Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.1 Cape Town Jan./Abr. 2017

Harnessing Economic Impacts of Migrant Remittances for Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Critical Review of the Literature

Themba Nyasulu

Fellow in International Development, Institute for Development Research and Development Policy (IEE), Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany. Email: Themba.Nyasulu@ruhr-uni-bochum.de

ABSTRACT

The recent rise in migrant remittances across Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the important issues currently dominating economic policy discourse in the region. Given the large volume of remittance flows, it is obvious that they have important positive and negative economic effects on the individual families and economies that receive them. Therefore, this paper critically examines channels through which remittance transfers affect microeconomic and macroeconomic activity, and suggests policy options available to Sub-Saharan African countries in terms of harnessing their development potential. The paper affirms that prospects for remittances to facilitate economic development remain high provided that recipient countries put in place institutional frameworks capable of mitigating the malign effects and enhancing the benign effects of remittances.

Keywords: migrant remittances, microeconomic impacts, economic development, Sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction

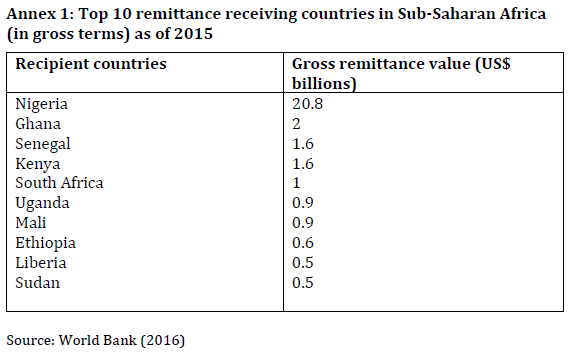

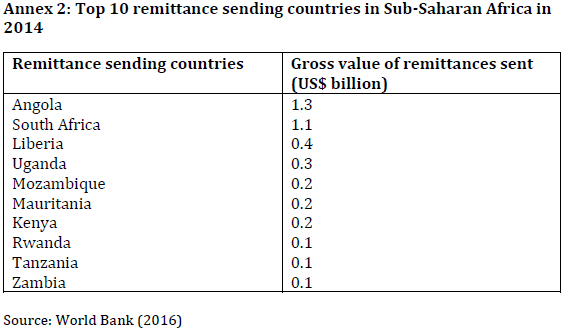

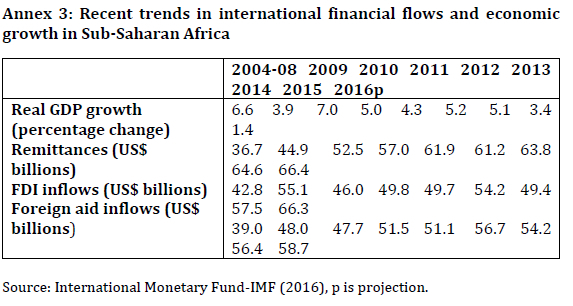

Remittances, referring to money sent by migrants to their countries of origin, are among the important topics currently dominating economic policy discussions across the globe. In line with the reality that more than 3.4 percent (i.e. more than 247 million people) of the world population lives outside their countries of birth, remittances have also been expanding rapidly in recent times. The World Bank (2016) observes that as of 2015, global remittance flows exceeded US$601 billion. A similar pattern has prevailed in Sub-Saharan Africa where remittances have meteorically risen so much so that they now, together with foreign direct investment and aid, constitute one of the three most important forms of capital inflows in the region (IMF, 2016).

From both an empirical and a theoretical point of view, migrant remittances are reputed to generate important economic impacts, which in turn profoundly influence development. In particular, these economic impacts are normally felt in terms of consumption, gross domestic product (GDP), foreign exchange reserves, exchange rates, exports and imports, and the country's creditworthiness, among others. Moreover, remittance flows also have important impacts on human development through their influences on poverty reduction, education and health outcomes (Chami et al., 2008; Chami & Fullenkamp, 2013; Dinbabo & Carciotto, 2015). For Sub-Saharan Africa, which is the least developed region in the world and also home to over two-thirds of world's poorest people, the above remittance-induced economic impacts, whether positive or negative, have a significant bearing on the development prospects of the region. This also suggests that there are multiple paths through which remittances affect both macroeconomic and microeconomic activity in recipient countries in this part of the world. As such, both the benign and malign economic impacts of migrant remittance inflows on development in Sub-Saharan African countries cannot simply be presumed but deserve critical empirical investigation.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is twofold: first, to analytically assess microeconomic and macroeconomic economic effects of remittances on development, and secondly, to suggest ways through which Sub-Saharan African countries can effectively utilise remittance receipts in order to maximise their development impact. In undertaking these tasks, the discussion critically reviews available theoretical and empirical literature on the subject from both Sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions of the world. The paper is organised as follows: the economic motivations for remitting are analysed at the beginning of the discussion. After this, the paper examines the impacts of remittances on recipient households (i.e. micro-level) and the economies of Sub-Saharan Africa (i.e. macro-level). Furthermore, the discussion suggests some policy recommendations for leveraging the economic impacts of remittances for development. Finally, concluding remarks on the subject in question are presented in the epilogue.

