Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.1 Cape Town Jan./Abr. 2017

ARTICLES

Attitude, Risk Perception and Readiness of Ethiopian Potential Migrants and Returnees Towards Unsafe Migration

Abebaw MinayeI; Waganesh A. ZelekeII

IAssistant Professor, School of Psychology Addis Ababa University

IIAssistant Professor, Department of Counselling, Psychology and Special Needs Education, Duquesne University

ABSTRACT

In Ethiopia, where there is high prevalence of migration to the Middle East and Europe, a multitude of studies have focused on the relationships between the role of smugglers, push and pull factors, and illegal migration. However, only a fraction of studies have examined the context from the individual and collective mind-set perspective. The process of the decision to migrate may be influenced by individuals' beliefs about illegal migration. This study examined the attitudes, levels of readiness and risk perceptions of potential and returnee migrants towards illegal migration to the Middle East. Survey data were collected from 1,726 Ethiopian returnee (n=991) and potential migrants (n=735). Results indicated that here was a significant difference between potential and returnee migrants in holding a positive attitude towards unsafe and illegal migration, t (1260) =-8.474, p=0.000. Potential migrants favour illegal migration more so than returnees. The level of risk perception of returnee migrants and the level of readiness for migration to the Middle East of both potential and returnee migrants was found to be below the expected mean score. Gender differences in the level of risk perception and readiness were also observed. Female participants tended to see the risks associated with unsafe migration less than male returnee migrants; female participants indicated a lower level of readiness than their male counterparts. Results imply a need to work on the level of behaviour change communication and to focus on attitude and practice change rather than mere awareness-raising. The results also imply the need to create actual jobs that can keep people from choosing unsafe migration.

Keywords: Ethiopia, migrants, attitude, risk-perception, readiness.

Introduction

Migration is a global occurrence, however, information on what shapes individuals' decisions towards unsafe migration in developing countries such as Ethiopia is scant. Although it is well-documented that poverty, system failure (Abebaw & Waganesh, 2015; Adams, 2011; Dinbabo & Carciotto, 2015; Fernandez, 2013), actions of organised criminal groups like traffickers, smugglers and brokers (Fernandez, 2013; Friesender, 2007; Gozdziak & MacDonnel, 2007; UNODC, 2010; US Department of State, 2016), family and peer pressure (Abebaw, 2013; Biniam, 2012; Marina, 2016), and other push forces (Animaw, 2011) act as causes for the high prevalence of legal and illegal migration, a similar level of attention is needed to understand what shapes migrants' decisions at the individual level. One evidence of the focus on organised crime groups is the billions of dollars invested by leading anti-trafficking nations or regions, such as the USA and Europe, in convicting traffickers and illegal migrants rather than supporting migrants. Internal dynamics within the individual migrant, like attitude and risk-perception, seem to have received little attention. This lack of understanding might undermine the agency of migrants in the decision-making process, which in turn has implications for our understanding of the migration decision and shifts the target of intervention to external forces rather than the migrants themselves (Gong et al., 2011; Sharma, 2005).

The literature regarding migrants' attitudes and risk-perceptions of migration to the Middle East and South Africa in particular, is dearth. The Middle East is becoming one of the biggest hubs for migrants (Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) alone host 17 million migrants) from South East Asia (mainly the Philippines, Sri Lanka, India and Bangladesh) and Eastern Africa and Horn of Africa (mainly Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania). Of the top ten countries with the highest migrant population relative to their 'native' population in the 2004 Human Development Report, the first four are Middle Eastern countries (GMDAC, 2015). For example, the UAE, Qatar, Kuwait and Bahrain have migrants that constitute more than 50% of their population (IOM, 2014). South Africa is also a top destination (2.2 million in a 2015 estimate) within Africa for migrants from different regions of Africa (West, East and South) (Horwood, 2009) and other parts of the world (mainly South East Asia, i.e.: India, China, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Thailand) (Statistics South Africa, 2014).

Factors related to the influx of migrants to the Middle East and South Africa should be investigated in more detail, especially because there are many safety concerns identified in various studies (Waganesh et al., 2015; Meskerem, 2011) and reports by international aid and human rights agencies such as Human Rights Watch, ILO and IOM. There is a dire need for empirical evidence to better understand what contributes to the decisions people make to migrate to the Middle East and South Africa despite the potentially unsafe situations in these destinations.

Ethiopian Context

Ethiopia is a source country for migration, smuggling and trafficking (Fernandez, 2013; Jureidini, 2011; UNICEF, 2005; US Department of State, 2016). According to the Ethiopian Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (MOLSA, 2013), in 2011/12 alone, 198,667 Ethiopian women legally (their migration processed by the Ethiopian Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs) migrated to Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait for domestic work. On top of this, 60-70% of migrants migrate illegally, that is through smuggling or being trafficked (US Department of State, 2016). In 2011/12, the illegal migration was estimated at 300,000-350,000, making the total sum close to 550,000. The Regional Mixed Migration Studies (2014) reported the smuggling of 334,000 Ethiopians through Yemen alone from 2006-2014. The issue was given attention as a major social, economic, political and national security problem following the 2013 deportation of over 163,000 Ethiopian irregular migrants when the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) cracked down on irregular migration (IOM, 2014).

Studies that address the Ethiopian migration context emphasise factors such as push and pull forces (Blagbrough, 2008; Kangaspunta, 2007; Yoseph et al., 2006)and the plight of migrants, such as sexual abuse, physical abuse, salary denial, labour exploitation, confinement and denial of access to health services (Human Rights Watch, 2008; US State Department, 2016;Abebaw, 2013). The movement of populations has been associated with sexual health risks and increased transmission of HIV/AIDS (Bastide, 2015; Weine & Kashuba, 2012; Camlin, et al., 2010). There are also reports of the negative mental health consequences of unsafe migration on victims (Anbesse et al., 2009; Bhugra, 2004; Mirsky, 2009; Waganesh et al., 2015).

Unsafe and stressful migration affects migrants, their families and their governments in general. Consequences of unsafe migration can have an impact on people physically, psychologically, socially and economically. For example, a qualitative study involving female Ethiopian migrants who were employed in the Middle East found themes of exploitation, enforced cultural isolation, undermining of cultural identity and thwarted expectations (Anbesse et al., 2009). Some women in this study alluded to being sexually assaulted and dehumanised. Women shared their experiences; one noted: "They don't see you as a human being." Another said: "There were times when I would take food from the wastebasket and eat" (Anbesse et al., 2009: 560). The aforementioned themes revealed major concerns for the mental and physical health of Ethiopian migrants in the Middle East.

