and Cape Town respondents (with 82% and 59% in agreement, respectively) which may reflect differences in the perception (and reality) of labour market access in the two cities.

The reverse was true with regard to starting a business as a reason for migration, with 56% in Cape Town and 35% in Johannesburg in agreement. In general, this suggests that Johannesburg is seen as a place where it is easier to obtain formal sector employment and Cape Town is a more amenable location for starting an informal business. Unemployment was a significant driver of migration, with 39% of the sample reporting that they were unemployed prior to leaving Zimbabwe. Again, there was a marked difference between the entrepreneurs in the two cities: only 20% of the Cape Town respondents were unemployed prior to leaving compared with 51% of the Johannesburg respondents. The high proportion who said that they had migrated as refugees or asylum-seekers is a reflection of the fact that over 300,000 Zimbabweans applied for asylum-seeker permits between 2004 and 2010 in order to legalise their stay in South Africa (Amit & Kriger, 2014). At the same time, a proportion of this number left because of political persecution. Exactly how many is difficult to say given that South Africa has approved less than 3,000 of all Zimbabwean refugee claimants.

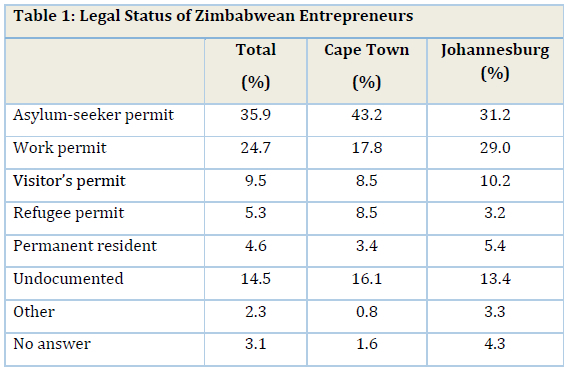

The survey found that relatively few of the Zimbabwean entrepreneurs did not have papers permitting them to be in and/or legally work in the country (Table 1). Just over one-third of the migrants had asylum-seeker (Section 22) permits but only 5% had recognised refugee status (Section 24 permits). Both asylum-seekers and refugees have a legal right to work and earn. Around one-quarter had work permits, which the majority would have acquired under the Zimbabwe Dispensation Programme (ZDP) in 2010 and 2014 (Thebe, 2017). Around 10% of the migrants had visitor's permits which are usually issued for 90 days at a time. Only 15% were undocumented and did not have permits to reside and/or work in South Africa.

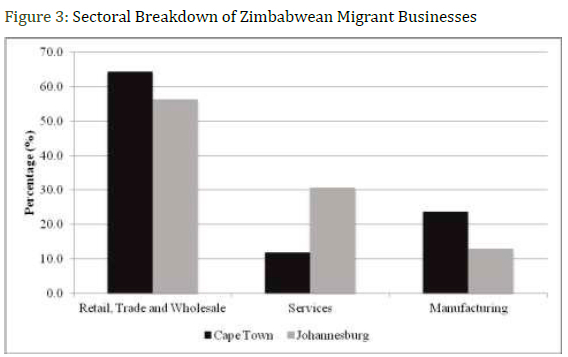

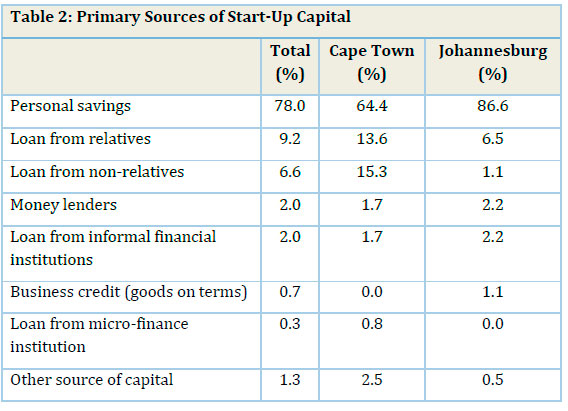

The majority of the surveyed Zimbabwean migrant enterprises were in the retail, trade and wholesale sector, followed by services and manufacturing, with slight differences between the two cities (Figure 3). As Figure 1 shows, most migrants did not immediately start an informal business on arrival but first needed to raise start-up capital. Migrants and refugees face severe obstacles in accessing loans from formal sources in South Africa as they require collateral (Tawodzera et al., 2015). Just over three-quarters of the migrant entrepreneurs in this survey relied on their personal savings to start their businesses (Table 2). There was slightly greater reliance on personal savings by entrepreneurs in Johannesburg (87%) than Cape Town (64%). More Zimbabwean migrants in Cape Town were able to access funds from relatives and non-relatives.

