Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning

versão On-line ISSN 2310-7103

CRISTAL vol.10 no.1 Cape Town 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v10i1.572

SPECIAL ISSUE

Beyond heteronormativity towards social justice: Disrupting gender operationalisation in teaching and learning trends in higher education

Zahraa McDonald#; Shireen Motala

University of Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

Quantitative approaches, based on numerical analyses of operationalised variables, used to present teaching and learning trends in higher education, are pervasive. However, teaching and learning trends disaggregated by gender are generally collected and/or reported according to a binary operationalisation. The gender binary is associated with heteronormative dispositions. This paper examines the extent to which gender operationalisation, as it relates specifically to teaching and learning trends in South Africa, promotes heteronormative dispositions and the consequent implications for social justice. Framed within Nancy Fraser's approach to social justice, heteronormative dispositions constitute misrecognition and hence injustice. Based on a review of data gathering and reporting on teaching and learning trends by the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET), it is clear that, at present, non-binary expressions or analyses of gender are misrecognised. The paper argues that gender operationalisation associated with trends in teaching and learning contributes to heteronormative dispositions that are not commensurate with social justice. It calls for the disruption of binary gender operationalisation linked to teaching and learning trends as a mechanism for full recognition and socially just knowledge production. This paper does not focus on research in a moment of social disruption but rather seeks to disrupt research processes which could be exclusionary and promote injustice, and thus interrupt socially-unjust representations, specifically as it relates to gender.

Keywords: gender operationalisation, heteronormative, social justice, teaching and learning

Introduction

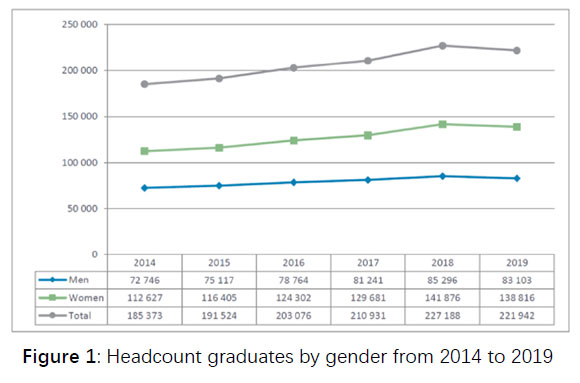

Quantitative approaches, based on numerical analyses of operationalised variables, used to present teaching and learning trends in higher education, are pervasive. However, teaching and learning trends disaggregated by gender are generally collected and/or reported according to a binary operationalisation (see for examples CHE, 2020, 2021). Figure 1 captured below from the Council on Higher Education's (CHE, 2021: 4) annual Vital Stats publication is one example of how teaching and learning trends are commonly reported on South Africa.

Yet, the gender binary is associated with heteronormative dispositions. Heteronormativity assumes two sexes, male and female, with sexual relations between the two as the only normal and natural social interactions (Smuts, et al., 2015: 66). Heteronormativity constrains the varying and complex ways in which individuals identify with gender in society.

Maintaining heteronormative dispositions has far-reaching consequences in the South African context and internationally. Hate crimes against individuals who do not conform to gender binaries are prevalent in South Africa (Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2021). Beyond South African borders, also, non-conforming or non-binary statuses are associated with increased violence, abuse and exclusion (Lennon & Alsop, 2020: 6). The United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) recognises that 'Violence is often directed at those whose gender expression does not fit binary gender norms' (UNESCO, 2020: 32). 'In the United Kingdom, 45% of lesbian, gay and bisexual students and 64% of transgender students were bullied in schools' (UNESCO, 2020: 4). The grip of the binary man/woman modality of gender identification 'is the source of violence and dislocation suffered by many groups, including those for whom neither side of the binary currently offers a comfortable resting place' (Lennon & Alsop, 2020: 6).

Although the South African Constitution makes provision for equal rights and freedom for all irrespective of gender identification, 'patriarchy and homophobia still subsist within the larger South African context' (Smuts, et al., 2015: 1). This raises questions about the ways in which public opinions about gender identification and heteronormative views are constructed (Smuts, et al., 2015: 1). Smuts, et al. (2015: 1) argue that heteronormative ideals are communicated in various ways, including through family and religion.

Heteronormative dispositions can, it is contended here, be cemented by how data on gender are gathered and disseminated in education reports. In the UNESCO report that shows violence is meted out against those who do not fit binary gender norms (UNESCO, 2020), the overwhelming majority of findings regarding education outcomes disaggregate gender in binary categories only. Research into non-binary categories such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex in the report relates to school violence only (UNESCO, 2020: 55).

