Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.2 Cape Town 2017

ARTICLES

Refugee Entrepreneurial Economies in Urban South Africa

Jonathan CrushI; Godfrey TawodzeraII; Cameron McCordicIII; Sujata RamachandranIV; Robertson TengehV

IInternational Migration Research Centre, Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb Street W, Waterloo, ON, N2L 6C2. Email: jcrush@balsillieschool.ca

IIDepartment of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Limpopo, P. Bag X1106, Sovenga

IIIBalsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb Street W, Waterloo, ON, N2L 6C2

IVSouthern African Migration Programme, International Migration Research Centre, Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb St West, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada N2L6C2

VFaculty of Informatics and Design, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The case-study literature on refugees and asylum-seekers in South Africa is dominated by an overwhelming focus on the problems they face and their marginalised existence, reinforcing an image of victimhood, exploitation and vulnerability. In this paper, we seek to broaden the image of refugees and their economic impacts beyond a narrow focus on their marginal status and vulnerable position. They are viewed here as dynamic agents with skills and capabilities who can play an integral role in transforming local settings and contributing to economic development. This paper presents and discusses the results of a survey of over 1,000 refugee informal business-owners in Cape Town and small-town Limpopo. As well as providing new insights into the nature, achievements and challenges of refugee entrepreneurship, the paper addresses the question of whether geographical location makes a difference to the nature of refugee entrepreneurial economies by contrasting the two groups of entrepreneurs. Refugee entrepreneurs are more vulnerable to xenophobic violence in Cape Town and to police misconduct in Limpopo. Otherwise, there are remarkable similarities in the manner in which refugee entrepreneurs establish and grow their businesses in large cities and small provincial towns.

Keywords: Refugees, informal sector, entrepreneurial economies, xenophobia, Cape Town, Limpopo.

Introduction

More than 60% of the world's refugees now live in urban areas, according to the UNHCR. Therefore, the social and economic impacts of refugee movements are increasingly being felt in the towns and cities of host nations. In general, the presence of refugees among urban populations is more likely to be assessed in terms of perceived burdens rather than benefits (Omata & Weaver, 2015). Only recently has interest emerged in what has been characterised by Jacobsen (2005) as the positive "economic lives of refugees." Some researchers have adopted the notion of "refugee economies" to highlight the strong involvement of refugees in the many overlapping processes of production, consumption, exchange, entrepreneurship and development of financial and capital markets in host countries and beyond (Betts et al., 2014). However, it would be a mistake to imagine that there are discrete spatially and economically isolated "refugee economies" in the urban environment. Refugees may dominate particular economic and geographical niches in the urban economy but they continuously interact with and contribute to that economy in ways that are poorly understood. As refugees increasingly become the norm in the urbanising Global South, more research on the specifically urban economic impacts of protracted refugee situations is therefore urgently needed (Koizumi & Hoffstaedter, 2015).

This paper aims to contribute to recent literature that takes "refugee livelihoods" as its point of departure (Buscher, 2011; Jacobsen, 2006; Omata & Kaplan, 2013; de Vriese, 2006). A livelihoods perspective underscores the need to adopt a rights-based approach to the economic activities of forced migrants; to identify their resources, assets and skills; and to understand how they respond to their situations and secure their livelihood needs. This perspective represents a move away from welfare-centred models of engagement focused on meeting basic needs, towards a capability approach which emphasises refugees' agency, right to choose and ability to control their own environments (Landau, 2008). Identifying the economic advantages and benefits associated with the presence of refugees is a key precondition for making governments and local elites more responsive to refugee needs and removing the barriers they face (Lyytinen & Kullenberg, 2013). This objective coheres with the UNHCR's (2014) Global Strategy for Livelihoods, which underscores the need to enhance the economic capabilities of refugee populations and build on their own resilience.

The sizable case-study literature on refugees and asylum-seekers in South Africa is dominated by an overwhelming focus on the problems they face and their marginalised existence, reinforcing an image of victimhood, exploitation and vulnerability (Crush & Chikanda, 2014). In recent years, a more troubling image has emerged of refugees as unfair and underhand competitors who disadvantage poor South Africans (Desai, 2008; Gordon, 2016). Both characterisations suffer from obvious problems. The former treats them in a restricted manner as undifferentiated, homogeneous populations defined by their marginalised status as recipients of protection in the host country. The latter views them in a prejudicial manner through a warped understanding of the nature of economic competition and refugee rights. Undue emphasis on their legal standing as 'refugees' tends to minimise their education, credentials and work experience in various fields. Furthermore, it underestimates their creative energies, determination and ability to overcome some of these challenges and re-build their lives in South Africa.

Post-apartheid South Africa has relied on a "self-settlement" approach to refugees (Handmaker et al., 2011). The country imposes no restrictions on freedom of movement and the geographical locations where refugees can reside. They are not confined to refugee camps or physically separated from citizens, which means they have direct interaction with South Africans with the potential for both conflict and integration into local communities. However, the South African self-settlement model does emphasise self-sufficiency on the part of refugees in the process of resettlement, with little assistance from state authorities (Polzer Ngwato, 2013). Existing studies suggest that many urban refugees are unable, for various reasons, to access formal employment in the cities and turn to the informal economy for their livelihoods (Achiume, 2014; Jacobsen, 2006; Kavuro, 2015). Employment or self-employment in the informal economy becomes a desirable option, if not a necessity. Because urban informality is generally invisible to policy-makers, scorned by politicians and seen as a site of desperation rather than opportunity, its economic significance is often overlooked (Pavanello et al., 2015; Williams, 2013).

The primary aim of this paper is to examine what we call "refugee entrepreneurial economies" in urban South Africa. The paper builds on casestudy evidence on the activities of refugees in the South African informal economy (Greyling, 2015; Jinnah, 2010; Owen, 2015; Smit & Rugunanan, 2014; Thompson, 2016; Zack, 2015). Within the informal sector, refugee economies have often been viewed as stagnant pools of desperation, providing narrow opportunities and limited scope for advancement. But this is a misleading characterisation. It is important to recognise the dynamism and growing complexity of South African refugee economies and to re-shape our ideas about the economic impacts of the informal sector (Roever & Skinner, 2016). The important question is whether all forms of refugee activity in the informal sector are associated with economic precariousness and social marginality, or whether possibilities for real economic advancement exist (Crush et al., 2015a).

In this paper, we seek to broaden the image of refugees and their economic impacts beyond a narrow focus on their marginal status and vulnerability. We view them as dynamic agents with skills and capabilities who can play an integral role in transforming local settings and contributing to economic development. This is not to undervalue the divergent ways through which refugees earn a living in South Africa, nor to gloss over their struggles and the pervasive discrimination, hostility and xenophobic violence they regularly encounter, nor to exaggerate the significance of refugee entrepreneurship. However, there is a need to re-calibrate the narrow, partial and negative lens through which their economic potential is evaluated by politicians and policymakers. Here, we also address the question of whether geographical location makes a difference to the nature of refugee entrepreneurial economies by contrasting refugee enterprise in a major South African city (Cape Town) with that in several smaller towns in a different part of the country (Limpopo Province). Our aim is to ascertain whether geography matters in framing the activities, challenges and impacts of refugee entrepreneurial economies.

