Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.53 no.2 Pretoria ago. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2023/vol53n2a9

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Assessment of participation in collective occupations: Domains and items

Fasloen AdamsI, II; Daleen CasteleijnII

IDivision of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Fasloen Adams: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6742-3727

IIDepartment of Occupational Therapy School of Therapeutic Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Daleen Casteleijn: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0611-8662

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Occupational therapists work with groups of people who engage in collective occupations to have a positive influence on their health and wellbeing. Although the concept of collective occupations is described and defined in occupational science literature, little has been done on specific assessment tools to guide clinicians on how well people are engaging in collective occupations

AIM: This article describes the development of an assessment tool to assess participation in collective occupations in a South African context

METHOD: A mixed methods approach with a sequential exploratory design was used. Domains and items were generated from a literature review on collective occupations as well as semi-structured interviews with occupational therapy experts in community settings. Data were thematically analysed using a priori coding. The Vona du Toit Model of Creative ability was used to frame the coding. Domains and items emerged from the data

RESULTS: The result was the development of five domains and 19 items that could be used to measure and describe collective participation in occupations. Domains include collective's motivation, ability to perform action, ability to form a collective, ability to produce and end product, emotional-cognitive functioning and collective relations

Implications for practice:

To work with groups of people, clinicians not only need to understand the nature of collective participation but also need to understand why people participate in them. They should also have insight in the abilities needed to effectively participate as a collective. Understanding of a collective's behaviour in the above-mentioned domains, could guide occupational therapists in planning intervention to enhance collective participation in occupations. The levels of collective participation could guide occupational therapists to gain insight into the potential and behaviour of collectives. Such understanding can enable effective intervention-, preventive- and promotive health programmes with collectives.

Keywords: Collective Participation, Co-occupation, VdTMoCA, creative ability, occupational therapy, health programmes

INTRODUCTION

When the concepts of collective occupation emerged in occupational science theory, it was linked to the social development of human beings including the need to belong or be part of a collective1, 2. An important consideration in occupational therapy is the benefits of people participating in collective occupations and maintaining this ability2, 3, 4, 5. Collective action and/or collective participation in occupations is seen as a powerful concept for communities to change their situation for the better. Linking to this, as a profession, occupational therapy can contribute to addressing determinants of health and to decrease social inequality by facilitating occupational participation. This role is often performed in a primary level of health care and community-based settings and includes working with individuals and collectives through health promotion and prevention programmes6.

In South Africa, services in communities and social development sectors4, 7, 8 focus not only on individuals but also on collectives of people to facilitate better health and wellbeing. Additionally, many occupational therapists use community-based rehabilitation and development principles that advocate for intervention on a collective level rather than on an individual one. This focus on a collective level raises three concerns. Firstly, current profession-based theories, models and tools draw attention to the understanding of and working with the individual rather than with collectives9, 10, 11, 12 . Secondly, occupational therapy group related literature concentrates on therapeutic groups formed by clinicians. There is little published in occupational therapy on naturally formed groups such as those formed by members itself due to shared needs 13 which are common to community and primary levels of care. Clinicians working with these groups are applying current theories and models to collectives without evidence to support the effectiveness of such application. Lastly, discourse around collective occupation has been focussed on definitions and descriptions of collective participation, with limited suggestions on classification and tools for measurement thereof4 .

Several measurement tools are available to assess individual's occupational performance14 . However, none have been developed with collective occupational participation in mind. Although there are guidelines and measurement tools to describe community participation15 , none describe collective occupational participation. Similarly, group functioning scales and measurements of group processes, assess the group process from an individual point of view and do not emphasise the performance of the collective.

Fogelberg and Frauwirth16 developed a framework to describe collective participation in occupations as 'occupational systems'. They identified three levels to describe how occupation can be performed by collectives; group, community and at population level. Similarly, the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework17 describes performance patterns for groups and populations and includes group intervention as a type of occupational therapy intervention. Both frameworks give a brief description of collective behaviour on these levels, but these cannot be used to measure the ability or inability to collectively participate in occupations. There is thus an awareness of the importance of collective participation, but assessment and intervention guidelines of collective participation are areas that need further investigation.

