Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.1 no.2 Cape Town Mai./Ago. 2015

ARTICLES

International Migration in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Call for a Global Research Agenda

Mulugeta F. DinbaboI; Sergio CarciottoII

ISenior Lecturer at the Institute for Social Development, Faculty of Economic & Management Science, University of the Western Cape (UWC), South Africa. He holds a PhD in Development Studies from the University of the Western Cape, South Africa

IIDirector of the Scalabrini Institute for Human Mobility in Africa, PhD Candidate in Political Studies at the University of Cape Town. He holds an MA in Development Studies from the University of the Western Cape, South Africa. This Paper was presented at the Human Development and Capability.Association (HDCA) 2015 Conference Capabilities on the Move: Mobility and Aspirations. Washington, D.C., USA September 10-13, 2015

ABSTRACT

Research on international migration has brought about remarkable awareness within the global research community, stimulating some theorists and policymakers to talk about 'international migration' as a field for research. A number of research organizations have also adopted various methods of inquiry to examine and change their research agendas and practices. Although much is known about international migration, there are still many unanswered questions. Formulating a comprehensive agenda that is well informed by research can have a real influence on the lives of migrants throughout the world. It is also believed that the outcome of this research will help the ways in which concerned organizations think and act while dealing with the situation of international migrants. This research is aimed at drawing an inclusive research agenda that is better informed by distinguishable human rights requirements. The research agenda presented here is the result of the contribution of nearly 35 purposely selected researchers from various organizations working in the area of international migration in sub-Saharan Africa. The knowledge base that is produced from this study can yield data and information to governmental and non-governmental organizations that are dealing with international migration in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: international migration, sub-Saharan Africa, policy makers, research agenda.

Introduction

The ever increasing worldwide human movement, the growth and complexity of migratory practice and its effect on migrants, families and communities have all contributed to make international migration a major area for academics and researchers from various disciplines. International migration is an escalating practice of our times with millions of people flowing across geographical boundaries (Hatton, 1995; Lee, 1966; Maddala & Kajal, 2009). Nevertheless, human mobility in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has a long history spanning several centuries. The region has a highly mobile population composed of nomads, frontier workers, highly skilled professionals, refugees and undocumented migrants (Adepoju, 2000).

The discourse around migration patterns in SSA is dominated by myths and false assumptions. First, the widespread perception that migrants from SSA countries are ready to flock onto the shores of Europe is contradicted by official data from the World Bank showing that migration in SSA is largely characterized by intra-regional movements which account for 65 per cent of the total population of migrants who move to other African countries (Ratha et al., 2011). Second, the impression that SSA countries are urbanizing at a fast pace with a massive influx of rural migrants is also deceptive. The rapid population growth of African towns and large cities due to a natural increase of the population in fact cannot be directly linked to migration. On average, the rate of urbanization in the SSA region is estimated to be 2 per cent with the exception of a few countries (Burkina Faso, Ghana and Cameroon) which are urbanizing faster and others (Zambia, Ivory Coast, Central African Republic and Mali) which have even faced a process of de-urbanization (UN-Habitat, 2014). A reduced contribution of net in-migration to urban growth it is not caused by less internal mobility though but rather by 'significant rates of circular migration' (Potts, 2009). This means that migrants are no longer residing in urban areas for long periods of time as it has become more difficult for them to secure employment and a decent standard of living in a highly informalized urban economy. Therefore, circular migration in the SSA represents an enduring mobility pattern and a family survival strategy for rural migrants. Third, to dispel the myth that poverty reduction, economic growth and human development will halt migrants it is necessary to point out that development might lead to an increased level of migration. In 2014, the SSA region sustained a growth of 4.3 per cent (World Bank, 2014) driven by an increase in the internal demand for goods and services, investment in mining activities, infrastructure for transport and communication and improvement of agricultural productivity (IMF, 2014). This widespread growth in the per capita GDP has also improved the Human Development Index (HDI) of many countries in the region, meaning that more people had access to water, health care and education services. A higher level of human development will not only increase social, human and material capital but will also boost people's aspirations to move, leading to more migration (de Haas, 2010; 2011; Flahaux & de Haas, 2014).

Finally, SSA is largely depicted as a region where people are forced to flee because of conflicts and social unrest. Despite the fact that four of the five countries with the highest number of refugees per USD of GDP per capita belong to the SSA region (Ethiopia, Kenya, Chad and South Sudan), refugees account only for 16 per cent of the total population of international migrants in Africa (UNHCR 2013).

Debunking myths around migration patterns in SSA allows us to reflect on the more realistic trends of this phenomenon. Human mobility in SSA is characterized by sub-regional movements between neighbouring countries and is driven primarily by economic factors rather than by conflicts. Forms of circular labour migration, complemented by 'less structured forms of mobility', both at domestic and international level, also reveal an increase in the percentage of migrant women as in the case of Southern Africa (ACMS, 2015, 4).

As the vast majority of those who move are labour migrants, expectations were raised to achieve regional integration and remove restrictions to free movements in SSA. On the contrary, many African states have promoted restrictive immigration policies in the attempt to reduce the influx of undocumented migrants. These measures, driven by security concerns, have led to the exploitation of migrants and to the systematic violation of their basic rights. It is, therefore, necessary to reflect on a global research agenda for SSA informed by distinguishable human rights requirements and to identify the founding principles of an ethical paradigm of migration.

