Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.53 no.1 Pretoria abr. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2023/vol53n1a8

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Support, supervision, and job satisfaction: Promising directions for preventing burnout in South African community service occupational therapists

Nadia StruwigI, II; Kirsty van StormbroekII

IRita Henn and Partners Inc., South Africa. Nadia Struwig: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3561-4702

IIDepartment of Occupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa. Kirsty van Stormbroek: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4890-5063

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Community service occupational therapists may be especially vulnerable to experiencing burnout. This study sought to determine the levels of burnout experienced by this population and to investigate the relationship between reported burnout and various contextual, personal, and demographic factors

METHODS: A quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional survey design was used. The online questionnaire included contextual information of the participants and the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Data were analysed using Statistica 13.5. The effect of contextual, personal and demographic variables on burnout was tested using Kruskal-Wallis tests

RESULTS: All community service occupational therapists were invited to participate in the study. A response rate of 31.92% was achieved (n=75). High levels of emotional exhaustion were reported by 55% (n=41) of participants. 'Strong' and 'adequate' support systems were associated to a greater sense of personal accomplishment (p=0.02) and 'minimal' social support was associated to increased emotional exhaustion (p=0.01). Dissatisfaction with supervision was associated to increased emotional exhaustion (p=0.017). Job satisfaction was associated to a greater sense of personal accomplishment (p=0.0002). Job dissatisfaction was associated to depersonalisation (p=0.047) and emotional exhaustion (p=0.006

CONCLUSION: Support systems, supervision and job satisfaction showed significant association to burnout. Interventions to address these factors, and research that further investigates the impact of contextual factors on burnout is recommended. This is imperative if South African occupational therapy is to take seriously its responsibility to the therapists responsible for taking services to populations with the greatest health needs

Implications for practice

• Opportunities for occupational therapists to develop professional resilience to prevent burnout should be offered across the lifelong learning continuum.

• Strengthening supervision capacity and implementing mentoring and supervision strategies that provide mutual reward for both parties are needed.

• The responsibility for promoting the vitality and job satisfaction of COSTs should be taken seriously by the Department of Health as CSOTs continue the vital work of taking rehabilitation to South Africa's populations with the greatest health needs.

Keywords: Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey, contextual factors, job satisfaction, personal factors, demographic factors

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing concern around the experience of burnout amongst occupational therapists in South Africa and particularly among community service occupational therapists (CSOTs)1. These therapists are tasked with extending occupational therapy access to populations in under-served areas and to those with the greatest health needs2, while undertaking the challenging3 transition from university to practice.

Compulsory community service (CS) was legislated two decades ago to increase access to services for rural and underserved populations2. Its implementation has had a positive effect on primary healthcare (PHC) in South Africa, increasing the number of occupational therapists in the public sector by approximately 33%4. Despite this increase, the number of occupational therapists working in the public sector remains low5. Of the 5180 occupational therapists registered with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) in 2018, only 25.2% (n=1320) worked in the public sector, serving 84% of the South African population5. Around 17.8% (n=235) of occupational therapists working in the public sector were CSOTs6. This means that CSOTs share a substantial part of the responsibility of providing occupational therapy services to rural and remote populations, populations with the greatest healthcare needs2, 7.

A proportion of CSOTs (44.7% in 20133) are placed in rural settings and the health professions minimum standards exit level outcomes for occupational therapists states that qualified occupational therapists should provide services in various settings and environments8. However, rural fieldwork placements are not included in all undergraduate occupational therapy degree curricula. A CS placement may thus be the first exposure to rural areas for the newly qualified occupational therapist3. An unfamiliar rural placement, together with having to relocate, could augment the challenges of transitioning from student to therapist9.

The CSOTs who work in rural areas and on the PHC platform have limited access to physical resources such as specialised occupational therapy equipment, appropriate therapy areas to see clients in, and no specific occupational therapy budget allocation. A long turnover time to receive ordered equipment also poses a problem to access of physical resources3, 10. Some CSOTs may also have a lack of professional resources including understaffing, minimal access to continuing professional development (CPD) opportunities, and a deficit in networking opportunities3,10. Access to supervision and mentorship is often limited along with restricted opportunity to observe other occupational therapists treating and interacting with clients 3,10 which may be due to a lack of staffing in the PHC system. Research has suggested that access to these resources is important to provide support in the transition from being a new graduate to a novice therapist 11.

Many CSOTs often work with clients that do not speak the same language as they do and clients often come from different cultural and religious backgrounds, which makes delivery of accessible and appropriate services a challenge3, 10. Often CSOTs treat clients with complex health disorders and at times struggle to manage emotionally stressful interactions with clients and their families12 which may contribute to work stress and burnout12, 13.

In responding to the aforementioned challenges, many CSOTs have reported frustration around limited or absent budgets, inadequate resources14, difficulties communicating with clients, unethical behaviours from personnel, and limited learning opportunities14. Feelings of being 'alone' have been reported by CSOTs who have had few colleagues, have faced difficult interpersonal relations with colleagues, or have lacked guidance and instruction in the workplace14. 'Anxiety' has been reported by CSOTs which was mostly attributed to insecurity about applying professional skills in the workplace and having substantial workloads14. The latter also contributing feeling 'overwhelmed'14. Feelings of being 'overwhelmed' and 'anxious' are symptoms of stress15 and CSOTs who are exposed to uncontrolled stress in the workplace over a long period may experience burnout16.

If burnout is prevalent amongst CSOTs, it is necessary to determine what intrinsic and extrinsic factors are associated with this experience in order for prevention and remediation strategies to be explored1. The authors therefore aimed to establish the nature of the relationship between burnout experienced by Community Service occupational therapists in South Africa and the coping strategies that they utilise. However, a limited association was observed when the three constructs of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment) were correlated with forms of coping (task-oriented coping, emotional-oriented coping and avoidance-oriented coping17)1. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to describe the prevalence of burnout in CSOTs and to determine the relationship between burnout and various personal, education, and work demographic factors.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Understanding burnout

Burnout was first described in the 1970s by Herbert Freud-enberger, an American psychologist, to report the consequence of extreme stress experienced by people working in helping professions. Individuals who were burned out lacked energy and could not cope with work demands18. Burnout was added to the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) in 2019 where it is defined as:

"... a syndrome... resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterised by three dimensions: feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one's job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job; and reduced professional efficacy. Burn-out refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life16 1st paragraph."

Typical symptoms in burnout are, emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who do 'people work' of some kind 19 p. 3. In occupations where individuals work with people, emotional exhaustion is the most common and is characterised by severe tiredness when an individuals' emotional resources are exhausted, which leads to feelings of being overwhelmed and lack of contribution to work on a psychological level20. Depersonalisation refers to feelings of being emotionally detached from the person being treated and depicts cynicism and decreased empathy20. Reduced personal accomplishment involves feelings of inadequacy and decreased accomplishment in an individual's profession and may mean that the individual is not satisfied with achievements at the workplace. Thus, the individual may have a decreased work rate, decreased self-confidence and may struggle to cope in the work place20. Burnout may have several detrimental effects on places of work if not addressed appropriately. These effects include high work turnover, absenteeism and decreased commitment of employees21 which impacts on the quality of care delivered. Therefore, the prevention and mitigation of burnout are especially important in both healthcare and social services22.