Methodology

Most refugees are initially drawn to the major South African cities of Johannesburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town. In this study of refugee entrepreneurship, the city of Cape Town was chosen as one of two study sites because there is a significant concentration of refugees and a contextual literature on refugee entrepreneurship in the city (Basardien et al., 2014; Gastrow & Amit, 2013, 2015; Owen, 2015; Tawodzera et al., 2015). In recent years, refugee entrepreneurs have also been establishing businesses in smaller urban areas around the country. In 2012, a police campaign called Operation Hardstick in Limpopo Province forcibly closed as many as 600 small businesses run by migrants and refugees, suggesting that this province had become a significant operating location for small-town entrepreneurs. In contrast to Cape Town, however, very little research exists on refugee livelihoods and entrepreneurship in Limpopo, which was chosen as the second site for this study (Idemudia et al., 2013; Mothibi et al., 2015; Ramathetje & Mtapuri, 2014).

The study focused only on informal sector business owners who hold refugee (Section 24) permits under the Refugees Act. Holders of asylum-seeker (Section 22) permits were not included as many of these migrants are unlikely to be refugees, as conventionally defined. The South African Government claims that 90% of asylum-seeker permit holders are "economic migrants" and not genuine refugees as defined by the Refugee Conventions. While this figure has been disputed by researchers, it is not possible to predict whether any particular asylum-seeker permit holder will make the transition to full refugee status. Indeed, there is every likelihood that the majority will not (Amit, 2011; Amit & Kriger, 2014).

The number and geographical location of refugee enterprises in South Africa is unknown, which means that there is no comprehensive database from which to draw a sample. Therefore, this paper relied on "maximum variation sampling" (MVS) using the methodology suggested by Williams and Gurtoo (2010) in their study of the informal economy in Bangalore, India. In Cape Town, the areas of the city in which the informal economy is known to operate were first identified from the existing literature, personal knowledge and a scoping of the city. This allowed for the exclusion of significant areas of the city from the study, particularly high-income residential areas. Second, five different types of area were identified - commercial, formal residential, informal residential, mixed formal and informal residential and industrial -and within each of these types contrasting and geographically separated areas were chosen. There were two commercial areas (the CBD and Bellville), two industrial areas (Maitland and Parow), three formal residential areas (Observatory, Delft and Nyanga), three informal settlements (Khayelitsha, Imizamo Yethu and Masiphumelele) and two mixed formal and informal residential areas (Philippi and Dunoon). In Limpopo, the majority of migrant entrepreneurs live in urban centres. Since many of these centres are relatively small, the primary criterion for the application of MVS in Limpopo was variable urban size. The selected towns are scattered around the province and include Polokwane (population of 130,000), Thohoyandou (70,000), Musina (43,000), Louis Trichardt (25,000), Tzaneen (14,500) and Burgersfort (6,000).

Sampling was conducted in each site using the mapped grid-pattern exhibited by streets. Streets were sampled one after another in successive fashion moving from west to east. After identifying the first five enterprises on a street, and randomly selecting the first of the five for the sample, every third refugee-owned enterprise was selected for interview. Where business owners were not available, field workers made three call backs to the enterprise, after which a substitution was made. In each of the two study areas, a total of 504 refugee entrepreneurs were interviewed. The survey instrument was administered using tablet technology and collected information on a wide variety of issues pertaining to business set-up, activities, operation, profitability, challenges and economic impacts. The enterprise survey was complemented with fifty in-depth interviews with business-owners in each research location and three focus groups with refugees from the same country in each location. This paper presents some of the results of the survey supplemented with a selection of observations from the entrepreneurs about their experiences running businesses in South Africa.

Refugee Profile

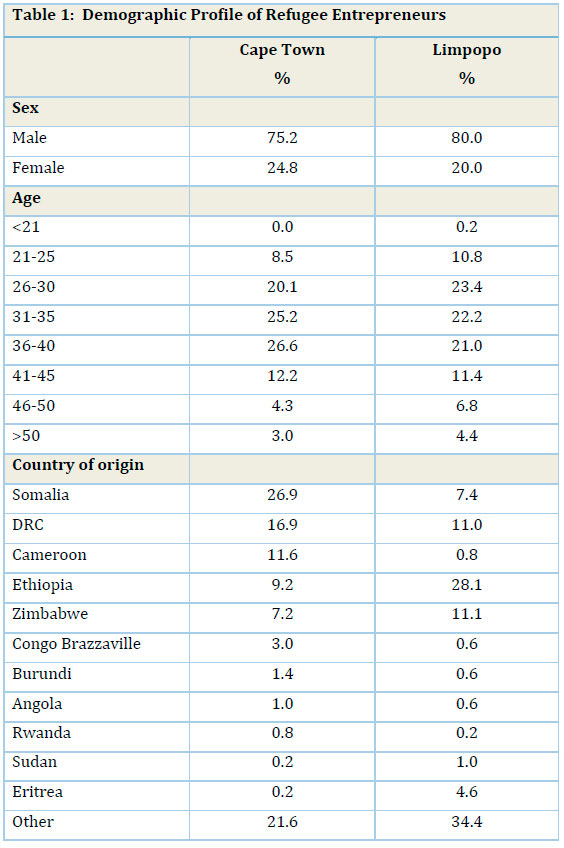

This section of the paper compares refugee business owners in Cape Town with those in small town Limpopo to ascertain if there are any significant differences in their respective socio-demographic and migration profiles. First, male refugee entrepreneurs clearly dominate in both areas, with only 20-25% of business owners being women (Table 1). This is generally consistent with the predominantly male character of refugee migration to South Africa. The entrepreneurs in both locations tend to be relatively young, with 80% in Cape Town and 77% in Limpopo being under the age of 40. Very few entrepreneurs in either location were over the age of 50. Accepting the International Labour Organisation definition of "young people" in Africa as anyone under the age of 35, this would mean that 54% of those in Cape Town and 57% of those in Limpopo are young entrepreneurs (Kew, 2015). There are no significant differences between the two groups of refugee entrepreneurs in terms of age profile. However, the difficulties and challenges facing youth entrepreneurs in South Africa, and how these are addressed by refugee youth, warrant further investigation (Fatoki & Chindoga, 2011; Gwija et al., 2014).

Despite the similarities in sex and age breakdown between the two samples, there are marked differences in the countries of origin of refugee entrepreneurs. In the Cape Town sample, the most numerous group was from Somalia, which is consistent with other studies showing a significant Somali presence in the informal economy of the city (Basardien et al., 2014; Gastrow & Amit, 2013, 2015; Tawodzera et al., 2015). While there are some Somali-owned businesses in Limpopo and Ethiopian-owned businesses in Cape Town, the largest group in this sample of refugee entrepreneurs in Limpopo towns was from Ethiopia (28%). Some national groups are well-represented in both places, including refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (17% in Cape Town and 11% in Limpopo) and Zimbabwe (7% in Cape Town and 11% in Limpopo).

In both the Cape Town and Limpopo samples, there are small numbers of refugees from the same countries, notably Burundi, Cameroon, Congo Brazzaville, Eritrea, Rwanda and Sudan. In sum, both areas are dominated by refugees from one or two (albeit different) countries, but beyond that there is considerable diversity in the makeup of the refugee entrepreneurial population.