The Vona du Toit Model of Creative ability (VdTMoCA) is a model often used by South African occupational therapists18. Although this model is used with individual clients, there are fundamental concepts in this model that recognise the importance of the collective. Du Toit 19 postulated that people on lower levels of creative ability are focused on egocentric needs while higher levels transcend the self and contribute towards communities and societies in a constructive, selfless way. Higher levels of creative ability realise the benefits of working as a collective. Du Toit19:11 further explained mutuality as "being responsible together" and quoted Nel who said that "Man is only then a human being in his directedness towards other human beings"19:5. Humans thus have a need to communicate with others and to be part of a collective, but these needs only emerge from the level of Passive Participation (level four) and increase in quality and dimension in the higher levels. The levels of creative ability show increasing amounts of motivation and action in people and these levels could be explored to measure collective participation in occupations.

Levels of community participation were described by Thomas and Thomas20 in five levels. The lowest level describes a community who receives services but contributes nothing in return (level 1), i.e. 'passive action', and then progress to a community where programmes are run by community members with financial and technical assistance (level 5), i.e. 'independent action'. These community participation levels are a general description and do not have specific items or descriptors for observations. Occupational therapists need a comprehensive assessment of the level of a collective's participation in occupation. In addition, a scale with specific descriptors for each level on the scale, needs to be developed. This scale should also be based on a theoretical framework which speaks to the fundamental concepts of occupational science and occupational therapy.

This article reports on selected sections of a doctoral research study that aimed to develop and validate domains, items, and descriptors for levels of collective participation in occupations.

METHODOLOGY

Research design

A mixed methods approach with a sequential exploratory design21 was used for the larger doctoral study. Phase 1 of the research was the 'conceptualisation phase' where the construct of collective participation was explored. The findings from the conceptualisation phase were used in the second phase which was the 'operationalisation phase'. The development of the domains and items in phase 2 and 3 of the study were guided by a process suggested by Hudak, Amadio and Bombardier2 namely: domain and item generation, item reduction and validation of items. In this phase, domains and items were generated and framed by the VdTMoCA19. The third phase of the research validated the instrument and was reported in the original thesis 5 and is not included in this article.

Data collection procedure

In order to generate domains and items to assess collective participation in occupations, data were gathered through two sources namely: semi-structured interviews and a literature review.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were used to explore participants' perceptions of the concept of collective occupations and collective participation in occupations. Eleven participants were purposively selected to take part in the interviews. Occupational therapists who have worked in a primary health care or community setting for three or more years were invited to participate. Additionally, they had to be familiar with the concept of collective occupation and have experience in working in a community. This section of the research has already been reported in an article and the detailed information is available in Adams and Casteleijn4 .

Literature review

The second source of information was a literature review which followed the steps described by Brereton et al.23 as a guide. In Step 1, the review was planned by stating the research question and the review criteria were developed. The research question was two-fold: firstly, how is collective participation defined in the literature and secondly, what are the characteristics and nature of collective occupation from occupational therapists' point of view?

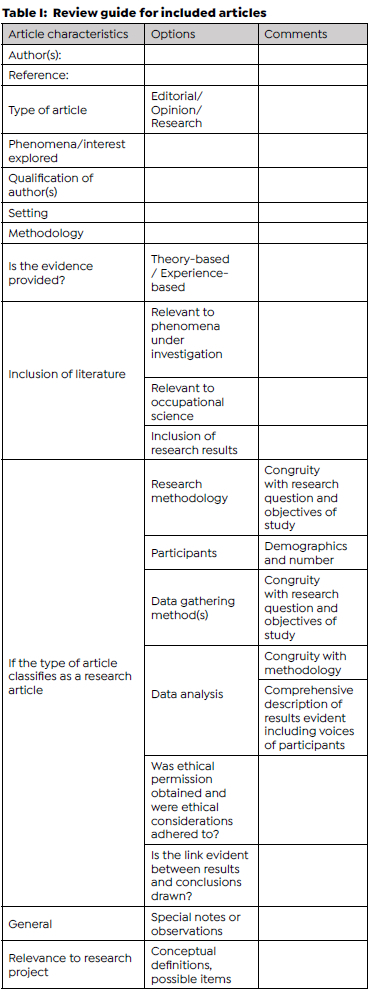

A guide for reviewing the articles consisted of demographics of the article, type of article, the methodology followed and in the case of research articles, the detail of the sample, data collection and data analysis. Lastly, a comment was included on how the article linked to the research question of our study. Table I (adjacent) presents the guide.

