Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning

On-line version ISSN 2310-7103

CRISTAL vol.10 n.1 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v10i1.511

ARTICLES

Suitably Strange: Re-imagining learning, scholar-activism, and justice

Dylan McGarry

Environmental Learning Research Centre, The University Currently Known as Rhodes, Makhanda, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Using artworks emergent from my career as a pracademic and scholar activist, I attempt to share a 'tactile theory' of being and doing, that refer mainly to response-abilities (i.e., abilities to respond in accountable ways) in scholar activist educational sociology. I aim to make visible (and tactile) the sometimes-invisible qualities and practices needed for navigating the eroded and dying ecological relations of our generation, as well as warming up and making pliable the heteronormative, capitalist, patriarchal and anthropocentric conventions that are associated with it. In order to warm and sculpt these normative conventions, I argue for the need for 'suitably strange' practice. I present six images and associated prose that aim to optimally disrupt these conventions, towards generative rethinking and embodying learning, scholar activism and justice, and from which I explore a tactile theory, an example and related response-ability for each. I end with a reflection of how these suitably strange artefacts can help us develop a new concept of proactive-cognitive justice or 'justness'.

Keywords: Arts-based Research, Suitably Strange, Scholar Activism, Transgressive Learning.

Introduction

The Suitably strange concepts held within this paper speak to the practical need to make strange1the familiar and normative paradigms that are holding us back from deeper meaningful transformation and change in higher education. As a transgressive researcher and scholar activist2 navigating the eroded and dying ecological relations of our generation, that which is atrophied into heteronormative, capitalist, patriarchal and anthropocentric3 conventions, a disruption is well overdue, particularly in higher education. As an iteratively functioning 'pracademic' (Posner, 2009) who aligns with embodied and grounded collaborative research in the fields of learning, activism and justice, suitably strange action (that being making the familiar, optimally strange for generative learning opportunities) has assisted me in finding new openings, opportunities, dialogues, reflections and eventually approaches and practical wisdoms. In this paper I draw from a generative connective aesthetic (McGarry, 2014) through a set of images and related prose to uncover a nuanced embodied picture of something I am struggling to articulate in words, in written English, and that I am much better at describing through making artworks, stories and creating social encounters. Each image/artifact shared within this paper is connected to a body of work that has inspired my actions in developing suitably strange practice in that liminal space between the academy and justice. This emerges from a yearning for tactile theories/concepts, for what Kulundu-Bolus (2020: 447) calls 'research worthy of my longing' . This paper therefore is a practical and tactile guide to six suitably strange objects that can generate dialogue and thinking around innovative capacities that I feel are needed in responding to the hot mess we find ourselves in. Indeed, many more capacities are needed, but for now, six will do.

Introduction: Suitable Strange artefacts4

The uncanny artefacts5 shared in this paper exist mostly in my mind (although some of them I have evolved into sculptures or social learning processes). I like to think of them as what anthropologist Alfred Gell (1998) might call artefacts of agency. Timothy Morton (2014) inspires me here too, his explorations into "realist magic" where objects are independently intertwined, entangled with world, and in them contain their own sense of being, and relational response-ability. Karen Barad and Daniela Gandorfer (2021) remind us with the help of quantum physics that matter is not dead, but rather make meaning through relational entanglements and assemblages with us, put simply we should refer to matter as 'mattering' instead. Bayo Akomolafe and Alnoor Ladha (2017: 826) help here too by explaining Barad's (2007) mattering further: it is helpful to consider the identity of things/matter/stuff, 'its properties, the features that grant it its 'thingness', are not fixed or inherent, and only emerge in the context of relationship' . They summarise it beautifully: 'in other words, there are no things, just relationships, and these ongoing relational dynamics are responsible for how things emerge' (Ibid: 820).

With this spirit, I introduce six uncanny artefacts that are identifiers of entangled relational assemblages that aim to encourage generative, emergent, and empathetic learning encounters in society. My suitably strange and uncanny artefacts are also metaphors that represent a series of capacities that I have been working in South Africa in collaboration with my mentors Heila Lotz-Sisitka, Reza deWet, Saskia Vermeylen, Shelly Sacks, Injairu Kulundu, Mpume Mthombeni, Kira Erwin, Neil Coppen, Taryn Pereira, Anna James, Leah Temper, Lena Weber, amongst others. These artefacts also have their own relationships with others (humxn and more-than-humxn) and are collectively evolving through encounters and exchanges that have emerged over the past decade.

Inspired by Joseph Beuys' (1977) use of art, shamanic practice, and the enlivening force of aesthetics to make connections between seemingly unrelated phenomena, and to capture the imagination in such a way as to open up new possibilities for connections in ourselves and in our relations, I too use the uncanny artefacts here to speak to the power of the suitably strange, the uncanny, and its capacity to optimally disrupt (Wals, et al., 2009; Macintyre & Chaves, 2017), warm up (Bueys, 1977; Sacks, 1998; McGarry, 2014), and wedge open new ways of thinking, being, doing, and learning in these uncertain times we find ourselves in. Times locked into heteronormative, late capitalist, patriarchal and humxn-centric norms. For me, personally, working as an educational socialist in a South African university in the fields of learning, activism, and justice, I find suitably strange practice (that which is familiar, but strange enough to wake up imagination, reflexivity, and dialogue), assists in finding new openings, opportunities, conversations, reflections and eventually approaches to learning, justice, and activism. I, therefore, am writing in my capacity as academic, but more-so in my capacity as a queer (encultured as 'white') South African gender-non-conforming6 artist and social sculptor7.

Indirectly, I use these uncanny artefacts in this paper to reveal a nuanced embodied and tactile picture of something I am struggling to articulate in words, in written English that is, but am better in making things and creating social spaces/experiences.

Tactile Theory

In 2019, I visited filmmaker Ingmar Bergman's8 home during an artist residency with dark pedagogists9 Stefan Bengtsson and David Kronlid. While familiarizing ourselves with his home, we found Bergman's bedside cabinet, there inscribed in felt pen, were Bergman's dreams. The cabinet replacing a journal. Graffitied against the white painted cabinet we read the phrase: "I miss tactile objects". Deciphering this uncanny artifact's message, I felt a deep resonance and yearning for what Bergman must have scribbled as he awoke from his dream. I would rephrase it somewhat: "I miss tactile theory".

What I mean by this, is I miss the tactile and intimate ways in which I have made meaning with my grandmother, godmother, and friends, who have played the biggest role in making sense of a world through tactile relationality.

Each image/artifact in this paper is connected to a body of work that has inspired my very tactile (stories and meanings that one can be held, felt, smelled, and tangibly engage with as living creative artefacts) and grounded actions in developing suitably strange practice. A practice that has emerged from a longing for tactile theories/concepts. If there are no things, just relationships, then our theories of these relationships need to caress, feel, and touch each other.

