Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.53 no.3 Pretoria dic. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2023/vol53n3a8

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Entrepreneurial knowledge and skills transmitted from parents to their children: An occupational legacy strategy for family-owned businesses

Thuli G. MthembuI; Nadie ChristiansenStephanie KrielIII, VII; Chanté MaroneIV, VII; Joané MasonV, VII; Sihle ZwaneVI, VII

IOccupational therapy, University of the Western Cape, South Africa; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1140-7725

IIOccupational Therapist, Care@Midstream Subacute, Pretoria, South Africa; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0654-5146

IIIOccupational Therapist, Akeso Milnerton Psychiatric Clinic, Cape Town, South Africa; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8641-3935

IVOccupational Therapist, Neta Care, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7398-6577

VOccupational Therapist, Private Practice, Springbok, Northern Cape, South Africa; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7398-6577

VIOccupational Therapist, Mpumalanga Department of Health, Matikwana Hospital, Mkhuhlu, South Africa; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6828-3911

VIIUndergraduate students at University of the Western Cape, South Africa at the time of the study

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Transmission of entrepreneurial legacies in family-owned businesses has received increased attention. There is still uncertainty, however, whether families pass down the knowledge and skills onto their children.

AIM: This study explored how families transmit entrepreneurial knowledge and skills as part of occupational legacy to their children

METHODS: This narrative qualitative research was conducted with five families who owned business in the Western Cape and Mpumalanga Provinces. Twelve participants were selected through purposive sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with the participants using a face-face approach and telephone calls were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim then thematically analysed in a credible manner.

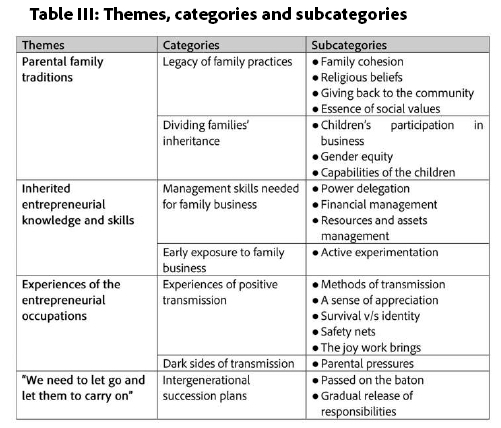

FINDINGS: Four themes captured the qualitative evidence of how the families transmit entrepreneurial knowledge and skills to the children consists of Theme 1: Parental family traditions; Theme 2: Inherited entrepreneurial knowledge and skills; Theme 3: Experiences of the entrepreneurial occupations; and Theme 4: We need to let go and let them carry on.

CONCLUSION: Overall, this study indicates that through enacted togetherness, transitions and adaptations allowed families to engage in entrepreneurial occupations that facilitated inculcation of knowledge and skills needed for family-owned businesses. The social implication of this study is that families transmitted the legacy of social security of their communities.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE:

This study suggests that occupational therapists should consider the needs of older generations who are prone to imposter syndrome due to handing over their family-owned businesses to the younger generations. Greater efforts are needed to ensure that older and younger generations have mental and emotional capacity to deal with the psychological and environmental factors that can influence transmission of entrepreneurial legacies. Therefore, occupational therapists may design intervention strategies to facilitate transition, resilience, productivity and wellness.

Keywords: economic occupations, transgenerational transmission, intergenerational success, social security, entrepreneurial occupations, family tradition

INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Transmission of entrepreneurial legacies in family-owned businesses (FOBs) has received increased attention across a number of disciplines including occupational therapy profession. Entrepreneurship is a "process of transformation of opportunities using existing resources and it involves identifying an opportunity, making a product, growing the venture, taking risks and producing rewards for the entrepreneur and stakeholders"1:2. It is one of the relevant and critical work that fosters economic occupations that contributes to meaning, identity, income, wages, economic growth, interaction and development in FOBs2.

FOBs accounted for approximately 70% of the gross domestic product (GDP) globally, which originates from the entrepreneurial occupations and they create two-thirds of employment opportunities3. Transition and continuity of the FOBs from the past to present and future transmission of legacies are needed4-7. Members of the same family from different generations govern and engage in the entrepreneurial occupations that are passed down onto the children and grandchildren, as part of occupational legacy strategy4,5. Thus, occupational legacy must be approached with some caution because passing the same occupations to younger generations could illuminate the dark sides of occupation, such as "poverty trap, low wage and precarious work generating a vicious cycle of poverty"4:169,8.

In a post-apartheid South African context, unemployment is a grave form of economic injustice estimated to be 34,5%, while among youth is 63,9% for those aged 15 - 24 and for those aged 25 - 34 years is 42,1%, which appears as a problematic situation that perpetuates social and economic inequalities in families experiencing financial and food insecurity9,10. Less than half (42%) of African FOBs indicated that they need to create employment opportunities for other family members to ameliorate the unemployment rate11. In FOBs, entrepreneurial legacies are passed on from one generation to other generations to eradicate poverty, create wealth for the economies of the societies and encourage growth and employment opportunities6,12-14. In contrast to the perceived benefits, barriers such as limited "access to capital and managerial talent", lack of skills, training, intergenerational succession, and experiences influence the transmission of entrepreneurial legacies15:155,16. Senior generations tend to have problems in passing over their family businesses to the next generations because they need to protect their status, meaning, power and other rewards as well as emotional attachments17. Yet, there is a paucity of research on how senior generations pass on legacies related to entrepreneurial knowledge and skills needed by the next generations to manage the family businesses.

Economic occupations

A significant paradigm shift has been noted in occupational therapy profession towards community-based and emerging practice opportunities that incorporate economic occupations in social entrepreneurships18,19. Street vending and self-employment of people with disabilities are economic occupations that contribute to wellbeing, economic freedom and security19-22. This paradigm shift reinforces goal 8 (Decent work and economic growth) of the Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goal, which targets growth of small- and medium sized enterprises, supporting productive and entrepreneurial activities23. Family legacy is perceived as an enabler that facilitated women to engage in the economic occupation of street trading, which assisted in generating income for their families20. Despite the importance of street trading as an economic occupation, there remains a gap of evidence on how parents transmit entrepreneurial legacies of street vending to their children as part of occupational legacy12,24,25. Our study takes its departure from the research indicating that family legacy passed on by the parents to their children fosters survival skills4,20. It is envisaged that the study will contribute to community-based and emerging practice opportunities then occupational therapists may consider occupational legacy as a strategy that facilitates intergenerational entrepreneurial occupations and family transition process.