Experiencing Xenophobia

All of the Zimbabwean entrepreneurs interviewed in depth had either witnessed or been the victims of xenophobic violence or both. The interviews focused on the experiences and impact of xenophobic violence on personal safety and business operations. Many of those interviewed had come to South Africa after the nationwide attacks on migrants in May 2008 but none were unaware of the violence or did not know some of the victims. Those who had been in the country at the time lost almost everything they had, but they did not return permanently to Zimbabwe, a primary objective of their attackers. Instead, they took refuge in shelters and churches and re-started their businesses once the worst of the violence was over. Three accounts in widely separated parts of the country (Alexandra Park in Johannesburg, Imizamo Yethu in Cape Town and Mankweng in Polokwane) show both the destructive nature of the 2008 xenophobic violence and the responses of the migrants:

During the xenophobic attacks of 2008 I was there. My musika was destroyed. People came marching and asking foreigners to leave [...] They came and destroyed the musika. It was made up of cardboard and corrugated iron sheets. They destroyed it. The cardboard was burnt and the corrugated sheets were taken and some of them thrown all over. I lost a lot of money there. Maybe ZAR 3,000. I had a lot of goods and I was also selling beans, groundnuts and even matemba and fish. I lost everything. I was only able to carry a few things and fled. Otherwise they would have killed me as well. What could they do? The people that start the violence are the ones that can even kill you. Many people died in Alex Park. They died. I actually saw a person who had been stoned to death and he was lying there for a day without the police getting him (Johannesburg Interview No. 13).

I had just closed my spaza and had not even reached home when I saw people singing and getting up here. They were coming from the direction of the police station coming uphill. We had already heard of xenophobia and so I knew it was happening here. I wanted to go back and get some things from the spaza but I was too late because they were moving fast. I just had time to change direction and ended up in Hout Bay. There were other Zimbabweans who had also run away and were there. I joined them and we went to Wynberg and stayed there at the police station. There were many of us. Like me, most people had nothing because they never had time to go home and get clothes or blankets. I called someone in Rosebank and they told us that they were staying at a Methodist church there so that is where we went. We spent three weeks there. My spaza shop was looted. I never got anything back, not even a single sweet. They took everything so I had to start from scratch (Cape Town Interview No. 20).

I was living in Mankweng with two other ladies from Zimbabwe. We were renting a room in Zone 2. We had been living there for some time and we knew most of the people there. But when xenophobia erupted it was as if we had never lived there. We saw some of the people that we knew actually looting things belonging to foreigners. We were confronted by a group of young men - and they demanded money otherwise they would kill us. It was like a dream. We could not believe it. We were robbed there, close to the road, where everyone could see. They just took what they wanted and went away singing. I lost my bag, my wallet and my friend also lost everything. I was scared that we could be killed or raped. Even now I cannot believe that I survived. We went to the highway, the N1 and hiked to Musina and then home to Zimbabwe. I only came back after a month when things had calmed down. I stopped doing business for over a month. I had no money to start over. I had to borrow some money and it took time to recover. Some of my customers moved with my money and I never recovered the money. I had to start from scratch and it was difficult (Polokwane Interview No. 3).

Most of the respondents recounted incidents of violence that had personally affected them since 2008. These accounts revealed a number of features common to all xenophobic attacks on migrant businesses. First, much of the violence seems to the migrants to be spontaneous and occurs without warning. In practice, this is rarely the case as many attacks are preceded by community meetings from which migrants are excluded (Landau, 2012). Therefore, they have little notice or ability to take evasive action. As one victim of violence in the informal settlement of Diepsloot near Johannesburg in 2013 observed:

They just occur haphazardly. We cannot always tell what happens next so it is difficult to do anything and to think of a way to respond. It just happens when you are least aware of the problems that are about to erupt. Sometimes we are caught up with all our wares and they are destroyed and stolen and so it is difficult to do anything (Johannesburg Interview No. 10).

The journalist, Anton Harber's (2011) portrait of Diepsloot paints a picture of a volatile settlement in which vigilante justice and attacks on foreign-owned businesses are common. In 2008, for example, "they showed no discrimination in targeting men, women and children, and destroyed, looted and burnt down their businesses and houses" (Harber, 2011: 123).

Second, the perpetrators of xenophobic violence are often from the same community and are even personally known to the victims:

The people that robbed us are in this community and we know them. They are the community members here. Some of the people here do not like us foreigners. They pretend when you deal with them to like us. But they do not like us (Johannesburg Interview No. 2).

The fact that migrant entrepreneurs are able to provide goods, including food, at competitive prices and offer credit to consumers is clearly insufficient to protect them when violence erupts. In one part of Khayelitsha, there is reportedly little violence as long as migrant business owners pay protection money to the powerful local taxi association. In many other areas, the respondents reported that community leaders are either ineffective in dealing with the violence or, in some cases, actively foment hostility and instigate attacks.

Third, the looting of stock on the premises is a constant feature in the narratives of the migrant business-owners. As one observed:

There are hard core thieves who rob people and also jobless people around who are now taking advantage of these xenophobic attacks and robbing people to get money because they have nothing to do with their lives (Johannesburg Interview No. 1).