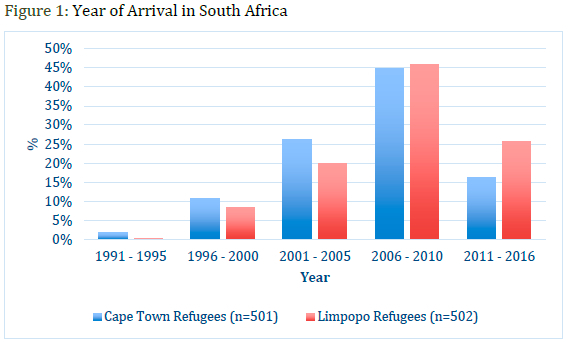

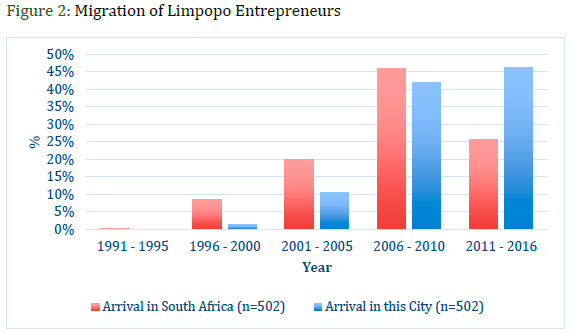

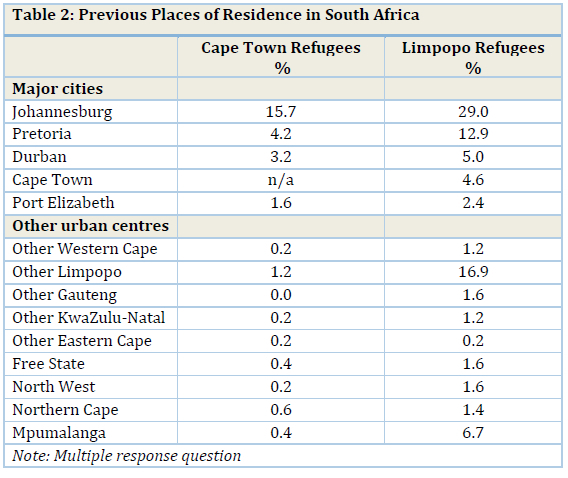

The vast majority of sampled refugee business owners (over 90% in both research locations) arrived in South Africa after 2000 (Figure 1). Limpopo has a slightly greater proportion of recent arrivals than Cape Town. For example, 71% of the refugees in Limpopo migrated to South Africa after 2005, compared to 61% of those in Cape Town. Or again, 26% of those in Limpopo arrived in South Africa after 2010, compared to only 16% in Cape Town. This raises the possibility that more recent forced migrants may be avoiding the large cities and going straight to smaller urban centres. However, in Limpopo there is a clear lag between year of migration to South Africa and year of arrival in the province (Figure 2). As many as 64% of the sampled refugee entrepreneurs in Limpopo had first lived in another South African town or city (compared to only 27% in Cape Town) (Table 2). In other words, Cape Town was the first destination for nearly three-quarters of the refugee entrepreneurs in that sample, while Limpopo was the first destination for only 13% of the entrepreneurs sampled there.

In the Limpopo sample, previous places of residence were dominated by the large cities, particularly Johannesburg (29%) and Pretoria (13%), but also Durban (5%) and even Cape Town, which is nearly 2,000km away (5%). The movement of refugees from Limpopo to Cape Town was much more limited. As many as 17% of the Limpopo refugees had lived in another town in the province, suggesting the existence of some intra-provincial mobility. This kind of movement was virtually absent in the case of Cape Town and the Western Cape Province. In the Cape Town sample, the majority of the 28% who had lived in another urban area came from Johannesburg, with much smaller numbers from cities such as Pretoria and Durban.

The major reason for relocation from large cities to small-town Limpopo concerns the pattern of violence against non-South African informal businesses (Crush et al., 2015b). Nationwide xenophobic attacks on migrants and refugees in 2008 led to considerable loss of life, damage to property and internal displacement (Hassim et al., 2008; Landau, 2012). In 2015, widespread xenophobic violence again wracked the country. Unlike the indiscriminate violence of 2008, these attacks mainly targeted small informal businesses run by migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees. Drawing on an extensive database of media coverage of xenophobic incidents, Crush and Ramachandran (2015a) chronicle an escalating pattern of xenophobic violence directed at migrants and refugees between 2008 and 2015. Refugee-owned businesses are regular targets of attacks and certain locations have witnessed collective violence in repeated cycles, including loss of store contents through looting and arson, damage to shop structure, forcible store closures, temporary or permanent displacement and loss of life (Crush & Ramachandran, 2015b). The impact of xenophobic violence is exacerbated by poor police response and follow-up. Refugees have little faith in police protection or judicial reparation, and even see the police as perpetrators or instigators of violence (Haile, 2012; Okpechi, 2011). Steinberg (2012) argues that it is the perceived failure of the authorities to control migration that has exacerbated retaliatory xenophobic mob violence.

Some studies have suggested that attacks on refugee-owned businesses are instigated or orchestrated by South African competitors, including various shadowy informal business associations (Crush & Ramachandran, 2015a). This phenomenon - dubbed "violent entrepreneurship" by Charman and Piper (2012) - involves the use of intimidatory violence as a business strategy to drive non-South African competitors out of an area. The most frequent and intense xenophobic attacks and instances of violent entrepreneurship have occurred in low-income neighbourhoods in large cities. The in-depth interviews with Limpopo refugee entrepreneurs for this study confirmed that xenophobic violence was a major factor in relocation from cities of first refuge. One Somali refugee recounted how he had arrived in Johannesburg after a long and difficult journey through several countries; experiences consistent with those of other Somali refugees (Jinnah, 2010; Sadouni, 2009). In Johannesburg, he lived with his brother and neighbours from the same village in Somalia. His brother operated a business buying goods in the CBD and selling them at his shop in Soweto. He worked for his brother for a while but found the experience unnerving: "I did not want to operate in Soweto. The people there were nice but there were others who were just rough. I had seen two people being killed in broad daylight and they were all foreigners and their shops were robbed. So I wanted to go somewhere else." With his brother's assistance he bought a small spaza (informal shop) in Orange Farm south of Johannesburg and ran it for a year:

Orange Farm was a good area for business but it was not safe. As a foreigner you are always conscious of your security and you can feel that this place is not good. It is far from the Johannesburg CBD and there are few police there. So even when there are robberies, the police come very late and sometimes they do not come at all. I was robbed seven times in the period that I stayed in Orange Farm. Most of the time the robbers would come when it is at night and you are still operating. They pounce on you with sticks, spanners or iron bars and they hityou hard. So I was almost killed twice and I thought this is enough. Let me leave this place. Then I left and came here (Interview with Somali Refugee, Polokwane, 12 March 2016).

Experience of violent crime and fears over personal safety were recurrent motives for moving to Limpopo. Interviewees moved to escape being injured or murdered rather than specifically to set up a new business. One Eritrean refugee, for example, had his spaza looted and burnt to the ground: "I came here because I was running for my life. I was not thinking of doing business, but of surviving. I was almost killed that night" (Interview with Eritrean Refugee, 21 March 2016).