Step 2 was the actual searching, identifying and selection of articles following the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were that the article should have been written from an occupational science of occupational therapy perspective, collective participation should be the main focus of the article with specific reference to participation in occupations. The articles should have contained clear definitions of collective participation. Articles were excluded if the focus was on (a) critiquing individual participation in occupations and (b) reporting on collective participation without discussion characteristics of a collective from an occupational science or occupational therapy perspective.

The search strategy occurred in three rounds with Boolean terms: Round one used the search term "collective occupation*", the second search used the term "co-occupation*" and the third search combined the terms "co-occupation*" and "occupational science". The search time limit was 2006 to 2015 as the study concluded in 2015. After the articles were identified, the first author completed the review guide (Table I. adjacent) for each article. The second author cross-checked 30% of the articles, using the same review guide to ensure that the review process was accurate.

Step 3 was to extract the data to answer the research question and to document the findings. This was the analysis part of the literature review and is described below under data analysis.

Selection of domains and items for assessment of collective participation in occupations

After data were collected from the two sources: semi-structured interview and a literature review, the findings were tabulated. This information was then used to generate items for the assessment of collective participation.

Data Analysis

Semi-structured interviews were thematically analysed and findings were reported in Adams and Casteleijn4. Data analysis of the literature review comprised a description of the demographic information of the articles that were generated after the three rounds of searches. Data were extracted from the articles by identifying concepts used to define and describe the characteristics of collective participation in occupations. Descriptions of core characteristics of collective participation from the authors' perspectives were noted and described.

Possible domains and items were generated from the findings of the semi-structured interviews and literature review and then tabulated. Domains were taken from constructs in the VdTMoCA. The constructs included motivation, action, ability to handle tools, objects and materials in the environment, ability to relate to others, ability to show initiative, ability to exert effort, ability to control anxiety, ability to produce an end-product. This model was selected to frame the domains in an occupational therapy perspective since it is a commonly used model in South Africa. The authors also are of the opinion that there are a few fundamental concepts that align with actions of collective participation and should be explored. Furthermore, the model already describes levels of motivation and action in individuals and the researchers believed that the levels may also be suitable for levels of collective participation.

To reduce items, the same framework as for domains were used. Deductive content analysis was done by constantly comparing each possible item with the nine constructs suggested by du Toit. If an item fit into a construct for example, the 'ability to show initiative' fits the construct of initiative in the VdTMoCA, it was retained. If the item was similar to another item or did not fit into any of the constructs, it was deleted. When all the items were deliberated, the final set of items were allocated to domains. Domain names were selected from the VdTMoCA but adapted if the literature review and semi-structured interviews came up with a more suitable name for a domain.

Ethical clearance for the entire study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of the Witwatersrand. The ethics number is M110219.

RESULTS

Literature review findings

Initially, 82 articles were identified, but on review only five articles adhered to the search parameters. The diverse definition of the word 'occupation' was found to be problematic when searching literature due to the various interpretations of it. Two additional articles that were not identified in the initial searches were identified by a colleague. One transcribed verbal conference paper was also added. All the identified articles were reviewed in order to extract and synthesise relevant data. Table II (above) presents the eight documents that were used for data extraction.

