Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning

versión On-line ISSN 2310-7103

CRISTAL vol.10 no.2 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v10i2.551

ARTICLES

Using partial justice to interrogate the meanings and applications of social justice in service-learning

Ntimi N. Mtawa

Higher Education and Human Development Research Programme, University of the Free State

ABSTRACT

This paper provides an account of the concept of social justice and how it is loosely and uncritically defined and applied in service-learning context. Social justice is deemed as an approach to service-learning, which allows all actors to actively participate in decision-making, share power and benefit equally. This framing of social justice in service-learning is largely within the realm of John Rawls' perfect justice. There is relatively little attention given to small and actionable changes yielded in and through service-learning. As such, this paper uses the concept of 'partial justice' as purported by Amartya Sen to interrogate the meanings and applications of social justice in service-learning. The paper draws on qualitative data collected through document analysis, focus groups and semi-structured interviews with students, staff, and community members. The focus and contribution of the paper is timely and pertinent given the unexamined conceptions and use of social justice in service-learning context.

Keywords: Service-learning, social justice, perfect justice, partial justice, remediable injustice

Introduction

In the African, and particularly South African higher education context, service-learning is still conceptually and empirically an under-researched field. One of the salient features of service-learning in the mainstream literature is that it is often associated with the notion of social justice1. However, there is lack of critical analysis of what social justice in service-learning means, how can it be achieved and under what conditions. In fact, Hytten and Bettez (2011: 8) reveal that 'yet the more we see people invoking the idea of social justice, the less clear it becomes what people mean, and if it is meaningful at all'. Defined as a form of experiential education intended to address human and community needs together with structured opportunities designed to promote student learning and development (Jacoby, 1996), service-learning is largely regarded as a contributor of social justice in its broader sense (Mitchell, 2008; Stoecker, 2016; Unfried & Canner, 2019; LaDuca, et al., 2020). The debate about social justice in service-learning context is twofold. The first debate is a result of disenchantment with the traditional but dominant approach to service-learning (Boyle-Baise & Langford, 2004; Britt, 2012). Through this approach, higher education institutions frame and practice service-learning as a charity agenda rather than an empowering and transformative endeavour (Stoecker, 2017; Mtawa, 2019). At the core of the charity approach is the emphasis on helping others and developing a sense of altruism through giving back to the community in a goodwill and voluntary basis (Bialka, et al., 2019). The second debate is that of the adherents of social justice model of service-learning through which they provide a counterargument that the charity approach to service-learning is narrow and limits its transformative potentials. Those who argue for a social justice model position it as both an approach to, as well as an outcome of, service-learning. When embedded in a social justice approach, service-learning can serve as a repertoire through which participants, namely university staff and students, and multiple external communities transform and dismantle structures and conditions that perpetuate inequalities and injustices within higher education institutions and in local milieu (Mtawa, 2019; Li et al., 2019). Those who take this perspective (such as Schulz, 2007; Mitchell, 2008; Bialka et al., 2019) seem to share common assumptions and argue alongside John Rawls' notion of social justice, which connotes having just institutional and social arrangements in search for perfect justice. Such is an ambitious and ideal ways of articulating what can be achieved in and through service-learning.

While the social justice approach to service-learning continues to receive support and attention in the literature and empirical studies (Jessup-Anger, at al., 2019; Lee & McAdams, 2019), questions of what kind of justice, how it is or can be achieved and under what conditions remain unresolved. As described by Richards-Schuster, Espitia and Rodems (2019) social justice is not always clearly articulated or is articulated in different and sometimes contradictory ways particularly in service-learning field (Hytten & Bettez, 2011).

There are two observations that can be made when social justice is linked to service-learning. One, despite social justice remaining an enigmatic, cryptic, and imprecise concept (Srivastav, 2016) literature continues to describe service-learning as repertoire through social justice can be promoted. Two, the contribution of service-learning to advancing social justice is mainly framed in line with John Rawls' 'perfect justice' position. This paper is concerned with these observations as it questions the ability of service-learning to alter structural and systemic inequalities to build a perfect society. In doing so, the paper takes up Sen's position and uses the idea of 'partial justice' to interrogate the meanings and applications of social justice in service-learning. It is premised on two propositions. One, the concept of social justice is loosely used in service-learning context. Two, the conditions under which higher education institutions operate in Africa in general and South Africa in particular are likely to impede the ability of service-learning to accomplish perfect justice in Rawls' direction even if the initial intention is to do so. As such, this paper focuses on a partial justice by looking at what is possible to achieve in through service-learning. The paper draws on empirical evidence from the broader study that focused on the role of service-learning in promoting human development at one South African university.

The paper is divided into five sections. The first section is the review of literature that focuses on i) John Rawls' notion of justice, service-learning within John Rawls' notion of justice, and ii) the pitfalls of service-learning when approached from Rawls' notion of justice. The second section deals with an analysis of partial justice as an ideal framing and outcomes of service-learning. The methodology for this study is presented in section three. The fourth section provides findings and discussion. The last section concludes the paper.

Literature Review

John Rawls' notion of justice

In his path breaking book 'A Theory of Justice' (1971: 112), philosopher John Rawls equates justice with fairness, which can be achieved if: A group of mutually disinterested individuals, unacquainted with their places in society, if given the charge to divide up society's resources, would inevitably arrive at the creation of a just society that would include an equitable distribution of rights and responsibilities and opportunities for self-development for everyone.