My tactile theory has developed through my explorations into visual art, art therapy, arts-based research, social sculpture, participatory theatre, and performance art in my work (see McGarry, 2014). More recently I have been inspired by Erin Manning's (2016) research creation10. These artefacts feel important, important in my work in social learning, activism, and justice, and in particular how it has played a role in transgressive and transformative learning (Lotz-Sisitka, et al., 2015; 2016) and my greater work in decolonizing the role and need for some academics to evolve in higher education into scholar activists. Each offers an insight to what may be useful to the scholar activist in South Africa now, in the decolonizing (theory and practice) of the university and creating 'pluriversities for stuck humxns' (McGarry, et al., 2021: 183). Each of these could be fleshed out more, but are economically shared in digestible vignettes, with references for further immersion. All this is to further aid me in this perilous act of storytelling and meaning making - in times where English is just not enough, and perhaps proxy uncanny metaphors and stories might just cut it. In this paper I unearth a 'tactile theory' and a 'response-ability' for each uncanny artefact. By tactile theory, I describe and contextualize a living theory in a sculptural, metaphorical, semiotic, tactile form (the uncanny artefact), with examples and links to other research. I then offer a 'response-ability', i.e., an ability to respond, which Viv Bozalek (2020) refers to an accountable (responsible) and respon-sive (response-able) approach to research. I originally came across this term from Shelly Sack's (2011c) where she saw response(ability) as a set of sensitivities and capacities that are intuitively developed through experiential learning and phenomenological encounter (see McGarry, 2014).

The uncanny artefacts explored

Tactile theory 111:

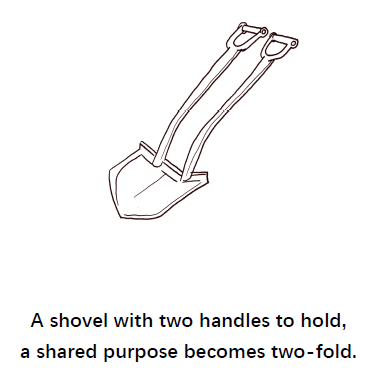

Co-defining matters of concern

The spade with two handles is inspired by an artwork developed by Joseph Beuys (1965) and speaks to solidarity and co-defining 'matters of concern' (Latour, 2004; Lotz-Sisitka, et al., 2015; 2016) together as fundamental aspect of how we should approach sustainability, environmental justice12 , transformation, and development. Co-defining these concerns is simply to empathetically listen to what people and the more-than-humxn world are concerned with. What is pressing on their souls and their life worlds? It is to collaboratively unearth together (hence two handles) how we may be of service to their plight, to the context and reality of the hot mess. Co-defining matters of concern comes from Bruno Latour (2004) alternative to 'matters of fact'. It is to listen, to empathize, to create spaces to immerse ourselves in each other's contexts, to dig into each other's knowing(s). We are digging with two handles into the muck. We dig to 'stay with the trouble' as Donna Haraway (2016) puts it, to empathize with the hot 'stinky mess' (McGarry, et al., 2021) of our moment, of our place, of our situation. To hear and listen to what is there, without judgement, but with empathy. To listen to what is of most concern to people, to a place, to the more-than-humxn community in this context. We can't move forward in any direction until we unearth concerns, together. This is our starting point.

Example - Ulwembu: In our work in Ulwembu (Coppen et al, 2018), an Empatheatre (www.empatheatre.com) production which explored street level drug addiction in the city of Durban South Africa, we began with co-defining matters of concern. We spent two years immersed in the contexts of street level drug users, the police, social workers, medical professionals, clinic staff, sociologists and harm reduction NGO practitioners. Working with a team of 6 bilingual (English/isiZulu) speaking actors led by Mpume Mthombeni (that I trained in ethnographic practice) we conducted actively empathetic and solidarity building research across these very disconnected social systems. Through this process the wider team, led by writer/director Neil Coppen and myself, reconstructed these worlds into an entangled and narrative that laid out the co-defined concerns of these very different communities. We were not attempting to harmonise, or making 'pretty' these narratives, but become comfortable in the cacophony of the problem. These were then empathetically explored across ideological, social, economic, race, and class divides, and played back to the storytellers through immersive theatre.

Response-ability - Ethnographic practice: Unearthing concerns, is often a process of unearthing stories. Stories shape the world, and in turn we shape the world through stories, as Haraway explains: 'it matters what stories, story stories' (2016: 35). Co-defining concerns asks of us to become story-listeners before we become storytellers. Here we have a great responsibility to the people, places, and things we are empathizing with, and with the concerns that are being surface. With our figurative two-handled spade, we must be attentive to the reality that we are surfacing plural (often paradoxical) stories (often times speaking to the same phenomenon) from different perspectives. Developing a sound ethnographic practice does justice to their verbatim and contextualized voice. I have learned to take note of my own emotional and intellectual response stories I am hearing, as well as being careful to describe the context of the person telling the story. I have also found it helpful to find critical friends who can help me make meaning and map out the stories, noticing where stories resonate and when they clash, and echo these stories back to the ones who initially shared them, and then I listen carefully to their response, i.e. I have learned to listen actively (McGarry, 2014).

Tactile theory 2:

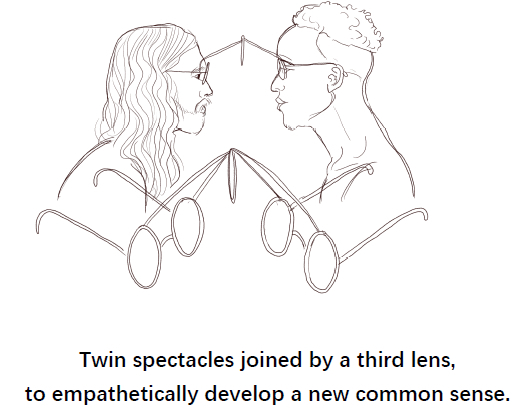

Active Listening

The three-eyed spectacles represent the careful active attentiveness and focus we must maintain in our empathy. To look and feel into what is not there, what is spoken, what remains unspoken and what still needs to come. Through the eye lenses we can see with our eyes, but the metaphor of a third lens, a lens that feels into the personality of the situation (Biko, 1978: 48) and that assists us with thickly imagining and describing that which is not obvious at first sight. Here empathy is active, and engaged (McGarry, 2014), we deepen our capacities for empathy using new ways of seeing, and new ways of representing how we empathize. I made these spectacles and created a social sculpture with performance artist Sizo Mahlangu. We called the project "III", speaking to the three capacities needed for building empathy: 1. Attentiveness, 2. Intuition, and 3. Imagination (McGarry, 2014). It aims to allow two people to sit with each other intimately holding each other in their minds eye, through their mutual 30 min gaze. Somewhat like Marina Abramović's the "Artist is Present" performances13 but with an extended uncanny artefact, or 'instrument of consciousness' (Sacks, 2007) that warms up and aids the process of holding empathetic eye contact. The process is a phenomenological (Husserl, 1929 in Abram, 1996) exploration into holding a mutual gaze, and to be held in empathetic attentiveness using the tri-spectacle instrument. It was a collaborative exploration into how much we can come to know of another through actively 'being with' each other, and communicating without words.

