Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.2 Cape Town 2017

ARTICLES

Comparing Refugee and South African Migrant Enterprise in the Urban Informal Sector

Jonathan CrushI; Cameron McCordicII

IInternational Migration Research Centre, Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb St West, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada N2L6C2. Email address: jcrush@balsillieschool.ca

IIBalsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb St West, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada N2L6C2. Email address: cmccordic@balsillieschool.ca

ABSTRACT

Comparisons between the informal business operations of South Africans and international migrants are increasingly common. The conventional wisdom is that survivalist South Africans are being displaced by entrepreneurial migrants with a long tradition of informal enterprise. This paper is the first attempt to explicitly compare the informal enterprises established by refugees and South African migrants in urban areas. The paper is based on a comparative analysis of over 2,000 refugee and South African informal enterprises. The stereotyping of refugees in public discourse as undermining and destroying South African competitors is far-removed from the reality. The idea that refugees have a competitive advantage as experienced entrepreneurs is also clearly fallacious. Refugees are extremely motivated, hard-working and dedicated, and employ a number of legitimate business strategies to achieve success. To suggest, on the other hand, that South African migrants are poor business people is equally fallacious. While refugees seem able to access greater amounts of start-up capital (although neither they nor South Africans can access formal bank loans), both groups are seemingly able to grow their businesses. Thus, there is a need for much greater nuance in policy and academic discussions about the impact of refugee migration on the South African informal economy.

Keywords: Informal sector, business strategies, xenophobia, refugee entrepreneurs, South African migrant entrepreneurs.

Introduction

In 2014, South Africa's Minister of Small Business Development, Lindiwe Zulu, publicly compared South African and migrant informal entrepreneurs. She suggested that South Africans were largely inept business owners who should learn from the business practices of their foreign counterparts who were "better at running shops than the local owners" (Zwane, 2014). At the same time, South Africans were said to be at a natural disadvantage because they had no history of entrepreneurship. The reason for refugee success, she continued, is that business "is in their blood [...] from the moment they are born, they are introduced to trade. Their mothers, uncles, everyone trades." As a result, they "operate in the same communities in which we fail" (Zwane, 2014). Such stereotypical comparisons of refugee and South African informal business are echoed in the research literature. There is a common idea in the business literature, for example, that poor black South Africans lack entrepreneurial ambition and this, in turn, helps explain the relatively small size of the South African informal economy and the high rate of local informal business failure (Hutchinson & de Beer, 2013; Iwu et al., 2016; Ligthelm, 2011; Preisendörfer et al., 2012a, 2012b, 2014a, 2014b). This paper sets out to examine and contest the contrasting stereotypes that surround both South African and refugee entrepreneurs.

Comparisons between the informal business operations of South Africans and international migrants are increasingly common. The conventional wisdom is that "survivalist" South Africans in the informal economy are being displaced by "entrepreneurial" migrants (Charman et al., 2012). South Africans supposedly display a "survivalist mentality and one dimensional [business] strategy," leading to poorer performance than migrants (Basardien et al., 2014: 57). Comparing South African and Somali spaza shop owners in Cape Town, Basardien et al. (2014) found that the latter scored better on various indicators of entrepreneurial orientation, including achievement, innovation, personal initiative and autonomy. In addition, migrant businesses grew faster and created more jobs than South African businesses. By contrast, some have suggested that business failure is not inevitable and that South African survivalists can grow their enterprises and create jobs (Choto et al., 2014; Iwu et al., 2016). Other studies have suggested that the gap between South African and migrant entrepreneurs is not as great as is commonly supposed. One study of 500 retail enterprises in Gauteng for example, found that motivations to start a business did not differ significantly between South Africans and immigrants (Radipere, 2012; Radipere & Dhliwayo, 2014). Callaghan and Venter's (2011) study of street traders in inner-city Johannesburg concluded that South Africans were actually more innovative than migrants, although they did not display the same levels of proactiveness and competitive aggression. While migrant traders had earned more than their South African counterparts in 2008 and 2010, in 2009 the South Africans were the higher earners (Callaghan, 2013).

What is often overlooked in the public discourse and research literature about informal business competition between South Africans and non-South Africans is the fact that many South Africans in the informal economy are themselves migrants. By consistently representing business and other competition as a conflict between 'South Africans' and 'foreigners,' the fact that much of the supposed competition is between two groups of migrants is lost. Therefore, this paper aims to systematically compare a group of South African and non-South African migrant entrepreneurs and to assess the similarities and differences between them. The two groups are (i) refugees (holders of Section 24 permits) in Cape Town and Limpopo and (ii) South African migrants operating businesses in the same localities. The survey drew a sample of 1,068 South African migrant entrepreneurs and 1,008 refugee entrepreneurs (split approximately equally across the two locations of Cape Town and urban Limpopo). The maximum variation sampling methodology used to select the refugees for interview is explained in Crush et al. (2015). Exactly the same procedure was used to select the comparator group of South African informal business; that is, random selection of respondents within each area identified. For the purposes of this comparative analysis, we have combined the two sub-groups of refugees (in Cape Town and Limpopo) into one group and have done the same with the South Africans.

Motivating Entrepreneurship

South Africans and refugees appear to face very different livelihood prospects in the country's urban areas. Although South Africa does not have refugee encampment policy and refugees are permitted by law to pursue employment, there is much evidence to suggest that they face considerable barriers in accessing the formal labour market (Crea et al., 2016; Jinnah, 2010; Kavuro, 2015; Rugunanan & Smit, 2011). They have been shut out of the security industry (where many were initially employed) and they face considerable hurdles in getting employers to accept their documentation. South Africans, on the other hand, should theoretically have none of these problems but they face other hurdles including limited skills and training, job competition, and high rates of unemployment (currently around 30% nationally and as high as 45% amongst urban youth) (Graham & De Lannoy, 2016; Klasen & Woolard, 2009). South African migrants to the cities often end up living in informal settlements far from formal job opportunities, and also have to compete in the job market with long-time residents of the city who have a significant geographical and networking advantage. For both sets of migrants, then, the informal economy can often be the only livelihood niche they can find.

