Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.1 no.2 Cape Town Mai./Ago. 2015

ARTICLES

Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth: Evidence from Selected West African Countries (Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal)

Muriel Animwaa Adarkwa

Candidate in MA Development Studies, Institute for Social Development, Faculty of Economic & Management Science, University of the Western Cape (UWC), South Africa

ABSTRACT

Remittances from abroad play a key role in the development of many West African countries. Remittances tend to increase the income of recipients, reduce shortage of foreign exchange and help alleviate poverty. This research examines the impact of remittances on economic growth in four selected West African countries: Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal. Using developmentalist, structuralist and pluralist views on remittances, a linear regression was run on time series data from the World Bank database for the period 2000-2010. After a critical analysis of the impact of remittances on economic growth in these four countries, it was found that inflow of remittances to Senegal and Nigeria has a positive effect on these countries' gross domestic product whereas for Cape Verde and Cameroon it had a negative effect. Cameroon benefitted the least from remittances and Nigeria benefitted the most within the period. One contribution of this study is the finding that remittance inflows need to be invested in productive sectors. Even if remittances continue to increase, without investment in productive sectors they cannot have any meaningful impact on economic growth in these countries.

Keywords: Cameroon, Cape Verde, Gross Domestic Product, Nigeria, Remittance Inflows, Remittance outflows, Senegal.

Introduction

Globally, there has been a steady rise in the number of migrants. The number of migrants increased rapidly between 2000 and 2010. According to the International Migration Report (2013), between 2000 and 2010 there were 4.6 million new migrants annually, compared with an average of 2 million per annum between 1990 and 2000 and 3.6 million per annum from 2010 to 2013. Migration has positive and negative impacts on 'home' and 'host' countries, but one generally positive benefit of migration is financial remittances.

Over the past decade, remittances to developing countries from their nationals living abroad have grown steadily, reaching an estimated US$404 billion in 2013 and out-performing official development assistance (World Bank, 2014). This figure excludes the money transferred through informal channels which cannot be captured and hence is not recorded. Migrants' remittances currently rank as the second largest source of external inflows to developing countries (World Bank, 2014). This increase in remittances to developing countries can be attributed to the increase in the number of people settling abroad; and faster, easier and cheaper modes of transferring money around the world today (Imai et al., 2012; World Bank, 2014). Previous research on the areas of outward migration has shown that countries with higher remittance inflows have higher growth rates and lower poverty indices (Fajnzylber & Lopez, 2007). This is because remittances tend to increase the income of recipients in the home country who in turn decide whether to invest or spend the money in the domestic economy. It further assists countries to reduce the problem of shortage of foreign exchange which is sometimes needed urgently by governments to fund import bills (Siddique, 2010). In smaller developing countries, significant remittance inflows account for more than a quarter of their gross domestic product (GDP) (Pop, 2011). With insights such as this, it becomes important to find out if indeed remittances have any impact on economic growth.

This paper examines the impact of remittances on economic growth in the home countries of migrants, based on four selected countries in West Africa: Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal. The study uses data from the World Bank for the period from 2000 to 2010. This period was chosen because, compared with the years before 2000 and after 2010, the number of people who emigrated from their home countries reached a peak of 4.6 million per annum during this period (International Migration Report, 2013). The next section gives a general introduction on the four selected countries. Section 3 discusses the theoretical framework used and section 4 discusses the result of the data analysis. The study then concludes and gives recommendations.

Background and Contextualization

In recent times, research on the role of remittances in development has surged due to increasing evidence of its positive impacts on the economies of developing countries. Despite the fact that remittances to sub-Saharan Africa have been growing at a far slower pace than those of countries in other regions, research has shown that they contribute equally positive benefits to sub-Saharan African countries. Remittances are driven by migration. According to Tolentino and Peixoto (2011), sub-Saharan Africa has the most unstable migration flows compared with other regions in the world, although the West African sub-region has been the least volatile within the region, recording positive growth rates recorded in migrant numbers. There are many reasons why West Africans emigrate. Among them are: economic difficulties, political instability and conflicts, and increased poverty (Nyamwange, 2013).

In 2013, inflows of remittances to sub-Saharan Africa increased by 3.5% (World Bank, 2014). The increase was not distributed evenly across the continent, however. East African countries experienced significant gains in remittance inflows while those in the West Africa sub-region experienced only a marginal increase (World Bank, 2014). Despite this, organizationally, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) ranks second in terms of the collective value of remittances in-flows by member-states falling behind the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Research has shown that, despite the West African countries receiving relatively less in remittances, the impact of remittances on the economies of those countries has been positive (UNECA, 2013). Remittances have helped the region reduce poverty - its most pressing challenge -, supplemented household incomes, provided working capital and, above all, created multiplier effects within the economy through increased spending (UNECA, 2013).