Example- Earth Forum: In my doctoral study entitled 'Empathy in the time of Ecological Apartheid14: A social sculpture practice-led inquiry into developing pedagogies for ecological citizenship' (McGarry, 2014), I explored Joseph Beuy's concept of thought as a sculptural material. In this case I examined empathy as something we can sculpt. This led to the collaborative social Sculpture project: Earth) Forum that I developed with Shelly Sacks (McGarry, 2014) as well as the Climate Train project (McGarry, 2015), which housed the Earth Forum as it travelled across the country listening to thousands of citizens concerns for the Earth in South Africa across 17 towns and went on to listen (over the past decade) to thousands more globally. Beuys told Sacks that it is important always to "make something" - make tangible that which is invisible. In this case, the receptive empathetic muscle we were trying to create in these social engagements needed a sculptural, and physical embodiment. Earth Forum, as a tactile object, came in the form of a large (1.5m diameter) circular oiled cloth - which was placed in a seated circle of diverse participants of each town. The forum took place in suitable strange venues, from train station platforms, traffic circles, dry riverbeds, and bank lobbies. This keeps participants awake, curious and imaginatively stimulated to listen attentively and develop the Response-ability to actively listen and empathize. The cloth would receive handfuls of earth from participants, during the forum, and the oil would hold the earth, staining the cloth as it aged through time, deepening its richness and symbolic quality. The oiled cloth itself became an actively empathetic participant in the forum, and in itself was a connective aesthetic instrument that, like the spectacles opened up a deeper engagement into attentive empathetic encounter. In an even greater way, it made tactile the inner sculpting of empathetic practice among participants (McGarry, 2014), as they commented on how significant it was to have left a mark in the cloth over time, that embodied their empathetic engagement with each other and the earth. Upon removing the spectacles, Sizo and I felt the warmth of the lenses and frames, and that had grown over the 30 min from our bodies, he reflected: “Even the spectacles can feel the warmth of this gaze”.

Response-ability - Active Listening: Developing a new social space in which different people, from different worldviews can come together and share their unique concerns can be very helpful. Begin with shaping the space with clear boundaries within yourself. Learn to actively listen, as opposed to passively receiving and responding. I am indebted to Shelly Sacks (2011c: 4) for this training on actively listening to each person's concern, without agreeing or disagreeing. When listening we sculpt thoughts and images in our minds. We literally create worlds within us in our listening, observing, empathising. However, oftentimes these images have more to do with our response to what we are hearing rather than actively listening to the content, feeling, and impulse from where it comes. We have the tendency go off into our world, preparing our reply. To fully receive matters of concern, it is important to remove the agreement and disagreement impulse from your listening. We rather stay with the person, with the pictures they are describing, we recreate their thoughts (to the best of our ability), to see what they see and feel. A good way to do this and focus more sharply on what someone is saying - to become a more active listener - is to consider what is being said in three ways. We can listen for the content of what is being said, we can listen to the feeling with which it is being said, and we can try and get a sense of the impulse or motivation in what is being said (Sacks, 2011: 4).

Tactile theory 3:

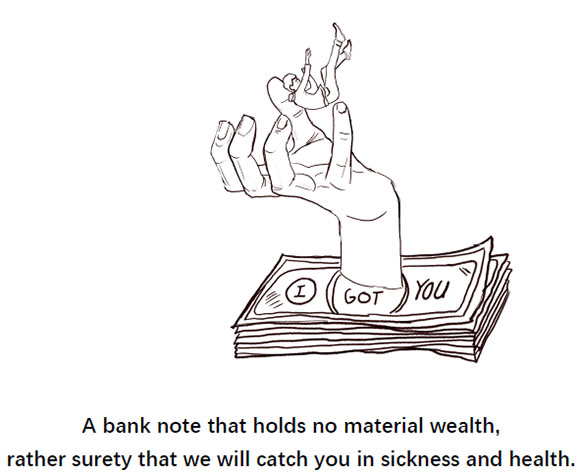

Warmth Work

This bank note physically embodies a tactile theory of trust and conviviality that suitably strange practice aims to create, and which is needed for the kind of social learning that expands towards collaborative and ontologically and epistemologically sensitive justice. The power of solidarity building in responding to critical and difficult processes can be felt in many movements. This is the antithesis of hyper-individualized perspective of the capitalistic west, that has eroded social traditions and processes that encourage and nourish solidarity. One of the remedies is conviviality and what Joseph Beuys (1977) referred to as "warmth work". It requires us to share the responsibility of the troubles we find ourselves in, with generosity and with active attention to friendship building. Our obsession with financial wealth has blinded us in a materialist tunnel-vision that forgets the profound wealth of the social, the wealth of friendship. If Barad (2007) is right, there are no things, just relationships.

Example - The Pluriversity for Stuck Humxns: Within the Transgressive Learning project (Lotz-Sisitka, 2016) we, a group of early career researchers, activists and others; came together in Columbia to share our questions, concerns, stories, practices, and methods to work out how we might 'unstuck' ourselves and others, in the sticky hot mess of the world as it is now. What emerged was the important gift that comes with solidarity building, and how this is often synonymous with friendship building. Indeed, Leah Temper reflected: "One indicator to know we are moving in the right direction is friendship". To ask ourselves "is friendship emerging?"

Solidarity asks us to stand together, to hold each other in many ways as friends, as colleagues and ecological citizens. We made time for each other, we created processes to tell and listen to each other's stories, we spent time around the fire, and we were more pro-active in making what seemed like mundane every-day tasks such as cooking, walking, talking, and speaking a little more interesting, by offering a suitably strange element to each of these day-to-day activities. For example, when speaking we encouraged each of us to use words from our home languages (between us we spoke 12 languages - Dinka, English, Spanish, Chichewa, Swahili, Hindi, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Afrikaans, Norwegian, German, Turkish, French). This opened up so many ways of sharing knowledge, and building trust between us, as we were making familiar concepts strange and then familiar again, by exploring them through interpretations. This loosened the hold of the concept as a static and locked-in phenomenon, and rather opened it up to something full of promise and transformation. Making convivial, friendly, lively, and warm environments when we gather is critically important. Noticing what spaces are we meeting in and how these are locked into particular social norms is critical. Ask yourself, is there natural light? can we see the sky? Is there access to outdoors? Are there opportunities to sit around a fire, to make warm drinks, to share food and recipes from our different cultures. If you have to meet in a windowless boardroom, how can you make it warmer, more humane? Can you meet in suitably strange ways to build a different kind of social currency? See our chapter "The Pluriversity for Stuck Humxns" (McGarry, et al., 2021), which explores this in more detail.

