Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.2 no.2 Cape Town Mai./Ago. 2016

ARTICLES

Exploring youth migration and the food security nexus: Zimbabwean youths in Cape Town, South Africa

Sean T. SitholeI; Mulugeta F. DinbaboII

IPhD Candidate, Faculty of Arts, University of the Western Cape, South Africa, email: seansithole88@gmail.com

IIInstitute for Social Development, Faculty of Economic and Management Science, University of the Western Cape, South Africa, email: mdinbabo@uwc.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In recent times, debates on the connection between migration and development surfaced as essential discourses in contemporary development issues. Consequently, this led to the birth of what is currently popularly coined as the migration-development nexus. In addition, there has been an evolution of the food security topic in various developmental discussions. Nevertheless, little attention has been given to the relationship between international migration and food security in the context of development in the global south. Moreover, missing in the literature is the conversation on migration and food security with particular attention to youths who constitute a vulnerable yet economically active group. Furthermore, there has been an ongoing engaging debate on the impact of remittances, whether remittances for household use are developmental in nature or not. This study, in contributing to the above debates, explores the link between youth migration and food security, and is based on a quantitative empirical study on Zimbabwean migrant youths in Cape Town, South Africa. The research presents comprehensive perspectives on the complexities linked to the reasons for youth migration in connection to food security, the importance of remittances on food security in the place of origin and levels of food insecurity in the place of destination. Results from this study can provide useful data for various stakeholders involved in both international migration and food security development agendas.

Keywords: Development, food security, migration, remittances and youth.

Introduction

The dawn of the 21st century heralded the migration-development nexus discourse which resurfaced as an imperative subject in the development agenda and has expanded remarkably since then. Globally, the connection between migration and development has been an important yet controversial discourse which has led to an engaging academic contestation or scholarly debate and attention in the midst of policy makers, researchers and academics, among others stakeholders. Various ideas and recommendations have been put forward in recent times on how best to approach the migration-development nexus (Sørensen et al. 2002; United Nations 2006; Castles & Wise 2008; Bakewell 2008; Skeldon 2008; Piper 2009; Wise & Covarrubias 2009; Glick Schiller 2011; Br0nden 2012; Sørensen 2012; De Haas 2012; Bastia 2013). This points to the fact that there is a vast expansion of interesting, yet greatly disparate literature on migration and development dialogue, showing its diversity and habitually ever-changing perspective.

The focus of the above publications and discussions was on the progressive impact that migration could possibly perform in developmental issues globally, and in developing countries in particular. The above literature also shows continuity and paradox through paradigm shift from macro issues which exclusively viewed migration at an international and national level in the context of economic growth, and on the other hand, micro extreme perspectives where migration through remittances is seen as a livelihoods strategy which is beneficial to the migrant as well as family members left behind in the place of origin. A number of scholars (Kapur 2005; De Haas 2005; De Haas 2007; Crush & Pendleton 2009; Crush 2012) have skeptical attitudes towards the notion that the household or individual use of remittances for basic necessities and not for productivity or investments, in turn, causes hindrance to economic growth and development. This is a naïve and ideologically bankrupt view which is lagging behind contemporary development issues. This is so because migration benefits to households and their livelihoods are an important aspect of sustainable livelihoods, especially the availability of income and remittances to buy food and other basic commodities. As noted by De Haan (1999: 31), remittances are not only used towards what many development professionals regard as productive investments, they are also a vital aspect of households' strategic planning for survival.

In addition, another key aspect of this argument is the disengagement between migration and food security which is noted by Crush (2012), who argues that the major drawback of the discourse on migration-development nexus over the years has been the lack of methodological dialogues and limited attention on the linkages between human mobility and food security, especially in the framework of south-south migration. Crush (2012) makes interesting points by arguing convincingly that food insecurity is shockingly not considered as one of the main determinants of human mobility, the debate overlooks the fact that migrants cross borders in search of areas with better accessibility and availability of food sources, as well as migrating in order to meet the basic needs of people back in the place of origin. Both migration and food security aspects are fundamental in the development agenda; consequently, in recent times, there has been a genesis of literature combining migration and food security. Nevertheless, the key argument of this paper is that missing from the existing and emerging academic debates on the marriage between migration and food security are narratives on the phenomenon of youth mobility in search of income for food security. Youths belong to a vulnerable group which faces challenges including high unemployment, social segregation, stigmatization, and low incomes and salaries, just to mention a few, which in turn lead to the phenomenon of youth migration. Hence, youths should be involved in the migration-food security nexus debate.

It is equally important to note that recently the international community has experienced a shocking rate of youth migration and food insecurity on one hand and a vast number of remittances sent to the places of origin on the other. In 2010, 27 million migrants globally in the 15-24 age category made up 12.4% of the 214 million international migrants, and when migrants in the 25-34 age category are included in the same year, migrant youths represented one-third of international migrants (UNDESA 2011: 12-13). In regards to food security, from 2011 to 2013, 842 million, or 1 in 8, people globally were suffering from continuous hunger and food shortages, indicating that the Millennium Development Goal of eliminating extreme poverty and hunger by 2015 continued to be illusive (FAO et al. 2013: 4). Furthermore, in 2013, the overall remittances totaled an astonishing $542 billion with $404 billion sent to developing countries and amounts expected to rise in the coming years (World Bank 2014: 2). In the African context, remittances have contributed immensely to macro as well as micro level development, especially for poverty reduction and sustaining livelihoods. This study argues that a development agenda that does not consider connecting youth migration and food security would be out of date on current developmental issues.

Background and Contextualisation

The independence of Zimbabwe in 1980 brought about immense joy, euphoria and jubilation, a new economic giant in Africa was born and, for a decade spanning from 1980 to 1990, the country was flourishing economically and socially. However, events in the 1990s signalled the beginning of the collapse of a promising economy1. From the start of the 21st century, hyperinflation, political and socio-economic crisis, led to mass exodus within and across the Zimbabwean border. In addition, the economic meltdown in Zimbabwe led to an increase in 'brain drain,' the emigration of skilled Zimbabweans from the nation state, especially professionals in the health and education sectors, because of better opportunities in foreign destinations (Tevera & Crush 2003: 1). In 2009, the Zimbabwean dollar's reliability vanished through the dollarization of the economy, as it was replaced with the US dollar and other foreign currencies (Noko 2011) that the country is still using today.