Anbesse et al. (2009) remarked that migrants initially left Ethiopia hoping to work and improve their lives. But potential migrants may not have accurately evaluated the reality of potential risks related to migrating. In spite of this, how migrants perceive potential risks was not well studied, at least in the Ethiopian context. Another important issue related to better understanding the attitudes of migrants is the belief that some migrants espouse that their fate is in the hands of God, which may help them to overcome the fear and risks associated with migrating (Bastide, 2015). This is a critical point to understand about the attitudes of some migrants, because if they believe that they must endure their hardships as part of their predestined lives, their conceptualisation of a "risk" may be less relevant to them (Bastide, 2015). Paradoxically, some migrants may view leaving their birth country as a way of challenging their destiny; they do not necessarily see themselves as passive recipients of a predetermined life (Bastide, 2015). Though these beliefs may vary by individual, region and religion, these conceptualisations are important to consider when working to understand how potential migrants evaluate risks and how migrating may affect their lives. As tenants of social judgment theory (SJT) and cognitive behavioural theory (CBT) show, cognitive processes are related to subsequent behaviour. So, if migrants believe that their fate is already predetermined, they may not be concerned about the decisions they make and the safety implications of those decisions.

Research on Sudanese youth indicated that their attitudes towards international migration were influenced by their families, friends and current circumstances in their home country, often related to unemployment (Yaseen, 2012). This study asserted that "the majority of youth had positive attitudes towards migration" and believe it to be the "best solution to improve" their economic circumstances, specifically "unemployment and low incomes" (Yaseen, 2012: 108). It seems that unfavorable current circumstances may lead potential migrants to overlook the dangers of migrating.

In most Ethiopian cases, the initial migration decision is made by the migrants' own free will (Abebaw & Waganesh, 2015; Addis Ababa University, 2015; Sharma, 2005). They are often given misinformation regarding the positions and circumstances awaiting them in the host countries by brokers, agencies, smugglers and traffickers (Lansink, 2006; UN, 2000; Marina & Medareshaw, 2015). Misleading information by traffickers shapes the knowledge and beliefs of migrants. In spite of theoretical support regarding the role of an individual's attitude in decision-making of any sort, studies on attitudes of migrants towards unsafe migration is missing. The only study which addresses attitudes of Ethiopian migrants is the Regional Mixed Migration Study of 2014, entitled "Blinded by Hope: Attitude, Knowledge and Practice of Ethiopian Migrants." To reduce the impact of unsafe and illegal migration, we must improve attitudes and increase readiness of migrants for potential risks. This potential is substantiated by research that suggests that modifying attitudes also changes behaviours (Sheeran et al., 2016).

Given the importance of individuals' attitudes towards migration, it is necessary to examine factors that shape these attitudes. In this study, we proposed a conceptual framework for examining the factors that influence migrants' and potential migrants' attitudes. The framework includes both antecedents and consequences of migrant returnees and potential migrants' attitudes. The antecedents can be grouped into personal factors (e.g. gender, age and religion), social factors (e.g. mass media, family influence and peer groups), previous exposure to migration, and other environmental factors (e.g. one's level of education and economic independence). This model could help us understand how migrants' and potential migrants' attitudes towards migration are formed and maintained, which could assist in our efforts to shape those attitudes and prevent unsafe migration that may happen as a result of individuals' attitudes and misguided perceptions of risks.

Perceptions of risks are sometimes overshadowed by potential migrants' hopes for personal change for the better and a positive future for their families. This cognitive minimisation of risks might increase positive attitudes towards unsafe migration. In order to positively influence the attitudes of potential migrants, it is necessary to first understand the level of attitude and risk perception, as well as the variables that influence these attitudes and perceptions.

Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks

Attitude is a key component in judgment and subsequent courses of action. Attitude can be understood as the internal psychological tendency one uses when evaluating an idea or potential action (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). For instance, if a person is weighing whether to leave his or her birth country in hopes of obtaining better circumstances for his/her family, his/her attitude about that hope and the likely negative consequences associated with the migration (risk perception) are part of this individual's processing of the decision alternatives. There are cognitive, affective and behavioural components to attitudes which relate to beliefs, feelings and actions, respectively (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Garrett et al., 2003). SJT offers a paradigm to better understand how people's attitudes contribute to their mindset and how attitudes can change. In their theory of reasoned action, Aijen and Fishben (1980 cited in Southey, 2011) have indicated the link between attitude and behaviour and identified intermediaries that affect the strength of this link, like specificity and strength of the attitude. Stemming from Brunswik's functionalist psychology (Doherty & Kurz, 1996), SJT posits that an individual's attitudes are an integral part of the perception and evaluation of new ideas (Sherif & Hovland, 1980). Attitudes are part of a person's identity (Sherif et al., 1965), which could be based on a person's current state and past experiences, and they inform their decision-making process. Therefore, it is important to take into account the context within which a migrant returnee or potential migrant functions, and the systems that affect him/her, when trying to better infer his/her attitudes and decision-making processes. Another important piece of SJT is persuasiveness (Sherif & Sherif, 1968) and the study of the likelihood of someone to change his/her mind or attitude about something, which includes consideration of what contributes to that process. Specifically, ego-involvement, or how personally affected by or involved someone is in a particular issue, is highly relevant to how likely someone is to change his/her attitude (Sherif & Sherif, 1968). CBT also offers useful information when attempting to decipher how people come to their decisions to make changes. CBT refers to the interconnectedness of cognitive processes, emotions and behaviours. This theory is based upon a model of cognition that entails the aforementioned components. Beck's (2006) work in rational emotive behaviour therapy indicates that systematic bias may contribute to irrational thoughts. The application of CBT can be useful when attempting to better understand a person's mindset. One can apply CBT to the migrant's mindset and attitudes as part of cognitive processes as well as perceptions of risk. Given the interrelatedness of cognitions and behaviours, it is worthwhile to examine the attitudes of migrants to understand their decision-making processes to leave their birth countries. Attitudes create a potentially systematic bias that contributes to a migrant's decision to leave their country and choice of where to go. Although attitudes might be strong enough in informing the decisions of people, individuals may not be conscious of their attitudes. Some migrants may not realise the inherent danger in some of the decisions they make. So it is worthwhile to better understand their attitudes and perceptions about migration and the risks associated with it.

Taken together, SJT and CBT offer some models to aid in understanding how people come to make judgments about their lives; however, more information is needed about the migrants' mindset specifically, so they can be informed about potentially unsafe decisions they are making. Sometimes because of having strong attitudes, migrants may not be fully aware of the conditions that await them after they migrate and the dangers associated with migrating to specific regions. This leads to an attitude not based on sound knowledge or on irrational belief.