Nigeria is the recipient of the greatest volume of remittances in West Africa and sub-Saharan Africa as a whole (Maimbo & Ratha, 2005; World Bank, 2014). It receives between 30% and 60% of all the remittances to the West African sub-region and its remittances rank second as a foreign exchange earner after oil exports (Orozco, 2003; World Bank, 2014). Cape Verde and Senegal, like Nigeria, in turn rank among the top recipients of remittances in West Africa. As a small island nation, Cape Verde's economy is heavily dependent on remittances and this can be seen in their contribution to the country's GDP (Pop, 2011). According to official estimates, about one-third of the population of Cape Verde live abroad, although some scholars place the figure well above that, arguing even that the number of emigrants exceeds the total resident population of Cape Verde (Carling 2002; Pop, 2011).

Remittances to Senegal more than trebled from 2002 to 2008, rising from US$ 344 million to US$ 1288 million within that period (Cisse, 2011). This growth has seen Senegal become the fourth largest recipient of remittances in sub-Saharan Africa. Further to this success, studies show that remittances entering the country through informal channels could make the figures even higher. Remittances play a key role in the economy of Senegal, contributing between 6% and 11% to its GDP, sometimes surpassing other export products and certain sectors (Cisse, 2011). In Cameroon, international migration is known as 'bush falling' and this phenomenon is triggered by a number of factors including: falls in the price of primary goods in the 1980s and '90s, structural adjustment programmes and corruption (Atekmangoh, 2011). These factors tend to serve as a motivation for Cameroonians to travel outside their country in order to seek 'greener pastures'. In Cameroon, the total inflow of remittances has been relatively stable and despite this financial contribution to the economy over the years, the people who usually migrate are the educated and active populace and this can have negative repercussions on the economy (Atekmangoh, 2011).

Theoretical Framework

From observation, although few people would disagree on the benefits of remittances to recipients in home countries, the extent to which remittances contribute to economic growth and development is another debate altogether. Diverse theories have emerged to explain the impact of remittances on economic growth (development) of the countries of origin of migrants. Among these are the developmentalist/neo-classical view, the structuralist/dependency view and the pluralist view (De Haas, 2007). These three theories will be used to ascertain how remittances impact economic growth in Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal.

The Developmentalist/Neo-Classical View (Optimists)

This view emerged in the 1950s and 1960s with the assumption that, through capital transfer, industrialization and the adoption of western values, developing countries would be able to accelerate their developmental process (So, 1990). During this period, underdevelopment was attributed to internal factors within developing countries and the notion was that, if developing countries wanted to develop, they needed to abandon their traditions, values and culture and adopt those of the West (Coetzee, 2001).

It was during this period that the developmentalist view emerged. Some prominent scholars who hold this view include: Kindleberger (1965), Todaro (1969), Beijer, (1970) and Massey et al (1993). They argue that migration will result in the transfer of investment capital through remittances and expose traditional/primitive societies to more rational, democratic and liberal ideas that will aid in their development (De Haas, 2007; 2010). Labour migration is viewed as a core part of modernization and it is believed that the effects of migration on development can be seen through the inflow of capital (remittances) which could help increase productivity and incomes (Massey et al., 1998). From this perspective, migrants' remittances are deemed important since they bring about change in household incomes, promote investments and innovations, and thereby aid the larger economy of the migrants' country of origin in its economic take-off (Kindleberger (1965) and Beijer (1970), as cited in De Haas, 2007, p.3).

Structural and Dependency Views (Pessimists)

In contrast to the above, the dependency view argues that migration and remittances create underdevelopment in migrants' countries of origin (Oluwafemi & Ayandibu, 2014). This view emerged in the 1970s and the 1980s; some scholars associated with this theory include Rubenstein (1992) and Binford (2003). They hold that remittances make receiving countries dependent on the sending countries as well as making receivers of remittances dependent on the senders (Binford, 2003). They argue that migration drains the human capacities of communities and leads to development that is passive as well as making these communities remittance-dependent (De Haas, 2007). Rather than encouraging economic growth, remittances lead to inequalities in areas where there is a large inflow of remittances (Lipton (1980), as cited in Oluwafemi & Ayandibu, 2014, p. 314). This is because when the remittances are sent to recipients in the home countries, they tend not to use the money for any productive ventures but rather spend it on conspicuous consumption, such as cars, houses and clothing, which helps to deepen the income inequalities between households receiving remittances and those that do not receive any (De Haas, 2007; 2010; Oluwafemi & Ayandibu, 2014). This can lead to inflation and the rise of prices in basic commodities in remittance receiving countries. For scholars of this tradition, remittances have a negative impact on the economies of receiving countries; they view remittances as indicators of developing countries relying on developed countries for their development (De Haas, 2010). Remittances lead to the "development of underdevelopment" (Frank (1966), as cited in De Haas, 2007, p.9).