Transgenerational transmission

The transgenerational theoretical framework underpins how families transmit entrepreneurial knowledge and skills to the younger generations. Transgenerational theory focuses on the transmission of rules that facilitate communication of acquired practices, behaviours and beliefs between generations26. It emphasises that parents with entrepreneurial roles influence their children's "choice of occupation, educational aspirations, attitudes towards money and politics"26:350. In the family environment, transgenerational legacy comprises both positive and negative aspects27. Consequently, FOBs should consider the feelings of solidarity, commitment and co-responsibility to enable participation in the transmission of entrepreneurial legacies and loyalty among the generations27. Three significant modes of transmission: knowledge passed from the older generations to the younger ones27; knowledge passed on from the younger generations to the older ones27; knowledge transmission involves peaceful or conflicting coexistence, which deals with dialogues about boundaries between the past and present to prepare for future success27.

Intergenerational success

Intergenerational succession plan is an "explicit process by which management control is transferred from one family member to another"28:233. In FOBs, senior generations relinquish ownership and control roles to become consultants and retirees, while the younger generations take the successors role to reduce the business challenges, risk of liquidation and negative consequences for the family relations12,17,24. The challenges of FOBs' continuity include emotional regulation, power struggles, sibling rivalry, family values, family conflicts, autocratic paternalistic cultures, nepotism, rigidity in innovation, succession and resistance to change13:10.Buckman et al.'s29 six-stage holistic succession model entails the founder's readiness and willingness to pass on the baton to the successor to take over the control of the FOB. In stage 1 of knowledge codification, the founders ensure that their entrepreneurial orientation is guided by the lessons learnt, which are used in the transmission of legacies. It has been highlighted that the transmission of entrepreneurial legacies in FOBs could be in the form of genetic, material, historic, symbolic heirlooms and values30. The successors are not involved in the management responsibilities; however, they are provided with occupational opportunities during school holidays and weekends.

In the second stage of successor selection, the founders identify the gaps in skills and provide the successor of the FOB with holiday work to foster the capabilities needed for managerial and technical competency, cultural knowledge and skills to their offspring31. The third stage of strategic training involves mentoring, coaching and experiential learning outside FOB.

However, the successor could be guided to explore formal education and informal training in the field of entrepreneurship, which strengthens entrepreneurial self-efficacy. The fourth stage succession bridging deals with the communication and readiness of the founders to transfer powers and share written plans with the successors to take responsibilities in a shared leadership. In passing down FOBs, families engage in a complex transition process, which results in potentially hard decisions and opportunities to explore family and legacy goals5. The fifth stage of strategic transition, the founders become consultants to guide the successors to take full responsibilities to manage and make decisions in the FOBs27,32. In the last stage of post succession performance, the founders are not involved but the successors engage in entrepreneurial activities, conflict management with the founders, family members, customers, employees and advisory board for successors' transition process33.

Occupational science perspective

The Theory of Transition undergirds the understanding of the transmission of entrepreneurial legacies. This theory was developed in a rigorous process described in Crider et al.'s7 integrative review, which resulted in seven strands describing how healthy populations experience transition: 1) qualities of transition, 2) the experience of transition, 3) roles and transition, 4) environment and transition, 5) occupation and transition, 6) factors that facilitate transition and 7) factors that make transitions difficult7:307. These strands are adopted to enhance our insight into parents' and children's transition through their engagement in the occupation of transmitting legacies related to entrepreneurial knowledge and skills. In using the Theory of Transition, the strands provide evidence of how the parents' and children's self-esteem and motivation improve their participation in entrepreneurial activities. In the area of work, the strands support economic occupations related to traditional and cultural activities that enhance the livelihood of the masses; which is still lacking in occupational therapy19.

Regarding goal 11 (Sustainable cities and communities), the Agenda 2030 of Sustainable Development Goals highlights that there is a need for strengthening efforts to protect and safeguard the world's cultural and natural heritage23. Passing entrepreneurial knowledge and skills related to the economic occupations such as weaving, sewing income generation projects, farming/agriculture as well as cleaning and gardening business enhance families' well-being, cultural identity, empowerment, social support, and economic survival4,19,34,35.

The exposure of the younger generations to these economic occupations reinforces competency and a sense of continuity so that they are able to appreciate the skills that their parents passed on to them35,36. Through being part of the FOBs, the children and other family members are provided with opportunities for occupational transition, which supports "sharing expertise, ideas and interests and learning from each other"35:70. Thus, transmission of legacies related to entrepreneurial knowledge and skills within families influence on occupational identity, individual's roles, values and personal goals as well as concepts of choice, productivity and social dimensions37,38.

However, there is a rarity of discussions about the transmission of entrepreneurial legacies and economic occupations for income generation, as part of the area of work. Therefore, an understanding of and insight into how the families pass on entrepreneurial knowledge and skills in a family-owned business might provide occupational scientists with opportunities to contribute to economic occupations. Thus, the study aimed to explore how families transmit entrepreneurial knowledge and skills as part of occupational legacy to their children.

METHODS

Study design

A narrative qualitative research design was employed to gain an insight into the social and occupational phenomenon of transmitting legacies of entrepreneurial knowledge and skills. The narrative qualitative research has been used to bridge the gap between positivism and social constructivism paradigms to learn about the culture, historical experiences, identity, human experiences, and lifestyle of the participants39,40. In the narrative study, the interactions about the past, present and future of the FOBs provided a rich and in-depth information and meanings attached to the phenomenon39.

Family-owned Businesses Profile

FOBs in the Western Cape Province: The Venter family focuses on vegetable and fruits farming, while their daughter is a Protea-farmer on the farm passed on by the father. The Koopman family focuses on electrical services with both parents and successors involved in the sector. In the Marais family, the father started retail services; currently, the only son is in charge of everything. In Mpumalanga Province: The Meyer family deals with farming ranging from forestry, maize, cattle, game, chicken, dairy and even cabbage as well as Bed and Breakfast. The families and their descendants who appeared to be eligible for continuity of the business are willing to learn the entrepreneurial knowledge and skills from the enterprise. The Sibiya family deals with construction, room rental and small tuckshop, while the son owns a catering company.