The present study examined the attitudes and risk perceptions of Ethiopian returnees and potential migrants towards migration to the Middle East and South Africa. It examined various beliefs of the study participants that influenced their decision-making processes to commit to or consider unsafe or illegal migration. It reviewed variations in belief systems based on participants' demographic characteristics. Understanding the belief systems of Ethiopian returnees or potential migrants can promote culturally and contextually relevant outreach and treatment (Chang-Muy & Congress, 2009). Specifically, the study addressed four research questions regarding returnee and potential migrants' belief systems towards migration: 1)What is the level of readiness, risk perception, and attitude of Ethiopian potential migrants and returnees towards migration to the Middle East and South Africa?2) Is there a significant relationship between readiness, risk perception and attitude among returnee and potential migrants? 3) Is there a significant difference in risk perception and attitude between returnees and potential migrants? And 4) What is the effect of readiness and risk perception on the attitudes of returnees and potential migrants towards migration?

Method

A. Site of the Study

This study was conducted in six regions identified as hotspots for migration from Ethiopia to the Middle East and South Africa. The six regions consist of eight sites identified as hotspots for migration based on previous studies (Animaw, 2011; Abebaw, 2013), Ethiopian media reports and consultation with the Ethiopian Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. The sites included two zones in Oromia region, two zones from the Southern Nations and Nationalities region, one zone in Amhara region, one zone in Tigray, and Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa city administrations.

B. Participants

Using a purposive sampling technique (convenient and snowball), study participants were individuals who either returned from the Middle East and South Africa or those who were preparing to migrate to the Middle East or South Africa illegally. Data was collected from February-April2014. Of the 1,771 participants, 60.5% (n=1036) were returnee migrants from the Middle East or South Africa and 39.5% (n=735) were potential migrants who planned to illegally migrate to the Middle East or South Africa. Both returnees and potential migrants completed a survey questionnaire having demographic, readiness, attitude and risk perception items/scales.

C. Instrumentation

At the time of this writing, there were no standardised or empirically validated scales that measure the constructs proposed in this study (readiness, attitude and risk perception of migrants to unsafe migration). Also, there were no instruments available in Amharic, the primary language of Ethiopia. Consequently, this survey was developed by a group of psychology and social work faculty members at Addis Ababa University. Based on a comprehensive review of the risks and challenges associated with migration and a review of the literature on Ethiopian and African migration, the researchers developed the survey instrument. The instrument was organised into five sections: (a) demographic data, (b) antecedents, (c) readiness scale, (d) perception of risk scale and (e) attitude scale.

Demographic questions included sex, age, employment status, educational level, religion, region of residency and migration status of respondents. The antecedents section asked information about the role of social context like family, brokers, agencies, friends, relatives and mass media. It also asked about personal reasons and motivations that shaped decision-making.

D. Readiness Measure

This was a five items scale, which measured participants' levels of readiness to work in the cultural context and understandings of the nature of the job circumstances in the destination countries. Items included; How aware are/were you about the nature of the job in the destination? How familiar are/wereyou about the culture of the destination country?How aware are/were you about your rights and responsibilities in the destination country? How confident are/were you in your coping skills if you face challenges? How much do/did you know about the communication style in the Middle East/South Africa? Scores were computed by taking the sum of the 5 items (each measured on a 1 to 4 Likert scale), with 1 being "totally unaware" and 4 being "very aware." Scores for this variable ranged from 5 to 20.

E. Risks Perception Scale

The Perception of Risk Scale was a three point Likert scale which measured participants' perceptions of the risks involved in migrating to the Middle East and South Africa. The items included: Level of fear of being cheated by broker or agency or employer; Level of concern about facing difficult circumstances in the destination country; Level of determination to go to the Middle East or South Africa even through illegal channels if the legal process doesn't work; and Level of concern about safety while traveling through the illegal migration route. The scale score is computed by taking the sum of the 4 items measuring the knowledge of risks, each measured on a 1 to 3 scale with 1 being 'I know much,' 2 being 'I know some' and 3 being 'I don't know.' The scores for this variable range from 3 to 12, and the scores were reverse-coded so that high scores reflected more knowledge and low scores reflected little knowledge regarding risks.

F. Attitude Scale

The attitude scale was a six item scale developed to measure participants' attitudes towards unsafe or illegal migration. The scale consisted of items such as: Life is predetermined, not affected by whether you migrate or not; I prefer working low status jobs overseas than in Ethiopia; I don't believe working in Ethiopia changes my own or my family's life for the better; I believe media reports on the problems of illegal migration are exaggerated; I prefer to work overseas with no dignity than living under poverty in Ethiopia; and I believe that Ethiopian youth can change their own life and their family's lives only by working overseas. The scale score was computed by taking the sum of the 6 items, each measured on a 1 to 4 Likert scale, with 1 being 'strongly disagree' and 4 being 'strongly agree. 'The scale score ranged from 6 to 24. Since the items were negatively-worded, the scores were reverse-coded so that low scores reflected negative attitudes and high scores reflected positive attitudes towards unsafe migration to Saudi Arabia and South Africa.

The measures were developed and administered in Amharic. Internal consistency estimates (Cronbach's Alpha) for each subscale were computed to confirm the reliability of the subscales used in this study. The reliability estimates for all the subscales were as follows: attitude (a=. 79), risk perception (a=.54) and readiness (a=. 72). The reliabilities of the measures were, therefore, quite satisfactory (Panayides, 2013) and indicate consistency.

G. Data Collection Procedures

With approval from Addis Ababa University's Office of the Vice President for Research and Technology Transfer, 21 data collectors (three in each of the six zones and three more for Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa) and 7 supervisors (one for each of the six zones and one for Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa) were hired and given a day-long training in the data collection process. The data collectors included graduate students and faculty members at higher institutes in Ethiopia from the fields of Psychology, Social Work, Law, Economics and Health. The supervisors were faculty members from Addis Ababa University. They were assigned to assist and monitor the data collection process. The data collectors explained the purpose of the study to the study participants before administering the questionnaire. Participation in the study was voluntary. Returnees and potential migrants who chose to participate completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. Those who could not read were assisted by the data collectors in completing the questionnaire.

H. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to report participants' demographic characteristics and the associated factors involved in participants' decision-making about migration. A factorial MANOVA was conducted to evaluate the differences due to Migration Experience, Gender, Religion and Education on the three dependent variables of readiness to work in destination context, attitude towards migration and perception of risk. Pre-screening of data was conducted to identify outliers and missing data, and to collapse the response categories of the independent variables with small sample sizes in cases where it made conceptual sense. For example, for the variable Education, the categories of 'Certificate/diploma' and 'First degree and above' in the original data were combined into one category, 'Certificate/diploma and above.'

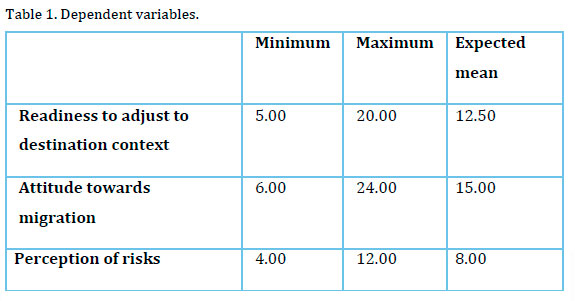

I. Variables

The main independent variables in this study were demographic variables (see Table 2); migration experiences (returnee vs. potential), gender, religion and educational level. The dependent variables were readiness to adjust to the destination context, attitude towards migration and perception of risks (see Table 1).

Research Findings and Analysis

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

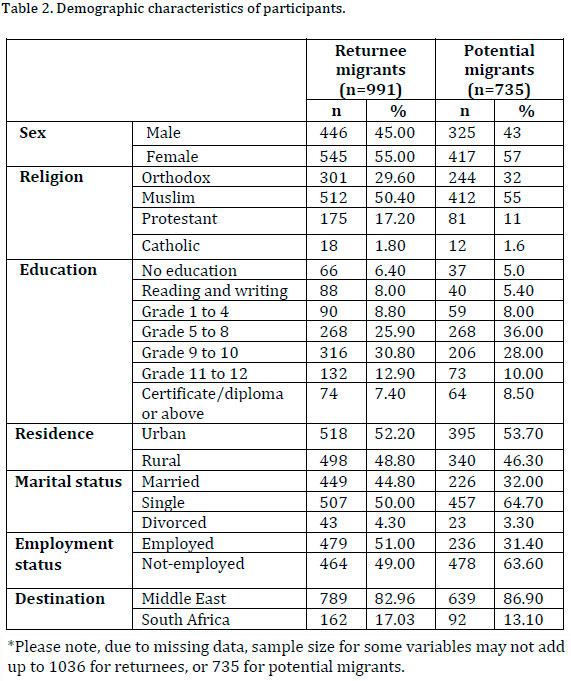

The sample consisted of 1,726individuals of which 991 were returnee migrants from the Middle East and South Africa and 735 were potential migrants who were considering migrating to the Middle East or South Africa. A demographic profile of the sample is presented in Table 2.

Returnee Migrants

The returnees were between the ages of 16 and 60 years (M=27.55; SD 6.34). Approximately 55% (n=545) were female and 44.9 % (n=446) were male. Over 82.96% (n=789) returned from the Middle East, while 17.04% (n=162) returned from South Africa. Over half (51.2%) of the returnees resided in an urban setting (n=518) and 48.8% were from rural parts of Ethiopia (n=498).In terms of participants' education, 6.4% (n=66) did not have any formal education, 8% (n=88) could write and read, 8.8%(n=90) attained grade 1-4 levels of education, 25.9% (n=268) had grade 5-8 levels of education, 30.8%(n=316) completed grade 9-10, 12.9% (n=132) completed grade 11-12 and7.3% (n=74) had a certificate, diploma or above. The prior migration job profile of returnees indicated that 49% (n=464) did not have a specific job other than supporting their families. Over half 51% (n=479) reported that they were employed as domestic workers, daily labourers, government employees or other types of low-class jobs.

Potential Migrants

The average age of potential migrant participants was 25.3 years. Approximately, 57% were female (n=417) and 43.3% were male (n=325). Over half (53.9%) of the participants resided in urban settings (n=398) and 46.1% were from rural parts of Ethiopia (n=340). In terms of education, 5% (n=37) did not have any formal education, 5.4% (n=40) said they could read and write, 7.9%(n=59) attained a grade 1-4 level of education, 35.9% (n=268) had a grade 9-10 level of education, 27.7%(n=206) completed a grade 5-8 level of education, 9.8% (n=73) completed a grade 11-12 level of education and the 8.5% (n=63) had a certificate/diploma or above. In terms of employment, 63.6% (n=478) did not have a job at the time they planned to migrate, whereas 31.4% (n=236) had a job.

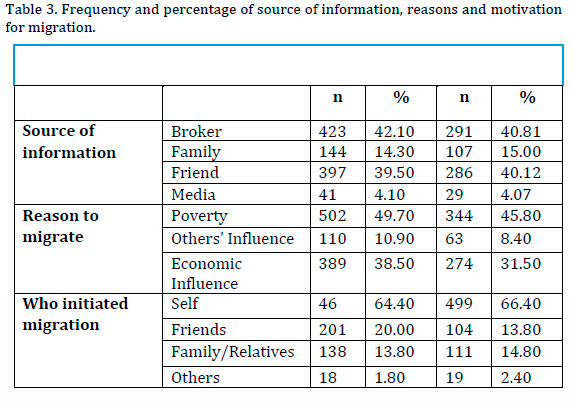

Associated Factors that Lead to Migration or the Decision to Migrate

The motivation for migration for 64.4% of returnees (n=646) and 66.4% of potential migrants (n=499) came from themselves, while 20% of returnees (n=201) and 13.4% of potential migrants (n=104) reported that their friends encouraged them to migrate. About 13.8% (n=138) of returnees and 14.8% (n=111) of potential migrants reported that families/relatives initiated the decision to migrate. Less than 1.8% (n=20) of returnees and 5.4% (n=39) of potential migrants reported the initiative came from brokers and agencies. Concerning source of information, 42.1% of returnees reported that they got the information on how to go to the Middle East from brokers, 39.1% got it from friends, 14.3%indicated family as their source of information and 4.1% of returnees reported they received the information from the media.

Related to the major reasons for migrating, almost half, 49.7%, of returnees and 45.8% of potential migrants indicated poverty, while 38.5% of returnees and 31.5% of potential migrants indicated a lack of opportunity for employment in Ethiopia and a desire to be economically independent. The data on source of information, reasons for migration and motivation for migration is presented in Table 3.