Piper and Charman (2016) have argued that South African business owners are just as vulnerable to violent attacks and crime as their refugee counterparts and suggest that xenophobia is, therefore, not a factor. However, the interviewees in Limpopo clearly saw the violence in Johannesburg and other centres as motivated by xenophobia. As the former Orange Farm business owner noted: "There were many spaza shops around me, but they kept stealing from me. Is that not xenophobia? Why not steal from the locals? The customers sometimes harass you because you are a foreigner. They take your goods and are a problem in paying. So, yes, I have been affected a lot by xenophobia."

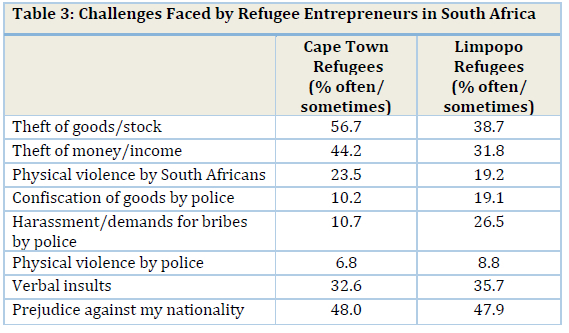

The province of Limpopo appears to be a safer haven and less inhospitable business environment than South Africa's large cities. As many as 45% of sampled Cape Town refugees said that xenophobia had affected their business operations to some extent (20%) or a great deal (25%). The equivalent figures in Limpopo were 31% in total (19% to some extent and 12% not at all). Refugees in Cape Town, for example, appear to be more vulnerable to theft and physical attack from South African citizens. For example, in the sample, 57% of refugees in Cape Town reported often or sometimes having their goods and stock stolen, compared to 39% of those in Limpopo. Similarly, 54% of refugees in Cape Town often or sometimes had money stolen, compared to 32% in Limpopo. The incidents of prejudice and verbal and physical assault by citizens were similar in both places. But while relocation to Limpopo may lessen the chance of victimisation, it certainly does not eliminate it. Many of the refugees interviewed in Limpopo told stories of being robbed and having their business premises destroyed. However, police misconduct also emerged as a greater problem for refugees in Limpopo. Alfaro-Velcamp and Shaw (2016) show that police disregard for the rights of refugees and migrants is a significant problem in Cape Town and other large cities. This survey found that police harassment, demands for bribes, confiscation of goods and physical violence were all more common in Limpopo than in Cape Town (Table 3).

Business Characteristics and Strategies

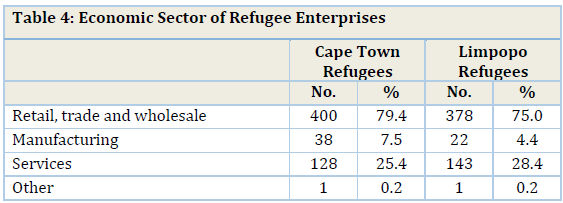

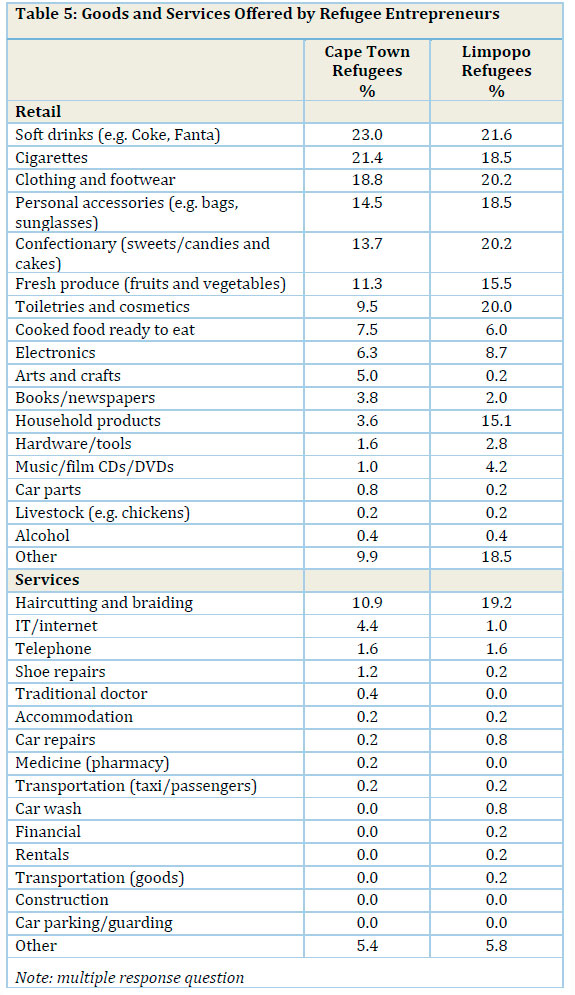

Despite being located in very different parts of South Africa, and nearly 2,000 km apart, the sampled Cape Town and Limpopo refugee entrepreneurs engaged in a similarly wide range of economic activities. The vast majority in both locations is in the retail sector (75-79%), followed by services (25-28%) and manufacturing (4.4%-7.5%) (Table 4). The kinds of goods being sold and services offered are very similar as well. Among the sampled Limpopo refugee entrepreneurs, the most common items sold are clothing/footwear, confectionary, soft drinks and toiletries/cosmetics. In Cape Town, the most common items sold are cigarettes, clothing/footwear, personal accessories and confectionary and beverages (Table 5). Comparing the two, the main difference lies in the greater numbers of refugees selling confectionary, household products, and toiletries and cosmetics in Limpopo.

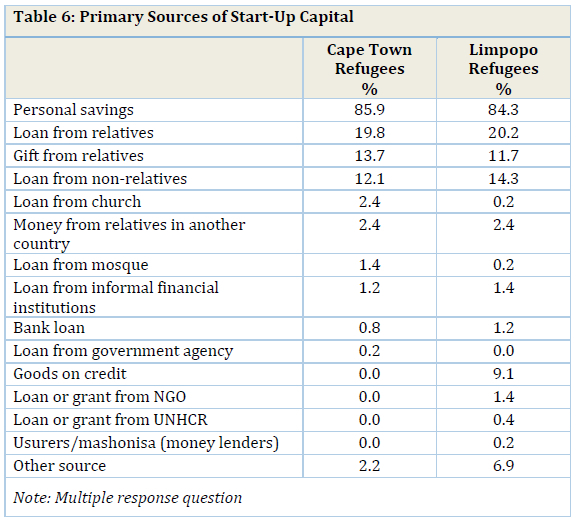

The primary sources of business start-up capital in both areas were very similar, suggesting that being in a large city does not provide additional financing opportunities (Table 6). Approximately 85% of the sampled refugees in both Cape Town and Limpopo used their personal savings to start their businesses. Around 20% of both groups used loans from relatives, 1214% used loans from non-relatives and 12% used gifts from relatives. A small number in both areas used remittances from outside the country to establish their businesses. Only a handful of refugees in both areas were able to access funding from banks, NGOs or the UNHCR. The only difference worth noting was that more entrepreneurs in Limpopo were able to access goods on credit with which to start their businesses.

