Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Computer Journal

On-line version ISSN 2313-7835

Print version ISSN 1015-7999

SACJ vol.34 n.2 Grahamstown Dec. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18489/sacj.v34i2.1097

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Investigating the use of mobile communication technology in professional development: a connectivist approach

Patrick MutangaI; Abueng MolotsiII

IHarare Institute of Technology. pmutanga@hit.ac.zw

IIUniversity of South Africa. molotar@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In most universities in Zimbabwe, the educators do not possess professional teaching qualifications. Most educators resist institutional interventions aimed at equipping them with appropriate pedagogical skills due to the rigidity of intervention programmes. The advent of mobile communication technology brought various social media platforms that enhance communication. This study was aimed at investigating the experiences of university educators during the use of WhatsApp Messenger to learn about inquiry-based pedagogy as a professional development course. Nine university educators who had no prior training in pedagogy were purposely selected from three Zimbabwean universities. Semi-structured interviews and a focus group discussion were conducted to gather empirical data. The connectivism theoretical framework was used to understand the phenomenon under study. A thematic network analysis was deemed suitable for this study. The findings showed that by learning about inquiry-based pedagogy (IBP) on the WhatsApp Messenger platform, the university educators managed to transform their professional identities as well as improve their pedagogical practices. It may be concluded that WhatsApp Messenger offers a conducive platform for educators' professional development. It is recommended that universities use WhatsApp Messenger for professional development through online communities of practice.

CATEGORIES: • Applied Computing ~ Education, e-Learning

Keywords: Information and communications technology, online communities of practice, pedagogy, professional development, WhatsApp Messenger

1 INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM STATEMENT

The professional development of university educators has become a frequent topic of discussion in higher education and training institutions. Unlike in the past few decades, when an individual simply needed an advanced academic qualification to be enrolled as an educator at a university, the current educational dispensation is moving towards the professionalisation of university education. However, research has shown that university educators shun professional development courses, as they place an extra burden on their work routines (Chabaya, 2015). Moreover, most of them may be highly qualified in their own areas of expertise and they tend to look down upon professional development courses.

For most universities, professional development has been presented in the form of short courses through workshops and seminars (Green, 2015). However, these have been proven to be ineffective in providing long-lasting solutions to university educators' professional needs. Research has shown that for a professional development programme to be effective, it must be sustainable, coherent, content-focused and participatory, and it should promote active learning (Whitworth & Chiu, 2015). The programme should also allow collaboration with educators from other institutions to promote the cross pollination of ideas and the sharing of experiences (Leibowitz et al., 2014). Professional development takes many forms. These include the inculcation of the ethos and values of the university education profession; acquisition of skills of teaching profession (Gonzalez & Skultety, 2018).

Research has shown that professional development for university educators is a problematic issue as very few university educators possess pedagogical practices (Leavitt et al., 2012). Current attempts at university educator professional development have not been successful due to the rigid, traditional classroom-based setup, where university educators are required to take formal pedagogical lessons that do not specifically attend to their needs (Donnelly, 2016). Educators have resisted such formal settings, as they impose on them 'learner' tags, which means they continue to use ineffective instructional approaches that do not improve their students' problem-solving abilities (Shava, 2015). At some universities, professional development is done in the once off ad-hoc and unsystematic seminars, which have been proven to be ineffective due their lack of cohesiveness and inability to impart long-lasting changes to university educators' pedagogical practices (Jeannin, 2016). These challenges mean that facilitators of professional development must design new, flexible ways that are effective in imparting pedagogical skills to university educators.

Developments in online communities have brought about new ways by which facilitators of professional development can disseminate pedagogical knowledge (Reeves et al., 2015). Facilitators of professional development and educators now have access to mobile communication devices that host various social media. One such social medium platform that has gained widespread use is WhatsApp Messenger (Yin, 2016).

Through WhatsApp Messenger, university educators can communicate and share information about their pedagogical practices online in groups. It was therefore the intention of this study to investigate the experience of university educators who participated in an online professional development course hosted on the WhatsApp Messenger platform.

2 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

It has been proven that good educators impact positively on students' performance, both during their years at university (Larsen-Freeman, 2013) and during their life after university. Higher education institutions as well as professional development facilitators are therefore required to provide conducive learning environments to university students so that they can master specific instructional competencies (Yin, 2016). Other than gaining formal qualifications, university educators need to be involved in their own development through collaborating with peers using social networking (Lu & Churchill, 2014).