Response-ability - Warmth work: Social Sculpture founder Joseph Beuys between the 1960s and 1980s was surrounded by oppressive, incredibly painful, and grief laden post war German culture. It was in this cold, static and mournful space that Beuys developed his concept of 'warmth work' and aspect of social sculpture, which essentially refers to the process of lubricating and insulating normative social structures in creative empathetic ways (usually using a physical aesthetic sculptural process) to allow for the emergence of alternatives and shifts in paradigms and thinking. Susi Gablik (1992) speaks of connective aesthetics, in which aesthetics offers new approaches to relationality. In a related sense, Martin Shaw (2017) invokes James Joyce's concept of 'aesthetic arrest', where one is woken up to something familiar and moving. Shaw (2020) speaks of conjuring an aesthetic that doesn't require sophisticated intelligence, but rather takes you back to a time in your childhood where your attention was arrested by something beautiful and easy to love. As Beuys' saw it, warmth work was the potential of each human being to enliven and transform conditions in their lives. He (1977) also spoke of the "the warmth character of thought" which can be seen as the generous thought inspired by an aesthetic that can warm up a locked-in reality. Metaphorically like the warmth that softens fat or wax, and does not only refer to sentimental emotional warmth, but also to the ability to enliven, transform and warm up cold formative forces or -through wilful action - distil chaotic disordered forces. The warmth work concept was explored through specific embodied artworks developed throughout Beuys' life (See Kuoni, 1990). Beuys' theory of sculpture and his concept of 'warming up' solidified social forms, became a practice-based (and I would argue suitably strange) approach to finding ways of unlocking static and atrophied personal and societal (including structural) lock-ins. His sculptures and their use in social process became a way of embodying and sensing the conceptual theory (Sacks, 2012). From my experience, it would seem that this lends itself to how we approach learning in social settings, how we work with conventional normative unjust aspects of society/politics/economics and guide us towards the development of new pedagogy of empathy and solidarity through warmth practices. Shelly Sacks (2012) begins her teaching with her students in Social Sculpture by encouraging them to ask themselves: "What needs warming up?" (see McGarry (2013) for more on warmth work). Indeed, she asked me the same question.

Tactile theory 4:

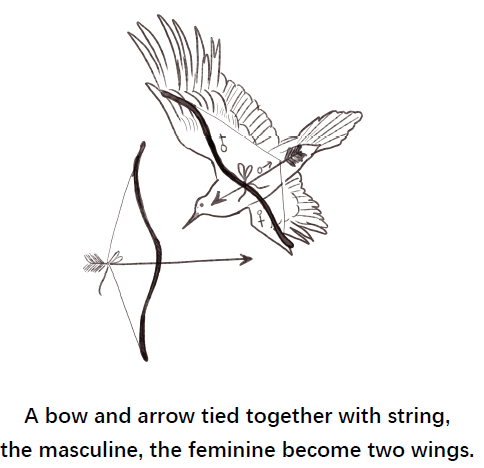

Navigating Power through participative parity

"Solidarity is not something activists do. It is a requirement of being a citizen of our times.... Solidarity is not an act of charity, rather it is a means of making us whole again.

Solidarity will ask of us what charity never can."

Alnoor Ladha (2020)

The bow and arrow bird brings us to a conversation around equality and shared responsibility (and reward) in our solidarity building. That we rely on each other to progress or become; as Dr. Martin Luther King put it: 'none of us are free until all of us are free' (King, 1992). Or as Lilla Watson, an Indigenous Australian expressed it: 'If you come only to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you come because your liberation is bound up in mine, then let us work together' (Habermann, 2014: 46 in Ziai, 2018). Essentially, we need to work deeper into solidarity, that which embodies, with greater intentionality, that which encourages and nourishes solidarity and friendship building. One aspect that has been vital for me is establishing participative parity (Fraser, 2003). It is difficult to create, but is aided profoundly through the use of suitably strange connective aesthetics and new forms of facilitation and social learning (McGarry, 2014, 2014, 2015). Participative parity, Fraser (2003) explained is the ability to create social arrangements that allow all members of society the ability to interact and communicate as peers, and on an equal footing. This suitably strange image also speaks to our obsession with moving forward at speed, and how often we leave others behind in our pictures of progress. Regardless of the urgency, we cannot risk this kind of neglect, parity is paramount. We forget the bow that helped the arrow fly in the first place, we forget the balance of feminine and masculine principles, and a queer awareness of everything that lies between these. Here we need to shift from an image of progress of launching the bow away from the world it came from, but rather tying these two together in an emergent, entangled and interconnected assemblage of making reality together, in the same way Akomolafe and Ladha (2017: 819) replace progress with emergence and call for a re-imagining of emergence as 'a radical indeterminacy that unsettles the grounds upon which the exclusionary discourses/practices of neoliberal expansionism as emergence are built'.

Example - Empatheatre: In our Empatheatre projects (www.empatheatre.com), like the Ulwembu example mentioned above, it was critical to create a suitably strange way of sharing such diverse stories we had heard across the social landscape of street level drug use. The stories were collaboratively analysed (by the team and through engagements with diverse publics) and a narrative script was developed. This was then performed to participants and partners in an immersive theatrical experience, to not only check the credibility of the play, but to expand dialogue and further democratise the research process, enforcing greater participative parity across race, class, and agency. Performances were then rolled out to strategic audiences. Audiences were carefully developed and were made up of people with different levels of agency, power, and privilege in relation to the matter of concern. Audience members were then invited to hold diverse, even conflicting, views on the central concern represented in the play they had just seen. These post-plays facilitated dialogues with the audience, did many generative things, but mostly it allowed people to build relationships, to understand and empathise with each other, and to build friendships built on understanding and making meaning together.

Response-ability - power analysis: Friends are able to speak to you truthfully. They often tell you things that no one else is brave enough to tell you. Solidarity and participative parity require the same level of bravery and honesty, particularly when it comes to navigating power. It is critical to understand the ways in which power manifests in the context and co-defined matter of concern you are working with. Who has power? How does this power materialize? Who has power over? Who has power with (i.e. where does solidarity lie)? Who gets to speak and who doesn't? When do you notice power shifts? How does race and economic class influence power? Developing a response-ability to analyse power, and to map it out in relation to your concern is vital in ensuring you are able to anticipate imbalances of power and develop suitably strange practices that can mitigate this, and enable parity. Vivienne Bozalek suggests how we can 'render each other capable' through being responsible (accountable) and response-able (responsive), and that this responsibility in research means '...an acknowledgement of non-innocence in our intra-actions with others. Non-innocence also requires an acknowledgement that both past and future are always already part of the thick now or present and consequently a necessity of taking responsibility for what we inherit from our entangled relationships' (2020: 146).

