Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.2 no.3 Cape Town 2016

ARTICLES

Nowhere to Run: A Review of the Political Economy of Migration, Identity and Xenophobic Violence in Zambia

Phineas BbaalaI; Njekwa MateII

IDepartment of Political and Administrative Studies, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, the University of Zambia. Email: pbbaala@gmail.com

IILecturer at the University of Zambia

ABSTRACT

Zambia is one of the Southern African countries that have not witnessed any serious bloody conflicts either in their post-independence eras or the periods hitherto. Consequently, the country has, over the years, provided refuge to many victims of ethnic and racial conflicts from other African countries, especially within the Sub-Saharan African region. However, Zambia faces the daunting challenge of sustaining interregional, interethnic and interracial harmony among its own indigenous groups and those identified as foreign immigrants. The April 2016 xenophobic looting of shops belonging to other African nationals by residents of Lusaka highlighted the intensification of ethnic and racial conflict in the country. Amid these identity conflicts, some commentators from different intellectual and other persuasions have tried to explain ethnic and racial identity problems in relation to primordial, constructive and instrumental theoretical underpinnings. This article goes further to draw a relationship between economic downturn and identity and xenophobic violence. The article draws arguments from a review of existing literature and empirical data.

Keywords: Migration, identity, ethnicity, racism, regionalism, xenophobia.

Introduction

This article attempts to interrogate the deepening ethnic and racial divide in Zambia. Until recently, most scholarly works on Zambia have exclusively focused on ethnic conflicts among the country's major tribal groups. However, the occasion of the April xenophobic attacks by Zambians, mainly involving the looting of shops belonging to Rwandan and Congolese immigrants, necessitated this article. From the onset, one must state that international law obliges Zambia to provide shelter to refugees and other people of concern who are forcibly displaced from their home countries. The major pieces of international law that require Zambia to fulfil this obligation include the 1991 United Nations Convention, the 1967 United Nations Protocol and the 1979 Organisation of African Unity Conversion (UNHCR, 1991:4). Forcibly displaced people, although usually referred to as 'refugees,' can be further classified in accordance with their specific migration status and the nature of help they are seeking in the host country. According to the UNHCR (2009), these include asylum-seekers, internally displaced persons (IDPs), returned refugees and returned internally displaced persons, among others. Collectively, all forcibly displaced people who require help of one kind or another in other countries are collectively referred to as people or populations of concern.

In order to proceed systematically, after this introduction this paper attempts to theorise and historicise the challenges of migration, identity and xenophobic violence in Zambia. While the background section highlights some of the elicit moments in the fomentation of ethnic and racial hatred in the country, the section on theoretical review evaluates the efficacy of some of the key conceptual arguments in explaining the causes of growing ethnic violence and xenophobia in Zambia. Thereafter, a synoptic trend of the migration situation in Sub-Saharan Africa in general and Zambia in particular is given. This is followed by a discussion of Zambia's identity conflict within the country's political economy. Within this, an account of the April 2016 xenophobic violence is given. The article discusses the political economy of identity in Zambia with the argument that the heightening ethnic and racial hatred in the country is a result of deliberate politicisation and economisation of construed social differentiation by a small but powerful rent-seeking politico-economic elite class. Then, the article concludes and recommends measures for fostering ethnic and racial harmony in Zambia.

Migration has occurred throughout human history as people move from one place to another in search of a better life. A migrant is a person who changes his usual place of residence by crossing an administrative boundary and residing or intending to stay in a new area for a period of not less than six months (CSO, 2013: 1). The movements of people internally and externally have been influenced by a number of factors some of which are presented here in no order of their importance. Firstly, individuals are sometimes driven out of their countries because of high costs of living and poor or declining economies that prevent them from living a decent life. In such a situation, the migrant targets a country that they perceive will provide an improved quality of life for themselves and/or their families. Secondly, people may be forced out of their countries for political reasons. Experiences of political violence or any related threats may influence some people to flee their countries for their own safety and/or that of their family members. Thirdly, others may be forced to flee their countries on religious grounds. Today, religious conflict has led to some people being attacked or killed, thereby triggering the movement of the oppressed to regions or countries in which they feel they will be able to freely practice their religion without any or much victimisation. Fourthly, ethnic divisions have in many occasions throughout the world led to some people migrating to safe havens. This has occurred when one group dominates the other(s) in some aspects of life (i.e. political, economic or social), thus leading to the exclusion of the dominated group, which consequently triggers identity conflict.

Another related concept discussed in this paper is identity. Identity is the mechanism through which we locate ourselves in relation to the social world. Identity links the self with its social context. Identity exists in many forms, that is, cultural, national and ethnic, among others. Following Stuart Hall, Baldacchino (2011) considers identity as an impossibility born out of the psychic and discursive suturing processes of identification. Ethnicity, as a category of identity, cannot be viewed as existing in any sense, or as a substitute of culture for that matter. Ethnicity is composed of an interaction between the self and the other, intra-psychically just as much as inter-subjectivity.

This paper, therefore, is an effort towards a plausible explanation of how political, economic and social rent-seeking in the destination country could adversely affect the safety of immigrants. It presents widely drawn examples while focusing on Zambia

Background

The Republic of Zambia, born on 24 October 1964 when it gained independence from Britain, has gone through many politico-economic and social junctures. Most noticeable among these was the period prior to the arrival of the British South Africa (BSA) Company and the one leading up to independence. Before Cecil Rhodes' commercial interests pushed the BSA Company into mineral exploration ventures deep in the interior of the territory north of the Zambezi River (now called Zambia), there existed human communities defined and organised largely around their biological, tribal, language and other associations of blood and soil. Most importantly, nearly all of the tribal groups that inhibited the territory were either immigrants escaping from other hostile groups or wanderers into new territories in search of new opportunities that nature could offer. For this reason, most of Zambia's major ethnic groups that include the Lozi, Nyanja, Bemba and Tonga, are immigrants. For instance, the Lozi and Bemba came from the Luba-Lunda Kingdom, while the Nyanja group escaped Shaka Zulu's wars of dispersal in modern day South Africa. Although the Lozi and Tonga, and the Ngoni (a part of the Nyanja group) and Bemba once fought during their migration between the 17th and 19th centuries, these groups eventually established their own ethnic nations existing side by side in relative peace. In fact, the former nemeses later introduced a system of inter-ethnic cousinship in which they jokingly tease one other without taking offense. This type of cousinship exits between the Lozi and Tonga, and Nyanja and Bemba groups (Bbaala and Momba, 2015:2).

Notwithstanding the fact that inter-ethnic cousinship has catalysed inter-ethnic harmony among former ethnic rivals, it has, itself, become a new source of identity conflicts as groups that play ethnic cousinship have tended to identify more with each other than with other ethnic groups. Over the years, Zambia has witnessed the clustering together of those of similar language and culture, and the emergence of ethnic stereotypes (Gluckman, 1960:55-70; Mitchell, 1956 cited in Dresang, 1974:1605-1617). As argued later in this article, cleavages of identity that are xenophobic in nature have evolved over a very long period spanning from the pre-colonial era to the post-independence era, and they affect social and political participation (Bates, 1970:546-561).