At the nerve- centre of Rawls' conception of justice are two principles, namely i) each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive basic liberty compatible with a similar liberty for others, and ii) social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both a) reasonably expected to be everyone's advantage; and b) attached to positions and offices open to all. An interpretation of these two perspectives is that 'the primary subject of the principles of justice is the basic structure of society, the arrangement of major social institutions into one scheme of cooperation' (Rawls, 1971: 47). For Rawls, justice is the virtue of social institutions, and no matter how efficient and well-arranged these institutions are, they must be reformed or abolished if they are unjust (Rawls, 1971). In this context, advancing justice depends on the existence of perfect social institutions, which are responsible for distributing the fundamental rights and duties or what Rawls describes as 'primary goods' efficiently.

One of the central features of Rawls' conception of justice is that of setting up just institutions and requiring that people's behaviour comply entirely with the demands of proper functioning of these institutions (Sen, 2009; Johnston, 2011). The emphasis on identifying and creating just institutional arrangements for a society points towards two perspectives. One is identifying a perfect justice2 rather than relative comparisons of justice and injustice. A major weakness of this position is that it disregards comparing feasible societies in the process of promoting justice. Thus, it 'may fall short of the ideals of perfection' (Sen, 2009) as it does not take into account non-ideal conditions that impede the ability to achieve full justice (Johnson, 2011). In essence, 'if justice is fairness, then a fully fair and just society will intuitively be one in which individuals and institutions strictly comply with fair principles' (Arvan, 2014: 97). Two, the transcendental3 institutionalism emphasises the centrality of getting institutions right rather than the actual societies that would ultimately emerge in the process of promoting justice (Sen, 2009). In this way, the second premise forecloses the importance of non-institutional features such as actual behaviours of people and their social interactions (Sen, 2009). Thus, this articulation of perfect justice is labelled as hypothetical and experimental (Srivastav, 2016). In this context, an important question to ask is 'can service-learning contribute to social justice in line with transcendental institutionalism claims for perfect justice?'

Locating service-learning within John Rawls' conception of justice

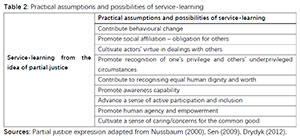

The narratives about service-learning for social justice take a radical and progressive view of disrupting and deconstructing systems and structures that perpetuate inequalities. The common thread that runs through this cluster of literature is that service-learning advances social justice in several ways. Some argue that service-learning awakens participants to injustice and catalyses collective action (Britt, 2012; Mather & Konkle, 2013; Johnson, 2014). Others reveal that it involves working towards distributing power amongst all service-learning actors, developing mutual and reciprocal relationships in the classroom and in the community, and working from a social change perspective (Mitchell, 2008). In the more recent past, a social justice model of service-learning has been heralded for elevating community members' voices and agency (Mtawa & Fongwa, 2020) and allowing participants to reflect on their privilege and diverse ways of being and thinking (Halverson-Wente & Halverson-Wente, 2014; Mtawa & Wilson-Strydom, 2018; Mtawa, 2019). In the main, the ways in which service-learning is articulated and its contribution to social justice is largely embedded in John Rawls' perfect justice. The table below provides a summary of the assumptions of service-learning and its perceived contributions to social justice in the direction of John Rawls' perfect justice.

Adding to the above table is Arvan's (2014) interpretation of Rawls' three distinct assumptions of an ideal theory of justice. For service-learning to advance the assumptions outlined in the above table, it would need to:

a) operate under the conditions in which people are generally able and willing to cooperate under common social-political institutions,

b) operate in society or communities that conform to a principle of equal basic liberties and conditions under which the full exercise of basic liberties can be enjoyed, and

c) operate in reasonably favourable conditions, which often do not exist.

The above assumptions indicate the complex issues that service-learning is expected to address when framed as a contributor of perfect justice. However, those who link service-learning to issues of social justice in Rawls' sense, their expectations are largely hypothetical rather than realistic. This leads us to the pitfalls of locating service-learning within Rawls' conception of perfect justice.

Pitfalls of John Rawls' notion of justice and a case for partial justice

A theoretical framing of service-learning

John Rawls notion of justice has attracted some criticisms. One of the critics is Amartya Sen. In his seminal book The Idea of Justice, Sen (2009) questions what he calls the 'transcendental institutionalism', which focuses on perfect justice through creating right and just institutions and behaviour. Simply put, Sen criticizes Rawls' idea of perfect justice by arguing that is not about the nature of perfect justice, rather about how we can proceed to address the question of enhancing justice and removing injustice. In the quest for an alternative idea of justice, Sen argues for a 'realization-focused conception of justice', which is a result of factual institutions, actual behaviour, and other influences. In Sen's sense, rather than conceptualizing justice in terms of certain institutions arrangements, we should also focus on what emerges in society, the kind of lives people can lead given the institutions, rules and actual behaviour that affect human lives. In other words, Sen is of the view that institutions and structures in society are not perfect and the quest for social justice should take into account these limitations. In defending his position, Sen uses the notion of 'partial theory of justice' to refer to incomplete justice or non-ideal justice (Sen, 2009). For Sen, it is not about perfect justice; rather, we should strive toward removing remediable injustices around us, which we want to eliminate, with the ultimate goals of striving towards the perfect justice. Broadly, Sen's conception of justices aims at exploring ways and means of making the world less unjust.

Using Arvan's (2014) interpretation, there are other three potential pitfalls of approaching service-learning in line with Rawls' ideal justice. First, it assumes that everyone has equal obligation to prefer a fully just society and the elimination of any and every injustice (natural duties of justice). Second, not everyone lives up to the obligation of natural duties of justice and sometimes even some people even oppose the realisation of a just society. Third, given the structural arrangements, there is no fair treatment of all. For Arvan (2014), these are three non-ideal elements, which reflect the context in which service-learning exists. With service-learning operating in contexts which are different from these three dimensions, a partial justice approach seems to be an ideal framing.