All the articles were published in the Journal of Occupational Science between 2009 and 2015. Only one article was a research article that used narrative analysis with one case study. Five articles were opinion pieces and one guest editorial which was a summary of the articles on collective occupations and co-occupations published in 2009 (volume 3) in the Journal of Occupational Science. Due to the low number of appropriate articles, a transcribed verbal presentation on collective participation at the World Federation of Occupational Therapy Congress in Chile in 2010 was included. It was difficult to judge the quality of the papers due to the narrative and qualitative descriptions but useful information for the purpose of generating items could be extracted. The first valuable concept was how and why collective occupations or co-occupations emerged in occupational therapy. There was an unease among occupational scientists with the focus on the individual persons engaging in occupations with little attention to socio-political and social justice matters that affect occupational participation2, 28.

The term 'co-occupation' was described by many of the authors and refers to a high level of interaction of two or more people engaging in occupation. This engagement does not need to be in the same space or same time but should shape or influence those involved in the co-occupation2, 25, 26.

The term 'collective participation' was also used by many of the authors. Ramugondo and Kronenberg27 mentioned that intentionality behind the occupations needs to be acknowledged in any collective engagements. Their definition of collective participation was informative and comprehensive and explained it as "occupations that are engaged in by groups, communities and/or populations in everyday contexts, and may reflect the need for belonging, and a collective intention towards social cohesion or dysfunction" Ramugondo and Kronenberg29:12. This definition of collective participation is thus more comprehensive than co-occupations.

Both Pierce2 and Ramugondo and Kronenberg27, 29 pointed out that the intention to engage in a collective occupation may be constructive or destructive. 'Constructive collective occupations' include a group of women who run a soup kitchen for homeless people while a 'destructive collective occupation' can be groups who destroy infrastructure to voice their dissatisfaction and frustration. Other useful concepts were mentioned by Pickens and Pizur-Barnikow25 when they stated that a collective usually has shared emotionality (responds to others' emotions), intentionality (understanding each other's role and purpose) and physicality (reciprocal motor actions).

Generation of domains and items

Concepts of collective occupation that derived from the literature review were combined with the concepts derived from the semi-structured interviews4. Due to space limitations, those findings are not repeated in this article. Altogether,36 possible items were listed, 12 from the literature review and 24 from the semi-structured interviews5. These 36 items were allocated to nine domains which were taken from constructs of the VdTMoCA (Figure 1a above). The first step in the development of the assessment was thus completed.

Reduction of domains and items

The deductive content analysis eliminated 17 items and the final 19 items (Figure 2) were then allocated to five domains (Figure 1b, above). The domains are motivation, action, product, collective relations and emotive-cognitive functioning.

Reflection and discussion of domains, their accompanying items and the process

This study proposes that motivation, action, product, collective relations, and emotive-cognitive functioning (Fig 1b) be used as the basis for assessment of participation in collective occupations. These domains are familiar to occupational therapists and are common domains in assessment of individual clients and although not yet applied to collective participation, they have the potential to accurately described the actions and behaviours of collectives. This proposed domains, items and descriptors is a guide to clinicians to expand their understanding of these components in relation to collectives.

Initially, the study intended to use the nine constructs identified by du Toit as domains, however, through deductive content analysis of the data, these were reduced to five domains. By reducing the domains, the intention was to ensure that it is as practical as possible for occupational therapists to use in future. The domains and items are discussed below.

Domain 1: Motivation

Motivation is defined as biological, social, emotional and/or cognitive forces that drive, guide, initiate and maintain goal-directed behaviour 30 . It is considered to be the inner drive or internal state of a person that drives behaviour, action and initiation30. Motivation is dynamic and is dependent on the stage of human development19 .

The results of the thematic analysis of the semi-structured interviews linked the items of shared meaning and shared intentionality4 with collective motivation. Firstly, this means that a collective needs to have the intention to participate as a collective to address a problem or to achieve goals. This intention to participate acts as their motivator or drive to work collectively27 . Without a collective intention, collective motivation could be compromised. Shared meaning is one of the driving forces for shared intentionality. This means there needs to be a shared understanding of why individuals have to participate collectively in occupations.

Questions that one can explore to identify the motivation of a collective may include what drives the collective to engage in specific occupations, what is their intention that drives the behaviour? It is also important to ask what the shared meaning that the collective experience is when they are motivated to engage in certain occupations.