However, the economy continues to shrink, Zimbabwean youth are now hopeless because many university graduates have been turned into street vendors (Masekesa & Chibaya, 2014), Zimbabwe's unemployment levels are estimated to be 80%, with 68% of this percentage being vulnerable youths (Mukuhlani 2014: 138). Over the years, remittances from abroad have played a vital role for many in Zimbabwe. A 2014 estimation indicated that $1.8 billion was sent to Zimbabwe by Zimbabweans in the diaspora (The Africa Report 2014). As such, in the context of the crisis in Zimbabwe, remittances have saved the country from total collapse.

Prior to independence, Zimbabwe was mainly a migrant-receiving nation and then became a migrant-sending nation after independence because of the economic crisis (Tevera & Zinyama 2002; Bloch 2006; Crush & Tevera 2010). Zimbabwe's case has been viewed by Crush and Tevera (2010) as 'crisis-driven' migration, the socio-economic and political crisis has turned the once cherished breadbasket of Africa into a basket case2. The Zimbabwean case is a tragedy; the economy, health and education sectors, have been crippled, food insecurity and poverty are still major challenges, and millions of Zimbabweans, youth included, have migrated to other countries, especially to South Africa, for greener pastures. This exile includes food-insecure Zimbabweans from all walks of life who have been pushed out by the disastrous situation in the country.

Methodology

The study was conducted at three locations in Cape Town, namely, Bellville, Rondebosch and Observatory. Cape Town is a city located in the Western Province of South Africa and is second to Johannesburg as the most heavily populated metropolitan in the country (Western Cape Government 2013). Cape Town is also the tenth most populous city in the African continent (Morris 2014). It is also amongst the prominent multicultural cities in the globe which makes it very attractive to migrants (Expat Cape Town 2014). Bellville, Rondebosch and Observatory were selected because they are residence to a large number of Zimbabwean youth, migrant students and workers. These areas also have a variety of food sources in an urban set up and represent two different suburbs, the Northern and Southern suburbs. This research adopted a quantitative method approach; 60 Zimbabwean youths were interviewed using a structured questionnaire. Respondents who participated in the quantitative structured questionnaires were selected using nonprobability sampling, to be specific, snowballing sampling was used. The research was systematically carried out, and managed to reach its objectives. Nevertheless, the researchers were also mindful of some challenges in locating the target group under study, as migrants were reluctant to disclose their identity due to fear of discrimination, victimisation, xenophobia or prosecution because of lack of proper immigration documentation. Fortunately, social networks used to locate respondents proved to be very helpful.

Literature Review

The literature on the link between migration and food security in the context of internal migration has paid much attention to rural communities; however, with food security recently being recognised as an urban challenge, the focus has shifted to rural-urban migration. This is shown by several publications (Frayne 2007; Crush et al. 2007; Drimie 2008; Kassie et al. 2008; Frayne 2010; Tawodzera 2013; Pendleton et al. 2014; Dinbabo & Nyasulu 2015). The studies revealed that the social networks among rural and urban families are fundamental to survival strategies of the poor people in cities and that, to a lesser degree, urban agriculture contributes to sustainable livelihoods. Urban dwellers that face food shortages are those with few or no social links with rural communities. On the contrary, those with strong rural-urban links have the privilege of getting food from rural communities that counterbalance exposure to food insecurity. The mutual benefit is also seen through the fact that remittances and food transfers are not one-directional, there is a rural-urban as well as the urban-rural transfer of goods, commodities and money. The existence of reciprocal connections between rural and urban areas is vital to the sustainable living conditions of distraught urban dwellers.

Several empirical studies in India were conducted linking human mobility and nutrition issues, with a particular focus on malnutrition, food consumption and dietary matters (Choudhary & Parthasarathy 2009; Bowen et al. 2011; Tripathi & Srivastava 2011). Zezza et al. (2011) examined the connection between migration and nutrition issues in third-world countries using migration at a local, regional and international levels, which resulted in various outcomes. Of great interest are the findings from the above research that indicated that child growth or improved dietary intake is linked to human mobility, especially in poverty struck and vulnerable communities, signalling the importance of remittances used to access nutritious and sufficient food.

The most thought-provoking response to migration and food security and an essential publication in the migration-food security debate is Crush's (2012) examination of urbanism, internal and international migration in relation to food security in the African context. The article argues that food shortages and insecurity can surely be main causes for migration and a search for better income-earning prospects. Crush (2012) also found that the main cause of urban food insecurity is not scarcities but deficiency in food accessibility, that is to say, lack of a consistent and dependable source of income for food consumption. The paper also compared migrant and non-migrant families. The results indicated that both categories face food insecurity challenges, however, in some cases migrant households proved to be more food insecure, with both rural-urban and international migration rising rapidly as well as migrants or combinations of migrants and locals occupying the most impoverished locations in urban areas.

Various scholars have endorsed migration as a strategic decision used by many households and vulnerable communities for poverty reduction and improved livelihoods (McDowell & De Haan 1997; Scoones 1998; De Haan 1999; Skeldon 2002; Kothari 2002; Ellis 2003; Dinbabo & Nyasulu, 2015). On the other hand, remittances have been viewed as having positive developmental impact as well as being used as a source of income to reduce poverty and acquire basic needs especially during crisis years (Maimbo & Ratha 2005; Adams & Page 2005; Adams 2011). Hence, remittances can be a form of social protection, enabling migrant families to have better ways to earn a living than non-migrant families (Kapur 2003).