Gender binaries can be affirmed, naturalised, and reinforced in quantitative reporting about trends in teaching and learning. Such data collection and analyses could act as a pedagogic device of the gender binary in society particularly in relation to education where young people in institutions of learning at primary, secondary and tertiary levels are - in many cases without their consent - boxed into gender binaries. It is thus not surprising that Garvey, et al. (2019: 3) note that interrogating gender in quantitative research in the field of higher education requires attention.

Feminist and queer theories suggest that higher education scholars should rethink the usage of binary variables for collecting demographic data, which may have far-reaching effects (Garvey, et al., 2019: 2).

The paper interrogates the extent to which gender operationalisation, specifically as it relates to teaching and learning trends in South Africa, promotes heteronormative dispositions and considers the consequent implications for social justice. Framed within Nancy Fraser's approach to social justice, heteronormativity constitutes misrecognition and hence injustice. A review of the DHET's data gathering and reporting on teaching and learning trends shows that, at present, non-binary expressions and analyses of gender are misrecognised. The contention therefore is that gender operationalisation associated with trends in teaching and learning contributes to heteronormative dispositions inconsistent with social justice. To address this, the paper calls for disrupting binary gender operationalisation linked to teaching and learning reporting trends as a mechanism of achieving full recognition and socially just knowledge production.

The first section of the paper unpacks operationalisation as a component of quantitative research designs that enable statistical calculation of variables. The second section discusses Nancy Fraser's conception of social justice within the context of recognition and misrecognition as well as how it might relate to heteronormative gender operationalisation. The third section gives an analysis of how gender is operationalised when data aimed at teaching and learning trends are collected by the DHET. The conclusion summarises the discussion and offers some thoughts towards an alternative, non-binary and socially just operationalisation of gender for trends in teaching and learning.

Operationalisation of variables in quantitative research designs and statistical analyses

This section of the paper explains variable operationalisation as a component of quantitative research designs that enable statistical analyses. Variable operationalisation is underpinned by the nature and scope of quantitative approaches to doing research. Quantitative approaches to research or quantitative methodologies aim to examine phenomena numerically (Walter and Andersen, 2013). In the process of doing so, quantitative research designs are guided by certain conditions for the numerical and statistical analysis and explanation of social phenomena. An example of a condition is that all variables, including gender, require operationalisation in order to make quantifying them possible.

In quantitative approaches, data from responses to survey or questionnaire instruments are described in relation to variables or items. Variables are operationalised in survey instruments for respondents to select the option that best applies to them. For example, if 645 individuals respond to a survey and one of the variables had three options, the 645 responses would be divided amongst those three options (even if one or more option had '0' responses). For each of the three options, the data could then be represented numerically. Variable operationalisation and collection have lasting consequences for analyses of the data gathered (Garvey, et al., 2019: 14). Consequently, '[q]antitative methodologies facilitate standardization and render information specific to local social relations both mobile and combinable' (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 11). Via quantification and standardisation, statistical analyses become possible.

Statistical analysis, which forms the bedrock of quantitative approaches, holds power in the arena of knowledge production. 'Foucault and others have argued that statistics represented a central technology through which social relations were rendered "governable"' (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 12).

Population statistics in particular are an evidentiary base that reflects and constructs particular visions considered important in and to the modern state. They map the very contours of the social world itself. They shape and thus create the accepted reality of things most of us think they merely describe (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 7).

Quantitative approaches have been critiqued for claiming objectivity and truth. 'The positivist paradigm is associated with quantitative research methodologies' (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 42), and has similarly been critiqued for false claims of objectivity and truth seeking. These critiques relate to the rigidity of variable operationalisation. Qualitative researchers critique this philosophical position for missing complexity in social relations and downplaying particular places, or localities (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 11). One way in which complexity can be missed, or indeed misrecognised, is the extent to which a variable is operationalised in a manner that does not include options applicable to every respondent. In this way, a survey instrument precludes particular ways of being in the world, and therefore of coming to know it. Walter and Anderson state that

rather than representing neutral numerics, quantitative data play a powerful role in constituting reality through their underpinning methodologies by virtue of the social, cultural, and racial terrain in which they are conceived, collected, analysed, and interpreted. (2013: 9)