Although ethnic cleavage and conflict existed in the pre-colonial Zambian society, xenophobic identity and conflict are mainly associated with the penetration of white settlers into the territory. The entry of the Europeans into the territory north of the Zambezi, as was the case in most other African lands, was met with resistance by the local people. Dehumanising practices emanating from slave trade, colonialism and the proclamation of white supremacy over Africans led to the resistance of the Europeans' penetration into the territory. The failure by the white settlers to appreciate the indigenous political, social and economic institutions, and their imposition of European institutions they regarded as superior, stirred racial identity and conflict. For instance, the Livingstone Mail, the first colonial newspaper ever published north of the Zambezi, was on many occasions, as observed by Kasoma (1986:21), used to spearhead hate against the indigenous Blacks. The paper once carried a story that read: "The races can never mix, they are divided as East is from the West," and that Blacks were dirty people from whom the Whites were to keep away (Livingstone Mail, 1949 cited in Kasoma, 1986:21). Even those Africans who had eventually begun to adopt the European way of life were not spared from racial segregation. In Livingstone, one of the earliest growing urban centres that also served as the Headquarters of North-western Rhodesia, some Africans had started working as shop-keepers. However, the introduction of an industrial Colour Bar by the white settlers ensured that Africans were relegated to those jobs that the whites disliked for being dirty, hard or dangerous (Gann, 1958:60-62).

There were many other legal and structural mechanisms in which the white settlers segregated against the Africans, including the operation of a social, economic and political system orchestrated to promote white dominance over other races. The treatment of people according to the colour of their skin was an institutionalised public policy under white rule. Consequently, different Rhodesian racial groups such as the Africans (or the Bantu as referred to by Gann), the minority Indians, Arabs and coloureds (or as they were otherwise called, the half-caste), were treated differently under the obtaining public policy and regulations at the time. As Gann (1958:175-191) points out, this social stratification system was dehumanising, especially to the Africans, and was designed to serve the interests of the minority white settlers in Northern Rhodesia. Particularly, as argued by Rodney (1976:250), colonial powers sometimes saw the value of stimulating tribal [and other identity] jealousies so as to keep the colonised from dealing with their principal contradiction with the European overloads. It is also worth noting that the colonialists did not only create social strata based on the major racial groups found in Northern Rhodesia. They also stratified the major local indigenous groups based on certain stereotypes. Additionally, they treated each regional-ethnic group according to the stereotype they had given it. For example, the Nyanja were viewed as methodical and clerical, the Tonga as rural and conservative, the Bemba as tough and hardworking, and the Lozi as proud and intelligent (Dresang, 1974:1605-1617). Although such identity tags were beneficial to the colonialists, they effectively sowed the seed of ethnic and racial hatred, the repercussions of which were to transcend the colonial period.

With increased political awakening owing to the activities of the African liberation movement in Northern Rhodesia - which was initially led solely by the African National Congress (ANC), and later jointly with the United National Independence Party (UNIP) - Europeans started conceding some rights to Africans. For instance, some constitutional amendments between 1948 and 1958 brought in a clause that ostensibly stipulated that the interest of one race of the community could not be subordinated to those of any other race (Mulenga, 2011:4). Notwithstanding this, inter alia, some isolated incidents of violence against the white minority were recorded in some parts of Northern Rhodesia, especially during what Mulenga terms "The Violent Sixties." Specifically, he refers to three important events in the period of 1960-1961. One of these events was the violent attack and murder of Mrs. Lily Burton by a group of drunken UNIP youths returning from a party meeting outside Ndola. Details were that the car in which Mrs. Burton and her two daughters were travelling was attacked using a petrol bomb. Mrs. Burton managed to save her children but not herself and died from her wounds days later (Mulenga, 2011: 6).

However, the period leading up to independence unequivocally revealed that as much as colonial rule remained the common enemy, the African was his own enemy given the emerging tribal identity conflicts among leaders in the African nationalist movement. Disagreements within the Africans nationalist movement, the ANC, led to a split among the nationalist leaders that culminated in the formation of another big nationalist party, the Zambia African National Congress (ZANC), in October 1958. The ZANC was later renamed the UNIP. This followed consultations among the young radicals of the party who felt that the ANC leader, Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula, was not determined enough to fight for independence (Sardanis, 2014:89). However, much of the literature on this subject fails to mention that this split of the nationalist movement was actually an act of ethnic repositioning among the nationalist leaders. This argument is supported by the fact that most of those who went to found or join the UNIP, including Kenneth David Kaunda, could easily be identified with the Bemba ethnic group and the north-eastern region, while those who remained in the ANC, including Nkumbula, were mainly associated with the Tonga ethnic group and the north-western region.

Ironically, as evidenced by most of the major elections before and after independence, ethno-regional identity, as an electoral factor, has seemingly taken precedence over more important characteristics in choosing national leaders. Undoubtedly, this has been detrimental to the development of the country, especially in the post-independence period. Each of the key African political parties has tended to perform well in regions associated with the ethnicity of its key leaders and has recorded poor results in regions dominated by other ethnic groups. Specific incidents of ethnic-based identity and conflict are discussed later.

Theoretical Review of Identity and Xenophobia

Although ethnicity as an academic subject has received deserved attention global scholarship over the decades, it remains of growing interest owing to the new twists that it keeps assuming in changing political environments in different countries. In a nutshell, one can say that ethnicity is like a tree with many roots and branches, where the roots are the multiple causes and forms of ethnicity while the branches are the ethnic identities (or cleavages) as reflected by different ethnic groups.

When theorising ethnicity, one should underscore the primacy of 'identity.' All ethnicity problems are identity problems. Consequently, any good investigation into ethnicity tries to analyse the variables that define it. But what is identity? An individual's referent group, region, language, tribe, race, colour, religion, profession, lifestyle, inter alia, constitute his or her identity. Osaghae and Suberu (2005), view identity as any group attribute that provides recognition or definition, reference, affinity, coherence and meaning for individual members of the group, acting individually or collectively. By the same token, ethnic identity becomes a basis of ethnic hatred and xenophobia against those with whom one does not identify. Any study of ethnicity requires an in-depth analysis of its various patterns, precipitants and purposes. At this point, the paper examines the various patterns of ethnic identity and xenophobia.

Some scholars like Norris and Mattes (2003:8) view ethnicity as an enveloping term for many different forms of identity. In their view, ethnicity is an encompassing concept that one cannot define by any single demographic variable in a society. They contend that in some societies, ethnic identity may signify blood relations among members of an extended family or kinship based in a particular region. In other societies, ethnic identity may be an expression of common soil, faith, community affiliation or ancestry. Thus, individuals hailing from the same sub-territory of the country may identify themselves with a particular ethno-regional-lingual group. Joireman (2003:9), defines ethnicity by outlining features characteristic of an ethnic group, namely: i) proper name, ii) myth, true or false, of a common ancestry, iii) shared historical memories, iv) common culture defined by language, customs or religion, v) link to a geographical homeland and vi) sense of solidarity toward fellow members of the group. The preceding definitions clearly depict regionalism as a subset or a pattern of ethnicity. As stated in the preceding arguments, regional solidarity may also exist among members of different tribal groups who share a geographical homeland.