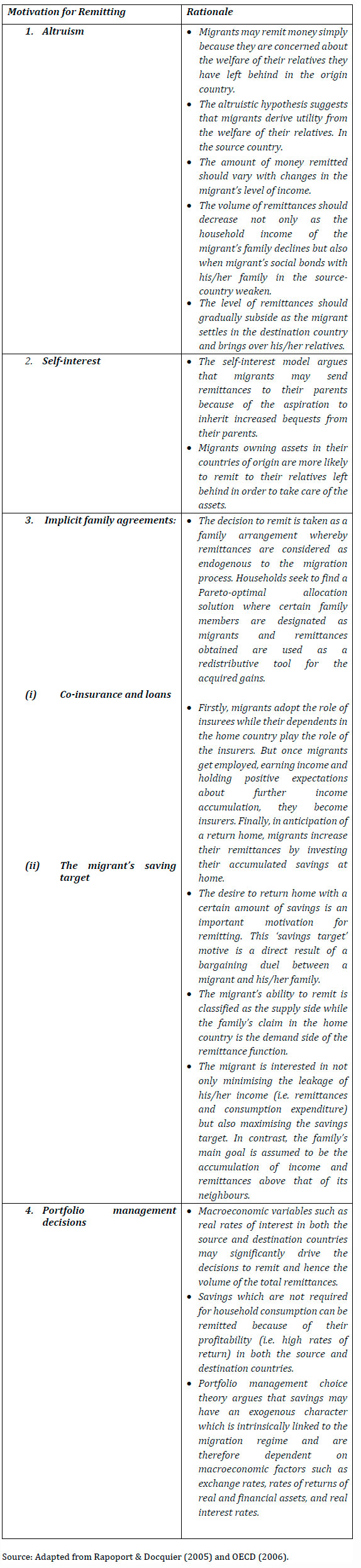

Economic Motivations for Migrant Remittances

Among the important drivers of remittance flows are both the ability of migrants to generate and save income and their determination to remit savings back to their countries of origin (i.e. source/home countries). It must also be pointed out that the willingness to send remittances may also be driven by the length of time migrants plan to stay abroad either on a permanent or temporary basis. For others, their family status (i.e. single or married) and social networks may play an important role in their decisions to remit. This indicates that there are several ways of analysing determinants of remittance flows, one of which is examining the motivations of migrants to remit. A careful survey of the literature reveals that there are four major economic motives for remitting, namely: altruism, self-interest, informal agreements with family members and portfolio management decisions. But this notwithstanding, there is no general theory that explains remittances (Rapoport & Docquier, 2005; OECD, 2006). Instead, what are available are empirical studies trying to describe the occurrence of remittances, even though their explanations are partial and often specific to certain geographical, socio-cultural and temporal contexts. The table below summarises the four major economic motives for remitting.

Economic Impacts of Remittances

The discussion classifies economic impacts of remittances on development into macroeconomic and microeconomic categories.

Macroeconomic Impacts

A careful review of the literature in developing countries clearly shows that the impact of remittances is felt on the macroeconomic level mainly through access to finance and economic growth in the recipient country. The following section outlines the remittance-effects on the macro economy through three important channels: economic growth and financial development, economic stability and international finance.

Remittances as a Macroeconomic Stabiliser

Available empirical and theoretical evidence indicates that remittances behave in a counter-cyclical manner, meaning that their changes are inversely related to macroeconomic fluctuations. The main implication of this is that remittances insulate recipient households in home countries from the vagaries brought about by macroeconomic fluctuations (Chami et al., 2009). For instance, Ratha (2007) observes that money sent by migrants to their home countries rose significantly during the financial crisis of the 1990s in Mexico as well as during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, especially in countries such as Thailand and Indonesia. During this time, other private flows such as FDI and equity flows were at an all-time low. Apart from the surges experienced during financial crises, remittances have also shown a tendency to increase counter-cyclically in times of natural disasters and socio-political upheaval in the developing world (Clarke & Wallsten, 2004; Yang & Choi, 2007; Mohapatra et al., 2009; Sithole & Dinbabo, 2016).

With this, therefore, Ratha (2003) and Frankel (2011) argue that remittances have different characteristics relative to most other private flows such as FDI, foreign aid or portfolio equity. This is so because remittances primarily consist of transactions made by households in destination countries. As such, they are less influenced by profit-maximising motives that are commonly associated with private resource flows. On the same note, Sayan (2006) observes that remittances show pro-cyclical patterns when they are sent in order to accomplish investment purposes in home countries. These patterns are more pronounced in middle-income developing countries than in low-income ones (Lueth & Ruiz-Arranz, 2008). Evidence from several Sub-Saharan African countries indicates that remittances show more stability in times of economic crises relative to other private capital flows such as private debt and equity flows and FDI (Dinbabo & Carciotto, 2015; Gupta et al., 2009).

Remittances as a Source of External Finance and Guarantor for Creditworthiness

It is now widely recognised in international finance that remittance inflows have a significant potential to boost global sovereign creditworthiness primarily by increasing the volume and stability of foreign exchange received by countries. Large remittance receipts have enabled many African countries to reduce their trade imbalances and hence lower their current account deficits (Avendano et al., 2009). According to Chami et al. (2008), remittances have also enabled these countries to stabilise their current account fluctuations by steadying the overall flow of capital. Similarly, Bugamelli and Patemo (2009) have argued that, as a rule of thumb, remittances significantly reduce current account deficits when they exceed 3 percent of the total national income. These examples give a clear indication of the importance of remittance flows to source countries as far as external financing is concerned.

It is an open secret that effective accounting of remittances can go a long way in improving the evaluation of credit worthiness and debt sustainability of many African source countries. Ratha et al. (2011) argue that the foreign debt-to-exports ratio for many African source countries would be significantly lower if remittances were included in the analysis as a denominator. The importance of remittances in debt sustainability analysis is now recognised by multilateral agencies such as IMF and the World Bank. In recent times, remittances have formed important variables necessary for sovereign assessments and debt sustainability analyses in middle-income and low-income countries, respectively (IMF, 2016). However, despite the importance of the above, very few remittance-receiving African economies have managed to have their creditworthiness appraised by major sovereign rating agencies.

