Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning

versão On-line ISSN 2310-7103

CRISTAL vol.11 no.1 Cape Town 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v11i1.618

ARTICLES

Doctor who? Developing a translation device for exploring successful doctoral being and becoming

Sherran ClarenceI, #; Martina van HeerdenII

INottingham Trent University and Rhodes University

IIUniversity of the Western Cape

ABSTRACT

Doctoral training and education tends to focus on how to research and write a thesis, which can take many forms. However, a thesis is not the only valued outcome of a doctorate: the emerging Doctor is important too. Being and becoming a Doctor implies identity work and engaging affective dimensions of researcher development alongside researching and writing a thesis. These are not always explicit in doctoral education, though. Thus, we contend that their role in researcher development needs to be named, described, and understood. In this paper we use Constellations from Legitimation Code Theory to make visible two valued doctoral attributes and dispositions as exemplars. We have used published papers in the field of doctoral studies as data. Within increasingly diverse doctoral student cohorts, it is important to actively foreground the development of valued affective dispositions through doctoral education to enable more candidates to achieve success in their doctorates.

Keywords: attributes, axiology, doctoral education, equity, inclusion, research culture

Introduction

When we think of a successful doctorate, what usually comes to mind first? The thesis1, probably - the research itself and the original contribution to knowledge that it is making through the work of the researcher(s) involved. We think about knowledge - knowledge production and the impact of that knowledge on research and perhaps also practice, especially if we are considering professional and practice-based doctorates (for example, in design, fine art, and education). If we think of the researcher, it may be primarily as the producer or creator of this knowledge, as the vehicle for 'writing it up' and getting it out into the world. This is not to say that the field of doctoral education does not think or care about the development of doctoral candidates; there is a body of research globally on aspects of being a successful doctoral candidate and different dimensions of this, including emotional and mental wellbeing (see Aitchison & Mowbray, 2013; Carter, et al., 2013; Doloriert, et al., 2012; Mewburn, 2011). Rather, it may be that the overt development of the doctoral candidate as a person is peripheral rather than central to supervision. Combined with pressures across the disciplines in many higher education contexts (such as the UK, South Africa, and Australia) - those in which dyadic or one-on-one supervision is common as well as those with team and cohort supervision models - to attract, retain, and graduate increasing numbers of doctorate-holders, doctoral education in these disciplines may face challenges in supporting both supervisors and candidates in the tricky work of personal and professional development, which may be subsumed by a focus on 'getting through' . Supervisors working alone with their candidates cannot share the load with others, and time pressures on supervision and doctoral study (see Carter, et al., 2017; Manathunga, 2019) may mean that wider conversations about the 'being and becoming' inherent in doctoral study are neglected or less possible.

Yet, the doctorate is by nature transformative (Barnacle, 2005). As Barnacle and Mewburn (2010: 433, emphasis added) point out '[c]ompleting a PhD does not just involve becoming an expert in a particular topic area, but comprises a transformation of identity, that of becoming a scholar or researcher' . In becoming a scholar, candidates must navigate multiple identities, both personal and professional, while crossing many thresholds. Some of these thresholds are related to the doing and writing of the research itself, such as argumentation, theorising, and analysis (Kiley & Wisker, 2009). But, as we will show in this paper, there are other kinds of thresholds to cross that are transformative of the self, the person becoming a 'Dr' , and these are as important to be aware of in all their complexity. These thresholds speak to the different dimensions of doing a doctorate we will expand on later: the product, the process, and the person, although we argue that the person needs to be given specific attention. This is more pertinent now than ever as many universities are committed to enacting more inclusive doctoral education and supervision, thereby creating wider success for different kinds of candidates, such as those previously excluded from and under-represented in doctoral study (see EDEPI, n.d; SJQinHE, n.d).

Part of the transformative nature of becoming a doctor is displaying 'doctorateness' (Trafford & Leshem, 2008). Yazdani and Shokooh (2018: 42, emphasis added), drawing on the research of Trafford and Leshem (2008) and others, define doctorateness as

A personal quality, that following a developmental and transformative apprenticeship process, results in the formation of an independent scholar with a certain identity and level of competence and creation of an original contribution, which extend knowledge through scholarship and receipt of the highest academic degree and culminates stewardship of the discipline.

Doctorateness is therefore an implicit part of completing the doctorate and is central to what examiners and supervisors look for in a thesis (Trafford & Leshem, 2009). This personal quality, though, is more closely connected in the literatures to the product and the process, which are more overtly about knowledge and less about the 'knower' or researcher. We therefore contend that, to create a more holistic sense of doctorateness with a clear focus on the person driving the process and creating the product, we need to pay greater attention to the affective dimensions of doctoral work, which are key to being and becoming a 'Dr' .

However, what is notable in reading the field is how many of the markers of being a successful doctoral student - attributes, behaviours, values, and personal characteristics - are not explicitly defined, inferring an assumption of shared understandings or taken-for-granted meanings. For instance, terms like 'independent' and 'confident' are often used when describing the 'ideal PhD student' (see for example Aitchison, et al., 2012; Cutri, et al., 2021; McAlpine, et al., 2012). However, if you are paying attention to these issues, as we are in this paper, you may begin to wonder if 'confident' and 'independent' have the same meaning or imply the same behaviours or values everywhere they are mentioned, across all disciplines and fields of study and in different national and institutional contexts. We suspect that they do not, but it is not always possible to work out the exact meanings or any differences in meaning in all the papers in which these characteristics of candidates are mentioned as being necessary or desirable for doctoral success. This then raises further questions this paper will address:

1. What do these different attributes imply in terms of doctoral being and becoming, and student behaviours and values?

2. Can we find a way to 'see' all the meanings and work out whether and how these are communicated to candidates and made part of deliberate or conscious doctoral education?

We are suggesting here that what it means to be 'confident' in the context of doctoral research may have multiple meanings across and even within specific disciplinary, departmental, and institutional contexts, and that what it takes to develop these attributes may involve being able to see and understand the different meanings of these concepts or behaviours. Specifically, we have to consider what this would mean for doctoral supervision and education, especially but not only in disciplines or fields where supervisors and candidates work away from larger research groups or communities, and where time is pressured and condensed. We argue in this paper for the use of a theoretical tool drawn from Legitimation Code Theory (LCT) - axiological semantic density and the building of constellations - to not only surface the dominant attributes, values and behaviours referred to in the literatures, but further to explore the different meanings implied in these references. We hope that this will provide evidence for both the value ascribed to affective aspects of being and becoming a successful doctoral student and the multiple possible meanings embedded within these attributes, dispositions, and ways of being. Ultimately, we hope that those involved in providing researcher development and support, including supervisors, can use these insights to begin to reflect on their own meanings and assumptions and how these impact on the doctoral candidates in their context.