In an ideal just society, all members of a society would have their basic needs and liberties guaranteed. They would have equal chances, voices, autonomy, and opportunities to actively participate in social, cultural, political, environmental, and technological activities. This, however, would depend largely on building and having perfect, right, and just institutions, practices and behaviour that ensure equality of opportunities. However, the reality is that we live in an imperfect or non-ideal world imbued with structural, systemic, and enduring inequalities. In fact, we live in a society made up of structures that are responsible for entrenching different forms of inequalities and injustice. Service-learning finds itself at the crossroad where on the one end of the spectrum it operates in the context of complex and imperfect institutional arrangements as well as structural and systemic inequalities. On the other hand of the spectrum, service-learning is expected to dismantle the very structures, institutions, practices, and behaviour that result in unjust society and imperfect institutional arrangements.

Given the conditions under which service-learning operates and the difficulties it faces to advance perfect justice, promoting partial justice appears to be the likely possibility (Mtawa & Wilson-Strydom, 2018). For the purpose of this paper, partial justice refers to incomplete justice or non-ideal justice, geared towards removing remediable injustices around us with the ultimate goal of striving towards perfect justice (Sen, 2009). In other words, partial justice in service-learning would entails possible outcomes that can be realised given the existing conditions. As Sen (2006: 226) points out, 'a partial ordering can be very useful without being able to lead to any transcended identification of a fully just society'. The use of partial justice in service-learning aligns with Sen's (2006: 226) view that 'even without the possibility of setting up some of these [right] institutions, it is, of course, possible to advance justice or to reduce injustice to a considerable extent'. Using Nussbaum's (2000) framing, it is about striving to reduce and remove inequalities in people's capabilities4 to function in ways that are elemental to such a life. Acting justly within partial justice framework would then involve six objectives.

Paraphrased from Drydyk (2012: 33), they include:

1) reducing capability shortfalls,

2) expanding capabilities for all,

3) saving the worst-off as a first step towards their full participation in economy and society,

4) which is also to be promoted by a system of entitlements protecting all from social exclusion, while

5) supporting the empowerment of those whose capabilities are to expand, and

6) respecting ethical values and legitimate procedures.

For service-learning, partial justice seems to be the realistic outcome given that it offers a glimpse of possibilities for promoting some elements of justice. Of critical relevance to framing service-learning from a partial justice theory is the longstanding criticism that if gone unexamined, service-learning may perpetuate the very injustice and inequalities it sets out to dismantle (Butin, 2010; Preece, 2016). Stith, et al. (2021: 9) are even more critical as they argue that 'enactment of social justice within service-learning is complicated because it has not been a universal aspiration or intended outcome among practitioner-scholars'. While several critics are of the same view as Stith et al., it is necessary to caution against dismissing the contribution of service-learning to achieving some form of justice even in some smallest ways. However, if we were to take a partial justice approach, some questions emerge. These are (i) what would be service-learning outcomes that can enable us to remove remediable injustice around us? (ii) how would that service-learning look like?

The table below provides some illustrative examples of what can be considered to partial justice outcomes of service-learning:

The assumptions and possibilities outlined in the above table align with those who criticise service-learning for its inability to transform structural unjust systems and practices (Mitchell, 2008; Stoecker, 2017). Central to these assumptions and possibilities is that they might not lead to creating perfect justice, rather they point towards the direction of achieving some form of justice.

Methodology

This paper is based on a qualitative study that was undertaken at a select South African university. The bulk of the evidence supporting the claims for partial justice outcomes of service-learning is based on data collected between 2014 and 2015. The data collection involved interviews with lecturers and university's administrators, focus groups with students and community members and documents analysis of service-learning module descriptions. From the interviews and focus groups, the intention was to obtain the perspectives of lecturers, students and community members on the approaches, benefits and lived experience of their involvement in service-learning. The analysis of documents was intended to capture the articulation of goals and benefits of service-learning modules. The lecturers, students and documents were from the Faculty of Health Sciences and Faculty of Humanities.

The interviews involved sixteen (n-16) lecturers and four (n-4) university administrators responsible for service-learning. The interviews were focused on four questions:

1. What is the dominant model or approach used in service-learning at this university?

2. What opportunities does service-learning provide to participants?

3. What are the intended benefits of SL to the university and communities?

4. How are communities' dynamics and conditions reflected in and influence service-learning?

The four (n-4) focus groups each with twelve students from the Faculty of Health Sciences and Faculty of Humanities were guided by the following questions:

1. What kind of activities do you undertake in communities?

2. How would you describe your contribution to communities through service-learning?

3. How does service-learning experience impact or benefit you?

The two (n-2) focus groups with community members were centred on the following questions:

1. How can you describe your involvement in service-learning?

2. Do you think engaging with students/lecturers in service-learning has any value or impact in your life and community?

3. What do you think could be done for service-learning to have lasting impact in communities?

In terms of documents analysis, documents related to four service-learning modules offered in the Faculty of Health Sciences and Faculty of Humanities were analysed. A special attention was given to the articulations of the module descriptions in terms of the intended benefits of service-learning. In all cases, the data was collected after ethical clearance was granted by the university involved in the study (X-EDU-2014-055).