Remittances as Collateral for Development Financing

Remittances provide collateral for mobilising financing for economic development in international capital markets. The success in this endeavor of countries such as Brazil, El Salvador, Turkey and Kazakhstan suggests that Sub-Saharan African countries that often face severe capital constraints can also use future remittances as an important tool for mobilising development finance (Ratha, 2005; Ketkar & Ratha, 2009). Indeed, securitising future remittance receipts can help countries in the Sub-Saharan African region to mobilise not only cheaper but also long-term financial resources for development. Ratha et al. (2011) argue that since remittances in most cases are denominated in hard currencies, international banks can use them as collateral to obtain loan injections, provided their ability to settle domestic transactions in local currencies is not impeded. So, by securitising future remittance flows, migrant source countries are able to not only obtain higher sovereign credit ratings, but also attract a large number of potential foreign investors who can spur economic development.

In a similar vein, a number of banks in the aforementioned countries have utilised remittance securitisation to obtain lower cost international financing and maturities. Undeniably, with the support of the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), many countries throughout the region have used the securitisation of future remittances to acquire significant medium-term development loans (Afreximbank, 2005; Rutten & Oramah, 2006; Ratha et al., 2011). Ghana, Nigeria and Ethiopia are some of the economies in the region that have used the remittance-backed syndicated facilities to obtain external financing for their development projects in sectors such as agriculture and infrastructure investment (Afreximbank, 2005).

Ratha et al. (2011) argue that African countries can leverage a small fraction of their future remittance receipts to issue bonds. But, of course, the quantity of bonds issued would very much depend on the level of collateral possible for banks to secure. Available estimates project that the potential for securitisation of future remittance flows in Africa stood in excess of US$35 billion as of 2009 (Ratha et al., 2009). However, it is worth noting that at present, securitisation of remittance flows faces significant challenges in many low-income African countries. Among the major bottlenecks identified in the literature include: underdeveloped domestic financial systems, limited integration of domestic banks into the global financial system, and exorbitant fixed costs incurred when acquiring legal, credit rating and investment banking services (Ketkar & Ratha, 2009).

It must also be pointed out in passing that remittance-backed bonds may, however, pose a risk to issuers, especially if there is a currency mismatch that often accompanies foreign currency debt. Ratha et al. (2011) contend that developing countries need to put in place prudent risk management mechanisms before obtaining additional debt. Additionally, the existence of political instability may expose African economies to volatility in remittance flows as well as disruption of social networks between migrants and their countries of origin. What is more, increased foreign currency inflows resulting from the issuing of remittance-backed bonds may trigger currency appreciation in African countries with fragile macroeconomic structures.

Remittances as a Driver of Economic Growth, Financial Development and Competitiveness

Remittance flows are also known to positively affect economic growth, competiveness and financial development in many migrant source countries. The positive effect of remittances on growth and development is mainly transmitted through the following channels: consumption and investment increases, productivity enhancing social spending, and both macroeconomic and microeconomic stability of consumption and production (Chami et al., 2009; Dinbabo & Nyasulu, 2015; Mohapatra et al., 2009; Sithole & Dinbabo, 2016). The above benefits in turn boost investment supply by spurring the demand for financial intermediation. This is what ultimately conveys the positive impacts of remittance flows on economic growth in developing countries. Literature on the subject is awash with empirical examples from Sub-Saharan African countries confirming the above scenario (Rajan & Zingales, 1998; Gupta et al., 2009; Akinlo & Egbetunde, 2010).

Apart from the positive effects, remittances can also negatively affect growth. Indeed, several theoretical reasons have been advanced as to why remittances may reduce the level of economic growth. To begin with, researchers argue that a large inflow of remittances may trigger an appreciation in the value of the domestic currency, which in the end can curtail growth through reduction of tradable production and other scale economies and externalities. This negative exchange rate effect on growth is what is commonly known as the 'Dutch disease' (World Bank, 2006; Acosta et al., 2010 Gupta et al., 2009). However, Rajan and Subramaniam (2005) find no empirical evidence suggesting that remittance-induced exchange rate surges have negatively affected growth in developing countries across the globe.

A second channel through which remittances may depress growth is the reduction of labour supply. In theory, since migration takes away some of the most productive individuals, it therefore deprives the home country of an important growth driver, labour supply (Lucas, 1987; Azam & Gubert, 2006; Bussolo & Medvedev, 2007; Chami et al., 2008). However, there is very little empirical evidence supporting the above argument. In fact, in many developing countries that are characterised by high unemployment and underemployment levels, the loss of one laborer can easily (and cheaply) be replaced by another. As such, the remittance-induced labour supply-reductions will likely have a very limited negative effect on economic growth.

On another note, some economic commentators suggest that additional income emanating from remittance receipts eases pressure on migrant destination countries to improve the quality of social service delivery, since with the help of remittances the recipient households can afford to access alternative private services (Abdih et al., 2008; Sithole & Dinbabo, 2016). The above researchers also find evidence suggesting that remittances greatly boost home countries' foreign exchange position and hence ease balance of payment bottlenecks and fiscal deficits that characterise many developing countries. In contrast, Catrinescu et al. (2006 observe that the impact of remittances on growth is only positive in countries that already possess high-quality political and economic institutions. For these economists, many developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are unlikely to harvest the growth dividends from remittance inflows because they lack the necessary policy and institutional frameworks.