Risk Perception of Unsafe Migration

The results show that the returnee migrants' score (M=10.307, SD=1.81) was lower than the expected average (M=12.5). These results suggest that returnee migrants assumed lesser risk related to unsafe migration. The independent t-test indicated that there was a significant difference between male (M=10.57, SD=1.75) and female returnees (M=10.0984, SD=1.842) on their levels of risk perception, t (649) =3.43, p=0.001. This suggests that female returnee migrants tend to acknowledge the risks associated with unsafe migration less than male returnees.

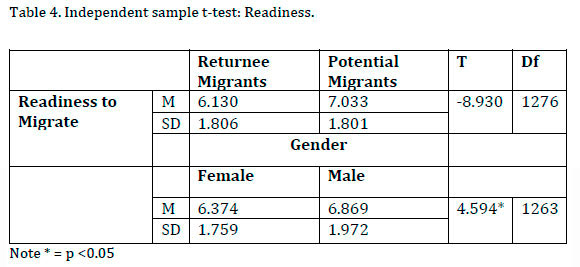

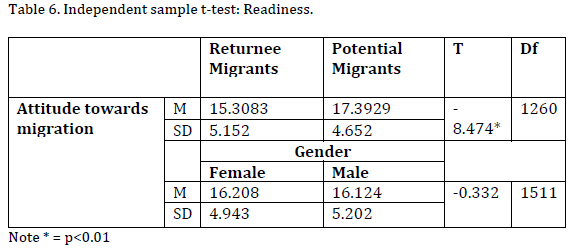

Participants' Readiness

Both returnee (M=6.13) and potential migrants' (M=7.04) scores were below the average (8.00) on the readiness scale. An independent sample t-test was conducted to compare the difference between returnee (M=6.1304, SD=1.80) and potential migrants (M=7.04, SD=1.80) in terms of their levels of readiness, t (1276) =-8.93, p=0.23. These results suggest that both returnee and potential migrants' levels of readiness to migrate to the Middle East and South Africa are less than the expected mean. The independent t-test result revealed that there was a significant difference between male (M=6.87, DS=1.97) and female participants (M=6.37, SD=1.75) with regards to level of readiness, t (1263) =4.59, p=0.04. These results suggest that females were, or are, less prepared for illegal migration than their male counterparts.

Attitude towards Migration

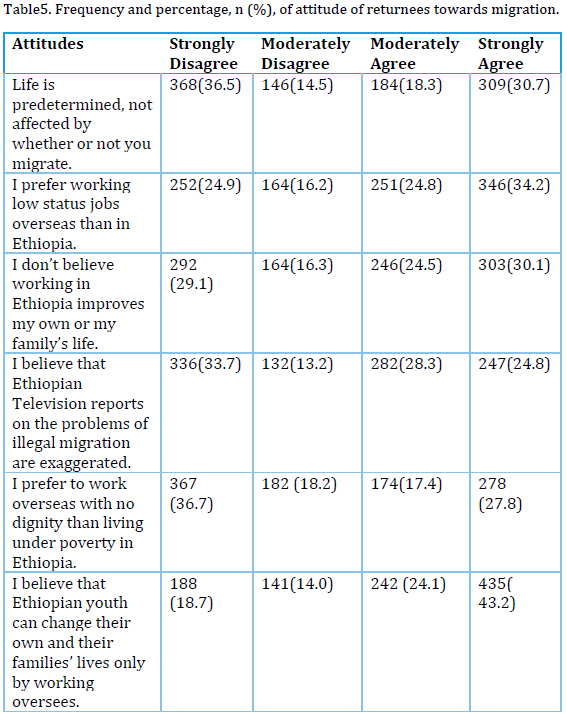

As Table 5 shows, 49% of the returnees believe that life is pre-determined, showing an undermining tendency of vulnerability. Over 60% prefer working a low-paying job abroad than doing the same job in Ethiopia, indicating a favorable attitude towards migration. Close to 55% of the returnees do not believe that working in Ethiopia will help to change their own and their family's life for the better, rather 65% of the returnees believe that Ethiopian youth can change their life for the better by working abroad. Over 53% of the returnees believe that reports by the media, specifically the Ethiopian Television, about the problems of illegal migration are exaggerated. All of this shows that almost half of the migrants had a positive attitude towards migration of any sort (legal or illegal).

The general attitude scale result shows that 540 (57.1%) of the returnees have a positive attitude toward migration in any form. This reveals that despite their plight and expulsion by force and after facing several problems in the destination country, more than half of these returnees are in favor of migration. They added that if they got the chance they would be willing to re-migrate even if it was risky (with the likelihood of being trafficked). The one sample statistic for returnees shows that there is no significant difference between the expected and obtained means, indicating that returnees are not significantly in favour of or against the expected unsafe migration despite what they have experienced.

The independent t-test results indicated a significant difference between returnee migrants (M=15.318, SD=5.15) and potential migrants (M=17.39, SD=4.65) on the level of attitude towards illegal or unsafe migration, t (1260) =-8.47, p=0.000. These results suggest that potential migrants have a more favourable attitude towards unsafe migration than returnee migrants. The difference between female (M=16.21, SD=4.94) and male (M=16.124, SD=5.202) attitudes towards migration, t (1511) =-0.332, p=0.74, was found to be insignificant.

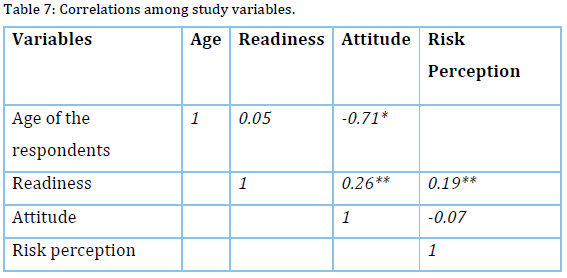

Relationship Between Participants' Ages and the Dependent Variables

Age has a high negative correlation with attitude, showing that younger participants have more positive attitudes towards migration. Readiness has a strong positive correlation to both risk perception and attitude (p < 0.01), showing that better readiness is associated with higher risk perception but positive attitude to migration.