Pluralist View (The New Economics of Labour Migration)

This view emerged in the 1980s and 1990s in the context of American research in reaction to the neo-classical and the structuralist views (Oluwafemi & Ayandibu, 2014). This view tries to link the two theories above and argues that remittances and migration have both positive and negative impacts (De Haas, 2010). In this view, migration is seen as "a household response to income risk since migrants' remittances serve as insurance for households of origin" (Lucas & Stark (1985), as cited in De Haas, 2007, p. 12). This can be seen as explaining why people migrate despite not knowing about prospects of income in host countries. This view sees remittances as having the tendency to produce both positive and negative impacts on development depending on what recipients and home countries do with the remitted money.

According to the pluralist view, migration plays a key role in the economy by providing capital through remittances which can be used for investments in developing countries that are mostly characterized by poor credit and high market risk such as fluctuating exchange rates that deters financial institutions from giving out credit frequently (Taylor & Wyatt, 1996). It also stresses the importance of human "agency" if remittances are to contribute significantly to the economies of migrants' home countries (De Haas, 2007; 2010). Accordingly, remittances will impact economic growth positively if recipients of these remittances use them for productive purposes and negatively if recipients use them for unproductive purposes.

Techniques of Data Collection

This study is a quantitative study. Quantitative research emphasizes the testing of hypotheses and the measurements of variables by linking them to general causal explanations (Neuman, 2000). In quantitative research, the language of variables, numbers, objectivity, hypothesis and causation are emphasized. This study used data sets from the World Bank. Convenience and purposive sampling techniques were used to select the countries and corresponding data under study. The sample consisted of four countries selected from the West African sub-region (Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal). The study period 2000-2010 was selected because it saw the average number of migrants per annum increase to 4.6 million compared with an average of 2 million per annum between 1990 and 2000 and 3.6 million per annum from 2010 to 2013 (International Migration Report, 2013). The data set includes remittance inflows, remittance outflows and GDP for the years from 2000 to 2010. It also contains the percentage of GDP made up of remittances in 2010 for the four countries involved in the study. STATA (version 12) and Microsoft Excel were used to analyse the data. Descriptive statistics of the relevant variables were reviewed. Graphs were drawn to show the trend of remittance inflows and outflows for the 11-year period. Linear regression analyses were used to examine the extent to which inflows of remittances predicted changes in GDP for the four countries.

Results and Discussion

In this section, I present the results of the analysis. I will begin by presenting the trend of remittance inflows and outflows for each of the four countries (Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal), followed by an analysis of the differences between remittance inflows and outflows between these countries. Next, an analysis of a linear regression is performed to find out if there is a relationship between GDP and remittance inflow. Lastly, the share of remittances as a percentage of the 2010 GDP for these countries is shown graphically as a pie chart.

Remittances Inflows can be defined as financial resources sent into the home country of the migrant. On the other hand, remittances outflows are those financial resources leaving the host country of the migrant (World Bank).

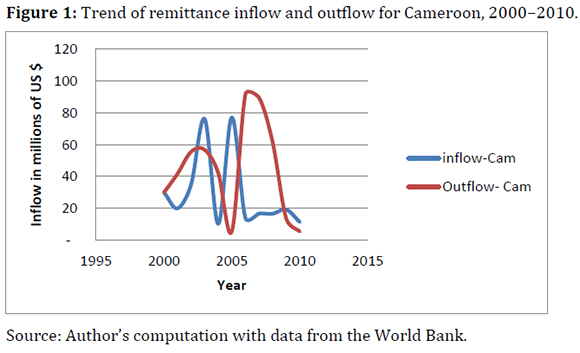

Figure 1 shows the trend of remittance inflows and outflows for Cameroon from 2000 to 2010. It can be seen that the inflow of remittances into Cameroon has been inconsistent over the 11-year period. It peaked in 2003 at US$ 76 million, rising from US$ 35 million in 2002. It then fell to US$ 10.3 million in 2004 and rose to its highest value within the 11-year period of around US$ 77 million in 2005. From there onwards, it was consistently low from 2006 to 2010, ranging from US$ 11.4 million to US$ 19.2 million. The inconsistency in remittance inflows to Cameroon is associated with a generally falling trend in the amount of remittance inflows into the country. Ngome and Mpako (2009) also found that over the years remittances have been falling in Cameroon. They identified a number of reasons for this: the high cost of money-transfer fees, the breakdown of trust in carriers of informal remittances, the belief that hard-earned money sent home by migrants is squandered by family members on luxury goods instead of being invested in productive activities and, lastly, the wide dispersal of Cameroonians in the diaspora which makes it difficult for them to remit money through informal channels.