In the case of gender or gender identities, the absence of non-binary options would regulate the responses of individuals who do not conform to binaries. The complexity of gender has been problematised extensively (see for example Butler, 1990). Gender is conceptualised in contrast to sex, with sex being the biological distinction between male and female while gender is socially constructed and thus variable across time and space (Lennon & Alsop, 2020). As the biological female and male divisions are challenged, both sex and gender are viewed in current debates as variable categories (Lennon & Alsop, 2020). Gender is conceptualised as a positioning related to binary categories male and female (Lennon & Alsop, 2020). Non-binary gender categories refer to positioning oneself in relation to neither male or female, be it biologically or socially (Lennon & Alsop, 2020). From this perspective, the stance is adopted that gender is a contested construct that refers to social positioning related to the binary categories of female and male, be it to conform or not conform to them.

Claims of objectivity as a methodological principle mean that subjectivity and social positioning are not often characteristics of quantitative research strategies (Walter & Andersen, 2013). When such data are gathered for social policy purposes and embedded in government reporting, social positioning is mostly not disclosed. Walter and Andersen see social position as a verb rather than a noun: something that continuously shapes how researchers 'do, live and embody research practice' (2013: 47).

Feminists, in particular, have critiqued assumed objectivity and rationality of dominant ways of knowing, arguing that how gender shapes knowledge production has been ignored (Walter & Andersen, 2013). Walter and Andersen (2013) contend that all epistemology is culturally and socially positioned. Said differently, 'dominant methodologies emerge from the dominant cultural framework of the society of their investigators and users' (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 15). An alternative approach to positivist paradigms has emerged: quantitative criticalists who, according to Garvey, et al. (2019), opt for relative objectivity and advocate for social justice. Garvey, et al. (2019) also claim that how gender is operationalised in quantitative approaches is consistent with the aims of quantitative criticalists.

There are two important moments at which operationalisation might influence public opinion about heteronormative dispositions. In the first instance, it could be instructive for the respondent; the options available in a survey can lead a respondent to think that these are the only options available. Education institutions are important mechanisms for inserting ideas and debates into the public sphere and, in so doing, generating public opinion (McDonald, 2013). When gender is operationalised as a binary in a survey instrument and the instrument is administered, the individuals responding to it who make up the general public can internalise the options as normal and common place. The ideas and debates established in the public sphere by education institutions, or government department, in this case via the research they do, including the manner in which they collect data, can in turn be regarded as public pedagogy to the extent that individuals could be instructed by and consequently learn from such data collection. This learning might not be intentional or part of the formal curriculum; it might, however, be no less effective.

Secondly, the operationalisation limits the analysis and hence the manner in which findings are disseminated. Garvey, et al. state that 'the restrictions placed on gender and sex variables during survey design and data collection foreclose later opportunities for scholars to have more expansive and inclusive uses in quantitative analyses' (2019: 4). At a basic epistemic level, if an option is not contained in the operationalisation of a variable it cannot contribute to knowledge about that variable, or the concept and phenomenon the variable is associated with. The survey findings would therefore further normalise the binary gender categories which can become rooted in public policy (Garvey, et al., 2019: 3). Numerical representation of variables informs statistical analyses of them.

To the extent that statistics are used to monitor progress, it can become the backbone of how social policy is implemented (Walter & Andersen, 2013). Statistics also influence what we say about ourselves (Walter & Andersen, 2013). Walter and Andersen claim that 'quantitative "proof" is fundamental to advancing a convincing case for much needed social and political change' (2013: 134). The cultural weight and power of statistical techniques and numerical summaries they generate speak a "truth" about communities on which they shine their statistical light. But the way that they shine that light pushes out other ways of conceiving about and acting upon those communities (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 9).

Statistical results are important for policy decision making in South Africa. The country's current National Development Plan (NDP) states that 'Policy changes should be approached cautiously based on experience and evidence so that the country does not lose sight of its long-term objectives' (NPC, 2012: 59). In addition, the Strategic Plan of the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET, 2020a) states that improving evidence-based decision making will improve efficiency, leading to the optimal use of post-school education and training resources. Evidence is drawn from statistical analyses of variables operationalised in particular ways. As long as the traditional gender binary is maintained in evidence gathered for policy intervention, those who do not conform to the binary will be excluded from public discourse.

The social, cultural, and economic phenomena that are chosen for inclusion, and also those which are excluded, provide a reflection of the nation-state's changing social, cultural, and economic priorities and norms (Walter & Andersen, 2013).

