Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.1 Cape Town Jan./Abr. 2017

ARTICLES

The Role of Trust and Migrant Investments in Diaspora-Homeland Development Relations

Leander Kandilige

Lecturer, Centre for Migration Studies, University of Ghana and Research Associate, Refugee Studies Centre, Department of International Development (QEH), University of Oxford. Email: lkandilige@ug.edu.gh

ABSTRACT

Research into the role of diaspora communities in origin countries' development is a growing phenomenon. However, there is little understanding of the role of trust in mediating transnational relationships between migrants and recipients of remittances (non-migrants, members of migrant households and community leaders). Using a case study methodology, mixed methods and a comparative approach - in-depth interviews with 40 key informants (20 in the UK and 20 in Ghana), 120 questionnaires administered in the UK and 346 questionnaires administered in Ghana - this paper examines differing conceptualisations of trust among 'development partners' in the process of negotiating as well as implementing migrant-funded development projects. It also examines the nature of investments of migrants in the origin country. Migrant respondents are from the Kwahuman Traditional Area and the Upper East Region of Ghana. Ghana is used as a case study to examine this phenomenon both from the perspective of the migrant and that of the origin country partners. Narratives by migrants are examined in order to unearth factors that inform their decision-making and the approaches they adopt to ensure accountability. Survey results are also used to highlight associations between key variables. The findings indicate that the bulk of the expenditure on productive activities by migrants takes place outside of household circles. Consequently, productive uses of migrant remittances are grossly under-reported due to a lack of trust between migrants and beneficiaries in the origin country.

Keywords: trust, diaspora, development, hometown associations, diaspora-homeland relations.

Introduction

Globally, migration of people across national borders has increased for a variety of reasons. Recent statistics indicate that approximately 244 million international migrants participated in this process in 2015 (UNDESA, 2016).

This substantial number of international migrants is associated with equally considerable amounts of remittances. Global remittance flows totalled about $601 billion in 2015, with developing countries receiving about $441 billion, according to the World Bank (2016).

As migrant populations congregate in common destination locations, some of them coalesce around common symbols of identity and belonging. With time, this strength of association increases as members of migrant communities (from a common origin) feel that they are not fully accepted by the destination community and they develop a nostalgic feeling about their roles in helping develop their communities of origin. These migrant communities, over time, are designated as 'diaspora' in recognition of their deliberate decision to assert their rootedness in their societies of origin. Diaspora relations with the homeland are constructed as mostly positive in terms of the potential development resources that could be granted to origin countries (Castles et al., 2014; Kandilige, 2012; Mohan, 2008). However, in some circumstances, diaspora groups are perceived as potential security threats to both the origin and destination countries due to their sometimes non-transparent and activist relations within their homelands (Baser, 2015).

These two perspectives highlight the value of trust in the sustenance of mutually beneficial relations between diasporas and their homelands. This paper seeks to examine the shifting bases and prerequisites of trust building and consider the prospects of replicating these structures in a transnational setting. The concept of transnationalism refers to "the process by which transmigrants, through their daily activities, forge and sustain multi-stranded social, economic, and political relations that link their societies of origin and settlement, and through which they create transnational social fields that cross national borders" (Basch et al., 1994: 7). The discussion is framed around the key questions: What is the role of trust in micro and meso level interpersonal relationships? How do 'lower level' trust relationships feed into the transnational setting? What are the prospects and/or dilemmas for transnational trust to work in practice? A multiple case study methodology and mixed methods approaches were adopted in the collection and analysis of primary data (Bryman, 2012; Teye, 2012).

The paper is arranged into five main sections. After this introduction, the different interpretations of the concept of diaspora are assessed. An attempt is made to define development from both the perspective of human wellbeing and that of traditional market-focused economics. In addition, the concept of trust is examined in order to highlight its role in fostering relations between diaspora members and development partners in home countries. Secondly, a review of diaspora-homeland relations in Ghana is presented in order to highlight general perspectives on the role of the diaspora in Ghana's development. Thirdly, the methodology adopted for study is discussed. Fourthly, findings on the experiences of Ghanaian migrants in the UK are presented in order to highlight the impact of trust deficit in diaspora-homeland relations at the transnational level. Lastly, conclusions are drawn based on the migrants' narratives and perspectives from partners in the origin country.

Conceptualising Diaspora, Development and Trust

Defining Diaspora

The term diaspora has been subjected to multiple definitions in the social sciences. For instance, it has been used as a figurative designation to describe alien residents, expellees, political refugees, expatriates, migrants and ethnic and racial minorities (Safran, 1991). Commonness of place of origin, source of identity and mode of dispersion (voluntary or involuntary) of "diasporans" (Vertovec, 2006) characterise the Ghanaian diaspora. Place of origin is sometimes defined at different spatial levels by migrants. As a result, the national attribute of 'Ghanaianess' serves as a higher identifying characteristic to migrants in a foreign country than their ethnic or clan affiliations. Cohen (1997; 2008) sub-divides diaspora into "victim," "trade" and "labour" diaspora in an attempt to reflect the different reasons that sometimes inform migration decisions in the first instance. The first wave of Ghanaian emigrants in the mid-1960s migrated for economic reasons to other West and Southern African countries (Anarfi & Kwankye, 2003) and formed "labour" and "trade" diasporas. The second substantial wave of emigrants fled the country during periods of political upheaval in the late 1970s and 1980s. Over time, these individuals coalesced into a "victim" diaspora in countries such as the United Kingdom, the USA and Canada. Contemporary movements comprise of mostly labour migrants and this cohort of emigrants has bolstered the Ghanaian labour diaspora.

Scholars such as Safran (1991: 83-84) insist on specific characteristics that a given society must possess before being described as a diaspora. Going by Safran's (1991) detailed set of requirements, the Ghanaian migrant communities abroad might not fulfil all of the criteria. However, others such as Clifford (1994) and Dufoix (2008) advocate a more liberal approach.

Clifford (1994: 305), for instance, acknowledges that "societies may wax and wane in diasporism." This alludes to the organic nature of feelings of attachment to the homeland, depending on existential factors in migrant communities' relations with their destination countries. Dufoix (2008: 19-34) also points out that diasporas should not be perceived as pre-existing groups that have static features that meet or do not meet specific academic criteria, but rather that they can be "heterogeneous populations that are selfconsciously imagined" and developed into collectives through "the projects of emigres and states."

