Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.53 no.3 Pretoria Dez. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2023/vol53n3a3

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Collaboration within a curriculum of support in the classroom: occupational therapists' and educators' perceptions and experiences

Patricia ArendseI, III; Lucia Hess-AprilII

IWestern Cape Education Department, South Africa; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9573-9363

IIDepartment of Occupational Therapy, University of the Western Cape, South Africa; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7496-0843

IIIAt time of study: Post-graduate student at University of the Western Cape, South Africa

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: According to South Africa's key education policies, all children can learn and need support, necessitating collaboration between occupational therapists and educators. Collaboration between occupational therapists and educators within the classroom is however a relatively new practice in South Africa and there is a dearth of literature that report on studies in this regard. The aim of this study was thus to explore occupational therapists' and educators' experiences in adopting a classroom approach in three primary mainstream schools in the Metro North education district in the Western Cape.

METHODOLOGY: A qualitative research approach and exploratory descriptive design was utilised. Data collection included semi- structured interviews and focus groups with educators and occupational therapists who participated in the curriculum of support in the classroom programme. Thematic data analysis was conducted.

FINDINGS: Three themes highlighting the meaning and value the participants assigned to classroom collaboration, and factors that facilitate or limit the implementation of the curriculum of support emerged from the analysis.

CONCLUSION: The study is useful in expanding the understanding of the changing role of occupational therapists within the context of inclusive education and contributes to the development of educator support strategies utilising the whole classroom approach. This approach entails the educator and occupational therapist working together in implementing activities in the classroom to all learners. These learning activities are based on curriculum themes and occupational therapy principles and components.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Occupational therapists' roles in the education practice context are expanding from traditionally working in special school settings to providing support to educators within public mainstream schools. The role of the occupational therapist within public mainstream schools is evolving from a consultative role and providing input into the individual support of learners to providing hands-on support to educators and collaborating with them within the classroom.

Keywords: inclusive education, learning barriers, classroom approach, trans-disciplinary collaboration, mainstream school, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Occupational therapist- educator collaboration within the classroom has gained momentum in South Africa since the move towards inclusive education and the development of related policies to ensure that the needs of vulnerable learners are addressed1. The policy on screening, identification, assessment and support (SIAS) standardises procedures to identify, assess and provide learner programmes for those who require extra support in an effort to enhance classroom and school participation and inclusion1. The SIAS aims to improve learner access to quality education and is aligned to the Integrated School Health Policy to ensure early identification of learners who experience barriers to learning and ensure the provision of effective support2. Likewise, the recently developed National Strategy for Learner Attainment (NSLA) is an overarching tool that informs provincial and district programmes to improve overall learner performance in line with the Action Plan toward Schooling 20303. The action plan speaks to curriculum delivery and support in schools and highlights a differentiated approach with particular focus on learners who experience barriers to learning. Prominentbarriers to learning identified in South Africa are emotional challenges, behavioural challenges, reading, spelling and language difficulties, intellectual disabilities, mathematics and perceptual challenges3. Poor participation in school related tasks due to barriers or difficulties in learning, contribute to poor educational outcomes4. Consequently, a high number of learners require support within public mainstream schools3.

In South Africa, a study conducted to explore educators' understanding of inclusion and barriers to learning highlighted that they are expected to develop strategies to provide quality educational opportunities for learners who have diverse needs4. For this reason, occupational therapist-educator collaboration in facilitating inclusive education in mainstream schools has become imperative5.

This is particularly significant in the post COVID-19 lockdown period and its influence on learners, particularly in relation to the loss of knowledge and skills suffered by the learners as a result of disruptions in the school calendar. Collaboration implies occupational therapists and educators working together to address learning needs in an effort to make the curriculum accessible to all learners5

There is however a need for a better understanding of this process of collaboration and how occupational therapists and educators can work together within a classroom approach. This article reports on a study that explored occupational therapists' and educators' experiences in adopting a classroom approach to enhance inclusive education in three primary mainstream schools in the Metro North education district in the Western Cape.

Literature review

Primary school learners are expected to engage in a wide variety of scholastic tasks that involve activities that require fine and perceptual motor skills (e.g. handwriting and copying from the board), gross motor skills (e.g. kicking, jumping, hopping, throwing, catching) and social skills (e.g. socialization and personal care activities)6,7. Learners with learning difficulties may however experience challenges in accomplishing these tasks with subsequent social, vocational, academic and psycho-emotional consequences7.Occupational therapists enable learners who experience learning difficulties by addressing the underlying components of function; by adapting learning and teaching strategies utilised in the classroom, or by adapting aspects of the school environment6. Successful intervention however requires collaboration between educators and occupational therapists to work as teams in order to offer support and make education inclusive to those learners with barriers to learning in the classrooms -as has been the case in some public special schools in South Africa8.