In the current study, 'university educator professional development' refers to those processes or initiatives that aim to equip university educators with pedagogical approaches that help students to enhance their knowledge generation and problem-solving skills. IBP is one teaching approach that has proven efficient in enabling students to develop such skills.

IBP is an approach to teaching that came about as a response to traditional methods such as rote learning and direct learning (Ernst et al., 2017). It is an approach that places the student at the centre of the learning process, with educators performing the roles of facilitators (Kotsari & Smyrnaiou, 2017). Students are expected to take ownership of the learning process (Fine & Desmond, 2015). They will be required to use their prior knowledge in generating new knowledge while the university educator will be acting as a facilitator or guide, asking students questions that prompt them to engage in higher-order thinking and guiding them through the learning process (Larsen-Freeman, 2013). This helps students to widen their knowledge base through engagements with other students. To enable university educators to acquire such facilitation skills, it is necessary for them to engage in professional development programmes. This means that university educators have to become learners in the professional development process.

Considering the importance of professional development initiatives to the development of university educator effectiveness, it is important to consider the 'educator-as-learner' approach to professional development. This means that when university educators participate in professional development programmes, they become 'learners'; they will have to understand the meaning of what they learn in the professional development context before they will be able to apply it in their work (Larsen-Freeman, 2013). It is not automatic that university educators would apply what they have learnt to their teaching, but transformations that occur within the educators themselves will influence them to apply their learning (Larsen-Freeman, 2013). It is therefore important to put university educators at the centre of the learning process so that they actively acquire knowledge about how to teach.

Current university educator professional development programmes need to be designed in such a way that they impart relevant pedagogical skills. For such programmes to be effective, they should be offered in flexible environments that do not disrupt the educators' work schedules. Online learning environments are ideal for university educator professional development (Lu & Churchill, 2014). Such environments eliminate the need for university educators to enrol in traditional professional development classes, which have been a major reason for resentment of professional development programmes (Suwaed & Rahouma, 2015).

2.1 Online communities of practice: WhatsApp Messenger

Research has shown that there has been growth in the use of mobile communication technology to support online professional learning communities (Rambe & Bere, 2013). Participants in an online environment are motivated to take part in collaborative learning activities (Mercier & Higgins, 2013). These online professional learning communities can transcend national borders and enable university educators with the same interests to collaborate and share information (Rambe & Bere, 2013). Interactions within online environments evidenced joint participation, improve joint attention and promote task-focused conversation (Fine & Desmond, 2015). Social media applications embedded into mobile communication devices make communication cheaper and more convenient. WhatsApp Messenger is one such platform that has found widespread use among professionals.

WhatsApp Messenger facilitates individuals' 'social presence' (Yin, 2016) in online community of practices (CoPs), which is pertinent to enhancing their participation. When individuals have discussions in an online environment through mobile communication technology, their social networking skills and professional development improve (Lu & Churchill, 2014). WhatsApp Messenger contributes to online professional development approaches and removes social hierarchies, which can be barrier to face-to-face online communication (Giordano et al., 2015). While studies have shown that WhatsApp Messenger is an effective communication tool in education, little or no research has been carried out on its use in university educators' professional development.

3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The ever-increasing use of technological devices as an educational tool has changed the learning landscape (Higgins et al., 2012). The development of technological devices has brought forth gaps in the traditional approach of teaching and the need for new modes of delivery of knowledge to keep up with new developments. The connectivism theory best suited this study as it accommodates learning in the digital age (Siemens, 2004). It highlights the interactions that occur within networks as key to sharing knowledge to expand technological skills (Saykili, 2019). Ideally, it's perspectives are deemed relevant to understand the challenges of 21st century digital learning solutions to those gaps (Ozturk, 2015).

Research has shown that learning no longer occurs only within an individual's domain, but across networks (Gonzalez & Skultety, 2018). In essence, these networks enable individuals to learn through acquiring diverse opinions about certain issues. Through these interactions, students are enabled to create new knowledge and share information with peers (Duke et al., 2013). The ability to tap into the network interactions instantly enables individuals to access relevant information with ease. Connectivism recognises knowledge creation as a shared responsibility. This is the knowledge that emanates from the experiences and interactions that take place within a network.