In the following sections, this paper presents the methodological approach used (section 2), elaborates the theoretical and conceptual framework of a rights-based approach (RBA) to international migration (section 3), and analyses the experience of researchers and development of a rights-based global agenda (section 4). The final section provides conclusions.

Research Methodology

The research methodology employed a mix of secondary data analysis and field data collection to understand the issues involved in international migration in SSA. According to Bryman (2008), in the social sciences the mixed methods approach enables a thorough investigation of the phenomenon under study and therefore remains highly relevant in generating knowledge for policy making purposes. In general, a purposefully selected group of 35 researchers from fourteen SSA countries1 and 25 organizations in SSA were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire. These included researchers and institutions involved in research on international migration, representatives of civil associations, and associations undertaking research on international migration. This empirical research helped to examine the different views, ideas; experiences and perspectives of the participants towards international migration in SSA: a call for a global research agenda.

Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

A rights-based approach is a theoretical and conceptual model that helps to examine disparities which lie at the centre of social and economic development problems and entrench prejudiced practices impeding development progress (Cornwall & Nyamu-Musembi, 2004; UNHCR, 2002). It also strives to develop awareness among institutions, civil society organizations, governments and other pertinent stakeholders on how to fulfil their duties, to respect and protect human rights, and to empower individuals and communities to claim their rights (UNICEF, 2007).

In a RBA, the plans, policies and processes of development are attached in a system of rights and corresponding obligations established by international law. This helps promote equality among citizens and brings about sustainable development/empowerment, especially for the most marginalized groups of people, in order to take part in policy development, and also to hold accountable those who have a duty to act (Cornwall & Nyamu-Musembi, 2004).

This methodology warrants the participation of all stakeholders, transparency and accountability, and the awareness of the rights of the historically excluded people. It strives to examine disparities which lie at the heart of development problems and discriminations that hinder growth (Cornwall & Nyamu-Musembi, 2004). The rationale for a RBA is usually a blend of two major points. First, the intrinsic rationale acknowledges that an RBA is the right thing to do from a moral perspective. In this regard, Baggio (2007) noted that although it is not possible to identify universally applicable methods for the governance of migration, it is feasible to identify some universal principles that constitute the basis for an ethical approach to migration policies and practices. He suggested five principles that firmly respond to moral obligations: (i) Promotion of Human Rights and Human Dignity; (ii) Superiority of the Common Good, summarized as the superiority of the common good over personal interests and individualism; (iii) Universal Destination of Goods and Solidarity which represents the moral duty of many religions to be supportive towards disadvantaged people and also refers to the principle of philanthropy and solidarity; (iv) Global Stewardship and Co-Responsibility, an ethical principle based on the collective duty of the proper use and development of natural and environmental resources. According to this principle, everyone is free to access resources where they are as there is a moral obligation on those who have more to share with those who have less; (v) Global Citizenship, a principle based on the concept of 'global fraternity' which strongly undermines contemporary immigration policies whose main pillars are national sovereignty and the security of nationals. Underlying the paradoxes of a globalized world where goods and capital can move freely while human beings are often constrained, these principles constitute the backbone of an ethical paradigm to assess the contemporary scenario of human mobility.

Second, an active foundation identifies that a RBA leads to better and more sustainable social and economic development outcomes (UNHCR, 2002). In general, RBA comprises the incorporation of rights, rules, values, and ethics in policy, identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation to help ensure that the programme respects rights, in every direction, and encourages their further awareness where possible.

According to UNICEF (2007, cited in Dinbabo (2013)), a human rights based approach is all about capacity building, and enabling people to claim their rights and enhancing the ability of individuals and institutions who are accountable for respecting, safeguarding and rewarding rights. Dinbabo (2013) further indicates that providing people with the opportunities to participate will ensure ownership and decision making that impacts on their human rights. As Cholewinsky and Taran (2010: 18) suggested, 'a right-based approach to migration is placement of universal rights norms defined by the relevant international instruments as central premises of national migration legislation, policy, and practice founded on the rule of law'. In addition, how a RBA is implemented appears to have more to do with the context and objectives of an agency or organisation than the definition of the approach. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) gives a definition of rights-based approach:

A human rights-based approach to migration means that all migrants are right-holders, and therefore they are entitled to participate in the design and delivery of migration policies, to challenge abuse and human rights violations, and to demand accountability. Ultimately, many migrants will remain on the periphery of development, literally and conceptually, unless they are enabled to participate equally in development. (OHCHR, 2013: 8).

The recognition by international organizations and civil society groups of the importance of promoting, protecting and upholding migrants' fundamental rights has compelled them to urge states, in both sending and receiving countries, to adhere to international human and labour standards. In part, this major change has been the outcome of an increasing appreciation that needs-based or service-delivery methods have failed to significantly decrease the problem (Ledogar, 1993; Oestreich, 1998; Woll, 2000; UNICEF, 2007; Dinbabo, 2011) but is also motivated by the numerous human rights violations reported by media which often target vulnerable groups. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has identified several highly vulnerable categories including: women workers, especially those involved in domestic service, temporary and seasonal migrant workers, children, migrant workers in irregular status and victims of trafficking (ILO, 2010).