Domain 2: Action

Action is defined as "the exertion of mental and physical effort which results in occupational behaviour"19:7. It is a process of being active or doing something and thereby translating motivation into effort. According to the VdTMoCA, motivation drives action and action results in doing and in the case of collective action, it leads to co-creation.

Through thematic analysis and the literature review, items allocated to this domain were; co-creating, symbiotic action, equal action or symmetrical action, shared space and time, a collective's ability to take initiative, ability to exert effort and lastly, the ability to handle tools and resources . Effort is a subjective feeling of exerting one's self in activity participation31 and implies the use of energy (physical or mental) to do or produce something. A person thus exerts physical or mental effort to perform action and this also applies to a collective who need to put in effort to get things done.

Findings of step 1 of this research defined co-creation as "an active process where people in a collective create together"4:84 . This 'creating together' and the outcomes of it should be beneficial to all parties involved, it is thus symbiotic in nature which implies that the effort that is exerted by all involved, should be equal or symmetrical in nature. When linking this information to the definition of action mentioned above, it can be said that collective participation in occupations is the exertion of collective mental and physical effort which results in occupational behavior.

Within collective action, the collective should be able to take initiative thus starting and maintaining action and plans to achieve goals. Initiative is self-direction and self-application in activity participation usually in a new situation19. In laymen's terms, initiative refers to a new plan or process to accomplish a goal or solve a problem32 . In the context of a collective, initiative is related to a collective's readiness to take action and apply themselves to make the best decision in new situations. The level of the collective will determine whether they are able to take initiative or whether they are dependent on leadership for this.

Results from the literature review suggest that shared physical space and time is needed for collective participation in occupations, although Pierce2 contradicts this information by saying that shared space is not essential. However, there is evidence in psychology literature that highlights the importance of a shared space and time for collective action33.

Handling of tools and resources is related to the manipulation and use tools and of resources within the community in which the collective is situated. The use of tools and resources is important for action19 . The absence of tools and materials could influence collective action negatively, however, to understand the collective participation of a specific collective one also needs to observe at how they handle tools and resources as the collective. Several questions need to be asked. For example: Are they using it for the benefit of the collective or only to the benefit of some individuals in the collective? Are they using tools for the benefit of the collective or more for the benefit of achieving outcomes related to all in the community? Additionally, are they only using the tools and resources within the collective or are they also using available tools and resources outside of the collective?

Domain 3: Product

A product is something that is made or achieved by humans, or produced through an industrial process, or something that is grown through a natural process32 . It is the outcome or consequence of action and effort. The product can be tangible or intangible. Within a collective the product should be related to their purpose (what they wanted to achieve) and their collective formation. The product of the collective is related to their vision and goals, meaning the collective action they participated in is aimed at achieving their vision and goals.

Forming of a collective can be a product, but also an end result of a process (the process of collective formation). The mere formation of a collective could be a product if it is related to their goals. For example, women with disability forming a support group. The collective's intention was to start a group where women with disabilities could support each other. Thus, collective formation was part of this intention and vision. How and why the collective formed as well as how involved external facilitators and /or community leaders were in this process, could enhance understanding of collective participation.

Domain 4: Collective relations

This domain focusses on relations or associations between members in the collective. It includes how the collective relates to other collectives in their community. For example, how a collective liaises with other collectives to achieve objectives or gain information. The items of this domain all emerged from the thematic analysis of the semi-structured interviews which were interaction, cohesion, communication, mutual responsibility and mutual accountability 4.

Interaction is mutual or reciprocal participation. Meaning that members in the collective need to respond to each other's communication and/or actions. This response is reciprocal in nature and not only one person acting and communicating. It is similar to the symmetrical co-creation that was described earlier. Without the interaction there is no collective participation. This needs to be an active process as people need to respond to each other. Preferably, there needs to be mutual benefit and the relationship needs to be symbiotic. Interaction also needs to be part of the values of the collective and needs to occur continuously for a collective to be successful. Initially this might be leadership driven but as a collective develops and their cohesiveness is established, members should be more comfortable interacting without the intervention of the leader34.