Population and sampling

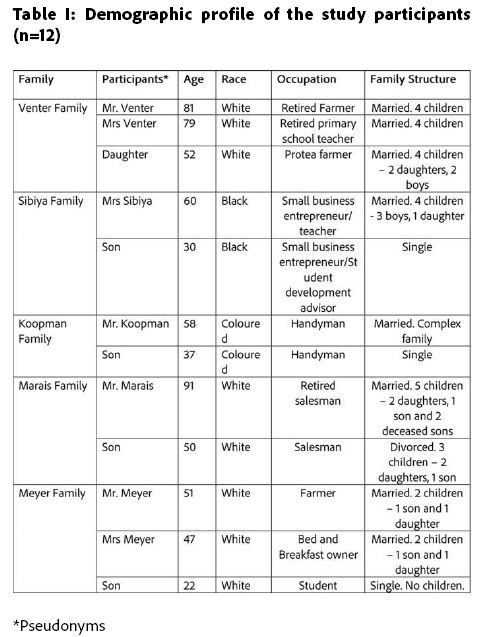

The population of this study include families who own businesses in the Western Cape and Mpumalanga Provinces. Purposive sampling method with maximum variation was used to select participants who met the inclusion criteria: being family members from the FOBs identified as parents and adult child; diversity in business profile; different races (black, white and people of colour); all genders and ages; and able to converse in English, Afrikaans, siSwati and German. Five families were approached and recruited through different routes, such as emails, telephone and personal communication. A total of 12 participants consists of eight males and four females between 22 - 91 years of age with a mean and standard deviation of 54.83±20,74. Table I (below) presents the participants demographic information.

Data collection and analysis

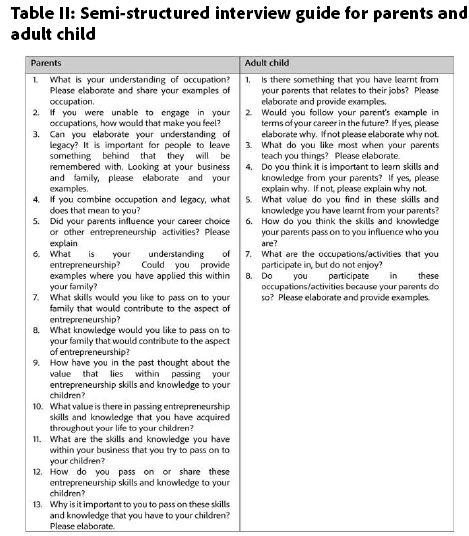

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between July and September 2019, through a face-to-face approach and telephone calls for a duration of 25-90 minutes, with the participants without interference of non-participants. Participants were asked to provide their demographic information. An interview guide (see Table II, adjacent) was developed and the questions were formed based on the reviewed literature focusing on family-owned businesses, entrepreneurship, legacies and succession plans. The semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim in preparation for analysis. Data redundancy was reached when there was no new information forthcoming from the twelve participants.

A six-step narrative thematic analysis process was used41. The transcripts were read several times for familiarisation with the data in preparation for generating initial codes. As a result, the authors generated codes in a consistent manner. This led to the third step whereby the similar codes were merged into categories, which was guided by the discussions between authors after they reached consensus. The themes were not identified in advance from the data; the authors searched, defined and named the themes through the process of continuous discussions to reach consensus. Subsequently, the authors employed consolidated criteria for reporting and writing up the qualitative research (COREQ)42.

Trustworthiness

Credibility was enhanced by using peer reviews with knowledgeable researchers in qualitative research, and the authors presented and discussed the findings until consensus was reached. A triangulation of investigators enhanced the credibility of the study by employing an interview guide for consistency with the participants. Participants validated the findings, as part of member checking. Transferability was enhanced by providing a thick description of the research settings, methods, participants and analysis. Dependability was enhanced through an audit trail to keep track of the study.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was sought from the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of the Western Cape and ethical clearance HS19/6/56 was granted. All the participants consented to be part of the study after the authors provided information about the purpose of the study. Participants had an opportunity to withdraw from the study without any repercussions. Pseudonyms were used as a strategy of anonymity to protect personal information and confidentiality of the participants.

FINDINGS

Four themes with categories and subcategories were identified during the iterative process of data analysis (Table III, page 69).

Theme One: Parental family traditions

The first theme deals with the parental family traditions that emerged from the families with businesses, which comprised several legacies related to family practices and dividing families' inheritance. Firstly, the legacy of family cohesion was shared among three different families who own businesses, which supported family functioning and entrepreneurial spirit.

"It is very important that the children should love their mother and father; and love the kind of business where the mother and father work". (Mr. Marais)

"We are trying as a family to help each other, let us be united, all of us; we all need each other in good and bad times". (Son of Sibiya's family)

Secondly, the participants in their parental voice shared that they have passed down the legacy of spiritual-religious beliefs, diversity, and autonomy on the children to sustain their lives and businesses.

"They [Children] know God, he knows everything and in God we ask everything that we need and we are surviving because of God". (Mrs Sibiya)

"I want my kids to ask more questions and they should not judge anyone, not even Muslim". (Son of Marais' family)

Thirdly, parents passed down onto their children the legacy of giving back to the community to contribute to environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG).

"We wish that the entire community could improve and not just ourselves". (Mrs Sibiya)

"This family business does something for other people (community members) more than other businesses do for the people in need". (Mr. Marias)

"People in the informal settlements have depression because they do not have a choice and they worry about hunger. In this town, there is no organisation where you go to, where our business has not given something... it is just gift-vouchers but it is constant" (Son of Marais' family)

Fourthly, parents passed down the legacy of social values, such as respect for human dignity, punctuality, commitment, work ethic and task oriented onto their children, which supported the family practices and enabled solidarity amongst families.

"...respecting everyone around you, as you would like to be respected is what we tried to teach them". (Mr Meyer)

"My children learned to work and to respect the people who work in the farm, the labourers also accepted the children". (Mrs Venter)

"My dad always got up early; he believed if it is light outside then you should start working. He also went to bed early in the evenings, so he was always punctual and yes, very diligent with his work. He set a good example of commitment with his work and he is very task oriented". (Daughter of Venter's family)

Regarding the families' inheritance, parents used their discretion to divide the inheritance amongst the children based on the active participation in the operations of the business and gender equity was significant not to favour only the sons but also the daughters.

"On the farm, we have now made a difference because my son is now in management, not because it is discrimination, but he gets 60% of the farm and my daughter 40%". (Mr. Venter)

"My daughter has the same right that he (my son) does. It is all the things that we need to think about and look at how we can accommodate them". (Mr. Meyer)

"Depends on my dad and them, if they draw up their testament... the farm where we live now, the farm apparently goes to mysister and she inherits the farm. The thing is we have to be satisfied with what we inherit and live with it". (Son of Meyer's family)

Parents shared that inheritances will be divided and passed down onto the children based on their capabilities so that they will be able to use the resources.