Various studies in Southern Africa indicated that in recent times remittances have been vital as a basis of income for many households and economies (Pendleton et al. 2006; Maphosa 2007; Bracking & Sachikonye 2010; Crush et al. 2010). In the context of Zimbabwe, research (Maphosa 2007; Tevera & Chikanda 2009; Bracking & Sachikonye 2010) showed that money and goods transferred by migrants are vital to the families, individuals and economy of Zimbabwe. Their assessment also specified that in relation to the socio-economic and political watershed in the country, the main use of remittances is for basic needs like food, education, home construction and health services, among other things, and that the transfer of financial resources and other commodities by migrants has served many people from the effects of poverty and shortages of goods.

In connection with the above, this study argues that the New Economics of Labour Migration (NELM) put into perspective the link between youth migration and food security of Zimbabwean youths. The New Economics of Labour Migration signifies a major progression in the population movement discourse. With the growing attention on people-centred development in the last quarter of the 20th century, the New Economics of Labour Migration materialised with a critical view and expansion of the neoclassical theories which were viewed as passive in dealing with population movement and developmental issues (Massey et al. 1993). The hypothesis of this theory is that households or families strategically migrate to capitalise on income earnings as well as to reduce vulnerability to various threats. Hence, remittances offer a social protection, and the risk protection clarifies why human mobility can occur in situations where there are no differences in wages in the places of origin and destination (De Haas 2010).

The main perception of the New Economics of Labour Migration is that when people decide to migrate, the choices are not reached by individuals; rather they are made at a broader level through collective elements such as strategic family or household decisions, in order to increase financial security and reduce vulnerability and challenges related to market let-downs or unexpected risks (Stark & Levhari 1982; Stark & Bloom 1985; Taylor 1999: 74). Remittances are seen as central to better livelihoods by providing financial security (Stark 1980). As noted by Taylor et al. (1996), previous work by neoclassical theorists tended to be too pessimistic and fails to address the importance of remittances in supporting or sustaining families and societies. In other words, the importance of remittances is absent in the pessimist theories on migration. Conversely, at the heart of the New Economics of Labour Migration is the fundamental role that remittances play in sustaining livelihoods of many households which, in turn, becomes the main reason for migration decisions.

The above literature did not take into account any investigation on vulnerable youths, in connection with migration and food security, with the main emphasis being on better livelihoods. Furthermore, there is over-emphasis on internal migration and food security or livelihoods; most of the literature is silent about migration and food security or livelihoods across borders. Taking into account the above-mentioned research gaps on the connection between migration and food security, this research presents an analytical framework and exploration of the link between youth migration and food security.

Empirical Findings, Data and Analysis

a)Youth Background and Demographic Information

The survey made a background check to confirm the nationality of the respondents; all 60 interviewed were Zimbabwean nationals. Out of the 60 respondents, 60% were males and 40% were females. The age breakdown in the survey included 36.7% aged between 25 and 29; 31.7% between 30 and 34; 30% between 20 and 24; and 1.7% between 15 and 19. In this study, the majority, 71.7%, were single; 21.7% were married; 5% were divorced; and 1.7% did not specify marital status. The majority of the individuals, 71.67%, were breadwinners; 18.33% specified that their relatives such as brothers and sisters were breadwinners; and 10% stated that their husbands were breadwinners. The survey also illustrated that 38.3% had no dependents; 18.3% had three dependents; 18.3% had two dependents; 11.7% had one dependent; 6.7% had four dependents; and 6.7% had five dependents. The heritage of an educated and literate Zimbabwean population was evident in the survey, with 60% having completed university level education; 30% having completed secondary education; 6.7% vocational; and 3.3% other categories.

b)Youth Employment Status

In this survey, the majority, 76.7%, indicated that they were unemployed prior to coming to South Africa, while only 23.3% were employed before coming to South Africa. In recent times unemployment in Zimbabwe has become a massive national crisis, as stated by Rusvingo (2015: 2), with the unemployment rate estimated to be 85%. This is in line with the claim that since 2000 the crisis and high unemployment in Zimbabwe led to the emergence of informal dealings popularly known as 'kukiya-kiya' (Jones 2010)3. However, the current situation in South Africa was remarkably better, 83.3% of the respondents were currently employed and only 16.7% were out of employment. Among the 50 employed respondents, 88% were employees and 12% were self-employed. In addition, out of these same 50 respondents, 74% were employed part-time and 26% were employed full-time. Evident in this research is that Zimbabwe's economic meltdown has caused high unemployment in general and youth unemployment in particular, with South Africa providing better employment opportunities.

c) Reasons for Migrating to South Africa

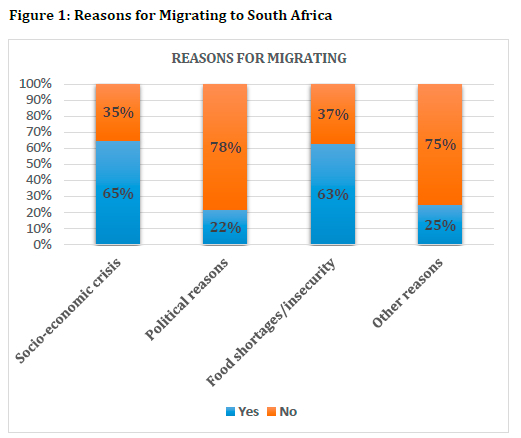

In the context of this study, the respondents were allowed to give multiple answers in relation to the drivers of migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa. 65% confirmed that socio-economic crisis influenced their decision to migrate while 35% differed. Only 22% indicated that political crisis influenced their decision to migrate while 78% opposed this opinion. 63% indicated that food shortages influenced their decision to migrate whereas 37% differed. 25% had other reasons to migrate such as coming to school (Figure 1). To put this into perspective, migration is generally viewed as a response to poverty, vulnerability to various risks and poor access to basic needs, hence people move in search of greener pastures (Skeldon 2002). Within Sub-Saharan Africa, cross-border migration is mainly a result of economic factors (Dinbabo & Carciotto 2015).