On the other hand, remittance outflows from Cameroon has been extremely inconsistent, varying widely from one year to the next, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 2 shows the trend of remittance inflows and outflows for Cape Verde from 2000 to 2010. It can be seen that the inflows of remittances into Cape Verde fell steadily over the 11-year period, from US$ 86 million in 2000 to around US$ 13.2 million in 2010. It should be noted that the amount of remittance inflows was stable at around US$ 14 million from 2005 to 2007. An explanation for this trend could be the restrictive immigration policies being adopted by Cape Verdeans' traditional host countries in Europe, such as Portugal and the Netherlands (see Carling, 2002). However, remittance outflows have also been consistently low, ranging between less than US$ 1 million and US$ 10 million.

Figure 3 shows the trend of remittance inflows and outflows for Nigeria from 2000 to 2010. It can be seen that the inflows of remittances into Nigeria rose steadily, from US$ 1,167 million in 2001 to an all-time high of US$ 9,980 million in 2008. It then took a dip down to around US$ 958 million in 2009 due to the global financial crisis. However, it picked up in 2010, rising to US$ 1,005 million. This is consistent with the findings of Ukeje and Obiechina (2013) who argued that, despite the global financial crisis, remittance inflows to Nigeria have remained resilient. On the other hand, remittance outflows from Nigeria have been consistently low over the 11-year period, rising from less than US$ 1 million in 2000 to around US$ 21 million in 2004, and trebling to US$ 68 million in 2005; its highest in the period. Remittance outflow then fell to US$ 10 million in 2007 and since then has ranged between US$ 47 million and US$ 58 million between 2007 and 2010.

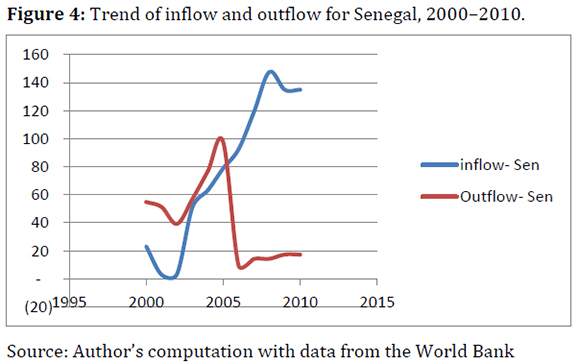

Figure 4 shows the trend of remittance inflows and outflows for Senegal from 2000 to 2010. It can be seen that the inflow of remittances into Senegal has steadily risen. It rose from around US$ 3 million in 2001 to US$ 148 million in 2008, its all-time high for the period. However, the global financial crisis in

2009 had an effect on the inflow of remittances, causing it to fall to US$ 135 million in 2009. It maintained this value in 2010 after the crisis. The resilience of remittance inflows into Senegal can be attributed to the constant inflows of money from migrants. It has been estimated that most remittance-receiving households receive between US$ 290 and US$300 per month from abroad (see Orozco et al., 2010).

On the other hand, remittance outflows from Senegal were inconsistent over the period, rising and falling in various years. Outflow rose from US$ 55 million in 2000 to US$ 98 million in 2005, its highest value for the period. It then fell to less than US$ 10 million in 2006, rose to US$ 14 million in 2007 through to 2008 and then continued its rise to US$ 17 million in 2009 and 2010 respectively.

Figure 5 compares the remittance inflows of Cameroon, Cape Verde and Senegal. It can be observed that while remittance inflows into Senegal from 2000 to 2010 rose steadily, remittance inflows into Cape Verde dropped steadily from 2003. On the other hand, remittance inflows to Cameroon for that same period were inconsistent, rising in 2003 and falling the following year, only to rise again in 2005 and fall again in 2006.

Figure 6 shows the trend of remittance inflows to Nigeria in comparison with Cameroon, Cape Verde and Senegal combined. It can be observed that whereas the level of combined remittances for the three countries (Cameroon, Cape Verde and Senegal) was steady from 2000 to 2010 that of Nigeria also rose steadily from 2000 to 2009 when it fell from US$ 9,980 million in 2008 to US$ 958 in 2009. It then picked up pace in 2010 rising to US$ 1,005 million. The sharp fall in Nigeria's inflow in 2009 can be attributed to the global financial crisis. Although the crisis did affect the combined inflows of the other three countries, its impact on their economies was minimal in comparison to that of Nigeria.