"I will look at them (children) and divide them based on their weaknesses and strengths. The one who has the lowest intelligence will get the rental rooms. I will also divide the cars. Whoever gets a car, would have got a car, whoever gets a tractor, would have got something". (Mrs Sibiya)

Theme Two: Inherited the entrepreneurial knowledge and skills

The second theme deals with the participants' perceptions of entrepreneurial knowledge and skills passed down onto the children, which included management skills needed for the family business and early exposure to business. Regarding the management skills needed, parents adopted a shared leadership style that facilitated power delegation to their children so that they could learn how to manage the FOBs, as a transition strategy for the successors of the corporate.

"If they (community members) come to me and ask. I say they have to ask my son. I sent them to him (son)". (Mr. Koopman)

"They know that is why they (community members) always come to ask me. They no longer come to fetch my father; he is getting old now". (Son of Koopman's family)

For instance, parents delegated their children with social work qualifications to focus on the employees' health, quality of life and wellness.

"I did social work. When we came to the farm, my dad said I should also take care of... the workers with troubles". (Daughter of Venter's family)

Parents passed down the legacy of financial management skills onto the children at an earlier age so that they could learn the daily functions and operations, such as quotations, deposits, savings, and a general sense of how to manage money in the FOBs.

"They (parents) have managed their finances when they started getting money; I would say it really helped me in terms of understanding money.So that I will be able to manage my own money. They gave us all the opportunities to be involved in the family business. In terms of knowing exactly how much, how to check in the money and how they (the workers) have worked...When my parents are not at home, we are able to prepare the salaries for the employees". (Son of Sibiya's family)

"I helped him (son) by explaining what to do when doing business. Another person did not want to pay him. I always try to tell him that he must take a deposit. He must insist on a deposit. So that if they (clients) are scammed, then he knows, you have a portion". (Mr. Koopman)

The legacy of being a handyman was passed on from the parents to their children and grandchildren, which promoted intergenerational transmission and succession. In the Koopman's family, the son indicated available tools were heirlooms that sustained their business. The tools were used and grandchildren learned how to use and manage them.

"I use his (Father) tools. I still have some of his old stuff. I do not have any new ones (tools). I have always used the old ones. I also teach my children with those tools such as screwdrivers and drills. A big reason why the work is done is because the tools are already here. Any tools out there I use from him. These are the stuff that I got, I mean, it was there". (Son of Koopman's family)

An early exposure provided occupational opportunities for the parents to pass down technical skills needed for technical occupations, such as welding, pipefitting, oven making, and cold rooms onto the children for active experimentation, which steered them to the entrepreneurial directions.

"Yes, just exposure to the business from a young age". (Son of Sibiya's family)

"I watched my dad work when I was a child... I sometimes handed him the tools most of the time and I just kept an eye on it... what he does with each tool, if he told me; do this and that, then I did. Later, I started to work with my hands. I learned everything, now I am a Jack-Of-All-Trades. Now I teach my own child what and how to do it. I taught him (son) how to weld the pipes and I learned that from my dad. I first taught him how to put the pipes together. We do the oven, then I teach him all those things. Firstly, I would do it, and then he does it. Actually, we do everything together. He also learns from his grandfather. Not just by exposure. He sat down with me and explained to me, that is how he did this and that. He did it to his fullest potential". (Son f Koopman's family)

Son of the Meyer's family reported:

"He always offered me the opportunity to go along with him (Father), and to participate in everything that he was doing. He gave me the opportunity to do things on the farm by myself, which is how I discovered my love for the farm, and I have wanted to do it since I was a small child. With farming, just everything that is on the farm, I learnt from my dad. From planting trees, to cattle, to maize, from the beginning to the end". (Son of Meyer family)

Mrs Meyer echoed her son:

"Our legacy is that we can give them something. Otherwise you could say, here I will give you the money, go and buy yourself a farm if you want to. Now he gets something that has already been built, something he carries on, and he can build on". (Mrs Meyer)

Participants indicated that their family businesses provided occupational opportunities for community capacity building with technical skills.

"I help and teach other people (workers), not just my children. I show people how to work with electricity, saws, or grinding. I teach them. It is good work for them too... it is something for their future as they move forward. (Son of Koopman family)

Theme Three: Experiences of the entrepreneurial occupations

The third theme captures the participants' experiences of entrepreneurial occupations within FOBs, which illuminated positive and dark sides. Participants shared importance of family relationships, which added value on the positive experiences of engaging in entrepreneurial occupations.

"I feel that I have plenty of stuff, buildings, new store and shares. Now, it is about relationships with my children. I am going and I hope we will be able to remain good friends for a long time. It is not important to me for them to come to the business... I think I have a much more open perspective; I make my children think. I talk to them about the books". (Son of Marais' family)

Innovation is one of the skills that was evident amongst the participants who transferred the knowledge of growing different types of flowers to their children.

"I try to give them (children) the knowledge I have about the flowers, I tell my children it is this and this type of protea". (Daughter of Venter's family)

Participants shared deep feelings of gratitude and great admiration about the sacrifices and efforts that their parents made for their successes. They further indicated that they drew their inspiration from their parents who inculcated entrepreneurial knowledge, which contributed to the continuity of the legacies.

"You also need to appreciate what they have already done for you and where they come from in business, and everything they have gone through to get the farm to where it is now. The things that they have taught me, are more valuable, and are more meaningful to me... I just realised how much I have actually already learnt about farming from my dad, with the things he has always told me and all those things; yes, it is more valuable than my university education". (Son of Meyer's family)

"I learnt many things from him (Father). Not just about electricity but tiles, plumbing work, so I learned all of this from him. I had to ask my dad again, how to connect it. Then he shows me again... the red one goes here or the pink wire goes there... he taught me". (Son of Koopman's family)

Parents occupationally adapted when they had no business opportunities and they ventured in other areas to expand their services and markets, as part of diversification and safety nets. Through engaging in the alternative occupations, they were able to fulfil their well-being needs.

"The problem with the work that I do, the money is not always there. So, I have to do a lot of different things. Look, when I cannot do electricity work, I just do whatever work is available. As for example; the ceilings. I will say jack-of-all-trades. This is what I really do when there is no work". (Mr Koopman)

"There is no work these days. I was largely boosted by the finances that I accumulated from tractors and selling clothes. I was able to pay for my children's tuition with that money. I raised my children with that money that I received from selling old clothes". (Mrs Sibiya)

Based on the South African economic status, participants shared that they had to use their talents as safety nets to explore other business opportunities for financial security.

