Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.54 n.1 Pretoria Apr. 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3383/2024/vol54no1a2

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Clinical evaluation, useability, and utility of the Work Ability Screening Profile II (WASP II)

Denise FranzsenI; Thavanesi GurayahII; Kerry MagillII; Patricia de WittI

IOccupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. Denise Franzsen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8295-6329. Patricia de Witt: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3612-0920

IIOccupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Thavanesi Gurayah: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9005-6355. Kerry Magill: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9160-5483

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The Work Ability Screening Profile (WASP) was conceptualised and developed by occupational therapists at the University of Durban Westville to provide a basic vocational screening assessment. Its purpose was to screen competence in generic work skills which reflected performance in activities essential to workplace participation relevant to the South African context. The assessment was revised in 2005 and renamed the WASP II. It was decided this screening assessment tool would be continuously reviewed using action research with clinicians involved in the ongoing evaluation so ensure validity and reliability for the population with which it is used. This study considered the clinical evaluation, useability and utility of the WASP II in order to inform further revision.

METHOD: A cross sectional survey was used to gather data from 70 occupational therapy clinicians familiar with or using the WASP II in clinical practice.

RESULTS: A sample of 70 respondents indicated the WASP II was suitable to assess current work ability and production speed with a variety of clients with physical and mental health dysfunction. Ten of the 12 subtests were used by at least 40% of the time by the 28 respondents who used the WASP II frequently. These respondents reported good to adequate useability in terms of cost, sensitivity to clients' educational level and ease of understanding instructions, incorporation into clinical practice contexts while supporting clinical reasoning and judgement. The accommodation of clients' language and provision of standard scores were indicated as inadequate. Utility was considered adequate for all aspects including discrimination of moderate to severe dysfunction, informing the choice of other assessmentsas well as supporting vocational rehabilitation intervention. The WASP II outcomes were also understood by other service providers, employers, referring parties as well asclients.

CONCLUSION: While the WASP II was considered appropriate for use in the South African context and has adequate useability and utility, some subtests need to be updated and revised in terms of the standard times and content validity for current practice in the work environment.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE:

The WASP II has useability

• aligned with generic work skills of acquiring information or following directions numeracy, conveying information and written communication

• for with those with work experience and with scholars and students yet to enter the workplace

The WASP II has utility in relation to

• cost and clients' educational levels

• detailed instructions on the task layout but some standardisation needs to be interpreted with care

• sensitivity to all aspects of assessment of generic work skills, except discrimination of mild dysfunction

Keywords: generic work skills, standard scores for ability (productivity), South African work context, screening assessment tool

INTRODUCTION

Vocational rehabilitation has been included in the Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Amendment Bill in 20201 and makes provision for funding for these multidisciplinary services for workers injured on duty by the Department of Employment and Labour in South Africa. These services may be offered by occupational therapists2, to a diverse client base due to multicultural, educational, political and socio-economic diversity within the country.

It is essential that a work assessment for dysfunction related to work, or to prevent work dysfunction from occurring is customised for each individual, be it preparing for the worker role, returning to work, or being considered for an alternate work role. This is due to the individual nature of clients, their work capacity and work interests, experiences and capacities and illness/disability limitations related to various job demands3. Relevant general or basic work skills or prevocational skills need to be screened to gain an initial indication of the individual's work abilities to assist in the selection of appropriate vocational assessments to evaluate specific work skills4. In South Africa, this presents challenges for assessing generic work skills due to a lack of locally standardised work assessments.

The need for a basic vocational screening assessment to screen generic work skill competencies reflecting performance in activities essential to workplace participation5 relevant for the South African context was expressed by occupational therapists in KwaZulu Natal as far back as 19955. The high cost of available work assessment screening instruments (most of which had been standardised in the global north), could not be justified in the light of other health and rehabilitation needs6. In addition, the imported tests were not found to be culturally or language-impartial for the local population served7. Clinicians believed that rather than just observing general activity participation as a screening for work ability, they required a more contextually relevant, valid and reliable screening tool with evidence-informed scores6. This was essential to substantiate findings in reports and criteria to support more comprehensive assessment8.

Led by Sue Barnard, a team of lecturers and students from the University of Durban Westville (now University of Kwa-Zulu Natal (UKZN), clinicians from KwaZulu Natal's public sector occupational therapy departments treating patients with psychiatric, neurological, and physical dysfunction, as well as occupational therapists in private practice considered experts in the field of vocational rehabilitation, collectively developed a series of job samples in subtests. These subtests considered components necessary for work ability screening. Approximately three weeks was spent constructing a series of job samples which included basic work tasks typical within the South African work context8,which collectively became the prototype named the Work Ability Screening Profile (WASP I)8.