Figure 6 shows the trend of remittance inflows to Nigeria in comparison with Cameroon, Cape Verde and Senegal combined. It can be observed that whereas the level of combined remittances for the three countries (Cameroon, Cape Verde and Senegal) was steady from 2000 to 2010 that of Nigeria also rose steadily from 2000 to 2009 when it fell from US$ 9,980 million in 2008 to US$ 958 in 2009. It then picked up pace in 2010 rising to US$ 1,005 million. The sharp fall in Nigeria's inflow in 2009 can be attributed to the global financial crisis. Although the crisis did affect the combined inflows of the other three countries, its impact on their economies was minimal in comparison to that of Nigeria.

Figure 7 shows the trend of remittance outflows for Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal. It can be observed that remittance outflows for Cape Verde were consistently low for the 11-year period. On the other hand, for Senegal, remittance outflows consistently rose from 2000 to 2004, and then steadily decreased from 2004 to 2010. Remittance outflows for Cameroon and Nigeria were inconsistent for the 11-year period.

Table 1 shows the differences between remittance inflows and remittance outflows for Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal for the 11-year period (2000-2010). It can be observed that remittance outflows from Cameroon exceeded remittance inflows into the country. In most years (2001, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007 and 2008 respectively), the country recorded negative values as the difference between inflows and outflows of remittances was computed. This means that, during those years, remittance outflows from Cameroon exceeded inflows into the country. It should be noted, however, that since 2009 Cameroon has recorded positive values meaning that, since 2009-2010, the inflows of remittances have increased while outflows have fallen.

From Table 1 it can be observed that remittance inflows into Cape Verde exceed remittance outflows although this value is continuously falling. Cape Verde recorded positive values for the 11-year period, except in 2004 when it recorded a negative value (that is, in 2004, remittance outflows exceeded remittance inflows). It should be noted that although remittance inflows have always exceeded outflows, the figure has been positive but at a decreasing rate for the period. This means that the value of inflows is consistently falling although not falling to the extent that it is exceeded by outflows. This finding can be attributed to the huge disassociation between Cape Verdeans back at home and the second-generation emigrants in the host countries of migrants, which serves as a disincentive for them to send remittances (see Carling, 2002).

From Table 1 it can be observed that Nigeria always recorded positive values in the difference between remittance inflows and outflows for the 11-year period. This means that the value of remittance inflows always exceeded remittance outflows. The differences in outflows and inflows were positive and rose consistently from 2000 to 2008. However in 2009, inflows dropped due to the global financial crisis. Despite this sharp drop in 2009, the inflow of remittances was still sufficient to exceed outflow for that same period and hence Nigeria recorded a positive figure.

From Table 1 it can be observed that Senegal has recorded both negative and positive values as the difference between remittance inflows and outflows for the 11-year period. The difference between inflows and outflows from 2000 to 2005 was negative. This means that the amount of remittance outflows from Senegal was higher than remittance inflows. However, from 2006 to 2010, the differences between inflows and outflows were positive. That is, from 2006 to 2010, the amount of remittance inflows into Senegal increased whereas the remittance outflows decreased, enabling the country to gain positive returns.

From Table 1 it can be observed that, among the four countries, Cameroon benefitted the least from remittances. For the 11-year period its outflows exceeded inflows in six different years (2001, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2007, and 2008). On the other hand, Nigeria benefitted the most within the period, consistently receiving more remittance inflow than outflow, thereby enabling it to record only positive values. Cape Verde benefitted from remittance inflows during this period too, albeit at a decreasing rate. This means that, although Cape Verde recorded positive returns year after year, the amount of remittances entering the country kept on decreasing. This could be a cause of concern for the economy since it is heavily dependent on remittances (see; Carling 2002; Pop, 2011). Lastly, Senegal was able to turn around the trend of outflows exceeding inflows from 2006, with a steady rise in remittance inflows and a corresponding decrease in outflows. This enabled the country to gain positive returns from 2006 to 2010.

The descriptive statistics of the variables used in the regression analysis are presented in Table 2.

The result of regression between GDP and remittance inflow from 2000 to 2010 is presented in Table 3 (see appendix for the regression of individual countries). Remittance inflow in Senegal has a positive relationship with the country's GDP and is significant at 1%. The coefficient of determination (i.e. R-square) is 0.9105 which implies that 91% of the changes in the GDP in this model are explained by the remittance inflow. Thus, the coefficient of Senegal's inflow implies that a dollar increase in remittance inflows to the country increases the GDP by 0.05 US dollars, all other things held constant. This result is consistent with the findings of Orozco, Burgess and Massardier (2010) and UN-INSTRAW and UNDP (2010) whose research reveals that most households receive remittances on a monthly basis. Further, various researches (see Orozco et al., 2010; Randazzo & Piracha, 2014) have revealed that remittances do not necessarily change the household consumption of Senegalese who receive them but rather those who are privileged to receive them spend the money on education and investments. There has also been engagement of migrant associations in philanthropic activities in Senegal.