However, the respondents consistently maintained that robbery per se was not the prime motive for the attacks. As one respondent noted:

They target shops, the owners as well as the goods inside. They only target foreign owned shops. There is more to that (than robbery), they want us to leave their country because they hate our businesses here and they say we are finishing their jobs (Johannesburg Interview No. 3).

Others pointed out that South African business owners in the same vicinity are left alone during crowd violence, that attacks often involve vicious physical assaults against the person, and that they are usually accompanied by vituperative xenophobic language:

People were being beaten up and they were dying. A group of South Africans moved around this whole squatter camp terrorising all foreigners and they used to move with someone who knew where all foreigners stayed. These people moved with knobkerries, metal sticks, sjamboks and any sort of weapon you can think of for distraction. If you were a foreigner and did not have a passport they would beat you up (Johannesburg Interview No. 3).

The violence was there for two days or so and I thought it was over. I went to service a car in Heideveld. When I was coming back I passed through my friend's place and he accompanied me half way. When he had gone, and I was in Sisulu Street down there, they attacked me with a plank and something like a rubber. They hit me all over and even stomped on me. It was xenophobia. They told me that they would kill me and that I was a foreigner and not wanted here. I cried and asked for them to leave me and they continued. No-one intervened. It was past 8pm and there were still people moving about. A few other guys joined in. I was saved by a car that passed, when its lights flashed at them they ran away. They told me that next time they would kill me (Cape Town Interview No. 3).

I was robbed in broad daylight here in Masiphumelele. It was not a real robbery, it was a gang just saying foreigners must leave. I was about to park my car when the group of men descended on me. They asked for my ID and when I said let me go and get it, they pounced on me and started pushing me. My neighbours just looked on. I asked what I had done but they were just singing derogatory songs. It was pure xenophobia. Most of the locals here joined and wanted to chase me out. Even my neighbours were caught up in that chaos and were told to go. You see, when there is a small thing that happens, it ends up being that foreigners must be chased away. Is that not xenophobia? Many times here I have been insulted only because I am a foreigner. You ferry someone's goods and they pay you little and the next time you want your balance they start some story that you are a thief or so on and the others join in. Is that not xenophobia? Why do they not do that to South Africans? Why only to foreigners? These people have xenophobia in their blood (Cape Town Interview No. 13).

Fourth, many of the accounts describe how an anti-government service delivery protest or march can quickly disintegrate into mob violence and looting of shops and stores owned by migrants. The connection between the two events is not immediately obvious but, according to the respondents, the looting is never indiscriminate but only targets migrants. The reason, according to some, is that they become scapegoats for the government's failure to deliver services

South Africans are not friendly. They say this is their country and they do what they want to us, hurting us. These locals ask services from their government and if they are not given them they demonstrate and if their concerns are not heard they put their frustrations on foreigners. Most of them are uneducated so they think we are the cause of their problem and when they see you in business they think you are taking over their business. They target foreigners in business. They start with businesses and sometimes when their concerns are not heard they even start attacking those not in business and foreigners in their homes (Cape Town Interview No. 11).

Fifth, there was some evidence of "violent entrepreneurship" involving attacks orchestrated by South African competitors. One Zimbabwean entrepreneur in Polokwane, for example, described how he had established a business selling and repairing cell phones. He said that his South African competitors reported him to the police for dealing in stolen phones but his records showed that all his transactions were legitimate. According to him they had tried several times to get him arrested. The reason? "They even tell me to my face that they want me out of this place because I am a foreigner. How can they fail to make business when I as a foreigner is doing well? That is their quarrel. Some have even organised thieves to rob me and I have been robbed twice."

Sixth, xenophobic violence is gender-indiscriminate in that both male and female migrants recounted equally harrowing stories. Lefko-Everett (2010) has argued that one of the most common strategies adopted by Zimbabwean women migrants travelling to South Africa as cross-border traders is to travel and stay in groups as a means of protection. Zimbabwean women living in South Africa and selling on the streets are generally unable to benefit from group protection. One woman in Johannesburg described her experience and helpless situation as follows:

They were calling me names and some were telling me to go back to Zimbabwe saying I would die that night. Some of the foreigners who were there and had been trying to support me saw that the situation was getting serious and just disappeared. I lost most of my goods that day as people just started taking them. The lady who was selling close to me also lost her products as people just took and went. It was terrible. No-one was on our side. They just did not care that we were females. They just harassed us. I even thought of going back home that day. What stopped me is the thought of going back to look at my kids without anything. And there was nothing that I would do in Zimbabwe. Here we live with xenophobia every day. We see it happening and there is nothing that we can do (Johannesburg Interview No. 10).