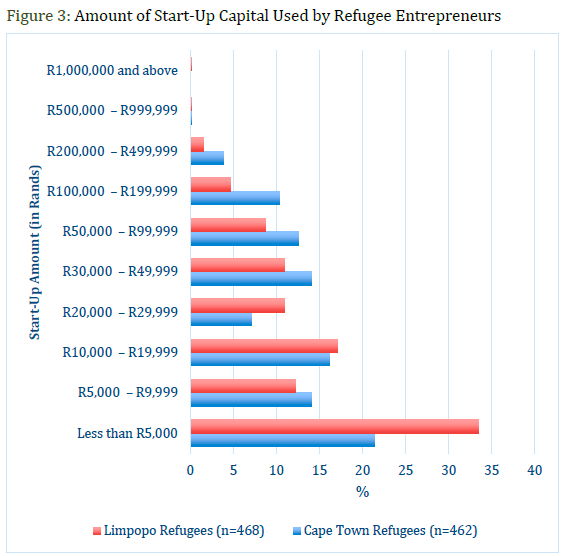

Despite the similarities in sources of start-up capital, the amounts needed to establish a business did differ. In Limpopo, the sampled refugee entrepreneurs seemed to be able to start businesses with less capital (Figure 3). 34% percent had less than ZAR 5,000 compared to 21% of the Cape Town refugee entrepreneurs, and 63% had less than ZAR 10,000 compared to 52% of the Cape Town entrepreneurs. At the other end of the scale, 27% of the sampled Cape Town refugees had more than ZAR 50,000 in start-up capital compared to only 15% of those in Limpopo.

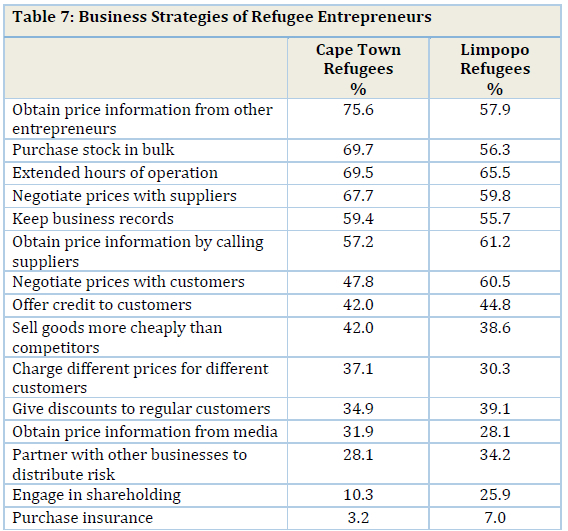

Despite their lack of prior business experience, refugees in South Africa have developed a range of strategies to maximise their returns. Table 7 lists a variety of business strategies and shows how many sampled refugees employ them in the conduct of their business. The most common strategies include bulk purchasing, extended hours of operation, keeping business records, negotiating prices with suppliers, allowing customers to buy goods on credit and competitive prices. Refugees consult other entrepreneurs, suppliers and the media for information about the price of goods. These are all commonsense business strategies and certainly do not fall into the category of underhand or secret tactics that the South African Minister of Small Business Development accused them of employing. There was very little difference in the frequency of use of business strategies by the two groups of refugees. However, living in a large city seems to provide more opportunity for buying in bulk, negotiating with suppliers and getting information on prices from other entrepreneurs. Almost one-third of the Limpopo refugees travel to Johannesburg to purchase supplies, while most Cape Town refugees obtain their goods in the city. This probably affords the latter greater opportunity for bulk buying, negotiation with suppliers and information-sharing.

Entrepreneurial Economies

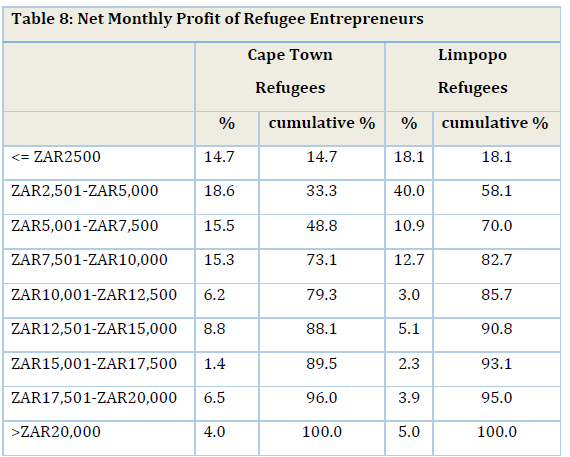

In this study, we used two measures of business success: (a) net monthly profit and (b) the difference between the current value of the enterprise and the initial capital outlay. With regards to the first indicator, net profit, it is clear that although refugees in Limpopo are able to start a business with a smaller capital outlay than those in Cape Town, their enterprises are not as profitable. The sampled Limpopo refugees earned less on average than their Cape Town counterparts: ZAR 7,246 per month compared to ZAR 11,315 in Cape Town (Table 8). Only one-third of the sampled Cape Town entrepreneurs made less than ZAR 5,000 per month compared to 58% of those in Limpopo. Or again, 70% of the Limpopo entrepreneurs make less than ZAR 7,500 per month compared to only 49% of those in Cape Town.

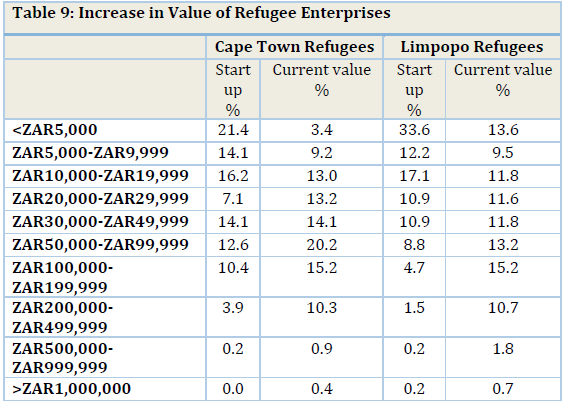

With regards to the second indicator of business success the difference between the amount of start-up capital and the current value of the enterprise in both Cape Town and Limpopo there are clear indications of increased value. For example, 21% of the sampled entrepreneurs in Cape Town started with less than ZAR 5,000 but only 3% of the businesses were currently valued at less than ZAR 5,000 (Table 9). In Limpopo, the equivalent figures were 34% (start-up) and 14% (current value). In both locations, therefore, there was significant upward movement out of the lowest value category. A similar pattern can be observed with businesses that started with less than ZAR 20,000. In Cape Town, 51% fell into this start-up category but only 26% of businesses fell into this value category. The proportion of sampled businesses in the ZAR 50,000-plus category increased from 27% to 47% and in Limpopo from 15% to 42%. This suggests that higher value businesses may actually be performing better in Limpopo than they are in Cape Town.