The general literature on informal entrepreneurship conventionally divides participants into survival (or necessity) entrepreneurs and opportunity entrepreneurs (Williams, 2007, 2015; Williams & Gurtoo, 2012; Williams & Youseff, 2014). The former are driven to participate purely by the need to survive and because they have no other choice. The latter choose to work in the informal sector because they see greater opportunities for economic advancement, they prefer to work for themselves rather than for others or they feel that they have the right aptitude. Distinguishing between these two types of entrepreneur and their likely differences in entrepreneurial motivation and orientation has generated a large body of empirical and methodological literature. In the South African context, studies of entrepreneurial motivation have sought to go beyond the idea of survivalism and demonstrate that many participants in the informal economy are not driven there out of desperation but are highly motivated entrepreneurs (Callaghan & Venter, 2011; Fatoki & Patswawairi, 2012; Khosa & Kalitanyi, 2015; Venter, 2012).

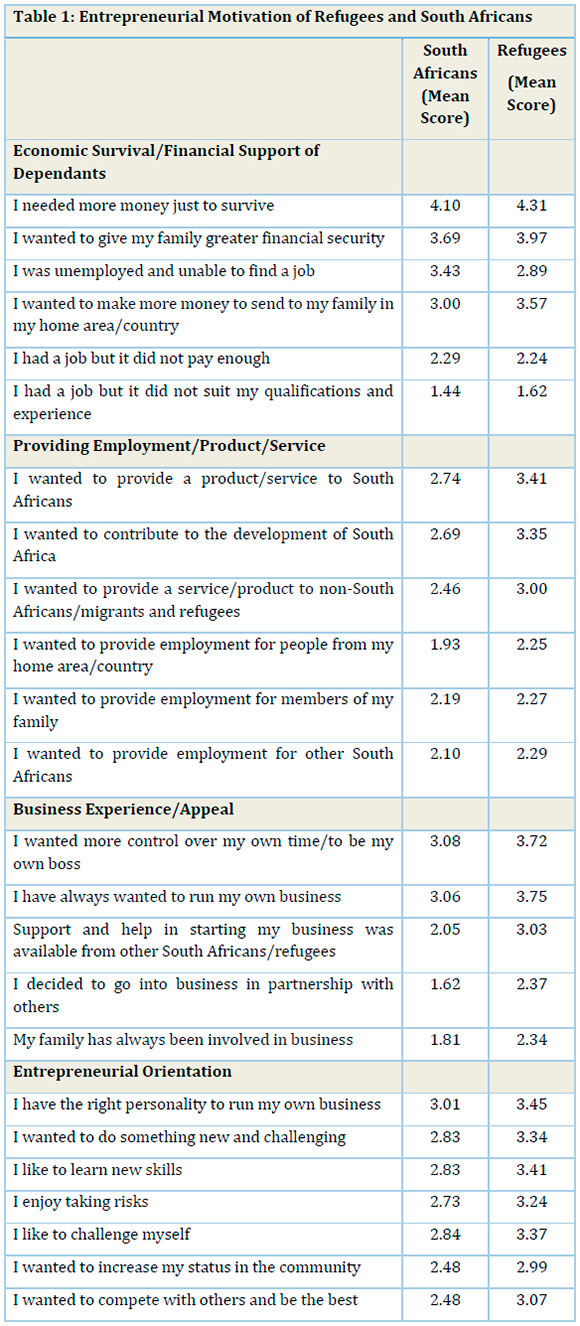

One of the most common ways of deciding what lies behind personal decisions to establish an informal enterprise is to measure what is known as entrepreneurial motivation. This involves the development of possible reasons why the informal enterprise was started and then asking respondents to rank them on a Likert scale from 1 (no importance) to 5 (extremely important). In this study, both refugees and South African migrants were presented with 24 different possibilities to rate. A mean score was calculated for each group on each statement (Table 1). For ease of interpretation, we have grouped the 24 statements under 4 main themes (a) economic survival; (b) provision of employment or a service to others; (c) business experience and appeal and (d) entrepreneurial orientation. Two things immediately stand out from a descriptive comparison of means. First, both refugees and migrants tend to assign the same relative importance to each of the 24 factors, which might suggest that they have a similar motivational profile, rating the same factors as relatively important and unimportant. The second notable finding is that almost across the board, even on statements that had a low mean score, refugees scored more highly than South African migrants. This could indicate a greater general degree of commitment to participation in the informal economy amongst refugees.

Significantly, the only two reasons for entrepreneurship on which South Africans scored higher than refugees were "I was unemployed and unable to find a job" and "I had a job but it did not pay enough." This suggests that for South African migrants, informal sector participation is more closely tied to the absence of formal employment than it is for refugees. Of the four groups of factors, economic survival motivations scored most highly for both groups, and providing an employment or service was the least important. The highest single factor for both groups was the need for more money to survive (both with means over 4.0). Also very important for both was the desire to provide family with greater financial security and the desire to make more money to remit to family at home. In other words, financial support of dependants is a strong motivating factor for informal sector entrepreneurship. Neither group was highly motivated by a desire to provide employment for others, but refugees were ironically much more likely to be motivated by a desire to provide a service or product to South Africans (3.41 versus 2.74) and to contribute to the development of South Africa (3.35 versus 2.69).