A useful resource for conducting power analysis is Jethro Pettit's (2013) "Power analysis: A practical guide" (also see Pettit, 2012). We must remember that all relationships, entanglements and assemblages are 'power-laden, preconstructed by history and weighted with social gravity' (Erickson, 2006: 237). There are therefore particular capacities we need to develop in order to understand and meaningfully respond to the relational and sometimes paradoxical dimensions of our research/collaboration with research partners. Particularly the ability to notice 'the ways relationships and the division of power and labour are negotiated and contested' (Gutiérrez, et al., 2016). As my friend Anna James has taught me, we as transgressive researchers need to ask questions like 'who does the research design and why? What are the unintended consequences of the partnership?; and who benefits?'(ibid). Gaztambide Fernandez (2012) describes relational solidarity as being framed by the questions:' 'how am I being made by others? What are the consequences of my being on others?'

Tactile Theory 5:

Intuition

The inner compass as dorsal fin speaks to intuition and the value of other ways of knowing, being, and doing. Here I learned the value of becoming apprentice to my own inner moral compass (see my work on the Empathetic Apprentice, McGarry (2014)) as a means to listen to my internal conversation (Archer, 2007), but also to be more attentive to other knowledge(s) (de Sousa Santos, 2015) and how I could chew and digest those stories in relation to my own experience (Shaw, 2020). It also provided new meanings, understandings, or entrances to empathy. I consider the internal conversation as a process towards agency development, particularly relational agency (McGarry, 2014), the agency to make relationships and build solidarity. This is as vital as our logical and rational thinking. It requires a constant reflexive rigor to steer us forward, like the dolphin's dorsal fin. The dorsal fin is what keeps the dolphin balanced, it allows her to pivot and roll with the shifting currents and to surf the turbulent sea. Intuition is a powerful response-ability we have to help us pivot and guide our response-abilities to worlds, cultures, ecosystems, societies that are in flux, it keeps us responsive to the present concerns. Intuition has been an important mentor and teacher for developing my 'response-abilities' , as it has helped me develop an approach to sustainable collaboration that keeps me grounded to the matters of concern that I am hearing and listening as I dig with our two-handled spade, listen with our three-eyed spectacles, and move with our entangled bow/arrow coupling. Dolphins, however, seldom swim alone, they swim together, relying on each other to find their way. So too, intuition used alone can lend itself to dangers such as developing unjust biases or mutating into speculative imagination. So, I have learned to carefully check my intuition with others swimming alongside me, as to ensure my intuition guides me to accountable and responsible actions and responses.

This intuitive organ of reflexivity is vital also to help you swim with others. Donna Haraway offers us something of how the inner work can support the relational. She suggests a 'diffractive practice' as an evolution of reflective practice, in which we decipher meaning and insights through one another, rather than against one another, all the while gifting our communal attention to the specificities of the 'matterings' enacted through the diffraction (I borrow this insight from Juelskjær, et al. (2020: 11). In other words, our inner work helps us in conceptualizing difference and for studying different configurations of difference (Haraway, 1988, 1992, 1997; Barad, 2014). I would argue that this requires a sophisticated social learning organ, something like echolocation in dolphins - we need to develop a pedagogy of echolocation. Where we are able to listen into the depths and across the textures of each other's worlds, and respond meaningfully to what echoes back, as to locate where we are in relation to each other.

Example & Response-ability - Journaling as diffractive and iterative practice: Here I combine the example and the response-ability together, in the form of journaling. It can be very useful to develop a journaling practice. To have a book or a place where you work and write in everyday, that holds all aspects of your life. To not be too precious about this book. It should hold your notes from meetings, your dreams you had the night before, your shopping lists, inspiring quotes, and ideas, etc. You are a single humxn being and doing many things, and so a single book should act as both your reflexive mirror as well as your diffracting prism. My Godmother taught me to keep a ruler sized margin on the right edge of each page. She said Franciscan monks did this to leave room for the spirit to enter the pages. I leave this margin blank throughout the week, at the end end of the week, I read over and look at my notes, and reflect and write down any themes, images, commonalities, or dissonances emerging in my internal conversation. This becomes a practical approach for inner diffractive meaning making, across thoughts, concepts, themes, stories, matterings, and experiences. The journal, I have learned therefore acts as my compass, it can help pick up subconscious information, as well as deepen and refine your capacity to listen to more internal and quiet knowing's emergent in my life. I recommend Laura Ellingsons (2017) work on Embodied Qualitative research to assist in further development of this organ.

Tactile theory 6:

What I dissect, dissects me - what I observe, observes me

The double-sided axe is inspired by Ben Okri (1991) and by my mentor Prof. Heila Lotz-Sisika who reminded me that while we analyze and dissect the world, we must not be blind to the ways that we are being dissected and analyzed by the world. The double-sided axe reminds us of the power and importance of humility and grace in this work. Suitably strange work is also sensitive, surgical and slow work. We are engaging with, sometimes intervening in complex social structures, that are entangled in ways we can never fully understand. Therefore, we approach suitably strange work with care and caution. We go beyond the ethical demands of do-no-harm, and we practice ongoing ethical reflexivity - we stay in conversation with those we work with, we notice how we are changing in these conversations. We constantly ask for consent in all that we do, and through call and response, though a pedagogy of echolocation, we find our way towards ethically sound and socially robust suitably strange practice. Finding the 'suitable' aspect of the 'strange' requires this double-sided axe.

Question: In this final suitably strange artifact I share neither an example or a response-ability, but rather a single question for you to reflect on: "How am I being changed by that which I observe and engage with, and how might I observe and engage with greater care and kindness, in an ongoing and reflexive/diffractive way?"

Suitably Strange in the service of cognitive justice

These familiar artefacts have been made strange to disrupt and open up ways of exploring what aspects of transgressive learning have for me, been vital in my work towards sustainable development learning, activism, and justice, as well as my practice in decolonizing the academy, through alternative methodologies and theory making. The uncanny artefacts hold concepts, but also hold something tactile, many of them you can actually touch and feel and engage with your body, unlike a body of text. Surfacing here for the first time is the concept of 'justness' as a proactive alternative to justice, to make clear and alive in the present, the "just-so" of things (McGarry & Vermeylen, 2018). I have found suitably strange practice a useful instrument in researching transformation; engaging with sustainable development; facilitating social learning and; expanding our understanding of justice to 'justness' in times of ecological crisis.