In the context of the current study, connectivism theory recognises that an individual cannot experience everything personally but has to rely on sharing experiences with others. As such, the university educators in this study could obtain relevant information by tapping into the network facilitated by the WhatsApp Messenger platform. They had to form information networks that were driven by common professional interests. They interacted and shared information as they discussed IBP on the WhatsApp Messenger platform. As knowledge is distributed across networks through connections, learning depends on individuals' ability to construct networks and to traverse them (Aldahdouh et al., 2015). A network consists of two or more nodes, joined to one another by connections or relationships (see Figure 1).

A, B, C and D represent nodes that are connected by six relationships. The nodes can represent any source of knowledge (Aldahdouh et al., 2015), such as individual university educators, the group facilitator, websites where information can be obtained and in certain cases books and other artefacts that can act as sources of knowledge. Ideally, learning takes place when connections are made between various nodes of information. The strength of the nodes depends on the information generated and the number of people who navigate a particular node (Aldahdouh et al., 2015).

Undoubtedly, technology is changing how learning can be done in and beyond classroom walls. Rather than learning from educators and hardcopy study materials, smartphones serve as hubs of information for the 21st century teaching and learning environment. WhatsApp Messenger has broken many barriers to knowledge creation and dissemination, as it can connect people of various backgrounds. The aim of this study was to investigate the experiences of university educators during the use of WhatsApp Messenger to learn about IBP as a professional development course. This study was drawn from the major study by (Mutanga, 2020) which was investigating the use of mobile communication technology in professional identity development.

4 METHODOLOGY

This empirical study was conducted based on an interpretive paradigm stance. This paradigm was deemed relevant for this study, as this study was aimed at investigating the experiences of university educators during the use of WhatsApp Messenger to learn about inquiry-based pedagogy as a professional development course. A qualitative research method was adopted in this study with the intention to construct knowledge using interpretive, naturalistic approaches (Thanh & Thanh, 2015). A case study was involved to acquire an in-depth examination of the participants and their related contextual conditions (Thanh & Thanh, 2015). The case study in the current study was a group of university educators who learnt about IBP on the WhatsApp Messenger platform and were regarded as an embedded unit.

4.1 Target group and sampling

Atargetpopulation refers to a group ofindividuals who forms the sample ofthe study(Thanh & Thanh, 2015). Nine university educators were purposefully sampled to participate in the study. In essence, purposive sampling enables the selection of the participants with rich information to gain a deeper understanding of the issues under investigation (Thanh & Thanh, 2015). In the context of this research, university educators without prior pedagogical training were requested to participate, the assumption was that they lacked IBP skills. They were, however, knowledgeable about using the WhatsApp Messenger platform.

4.2 Data collection instruments and procedure

Data collection was done using semi-structured interviews and a focus group discussion. According to Jamshed (2014) the semi structured interviews are used by the interviewers with an insight of a study. Hence it allows for in-depth probing during the interview's sessions (Alshen-qeeti, 2014). The open-ended questions checklists were asked to elicit nine university educators' narratives about their experiences in using WhatsApp Messenger to learn about IBP.

Focus group discussions is defined as interviewing a group of participants who have similar backgrounds within a discussion session (Moore et al., 2015; Nyumba et al., 2018). The focus group discussions in general help to clarify and augment shared information within a group which may not be obtained by interviewing individuals (Thanh & Thanh, 2015). In this study, only six educators participated in the focus group discussions after the completion of the WhatsApp Messenger-based IBP course. The purpose of the focus group discussions was to enhance semi structured gathered data that might have been missed. The collection of data was done in three phases, as discussed in the following subsections.

4.2.1 Phase 1: Establishing the educators' baseline knowledge about IBP

Semi-structured interviews were employed to establish the participants' baseline knowledge about the IBP approach.

During the first phase, a group of nine university educators was enrolled in a WhatsApp Messenger group as an online CoP created to house the participants. The purpose of the group was to learn about IBP as a teaching approach. The discussion was tracked throughout the learning process by following the discussions on the WhatsApp Messenger platform.

4.2.2 Phase 2: Learning about IBP

After eight weeks of learning about IBP on the WhatsApp Messenger platform, a focus groups discussion was held with the participants to determine their experiences in terms of learning about the IBP approach. The intervention phase followed the focus group discussion, which explored the participants' experiences of learning about the IBP approach using WhatsApp Messenger.