Although both groups said that wanting to run their own business and be their own boss was important to them, the refugees scored significantly higher on both factors. One of the major differences between the two was the amount of help and support they could count on from others, with refugees scoring much higher than South Africans (3.03 versus 2.05). Refugees were also consistently more positive about their personal aptitude for running a business. This is clear in the grouping of entrepreneurial orientation factors where refugees scored above 3.0 on 6 of the 7 factors, compared to South Africans who scored above 3.0 on only 1 of the 7 factors.

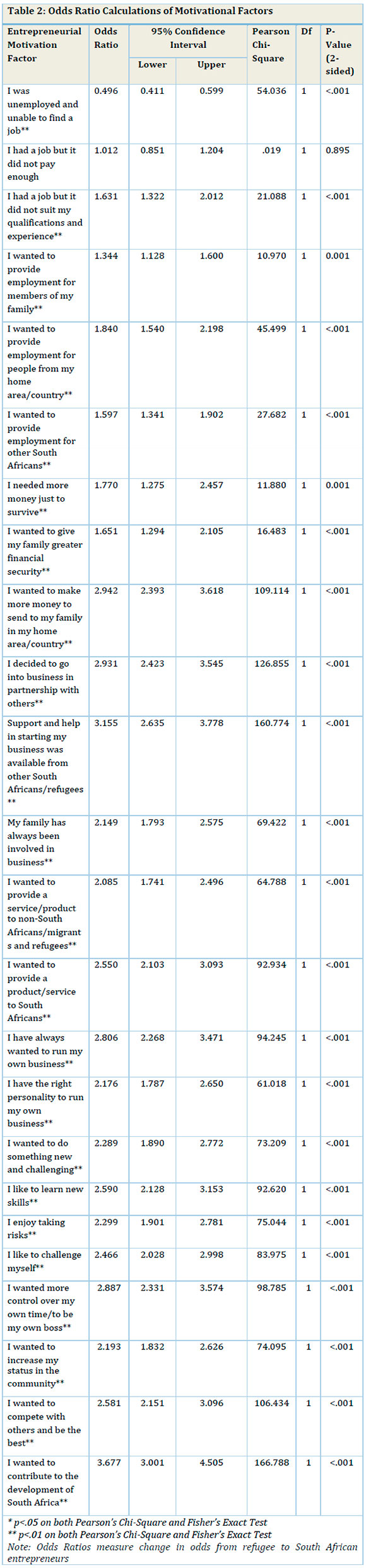

While these frequency distributions tell an interesting story about the differences and similarities between South African migrant and refugee entrepreneurs, it is difficult to gauge their statistical significance. The main challenge is that the dependent variable for the comparison (the importance ranking for each variable) is at an ordinal level of measurement with varying distributions across each sampled group. This means that we need to use non-parametric tests of difference and bin the motivation factors into binary level indicators. Each indicator was therefore assigned two values: not important (1 in the original scale) and important (2-5 in the original scale). A combination of odds ratio calculations and Pearson's Chi-Square Test of independence were used to test for significance. The odds ratio calculations show how migrant status is associated with a change in the odds of ranking each motivation factor (where a value greater than 1 indicates increased odds and less than 1 indicates decreased odds). These calculations are supported by 95% confidence intervals and the p-values taken from a Chi-Square analysis (where an alpha of 0.05 is used as a threshold for a statistically significant difference in the distribution of scores across the two groups) (Table 2).

The major conclusions from the analysis are as follows: first, refugee entrepreneurs have about 50% lower odds of starting their business because of being unable to find a job. Second, refugees had four times the odds of desiring to contribute to the development of South Africa and three times the odds of stressing the importance of obtaining help from others in starting their business and going into partnership with others. Third, refugees had nearly three times the odds of starting a business with the intention of remitting money to family at home. Finally, refugees had two to three times the odds of assigning importance to the range of personal entrepreneurial orientation factors.

Contrasting Business Profiles

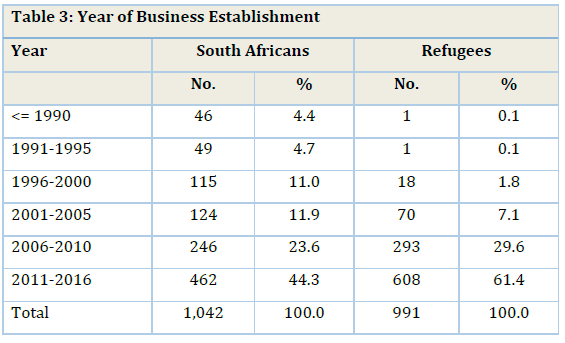

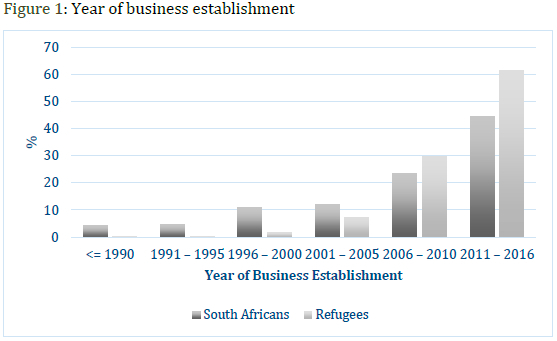

The survey highlighted a number of similarities and differences in the informal business activities of refugee and South African migrant enterprises. Firstly, more South Africans had been in business for a longer period of time (Table 3 and Figure 1). For example, 19% of the South African businesses were established before 2000, compared to only 2% of the refugee businesses. However, the majority of all businesses were started in the last decade, with 61% of refugee businesses and 44% of South African businesses established after 2010. This finding is certainly consistent with the general perception that refugees have been entering the informal economy in growing numbers.