Finally, the respondents differed on whether Zimbabweans were particular targets. Most said that all foreign-owned businesses were targeted, not simply Zimbabweans. A number commented that the type of business made a difference, with food and grocery shops being especially vulnerable. However, virtually all agreed on one point: the purpose of the attacks was not simply to steal certain desirable goods but to clean them out and destroy their business premises and operations so that they could not continue to operate. There were numerous examples of entrepreneurs who had lost all of their stock and also had their premises vandalised and wrecked, even when they were operating from containers, which are generally considered to be the best form of protection:

They broke and took away everything as if they don't want one to be in business. If they wanted goods only, they would have just broken in and taken stuff only but they destroyed, breaking windows and even removing them and most people are not yet back on their feet (Cape Town Interview No. 8).

In 2011, the business was attacked by local people. The shop was attacked by the mob. They looted everything and left me with almost nothing. I had goods worth over R 15,000 in here. Everything except some few bottles of cooking oil and cigarettes remained. It almost destroyed my business. I was left with very little. I had not saved much so it took me some time to be on my feet again. I had to borrow some money from friends because I needed to restock. I cannot afford to stock much as I am not sure what happens tomorrow. These days we no longer put everything here. Some of the stock is at home so that if the steal here, I will have some of my stock at home to start again. I just replenish what is in short supply here (Cape Town Interview No. 10).

We had just brought stuff from Zimbabweans on a Sunday. They were worth about R 10,000 and included nyimo, mbambaira, nzungu, matemba and we had also just stocked the local products. We had bought a lot of crates like onions for about ZAR 15,000. All these products were in the container and the container was destroyed. They upended it and spilled all the products that were inside to the ground. Some of the products were burnt, taken and we were left with nothing. And because we had just stocked we didn't have any money at home so we had to start all over from scratch (Cape Town Interview No. 1).

Responses to Xenophobic Violence

The pervasive view amongst South African politicians that xenophobia does not even exist in the country seems particularly odious given the experiences of Zimbabwean and other migrants. The term "xenophobia" itself was used by all the respondents to describe the harassment and physical abuse they experience and some even referred to the widespread violence in 2008 and 2015 as "the xenophobia." However, they were also asked if they thought South Africans were xenophobic and, if so, why. No-one answered the question in the negative. A selection of responses clearly indicate that for Zimbabweans, South Africans are, indeed, the "owners of xenophobia":

I can say that three-quarters of them show their hatred towards us foreign nationals. They don't like us. Xenophobia is a South African thing. It happens more than anywhere in the world I think. Everything they do shows it. They do not like us. They speak to us like we are not like them. They look down upon us. They are like that whether they are Christians or not. The children learn it from their parents. They call us makwerekwere. Do you know even small kids can call you makwerekwere? Is that not xenophobic? (Johannesburg Interview No. 2).

If you want to see how they hate us, just have a disagreement and they will tell you bad things, telling you that you will die. What kind of a person wants to see another person dying? Life is sacred, but here in South Africa no one seems to care about that. They would rather you die so that they can get whatyou have. This is the only society where people kill each other over very simple disagreements (Johannesburg Interview No. 10).

You can see it almost every day in the train and other places when you pass they call you derogatory names like makwerekwere. We can see it every day in our daily life and we live with it. It does not only happen to people doing business, but it happens to any foreigner no matter whom. If you can't speak their language, you already are a kwerekwere and you are in trouble (Cape Town Interview No. 4).

The way they see us, they see us as if we are lesser than them. They say bad things about us, like we are thieves and we are ugly and we do not bath, such things. But they know most of these things are not true but they like saying them anyway (Cape Town Interview No. 10).

Is there a country in the world where foreigners are killed and burnt like here? No. South Africa is a place like no other place. It is a country with people that do not care about other people. Look at the way they kill foreigners. The way they chase foreigners and steal their goods and injure them. That is not done by normal people. South Africans are xenophobic. They do not fear evil spirits from the dead. They just kill and the next hour they are busy braaiing and singing and eating amagwinya. They are not normal people (Cape Town Interview No. 12).

The language and practices of xenophobia cow the victims into silence and a sense of helplessness, short of returning to Zimbabwe, which is not seen as a viable option. As one respondent said:

"Here we live with xenophobia every day. We see it happening and there is nothing that we can do" (Johannesburg Interview No. 10). And another: "I remain silent because I am Zimbabwean and I can't go against what they say. But they have to realise that we are the same we have the same skin as black people but we just keep quiet even as they insult us" (Johannesburg Interview No. 12).

The interviews provide important insights into how migrant entrepreneurs themselves respond to the threat and reality of xenophobic violence. From the responses of some of the migrants, it appears that trying to "fit in" and integrate by learning local languages, dress codes and cultural practices is one way to try and pre-empt attacks (Hungwe, 2012, 2013). However, these strategies are no guarantee of protection when mob violence breaks out:

I was robbed during the day. There was a strike and I was coming from the shops. I was not here the previous day and so I did not know that there was a strike. When they saw me coming the mob ran to me. I was beaten and robbed. They knew I was a foreigner. I can speak three local languages and I spoke in isiZulu but they knew me, some of them and they said he is a Zimbabwean and they attacked me. If I was a local I was not going to be attacked. I had ZAR 1,800. All was taken. That was my money that I had collected from my customers. They robbed me because I was a Zimbabwean, a foreigner (Johannesburg Interview No. 2).