Doctoral education: Three dimensions of doing a 'PhD'

There are three interlinked dimensions to undertaking postgraduate study: the product of the research (the thesis), the process of designing, conducting, and writing about the research, and the person or people involved in the project (the candidate, primarily, but also the research supervisors). Research has observed that the product is often the focus of doctoral training, support, and policy environments (CHE, 2022; Cutri, et al., 2021; Smith McGloin, 2021). Although university and government policies and guidelines at doctoral level do speak to the need to educate and develop researchers (for example, the Vitae Framework for Researcher Development used in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Australia, and parts of the European Union), practice wisdom suggests that the process itself may be under-considered or perhaps assumed (Cutri, et al., 2021) rather than explicitly focused on in many contexts. This implies that the attributes and dispositions of successful researchers may be subsumed into a focus on aspects of doctoral education directly linked to the creation of the product (the thesis). This may lead, as argued by Aitchison and Mowbray (2013), Cutri, et al. (2021), Manathunga (2007), and Smith McGloin (2021), to intense struggles with thesis writing and working with feedback on writing, to doctoral researchers feeling like imposters, to struggles in integrating into and becoming part of a research culture, and to anxiety around time to completion.

The 'ideal' doctoral student

There is a great deal of published research on many different aspects of being a 'good' or successful doctoral candidate. Studies focus on, for example, working with feedback and doctoral writing (Aitchison, et al., 2012; Wei, et al., 2019), managing difficult emotions in relation to aspects of university administrative processes (McAlpine, et al., 2012), managing supervision relationships and processes (Parker-Jenkins, 2018), and academic integrity and ethical behaviours (Cutri, et al., 2021). A key feature of a successful candidate, especially in systems that overtly reward quicker completions times and high throughput rates, is their ability to manage their time and their project effectively so that they can complete as quickly as possible (for example, the UK and South Africa both cite three years as the minimum time for completion of a full-time PhD). This may have implications for how candidates manage their work-life balance, as supervisors may expect the project to come before everything else (see Guerin, et al., 2014). Further, this may impact on the development of the doctoral person: studies have shown, more so in the last decade, that mental health struggles are on the rise in doctoral student cohorts, particularly anxiety and depression (Evans, et al., 2018; Jackman, et al., 2022); these struggles have been exacerbated during the Covid pandemic. Addressing these is a key focus of policy and practice in contexts such as the UK and Europe.

The 'ideal' doctoral supervisor

To create both an original contribution to knowledge and develop an expert scholarly identity, doctoral candidates require the support, assistance, and guidance of at least one research supervisor. There is much research dealing with the nature of good or supportive supervision and its converse. Studies argue that 'ideal' supervisors are attentive to candidates' requests for help (Äkerlind & McAlpine, 2017), adaptable and flexible, especially for part-time candidates or in cases where candidates' circumstances or study plans change, and are able and willing to offer constructive feedback that enables candidates to learn the discourses of the discipline through their writing, reading, and thinking work (Kumar & Stracke, 2007; Stracke & Kumar, 2020). Additionally, supervisors are called on to be attentive to candidates' mental and emotional wellbeing, referring candidates for professional assistance as needed and generally being kind and accommodating where needed (Määttä & Uusiautti, 2015; Strandler, et al., 2014). This research points to the need for supervisors to 'see' their candidates in the sense of recognising them as whole people with full lives that include but are not solely focused on their doctorate.

But being and becoming an 'ideal' supervisor in line with what research suggests this entails involves not only shepherding a process towards the creation of a product but nurturing and educating a doctoral person. The context of the university, institutional culture, and departmental and disciplinary cultures and expectations can have a profound impact on what counts as a legitimate 'product' as well as a valued and successful doctoral graduate. Many factors shape who a candidate is coming into a doctorate, why they choose to do a one, what they want to do with that degree, and who they are when they graduate. Many of these are not within the remit of the supervisor or the university to manage or control, of course. But the point here is the field needs to be careful - in speaking about the main dispositions and attitudes higher education values in a successful doctoral student - not to gloss over the complexities of taking on a doctoral identity and making it authentic, especially given the diversity of student and supervisor cohorts in terms of race, gender, social class, dis/ability, nationality, sexuality, language, and future career goals and plans. Doctoral educators and supervisors need to question and reflect on what the letters 'Dr' mean in terms of the expectations of graduates in the context in which they work. For example, in the arts, humanities and social sciences where the development and expression of an authorial 'voice' is a particular marker of success, yet where 'loneliness' is a seemingly common part of the doctoral journey (Hughes & Tight, 2013), what kinds of affective development are needed to help candidates find and develop their voice? What can supervisors and researcher developers do in these disciplines to create opportunities for wider conversations about knowledge-making as well as knower-making work?

Questions that this paper is reflecting on include how we become and be a Doctor in our chosen field of research and practice. This is increasingly coming to the fore of research and practice, especially given the growing size and diversity of doctoral student cohorts in both the global North and South (Cloete, et al., 2015; Nerad, 2021). Research increasingly shows the importance of thinking about emotions, mental wellbeing, and community: writing at doctoral level involves particular sets of knowledge-making and meaning-making practices which implicate disciplinary knowledge, certainly, but crucially, values, ways of reading, writing, thinking and also being and acting (Inouye & McAlpine, 2019). This means that we do not only need epistemological resources to do research and write a thesis; we also need axiological and ontological resources (see Cutri, et al., 2021; Frick, 2011). In other words, we need emotional resources, value-oriented resources, community or cultural resources, and knowledge resources to complete a doctoral degree successfully and become a recognised researcher and peer in our fields of study. A successful doctoral graduate, then, is a 'constellation' of different attributes, dispositions, skills, knowledges, and behaviours. To explore more fully what the field of doctoral education values in terms of dispositions and attributes specifically, we have chosen a theoretical and analytical tool from the broad framework of Legitimation Code Theory (Maton, 2020; Maton & Doran, 2021) that has enabled us to tease apart and visualise this part of this constellation that we believe needs to be examined more closely.