Lotz-Sisitka, et al. (2015: 78), sounded the foghorn for rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. They argue that at the core of transforming and decolonising higher education is the need for a 'form of disruptive competence' one in which "broader forms of knowledge co-production, decolonial practice, and disruptive competence and agency in and through curriculum, provides opportunities for a radical, itinerant curriculum process that can allow an understanding of 'how reality can explode in and change the real.' This disruptive competence, I have learned, requires adopting something of these six tactile theories, that being co-defining concerns, actively listening, apply convivial warmth, witnessing, and navigating power, diffractively intuitive and are politically rigorous.

Perfecting the art of the suitably strange is essentially perfecting the art of creating space for invisible or unrecognized 'response-abilities' to enter into the realm of learning as activism.

Suitably strange speaks to the practical need to make strange the familiar and normative paradigms that are holding us back from real and meaningful transformation and change, particularly within higher education. I have dwelled and ruminated on the role of suitably strange creative practice as a vital approach to developing response-abilities for transforming and re-imagining learning, activism and justice in the era of ecological apartheid and have drawn mainly from my PhD (McGarry, 2014) and Post-doctoral journal with Empatheatre, which articulates a decade long journey of developing creative pedagogical practices for transformative, transgressive learning in the context of environmental justice related struggles. I believe that within the public pedagogy and decolonial/regenerative academic arenas a suitably strange approach can contribute to expanding and opening up imaginations, empathy, intuition, participative parity, reflexivity, and diffraction in social learning and in democratizing plural knowledge sharing. I leave you with these uncanny artefacts, and the tactile theories they embody as a means to avoid assuming the world and all the mysteries contained in it are predictable and normal. I do this to ensure we do not forget how remarkably unusual, peculiar, and strange it is to be part of this entangled mystery - and now more than ever, we need to develop pedagogies for the suitably strange.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful for the incredible support and guidance I received from Dr. Saskia Vermeylen in developing this paper, and in giving me the courage to make this work manifest. I am also indebted to Prof Heila Lotz-Sisitka who encouraged me to make the tiny book that lead to this paper, and has always nurtured me in following my suitably strange intuition. I am indebted to Kira Erwin, Injairu Kulundu, Sizo Mahlangu, Taryn Pereira, Neil Coppen, Mpume Mthombeni, Danel Janse van Rensburg, Anna James, Jessica Cockburn, Shelly Sacks, Viv Bozalek, Aaniyah Omardien, Leah Temper, Lena Weber, David Kronlid and Stefan Bengtsson in their assistance in helping me develop the language and feeling for this paper. I am also grateful to my grandmother Natalie (Uzthulele), and My godmother Reza in developing the transparent being required to find this tactile theory in my practice. Finally thank you Cleo, for supporting me in making work that is love made visible.

Author Biography

Dr. Dylan McGarry (pronouns Dyl, They, Them) is an educational sociologist and artist from Durban, South Africa. Dyl is a Senior researcher at the Environmental Learning Research Centre (ELRC) at the University currently known as Rhodes. As well as the South African Director of the Global One Ocean Hub research network. Dyl is the co-founder of Empatheatre, and a passionate artist and storyteller. Dyl explores practice-based research into connective aesthetics, transgressive social learning, decolonial practice, queer-eco pedagogy, immersive empathy, and socio-ecological entanglements in South Africa. Their artwork and social praxis (which is closely related to their research) is particularly focused on empathy, and they primarily work with imagination, listening and intuition as actual sculptural materials in social settings to offer new ways to encourage personal, relational, and collective agency.

References

Abram, D. 1996. Thie Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than- Human World. New York: Vintage. [ Links ]

Abramović, M., Biesenbach, K. & Stokic, J. 2010. Marina Abramović: The artist is present. The Museum of Modern Art.

Akomolafe, B. & Ladha, A. 2017. Perverse particles, entangled monsters and psychedelic pilgrimages: Emergence as an ontoepistemology of not-knowing. Ephemera, 17(4): 819-839. [ Links ]

Archer, M. 2007. Making Our Way Through the World: Human Reflexivity and Social Mobility. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Barad, K. & Gandorfer, D. 2021. Political Desirings: Yearnings for Mattering (,) Differently. Theory & Event, 24(1): 14-66. [ Links ]

Beuys, J. 1974. Joseph Beuys in conversation with Shelley Sacks. In Harlan, V. (ed.) 2004. Joseph Beuys, What is Art? East Sussex: Clairview Books. [ Links ]

Beuys, J. 1977. Eintritt in ein Lebewesen: lecture given during Documenta 6 in Kassel, Germany. Audio cassette. Wangen: FIU. In Sacks, S. 2011. Social Sculpture and New Organs of Perception: New practices and new pedagogy for a humane and ecologically visible future. In Lern Hayes, C.M. & Walters, V. (eds.) Beuysian Legacies in Ireland and Beyond: Art Culture and Politics. Berlin: Lit Verlag.

Beuys, J. 1965. "Spade with Two Handles." Energy Plan for the Western Man: Joseph Beuys in America, 127-29.

Biko, S. 1978 (2004). I Write What I Like, Steve Biko: A Selection of His Writings. Johannesburg: Picador Africa. [ Links ]

Bozalek, V. 2020. Rendering each other capable: Doing response-able research responsibly. In Murris, K. (ed.) Navigating the Postqualitative, New Materialist and Critical Posthumanist Terrain Across Disciplines. London: Routledge, 135-149. [ Links ]

Coppen, N., Mthombeni, M., & McGarry, D. 2018. Ulwembu: A Play. Wits University Press.

de Sousa Santos, B. 2015. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

de Wet, F. 1978. The predicament of contemporary man as exemplified in six modern dramas. Unpublished master's thesis, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Ellingson, L.L. 2017. Embodiment in Qualitative Research. London: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Erickson, F. 2012. Studying side by side: Collaborative action ethnography in educational research. In Spindler, G. & Hammond, L. (eds.) Innovations in Educational Ethnography: Theories, Methods, and Results. Hove: Psychology Press, 248-270. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. 2003. Social justice in the age of identity politics: redistribution, recognition and participation. In Fraser, N. & Honneth, A. (eds.) Redistribution or Recognition? A Political Philosophical Exchange. London: Verso, 4-31. [ Links ]

Gell, A. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Gough, N. 2009. Becoming transnational: Rhizosemiosis, complicated conversation and curriculum inquiry. In McKenzie, M., Hart, P., Bai, H. & Jickling B. (eds.) Fields of Green: Restorying Culture, Environment and Education. USA: Hampton Press, 67-83. [ Links ]

Habermann, 2014. Geschichte wird gemacht! Etappen des globalen Widerstands. Hamburg: Lailea Verlag. [ Links ]

Haraway, D.J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Holifield, R. 2001. Defining environmental justice and environmental racism. Urban Geography, 22(1): 78-90. [ Links ]

Husserl, E. 1929. Cartesian Meditations: An introduction to Phenomenology, trans. D. Cairns. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. [ Links ]

Juelskjær, M., Plauborg, H. & Adrian, S.W. 2020. Dialogues on Agential Realism: Engaging in Worldings Through Research Practice. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

King, M.L., Carson, C., Holloran, P., Luker, R.E. & Russell, P.A. 1992. The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume V: Threshold of a New Decade, January 1959 December 1960 (Vol. 5). Univ of California Press.