Burnout in health professionals and occupational therapists

Burnout can be related to factors such as expanding workloads and impractical requests from clients, families, and employers23. Occupational therapists are at risk of burnout as they display empathy and encourage participation in daily life of their clients by using themselves as therapeutic agents and using a client centred approach23. Additionally, occupational therapists often have emotionally stressful interactions with clients and their significant others which may contribute to burnout23. Their role requires compassion, commitment, selflessness, constant optimism and therapists are required to manage their emotional capacity for client interactions, work duties and their personal lives24. These factors all create a vulnerability to burnout13. Occupational therapists who experience burnout usually report emotional exhaustion and cynicism which may also have negative effects on client care25.

In a 2020 study, occupational therapists in Texas were found to have greater levels of job satisfaction and lower levels of burnout as compared to other healthcare workers such as nurses. This was attributed to strict qualification criteria, and experience in different areas of practice with different populations, making occupational therapists an adaptable workforce, lessening feelings of frustration and despair in the workplace which may protect against burnout26.

Similarly, a 2021 study found that Greek occupational therapists who were found to be more resilient (resilience measured using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale) had a greater sense of personal accomplishment and lower risk for experiencing burnout. Participants with less resilience were at greater risk for experiencing burnout27. Therefore, it is important for occupational therapy clinicians, educators, and students, to develop self-knowledge and an ability to identify their own risk of burnout. Additionally, they need to develop resilience and skills to prevent burnout and occupational stress 28.

South African occupational therapists and burnout

A shortage of occupational therapists in South Africa exists, with 0.9 occupational therapists for every 10 000 people residing in South Africa5. Due to the shortage, South African occupational therapists could face greater work stressors. Despite anecdotal reports of high levels of burnout in this population, the literature on burnout in South African occupational therapists is limited. A single study investigating the prevalence of burnout in therapists (including occupational therapists) in physical rehabilitation units in the South African private sector, highlighted that inadequate dealing with stress strongly influenced emotional exhaustion, and that the standard of physical rehabilitation is affected by the support the therapists receive and how satisfied they are in their positions at work29. No published studies could be found that examined burnout in occupational therapists working within the South African PHC system.

The need to investigate burnout in the CSOT population

While there are studies on burnout in new graduate occupational therapists internationally, no study exploring burnout in South African CSOTs specifically could be found in the literature. Thus, it is uncertain if patterns of burnout reported in newly graduated therapists in other countries30 are similar or different to that found in the South African CSOT population. While it has been suggested that the experience of burnout of CSOTs may be intensified by contextual challenges in the South African healthcare system, this has not been scientifically studied

It is imperative that stakeholders (CSOTs, CSOTs' employers and the occupational therapy profession as a whole) understand CSOTs' the experiences of burnout and that this is addressed appropriately. Addressing the causes of high burnout rates may contribute towards developing an insightful, resourceful and resilient CSOT workforce. This research is thus positioned to describe burnout in CSOTs and investigating the relationship between burnout and relevant contextual, education and demographic factors.

METHOD

Study design

A quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional survey design was employed. Inductive content analysis31 was used to analyse extensive comments made by participants to justify their survey responses.

Study population

The 2019 CSOT population under study consisted of 235 therapists6.

Sampling and sample size

Non-probability sampling was used as the details of each member of the population were not available to enable a random sampling approach32. All 2019 CSOTs were invited to participate via professional organisations (OTASA, and Rural Rehabilitation South Africa) and social media platforms (Facebook, WhatsApp groups). Participants were requested to forward the invitation to other CSOTs, thus a measure of snowball sampling33 was also employed.

With a population of 235 a sample size of 147 was required to achieve a 5% margin of error, 95% confidence interval, and 50% response distribution34. This required a 58% response rate.

Instrumentation and outcome measures

The online survey had two sections: demographic information of the participants and the Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Demographic factors were included in the questionnaire where literature suggested them to be significant to the experience of CSOTs3. The demographic information included personal demographics, and questions regarding CSOTs' education (education demographics) and work experience (work demographics). The latter component was developed from the literature that identified various factors which posed as stressors to novice therapists10, 11, 35 and suggested that prolonged exposure to these kinds of stressors may lead to burnout in initial employment30. Data were also collected on the number of patients seen, number of sites where they provided services, information regarding staffing levels and the nature and quality of supervision received. Other information included communication challenges with clients, understanding of clients' values, beliefs, attitudes and culture, and job satisfaction as a CSOT. Comment sections and scales were included to add to the richness of data and to allow participants to explain their answers.

Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS)

The MBI-HSS used for this study, is the first version of the MBI and is most commonly used. It aims to determine how individuals working in helping professions experience burnout in relation to their profession and people who they come into contact with at work36. The three constructs that the MBI-HSS measures are emotional exhaustion, deper-sonalisation and personal accomplishment. The emotional exhaustion scale, consisting of nine items, measures participants' feelings of emotional exhaustion at work with high scores indicating high levels of perceived burnout37. The depersonalisation scale, consisting of five items, measures uncaring or indifferent responses to clients of participants, with greater scores indicating high amounts of perceived burnout37. The personal accomplishment scale, consisting of eight items measures feelings of capability and success when participants work with their clients. Low personal accomplishment scores indicate higher perceived burnout37.

Internal reliability for the MBI was determined by using data from early samples by using Cronbach's coefficient alpha38, which showed approximate values of the three burnout constructs. Internal consistency for reliability coefficients for each component of burnout was shown over various samples in research done by the developers of the MBI37. In terms of validity, scores for the different constructs of burnout have been correlated with impressions of others37.

How burnout was measured in the study Conflicting ideas of what constitutes low, moderate or high levels of burnout exist in the literature, challenging the interpretation of results in this study. Cut-off scores for measures are believed to show borders between norms and different clinical ranges39 but various studies report difficulty in establishing low, moderate and high cut-offs with the MBI-HSS40. Maslach and Leiter advise that burnout be viewed on a continuum rather than as a concrete diagnosis. They caution against using set cut-offs for the MBI and have removed them in the latest MBI manual as cut-offs were believed to have no diagnostic validity37. These authors have developed burnout profiles by determining trends of the burnout experience41, but these profiles could not be used as they have yet to be validated.

Previous burnout studies involving healthcare professionals have not been overt in reporting cut offs for the three dimensions of burnout. A systematic review of 50 articles focusing on the classification and diagnosis of burnout in doctors and nurses found discrepancies between studies when defining burnout and providing cut-offs for low, moderate and high levels of the three components of burnout40. Some studies were found to be too conservative, under-reporting burnout rates by strictly reporting burnout when high levels existed for all three burnout components40.

The cut-offs chosen for this research were specifically taken from a study done with occupational and physiotherapists by Balogun et al42. This ensured that the experiences of burnout of the participants would not be under-captured by making use of conservative cut-offs. A high score for emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation and a low score for personal accomplishment indicate high burnout. Emotional exhaustion scores above 27 is high, between 17-26 is moderate and below 16 is low. Depersonalisation scores above 13 is high, between 7-12 is moderate, and below 6 is low. Personal accomplishment scores above 39 is high, between 32-38 is moderate, and 31 and below is low42.

Permission to use the MBI-HSS was granted by MindGarden prior to data collection43. Frequency of the participants' burnout was recorded, and cut-offs were used to capture whether the participants were indeed experiencing high, moderate or low levels of burnout. Implications of using these cut-offs could be under or over-reporting of the experience of burnout in the participants. Ongoing ambiguity around interpreting MBI-HSS scores shows a need for further research.