Legitimation Code Theory: Constellations

Semantics is a dimension of the larger framework of Legitimation Code Theory (LCT), which focuses on the relative context-dependence of meanings (termed semantic gravity) and the relative complexity of meanings (termed semantic density) (Maton, 2020). The value of using the dimension of Semantics in research and practice is in looking more closely at practices of meaning-making, so not only what meanings matter in a specific context, but the extent to which these meanings are context-dependent, the relative complexity of meanings, and the interconnectedness of meanings. You can zoom into specific meanings, zoom out to the bigger picture, and zoom across contexts to see connections and gaps. In this paper, we are focusing specifically on semantic density. Semantic density provides a useful way for conceptualising the multiple meanings within and between concepts, practices, ideas, and beliefs. The process of adding more meanings to a concept, practice, idea, or belief is referred to as condensation (Maton & Doran, 2021). The greater the condensation, the stronger the semantic density, and vice versa.

There are two different forms of semantic density, epistemological semantic density (ESD) and axiological semantic density (ASD). Briefly put, epistemological semantic density relates to the building of knowledge. Studies have used this concept to look at how a curriculum connects and builds knowledge into a larger whole, for example Rusznyak (2020) and Maton and Doran (2021). Axiological semantic density relates to the building of knowers, as, for example, Lambrinos' (2019) work has shown: building particular dispositions, attitudes, and ways of being that are valued or necessary for success. We have argued thus far that there is a product and a process in producing both the thesis and the doctoral graduate. Therefore, we build both epistemological semantic density and axiological semantic density in any doctoral journey.

However, as we are interested here in the doctoral graduate and the process by which this person develops, tacitly and consciously, we are focused on the condensation of axiological meanings within doctoral study and will use the concept of axiological semantic density to unpack these meanings.

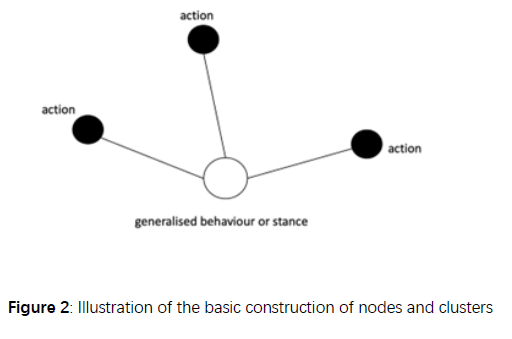

One of the ways that axiological (and epistemological) semantic density can be conceptualised and mapped is through constellations (Maton & Doran, 2021). Constellations are 'groupings (of any socio-cultural practice) that appear to have coherence from a particular point in space and time to actors adopting a particular cosmology or worldview' (Maton, 2016: 237). Doctoral education can be conceptualised as a constellation with groupings of stances, beliefs and practices that frame how we understand the ways in which we debate and critique knowledge, write and revise our work, talk to other researchers and stakeholders within our networks, manage our supervisors and ourselves, and how doctoral education relates to other fields and contexts within and beyond higher education. Each constellation comprises smaller clusters; these clusters are 'groupings of practices that come together and create meaning about a particular stance' (Lambrinos, 2019: 62). For example, a cluster of actions and behaviours which demonstrate a disposition of (self) confidence or independence in a candidate. Each cluster comprises linked nodes, which in our study tend to represent concrete actions and expectations that imply an attribute or disposition, such as confidence. These on their own may have meaning, but when linked to other nodes (actions/expectations) within a cluster these meanings may become more nuanced through being related to other meanings (nodes). Constellations can be zoomed in to visualise the relative complexity of a single meaning, for example 'independence' or 'confidence' : two dispositions valued as markers of success at doctoral level. Constellations can also be zoomed out to show how clusters are connected to one another.

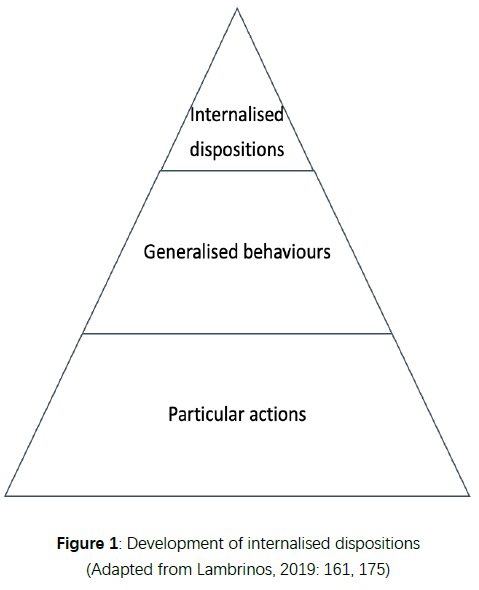

To explore the axiological condensation of the attributes and dispositions that are both expected and required for doctoral candidates to be successful, we have adapted Lambrinos' (2019) model for getting at harder-to-see internalised dispositions through tracking examples or evidence of more visible behaviours and concrete actions that imply the presence and development of these necessary dispositions (Figure 1). We will be building clusters around two often-mentioned ideal attributes for success in doctoral study, namely independence and confidence. There are many more valued attributes and dispositions, some of which may be discipline-specific and context-dependent and some of which may be shared across different disciplines and contexts, but we are focusing on these two for the purposes of this paper and the limitations of space.

In building the clusters discussed in the next section, we started by identifying the internalised dispositions and attributes that candidates are expected to develop and display over the course of the doctorate. We then looked for the evidence the literature provided that indicated the development or presence of these internalised dispositions, which led us to what we then separated into generalised behaviours and concrete actions. In our clusters, the solid dots are nodes (see Figure 2); these are actions, such as 'choose and contact your prospective supervisor' (Independence) and 'Join a local or online writing group' (Confidence). These actions identified as nodes were then grouped into clusters where they pointed to more generalised behaviours or stances, such as taking initiative or valuing collaboration, which is denoted with an open dot. These smaller groupings of meanings - clusters - were then connected into larger clusters of meanings around the organising point, which is the internalised disposition or attribute implied by these actions and behaviours, here these are independence and confidence.

Before we discuss the findings, we want to acknowledge again that because this is conceptual work, we are rather deliberately simplifying a complex issue. We are doing this because we want to see the possible potential meanings hidden within seemingly straightforward attributes such as becoming confident, being independent, showing authority, or taking initiative, and illustrate how un-straightforward developing these attributes might be for many candidates.

Reading the field of doctoral education

The data used in the analysis has been drawn from published research in peer-reviewed journals in the field of higher education studies more broadly, and doctoral and postgraduate education more specifically. We chose peer-reviewed papers only rather than including the grey literatures, mainly for practical reasons. There would simply be too much data to if we included popular presses and blogs; there is a great deal of published peer-reviewed work on doctoral education, and specifically on notions of what makes for a successful doctorate and doctoral candidate.