In debating ethnicity, other scholars such as Edward Shils, Cliford Geertz, Harold Isaacs and Walker Connor have presented arguments based on a theory called primordialism. Geertz (1963) cited in Bacova (1998:29-43), credited as founder of the theory, defines primordial attachment [or identity] as stemming from the "givens" or, more precisely, the assumed "givens" of social existence of humans. Geertz (1963) cited in Bacova (1998:29-43) further argues that:

'givenness' is immediate contiguity and kin connection but also being born into a particular community, religion, culture, then it is the mother tongue, and sharing the same social practices. [He] states that the congruities of blood, speech, beliefs, attitudes [and] customs are perceived by people as inexpressible and at the same time overpowering per se. One is bound to one's kinship, one's neighbour, one's fellow believer, ipso facto, as the result not only of personal affection, practical necessity, common interest, or obligation, but in great part by virtue of some absolute importance attributed to the very tie itself.

These natural and deep characteristics that imbue primordial identity entail an intense bondage between a member and their ethnic group. Cleavage to the group values and shared interests is thus likely to be as strong as the need to stand against external dilution. It also means that members of a given ethnic group are naturally divided from those belonging to other groups, meaning that interethnic group conflict is a naturally occurring phenomenon, especially since a person usually does not choose their blood relations and the other key ethnic neighbourhood elements at birth.

Critics of the primordial theory have often looked elsewhere for plausible explanations for the nature and causes of ethnic conflicts in countries. Consequently, other theories thought to underpin and explain ethnic conflicts have been espoused. The most important of these are the theories of constructivism and instrumentalism. Although the use of constructivist methods can be traced back to the works of philosopher Socrates, it is the Swiss psychologist, Jean Piaget (1896-1980) who is accredited with the invention of this theory in his attempt to explain how people know what they know. Other scholars who have been popularly identified as constructivist include Michael Hechter, Charles Tily, Ernest Gellner, Donald Horowitz, and for some unknown reasons, most feminist authors on ethnicity. Under the constructivist interpretation of ethnic identity, an individuals' cleavages or identities are constructed (and reconstructed), flexible, mutable and a product of society (Yang, 2000:39-60 cited in Boon, 2015:8). A constructivist sees social reality as a product of human socialisation, or at times, compromise.

Social institutions such as the media, churches, mosques, traditional initiation ceremonies, formal educational institutions, political parties, inter alia and opinion leaders play an important role in the construction of what one believes as social reality. For this reason, Samuels (2013:153 cited in Boon, 2015:8) and other scholars believe that political [or ethnic] identities are acquired and variable.

Wendt (1994:72) believes that an individual's identity and reality are constituted by the ideational or cognitive structures that humans as social actors are exposed to, meaning that certain characteristics exhibited by individuals would be absent in the void of these institutions. Ethnic identity or behaviour is, therefore, a product of the structures within or to which an individual is socialised. Based on this perspective, it could be said that primordial characteristics are typical of a primitive society in which its members have little or no interaction with an external world or languish in cognitive deprivation and backwardness. This means that with time and more exposure to new external social constructs of reality, a person is bound to learn new ideals and shift their beliefs about reality and identity.

Another theory that has been used to contextualise and explain ethnicity is instrumentalism. Unlike in the primordial and constructivist paradigms where ethnic identity is natural and constructed, respectively, instrumentalists argue that an individual's social identity and conflict is a result of struggle for power by some elite elements in society. Power is sought not as an end in itself but as an effective means to material ends. Bacova (1998:29-43) rightly observes that, in instrumental attachments, individuals' affiliations are stimulated by their desire to gain advantages (mostly economic and political). An important argument by the instrumentalists is the rejection of the primordial assertion that variations in ethnic attributes are the root causes of ethnic identity and conflict in society. To them, the cause of ethnic identity and conflict is rather the question of who gets what, when and how? Societies experiencing a higher incidence of inequality are, therefore, more prone to an instrumental type of ethnic identity and conflict than those considered more egalitarian. This view is shared by Stein (2011) who further acknowledges that although identities such as religion [or ethnicity] can play a part in violent conflict, they are merely "opium of the warriors" - a tool used by self-interested elites to mobilise support and fighting power for conflict. Stein sees instrumentalism as an agent-principal based approach in which power-seeking elites pursuing economic and political ambitions instrumentalise identity, [through ethnic consciousness], to manipulate and mobilise the masses in order to enhance the chances of attaining or defending class advantages.

Review of Identity and Xenophobia Trends

Over the years, the world has continued to witness increased displacement of people from the places they call home. By the end of 2015, 65.3 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide due to persecution, conflict, generalised violence and human rights violations. This reflects an increase in absolute terms of 5.8 million people over 2014, and represents the greatest level of forced displacement ever recorded (IOM, 2016: 5-20)

By the end of 2013, more than 232 million people globally were estimated to be migrants, of which 19 million were estimated to be in Africa. At the same time, some 42.5 million people worldwide were considered as displaced due to conflicts (36% refugees, 62% internally displaced persons (IDPs) and around 2% of individuals whose asylum applications remain to be adjudicated). Of these, nearly 2.7 million refugees were in Africa, constituting roughly 25% of the world's refugee population (UNHCR, 2016). Indeed, Africa remains a continent with complex migration dynamics. The continent is generally characterised by dynamic migratory patterns and has a long history of intra-regional as well as inter-regional migration flows. Conflict, income inequalities and environmental change can result in very low levels of human security that act as push factors for migration (IOM, 2014: 6-7).

The Southern African region experiences all types of movements including mixed and irregular migration, labour migration and displacement due to conflict and natural disasters. By virtue of its relative stability and economic opportunities, Southern Africa experiences a high volume of migration due to work opportunities in the mining, manufacturing and agricultural industries. The industrial development in some countries in the region - especially in South Africa, Botswana and Zambia - and the oil wealth of Angola, have been magnets for both skilled and unskilled labour migrants from within the region and elsewhere, notably from the Horn of Africa and West Africa. Southern Africa is also a springboard often used as the staging ground for regular and irregular migration to Europe and the Americas (IOM, 2014: 6-7). In 2013, the Southern African region recorded over four million migrants, excluding irregular migrants, of which 44% were female and 20% were under 19 years of age. By far, the largest number of migrants is found in South Africa (2.4 million, including some 1.5 million from Zimbabwe) followed by the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (447,000). Among the 4 million migrants are approximately 200,000 registered refugees primarily in the DRC and South Africa (IOM, 2014: 6-7). In May 2008, a wave of xenophobic attacks spread all over South Africa. More than 60 people, mainly citizens of Somalia, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, were killed by mob violence. Despite a subsequent solidarity campaign, the image of the South African rainbow nation was profoundly damaged and made the world, once again, aware of the growing inner-African sentiments against so-called foreigners (Kersting, 2009: 1). In his seminal work, Horowitz (2001 as cited by Kersting, 2009) analyses hundreds of lethal ethnic riots and related forms of xenophobia. He distinguishes between four reasons for such outbursts: firstly, an "ethnic" or "national" antagonism; secondly, a "reasonable" justification of violence; thirdly, a response to a certain event; and fourthly, aggression in a situation where the mob does not face any, or faces only a small risk of punishment.