4.2.3 Phase 3: Intervention

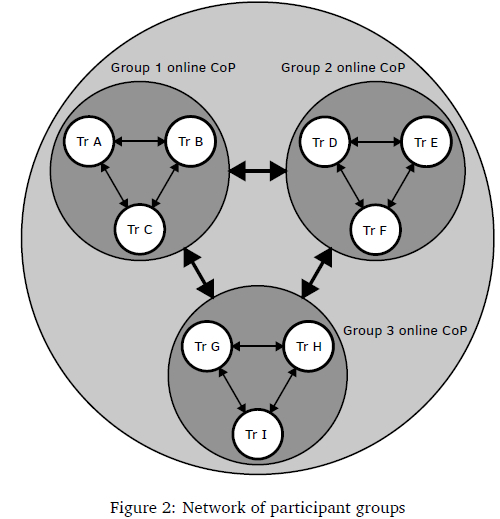

During the intervention phase, three WhatsApp Messenger CoPs were created, which extended what was started in Phase 1, but with participants divided according to their respective institutions. The purpose of creating these groups was to discuss what they have learned about the IBP approach. The connectivism theory lens guided the formation of the CoPs, as the focus was on creating knowledge that emanates from the experiences and interactions that take place within the network. The creation of the CoPs on WhatsApp Messenger was based on the following objectives:

• Demonstrate an understanding of the philosophy behind IBP

• Analyse elements of the IBP instructional model

• Discuss strategies and tools for implementing IBP

• Demonstrate an understanding of the benefits and weaknesses of IBP

• Develop learning guides to use when implementing IBP in the classroom

The CoPs were instructed to search for information about the constructivism philosophy, which forms the basis of the IBP approach. This was done to ensure that the participants understood the philosophical underpinnings of the IBP teaching approach to have clear, relevant, deep, accurate and consistent knowledge about the approach (Maaft & Artigue, 2013). After researching information about the IBP approach, the participants were instructed to discuss the strategies and tools for implementing IBP. The findings were discussed within their CoPs. Drawing from their deliberations it was evident that they understood IBP. The analysis also covered the benefits and weaknesses of the use of IBP. The participants expressed their views within the platform as CoPs and the views were content analysed for themes. The views clearly indicated that participants had developed a better understanding of IBP.

The three WhatsApp Messenger groups collaborated online. The intended outcome at this stage was focused more on their interaction regarding the IBP approach. Each group acted as a CoP, as shown in Figure 2.

Each CoP was tasked to select a topic of their own choice and discuss how they would use IBP to teach the topic. They were asked to produce lesson guides and share them on the main WhatsApp Messenger so that other groups could discuss them and critique them. The intervention stage was followed by a post-intervention focus group discussion. The question that guided the focus group discussion was: "How do the pedagogical practices of university educators change after learning about IBP through WhatsApp Messenger?"

Six participants participated in the focus group discussion after they undertook the Whats-App Messenger-based IBP approach to learning. The other three participants could not attend the focus group discussion because of work-related issues. The discussion lasted for 90 minutes. The purpose of the discussion was to gain an understanding of any changes that had occurred in their use of the WhatsApp Messenger-based IBP approach. The open-ended questions were specifically tailored to identify any changes to the indicators of the IBP approach discussed in Phase 1.

4.3 Data analysis

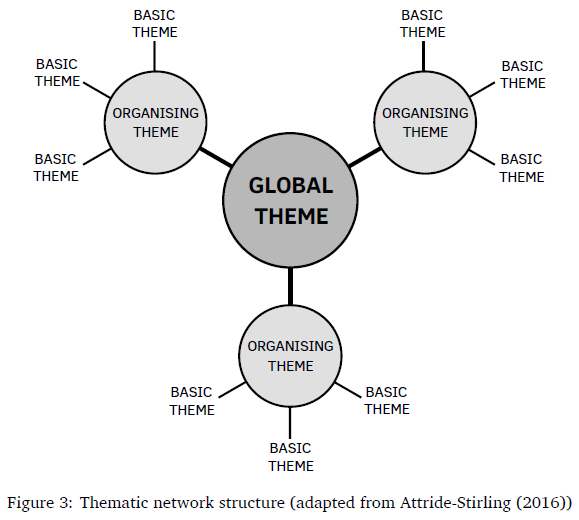

Data were analysed using thematic network analysis, which presents data in a web-like network. Through reading and re-reading the data three different levels emerged: basic themes, organising themes and global themes (Attride-Stirling, 2016; Creswell, 2014). The basic themes represented the lowest-order meanings that could be extracted from the textual data. Several related basic themes were then grouped together to come up with organising themes. The organising themes summarised the main assumptions of the basic themes. They were further grouped to form superordinate global themes that covered all the issues covered in all the data. The thematic network is presented in a web-like structure in Figure 3.