A number of the respondents observed that unlike some migrant groups, such as Somalis and Ethiopians, Zimbabweans are not inclined to band together to form associations or groups to lobby for and secure protection for their members. Some did suggest that there was safety in numbers and that by doing business in areas where there were many other migrant businesses, the chances of being attacked were considerably reduced. One respondent explained the attraction of running a business in the Johannesburg CBD as follows: "You will find that incidences of xenophobic attacks are very rare in Joburg central where they are a lot of foreigners. Also, Park Station is a strategic location which supplies the whole of South Africa so our protection as foreigners is better" (Johannesburg Interview No. 13). The downside of operating in safer spaces is that business competition is extremely fierce.

Most were aware that a great deal of the xenophobic violence was confined to low-income areas, particularly informal settlements. While it was possible for some to avoid doing business in these areas, and instead operating in areas of the city where attacks were less frequent, this was not a feasible option for all. Many Zimbabwean migrants to South Africa do not have the financial resources to afford accommodation nor the means to run a business anywhere other than informal settlements.

A number of the respondents noted that the unpredictability of the attacks made it difficult to plan in advance. Some said that they made sure that they did not keep all of their stock at the place of business, storing some of it at home or in rented containers. All tried to minimise the amount of cash they kept on the premises, although not many Zimbabwean entrepreneurs have access to formal banking facilities. One noted that as soon as he had made some money, he immediately remitted it to Zimbabwe "so that even if I am attacked, there is nothing much that they can take from me. It is better if my family can have that money" (Polokwane Interview No. 6). Another said that he was planning to relocate once he had sufficient capital saved up:

Surely experience is the best teacher but I think you plan when you have money, so I am thinking of saving a lot of money and looking for safer business locations like in town. I am thinking so because in 2008 they also attacked my business. They just broke and took away all my stuff, now they have burnt the structure down. So I re-constructed and started again so I am now thinking how I am to keep myself and my stuff safe (Cape Town Interview No. 15).

Various reactive strategies were mentioned when their businesses were attacked. These included temporarily ceasing business operations, staying indoors at home and moving to stay with friends or relatives in other parts of the city "until the dust settled," as one put it. Others said that the best strategy was simply to flee the area (or as one graphically put it "you run with your life"), if possible taking some valuable item with them which they could later sell and restart the business with. None of the respondents said that xenophobic attacks would put them permanently out of business. On the contrary, most said they would simply raise the capital and start up again.

The logical implication of the determination to stay in business is that xenophobic violence has failed in its two main aims: to drive migrant entrepreneurs out of business and to drive them out of the country and back to Zimbabwe. The respondents were asked if they would return to Zimbabwe as a result of xenophobic attacks and the general consensus was that they would not. A significant number noted that they had settled in South Africa with their families and did not want to return. Many more made reference to the fact that the crisis in Zimbabwe meant that there was nothing for them to return to, even if they wished to do so:

There is nothing in Zimbabwe. I am not going back. I am trying to make my life here. My wife is here and my child is here. I am not going back there. Zimbabwe is a country I love. It's just that at the moment things are tough and there is really nothing to do when you return back home (Johannesburg Interview No. 11).

While the hardships which I face in South Africa are many they are still better than the hardships I endured back in Zimbabwe. In the event of future attacks, I could try and survive because at least I will be doing something (Johannesburg Interview No. 13).

I could never go back because there are no means of surviving. I could simply have to look for an alternative way to survive while in South Africa. Even if they attack me I will look for another means to survive as long as I am not dead (Johannesburg Interview No. 19).

I am not going back. There is nothing to do in Zimbabwe especially because we left a long time ago. What will we do there? So we stay here because this is where our life is. We are establishing here and so if you leave you have to start again. I am not going back. When xenophobia starts we simply move to areas that are safe and return when it is quiet (Cape Town Interview No. 12).

Perceptions of Government Inaction

All of the respondents were asked about the response of the South African and Zimbabwean governments to xenophobic violence. The responses ranged from the outright cynical to the totally dismissive. Not a single respondent said they had been helped by either government and none were prepared to defend their response to xenophobic violence. Most were extremely critical of both governments. The general consensus was not that the governments did not do enough but rather that they did nothing at all. In the case of the Zimbabwean Government, the prevailing sentiment was captured by one Johannesburg respondent who said:

The Zimbabwean Government does nothing. I have never heard them comment or say anything about these attacks. They do not help us at all. They do not send anyone to come and see how we are living and even provide us with assistance. There is no government that helps us (Johannesburg Interview No. 2).

Explanations for why the government "does nothing" ranged from sheer lack of interest in what happened to Zimbabweans outside the country, a lack of resources to do anything to help and a desire to see Zimbabweans return home instead of staying in South Africa.