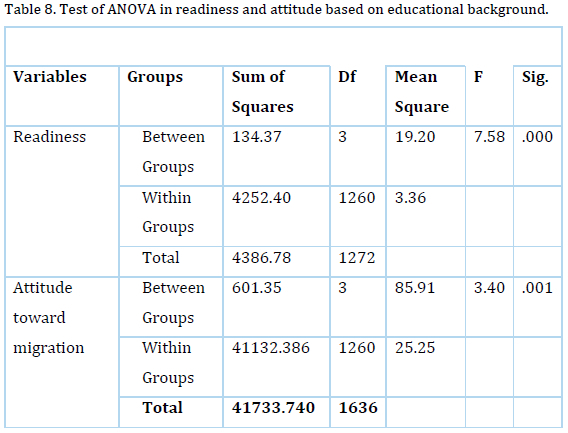

Analysis of Variance: Education, Attitude and Readiness

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) yielded significant differences between levels of education among participants and readiness, F(7,591)=4.62,p<0.001; level of education and attitude towards migration (F(7,692)=2.10, p<0.05); gender and awareness (F(3,1260)=7.58, p<0.000); and gender and attitude (F(3,1260)=3.40, p<0.001. These results suggest that participants' with a higher level of education seem to have better readiness (M=8.57, SD=2.38) and less favorable attitudes (M=15.79, SD=0.492) towards migration to the Middle East and South Africa than participants with less education (M=6.03, SD=1.47) and lower levels of readiness (M=17.71, SD=5.055).

Discussion

Overall, the current study indicated that both potential and returnee migrants have a positive attitude towards migration to the Middle East and South Africa. On the other hand, their levels of readiness and risk perception towards unsafe migration were found to be below the expected average. These findings are of particularly great concern because they indicate the lack of informed decisionmaking by participants about illegal or unsafe migration. More than the action of organised groups or the push forces, returnees' and potential migrants' decisions to migrate are a product of their attitudes and risk perception about migration. The results further indicated that, in general, the experience of migrating may influence risk perceptions and attitudes about migration, as returnees saw themselves as less prepared to re-migrate than potential migrants. The potential migrants had more favourable attitudes about migration than the returnees. This could be because the returnees had witnessed the challenges of unsafe migration and were more likely to have an objective evaluation of the risks, whereas potential migrants could have been more optimistic as they had not directly experienced the challenges. In terms of readiness, the potential migrants and returnees significantly differed from each other. The potential migrants reported having greater readiness. This could also be associated with returnees' emic experience of what is required during harsh travel and working in the destination. They knew their gaps better. They may have struggled to adjust to the work and social environment in the destination and in transit. Whereas potential migrants might have been guided by their optimistic bias about what was actually demanded.

Many Ethiopian domestic workers suffer in the Middle East, partly because of their poor preparation for the work and lifestyle (Waganesh, 2015). They assume that domestic work is similar in Ethiopia and in the Middle East. Returnees perceiving themselves as less prepared for migration than potential migrants may speak with the clarity of hindsight about the reality of migration. Returnees understand that they did not have much readiness for what the destination cultural, language and work-nature required. Supporting this inference, it was found that the participants' experiences related to migration had an effect on the level of his or her perception of risk and attitudes toward migration. The returnees indicated a higher level of risk perception and a less positive attitude towards migrating compared to potential migrants. This further indicates that the experiences of migrating have some influence on subsequent views on migration and possibly on willingness to migrate again as well as where to migrate. This, in particular, is in line with previous findings related to the potentially dehumanising and unfavorable situations Ethiopian migrants found themselves in when they migrated to the Middle East (Anbesse et al., 2009).

The results also suggest an association between socio-demographic characteristics such as age, sex and educational level, the perception that illegal migration is low risk, and an individual's favorable attitude towards migration. This provides some support for the argument that public education and knowledge-building may be effective strategies in addressing illegal migration issues. It is not surprising that there was a direct positive association between education level and a relatively better readiness to migrate. Education level is inversely associated with a favorable attitude to migration which makes sense in that the better the understanding level (education), the lesser an individual may favour unsafe migration. In terms of sex, female participants were less ready to migrate. Additionally, readiness and risk perception were significantly related such that increased readiness of an individual to migrate is associated with increased perceived risk related to unsafe migration. Notably, attitude about migration was negatively correlated with readiness, age and risk perception, seeming to further indicate that as one gains experience, by aging or otherwise, his or her attitudes about migration seem to become less favorable. Consistent with and building upon previous research on youth having positive attitudes toward international migration (Yaseen, 2012), the current study found that younger individuals had more positive attitudes about migration than older individuals, possibly indicating that they would rather work low-paying jobs outside of Ethiopia, even if their dignity was compromised, in pursuit of a better life. Additionally, perhaps the older migrants have gained more experience with the hardships associated with migrating, which may account for the more negative attitudes of the older participants in this study. On top of this, there are more opportunities for work for young people as the demand is higher for young labour. Previous studies have shown that trafficking and smuggling victims are largely children and women because of the growth of the service and sex industry (Lutz, 2011) and because of their hard work, compliance and submissiveness, as well as the assumption that they can be easily misguided about opportunities (IOM, 2006).

The more favourable the attitude towards migration, the less perceived risk is associated with migrating. What is arguably one of the most important points of these results is the finding that many returnees still have a favourable view of migration, even if their experiences were negative. Some indicated that they would re-migrate, even knowing that they could be trafficked. They were still in favour of migrating. What is notable about these findings is that even knowing the hardships associated with migration, many Ethiopians are willing to consciously put themselves in potentially dangerous situations in order to leave Ethiopia. Such preferences may speak to broader concerns related to conditions in Ethiopia. Looking at the individual's context and work culture in Ethiopia may be of value when attempting to understand these results. One example is the tradition of ascribing a 'brave son or daughter' to youngsters who risk their lives for the well-being of their family. A second example is the long tradition of viewing offspring as property in which children are expected to work beginning from around age six to contribute to the family's economic betterment, working within the household or in other households for a salary that goes to the family. Referencing back to SJT and CBT, perhaps the returnees are of the mindset that they would rather work abroad, even under similar poverty-stricken circumstances, than remain in Ethiopia. Thus, their behaviour could be in line with their surmised attitude that migration will not change their destiny, and it is better to leave Ethiopia than to stay. Another possible explanation is the one given by Marina and Medareshaw (2015), who propose that returnees may regret being deported before tasting the good side of migration and hence desire to try again. Another seemingly contradictory finding is the higher the readiness, the less individuals favour migrating. This may be partly related to the relationship between readiness and education. Migrants who have readiness and an understanding of the work and lifestyle of an illegal migrant may be more concerned about the possibility of abuse and, hence, they may be cautious in their attitudes.

Although there is no specific study on attitude, risk perception and readiness of migrants, the current study is consistent with one previous study by the Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (2014) that documented Ethiopian migrants being blinded by hope. In line with previous research, potential migrants often consider leaving their birth countries due to economic reasons, and they hope to have increased opportunities elsewhere (Anbesse et al., 2009). The present study has some new information about the perspectives of migrants and potential migrants. A particularly salient point from the current study is that almost half of the participants believe that life is predetermined and that migrating will not ultimately affect their lives or destinies; this particular finding is consistent with some previous literature regarding some migrants' beliefs of God as being in control (Bastide, 2015). This mindset may lead some potential migrants to overlook risks and vulnerabilities associated with migrating, relating to the aforementioned systematic bias that can be associated with cognitive theory or CBT. When we reference systematic bias, we are not indicating that this "bias" is inherently a "bad" thing, rather, we are pointing out that a systematic bias, or basis from which they operate, namely believing their lives to be predetermined, likely permeates all areas of their lives and should be taken into account.