Marienstras (1989: 125) introduces a temporal dimension to diaspora formation. In line with this, Koser (2003) refers to the Ghanaian diaspora as a "neo-diaspora," based on its relative newness compared to others such as the classic Jewish diaspora. Kleist (2008), however, argues against what she perceives as the undue focus on migrant communities defined by dispersion and, rather, proposes that the term diaspora should be conceptualised as "a concept of a political nature that might be at once claimed by and attributed to different groups and subjects" (Kleist, 2008: 308). Ghanaians abroad increasingly claim the label 'diaspora' as a political statement of their affinity to a country experiencing socio-economic development partly attributable to the discovery and production of oil and a sustained period of democracy (Wong, 2013). Conversely, the government of Ghana attributes the label 'diaspora' to nationals abroad with an aim of attracting development resources. In spite of discrepancies in how diaspora is conceptualised, the commonalities in definitions refer to individuals that form a community outside of their country of origin due to a range of factors and are either unable or unwilling to return 'home' on a permanent basis, but hold the prospect of doing so in the future. These are also people who perceive a sense of belonging to and a need to contribute to the development of their origin country. In the case of Ghana, nationals living abroad have routinely attempted to have both virtual and physical presence in the country's development agenda. However, there is no common understanding of what the 'development' they seek to contribute to entails, how this endeavour could be realised and under what conditions.

Defining Development

The association between diaspora and homeland development could, therefore, vary depending on how 'development' is defined. Both scholars and practitioners have subjected the concept of development to multiple interpretations. For instance, within the field of migration studies, Basok (2003) defines development to include activities linked to economic growth-related variables - such as the generation of employment and increase in agricultural production - and welfare-related variables, such as reduction of poverty, increase in average income and decrease in inequality.

Others note that development needs to be examined closely through the prism of agency-oriented interpretations of human wellbeing (de Haas, 2009; Sen, 1999; Nussbaum, 1992; Griffin, 1986). This conceptualisation is markedly different from definitions by classical development economists such as Rostow (1960) and Lewis (1955), who measure development by economic growth, especially the increase in market activities. On his part, Amartya Sen (1999) argues that the prime focus of development discourses should be on how to maximise substantive freedoms such as access to education, good nutrition, shelter, political participation and healthcare. He perceives these freedoms as basic yet integral to any claims of development. This perspective of development is consistent with that of Dudley Seers (1969) who famously defined development as "the reduction and elimination of poverty, inequality and unemployment within a growing economy." Ghana has been lower middle-income country since 2011, with an economic growth rate of 14.4 percent in 2011 that made it one of the fastest growing countries in the world, boasting a US$1,580 per capita income and one of the highest GDP per capita in West Africa. Despite this, Ghana continues to experience inequalities, especially between the northern and southern regions of the country (Osei-Assibey, 2013).

As de Haas (2009: 5) aptly concludes, development is not only a complex multi-dimensional concept, but can also be assessed and analysed at different levels and has varying meanings within different normative, cultural and historical contexts. How the seemingly uncontroversial concept of development is defined has implications in terms of engendering trust between the promoters and beneficiaries of that development. Diasporas, as agents of development, do not imply a carte blanche relationship with development partners in origin countries. Trust is critical.

Defining Trust

Just as with the concepts of development and diaspora, trust means different things to different scholars. Mohan (2006), for instance, situates trust within the broader concept of obligation. He examines this within Parekh's (1996: 264) conceptualisation of obligation as "social actions that the moral agent ought to undertake and his failure to do which reflects badly on him and renders him liable to social disapproval." Within this interpretation of obligation, the moral agent is defined flexibly to include the migrant, nonmigrant or former migrant who is expected to be self-critical and conscious of the impact of his or her actions on society. Failure to deliver on their socially prescribed obligations leads to the lost of credibility and incurs social disapproval. Within the Ghanaian context, at the local and community levels, interpersonal relations and social transactions are characterised by mutually dependent social obligations. As such, Mohan (2006) regards trust as central to the mutual exchange of resources and information among ascribed ethnic groupings in Ghana. Lyon (2000: 665) further notes that the sources of these socially prescribed obligations are located in "reputations, sanctions and moral norms." However, what are the prospects of (re)producing these obligations in a transnational setting?

In discussing transnational activities of Cameroonian and Tanzanian home associations, Mercer et al. (2009) cite examples of how the absence of transnational trust sometimes leads to tensions between migrants and home community members, particularly around community development projects. Therefore, the authors perceive trust as key in sustaining both the negotiation and implementation of such projects. More importantly, Smith and Mazzucato's (2009: 669) work conceptualises trust in transnational relationships as stemming from long-standing relationships created through shared past experiences and reciprocal economic and social investments in one another. They note that relationships of trust established between migrants and friends are freer from social obligations than those with family relations. According to Smith and Mazzucato, when transactions fail, it is easier to apply sanctions on friends than on family members, due to a feeling of entitlement on the part of family members.

The different conceptualisations of trust ultimately form a subset of the broader discourses on "social capital" (Putnam, 2000) and are used to guide the Ghanaian case study in order to unearth the particular challenges migrants face in negotiating the preconditions of trust within a transnational setting.

Perceptions on Diaspora-Homeland Development

The diaspora is increasingly being courted as a potential development partner in Ghana (Kandilige, 2012; Mohan, 2008). As a result, specifically earmarked contributions by the diaspora have been incorporated into recent national development plans in the country (for instance, see: NDPC, 2015; NDPC, 2010; NDPC, 2005). At a practical level, diaspora-homeland relations find expression in the political rhetoric, civil society discourses, legislative enactments and initiatives by international development agencies such as the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The aspirations of the political elites in encouraging an increased role for the Ghanaian diaspora can be captured by two important observations. The first one is by a former Ghanaian president, John Agyekum Kufuor:

I must acknowledge the contributions made by our compatriots who live outside the country... Many of you do more than send money home, many of you have kept up keen interest in the affairs at home and some of you have even been part of the struggle of the past twenty years (Mohan, 2006).

The second is by a former Minister of Finance, Osafo-Maafo:

May I humbly invite Ghanaians overseas to use the natural advantage they have over their home based countrymen such as proximity and access to the latest technology, foreign exchange, reliable export markets and partners with know-how to begin to make direct investment into our economy (Mohan, 2008).

Both quotes point to an appreciation of the transnational nature of international migration and the possible opportunities that could be exploited by the homeland through its 'extraterritorial' citizens (Baubock, 2003; Escobar, 2007; Castles et al., 2014). Within the transnational theory, cash and social remittances are acknowledged as important development tools at the disposal of homelands without any express requirement on migrants to return to their countries of origin on a permanent basis. This is a significant departure from previously popular complaints by leaders of developing countries about the "development of underdevelopment" (Binford, 2003; Lipton, 1980) due to brain drain and the 'poaching' of skilled African migrants by the developed 'core' countries (Pang et al., 2002; Desai et al., 2002; Voigt-Graf, 2008; Chanda, 2001; Dovlo & Nyonator, 1999).