It can be argued that the RBA is not free from pitfalls; Munch and Hyland (2013) challenged the dominant paradigm, advocated by international organizations, of a RBA to migration based on universalistic individual rights promoted by Western countries. They suggested an alternative and transformative model which affirms the central role of regional integration and social movements, in particular trade unions, to legitimate labour rights for all migrants independently from the dominant human rights discourse. Baggio (2015) criticized the fact that the RBA is based only on the Enlightenment ideals of freedom and equality but not on 'fraternity' or 'brotherhood'. He further noticed that the RBA's conceptual framework is limited to the prevention and punishment of human rights violations but does not express the duty of individuals, groups, societies and states to promote the welfare of every person, family and collectivity (ibid.).

International Legal Frameworks/Instruments

The RBA to migration is informed by a set of international standards found in international instruments and conventions that provide basic rights to all human beings and in some cases apply specifically to migrant workers. Moreover, these sets of rights are applicable to all individuals regardless of their immigration status, documented or undocumented. For example, numerous studies (O'Manique, 1990; Ledogar, 1993; Oestreich, 1998; Woll, 2000; O'Donnell, 2004; Few, Brown & Tompkins, 2007; UNICEF, 2007; Moeckli, 2012; Dinbabo, 2013; Dinbabo & Nyasulu, 2015) show that the relationship between migration and human rights can be found at all stages in the migratory cycle: in the country of origin, during transit, and in the country of destination. When a migrant crosses a border, the act that defines international migration, international legal instruments intersecting migration and human rights become enforceable.

Three major intercontinental legal instruments, developed by the United Nations, comprise the International Bill of Human Rights namely: (i) the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights; (ii) the 1966 International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and (iii) the 1996 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that "Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country". This right guarantees the right of emigration covering not only immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers, but also internally displaced persons, economic migrants or even students. Dinbabo and Nyasulu (2015) show that if a migrant entered a country or remained there without authorization that does not nullify the state's duty under international law to protect his or her basic rights without any discrimination, for example, against torture, degrading treatment, or forced labour.

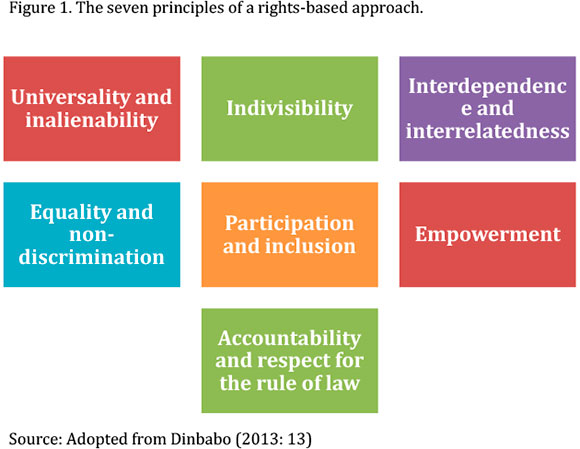

A RBA is characterized by seven fundamental principles (see Figure 1) including the universality and inalienability of human rights and equality and non-discrimination of all individuals which underlie labour and human rights.

According to Moeckli (2012), equality and non-discrimination means that all human beings, regardless of colour, race, religion, etc. are equal as human beings and, by virtue of the intrinsic self-esteem of any individual, they are eligible to exercise their rights without discrimination. A RBA requires a specific effort to target unfairness and discrimination; protections need to be included in all kinds of legal tools to protect the rights and well-being of neglected groups of people.

ILO Conventions and Recommendations set labour standards and rights at work which aim to provide a 'common framework to regulate the rights and duties of labour migrants' (Nshimbi & Fioramonti, 2013: 10). The 1998 ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work is based on eight conventions which make explicit the 'human rights at work' (ILO 2010:120) and is articulated in four different categories: (i) freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining2; (ii) the abolition of forced labour3; (iii) equality and non-discrimination in employment and occupation4; (iv) the elimination of child labour5 (ILO 2007: 1). Two ILO Conventions and their accompanying Recommendations specifically deal with migrant workers. These are the Migration for Employment Convention (Revised), 1949 (No. 97) and the Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention, 1975 (No. 143). These two international legal instruments provide the standard for giving a direction on what should constitute the basic elements of major labour migration policy, the safeguarding of workers, the establishment of their potentials in order to measure and facilitate as well as to control migration movements. Furthermore, they aim to control the situations in which labour migration for employment occurs and labour trafficking, and try to control any kinds of illegal employment of migrants with the aim of preventing and eliminating abuses (ILO, 2007).