These wide arrays of productive purposes for which remittance inflows are used can to a large extent explain the significant relationship between remittance inflows and GDP in Senegal. This result is also consistent with the new economics of labour migration (NELM) which argues that the inflow of remittances in and of itself does not enhance or inhibit development but will be dependent on what recipients do with the money in home countries (De Haas, 2007; 2010).

The coefficient of Nigeria's inflow is positive but not significant. This means that as the inflow of remittances increases the GDP of Nigeria also increases but there is no clear link between the two. Increases in remittance inflows do not play a significant role in the rise in Nigeria's GDP over the period. This can be explained by the large differences between the values of GDP and remittance inflows. Despite that fact that remittance inflow to Nigeria is the second largest source of foreign exchange after oil exports (see Orozco & Mills, 2007), the lack of a direct relationship between remittance inflows and GDP in Nigeria can be explained by the increase in exports over the same period (see Ukeje & Obiechina, 2013). This result is also consistent with the developmentalist theory which argues that labour migration is a core part of modernization and that the effects of migration on development can be seen through the inflow of capital (remittances) which could help increase productivity and incomes (Massey et al., 1998). Thus, although this theory argues that capital inflows do indeed increase incomes, as in the case of Nigeria, it does not shows us the ways in which these incomes can be used to increase productivity (that is, perhaps despite the increase in the flow of remittances to Nigeria, it does not have any significant relationship with its GDP).

The coefficient of Cape Verde's remittance inflow is significant at 1% but has a negative relationship with the GDP. This means that as remittance inflow to Cape Verde increases there is a corresponding decrease in its GDP. One possible explanation of this is that when remittances flow into the country they are either used for unproductive purposes or for activities that cannot be captured in the GDP. This finding can be explained with the decreasing role remittances play in the Cape Verdean economy now as compared with earlier years, in the 1960s (see Ronci et al., 2008; Akesson, 2010; Watkins, 2010). Further, research has also revealed that the inflow of remittance into Cape Verde is usually used to supplement household incomes, instead of being used for productive purposes, due to the increase in the cost of living (see Akesson, 2010). These explanations are rooted in the dependency/structuralist theory which argues that remittances make receiving countries and recipients dependent on senders and sending countries (Binford, 2003). This theory holds that migration drains the human capacities of communities and leads to development that is passive as well as making these communities remittance dependent (De Haas, 2007). This is evidenced in the present analysis where, despite increases in remittance inflows, their relationship with GDP is negative. This is because in Cape Verde recipients do not use the money they receive from remittances for productive purposes but rather they use it as a way of supplementing their incomes for consumption purposes.

The coefficient of Cameroon's remittance inflow is not significant. There is no clear relationship between remittance inflows and GDP. This can be explained by the decreasing amount of remittance inflows into Cameroon as well as the slow pace with which its GDP has been increasing over the years. One possible explanation for the decline in the amount of remittance inflows into Cameroon is the lack of banking infrastructure and the belief that money sent back home is usually used by relatives for unproductive purposes and for indulging in luxurious lifestyles (Ngome & Mpako, 2009). This tends to discourage migrants from sending money back to Cameroon.