Remittances have also been touted as an important mechanism for alleviating liquidity and credit constraints in many developing economies. Therefore, they play an active role in generating capital for microenterprises and, thus, act as an important alternative for financial development. Giuliano and Ruiz-Arranz (2009) examine the contribution of remittances to economic growth and financial development in developing countries. These economists find robust econometric evidence suggesting that remittances have the strongest positive impact on economic growth only when the level of financial development in the country is low. The above findings firmly resonate with the experience of many Sub-Saharan African economies that contain undeveloped financial systems and face severe liquidity and credit constraints.

Microeconomic Impacts of Remittances

Apart from having developmental impacts on the macro-level, remittances can also influence microeconomic development fundamentals such as poverty reduction, household consumption and investment decisions, as well as access to social services such as health and education. It is the aim of the following section to review available empirical literature on the microeconomic development impacts of migrant remittances on recipient regions of the developing world, including Sub-Saharan Africa.

Remittances as a Driver of Household Capital Investment and Entrepreneurship

To begin with, the fungibility of money and the unreliability of migration data in developing countries make it difficult to calculate the proportion of remittances allocated to physical capital investment and entrepreneurship in source countries. Nevertheless, ample empirical evidence still exists suggesting that recipient households devote a significant chunk of remittance receipts to investment in housing and the acquisition of land, especially in regions where there are no credible alternative stores of value for money. On the same note, empirical studies by Taylor and Wyatt (1996) reveal that in many developing home nations, the shadow value of remittances necessary for offsetting risk and liquidity bottlenecks is vital for low and middle-income recipient households that usually face challenges to obtain credit from formal financial institutions. Concurring with this assertion, Adams and Cuecuecha (2010) find that remittance-receiving families in Guatemala allocate very minimal amounts of the remittances to housing expenditure. However, the positive micro-effects of remittances are not limited to urban areas of developing regions. For instance, Adams (1998) finds that migrant remittances significantly boost investment in agricultural land in rural areas of Pakistan.

Despite the abundance of empirical evidence in Latin America and Asia, studies assessing the utilisation of remittances for investment and entrepreneurial purposes in Africa appear to be scarce. Among the few available studies are those done by McCormick and Wahba (2001), which find that remittances from return migrants greatly enhance the prospects of entrepreneurship and investment in Egypt. In addition, Osili (2004) found that not only do remittances from United States-based migrants boost investment expenditure on housing in Nigeria, but also that the investment is very responsive to macroeconomic fluctuations in exchange rate, inflation and political climate.

Ratha et al. (2011) observe that the majority of studies on Africa conducted under the auspices of the Africa Migration Project (AMP) reveal that a significant proportion of the remittances are spent on housing infrastructure, land acquisition, establishment of small-scale businesses and farming activities. There is strong empirical evidence on the above tendencies gathered from household surveys conducted in Burkina Faso, Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and Senegal.

Remittances as an Enabler for Recipient Households to Attain High Quality Education

Migrant remittances boost expenditure on education by contributing to funding of school activities in many migrants' home countries. The increased education financing reduces the need for child labour in these countries. There is ample empirical evidence in African countries suggesting that migrant remittances can contribute to increasing school enrolment and attendance levels. But despite these positive education spinoffs, migration may sometimes negatively affect children's performance in schools since the absence of parents/guardians at home as a result of migration increases the burden for kids to perform household chores (Ratha et al., 2011).

Even though there is scarcity of empirical household surveys analysing the remittance-education nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa, in some countries such as Egypt, remittances are known to increase university enrollment rates and reduce domestic chores for school-going children (Elbadawi & Roushy, 2009). On the same note, Adams & Page (2005) found that in Ghana, households that received remittances from abroad invested more in education than families with no remittance receipts. This suggests that remittances may be a potent tool for financing education in Africa.

Remittances as a Financier of Household Health Expenditure

Money sent by migrants can also enable home countries to achieve their health outcomes by, among others, empowering families in rural areas to acquire more food and healthcare services and improving their access to information on modern health practices. In support of the above hypothesis, Drabo and Ebeke (2010) found in a survey of 56 developing countries that remittances not only increased access to private treatment for communicable diseases such as malaria and diarrhea, but also augmented foreign aid in financing health outcomes. In a similar vein, an empirical study covering 84 countries by Chauvet et al. (2009) found that an increase in the level of remittances significantly reduced infant mortality, even though the reduction was higher for richer recipient households over those that were poorer.

Going further into the above analysis, Guzmán et al. (2007) found that female-headed households in Ghana spend more of their remittances on healthcare than those headed by men, irrespective of whether the remittances came from outside or within Africa. Earlier studies done in Mali by Birdsall and Chuhan (1986) also found that remittances triggered not only a rise in healthcare demand but also modern health facilities. In South Africa, Nagarajan (2009) found that between 1993 and 2004, increased migrant remittances enabled poor households in KwaZulu-Natal Province to spend more on healthcare and food items and improved access to better medical facilities.

Remittances as a Form Insurance against Adverse Socio-Economic and Climatic Shocks

There is now growing recognition among economists that migration can contribute positively to diversifying household income sources and thereby minimise their risk exposure to adversities such as famine, drought and other vagaries of nature. For example, Calero et al. (2009) observe that remittances were vital in keeping Ecuadorian children in school at a time when their households faced adverse shocks. Moreover, Weiss-Fagan (2006) and Ratha (2010) empirically demonstrate that remittances from relatives and well-wishers in the United States enabled recipient-households to ably cope with several cyclone and earthquake crises that affected Haiti in 2004 and 2010, respectively. Remittances are also reputed to have accelerated the recovery of Indonesian households affected by the 2004 tsunami disaster. On the same note, Wu (2006) observes that remittance-receiving families showed evidence of a quicker recovery than those with no access to money from migrants. A similar episode was also reported in Pakistan where remittances enabled the recovery and reconstruction of household livelihoods after a ravaging earthquake (Suleri & Savage, 2006).