Research procedure

Ethical Considerations

Completion of survey questionnaire constituted consent to participate. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand HREC number: M180719.

Data collection

Completion of the MBI-HSS and demographic questionnaire took approximately 20 minutes. Data were collected between July 2019 and January 2020, allowing for participants to have experienced at least 6 months of clinical work in the Community Service system. Reminders were sent via OTASA and social media during the data collection period. Data were collected and managed using REDCap, an electronic data capture tool hosted by the University of the Witwatersrand44. Data were downloaded to Microsoft Excel, cleaned and coded in preparation for analysis. Due to responses being anonymous, potential duplicate responses could not be eliminated from the data set to avoid cross posting.

Data analysis

Questionnaires with missing data were discarded45, therefore only 75 questionnaires could be analysed. This reduced response rate falls within the 10% margin of error accepted for small samples46.

Data were analysed using STATISTICA version 13.547. Frequencies and percentages were used to report the personal, educational, and work demographic information of the CSOT participants. Non-parametric statistics were used to analyse the MBHSS ordinal data. However, parametric means and standard deviations were used to present the different types of data from the MBI-HSS. Medians and quartile ranges, as well as means and standard deviations were used to report the experience of burnout of the participants. Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests (ANOVA by Ranks) tests48, were used to report the effect of personal, educational and work demographic variables on the perception of burnout factors.

Inductive content analysis31 was used to analyse comments that participants added to justify or explain their answers in the online questionnaire. Data were coded and codes sorted into categories. The frequency of responses in each code and category were reported49.

RESULTS

A total of 105 responses were received (44.68% return rate). Ten responses were incomplete and thus discarded. A further 20 responses were deleted as the MBI-HSS aspect of the questionnaire was not completed. Seventy-five responses were therefore included in analysis, representing 31.92% of the population.

Demographic and work information

Most of the participants (97.33%; n=73) were female (2.67%; n=2 male participants) and a majority (52%; n=39) were 23 years old (age range 22-30 years). Thirty percent of participants (30.67%; n=23) worked in Gauteng. A similar percentage of participants (41.33%; n=31) reported working in rural areas during CS (48%; n=36). One third of participants (33.33%; n=25) provided services at multiple levels of care with 25.33% (n=19) of them providing services at district level. Just over half (54.67%; n=41) of the participants worked at a single service site. Participants treated a median of 80 (Range:15-400).

Social support

A strong support structure and adequate support structure was reported by 49.33% (n=37), and 36% (n=27) of participants respectively. The main source of support reported by participants were significant others (37.33%; n=28) and nuclear family (33.33%; n=25).

Supervision

Most participants (77.33%; n=58) had a supervisor (no supervisor reported by 22.67%; n=17). Most supervisors (69.33%; n=52) were occupational therapists. Dissatisfaction with supervision by the 58 participants who had a supervisor was similar (40%; n=30) to satisfaction (37.33%; n=28).

Of those reporting dissatisfaction, 56.67% (n=17) reported that this was due to supervision that was not optimal or of a good standard. One participant explained,

"No one really checks on me/watches me and guides me". (Participant 53, 24-year-old, female)

Many participants who were dissatisfied with their supervision linked this to unethical practice and poor interpersonal relations with their supervisor (50%; n=15). Two participants explained,

"The supervising therapists do not hold themselves to the [same] standard that they expect the comm serve to adhere to". (Participant 11. 23-year-old, female)

"...develops own rules but doesn't obey them" (Participant 28. 23-year-old, female)

Several participants were not satisfied with their supervision because their supervisor was not an occupational therapist or had limited knowledge in training CSOTs (30%; n=9). Others attributed their dissatisfaction to organisational problems (20%; n=6) or believed their supervisor to have insufficient administrative and leadership skills (10%; n=3).

In contrast, eight (50%) participants who were very satisfied with their supervision, attributed this to available human and non-human resources. One participant explained,

"I am gaining experience in different fields of OT, getting great supervision and have the resources available to treat". (Participant 65, 22-year-old, female)

Job Satisfaction

Just over a third of participants (34.67%; n=26) were partially satisfied with their jobs as CSOTs, with 32% (n=24) of participants reporting being satisfied. Sixteen participants (21.33%) were very satisfied with their jobs and 12% (n=9) of participants were not satisfied with their job as a CSOT.

Twenty-four participants (92.31%) reported that they were only partially satisfied with their jobs as CSOTs due to the lack of human and non-human resources. One participant explained,

"I don't feel as if I am giving a type of service that is of great value, due to having no support, no means of assistance, I'm expected to run an entire OT department seeing in and outpatients both paeds and adults. I am also expected to be accountable for the entire rehab department due to having the highest qualification, which I think is unfair to me". (Participant 13, 26-year-old, female)

Eight (30.77%) participants were partially satisfied with their jobs due to feelings of being stressed, overwhelmed and discouraged. One participant provided the following comment,

"However, I also feel that my responsibilities are substantial, which in turn places an indescribable emotional and physical stress on me. This leads me to often question my happiness with my profession". (Participant 6, 24-year-old, female)

Two participants (7.69%) linked their partial job satisfaction to contextual limitations and eight (30.77%) participants attributed their partial satisfaction to positive experiences in their job.

Of the participants that were very satisfied with their jobs (21.33%, n=16), 62.5% (n=10) reported that they were very satisfied with their job due to the positive experiences of being an occupational therapist,

"...[you] can Anally have continuity of care for the patient throughout the year which means you see progress and feel like you are truly making a difference in someone else's life." (Participant 2, 23-year-old, female)

Of the participants that were not satisfied with their jobs as CSOTs (n=9), 66.67% (n=6) reported that their dissatisfaction was due to a lack of human and non-human resources. The following participant highlighted the absence of human resources,

"I have no support as the sole OT within the remote area, it is continually challenging to communicate with other team members, the understanding of OT in the area is limited despite efforts to change." (Participant 33, 24-year-old, female)

Five participants (55.56%) linked their job dissatisfaction to emotions experienced in the workplace. One therapist described,

"I feel hopeless and useless as I am not rendering a service of good quality." (Participant 25, 23-year-old, female)

Three participants (33.33%) who were not satisfied with their jobs attributed this to client-related frustrations. One participant explained,

"I also at times feel that I struggle to And compassion and sympathy for patients that do not take responsibility for their own health and see the professional as an expert rather than a partner (and patients are often reluctant to engage in goal setting with the therapists to guide their own therapy)." (Participant 9, 23-year-old, female)

Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey

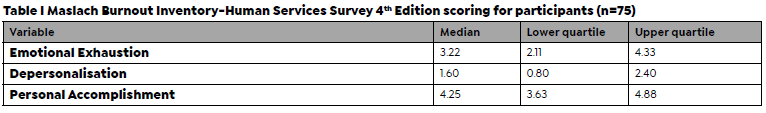

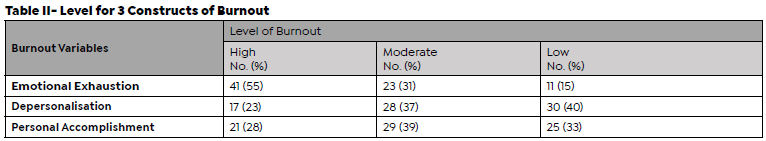

The three components of the burnout syndrome, as measured by the MBI-HSS37, are shown in Table I (page 72) and II (page 72). In Table I the mean score of 3.20, SD±1.35 indicates that most of the participants felt emotional exhaustion a few times a month, but not weekly. Table II indicates the level (low, moderate and high levels classified by Balogun et al.42) of burnout participants experienced with 55% (n=41) reporting high levels of emotional exhaustion at the time of data collection.