Much harsher criticism was reserved for the South African Government's practice of "doing nothing":

The South African government does not do anything. At least nothing that I know of. They are just silent. We just see the police, but they come too late and do not do anything. They do not arrest anyone even though you report. They are just moving about, but really doing nothing. I sometimes think that even the police hate us the foreigners. Would they do the same and not help if foreigners attack local people? No, they would arrest us. So the police do not help us and would rather see us gone. Even the community leaders do not do anything (Johannesburg Interview No. 2).

Some of the people in government are fuelling xenophobia. They are also xenophobic because they say a lot of things that are not true. Like we are the ones who are causing problems here. They had problems here before we came. They are very corrupt but they are the ones that tell people that foreigners are the cause of the problems. People listen to the government. They keep saying that foreigners are bad. What do you expect the people to do? The people follow their government (Cape Town Interview No. 5).

They are the ones that cause it so they do not care. The one that occurred in Durban it was the King who incited people. Now he is saying he did not do it but we all saw him on TV. The government does not care for us. They care about their people only. If it were foreigners doing violence against the locals, we would all be in jail (Cape Town Interview No. 6).

Some felt that xenophobic violence was tolerated by government because it supposedly achieved the desired effect of getting "foreigners" to leave the country.

A recurring theme was police inaction during episodes of mass xenophobic violence. Some felt that the police were extremely slow to respond. As one respondent noted "the police usually come late when everything has been done and people have been killed or their goods stolen" (Cape Town Interview No. 5). Others commented on how the police offered no protection even when they were present:

Both the City of Cape Town and the police are not protecting us at all. Like on the day that the people were demonstrating, the police were there. They were just walking. After they were passing, the people started taking our things. There was no one to protect us and no one to stop those people. So, I don't know what they are doing. I think they just put on uniform and walk around. When there is trouble they don't come to protect us (Cape Town Interview No. 4).

The police just stand at the robots. Or they run away. There is poor enforcement because their response is very slow. Containers were being opened and things taken while the police stared. They are either scared of the people or because it's their own people so they can't stop them. There were three police vehicles, but they just stood while people's containers were being opened. Only foreign containers were broken and they knew whose container it is. No containers for local Xhosas (South Africans) were broken into and destroyed (Cape Town Interview No. 12).

One respondent felt that the reason for inaction was that "South Africans do not fear police" and compared the police behaviour with that in Zimbabwe:

They throw stones at the police. Have you ever seen people throwing stones at the police in Zimbabwe? No, they do not do that. Here they just do what they want. So they attack foreigners even if the police are there. Unless the police are using teargas or throwing water. But they rarely do that. But you can run to a police station if you are close and seek refuge. There are other areas where the local people even attacked police stations - attacked foreigners in police stations (Cape Town Interview No. 7).

There was also a pervasive view that there was little point in reporting theft or assault to the police because nothing was ever done, based on past experiences of police inaction. Dockets may have been opened but the perpetrators were rarely arrested and brought to book and stolen goods were rarely, if ever, recovered:

It was the mob that took the things and what would I tell the police? Besides there were many people whose goods were destroyed that I never bothered. The police do not help much. It is useless to report to the police. The police here do not care. Especially if you are a foreigner. They will just tell you it is a mob. They cannot arrest a mob (Johannesburg Interview No. 2).

The argument that the police were not particularly concerned by what happened to "foreigners" was very common. One respondent claimed that even if a perpetrator was arrested, "as soon as they have gone around the corner they will ask for a bribe and release the person. As soon as the person is released they will either come and shoot you or permanently injure you" (Johannesburg Interview No. 18). Another said that they had reported a robbery to the police and even named the assailants but little was done:

They took down my details and the details of the things I lost. I listed all of them and went with them to the police station. I was told that they would call me when they have made progress and that was that. I went back but there was no progress. The officer who was dealing with the issue kept telling me there were no suspects and that there was nothing they could do. I even gave them some names of the suspects because I had seen some of them, but the police officer did not even take them down. He insisted that there needed to be a witness for him to put those people as witnesses. I thought he should have at least questioned them or gone to their homes and searched. Neither was done (Polokwane Interview No. 4).

Apart from the failure to protect, in a xenophobic environment in which migrants are extremely vulnerable, there is always the possibility that the police themselves might seek to take advantage of the situation for their own personal gain. This was certainly the view of many of the respondents who described persistent police harassment, and even theft, during business hours:

They know that we are not South Africans. Sometimes the metro and police can just come and take your products. During winter they came and took socks and hats. Once you just try to confront them, they tell you that this is not your country, go back to your country. Tomorrow the same thing can happen again. The police officer will just come and say they lost the gloves and take another pair. If that day they are in the mood of arresting people, they will arrest you despite the fact that they took your things before. Some are those who arrest you and ask for a certain amount of money like ZAR 200 even if you don't have it. Maybe that day you only made ZAR 50 and if you try to explain that you don't have the money, they threaten to take all your stock. If the stock value is more than ZAR 200 and I don't have it, I am forced to ask from other people. If they assist me, I give them and they go and if not, they take all my stock (Johannesburg Interview No. 1).