Cohesion was described by participants in the semi-structured interviews as a connection that is crucial for collective participation4. The level of cohesion within a collective will enhance elements of effort, action, motivation, and relations, to name a few. Cohesion is depended on members connecting with others, mutual vulnerabilities and needs that facilitates a need to connect and working together. There is a link between connecting with another (cohesion) and co-creating. Successful participation in a collective and co-creating can increase cohesion in a collective positively. Similarly, cohesion can make it easier for members of a collective to co-create or participate collectively.

Mutual accountability is where members of a collective consider themselves to be answerable to each other in the collective. This could be a personal value of the individuals in a collective but can also be part of a collective's norms and values. For mutual accountability to be successful, members in the collective need to accept responsibility (mutual responsibility) and account for their part. As a collective, they also must be accountable for the actions and results of their collective actions. Additionally, individual members and the collective as a whole must accept the obligation and duty to contribute to the achievement of the goals for the collective itself or for the collective's community4 .

Lastly, communication, which is defined as the exchange of thoughts and ideas is important for collective participation as without this interaction, cohesion and co-creating is not possible. The act of communicating includes not only verbal and non-verbal communication skills but listening skills as well4 . Again, dependency on leadership needs to be explored here. The following questions need to be answered: Can the collective communicate appropriately without guidance of a leader? Do they all communicate with each other or is communication more between members and the leader of the collective? Are there dominant members that do all the talking?

Domain 5: Emotive-cognitive functioning

This domain focusses on how the collective handles situations on an emotional level for example, handling of anxiety and conflict as well as their collective problem-solving and decision-making abilities. The balance between cognitive and emotive abilities could provide insight into the collective functioning. For example, can a collective control their emotions and affect to the benefit of collective decision-making and problem solving?

Additionally, participants suggested that openness of a collective to new members, situations and ideas also need to be explored. It was felt that the more confident and cohesive a group is, the more open they will be. Insecurities within collectives could influence this negatively4. This is similar to the VdTMoCA that suggests handling of situations and anxiety as important to consider when assessing individual clients19 . Additionally, participants in the semi-structured interviews suggested that exploration of how collectives handle conflict situations, problem solving, and decision making should be considered when assessing collective participation4.

Questions that need to be explored here are: Is the collective aware of the need for decision making, problem-solving and conflict management? Can they do this as a collective or is it driven by the leader or dominant members. The five domains with its allocated items should not be viewed as separate constructs. From the discussion above, it is clear that different items influence each other across domains. One should thus be mindful of interactions between items and this will differ from collective to collective.

When comparing the suggested domains and items from this study to other measuring tools for collectives, there are some similarities. For example, the Group Climate Questionnaire is a self-report tool that aims to measure individual group member's opinions of the group's therapeutic environment35. Although it focusses on the individual point of view, it does include engagement and conflict management as domains and items for evaluation, which has similarities to this study. Similarly, the Curative Climate Instrument is also a self-report measurement that measures the helpfulness of therapeutic factors36 utilised in group therapy. This measurement tool focusses on the individual perspective, however it does include cohesion, and group belonging as part of the items, which is similar to this study.

This article does not present the observable actions for each item due to space. Adams5 describes observable actions for each item on the levels of creative ability from self-differentiation to contribution level which can be viewed in the original PhD thesis5.

Implications of the research

This research holds numerous benefits for occupational therapists working with collectives. Occupational therapists are familiar with and often work with therapeutic groups that are formed by clinicians to achieve common aims amongst individuals13 , 34, however, we are less familiar with groups as collectives in communities. These therapeutic groups often focus on individual clients and not on the achievement of collective goals. This research suggests naturally formed groups (formed by the members for achievement of collective and individual outcomes), that are more focused on the collective than on the individual are becoming a familiar intervention strategy in occupational therapy4.

Occupational therapists working in community-based settings, often work with groups within communities who choose to or are forced to participate in collective occupations to enhance the health and wellbeing of the group or community. To achieve this, occupational therapists do not only have to understand the nature of collective participation but also need to understand why people participate in them, and understand what abilities are needed to effectively participate as a collective. Understanding of a collective's motivation, ability to perform action, ability to form a collective, ability to produce and end product, emotional-cognitive functioning and collective relations could guide occupational therapists in planning intervention to facilitate collective participation in occupations.