The process of generating data began with a conversation between us (Sherran as primary supervisor and Martina as doctoral candidate) about Martina's doctoral journey and what did and did not help her own process of becoming a 'Doctor' . This grew into a larger conversation about feedback and support for writing, battling with poor self-confidence and isolation, and the role supervision can play in opening spaces to grapple less privately with some of the affective dimensions of the doctoral journey. We noted the relative lack in the literature we were both reading of explicit mention of how these affective attributes or characteristics are developed, which led us back to this literature; we created our dataset as we re-read these papers, looking more closely at the meanings implied in and overtly discussed around the dispositions and attributes of successful doctoral candidature. We expanded our reading organically through following citations, for example, looking at the reference lists of papers that were overtly focused on, for example, emotions in doctoral study (Mowbray & Aitchison, 2013) or imposter syndrome (Cutri, et al., 2021), and returning to databases to look for papers that considered similar issues from different geographical and theoretical perspectives. It would be impossible to create any kind of exhaustive reading list, so we managed the reading list in relation to saturation, i.e., when we felt we were not seeing any new actions or implied behaviours mentioned in further reading.

As we read, we created a shared table in Google Drive in which we captured the bibliographic reference, a summary of the main argument or focus of the paper, and a set of keywords pertaining to attributes, dispositions and 'ways of being' in doctoral study, especially to success in doctoral study. Under each attribute (e.g., self-confidence) we captured what counted as evidence of this (e.g., asking to change supervisors, or volunteering to present work in progress). This table was then refined using the model adapted from Lambrinos (2019) into the two tables in the following section. Sherran then coded the data around confidence and Martina coded the data around independence, using the same tabular coding template we created together. We then met to compare, debate, and refine our codes and findings, and collaboratively drew the clusters discussed in the following section.

Altogether we read and annotated papers written by researchers in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Sweden, Finland, Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. We were able to therefore track a range of different understandings of what it means, for example, to become and be confident, independent, resilient, self-regulated, articulate - all often-cited attributes and dispositions of successful doctoral candidates. In the discussion that follows we will focus on two particularly prevalent attributes and the behaviours and actions that attach to these in the literature we have consulted: independence and confidence.

Findings

In this section we reflect first on independence and then on confidence. We begin with a table that captures a distilled version of the coding process, followed by an account of some of the data that has been drawn on in the coding process, and finally a visual representation of the cluster we have created following the process outlined earlier in the paper.

Independence

Independence is a highly sought-after quality for PhD candidates and it is regularly mentioned in articles pertaining to doctoral journeys and development - the 'independent scholar' or the 'independent researcher' is seen as a defining attribute signalling the completion of the PhD (Frick & Brodin, 2014; Halai, 2011; Manathunga, 2011; Mullins & Kiley, 2002; Overall, et al., 2011; Sverdlik, et al., 2018; Frick, et al., 2016). Yet, as our reading has found, there are inherent tensions in how independence is seen in the literature. Independence is simultaneously an attribute that candidates need to possess before attempting a PhD (Carter, et al., 2013) and should be developed gradually over the course of the PhD (Gurr, 2001; Halai, 2011). Independence is also an attribute that needs to be developed both one one's own and in collaboration with others (Blaj-Ward, 2011; Gardner, 2009; McAlpine, 2012). Thus, independence is something doctoral candidates should have and is something that they should be (Sverdlik, et al., 2018; Lovitts, 2005), especially in the arts and humanities where many candidates work outside of teams or established groups of scholars (Table 1).

In drawing the independence clusters, we sought to distinguish between concrete actions and generalised behaviours. To start, we perused the literature for mentions of concrete actions - things that the doctoral candidate must do to be recognised as being independent. For example, an independent doctoral candidate must be able to select a supervisor and a topic (Lovitts, 2005), set and meet deadlines (Sverdlik, et al., 2018), take ownership of decisions about their research (Overall, et al., 2011), engage critically with feedback (Grant, 2003), work without guidance (Cotterall, 2011), and seek and make use of resources (McAlpine, 2012). Some of these actions pertain to things that must happen before the start of researching the thesis, some are expected during the writing of the thesis, and others are expected when the thesis is completed. For example,

Since the supervisor's main goal is to ensure that the student becomes an independent researcher, students who consistently respect timelines, prepare for meetings, exhibit openness and respect for feedback, and demonstrate their capabilities in their work, are likely to ensure the satisfaction of their supervisors in the relationship. (Sverdlik, et al., 2018: 371)

These actions (in bold) were then grouped together as generalised behaviours, for example, being able to design and manage a research project and developing research and writing skills were seen as examples of taking initiative; being able to meet deadlines, prepare for meetings, and engage with feedback were seen as working autonomously. Often, these behaviours were stated in the literature. For example, '[a] third [faculty member] defined a successful student as 'a person who initiates [his or her] own research agenda and is able to work individually and collaboratively. They take their own initiative' (Gardner, 2009: 393). At other times, behaviour was implied. For example, 'I am particularly fond of supervision as it allows me to see students who were initially dependent on me for development of their research skills and scholarship slowly but surely blossoming into independent scholars and becoming experts in their areas of study' (Halai, 2011: 45) The implication here is that an independent scholar is more self-reliant and has their own expertise to draw on.

The terms 'independent' or 'independence' were regularly used with no qualification - the assumption being that there is an implied, shared understanding of what being independent or having independence means for the doctoral candidate. These are a few examples:

... [a]doctoral graduate should become an independent researcher with multiple competences, including leadership, communication, and multitasking. (Han & Xu, 2021: 12)

... a term used frequently to describe positive theses was 'scholarship' , described by interviewees from all disciplines as originality, coherence, and a sense of student autonomy or independence. (Mullins & Kiley, 2002: 379)

A principal challenge of doctoral supervision is how to provide enough guidance for students to learn research skills while giving students autonomy to become confident independent researchers. (Overall, et al., 2011: 791)

This analysis has been distilled into the visualisation in Figure 3 of the independence cluster we have identified as being part of a larger constellation of 'successful doctoral candidate' . As a reminder, the open dots are the behaviours, named in Table 1 in the middle column, and the closed dots are the concrete actions that are expected of candidates.