It is a well-known fact that in many disaster-prone regions of Africa, migration and remittances play a vital role in enabling recipient households to cope with the resultant shocks and thereby smooth their consumption patterns (Block & Webb, 2001; Dinbabo & Carciotto, 2015). Lucas and Stark (1985) buttress the above point by empirically showing that families facing drought in Botswana were able to avert income shocks by utilising their increased remittance receipts to purchase livestock and food for sustenance. In a similar study, Mohapatra et al. (2009) unearth a somewhat startling result that during droughts, remittance-receiving families in Ethiopia are less likely to pawn their product assets such cattle for food as a way of consumption-smoothing. However, a study by Quartey and Blankson (2004) reveals that migrant remittances are the major source of consumption-smoothing for Ghanaian small-holder farmers in rural areas.

Furthermore, there is empirical evidence emanating from rural Mali suggesting that remittances are an effective tool for dealing with various types of household income shocks (Gubert, 2002). Apart from cushioning households from income shocks, remittances were also found to be an important risk-diversification tool for Malian and Senegalese farming households in times of adverse climatic conditions (Azam & Gubert, 2005 and 2006). Besides, money from migrants abroad can enable their relatives in home countries to construct durable and more resilient housing. In concurrence with this view, Mohapatra et al. (2009) found that in Burkina Faso and Ghana, remittances enabled recipient households to construct more concrete and iron-roofed houses than non-remittance receiving families.

Remittances as a Potent Tool for Poverty and Inequality Reduction

In the literature, it is a well-established fact that remittances have the ability to reduce the level of household poverty. This is so because, among others, remittances supplement the incomes of poor recipient families and boost aggregate demand levels and, in turn, create employment opportunities and wage earnings of the poor (Ratha et al., 2011). Seminal studies by Adams and Page (2003 and 2005) strongly support the above theoretical assertions by illustrating that increased inflows of remittances in migrant source countries greatly diminish the share of poor people in the country.

There is a plethora of econometric studies suggesting that remittances play an important role in poverty reduction in Africa. Ajayi et al. (2009) and Anyanwu and Erhijakpor (2010) find evidence that suggests that official international remittances as a percentage of the GDP have a significant positive effect on poverty reduction in 33 African countries. Likewise, Gupta et al. (2009) find that the remittance-induced poverty reduction in Africa is much higher when compared to other developing regions of the world. Similarly, numerous case study analyses in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Lesotho, Morocco and Nigeria, among others, firmly endorse the poverty-reducing effect of remittances in rural regions (Lachaud, 1999; Quartey & Blankson, 2004; Adams & Page, 2005; Sorensen, 2004; Odozia et al., 2010). These studies further suggest that remittances not only reduce the overall number of people living in poverty but also reduce the severity and depth of the deprivation.

Despite the availability of numerous studies analysing the relationship between remittances and poverty, the same cannot be said about the remittance-inequality nexus. The World Bank (2006) and Ratha and Mohapatra (2007) argue that the ambiguity of the impact of remittances on income inequality is largely a result of the unavailability of counterfactuals, i.e. how inequality levels in the source countries would be in the absence of remittance inflows. Nevertheless, the influence of income inequality on the decision to emigrate and actual flows of remittances is quite clear. As a matter of fact, households receiving remittances from outside Africa may need a certain income threshold for them to ably sponsor a family member to emigrate in the first place. Remittance-receiving families may also have higher incomes than those households with no access to remittances.

Some Policy Options for Leveraging Remittance Impacts for Economic Development in Sub-Saharan Africa

The positive role that remittances play in poverty reduction, growth enhancement and social transformation has been explored at length in this paper. Both theoretical and empirical studies broadly agree that remittances contribute to socio-economic development in source countries by meeting the basic needs of recipients such as housing, education and health. This is in addition to the facilitation role that remittances play in transferring skills and knowledge from returning migrants and the diaspora. The above merits suggest a strong case for Sub-Sahara African countries to integrate remittance inflows into their overarching migration and national development strategies.

The discussion has indicated a reasonable degree of consensus that exists among migration economists on the potential that remittances have to positively contribute to economic development in recipient countries. However, for these positive development spinoffs to be maximised there is need for proactive and targeted policies to be implemented. For instance, remittance recipient countries should improve the levels of financial literacy and financial inclusion for both their emigrants and the beneficiaries of remittances. This would ensure that the remittance funds are channelled into productive sectors. Apart from this, both migrant source and destination countries can cooperate in providing technical training on money transfers and financial services to both the remitters and the recipients. Training programs can also take the form of migrant entrepreneurship and SME (small and medium scale enterprise) development sessions. Moreover, the securitisation of remittances through initiatives such as diaspora bonds can also greatly improve the remittance-impact on socio-economic development.

Even though Sub-Saharan African countries must keep in mind that remittances are private flows, their economic effects can still be harnessed for development. One of the important ways of maximising the development impact of remittances is by formalising their flows. Furthermore, remittances can have a maximum impact on development if Sub-Saharan African governments make deliberate efforts to put in place enabling and competitive environments that allow these funds to flow into productive sectors. Another important solution is for the recipient countries to upgrade and increase coverage of their underdeveloped financial systems. Improved access to financial services facilitates the linkages between remittances and other financial products, such as savings, insurance, mortgages and credit, which in the end foster economic development (Mashayekhi, 2013).