In the case of Zimbabwe, poverty is very much linked to the determinants of migration where people run away from poverty to other countries seeking better opportunities and improved livelihoods (Dzingirai, et al. 2014). Unsurprisingly, the findings of this research confirmed that the crippled and disjointed Zimbabwean economy, as well as the chaotic social and political circumstances, have overwhelmed many Zimbabweans and pushed many youth out of the country in search of improved access to food and better opportunities elsewhere. The high rate at which Zimbabweans have migrated from Zimbabwe because of the deteriorating economy has been termed "survival migration" (Crush et al. 2012: 5). Additionally, since 2000, political ferocity and economic crisis in Zimbabwe has led to outwards migration at a high or unusual level (Hammar et al. 2010: 263).

d)Family or Household Influence on Migration Decision

The family or household influence on migration decisions was evident in most of the interview responses as 70% of the respondents indicated that their household/family members influenced their decision to migrate, whereas only 30% differed. General responses here were that family/household members advised that in South Africa there were "greener pastures," "better opportunities," "jobs" and that migration would help the upkeep of the family/household members. In addition, 63% of the respondents indicated that they migrated to South Africa in order to meet the food needs of family/household members back in the country of origin, while 37% differed. This is linked to the New Economics of Labour Migration (NELM) which states that migration is a strategic choice made at a household or family level, which is generally better than at an individual level and is primarily done in order to improve income and reduce or share the responsibility of possible risks (De Haas 2010: 242-243). This is also in line with the livelihood approaches to migration, as argued by Ellis (2003) that considers migration as vital to improving livelihoods of many communities.

In addition, there was a statistically significant (p<0.001) link between (1) the influence of food shortages/food insecurity and (2) the influence of family/household members on the migration decision. Furthermore, there was also a statistically significant (p<0.002) association between (1) the influence of food shortages/food insecurity on migration decision and (2) the migration decision in order to meet the food needs of the family/household members. Without a doubt, it is clear in this study that family/household members played a huge part in the migration decision in order to reduce the risk or vulnerability to food insecurity of themselves and the migrant family/household member.

e)Youth Migration, Remittances, and Food Security

The findings in this research reveal that most Zimbabweans remit to their households, family or friends in Zimbabwe, with the majority (75%) of the respondents noting that they send money to Zimbabwe while only 25% do not send money. One of the main notions of the New Economics of Labour Migration (NELM) is that human mobility and remittances sent back to the place of origin provide financial resources which help in reducing any potential risks (Taylor 1999). To put it in another way, central to the New Economics of Labour Migration (NELM) is that remittances sent back to the place of origin play a crucial role in poverty reduction and improving the livelihoods of many households.

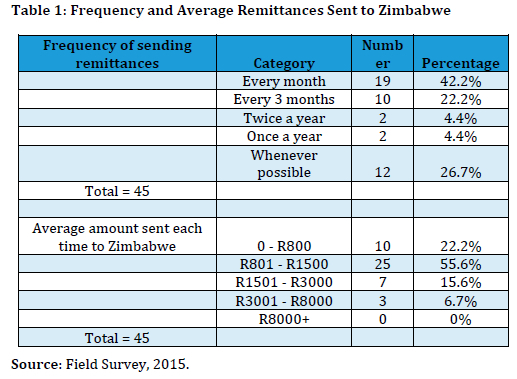

The frequency of remitting money to Zimbabwe was as follows: 42.2% every month; 26.7% whenever possible; 22.2% every three months; 4.4% once a year; and 4.4% twice a year. Average money remitted each time to Zimbabwe was: 55.6% between R801 and R1500; 22.2% between R0 and R800; 15.6% between R1501 and R3000; and 6.7% between R3000 and R8000 (Table 1). Unsurprisingly considering the backdrop of the decaying and crumbling Zimbabwean economy where opportunities are scarce, remittances behaviour revealed in this study indicates that resources are remitted back to the place of origin on a regular basis. In the context of Zimbabwe, a study by Dzingirai et al. (2015) indicated that households with migrants have an improved standard of living or healthier livelihood than those without. This is due to remittances which play a crucial part in reducing poverty by providing a source of income to buy basic needs.

In line with this, as part of the study, respondents were asked whether they send money to be used for food consumption. A huge majority 82.2% said yes while 17.8% said no. In addition, they were asked whether they believe that the money they send is used for food consumption. 91.1% of the respondents said yes while 8.9% said no. Money remittances are important, however, this survey also asked respondents whether they also send any food items/groceries back to their place of origin: 10% of the respondents said they do send groceries while 90% said they do not. In line with this, migration can make an important contribution to the livelihoods of family or household members left behind in the place of origin through remittances which could increase the chances of consuming a variety of foods contributing to a balanced diet (Karamba et al. 2011; Zezza et al. 2011).

Ellis (2003) argues that if money remitted to the place of origin is used for food consumption it is logically mainly because of food shortages and, as such, plays a crucial role in establishing food security, especially in uncertain circumstances. In connection with this, there was a statistically significant (p<0.000) relationship between (1) the sending of remittances and (2) the sending of the remittances for it to be used for food consumption, as well as (1) the connection between sending remittances and (2) believing that the remittances are used for food consumption (p<0.000). Moreover, there was also a statistically significant (p<0.000) linkage between (1) the sending of remittances for them to be used for food consumption and (2) the belief that the remittances are used for food consumption. Furthermore, there is a statistically significant (p<0.049) relationship between (1) migration in order to meet the food needs of household/family members and (1) the sending of food back to the country of origin. Evidently, the data shows that one of the main reasons for migrating is to get income to send back to the place of origin. The remittances are sent to be primarily used for food consumption and the migrants who send the remittances do believe that the money is essentially used to buy food.

f) Youth Migrants and Food Security

This section provides information and analysis on the food insecurity level of Zimbabwean youth migrants in Cape Town. The measurement of food insecurity was done by means of the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), Household Food Insecurity Access Prevalence Indicator (HFIAP), Household Dietary Diversity Scale (HDDS), Household Food Insecurity Access-related Conditions, Household Food Insecurity Access-related Domains and the Months of Adequate Household Provisioning Indicator (MAHFP).