Confidence

Confidence - expressed in the literature as both the candidate's confidence in themselves, the confidence they exhibit or express through externally-facing engagement, and the confidence their supervisors have in them - is a significant theme running through the work on different aspects of successful doctoral candidature. We have excluded the work around supervisors and their confidence in the researchers they work with, as we are focused here on the candidates and what is being said and/or implied to them when supervisors, researcher developers and so on tell them they need to become and be more confident.

Confidence, both self-confidence or belief in one' s own ability and competence and the confidence we then project to others, seems to develop around three sets of behaviours: those related to writing and feedback; those related to being part of a community of peers; and those related to becoming more immersed in a discipline and body of knowledge and related skills and competencies. Table 2 below indicates the specific actions the literature indicates as being useful, relevant, and common for doctoral candidates, both to increase or add to their confidence or to mitigate threats to their (self) confidence.

In relation to writing and feedback, the literature mentioned both the development and enhancement of confidence as well as threats to confidence. Actions here were related to finding other people to write with or speak with about one's writing; reflecting on feedback received and being proactive about asking for specific kinds of feedback, both from supervisors and from one' s wider scholarly community; revising and reworking one' s writing; and attending training workshops to develop writing skills and practices. Here, we see authors talking about the importance of focusing on behaviours such as becoming skilled and embracing collaboration and community in the first instance. In the second instance, the behaviour implied is around self-management in the face of an event that has undermined a candidate' s confidence:

I developed confidence in my own ability to analyse my own and the work of the others in the group, because of the skills of analysis that we learnt. This allowed me to position myself as student with authority over my own work, such that I could argue for my ways of thinking and writing, challenging critique for the first time in my years as a student. The work with the group gave me the skills to become a confident academic writer after many years of undergraduate and post-graduate experiences. (Maher, et al., 2008: 265)

Our earlier review of literature showed that some students experience criticisms delivered by supervisors as damaging to their self-esteem and confidence. (Li & Seale, 2007: 521)

Research that focuses on feedback playing a significant role in building (and undermining) confidence tends to point to actions that both enhance a candidate' s own confidence or implies actions that may need to be taken to mitigate threats to or perceived attacks on their self-confidence. Actions coded here included being proactive about approaching supervisors for meetings and feedback; reflecting critically on feedback and creating action plans for revisions; engaging in positive self-talk after difficult criticism; seeking feedback from peers and critical friends; offering feedback as a critical friend to others; looking beyond supervision for help with writing (i.e., mitigating over-reliance on supervisors); and developing the ability to explain and defend one's ideas to others. The behaviours implied by these actions have been captured as 'liminal' (i.e., being comfortable with not having all the answers), being collaborative, and managing oneself and others (particularly supervisors, it seems).

There is significant overlap in the data between developing confidence through positive feedback and despite negative feedback and being part of a scholarly community of peers. Peer writing groups or communities are a significant space for developing one' s self-confidence, a necessary pre-requisite for projecting confidence in one' s writing, willingness to share work-in-progress formally and informally, and thereby making progress in the doctorate. In the text below, we see authors speaking about the value of being engaged'with other writers and how that built their confidence as well as their writing skills:

It has been shown that the peer feedback component of these types of writing groups helps students to build their writing confidence, foster greater reflective practice, and encourage them to take ownership of their writing style. (Cutri, et al., 2021: 11)

In contrast to many other institutionally sanctioned forums such as the often competitive, combative spaces of research forums, training workshops and student conferences, writing groups were hotbeds of emotion, that helped participants build confidence and resilience. (Aitchison & Mowbray, 2013: 865)

The third area mentioned that appears closely linked to the development of confidence -both self-confidence and confidence expressed through written text and spoken engagement (for example, in supervision meetings or at colloquia/conferences) - is becoming immersed in a discipline and proficient in understanding and using a pertinent body of knowledge and related skills and competencies. The literature here speaks about the need for candidates to claim a 'voice' and to be authoritative in their writing, but this is closely connected to mentions of disciplinary discourses and conventions and being skilled not generically but in the specialist ways of working in different disciplines or fields of study (see also Duff, 2007; Paré, 2010).

To claim and express a voice, of which an original argument is a significant part, postgraduate student-writers must have confidence in their claims to knowledge, and in the evidence and explanation they have selected and developed to sustain that argument. They need to believe they have something original and worthy to add to the conversations and debates that their discourse or disciplinary community is interested in. (Clarence, 2020: 50)

Journey is aware of cultural differences in rhetorical organisation and genre, disciplinary conventions and of his rhetorical choices as a writer. He is also open to the idea of experimentation in writing. ... Journey has twice initiated contact with international experts in his field to seek feedback on his draft papers, reporting that their positive responses boosted his confidence and reassured him of the relevance of his work. (Cotterall, 2011: 420)

This analysis has been distilled into a visualisation (Figure 4) of the confidence cluster we have identified as being part of a larger constellation of 'successful doctoral candidate' . As a reminder, the open dots are the behaviours, named in Table 2 in the middle column, and the closed dots are the concrete actions that are expected of candidates.

Discussion

There are three overarching threads that we have drawn from our investigation thus far: complexity, diversity, and disciplinary discourse(s). We now discuss the implications of our findings following these threads.

In terms of complexity, we are referring to what our clustering process has shown us (see Figures 3 and 4). Specifically, how many possible axiological meanings are condensed into seemingly straightforward dispositions such as 'independence' and 'confidence' . Other dispositions we have coded in the wider study speak to successful candidates being self-regulated, resilient, meticulous, creative, autonomous, and persistent. The process of using the LCT tools discussed in this paper to isolate, characterise, and then connect actions into more generalised behaviours, and then into internalised dispositions illustrates that becoming and being independent, confident, resilient, and more is not simple at all. In fact, these processes of becoming and being are ongoing (without a defined end point) and multi-layered. They are also not linear; confidence in one' s writing, for example, waxes and wanes as we get feedback, begin new writing projects, and grapple with revisions (Aitchison, et al., 2012; Inouye & McAlpine, 2019). Yet, supervisors, doctoral and researcher educators/developers and the field itself refer to these dispositions frequently in relation to the kinds of things we want doctoral candidates to be doing, thinking and being, without necessarily interrogating what we mean, what we are asking them to do practically, and what kinds of resources they need access to so that they can develop what are regarded as successful dispositions and attributes. This points to a need for supervisor and researcher development work to focus on these affective, dispositional aspects of doctoral success so that meanings attached to markers of success can be interrogated and made visible to those working with doctoral candidates as well as to the candidates themselves.