A further useful tool developed by the ILO is the Multilateral Framework on Labour Migration: non-binding principles and guidelines for a RBA to labour immigration which provides a 'collection of principles, guidelines and best practices on labour migration policy, derived from relevant international instruments and a global review of labour migration policies and practices of ILO constituents' (ILO, 2006: iv). In particular, Principle 8 of the framework deals with the protection of migrant workers as a cornerstone of a RBA to labour migration:

The human rights of all migrant workers, regardless of their status, should be promoted and protected. In particular, all migrant workers should benefit from the principles and rights in the 1998 ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its Follow-up, which are reflected in the eight fundamental ILO Conventions and the relevant United Nations human rights Convention. (ILO, 2006: 15).

Another relevant international instrument that deals with the protection of migrant workers' rights is the 1990 International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (ICRMW) which form, together with the two ILO Conventions (No. 97 and No. 143) the International Charter on Migration (Cholewinsky & Turan, 2010: 20). Other binding UN instruments are the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and the 2000 UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and its two protocols, the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children and the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air.

In addition to the ICRMW and the ILO Conventions, the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol protect the rights of refugees and all people in need of international protection. The Convention is 'both a status and rights-based instrument and is underpinned by a number of fundamental principles, most notably non-discrimination, non-penalization and non-refoulement (UNHCR, 2010: 3).

Regional Legal Frameworks/Instruments

Amongst the regional human rights instruments, the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights6 adopted in 1981 by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) aims at establishing a framework for the promotion and protection of human and people's rights in the African continent. The Charter lists a set of basic human rights applicable to all human beings of which some are particularly relevant to migrants. Article 12(2) and Article 15 respectively state that: 'every individual shall have the right to leave any country including his own, and to return to his country' and that 'every individual shall have the right to work under equitable and satisfactory conditions, and shall receive equal pay for equal work.' Furthermore, the right of non-discrimination is enshrined in Article 2, while the rights to access basic health care and education for all individuals are promoted respectively by Articles 16 and 17 of the Charter.

A second regional pillar legal instrument for the RBA to migration is the Migration Policy Framework for Africa (MPFA) which deals with nine key migration issues including migrants' human and labour rights (AU 2006: 1). The document invites states to 'incorporate provisions from ILO Conventions No 97 and No 143 and the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families into national legislation', as well as 'to promote respect for and protection of the rights of labour migrants including combating discrimination and xenophobia through inter alia civic education and awareness raising activities' (AU, 2006: 8). The MPFA enlists the upholding of the humanitarian principles of migration amongst states' key priorities and clearly states that:

Ensuring the effective protection of the human rights of migrants is a fundamental component of a comprehensive and balanced migration management system [...] Safeguarding the human rights of migrants implies the effective application of norms enshrined in human rights instruments of general applicability as well as the ratification and enforcement of instruments specifically relevant to the treatment of migrants (AU, 2006: 24).

The MFPA, which is not legally binding, also recommends states should meet their humanitarian obligations to refugees by adopting adequate national policies and to strengthen mechanisms to protect internally displaced people and victims of trafficking. Issues relating to the protection and non-discrimination of refugees are also addressed by the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS): comprises 15 states7 and currently its regional policy framework on migration is regulated by the ECOWAS Treaty and the 1979 ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement of Persons, Residence and Establishment both of which protect the right to freedom of movement (right of entry), right of residence and right of establishment (Atsenuwa & Adepoju, 2010). The Protocol had a 15-year, three-phase implementation process gradually to abolish visa requirements for ECOWAS citizens, promote the right of residence and lastly the right of establishment and seek employment. The ECOWAS Common Approach to Migration, adopted in 2008, is a regional programmatic document which reaffirms the applicability of basic human rights expressed in all adopted international legal instruments to migrants, including women and victims of trafficking, and refugees. Amongst its objectives the ECOWAS Common Approach to Migration seeks to: (i) formulate an active integration policy for migrants from ECOWAS member states; (ii) combat exclusion and xenophobia; (iii) encourage member states and their EU partners to ratify the UN Convention on the Rights of Migrants; (iv) put in place regional mechanism to monitor the UN Convention on the Rights of Migrants and (v) put in place mechanisms for granting rights of residence and establishment to refugees from ECOWAS countries (ECOWAS, 2008: 10).

The East African Community (EAC): comprises five states of which Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda were the founding members,8 joined in 1999 by Burundi and Rwanda. All member states signed the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community9 committing themselves to strengthen their political and socio-cultural ties and to achieve full economic integration and sub-regional cooperation (EAC, 2009a). The EAC regional legislative framework also comprises the Protocol on the Establishment of the EAC Common Market which came into force in 2010, upon ratification of all member states, and allowed free movement of goods, capital and labour among partner states (Nshimbi & Fioramonti, 2013). The Protocol guarantees the rights of establishment and residence for all EAC citizens and their families and reiterates the importance of non-discrimination as one of its underlying principles (EAC, 2009b). In particular, Article 3 and Article 10(2) of the Protocol call for the observation of the principle of non-discrimination respectively for non-nationals, citizens and foreign workers in relation to remuneration and other conditions at work (ibid.). Moreover, to reduce the constraints regarding the portability of social security benefits, an additional annex on social security was drafted with the ILO's technical assistance (ILO, 2010).