These pronouncements are backed by policy formulations and events that have tended to facilitate diaspora engagement processes.* Ghana drafted a National Migration Policy in 2014 (launched in April 2016) in order to effectively manage migration in a way that yields positive development outcomes. In addition, a Diaspora Support Unit was created in 2012, under the auspices of the country's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration. Its specific responsibility was to identify and provide the needed support to the Ghanaian diaspora purposely to increase their interest in national development. This Unit was later upgraded to a Bureau (Diaspora Affairs Bureau) in 2014 - a possible sign of an even greater appreciation of the role of the diaspora in national development. Another concrete step has been the initiation of the process of drafting a national Diaspora Engagement Policy (started in 2015), drawing on the expertise of the Centre for Migration Studies at the University of Ghana and other development partners such as the IOM, the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) and ECOWAS.

The transmission of what Peggy Levitt (1996) refers to as social remittances to Ghana by members of the diaspora has also been hugely significant. These have included the transfer of ideas, behaviours, practices and social capital accrued from destination countries. These transfers have been executed by individual members of the Ghanaian diaspora as well as facilitated by international organisations such as the IOM and the UNDP. Individual social remittances have included ideas on democratic governance, transparency and accountability, human rights, punctuality, work ethics and assertiveness, among others. In addition, social capital derived from their membership of business and epistemic networks abroad have enabled the Ghanaian diaspora to promote transnational investments and collaborations in Ghana (Kandilige, 2012).

Equally noteworthy is the role of international agencies (especially the IOM and UNDP) that have initiated projects such as the knowledge transfer programmes for the purposes of bolstering socio-economic development in the country. A classic example is the Migration for Development in Africa (MIDA) initiative launched by the IOM in 2001 to assist in the transfer of critical skills and resources of the African diaspora to their countries of origin. Ghana benefited from the circulation of competencies, expertise and experience of the Ghanaian diaspora (Faist, 2008). Another example is the UNDP's programme referred to as the Transfer of Knowledge through Expatriate Nationals (TOKTEN). This mechanism allowed for the tapping of professional skills of expatriate Ghanaians through the means of short-term consultancies in Ghana.

In terms of cash remittances, Ghana has recorded year-on-year increases in the volume of remittances, which has consistently surpassed the ratio of some 'macro' variables such as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Overseas Development Aid (ODA) to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). For the period from 1990 to 2003, Bank of Ghana data suggest that private unrequited transfers had a significant impact on the country's GDP. As a percentage of GDP, remittances increased from about 2 per cent in 1990 to about 13 per cent in 2003, and also increased from 22 per cent to almost 40 per cent as a percentage of total exports earnings (Addison, 2004). There was a similar trend of year-on-year increases in the aggregate volume of cash remittances from 2004 to 2014. The Bank of Ghana recorded a rise in remittances from $1.2 billion in 2004, to over $1.9 billion in 2008, to $2.1 billion in 2014, to $4.9 billion in 2015 (Bank of Ghana, 2015; Kandilige, 2012; Bank of Ghana, 2016). The injection of such cash contributions could support economic development in the origin country.

However, as the Human Development Report (UNDP, 2009: 71) notes, "impacts are complex, context-specific and subject to change over time." For development to be triggered in Ghana as a result of diaspora activities, it depends to a large extent on the internal dynamics in the country. As de Haas (2009: 52) concludes, migrants and their remittances can neither be expected to "trigger take-off development nor be blamed for a lack of development in fundamentally unattractive investment environments."

Methodology and Methods

A multiple case study research methodology, involving two different geographical areas in Ghana, was adopted to guide this study. The context and processes involved in the activities of members of two Ghanaian hometown associations (Kwahuman Association and Kasena-Nankana Development League) based in the UK were analysed. This enabled a measurement of their peculiarities as well as similarities. These two hometown associations represent the Eastern and Upper East regions of Ghana, respectively. This kind of research strategy has firm roots in classic studies in other social science disciplines (Burgess, 1983; Cavendish, 1982; Sassen, 2006).

Mixed methods were adopted for this study that allowed for the triangulation of results and complementarity of techniques (Bryman, 2012). The selection of respondents from the two regions was actualised by tracing leads from migrants belonging to the two selected hometown associations to their home regions in Ghana. Migrant associations provided information on their contacts and partners in the origin communities and they were interviewed for more information on the nature of and basis for their collaborations with migrants.

The overall logic of the methodology adopted was to glean quantitative data on frequencies, associations, patterns and proportions in addition to qualitative data that helped provide an in-depth explanation for behaviours, decisions and reactions by respondents.

The innovation in this study partly stems from the fact that it was conducted in both the origin and destination communities in order to build a holistic perspective on the concept of trust, rather than the single-sited approach often embraced by most migration researchers (Werbner, 2002; Osili, 2004; Mohan, 2006; Mercer et al., 2009).

The first stage of the study was carried out in the Greater London area (especially the boroughs of Southwark, Lambeth, Newham, Hackney, Haringey, Lewisham, Croydon and Brent). The main reason for the choice of these boroughs was that most Ghanaian migrants are based there (COMPAS, 2004). The second phase was conducted in the Upper East and Eastern regions of Ghana. The Upper East Region is among the poorest of the ten regions of Ghana. It is located in the north, and accounts for comparatively fewer migrants. The Eastern Region is much richer and, located in the south-eastern part of the country, it accounts for one of the largest sources of Ghanaian migrants outside of the African continent (Kandilige, 2012). The differences in economic affluence, migration prevalence and geographical location are important because they provide apt comparative parameters.

The fieldwork in the Greater London area included in-depth interviews with twenty key informants from the Ghanaian migrant community, participant observation activities, informal conversations and the administration of 120 questionnaires. The aims of these data collection strategies were to gauge, among others, migrants' participation in group activities, their transnational support to local communities, their main partners in the origin community, challenges they face and the value they place on the concept of trust in their transnational relationships.

The Ghana fieldwork included 20 in-depth interviews with local chiefs, District Chief Executives (local government officials), community development leaders and executive members of local hometown associations (located in urban centres). These interviews focused on how development projects are negotiated with migrants abroad (the UK), how they are implemented, the role of the origin communities in local development, their perceptions on the effects of collective remittances on poverty alleviation and income redistribution and possible new areas of collaboration with migrants. All interviews were conducted personally by the author and at respondents' homes, places of work, restaurants or pubs. In order to gauge the perception of the beneficiary communities, 346 questionnaires were administered among heads of migrant households (246 in the Kwahu Traditional Area and 118 in the Upper East Region). Of these, 66 per cent were male and 34 per cent were female.

The data presented in this paper are from a bigger project** carried out over fifteen-months. The paper is based on the narratives of respondents from the two hometown associations and their development partners in Ghana as well as some survey statistics.

Findings

Trust as A Critical Component in Diaspora-Homeland Relations: The Case Of Ghana

This section examines the concept of trust between diasporas and their homelands by using the experiences of Ghanaian migrants in the UK and their local partners as a case study. These are analysed under four main sections: knowledge about the types of investments migrants make, engaging family/relatives to carry out projects, migrants' individual experiences and hometown associations' group experiences of initiating and executing migrant-funded projects.