The data collected through interviews, focus groups and documents analysis were transcribed and manually coded into themes and sub-themes (Saldana, 2009). Specifically, the analysis involved an interactive process, which comprised of coding of patterns; building categories of meaning through aggregation of coding elements; and integrating diverse categories into themes (Babbie, 2007). Both deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis were employed whereby some themes emerged from the raw data while analytical tools (partial justice elements) guided the development of other themes. The data analysis paid a particular focus on the articulated and perceived approaches and benefits of service-learning across sources of data. There was no difference in terms of articulation of the benefits of service-learning between humanities and health sciences participants and documents. While the analysis looked at the benefits of service-learning broadly, a closer look at the data pointed towards partial outcomes, as evidenced in the following findings.

Findings and Discussion

The thematic analysis of the data revealed four findings that can be glossed as key elements of partial justice outcomes of service-learning. These include (1) advocacy, activist works, and awareness promotion between and among actors; (2) access to skills and knowledge; (3) fuelling a sense of empowerment and self-help; and (4) Ubuntu, affiliation, and diversity literacy. Central to these findings is that they are critical to service-learning particularly in contexts such as South Africa that is bedecked by unjust structural conditions, which impede its transformative potential in a perfect justice fashion. As such, achieving partial outcomes is better than doing nothing and it enables us to address remediable and intolerable injustice' around us (Sen, 2009). The findings below are examples of service-learning outcomes, which are largely at partial level and were common across the data gathered and transcribed.

Advocacy, activist works, and awareness promotion

One of the overlooked contributions of service-learning is its ability to allow participants (actors) to be involved in advocacy and activist work as well as raise awareness of different social, political, economic, environmental, technological and health issues in communities. In this study, students appreciated that service-learning provided opportunities for them to provide alternative solutions to some issues facing community members mainly. The students' voice with respect to advocacy are in line with Berke, et al. (2010: 13) 'the underlying principle of advocacy is a desire to make a difference by improving policies and practices as well as specific behaviour'. Some of the advocacy work that students pointed out are those related to women abuse, information sharing and raising awareness:

I have been involved in community service-learning at the police station advocating against women domestic abuse. The purpose of service-learning is that it helps you link people with resources, make them aware of resources that are available in their immediate environment because people are so overwhelmed, and they do not see what is around them. So, our project is called 'victim empowerment'. So, we increase women's awareness of their rights and make them aware that there are places they can go when experiencing abuse (Students - focus group).

The above excerpt captures elements of obligation for others, recognition of equal human dignity and worthy, and awareness but at a partial level. The advocacy work undertaken by students is valued by community members. When asked what they think students should focus on when they come to their community, one community member stated:

They can focus on issues of gender abuse, alcoholism, and counselling. Students doing psychology can help in these areas. Because we have OT (occupational therapy), medical students, nursing education students, sports students, we don't have law students, but they can do a lot. (Community member).

The above excerpt provides a classic example of the advocacy work related to issues of gender-based violence (GBV) as well as inequality in terms of access to resources and information. The advocacy work highlighted by students and community members may not address the deep-seated root causes of GBV issues and enduring inequalities in South Africa; however, advancing women rights and linking people with possible resources are the demonstration of partial outcomes, which can lead into addressing some injustice though in a smallest and positive ways.

Similarly, students reflected on the advocacy work aimed at mentoring underprivileged children regarding educational issues. A study of service-learning in Canada by Patel, et al. (2021) found that mentorship is one of the key components to advocacy-related programming focusing on high school students and at-risk youth, which impact health decisions and self-esteem. Consider this excerpt:

We started this group called 'Chosen Generation'. We realised that we are just students ourselves and we can't do much. We can't buy food each and every family every month but the least we can mentor children who are from less privileged backgrounds. Their parents do not work because they didn't go to school. So, they can't really encourage the child about education because they don't know the importance of education. So, we realised that it's all about mentoring the children and not just doing it once when it is close to final exams (Students - focus group).

With the existing socio-economic inequality coupled with a divided education system in South Africa (Spaull, 2013; Letseka, 2014), advocacy work focusing on addressing education inequality through service-learning though partially appears to be a useful project. While education inequality in South Africa is a structural and systemic issue, what students do in communities through service-learning may contribute to removing some forms of inequality without creating perfect institutions and practice in the education sector. A good example is described below:

I started an organisation last year because I saw a gap between learners who go to public schools and those who go to the multiracial or model C schools. When they get to tertiary level the adaptation skills are not the same. So, we go to these schools in the locations5 and we give talks to try to equip them with life skills and also academic skills. We have tutors who help them with home works and other things during weekends. We try to find bursary opportunities that are available and to give information on how to apply for bursary because most of them feel that because parents don't have money after I finish matric there is nothing they can do. Many think that maybe they will need to go find employment in construction sites. So, we are trying to bridge that gap between public schools and model C schools (Students - focus group).

From the above excerpts, there are clear evidence to support that service-learning provides a fertile space for participants to understand, be aware of and take actions to address critical issues in society. For students, it allows them to practice advocacy and activist work through which they apply their knowledge, skills, talents, and different forms of capital (resources) with the hope of addressing social problems. The work students do in communities may raise awareness, inspire action on community issues and galvanise support for community cause. A case in point is students' focus on supporting the less privileged to have access to equitable education. The advocacy and activist work students are involved in appears to be at the level of removing possible and remediable inequalities. As such, the underlying structural inequalities and their root causes remain, thus, impeding the building of perfect justice.