5 ETHICAL ISSUES

During this research, all ethical issues that relate to research that involves human participants were observed. All the university educators and the universities where they taught were informed about the purpose and methods of the research. They were also made aware of any risks that could be associated with participating in the research. The participants were given this information in written format, and they signed consent forms. Non-disclosure of participants' names and their universities was maintained so as to maintain confidentiality.

Participation in the research was voluntary. The participants were informed that they had the right to refuse to participate in the research and that they could withdraw from the process at any stage. No participant was coerced to participate in the research. The study was carried out in a way that protected the professional integrity of the research design, the generation and analysis of data as well as the publication of the results. All works, drawings and ideas that were not originated were referenced. The individual university educators were given codes to maintain anonymity. They are identified as educators A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H and I.

6 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

6.1 Participants' initial professional competency

When asked about their professional competency in delivering their content, the participants' responses showed that some paid no attention to teaching methods, some believed students were passive recipients of knowledge, some were opposed to the use of ICT in teaching, some believed that the educator was supposed to be the purveyor of knowledge and most of them lacked an understanding of the IBP approach (refer to Figure 4).

As shown by the response from the semi-structured interviews the educators were mainly self-centred in the teaching approach. This approach is usually used by educators who do not believe in their students' ability to generate their own knowledge (Ernst et al., 2017). The educators did not give students the opportunity to actively participate in their learning. In some instances, the students would be provided with a soft copy of the lecture notes via email or on their flash memory sticks. The educators seemed to spoon-feed their students. As Educator I from University C said:

I usually give lectures to the students. I explain concepts, then give them notes and hand-outs. This will help them to understand.

The participants' views on pedagogical practices were that their role had to be more of providing students with study materials (Cho & Rathbun, 2013) and leading them to achieve the intended outcomes. For them, students have to be passive recipients of information in all learning processes. In this approach, the main goal of teaching was to enable students to pass examinations.

The participants were unfamiliar with the IBP approach however, the word 'inquiry' assisted them to understand the meaning thereof. Unfamiliarity with IBP usage caused them to believe that it would be impossible to teach using IBP. Educator H from University C said:

I don't know much about that approach. It's a bit difficult to implement, I think. As you are aware ... with the type of students ... I don't really know. Besides, there is the issue of time also ...

The participants were also against much reliance on the use of ICTs by students. They believed that if student use ICTs, the educators would be regarded as less 'important' sources of information. Educator C from University A said:

With the availability of computers and [the] internet, students were developing a tendency of absconding lessons, believing that they could always get the information from the internet.

This participant was primarily interested in how information was disseminated to students without using ICT. He believed that he was the only source of information. According to Lodhi and Ghias (2019), there is a tendency among educators without professional training to believe that they are the only sources of information. This educator felt that his role as the source of information was under threat from the internet, so he would use attendance of lectures as a bait to students to pass examinations. He would guide students on how to prepare and pass examinations. In other words, for students to succeed, they had to give attendance to lectures first preference.

6.2 Change in professional competency after the WhatsApp Messenger-based course

After learning the course, the participants realised the need to use different teaching approaches; they came to understand both roles of the educator and the student in the teaching and learning process. Hence, they appreciated the use of ICT to augment the learning process (refer to Figure 5).

As indicated by the result from the interviews after the WhatsApp Messenger IBP course, the educators' perceptions of the role of pedagogical practices in student learning changed significantly. They were made to understand the acquisition of the appropriate pedagogical skills so as to reach students (Rambe & Bere, 2013). Their previous belief that anyone could teach with lower academic qualifications than them changed. Educator E from University B explained as follows:

I now fully appreciate the importance of pedagogical skills. I used to believe in doing everything for the students ... I would look for information, give them notes and everything! The course helped me a lot. The good thing is that it was done over the phone. You know ... a phone is something that you carry with you everywhere. Even when I travelled abroad during the course, I could still interact with others . I could participate at any time. In addition, I could go on the internet to research more about the IBP approach and other teaching approaches.