Knowledge about Investments in General

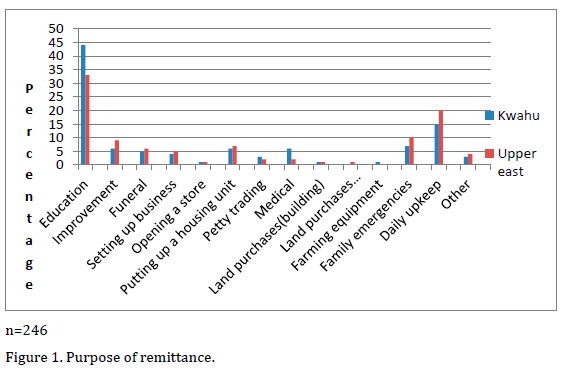

Empirical research among 364 migrant households in Ghana indicates that the bulk of remittances received, according to heads of migrant households, were predominantly used to pay for education, daily upkeep and solving family emergencies (see Figure 1). Almost 44 per cent and 34 per cent of respondents in Kwahu Traditional Area and the Upper East Region, respectively, reported using remittances for education purposes. This is consistent with international research, which also suggests a positive relationship between remittances and educational attainment and enrolment (Rapoport & Docquier, 2005; Cox-Edwards & Ureta, 2003).

There was, however, a discrepancy between what migrants themselves and heads of migrant households claimed about how remittances were actually spent. On the one hand, heads of migrant households generally claimed that the bulk of remittances were spent on 'consumptive' expenditures (Connell & Conway, 2000). On the other hand, migrants indicated that only a small percentage of their total remittances were sent to migrant households for such 'consumptive' expenditures. So what accounts for this apparent disjuncture? There could be a myriad of reasons for this disparity but the most common refrain by migrants was that they did not trust their families or relatives in Ghana to run their businesses honestly and properly and, as a result, failed to declare such projects to them. This suggests that some heads of migrant households were either not informed about some of the business ventures and investments ('productive' expenditures) their migrant relatives own in Ghana, or were aware but not involved in the running of such ventures. To test this assertion, an analysis of the number of migrants who had funded, already set up or were in the process of setting up businesses in Ghana was carried out. Where 32 per cent of respondents (migrants in the UK) reported having funded, set up or were in the process of setting up businesses in Ghana, less than 9 per cent of heads of migrant households in Ghana reported that their migrant relatives had made such 'productive' investments. This implies that the bulk of the expenditure on 'productive' activities by migrants takes place outside of household circles.

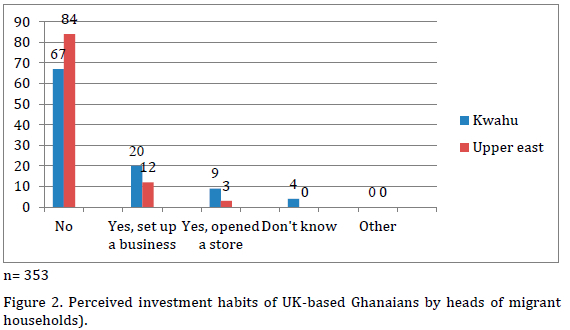

Furthermore, when a direct question was posed on investment in 'productive' activities in general, up to 84 per cent of respondents (heads of migrant households) in the Upper East Region and 67 per cent in the Kwahu Traditional Area believed that their transnational relatives had neither businesses nor stores in Ghana (see Figure 2). This marked disparity suggests the need for empirical research into the relationship between remittances and development to consider both the perceptions of the receiving households or communities and the views of the migrants themselves. This is critical because a lop-sided examination of the extent of migrant investments in homelands, only from the perspective of heads of migrant households without a matched sample from migrants, is likely to underestimate the magnitude of 'productive' investments.

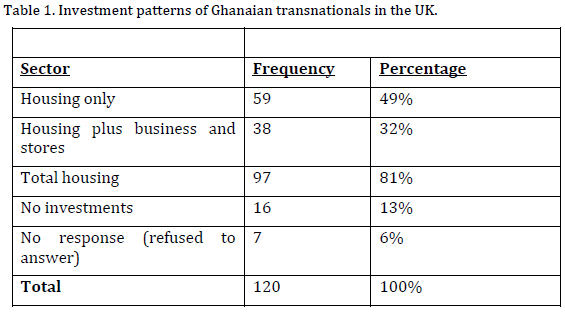

Knowledge about Investments in Housing and Residential Arrangements of Migrants

International empirical research suggests that a large proportion of remittances are spent on housing-related expenditure in migrants' home countries, generally. This has been the case in countries such as Morocco, where between 71 per cent (de Haas, 2003) and 84 per cent (Hamdouch, 2000) of remittances have been spent on housing, and Egypt where 54 per cent of remittances are spent on housing (Adams Jr., 1991). Also, Osili (2004) reported that a large proportion of remittance income to Nigeria is spent on housing. He concludes that a ten (10) per cent increase in remittance income in Nigeria raises the probability of investing in housing by three (3) percentage points. Consistent with these high percentages, the study found that over 81 per cent of respondents in the UK had investments in either private housing or real estate development as a business (see Table 1). Additionally, more than a third of the UK respondents have either set up or were in the process of setting up a business or a store in Ghana.