Conclusions

The current study examined attitudes, risk perception and readiness to migrate to the Middle East or South Africa from Ethiopia. The data was gathered from Ethiopians who were either returnee migrants (n=1036) or considering migration to the Middle East and South Africa (n=735). To our knowledge, this is the first time that attitudes toward illegal migration to the Middle East have been studied in the Ethiopian context.

The main finding here is that the majority of respondents believe that migrating to the Middle East by any means, including illegal migration, is better than living in Ethiopia as there is little chance for a better life in Ethiopia. The majority perceive the risks associated with illegally migrating to the Middle East and South Africa to be very low. The level of readiness, such as being aware of what kinds of job they could do or having some knowledge and experience of the language and lifestyle of the destination country, was found to be low. The study also explored other influences that potentially shape attitudes toward migration. This included characteristics such as age, gender and educational level. The results suggest that a mix of different influences shape the perception of migration among Ethiopian returnees and potential migrants.

Migrants hold the key in the beginning of the migration decision in the form of initiating the migration, being driven by lowered risk perception and not being ready as a result of lower risk perception/optimistic bias. Of course, their risk perception and more positive attitude may be shaped by external forces like family, peers and brokers. Factors such as desire for economic independence, hearing of successes, desiring to support one's family and the lack of job opportunities shape their attitudes. Thus, a more practical action to reduce unsafe migration would be working on risk perception, readiness and attitudes of migrants. But there is also a need to work on what leads to the positive attitude and lowered risk perception, which may include issues of socialisation agents (family, peers, neighborhood/community, societal culture and media) and push forces for migration like the evaluation of opportunities in one's own country and in a foreign country. Therefore, future studies may further investigate the factors that shape migrants' attitudes. Hence, by first focusing on the inward, we move to the outward. Looking inward helps researchers to understand the dynamics of migration decisions. For example, there is evidence that poverty may not necessarily drive the decision for unsafe migration. At times we may also wonder why people migrate under the likelihood of trafficking. Part of the explanation is related to the attitudes and risk perceptions of migrants. So risk perception and attitudes are vital for judgment and decision. There is also a need to disentangle the mindset of migrants.

A first key implication is that actors in preventing unsafe migration in Ethiopia have to focus on the attitude/mindset of migrants to bring meaningful change. Second, as findings suggest, some Ethiopians are willing to put themselves in harm's way. So, working to change their attitudes that contribute to these dangerous decisions is important. However, it is also imperative to respect a person's culture while attempting to raise awareness. For example, if a person holds the belief that their life is in God's hands and is predestined, it is important to acknowledge that paradigm from which they operate and not dismiss it. Carl Rogers' (1957; 1959) person-centered approach may be of value as it acknowledges that in order for change to occur, there needs to be a mismatch between a person's experience and awareness, and that person needs to feel to to be understood. Translating this idea to the context of migration, to raise awareness about the potential dangers of migration, we may need to point out the differences between a person's experience and their attitudes while making sure we acknowledge and validate the culture and context they function within. Finally, more studies are needed to examine both what shapes Ethiopians' attitudes toward illegal migration and how their attitudes also (re)shape the decisions they make about migration.

References

Abebaw, M. 2013. Experiences of Trafficking Returnee Domestic Workers from the Gulf States: Implicationsfor Policy and Intervention.PhD Dissertation, Addis Abeba: School of Social Work, Addis Ababa University. [ Links ]

Abebaw, M. & Waganesh, Z. 2015. Re-conceptualizing human trafficking: The experiences of Ethiopian returnee migrants. Journal of Trafficking Organized Crime and Security, 1(1):9-23. [ Links ]

Adams, C. 2011.Re-trafficked victims: How a human rights approach can stop the cycle of re-victimization of sex trafficking victims. The George Washington International Law Review, 43: 201-234. [ Links ]

Addis Ababa University. 2015. Managing the socio-cultural, health, legal and economic dimensions of migration: Emphasis on Ethiopian migrants in the Middle East and South Africa. Abebaw, M. & Abera, T. (Eds.). Unpublished thematic research report, Addis Ababa.

Anbesse, B., Hanlon, C., Alem, A., Packer, S. & Whitley, R. 2009. Migration and mental health: A study of low-income Ethiopian women working in Middle Eastern countries. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 55(6): 557-568. [ Links ]

Animaw, A. 2011. Trafficking in Persons Overseas for Labor Purposes; The Case of Ethiopian Domestic Workers, Addis Ababa: ILO Country Office. [ Links ]

Bastide, L. 2015. Faith and uncertainty: Migrants' journeys between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. Health, Risk & Society, 17(3-4): 226-245. [ Links ]

Beck, A.T. 2006. How an anomalous finding led to a new system of psychotherapy. National Medicine, 12: 1139-1141. [ Links ]

Bhugra, D. 2004. Migration, distress and cultural identity. British Medical Bulletin, 69:129-141. [ Links ]

Biniam, T. 2012. Ethiopian Maids in a Severe Arab World. <allafrica.com> (retrieved 16 September 2012).

Blagbrough, J. 2008. Child domestic labor: A modern form of slavery. Children in Society, 22: 179-190. [ Links ]

Camlin, C.S., Hosegood, V., Newell, M., McGrath, N., Barnighausen, T. & Snow, R. 2010. Gender, migration and HIV in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLos One, 5(7): 115-139. [ Links ]

Chang-Muy, F. & Congress, E.P. 2009. Social Work with Immigrants and Refugees; Legal Issues, Clinical Skills, and Advocacy. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M. & Carciotto, S. (2015). International migration in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): A call for a global research agenda. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR). 1(2): 154-177. [ Links ]

Doherty, M.E. & Kurz, E.M. 1996. Social judgment theory. Thinking & Reasoning, 2: 109-140. [ Links ]

Eagly, A.H. & Chaiken, S. 1993. The Psychology of Attitudes. London: Harcourt Brace College Publishers. [ Links ]

Fernandez, B. 2013.Traffickers, brokers, employment agents, and social networks: The regulation of intermediaries in the migration of Ethiopian domestic workers to the Middle East. International Migration Review, 47(4): 814-843. [ Links ]

