Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.52 no.3 Pretoria dic. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2022/vol52n3a9

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Occupational enablement through the Crosstrainer programme: Experiences of early childhood development practitioners

Adeleigh HomanI, *; Santie van VuurenII, *; Danette de VilliersIII, *

I'Missionary, Fire and Fragrance, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5951-4861

IIUniversity of the Free State, South Africa https:///orcid.org/0000-0002-9953-3274

IIIUniversity of the Free State, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6770-2854

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: In rural South Africa, inadequately trained Early Childhood Development practitioners and inequity of access have been placed as top priorities to address. Enabling occupation is the primary goal and core competency of occupational therapists and supporting the services of ECD practitioners may address these problems. The Crosstrainer Programme aims to do this by training and equipping ECD practitioners. ECD practitioners were therefore approached to reflect on the occupational enablement through the Cross-trainer Programme

METHOD: Demographic questionnaires and semi-structured interviews were utilised. The data were analysed through the cyclical process of coding.

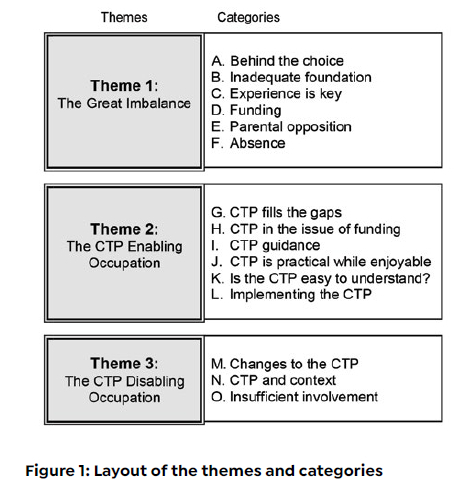

RESULTS: Three major themes emerged from the data analysis, namely The Great Imbalance, Enabling Occupation, and Disabling Occupation. The participants expressed the difficulty of fulfilling the need for their services in their communities. The CTP relieves these difficulties and enables the work of ECD practitioners through increased knowledge, confidence, creative alternatives to resources, and guidance in managing their time, incorporating all six enablement foundations. The CTP disables their occupation of work through the language barrier, unclear scaling of the activities, and insufficient involvement.

CONCLUSIONS: The CTP enables the occupation of the ECD practitioners and the children. Through translating the programme, adding more activities, and increasing involvement and mentoring, enablement through the CTP will improve.

Keywords: enabling occupation; ECD; early learning programme; rural ECD centres; South African preschool; early learning centre; preschool teachers.

INTRODUCTION

Currently, in South Africa, it is recognised that rural areas are deprived of essential Early Childhood Development (ECD) services1. The South African ECD sector has been experiencing inequity of access to good quality early learning programmes, which creates a distinct disadvantage and school-readiness gap for children from poorer communities or low-level income families2-3. Consequently, quality early learning opportunities for all South African children have become a top priority2.

Therefore, the National Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy, a relatively new policy in South Africa approved by the Cabinet in December 2015, mandates the provision of ECD services as a right of all children without discrimination. The long-term goal aims to provide a comprehensive, developmental stage-appropriate ECD package providing necessary services to reach the Constitutional rights of South African children and their holistic development2,4. However, many children and ECD practitioners in rural areas may still have difficulties to access such opportunities3,5. Consequently, it is critical for different departments to collaborate in addressing this inequity1-3, predominantly from the private and non-profit sectors, until such time as the governmental policy has been fully implemented1,4.

Being a change agent is attributed as a central role and proficiency of occupational therapists6. Occupational therapy recognises a broader global and social responsibility towards the issues of inequity and poverty, as it has the potential to benefit both the wider society and the individual! Becoming involved in the ECD change is therefore imperative for South African occupational therapists.

Moreover, the programmes utilised have to be of good quality1. This is reached through increased training of and support to ECD practitioners1-2. In South Africa, an ECD practitioner is defined as someone trained formally or informally to provide early learning services and childhood development in an ECD centre to children from birth to school-going age8. However, South African ECD practitioners, especially in rural or low-socio economic areas, have been deemed inadequately trained1. Therefore, the training of these practitioners has been established as an essential component towards an improved ECD sector1.

The need for more, trained ECD practitioners enthused the Crossroads Educational Foundation, a Non-Profit Organisation (NPO), to invest in Early Childhood Development in South Africa9. Consequently, the organisation developed and established the Crosstrainer Programme (CTP) in order to train and equip ECD practitioners. The CTP is an ECD centre-based programme providing early learning stimulation for children from three to six years of age in rural African, especially South African, areas9. It consists of a systematic guide (set of books) with daily, age specific, zero to low-cost activities, which were derived from basic occupational therapy knowledge to ensure that all the critical stages of ECD are covered and a foundation for future learning accordingly secured10. The books are designed for ECD practitioners in the rural setup to simply follow, implement and adapt where necessary. It aims to empower the practitioners to provide the essential early learning services and childhood development in their ECD centres for the children and ultimately address the issue of inequity and access3,9.