This interrogation and visibility is crucial now more than ever as doctoral cohorts around the world are becoming increasingly diverse in a range of ways, some less obvious than others. The more obvious ways in which we think of diversity include race, socioeconomic status, gender, (dis)ability, sexual orientation. But doctoral cohorts are also diverse in terms of their registration status (part or full time); their route to the doctorate (i.e., their prior academic learning and training at Master's and undergraduate level); the kind of doctorate they are enrolled for (e.g., practice-based, professional, or 'traditional big book' doctorate); the languages they read, write and think in; whether they are 'home' or 'international' candidates; how much support they have from family and friends; whether they have caring responsibilities or not. This multi-layered diversity affects the ways in which doctoral candidates engage with their studies, their supervisors, and their peers - how they ask for help, who they ask, whether and how they 'network', and how they respond to feedback, advice and guidance - which all connects with the actions they take to develop valued behaviours and internalised dispositions.

In essence, our analysis here shows at the very least how many possible actions are part of, for example, displaying 'scholarly' behaviour as it connects to becoming and being a more confident researcher. Consider the extent to which a part-time candidate who is a woman, self-funded and has significant caring responsibilities (e.g., children) can 'attend and present their work at conferences' compared to a single researcher who has funding and few or no additional responsibilities at home. Their respective capacity to develop the kinds of confidence that come from attending conferences, engaging with experts and other researchers, and thereby undertaking different forms of public engagement will be quite different. The first researcher may be considered less successful than the second one if she has only attended two conferences to the other researcher's four or five, but would this account of success have considered their different circumstances and access to resources such as childcare or funding? Considering the (inexhaustive) range of actions and behaviours our present clusters illustrate and then asking questions that dig deeper into different candidates' circumstances may enable us, firstly, to offer differentiated and sensitive support to candidates like the first researcher who may need more help getting to a conference than the second, and secondly, to widen our definitions of successful engagement and perhaps create different ways in which doctoral candidates can network and share their research locally.

A final thread we have identified in the data is the ways in which the discipline or field the candidate is working within constructs some actions and behaviours as successful whereas others may contradict this. For example, in many of the sciences teamwork is highly valued; researchers join labs or teams, and they construct knowledge for their own projects both individually and collaboratively. They are not expected to work out things on their own. By contrast, in several of the social sciences and arts and humanities disciplines, still, the 'lone scholar' is a more recognisable trope where candidates are expected to construct knowledge on their own or with one or two supervisors, and where networking and finding external communities or collaborators can be harder as these are not typically part and parcel of the research environment. We have looked at research emerging from several different countries and higher education systems and what is interesting is that the internalised dispositions and attributes expected in a successful doctoral graduate are relatively consistent across these contexts. Everyone wants to graduate 'doctors' who are independent, self-regulated, confident, resilient, meticulous, creative, autonomous, persistent. But the expectations of what it is to be 'creative' or 'meticulous' will likely be quite different for a philosopher and a textile designer, or for a political scientist and an art historian. Thus, even in the arts and humanities, there are no set definitions of these attributes. Therefore, the clusters we have created thus far can be further refined and extended through considering actions and behaviours that are valued in particular disciplines in relation to how they make knowledge and what kinds of knowers or researcher dispositions they value and seek to cultivate. Similarly, there may be behaviours in some national, regional and cultural contexts that do not look the same in others, pointing to the need to create contextualised clusters and constellations within your own discipline, field, and national or societal context.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper has been to examine and make visible the various meanings embedded in attributes that doctoral candidates are expected to have and/or develop throughout the course of the doctoral journey, focusing specifically on two attributes mentioned regularly in the literature: confidence and independence. In both instances, our analysis has shown that there are multiple axiological meanings embedded in these seemingly straightforward dispositions; there are also tensions within and between these meanings that might make it difficult for candidates to understand and navigate what is required of them. For instance, our analysis has shown that some of the behaviours that may relate to becoming and being independent, such as working things out without leaning too much on others, may contradict behaviours that contribute to building confidence, such as forming and relying on peers in a writing group. Although we have focused on these two attributes, there are many others such as being collaborative (Kiley, 2009), creative (Lovitts, 2015), persistent (McAlpine, et al., 2012), adaptable (Barret & Hussey, 2015), resilient (Aitchison, et al., 2012), enthusiastic (Äkerlind & McAlpine, 2017), assertive (Carter & Kumar, 2017), and resourceful (Li & Seale, 2007). Our analysis process could be applied to making visible the meanings embedded in these dispositions or attributes, too.

We have used constellations and axiological semantic density from Legitimation Code Theory as conceptual and analytical tools to both zoom in on specific attributes and to zoom out to see the connected nature of these attributes as they relate to overall doctoral success. Our contention is that if we can see and name the meanings that are pertinent and embedded in our contexts and in our university and social cultures, as well as those that may transcend our local institutions, disciplines, and contexts, we as educators and supervisors can begin a process of interrogating these more closely. Specifically, we can start questioning whether our expectations are fair, in the first place - whether we are expecting the same outcomes of all candidates without taking their circumstances, motivations and access to resources into closer account. We can explore the extent to which our expectations are visible and explained to candidates through supervision, training and education, and other events doctoral candidates attend during their candidature. Further, we can question the extent to which we may be applying a 'cookie cutter' mold to the education, training, and supervision of heterogenous cohorts of doctoral candidates, in terms of who they are, why they are doing a doctorate, and the disciplines or fields in which they are working.

Our analysis has implications for supervision, researcher development and doctoral education, as well as research support and admissions. It firstly highlights the importance of understanding and naming what might be embedded in these expected attributes, and secondly, allows for a greater understanding of what universities want doctoral candidates to be and do in their disciplines and fields, in local and national contexts, and across these. This in turn enables doctoral educators and supervisors to adjust their practices to meet the needs of all candidates. Doctoral candidates are not islands, but part of larger, complex wholes that encompass knowledge, ways of knowing and doing, and ways of being.

What we hope this conceptual analysis contributes to the field of doctoral education and is an opening of space and a tool with which to speak about how we can do doctoral education and supervision in socially just ways. As this paper is conceptual in nature, there is room to explore these attributes in a more empirical manner. We hope that further research leads to greater recognition of different versions of doctoral success and being that give deeper realisation to the espoused goals of equity, diversity, inclusion, and transformation, in higher education.

Author biographies

Sherran Clarence is a senior lecturer at Nottingham Trent University specialising in doctoral education and development. She is also a senior research associate in CHERTL at Rhodes University. Her current research focuses on enabling greater representation and belonging in academia for doctoral and early career researchers, informed by feminist and participatory theories and methods.