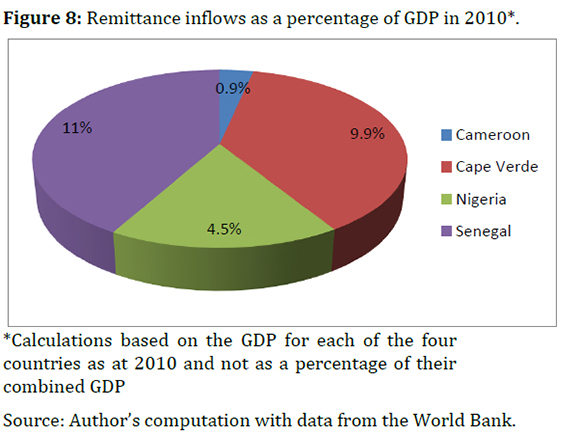

Figure 8 shows the remittance inflows as a percentage of GDP in 2010 for Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal. This year was chosen because remittances are said to be counter-cyclical (see UNESCAP, 2007), tending to increase during times of crisis. Thus, this figure displays the contribution of remittance inflows to GDP in 2010, one year after the global financial crisis. In 2010, the GDP of Cameroon was US$ 23.7 billion and remittances made up 0.9% of this figure. This reinforces the analysis above, that there is virtually no relationship between remittance inflows and GDP in Cameroon. The GDP of Cape Verde was US$ 1.7 billion and remittances formed 9.9% of this amount. Although this is significant, studies by other researchers (see International Monetary Fund, 2008; Ronci et al., 2008; Akesson, 2010) have revealed that remittance inflows as a percentage of GDP have steadily declined over the years, falling from around 25% in the 1970s to barely 9% in the 2000s. The GDP of Nigeria was US$ 369.1 billion and remittances formed 4.5% of this value. This percentage is relatively low considering Nigeria ranks first as the recipient of the greatest amount of remittances in sub-Saharan Africa (see Orozco, 2003; Ukeje & Obiechina, 2013). Lastly, the GDP of Senegal was US$ 13 billion and remittances formed 11% of this amount. This supports the literature that remittances to Senegal are usually used for productive purposes (see Orozco et al., 2010; Randazzo & Piracha, 2014). It can therefore be concluded that the percentage of remittance inflows contributed the most to GDP in Senegal (11%) and remittance inflow as a share of GDP in 2010 was the lowest in Cameroon (0.9%).

Conclusion

This paper, using data sets from the World Bank, critically evaluated the impact of remittances on economic growth in Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal. It used the developmentalist, dependency and pluralist views as the framework within which the analysis was conducted. Using linear regression, analysis was made to ascertain the relationship between remittance inflows and GDP. The analysis reveals that there is a positive relationship between remittance inflows and GDP in Senegal and Nigeria. However, the relationship between remittance inflows and GDP was negative for both Cameroon and Cape Verde. This study also provided evidence that it is not enough for remittances to increase within a country without them being used for productive activities as, without such practices, remittance inflows cannot contribute to development within receiving countries.

Recommendations

Focusing on the findings of this study, the following recommendations are made to improve the impact of remittances on economic growth in Cameroon, Cape Verde, Nigeria and Senegal. First, remittance inflows need to be invested in productive sectors. This is because without such investments the inflows cannot play any significant role in the economy. Second, governments will have to expand the financial sector and make the process of transfer of remittances to home countries much easier and less expensive. This will enable the economy to capture remittance inflows that come in through informal channels which are usually difficult to capture officially. Lastly, countries will have to regulate their remittance outflows. This is essential for Cameroon and Cape Verde. For Cameroon, there have been periods when remittance outflows far exceeded remittance inflows and this does not augur well for economic growth. Cape Verde on the other hand has seen its remittance inflows steadily falling for the period. Although the fall in inflows has not yet exceeded outflows, should this trend continue, it could lead to a situation where the country will be experiencing negative returns which will not be good for economic growth. Hence, the government will have to implement policies that will encourage migrants and recipients to invest remittances in productive sectors.

References

Akesson, L. 2010. Cape Verdean notions of migrant remittances (pdf). Cadernos de Estudos Africanos:140-159. From < http://cea.revues.org/pdf/168> [Retrieved 4 June 2015].

Atekmangoh, C. 2011. Expectations Abound: Family Obligations and Remittance Flow amongst Cameroonian "Bushfallers" in Sweden. A Gender Insight. Masters' thesis. Sweden: Lund University. [ Links ]

Binford, L. 2003. Migrant remittances and (under) development in Mexico. Critique of Anthropology, 23(3): 305-336. [ Links ]

Carling, J. 2002. Cape Verde: Towards the end of emigration (online). From <http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/cape-verde-towards-end-emigration> [Retrieved 4 June 2015].

Cisse, F. 2011. Senegal. In: Mohapatra, S & Ratha, D (Eds.). Remittances and the Markets. Washington D.C.: World Bank. [ Links ]

Coetzee, J.K., Graaf, J., Hendricks, F. and Wood, G. (Eds.). 2001. Development: Theory, Policy and Practice. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

De Haan, A. 2000. Migrants, livelihood and rights: The relevance of migration in development policies. Social Development Working Paper No. 4. London: Department for International Development. From <http://62.189.42.51/DFIDstage/Pubs/files/sdd_migwp4.pdf> [Retrieved on 10 May 2015]. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2007. Remittances, migration and social development: A conceptual review of the literature. Programme on Social Policy and Development, Paper No. 34. Geneva: UNRISD. [ Links ]

De Haas, H. 2010. Migration and development: A theoretical perspective. International Migration Review, 44(1): 227-264. From <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2009.00804.x/epdf> [Retrieved 10 May 2015]. [ Links ]

Department for Economic and Social Affairs, 2013. International Migration Report 2013. (pdf). New York: United Nations. From <http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/migration migrationreport2013/Full_Document_final.pdf> [Retrieved 10 May 2015].

Fajnzylber, P. and Lopez, J.H. 2007. Close to Home: The Development Impact of Remittances in Latin America. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. [ Links ]

Imai, K., Gaiha, R., Ali, A., and Kaicker, N. 2012. Remittances, growth and poverty: New evidence from Asian countries. (pdf) From <http://www.ifad.org/operations/projects/regions/pi/paper/15.pdf> [Retrieved 10 May 2015].