General work requirements including memory, concentration, decision making, judgement, organising and planning, motor abilities, co-ordination, dexterity, following of instructions and dynamic postures (which were later reflected in the 'activities' component of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)9, were determined for each of the tasks included in the WASP I screening battery. Tasks to evaluate some psychosocial components such as client perceptions of stress, time management and issues in their work situations were also included in the battery8.

Scores for both ability (competence) and speed (productivity) were compiled. Lack of ability was judged on the number of errors made during the task execution. Speed was measured using Modular Arrangement of Predetermined Time Standards (MODAPTS)10 which allows for the comparison of a clients' performance against the time taken by an average competent worker completing the screening assessment tasks. Detailed information on the structuring of each screening assessment task was provided so as to conform to the speed standards provided8. All subtests were designed to be standalone, and therapists could choose to administer subtests that suited the client's needs. Moreover, the screening provided a baseline for further in-depth testing and designing of vocational rehabilitation intervention programmes8. The reliability and validity of the WASP I was not researched. The occupational therapists used their clinical skills and experience to interpret test performance6.

The WASP I was revised and published as the WASP II in 2005. Decisions regarding the revisions were based on the clinical experience of using the WASP I by a team of three experienced occupational therapists working in vocational rehabilitation and academia. Changes that were made included adding and removing tasks in the subtests, changing times and scoring in some job samples8. In the WASP II, it was made clear that not all subtests were timed, and these subtests reflected ability scores alone. There were plans to develop more specific tasks for particular occupations to add to the WASP II but these plans were not followed up so only the 12 job samples which screen basic work skills were retained8. To facilitate the ongoing development of the screening assessment it was decided the WASP II would be continuously reviewed using action research with clinicians involved in the ongoing evaluation and revision of the screening assessment. This process was anticipated to allow the occupational therapist to screen for capability consistent with criteria based on standards and competence measured using accuracy appropriate to the South African employment context8. The purpose of this action research was to evaluate the appropriateness of the screening instrument in terms of theoretical and empirical evidence of validity, reliability, and compatibility with local service delivery, needs and population fit11.

The WASP I and WASP II have been produced and sold by the University of KwaZulu Natal since 1995 and 2005 respectively8. Although many kits were purchased, the assessment has not been systematically evaluated and the useability and clinical utility of the WASP II to screen clients in current occupational therapy practice in South Africa has not been determined.

Literature review

The purpose of any screening battery is to identify those at risk of poor performance in various domains related to work, and participation differences amongst referred clients, to determine if a detailed vocational evaluation is required using appropriate, reliable and valid standardised tests.

The evaluation of a screening assessment such as the WASP II is contingent on the purpose for which it is used. The WASP II at present is used clinically as a diagnostic tool12 to evaluate the nature and extent of a client's deficits in generic work skills or prevocational skills based on their level of education.

The assessment also has the potential to be used as a work readiness assessment13 to determine what prevocational skills have been consolidated, and which need to be further developed, for example with adolescents who are required to transition into the workplace14. There are other standardised screening assessments which evaluate generic work skills but do not include the components assessed by the WASP II. Two examples are the Assessment of Work Performance (AWP)15 and Work Ability Index (WAI)16. The AWP15 is an activity-based assessment of a client's work ability skills when performing any work activity in real-life and other settings where findings are reported in relation to body structure, as well as motor skills, process skills and communication skills. Three specific structured simulated work tasks have been added to the AWP and this specific application instrument is called the AWP-SA17. The WAI also screens aspects affecting work but is a self-report questionnaire which includes one section on mental capabilities for work16.

Literature indicates the following guidelines be used for the evaluation of universal screening assessments: The targeted domain, constructs and the format of the screening assessment must be clearly defined. Clarity on whether the screening assessment needs to be used in its entirety, how information will be obtained, as well as how often the assessment should be administered must be justified. The clinical useability and utility of the screening assessment should be determined11.