Confiscation of stock appears to be relatively common and the owners are forced to pay large fines to retrieve their goods. In many cases, the fines are so heavy that they simply abandon the goods, borrow money and begin again. Simply to be allowed to operate in an area for a day or to avoid impounding of goods may require payment of a bribe of up to ZAR 200. Mobile vendors play a continuous cat and mouse game with the police, ready to pack up their goods and disappear at the first sign of a police car. In sum, police protection cannot be counted on during episodes of mob violence and there is also very little redress when individuals report crimes against their businesses or themselves to the police. Fear of reprisals from those they report or identify is also a very real disincentive to getting the police involved. As a result, there is a certain fatalism and resignation to the inevitability of losing goods and property in general or isolated attacks.

Conclusion

Crush and Ramachandran (2015a) argue that there are three main policy and scholarly responses to violence against migrants in general, and migrant entrepreneurs in particular: xenophobia denialism (the official position of the South African government since 2008 and supported by some researchers who argue that South Africans are equally as vulnerable to violence as migrants); xenophobia minimalism (whose proponents suggest that xenophobia may exist but it is an epiphenomenon and that the real causes lie elsewhere) and xenophobia realism (which argues that xenophobia is not only widespread and real but can take a violent form in specific places and under certain circumstances). This paper revisits these arguments from the perspective of a group of migrants themselves, that is Zimbabweans running businesses in the informal economy. The migrants clearly have no difficulty in naming what happens to them as xenophobic. Nor do they hesitate, on the basis of first-hand experience, to name South Africans as the "owners of xenophobia." Their accounts clearly demonstrate that they see xenophobia as a key driver of the hostility, looting and violence that they experience. We suggest in this paper that xenophobic violence has several key and common characteristics that constantly put Zimbabwean informal enterprise owners at risk of losing their and their property. We also argue that the deep-rooted crisis in Zimbabwe, which has driven many to South Africa in the first place, makes return home in the face of xenophobia a non-viable option. Instead, Zimbabweans are forced to adopt a number of self-protection strategies, none of which are ultimately an insurance against attack.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the financial support of the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the EU-funded Migrants in Countries in Crisis (MICIC) Project.

References

Amit, R. and Kriger, N. 2014. Making migrants' il-legible': The policies and practices of documentation in post-apartheid South Africa. Kronos, 40: 269290. [ Links ]

Bekker, S. 2015. Violent xenophobic episodes in South Africa, 2008 and 2015. African Human Mobility Review, 1: 229-252. [ Links ]

Betts, A. 2013. Survival Migration: Failed Governance and the Crisis of Displacement. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Betts, A. and Kaytaz, E. 2009. National and International Responses to the Zimbabwean Exodus: Implications for the Refugee Protection Regime. UNHCR Research Paper No. 175, Geneva: UNHCR. [ Links ]

Blaauw, D., Pretorius, A. and Schenck, R. 2016. Day labourers and the role of foreign migrants: For better or for worse? Econ 3x3, May.

Cabane, L. 2015. Protecting the 'most vulnerable'? The management of a disaster and the making/unmaking of victims after the 2008 xenophobic violence in South Africa. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 9: 5671. [ Links ]

Charman, A. and Piper, L. 2012. Xenophobia, criminality and violent entrepreneurship: Violence against Somali shopkeepers in Delft South, Cape Town, South Africa. South African Review of Sociology, 43: 81-105. [ Links ]

Chikanda, A. and Tawodzera, G. 2017. Informal Entrepreneurship and Informal Cross-Border Trade Between Zimbabwe and South Africa. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 74, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J. 2008. The Perfect Storm: The Realities of Xenophobia in Contemporary South Africa. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 50, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Ramachandran, S. 2015a. Migration myths and extreme xenophobia in South Africa. In: Arcarazo, D. and Wiesbrock, A. (Eds.). Global Migration: Old Assumptions, New Dynamics. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Ramachandran, S. 2015b. Doing business with xenophobia. In: Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Ottawa: IDRC, pp. 25-59. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Tawodzera, G. 2017. South-South migration and urban food security: Zimbabwean migrants in South African cities, International Migration, 55(4): 88-102. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Tevera, D. (Eds.). 2010. Zimbabwe's Exodus: Crisis, Migration, Survival. Ottawa: IDRC and Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). 2015a. Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Ottawa: IDRC. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Tawodzera, G. 2015b. The third wave: Mixed migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 49: 363-382. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Ramachandran, S. and Pendleton, W. 2013. Soft Targets: Xenophobia, Public Violence and Changing Attitudes to Migrants in South Africa After May 2008. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 64, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Desai, A. 2015. Migrants and violence in South Africa: The April 2015 xenophobic attacks in Durban. Oriental Anthropologists, 15: 247-259. [ Links ]

Duri, F. 2016. From victims to agents: Zimbabweans and xenophobic violence in post-apartheid South Africa. In: Mawere, M. and Marongwe, N. (Eds.). Myths of Peace and Democracy? Bamenda: RPCIG. [ Links ]

Everatt, D. 2011. Xenophobia, state and society in South Africa, 2008-2010. Politikon, 38: 7-36. [ Links ]

Gastrow, V. 2013. Business robbery, the foreign trader and the small shop: How business robberies affect Somali traders in the Western Cape. SA Crime Quarterly, 43: 5-16. [ Links ]

Gastrow, V. and Amit, R. 2016. The role of migrant traders in local economies: A case study of Somali spaza shops in Cape Town. In: Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Ottawa: IDRC, [ Links ].