The Southern African Development Community (SADC): comprises 15 member states.10 Despite the declared objectives of the 1992 SADC Treaty to promote regional cooperation and to reduce obstacles to the free movement of capital, goods, services and people (SADC 1992) very little has been achieved so far by member states. The 1995 Draft Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons in the Southern African Development Community, a three-phase process which envisioned the possibility for SADC citizens to 'enter freely the territory of a Member State for the purpose of seeking employment' (SADC, 1996) encountered fierce resistance from Botswana, Namibia and, in particular, South Africa. The implementation of the 'free movement' provision was, in fact, considered by the authorities to be detrimental for the socio-economic conditions and the social well-being of South African citizens (Oucho & Crush, 2001). In 2005, the Free Movement Protocol was replaced by the Protocol on the Facilitation of Movement of Persons which established a visa-free system for SADC countries and aimed at harmonizing immigration practices (SADC, 2005). The Protocol, which is a binding document, was signed by 13 member states11 but has not came into force yet because it requires a minimum of two-thirds to ratify it.12 The timid progress to eliminate obstacles to free movement and to draft a regional labour migration policy reveals that 'migration is not a key priority of member states compared with more prominent issues such as border control and the fight against irregular migration' (Segatti, 2011: 29).

Empirical Data Presentation and Analysis

Examining researchers' experiences with a RBA to research in international migration in the context of SSA is considered an important element in this study. In this regard, McIntyre, Byrd and Foxx (1996) argue that analysing researchers' experiences is an important component in social science. Garibaldi (1992) notes that most social science research projects have incorporated more and more experience analysis into their research programmes. Field data analysis indicated that the majority of respondents were familiar with the RBA framework. There was constant mention of rights-based research that the majority of the respondents had previously employed to advocate for socio-economic and political rights of international migrants and marginalized groups of people through their organizations. They also indicated that a rights-based research approach to international migration is very relevant in the context of SSA. However, participants in the research made it clear that the modalities of implementation of a rights-based research approach to international migration are not clear.

In this regard, the survey participants indicated that there is a need for increased awareness, collaboration and networking, amongst government and non-government offices, private service providers, community based organisations and churches in communities, and research organizations, in terms of effectively utilizing a rights-based research approach to international migration.

Based on information obtained, some of the respondents indicated that looking at research on international migrants through a 'rights' lens helped them in designing a new way of devising a research framework and in orienting themselves progressively towards addressing rights through advocacy and via strengthening of civil society. Researchers also raised their concern about the general lack of a sound theoretical framework and strong empirical basis for a rights-based research approach to migration. Some also raised their concern about the researchers' expertise in rights-based research approach, methodology and scarcity of research findings and evaluation strategies.

In sum, each of the respondents' cases demonstrates that the rights-based research approach will need to develop its in-house capacity to assess, interpret, and synthesize information about the rights issues that underpin economic, social, political and cultural matters and to design programmes that seek to address them. In this regard, several respondents indicated their opinions, suggestions and views on the development of a human rights measurement framework. Some respondents also suggested the need for understanding and building consensus within the international rights-based research approach

Strengths: several respondents stated that a rights-based research approach to migration helped in deepening the focus on disadvantaged and socially marginalized migrants as well as fostering respect and dignity and enhancing the opportunities of neglected migrants. A large number of respondents also indicated that the presence of the basic rights contained in the two International Covenants, i.e., the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) are important tools in terms of undertaking research on the rights of the migrants. An exclusive response received from a few of the researchers indicated that the strengths of the rights-based research approach is reinforced by important international legal instruments, as emerged from respondents' observations:

...the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 was the first occasion on which the organized community of nations ... made a Declaration of human rights and fundamental freedoms....

..it is conceived as "a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations," the Universal Declaration ... has become just that: a yardstick by which to measure the degree of respect for, and compliance with, international human rights standards...

.it is one of the basic instruments of human rights....states a common

understanding of the peoples of the world concerning the inalienable and inviolable rights of all members of the human family and constitutes an obligation for the members of the international community...

...The human rights declaration consists of 30 articles setting forth the civil and political, and economic, social and cultural rights to which all persons are entitled, without discrimination. This means international migrants are part of the beneficiaries of the human rights declaration...

..characterizes these rights as indispensable for human dignity and the free development of personality, and indicates that they are to be realized "through national effort and international cooperation." At the same time, it points out the limitations of realization, the extent of which depends on the resources of each State..

Weaknesses: a number of respondents indicated that the main weakness is a very poor collaborative research network. Respondents believed that a pan-African research network on rights-based research approach to international migration would bring a platform for sharing research outputs and experiences. Respondents also believed that collaborative research networks are helpful in designing and developing the research capacity of smaller, emerging researchers and institutions in SSA. According to them, collaborative research networks encourage these institutions and researchers to become familiar with a research system focussed on results by partnering with similar organizations in areas of common interest. Respondents indicated that such kinds of partnership will benefit all of the stakeholders involved.