The mean score of 1.78, SD±1.16 (Table I, 73) indicates that most participants experienced depersonalisation a few times a year or less. Table II (page 73) indicates that 23% (n=17) of the participants reported high levels of depersonalisation at the time of data collection.

Participant's mean score for personal accomplishment was 4.16, SD±0.998 (Table I, page 73) indicating that participants felt a sense of personal accomplishment at least once a week. Table II (page 73) shows that 28% (n=21) of the participants reported high levels of personal accomplishment at the time of data collection. Twenty-five (33%) participants reported low levels of personal accomplishment with lower scores.

Contextual factors affecting perception of burnout

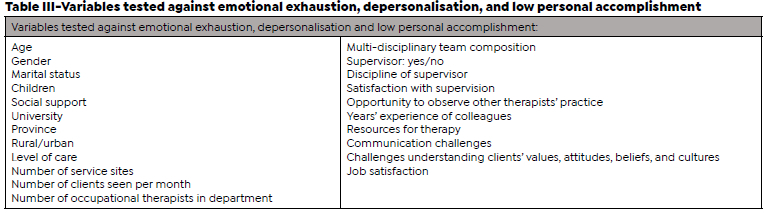

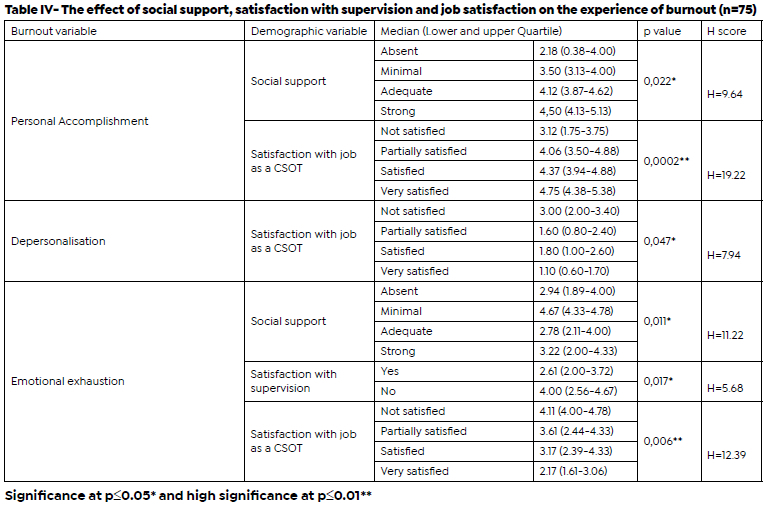

Table III (page 73) shows all the variables that were tested against emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and low personal accomplishment. Variables that demonstrated a significant relationship with burnout (p < 0.05, and p < 0.01 and lower for highly significant variables) are highlighted. Only six of the twenty-four variables tested were found to be significant and they all fell into the work demographic category of the demographic questionnaire: The participants' support systems, satisfaction with supervision and job satisfaction which had an effect on their experience of burnout is shown in Table IV (page 74).

The effect of support systems on burnout constructs

Participants with strong (median=4.5, quartile range 4.13-5.13) and adequate (median=4.12, quartile range 3.87-4.62) support systems had a greater sense of personal accomplishment. Kruskal-Wallis results for social support and a sense of personal accomplishment were H=9.64, p=0.022, with a mean rank for personal accomplishment of 14.5 for absent social support, 24.83 for minimal social support, 34.96 for adequate social support and 44.69 for strong social support.

Participants who reported minimal social support (me-dian=4.67, quartile range 4.33-4.78) reported greater levels of emotional exhaustion. Kruskal-Wallis results for social support and emotional exhaustion were H=11.22, p=0.01, with a mean rank of 60.28 for minimal social support.

The effect of satisfaction with supervision on burnout constructs

Participants who were not satisfied with the supervision they received (median=4.00, quartile range 2.56-4.67) reported greater levels of emotional exhaustion. Kruskal-Wallis results for satisfaction with supervision and emotional exhaustion were H=5.68, p=0.02, with a mean rank of 34.60 for not satisfied with supervision.

The effect of job satisfaction on burnout constructs

Participants who were very satisfied (median=4.75, quartile range 4.38-5.38) and satisfied (median=4.37, quartile range 3.94-4.88) with their jobs as CSOTs, had a significantly greater sense of personal accomplishment. Kruskal-Wallis results for job satisfaction and a sense of personal accomplishment were H=19.22, p=0.0002, with a mean rank for personal accomplishment of 14.11 for not satisfied with job, 34.98 for partially satisfied, 40.21 for satisfied with job and 53.03 for very satisfied with job.

Participants who were not satisfied with their CS job (median=3.00, quartile range 2.00-3.40) reported a greater sense of depersonalisation. Kruskal-Wallis results for job satisfaction and depersonalisation, were H=7.94, p=0.05, with a mean rank of 51.89 for not satisfied.

Lastly, participants who were not satisfied with their jobs as CSOTs (median=4.11, quartile range 4.00-4.78) experienced greater levels of emotional exhaustion with a highly significant value. Kruskal-Wallis results for job satisfaction with and emotional exhaustion were H=12.39, p=0.006, with a mean rank of 53.39 for not satisfied with job.

DISCUSSION

Burnout experienced by the participants

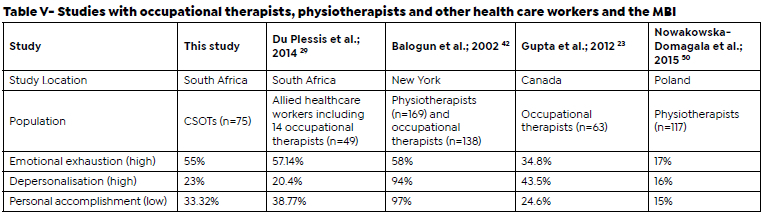

Notwithstanding the challenges around interpretation of MBI-HSS scores, emotional exhaustion was common amongst participants (55%) with smaller, though sizable, groups reporting reduced personal accomplishment (33%) and depersonalisation (23%). These results are similar to levels reported by South African therapists working in private rehabilitation facilities (57,14 %, 38,77% and 20,40% reported for the three components respectively)29. Research done with therapists using the MBI as a measure for burnout is shown in Table V (page 75). The results measured for burnout differ for each country. Results for the Balogun et al 42 study in 2002 is the only result which demonstrates similar results for the emotional exhaustion experienced by South African allied health professionals (55%). Healthcare workers in South Africa face unique contextual stressors which the participants in the studies in the table may not necessarily face, and therefore the results vary greatly.

A well-established link between exhaustion and deper-sonalisation exists in the research as withdrawal is a reaction to exhaustion51. Results may indicate that 77% of the participants did not allow emotional exhaustion to affect their interactions with clients as depersonalisation is usually the phase of burnout that follows after emotional exhaustion52. Low levels of depersonalisation for the participants may be due to this being their first year of practice, and further time in the profession could yield greater levels of depersonalisation, which could be an interesting topic for research with participants who have more than one year's experience.