Useability

Even if a screening assessment has been shown to be valid and reliable, aspects such as feasibility of the administration, identification outcomes, and compatibility with local service delivery needs must be ensured6. Smart (2006)18 conceptualised clinical utility under four constructs for interventions in the workplace: appropriateness, relevance, practicality and accessibility in terms of cost. Appropriateness is related to how effective the assessment is and how it fits into the existing intervention process which includes formal evidence for the use of the assessment. Relevance relates to the impact it has on treatment and clinical decision-making. A screening assessment should be able to identify difficulties that an individual currently experiences19 across the working age bands and with both acute and chronic conditions. The WASP II has been used with subacute and chronic multi-diagnostic clients from 15 years to 65 years. The assessment was designed to accommodate persons with a wide range of educational backgrounds, although some job samples require a basic level of literacy, and no work experience is required. The WASP II has been used to screen clients for medicolegal and insurance claims and return to work situations. Additionally, it has also been found to be suitable for screening of prevocational skills for scholars and for job seekers8.

The practicality of the screening assessment considers the administration setting, training required, time efficiency, scoring complexity as well as accessibility in relation to the cost relative to the benefits of identifying dysfunction20. The WASP II is accessible in terms of the cost of administration and cost-effectiveness in reusing materials18. The subtests must be administered by an occupational therapist and their professional knowledge and experience are required for observations to support the scores obtained and in interpreting the results. Practicality in the administration of all job samples in the WASP II in terms of the completeness of the instructions have been addressed and the job sample layout is standardised irrespective of the position of the therapists in relation to the client during testing. The scoring is relatively simple since ability and speed are scored on a 5-point scale with a rating of 5 indicating above average performance and with a rating of 1 indicating severely impaired performance8.

Utility

The utility of an assessment determines acceptability to all stakeholders, including the clients, their family, the multidisciplinary team, employers, legal experts and insurance companies for meaningful impact on service delivery18. All stakeholders should be able to understand the implications, consequences and outcomes of the screening assessment. In the WASP II all subtests are presented in English and a translator may be used to explain the instructions if the client's first language is not English, but no formal translation of these instructions is available. Knowledge of appropriate further assessments, interventions and work accommodations needed are based on the screening are also important. Screening without the opportunity for further, more comprehensive assessment, intervention planning and service delivery is a waste. It can result in the unnecessary labelling of clients as disabled, which may impact their ability to achieve future outcomes18.

Recommendations as a result of the screening assessment should be feasible and contextually relevant20. This includes the ecological validity of the screening assessment in relation to real-world tasks and real-world functioning in employment21. To improve the relevance of the WASP II, job samples were based on South African educational norms and 12 job samples which reflect generic abilities required in many occupations were assessed8. WASP II was designed to screen sample behaviours in a context other than the workplace. The choice of administering only some subtests or tasks relevant to the client allows for a client-centred approach18 and the effect of testing on the clients themselves, can be monitored by the occupational therapist22. The WASP II can be administered to one client or in a group of up to five clients at a time. The WASP II can also be administered according to the client's level of endurance, for example, a few job samples a day i.e., 2/3 or more/ up to 5/6 at a time8.

METHODOLOGY

Study design

This study used a quantitative, descriptive and cross-sectional survey design. A questionnaire was used to gather data to describe the use of the WASP II and the reported useability and utility of the WASP II in occupational therapy services.

Population and Sampling

Occupational therapists living and working in South Africa who are members of the Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa (OTASA) or who had purchased the WASP II constituted the population for this study. Convenience and snowball sampling were used. Participants who received the survey were asked to forward it to other occupational therapists they knew who had experience using the WASP II.

Since the number of occupational therapists who have had experience using the WASP II was unknown, based on the fact that 100 occupational therapy practices/departments had bought the WASP I and II, it was estimated that a sample of 55 participants was required to be representative of this population, with a 5% margin of error accommodating for a small sample size, according to Cochranes formula23.

Research Instrument

An online questionnaire for occupational therapists was specifically developed by the researchers to evaluate the characteristics of the WASP II, as well as the useability and utility in clinical settings. The questionnaire incorporated questions similar to those used in a published study for determining the utility and useability of another instrument24. The questionnaire included both closed and open-ended questions.

The questionnaire was piloted for content validity and relevance by occupational therapists familiar with the WASP II, but who were not presently using the WASP II in their practices. Five occupational therapists with experience in questionnaire development and familiar with vocational assessments were purposively selected and requested to comment on the relevance, clarity and ambiguity of the questions25. In addition, they were asked to propose any other questions that should be included in the questionnai26. Eight questions did not achieve a score of 0.8 on the Content Validity Index (CVI) and these questions were therefore removed.

Research Procedure

The questionnaire, the information letter and consent to participate was distributed on an electronic link on the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system27 via the OTASA platform and individually to occupational therapy departments based on the UKZN's purchase records of the WASP II. Those receiving the survey were asked to forward it to other occupational therapists practicing vocational rehabilitation26 who were not members of OTASA.