Two studies that explored elementary teachers' perceptions of the value of collaboration with occupational therapists in the United States validated the need for improved occupational therapy supports in the school environment9,10. These studies further highlighted that teachers perceived collaboration with the occupational therapist as valuable for providing effective classroom strategies and a positive influence on student success9,10. Thus, a growing body of literature presents compelling evidence for the benefits of collaboration among educators and occupational therapists as educators perceive occupational therapists to be playing an important role in providing support within a school setting9,10,11,12.

Addressing the diverse needs of learners and the learning barriers they encounter in the classroom is generally experienced as challenging by educators12,13,14. A study conducted in selected Fort Beaufort district primary schools in South Africa established that teachers experienced lack a of parental participation, heavy workload, inadequate training, and lack of resources in implementing the inclusion of learners with special education needs13. However, a shift from a focus on individual student goals, to consultative services focused on capacity building of educators, can enhance occupational therapy service delivery within schools and effect change for a diverse learner population 15,16.

There is however an apparent paucity of evidence to describe how school participation is enabled in South Africa. A South African study that explored the collaborative relationship between educators and occupational therapists in junior primary mainstream schools in Kwazulu Natal indicated that educators regarded collaboration with occupational therapists as instrumental in developing their ability to identify learning barriers5. Working together with educators in adopting a whole classroom approach is therefore important in improving the educational outcomes of learners who experience barriers to learning14,15. While collaborative consultation between occupational therapists and educators is regarded as a vital tool for assisting learners who experience learning barriers8, there are factors that may negatively influence such collaboration. These include a key barrier related to how services are designed and implemented across health and education, with different underlying philosophies to practice8; educators' poor understanding of occupational therapy services and the concept of inclusive education16,17,18; as well as time constraints and limited contact between educators and occupational therapists5,12,17.

Studies that explore occupational therapist-educator collaboration in the classroom can be useful to guide the development of collaborative relationships and transdisciplinary interventions to enhance inclusive education, Nevertheless, a dearth of literature exists that reports on studies that explore collaboration between occupational therapists and educators while making the curriculum accessible to all learners. This article reports on a broader study that aimed to explore educator-occupational therapist collaboration in the implementation of a curriculum of support in the classroom programme to address learning support strategies in three primary mainstream schools in the Metro North education district in the Western Cape. In particular, we discuss one of the objectives of the study, i.e. to explore and describe occupational therapists' and educators' perceptions and experiences regarding trans-disciplinary collaboration within the classroom.

Curriculum of support in the classroom program: Overview

An occupational therapy intervention programme was implemented in the Metro North Education District in the Western Cape in 2012 but has gained recent momentum because occupational therapists working in Special Schools are required to perform an outreach function in mainstream schools by the Western Cape Education Department (WCED), The programme was specifically designed for Grade R and Grade 1 'at risk' learners. The district- based support team (DBST) that includes an occupational therapist, meets to select the public mainstream schools where the programme will be implemented. This is followed by a series of workshops with educators where after the programme is implemented in each school and monitored by the DBST. In this programme, occupational therapists and educators work collaboratively to support learners who experience barriers to learning . The four key components of the programme are 1) Training of educators and therapists in the Grade R Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS)19 2) Collaborative design of a developmental support and stimulation programme; 3) Training of educators in the utilisation of the support and stimulation programme and 4) Implementation of the support and stimulation programme,

While the Grade R CAPS19 informed the design of the training programme, the Grade Ras well as Grade 1 educators participate in the programme. Instead of merely providing instructions, occupational therapists join educators in the classroom and facilitate relevant skills as guided by the CAPS.

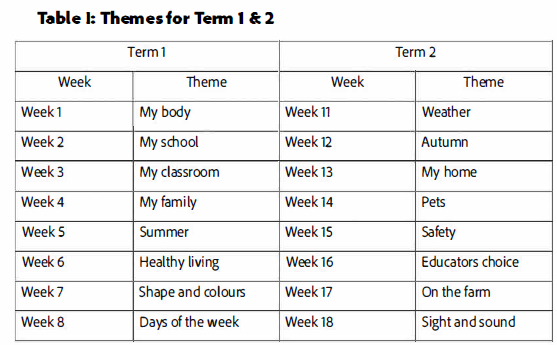

This is generally preceded by educators attending interactive workshops that are presented by the occupational therapists. Following the workshops, the occupational therapists join educators in the classroom to implement the stimulation programme over an 8-week period. The occupational therapist spends 1 hour with each Grade R practitioner and Grade 1 educator in their classrooms, with support to a minimum of 3 educators provided in the classroom per week, The 8-week programme covers the following; 1) occupational therapists demonstrate the activities of the specific theme with learners to the educator in the classroom, 2) the educator presents a theme to the occupational therapist who acts as facilitator and 3) the educator presents the theme with minimal facilitation from the occupational therapist. Activities concentrating on skills development inclusive of stimulation programmes focussing on auditory, listening, perceptual, language and gross and fine motor skills are geared towards the theme and aim for the week (Table I, below) and also involves setting developmental outcomes, activity requirements, structuring and grading.