A new dimension of globalisation has emerged with regards to migration. As a result of globalisation, the nation-state is said to be of diminishing relevance today. The global economic order, with its new information and communication technologies as well as its new transport systems, has greatly enhanced the mobility of capital and labour. Peter Vale, as cited by Desai (2008), has argued how in post-apartheid South Africa people's movement across borders has mutated "from local issue, to international and then, to security threat." The response from political leaders in response to allegations regarding xenophobia has often been denialism. This has triggered international migration on an unprecedented scale. On the other hand, national identities and local cultures are being reinvigorated. Strong nationalism may enhance in-group solidarity, but under certain conditions, it may also strengthen out-group hostility. Nationalism in sub-Saharan Africa was often regarded as another form of anti-colonial protest. Territorial nationalism, however, was often considered inauthentic because African states were delimited along 'artificial' (meaning: colonially imposed) boundaries, which fenced in multiple ethnic groups, and created territorial entities characterised by strong cultural heterogeneity. Jackson, as cited in Kersting (2009:6), points out that in the last couple of decades, the laws regulating citizenship and nationality have become more restrictive in African countries. Migrants have more frequently become victims of national campaigns and xenophobia and these "travellers in permanent transit" were demonised in Cameroon, Mozambique and Ghana as 'Zombies' (Nyamnjoh, 2006 cited in Kersting, 2009). In fact, most of the xenophobia in Africa is Afro-phobia. Although minorities, such as Chinese and Indians, face some forms of xenophobic discrimination such as the use derogatory terms such as "Chocholis" and "Bamwenye", respectively, most of the victims of xenophobia have been fellow Africans, particularly migrants from East African countries.

Migration Situation in Zambia: A Synoptic Account

Human mobility has always been a matter of global, regional and national interest. Migration, both in happy and sad moments, has social-cultural, political and economic consequences in both the departure and host countries. It is for this reason that most countries use their population policies as development tools. However, a country's population policy is prone to unplanned human mobility caused by unforeseen events within that country or other countries. Such occurrences as wars, persecution, social and economic crises, inter alia, are important catapults of human mobility in the world. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR, 2015) reports that at the end of 2014, there were 59.5 million forcibly displaced people in the world. Of these, 10 million were stateless while the rest were either refugees, asylum-seekers, internally displaced persons (IDPs), returned refugees, returned internally displaced persons or those classified as 'others.' The UNHCR (2015) further states that 42,500 people are forced to flee their homes every day because of conflict and persecution. The UNHCR statistics also show that 53% of the global refugee population comes from three countries namely Somalia (1.11 million), Afghanistan (2.59 million) and Syria (3.88 million). The leading refugee host countries in the world are Turkey (1.59 million) and Pakistan (1.51 million).

In Southern Africa, Zambia is one of the countries with a big refugee population. No sooner than it obtained independence did Zambia became host to the first influx of refugees. The United States (US) Department of State (2014) shows that as early as 1966, Zambia had started hosting Angolan refugees fleeing the armed conflict between the Popular Liberation Movement of Angola (MPLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). In 2010, the UNHCR put the number of persons of concern in Zambia at 51,856. These are distributed as follows: Refugees (25,578), asylum-seekers (2,186), returnees (1,640) and others (22,452) (UNHCR, 2016). In order to cater for the population of forced immigrants, Zambia, with the help of the UNHCR, operates six major camps and settlements. Each of these was strategically established to cater for the refugees originating from specific hot spots. For instance, Ukwimi in Eastern Province, established between 1987 and 1989 (UNHCR, 1991: 5), was a reaction to the influx of refugees escaping the bloody clashes between the rival fighters belonging to the Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO) and Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO). Maheba, situated in North-Western Zambia overlooks Angola, which has witnessed one of the longest armed conflicts in the region. Other camps and centres are the Mayukwayukwa and Nangweshi in the Western Province, Kala in Luapula Province and Mwange in the Northern Province. Both Kala and Mwange have mainly serviced refugee inflows from the DRC.

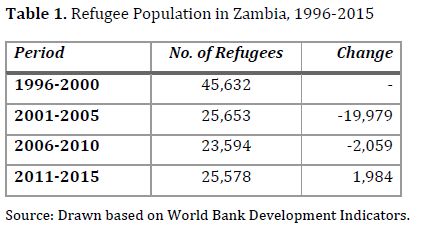

In its five decades of existence as an independent country, Zambia is one of the very few Southern African countries that has maintained peace internally among its more than seventy-two tribes and externally with its eight neighbouring countries, most of which are epicentres of armed conflicts. Consequently, Zambia has been home to a refugee population from neighbouring countries. Some of Zambia's neighbours that have witnessed armed conflicts are Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Mozambique. Other countries such as Rwanda, Burundi and Somalia, which are geographically in East Africa, have been among the leading contributors to the refugee population in Zambia over the last two decades or so. Migration statistics show that over the last two decades, the population of refugees in Zambia has been considerably reducing from 45,632 in the period 1996-2000 to 25,578 in the period 2011-2015. This reduction is mainly due to the return of relative peace in some of the countries such as Angola, Rwanda and the DRC. Table 1 below shows Zambia's refugee population between 1996 and 2015.

The changes in the stock of refugees over the years could be attributed to the repatriation exercises that the Zambian government and the UNHCR have conducted over the period under review, following improvements in security situations of some of the refugees' home countries as earlier observed. For instance, in 2009, the UNHCR assisted a total of 19,200 refugees to be repatriated to either their countries of origin or to a third country where they had chosen to live. Through this exercise, 17,000 Congolese (from the DRC) and 2,200 Angolans were among those repatriated to their countries of origin. In the same year, 137 refugees were helped to resettle in third countries of their choice. The UNHCR also conducted a verification exercise to establish the number of refugees from the DRC who were living in Zambian communities outside of refugee camps, specifically in Luapula Province. A total of 6,535 refugees of Congolese origin were found to live in these communities (UNHCR, 2009: 89).

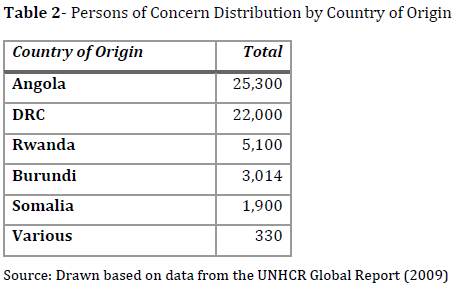

According to the UNHCR (2009), the population of persons of concern in Zambia by country of origin is as shown in Table 2 below.