Friesender, C. 2007. Pathologies of security governance: Efforts against human trafficking in Europe. Security Dialogue, 38(3): 379-402. [ Links ]

Garrett, P., Coupland, N. & Williams, A. 2003. Investigating Language Attitudes: Social Meanings of Dialect, Ethnicity and Performance. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [ Links ]

Global Migration Data Analysis Center. 2015. Global Migration Trends Factsheet 2015. Berlin: GMDAC. [ Links ]

Gong, F., Xu, J., Fujishiro, K., Takeuchi, T.D. 2011. A life course perspective on migration and mental health among Asian Immigrants: The role of human agency. Social Science & Medicine 73: 1618-1626. [ Links ]

Gozdziak E.M. & MacDonnel, M. 2007. Closing the gaps: The need to improve identification and services to child victims of trafficking. Human Organization, 66(2):171-184. [ Links ]

Horwood, C. 2009. In Pursuit of the Southern Dream: Victims of Necessity, Assessment of the Irregular Movement of Men from East Africa and the Horn to South Africa. Geneva, Switzerland: IOM. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch. 2008. Sinai Perils Risks to Migrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers in Egypt and Israel. New York: Human Rights Watch. [ Links ]

International Organization for Migration. (IOM). 2006. National Counter-Trafficking Capacity Building Training. Manual for Prosecutors. IOM Special Liaison Mission in Ethiopia.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2014. Global Migration Trends: An Overview, Geneva: IOM Migration Research Division. [ Links ]

Jureidini, R. 2011. Mixed Migration Flows: Somali and Ethiopian Migration to Yemen and Turkey. Final report prepared for the Mixed Migration Task Force, Center for Migration and Refugee Studies, Cairo: American University.

Kangaspunta, J. 2007. Collecting data on human trafficking: Availability, reliability, and comparability of trafficking data. In: Savona, E.U. & Stefanizi, S. (Eds.). Measuring Human Trafficking: Complexities and Pitfalls.Italy, International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council: Springer Science, Business Media LLC, pp.27-36.

Kapiszewski, A. 2006. Arab versus Asian migrant workers in the GCC.UN expert group meeting on international migration and development in the Arab Region, UN-DESA, Beirut, May 15-17 2006.

Lansink, A. 2006. Human rights focus on trafficked women: An international law and feminist perspective. Agenda, Empowering Women for Gender Equity, 20(70):45-56. [ Links ]

Lutz, H. 2011. The new maids: Transnational women and the care economy. Zed Books, London

Marina, D.R. 2016. Time to look at girls: Adolescent girls' migration in Ethiopia. Research report. Terre Des Hommes, International Federation.

Marina D.R. & Medareshaw, T. 2015: Deported before experiencing the good sides of migration: Ethiopians returning from Saudi Arabia. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, DOI: 10.1080/17528631.2015.1083178.

Meskerem, M.2011. Psychosocial and Economic Experiences of Gulf States Returnee Ethiopian Women Domestic Workers. MA Thesis, Addis Ababa: Institute of Gender Studies, Addis Ababa University. [ Links ]

Mirsky, J. 2009. Mental health implications of migration: A review of mental health community studies on Russian-speaking immigrants in Israel. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44: 179-187. [ Links ]

MOLSA. 2013, April. Labor market information bulletin. Addis Ababa: Employment Service promotion Directorate, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, 73(8): 1169-1177.

Panayides, P. 2013. Coefficient alpha: Interpret with caution. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 9(4): 687-696. [ Links ]

Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat. 2014. Blinded by hopes: Attitude, knowledge and practice of Ethiopian migrants. Mixed migration research series, Kenya, Nairobi, Westlands.

Regional Mixed Migration Studies. 2014. The letter of the law: Regular and irregular migration in Saudi Arabia in a context of rapid change. Mixed migration research series, explaining people on the move, Nairobi, Kenya.

Rogers, C. 1957. The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2): 95-103. [ Links ]

Rogers, C. 1959. A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In: Koch, S. (Ed.).Psychology: A Study of a Science. Vol. 3 Formulations of the Person and the Social Context. New York: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Sharma, N. 2005. Anti-trafficking rhetoric and the making of a global apartheid. NWSA Journal of States of Insecurity and the Gendered Politics of Fear, 17(3): 88-111. [ Links ]

Sheeran, P., Montanaro, E., Bryan, A., Miles, E., Maki, A., Avishai-Yitshak, A., Klein, W.M.P., & Rothman, A.J. 2016. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 35(11): 1178-1188. [ Links ]

Sherif, M. & Hovland, C.I. 1980. Social Judgment: Assimilation and Contrast Effects in Communication and Attitude Change. Westport: Greenwood. [ Links ]

Sheriff, M.S. & Sherif C.W. 1968. Attitude as the individuals' own categories: The social judgment-involvement approach to attitude and attitude change. In: Sherif, M. & Sherif,C.W. (Eds.).Attitude, Ego-involvement, and Change. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 105-139. [ Links ]

Sherif, C.W., Sherif, M.S. & Nebergall, R.E. 1965. Attitude and Attitude Change. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. [ Links ]

Southey, G. 2011. The theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour applied to business decisions: A selective annotated bibliography. Journal of New Business Ideas & Trend, 9(1): 43-50. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2014. Documented Immigrants in South Africa. Statistics South Africa, Private Bag X 44, Pretoria 0001.

UNICEF. 2005. Trafficking in Human Beings, especially Women and Children, in Africa. (2ndEd). The UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre: United Nations Children's Fund.

UNODC. 2010. Organized Crime Involvement in Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants: Issue Paper. United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime.

United Nations (UN). 2000. Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children, Supplementing UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. Geneva: United Nations. [ Links ]

US Department of State. 2016. Trafficking in Persons Report. Washington DC: United States Department of State. [ Links ]

Waganesh, W., Abebaw, M. & Kangangn, G.2015. Mental health and somatic distress among Ethiopian migrant returnees from the Middle East. International Journal of Mental Health &Psychiatry, 1(2): 1-6. [ Links ]

Weine, S.M. & Kashuba, A. 2012. Labor migration and HIV risk: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS and Behavior, 16(6): 1605-1621. [ Links ]

Yaseen, H. 2012. Sudanese youth attitudes towards international migration: Case study of some Universities in Khartoum State. Ahfad Journal, 29(2): 108109. [ Links ]

Yoseph, E., Mebratu, G. & Belete, R. 2006. Assessment of trafficking in women and children in and from Ethiopia. IOM Special Liaison Mission, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.