From this response it can be concluded that the educator was now aware of the weaknesses that were associated with his previous teaching approaches. The WhatsApp Messenger based IBP course had managed to transform the way he viewed his role as an educator. Where he would previously play a more active role than the students, he then appreciated that it was the students who were supposed to be more active in the learning process. The WhatsApp Messenger platform gave him an environment where he shared experience with his peers resulting in him becoming knowledgeable about using different pedagogical practices in teaching and learning.

Educator E also managed to identify the strengths of WhatsApp Messenger as the networking tool. He managed to travel abroad during the course and still remain part of the CoP. It was also noted from the interviews that participants in WhatsApp Messenger based course managed to use their interaction to go beyond discussing just about IBP only. They ended up discussing about other teaching methods as well. According to Suwaed and Rahouma (2015) going beyond a certain task to know more about a profession is a sign of positive professional development. This shows that the participants found WhatsApp Messenger to be a flexible and enriching platform where they could improve their pedagogical knowledge and skills. There was a general agreement among the educators that WhatsApp Messenger was an effective tool for pedagogical content delivery. This is consistent with the connectivism theory which supports the flexibility and effectiveness of online learning environments (Siemens, 2004). Educator C from University A said:

I have actually started using it with my students. I do believe it's an amazing innovation. It just needs proper guidance so as to maintain focus.

The comment marked a change from the educators' initial perception that ICT use promotes truancy and plagiarism. His initial belief was that students who were supposed to attend face-to-face lessons was to receive notes and examination related material. His experience in the WhatsApp Messenger base course had, however taught him that students could create their own knowledge when they were given the necessary learning environment. According to Fine and Desmond (2015) educators who have undergone professional development tend to be more student centered in their teaching approaches.

There was a feeling among the educators that advancement in technology was threatening their role as information disseminators. They felt that the role of the educator was slowly diminishing. According to Educator A from University A:

This technology issue has the potential of replacing teachers in universities . now the students can almost do without teachers in universities. Some students believe they understand better on the Internet.

This educator's response showed that he feared that his profession was under threat from technology. He agreed that technology had the potential to avail information to students in a more flexible way than the educators in the traditional classroom setup.

The educators were of the opinion that the experience that they gained in WhatsApp Messenger-based course made them better educators who could help students apply their knowledge in real life situations. Educator E from University B explained as follows:

I believe . I am in a much better position now to assist students with applying their knowledge to real-life situations. You know what this IBP issue does . as a lecturer you need to be very good at it. I guess it is a skill that develops with time. So, when you teach using IBP you are not only developing the students' knowledge creation and problem-solving skills . You will also be developing your own teaching skills. So, it is a mutually beneficial approach. In the end, the experience that you earn as you teach will help you become a better facilitator, and you can assist the students even beyond the classroom.

It is important to note that the educator recognized the need for further professional development on his part. According to Chabaya (2015), the realisation of a positive self-image is a product of affective professional development. The WhatsApp Messenger-based IBP course had helped the educator to realise that knowledge does not only exist in the educator, but it takes the efforts of both the student and educator to create it (Yin, 2016).

The educators were of the opinion that the experience that they gained in the WhatsApp Messenger-based course made them better educators who could help students apply their knowledge in a real-life situation. Educator E from University B said:

If you look at the way changes are taking place in the education sector, you can see that they are now taking place at a faster rate. They are also taking place from many fronts . there is the issue of new teaching approaches, the issue of technology . the issue of aligning the curriculum to industry need . so many issues! Personally, I believe the acquisition of teaching skills go a long way to help improve one's ability to respond to these issues. I mean, I am now in a much better position to respond to educational change than I was a few months ago.

From this response, it was apparent that the educator had transformed the way in which he viewed his role in the teaching profession. According to Kennedy (2016) effective professional development results in a change in educators' views about their roles in education. Initially this educator appeared not interested in dealing with educational change but the WhatsApp Messenger-based IBP course transformed him.

The results of the study showed that the WhatsApp Messenger platform has a huge potential in solving the challenges associated with the professional development of university educators. Additionally, by making use of social networking applications such as WhatsApp Messenger universities can be able to provide professional development programmes to their teaching staff in a flexible manner which does not cause any disruptions to their daily teaching routines. The use of WhatsApp Messenger is supported by the theory of connectivism which places emphasis on the importance of digital connections in learning (Siemens, 2004).