Migration and the Political Economy of Identity in Zambia

Over the last couple of years, Zambia has witnessed a flaring up of hate and rejection based on identity. Although, as shown in the background section, Zambia has witnessed isolated incidents of inter-racial hatred and conflict in the period before independence, the most expressed form of hatred has been that based on one's language or tribe. However, events in the recent past seem to suggest an increase in the complexity of ethnic hatred in Zambia. Another dimension to the new form of ethnic hatred is the role of national politics in heightening ethnic consciousness in the population. The anti-Chinese rhetoric that formed the opposition leader, Michael Chilufya Sata's populist mobilisation in the 2006, 2008 and 2011 elections psyched most of the urban youths into believing that that socio-economic woes were a direct result of foreigners living in the country. As a result, from the standpoint of the authors, the constructivist-instrumentalist theoretical framework seems to explain the problem of ethnicity and violence in Zambia.

The Chinese investors, on their part, have not done much to help their own situation given the number of reports relating to abuse of Zambian workers in Chinese owned firms and construction projects. For instance, the 2005 explosion at a munitions factory serving Chambishi, which killed 46 Zambian workers (Alden, 2007: 74), reinforced the conspiracy theories including the claim that the Chinese 'bosses' had deliberately trapped the Zambian workers, a claim inflamed by the fact that not a single Chinese worker was harmed in the accident. In his paper presented to the Harvard University Committee on Human Rights Studies, Sata (2007) accused the Zambian government of failure to attract genuine investors and of favouring "rogue Chinese investors" that had no regard for the welfare of those that were unfortunate enough to work for them. He also accused China of seeking relations with Africa in order to, inter alia, perpetuate its abuses of the ethnic minorities in Tibet and Taiwan. Unsurprisingly, the ascendance to power by Michael Sata and the Patriotic Front in September 2011 was greeted by frequent protests by Zambian workers in Chinese owned firms and construction projects. One of these protests occurred at the Chinese Collum Coal Mine (CCM) in Southern Zambia, where the Chinese reacted by shooting 13 of the protesting miners (Sautman and Hairong, 2014: 1073-1092).

Although there were generally no reports of fatal incidents connected to ethnic or racial hatred until much recently, an official statement by the Evangelical Fellowship of Zambia, Council of Churches and the Zambia Episcopal Conference to commemorate the World Refugee Day on 20 June 2005 warned of rising xenophobia in Zambia:

One does not have to look far for evidence of the fact that refugees are increasingly unwelcome in Zambia. We have seen a disturbing rise in the verbal abuse, harassment, arbitrary detention, and physical violence that refugees suffer in Zambia. The church regrets the fact that people with genuine protection concerns have been forcibly returned from Zambia to countries where their lives or freedom are in jeopardy. Needless to say, this practice violates the human rights of refugees and does not reflect well on Zambia's international image (Darwin, 2009:6).

April 2016 Xenophobic Riots

On April 7, 2016 riots broke out in Zingalume, a slum area of Zambia's capital city, Lusaka, after a dead body was discovered early that morning. The people accused the police of not doing anything to protect them at night. They also argued that they were not happy with the (ritual) killings that were happening in the area (Nkonde, 2016:4). The riots, which were xenophobic in nature, targeted shops owned by foreigners over allegations that they were the ones behind the string of ritual killings that had occurred in Lusaka. The riots were, however, quenched by the police. Later, on April 18, 2016 residents of Zingalume Township ran amok and looted some shops run by Rwandans after word went around that suspected ritual murderers had been cornered in possession of human body parts (Mwenya & Mwale, 2016:1-3). By this time at least seven people were discovered murdered in George, Lilanda and Zingalume townships, with body parts such as ears, hearts and sexual organs (now widely known as 'sets') removed (Zimba, 2016:2-4). All of the victims were male. It was alleged that the killings were committed by a named Rwandan national whose shop was later looted for groceries and fridges. The rioters later moved on to another shop owned by a Rwandan in Zingalume, where they escaped with various merchandise, such as plasma television sets, generator sets and radio players, before regrouping again around other shops run by Rwandans in other townships.

The riots then spread to the neighbouring Chunga Township (Mwenya & Mwale, 2016:1-3). By the following day, April 19, 2016, the riots and looting had spread to other townships in Lusaka such as George, Garden, Chawama, Kuku, Bauleni, Mtendere, Garden House, Matero and Kanyama. During the riots, two local people, wrongly suspected of being Rwandan nationals were burnt to death and more than 60 shops and houses owned by foreign nationals were looted with rioters taking cash, food, drinks, refrigerators and other electrical appliances (Dawood, 2016). In the Garden House area, all shops belonging to Burundian and Rwandan nationals were broken into and looted, with fridges that were pulled from the shops lying in the nearby vicinity (Mukuka, 2016:4). In reaction to the riots, the Minister of Home Affairs, Davies Mwila, assured foreigners that the government was ready to integrate most foreign nationals who originally came in as refugees as soon as they got their passports from their countries of origin (Mvula, 2016:1-3). It was not clarified as to how foreigners who ran away from being killed in their own countries would go back and get passports. As a result of these riots, two foreign nationals, whose nationalities have not been confirmed, were burnt to death on 18 April, 2016. The Zambia Police Service fought running battles with residents and later removed merchandise from foreign owned shops for safekeeping.

Some residents that were interviewed called on President Edgar Lungu to speak out against the xenophobic attacks that were also affecting local businesses. One resident argued:

We want President Edgar Lungu to come out from wherever he is hiding. He is the President, his word is more powerful than what his ministers can say. Let him speak out against these evil happenings, let him condemn the attacks on the foreigners and give the country proper direction (Mukuka, 2016:4).

Later, on April 21, 2016, President Edgar Lungu assured internally displaced Rwandans and other foreigners that his administration would not abandon them but would protect them against persecution by criminals. He said this when he visited over 400 Rwandans who sought refuge at Kalemba Hall at St. Ignatius Catholic Church in Lusaka's Rhodes Park area, a low-density township (Chulu, 2016:1). A number of reasons can be advanced in trying to identify, explain and understand the root causes of the xenophobic riots of April 2016 in Lusaka. As noted above, Kersting (2009), citing Horowitz (2001), analyses hundreds of lethal ethnic riots and related forms of xenophobia and identifies four reasons for such outbursts. To recap, these are: firstly; 'ethnic' or 'national' antagonism; secondly, a 'reasonable' justification of violence; thirdly, a response to a certain event; and fourthly, aggression in a situation where the mob does not face any, or only a small, risk of punishment. These can be used to explain the "xenophobic" attacks that took place in April 2016 in Lusaka, Zambia.

Firstly, the April 2016 xenophobic riots might have been indirectly psyched by the competing political elite who have been increasingly electioneering on ethnic lines after the general election of 2001. All the major elections that have taken place in Zambia since 2001 have expressed the country's ethnic divide more than anything else. This is evidenced by the trend where the country's political parties have tended to garner more votes from regions with which their key leaders identify. In the process, two 'hostile' ethno-political blocs have emerged, the North-Western and North-Eastern regions. Results of the 2001, 2006, 2008, 2011 and 2015 elections clearly support this argument (ECZ Results Sheets, 2001, 2006, 2008, 2011 & 2015). Additionally, the periods preceding the 2015 Presidential by-election, and leading up to the 2016 general elections have witnessed several hate speeches by some politicians, some of which have resulted in bloody conflicts.