Hospital and governmental rules may decrease the ability to make independent decisions at work when it comes to time spent in client care, which may increase burnout53. Working with low-income populations in healthcare with no power to address the origins of medical concerns may also result in burnout53. Studies done with nurses report stressors at work caused by decreased access to resources including uncooperative and demotivated work colleagues, equipment unavailability, understaffing, poor supervision and support, insufficient salaries, and poor recognition of work53. These contextual factors are also present in the South African context with CSOTs in this study reporting similar experiences.

Burnout influences quality of life, client care, places strain on the economy, and healthcare workers with burnout have been reported to have elevated suicide rates54. Long-term effects of burnout have also been described in the literature. Burnt-out employees may influence their colleagues through negative interactions, and burnout is often connected to dissatisfaction and work withdrawal, poor job commitment, absentia and great rates of employee replacement55. This effects employee wellness and performance which influences client management and satisfaction within healthcare negatively53, 55. The effects of burnout on individuals shows the importance of identification, intervention and prevention of burnout at work54. In the CSOT population the effects of burnout could make the employee question their role in the profession, and seek to provide services in areas which pose less contextual stressors and are not under-served, reinforcing the unfair distribution of occupational therapy services1.

Approaches for the treatment and prevention of burnout mainly focus on the use of coping mechanisms, fostering resilience, improving the work environment and independence in the work place56. These approaches mostly target the clinician, but the employer, tertiary institutions and professional organisations should also play a role in promoting the use of strategies to prevent burnout in the workplace1. Burnout intervention can be divided into person-directed and organisation-directed interventions57. Person-directed interventions are beneficial in the short term (less than 6 months) and person-directed intervention in combination with organisation-directed intervention has extended effects (greater than 12 months). The effects of these interventions decrease over time which creates a need for implementing additional intervention courses57.

Support systems

The protective role of social support was a significant finding of this study. A positive relationship between social support and personal accomplishment was observed while emotional exhaustion was associated with poor support. A meta-analysis of 144 published articles demonstrated a similar relationship, however, support sources from outside of the workplace were specifically related to greater personal accomplishment. Work-related social support, however, demonstrated a negative association and was found to be closely related to emotional exhaustion58. Work related social support was not included as part of the work demographic survey questionnaire in this study so conclusions regarding whether the social support at work affected the experience of burnout of the participants could not be made. However, only two participants reported receiving their main support from colleagues at work1. The main source of support reported by participants were significant others (37.33%; n=28) and nuclear family (33.33%; n=25). The majority of the participants are in the young adulthood stage of development (18-40 years old), where support from family may shift to support from a significant other or friends59.

Satisfaction with supervision

A number of participants (20%) had no other occupational therapist in their departments or reported being the only allied health professional at their place of work (6.67%), which concurs with older research reporting that CSOTs may be left to run departments in rural practice by themselves with minimal support or supervision10. A majority of participants (77.33%) had a supervisor. In a study of the 2013 CSOT population, almost 90% of therapists reported having a supervisor3. The increased proportion of therapists without a supervisor is concerning and may be related to the 'freezing of posts' in the Department of Health resulting in fewer permanent staff being employed due to budget constraints60. Forty percent of the participants who did have a supervisor were not satisfied with the supervision they received (n=30, missing responses=17 participants who did not have a supervisor) whereas 65.9% of 2013 CSOTs reported dissatisfaction with supervision14 showing that CSOTs satisfaction with supervision has improved.

It is important to have a supervisor and enough guidance and support in the transition from being a new graduate to novice practitioner35, 61 and supervision has been associated with greater job satisfaction30. However, it is common for there to be a mismatch between supervision and expecta-tions3. Therefore, decreased satisfaction with supervision in the first year of occupational therapy practice was not surprising in the participants. Novice occupational therapists who have reported dissatisfaction with supervision have provided reasons, such as having unrealistic expectations regarding formal supervision and support 61, and inadequate supervision which does not meet the needs of the CSOT35.

Thirteen participants were satisfied with their supervision due to the frequency of supervision they received which was expected as the frequency of supervision may decrease from being a student to new practitioner and supervision efficaciousness differs over time62.

Supervisor characteristics have been connected to supervision satisfaction in previous studies. Twenty participants were satisfied with their supervision because their supervisor was skilled and knowledgeable, and 14 participants were satisfied with their supervision due to their supervisor's positive characteristics.This concurs with the literature that suggests that there is a definite link between satisfaction with supervision and supervisors skill and experience9. Positive characteristics of supervisors such as creating a supportive atmosphere which promotes a sense of freedom63 was also found to have a definite impact on the level of satisfaction of novice occupational therapists.

Participants who had a supervisor reported experiencing greater depersonalisation than those who did not have a supervisor (p=0.050) which was unexpected as literature conveys that clinical supervision of a good standard usually results in decreased depersonalisation64. Participants who had a supervisor and were not satisfied with the supervision they received reported greater levels of emotional exhaustion (p=0.017). This finding partly agrees with the literature and the expectations of the researchers. Whole studies (mostly done with the nursing population in healthcare) have been dedicated to the effect of clinical supervision on burnout with common findings being that good clinical supervision often results in decreased feelings of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation64. The question about satisfaction of supervision did not yield a significant p value for depersonalisation (p=0.308) but did yield a significant p value for emotional exhaustion (p=0.011). This suggests that having access to a supervisor is not enough, but satisfaction with supervision is key to avoid emotional exhaustion in the participants.

Job satisfaction

Participants who were satisfied or very satisfied with their jobs as CSOTs had a greater sense of personal accomplishment with a highly significant score (p=0.0002). Participants who were not satisfied with their jobs as CSOTs reported a greater sense of depersonalisation (p=0.047) and experienced greater levels of emotional exhaustion with a highly significant value (p=0.006). This is expected as individuals who experience gratification from working with clients would be thought to have a greater sense of success and competence at work. Work satisfaction may be an indicator of decreased emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation and increased sense of personal accomplishment65. It is important to note that these findings cannot simply be generalised to occupational therapists, but they are very similar to the results of this study representing CSOTs specifically.

Participants in this study who were not satisfied with their jobs as CSOTs reported unethical staff behaviour (n=7), lack of support, recognition and learning opportunities (n=3), not being confident in their own skills (n=2), stress in workplace affecting emotional and mental wellbeing (n=4), and clients who do not take responsibility for their own health (n=3). These findings were expected, as job-dissatisfaction in occupational therapy is usually related to the work environment, decreased work status and the unspecified role of occupational therapy compared to other health professionals66.

Occupational therapists report satisfaction with treating their clients and making a difference in clients' lives. The diverse nature of occupational therapy and the freedom to perform this work coincides with the feeling of satisfaction on the job66. Furthermore, the role, identity and recognition of occupational therapy as a profession, and working in an environment which provides sufficient human and non-human resources are reported to contribute to job satisfaction67. Pride in occupational therapy as a profession, proper supervision and having occupational therapy colleagues contributes to CSOTs identities. Seeing how occupation-based practice contributes to occupational therapy's role within the multi-disciplinary team further contributes to CSOTs confidence and role within the team14 and this strong occupational identity leads to job satisfaction. Therefore, these aspects should be strived toward to prevent job dissatisfaction for the CSOT population.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Burnout: prevention is better than cure

CSOTs should have access to learning opportunities that enable them to understand burnout, recognise its symptoms and develop skills that protect against or mitigate its impact. These self-awareness and self-management skills don't develop overnight and need to be supported within the lifelong learning process. This should start with undergraduate students and CSOTs developing various intrinsic strategies to deal with burnout. Learning opportunities could include resilience education and how to foster resilience in preparation for and throughout the CSOT year and developing constructive coping strategies. This training could be offered by universities, OTASA and the employer.