The formulation of five descriptors for levels of collective participation according to the identified domains and 19 items allows clinicians to determine the current level of functioning of a collective on seven levels. Using VdTMoCA guidelines can then be used for planning community intervention.

Now that the descriptors of levels for collective participation have been developed, field testing by clinicians needs to take place. Additionally, further exploration of how these domains and items will be assessed in practice, is needed.

Limitations of the study

The literature review could have followed the steps of a scoping review but at the time of the planning of the study an adapted systematic review was selected before we had knowledge of which types of studies would have been found. The time frame for publications for the literature review fell in the time when the PhD study was done. Several publications after 2015 about collective occupations were published which could have been included. It is recommended that an updated scoping review should be completed to update the findings and for consideration for inclusion in the assessment tool.

CONCLUSION

Through this research project domains and items for the understanding of collective participation were developed. Five domains namely motivation, action, relations, product and emotional-cognitive functioning were developed. Collectively the domains have 19 associated items. The VdTMoCA was used to guide the development of domains and items.

This study brings together occupational therapy epistemology and African philosophy. The understanding that humans find purpose in communicating with their fellow man19, and are inextricably connected with each other27 should shift our focus from individual to collective participation in occupations. Collective participation is a common occurrence in South Africa. It is a dynamic process that sees symbiotic interaction between individuals and groups of individuals. The mutual vulnerabilities, visions, benefits, and accountability within collectives create a change agent that could surpasses the effectiveness of individuality.

A healthy collective holds the potential to benefit individual within the group as well as the collective as a whole. Understanding a collective is the bedrock of effective intervention to address and solve many of the problems affecting the health of all South Africans. This study developed domains and items that can be used to understand a collective's participation in occupations. This would enable occupational therapists to harness the power of collectives.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests to declare

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: Fasloen Adams and Daleen Casteleijn. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Fasloen Adams and Daleen Casteleijn. Final approval of the version to be published: Fasloen Adams and Daleen Casteleijn. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: Fasloen Adams and Daleen Casteleijn.

REFERENCES

1. Pierce D, Marshall A. Staging the play: Maternal management of home space and time to acilitate infant/ todller play and development. In: Esdaile S, Olson J, editors. Mothering occupations: Challenge, agency and participation. Philadephia: F A Davis; 2004. p. 73-94. [ Links ]

2. Pierce D. Co-occupation: The challenges of defining concepts original to occupational Science. Journal. 2009;16(3):203-7 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686663. [ Links ]

3. Hagedorn R. Tools for Practice in Occupational Therapy: A Structured Approach to Core Skills and Processes. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [ Links ]

4. Adams F, Casteleijn D. New insights into collective participation: A South African perspective. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;44(1):81-7. [ Links ]

5. Adams F. Development of descriptors for domains and items for collective participation in occupations. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Witwatersrand; 2016. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10539/21262 [ Links ]

6. Letts L. Health promotion. In: Blesedell Crepeau E, Cohn C, Boyt-Schell B, editors. Willard and Spackman's Occupational Therapy. 11th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. p. 165-80. [ Links ]

7. African National Congress. A national health plan for South Africa. Pretoria; 1994. [ Links ]

8. WHO. Declaration of Alma Ata. Alma Ata, USSR1978. [ Links ]

9. Iwama M. Culturally relevant occupational therapy. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006. [ Links ]

10. Dickie V, Cutchin M, Humphry R. Occupation as transactional experience: A critiques of individualism in occupational science. Journal. 2006;13(1):83-93 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2006.9686573. [ Links ]

11. Cutchin M, Aldrich R, Bailliard A, Coppola S. Action theories of occupational science: The contributions of Dewey and Bourdieu. Journal. 2008;15(3):157-65 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686625. [ Links ]