Opportunities: almost all the respondents agreed about the existence of various types of legislative and policy framework as an opportunity to undertake rights based research on international migration. In this regard, respondents indicated that, in fact, a significant number of SSA countries have either completed or are in the process of completing major law reforms on migrants. This, therefore, shows a great opportunity to work in the field and commitment for the furtherance of international migrants' rights on the continent. For example, respondents pointed out that, continentally, the African Union seeks to build an African Economic Community (AEC) and regards eight African Regional Economic Communities (RECs) as crucial in realizing an AEC. To achieve this, the Abuja Treaty (Paragraph 2 (i) Article 4) encourages member states eventually to do away with barriers "to the free movement of persons, goods, services and capital and the right of residence and establishment." The Abuja Treaty's Article 6(e) even fleshes out four activities for establishing an African Common Market (ACM). Additionally, Article 71(e) implores AU members to adopt employment policies that enable people to move freely within Africa. In order to achieve this, Article 71(e) urges members to establish and strengthen labor exchanges that make possible the harnessing of available skilled labour of a member state in other AU states where such labour is needed but is in short supply. The AU's hope is that Africa will be an economic community by 2028.

As an opportunity, respondents further indicated that the two migration policy frameworks in Africa, namely, the African Common Position on Migration and Development (ACPMD) and the Migration Policy Framework for Africa (MPFA), warrant some attention. The ACPMD promotes prioritization of migration-related policy, recommendations and actions on national, continental and international levels. Similarly, the MPFA underscores the significant role that migration plays in development and appeals to all African Regional Economic Communities members to craft policies designed to boost continental development. Unfortunately, the MPFA is but a reference document that is not legally binding from which AU members and RECs can borrow issues that they consider valuable and appropriate to their migration settings.

However, some of the researchers also indicated that the degree to which these instruments and laws will improve international migrants' lives depends greatly on how state parties implement them and adopt domestic measures to comply with their international obligations. A number of respondents commented that the list of adverse factors with which the implementation and enforcement of migration laws has to contend, especially in Africa, is still very long.

Challenges: analyses of the feedback of numerous respondents indicated that despite the theoretical strength of this method, as was stated in the earlier section, some of the respondents indicated that the RBA to international migration is not free from pitfalls. According to them, there are problems of operationalization and consensus about the RBA among researchers, and its practical implementation in the context of Africa. For example, some respondents indicated that although values of human rights notions such as non-discrimination and equality are not special values only for developed countries, it is assumed that human rights dialogue is not as operational in Africa as in Europe due to its origin in the West. Some respondents also pointed out that a RBA to international migration remains perceived in international law as rights enforceable only against the state or its agents. Some respondents also indicated their feelings about the progressive breaches of human rights which are taking place in SSA because of the actions of non-state actors. In general, they believed that human rights violations occur at different levels.

The above evidence suggests that there are opportunities and challenges for conducting a rights-based research approach to international migrants in SSA. However, the researchers stated that research should be aimed at strengthening the resilience of vulnerable migrants, which is particularly relevant if participatory approaches and tools are used. In general, a rights-based research approach to international migration has to be linked with state agencies, NGOs and the private sector to bring the voice of civil society to SSA forums. Respondents also indicated that a rights-based research approach should influence the political agenda in SSA on a range of migrants' rights issues.

Key Priorities for a Global Research Agenda

Respondents suggested that despite the numerous laws, legal instruments, and policy frameworks, to which most governments in SSA may have acceded, the promotion of migrants' rights issues for many countries still remains under-explored. In this regard, several researchers in SSA indicated that a global research agenda on migrants' rights should be considered. According to them, the rights of international migrants globally and in the SSA context received thoughtful focus and attention after the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1994 International Convention on Civil and Political Rights and the 1981 African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights. According to the respondents, these international and continental legal instruments establish that governments must ensure that all human rights should be protected.

The result of the field data assessment demonstrates a great demand for urgent action on planning a rights-based global research agenda that responds to the present international migrants' rights situation. In general, the research process identified two interrelated gaps that hinder the successful implementation of a rights-based research agenda. First, insufficient networking, communication and synergy between researchers, practitioners, government officials, funding agencies, research organizations and NGOs. Second, an inadequate understanding of the theoretical and conceptual framework of rights-based research exists among scholars in the field. Within the framework of the aforementioned analysis, the study finally brings into focus major observations gained from the analysis and provides key priorities for a global research agenda in SSA. The following is a summary of a research agenda that has been suggested by most researchers in SSA countries.

• Analysis of legal and policy research agendas in the SSA context should be embedded in an approach which is informed by justice and restorative justice practices, as well as focused on especially vulnerable groups (unaccompanied minors, migrants deprived of their liberty, etc.).

• Assessing where opportunities and gaps exist for ensuring that the rights of migrants are included (migrants' access to social services, e.g. health care and grants).

• Evaluating diversion and programming for migrants at risk or in conflict with the law. There is a great need for research into the regulation of issues of migrants at risk and prevailing conditions that threaten them, which, it is suggested, is an area of weakness in the region as a whole.

•Identifying factors determining migration in SSA, social exclusion and xenophobia; and undertaking comparative analysis of policies and practices governing migration in SSA.

•Examining the integration of research on migrants' rights in SSA as an integral part of mainstream African social science research and research on the possibility of developing a network of African researchers.

•Exploring migrants as victims of family violence, including: data collection on victims, particularly over time; family violence prevention and intervention measures.