Occupational therapy students can learn the protective value of social support and supervision and be encouraged to develop this throughout their undergraduate and CS years. These topics could be included in the undergraduate curriculum or as part of CPD in the CS year. Learning essential 'soft skills' at an undergraduate level could foster the development of effective self-management and resilience which will assist with navigating through studies, work and life68. The World Federation of Occupational Therapists' 2016 minimum standards for education of occupational therapists also speaks to the importance of 'soft professional skills'69 which could serve as an effective way to develop occupational therapy students' insight into the value of social support and supervision.

CSOT managers should communicate with CSOTs effectively and involve them in decisions regarding client treatment which gives CSOTs a sense of control in the workplace and decreases feelings of stress and burnout. Older (non-novice) therapists should also develop insight into their own risk for burnout and develop appropriate self-management skills. Modelling these important skills for junior therapists may change the work environment and lessen the risk for experiencing burnout.

Supervision and support in the workplace

Successful opportunities for support, supervision, growth, and development need to be made available to CSOTs by putting meaningful supervision, mentoring and educational programmes into place. Some initiatives which offer mentoring and support have been started70. Additionally, programmes could be offered as a collaborative effort by the Department of Health, and RuReSA, and be informed by universities, and OTASA as voices of the occupational therapy profession in South Africa to cater for the specific needs of the CSOT population.

Opportunities for therapists to grow in support and supervision roles need to be made. Professional organisations such as OTASA and RuReSA (and potentially universities), and the employer could take a more active role in developing good supervisors by providing CPD accredited courses, mentorship programmes, and communities of practice for therapists to develop their knowledge and skill and own sense of satisfaction within supervision, support and mentorship of younger therapists. Recognition for outstanding supervisors in the profession is valuable to promote growth in support and supervision roles. Currently, RuReSA has annual awards for best practicing rural therapists and outstanding supervisors and mentors could be nominated for these awards71. Similarly, annual awards for outstanding supervisors in private and government sectors could be instituted by OTASA to outstanding supervisors.

Job satisfaction

CSOTs employers could promote the determinants of job satisfaction highlighted by participants (positive experiences, having learning and growth opportunities, available human and non-human resources, and cohesion with other staff) for CSOTs at the workplace. Support through colleagues can be facilitated by employing CSOTs in pairs or more. Additionally, CSOTs can create their own resources and develop their own resilience by learning how to extract satisfaction from their jobs when determinants for job satisfaction are not available.

CSOTs should be afforded the opportunity to discover fields of preference by being exposed to a variety of placement areas and develop knowledge and skill across multiple areas of practice. This could be done by giving CSOTs the opportunity to rotate to different institutions in one area or seeing a variety of patients in primary care by travelling to different clinics on different days.

Opportunities to learn by means of observation of other occupational therapists' practice and learning about handling techniques with clients should be included in rotations. Transport arrangements by the employer to allow CSOTs to reach urban areas to access practicing occupational therapists would be beneficial. Where real opportunities to watch other occupational therapists' practice aren't possible, virtual opportunities could be explored. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth has been approved by the WHO as an acceptable mode for occupational therapy intervention and can be used in training72. A platform like Microsoft Teams for novice therapists to watch treatment sessions done by experienced occupational therapists with all the necessary consent and privacy settings being considered could be considered.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to document the prevalence of burnout in the CSOT population 17 years after the year of CS was implemented by the National Department of Health. It has expanded on work done by van Strormbroek and Buchanan in 2014, which describes CSOTs experiences and demographic factors35 with similar findings being reported even though the sample size only represented 31.92% of the CSOT population. Because of this sample size, generalisation of the findings in this study to the whole CSOT population or to novice occupational therapists in other countries should be done with caution.

It is not known if the research questionnaire reached the whole CSOT population and only 75 complete responses were analysed for the study from a total of 105 responses. This could be due to factors such as the participants not having access to social media or technology such as a computer and smartphone with sufficient data to complete the questionnaire. Additionally, some participants could have received the invitation to participate in the survey but did not do so. These factors may have caused an under-coverage bias73 and/or a non-response bias74 which could have skewed the findings in the results.

Data collected in the form of a self-reported questionnaire could create distortion and bias due to the researcher not being able to control situational elements (such as the environmental setting where the participants filled in the questionnaire). Furthermore, the study was a cross sectional study which could create temporal bias as the study was conducted in one point in time75.

Pilot testing of the survey questionnaire was not done. This could have been a useful way to identify areas of the survey to improve to ensure a better response rate and to effectively recruit more participants76 which should be considered in future to improve the number of responses for similar studies.

CONCLUSION

High levels of emotional exhaustion, as an indicator for burnout, were common in the CSOT participants. Depersonalisa-tion and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment were less common. The relationship between these components and several personal, education and work demographic factors were tested. Significant associations with support, supervision and job satisfaction highlighted these areas as potential target areas to prevent and mitigate burnout symptoms. Roles for the South African occupational therapy profession, the Department of Health and novice clinicians themselves are described.

Acknowledgements

The Community Service occupational therapists who participated in this study are sincerely thanked for their time and valuable contribution to understanding the research topic within the South African context. Gratitude is extended to Dr Denise Franzsen for her methodological expertise

Author/s contribution

Nadia Struwig was an MSc occupational therapy postgraduate student at the time of the research (graduated in 2020). She was responsible for the conceptualization and execution of the project. She drafted the manuscript and was responsible for subsequent revisions. Kirsty van Stormbroek was the research supervisor of the project. She provided critical reviews, comments, and suggestions for revisions of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest and bias declaration

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Struwig N. The relationship between coping strategies utilised by Community Service occupational therapists and their experience of burnout [Research report]. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand; 2020. [ Links ]

2. Reid S. Compulsory Community Service for doctors in South Africa - an evaluation of the first year. South African Medical Journal. 2001;91(4):329-35. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/samj/article/view/157573. [ Links ]

3. van Stormbroek K, Buchanan H. Novice occupational therapists: Navigating complex practice contexts in South Africa. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2019. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1440-1630.12564. [ Links ]

4. Harrison D. An Overview of Health and Health care in South Africa 1994-2010: Priorities, Progress and Prospects for New Gains. In: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation 'to Help Inform the National Health Leaders' Retreat, editor. Muldersdrift2010. [ Links ]

5. Ned L, Tiwari R, Buchanan H, van Niekerk L, Sherry K, Chikte U. Changing demographic trends among South African occupational therapists: 2002 to 2018. Human Resources for Health. 2020;18. Available from: https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-020-0464-3. [ Links ]

6. De Witt P. Statement as the preseident of Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa (OTASA). 2019. [ Links ]

7. Rural Health Advocacy Project. Rural Health Fact Sheet 2015 2015 [Available from: http://rhap.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/RHAP-Rural-Health-Fact-Sheet-2015-web.pdf. [ Links ]

8. SAQA. South African Qualifications Authority: Registered Qualification: Bachelor of Science in Occupational Therapy 2020 [Available from: https://allqs.saqa.org.za/showQualification.php?id=3497. [ Links ]

9. Toal-Sullivan D. New graduates' experiences of learning to practice occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006;69(11):513-24. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/030802260606901105. [ Links ]

10. Naidoo D, van Wyk J, Waggie F. Occupational therapy graduates' reflections on their ability to cope with primary healthcare and rural practice during community service. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017;47(3):39-45. Available from: https://www.sajot.co.za/index.php/sajot/article/view/412/286. [ Links ]