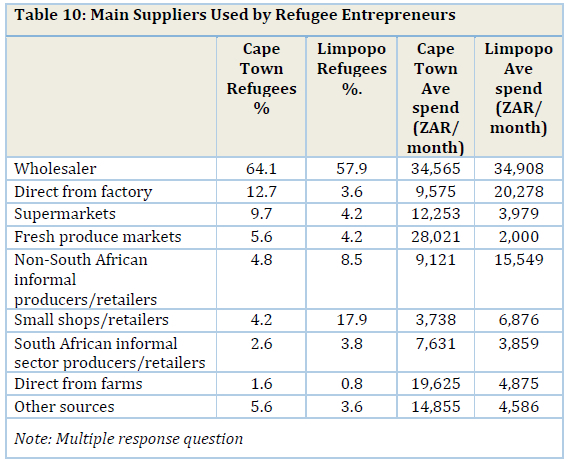

The establishment and growth of sampled refugee businesses has economic spin-offs for a variety of South African stakeholders. The first beneficiaries are formal sector suppliers including wholesalers, supermarkets, fresh produce markets, retailers and manufacturers. Around two-thirds of the sampled refugees in both Cape Town and Limpopo purchase supplies from wholesalers, who are easily the largest beneficiaries of their patronage (Table 10). Other beneficiaries vary in relative importance, reflecting the difference between operating in a large city and a small town. For example, refugees in Cape Town are more likely to patronise supermarkets and factories while those in Limpopo are more likely to patronise small shops. The fact that more Cape Town refugees purchase directly from farms is primarily a reflection of the existence of a market gardening area (the Philippi Horticultural Area) within the city limits (Battersby-Lennard & Haysom, 2012). The average monthly spend at wholesalers was very similar in both Cape Town and Limpopo.

Otherwise, the amounts spent varied considerably but, in general, the more important the source, the greater the amount is spent.

The second major beneficiary of the activities of refugee entrepreneurs is the South African treasury. While most businesses operate in the informal sector and are too small to pay income tax, they do pay value-added tax (VAT) on most goods purchased from formal sector suppliers. One Ethiopian refugee in a Limpopo focus group observed that they not only paid VAT on goods but also were unable to claim rebates:

There are many things we do to help the economy. We operate our businesses and we buy our stock from the wholesalers. We pay VAT there so our money is going into the economy. We pay a lot of money that way. Some of our people go to buy goods that are worth ZAR 200,000 or even more. Some buy every week and some buy every day. So imagine if you are paying ZAR 200,000 for goods and VAT is 14% so that is more than ZAR 25,0001 am paying to the government. Even after paying this large amount of VAT we suffer because we cannot claim some of it because we do not have the documents. We are not registered. If we were registered at the end of the year we would claim some of the VAT like South Africans do. We are actually paying more and contributing more through VAT than most South African small businesses (Focus Group Participant, Burgersfort, 1 April 2016).

Another participant claimed that business registration was impossible because "government does not want to register us."1

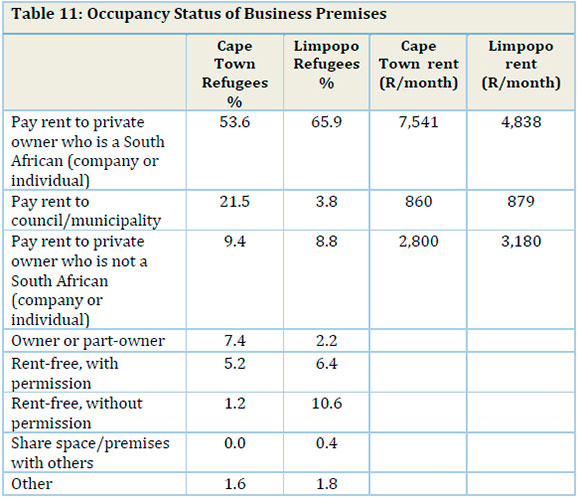

Third, as these refugees noted, they pay heavy rents to South African property owners:

South Africans are surviving on us because we pay them money to rent their shops. I pay ZAR 4,000 per month to my landlord to use the shop. That is a lot of money. How many local people can afford to pay that money? Locals do not pay that kind of money when they rent. They will pay ZAR 1,000 or ZAR 1,500 only, not ZAR 4,000. We pay because we have no choice, we want to do business and survive.2

While over half of both groups of refugees paid rent to a private South African owner, this was more common in Limpopo (almost 66%) (Table 11). However, the average monthly rentals paid to landlords were very similar: ZAR 4,838 in Cape Town and ZAR 4,555 in Limpopo. Renting also provides refugees with a modicum of protection. As one noted, "If your landlord is respected or feared, then you are okay because the thugs will not come and break in."3 The Cape Town refugee entrepreneurs were more likely to own their business premises although the numbers were small (7% compared to 2% in Limpopo). Fourth, the municipal government has a direct financial interest in its dealings with refugees. Particularly in Cape Town, refugees pay into municipal coffers through rent for business sites. This amounted to 22% of the refugee entrepreneurs in Cape Town compared to only 4% in Limpopo. These rents were higher in Cape Town, an average of ZAR 879 per month compared to only ZAR 311 per month in Limpopo. Additionally, as many as 28% of Limpopo-based refugees (and 21% of those in Cape Town) pay an annual license fee to the municipality. The cost of a business license is much higher in Cape Town at ZAR 1,959 per year compared to only ZAR 752 per year in Limpopo.

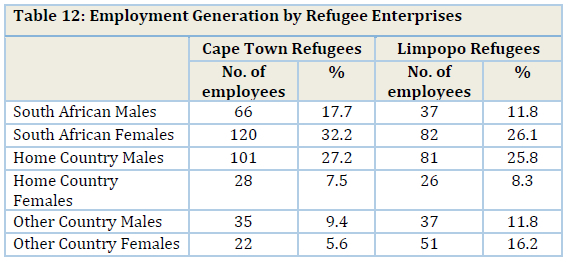

Fifth, there is a growing consensus in the research literature that migrant businesses in the informal economy create jobs for South Africans, and that this needs to be acknowledged by government. As one refugee observed: "The government does not want to accept that we are contributing. When they talk about us they make it look like we are only taking, taking and taking from the South Africans."4 Another pointed out the mutual benefits of employing South Africans:

We employ a lot of South Africans. If your business starts to grow, you employ, not only our people from Ethiopia, but also locals. They help with customers and other things. They speak the language and understand quickly what the customer wants. Even though I understand the language, there are words that I do not know and so it is better when you employ a South African, they will talk and agree and I will communicate with my employee. The locals need work and we also need workers, so it is a mutual benefit.5

Some refugees also find that employing South Africans is a form of security against theft, although it can be a double-edged sword:

It is good security because they will know the local thugs and thieves and so they may tell them to leaveyou alone. If you have a bad employee, they may connive with the thieves and steal from you, so it is both ways. Sometimes we employ locals that we know, when we know their parents and we talk to them so that they do not steal and run away. It is better to employ someone from around the area, someone in the community.6

Around half (52%) of the Cape Town refugee entrepreneurs and just under half (45%) of the Limpopo entrepreneurs employ people in their businesses (Table 12). In terms of the pro file of employees, the Cape Town and Limpopo entrepreneurs were equally likely to employ South Africans (around 50% of the total number of jobs created). While the Limpopo entrepreneurs favoured female employees (51% versus 45% of total employees), both groups preferred to hire South African women over men (with 65-70% of South African employees in both sites being female). What this suggests is that, in both large cities and small urban areas, refugee entrepreneurs may be providing jobs for more South African women than men and thereby contributing to lowering the female unemployment rate.

Finally, it is clear from the accounts of refugees in both Cape Town and Limpopo that one of the primary beneficiaries of their activities in the informal economy is the South African consumer who can access goods and services much more cheaply than from formal sector suppliers. These include necessities such as cheaper food for the food insecure, luxuries such as household and personal products and services such as panel-beating. For example, one group of five Zimbabwean refugees in Cape Town (including a former teacher), operate a panel-beating and spray-painting business in an industrial area of the city. In a focus group, they discussed at length how and why they established the business, their business challenges and the nature of the service they offer to South Africans:

We are very good at this business. There are many people who come here because they cannot afford to repair their cars in these expensive garages, so we are offering them services otherwise they would not be driving their cars. That is a good service we are offering. Some of the customers actually go to the garages first and the charges there will make them come to us (Focus Group Discussion, Cape Town, 22 February 2016).