"In this South Africa economic status, a person does not really need to rely on their salary as a source of income, but should use their talents to make money. Currently, I am in the accommodation sector as well as catering". (Son of Sibiya's family)

Engaging in entrepreneurship activities rejuvenated the entrepreneurial spirit amongst the parents and children, which resulted in a sense of joy. Participants enunciated that as entrepreneurs they have an internal drive that pushes them to succeed in their FOBs.

"It is very fun for me; I am involved all the time, but I can do something else if I like too". (Daughter of Venter's family)

"I'm enjoying the space where I'm in, the activities and the duties that I am doing currently. I'm doing something that I'm really passionate about.... it's something that I have the skills for, and it's not really influenced by what my parents are doing". (Son of Sibiya's family)

Two of the participants (Mr Koopman and Mr Meyer) echoed the daughter of the Venter and son of the Sibiya-families regarding the importance of enjoyment in all the activities that they engaged in, as part of the family business and other jobs.

"I say one thing when you go into any business - you have to enjoy it". (Mr Koopman)

"You need to have your head right, regardless what job you may have, that you are happy and that you do it to the best of your ability". (Mr Meyer)

Participants shared that bricklaying is one of the entrepreneurial occupations that illuminated the dark sides of precarious activities and parental pressures.

"My dad was a bricklayer. He wanted us to do it but no one ever did. It was too dangerous. He told us all one day; one of us has to become a mason because it does not help that the materials and tools are here and be wasted. One day he told us that there has to be someone who follows his example". (Mr. Koopman)

"When he (Son) was leaving university, I said, listen, if you do not get the right job now, then you work with us (family business)". (Mr. Marais)

From the Sibiya- and Venter- families, it was evident that parental pressures did not restrict the children's business decisions about introducing contemporary ideas in the FOBs. Parents' flexibility and openness instilled in their children a sense of agency and autonomy to engage in diverse activities.

"We were given the liberty to make decisions, when it comes to expanding and growing the family business. they (parents) gave us that liberty they said 'you guys can also be able to do the things that we do if we are not around'... My parents also instilled from a tender age, that value of choosing what you would want to be and directing your life as an individual". (Son of Sibiya's family)

"There was no pressure, nobody ever expected us to go to the farm. I was able to study anything I wanted to". (Daughter of Venter's family)

Theme Four: "We need to let go and let them carry on"

The last theme deals with the parents' perceptions of willingness to relinquish their roles and hand over the family business to their children to become successors for continuity. The title of this theme emerged from the story of Mr. Meyer who expressed "The biggest legacy that is ahead of us now, is that we need to let go and let them carry on". This theme also highlights parents' readiness to pass down the baton of leadership, management, and decision-making responsibilities of their FOBs onto their children.

"They (children) still invite me so that I will always know what is happening with the finances, but I do not involve myself anymore". (Mr Venter)

"My eldest son is unemployed, he is here at home, and I told him that I am leaving him to be a manager of the tractors". (Mrs Sibiya)

Parents had opportunities to provide advice as consultants to guide their children when they needed assistance with operations of the business. They shared leadership to facilitate taking new roles, and resiliency in the FOBs.

"If I am stuck, I come and get him to come help me with something. I tell him, we need to do this now; I get it from him". (Son of Koopman's family).

"They (children) took over and I, the father, stepped back completely. We then told my wife she could retire. I stepped back so I helped where I thought was needed". (Mr. Marais)

Parents gradually released the business responsibilities to their children and they created opportunities for active experimentation to apply entrepreneurial knowledge and skills transferred to them into practice. This enabled the children to learn from their mistakes and master the newly acquired skills and knowledge of how to operate in a family business. The parents employed strategies such as observation of how the work is done, practically do the work with them and gradually decrease the assistance required.

"I would leave him to continue; then I would leave him alone. Then I come home or I go to another client. Then I let him continue. Then I go to him and I say, 'Don't close it, I need to see first. When I come back and I look at it then I might say, that one is wrong, or that one is right, do something like that....' Then I let him go again". (Mr. Koopman)

"All the time you keep the kids updated. You cannot just leave someone... You must have pointed out all the mistakes you see happening now... You talk to them; and I think it helps a lot if you give people feedback... Every month, I see the state of the business, how it progresses, and the turnover". (Mr Marais)

Imposter syndrome is the condition that involves feeling anxious, self-doubt, and negative self-views among people with high performance who tend to experience uncertainty about their abilities43. Therefore, imposter syndrome was inevitable amongst the participants who released their responsibilities of the FOBs to the children. Nevertheless, the participants used adaptive strategies, such as continuous knowledge sharing, a sense of calmness and communicating their concerns.

"There are times that I feel as if I am not good enough anymore. I cannot scold him that much anymore... I do not get angry, I just explain to him then he tells me, 'no, you have to stop shouting! Then I tell him, 'No it's not the point. You have to learn harder; when you reach a certain point then you have to listen". (Mr Koopman)

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The current research aimed to contribute towards the qualitative evidence base on the transmission of legacies related to entrepreneurial knowledge and skills situated in family-owned businesses in a post-apartheid South African context. The four themes are discussed based on enacted togetherness44, strands of the Theory of Transition7, and occupational adaptation45.

Enacted togetherness in family-owned businesses

The findings of the current study indicate that engagement in delegated entrepreneurial occupations provided the parents and children with opportunities for meaning-making through their connectedness and interdependence, which is consistent with enacted togetherness, sense of belongingness and well-being27,44,46,47. It was evident that the socio-cultural context of the FOBs enabled the parents to engage in the altruistic occupations of passing down entrepreneurial legacies onto their children and community members, which supported connecting and contributing to others46-49. These occupations improved the well-being and lives of the families, employees and communities through giving back nutrition, entrepreneurial knowledge and skills to sustain the society contributing to environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG)50.