The participants were given a month to respond. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from University of KwaZulu Natal Humanities and Social Sciences research ethics committee.

Data Analysis

Demographic and contextual factors, as well as all questions on the questionnaire, were analysed using frequencies and percentages. The open-ended questions were analysed using summative analysis and comments were identified as positive or negative responses.

RESULTS

Seventy-seven respondents completed the questionnaire, but only 70 questionnaires were analysed as seven were i ncomplete.

Demographics of the sample

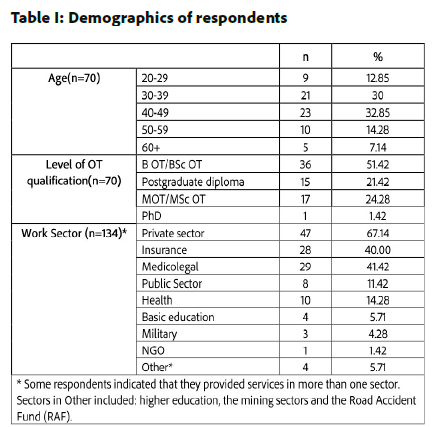

As seen from Table I (below) the greatest number of respondents were between the ages of 40-45 years, with nearly half of respondents having postgraduate training or postgraduate degrees.

Respondents reported having completed additional training courses on vocational assessment, ranging from postgraduate courses, MODAPTS Plus courses to webinars. Over 40% of respondents had more than 10 years' experience in vocational rehabilitation.

Evaluation of the WASP II

Respondents provided services to more than one type of client in their clinical practices, with more than 80% providing services to clients with physical impairments and more than 60% providing services to clients with mental health concerns. Disability assessments for the Road Accident Fund (RAF) and Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa (PRASA), as well for medical negligence cases were included under 'Other' in the answers.

The WASP II was used most frequently with the clients' presenting with traumatic brain injuries (27%) and upper limb and hand injuries (26%). Forty two percent of respondents indicated they screened clients with depression, schizophrenia, bipolar mood disorder and anxiety using this screening assessment. Other clients included neurological conditions, such as stroke, spinal cord injuries, learning disabilities and intellectual disabilities. The WASP II was found to be suitable irrespective of the first language (11%), as well as for clients with no previous work history (20%), and for acute or chronic conditions (59%), but was least useful for a client with visual deficits.

Respondents reported that the subtests of the WASP II were used most frequently to screen/assess current work ability (42%) and production speed (71%), and least frequently for work placement in new /alternative jobs (14%). The results of the WASP II were used in reports for insurance companies (29%), employers (21%), and medico-legal associates (20%).