•Assessing gender and migration. Increasing feminization of migration is unveiling a potential risk (of abuses, exploitation and sexual harassment of women).

Conclusion

This article seeks to provide a thoughtful understanding of a rights-based approach (RBA) to international migration with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). It also suggests the need for a research agenda predicated on the principle of human rights and intertwined with social and economic development. The findings reveal the necessity to address some of the asymmetries of international migration, such as the tension between sovereignty rights and human rights which often leads to the exclusion of non-citizens from social protection, labour rights and human rights.

In this regard, the role of national and regional networking groups comprising researchers, NGOs, practitioners, trade unions, civil society organizations and social movements can contribute to advancing migrants' rights by exercising pressure from the bottom on both states and non-state actors to uphold and enforce international human rights law. Moreover, there is an urgent need to identify universal and widely accepted principles able to inform national and regional migration policies. We suggest that such an ethical paradigm should be based on the following five principles: (i) Promotion of Human Rights and Human Dignity; (ii) Superiority of the Common Good; (iii) Universal Destination of Goods and Solidarity; (iv) Global Stewardship and Co-Responsibility and (v) Global Citizenship.

Building an effective institutional base that drives the design of international migration in sub-Saharan Africa, including establishing networks, publication of the research outputs, facilitating conferences, seminars, workshops, and capacity building programmes should be undertaken. Researchers must have access to data, research outputs, and outcome information so that the impact of international migration in SSA can be evaluated and improved and a standard scientific methodology can be incorporated into the evaluation of technical advances in international migration.

References

Adepoju, A., 2000. Issues and recent trends in international migration in sub-Saharan Africa. International Social Science Journal, 52(165): 383-394. [ Links ]

ACMS, 2015. African Centre for Migration and Societies, Migration, Mobility & Social Integration: Southern African Trends and Their Implications. Presentations to the Portfolio Committee for Home Affairs, 5 May 2015. Available from: http://bit.ly/1eqVzcw (Accessed on 15 June 2015).

Atsenuwa, A.V., and Adepoju, A., 2010. Rights of African Migrants and Deportees: A Nigerian Case Study. Justice Without Borders Project & OSIWA. Available from:

AU, 2006. African Union, The Migration Policy Framework for Africa. Available from: http://bit.ly/1Mr3xAn (Accessed on 24 June 2015).

Baggio, F., 2007. Migrants on sale in East and Southeast Asia: An urgent call for the ethicization of migration policies. In: Caloz-Tschopp, M.C. and Dasen, P. (Eds.).Mondialisation, migration et droits de Ihomme: un nouveau paradigme pour la recherche et la citoyenneté. Globalization, migration and human rights: a new paradigm for research and citizenship, Volume I. Brussels: Bruylant. [ Links ]

Baggio, F., 2015. Reflections on EU border policies: human mobility and borders - ethical perspectives. In: Van der Velde, M. and Van Naerssen, T. (Eds.). Mobility and Migration Choices: Thresholds to Crossing Borders. Farnham: Ashgate. Ch. 12. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. and Bell, E., 2007. Business Research Methods, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cholewinski, R., and Taran, P., 2009. Migration, governance and human rights: contemporary dilemmas in the era of globalization. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 28(4): 1-33. [ Links ]

Cornwall, A., and Nyamu-Musembi, C., 2004. Putting the 'rights-based approach' to development into perspective. Third World Quarterly, 25(8): 1415-1437. [ Links ]

de Haas, H., 2010. Migration and development: A theoretical review. International Migration Review, 44(1): 227-264. [ Links ]

de Haas, H., 2011. Mediterranean migration futures: Patterns, drivers and scenarios. Global Environmental Change, 21(1): S59-S69. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M. and Nyasulu, T., 2015. Macroeconomic determinants: analysis of 'pull' factors of international migration in South Africa. African Human Mobility Review (AHMR), 1(1): 27-52. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M., 2011. Social Welfare Policies and Child Poverty in South Africa: a Micro simulation Model on the Child Support Grant. PhD Thesis, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

Dinbabo, M., 2013. Child rights in sub-Saharan Africa: a call for a Rights-Based Global Research Agenda. Journal of Social Work, 48(1): 271-293. [ Links ]

EAC, 2009a. East African Community, Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community. Available from: (Accessed on 22 June 2015).

EAC, 2009b. East African Community. The East African Community Common Market (Free Movements of Workers) Regulations. Available from: http://bit.ly/1I16hyR (Accessed on 22 June 2015).

ECOWAS, 2008. Economic Community of West African States, ECOWAS Common Approach to Migration. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/49e47c8f11.pdf (Accessed on 2 July 2015).

Few, R., Brown, K., and Tompkins, E.L., 2007. Public participation and climate change adaptation: avoiding the illusion of inclusion. Climate Policy, 7(1): 4659. [ Links ]

Flahaux, M. L. and de Haas H., 2014. African Migration: Exploring the Role of Development and States. Working Paper 105, November 2014. Oxford: International Migration Institute. [ Links ]

Garibaldi, A. M., 1992. Educating and motivating African American males to succeed. Journal of Negro Education, 61(1): 4-11. [ Links ]

Hatton, T.J., 1995. A model of U.K. migration, 1870-1913. Review of Economics and Statistics, 77: 407-415. [ Links ]

ILO, 2006. International Labour Organization, Multilateral Framework on Labour Migration: Non-binding principles and guidelines for a rights-based approach to labour migration. Available from: http://bit.ly/1eqSRnc (Accessed on 15 June 2015).