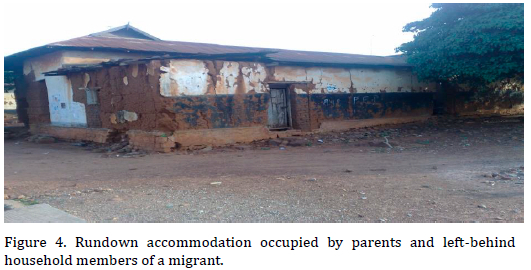

Beyond some productive investment interests of Ghanaian migrants being concealed from members of their immediate families, there also appear to be gaps in knowledge about the residential arrangements of migrants in the origin community. There has been an appreciable chunk of migration literature on the apparent conspicuous nature of migrants' investments in housing, especially second houses (Mohan, 2006; de Haas, 2007; Fadloullah et al., 2000 in de Haas, 2009 and Van der Geest, 1998). These residential edifices are preserved as a sign of prestige by migrants and only occupied very occasionally when they are on holiday to the origin community or when they are attending special events such as funerals, weddings, anniversaries or religious and cultural celebrations. A classic example exists in the residential arrangements of one migrant (Kojo) from the Kwahu Traditional Area in the Eastern Region of Ghana, who owns a spacious six-bedroom house (see Figure 3) on an exclusive migrants' residential enclave. This property contains three washrooms, two living rooms, a mini bar and two garages, among other amenities. Interestingly, up to ten months in a year, a caretaker occupies this 'mansion.' Kojo's UK-based nuclear family only visits Kwahu over the Easter festive period to participate in paragliding and some cultural celebrations. In contrast, Kojo's mother, eight siblings, nephews and nieces all live in a rundown mud house (see Figure 4) located two towns away from the migrants' residential enclave. He indicates that his family in Ghana is unaware of the existence of his opulent house and that his decision to keep it a secret stems from his anxiety over likely excessive demands for money by members of his left-behind household (see Mohan, 2008; Henry & Mohan, 2003), requests from them to occupy his property on a 'temporary' basis and his fear of envious neighbours and family members killing him using juju (voodoo). This is an extreme example of trust deficit in migrant-homeland relations. However, it is another example of the difficulty of sustaining trust relations in a transnational context. Kojo's account challenges Smith and Mazzucato's (2009) conceptualisation of trust since in spite of the long-lasting relationship between Kojo and his family in Ghana, which should have informed a reciprocal economic and social investment from him, he fails to replicate this at the transnational level. He, however, trusts an outsider (caretaker) over his family, in line with Smith and Mazzucato's views that social obligations are freer with outsiders than with family members and sanctions are easier to apply on outsiders. Within Parekh's (1996) conceptualisation of obligation, Kojo's actions have the propensity to be judged negatively by his community and to incur social disapproval.

Trust Deficit in Supervisory Roles

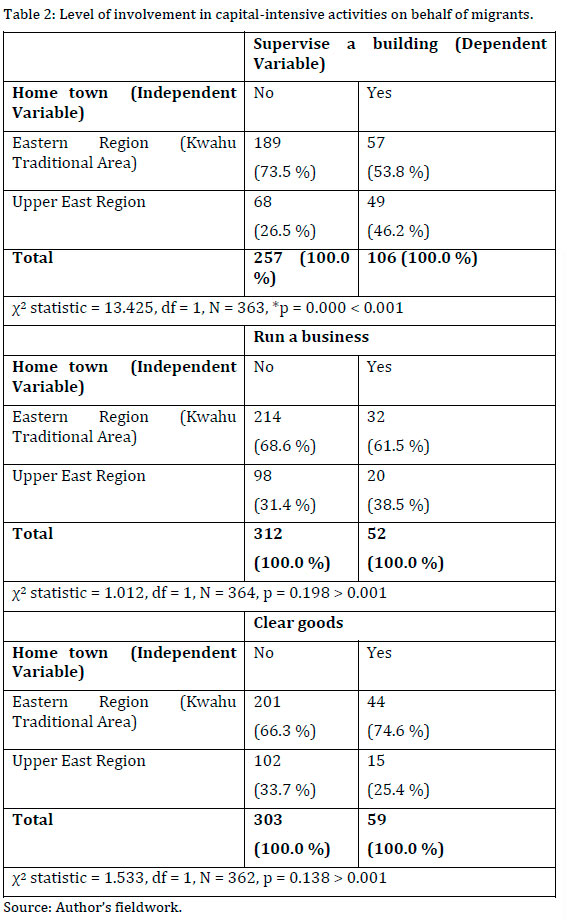

Misgivings expressed by migrants about informing members of their left-behind households of their investment interests are further corroborated by survey results among migrant households in Ghana in three main areas (running of businesses on behalf of migrants, supervising building projects and clearing goods from harbours). These areas are selected as important in testing the level of migrants' trust in their families and relatives in Ghana, because they are activities that involve large amounts of capital or cash transactions. Less than 20 per cent of heads of migrant households reported any involvement in the running of businesses or clearing of goods on behalf of their relatives in the UK. The supervision of building projects, whilst slightly higher than the other two activities, still accounts for less than half of all cases (see Table 2). These total figures are slightly lower than in cases of city-based migrant household members where up to half are involved in supervising housing construction for migrants, according to previous research (Mazzucato, 2011: 460). The increasing reliance on friends, associates and former work colleagues to supervise projects and to conduct business transactions on behalf of migrants is again consistent with Smith and Mazzucato's (2009) assertion that obligations with 'outsiders' are freer than those with family members.

However, beyond the absolute percentages of heads of migrant households who are involved in the three key activities, inferential statistics (chi-square test) is used to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference between the two regions in terms of the level of trust. The results (Table 2) show that there is a statistically significant association between migrants' trust in relatives to supervise their buildings and the hometown of the migrant, χ2 (1, N= 363) = 13.425, p < 0.001). However, the results (Table 2) indicate that there is no statistically significant association between migrants' trust in relatives to run a business for them and the hometown of the migrant, χ2 (1, N= 364) = 1.012, p > 0.001). Furthermore, the results demonstrate that there is no statistically significant association between migrants' trust in relatives to clear goods for them and the hometown of the migrant, χ2 (1, N= 362) = 1.533, p > 0.001).

Trust: Migrants' Personal Experiences

Several Ghanaian migrants in the UK genuinely feel let down by their own family and relatives and have resorted to relying on help from friends and former colleagues to run and manage their businesses and building projects (see also Smith & Mazzucato, 2009: 667-669). This seems to account for the marked disparity in the perceptions of members of migrant households and the reality on volumes of 'productive' investments undertaken by migrants. Personal accounts help contextualise the levels of mistrust. For instance, 'Ibrahim's' own sister misappropriated his funds:

When I started [a housing project], I gave my sister 30 million [Cedis] to start but when the old man died and I went home, I asked her where's the house and she said she spent the money... My own sister, one mother one father (sic). No! So I don't allow them to go even near my things (56 year-old male migrant, Upper East Region).

'Yaw' was also cheated and betrayed by his relative:

That has been a problem honestly ... it started off with my sister-in-law she actually bought the land and you know Ghana the way they are, I even realised that they inflated the price of the land like five times. Then she told me the boyfriend was a contractor. When I was sending the money they were not even using the money to do the project, she was now using it for her own thing. So I had to get rid of that contractor, get another person to do it, so the initial money I spent was just wasted (61 year-old female migrant, Eastern Region).

These two quotes demonstrate the sense of frustration and despair that characterise some relations between migrants and their kin. Family members and relatives are expected by society to observe relations that Parekh (1996) conceptualises as relations of obligation. Failure to adhere to these socially constructed obligations reflects badly on them and attracts social disapproval. Accounts of outright disregard for the investment capital of migrants, some of whom have experienced incidents of discrimination and racism in the host country (see Herbert et al., 2006), have engendered a feeling of resignation on the part of some migrants. This despair is evident in what a female migrant from the Kwahu Traditional Area had to say:

You can't help Ghanaians. That's one thing you just cannot. Honestly they take too much advantage and they think we don't know what goes on, we do. Even though we've been away from the country for a long time, we still know what goes on (Secretary of the Kwahuman Association, UK).

Similar expressions of doubt and mistrust discourage some migrants from investing in the origin country altogether. Some of those migrants who invest in private accommodation units reported either using the services of private real estate developers to construct their houses or purchasing already built houses in an attempt to avoid embezzlement of funds by family relations.