Social (in)justice and heteronormative gender operationalisation

This paper interrogates the extent to which gender operationalisation, specifically as it relates to teaching and learning trends in South African higher education, promotes heteronormative dispositions and consequent implications for social justice. This section proceeds to develop a relationship between heteronormative dispositions and Nancy Fraser's concept misrecognition. When one is misrecognised, one is 'denied the status of a full partner in social interaction' (Fraser, 1998: 3). In Fraser's conception of social justice, misrecognition results in injustice. From this perspective, heteronormative dispositions do not promote social justice or, said differently, are unjust. If, as explained earlier, heteronormativity assumes two sexes (male and female), with gender operationalised as a binary, heteronormative dispositions are reinforced by default and thus promoted.

Nancy Fraser's (2000) conceptualisation of social justice as full recognition, whereas misrecognition infers injustice, provides a basis for drawing out implications of binary gender operationalising reinforcing heteronormative dispositions. In other words, Fraser's concept offers an explanatory framework for understanding the consequences of operationalising gender as a binary in quantitative research related to teaching and learning.

When one is misrecognised, one is 'denied the status of a full partner in social interaction' (Fraser, 1998: 3). In the face of widespread gendered inequality in educational achievements, reporting that focuses on the gender binary makes sense. However, does such reporting maintain unnecessary and unjust social constructions that may impinge on social justice in unintended ways? If, because of a binary conception of gender, individuals who either cannot or will not identify in those binary terms are misrecognised, social justice in Fraser's conceptualisation will not be achieved. If that binary approach to gender simultaneously locks the global community into a particular understanding of the world that is gendered, to what extent is society able to transcend that?

Fraser (1998) contends that redressing gender equality requires that attention be paid to recognition. Recognition 'is a remedy for injustice' (Fraser, 1998: 5). Recognition, according to Hegel, refers to 'an ideal reciprocal relationship between subjects' (Fraser, 2000: 109). One becomes an individual subject in the process of recognising and being recognised (Fraser, 2000). Achieving justice by recognition depends on what and how the misrecognition is occurring (Fraser, 1998). Recognition is therefore not generic but context-specific in Fraser's (1998: 5) perspective. Recognition is as fundamental as economic redistribution to social justice for Fraser (1998). Fraser (1998: 4) asserts that for everyone, regardless of sex, sexual orientation, class, ethnicity, geographical location and so forth to reach 'parity of participation', it is not enough to seek economic redistribution. To ensure participation on par with others, equal importance should be attached to guaranteeing socio-cultural remedies of recognition as full partners in social interaction (Fraser, 1998: 3).

For Fraser, recognition in the context of justice entails

that everyone has an equal right to pursue social esteem under fair conditions of equal opportunity ... such conditions do not exist when, for example, institutionalized patterns of interpretation pervasively downgrade femininity, "non-whiteness", homosexuality, and everything culturally associated with them. (1998: 4)

If and when such patterns [institutionalised patterns of cultural value] constitute actors as peers, capable of participating on par with one another in social life, then we can speak of reciprocal recognition and status equality (Fraser, 2000: 113).

When actors are constructed as invisible and less than full partners, this is misrecognition and status subordination (Fraser, 2000: 113). With reference to the topic at hand, operationalising gender as a binary equates to recognition of male and female. By implication, those who do not conform to the gender binary are not recognised as peers and are not capable of participating on par with others in social life. The politics of recognition seeks a difference-friendly world 'where assimilation to majority or dominant cultural norms is no longer the price of equal respect' (Fraser, 1998: 1). Fraser contends that 'it is unjust that some individuals and groups are denied the status of full partners in social interaction simply as a consequence of institutionalized patterns of cultural value in whose construction they have not equally participated, and which disparage their distinctive characteristics or the distinctive characteristics assigned to them' (1998: 3).

Misrecognition is the denial of recognition by others and distorts one's relationship to oneself and others (Fraser, 2000). Misrecognition is therefore 'a status injury' or 'status inequality' (Fraser, 2005: 5, emphasis in original). When one is misrecognised, one is 'denied the status of a full partner in social interaction' (Fraser, 1998: 3). A consequence of misrecognition is that it denies affected individuals and groups the chance of participation on par with others (Fraser, 1998). In other words, 'institutionalised hierarchies of cultural value ... deny them the requisite standing' (Fraser, 2005: 5). When one is associated with a group that is misrecognised, it distorts one's sense of self (Fraser, 2000).