Kulundu-Bolus, I. 2020. Not Yet Uhuru! Attuning to, re-imagining and regenerating transgressive decolonial pedagogical praxis across times: Khapa (ring) the rising cultures of change drivers in contemporary South Africa. Unpublished PhD diss., Rhodes University, South Africa. [ Links ]

Kuoni, C. (ed.) 1990. Joseph Beuys in America: Energy plan for the Western Man: Writings by and Interviews with the Artist. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows [ Links ]

Latour, B. 2004. Why has critique run out of steam? From matters of fact to matters of concern. Critical inquiry, 30(2): 225-248. [ Links ]

Lotz-Sisitka, H., Wals, A.E.J., Kronlid, D. & McGarry, D. 2015. Transformative, transgressive social learning: rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 16:73-80. [ Links ]

Lotz-Sisitka, H.B., Belay, M., Mphepo, G., Chaves, M., Macintyre, T., Pesanayi, T., Wals, A., Mukute, M., Kronlid, D., Tran, D., Joon, D. & McGarry. D. 2016. Co-designing research on transgressive learning in times of climate change. Current Opinion on Environmental Sustainability. 20: 50-55. [ Links ]

Lotz-Sisitka, H. 2017. Decolonisation as future frame for environmental and sustainability education: embracing the commons with absence and emergence. In Corcoran, P.B., Weakland, J.P. & Wals, A.E.J. (eds.) Envisioning Futures for Environmental and Sustainability Education. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers, 45-62. [ Links ]

Lotz-Sisitka, H. & McGarry, D. 2018. Transgress to Learn, learn to transgress: a source book for stuck humans in times of climate change. Unpublished Manuscript.

Lysgaard, J.A., Bengtsson, S. & Laugesen, M.H.L. 2019. Introduction: Living in Dark Times. In Lysgaard, J.A., Bengtsson, S. & Laugesen, M.H.L. (eds.) Dark Pedagogy: Education, Horror and the Anthropocene. London: Palgrave Pivot, Cham. [ Links ]

Okri, B. 1991. The Famished Road. London: Jonothan Cape Publishers. [ Links ]

MacDorman, K.F. & Ishiguro, H. 2006. androids. Interaction Studies, 7(3): 297-337. [ Links ]

Manning, E. 2016. The Minor Gesture. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Mathur, M.B. & Reichling, D.B. 2016. Navigating a social world with robot partners: a quantitative cartography of the Uncanny Valley (PDF). Cognition, 146: 22-32. [ Links ]

Macintyre, T. & Chaves, M. 2017. Balancing the warrior and the empathic activist: The role of the transgressive researcher in environmental education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 22: 80-96. [ Links ]

McGarry, D. K. 2014. Empathy in the time of ecological apartheid: a social sculpture practice-led inquiry into developing pedagogies for ecological citizenship. Unpublished PhD thesis, Rhodes University, South Africa. [ Links ]

McGarry, D. 2015. The listening train: A collaborative, connective aesthetics approach to transgressive social learning. Southern African Journal of Environmental Education, 31, 8-21. [ Links ]

McGarry, D., Weber, L., James, A., Kulundu-Bolus, I., Pereira, T., Ajit, S., Temper, L., Macyntire, T.K., Villarreal, T., Moser, S.C., Shelton, R., Villegas, M.C.C., Kuany, K.K., Cockburn, J., Metelerkamp, L., Bajpai, S., Bengtsson, S., Vermeylen, SI., Lotz-Sisitka, Hl, Turhan E. & Khutsoane, T. 2021. The pluriversity for stuck humxns: A queer ecopedagogy & decolonial school. In Russell, J. (ed.) Queer Ecopedagogies Explorations in Nature, Sexuality, and Education. London: Springer, Cham, 183-218. [ Links ]

McGarry, D & Vermeylen, S. 2018. Uncanny Justness: objects, metaphors and stories that re-imagine learning, activism and justice through suitably strange creative practice. A Manifesto for the Institute of Uncanny Justness. Available at: www.uncannyjustness.orghttp://www.uncannyjustness.org/uploads/1/2/3/0/12303478/uncanny _justness_papersv_dylan_edit_for_website.pdf (Accessed 12 January 2021).

Merleau-Ponty, M. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible, trans. A. Lingis. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [ Links ]

Morton, T. 2007. Ecology without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Morton, T. 2014. Realist Magic: Objects, Ontology, causality. London: Open Humanities Press. [ Links ]

Pettit, J. 2013. Power Analysis: A Practical Guide. Sida. Available at. https://publikationer.sida.se/contentassets/55174801cd1e4b66804430219bab88b3/power-analysis-a-practical-guide_3704.pdf (Accessed 12 January 2021).

Pettit, J. 2012. Empowerment and participation: Bridging the gap between understanding and practice. Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/egms/docs/2012/JethroPettit.pdf (Accessed 12 January 2021).

Posner, P.L. 2009. The pracademic: An agenda for re-engaging practitioners and academics. Public Budgeting & Finance, 29(1): 12-26. [ Links ]

Pulido, L. 2008. FAQs: Frequently (Un) Asked Questions about Being a Scholar Activist. In Hale, C.R. (ed.) Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship. California: University of California Press, 341-366. [ Links ]

Quaye, S.J., Shaw, M.D. & Hill, D.C. 2017. Blending scholar and activist identities: Establishing the need for scholar activism. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 10(4): 381. [ Links ]

Reiter, B. 2018. Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge. London: Duke University Press [ Links ]

Sacks, S. 1998. Warmth Work: Towards an Expanded Conception of Art, unpublished. paper presented to "The World Beyond 2000" at UNESCO Summit on Culture and Development, Stockholm.

Sacks, S. 2007. Instruments of consciousness. University of the Trees. Available at: http://www.universityofthetrees.org/about/instruments-of-consciousness.html (Accessed 25 October 2012).