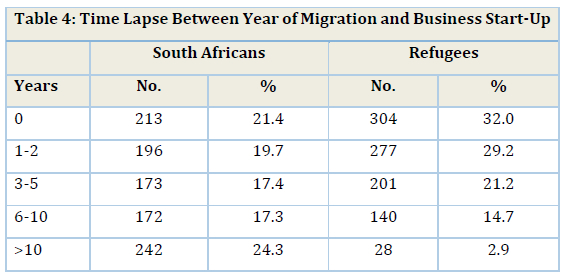

Second, since both groups are migrants to the city, it is important to see if they go into business as soon as they arrive or if business start-up comes at a later time. Only 32% of refugees and 21% of South Africans started a business within the first year of arrival (Table 4). This general pattern of a greater time lapse on the part of the South Africans is further demonstrated by the fact that 41% of them started their business within two years of arrival, compared to 61% of the refugees. Both groups have similar numbers who waited 3 to 10 years, but starting a business after 10 years or more was definitely a South African preserve (at 24% compared to 3% of refugees). The general time lapse in both groups indicates that immediate start-up is not an option for most. Rather, both tend to work first in the formal or informal economy, often to raise the start-up capital to branch out on their own.

Third, it is theoretically possible that the shorter time-lag between migration and start-up amongst refugees is also because they have prior business experience. This would certainly be consistent with the views of Minister Zulu summarised at the beginning of this paper (Zwane, 2014). The respondents were all asked what their main occupation was prior to leaving their home country or area. Only 9% of the South Africans said they were operating their own informal sector business. The figure for refugees was higher, at 18%, but this does not suggest a massive competitive advantage conferred by prior experience. In other words, over 80% of the refugee entrepreneurs were not operating an informal sector business prior to migrating to South Africa. The stereotypical idea that refugees somehow have business "in their blood" is, therefore, not supported by the evidence of this survey.

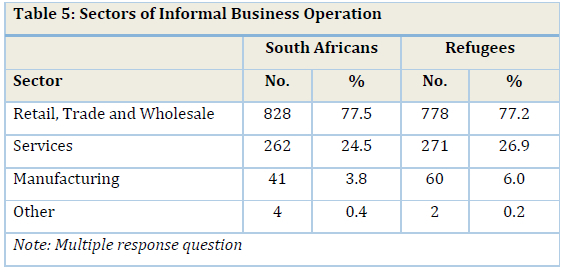

Fourth, the survey found that the majority of enterprises of both refugees and South African migrants are located in the retail sector (Table 5). A small number of businesses (9% of refugees and 6% of South Africans) are involved in more than one sector; for example, a business that manufactured and sold arts and crafts would count as both a retail and manufacturing enterprise. Or a business offering a service, such as a hair salon, may also be involved in retailing products. At this sectoral level of analysis, it appears that there is potential for significant intra-sectoral competition between the two groups. However, if the activity profile is disaggregated, the picture is more nuanced (Table 6).

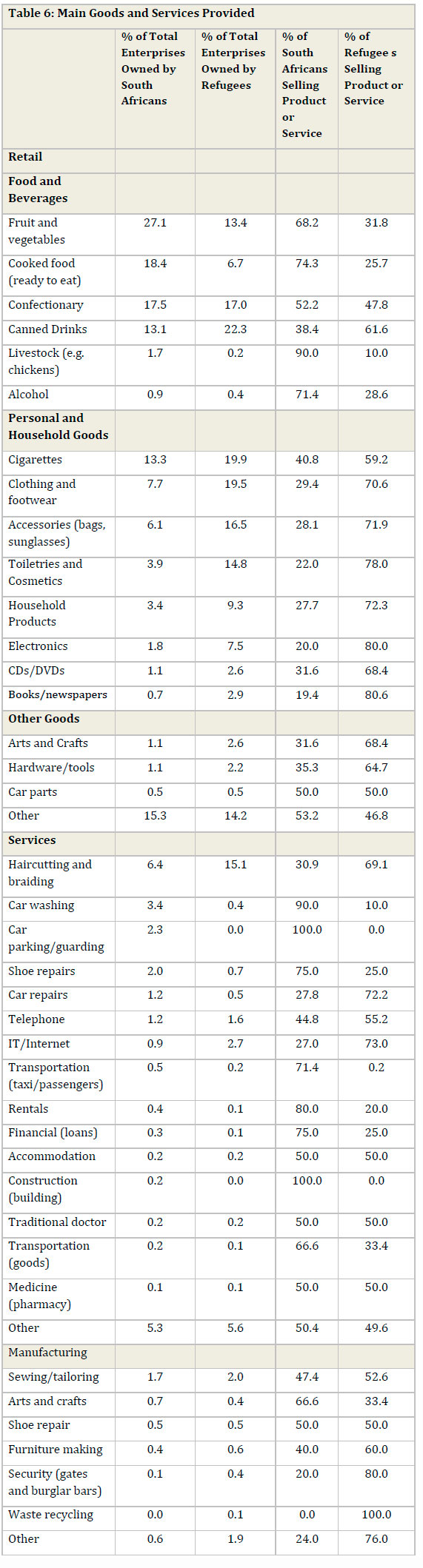

Table 6 shows that at least some South Africans and refugees are involved in every activity. However, they also tend to occupy and dominate different niches. South Africans are more strongly represented in food retail (the main exception being confectionary and the sale of canned drinks with roughly equal participation). Around 70% of the entrepreneurs who were selling fresh produce and cooked food were South Africans. On the other hand, over 70% of those selling most types of personal and household products were refugees. In the service sector, refugees dominate hair cutting and braiding, as well as car repairs and IT. South Africans tend to dominate shoe repairs, transportation and car washing and guarding. In the manufacturing sector, there is less differentiation, although the overall numbers of participants are small compared with retail and services.