Martina van Heerden is a senior lecturer in English for Educational Development at the University of the Western Cape. Her research focuses on feedback on student writing, specifically the role of feedback in assisting students to take on relevant ways of knowing and disciplinary dispositions in addition to the knowledges valued in the disciplines. Her work has appeared in Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning, and Innovations in Education and Teaching International.

References

Aitchison, C., Catterall, J., Ross, P. & Burgin, S. 2012. 'Tough love and tears' : Learning doctoral writing in the sciences. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(4): 435-447. [ Links ]

Aitchison, C. & Mowbray, S. 2013. Doctoral women: Managing emotions, managing doctoral studies. Teachhing in Highier Education, 18(8): 859-870. [ Links ]

Äkerlind, G. & McAlpine, L. 2017. Supervising doctoral students: Variation in purpose and pedagogy. Studies in Higher Education, 42(9): 1686-1698. [ Links ]

Barnacle, R. 2005. Research education ontologies: Exploring doctoral becoming. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(2): 179-188. [ Links ]

Barnacle, R. & Mewburn, I. 2010. Learning networks and the journey of 'becoming doctor' . Studies in Higher Education, 35(4): 433-444. [ Links ]

Barrett, T. & Hussey, J. 2015. Overcoming problems in doctoral writing through the use of visualisations: Telling our stories. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(1): 48-63. [ Links ]

Blaj-Ward, L. 2011. Skills versus pedagogy? Doctoral research training in the UK Arts and Humanities. Highier Education Research and Development, 30(60): 697-708. [ Links ]

Carter, S., Blumenstein, M. & Cook, C. 2013. Different for women? The challenges of doctoral studies. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(4): 339-351. [ Links ]

Carter, S., Kensington-Miller, B. & Courtney, M. 2017. Doctoral supervision practice: What's the problem and how can we help academics? Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 5(1): 13-22. [ Links ]

Carter, S. & Kumar, V. 2017. 'Ignoring me is part of learning' : Supervisory feedback on doctoral writing. Innovations in Education and Teachhing International, 54(1): 68-75. [ Links ]

CHE. 2022. National review of South African doctoral qualifications. 2020-2021. Doctoral Degrees National Report, March 2022. Pretoria: Council on Higher Education. Available at: https://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/inline-files/CHE%20Doctoral%20Degrees%20National%20Reporte.pdf (Accessed: 20 March 2023). [ Links ]

Clarence, S. 2020. Making visible the affective dimensions of scholarship in postgraduate writing development work. Journal of Praxis in Higher Education, 2(1): 46-62. [ Links ]

Cloete, N., Mouton, J. & Sheppard, C. 2015. Doctoral education in South Africa. Cape Town: African Minds. [ Links ]

Cutri, J., Abraham, A., Karlina, Y., Patel, S.V., Moharami, M., Zeng, S., Manzari, E. & Pretorius, L. 2021. Academic integrity at doctoral level: the influence of the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences on academic writing. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17(1): 1-16. [ Links ]

Doloriert, C., Sambrook, S. & Stewart, J. 2012. Power and emotion in doctoral supervision: Implications for HRD. European Journal of Training and Development, 36(7): 732-750. [ Links ]

Duff, P. 2007. Problematising academic discourse socialisation. In Marriott, H., Moore, T. & Spence-Brown, R. (Eds.), Learning discourses and the discourses of learning. Melbourne: Monash University Press, 1.1-1.18. [ Links ]

EDEPI. n.d. Equity in Doctoral Education through Partnership and Innovation. Available at: https://www.ntu.ac.uk/c/equity-in-doctoral-education-through-partnership-and-innovation (Accessed: 20 March 2023).

Evans, T.M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J.B., Weiss, L.T. & Vanderford, N.L. 2018. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3): 282-284. [ Links ]

Frick, L. 2011. Facilitating creativity in doctoral education: A resource for supervisors. In Kumar, V. & Lee, A. (Eds.), Doctoral education in international context: Connecting local, regional and global perspectives. Serdang: Universiti Putra Malaysia Press, 123-137. [ Links ]

Frick, B.L. & Brodin, E.M. 2014. Developing expert scholars: The role of reflection in creative learning. In Shiu, E. (Ed.), Creative research: An inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary research handbook. London: Routledge, 312-333. [ Links ]

Frick, L., Albertyn, R., Brodin, E., McKenna, S. & Claesson, S. 2016. The role of doctoral education in early career academic development. In Fourie-Malherbe, M., Aitchison, C., Bitzer, E. & Albertyn, R. (Eds.), Postgraduate supervision: Future foci for the knowledge society. Stellenbosch: AFRICAN SUN MeDIA, 203-219. [ Links ]

Gardner, S.K. 2009. Conceptualizing success in doctoral education: Perspectives of faculty in seven disciplines. The Review of Higher Education, 32(3): 383-406. [ Links ]

Grant, B. 2003. Mapping the pleasures and risks of supervision. Discourse: Studies in Cultural Politics of Education, 24(2): 175-190. [ Links ]

Gurr, G.M. 2011. Negotiating the 'Rackety Bridge' : A dynamic model for aligning supervisory style with research student development. Higher Education Research and Development, 20(1): 81-92. [ Links ]

Guerin, C., Kerr, H. & Green, I. 2015. Supervision pedagogies: Narratives from the field. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(1): 107-118. [ Links ]

Halai, N. 2011. Becoming and being a doctoral supervisor in Pakistan: A lived experience. In Kumar, V. & Lee, A. (eds). Doctoral education in international context: Connecting local, regional and global perspectives. Serdang: Universiti Putra Malaysia Press, 37-49. [ Links ]

Hughes, C. & Tight, M. 2013. The metaphors we study by: The doctorate as a journey and/or as work. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(5): 765-775. [ Links ]

Inouye, K. & McAlpine, L. 2019. Developing academic identity: A review of the literature on doctoral writing and feedback. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 14: 1-31. [ Links ]

Jackman, P.C., Jacobs, L., Hawkins, R.M. & Sisson, K. 2022. Mental health and psychological wellbeing in the early stages of doctoral study: a systematic review. European Journal of Higher Education, 12(3): 293-313. [ Links ]

Kiley, M. 2009. Identifying threshold concepts and proposing strategies to support doctoral candidates. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(3): 293-304. [ Links ]

Kiley, M. & Wisker, G. 2009. Threshold concepts in research education and evidence of threshold crossing. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(4): 431-441. [ Links ]