METHOD

Research setting

The research setting for this study was three primary mainstream schools in the Metro North education district of the Western Cape with large learner totals in the classrooms, The three schools are located in two townships geographically located on the outskirts of Cape Town i.e. two schools in Atlantis and one in Delft. The Atlantis and Delft townships are characterised by poor socio-economic conditions, i.e. poverty, a high rate of unemployment and crime. Many learners come from single-parent homes, grandparent homes and foster homes where families are dependent on government grants. The learners have a general lack of stimulation at home. All three schools benefit from the National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP).

The schools are generally under-resourced; classes are large, and educators often buy resources from their own funds as parents very seldom can afford to buy stationery for their children. The two schools in Atlantis are government funded and classified as non - fee paying schools. The two schools in Atlantis each have an average of 1300 learners attending and 33 teaching staff that includes heads of departments, deputies and principals. The school in Delft is also a non - fee paying school which means that parents are exempted from paying school fees. The school accommodates 1177 learners and also has 33 teaching staff. The grade 1 pass rate at all three of these schools was identified as a concern by the education circuit manager in the district. Accordingly, the DBST also identified that the three schools required additional support for the learners.

Research Design

A qualitative research approach20 within an exploratory descriptive study design21 was utilised to explore collaboration between educators and occupational therapists in the curriculum of support within the classroom programme.

Sampling

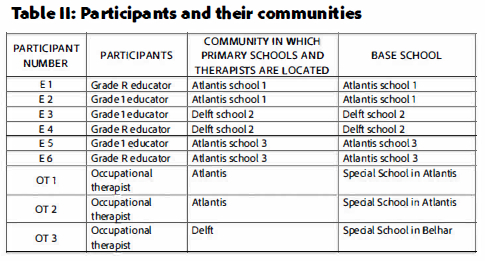

The study population comprised all occupational therapists and educators who participated in the curriculum of support in the classroom programme. Purposeful sampling21 was utilised to select a sample of six educators and three occupational therapists (Table II, below). The criteria for selection of the sample included Grade R and Grade 1 educators and therapists who were involved with the compilation of the manual for the programme; Grade Rand Grade 1 educators and therapists who participated in the implementation of the programme in the three primary mainstream schools.

Data collection methods

Semi- structured interviews and focus groups were utilised as data collection methods. Individual semi-structured interviews were used to gain participants' views, feelings, perceptions and experiences17 about the curriculum of support and educator-occupational therapist collaboration. The interviews were conducted with two educators in each of the three mainstream schools as well as with the three occupational therapists who were based at public special schools and performed an outreach function in the public mainstream schools of which two were in Atlantis and one in Delft. The occupational therapists were based at Public Special Schools in the Metro North Education District and implemented the curriculum of support programme at three Primary schools in the same district.

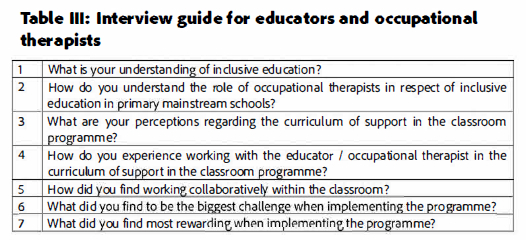

This was part of an initiative taken by the Department of education to address inclusive education in public mainstream schools. Two occupational therapists were based at a special school in the Atlantis area and implemented the programme in two separate Primary schools in that area. One occupational therapist was based in a special school close to the Delft area and thus implemented the programme in a Public school in the Delft area. Interviews were conducted until data saturation occurred i.e. no new information materialised. Interviews lasted for about 45 minutes to an hour. The focus of the interviews ranged from the participants' understanding of inclusive education to their perceptions and experiences of collaboration in the classroom (Table III below).