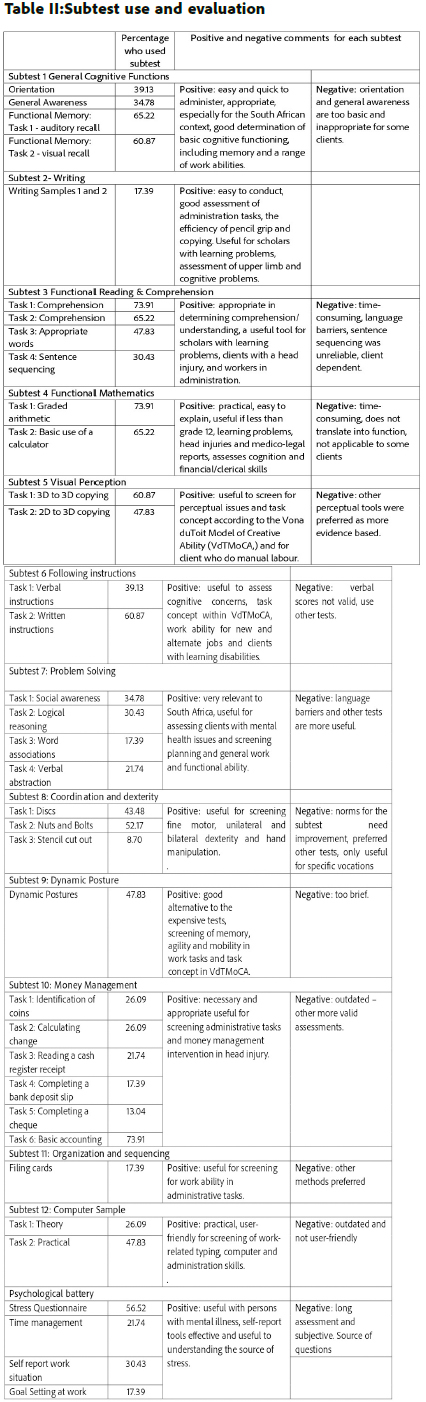

Only 26 of the 70 respondents who used the WASP II in clinical practice felt they were familiar enough with the WASP II to answer section 2 of the questionnaire. Results for these participants are presented in Table II (below). The analysis of open-ended questions on each subtest indicated the appropriateness of the subtests for the South African context are also reported in Table II (below). Ten of the 12 subtests were used by more than 40% of the respondents. Tasks for comprehension, graded arithmetic and basic accounting were used by the highest percentage (73.91%) of respondents.

WASP II useability and utility

Useability

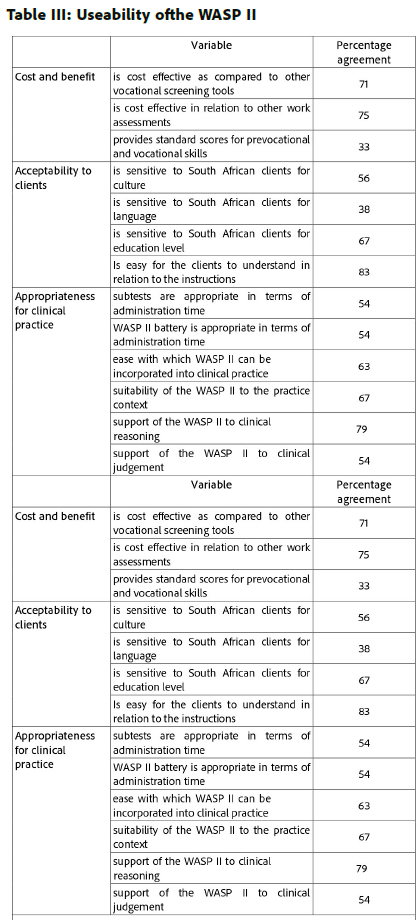

The useability of the WASP II is presented in Table III (page 11). The majority of respondents agreed the WASP II was cost-effective, was sensitive to clients' educational level and the instructions were easy for the clients to understand. They also agreed the WASP II could easily be incorporated into clinical practice, was suitable to their practice context and supported their clinical reasoning. Fewer respondents agreed that administration time was appropriate, and the WASP II supported their clinical judgement. Only a third of respondents agreed that the WASP II provided standard scores for prevocational and vocational skills and was sensitive to the client's language.

Utility

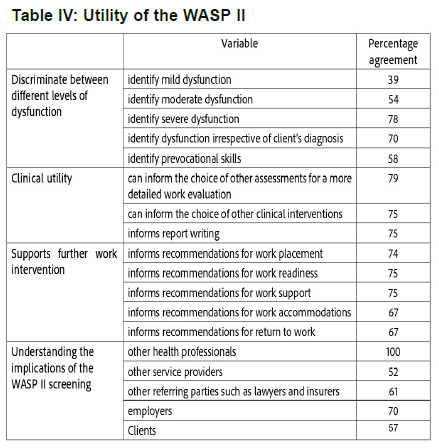

While only a third of respondents agreed that the WASP II could identify mild dysfunction, between 67% -79% agreed that the screening assessment supports all other utility items, including discrimination for a severe level of dysfunction, informing the choice of other assessments and intervention, and supporting vocational rehabilitation intervention. Fewer respondents agreed that the WASP II outcomes were understood by other service providers, referring parties such as lawyers and insurers, as well as clients, although most indicated this was not an issue for other health professionals and employers (Table IV below).

DISCUSSION

Data for the study were collected from a heterogeneous group of occupational therapists providing vocational rehabilitation services to clients with different conditions in a variety of settings. Nearly half of the respondents in this study could be considered experienced clinicians as they had postgraduate qualifications and have been practicing in vocational rehabilitation for more than 10 years. Data can therefore be assumed to reflect the views of occupational therapists familiar with the WASP II screening assessment.

Most respondents reported selecting subtests on the WASP II that were aligned with individual client needs. Aspects of general work skills such as on-task behaviour, quality of work performance, work rate and errors28 were assessed on all tasks in the WASP II except for the psychosocial battery.