The findings in our study show that the parents did not only preserve the FOBs' legacies of values related to respect for every human, equality, relationships and social capital but also the standard of living, faith, religious beliefs and economic growth27,51. The parents as role models passed down legacies of capabilities of 'Know-how', such as entrepreneurial and technical skills onto their children, which strengthened their problem-solving and occupational potential52,53. These findings show that the children developed capacities "to do what is required and what they have the opportunity to do, to become whom they have potential to be" as future entrepreneurs were transformed53:137. The findings of the present study are consistent with other studies that valued parents' validation as an enabler for development of children's occupational identities54. Through enacted togetherness, the children engaged in a transition process of "inheriting from parents; being directed by parents; and being mentored by elders"54". Knowledge gained about transmitted entrepreneurial legacies can assist occupational therapists to invest in collective and collaborative occupations that enacted togetherness and belonging, to honour the past and present while preparing for the future. Occupational therapists should consider collaborative participation in intergenerational occupations, such as farming, woodwork, pipe fitting, gardening, mentoring and others to foster occupational identities, meaning and purpose, hope among the parents, grandparents, children and grandchildren36,48. Thus, occupational therapists should be guided by a we-consciousness when they put a premium on serving the community, lifting others, and finding joy in empowering others55.

In sustaining the FOBs' operations and functions, the parents passed down shared leadership and responsibilities onto their children so that they can take control over the entrepreneurial activities, as part of autonomous-supportive parenting. Our study indicates that the children also inherited inalienable heirlooms such as tools, land for farming, and tractors as part of objects that enabled their engagement in entrepreneurial occupations, which corroborates with previous studies50,51,56. The heirlooms were imbued with domestic history and achievement, which affirmed the family identities and continuity56. The findings of the present study indicate that the parents trusted their children to be the guardians of the heirlooms for future generations to transition.

Transitions through engagement entrepreneurial occupations

Understanding the link between roles as part of occupational patterns and occupations enhances occupational therapists' knowledge about factors that facilitate and constrain transition during engagement in entrepreneurial occupations7. The fourth theme (We need to letgo and letthem carry on) indicated parents' readiness to engage in the transition process as they accepted the reality that their children should continue with the FOBs. Availability of both social support and resources enabled on-the-job training that facilitated skills building so that the parents are convinced the children had successful transition7,36. The findings in the second theme (Inherited the entrepreneurial knowledge and skills) corroborate with Crider et al.7 who concur that knowledge facilitates effective transitions to new roles, like in our study the parents became retired owners and consultants while their children adopted being successors.A possible explanation for the successful transition is that the parents and children had clear expectations about the tasks and goals of transmitting the leadership and responsibilities of the FOBs. Another possible explanation for smooth transition is that the parents and children invested in intergenerational relationships, which facilitated their adjustment and role development through earlier exposure in entrepreneurial occupations.

Transition may disrupt participation in occupations7; however, the findings of the present study indicate that parents at some points were frustrated by how their children responded to constructive feedback. The findings further revealed that there was a major change in selecting and organising entrepreneurial activities, leadership and responsibilities of the FOBs, which enabled occupational adaptation and resilience. Through children's performance evaluation, parents were convinced that the future of the FOBs was bright because they were all committed to strive for stabilisation, which enabled their transition and adaptation57. It could be argued that the positive results were due to the fact that the parents were confident that their entrepreneurial legacy lives on because they shared leadership with the children who inherited the FOBs58. Passing down FOBs onto the children can be disruptive and difficult for the older generations. It can therefore be suggested that occupational therapists should engage in collective efforts to overcome injustices that may influence the transmission of entrepreneurial legacies and facilitate occupational adaptation.

Occupational adaptation in family-owned businesses

Imposter syndrome is inevitable amongst new entrepreneurs; which necessitates occupational adaptation and transitions in the operations of the FOBs. Nonetheless, our study found that the children experienced a sense of adaptiveness because they went through the transition process of rejuvenation and they embraced their legacy of entrepreneurship59. Older generations not only needed to urgently adapt and accept but also allow their offspring to turn over a new leaf to facilitate rebirth transition, which promotes new ideas and goals of entrepreneurial projects59. The results of this study show that interactions between the participants and the socio-economic context facilitated their adaptation. In congruent with Jaskiewicz et al.'s59 explanation of exaptation transition, it is a process whereby children repurpose existing ventures by pursuing new entrepreneurial activities based on the new market demands, which might be linked or different from the original business. This is evident among the parents and their children who used strategic agility to explore new entrepreneurial opportunities to ameliorate disappointing occupational challenges by adopting diversification59. The third theme (Experiences of the entrepreneurial occupation) highlighted that economic occupations, such as selling clothes, accommodation, catering, and ceiling fitting were safety nets of the businesses.

Participation in these economic occupations instilled hope amongst the participants so that they fulfil their wellbeing needs of occupational resilience and survival, which assisted in the future projections and flow of the FOBs20. Accordingly, our findings reverberate entrepreneurial intention, as the participants' conscious state of mind encouraged their aspirations to establish a new enterprise while building on an existing one60.

The children occupationally adapted as they had opportunities to engage in new entrepreneurial occupations together with their parents58. Through the process of exaptation transition, the parents adopted a hand off approach as a coping and adaptive strategy, which assisted in stepping back and retiring from the FOBs7,58,59. In accordance with the present results, previous studies have demonstrated that through the process of occupational adaptation people develop a sense of competence, self-efficacy and identity in occupational participation35,60,61. In making the world a better place for everyone, occupational therapists should collaborate with FOBs in communities to design and develop intergenerational entrepreneurship programmes. This may enable collective efforts to promote healthy cities and communities where younger generations engage in entrepreneurial occupations to address social determinants of their everyday lives such poverty, hunger, unemployment and food insecurity23,36,47. The present study raises the possibility that there are perceived benefits of engaging in transmission of entrepreneurial legacy projects include occupational adaptation, skills development, transition, resilience and safeguard heritage. Digitalisation is an adaptive strategy that FOBs used to network and market their products in social media; nevertheless, our study failed to highlight how parents passed onto the children the digital skills like other entrepreneurs11,50.

Limitations

Purposive sampling was used with maximum variation with inclusion criteria of adult children from the FOBs; however, only one female child participated. This might mean that future research should consider recruitment of female children to explore their experiences of legacies of "operational and emotional family support, as control, decision making and management" in FOBs14:431. A lack of female children's narratives in the sample adds further caution regarding the generalisability of these findings.

CONCLUSION

By advancing an understanding of the transmission of the entrepreneurial knowledge and skills amongst family-owned businesses as an altruistic occupation contributes to occupational legacy and economic occupations. Incorporating transgenerational and occupational lenses, parents engaged in connecting and contributing occupations to facilitate transitions of the children to successors of the FOBs while parents to retirees.