An example is the Mulobezi Constituency parliamentary by-election where two supporters of the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND), Mbangu Mbangu and Sakubita Namushi, and one supporter of the governing Patriotic Front (PF) by the name of Simanga Siboli, were allegedly shot (Mwale, 2015: 1 & 2) during a political fracas that ensued following an ethnically provocative statement by PF's Secretary General, Davis Chama. Chama stated that the Southern Province of the country would never produce a head of state in one hundred years unless their men used their polygamous nature to bear more children. Ironically, reports alleged that the gun used in the shooting belonged to Chama. After widespread condemnation, Chama said that ... he would not apologise for his remarks that Tonga should use their polygamous traits to have more children to stand a chance of producing a president in 100 years' time because it was a fact (The Post, 2015).

Such statements, and the impunity with which they are made, have arguably contributed to the rising ethnic tensions in Zambia in the recent past. His refusal to apologise and the support he received from the other leaders in his party did not show any state resolve to embrace multi-ethnicity and racial harmony in the country and could have only added to the ethnocentric psyching of the population.

With regard to national antagonism, it is positive to note that, generally, Zambians have lived in harmony with many nationals from foreign countries since independence in 1964. In fact, Zambia helped liberate a number of Southern African countries, such as Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa, by hosting freedom fighters during the liberation movements of the 1970s and 1980s. However, as shown earlier in this article, Michael Sata's nationalistpopulist campaigns based on anti-Chinese, anti-Indians and anti-Lebanese traders should surely have sown a seed of racial consciousness in the Zambian population, especially among the poor and those who live in squalor in the country's major slums in Lusaka. Most of the poor urban dwellers seem to associate their poverty with foreigners who they accuse of taking away some of their business lines. Alden (2007: 49), citing Dobler (2008) brings this into perspective when he cites the former trade minister of Zambia, Dipak Patel, who once said: "Does Zambia need Chinese investors who sell shoes, clothes, food, and chickens in our markets when the indigenous people can?" The looting of shops owned by Africans hailing from neighbouring countries during the April 2016 xenophobic violence seemed premised on this argument.

Secondly, one can argue that the April 2016 riots were caused by some Zambians who were reasonably justified in their violence. The residents of the affected townships (Zingalume, George, Kanyama and Matero) in Lusaka justified their violence based on the assumption that the police had failed to prevent the ritual killings and had not arrested any suspects following the spate of murders within a short period of time. The locals also believed that some of the ritual killers were foreigners, especially Rwandan businessmen and women, who lived in the same townships and used charms from body parts of murdered victims to enhance their businesses. These assumptions seem to have contributed to the violent riots and looting of foreign owned shops. The fact that Zambian police later apprehended and charged four Zambians for the ritual killings may, however, discount these assumptions because no foreign or Rwandan shop owner had been arrested or charged with ritual murder at the time of this publication.

Thirdly, residents in the affected townships rioted and attacked foreigners and looted their shops as a response to the ritual killings that had taken place. The feelings of helplessness with little or no protection from the police against the murderers may have fuelled the violence. In addition, it can be argued that the riots and looting may have been influenced by other factors such as the high cost of living and harsh economic situations that Zambians were facing. Zambian's economic outlook has deteriorated ever since the PF took over power from the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) in 2011. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) argued that the xenophobic attacks in Lusaka reflected how the challenges of an economic backdrop could fuel social tensions and weaken security. The EIU posited that high inflation and a subdued economic outlook would further heighten the social tension and escalate the unrest. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), in 2015, Zambia was ranked among the hungriest countries on the Global Hunger Index (GHI), with the 'most hungry' being the Central African Republic and Chad. Although the 2016 riots appeared to have been triggered by the suspected ritual killings, socio-economic factors such as high youth unemployment and the rapidly rising cost of living have increased frustration and tension among many Zambians, especially the youths. Many foreign nationals were running thriving businesses around Lusaka while the majority of the citizens were not, thereby increasing the hostility towards foreigners (EIU, 2016).

Further, according to the World Bank (2016):

Zambia's economy grew at an average annual rate of 7 percent between 2010 and 2014. However, global headwinds and domestic pressures have strained the Zambian economy. Consequently, growth in 2015 fell to an estimated 3 percent (compared to 4.9 per cent in 2014) following a six-year low in copper prices, increasing power outages, and El Nino-related poor harvests. Growth is expected to remain around 3 percent in 2016, subject to the 2016 harvest, the mining industry's reaction to softer copper prices, and stabilisation of the power situation. The benefits of gross domestic product (GDP) growth have accrued mainly to the richer segments of the population in urban areas. Zambia has a very unequal income distribution (Gini coefficient = 55.6). The falling copper prices, exports and foreign direct investment (FDI) have weakened the economy. Copper prices declined by almost a third from their peak in February 2011 to $4,595/ton in February 2016 (LME) and are forecast to remain soft until 2018 as global supply currently exceeds demand. The mine closures in 2015 led to the loss of over 7,700 jobs. Sixty percent of the population lives below the poverty line and 42 percent are considered to be in extreme poverty. Moreover, the absolute number of poor has increased from about six million in 1991 to 7.9 million in 2010, primarily due to a rapidly growing population.

The kwacha has depreciated considerably (the kwacha tends to depreciate as the copper price falls and appreciate as it rises). However, during this same period, global headwinds have combined with domestic pressures and ebbing confidence in the economy, resulting in huge shifts and market turbulence. While the strength of the US dollar, fused with worsening current account and fiscal imbalances, has propagated depreciation in most resource dependent currencies, the kwacha's decline stands out. There have been three distinct phases to the kwacha to US dollar exchange rate between January and November 2015. There was the gradual depreciation between January and mid-August, where the kwacha depreciated by 21% over 30 weeks, moving from ZMW 6.4 to ZMW 7.9 per US$. What followed next was huge volatility and a steep decline in the exchange rate. In the 10 weeks to end-October, the kwacha depreciated by 69% to ZMW 12.5 per US$. By November 11, 2015, the exchange rate reached ZMW 14.2 per US$, but by the end of that month had recovered to ZMW 10.3 per US$, an appreciation of 27% in 19 days. The net effect is that the kwacha depreciated by 61% over the 11 months to endNovember, 2015. Put differently, the kwacha lost 38% of its value (World Bank, 2015).

Furthermore, between January 2012 and September 2015, inflation remained stable at an average rate of 7.2%. Low inflation was attributed to low oil prices, a stable currency, and prudent monetary policy by the Bank of Zambia (BoZ). In 2015, inflation fell consecutively during the first and second quarters. However, since mid-2015, inflationary pressures began building up due to the depreciating kwacha. However, October inflation (year-on-year) jumped to 14.3% and November inflation to 19.5%, a shift driven by food inflation that increased to 16.2% in October and 23.4% in November, from 8.1% in August 2015. The basket of food measured includes both domestically produced foods, where price is largely dependent on the quality of the harvest, and imported foods where prices are impacted by the depreciation of the kwacha. Non-food inflation also rose to 15.5% in November from just 7.3% in September, on the back of increased transport costs as vehicles and car parts became more costly to import (World Bank, 2015).