Sacks, S. 2011a. Social Sculpture and New Organs of Perception: New practices and new pedagogy for a humane and ecologically visible future. In Lern Hayes, C.M. & Walters, V. (eds.) Beuysian Legacies in Ireland and Beyond: Art Culture and Politics. Berlin: Lit Verlag. [ Links ]

Sacks, S. 2011b. Giving and ecological citizenship: the inner movement toward appropriate form. English text unpublished, published in German in June 2011, commissioned by GLS for the 50th anniversary interdisciplinary publication on Giving.

Sacks, S. 2011c. Draft Handbook for Exchange Values Responsible Participant. Unpublished.

Sacks, S. 2012. Social Sculpture Lecture Series from the first semester Social Sculpture MA course. September-November 2012. Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Scharmer, O. 2007. Addressing the blind spot of our time: An executive summary of the new book by Otto Scharmer Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges. Available at https://solonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Exec_Summary_Sept19-Theory-U-leading-from-the-emerging-future-copy.pdf (Accessed 4 September 2012)

Scharmer, C.O. 2009. Theory U: Learning from the Future as it Emerges. Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [ Links ]

Scholz, N. 1986. Joseph Beuys-7000 Oaks in Kassel. Anthos, 3, 32. [ Links ]

Shaw, M, 2017. Martin Shaw on imagination: "I would describe it as 'ripe for invasion'". Rob Hopkins Podcast. Available at: https://www.robhopkins.net/2017/05/04/martin-shaw-on-imagination-i-would-describe-it-as-ripe-for-invasion/ (Accessed 27 January 2021).

Shaw, M. 2020. Courting the Wild Twin. Interview with Emergence Magazine. Available at: ihttps://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/courting-the-wild-twin-martinshaw/d1368790239?i=1000479730015 (Accessed 17 January 2021).

Steiner, R. 1894. The Philosophy of Freedom: Spiritual Activity, trans. R.F.A. Hoernlé and Hoernlé.

Tisdall, C. 2008. Joseph Beuys, Coyote. London: Thames & Hudson. [ Links ]

Wals, A.E., Van der Hoeven, N. & Blanken, H. 2009. The Acoustics of Social Learning. Designing Learning Processes that Contribute to a More Sustainable World. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Ziai, A. 2018. Internationalism and speaking to others: What struggling against neoliberal globalisation taught me about epistomology. In Reiter, B. (ed.) Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge. London: Duke University Press, 117. [ Links ]

Submitted: 13 December 2021

Accepted: 24 March 2022

Corresponding author: d.mcgarry@ru.ac.za

1 I was originally inspired by Noel Gough (2009: 74) who described 'defamiliarisation' as 'making the familiar strange, and the strange familiar' in his rhizomatic curriculum inquiry. Gough (2009: 75) described the tactic of surprise as useful in diminishing distortions and helping us recognise our own preconceptions, a 'learning-as-forgetting' that enables the potential for new intellectual breakthrough. According to Gough (2009:81) 'Defamiliarization' has been attributed to the German poet Novalis (1772-1801, aka Friedrich von Hardenberg). Gough (2009) also cited Russian formalist Victor Shklovsky (1917-1965) who introduced the concept of ostraneniye (literally "making strange") to literary theory.

2 I take inspiration from Laura Pulido's (2008) frequently (un)asked questions for Scholar Activists, to help define or give shape to my approach to scholar activism.

3 I use the term anthropocentric, with the clear understanding that I cannot lump all humans (or should I say humxns) under the same umbrella, but rather make known the conventions I speak of are those that have emerged in the western industrial capitalist project, and I do not include the remaining cohort of humxnity, who were not responsible for establishing these.

4 Illustrations by McGarry

5 These uncanny artefacts emerge within my context, with no particular relation to Dadaist and Surrealist 'making strange' collages and techniques, but rather emerge from Joseph Beuys' concepts of making strange through warmth work and social sculpture, see capacity warmth work below. Furthermore, I attempt to insert them into the field of transgressive social learning theory (Lotz-Sisitka, et al., 2015), as an effort to optimally disrupt and generatively open new thinking, feeling and being to support new re-imaginings of learning, scholar-activism, and justice.

6 I identify as gender nonconforming, which simply means that I do not accept society's traditional gender norms. Therefore, I do not conform to the gender expression, presentation, behaviours, roles, or expectations that society sees as the norm for their gender.

7 I refer to myself as a social sculptor in relation to Joseph Beuys' theory of social sculpture which essentially states that everything is art, that every aspect of life could be approached creatively and, as a result, everyone has the potential to be an artist, more so that we are able to sculpt the conditions that shape our lives, see my earlier work (McGarry, 2014).

8 Bergman, who was strongly influenced by influence of Surrealism, Dadaist 'anti-symbolism' and the Freudian uncanny, has been an important influence on my approach to storytelling from a young age.

9 Dark pedagogy is a collaborative and generative effort to understand and rethink current pedagogical and educational perspectives (Lysgaard, et al., 2019). Particularly on how we handle issues such as the imminent climate crisis, environmental issues on a global level and ways to include the more than human into our theories and practices (Lysgaard, et al., 2019).

10 Mannig's (2016) research-creation, an evolution of arts-based research, encompasses transversal engagement with different disciplines, which in turn inspires the rethinking of how artistic practice wakes up new question of what these disciplines can do, and how research-creation can nourish the understanding of the research question at hand. Manning sees research-creation as process- rather than outcomes-driven, and the focal area is living process, which allows the research to work begins outside (or in the liminal margins of) disciplinary and institutional constrictions

11 While I call these artefacts of agency also 'tactile theories', I refer mainly to the idea that these capacities can also be embodied in a sculptural and physical form, that holds meaning and significance, and can be something you can touch and feel in the very corporeal and physical, if not phenomenological sense as well. I do not however, make assumptions or presumptions of theoretical principles pertaining to tactility, but rather the practice making visible (and tactile) the sometimes-invisible qualities of meanings, concepts, and related capacities.

12 The goal of environmental justice is essentially to ensure that all people, regardless of race, national origin or income, are protected from disproportionate impacts of environmental hazards (Holifield, 2001), yet the Holifield states that the absence of limits on the kinds of issues that the term environmental justice can address gives the term much of its rhetorical power, and the quest for a universal standard of what is termed 'environmental justice' is an ongoing debate. In the context of my work in South Africa, and the global South, Environmental Justice is mainly tied up with inequalities in access to clean air, water, and natural resources - as well as the long legacy of apartheid, which has excluded people from accessing their homelands, their indigenous ways of life and their customary practices of sustainably using and managing resources.

13 See Abramović, M., Biesenbach, K., & Stokic, J. (2010)

14 Ecological Apartheid, which I define as a growing separation of relationships that include the human being's relationship with the natural world, as well as disconnections experienced within one's own inner and outer capacities (McGarry, 2014).