As a result of repeated encounters with the stigmatizing gaze of a culturally dominant other, the members of disesteemed groups internalize negative self-images and are prevented from developing a healthy cultural identity of their own (Fraser, 2000).

From Fraser's perspective of social justice through recognition, quantitative research approaches that operationalise gender as a binary make it difficult for individuals who do not identify with those binaries to participate on par with those who do. From this perspective, violence meted out against those who do not conform to binary gendered expressions, discussed earlier, continues to be unjust but is less surprising as it can be explained.

The next section of this paper reviews the DHET's approach to operationalising gender when describing teaching and learning trends and considers the implications for the promotion of heteronormative dispositions and social justice.

Approach to operationalising gender in teaching and learning trends

Garvey, et al. regard higher education survey instruments as 'systems of knowledge' that have great influence and require attention (2019: 196). Data gathered for the DHET to understand trends in teaching and learning do not emanate from a survey instrument in the conventional sense. The data are gathered for the purpose of keeping track of, or monitoring, demographic distributions in higher education institutions. Nevertheless, a variable is operationalised and can contribute to building knowledge in the field; and the data gathered can influence policy decisions, as outlined above.

The DHET requires higher education institutions to report on pre-determined variables in the Higher Education Management Information System (HEMIS). Institutions therefore gather data via HEMIS for compliance and to secure funding (DHET, 2021a). Significantly, HEMIS operationalises gender in line with Statistics South Africa's (StatsSA1's) definition of the 'social distinction between males and females' (DHET, 2021a: 129).

Informed by StatsSA's definition, the HEMIS gathers data on gender as a binary (CHE 2020: 12). There is thus a binary approach to operationalising gender. All data used to illustrate whether the DHET has reached its goals emanate from the HEMIS (DHET, 2020b). This means that data used to demonstrate trends related to teaching and learning in higher education operationalise gender as a binary. Consequently, all trends relating to teaching and learning reported by the DHET that are disaggregated by gender do so in binary form. Examples are presented in a DHET (2021b) publication focused on an analysis of gender of students in PSET (Post School Education and Training) institutions. Tables and figures that analyse student enrolment and graduation by gender and by major field of study and qualification type, operationalise gender as a binary (DHET, 2021b).

Statistics drawn from these data are used to determine plans and report on the state of the sector (DHET 2020a, 2021a). DHET (2020a) states that there are 40% more females than males enrolled in institutions. When the data about teaching and learning outcomes are reported at national level, gender is reported on as a binary (DHET 2021a). Examples can be observed in a DHET (2021a) publication that analyses student data in PSET (Post School Education and Training) institutions. Tables and figures that analyse student enrolment and graduation by gender and by attendance mode and qualification type, operationalise gender as a binary; female and male (DHET, 2021a). Figure 2 extracted from this DHET (2021a: 21), below, is one illustration of how gender is reported on as a binary by field of study and qualification type.

We could not locate an example gender represented in any way in statistical analysis by DHET (2020a, b; 2021a, b)

South Africa is not unique in this regard. Trends regarding teaching and learning at international or global levels also report on gender as a binary (UNESCO, 2020; DHET, 2021a). UNESCO (2018: 10) acknowledges that equal 'opportunities between males and females, notably in terms of participation and learning outcomes, is necessary but not sufficient for realizing gender equality in education' but does not problematize the binary manner in which reporting occurs.

National government reporting is guided by the HEMIS (CHE, 2020: 13-14). To reiterate, reporting systems such as the HEMIS cannot be compared or equated to quantitative research exactly. However, the data are in a numeric format and are used by researchers to make contributions to knowledge from a quantitative perspective. Examples of reports and literature that draw on HEMIS data report on gender as a binary (Essop, 2020; Van Broekhuizen, et al., 2016) contributing to knowledge in the field of trends in teaching and learning outputs. Essop (2020) analyses headcount enrolment and throughput rates by gender, referring to the difference between male and female students only. Van Broekhuizen, et al. (2016) report on enrolment, dropout and bachelor passes by gender, distinguishing between males and females only.

The South African Student Engagement annual report (UFS, 2016) also reports on gender as a binary. A recent report from the DHET (2020b) drew on an instrument that operationalised gender as 'Male', 'Female', 'Another gender identity' and 'I prefer not to answer'. However, the report only mentions that two thirds of the sample were female (DHET, 2020b). In other words, although the gender variable is operationalised in a manner that recognises non-binary gender categories, the report does not recognise the individuals who responded to those categories.