Recipient countries in Sub-Saharan Africa should also consider reducing transaction costs for growth-enhancing remittance flows to be effective. Allowing non-bank financial institutions such as microfinance organisations to undertake distribution and proper supervision can go a long way in reducing remittance transaction costs (Ratha & Riedberg, 2005). On the same note, the removal of taxation remittances can not only lower transaction costs, but can also encourage formal transfers and increase the available fiscal revenue (Chami et al., 2008; World Bank, 2011). It would be advisable for remittance-receiving Sub-Saharan African countries to implement consumption-based taxation in order to reduce the deleterious effects on economic growth. Such a taxation system would also help these countries to greatly reduce distortions induced by macroeconomic stabilisation policies, and also reap the remittance benefits emanating from tax-driven investments.

More importantly, perhaps, it would be prudent for remittance-receiving Sub-Saharan African countries to channel their remittance inflows into activities that promote economic development in the long-term, and preserve poverty alleviation efforts in the short-term. This so because there is lack of empirical clarity on whether the two main development objectives of remittances: growth enhancement and poverty reduction are compatible (Ratha, 2013). This being the case, the above governments should strive to strike a delicate balance in allocating remittance receipts between competing growth-promoting activities and poverty alleviating measures. The increased fiscal space generated by remittance inflows certainly allows for this undertaking.

International financial institutions can also play a crucial role in assisting recipient Sub-Saharan African countries to leverage the economic impacts of remittances for development. Through engagement and dialogue, these financial organisations can encourage governments to not only implement but also to accelerate the necessary reforms pertaining to remittance inflows. Instead of imposing one-size-fits-all reform prescriptions, international financial institutions should encourage country-specific strategies that are driven by the remittance inflow characteristics of each Sub-Saharan African nation. This may assist these countries to boost the development potential of remittance receipts.

All in all, international cooperation between Sub-Saharan African countries and the international community could also be a key to enhancing the economic development impact of remittances. This international cooperation agenda should primarily focus on making remittances cheaper, safer and more productive for both migrant source countries and destination countries.

Concluding Remarks

In conclusion this paper observes that even though remittances have a significant potential to contribute to economic development, many Sub-Saharan African recipient economies have not been able to maximise the developmental benefits from their economic impacts. Therefore, this calls for a better understanding of the realities concerning the remittance-effects on economic development. Without doubt, policy makers intending to channel remittance receipts into economic development need to appreciate that these inflows can have both positive and harmful consequences on the economy. Coupled with this is the fact that remittances do not automatically gravitate towards economic development-enhancing activities, but may sometimes flow into development-inhibiting activities, mainly because of the moral hazards that are associated with them. Against this background, Sub-Saharan African countries that desire to reap the positive economic benefits of remittances need to establish enabling institutional and infrastructural frameworks capable of channeling these inflows into development-enhancing activities through the financial system and private sector. Furthermore, recipient governments need to muster political will in order to efficiently utilise the fiscal revenue generated by remittances in order to judiciously invest only in those public goods and infrastructure that yield the highest returns. To this end, this paper strongly advocates for the development of well-functioning domestic institutions as an important driver for harnessing the positive economic benefits of remittances for development. It is beyond doubt that remittances have a significant potential to facilitate economic transformation, but to translate this possibility into reality, Sub-Saharan African countries need to develop and strengthen their economic and social institutions.

References

Abdih, Y., R., Chami, J., Dagher, and Montiel, P.2008. Remittances and Institutions: Are Remittances Curse? IMF Working Paper 08/29. International Monetary Fund.

Acosta, P., E., Lartey, and Mandelman, F. 2010.Remittances, Exchange Rate Regimes, and the Dutch Disease: A Panel Data Analysis. Review of International Economics, 20(2): 377-395. [ Links ]

Adams, R.1998.Remittances, Investment and Rural Asset Accumulation in Pakistan. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 47:155-173. [ Links ]

Adams, R., and Cuecuecha, A.2010.Remittances, Household Expenditure and Investment in Guatemala. World Development 38 (11): 1626-1641. [ Links ]

Adams, R., and Page, J. 2003. International Migration, Remittances and Poverty in Developing Countries. Policy Research Working Paper 3179.World Bank, Washington, DC.

Adams, R., and Page, J. 2005. Do International Migration and Remittances Reduce Poverty in Developing Countries? World Development, 33 (10): 16451669. [ Links ]

Afreximbank (African Export-Import Bank). 2005 Annual Report. http://www.afreximbank.com (retrieved on 11 December 2016).

Ajayi, M., M., Ijaiya, G., Ijaiya, R., Bello, M., Ijaiya, and Adeyemi, S. 2009.International Remittances and Well-Being in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economics and International Finance, 1(3):78-84. [ Links ]

Akinlo, A., and Egbetunde, T. 2010. Financial Development and Economic Growth: The Case of 10 Sub-Saharan Africa Revisited. The Review of Banking and Finance, 2(1): 17-28 [ Links ]

Anyanwu, J., and Erhijakpor, A.2010. Do International Remittances Affect Poverty in Africa? African Development Review, 22 (1):51-91. [ Links ]

Avendano, R., N., Gaillard, and Nieto Parra, S. 2009. Are Workers' Remittances Relevant for Credit Rating Agencies. Development Center Working Paper 282. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris.