That is the difficult side of it. As I said you send them money and they embezzle it so it is difficult for us people living over here to put up houses because your own brother or sister or best friend that you trust to do something for you will clean you out (58-year old female migrant, UK).

Trust: Experiences of Migrant Collectives Versus Homeland Partners

Feelings of mistrust are a double-edged sword and examples of such feelings also exist from the perspective the origin country. In-depth interviews with chiefs, community development leaders and members of local-based hometown associations in Ghana suggest both cordial relations with migrants in the process of negotiation and implementation of migrant-funded community-based projects, but also tensions between migrants and home communities. On the one hand, instances of prior discussions between migrants and local stakeholders as well as collaborative work have been recorded. These were more prominent among the Kwahuman Association members and their Ghanaian partners. Examples include detailed discussions of proposed projects in origin communities between migrants and traditional leaders during migrant-funded overseas trips by traditional chiefs.

They sometimes invite Nana [the chief] and his elders to visit the UK but especially Holland and the USA. They pay for all their travel expenses so that Nana and his elders will go over to brief them on what is going on, on the ground. They then fundraise and send the money to support whatever projects they agree on (Linguist to the Paramount Chief, Abene, Eastern Region).

Such cordial deliberations have helped cement relations between members of the Ghanaian diaspora and development partners from their origin communities. These negotiations form a basis for the transfer of both cash and in-kind collective remittances towards community development. For that matter, projects supported are not dissimilar to those reported from other research among the Cameroonian diaspora (Mercer et al., 2009), Pakistani diaspora (Werbner, 2002), Mexican diaspora (Smith, 2003) and Moroccan diaspora (de Haas, 2007). These mostly include the donation of used medical equipment, educational materials, street lighting, potable water and computing equipment, the renovation of old public buildings and the setting up of scholarships for local students. Two examples of donations to health facilities are provided:

They [migrants] used to send clinic or hospital equipment especially beds, mattresses, wardrobes and other materials that are being used at the hospital. The other day they brought some one or two containers full of hospital equipment alone (sic) ... They brought incubators, bicycles for people with cardiovascular problems and so on and they are all at the hospital now (Chief of Abetifi, Kwahu, Eastern Region).

They brought about 50 sets of beds. The chief gave them a place to store them and when some are broken then they go and replace them from the stores. Secondly, an electric plant was donated to the clinic, a generator to the clinic so that when the lights go off they can use it. When the machine arrived they called Nana [the chief] and everyone in the town and he inaugurated it. We the local association here in Abetifi have also built a shed to cover it in order to protect it from the elements (Sub-Chief of Abetifi, Kwahu, Eastern Region).

On the other hand, mistrust is manifested, transnationally, in differences in the value placed on remittances by origin partners as opposed to diaspora members. Origin partners complain of over-estimation of the value of collective remittances sent by members of the diaspora and a lack of appreciation for the magnitude of contributions made by local-based hometown associations towards community development. Diaspora members are accused of placing unreasonable demands on local counterparts. This feeling is demonstrated in two quotes from representatives of two migrant communities in Ghana.

I actually run into problems with the people in the UK. If you send $100 or £100 and you think that it is a lot, and that's for the year. When I gave an example of how much my wife and I alone have contributed to development of our town, they took offence but I was just doing some analysis. When you compare their earnings and ours, they should be doing more. So they [migrants abroad] should not feel that if they send £100 that is so much money (Chairman of a local hometown association, Upper East Region of Ghana).

I think they [migrants abroad] brought in $2000. At that time it was the equivalent of about 16 Million Cedis. When you hear 16 Million Cedis it sounds big but when it goes to the ground it can't do much (sic). So sometimes that is the problem we have with them [migrants] because they find it difficult to understand why they bring in the money and they don't see what it has been used for. Because they could not understand this, they refused to top it up and since we were also having our different projects going on, we were not be able to raise extra money to do what they wanted us to do (Community Development Leader, Kwahu, Eastern Region).

Migrant collectives (hometown associations), however, insist that their incredulities or suspicions are based on actual experiences of cases of embezzlement of collective remittances by some local counterparts. There are also accounts of lack of transparency in the selection of community representatives and the refusal by others to publicly acknowledge receipt of collective remittances (see Mercer et al., 2009). A representative of the one of the selected hometown associations in the UK aptly portrays these claims in the following statement:

Yes, that was a good plan to build a big roof supermarket...So we started with stage one which according to them the government of Ghana had given them about 350 million Cedis so we donated 170 million Cedis which, you know, will come to half a billion to start the project. They were rushing us. Our people ordered me to go and present to them the 170 million Cedis, which was the equivalent of £10,000 at that time and the money is gone astray! (Treasurer, Kwahuman Association, UK).

Members of migrant collectives also hold their origin country partners to a high standard of openness and accountability in line with socialised values, probably cultivated in the host country (the UK). Some migrant groups demand legitimacy and representativeness of local community groups as a condition for continued funding. This assertion is partly borne out by demands such as these:

I demanded certain guarantees from them because I needed to make sure that the election of people onto that committee was fair and that whatever they did they had a constitution that guided them as to, you know, what they wanted to work on, and I wasn't really impressed with the fact that they were just hand picking people to sit on it. So I decided to kind of step back for now . I've worked in this kind of area for many years here in the UK so I am fairly aware of what can go wrong if you don't get the group or groups set up properly with the right representation. You could cause lots of problems (52-year old female migrant, Upper East Region).

In addition, migrants request evidence of receipt and use of collective remittances as a monitoring tool but also as a useful advertisement to future donors. Forms of evidence range from audio clips of radio broadcasts, footage of TV coverage, photographs in print media or on the internet and formal acknowledgement of receipt in writing on headed paper by development partners. Failure to deliver on these requests sometimes leads to mistrust and frustration on the part of migrants. These socially prescribed obligations are located in "reputations, sanctions and moral norms" (Lyon, 2000: 665). This is captured in the remarks made by one fundraiser for the Kwahuman Association:

The reason I haven't continued to fundraise is, you know, when you collect this fundraising money these people [British] they want evidence to see that you haven't spent the money. So initially I sent £500 to them [local partners] so now I'm waiting for them even to send me a picture to prove we've done the foundation or we've done this or that. Every time I phone, I don't get any word from them (sic) (61-year old female migrant fundraiser, Eastern Region).

Cases of mistrust emanating from lack of publicity on migrants' collective remittances are not limited to the Ghanaian context. An instructive example exists in Mercer et al.'s (2009: 154) account on Cameroonian and Tanzanian home associations. According to them, the Bali Cultural and Development Association, UK (BCDA-UK) cut its links with the Bali Nyonga Development and Cultural Association (BANDECA) in the homeland because the BANDECA's water department had failed to acknowledge the BCDA-UK's donation of 500,000 CFA francs (about £500) in its published list of donors.