12. Fisher AG, Marterella A. Powerful Practice: A Model for Authentic Occupational Therapy. Fort Collins, CO: Center for Innovative OT Solutions; 2019. [ Links ]

13. Becker L, Duncan M. Thinking about groups. In: Becker L, editor. Working with groups. Cape Town: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 31-51. [ Links ]

14. Hemphill BJ, Urish CK. Assessments in Occupational Therapy Mental Health: An Integrative Approach. New York: Slack, Incorporated; 2020. [ Links ]

15. Rifkin SB. Paradigm Lost: Towards a new understanding of community participation in health programmes. Acta Trop. 1996;61:79-92. [ Links ]

16. Fogelberg D, Frauwirth S. A complexity science approach to occupation: Moving beyond the individual. Journal. 2010;17(3):131-9 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2010.9686687. [ Links ]

17. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process. Journal. 2020;74(7412410010) https://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001. [ Links ]

18. Casteleijn D. Using measurement principles to confirm the levels of creative ability as described in the Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;44(1):14-9. [ Links ]

19. Du Toit V. Patient Volition and Action in Occupational Therapy. Johannesburg: Vona & Marie du Toit Foundation; 2009. [ Links ]

20. Thomas M, Thomas MJ. Manual for CBR planners. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal. 2003:1-88. [ Links ]

21. Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Smith KC. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences2011. 541-5 p. [ Links ]

22. Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand). Journal. 1996;29(6):206-8 https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [ Links ] .

23. Brereton P, Kitchenham BA, Budgen D, Turner M, Khalil M. Lessons from applying the systematic literature review process within the software engineering domain. Journal. 2007;80(4):571-83 https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.009. [ Links ]

24. Pickens ND, Pizur-Barnekow K. Guest editorial. Journal of Occupational Science. 2009;16(3):138-9. [ Links ]

25. Pickens ND, Pizur-Barnekow K. Co-occupation: Extending the dialogue. Journal. 2009;16(3):151-6 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686656. [ Links ]

26. Price P, Stephenson SM. Learning to promote occupational development through co-occupation. Journal. 2009;16(3):180-6 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686660. [ Links ]

27. Ramugondo E, Kronenberg F. Explaining collective occupations from a human relations perspective: Bridging the individual-collective dichotomy. Journal. 2015;22(1):3-16 https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.781920. [ Links ]

28. Laliberte Rudman D. Enacting the critical potential of occupational science: Problematizing the 'individualizing of occupation'. Journal. 2013;20(4):298-313 https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.803434. [ Links ]

29. Ramugondo E, Kronenberg F. Collective occupations: A vehicle for building and maintaining work relationships 15th World Congress fo the World Federation of Occupational Therapists; Santiago, Chile2010. [ Links ]

30. Furnham A. Motivation. In: Comer R, Gould E, Furnham A, editors. Psychology. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013. p. 375-405. [ Links ]

31. Sherwood W. An investigation into the theorectical construction of effort and maximum effort as a contribution to the theory of creative ability. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand; 2016. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10539/21261 [ Links ]

32. Cambridge Dictionary. Online dictionary: Cambridge University Press; 2020 [13 October 2020]. Available from: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/initiative. [ Links ]

33. Barlow J, Dennis A. Not as smart as we think: A study of collective intelligence in virtual groups 2014 [Available from: jordanbarlow.flles.wordpress.com/2014/05/barlow-dennis-2014-ci-abstract.pdf. [ Links ]

34. Howe C, Schwartzberg S. A functional approach to group work in occupational therapy. . 3rd ed. Philadephia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [ Links ]

35. Johnson J, Pulsipher D, Ferrin S, Burlingame G, Davies D, Gleave R. Measuring group processes: A comparison of the GCQ and CCI. Journal. 2006;10(2):136-45 https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.10.2.136. [ Links ]

36. Yalom I. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books; 1995. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Daleen Casteleijn

Daleencastleijn61@gmail.com

Received: January 2021

Reviewed: May 2022

Revised: June 2022

Accepted: Nov 2022

Published: August 2023

Editor: Blanche Pretorius: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3543-0743

Funding: No funding was received for this research.