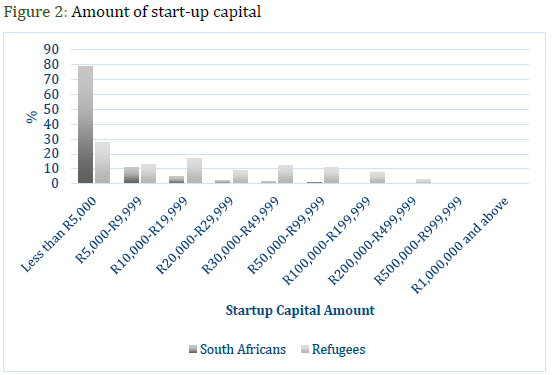

Fourth, there was a significant difference in the amount of start-capital used by the two groups (Figure 2). Almost 80% of the South Africans started their businesses with less than ZAR 5,000, while the equivalent figure was only 27% for refugees. At the other end of the spectrum, only 6% of the South Africans had start-up capital of more than ZAR 20,000, compared to 43% of the refugees. This certainly suggests that refugees have access to greater amounts of start-up capital but it may also be that the barriers to entry are much lower in the food sector (which is dominated by South Africans) as the initial spend on stock is likely much lower than for businesses selling personal and household goods. It is significant that of the 28% of refugees who started with less than ZAR 5,000, most were food retailers.

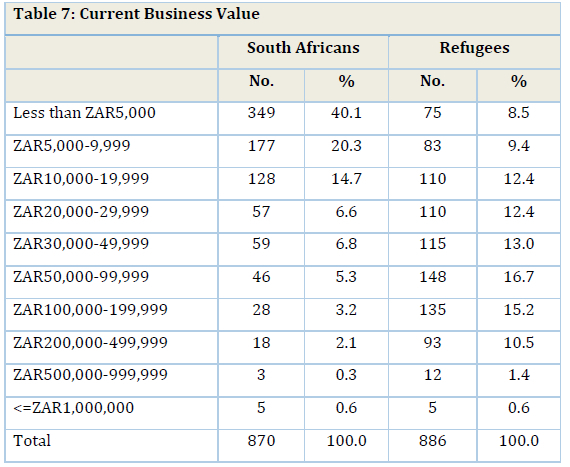

Fifth, both groups had added value to their businesses since start-up (Table 7). For example, while 78% of South Africans started with less than ZAR 5,000, only 40% valued their enterprise as still less than ZAR 5,000 (a fall of 28%). Similarly, with refugees the equivalent figures were 28% and 9% (a fall of 19%). The proportion of South African businesses with a current value of over ZAR 20,000 was 25% (compared to only 6% at start-up). In the case of refugees, the equivalent figures were 70% and 43%). In other words, 19% of South Africans and 27% of refugees had moved up into the highest value bracket.

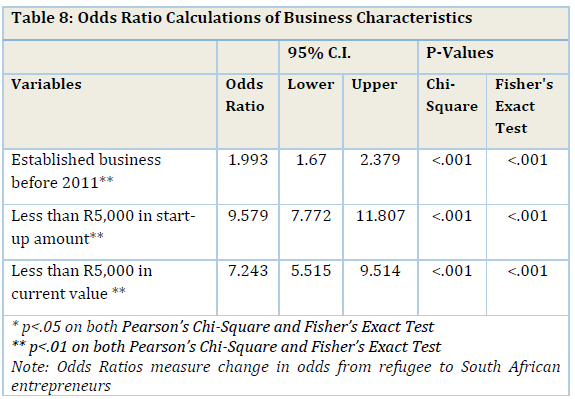

To assess the statistical significance of these differences, key variable comparisons were drawn out from the frequency distributions and binned into binary-level variables. These included (a) year of establishment (<=2010 and > 2010); (b) start-up capital (<ZAR 5,000 and >ZAR 5,000); and (c) current business value (<ZAR 5,000 and >ZAR 5,000). The odds ratio calculations performed in Table 8 provide convergent validity for the observed frequency distributions. Independent of the influence of any other variables, the South African entrepreneurs had almost twice the odds of running a business established before 2011, almost ten times the odds of starting a business with less than ZAR 5,000 and almost seven times the odds of currently running a business valued at less than ZAR 5,000. All of these comparisons yielded p-values less than the alpha of 0.01 on both the Pearson's Chi-Square Test and the Fisher's Exact Test.

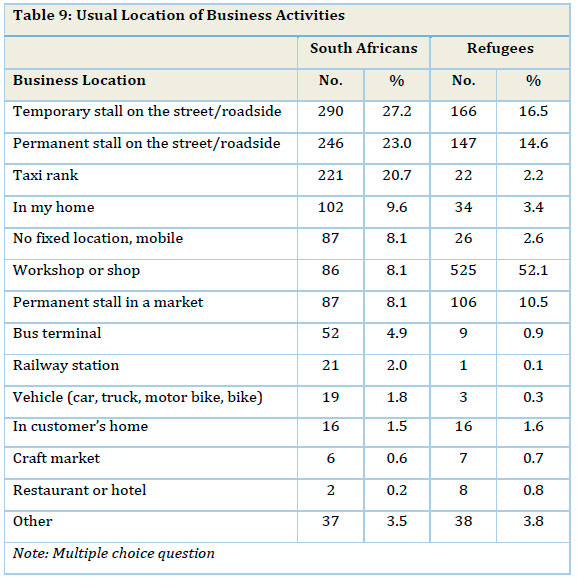

Business Strategies

Given the official and business literature perception that non-South Africans are much better at running businesses than their South African counterparts, it is important to see if the two groups pursue different business strategies and activities. The first point of comparison concerns where the two groups choose to locate their business operations. In the case of Cape Town, there are areas of the city where each group tends to dominate: refugee businesses are more common in the CBD and Bellville, for instance, while South Africans are more commonly located along transport routes in and out of the city (such as on streets and at taxi ranks and bus terminals). This difference is clear from Table 9. Half of the South Africans operate stalls on roadsides and 21% operate at taxi ranks. This compares with only 31% and 2% of refugees, respectively. The other major difference is that half of the refugees operate from a fixed shop or workshop, compared to only 8% of the South Africans.