Harber, A. 2011. Diepsloot. Jeppestown: Jonathan Ball. [ Links ]

Hassim, S., Kupe, T. and Worby, E. (Eds.). 2008. Go Home or Die Here: Violence, Xenophobia and the Reinvention of Difference in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Hayem, J. 2013. From May 2008 to 2011: Xenophobic violence and national subjectivity in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 39: 77-97. [ Links ]

Hendow, M., Pailey, R. and Bravi, A. 2016. Migrants in Countries in Crisis: A Comparative Study of Six Crisis Situations. Report for International Centre for Migration Policy Development, Vienna: ICMPD [ Links ]

Hungwe, C. 2012. The migration experience and multiple identities of Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa. Journal of Social Research, 1: 132-138. [ Links ]

Hungwe, C. 2013. Surviving Social Exclusion: Zimbabwean Migrants in Johannesburg, South Africa. PhD Thesis. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Hungwe, C. 2014. Zimbabwean migrant entrepreneurs in Kempton Park and Tembisa, Johannesburg: Challenges and opportunities, Journal of Enterprising Culture, 22. [ Links ]

IOM 2012. Moving to Safety: Migration Consequences of Complex Crises. International Organization for Migration Report. Geneva: IOM. [ Links ]

Koser, K. 2014. Non-citizens caught up in situations of conflict, violence and disaster. In: Martin, S., Weerasinghe, S. and Taylor, A. (Eds.). Humanitarian Crises and Migration: Causes, Consequences and Responses. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kuljian, C. 2013. Sanctuary. Auckland Park: Jacana. [ Links ]

Landau, L. (Ed.). 2012. Exorcising the Demons Within:Xenophobia, Violence and Statecraft in Contemporary South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Lefko-Everett, K. 2010. The voices of migrant Zimbabwean women in South Africa. In: Crush, J. and Tevera, D. (Eds.). Zimbabwe's Exodus: Crisis, Migration, Survival. Ottawa: IDRC. [ Links ]

McAdam, J. 2014. Conceptualizing 'crisis migration': A theoretical perspective. In: Martin, S., Weerasinghe, S. and Taylor, A. (Eds.). Humanitarian Crises and Migration: Causes, Consequences and Responses. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Makina, D. 2010. Zimbabwe in Johannesburg. In: Crush, J. and Tevera, D. (Eds.). Zimbabwe's Exodus: Crisis, Migration, Survival. Ottawa: IDRC. [ Links ]

Martin, S., Weerasinghe, S. and Taylor, A. (Eds.). 2014. Humanitarian Crises and Migration: Causes, Consequences and Responses. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Misago, J-P., Freemantle, I. and Landau, L. 2015. Protection from Xenophobia: An Evaluation of UNHCR's Regional Office for Southern Africa's Xenophobia Related Programmes. Pretoria: UNHCR [ Links ]

Peberdy, S. 2016. International Migrants in Johannesburg's Informal Economy. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 71, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Perching, B. 2016. Actor and Stakeholder Involvement in Crisis Mitigation. MICIC Research Brief. Vienna: ICMPD. [ Links ]

Piper, L. and Charman, A. 2016. Xenophobia, price competition and violence in the spaza sector in South Africa. African Human Mobility Review, 2: 332-361. [ Links ]

Sibanda, O. and Sibanda. F. 2014. 'Land of opportunity and despair': Zimbabwean migrants in Johannesburg. Journal of Social Development in Africa, 29: 55. [ Links ]

Steinberg, J. 2012. Security and disappointment: Policing, freedom and xenophobia in South Africa. British Journal of Criminology, 52: 345-360. [ Links ]

Tawodzera, G., Chikanda, A., Crush, J and Tengeh, R. 2015. International Migrants and Refugees in Cape Town's Informal Economy. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 70, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Tevera, D. 2013. African migrants, xenophobia and urban violence in post-apartheid South Africa. Alternation, 7: 9-26. [ Links ]

Thebe, V. 2017. 'Two steps forward, one step back': Zimbabwean migration and South Africa's Regularising Programme (the ZDP). Journal of International Migration and Integration 18: 612-633. [ Links ]

Weerasinghe, S. and Taylor, A. 2015. On the margins: Noncitizens caught in countries experiencing violence, conflict and disaster. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 3: 26-57. [ Links ]