Fuelling a sense of empowerment and self-help in communities

One of the criticisms levelled against service-learning field is that it positions community members as disempowered individual who lack control, agency and ownership of the activities that affect their lives (Mtawa, 2019). The analysis of the data reveals that community members are not disempowered, rather they have limited opportunities and access to an enabling environment and conditions that allow them to realise their potential. As such, what is needed in communities are programmes such as service-learning that open up opportunities for community members to actively participate in productive and valued activities. If we take it from a partial justice standpoint, service-learning makes significant contribution to stimulating a sense of empowerment and self-help capacity for community members. The voices of lecturers and students who participated in this study pointed towards some dimensions, which promote community members' ability to act and bring about change for themselves. The views of some lecturers are captured as follows:

Through my students, young people especialy from disadvantaged backgrounds are in a position to dream big, they are in the position to see beyond their poverty or poor circumstances. I am not for giving out food and giving out money and al that, but I would like these learners from underprivileged backgrounds to be in a position to dream and I believe that is how we can, not end poverty but getting to address the issue of poverty. We are empowering kids in poor communities (Service-learning lecturer).

This excerpt emphasises the centrality of creating enabling opportunities for people to dream 'aspire', to do things for themselves 'self-help capacity', and removing the dependency mentality in communities. Similarly, another lecturer stated that:

[...] I love uplifting the community and empowering people so that they can help themselves. Sharing knowledge is important in helping people to help themselves you can go into health dialogue and where they can apply what you shared but you also understand from them problems that they have (Service-learning lecturer).

The lecturers' perspectives are in line with what students think that they can and are doing in promoting a sense of empowerment and aspiration in communities. Of most relevance is that students do not describe service-learning as merely academic credit bearing exercise, rather they see it as an opportunity to contribute to social change in some ways. Students appears to understand empowerment in Davis and Wells' (2016) sense of the ability of community to be the author of their own lives. For example, one student expressed that:

For me going back to the purpose of service-learning I would say it is not about you, it is about creating opportunities for the communities that even when you leave at least there is something that they can hold onto. Empowerment is one of the things that you can bring, you are not going to teach them but just making them aware of their inner potential. So, service-learning is about trying to come up with solutions to issues, you don't solve problems for them. So, you help them to move forward for themselves (Students - focus group).

There was a view from students, which mirrors closely with the perspective that 'students from regional, rural and remote backgrounds can see stories and examples of those from similar backgrounds who have successfully navigated the journey to and through tertiary education' (Heberlein, 2020: 23). The view of students acting as conduit to aspire young people to realise their full educational potential was dominant during the discussion. This perspective is apparent in this excerpt:

Making it to the university I am a role model to some children back home because they are going to look up to me saying if I made it, they can also make it. I am from a small village in Lesotho, so when we do service-learning, and they see me from the university they get inspired. I do not go house to house to teil them what I do but by just sharing my dreams and hustles they get inspired (Students - focus group).

The above view was supported by other students who proposed that:

We can do something with regards to empowering youth. People from higher education can come and encourage young people and help them apply for bursaries if they qualify. We should empower people to go to school It is quite upsetting because sometimes I feel I can't do much. I am there and people say they need jobs can you help us, and you promise whatever you can but in your heart, you know it's impossible (Students -focus groups).

Children are born, they go to school, after finishing school nothing happens, its only survival of the fittest. I really think we can do much, but it doesn't necessarily have to be about material things. There are other things, for example, maybe career wise, we can go there and encourage so that it's not only a matter of being given food every month and you are not doing anything (Student- focus group).

The above example of students' voices points toward the dimensions of empowerment and aspiration that are or can be generated in and through service-learning. However, one can argue that the kind of empowerment and aspiration highlighted seems to be at the level of partial outcomes. Rather than creating empowering and aspiring conditions for community members to alter unjust structures and practices, what is highlighted in the above illustrative examples are some forms of service-learning contribution, which are limited to a small change. The evidence show that service-learning can only achieve partial outcomes, which cannot lead to perfect justice. In other words, empowerment and aspiration fuelled through service-learning are geared towards making some form of change but not transforming the unjust conditions in communities.

Stimulating a sense of empowerment and ability to aspire are linked to opportunities for learning and access to skills and knowledge, as evidenced below.

Learning and accessing skills and knowledge

One of the major challenges facing students and community members in a contemporary South African society is a lack of access to skills and knowledge, which are critical in employability and addressing basic forms of injustice in society. An analysis of the data shows that service-learning provides opportunities for participants to learn and have access to skills and knowledge that can only be inculcated and shared in spaces such as service-learning. Of particular relevance in this theme is that the skills and knowledge developed and exchanged in and through service-learning can contribute to what is articulated in the South African National Development Plan - Vision for 2030 as the creation of opportunities and stimulation of hopes for a better life. Linking skills and knowledge to employment opportunities and active participation in socio-economic activities are common threads that run through service-learning course descriptions:

Community members are able to apply for better job opportunities due to the training they received in computer literacy. They also receive a certificate on completion of the course. In this manner, some members of the community are able to create their own job opportunities and to provide for themselves (Computer Information Systems, RIS242).

Members of the community participating in this project experience a greater understanding of economics, which wil lead to better decisions regarding personal money management. Their self-knowledge is also enhanced, and economic literacy improved (International Economics, EKN314).

The community, including learners, their teachers and family members, gain knowledge and skills on how to manage health-related problems (Nursing Theory & Nursing Practical, VRT116/123, VRT 114/124).