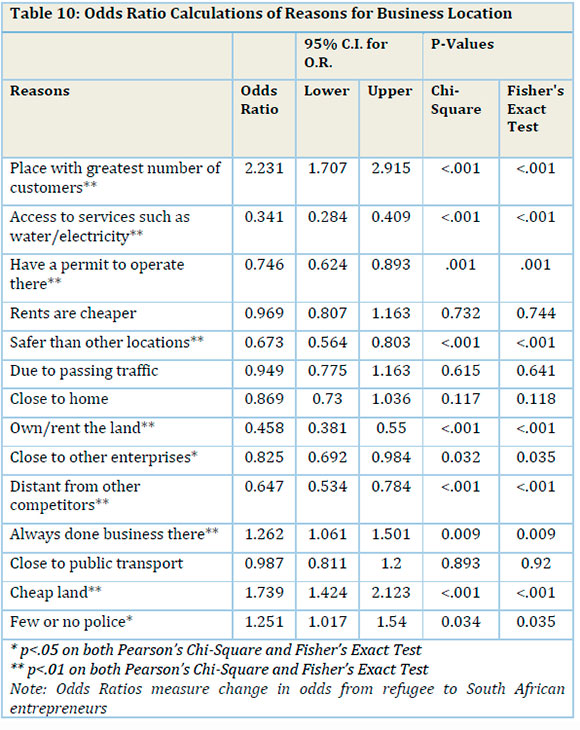

In addition to the observed variations in business location, the reasons for locational decisions also varied between the two groups (Table 10). When compared with the refugee entrepreneurs, the South African migrant entrepreneurs had greater odds of choosing a business location based on it having the greatest number of customers, the tradition of doing business in a location, the cheapness of land and a limited number of police in the area. The refugees had higher odds of choosing their business location based on the other locational factors, especially access to services, property rentals, safety concerns and distance from other competitors.

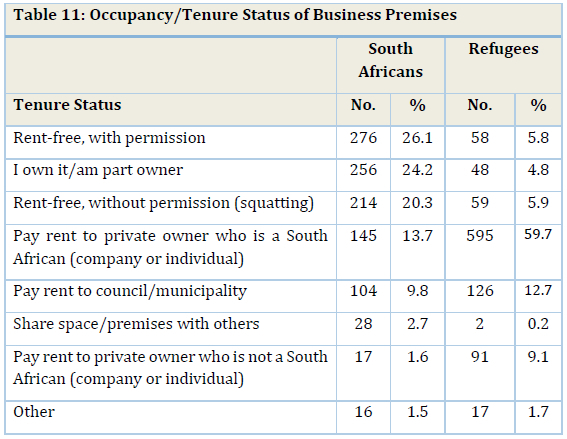

Refugee entrepreneurs were much more likely than South Africans to rent their business premises (Table 11). Almost 60% of them paid rent to a South African landlord. Another 13% paid rent to the municipality (as did 10% of the South Africans). Nearly 50% of South Africans operated their businesses rent-free (compared to only 5% of refugees). What this means, in effect, is that around three-quarters of South Africans do not pay any rent for their premises, while over 80% of refugees do. The refugee entrepreneurs also pay a higher monthly rent, on average, than those South Africans who do pay rent (ZAR 4,000 per month versus ZAR 2,820 per month). In effect, many South Africans are able to augment their household income through renting business premises to refugees and therefore benefit from their presence.

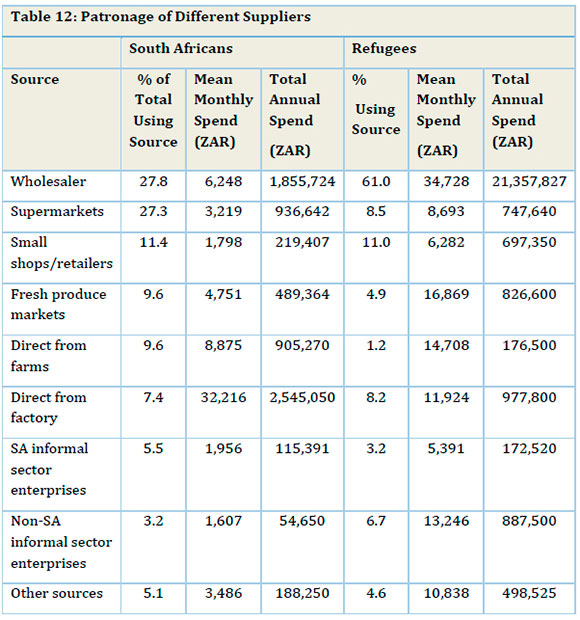

Another area of business strategy comparison concerns where the two groups source their goods and whether they tend to patronise the same outlets (Table 12). Most of the respondent refugees buy their supplies at wholesalers while South Africans patronise wholesalers and supermarkets in almost equal numbers. South African respondents also obtain goods from fresh produce markets and direct from farms in greater numbers. With the exception of factory purchase, refugees tend to spend more on average at all outlets. For example, while fewer refugees patronise supermarkets, their average monthly spend is ZAR 8,693 compared with only ZAR 3,219 by the South Africans. In total, the South African respondents spend more than the refugees at supermarkets, fresh produce markets and buying direct from farms. Refugees spend five times as much on average at wholesalers and a great deal more in total (ZAR 21 million compared to less than ZAR 2 million).