The average HFIAS score for Zimbabwean youth migrants in Cape Town was 0.13; the mean score of the HFAIS was 3.66; the median 2; and the mode 0. The HFIAP scores had noteworthy variances: 36.7% food secure; 25% mildly food insecure; 26.7% moderately food insecure; and 11.7% severely food insecure. This shows that 63.3% of the respondents were food insecure, whereas only 36.7% were food secure. The HFIAS and the HFIAP show low general levels of severe food insecurity amongst Zimbabwean youth in Cape Town.

In measuring the particular food insecurity conditions through the conduct and opinions of the participants, the Household Food Insecurity Access-related Conditions showed that 36.7% were worried that they would not get enough food while 63.3% were not worried. The frequency was 20% for those who said rarely (once or twice in the past four weeks) and 16.3% said sometimes (three to ten times in the past four weeks). In terms of severe food insecurity conditions, only 6.7% indicated that there was no food to consume because of limited resources, while 93.3% differed. Additionally, 8.3% indicated that they went to bed hungry because of insufficient food for consumption. Moreover, a minority 1.7% point out that they went an entire 24 hours without consuming any food due to food scarcity.

Another important measure of food insecurity is the Household Food Insecurity Access-related Domains which point to the fact that 47.2% had an insufficient quality of food and 52.8% had the desired adequate quality of food. In regards to the quantity of food, 30% indicated that they had food consumption deficient, whereas the majority, 70%, had sufficient food intake. This means, basically, that in terms of food insecurity conditions over half of the respondents were not extremely worried about their situations, especially when it came to the quality or quantity of food. On the other hand, the food access related domains were insightful and showed that the majority of the respondents had high or adequate food consumption.

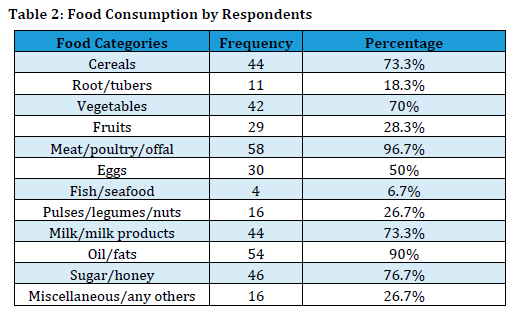

In the context of this research, the levels of food insecurity were also measured using the HDDS which deals with the quality of the diet consumed by respondents. The mean score of the HDDS was 6.56 of the potential maximum of 12 which specify that on average at least 6 different types of food categories were consumed by the respondents. On the other hand, the median and mode scores were 6 and 5 respectively, signifying that the respondents consumed at least or almost half of the food in the 12 food groups. The most consumed categories were meat (96.7%), oil/fats (90%), sugar/honey (76.7%), cereals (73.3%), milk (73.3%) and vegetables (70%). On the other hand the least consumed foods groups were fish/seafood (6.7%), root/tubers (18.3%) and pulses/legumes/nuts (26.7%), as presented in Table 2. The figures show that on average the respondents were consuming half of the 12 food categories, as well as high amounts of of meat, oil or fats, sugar or honey, cereals, milk and vegetables. This means, basically, that the Zimbabwean youth migrants in Cape Town were consuming high quality or generally sufficient nutritious diets.

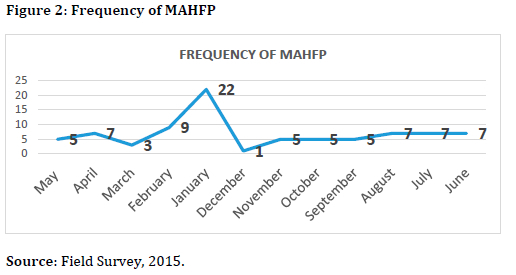

Furthermore, the MAHFP which measures whether the respondents managed to get a consistent supply of food for a period of 12 months was used to measure food insecurity. The results pointed out that 53.3% of the respondents experienced months when they did not have enough food to eat compared to 46.7% who had enough food to consume. The mean score for the MAHFP of the respondents was 1.38, the median was 1 and the mode was 0. This shows that of the months of adequate food provisioning the respondents had at least one month during which they faced food shortages. In the context of the 12 months during which the months of adequate provisioning are measured (June 2014 - May 2015), January, as shown in Figure 2, was the month during which most of the respondents faced problems because of the lack of resources.

This can possibly be attributed to the festive season spending resulting in what is commonly known as 'January disease.' In other words, this situation is seasonal; many respondents noted that they spend more money during Christmas and New Year holidays through traveling, buying food and sending remittances, among other expenditures. As a result, when they come back to the place of destination in January they usually face financial constraints, which in turn leads to low expenditure on food thereby causing food shortages.

Exploring Various Factors and their Impact on Food Insecurity

According to the empirical findings in this research, food insecurity levels among Zimbabwean youth in Cape Town seem to be very prevalent, 63.3% of the Zimbabwean youth migrants were food insecure while only 36.7% were food secure. Hence, it is important to understand the various factors or determinants of food insecurity.

To begin with, in terms of income, the empirical findings of this research indicated that all those who earned R1500 or less were food insecure while 77.3% of the food secure participants earned an average of R3000 or more. Using Pearson chi-square cross tabulation, the research findings proved that the correlation between income and food security levels was statistically significant (p<0.039), representing the positive influence of income on access to food. Secondly, in regards to gender, the findings indicated that 50% of the food secure respondents were males while the other 50% were females, showing that there is no positive link between gender and food insecurity. This was further statistically justified by a having no significance (p=0.229). This is so because access to food by both female and male migrant youths was mainly dependent upon the opportunity to get a better income to buy food, such as better paying job; this is not particularly affected by gender based factors.

Thirdly, the assumption is that those who are more educated are likely to earn more and get better jobs than the less educated. Since the likelihood to earn more is related to having better access to food, those who earn more income are expected to have the financial resources to have improved access to food. However, the findings of this study show that even though some of the Zimbabwean youth migrants were highly educated, had good jobs and decent salaries which resulted in better access to food, most of them were not guaranteed to have good and high paying jobs which would, in turn, give them financial power to have a healthier access to food. Correspondingly, a Pearson Chi-square test on the association between education and food insecurity was not statistically significant (p = 0.093) indicating that the two variables were independent of each other. In addition, among those who completed university education, 66.7% were food insecure. This is so because even those who were well educated were desperate to the extent of being employed as waiters or bartenders because the local economy is harsh on foreigners.