The university educators managed to engage in meaningful discussions on their mobile phones. The WhatsApp Messenger platform eliminated the barriers associated with traditional learning environments such as the classroom (Cho & Rathbun, 2013). These barriers discouraged the participation of university educators in professional development courses. The anonymity of the online professional learning community offered a chance for individual educators to express their own views as they discussed and shared ideas about IBP. This study contributes to new knowledge about new contemporary, innovative social media technologies that educators may use as a new way of delivering content.

7 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The study managed to illuminate some of the challenges regarding the professional development of the university educators in Zimbabwe and how ICT can be used to tackle them. Because of their lack of training in pedagogy the university educators showed lack of competency in pedagogical approaches. This study investigated the experiences of university educators during the use of WhatsApp Messenger to learn about inquiry-based pedagogy as a professional development course. From the results of this study, it can be concluded that WhatsApp Messenger is an effective communication tool that can be used for online professional development. It provides facilitators of university education professional development with a chance to design and implement flexible and innovative courses that can be undertaken by university educators without disrupting their daily work commitments. Universities are recommended to design online professional development IBP learning that can be conducted on the popularity of the WhatsApp Messenger platform. Such IBP learning must be tailor-made to suit the professional development needs of university educators in specific areas of expertise. The connectivism theory in this study provided vital information about how sharing of information using WhatsApp Messenger can create new delivery of content opportunities for university educators.

References

Aldahdouh, A. A., Osório, A. J., & Caires, S. (2015). Understanding knowledge network, learning and connectivism. International journal of instructional technology and distance learning, 12(10), 3-21. https://www.itdl.org/Journal/Oct_15/Oct15.pdf [ Links ]

Alshenqeeti, H. (2014). Interviewing as a data collection method: A critical review. English Linguistics Research, 3(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.5430/ELR.V3N1P39 [ Links ]

Attride-Stirling, J. (2016). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385-405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307 [ Links ]

Chabaya, R. A. (2015). Academic staff development in higher education institutions : A case study of Zimbabwe state universities (Doctor of Education). University of South Africa. Pretoria. https://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/21930

Cho, M.-H., & Rathbun, G. (2013). Implementing teacher-centred online teacher professional development (oTPD) programme in higher education: A case study. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 50(2), 144-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.760868 [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Donnelly, R. (2016). Supporting the professional development of teachers in higher education [Resource Paper, Technological University Dublin]. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ltcoth/34/

Duke, B., Harper, G., & Johnston, M. R. (2013). Connectivism as a digital age learning theory. The International HETL Review, 4-13.

Ernst, D. C., Hodge, A., & Yoshinobu, S. (2017). What is inquiry-based learning? Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 64, 570-574. https://doi.org/10.1090/NOTI1536 [ Links ]

Fine, M., & Desmond, L. (2015). Inquiry base learning: Preparing young learners for the demands of the 21st century. Educators Voice, 8, 2-11. https://www.nysut.org/~/media/files/nysut/resources/2015/april/1_edvoicevii_ch1.pdf [ Links ]

Giordano, V., Koch, H. A., Mendes, C. H., Bergamin, A., de Souza, F. S., & do Amaral, N. P. (2015). WhatsApp Messenger is useful and reproducible in the assessment of tibial plateau fractures: Inter- and intra-observer agreement study. International journal of medical informatics, 84(2), 141-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/JJJMEDINF.2014.11.002 [ Links ]

Gonzalez, G., & Skultety, L. (2018). Teacher learning in a combined professional development intervention. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71, 341-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TATE.2018.02.003 [ Links ]

Green, A. (2015). Teacher induction, identity, and pedagogy: Hearing the voices of mature early career teachers from an industry background. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 43(1), 49-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2014.905671 [ Links ]

Higgins, S., Mercier, E., Burd, L., & Joyce-Gibbons, A. (2012). Multi-touch tables and collaborative learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(6), 1041-1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-8535.2011.01259.X [ Links ]

Jamshed, S. (2014). Qualitative research method - interviewing and observation. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy, 5(4), 87. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-0105.141942 [ Links ]

Jeannin, L. M. (2016). Professional development needs of faculty members in an international university in Thailand (Doctor of Education (Ed.D.)). Walden University. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/2187/

Kennedy, M. M. (2016). How does professional development improve teaching? Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 945-980. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626800 [ Links ]