Azam, J-P. and Gubert, F. 2005. Those in Kayes: The Impact of Remittances on Their Recipients in Africa. Revue Économique, 56 (6): 1331-1358. [ Links ]

Azam, J-P., and Gubert, F. 2006. Migrants' Remittances and the Household in Africa: A Review of Evidence. Journal of African Economies, 15 (AERC Supplement): 426-462. [ Links ]

Birdsall, N., and Chuhan, P. 1986. Client Choice of Health Care Treatment in Rural Mali. Unpublished manuscript for the Health, Nutrition and Population Department. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Block, S., and P. Webb, P. 2001. The Dynamics of Livelihood Diversification in Post Famine Ethiopia. Food Policy, 26 (4): 333-350. [ Links ]

Bugamelli, M., and Paterno, F. 2009. Do Workers' Remittances Reduce the Probability of Current Account Reversals. World Development, 37 (12): 18211838. [ Links ]

Bussolo, M., and Medvedev, D. 2007. Do remittances have a flip side? A general equilibrium analysis of remittances, labor supply responses, and policy options for Jamaica. Working Bank Policy Working Paper 4143. Washington D.C.

Calero, Carla, Arjun S. Bedi, and Robert Sparrow. 2009. Remittances, Liquidity Constraints and Human Capital Investments in Ecuador. World Development, 37 (6):1143-1154. [ Links ]

Catrinescu, N., M., León-Ledesma, M., Piracha, and Quillin B.2006.Remittances, Institutions, and Economic Growth. IZA Discussion Paper No. 2139.

Chami, R, A., Barajas, T., Cosimano, C., Fullenkamp, M., Gapen, and Montiel, P.2008. Macroeconomic Consequences of Remittances. IMF Occasional Paper No. 259. International Monetary Fund.

Chami, R., Fullenkamp, C.2013.Workers' Remittances and Economic Development: Realities and Possibilities. In Maximizing the Remittances Impacts on Development, United Nations Commission for Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Geneva.

Chami, R., D., Hakura and Montiel, P. 2009. Remittances: An Automatic Stabilizer? IMF Working Paper 09/91. International Monetary Fund.

Chauvet, L., F. Gubert, and Mesplé-Somps, S. 2009. Are Remittances More Effective than Aid to Reduce Child Mortality? An Empirical Assessment Using Inter- and Intra-Country Data. DIAL Working Paper DT/2009-11.

Développement, Institutions et Analyses de Long terme (DIAL), Paris.

Clarke, G., and Wallsten, S.2004. Do Remittances Protect Household in Developing Countries against Shocks? Evidence from a Natural Disaster in Jamaica. World Bank, Development Research Group, Washington, DC

Dinbabo, M. and Carciotto, S. 2015. International migration in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): A call for a global research agenda. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 1(2): 154-177. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M. and Nyasulu, T. 2015. Macroeconomic determinants: Analysis of 'Pull' factors of international migration in South Africa. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 1(1): 27-52. [ Links ]

Drabo, A. and Ebeke, C.2010. Remittances, Public Health Spending and Foreign Aid in the Access to Health Care Services in Developing Countries. Working Paper E/2010/04. Centre d'Etudes et de Recherche sur le Développement International (CERDI), Clermont-Ferrand, France.

Elbadawi, A., and Roushdy, R.2009.Impact of International Migration and Remittances on Child Schooling and Child Work: The Case of Egypt. Paper prepared for the World Bank's MENA International Migration Program. Washington, DC.

Frankel, J.2011. Are Bilateral Remittances Countercyclical? Open Economies Review, 22 (1): 1-16. [ Links ]

Giuliano, P. and Ruiz-Arranz, M. 2009. Remittances, Financial Development and Growth. Journal of Development Economics, 90 (1): 144-152. [ Links ]

Gubert, F.2002.Do Migrants Insure Those Who Stay Behind? Evidence from the Kayes Area (Western Mali). Oxford Development Studies, 30 (3): 267-287. [ Links ]

Gupta, S., C., Pattillo, and Wagh, S.2009. Impact of Remittances on Poverty and Financial Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 37 (1):104-115. [ Links ]

Guzmán, J-C., A., Morrison, and Sjöblom, M. 2007. The Impact of Remittances and Gender on Household Expenditure Patterns. In The International Migration of Women, ed. Maurice Schiff, Andrew R. Morrison, and Mirja Sjöblom, 125-152. Washington, DC: World Bank.

IMF-International Monetary Fund. 2016. Sub-Saharan Africa Multispeed Growth. World Economic and Financial Surveys: Regional Economic Outlook. Washington, D.C.

Ketkar, S. and Ratha, D. (ed.). 2009. Innovative Financing for Development. Washington DC. World Bank. [ Links ]

Lachaud, J-P. 1999. Envoi de fonds, inégalité et pauvreté au Burkina Faso. Document de travail 40, Groupe d'Economie du Développement de l'Université Montesquieu Bordeaux IV.

Lucas, R. and Stark, O.1985. Motivations to Remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy, 93 (5): 901-918. [ Links ]

Lucas, R.1987. Emigration to South Africa's Mines. The American Economic Review, 77(3): 313-330. [ Links ]

Lueth, E., and Ruiz-Arranz, M. 2008.Determinants of Bilateral Remittance Flows. B.E Journal of Macroeconomics, 8 (1), Article 26. [ Links ]

Mashayekhi, M.2013.Leveraging Remittances for Development. In Maximizing the Remittances Impacts on Development. United Nations Commission for Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Geneva.