The necessity to report to the HEMIS guides institutional practices in this regard. As explained, education institutions are important mechanisms for inserting ideas and debates into the public sphere and in so doing generating public opinion (McDonald, 2013). The ideas and debates that are established in the public sphere by education institutions could be regarded as public pedagogy to the extent that individuals are instructed and can learn from such data collection. This learning might not be intentional or part of the formal curriculum; it might, however, be no less effective. Public pedagogy is used to refer to learning outside of formal educational institutions, such as schools (Sandlin, et al., 2010). To the extent that public pedagogy relates to learning outside formal education institutions, it has a complicated and vast reach (Sandlin, et al., 2010). Moreover, there are positive and negative associations made with public pedagogy (Sandlin, et al., 2010). Sandlin, et al. (2010), however, focus on public pedagogy that is critical, while in the case presented here public pedagogy, to the extent that it impacts on learning beyond formal education institutions, could reproduce hegemonic narratives.

Heteronormative dispositions are learnt from social interactions and activities. In the example given below, the University of Johannesburg (UJ) is not gathering data for a quantitative research project. The purpose of the online form is the basis of the application process. This information however feeds into the HEMIS system and can be used in quantitative approaches to contributing to knowledge and understanding about teaching and learning. As can be seen below, when applying to UJ an individual has to identify as female or male.

Any applicant wishing to have their gender recognised in a non-binary manner would gather from the online application process that this is not possible at this higher education institution. We can only guess what applicants would learn from this experience. This paper has argued that binary operationalisation of gender contributes to cementing heteronormative dispositions in society and, in so doing, the misrecognition of individuals who do not identify with binary gender categories. This results in injustice from the perspective of Fraser's conception of social justice.

Not all institutions capture gender in the first part of the application process or in the same way as UJ does. As shown below, Stellenbosch University, for example, captures gender via title and does allow for non-binary identification.

A prospective student can select 'Mx' as their title, implying a non-binary gender category. Even if, for the purpose of the HEMIS, the student would have to be either male or female at a later stage, the institution does recognise non-binary gender categories and, in so doing, disrupts heteronormative dispositions. Thus, although institutions have to report to the HEMIS in a specific way, they are able to recognise gender categories beyond binary modes at the institutional level. When their trends related to teaching and learning are reported on at the national level, this recognition would however not add to our understanding of the phenomenon. At the national level, trends in teaching and learning regarding gender are understood within binary categories. In other words, the DHET's statistics 'interpret reality and influence the way we understand society' (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 7) within a heteronormative framing of gender. Misrecognition of non-binary gender categories at the national level reinforces binary expressions of gender and a heteronormative disposition in the public sphere.

Lennon and Alsop (2020: 6) contend that children find this situation particularly difficult, and that society needs to be able to 'let them be' and position themselves wherever they would like to be on the gender spectrum. When individuals are forced, as in the UJ example above, into recognising themselves in specific ways, what could they be learning? Could they be learning that the recognition into which they are forced into is socially accepted? Could they be learning that the recognition into which they are forced has to be forced upon others? To what extent will society be able to let children, or young adults, be when individuals are forced to recognise themselves in particular ways?

Conclusions

This paper has interrogated the extent to which gender operationalisation, specifically related to teaching and learning trends in South African higher education, promotes heteronormative dispositions and the consequent implications for social justice. The paper first described the process of variable operationalisation in quantitative approaches relating to statistical analyses. It then explained the dynamics of gender operationalisation and offered a perspective on social justice that foregrounds recognition, where misrecognition constitutes injustice. The paper argued that heteronormative dispositions are premised on misrecognising non-binary gender identities. Viewed through this lens, heteronormative dispositions are not conducive to social justice. The paper showed that the DHET, via the HEMIS, uses binary gender categories to gather data. The HEMIS is the DHET's mechanism for gathering comprehensive data about teaching and learning trends in South African higher education.

This means that expressions of non-binary gender categories are misrecognised in how trends in teaching and learning are understood in the system. By misrecognising non-binary gender categories, male/female categories are reinforced, and heteronormative dispositions are cemented through evidence, discourses, and debates about trends in teaching and learning. 'In a straightforward Foucauldian sense statistics - and official statistics in particular - operate as a powerful truth claim in most modern societies' (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 9). The contention is that binary gender categories used to gather data about teaching and learning act as a pedagogic device that contributes to holding heteronormative dispositions firmly in place.