Although the findings should be interpreted with caution, this study has several strengths of passing down the legacy of parental family traditions and entrepreneurial knowledge. Another strength of the present study was the legacy of entrepreneurial skills (i.e., leadership, financial, technical, communication) passed down for the operations of the FOBs. This study offers some insight into entrepreneurial occupations that enable the parents and their children and grandchildren to achieve occupational identities, competence and adaptation. Thus, occupational therapists are challenged by the results to collaborate with the FOBs in the communities so that they consider entrepreneurial occupations as a medium to facilitate collective efforts to give back, lift others and satisfy wellbeing needs.

Author contributions

Thuli Mthembu supervised the research and reviewed the intellectual content of the project. All listed authors engaged in the conceptualisation of the research, literature review, research methodology, findings and structuring, prepared the content and wrote the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to financial or personal relationships that might inappropriately influence them in writing this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants who consented to share about their family-owned businesses

REFERENCES

1. Ndofirepi TM, Rambe P. A qualitative approach to the entrepreneurial education and intentions nexus: A case of Zimbabwean polytechnic students. Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management. 2018; 10(1), a81. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajesbm.v10i1.81 [ Links ]

2. Berkman LF. Commentary: The hidden and not so hidden benefits of work: identity, income and interaction. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2014; 43(5): 1517-1519. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu110 [ Links ]

3. Osunde C. Family businesses and its impact on the economy. Journal of Business and Financial Affairs. 2017; 6(1):251. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0234.1000251 [ Links ]

4. Gomes MR, Silva LAS, Michellon E, Souza SCI. Occupational legacy: An analysis of young people in rural work. Economia & Região, Londrina (Pr). 2020; 8(2): 169-189. https://doi.org/10.5433/2317-627X.2020v8n2p169 [ Links ]

5. Schnaubelt C. Transitioning your family business to the next generation. [2018 August 17; cited 2023 February 06]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/catherineschnaubelt/2018/08/17/transitioning-your-family-business-to-the-next-generation/?sh=47cc28067421 [ Links ]

6. Sindambiwe P. The challenges of continuity in family businesses in Rwanda [dissertation on the Internet]. Jönköping University Jönköping International Business School JIBS Dissertation Series No. 139; 2020. Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1431440/FULLTEXT01.pdf [ Links ]

7. Crider C, Calder CR., Bunting KL. An integrative review of occupational science and theoretical literature exploring transition. Journal of Occupational Science. 2015; 22(3)304-319. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2014.922913 [ Links ]

8. Twinley R. (Ed.) Illuminating the dark side of occupation: International perspectives from occupational therapy and occupational science. London: Routledge; 2021. [ Links ]

9. Beukes P. Unemployment-Grave economic injustice of our time: Compassion is not enough. Missionallia. 1999; 27(3):354-368. Available from: https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA02569507_669 [ Links ]

10. Department of Statistics South Africa. Republic of South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey: Quarter 1:2022. [cited 2023 February 06]. Available from: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02111stQuarter2022.pdf [ Links ]

11. African Family Business Survey 2021. From trust to impact: Why family business need to act now to ensure their legacy tomorrow. [2021; cited on: 31 January 2023]. Available from: https://www.pwc.co.za/en/press-room/africa-family-business-survey-2021.html [ Links ]

12. Farrington SM. Family business: A legitimate scholarly field. Inaugural lecture delivered at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. [2016 July 25; 2023 February 12]. Available from: http://fbu.mandela.ac.za/fbu/media/Store/Documents/ShelleyFarrington/Family-business-A-legitimate-scholarly-field-Prof-SM-Farrington-25-July-2016-Final.pdf [ Links ]

13. Gomba M, Kele T. Succession planning in Black-owned family businesses: A South African perspective. International Journal of Business Administration. 2016; 7(2): 9-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/ijba.v7n5p9 [ Links ]

14. Visser Τ, Chiloane-Tsoka E. An exploration into family business and SMEs in South Africa. Problems and Perspectives in Management. 2014; 12(4): 427-432. [ Links ]

15. Tatoglu E, Kula V, Glaister KW. Succession planning in family-owned businesses: evidence from Turkey. International Small Business Journal. 2008; 26(2): 155-180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242607086572 [ Links ]

16. Isaacs EBH, Friedrich C. Family business succession: Founders from disadvantaged communities in South Africa: An exploratory study. Industry and Higher Education. 2011; 25(4): 277-287 https://doi.org/10.5367/ihe.2011.0049 [ Links ]

17. Dalpiaz E, Tracey P, Phillips N. Succession narratives in family business: The case of Alessi. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2014; 38(6): 1375-1394. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12129 [ Links ]

18. Martin RM. Social entrepreneurial skills and practices of occupational therapists engaging in emerging community practice roles: A working theory of practice improvement (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). 2022; [Cited 2023 February 09]. Available from: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/2087 [ Links ]

19. Ramukumba TA. The 23rd Vona du Toit Memorial Lecture 2nd April 2014: Economic occupations: The 'hidden key' to transformation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 45(3): 4-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45n3/a2 [ Links ]

20. Sassen S, Galvaan R, Duncan M. Women's experiences of informal street trading and well-being in Cape Town, South Africa. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 48(1): 28-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2013-3833/2017/vol48n1a6 [ Links ]

21. Monareng LL, Franzsen D, van Biljon H. A survey of occupational therapists' involvement in facilitating self-employment for people with disabilities. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 48(3): 52-57 http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vol48n3a8 [ Links ]

22. Gamieldien F, van Niekerk L. Street vending in South Africa: An entrepreneurial occupation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 2017; 47(1): 24-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vol47n1a5 [ Links ]

23. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Disability. #Envision2030: 17 goals to transform the world for persons with disabilities (Online: 08 February 2023). Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/envision2030.html [ Links ]

24.Krakrafaa TTB. How do Businesses and generation maintain its legacy - A case of social interaction and knowledge transfer. Partridge: Africa; 2018. [ Links ]

25.Mthembu TG, Havenga K, Julies W, Mwadira I, Oliver K. Decolonial turn of collective occupations. (2023). South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 53(2): 43-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2023/vol53n2a5. [ Links ]

26.Lieberman S. A transgenerational theory. Journal of Family Therapy 1979; 1:347-360. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j..1979.00506.x [ Links ]

27.Schuler E, Brito Dias CMS. Legacies from great-grandparents to their descendants. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2023; 21(1): 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2021.1913275 [ Links ]

28.Chua JH, Chrisman JJ, Sharma P. Succession and Nonsuccession Concerns of Family Firms and Agency Relationship with Nonfamily Managers. Family Business Review. 2003; 16(2): 89-107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2003.00089.x [ Links ]