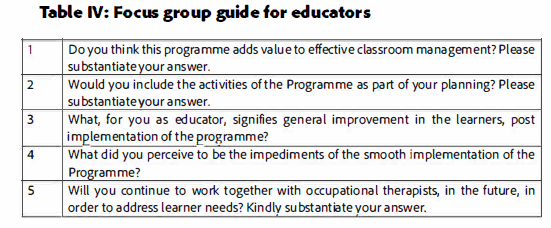

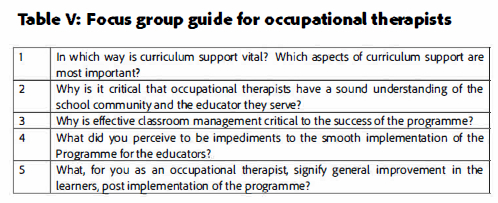

Focus groups are advantageous as it allows a space where people can get together to jointly discuss issues and thus create meaning collectively20. In this study, the issues focussed on occupational therapists and educators' perceptions and experiences regarding trans-disciplinary collaboration within the classroom. The purpose of the focus groups was thus to explore issues that surfaced in the individual interviews regarding participants' perceptions and experiences with the curriculum of support programme and required clarification or a more in-depth exploration. Thus, the focus group guide for educators (Table IV below) and occupational therapists (Table V, page 17) was compiled after a preliminary analysis of the interviews, allowing for similar and opposing opinions to surface. One focus group was conducted at each of the three primary mainstream schools with the Grade R and Grade 1 educators and one focus group was conducted with the occupational therapists. Each focus group lasted for about one hour. All interviews and focus groups were audio taped and transcribed verbatim for the purpose of data analysis. The thematic data analysis framework21 was utilised to analyse the interview and focus group transcripts.

Trustworthiness

The Lincoln and Guba24 framework guided the implementation of trustworthiness strategies. Credibility was ensured through member checking where the preliminary findings were presented to the participants. Transferability was endorsed through a detailed description of the research context, while an in-depth description of the research process from the start of the project to the reporting of the findings allowed for dependability. In addition to a detailed record of the research process, a trail of data and analysis was kept throughout the study and deposited into the university's research repository to allow for an inquiry audit in order to ensure confirmability.

Ethics

This study conformed to ethical standards of scientific inquiry, including ethics approval by the Humanities and Social Science Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape (REC number - 130416-04) as well as the Western Cape Department of Education. All participants provided formal written and informed consent. Participation was voluntary and participants could withdraw from the study at any time without being penalised. Confidentiality was maintained by securing data in a password protected electronic folder and this will remain stored in the university's research repository for a period of five years following the completion of the study after which it will be destroyed. By referring to participants in terms of allocated numbers, their anonymity is maintained. All participants have access to the findings of this study.

FINDINGS

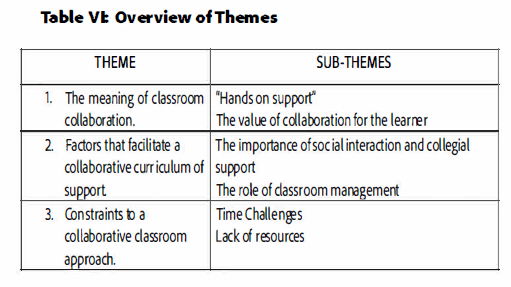

Three themes with related sub-themes emerged from the thematic analysis: 1) The meaning of classroom collaboration, 2) Factors that facilitate collaborative implementation of the curriculum of support, and 3) Factors that inhibit a collaborative classroom approach to inclusion (Table VI. below).

Theme 1: The meaning of classroom collaboration

The first theme highlights the meaning that educators and occupational therapists assigned to collaboration as supported by how they understood working together in implementing the classroom approach.

"Hands on support"

For both the occupational therapists and educators, collaboration implied direct physical i.e. actual 'hands on' support provided by the occupational therapists in the classroom.

"When the programme took place the occupational therapists came in and then gave us hands on training in the classroom....They were an asset in ourclassroom, working with us." (Interview, ES).

The educators' understanding improved when they jointly engaged in demonstrations and discussions on strategies to support learners who experience barriers to learning. Through working together, the educators and occupational therapists were able to observe each other, within their roles, as they together engaged in activities with the learners.

"We would focus on how they were teaching and then transferring skills and equipping the educator to stimulate the children in different ways so that they could access the curriculum" (Interview, OT3).

Some educators were positive about their participation and were open to learn within their classroom but some educators were initially hesitant and not as cooperative as others were as they were uncertain about programme expectations.

"There were educators that were very willing and eager to participate andto learn and opened their environment and their space to enter... Some educators were a bit hesitant and not so cooperative like some of the others were because they were not sure about the demands on them" (Interview, E6).

While the educators generally understood the need for the curriculum of support, ensuring an understanding that the classroom support programme was not an 'add on' to the curriculum was key to the collaborative relationship.