Kotsari, C., & Smyrnaiou, Z. (2017). Inquiry based learning and meaning generation through modelling on geometrical optics in a constructionist environment. European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 5(1), 14-27. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1129981 [ Links ]

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2013). Transfer of learning transformed. Language Learning, 63(SUPPL. 1), 107-129. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-9922.2012.00740.X [ Links ]

Leavitt, K., Reynolds, S. J., Barnes, C. M., Schilpzand, P., & Hannah, S. T. (2012). Different hats, different obligations: Plural occupational identities and situated moral judgments. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1316-1333. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.1023 [ Links ]

Leibowitz, B., Bozalek, V., & Sipuka, P. (2014). The professional development of academics with regard to the teaching role -- an inter-institutional investigation [Presented at the 8th UKZN conference in teaching and learning in higher education]. https://utlo.ukzn.ac.za/pastconferences/8th-tl-conference/

Lodhi, I. S., & Ghias, F. (2019). Professional development of the university teachers: An insight into the problem areas. Bulletin of Education and Research, 41(2), 207-214. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1229451 [ Links ]

Lu, J., & Churchill, D. (2014). Using social networking environments to support collaborative learning in a Chinese university class: Interaction pattern and influencing factors. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 30(4), 472-486. https://doi.org/10.14742/AJET.655 [ Links ]

Maaft, K., & Artigue, M. (2013). Implementation of inquiry-based learning in day-to-day teaching: A synthesis. ZDM - Mathematics Education, 45, 779-795. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11858-013-0528-0 [ Links ]

Mercier, E. M., & Higgins, S. E. (2013). Collaborative learning with multi-touch technology: Developing adaptive expertise. Learning and Instruction, 25, 13-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LEARNINSTRUC.2012.10.004 [ Links ]

Moore, T., McKee, K., & McCoughlin, P. (2015). Online focus groups and qualitative research in the social sciences: Their merits and limitations in a study of housing and youth. People, Place and Policy Online, 9(1), 17-28. https://doi.org/10.3351/PPP.0009.0001.0002 [ Links ]

Mutanga, P. (2020). The use ofmobile communication technology in professional identity development: A case of using WhatsApp Messenger to teach inquiry-based pedagogy to university chemistry teachers (Doctor of Philosophy). University of South Africa. Pretoria. http://hdl.handle.net/10500/27295

Nyumba, T. O., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., & Mukherjee, N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(1), 20-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860 [ Links ]

Ozturk, H. T. (2015). Examining value change in MOOCs in the scope of connectivism and open educational resources movement. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(5), 119-143. https://doi.org/10.19173/IRRODL.V16I5.2027 [ Links ]

Rambe, P., & Bere, A. (2013). Using mobile instant messaging to leverage learner participation and transform pedagogy at a South African university of technology. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(4), 544-561. https://doi.org/10.1111/BJET.12057 [ Links ]

Reeves, J., Karp, J., Mendez, G., Alemany, J., McDermott, M., Borror, J., Capo, B., & Schlosser, C. (2015). Building an online learning community for technology integration in education. FDLA Journal, 2(1). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/fdla-journal/vol2/iss1/3 [ Links ]

Saykili, A. (2019). Higher education in the digital age: The impact of digital connective technologies. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 2(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.31681/JETOL.516971 [ Links ]

Shava, G. N. (2015). Professional development, a major stategy for higher education student success: Experiences from a university in zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Journal of Science and Technology, 10, 11-25. http://journals.nust.ac.zw/index.php/zjst/article/view/60 [ Links ]

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal ofInstructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2, 3-10. [ Links ]

Suwaed, H., & Rahouma, W. (2015). A new vision of professional development for university teachers in Libya "It's not an event, it is a process". Universal Journal of Educational Research, 3(10), 691-696. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2015.031005 [ Links ]

Thanh, N. C., & Thanh, T. T. L. (2015). The interconnection between interpretivist paradigm and qualitative methods in education. American Journal of Educational Science, 1(2). http://www.aiscience.org/journal/paperInfo/ajes?paperId=672 [ Links ]

Whitworth, B. A., & Chiu, J. L. (2015). Professional development and teacher change: The missing leadership link. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26(2), 121-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-014-9411-2 [ Links ]

Yin, L. C. (2016). Adoption of WhatsApp instant messaging among students in Ipoh higher education institutions (Master of Education). Wawasan Open University.

Received: 31 March 2022

Accepted: 20 July 2022

Available online: 5 December 2022