Statistics are powerful persuaders. As systematically collected numerical facts, they do much more than summarize reality in numbers. They also interpret reality and influence the way we understand society (Walter & Andersen, 2013: 7).Smaller scale quantitatively informed research does break with the binary expression of gender, breaking gender down into 'male', 'female', 'non-binary' or 'other' (Ojo & Onwuegbuzie, 2020; Seutloali & McDonald, 2021). The research reports very low response rates for the non-binary categories. Under conditions of small response rates, statistical analysis is of course challenged. Small response rates are on the other hand not uncommon in survey and questionnaire data. Ultimately, the choice lies with the researchers who design quantitative research instruments to operationalise variables that will either recognise or misrecognise the full range of gender expression.

What does this mean in practice and for social justice in teaching and learning? What does it mean for the manner in which research ontologies frame and shape particular epistemological approaches of researchers and respondents? What does it mean when non-binary gender categories are misrecognised, and heteronormative dispositions are reinforced through data gathered about teaching and learning? Such data provides the basis of evidence to support future policy and decision-making. What does this say about the official pedagogy of the South African state and of international agencies? Walter and Andersen (2013: 16) state that '[a]ll quantitative methodologies are historical, cultural, and racial artifacts - they cannot be otherwise'.

If in operationalising a variable, individuals' identities are misrecognised, particularly minority ways of identifying, what could this mean in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution which is meant to be guided by algorithmic calculations? How intelligent will artificial intelligence be if variables are operationalised without rigorously interrogating their fundamental assumptions and contribution to social justice?

A major implication of the argument put forward here is that researchers and policy makers must pay closer attention to how gender is operationalised to collect data. In the absence of historical gender inequalities related the outcomes of education and thus teaching and learning, it might have been possible to propose that data on gender ought not to be gathered. In that way, no category could be misrecognised. However, access by and success of female students is an important dimension of social justice; as a consequence, data are required to track this phenomenon (DHET, 2021b).

Within the context of this data requirement, thought and consideration ought to be given to how gender is operationalised. In pursuit of social justice, recognition ought to be balanced, fair and, above all, must not violate expressions of certain identities. Adding many different categories to the gender variable could amount to statistical heresy and would, no doubt, muddy the waters of inferential statistics. Where 'unjust' variable operationalisation cannot be avoided, the least that can be done is to declare the injustice and explain its necessity.

Misrecognising identities such as gender when variables are operationalised has implications for analytical rigour and knowledge production. The ability of quantitative research to provide for all gendered identities highlights the importance of taking seriously ethical sensibilities in relation to data collection and analyses and to the outcomes and implications of data collection. If knowledge of the social world is hamstrung by statistical formulas, what is the condition of social science?

Providing for non-binary recognition of gender in quantitative research conducted related to teaching and learning is a challenge. However, given its public pedagogical implications, it is a matter of social justice. This paper does not address research in a moment of social disruption but rather seeks to disrupt research processes which could be exclusionary and promote injustice, and thus interrupt socially just disruptions, specifically as it relates to gender.

Author biographies

Zahraa McDonald is currently a Research Associate with the South African Research Chair in Teaching and Learning at the University of Johannesburg. She is also a researcher at JET Education Services. Subsequent to completing her PhD in Sociology at UJ her research has focused on education in South Africa.

Shireen Motala is a Professor in the Faculty of Education at UJ. She is currently the South African Research Chair in Teaching and Learning (SARChI T&L). Prior to being awarded the Chair, Prof Motala was the Head of the Postgraduate School (PGS) at UJ. She is a member of the Academy of Science in South Africa (ASSAf).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our thoughtful reviewers, Michael Cross and the Ali Mazrui Centre for Higher Education Studies.

References

Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

CHE. 2020. VitalStats Public Higher Education 2018. Pretoria: Council on Higher Education. [ Links ]

CHE. 2021. VitalStats Public Higher Education 2019. Pretoria: Council on Higher Education. [ Links ]

DHET. 2020a. Strategic Plan 2020-2025. Pretoria: DHET. [ Links ]

DHET. 2020b. Students' Access To and Use of Learning Materials. Pretoria: DHET. [ Links ]

DHET. 2021a. Statistics on Post-School Education and Training in South Africa. Available at: https://www.dhet.gov.za/SiteAssets/StatisticsonPost-SchoolEducationandTraininginSouthAfrica%2C2019.pdf (Accessed 6 June 2022).