29.Buckman J, Jones P, Buame S. Passing on the baton: A succession planning framework for family-owned businesses in Ghana. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies. 2020; 12(2): 259-278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-11-2018-0124 [ Links ]

30.Hunter EG. Legacy: The Occupational transmission of self through actions and artifacts. Journal of Occupational Science. 2008; 48-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686607 [ Links ]

31. Korte J. Outliving the self: How we live on in future generations. New York: W.W Norton; 1996. [ Links ]

32. Biney IK. Unearthing entrepreneurship opportunities among youth vendors and hawkers: challenges and strategies. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship. 2019; 8:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-018-0099-y [ Links ]

33. Venter E, Boshoff C, Maas G. Influence of owner-manager-related factors on the succession process in small and medium-sized family businesses. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. 2006; 7(1): 33-47 https://doi.org/10.5367/000000006775870451 [ Links ]

34. Stephenson SM, Smith YJ, Gibson M, Watson V. Traditional Weaving as an occupation of Karen refugee women. Journal of Occupational Science. 2013; 20(3): 224-235. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.789150 [ Links ]

35. Riley J. Weaving an enhanced sense of self and a collective sense of self through creative textile-making. Journal of Occupational Science. 2008; 15(2): 63-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686611 [ Links ]

36.Ranja M, Scanlan J.N, Wilson NJ, Cordier R. Fostering transition to adulthood for young Australian males: An exploratory study of Men's Sheds' intergenerational mentoring programmes. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2016; 63(3): 175-185. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12259 [ Links ]

37. Kielhofner GA. Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application (4th ed). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [ Links ]

38. Phelan P, Kinsella E. Occupational identity: Engaging socio-cultural perspectives. Journal of Occupational Science. 2009; 16(2): 85-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686647 [ Links ]

39. Ferrari F. (2021). A theoretical approach exploring knowledge transmission across generations in family SMES. In Mehdi Khosrow-Pour DBA. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of organizational knowledge, administration, and technology. 1st ed. Hershey: IGI Global; 2021. p.1531-1550. http://doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-3473-1.ch105 [ Links ]

40. Butina M. A narrative approach to qualitative inquiry. Clinical Laboratory Science. 2015; 28(3): 190 - 196. https://doi.org/10.29074/ascls.283.190 [ Links ]

41. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 3(2): 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

42. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007; 19(6)349-357 https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [ Links ]

43. Clark P, Holden C, Russell M, Downs H. The imposter phenomenon in mental health professionals: Relationships among Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction. Contemporary family therapy, 2022; 44(2): 185-197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-021-09580-y [ Links ]

44. Nyman A, Isaksson G. Enacted togetherness - A concept to understand occupation as socio-culturally situated. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2021; 28(1): 41-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2020.1720283 [ Links ]

45. Grajo L, Boisselle A, DaLomba E. Occupational adaptation as a construct: A scoping review of literature. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 6(1). Article 2:1-14. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1400 [ Links ]

46. Shir N, Nikolaev BN, Wincent J. Entrepreneurship and well-being: The role of psychological autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Journal of Business Venturing. 2019; 34(5): 105875. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.05.002 [ Links ]

47. Hammell KW. Opportunities for well-being: The right to occupational engagement. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 84(4-5):209-222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417417734831 [ Links ]

48. Brown T. The response to COVID-19: Occupational resilience and the resilience of daily occupations in action. Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 68(2): 103 - 105. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12721 [ Links ]

49. Marshall CA, Lysaght R, Krupa T. Occupational transition in the process of becoming housed following chronic homelessness: La transition occupationnelle liée au processus d'obtention d'un logement à la suite d'une itinérance chronique. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 85(1)33-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417417723351 [ Links ]

50. Tsewu S. Meet the University of Fort Hare student who used his NFSAS allowance to start a farming business (Online 2023 February 07; cited 2023 February 08). Available from: https://www.news24.com/drum/inspiration/news/meet-the-university-of-fort-hare-student-who-used-his-nfsas-allowance-to-start-a-farming-business-20230207 [ Links ]

51. Meuser TM, Mthembu TG, Overton BL, Roman NV, Miller RD, Lyons KP, Carpenter BD. Legacy beliefs across generations: Comparing views of older parents and their adult children. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2019; 88(2): 168-186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415018757212 [ Links ]

52. Scaffa M, Reitz S, Pizzi M. Occupational therapy in the promotion of health and wellness. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 2010. [ Links ]

53. Wicks A. Understanding of occupational potential. Journal of Occupational Science. 2005; 12(3):130-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2005.9686556 [ Links ]

54. Boyle KA. Millenial career-identities: Reevaluating social and intergenerational relations. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2023; 21(1):89-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2021.1945989 [ Links ]

55. Buschendorf C. (Ed.) Cornel West: Black prophetic fire. Boston: Beacon Press; 2014. [ Links ]

56. Curasi CF, Price LL, Arnould EJ. How individuals cherished possessions becomes families' inalienable wealth. Journal of Consumer Research. 2004; 31(3):609-622. https://doi.org/10.1086/425096 [ Links ]

57. Blair SE. The Centrality of Occupation during Life Transitions. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000; 63(5): 231 - 237. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260006300508 [ Links ]

58. Burns A. Succession planning in family-owned businesses. Masters Thesis. University of Southern Maine. Available from: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd/547utm_source=digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu%2Fetd %2F54&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages [ Links ]

59. Jaskiewicz P, de Massis A, Dieleman M. The future of the family business: 4 strategies for a successful transition. [2021 April 15; cited 2023 February 07]. Available from: https://theconversation.com/the-future-of-the-family-business-4-strategies-for-a-successful-transition-156191 [ Links ]

60. Herdjiono I, Hastin Y, Maulany G, Aldy BE. The factors affecting entrepreneurship intention. Interational Journal of Entrepreneurship Knowledge. 2017; 5(2): 5-15. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijek-2017-0007 [ Links ]

61. Firfirey N, Hess-April L. A study to explore the occupational adaptation of adults with MDR-TB who undergo long-term hospitalisation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 44(3): 18-24 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Thuli Mthembu

tmthembu@uwc.ac.za

Submitted: 14 February 2023

Reviewed: 20 May 2023

Revised: 27 June 2023

Accepted: 6 July 2023

Editor: Blanche Pretorius: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3543-0743

Data availability: From the corresponding author

Funding: No funding was received for this research.