Lastly, this research found out that 45% of the respondents faced food shortages due to price increases while 55% did not face any challenges. The common shortages of food were "meat and cooking oil." The findings of this study also revealed that there is a relationship between high food prices and food insecurity, using Pearson Chi-square measure the result illustrated that there is a statistically significant (p = 0.000) association between the two variables. This study reinforces the assumption that price increases can lead to food insecurity of many vulnerable communities, and that high or increased food prices can lead to a decrease in the consumption of nutritious and varied food items.

Conclusion

In exploring the relationship between Zimbabwean youth migration and food security in Cape Town, the key empirical data from this research discovered that there is a positive link between youth migration and food security. The basis of this hypothesis is summarised below:

The findings confirmed that the main reasons for migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa were socio-economic crisis and, to some extent, political reasons. Most notably, in assessing the role that food insecurity or food shortages play in migration decision, the results indicated without a doubt that food insecurity/shortages proved to be one of the main reasons for migration.

In addition, family/household influence in the migration decision proved to be very common, that is to say, most households or family members took part in the migration decision of the youth migrants. Interestingly, in relation to this point, a large number of the participants revealed that they left Zimbabwe in order to help the family or household members back home with their food needs. Through the exploration of the connection between remittances and use of remittances for food consumption, the findings demonstrated that the majority of Zimbabwean youth migrants send remittances to Zimbabwe in the form of money, mainly to be used for food consumption, and were certain that the remittances they send are used to access food. It is notable that a large majority of the respondents were not sending any food groceries to Zimbabwe, as they preferred to send money.

The assessment of food insecurity levels of Zimbabwean youth in Cape Town indicated that the average HFIAS score was 0.13, mean 3.66, median 2 and mode 0, then the HFIAP indicated that 63.3% of the participants were food insecure, and only 36.7% were food secure. The research also revealed that there is a major improvement in food security for the youth migrants in South Africa compared to Zimbabwe. The major factor for the improvement of food security or better food access for Zimbabwe youth migrants, was earning income. Most of the interviewed migrants managed to get some form of employment and income, which meant they had the financial resources to buy food. With regards to dietary issues, the research revealed that the mean score for the HDDS was 6.56 out of 12, and the mode was 5, which signified that the respondents consumed about half of the 12 food categories used in this study. In line with the MAHFP, which measured the months during which the participants had food shortages or problems with food access, the findings showed that 53.3% had months during which they did not have adequate food for consumption, and the other 46.7% had no challenges or insufficient food during any of the months.

Recommendations

This paper establishes various challenges and shortcomings in giving a comprehensive account of the relationship between youth migration and food security. There is a need for collaboration, partnership, and action towards finding solutions, especially in the context of south-south migration. Four focal points are recommended in the context of youth migration-food security nexus in the global south:

• Firstly, there is a need to promote job creation or better employment opportunities for youth migrants since the outcomes of this research indicated that access to food is a challenge for migrants in general, and migrant youth in particular, due to the limited resources or lack of dependable income. Many youth migrants are students or employed as security guards, waiters and bartenders among other low-paying jobs, yet many Zimbabwean youths are well educated enough to get high-paying jobs. Promotion of employment opportunities or job creation for youth migrants by policy makers and local government departments through recruitment based on experience and qualifications would contribute to the host economy. Such employment opportunities would provide a dependable source of income which would be used for food consumption and remittances, which would also benefit those left behind in the place of origin.

• Secondly, this study revealed that some of the migrant youths consumed less nutritious foods due to a lack of knowledge, shown by an over-reliance on fast-food outlets and supermarkets, which resulted in over consumption of meat. This shows poor food utilisation. Hence, there is a need to address the challenge of unbalanced diet and consumption of limited nutritious foods. The governmental departments, non-governmental organisations like Scalabrini Centre, UNHCR, Refugee Centre, IOM and FAO, must also introduce food programmes, within their various programmes for migrants that educate and train migrants on the best practice in food utilisation, particularly on consumption of healthy plants-based diets.

• Thirdly, in recent times, migration and food insecurity concerns have been affecting many communities, yet they are still treated as two separate concerns. Combining migration and food insecurity issues at local, regional and international levels is needed and policy making needs to be addressed. In the context of South Africa, migrants have been subjected to draconian immigration policies, xenophobia and various forms of segregation, while their food insecurity concerns are invisible or unattended. The integration of migration and food insecurity issues can be addressed through local and national departments, as well as on an international level through cooperation between the general populace, governments and non-governmental organisations such as UNHCR, IOM and FAO that deal with migration and food insecurity issues. In addition, a rights-based approach to migration and food insecurity issues should be included in the post-2015 Millennium Development Goals, especially with regards to migrant youths' rights to food.

• Finally, this research showed that several studies have emerged that try to address migration and food insecurity matters, especially in the context of rural and urban connections. However, there are still many research gaps in the sense that little attention has been paid to migration and food security beyond borders or at the international level. Therefore, there is a need for more research on migration and food insecurity issues. Additionally, there is the need to contextualise youth in the research, discussions and debates on migration and food security. Information on the complex opportunities and threats that are part of the migration-security nexus, in general, and youth migration-food security nexus, in particular, is crucial as a framework for policy makers and various organisations in their policies or approaches.