Conclusion

This paper has highlighted the limited involvement of familial relations in the execution of productive investments that are funded by diaspora members. While a substantial proportion of remittances are directed at funding the cost of education, healthcare and daily upkeep of migrant households in origin communities, the paper demonstrates that the bulk of expenditure on 'productive activities' takes place outside of household circles. Even though 'consumptive expenditure' could generate long-term multiplier effects beyond the immediate recipients (de Haas, 2005), 'productive expenditure' yields direct, immediate effects on job creation and improvements in living standards. This questions the scope of New Economics of Labour Migration theorists' interpretations of the household as the most appropriate unit of analysis of migration as a livelihood strategy. Lack of trust towards family members has negative implications on the potential of remittances as household poverty alleviating resources.

The paper also finds that there are some similarities in the preconditions and basis of constructing trust in social relations both within the local and transnational contexts. As Lyon (2000: 665) notes, fundamental sources of socially prescribed obligations are located in "reputations, sanctions and moral norms." The risk of reputational damage, imposition of social sanctions (real or perceived) and the ascribed normative culture form the basis of trust within the local sphere. These prerequisites are equally valid in the transnational context but geographical proximity and the attendant immediacy of effects of social sanctions on the social actor engender greater intensity in trust relations locally compared to transnationally.

Also, Parekh's (1996: 264) conceptualisation of obligation as "social actions that the moral agent ought to undertake and his failure to do which reflects badly on him and renders him liable to social disapproval," has limited application in the transnational context. While social actions around the provision of consumptive goods are critical in migrants' transnational interrelationships, substantial productive investments are broadly based on "long-standing relationships created through shared past experiences and also reciprocal economic and social investments in one another" (Smith & Mazzucato, 2009: 669). These transnational relationships do not have to be familial. To this extent, how much of the estimated $601 billion remitted globally in 2015, out of which $441 billion went to developing countries (World Bank, 2016), was actually directed at productive uses? This and the level of involvement of migrant households in managing productive investments ensuing from these remittances are difficult to ascertain by conducting single-sited empirical research only among migrant households in origin countries.

The Ghana example is instructive as well as illustrative of the nuances that international/intergovernmental development agencies, such as the UNDP, the IOM, the World Bank, the European Union (EU) governments and others, need to bear in mind when advocating for a greater role for diasporas as development partners in the developing country context. A firm appreciation of the complex dynamics in establishing and sustaining trust relationships transnationally is critical to the success and viability of institutional interventions within the migration-development nexus framework. Ultimately, there is a need for a reconceptualisation of the role of migrants beyond the narrow and undifferentiated prescriptions attributed to them by intergovernmental organisations and international financial institutions.

References

Adams, R. Jr. 1991. The Effects of International Remittances on Poverty, Inequality and Development in Rural Egypt. Research Report 86. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. [ Links ]

Addison, E.K.Y. 2004. The Macroeconomics Impact of Remittances, Bank of Ghana. AITE (2004) Consumer Money Transfers: Powering Global Remittances.

Anarfi, J. and Kwankye, S. 2003. Migration from and to Ghana: A Background Paper. University of Sussex: DRC on Migration, Globalisation and Poverty.

Bank of Ghana. 2016. Remittances and unrequited transfers for 2015. Research Department. From: <http://www.bog.gov.gh> (retrieved November 20 2016).

Bank of Ghana. 2015. Remittances and unrequited transfers for 2014. Research Department. From: <http://www.bog.gov.gh> (retrieved November 5 2015)

Baser, B. 2015. Diasporas and Homeland Conflicts: A Comparative Perspective. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

Basch, L., Schiller G.N. and Szanton-Blanc, C. 1994. Nations unbound: Transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized Nation-States. Langhorne, PA: Gordon & Breach. [ Links ]

Basok, T. 2003. Mexican seasonal migration to Canada and development: A community based comparison. International Migration, 41(2): 1-26. [ Links ]

Baubock, R. 2003. Towards a political theory of migrant transnationalism. International Migration Review 37(3): 700-723. [ Links ]

Binford, L. 2003. Migrant remittances and (under) development in Mexico. Critique of Anthropology, 23: 305-336. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Burgess, R.G. 1983. Inside Comprehensive Education: A Study of Bishop McGregor School. London: Methuen. [ Links ]

Castles, S., de Haas, H. and Miller M.J. 2014. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements on the Modern World. Houndmills Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Cavendish, R. 1982. Women on the Line. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Chanda, R. 2001. Trade in health services. Paper WG4: 5, Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. <http://bit.ly/2nX4TLL> (retrieved 10 May 2014).

Clifford, J. 1994. Diasporas. Cultural Anthropology, 9(3): 305-6. [ Links ]

Cohen, R. 1997. Global Diasporas: An Introduction. London: UCLA Press. [ Links ]

Cohen, R. 2008. Global Diasporas: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

COMPAS Report Team. 2004. The contribution of UK-based diasporas to development and poverty reduction. Oxford, ERSC Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS). [ Links ]

Connell, J. and Conway, D. 2000. Migration and remittances in island microstates: A comparative perspective on the South Pacific and the Caribbean. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(1): 52-78. [ Links ]

Cox Edwards, A. & Ureta, M. 2003. International migration, remittances, and schooling: Evidence from El Salvador. Journal of Development Economics, 72(2): 429-61. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2009. Mobility and Human Development. Human development research paper, UNDP Human Development Reports. UNDP.

De Haas, H. 2007. The Impact of International Migration on Social and Economic Development in Moroccan Sending Regions: A Review of Empirical Literature. Working Paper No.3, University of Oxford: International Migration Institute (IMI).

De Haas, H. 2005. International Migration, Remittances and Development: Myths and Facts. Third World Quarterly, 26(8): 1269-1284. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2003. Migration and Development in Southern Morocco: The Disparate Socio-Economic Impacts of out-migration on the Todgha Oasis Valley. Ph.D. Thesis, Catholic University of Nijmegen. [ Links ]

Desai, M.A., Kapur, D. & McHale, J. 2002. Sharing the spoils: taxing international human capital flows. Updated version of the paper presented. Paper No. 02-06, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University. <https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/sites/casi.sas.upenn.edu/files/bio/uploads/Sharing_the_Spoils.pdf>

Dovlo, D. & Nyonator F. 1999. Migration of graduates of the University of Ghana Medical School: A preliminary rapid appraisal. Human Resources for Health Development Journal, 3(1): 34-37. [ Links ]

Dufoix, S. 2008. Diasporas. Berkeley, CA & London: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Escobar, C. 2007. Extraterritorial political rights and dual citizenship in Latin America. Latin American Research Review, 42(3): 43-75. [ Links ]

Faist, T. 2008. Migrants as transnational development agents: an inquiry into the newest round of the migration-development nexus. Population, Space and Place, (14): 21-42. [ Links ]