McCormick, B. and Wahba, J. 2001.Overseas Work Experience, Savings and Entrepreneurship amongst Return Migrants to LDCs. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 48 (2):164-178. [ Links ]

McKenzie, D., and Rapoport, H.2010. Can Migration Reduce Educational Attainment? Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Population Economics. http://www.springerlink.com/content/95ht846m8m3065l7 (retrieved on 29 November 2016).

Mohapatra, S., G., Joseph, and Ratha, D.2009.Remittances and Natural Disasters: Ex-Post Response and Contribution to Ex-Ante Preparedness. Policy Research Working Paper 4972.World Bank. Washington, DC.

Nagarajan, S. 2009. Migration, Remittances, and Household Health: Evidence from South Africa. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Economics. George Washington University. Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Odozia, J., T., Awoyemia, and Omonona, B. 2010. Household Poverty and Inequality: The Implication of Migrants' Remittances in Nigeria. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 13 (2):191-199. [ Links ]

OECD-Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. 2006. International Migrant Remittances and their Role in Development. International Migration Outlook 2006. Paris

Osili, U.2004. Migrants and Housing Investments: Theory and Evidence from Nigeria. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 52 (4): 821-849. [ Links ]

Quartey, P. and Blankson, T.2004.Do Migrant Remittances Minimize the Impact of Macro-Volatility on the Poor in Ghana? Report for the Global Development Network, University of Ghana, Legon.

Rajan, R. and Subramanian, A. 2005. What Undermines Aid's Impact on Growth? IMF Working.

Paper 05/126.International Monetary Fund and NBER Working Paper 11657 (October).

Rajan, R. and Zingales, L. 1998.Financial Dependence and Growth. American Economic Review, 88 (3):559-586. [ Links ]

Rapoport, H., and Docquier, F.2005.The Economics of Migrants' Remittances. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1531. Bonn.

Ratha, D. 2003.Workers' Remittances: An Important and Stable Source of External Development Finance in Global Development Finance: 157-175. World Bank.

Ratha, D. 2005. Leveraging Remittances for Capital Market Access. Mimeo. World Bank. Washington, DC.

Ratha, D. 2007. Leveraging Remittances for Development. Policy Brief (June). Migration Policy Institute. Washington, DC.

Ratha, D.2010. Mobilize the Diaspora for the Reconstruction of Haiti. SSRC Feature: Haiti, Now and Next, Social Science Research Council, New York. http://www.ssrc.org/features/pages/haiti-now-and-next/1338/1438. (retrieved on 2 January 2017).

Ratha, D. 2013. The Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction. Migration Policy Institute Policy Brief No. 3, September.

Ratha, D., and Mohapatra, S. 2007. Increasing the Macroeconomic Impact of Remittances. Paper prepared for the G8 Outreach Event on Remittances. Berlin. November 28-30. http://dilipratha.com/index_files/G8Berlin.pdf. (retrieved on 24 December 2016).

Ratha, D., P., De, and Mohapatra, S. 2011. Shadow Sovereign Ratings for Unrated Developing Countries. World Development, 39(3):295-307. [ Links ]

Ratha, D., S. Mohapatra, and Plaza S. 2009. Beyond Aid: New Sources and Innovative Mechanisms for Financing Development in Sub-Saharan Africa" In Innovative Financing for Development, ed. Suhas Ketkar and Dilip Ratha, 143-83.Washington DC: World Bank.

Ratha, D. and Riedberg, J. 2005. On Reducing Remittance Costs. Mimeo. Development Research Group, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Rutten, L., and Oramah, O. 2006. Using Commodity Revenue Flows to Leverage Access to International Finance: With Special Focus on Migrant Remittances and Payment Flows. Study prepared by UNCTAD Secretariat

Sayan, S. 2006. Business Cycles and Workers' Remittances: How Do Migrant Workers Respond to Cyclical Movements of GDP at Home? Working Paper 06/52, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Sithole, S. and Dinbabo, M. 2016. Exploring youth migration and the food security nexus: Zimbabwean youths in Cape Town, South Africa. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 2(2): 512-537. [ Links ]

Sorensen, N. 2004. Migrant Remittances as a Development Tool: The Case of Morocco", IOM Working Paper 2, International Organization for Migration, Geneva. http://bit.ly/2nTm6pE (retrieved on 2 December 2016).

Suleri, A. and Savage, K. 2006. Remittances in Crisis: A Case Study of Pakistan. Overseas Development Institute, London. http://bit.ly/2nFkBKC (retrieved on 15 December 2016).

Weiss-Fagan, P. 2006. Remittances in Crises: A Haiti Case Study. Humanitarian Policy Group background paper. Overseas Development Institute (ODI), London. http://bit.ly/2oy6JFS (retrieved on 15 December 2016).

Taylor, J. and Wyatt, T. 1996. The Shadow Value of Migrant Remittances, Income and Inequality in a Household-Farm Economy. Journal of Development Studies, 32 (6): 899-912. [ Links ]

World Bank. 2006. Global Economic Prospects: Economic Implications of Remittances and Migration. Washington, DC: World Bank. [ Links ]

World Bank. 2011. Leveraging Migration for Africa: Remittances, Skills and Investments. Washington DC.

World Bank. 2016. Migration and Remittances Fact book 2016, 3rd. Washington DC.

Wu, T. 2006.The Role of Remittances in Crisis: An Aceh Research Study. Humanitarian Policy Group background paper. Overseas Development Institute (ODI), London. http://bit.ly/2oEyfhX (retrieved on 27 December 2016).

Yang, D., and Choi, H-J. 2007. Are Remittances Insurance? Evidence from Rainfall Shocks in the Philippines. The World Bank Economic Review 21 (2): 219-248. [ Links ]

Annexes