These refugees also argued, in a prescient manner, that their activities saved the South African Government and the UNHCR from having to support them. As one commented: "In Europe the governments look after the refugees and every month they get paid like they are working. But here we are working for ourselves and are saving the government a lot of money."7

Conclusion

This paper aims to contribute to the literature on urban refugee livelihoods in the Global South and, in particular, to a small but growing body of work on urban refugee entrepreneurship in cities of refuge (Campbell, 2005, 2006; Gastrow & Amit, 2013; Omata, 2012; Pavanello et al., 2015; Thompson, 2016). The concept of 'refugee economies' is a valuable starting point for restoring agency, self-reliance and innovation to populations all too often represented as passive victims. One of the defining characteristics of many large cities in the rapidly urbanising South is the high degree of informality of shelter, services and economic livelihoods. As Simone (2004) argues, this involves "highly mobile and provisional possibilities for how people live and make things, how they use the urban environment and collaborate with one another." Furthermore, these urban spaces provide for "upscaling a variety of entrepreneurial activities through the dense intersections of actors from different countries and situations." It is these dynamic, shifting and dangerous informal urban spaces in which refugees often arrive, with few resources other than a will to survive, a few social contacts and a drive to support themselves in the absence of financial support from the host government and international agencies.

South Africa is sometimes hailed as having an extremely progressive refugee protection regime by the standards of the rest of Africa. Refugees enjoy freedoms denied in other countries, including the right to move and live anywhere and the right to work and be self-employed. Many opt for employment and self-employment in the informal economy because they find it extremely difficult to access the formal labour market or to establish and operate a business in the formal economy. Newly-arrived refugees, including those with advanced skills and professional qualifications, initially find themselves accepting menial work on construction sites or as dish-washers in restaurants. Those with relatives or friends already in the country often work in their informal businesses until they have saved enough money to launch their own. They start small and, with extremely hard work, self-sacrifice and hardship, their businesses take off. Thus, South Africa provides an important example of refugee self-reliance, motivation and agency through informal entrepreneurship.

At the same time, South Africa is one of the most xenophobic countries in the world and migrants of any kind are extremely unwelcome. Large-scale violence directed at migrants and refugees wracked the country in 2008 and again in 2015. In this span of time, extreme xenophobia, in the form of violent attacks on migrant and refugee-owned shops and small businesses, has escalated. The state refuses to acknowledge that xenophobia exists, much less that something should be done about it. Attacks on foreign businesses are dismissed as general criminality, which might be an acceptable rhetorical position if there was evidence that the police provide adequate protection and justice for the victims. The evidence of human rights observers and previous studies, and confirmed here, is that policing is lackadaisical at best and certainly does very little to protect refugees from re-victimisation in their chosen country of refuge. The fact that informal businesses started and run by refugees have become a particular target means that the South African city has become a hazardous place for refugee entrepreneurs.

Refugee economic opportunity and entrepreneurial activity is likely to vary significantly between camp and urban environments. This paper has addressed the question of variability between urban environments within the same destination country by comparing refugee entrepreneurship in the large city of Cape Town with a population of over 3 million and several small towns in the predominantly rural province of Limpopo, none with a population larger than 150,000. The research shows that refugee entrepreneurial activity in Limpopo is a more recent phenomenon and is largely a function of refugees moving away from large cities such as Johannesburg where their businesses and lives are in greater danger. While Somali refugees predominate in Cape Town and Ethiopian refugees in Limpopo, the refugee populations in both areas are equally diverse and tend to be engaged in the same wide range of activities.

Less start-up capital is needed in Limpopo but the refugees in both areas pursue similar business strategies and make similar contributions to the local economies. They face many of the same business challenges, including problems with documentation and the refusal of banks to offer credit, although small town policing appears to be harsher and more corrupt. While South African consumers clearly benefit from and appreciate their presence, migrant entrepreneurs are more vulnerable to xenophobic violence in Cape Town than Limpopo. In short, different urban geographies do shape the local nature of refugee entrepreneurial economies, but there are also remarkable similarities in the manner in which unconnected refugee entrepreneurs establish and grow their businesses in large cities and small provincial towns.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the UNHCR Geneva for funding the Refugee Economic Impacts SAMP research project on which this paper is based.

References

Achiume, T. 2014. Beyond prejudice: Structural xenophobic discrimination against refugees. Georgetown Journal of International Law, 45: 323-381. [ Links ]

Alfaro-Velcamp, T. and Shaw, M. 2016. 'Please GO HOME and BUILD Africa': Criminalising migrants in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 42: 993-998. [ Links ]

Amit, R. 2011. No refuge: Flawed status determination and the failures of South Africa's refugee system to provide protection. International Journal of Refugee Law, 23: 458-488. [ Links ]

Amit, R. and Kriger, N. 2014. Making migrants 'il-legible': The policies and practices of documentation in post-apartheid South Africa. Kronos, 40: 269290. [ Links ]

Basardien, F., Parker, H., Bayat, M., Friedrich, C. and Appoles, S. 2014. Entrepreneurial orientation of spaza shop entrepreneurs: Evidence from a study of South African and Somali owned spaza shop entrepreneurs in Khayelitsha. Singaporean Journal of Business Economics and Management Studies, 2: 45-61. [ Links ]

Battersby-Lennard, J. and Haysom, G. 2012. 'Philippi Horticultural Area' AFSUN and Rooftops Canada Abri International, Cape Town and Toronto.

Betts, A., Bloom, L., Kaplan, J. and Omata, N. 2014. Refugee economies: Rethinking popular assumptions. Humanitarian Innovation Project Report, Refugee Studies Centre, Oxford: University of Oxford. [ Links ]

Buscher, D. 2011. New approaches to urban refugee livelihoods. Refuge, 28: 17-29. [ Links ]

Campbell, E. 2005. Formalising the Informal Economy: Somali Refugee and Migrant Trade Networks in Nairobi. Global Migration Perspectives No. 47, Geneva: Global Commission on International Migration. [ Links ]

Campbell, E. 2006. Urban refugees in Nairobi: Problems of protection, mechanisms of survival, and possibilities for integration. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19: 396-413. [ Links ]

Charman, A. and Piper, L. 2012. Xenophobia, criminality and violent entrepreneurship: Violence against Somali shopkeepers in Delft South, Cape Town, South Africa. South African Review of Sociology, 43: 81-105. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Chikanda, A. 2014. Forced migration in Southern Africa. In: Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E., Loescher, G., Long, K. and Sigona, N. (Eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Ramachandran, S. 2015a. Doing business with xenophobia. In: Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Ottawa and Cape Town: IDRC and SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Ramachandran, S. 2015b. Migration myths and extreme xenophobia in South Africa. In: Arcarazo, D. and Wiesbrock, A. (Eds.). Global Migration: Old Assumptions, New Dynamics, Volume 3. Santa Barbara: Praeger. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). 2015a. Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Ottawa and Cape Town: IDRC and SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Skinner, C. and Chikanda, A. 2015b. Informal Migrant Entrepreneurship and Inclusive Growth in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 68, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Desai, A. 2008. Xenophobia and the place of the refugee in the rainbow nation of human rights. African Sociological Review, 12: 49-68. [ Links ]