"The curriculum of support was directly taken from the CAPS so we made them understand and they could see that the themes t h a t they uhm implemented within their activities and scholastic tasks, what was written up (in the programme) they could see that it linked with the CAPS"' (Focus Group: OT2).

Finding some educators more willing to participate than others helped the occupational therapists to appreciate the importance of understanding the school community as this affected collaboration. The occupational therapists emphasised the principle of context first and stressed that they first had to understand the conditions under which educators worked before they could provide relevant and effective support.

"... if you know what the context is, you can know where you can assist and where you need to stand back... it's good to have knowledge about it (context) because when you get to the class and the educator didn't do (the activities) then you have that negative mind-set already... but if you understand the reason why, it makes it better." (Focus Group: OT1).

The value of collaboration for the learner

The educators perceived that the learners enjoyed the different sessions and activities with the occupational therapists evident in their improved behaviour.

"You get learners that have behaviour problems but when you have the occupational therapist here at school, they just have the way of listening to that person ...Discipline in my class improved and learners were really listening. Behaviour was better, it wasn't as bad as previously....It (the programme) got learners more involved." (Interview, E4).

The educators were aware that the learners looked forward to the sessions and acknowledged that learners improved in sitting posture, gross motor skills and handwriting.

"Some learners always just wandered around during group activities, but now you see them come closer and wanting to be part of what is happening... You see the kids develop well and those muscles, you can see that the posture is not limp or clumsy anymore and their handwriting is better" (Interview, E6).

In their feedback to the occupational therapists the educators expressed that they valued their input as the value of the improved curriculum became evident.

"...with regards to the learning areas of maths and uhm literacy, also the activities for gross motor that we brought in... the educators said that there's really improvement within the curriculum" (Interview, OT2).

"So, the programme is a very good programme, the stimulation programme ... it really works and we are using it now in our planning. We continue to implement it"(Focus Group: E6).

Theme 2: Factors that facilitate a collaborative curriculum of support

This theme illustrates the importance of professional and inter-personal relationships in the facilitation of a collaborative curriculum. It further captures the participants' views on the value of factors such as having opportunities and a collaborative space to discuss ideas, challenges and new concepts.

The importance of social interaction and collegial support

The occupational therapists highlighted social interaction and collegial support as important facilitating factors of a collaborative curriculum of support. For the occupational therapists' social interaction with the community, including learners, teachers, heads of departments, deputies and principals, was an important vehicle to being understanding and relevant when implementing the curriculum of support.

"... that social interaction of knowing the school community and the educator that we are serving ...that also came through as having a better relationship even though you are a professional from a different field, ja, sharing as colleagues..." (Focus Group: OT3).

The participants stressed the importance of having a space to express their thoughts and feelings about the successes and challenges they encountered in the classroom. The educators often referred to the feedback sessions they had with the occupational therapists after each implementation session. Educators were encouraged to discuss their successes and challenges and to make recommendations.

"Normally we plan together, the programme in the manual has been worked out according to weeks so we plan and share ideas together." (Focus Group: E1).

"We talk about and work together on those activities that you maybe want to do with the child, how to downgrade and work on the child's level" (Interview, E6).

Reflective sessions after each classroom session as well as after each term with the rest of the DBST and learning support advisors were also highlighted as facilitators of the process.

"We have term meetings with the rest of the metropole north therapists,where we present our feedback. it's good that the broader team and advisors can also hear our experiences" (Interview, OT2).

The role of classroom management

Effective classroom management was highlighted as another facilitating factor of the curriculum of support. The occupational therapists explained that when they came into a class where the educator managed her learners well, they observed that the programme was implemented more efficiently and progress could be seen, particularly in respect of learners' behaviour.

"I would say that effective classroom management is important as it motivates learneces misbehaviour and it improves discipline and sets routine and consistency" (Focus Group OT1).

Educator preparedness signalled an openness to learning which was appreciated by occupational therapists who could then focus on the transfer of skills. If an educator struggled with managing her learners, the occupational therapist would assist although classroom management is the educator's responsibility.

"Where I saw the ideal classroom management is where I could actually see that the educator did some of the work already the day before or in theweek... it was the second time, third time ...now they are in a space where they can perfect whatever is required and the educator is more comfortable...so it's easy to assist" (Focus Group: OT3).

"She (educator) also needs to bring her part into managing the classroom It cannot be the responsibility of the person (occupational therapist) coming in although they would be willing to assist" (Focus Group: OT1).

In relation to the role of classroom management, the educators acknowledged that it was important but simultaneously highlighted that the time they had available sometimes hamper this and their preparedness to work with the OTs in implementing the programme.

"Sometimes available time interfere with being prepared and the OTs are not always happy as the children are not used to the programme because I didn't have time to prepare the class then she still has to assist with that ... and then you've only got maybe 15 mins left to really implement." (Focus Group: ES).