The April 2016 riots may be similar to the 1991 situation when people could not contend with the rising economic problems any longer, resulting in food riots across the country and the death of 30 people. However, due to the fact that the economy was mainly state controlled in 1991, rioters mostly looted state owned shops. In addition, there was an attempted coup d'état. The Kaunda government arrested union leaders, among them Fredrick Chiluba. Eventually, due to mounting domestic pressure, Kaunda was forced to re-introduce multiparty politics and/democracy, which was abandoned in 1972. Thus, on 31st October 1991, elections were held and Kaunda was defeated by 80% to 20% by Frederick Chiluba of the MMD.

By the time the MMD was defeated by PF in September 2011, inflation was at 8.8% and it has now risen to 21.8% as of April 2016 (CSO, 2011; CSO, 2016). In addition, the price of the staple commodity, mealie-meal, which was at 35 kwacha in 2011 has sky rocketed to an average of 100 kwacha in most places in Lusaka. Though the 1991 riots were caused by the harsh economic environment that created food shortages, the April 2016 riots could have been similarly caused by high prices of food (i.e. mealie-meal) and other essentials, which were available but unaffordable.

Fourthly, aggression against foreigners in April 2016 may have been caused by the mobs', rioters' or looters' perception that they would face no or little risk of punishment; hence they looted and attacked foreigners with impunity. Forthwith, the police moved in but failed to quench the riots that quickly spread throughout Lusaka. Could it be that the police supported the riots and looting of foreigners, as claimed by some circles?

Furthermore, the spontaneous riots of April 2016 appeared to be a reaction to the police's failure to publicise the identities of the suspected ritual killers who were in custody for possession of human body organs and parts. Most people in the high density residential areas of Lusaka strongly believed that the ritual killers were all foreigners. Thus, foreigners, mostly from Rwanda, were targeted, especially when a rumour spread that body parts were found in a deep freezer at a shop owned by a Rwandan national in one area of Lusaka. Many of the Rwandan nationals, who have lived undisturbed in Zambia as refugees after escaping the 1994 Rwandan genocide, were once again under threat of being lynched by rioters and looters and had to seek refuge at police stations. Within two days, the riots spread quickly to several other densely populated residential areas in Lusaka. The rioters not only destroyed property belonging to foreigners worth thousands of kwacha, but they also looted their shops and houses, and burnt a police station.

To curb the situation, the government deployed police officers in the affected areas who subsequently failed to control the situation. Therefore, the government had no option but to call upon the Zambia Army to move in and stop the riots and looting which were almost engulfing the whole of Lusaka (Nkonde, 2016: 1-4). Consequently, the 400 military personnel deployed managed to quell the riots and looting and continued patrols in the high density areas of Lusaka for about two weeks thereafter. Later, the military was withdrawn and a special paramilitary police unit took over the patrols and was still doing so as of 30 May 2016.

For 22 years, some 6,000 Rwandans have lived in Zambia without being harassed. They lived freely in many townships in Lusaka like Zingalume, George, Kanyama and Matero, which are by no means up-market addresses, and set up little shops to trade and survive. The locals, however, lived in abject poverty in a harsh economic environment. They had no jobs and owned nothing compared to the Rwandans. As a result of the riots and looting, about 700 Rwandans were internally displaced in Lusaka and found themselves seeking shelter in police stations and churches. The government moved in to protect them and transported some to a refugee camp in the western part of the country where they expressed concerns about security and lack of basic sanitary conditions. The lives of the Rwandans who sort refuge in Zambia after the 1994 Rwandan genocide are once more under threat.

Conclusion

The arguments raised in this article generally show that as much as identity and xenophobic conflicts can be psyched by rent-seekers, they can also arise from declining socioeconomic situations and be cemented by a feeling that migrants are economic competitors. The deteriorating state of the Zambian economy has been linked to the poor people's increased dislike of the foreigners, especially those who are seen as conducting businesses traditionally thought to be reserved for the indigenous Zambians. This could explain why it is the immigrants from Eastern and Southern African regions who are increasingly coming under threat. An attempt has also been made to show that the country's identity consciousness is not only historical, but a result of various episodes and events that have tended to create both ethnic cleavage and hatred. The country's political leaders have been highlighted as among those who have been responsible for fuelling hate based on tribal or racial identity as a strategy for mass mobilisation. Further, the failure by the Zambian authorities to punish those who commit crimes relating ethnic hatred has been identified as a guarantee of impunity for the perpetrators of such offences.

Recommendations

Notwithstanding the penetrating nature of ethnic consciousness once it is absorbed, the Zambian authorities can nevertheless promulgate and enforce laws that criminalise the expression of hate in any form by a Zambian or foreigner living in Zambia. Further, there is clearly a need to promote the creation of new socialisation institutions that should promote a sense of 'ubuntu' (humanity) among Africans. The African Union can take a leading role in promoting ethnic harmony among Africans within and beyond their countries. New school curricula can be developed to include the teaching and learning of African languages in the same way that many Africans are currently learning other major languages such as French, English, Chinese, inter alia. Deliberate educational exchange programmes among African universities ought to be promoted in order to encourage cultural exchange among the African people. African cultural institutions on the model of the Confucius Institute, Alliance Françoise and the British Council, could be established by African countries to serve as conduits of cultural exchange and appreciation. African governments could also do well to economically empower themselves with capital and technical know-how so as to foster the growth of successful African entrepreneurs able to compete and survive in a growing global village.

References

Darwin, C. 2009. Report on the Situation of Refugees in Zambia. Cairo: Africa and Middle East Refugee Assistance (AMERA). [ Links ]

Alden, C. 2007. China in Africa: African Arguments. London and New York: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Bacova, V. 1998. The Construction of National Identity - on Primordialism and Intrumentalism, Human Affairs, 8 (1): 29-43. [ Links ]

Baldacchino, J. 2011. The eidetic of belonging: Towards a phenomenological psychology of affect and ethno-national identity. Ethnicities, 11(1): 80-106. [ Links ]

Bates, H.B. 1970. Approaches to the study of ethnicity. Cahiers d'Etudes Africaines, 10(40): 546-561. [ Links ]

Bbaala, P. and Momba, J.C. 2015. Beyond a free and fair election: The ethnic divide and the rhetoric of "One Zambia, One Nation." In: Mihyo, P.B. (Ed.). Election Processes Management and Election-Based Violence in Eastern and Southern Africa. Organisation of Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa (OSSREA). Addis Ababa: OSSREA, 143-168. [ Links ]

Boon, R. 2015. Nationalism and the Politicisation of Identity: The Implications of Burmese Nationalism for Rohinya, Undergraduate Thesis, International Studies, Leiden: Universiteit Leiden. [ Links ]

Central Statistical Office (CSO). September 2011. The Monthly. Volume 102. Lusaka: CSO.