Maimbo, S. and Ratha, D. (Eds.). 2005. Remittances: Development Impact and Future Prospects. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. [ Links ]

Massey, S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., and Edward, T. 1998. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Neuman, L.W. 2000. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 4th edn. Needham Heights, MA: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Ngome, I. and Mpaka, J. 2009. Cameroon: In-flow of remittances (online). From <http://www.africafiles.org/article.asp?ID=21792> [Retrieved 4 June 2015].

Nyamwange, M. 2013. Contributions of remittances to Africa's development: A case study of Kenya. Middlestates Geographer, 42: 12-18. [ Links ]

Oluwafemi, A. and Ayandibu, A. 2014. Impact of remittances on development in Nigeria: Challenges and prospects. Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 5(3): 311-318. [ Links ]

Orozco, M. 2003. Remittances, markets and development in Inter-American Dialogue. Research Series. Washington, D.C.

Orozco, M., Burgess, E. and Massardier, C. 2010. Remittance transfers in Senegal: Preliminary findings, lessons, and recommendations on its marketplace and financial access opportunities. International Migration Paper No. 109, Geneva: International Labour Office. From<http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_177453.pdf> [Retrieved 10 May, 2015]

Orozco, M. and Mills, B. 2007. Remittances, opportunities and fair financial accessopportunitiesinNigeriaFrom http://www.thedialogue.org/PublicationFiles/NigeriaAMAP%20FSKG%20%20Nigeria%20Remittances-%20FINAL.pdf [Retrieved 4 June 2015]

Pop, G. 2011. Cape Verde. In Mohapatra, S & Ratha, D (eds) Remittances and the Markets. Washington D.C.: World Bank. [ Links ]

Randazzo, T. and Pirancha, M. 2014. Remittances and household expenditure behavior in Senegal (pdf). Discussion Paper IZA No. 8106. From <http://ftp.iza.org/dp8106.pdf [Retrieved 4 June 2015].

Ronci, M., Castro, E. and Shanghavi, A. 2008. Cape Verde (pdf). IMF Country Report. From <https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2008/cr08243.pdf> [Retrieved 4 June 2015].

Siddique, A. (2010). Remittances and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka. Discussion Paper (pdf) From <http://www.science.uwa.edu.au/__data/assets/rtf_file/0010/1371952/10-27-Remittances-and-Economic-Growth.rtf> [Retrieved on 10 May 2015].

So, A. 1990. Social Change and Development. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Taylor, J. and Wyatt, T. 1996. The shadow value of migrant remittances, income and inequality in a household-farm economy. Journal of Development Studies. 32(6): 899-912. [ Links ]

Tolentino, N.C. and Peixoto, J., 2011. Migration, Remittances and Development in Africa. The Case of Lusophone countries. Background Note. International Organization for Migration/ACP Observatory on Migration (pdf). From www.acpmigration-obs.org/sites/default/files/EN-BN03PALOP.pdf [Retrieved 11 May 2015].

Ukeje, E.U. and Obiechina, M.E. 2013. Workers' remittances - economic growth nexus: Evidence from Nigeria using error correlation methodology. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 3(7): 212-227 (pdf) From <http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_3_No_7_April_2013/24.pdf> [Retrieved 4 June 2015]. [ Links ]

UNECA, 2013. Diaspora remittances and other financial flows in Africa (pdf). From <http://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/AEC/2013/aec_sent_29_july_2013.pdf> [Retrieved.10 May 2015]

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2007. Workers' remittances, economic growth and poverty in developing Asia and the Pacific countries. Working Paper 07/01. Bangkok: United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. [ Links ]

UN-INSTRAW and UNDP. 2010. Migration, Remittances and Gender. Responsive Development - Case Studies: Albania, the Dominican Republic, Lesotho, Morocco, the Philippians, and Senegal (pdf). From <http://www.unwomen.org/~/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2010/casestudy-executivesummary-migration-remittances-genderresponsivedevelopmemt-en.pdf> [Retrieved 4 June 2015].

Watkins, C. 2010. Beyond remittances: Sustainable diaspora contributions and development in Cape Verde, West Africa. Masters' thesis. USA: Cornell University. Available at: <http://www.mdc.gov.cv/index.php/documentos/doc_download/9-tese-calliewatkins-beyond-remittances-susteinable-diasporacontributions-and-development-in-capeverde> [Retrieved 4 June 2015] [ Links ]

World Bank. 2014a. Migration and Development Brief. Issue 23. Washington D.C.: World Bank. [ Links ]

World Bank. 2014b. Migration and Development Brief Issue 22. Washington D.C.: World Bank. [ Links ]