The above examples of service-learning course descriptions illustrate the ability of service-learning to generate basic skills and knowledge that are often missing in communities. The skills and knowledge underlined in the select excerpts have the potential to address some forms of inequalities in communities. Some of these skills and knowledge summarised from the above extracts include:

• Needlework - income generation

• Computer training and literacy - ability to apply for jobs

• Economic knowledge - better financial management

• Health education and skills - better management of health-related problems and enhanced access to health information and services

Central to the skills and knowledge intended to be shared during service-learning, are the voices of community members, which affirm the need for such outcomes in communities. Reflecting in line with Agupusi's (2019) factors that determine educational achievement and intergenerational inequality, one community member expressed that:

What I value in service-learning is seeing our children in community gaining more knowledge and changing their life. This can help them to study and become better people in the future doing things for themselves and not depending on their parents or government. What kills the dreams they have is their backgrounds. They think that their background is what can determine their future not knowing that there is more that they can do and be able to sustain themselves and become better people in the future (Community member).

Another community member touched on elements of service-learning that have the potential to addressing unemployment, which is increasingly becoming a wicked social problem in South Africa and beyond. The alternative solutions that can be generated through service-learning might not be able to disturb or change the underlying and complex causes of unemployment. However, as expressed by a community member, service-learning can offer some ameliorative changes that affect community members' lives though in the smallest way:

Unemployment is the big problem in this community and there were people from the university who used to come during service-learning and train people on small businesses and entrepreneurs, but they stopped. So, educating people so that they make a living for themselves and remove poverty and unemployment and giving people the purpose. I think that is where the university through service-learning can help a lot by giving skills. Some people here registered their businesses, but they died because they couldn't manage them. There is need for skills like management skills on how to manage business and what procedures to folow and have access to information such as where to go to get funding for small businesses and connect them with the people who can help them to sustain their business and their small enterprises (Community member).

During discussions with students, they also mentioned several activities that they do with communities and their potential impact. Although the activities highlighted can be described as elementary, they might have an important contribution to promoting well-being in communities. Consider the examples of doll making and gardening in the following excerpt:

[...] we taught them how to do [i.e., make] the doll[sj][...] we actually found out that she (the mother) had made more dolls and she also showed her friend how to make them. She had made them with different materials. When we got there, she had made six dols, they were different dols and different characters and she said she wil be seling some. So, we were really proud that we taught her something. [...] They had no garden and did not know how to do it properly, so we taught them the steps how to make one (Students - focus group).

The above excerpts are illustrative examples of possibilities of service-learning in contributing to skills and knowledge particularly for community members. The outlined skills and knowledge may have little transformative impact with respect to addressing social injustice. Nonetheless, they are likely to advance some elements of partial justice in communities. A classic example is income generation through selling dolls and gardening, which cannot address socio-economic inequalities and create a just society, but it can enable communities to have some source of income.

Ubuntu, affiliation, and diversity literacy

South Africa is characterised by a complex, diverse, and unequal society. This is due to the complex historical legacies of apartheid, ethnicities composition as well as the social, political, cultural, and economic arrangements and practices that have shaped South African society post 1994. Such characterisation plays as both strength as well as a weakness in determining the social fabrics and cohesion. A number of policy frameworks and programmes have been enacted in an attempt to build and consolidate what is often referred to as a 'rainbow nation'. While much more is needed, service-learning seems to serve as a repertoire through which elements such as Ubuntu,affiliation, networks and understanding and respecting diversity can be promoted among and between service-learning actors. These are some of the outcomes articulated in service-learning modules. For example, through these suggested modules:

Through service-learning, community members are enabled to participate in a variety of recreational activities. Through participation in the games day, various communities are introduced to each other. Social interaction and community integration is facilitated, and it is evident that these events help to foster a greater sense of tolerance and respect among different communities (Clinical Occupation Therapy - KAB 205).

The community members also develop interpersonal bonds with the students and the University staff who then become included in their supportive social networks (Social Research and Practice - SOS324).

The above excerpts emphasise the centrality of participation, interaction, tolerance, respect, and bond (affiliation), which are key ingredients in fostering Ubuntu and building strong social ties across the intersectionality of race, gender, culture, social and economic status, geographical location, and sexual orientation (Mtawa, 2019; Ngomane, 2019). An important element observed in the analysis of the data is that service-learning allows students to think and act in tandem with the above academic course intentions. Reflecting on service-learning experience, students expressed that:

It starts with us building relationships, going out every Thursday and seeing them all the time so that they know you don't just go there and get what you want and then you leave. You want them to know that you are interested in their stories and what they go through. It is about listening to their stories, showing empathy that you are trying to put yourself in their shoes. It is about understanding why they are on the streets and not judging them. People always say can't those ladies [sex workers] find other forms of employment(Students - focus group).

We come from different background[s] and we see things differently. Through service-learning, I learnt that we need to see the way people see themselves and be in their shoes so that we understand what they are going through not just judge them. Through service-learning, I realised that those kids have different challenges and problems and I realised that they have so much strength, skiils, and talents (Students - focus group).

Of critical importance in the above excerpt is the comment on trying to put yourself in their shoes, which can be linked to the use of imagination with knowledge and actual experience to overcome the limitation of our own narrow worldviews (Nussbaum, 1998; Von Wright, 2002). What students are arguing for is similar to Nussbaum's (1998) three capacities that ought to be cultivated in and through education:

1) the ability to critically examine oneself and one's traditions,

2) the ability to see oneself not only as a member of a local group but as linked to all other human beings, and

3) the ability to put oneself in another person's shoes and to understand their emotions and desires, in other words, to exercise narrative imagination.