The administration of the entire screening assessment and some subtests were considered inappropriate in terms of administration time by nearly half of the respondents, and mostly only one or two tasks within the subtests were administered in an assessment. The most frequently used subtests were: Functional reading and comprehension, Functional mathematics, Following instructions and Money management. The tasks for comprehension, graded arithmetic, basic accounting, use of a calculator and following written instructions were all used by more than 60% of respondents. The premise for assessing generic or general work using practical tasks, which are required in many work settings, was supported since these tasks align with key general29 or generic work skills of acquiring information30 or or following directions28, numeracy, conveying information30 and written communication31. Positive feedback on the use of these generic work skills was also reported in terms of their use with scholars and students yet to enter the workplace, where adaptation of general or generic skills are increasingly required for changing job requirements31. The computer tasks which align with the generic work skill for application of information technology31, were used by fewer respondents, probably because the tasks were developed in 2005, Although based on programmes commonly used in computers, aspects of these tasks need to be updated.

Other key generic or general work skills such as organisation and applying logical processes30 or problem solving31 can be assessed using the WASP II. However, the tasks in these subtests were only used by a third of respondents or less, even though positive comments indicated their appropriateness for the South African context and general work ability, especially with mental health care users (MHCUs). Respondents reported using other outcome measures to assess these aspects but did not specify which ones. In the Problem-solving subtest the social awareness task was more frequently used, supporting the importance of this aspect in the workplace, for the generic work skills or working with others or group30 or team work31.

The General cognitive functions, Writing, Visual perceptual, Coordination and dexterity and Dynamic posture subtests, all include tasks which assess work skills related to impairments in memory, visual processing and fine and gross motor ability. Tasks for visual and auditory functional memory and 3D to 3D copying were used by more than 60% of respondents, while the tasks assessing gross and fine motor performance were used by more than 40% of respondents. The use of these tasks is congruent with clients with neurological, mental health and upper limb dysfunction, which respondents reported they assessed most frequently.

Some tasks such as writing samples, cutting a stencil, completing a bank deposit slip and completing a cheque were used by less than 17% of respondents. While these tasks may allow scoring of general work skills such as accuracy and errors, they required extra materials or were outdated, and did not reflect current practice in the work situation, and their retention needs to be reviewed.

The psychosocial battery, a self-report set of questionnaires, was used by 57% of respondents or less. The stress questionnaire was the most useful assessment in understanding work stressors, followed by the self-report of the situation at work. However, it was reported that the questionnaires were long with subjective results that need to be interpreted as such.

While the utility of the WASP II in relation to cost was considered good, the perceived lack of benefits in providing standardised scores was a concern. Even though the WASP II is based on MODAPTS standard times for the tasks with average times indicated for each, and detailed instructions on the task layout required on the mat provided, no information about the coded MODAPTS times was available in the assessment manual. The times can thus not be validated if required. A number of the tasks on the WASP II are not timed and assess ability in relation to errors made. There is no standardisation for the number of errors scored, indicating the need for further research and validation of this aspect of the WASP II.

The WASP II was reported to be useable with acceptable sensitivity to clients' educational levels. It could be incorporated into clinical practice in various settings in South Africa, including private and public sectors and schools. Unlike the useability reported for the AWP assessment, the WASP II provides the required materials in the assessment kit since tasks are standardised and therapists do not need source resources17. Allowing flexibility in the use of one or many of the tasks in the assessment also meant the WASP II supported therapists clinical reasoning on the unique needs of each client, even if the lack of standardised scores especially for ability, did not offer as much support for their clinical judgement. The issue with the WASP II not accommodating the client's home language is an ongoing concern32 when screening and standardised assessments are used in a multilingual country like South Africa33. A similar problem was reported in the utility of the AWP for clients whose home language was not Swedish, the language in which the assessment is administered17. Translation of instructions could be considered, but 83% of respondents agreed that the instructions in the WASP II were not complex and easy for clients to understand.

The utility of the WASP II was adequate for all aspects, except discrimination of mild dysfunction. This may be due to the labelling of the scores 5-1 on the WASP II. The MODAPTS standard time scores relate to the ability of the average worker, although this is indicated as an Above average for a score of 5 on the Likert scale on the WASP II for time and ability. A score of 5 could be reflected as Average to align with an intervention to maintain work ability as indicated on the Work Ability Index34. A score of 4 or Average indicates the client may take twice as long to complete the task. This score should indicate Below average and align with support work ability on the Work Ability Index34. A score of 3 should indicate mild impairment and a score of 2 should reflect moderate impairment which aligns with improving work ability and restoring work ability respectively on the Work Ability Index. A score of 1 is a severe impairment where the clients can take 10 times longer to complete a task and may be unable to achieve any work skill.