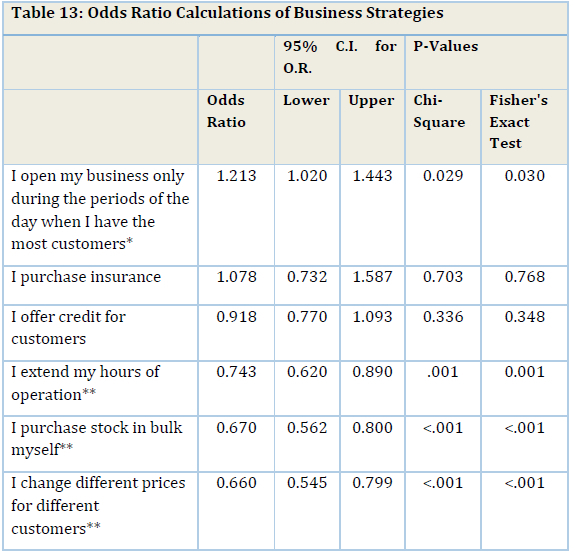

There is a common assumption that other strategies adopted by refugees give them a strong competitive advantage over South Africans. In addition to greater business acumen and skills, they have been viewed, inter alia, as securing discounts through group purchasing, offering credit to consumers, operating for longer hours and selling goods more cheaply. Statistical comparison of these, and other, business strategies indicates their relative importance to each group (Table 13). The refugees had lower odds of adjusting their operating hours to times of the day when there were most customers and purchasing insurance. South African migrant entrepreneurs had lower odds of operating for extended hours (0.743) and individual bulk purchasing (0.67). However, they were two to five times as likely to keep business records (0.475), sell goods more cheaply than competitors (0.395), purchase in bulk with others (0.244) and negotiate with suppliers (0.340).

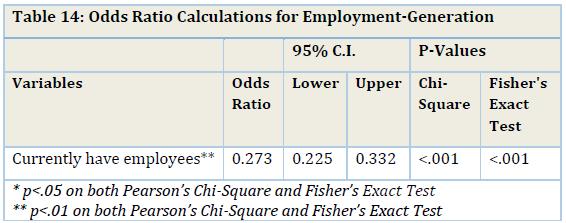

The final point of business strategy comparison concerns the hiring practices of the two groups of entrepreneurs. Almost half of the refugee entrepreneurs have paid employees compared to only 21% of the South Africans. The refugees in this sample provided three times as many jobs as the South Africans. Table 14 provides statistical confirmation of the greater employment-generating potential of refugees using odds ratio, Chi-Square and Fisher's Exact Test calculations.

A breakdown of employees by sex and national origin shows some differences in the hiring patterns of the two groups. In total, 9% of refugees hire South African men full-time and 1% part-time. The equivalent figures for South African enterprises are 8% and 4%. Refugees show a preference for hiring South African women over men, with 16% employing women full-time and 4% part-time (compared to 9% and 1% for men). In the sample as a whole, 30% are South Africans employed by refugees and 28% are South Africans employed by other South Africans.

This suggests that both refugee and South African enterprises create jobs for South Africans in roughly equal numbers. The major difference is in the employment of non-South Africans. Less than 5% of the total number of employees are non-South Africans employed by South Africans, whereas 39% are non-South Africans employed by refugees.

Conclusion

This paper is the first attempt to explicitly compare the informal enterprises established by different categories of migrant in South African urban areas.

This comparative analysis of refugees and internal migrants suggests that there is a need for much greater nuance in policy and academic discussions about the impact of refugee migration on the South African informal economy. The stereotyping of refugees in public discourse as undermining and destroying South African competitors is clearly far-removed from the reality. While refugees seem able to access greater amounts of start-up capital (although neither they nor South Africans can access formal bank loans), both groups are seemingly able to grow their businesses. This is partly because they tend to occupy different niches in the informal economy, with South Africans focused more on the food sector and refugees focused more on services and retailing household goods. This may help explain another difference between the two, with refugees tending to patronise wholesalers for their supplies and South Africans purchasing from supermarkets and fresh produce markets.

The idea promulgated by the South African Minister of Small Business Development, that refugees have a competitive advantage as experienced or "in their blood" entrepreneurs, is clearly fallacious. South Africa's refugee legislation and restrictive employment policies mean that working for, and then establishing, an informal enterprise is virtually the only available livelihood option. But to argue that refugees come to South Africa with a preexisting skill and business experience is misplaced. Instead, refugees (like small business owners everywhere) are extremely motivated, hard-working and dedicated. They employ a number of business strategies to achieve monetary success, although business expansion is hampered by the fact that only a portion of business profits can be reinvested in the business as the rest go to support dependants in South Africa and the home country. These strategies are not illegal or even underhand but are quite transparent and could be emulated. To suggest, on the other hand, that South African migrants are poor business people, as the minister also suggested, is just as fallacious. It is true that the odds of refugees pursuing a particular strategy (such as giving goods on credit) are generally higher than a South African doing so, but this does not mean that no South Africans pursue the strategy, as many clearly do. Instead of constantly pitting refugees against South Africans as the official mind likes to do, it would be more productive to treat them in policy terms as a single group attempting, often against considerable odds, to establish and grow a small business in a hostile or indifferent economic and political environment.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the UNHCR in Geneva for funding the Refugee Economic Impacts SAMP research project on which this paper is based.