Theme 3: Constraints to a collaborative classroom approach.

Constraints to working together in a collaborative classroom approach as experienced by the participants mainly related to the school context. The participants were asked to reflect on the difficulties they encountered in relation to implementing the collaborative classroom approach. Some educator participants struggled to find time to implement the classroom programme due the demands of the CAPS curriculum, while large learner totals ingrained the inefficiency of the resources that were available to the educators.

Time challenges

Finding time in the timetable to implement the classroom programme proved a challenge for the educators, particularly for grade 1 educators who had curriculum deadlines. Some educators, however, were very curriculum focused because of the outcomes that needed to be achieved within a specific time.

"Educators were more focussed on the curriculum demands and the deadlines that they needed to reach, so they saw the program or the activities as extra work" (Interview, OT1).

"So they just expect us to come in there, and expect us to run through the program because it's really time consuming, because we must fit it in between lessons" (Focus Group: E2).

Gaining support from curriculum advisors was one way in which time challenges could be addressed from the perspectives of the occupational therapists. They felt that in this way they could play a role in monitoring the programme and assist educators to set times to plan and implement the continued programme.

"So yes it's great for them (curriculum advisors) to know about it when they read reports but it's great for them to actually experience it, to be excited to come and see the value in it and then to ensure that the programme continues" (Interview, OT2).

Lack of resources

The mainstream schools were generally characterised by large classes and while it posed a challenge for the educators, it particularly did so for the occupational therapists who were used to working with individual learners or groups of 8 - 12 learners in the special schools.

"So the biggest challenge is the big classes... A big challenge for me is when a class is 50, 56, 59. I think 59 was the biggest class I've ever had to work with." (Interview, OT3)

"The space was so limited because the classrooms were small." (Interview, OT1).

Large learner totals meant that educators encountered a shortage of materials and basic equipment as required by the programme. In an effort to cope with the scarcity of resources, educators often brought items from home or used personal finance to buy materials.

"When it comes to apparatus we don't have all the equipment... things that's recommended in the programme manual" (Interview, E4).

And the apparatus that is used you have in your classroom or you can bring things from home or your learners can bring it from home...or we just went and bought the items with our own money so that the apparatus were in the classroom. (Focus Group: E3).

The implication for some however was that educators skipped certain activities because of insufficient resources.

"Like the resources we don't have, we will skip them (activities in the programme) we will skip, as we have no choice." (Interview, E4).

DISCUSSION

The role of the occupational therapist within inclusive education, in particular within the foundation phase of public mainstream schools in South Africa, is transforming into a much broader role. The SIAS policy promotes district and school based support services by a variety of professionals, including occupational therapists to enhance classroom and school participation, and inclusion of all learners1. The implementation of inclusive education policy in South Africa is reliant on school district teams, with the occupational therapist as a member of the team acting as key resource for educator involvement and support. Occupational therapists address underlying components of function by adapting learning and teaching strategies utilised in the classroom910, or by adapting aspects of the school environment6; and are perceived as playing an important role in providing support within a school setting5,14,15,16.

This study thus makes an important contribution to understanding the value of educator-occupational therapist collaboration and hence strengthens the argument for increased allocation of occupational therapy posts within mainstream schools in South Africa.

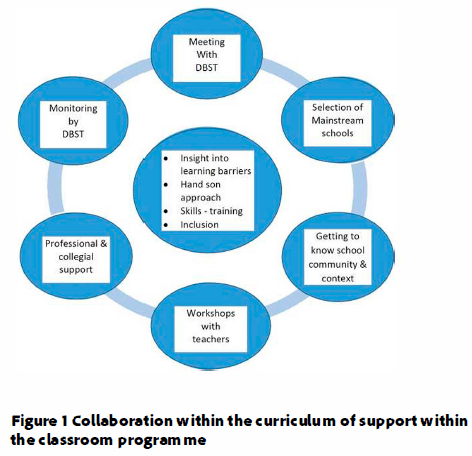

Based on the rationale that there is a need for a better understanding of how occupational therapists and educators can work together in the classroom, the findings of this study are useful in generating an understanding of how factors important for collaboration could enhance the curriculum of support in the classroom programme. The initial process of programme implementation entailed the DBST meeting to select the public mainstream schools, followed by a series of workshops with educators where after the programme was implemented and monitored by the DBST. It however emerged that a process that entail occupational therapists making an effort to understand the school context, fostering professional and collegial support, providing hands-on support by focussing on learning barriers and specific skills-transfer to educators enhance the process of educator-occupational therapist collaboration. Figure 1 (below) illustrates this process based on the findings of this study.