11. Morley M. Contextual factors that have an impact on the transitional experience of newly qualified occupational therapists. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009;72(11):507-14. Available from: https://www.deepdyve.com/lp/sage/contextual-factors-that-have-an-impact-on-the-transitional-experience-LDd0baMwj9?key=sage. [ Links ]

12. Kautzky K, Tollman SM. A perspective on Primary Health Care in South Africa. South Africa Health Review. South Africa: Health Systems Trust; 2008. [ Links ]

13. Schlenz KC, Guthrie MR, Dudgeon B. Burnout in Occupational Therapists and Physical Therapists Working in Head Injury Rehabilitation. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1995;49(10):986-93. Available from: https://research.aota.org/ajot/article-abstract/49/10/986/3829/Burnout-in-Occupational-Therapists-and-Physical?redirectedFrom=PDF. [ Links ]

14. van Stormbroek K, Buchanan H. Community Service Occupational Therapists: thriving or just surviving? South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016;46(3):63-72. Available from: https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/30310. [ Links ]

15. Varvogli L, Darviri C. Stress management techniques: Evidence -based procedures that reduce stress and promote health. Health Science Journal. 2011;5:74-89. [ Links ]

16. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision I-. QD 85 Burnout: World Health Organization; 2020 [Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http:/id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281. [ Links ]

17. Endler NS, Parker JDA. Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations (CISS) Manual. Second ed. United States and Canada: Multi-Health Systems Inc.; 1999. [ Links ]

18. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Depression: What is burnout? 2012. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279286/. [ Links ]

19. Maslach C. Burnout: The cost of caring. NJ: Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs; 1982. [ Links ]

20. Maslach C. A Multidimensional Theory of Burnout. Cooper CL editor. Oxford: UK: Oxford University Press; 1998. [ Links ]

21. Bothma FC, Roodt G. Work-based identity and work engagement as potential antecedants of task performance and turnover intention: unravelling a complex relationship. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology. 2012;38(1):1-17. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266607108_BOTHMA_FC_ROODT_G_2012_Work-based_identity_and_work_engagement_as_potential_antecedents_of_task_performance_and_turnover_intention_Unravelling_a_complex_relationship_SA_Journal_of_Industrial_Psycholog. [ Links ]

22. Shin H, Park YM, Ying JY, Kim B, Noh H, Lee SM. Relationships Between Coping Strategies and Burnout Symptoms: A Meta-Analytic Approach. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2014;45(1):44-56. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263936204_Relationships_Between_Coping_Strategies_and_Burnout_Symptoms_A_Meta-Analytic_Approach. [ Links ]

23. Gupta S, Paterson ML, Lysaght RM, Von Zweck CM. Experiences of burnout and coping strategies utilized by occupational therapists. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012;79(2):86-95. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225271324_Experiences_of_Burnout_and_Coping_Strategies_Utilized_by_Occupational_Therapists. [ Links ]

24. Stamm BH. The concise ProQOL manual. 2nd ed. Pocatello 2010. [ Links ]

25. Escudero-Escudero A, C., Segura-Fragoso A, Cantero-Garli PA. Burnout Syndrome in Occupational Therapists in Spain: Prevalence and Risk Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(3164). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7246504/pdf/ijerph-17-03164.pdf. [ Links ]

26. Chen CC. Professional Quality of Life among Occupational Therapy Practitioners: An Exploratory Study of Compassion Fatigue. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 2020;36(2):162-75. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0164212X.2020.1725713. [ Links ]

27. Kyriazos T, Galanakis M, Katsiana A, Saprikis V, Tsiamitros D, Stalikas A. Are Resilient Occupational Therapists at Low Risk of Burnout? A Structural Equation Modeling Approach Combined with Latent Profile Analysis in a Greek Sample. Open Journal of Social Sciences. 2021;9:133-53. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/pdf/jss_2021062114290441.pdf. [ Links ]

28. Zeman E, Harvison N. Burnout, stress and compassion fatigue in occupational therapy practice and education: A call for mindful, self-care protocols. Commentary, National Academy of Medicine; Washington, DC. 2017. [ Links ]

29. Du Plessis T, Visagie S, Mji G. The prevalence of burnout amongst therapists working in private physical rehabilitation centers in South Africa: a descriptive study. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;44(2):11-6. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2310-38332014000200004. [ Links ]

30. McCombie RP, Antanavage ME. Transitioning From Occupational Therapy Student To Practicing Occupational Therapist: First Year Of Employment. Occupational Therapy In Health Care. 2017;31(2):126-42. Available from: https://www.tandfon-line.com/doi/full/10.1080/07380577.2017.1307480. [ Links ]

31. Vears DF, Gillam L. Inductive content analysis: A guide for beginning qualitative researchers. Focus on health professional education. 2022;23(1):111-27. [ Links ]

32. Glen S. Non-Probability Sampling: Definition, Types 2015 [Available from: https://www.statisticshowto.com/non-prob-ability-sampling/. [ Links ]

33. Glen S. Snowball Sampling: Definition, Advantages and Disdvantages 2014 [Available from: https://www.statisticshowto.datasciencecentral.com/snowball-sampling/. [ Links ]

34. Raosoft I. Raosoft Sample Size Calculator. 2004. [ Links ]

35. van Stormbroek K. The extent to which Community Service Occupational Therapists are equipped to treat patients with hand injuries and conditions. Cape Town: The University of Cape Town; 2014. [ Links ]

36. Maslach C, Jackson SE. MBI-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS). In: Mind Garden I, editor. 1981. [ Links ]

37. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Fourth ed: Mind Garden, Inc. (www.mindgarden.com); 1996-2018. [ Links ]

38. Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making Sense of Cronbach's Alpha. International Journal of Medical Education. 2011(2):53-5. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270820426_Making_Sense_of_Cronbach's_Alpha. [ Links ]

39. Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(1):12-9. Available from: https://aliquote.org/pub/JCCP_Jacobson_ClinSIG.pdf. [ Links ]

40. Doulougeri K, Georganta K, Montgomery A. "Diagnosing" burnout among healthcare professionals: Can we find consensus? Cogent Medicine. 2016;3(1):1-10. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2331205X.2016.1237605. [ Links ]

41. Leiter MP, Maslach C. Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Research. 2016;3:89-100. Available from: https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S2213058615300188?token=C28FC-CC7AAB5D055D1834483F14B4F982B4A23AD7272118E0C4E76F6ACC32385F9B2355EFA7AB6A941ED305BE3BE9916&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20220306143141. [ Links ]

42. Balogun JA, Titiloye V, Balogun A, Oyeyemi A, Katz J. Prevalence and Determinants of Burnout Among Physical and Occuapational Therapists. Journal of Allied Health. 2002;31(3):131-9. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11162980_Prevalence_and_determinants_of_burnout_among_physical_and_occupational_therapists. [ Links ]

43. MindGardenInc. 2018 [Available from: https://www.mindgar-den.com/314-mbi-human-services-survey#horizontalTab2. [ Links ]

44. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377-81. Available from: https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S1532046408001226?token=F7777448-16FC5E0D5987A2F061A329CFD40E1E71E01BB72545B401DD78AA27EE987F3A3A4505103504CFDC408FDAEA55&originRegion=eu-west-1&originCreation=20220306141753. [ Links ]