References

Adams, R.H. 2011. Evaluating the economic impact of international remittances on developing countries using household surveys: A literature review. Journal of Development Studies, 47(6): 809-828. [ Links ]

Adams, R.H. and Page, J. 2005. Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries? World Development, 33(10): 1645-1669. [ Links ]

Bakewell, O. 2008. Keeping them in their place: The ambivalent relationship between development and migration in Africa. Third World Quarterly, 29(7): 1341-1358. [ Links ]

Bastia, T. 2013. The migration-development nexus: Current challenges and future research agenda. Geography Compass, 7(7): 464-477. [ Links ]

Bloch, A. 2006. Emigration from Zimbabwe: Migrant perspectives. Social Policy & Administration, 40(1): 67-87. [ Links ]

Bowen, L., Ebrahim, S., De Stavola, B., Ness, A., Kinra, S., Bharathi, A.V., Bharathi, A., Prabhakaran, D. and Reddy, K.S. 2011. Dietary intake and rural-urban migration in India: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One, 6(6): e14822. [ Links ]

Bracking, S. and Sachikonye, L. 2010. Migrant remittances and household wellbeing in urban Zimbabwe. International Migration, 48(5): 203-227. [ Links ]

Br0nden, B.M. 2012. Migration and development: The flavor of the 2000s. International Migration, 50(3): 2-7. [ Links ]

Castles, S. and Wise, R.D. 2008. Migration and Development: Perspectives from the South. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. [ Links ]

Choudhary, N. and Parthasarathy, D. 2009. Is migration status a determinant of urban nutrition insecurity? Empirical evidence from Mumbai city, India. Journal of biosocial science, 41(5): 583-605. [ Links ]

Crush, J. 2012. Migration Development and Urban Food Security. Urban Food Security Series No. 9. Cape Town: AFSUN. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Tawodzera, G. 2012. The Third Wave: Mixed Migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa. Migration Policy Series No. 59. Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Dodson, B., Gay, J., Green, T. and Leduka, C. 2010. Migration, Remittances and Development in Lesotho. Migration Policy Series No. 52. Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Grant, M., and Frayne, B. 2007. Linking Migration, HIV/AIDS and Urban Food Security in Southern and Eastern Africa. Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Pendleton, W. 2009. Remitting for survival: Rethinking the development potential of remittances in Southern Africa. Global Development Studies, 5(3-4): 53-84. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Tevera, D.S. 2010. Zimbabwe's Exodus: Crisis, Migration, Survival. Cape Town: SAMP, IDRC. [ Links ]

De Haan, A. 1999. Livelihoods and poverty: The role of migration - A critical review of the migration literature. Journal of Development Studies, 36(2): 1-47. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2005. International migration, remittances and development: Myths and facts. Third World Quarterly, 26(8): 1269-1284. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2007. Remittances, Migration and Social Development. A Conceptual Review of the Literature. Geneva: UNRISD. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2010. Migration and development: A theoretical perspective. International Migration Review, 44(1): 227-264. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2012. The migration and development pendulum: A critical view on research and policy. International Migration, 50(3): 8-25. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, F.M. and Carciotto, S. 2015. International migration in Sub-Saharan Africa: A call for a global research agenda. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 1(2): 154-177. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M. and Nyasulu, T. 2015. Macroeconomic determinants: Analysis of 'Pull' factors of international migration in South Africa. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 1(1): 27-52. [ Links ]

Drimie, S. 2008. Migration, AIDS, and Urban Food Security in Southern and Eastern Africa: Case Studies in Namibia, South Africa, and Ethiopia. HIV, Livelihoods and Food Nutrition Findings from RENEWAL Research (2007-2008), Brief 9. Washington, D.C: International Food Policy Research Institute. [ Links ]

Dzingirai, V., Egger, E.M., Landau, L., Litchfield, J., Mutopo, P. and Nyikahadzoi, K. 2015. Migrating out of Poverty in Zimbabwe. Sussex: University of Sussex. [ Links ]

Dzingirai, V., Mutopo, P. and Landau, L. 2014. Confirmations, Coffins, and Corn: Kinship, Social Networks and Remittances from South Africa to Zimbabwe. Sussex: University of Sussex. [ Links ]

Ellis, F. 2003. A livelihoods approach to migration and poverty reduction. Norwich, UK: ODG/DEV. Paper commissioned by the Department for International Development (DFID). [ Links ]

Expat Cape Town. 2014. Why Cape Town is one of the best cities for travel and expat living. From <http://www.expatcapetown.com/why-cape-town.html> (Retrieved August 20, 2016).

FAO, IFAD and WFP. 2013. The state of food insecurity in the world 2013. The multiple dimensions of food security. Rome. From <http://bit.ly/2bWXKcV > (Retrieved August 20, 2016).

Frayne, B. 2007. Migration and the changing social economy of Windhoek, Namibia. Development Southern Africa, 24(1): 91-108. [ Links ]

Frayne, B. 2010. Pathways of food: Mobility and food transfers in Southern African cities. International Development Planning Review, 32: 83-104. [ Links ]

Glick Schiller, N. 2011. A global perspective on migration and development. In: Faist, T., Fauser, M. and Kivisto, P. (Eds.). The Migration-Development Nexus: A Transnational Perspective. Basingtoke: Palgrave and Macmillan, pp. 29-56. [ Links ]

Hammar, A., McGregor, J. and Landau, L. 2010. Introduction: Displacing Zimbabwe: Crisis and construction in Southern Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 36(2): 263-283. [ Links ]

Jones, J.L. 2010. 'Nothing is straight in Zimbabwe': The rise of the Kukiya-kiya economy 2000-2008. Journal of Southern African Studies, 36(2): 285-299. [ Links ]

Kapur, D. 2003. Remittances: The new development mantra? Paper prepared for the G-24 Technical Group Meeting,.United Nations, New York, September 15 to 16.

Kapur, D. 2005. Remittances: The new development mantra? In: Maimbo, S.M. and Ratha, D. (Eds.). Remittances: Development Impact and Future Prospects. Washington, DC: World Bank. pp. 331-361. [ Links ]

Karamba, W., Quiñones, E. and Winters, P. 2011. Migration and food consumption patterns in Ghana. Food Policy, 36(1): 41-53. [ Links ]

Kassie, G., Woldie, A., Gete, Z. and Drimie, S. 2008. The Nexus of Migration, HIV/AIDS and Food Security in Ethiopia. Washington, D.C: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). [ Links ]

Kothari, U. 2002. Migration and chronic poverty. Working Paper No. 16. Chronic Poverty Research Centre. Manchester: Institute for Development Policy and Management. [ Links ]

Maimbo, S.M., and Ratha, D. (Eds.). 200). Remittances: Development Impact and Future Prospects. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Maphosa, F. 2007. Remittances and development: The impact of migration to South Africa on rural livelihoods in southern Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa, 24(1): 123-136. [ Links ]

Masekesa, C. and Chibaya, M. 2014. Unemployment Turns Graduates into Vendors. The Standard Zimbabwe. February 9, 2014. From <http://bit.ly/2cADufP > (Retrieved July 15, 2016).