Griffin, J.P. 1986. Well-Being: Its Meaning, Measurement and Moral Importance. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Henry, L. and Mohan, G. 2003. Making homes: The Ghanaian diaspora, institutions and development. Journal of International Development, 15: pp. 611-622. [ Links ]

Hamdouch, B. 2000. The remittances of Moroccan emigrants and their usage. In: OECD. 2005. The Development Dimension: Migration, Remittance and Development. Paris: OECD Publishing. [ Links ]

Herbert, J., Datta, K., Evans, Y., May, J., McIlwaine, C. & Wills, J. 2006. Multiculturalism at Work: The Experiences of Ghanaians in London. London: Department of Geography, Queen Mary, University of London. [ Links ]

Kandilige, L. 2012. Transnationalism and the Ghanaian Diaspora in the UK: Regional Inequalities and the Developmental Effects of Remittances at the Sub-NationalLlevel. DPhil. Thesis, University of Oxford. [ Links ]

Kleist, N. 2008. Mobilising 'the diaspora': Somali transnational political engagement. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(2): 307-323. [ Links ]

Koser, K. 2003. New African diasporas: An introduction. In: Koser, K. (Ed.). New African Diasporas. London: Routledge, pp. 1-16. [ Links ]

Levitt, P. 1996. Social Remittances: A Conceptual Tool for Understanding Migration and Development. From <http://bit.ly/2p0k7ij> (retrieved 12 May 2009).

Lewis, W.A. 1955. The Theory of Economic Growth. London: George Allen and Unwin. [ Links ]

Lipton, M. 1980. Migration from the rural areas of poor countries: The impact on rural productivity and income distribution. World Development, 8: 1-24. [ Links ]

Lyon, F. 2000. Trust, networks and norms: The creation of social capital in agricultural economies of Ghana. World Development, 28: 663-68. [ Links ]

Marienstras, R. 1989. On the notion of diaspora. In: Chaliand, G. (Ed.). Minority Peoples in the Age of Nation-States. London: Pluto, pp. 119-125. [ Links ]

Mazzucato, V. 2011. Reverse remittances in the migration-development nexus: two-way flows between Ghana and the Netherlands. Population, Space and Place, 17(5): 454-68. [ Links ]

Mercer, C., Page, B. & Evans, M. 2009. Unsettling connections: Transnational networks, development and African home associations. Global Networks, 9(2): 141-161. [ Links ]

Mohan, G. 2006. Embedded cosmopolitanism and the politics of obligation: The Ghanaian diaspora and development. Environment and Planning A., 38: 867-883. [ Links ]

Mohan, G. 2008. Making neoliberal states of development: The Ghanaian diaspora and the politics of homelands. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26: 464-479. [ Links ]

NDPC. 2015. Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA) II, 2014-2017, medium-term national development policy framework. Republic of Ghana.

NDPC. 2010. Guidelines for the preparation of district medium-term development plans: Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA I) 2010-2013. Republic of Ghana.

NDPC. 2005. Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS II) (2006-2009). Republic of Ghana.

Nussbaum, M.C. 1992. Human functioning and social justice: In defence of Aristotelian essentialism. Political Theory, 20: 202-246. [ Links ]

Osei-Assibey, E. 2013. Inequalities in Ghana: nature, causes, challenges and prospects. The heart of the Post-2015 development agenda and the future we want for all. Final draft report for the Post-2015 Development Agenda: Ghana Inequalities Group Team.

Osili, U.O. 2004. Migrants and housing investments: Theory and evidence from Nigeria. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 52(4): 821-849. [ Links ]

Pang, T., Lansang, M.A. & Haines, A. 2002. Brain drain and health professionals: A global problem needs global solutions. British Medical Journal, 324: 499-500. [ Links ]

Parekh, B. 1996. Citizenship and political obligation. In: King, P. (Ed.). Socialism and the Common Good. London: Frank Cass, pp. 259-289. [ Links ]

Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Rapoport, H. & Docquier, F. 2005. The Economics of Migrants' Remittances. IZA Discussion Paper no. 1531.

Rostow, W.W. 1960. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Safran, W. 1991. Diasporas in modern societies: myths of homeland and return. Diaspora, 1: 83-99. [ Links ]

Sassen, S. 2006. Territory, Authority Rights: From Medieval to Global Assemblages. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Seers, D. 1969. The meaning of development, Institute of Development Studies Communications 44. [ Links ]

Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books. [ Links ]

Smith, R.C. 2003. Migrant membership as an instituted process: Transnationalization, the state and the extra-territorial conduct of Mexican politics. International Migration Review, 37(2): 297-343. [ Links ]

Smith, L. & Mazzucato, V. 2009. Constructing homes, building relationships: Migrant investments in houses. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geographie, 100(5): 662-673. [ Links ]

Teye, J.K. 2012. Benefits, challenges and dynamism of positionalities associated with mixed methods research in developing countries: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 6(4), 379-391. [ Links ]

UNDESA. 2016. Monitoring global population trends. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

UNDP. 2009. Overcoming barriers: Human mobility and development. Human Development Report 2009. New York: UNDP. [ Links ]

Van der Geest, S. 1998. "Yebisa Wo Fie": Growing old and building houses in the Akan culture of Ghana. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 13: 333-359. [ Links ]

Vertovec, S. 2006. Transnational Challenges to the 'New' Multiculturalism. University of Oxford: Oxford Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS).

Voigt-Graf, C. 2008. Migration, labour markets and development in PICs. Paper presented at the Conference on Pathways, Circuits and Crossroads in Wellington, June 9-11. 'New Research on Population, Migration and Community Dynamics.'

Werbner, P. 2002. Imagined Diasporas among Manchester Muslims. Santa Fe, NM: SAR Press. [ Links ]

Wong, M. 2013. Navigating return: the gendered geographies of skilled return migration to Ghana. Global Networks, 14 (4): 438-457. [ Links ]

World Bank. 2016. Migration and Remittances Factbook 2016. 3rd Edition. World Bank Group.

* The Homecoming Summit in 2001; the Dual Citizenship Act [Act, 591, Republic of Ghana, 2002]; establishment of the Non- Resident Ghanaian Secretariat in 2004; the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre [promotion of Tourism] Instrument, 2005 [L.I. 1817]; the Representation of the Peoples [Amendment] Act [Act 699, Republic of Ghana, 2006] and the Investment Summit in 2007).

** This project was among members of the Ghanaian diaspora in the UK and heads of migrant households in Ghana, community leaders and Ghanaian political elites, the Bank of Ghana, Ghana Statistical Service and the Department of National Archives. The UK component of the bigger study comprised of interviews with 20 key informants, a survey of 120 Ghanaian migrants, participant-observation activities and library research. The Ghana component involved a survey of 346 heads of migrant households, interviews with 20 key informants (community leaders and political elites), data from the Bank of Ghana, Ghana Statistical Service and the Department of National Archives.