45. Mirzaei A, Carter SR, Patanwala AE, Schneider CR. Missing data in surveys: Key concepts, approaches, and applications. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2021. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1551741121001157?via%3Dihub. [ Links ]

46. Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques.: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1977. [ Links ]

47. TIBCO Software Inc. TIBCO Statistica® 13.5.0 November 2018 [Available from: https://docs.tibco.com/products/tibco-statistica-13-5-0. [ Links ]

48. Leard Statistics. Kruskal-Wallis H Test using SPSS Statistics 2020 [Available from: https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/kruskal-wallis-h-test-using-spss-statistics.php. [ Links ]

49. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62:107-15. Available from: https://academic.csuohio.edu/kneuendorf/c63309/Articles-FromClassMembers/Amy.pdf. [ Links ]

50. Nowakowska-Domagala K, Jablkowska-Gorecka K, Kostrz-anowska-Jarmakowska L, Morton M, Stecz P. The Interrelationships of Coping Styles and Professional Burnout Among Physiotherapists. Medicine. 2015;94(24). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278783752_The_Interrelationships_of_Coping_Styles_and_Professional_Burnout_Among_Physiotherapists_A_Cross-Sectional_Study. [ Links ]

51. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. Available from: https://www.wil-marschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/154.pdf. [ Links ]

52. Innstrand ST, Epnes GA, Mykletun R. Burnout among people working with intelectually disabled persons: a theory update and example. Scandanavian Journal of Caring Science. 2002;16:272-9. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00084.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed. [ Links ]

53. Fred HL, Scheid MS. Physician burnout: Causes, consequences and cures. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2018;45(4):198-202. Available from: https://meridian.allenpress.com/thij/article/45/4/198/84952/Physician-Burnout-Causes-Consequences-and-Cures. [ Links ]

54. Robertson HD, Elliott AM, Burton C, Iversen L, Murchie P, Porteous T, et al. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice. 2016:e423-e33. Available from: https://bjgp.org/content/bjgp/66/647/e423.full.pdf. [ Links ]

55. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:103-11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4911781/. [ Links ]

56. Hardy G. Healthcare burnout - extent and interventions. 70 Arlington Street, Everglen, Cape Town, 7550; 2019. [ Links ]

57. Awa WL, Plaumann M, Walter U. Burnout prevention: A review of intervention programs. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;78:184-90. Available from: https://coek.info/pdf-burnout-prevention-a-review-of-intervention-programs-.html. [ Links ]

58. Halbesleben JRB. Sources of Social Support and Burnout: A Meta-Analytic Test of the Conservation of Resources Model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91(5):1134-45. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6835943_Sources_of_Social_Support_and_Burnout_A_Meta-Analytic_Test_of_the_Conservation_of_Resources_Model_vol_91_pg_1134_2006. [ Links ]

59. Tanner JL. Emerging adulthood. In: Levesque RJR, editor. Encyclopedia of adolescence. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 818-25. [ Links ]

60. Rural Health Advocacy Project. Causes, implications and possible responses to the implementation of staffing moratoria in the public health system in South Africa during times of budget austerity 2013 [Available from: http://rhap.org.za/causes-implications-possible-responses-implementation-staffing-moratoria-public-health-system-south-africa-times-budget-austerity/. [ Links ]

61. Morley M, Rugg S, Drew J. Before Preceptorship: New Occupational Therapists ' Expectations of Practice and Experience of Supervision. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;70(June):243-53. Available from: https://www.deepdyve.com/lp/sage/before-preceptorship-new-occupational-therapists-expectations-of-CntqtrIRde. [ Links ]

62. Melman S, Ashby SE, James C. Supervision in Practice Education and Transition to Practice: Student and New Graduate Perceptions. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 2016;14(3):Article 1. Available from: https:/www.researchgate.net/publication/309549539_Supervision_in_Practice_Education_and_Transition_to_Practice_Student_and_New_Graduate_Perceptions. [ Links ]

63. Steenbergen K, Mackenzie L. Professional support in rural New South Wales: Perceptions of new graduate occupational therapists. The Australian Journal of Rural Health. 2004;12(4):160-5. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1440-1854.2004.00590.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed. [ Links ]

64. Edwards D, Burnard P, Hannigan B, Cooper L, Adams J, Juggessur T, et al. Clinical supervision and burnout: the influence of clinical supervision for community mental health nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2006. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01370.x. [ Links ]

65. Adarkwah CC, Hirsch O. The Association of Work Satisfaction and Burnout Risk in Endoscopy Nursing Staff-A Cross-Sectional Study Using Canonical Correlation Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(2964):1-13. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340902824_The_Association_of_Work_Satisfaction_and_Burnout_Risk_in_Endoscopy_Nursing_Staff-A_Cross-Sectional_Study_Using_Canonical_Correlation_Analysis. [ Links ]

66. Moore K, Cruickshank M, Haas M. Job satisfaction in occupational therapy: a qualitative investigation in urban Australia. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2006;53:18-26. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229897089_Job_satisfaction_in_occupational_therapy_A_qualitative_investigation_in_urban_Australia. [ Links ]

67. Swanepoel JM. Job satisfaction of occupational therapists in the public health sector, Free State province. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State; 2010. [ Links ]

68. Maleka E. Soft skills training in health sciences students at the University of the Witwatersrand. 2020. [ Links ]

69. World Federation of Occupational Therapists. Minimum Standards for the Education of Occupational Therapists: World Federation of Occupational Therapists; 2016 [Available from: https://www.wfot.org/assets/resources/COPY-RIGHTED-World-Federation-of-Occupational-Therapists-Minimum-Standards-for-the-Education-of-Occupational-Therapists-2016a.pdf. [ Links ]

70. Community Service Link 2022 [Available from: https://theot-link.com/events/comm-serve-link/. [ Links ]

71. RuReSA. RuReSA Award for the Rural Rehab Healthcare Worker of the Year 2022 [Available from: https://www.ruresa.com/about-the-award--award-winners.html. [ Links ]

72. Powell K. Students adapt to their own COVID journey challenges. The South African Institute for Sensory Integration; 2020. [ Links ]

73. Bhandari P. Sampling bias: What is it and why does it matter? : Scribbr; 2020 [Available from: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/sampling-bias/#:~:text=Sampling%20bias%20in%20non%2Dprobability%20samples&text=Non%2Dprobability%20sampling%20often%20results,to%20be%20included%20than%20others.&text=Because%20this%20is%20a%20convenience,representative%20of%20your%20target%20population. [ Links ]

74. Stockemer D. Quantitative Methods for the Social Sciences: A Practical Introduction with Examples in SPSS and Stata. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99118-4. [ Links ]

75. Thomas G. How to do Your Research Project. 1st ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009. [ Links ]

76. Hassan ZA, Schattner P, Mazza D. Doing A Pilot Study: Why Is It Essential? Malaysian family physician: the official journal of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia. 2006;1(2-3):70-3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4453116/. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Nadia Struwig

nstruwigot@gmail.com

Received: March 2022

Peer reviewed: August 2022

Revised: October 2022

Accepted: November 2022

Published: April 2023

Editor: Hester van Biljon: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4433-6457

Funding: NS received financial support for this project from the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Office, University of the Witwatersrand and the Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa (OTASA) who awarded NS with the Ruth Watson Research Grant in 2019. KvS is supported by Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA) which is funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Grant No: B 8606.R02), Sida (Grant No:54100029), and the DELTAS Africa Initiative (Grant No: 107768/Z/15/Z).