The role of the educator is high lighted in the SIAS policy and identifies educators as the first level of support to the learner in the classroom1. Educators are expected to understand learning barriers and the ability to identify learners who require support25,26 . Educators therefore need to have a comprehensive understanding of inclusion and learner diversity25,26,27. Based on educators' feedback regarding the value of the programme, they require opportunities to share their experiences and knowledge and to apply what they have learnt within their own context25,27.lt is evident that educators benefit from hands-on support and demonstrations from occupational therapists to improve their skills and knowledge regarding a classroom approach to the management of learning difficulties.

Collaboration with occupational therapists is imperative for educators teaching in overcrowded classrooms, particularly when drawing up lesson plans. Debriefing sessions and opportunities for social interaction are key indicators for moral support not only for educators but also for occupational therapists who have to deal with large learner totals. Then there are additional challenges to navigate such as limited resources in addition to learners who experience barriers to learning. This is particularly significant in the post COVID-19 period where educators have to address its influence on learners, particularly in relation to the loss of knowledge and skills the learners experienced because of disruptions brought on by the pandemic. The impairment of children's cognitive development was identified as a specific challenge that resulted from the COVID-19 disruptions in schools28. This is not only the responsibility of the educator and accordingly, the study holds implications for the DBST. In order to successfully establish an inclusive training and education support system, a DBST needs to be at the foundation of the system25,26.

Where possible, successes as well as constraints to collaboration should be presented to the DBST and school management team members in order for it to be addressed at management level as a shared responsibility and as part of monitoring programme interventions29. The DBST and in particular curriculum advisors, are pivotal in assisting educators in formulating lesson planning, providing demonstration lessons and providing support with classroom management for those who need it to ensure inclusive practices in schools. Thus, they should ensure that the DBST collectively address allocation of time for the implementation of the curriculum of support in the classroom.

The study raises the question of whether occupational therapy education adequately prepares occupational therapists to work with educators within classrooms with all its constraints and thus have clear implications for the formal education of occupational therapists. It is imperative that occupational therapy curricula develop graduate competencies in collaboration. The occupational therapy curriculum should incorporate methods to equip students to work within a whole classroom approach and not only with individuals or small groups as this will enable them to support educators and collaborate with them effectively within the classroom.

CONCLUSION

This study set out to provide an understanding of collaboration whereby occupational therapists entered the classroom and worked with educators promoting and adopting the classroom approach to inclusive education. While a limitation of the study is that it was conducted within three primary mainstream schools in one education district only, the findings showed the value of collaboration in the curriculum support in the classroom programme. This was not just the case for learners, but in particular for educators, who despite constraints like large learner numbers, time constraints and inefficient resources, remained motivated to work towards making learning accessible to all learners and to work towards CAPS outcomes while experiencing professional and collegial support. Collaboration and providing simultaneous support to educators have become even more imperative as educators have to deal with the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on learners' academic abilities. This study is consequently useful in expanding the understanding of the changing role of occupational therapists within the inclusive education setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for their contributions to this study.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Patricia Arendse conducted the study under the supervision of Lucia Hess-April. Both authors made substantial contributions to the conceptualisation of the research, and the drafting and revising of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Department of Basic Education. Policy on Screening, Identification, Assessment and Support. 2014. ELSEN Directorate. Government printers: Pretoria. [ Links ]

2. Departments of Health and Basic Education. Integrated school health policy. 2012. Government Printers, Pretoria. [ Links ]

3. Department of Basic Education. Action plan to 2024: towards the realisation of schooling 2030: taking forward South Africa's National Development Plan 2030. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. 2020. [accessed 2022January 26] https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Publications/Sector%2Opla n%202019%2015%20Sep%202020.pdf?ver=2020-09-16-130709-860 [ Links ]

4. Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M., Nel, N. & Tiale, D. Enacting understanding of inclusion in complex contexts: classroom practices of South African educators. South African Journal of Education. 2015, 35: Vl-10. [ Links ]

5. Hargreaves, AT, Nakhooda, R., Moccupational therapisttay, N. & Subramoney, S. The collaborative relationship between educators V and occupational therapists in junior primary mainstream schools. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012, 42(1):7-10. [ Links ]

6. Vlok, E. D., Smit, N. E., Bester, J. A Developmental approach: a framework for the development of an integrated Visual Perception programme. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011, 41(3): 25-33. [ Links ]

7. Ratcliffe, I., Franzsen, D., Bischof, F. Development of a Scissors Skills Programme for Grade 0 Children in South Africa - A Pilot Study. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011, 41(2): 9-15. [ Links ]