DHET. 2021b. Fact sheet on gender for students in PSET institutions. Available at: http://www.dhet.gov.za/Planning%20Monitoring%20and%20Evaluation%20Coordination/Fact%20 sheet%20on%20gender%20for%20students%20in%20PSET%20institutions.pdf (Accessed 6 June 2022).

Essop, A. 2020. The changing size and shape of the higher education system in South Africa, 2005-2017. Ali Mazrui Centre for Higher Education Studies. Available at: https://heltasa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Size-and-Shape-of-the-HE-System-2005-2017.pdf (Accessed 24 July 2020).

Fraser, N. 1998. Social justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition, participation. WZB Discussion Paper, No. FSI 98-108.

Fraser, N. 2000. Rethinking recognition. New Left Review, 3: 107-120. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. 2005. Reframing Justice in a Globalizing World. New Left Review, 36: 1-19. [ Links ]

Garvey, J. C., Hart, J., Metcalfe, A. S. & Fellabaum-Toston, J. 2019. Methodological troubles with gender and sex in higher education survey research. The Review of Higher Education, 43(1): 1-24. [ Links ]

Heinrich Böll Stiftung. 2021. 21 April 2021 Joint Statement: Spate of Hate Crime Murders -LGBTIQ+ People Say More Needs to be Done. Available at: https://za.boell.org/en/2021/04/22/21-april-2021-joint-statement-spate-hate-crime-murders-lgbtiq-people-say-more-needs-be (Accessed 23 March 2021).

Lennon, K. & Alsop, R. 2020. Gender Theory in Troubled Times. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

McDonald, Z. 2013. Expressing post-secular citizenship: A sociological exposition of Islamic education in South Africa. Unpublished PhD diss., University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

NPC. 2012. National Development Plan 2030. Our future - make it work. Available at: (Accessed 6 September 2021)

Ojo, E.O. & Onwuegbuzie, A.J. 2020. University life in an era of disruption of COVID-19: A meta-methods and multi-mixed methods research study of perceptions and attitudes of South African students. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 12(1): 20-55. [ Links ]

Sandlin, J.A., Schultz, B.D. & Burdick, J. 2010. Understanding, Mapping, and Exploring the Terrain of Public Pedagogy. In Sandlin, J.A., Schultz, B.D. & Burdick, J. (eds.) Handbook of Public Pedagogy. Education and Learning Beyond Schooling. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Seutloali, M. & McDonald, Z. 2021. Factors influencing undergraduate students' attitudes towards blended learning. Peak performance Conference. University of Johannesburg, 30 April 2021.

Smuts, L., Reijer, J. & Dooms, T. 2015. Perceptions of sexuality and gendered sexual roles among students at a South African university: Exploring heteronormativity on campus. Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 6(1), 65-75. [ Links ]

SU (Stellenbosch University). 2021. Create your profile. Available at: https://student.sun.ac.za/signup/ (Accessed 3 April 2021).

Tuli, F. 2010. The basis of distinction between qualitative and quantitative research in social science: Reflection on ontological, epistemological and methodological perspectives. Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences, 6(1): 97-108. [ Links ]

UFS. 2016. Engaging the #studentvoice. Available at: https://www.siyaphumelela.org.za/documents/SASSE%20Report%202016.pdf (Accessed 5 April 2021).

UJ (University of Johannesburg). 2021. Comprehensive Web Application Process. Available at: https://registration.uj.ac.za/pls/prodi41/gen.gw1pkg.gw1proc (Accessed 3 April 2021).

UNESCO. 2018. Global Education Monitoring Report Gender Review. Meeting our commitments to gender equality in education. Unesco. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261593 (Accessed 2 April 2021).

UNESCO. 2020. Global education monitoring report. A new generation: 25 years of efforts for gender equality in education. Unesco.Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374514 (Accessed 10 March 2021).

Van Broekhuizen, H., Van Der Berg, S. & Hofmeyr, H. 2016. Higher education access and outcomes for the 2008 national matric cohort. Working papers, 16. Stellenbosch University, Department of Economics.

Walter, M., & Andersen, C. 2013. Indigenous Statistics: A Quantitative Research Methodology. California: Left Coast Press. [ Links ]

Submitted: 1 February 2022

Accepted: 27 June 2022

# Corresponding author: zahraam@uj.ac.za

1 Stats SA is the South African state's official statistical agency and is tasked with conducting the national census as well as compiling national statistics related to the labour market and household socio-economic and status.