References

Basardien, F., Parker, H., Bayat, M., Friedrich, C. and Sulaiman, A. 2014. Entrepreneurial orientation of spaza shop entrepreneurs: Evidence from a study of South African and Somali-owned spaza shop entrepreneurs in Khayelitsha. Singaporean Journal of Business Economics and Management Studies, 2: 45-61. [ Links ]

Callaghan, C. 2013. Individual values and economic performance of inner-city street traders. Journal of Economics, 4: 145-156. [ Links ]

Callaghan, C. and Venter, R. 2011. An investigation of the entrepreneurial orientation, context and entrepreneurial performance of inner-city Johannesburg street traders. Southern African Business Review, 15: 28-48. [ Links ]

Charman, A., Petersen, L. and Piper, L. 2012. From local survivalism to foreign entrepreneurship: The transformation of the spaza sector in Delft, Cape Town. Transformation, 78: 47-73. [ Links ]

Choto, P., Tengeh, R. and Iwu, C. 2014. Daring to survive or to grow? The growth aspirations and challenges of survivalist entrepreneurs in South Africa. Environmental Economics, 5: 93-101. [ Links ]

Crea, T., Loughry, M., O'Halloran, C. and Flannery, G. 2016. Environmental risk: Urban refugees' struggles to build livelihoods in South Africa. International Social Work, 60: 667-682. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Ramachandran, S. and Pendleton, W. 2013. Soft targets: Xenophobia, public violence and changing attitudes to migrants in South Africa after May 2008. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 64, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Chikanda, A. eds., 2015. Mean streets: Migration, xenophobia and informality in South Africa. Southern African Migration Programme.

Fatoki, O. and Patswawairi, T. 2012. The motivations and obstacles to immigrant entrepreneurship in South Africa. Journal of Social Science, 32: 133142. [ Links ]

Graham, L. and De Lannoy, A. 2016. Youth unemployment: What can we do in the short run? From <http://bit.ly/2hHMtd9>.

Hutchinson, M. and de Beer, M. 2013. An exploration of factors that limit the long-term survival and development of micro and survivalist enterprises: Empirical evidence from the informal economy in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4: 237-245. [ Links ]

Iwu, C., Gwija, S., Tengeh, R., Cupido, C. and Mason, R. 2016. The unique role of the survivalist retail entrepreneur in job creation and poverty reduction: Implications for active stakeholder participation. Acta Universitatis Danubius (Economica), 12: 16-37. [ Links ]

Jinnah, Z. 2010. Making home in a hostile land: Understanding Somali identity, integration, livelihood and risks in Johannesburg. Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 1: 91-99. [ Links ]

Kavuro, C. 2015. Refugees and asylum seekers: Barriers to accessing South Africa's labour market. Law, Democracy and Development, 19: 232-260. [ Links ]

Khosa, R. and Kalitanyi, V. 2015. Migration reasons, traits and entrepreneurial motivation of African immigrant entrepreneurs: Towards an entrepreneurial migration progression. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 9: 132-155; [ Links ]

Klasen, S. and Woolard, I. 2009. Surviving unemployment without state support: Unemployment and household formation in South Africa. Journal of African Economies, 18: 1-51. [ Links ]

Ligthelm, A. 2011. Survival analysis of small informal businesses in South Africa, 2007-2010. Eurasian Business Review, 1: 160-179. [ Links ]

Preisendörfer, P., Bitz, A. and Bezuidenhout, F. 2012a. Business start-ups and their prospects of success in South African townships. South African Review of Sociology, 43: 3-23. [ Links ]

Preisendörfer, P., Bitz, A. and Bezuidenhout, F. 2012b. In search of black entrepreneurship: Why is there a lack of entrepreneurial activity among the black population in South Africa. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 17: 1-18. [ Links ]

Preisendörfer, P., Perks, S. and Bezuidenhout, F. 2014a. Do South African townships lack entrepreneurial spirit? International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 22: 159-178. [ Links ]

Preisendörfer, P., Bitz, A. and Bezuidenhout, F. 2014b. Black entrepreneurship: A case study on entrepreneurial activities and ambitions in a South African township. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 8: 162-179. [ Links ]

Radipere, N. 2012. An Analysis of Local and Immigrant Entrepreneurship in the South African Small Enterprise Sector (Gauteng Province). PhD Thesis, Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Radipere, S. and Dhliwayo, S. 2014. An analysis of local and immigrant entrepreneurs in South Africa's SME sector. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5: 189-198. [ Links ]

Rugunanan P. and Smit, R. 2011. Seeking refuge in South Africa: Challenges facing a group of Congolese and Burundian refugees. Development Southern Africa, 28: 705-718. [ Links ]

Venter, R. 2012. Entrepreneurial values, hybridity and entrepreneurial capital: Insights from Johannesburg's informal sector. Development Southern Africa, 29: 225-239. [ Links ]

Williams, C. 2007. Entrepreneurs operating in the informal economy: Necessity or opportunity driven? Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 20: 309-320. [ Links ]

Williams, C. 2015. Explaining the informal economy: An exploratory Evaluation of competing perspectives. Industrial Relations, 70: 741-765. [ Links ]

Williams, C. and Gurtoo, A. 2012. Evaluating competing theories of street entrepreneurship: Some lessons from a study of street vendors in Bangalore, India. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8: 391-409. [ Links ]

Williams, C. and Youssef, Y. 2014. Is informal sector entrepreneurship necessity- or opportunity-driven? Some lessons from urban Brazil. Business and Management Research, 3: 41-53. [ Links ]

Zwane, T. 2014. Spazas: Talking Shop is Good for Business. Mail & Guardian, November 6, 2014.