Massey, D.S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A. and Taylor, J.E. 1993. Theories of international migration: A review, and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19, 431-66. [ Links ]

McDowell, C. and De Haan, A. 1997. Migration and Sustainable Livelihoods: A Critical Review of the Literature. IDS Working Paper 65. Brighton: IDS. [ Links ]

Morris, M. 2014. Highlights from the State of the City 2014 Report. Weekend Argus. November 21, 2014. From < http://bit.ly/2crUbHc > (Retrieved July 15, 2016).

Mukuhlani, T. 2014. Youth empowerment through small business development projects in Zimbabwe: The case of Gweru Young People's Enterprise (GYPE). Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 16(5): 138-144. [ Links ]

Noko, J. 2011. Dollarization: The case of Zimbabwe. Cato Journal, 31(2). [ Links ]

Pendleton, W., Crush, J., Campbell, E., Green, T., Simelane, H., Tevera, D.S., and de Vletter, F. 2006. Migration, remittances, and development in southern Africa migration. Policy Series 44. Cape Town: IDASA. [ Links ]

Pendleton, W., Crush, J., and Nickanor, N. 2014. Migrant Windhoek: Rural-urban migration and food security in Namibia. Urban Forum, 25(2): 191-205. [ Links ]

Piper, N. 2009. The complex interconnections of the migration-development nexus: A social perspective. Population, Space and Place, 15(2): 93-101. [ Links ]

Rusvingo, S.L. 2015. The Zimbabwe soaring unemployment rate of 85%: A ticking time bomb not only for Zimbabwe but the entire SADC region. 2014. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 14(9). [ Links ]

Scoones I. 1998. Sustainable rural livelihoods. A framework for analysis. IDS Working Paper No 72. Brighton: IDS. [ Links ]

Skeldon, R. 2002. Migration and poverty. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 17(4): 67-82. [ Links ]

Skeldon, R. 2008. International migration as a tool in development policy: A passing phase? Population and Development Review, 34(1): 1-18. [ Links ]

Sørensen, N.N. 2012. Revisiting the migration-development nexus: From social networks and remittances to markets for migration control. International Migration, 50(3): 61-76. [ Links ]

Sørensen, N.N., Hear N.V. and Engberg-Pedersen, P. 2002. The migration-development nexus: evidence and policy options. International Migration, 40(5): 49-73. [ Links ]

Stark, O. 1980. On the role of urban-to-rural remittances in rural development. Journal of Development Studies, 16: 369-74. [ Links ]

Stark, O. and Bloom. D.E. 1985. The new economics of labor migration. American Economic Review, 75: 173-178. [ Links ]

Stark, O. and Levhari, D. 1982. On migration and risk in LDCs. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 31(1): 191-96. [ Links ]

Tawodzera, G. 2013 Rural-urban transfers and household food security in Harare's crisis context. Journal of Food & Nutritional Disorders, 2(5): 1-10. [ Links ]

Taylor, J.E. 1999. The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration, 37(1): 63-88. [ Links ]

Taylor, J.E., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Massey, D.S. and Pellegrino, A. 1996. International migration and community development. Population Index, 62(3): 397-418. [ Links ]

The Africa Report. 2014. Zimbabwe: Diaspora Remittances in Decline. From <http://bit.ly/2csTihy> (Retrieved July 15, 2016).

Tevera, D.S. and Chikanda, A. 2009. Migrant Remittances and House Hold survival in Zimbabwe. Migration Policy Series No. 51. Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Tevera, D.S., and Crush, J. 2003. The New Brain Drain from Zimbabwe. Migration Policy Series No. 29. Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Tevera, D.S. and Zinyama, L. 2002. Zimbabweans who Move: Perspectives on International Migration in Zimbabwe. Migration Policy Series No. 25. Cape Town: SAMP. [ Links ]

Tripathi, A. and Srivastava, S. 2011. Interstate migration and changing food preferences in India. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 50(5): 410-428. [ Links ]

UNDESA. 2011. International migration in a globalizing world: The role of youth. Technical Paper No. 2011/1. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. From <http://bit.ly/2bSpDg7> (Retrieved July 15, 2016). [ Links ]

United Nations. 2006. International Migration and Development. New York: United Nations, General Assembly. [ Links ]

Western Cape Government. 2013. Regional Development Profile: City of Cape Town. From <http://bit.ly/2c3Q7xn> (Retrieved July 15, 2016).

Wise, D.R. and Covarrubias. H.M. 2009. Understanding the relationship between migration and development: Toward a new theoretical approach. Social Analysis, 53(3): 85-105. [ Links ]

World Bank. 2014. Migration and Development Brief. Washington, D.C: Migration and Remittances Team, Development Prospects Group 22. From <http://bit.ly/2bSplWJ> (Retrieved July 14, 2016).

Zezza, A., Carletto, C., Davis, B. and Winters, P. 2011. Assessing the impact of migration on food and nutrition security. Food Policy, 36(1): 1-6. [ Links ]

1 These events included the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP), draining of the government coffers through a bonus to liberation war veterans and the Land Reform Programme, all of which had a negative impact on the economy.

2 The words 'bread basket to basket case' are mainly used in reference to Zimbabwe, which used to produce a surplus of food and other resources for its people and other countries. However, in recent times with the food shortages and socio-economic crisis, the once full basket (Zimbabwe) is now empty.

3 'Kukiya-kiya' is an informal strategy of doing any kind of business to earn a living (Jones 2010).