Central Statistical Office (CSO). 2013. 2010 Census of Population and Housing, Migration and Urbanisation Analytical Report. Lusaka: CSO. [ Links ]

Central Statistical Office (CSO). April 2016. The Monthly. Volume 156. Lusaka: CSO. [ Links ]

Chulu, K. 2016. Lungu Assures Foreigners of Protection. Zambia Daily Mail. April 22, 2016, p.1.

Dawood, S. Two Burned Alive in Zambia Riots, April 20, 2016. From <www.dailymail.co.uk> (Retrived December 8, 2016).

Desai, A. 2008. Xenophobia and the place of the refugee in the rainbow nation of human rights. African Sociological Review/Revue Africaine de Sociologie, 12(2) (2008): 49-68. [ Links ]

Dobler, G. 2008. Solidarity, xenophobia and the regulation of Chinese businesses in Namibia. In: C. Alden, D. Large and R. Soares de Oliveira, S. et al (eds.) 2014. China Returns to Africa: A Rising Power and a Continent Embrace. London: Hurst Publishers. [ Links ]

Dresang, D.L. 1974. Ethnic Politics, Representative Bureaucracy and Development Administration: The Zambian Case. The American Political Science Review, 8(4): 1605-1617. [ Links ]

Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ). 2001, 2006, 2008, 2011 and 2015. Election Results Sheets. Lusaka: ECZ. From <https://www.elections.org.zm> (Retrieved 8 December, 2016). [ Links ]

Gann, L.H. 1958. The Birth of a Plural Society: The Development of Northern Rhodesia under the British South Africa Company 1814-1914. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Geertz, F. 1963. The Integrative Resolution: Primordial Sentiments and Civil Politics in the New Sates in Geertz, F. (Ed.). 1963. Old Societies and New Sates: The Quest for Modernity in Asia and Africa, New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Gluckman, M. 1960. Tribalism in Modern British Central Africa. Cahiers d'Etudes Africaines, 1:55-70. [ Links ]

International Organisation for Migration (IOM). 2014. Regional Strategy for Southern Africa, 2014-2016. Pretoria: IOM. [ Links ]

International Organisation for Migration (IOM). 2016. 2015 Global Migration Trends Fact Sheet. Berlin: IOM Global Migration Data Analysis Centre (GMDAC). [ Links ]

Joireman, S. F. 2003. Nationalism and Political Identity. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Kasoma, F.P. 1986. The Press in Zambia. Lusaka: Multimedia Publications. [ Links ]

Kersting, N. 2009. New nationalism and xenophobia in Africa: A new inclination? Africa Spectrum, 44(1): 7-18. [ Links ]

Livingstone Mail. The Races can never mix, they are divided as East is from West. 10 January 1947: p.5.

Mitchell, C. 1956. The Kalela Dance: Aspects of Social Relationships Among Africans in Northern Rhodesia, Paper No. 27. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Mukuka, J. Zambia Army Takes Over-Lusaka Compounds Policing. The Post, April 21, 2016: p.1-4.

Mulenga, C. One More Ritual Murder Suspect Nabbed. Zambia Daily Mail. April 26, 2016:2.

Mulenga, F.M. 2011. Constitution-making, the colonial state and white mine workers on the Northern Rhodesian Copperbelt, 1960-1961. Paper presented at the Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Amalgamation of North-Eastern and North-Western Rhodesia, Conference in Lusaka, August 24-25, 2011.

Mvula, S. Police Nab 11 Suspected Killers. Zambia Daily Mail. April 19, 2016: 13.

Mwale, C. Petauke, Malambo, Mulobezi vote in by-elections. Zambia Daily Mail, June 30, 2015: 1-2.

Mwenya, C. and Mwale, C. Residents Loot Shops over Ritual Murders. Zambia Daily Mail. April 19, 2016: 1-3.

Nkonde, F. Zingalume Riots Over Killings. The Post, April 8, 2016: 1- 4.

Norris, P. and Mattes, R. 2003. Does Ethnicity Determine Support for the Governing Part: A Comparative Series of National Public Attitude Surveys on Democracy, Markets and Civil Society in Africa? Afrobarometer Working Paper No. 6. Legon-Accra, Ghana.

Osaghae, E. E. and Suberu, R. T. January 2005. A History of Identities, Violence and Stability in Nigeria, CRISE Working Paper No. 6, Oxford: Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity (CRISE).

Rodney, W. 1976. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London and Dar es Salaam: Bogle-L'Ouverture and Tanzania Publishing House. [ Links ]

Sadarnis, A. 2014. Zambia: The First 50 Years. New York: I.B., Tauris and Co. Ltd. [ Links ]

Sata, M.C. 2007. Chinese investment in Africa and implications for international relations, consolidation of democracy and respect for human rights: The case of Zambia. Paper presented to the Harvard University Committee on Human Rights Studies, Events Series, Boston, Harvard University. [ Links ]

Sautman, B and Hairong Y. 2014. Bashing the Chinese: Contextualising Zambia's Collum Coal Mine shooting. Journal of Contemporary China, 23(90): 1073-1092. [ Links ]

Stein, S.A. Competing Political Science Perspectives on the Role of Religion in Conflict in Mason, S.J.A. and Sguaitamatti, D.A. 2011. Religion in Conflict Transformation, Politorbis, 52 (2): 21-26.

The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 2016. Xenophobic violence erupts after spate of murders. London: EIU. [ Links ]

The Post. I never committed a crime, I never fired a gun - PF Secretary General Chama, June 16, 2015.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). 2016. Figures at a glance. Geneva: UNHCR. Available at www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html. Retrieved on 30 September 2016. [ Links ]

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). 2009. Global Trends 2009. Geneva: UNHCR. Available at www.unhcr.org. [ Links ]

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). 2016. Statistics: the World in Numbers. Available at www.unhcr.org. Retrieved on 30 September 2016.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). 1991. Ukwimi Refugee Settlement: A Gender Case Study. Geneva: UNHCR. [ Links ]

United Sates (US) Department of State. 2014. IDIQ Task Order No. SAWMMA13F592, Field Evaluation of Local Integration of Former Refugees in Zambia, Field Visit Report. From <http://bit.ly/2hj7T4K> (Retrieved December 8, 2016).

Wilmer, F. 1997. Identity, culture, and historicity: The social construction of ethnicity in the Balkans. World Affairs, 160(1): 3-16. [ Links ]

World Bank. 2015. 6th Zambia Economic Brief: Powering the Zambian Economy. Issue 6. From <www.documents.worldbank.org.> (Retrieved 6 December 2016).

World Bank. 2016. Zambia: Overview. From <http://bit.ly/1H8bzek> (Retrieved 30 September 2016).

Yang, P.Q. 2000. Ethnic Studies: Issues and Approaches. New York: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Zimba, J. President Donates to Murder Victims Families. Zambia Daily Mail. April 25, 2016, p.4.