A strength of the WASP II is the clinical utility which informs other assessments and intervention and reporting in vocational rehabilitation. The scoring system also means that the implications of the WASPII can be understood by other stakeholders, but clarity and simplification of the results is required for clients and other service providers.

Limitations

The sample of respondents who evaluated the WASP II was small, and results must be viewed in that light. The screening assessment appears to be used by a limited number of therapists in practice, with a considerable variation in the number of therapists using a limited number of the subtests and tasks available in the WASP II battery.

Recommendations

This study has highlighted the need for some subtests and tasks on the WASP II to be revised. A need for additions to the manual indicating the MODAPTS coding for tasks which are timed, and further research to establish validity and reliability of the WASP II ability scores is recommended. The client, employers and other stakeholders' perspective of the implications of the WASP II screening assessments should also be established.

CONCLUSION

Many of the subtests and tasks on the WASP II were viewed as an appropriate assessment for screening general or generic work skills in relation to specific impairments in the South African context. WASP II screening assessment accommodates differing abilities in clients depending on the education level and diagnosis but may under-assess high-functioning clients. Except for clients' home language and providing standard scores for generic work skills, the WASP II was considered to have adequate useability and utility for use in clinical practice with a variety of clients as a screening tool. However, research for updating some subtests and tasks, particularly Organising and sequencing and Money management, is urgently required.

Contribution of Authors

Denise Franzsen and Pat de Witt conceptualised and carried out the research. Tavanesi Gurayah assisted with data collection and position of research historically. Kerry Magill assisted with data management and analysis.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

1. Republic of South Africa. Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Amendment Bill B21-2020. 2020. [accessed 2021 Oct 06] https://www.gov.za/documents/compensation-occupational-injuries-and-diseases-amendment-bill-10-sep-2020-0000# [ Links ]

2. Casteleijn D. Occupational work therapy practice in South Africa. Work. 2007 [accessed 2021 Apr 12];29(1):1-2. [ Links ]

3. Kelly E, Maître B. Identification of skills gaps among persons with disabilities and their employment prospects. Dublin; 2021. Report No.: 107. doi: https://doi.org/10.26504/sustat107 [ Links ]

4. Buys T, van Biljon H. Functional capacity evaluation: An essential component of South African occupational therapy work practice services. Work. 2007;29(1):31-36. [ Links ]

5. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy,. 2020;74(Suppl. 2):7412410010. doi: https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001 [ Links ]

6. Harmse S. Evaluating validity of MODAPTS as an assessment method of work speed in relation to the open labour market. Masters dissertation. University of Pretoria; 2019. [accessed 2023 Oct 10] https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/68456/Harmse_Evaluating_2019.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

7. Laher S, Cockcroft K. Current and future trends in psychological assessment in South Africa: Challenges and opportunities. In: Laher S, Cockcroft K, editors. Psychological assessment in South Africa: Research and applications. New York: NYU Press; 2013. p. 535-552. [ Links ]

8. Discipline of Occupational Therapy, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal. Work Ability Screening Profile (WASP). 2006:2. [accessed 2021 Apr 12] https://www.pdffiller.com/jsfiller-desk11requestHash=95ee70f4152dd11fda8b827a3e834db6439aa713c4d9393824ef77 ec9bb0e0b0&projectId=687898362#641ea834afea5cdfa85523c65a47696e [ Links ]

9. World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability, and health. 2001:303. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J006v27n02 [ Links ]

10. Sullivan B, Carey P, Farrell J. Heyde's MODAPTS: A Language of Work. Jonesboro, AR: Heyde Dynamics Pty, Limited. Heyde Dynamics Pty, Limited; 2001. [ Links ]

11. Glover TA, Albers CA. Considerations for evaluating universal screening assessments. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45(2):117-135.doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.05.005 [ Links ]

12. Bimrose J, Barnes S, Brown A, Hasluck C. Skills diagnostics and screening tools : A literature review. Warwick Institute for Employment Research: Department for Work and Pensions; 2007. [accessed 2022 Sept 22] https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/publications/2007/bimrose_et_al_2006_rrep459.pdf [ Links ]

13. Caballero CL, Walker A. Work readiness in graduate recruitment and selection: A review of current assessment methods. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability. 2010;1(1):13-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.21153jtlge2010vol1no1art546 [ Links ]

14. Nel L, van der Westhuyzen C, Uys K. Introducing a school-to-work transition model for youth with disabilities in South Africa Work 2007;29(1):13-18. [ Links ]

15. Sandqvist JL, Törnquist KB, Henriksson CM. Assessment of work performance (AWP)-development of an instrument. Work. 2006;26(4):379-387. [ Links ]