Related to the above capacities is the ability of people and specifically students to understand and respect diversity particularly in a complex and diverse South African society. Such is one of the outcomes of service-learning experienced and appreciated by students:

I learnt the skill of entering into other people's world. I am not Sotho; I am Zulu so it was hard for me I couldn't speak English I had to learn to say something in Sotho. That is really important that when you enter into communities you must understand them it is not about you, it was not about me it was about people, so I had to learn to speak even a bit of Sotho. I also had to learn how they do things in their way so that they feel comfortable in expressing themselves (Student - focus group).

Despite the positive outcomes of service-learning in relation to fostering elements of Ubuntu, affiliation and diversity literacy, these capacities are very much at partial level. The above highlighted benefits of engaging in service-learning can contribute to behavioural change and recognition of human dignity and worth in terms of how diverse people engage in society. Nevertheless, service-learning alone cannot lead into dismantling the structures and practices that perpetuate deep seated forms of racism, discrimination and cross-racial/ethnic differences (Mtawa, 2019) in order to create a perfect justice and humane society.

Conclusion

This paper sets out to interrogate the application of the concept of social justice in service-learning context. The crux of the argument was that social justice is loosely interpreted and applied in service-learning with the assumptions that service-learning can contribute to advancing justice in the direction of John Rawls' perfect justice. There are assumptions that through service-learning, actors are able to engage in activities, which lead to perfect justice whereby institutions and social arrangements provide equal opportunities for all. The dominant view is that service-learning advances social justice in the direction of creating a perfect and just society. However, this paper challenges and interrogates the ways in which service-learning is described as strategy to advance social justice in perfect sense. The paper draws on an idea of partial justice, which while acknowledging the importance of creating perfect justice, it emphasises the centrality of removing possible and remediable injustice around us. Four main findings emerged, namely advocacy, activist works, and awareness promotion, fuelling a sense of empowerment and self-help in communities, learning and accessing skills and knowledge and Ubuntu, affiliation and diversity literacy emerged. A common thread that runs through these findings is that service-learning has the potential to contribute to outcomes, which are limited to advancing partial justice in terms of removing possible injustices in communities. The articulation of the practices and intended outcomes of service-learning in this paper is an indication that even actors such as academics, students and community members are aware of the limits and possibilities of service-learning.

As shown in this paper, there are complex conditions and structural issues, which impede service-learning from advancing perfect justice. In South African context, these include but not limited to historical legacies and current economic, social, cultural, political, educational, and geographical locations. In this way, the limitations of service-learning to promoting perfect justice are likely to be much more common in South Africa given its unjust and unequal society. Within these complexities, evidence in this paper indicate that service-learning seemingly fails to disrupt structural and systemic inequalities. Nonetheless, the contribution of service-learning, as evidenced in this paper cannot be underestimated. Opportunities to undertake and engage in advocacy, activist works, and awareness promotion, fuelling a sense of empowerment and self-help in communities, learning and accessing skills and knowledge, and cultivating Ubuntu, affiliation and diversity literacy are critical to South African society and beyond. Thus, service-learning actors must build upon and draw lessons from possible outcomes such as those highlighted in this paper. By doing so, they might be in a position to develop and practice service-learning initiatives, which eventually contribute to advancing perfect justice.

Acknowledgement

This research was made possible due to the funding provided by the South African National Research Foundation Research Chairs Initiative [Grant number U86540].

Author Biography

Ntimi Mtawa is a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of the Free State. Mtawa's academic and research interests cover areas such as education, higher education and human development, knowledge production, community engagement, pedagogies, and citizenship. Mtawa has published widely in international journals and is an author of two books.

References

Agupusi, P. 2019. The effect of parents' education appreciation on intergenerational inequality. International Journal of Educational Development, 66: 214-222. [ Links ]

Arvan, M. 2014. First steps toward a nonideal theory of justice. Ethics & Global Politics, 7(3): 95-117. [ Links ]

Babbie, E. 2007. The Practice of Social Research.Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Berke, D.L., Boyd-Soisson, E.F., Voorhees, A.N. & Reininga, E.W. 2010. Advocacy as service-learning. Family Science Review, 15(1): 13-30. [ Links ]

Bialka, C.S., Havlik, S., Mancini, G. & Marano, H. 2019. 'I Guess I'll have to bring it': Examining the construction and outcomes of a social justice-oriented service-learning partnership. Journal of Transformative Education.https://doi.org/10.1177/15413446198435

Boyle-Baise, M. & Langford, J. 2004. There are children here: Service learning for social justice. Equity & Excellence in Education, 37(1): 55-66. [ Links ]

Britt, L.L. 2012. Why we use service-learning: A report outlining a typology of three approaches to this form of communication pedagogy. Communication Education, 61(1): 80-88. [ Links ]

Butin, D.W. 2010. Service-Learning in Theory and Practice: The Future of Community Engagement in Higher Education. New York: Palgrave McMillan. [ Links ]

Davis, J.B. & Wells, T.R. 2016. Transformation Without Paternalism. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 17(3): 360-376. [ Links ]

Drydyk, J. 2012. A capability approach to justice as a virtue. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 15(1): 23-38. [ Links ]

Halverson-Wente, L. & Halverson-Wente, M. 2014. Partnership versus patronage: A case study in international service-learning from a community college perspective. pp. 84-109. In Green, P. & Mathew, J. (eds.) Crossing Boundaries: Tension and Transformation in International Service Learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing. [ Links ]

Heberlein, W. 2020. The sphere of influence that university outreach programs have on rural youth aspirations toward tertiary education. Access: Critical Explorations of Equity in Higher Education, 7(1): 22-33. [ Links ]