De Vriese, M. 2006. Refugee Livelihoods: A Review of the Evidence. Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit, EPAU/2006/04. Geneva: UNHCR. [ Links ]

Fatoki, O. and Chindoga, L. 2011. An investigation into the obstacles to youth entrepreneurship in South Africa. International Business Research, 4: 161-169. [ Links ]

Gastrow, V. and Amit, R. 2013. Somalinomics: A Case Study on the Economics of Somali Informal Trade in the Western Cape. ACMS Research Report, Johannesburg: Wits University. [ Links ]

Gastrow, V. and Amit, R. 2015. The role of migrant traders in local economies: A case study of Somali spaza shops in Cape Town. In: Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Ottawa and Cape Town: IDRC and SAMP. [ Links ]

Gordon, S. 2016. Welcoming refugees in the rainbow nation: Contemporary attitudes towards refugees in South Africa. African Geographical Review, 35: 117. [ Links ]

Greyling, T. 2015. The Expected Well-Being of Urban Refugees and Asylum-Seekers in Johannesburg. ERSA Working Paper, 507. Cape Town: ERSA. [ Links ]

Gwija, S., Eresia-Eke, C. and Iwu, C. 2014. Challenges and prospects of youth entrepreneurship development in a designated community in the Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 6: 10-20. [ Links ]

Haile, T. 2012. Immigrants and Xenophobia: Perception of Judicial System Personnel and Experiences of Ethiopian Immigrants in Accessing the Justice System in Newcastle, South Africa. MA Thesis (Unpublished), KwaZulu-Natal: University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Handmaker, J., de la Hunt, L. and Klaaren, J. (Eds.). 2011. Advancing Refugee Protection in South Africa 2nd Edition. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

Hassim, S., Kupe, T. and Worby, E. (Eds.). 2008. Go Home or Die Here: Violence, Xenophobia and the Reinvention of Difference in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Idemudia, E., Williams, J. and Wyatt, G. 2013. Migration challenges among Zimbabwean refugees before, during and post arrival in South Africa. Journal of Injury and Violence Research, 5: 17-27. [ Links ]

Jacobsen, K. 2005. The Economic Lives of Refugees. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press. [ Links ]

Jacobsen, K. 2006. Refugees and asylum seekers in urban areas: A livelihoods perspective. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19: 273-286. [ Links ]

Jinnah, Z. 2010. Making home in a hostile land: Understanding Somali identity, integration, livelihood and risks in Johannesburg. Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 1: 91-99. [ Links ]

Kavuro, C. 2015. Refugees and asylum seekers: Barriers to accessing South Africa's labour market. Law, Democracy and Development, 19: 232-260. [ Links ]

Kew, J. 2015. Africa's Young Entrepreneurs: Unlocking the Potential for a Brighter Future. Ottawa: IDRC. [ Links ]

Koizumi, K. and Hoffsteadter, G. (eds.) 2015). Urban Refugees: Challenges in Protection, Services and Policy. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Landau, L. 2008. Protection as capability expansion: Practical ethics for assisting urban refugees. In: Hollenbach, D. (Ed.). Refugee Rights: Ethics, Advocacy, and Africa. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. [ Links ]

Landau, L. (Ed.). 2012. Exorcising the Demons Within:Xenophobia, Violence and Statecraft in Contemporary South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Lyytinen, E. and Kullenberg, J. 2013. Urban Refugee Research: An Analytical Report. New York: International Rescue Committee and Women's Refugee Commission. [ Links ]

Mothibi, K., Roelofse, C. and Tshivhase, T. 2015. Xenophobic attacks on foreign shop owners and street vendors in Louis Trichardt Central Business District, Limpopo Province. Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 11: 151-162. [ Links ]

Okpechi, A. 2011. Access to Justice by Refugees and Asylum Seekers in South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Cape Town: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Omata, N. 2012. Refugee Livelihoods and the Private Sector: Ugandan Case Study. Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper Series No. 86, Oxford: University of Oxford. [ Links ]

Omata, N. and Kaplan, J. 2013. Refugee Livelihoods in Kampala, Nakivale and Kyangwali Refugee Settlements: Patterns of Engagement with the Private Sector. Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper Series No. 95, Oxford: University of Oxford. [ Links ]

Omata, N. and Weaver, N. 2015. Assessing Economic Impacts of Hosting Refugees: Conceptual, Methodological and Ethical Gaps. Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper Series No. 11, Oxford: University of Oxford. [ Links ]

Owen, J. 2015. Congolese Social Networks: Living on the Margins in Muizenberg, Cape Town. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. [ Links ]

Pavanello, S. Elhawary, S. and Pantuliano, S. 2015. Hidden and exposed: Urban refugees. In: Koizumi, K. and Hoffstaedter, G. (Eds.). Urban Refugees: Challenges in Protection, Services and Policy. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Piper, L. and Charman, A. 2016. Xenophobia, price competition and violence in the spaza sector in South Africa. African Human Mobility Review, 2: 332-361. [ Links ]

Polzer Ngwato, T. 2013. Policy Shifts in the South African Asylum System: Evidence and Implications. Pretoria: LHR and ACMS. [ Links ]

Ramatheje, G. and Mtapuri, O. 2014. A dialogue on migration: Residents and foreign nationals in Limpopo, South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5: 573-585. [ Links ]

Roever, S. and Skinner, C. 2016. Street vendors and cities. Environment and Urbanization, 28: 359-374. [ Links ]

Sadouni, S. (2009). God is Not Unemployed: Journeys of Somali Refugees in Johannesburg. African Studies, 68: 235-249. [ Links ]

Simone, A. 2004. People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture, 16: 407-442. [ Links ]

Smit, R. and Rugunanan, P. 2014. From precarious lives to precarious work: The dilemma facing refugees in Gauteng, South Africa. South African Journal of Sociology, 45: 4-26. [ Links ]

Steinberg, J. 2012. Security and disappointment: Policing, freedom and xenophobia in South Africa. British Journal of Criminology, 52: 345-360. [ Links ]

Tawodzera, G., Chikanda, A., Crush, J. and Tengeh, R. 2015. International Migrants and Refugees in Cape Town's Informal Economy. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 70, Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Thompson, D. 2016. Risky business and geographies of refugee capitalism in the Somali migrant economy of Gauteng, South Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42: 120-135. [ Links ]

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2014. Global Strategy for Livelihoods, A UNHCR Strategy, 2014-2018. Geneva: United Nations. [ Links ]

Williams, C. 2013. Out of the shadows: Classifying economies by the extent and nature of employment in the informal economy. International Labour Review, 154: 331-351. [ Links ]

Williams, C. and Gurtoo, A. 2010. Evaluating competing theories of street entrepreneurship: Some lessons form a study of street vendors in Bangalore, India. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8: 391-409. [ Links ]

Zack, T. 2015. 'Jeppe': Where low-end globalisation, ethnic entrepreneurialism and the arrival city meet. Urban Forum, 26: 131-150. [ Links ]

1 Focus Group Participant, Burgersfort, 1 April 2016.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Focus Group Discussion, Cape Town, 22 February 2016.