8. Kungwane, S. & Boaduo, M. The Collaborative Partnership between Teachers and Occupational Therapists in Public Special Schools in South Africa. Semon, S.R, Lane, D. & Jones, P. (eds). Instructional Collaboration in International Inclusive Education Contexts (International Perspectives on Inclusive Education. 2021, Vol. 17, Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, pp. 115-126. [ Links ]

9. Zahava L. Friedman, Kurt Hubbard & Francine Seruya Building Better Teams: Impact of Education And Coaching Intervention on Interprofessional Collaboration Between Teachers and Occupational Therapists in Schools, Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2022.2037492 [ Links ]

10.Jennifer Edick, Shirley O'Brien & Leslie Hardman. The Value of Collaboration with Occupational Therapists in School Settings: Elementary Teacher Perspectives, Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2022.2054488 [ Links ]

11.O'Donoghue, C.; O'Leary, J. & Lynch, H. Occupational Therapy Services in School-Based Practice: A Paediatric Occupational Therapy Perspective from Ireland. Occupational Therapy International. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6636478 [ Links ]

12. Srivastava, M., De Boer, A., Pijl, S.J. Inclusive education in developing countries: a closer look at its implementation in the last 10 years. Educational Review. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.847061 [ Links ]

13. Adewumi, T.M. & Mosito, C. Experiences of teachers in implementing inclusion of learners with special education needs in selected Fort Beaufort District primary schools, South Africa. Cogent education. 2019, Vol, No 1 . https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1703446 [ Links ]

14. Sonday, A., Anderson, K., Flack, C., Fisher, C., Greenhough, J., Kendal, R., Shadwell, C. School-based Occupational therapists: An exploration into their role in a Cape Metropole Full Service School. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012, 42(1): 2-6. [ Links ]

15. Bonnard, M. & Anaby, D. Enabling participation of students through school-based occupational therapy services: Towards a broader scope of practice. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016, Vol. 79(3) 188-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022615612807 [ Links ]

16. Laverdure P. Considerations for the development of expert practice in school-based occupational therapy. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools & Early Intervention. 2014, 7(3-4): 225-234. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2014.966016 [ Links ]

17. Jackman, M., Stagnitti, K. Fine motor difficulties: The need for advocating for the role of occupational therapy in schools. Australian Occupational Therapy Jounal. 2001, 58 (3): 168 - 173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00628.x [ Links ]

18. Bolton,T. & Plattner, L. Occupational Therapy Role in School based Practice: Perspectives from Teachers and OTs. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2020, 13:2, 136-146, https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2019.1636749 [ Links ]

19. Department of Basic Education. Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement Pretoria: Department of Basic Education. 2012. [accessed 2021 March 20] https://www.education.gov.za/Curriculum/CurriculumAssessmentPolicyStatements(CAPS)/CAPSFoundation.aspx [ Links ]

20.Henning, E., Van Rensburg, W., Smit, B. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. 2004. [ Links ]

21.Babbie, E., Mouton, J. Qualitative Studies. The practice of social research. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. 2001. [ Links ]

22.Bryman, A. Social research methods 5th edition. Oxford: Oxford university press. 2016. [ Links ]

23.Braun, V., Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006, 3 (2):77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

24.Lincoln, Y.S., Guba E.G. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage publications. 1985. [ Links ]

25.Nel, N., Tiale, L., Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M. Teachers' perceptions of education support structures in the implementation of inclusive education in South Africa. Koers. 2016, 81(3). https://doi.org/10.19108/KOERS.8L3.2249 297. [ Links ]

26.Dalton, E., Mackenzie. J. &. Kahonde, C. The implementation of inclusive education in South Africa: Reflections arising from a workshop for educators and therapists to introduce universal design for learning. African Journal of Disability 2012, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v1i1.13 [ Links ]

27.Bose, P. &. Hinojosa, J. Reported experiences from occupational therapists interacting with educators in inclusive early childhood classrooms. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008, 62: 289 - 297. [ Links ]

28.Spaull, N. &. Van der Berg, S. Counting the cost: COVID-19 school closures in South Africa and its impact on children. South African Journal of Childhood Education. 2020, 10(1), a924. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v10i1.924 [ Links ]

29.Department of Basic Education: South African's Schools Act: Policy on the Organisation Roles and Responsibilities of Education Districts. 2012, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Lucia Hess-April

lhess@uws.ac.za

Submitted: 18 May 2022

Reviewed: 22 September 2022

Revised: 16 May 2023

Accepted: 16 August 2023

Editor: Blanche Pretorius: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3543-0743

Data availability: From the corresponding author

Funding: The National Research Foundation is acknowledged for supporting a scholarship for the principal author towards her Masters, from which this paper emanates.