ILO, 2007. International Labour Organization, Rights, Labour Migration and Development: the ILO Approach. May 2007. Background Note for the Global Forum on Migration and Development.

ILO, 2010. International Labour Organization. International Labour Migration: A Rights-based Approach. Available from: http://bit.ly/1SHOaTD (Accessed on 15 June 2015).

IMF, 2014. International Monetary Fund, Regional Economic Outlook. Sub-Saharan Africa. Available from: http://bit.ly/1KsszQ9 (Accessed on June 14 2015).

Ledogar, R.J., 1995 Implementing the Convention on the Rights of the Child through national programmes of action for children. In: J.R. Himes (Ed.) Implementing the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Leiden: Brill. Ch.3. [ Links ]

Lee, E. S., 1966. A theory of migration. Demography, 3(1): 47-57. [ Links ]

Maddala, G.S., and Kajal, L., 2009. Introduction to Econometrics, 4th Edn. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Magesan, A., 2013. Human rights treaty ratification of aid receiving countries. World Development, 45: 175-188. [ Links ]

McIntyre, D.J., Byrd, D.M., and Foxx, S.M., 1996. Field and laboratory experiences. In: Sikula, J., Buttery, T.J. and Guyton. E. (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Teacher Education. 2nd edn. New York: Macmillan (pp.171-193). [ Links ]

Moeckli, D., 2012. Strategic Trends 2010: Key Developments in Global Affairs. Zurich: Center for Security Studies. [ Links ]

Nielsen, R.A., 2013. Rewarding human rights? Selective aid sanctions against repressive states. International Studies Quarterly, 57(4): 791-803. [ Links ]

Nshimbi, C.C., and Fioramonti, L., 2013. MiWORC Report No. 1. A Region without Borders? Policy frameworks for regional labour migration towards South Africa. Johannesburg: African Centre for Migration & Society. [ Links ]

O'Donnell, G.A., 2004. Why the rule of law matters. Journal of Democracy, 15(4): 32-46. [ Links ]

Oestreich, J.E., 1998. UNICEF and the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Global Governance, 4: 183-198. [ Links ]

O'Manique, J., 1990. Universal and inalienable rights: A search for foundations. Human Rights Quarterly, 14(3): 465-485. [ Links ]

Oucho, J.O., and Crush, J. 2001. Contra free movement: South Africa and SADC Migration Protocols. Africa Today, 48(3): 139-158. [ Links ]

OHCHR, 2013. United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Migrants, Migration, Human Rights and the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda. Geneva, Switzerland 22 May 2013.

Potts, D., 2009. The slowing of sub-Saharan Africa's urbanization: Evidence and implications for urban livelihoods. Environment and Urbanization, 21(1): 253-259. [ Links ]

Ratha, D., et al., 2011. Leveraging Migration for Africa: Remittances, Skills, and Investments. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. [ Links ]

SADC, 1992. Southern African Development Community, Treaty of the Southern African Development Community. Available from: http://bit.ly/1U0UYhE (Accessed on 15 June 2015).

SADC, 1996. Southern African Development Community, Draft Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons in the Southern African Development Community. Available from: http://bit.ly/1LJBwF3 (Accessed on 15 June 2015).

SADC, 2005. Southern African Development Community, Protocol on the Facilitation of Movement of Persons in the Southern African Development Community. Available from: http://bit.ly/1MQfVYG (Accessed on 15 June 2015).

Segatti, A., 2014. Regional Integration Policy and Migration Reform in SADC Countries. In: Streiff-Fenart, J. and Segatti, A. (Eds.) The Challenge of the Threshold: Border Closures and Migration Movements in Africa. Plymouth: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

UN-Habitat, 2014. The State of African Cities: Re-imagining Sustainable Urban Transitions. Available from: http://bit.ly/1IoUv53 (Accessed on 17 July 2015).

UNHCR, 2002. Livelihood Options in Refuge Situations. A Handbook for Promoting Sound Agricultural Practices. Geneva: United Nations. [ Links ]

UNHCR, 2010. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugee. Geneva: United Nations. [ Links ]

UNHCR, 2013. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Statistical Yearbook 2013. Available from: www.unhcr.org/statistics (Accessed on 17 July 2015).

UNICEF, 2007. United Nations Children's Fund, Annual Report. New York: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Woll, J., 2000. Real Images: Soviet Cinemas and the Thaw. London: IB Tauris. [ Links ]

World Bank, 2014. Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr Accessed on 25 July 2015).

1 Angola, Cameron, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

2 Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No 87); Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No 98).

3 Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105); Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105).

4 Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111); Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100).

5 Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138); Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182).

6 http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/z1 afchar.htm

7 Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Cote d'Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo.

10 Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanz ania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

11 Madagascar and Seychelles did not sign the Protocol

12 The document was ratified by South Africa, Botswana, Mozambique, Swaziland and Zambia.