16. Healy P, Jiang J, Brooke L, Taylor P. Work Ability Index. Promotion of Work Ability towards Productive Aging. 2008;(2):27-32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203882511.ch5 [ Links ]

17. Karlsson EA, Liedberg GM, Sandqvist JL. Initial evaluation of psychometric properties of a structured work task application for the Assessment of Work Performance in a constructed environment. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2018;40(21):2585-2591. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1342279 [ Links ]

18. Smart A. A multi-dimensional model of clinical utility. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2006;18(5):377-382. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzl034 [ Links ]

19. Van Den Berg TIJ, Elders LAM, De Zwart BCH, Burdorf A. The effects of work-related and individual factors the work ability index: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2009;66(4):211-220. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2008.039883 [ Links ]

20. American Educational Research Association (AERA), American Psychological Association (APA), National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington. 2014. https://www.testingstandards.net/open-access-files.html [ Links ]

21. Chaytor N, Schmitter-Edgecombe M. The ecological validity of neuropsychological tests: A review of the literature on everyday cognitive skills. Neuropsychology Review. 2003;13(4):181-197. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:NERV.0000009483.91468.fb [ Links ]

22. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Linnet K, Moons KG. Beyond Diagnostic Accuracy: The Clinical Utility of Diagnostic Tests. Clinical Chemistry. 2012;58(12):1636-1643. doi: https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2012.182576 [ Links ]

23. Bartlett J, Higgins C, Kotrlik JW. Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size for survey research. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal. 2001;19(1):43-50. [ Links ]

24. Khokhar B, Jorgensen-Wagers K, Marion D, Kiser S. Military Acute Concussion Evaluation: A Report on Clinical Usability, Utility, and User's Perceived Confidence. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2021;38(2):210-217. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2020.7176 [ Links ]

25. Polit D, Beck C. The Content Validity Index: Are You Sure You Know What's Being Reported? Critique and Recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006;29:489-497. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20147 [ Links ]

26. Addington-Hall JM. Survey research: methods of data collection, questionnaire design and piloting. In: Addington-Hall JM, Bruera E, Higginson IJ and, Payne S, editors. Research Methods in Palliative Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 61-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198530251.003.0005 [ Links ]

27. Vanderbilt University. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). 2019. [accessed 2021 March 23] https://projectredcap.org/software/ [ Links ]

28. Sitlington PL. Students with reading and writing challenges: Using informal assessment to assist in planning for the transition to adult life. Reading and Writing Quarterly. 2008;24(1):77-100. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560701753153 [ Links ]

29. Cappelli P, Rogovsky N. Skill Demands, Changing Work Organization, and Performance. EQW Working Papers WP32. Philadelphia; 1995. [accessed 2022 Jan 16] https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED394001 [ Links ]

30. McCurry D. Notions of Work-related Skill and General Abilities: The Generic Skills Debate and the The Whole-school Assessment of Generic Skills Doctoral thesis, Monash University; 2004. [accessed 2021 Oct 12] https://bridges.monash.edu/articles/thesis/Notions_of_Work-related_Skill_and_General_Abilities_The_Generic_Skills_Debate_and_the_The_Whole-school_Assessment_of_Generic_Skills/5188573/1 [ Links ]

31. Pumphrey J, Slater J. An assessment of generic skills needs. London; 2002. [accessed 2021 Nov 19] http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/4698/1/SD13_Generic.pdf [ Links ]

32. Shafiee E, MacDermid J, Farzad M, Karbalaei M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of Patient-Rated Wrist (and Hand) Evaluation (PRWE/PRWHE) measurement properties, translation, and/ or cross-cultural adaptation. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2021: online 1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1970250 [ Links ]

33. Bornman J, Romski M, Tonsing K, Sevcik R, White R, Barton-Hulsey A, Morwane R. Adapting and translating the mullen scales of early learning for the South African context. South African Journal of Communication Disorders. 2018;65(1):1-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/sajcd.v65i1.571 [ Links ]

34. Ilmarinen J. The Work Ability Index (WAI). Occupational Medicine. 2006;57(2):160-160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm008 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Denise Franzsen

Email:denise.franzsen@wits.ac.za

Submitted: 28 April 2023

Reviewed: 11 October 2023

Revised: 27 October 2023

Accepted: 29 October 2023

Editor: Hester M. van Biljon: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4433-6457

Data availability: Data available on request from the corresponding author

Funding: No funding was received for the research.