Kumar, V. & Stracke, E. 2007. An analysis of written feedback on a PhD thesis. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(4): 461-470. [ Links ]

Kumar, V. & Stracke, E. 2011. Examiners' reports on theses: Feedback or assessment? Journal of English for academic purposes, 10(4): 211-222. [ Links ]

Lambrinos, E. 2019. Building Ballet: developing dance and dancers in ballet. Doctoral dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. [ Links ]

Li, S. & Seale, C. 2007. Managing criticism in PhD supervision: A qualitative case study. Studies in Higher Education, 23(4): 511-526. [ Links ]

Lovitts, B.E. 2005. Being a good course-taker is not enough: A theoretical perspective on the transition to independent research. Studies in Higher Education, 30(2): 137-154. [ Links ]

Määttä, K. & Uusiautti, S. 2015. Two perspectives on caring research: Research on well-being and researcher well-being. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 66: 29-41. [ Links ]

Maher, D., Seaton, L., McMullen, C., Fitzgerald, T., Otsuji, E. & Lee, A. 2008. 'Becoming and being writers' : The experiences of doctoral students in writing groups. Studies in Continuing Education, 30(3): 263-275. [ Links ]

Manathunga, C. 2007. Supervision as mentoring: The role of power and boundary crossing. Studies in Continuing Education, 29(2): 207-221. [ Links ]

Manathunga, C. 2011. Post-colonial theory: Enriching and unsettling doctoral education. In Kumar, V. & Lee, A. (Eds.), Doctoral education in international context: Connecting local, regional and global perspectives. Serdang: Universiti Putra Malaysia Press, 85-100. [ Links ]

Maton, K. 2016. Starting points: Resources and architectural glossary. In Maton, K., Hood, S. & Shay, S. (eds). Knowledge-building: Educational studies in Legitimation Code Theory. London: Routledge, 233-243. [ Links ]

Maton, K. 2020. Semantic waves: Context, complexity and academic discourse. In Martin, J.R., Maton, K. & Doran, Y.J. (Eds.), Accessing academic discourse: Systemic Functional Linguistics and Legitimation Code Theory. London: Routledge, 59-85. [ Links ]

Maton, K. & Doran, Y.J. 2021. Constellating science: How relations among ideas help build knowledge. In Maton, K., Martin, J.R. & Doran, Y.J. (Eds.), Teaching science: Knowledge, language, pedagogy. London: Routledge, 49-75. [ Links ]

McAlpine, L., Paulson, J., Gonsalves, A. & Jazvac-Martek, M. 2012. 'Untold' doctoral stories: can we move beyond cultural narratives of neglect? Higher Education Research & Development, 31(4): 511-523. [ Links ]

Mewburn, I. 2011. Troubling talk: Assembling the PhD candidate. Studies in Continuing Education, 33(3): 321-332. [ Links ]

Mowbray, S. & Halse, C. 2010. The purpose of the PhD: Theorising the skills acquired by students. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(6): 653-664. [ Links ]

Mullins, G. & Kiley, M. 2002. 'It' s a PhD, not a Nobel Prize' : How experienced examiners assess research theses. Studies in Higher Education, 27(4): 369-386. [ Links ]

Nerad, M. 2021. Opportunities and challenges of international research experiences during doctoral studies in a globalised doctoral education world. In Rule, P., Bitzer, E. & Frick, L. (Eds.), The global scholar. Implications for postgraduate studies and supervision. Stellenbosch: AFRICAN SUN MeDIA, 17-41. [ Links ]

Overall, N.C., Deane, K.L. & Peterson, E.R. 2011. Promoting doctoral students' research self-efficacy: Combining academic guidance with autonomy support. Higher Education Research and Development, 30(6): 791-805. [ Links ]

Paré, A. 2010. Slow the presses: Concerns about premature publication. In Aitchison, C., Kamler, B., & Lee, A. (Eds.), Publishing pedagogies for thie doctorate and beyond. New York: Routledge, pp.30-46. [ Links ]

Parker-Jenkins, M. 2018. Mind the gap: developing the roles, expectations and boundaries in the doctoral supervisor-supervisee relationship. Studies in Higher Education, 43(1): 57-71. [ Links ]

Rusznyak, L. 2020. Supporting the academic success of students through making knowledgebuilding visible. In Winberg, C., McKenna, S. & Wilmot, K. (Eds.), Building knowledge in higher education: Enhancing teachhing and learning with Legitimation Code Theory. London: Routledge, 90-104. [ Links ]

SJQinHE. n.d. PhD Studies in Social Justice and Quality in Higher Education. Available at: https://sites.google.com/ru.ac.za/sjqinhephd (Accessed: 20 March 2023).

Smith McGloin, R. 2021. A new mobilities approach to re-examining the doctoral journey: mobility and fixity in the borderlands space. Teaching in Higher Education, 26(3): 370-386. [ Links ]

Stracke, E. & Kumar, V. 2020. Encouraging dialogue in doctoral supervision: The development of the feedback expectation tool. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 15(1): 265-284. [ Links ]

Strandler, O., Johansson, T., Wisker, G. & Claesson, S. 2014. Supervisor or counsellor? Emotional boundary work in supervision. International Journal for Researcher Development, 5(2): 7082. [ Links ]

Sverdlik, A., Hall, N.C., MCAlpine, L. & Hubbard, K. 2018. The PhD experience: A review of the factors influencing doctoral students' completion, achievement and well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13: 361-388. [ Links ]

Trafford, V. & Leshem, S. 2009. Doctorateness as a threshold concept. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(3): 305-316. [ Links ]

Wei, J., Carter, S. & Laurs, D. 2019. Handling the loss of innocence: first-time exchange of writing and feedback in doctoral supervision. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(1): 157-169. [ Links ]

Yazdani, S. & Shokooh, F. 2018. Defining doctorateness: A concept analysis. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13(2018): 31-48. [ Links ]

Submitted: 2 December 2022

Accepted: 23 March 2023

# Corresponding Author: sherran.clarence@ntu.ac.uk

@PhDgirlSA; @nerdiqueen (Twitter)

1 In using the term 'thesis' in this paper we do acknowledge that this make take the form of a thesis by publication, a 'big book' thesis, a professional doctorate, a critical-creative project, or even a practice-based thesis. There are many forms of creating and presenting doctoral-level knowledge, although in South African universities the 'big book' seems to be the most common form (e.g., a +/- 80,000-word dissertation) (CHE, 2022: 51)