Hytten, K. & Bettez, S.C. 2011. Understanding education for social justice. Educational Foundations, 25: 7-24. [ Links ]

Jacoby, B. 1996. Service-learning in today's higher education. In Jacoby, B. & Associates (eds.) Service-learning in HigherEducation: Concepts and Practices, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 3-25. [ Links ]

Jessup-Anger, J., Armstrong, M., Kerrick, E. & Siddiqui, N. 2019. Exploring students' perceptions of their experiences in a social justice living-learning community. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 56(2): 194-206. [ Links ]

Johnson, D. 2011. A Brief History of Justice. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Johnson, M. 2014. Introduction. pp. 1-11. In Green, P. & Johnson, M. (eds.) Crossing Boundaries. Tensions and Transformation in International Service-Learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing. [ Links ]

LaDuca, B., Carroll, C., Ausdenmoore, A. & Keen, J. 2020. Pursuing social justice through place-based community engagement: Cultivating applied creativity, transdisciplinary, and reciprocity in catholic higher education. Christian Higher Education, 19(1-2): 60-77. [ Links ]

Lee, K.A. & McAdams C.R. 2019. Using service-learning to promote social justice advocacy and cognitive development during internship. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 12(1): 8. [ Links ]

Letseka, M. 2014. The illusion of education in South Africa. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116: 4864-4869. [ Links ]

Li, Y., Yao, M., Song, F., Fu, J. & Chen, X. 2019. Building a just world: The effects of service-learning on social justice beliefs of Chinese college students. Educational Psychology, 39(5): 591-616. [ Links ]

Mather, P.C. & Konkle, E. 2013. Promoting Social Justice Through Appreciative Community Service. New Directions for Student Services, 143: 77-88. [ Links ]

Mitchell, T.D. 2008. Tradition vs. critical service learning: Engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan Journal of Community Service Leaning, 14(2): 50-65. [ Links ]

Mtawa, N.N. 2019. Human Development and Community Engagement Through Service-learning: The Capability Approach and Public Good in Education. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Mtawa, N. & Wilson-Strydom, M. 2018. Community service-learning: Pedagogy at the interface of poverty, power and privilege. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities. A Multi-Disciplinary Journal for People-Centred Development, 19(2): 245-265. [ Links ]

Ngomane, N.M. 2019. Everyday ubuntu: Living better together, the African way. London: Penguin Random House. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, M.C. 1998. Cultivating Humanity. A Classical Defence of Reform in Liberal Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, M. 2000. Women and Human Development; The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Patel, M., Chahal, J. & Simpson, A.I. 2021. Teaching advocacy through community-based service learning: A scoping review. Academic Psychiatry, 1-10.

Preece, J. 2016. Negotiating service learning through community engagement: adaptive leadership, knowledge, dialogue and power. Education as Change, 20(1): 104-125.

Rawls, J. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Richards-Schuster, K., Espitia, N. & Rodems, R. 2019. Exploring values and actions: Definitions of social justice and the civic engagement of undergraduate students. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 16(1): 27-38. [ Links ]

Saldana, J. 2009. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Schulz, D. 2007. Stimulating social justice theory for service-learning practice. In Calderón, J.Z. (ed.) Race, Poverty and Social Justice: Multidisciplinary Perspectives through Service Learning. Sterling: Stylus, 23-35. [ Links ]

Sen, A. 2006. What do we want from a theory of justice?. The Journal of philosophy, 103(5): 215-238. [ Links ]

Sen, A.K. 2009. The Idea of Justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sen, A. 2000. Social justice and the distribution of income. Handbook of income distribution, 1: 59-85. [ Links ]

Stith, M., Anderson, T., Emmerling, D., Malone, D., Sikes, K., Clayton, P. & Bringle, R. 2021. Designing service-learning to enhance social justice commitments: A critical reflection tool. Experiential Learning & Teaching in Higher Education, 4(2): 9-17. [ Links ]

Stoecker, R. 2016. Liberating Service Learning and the Rest of Higher Education Civic Engagement. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Spaull, N. 2013. Poverty & privilege: Primary school inequality in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(5): 436-447. [ Links ]

Stoecker, R. 2017. The neoliberal starfish conspiracy. Partnerships: A Journal of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement 8(2): 51-62. [ Links ]

Unfried, A. & Canner, J. 2019. Doing social justice: turning talk into action in a mathematics service learning course. Primus, 29(3-4): 210-227. [ Links ]

Von Wright, M. (2002). Narrative imagination and taking the perspective of others. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 21(4): 407-416. [ Links ]

Zajda, J., Majhanovich, S. & Rust, V. 2006. Introduction: Education and social justice. International Review of Education/Internationale Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft/Revue Internationale de l'Education, 9-22.

Submitted: 4 April 2022

Accepted: 15 November 2022

Corresponding author:mntimi@gmail.com

@mtawa_n

@mtawa_n  ntimi6070

ntimi6070

1 Most conceptions of social justice refer to an egalitarian society that is based on the principles of equality and solidarity, that understands and value human rights, and that recognised the dignity of every human being (Zajda, et al., 2006: 9-10).

2 Perfect justice entails perfect institutions, social arrangement and society is a system of cooperation for mutual advantage between individuals.

3 Transcendental is an approach, which is concerned solely with perfect justice without making comparative assessment (Sen, 2009).

4 Capabilities are the range of real opportunities from which one can choose (Sen, 1999, 1993).

5 Locations in South African context refers to areas where working class people reside and often in informal settlements.