For occupational therapists, a social responsibility towards the issues of inequity and poverty is recognised, as occupational therapy has the potential to benefit the wider society as well as the individual7. And occupational therapy enablement is not only limited to individuals with impairments but aims toward health, well-being, and justice for individuals and the human population through occupa-tion6,11-12. Therefore, becoming involved in the change of the South African ECD sector, is also the responsibility of occupational therapists. This central role of the occupational therapist within the community has evolved to become a core rather than subordinate focus and greater emphasis is placed on prevention, public health promotion and community development in the South African health care con-text13. Even within the community, occupational therapists focus on occupation as the core domain of concern. Being a change agent for the ECD sector and specifically these ECD practitioners include focussing on their occupation and the enablement thereof.

Human occupation is considered the core domain of concern in occupational therapy11-12. In occupational therapy, occupation is an ever-evolving term and has further been refined to much more than a career or activity in which people engage. Occupation is essential to all people as humans are born as occupational beings. It also possesses potential therapeutic value12,14,15. It refers to every activity or everything humans engage in their daily living and is essential to promote health and well-being which in turn also describe who a person is and how one feels about oneself16.

Enabling occupation is the core competency and primary goal of occupational therapists11-12. Any person, thing, or environment can essentially enable or disable occupation. In occupational therapy, enablement encompasses more than providing opportunities, simplifying, or assisting. Occupational therapy enablement goes beyond the enablement of everyday life12. This enablement aims toward health, well-being, and justice for individuals and the human population through occupation6,11-12. Therefore, occupational enablement for the ECD practitioners relates to more than occupation as a career, but as a daily activity they partake in as an individual, directly involving their immediate communities.

In the context of occupational therapy, there are six foundations of occupational enablement, which were coined and defined by Townsend and Polatajko in their publication of 'Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-being, & Justice through Occupation'12. Each foundation is described briefly in Table I on page 75:

Human occupation and the enablement thereof are best investigated within occupational therapy enablement because it forces critical reflection and accounts for multiple perspectives, inequities of power, and diversity12. Therefore, these six foundations as seen in Table I (page 75) were used to describe the enablement of the ECD practitioners' occupations, as derived from their experiences incorporating the CTP. Within the South African ECD sector, enabling the occupation of the ECD practitioners through training, mentoring, and providing support will play a major role in transforming the ECD sector. Additionally, these strategies will support the efforts of the South African government and other organisations towards this improvement. The CTP could be a possible instrument towards providing such training and support. Allowing the ECD practitioners to reflect on their experiences of the CTP and the occupational enablement thereof could give more understanding on this, given the reflections are appropriately disseminated.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The purpose of the research is to describe the experiences of the ECD practitioners regarding the occupational enablement through the CTP. No prior research has been done on the perceptions of the ECD practitioners concerning the CTP nor the enablement thereof. Therefore, this study was aimed at obtaining rich, descriptive data by collaborating and generating knowledge with a sample of ECD practitioners using the CTP.

Research paradigm

The constructivist paradigm was used, which allowed the researcher to generate knowledge together with the participants. 'Truth' is therefore constructed by the personal experiences of the participants and then transposed by the researcher. A certain sense of subjectivity and the personal voice of the researcher are evident in this paradigm and should not be ignored or denied17,18.

Study design

A Descriptive Qualitative research design was utilised with supportive quantitative demographic data to gain rich, descriptive data.

Unit of analysis

The study population included ECD practitioners situated in the Mafikeng Rural area who have received training in the CTP. The total population of ECD practitioners trained in the CTP in the Rural Mahikeng Area is 37. Non-probability, purposive (judgmental) sampling18 was used to approach all the ECD practitioners who met the following eligibility criteria:

• The ECD practitioner had to have been trained in the CTP.

• ECD practitioners from the same training dates, therefore excluding any variations in the CTP training.

• The ECD practitioner had to have had at least six months' experience in practice with the CTP to promote integrated perceptions within the discussion. This was to ensure that the practitioner had had ample time to engage with the CTP and would therefore be able to have reached opinions and experiences to bring across in the interviews.

• ECD practitioners of all cultural groups within the specific population were included in the study.

• ECD practitioners who comfortably spoke and understood English and/or Setswana were included. The service of a translator was offered to any participant who may have preferred to conduct the session in Setswana.

ECD practitioners were excluded from this study if any of the above criteria was not met.

Nine ECD practitioners met the inclusion criteria and completed the interview, questionnaire, and member checking processes. No data saturation point was reached 20. Pseudonyms were allotted to the final nine participants.

Table II (page 76) presents a general description of the participants as obtained from the questionnaires.

As Table II (page 76) reveals, all the participants were female with the median age of 43. Only three of them graduated high school, of which two completed tertiary qualifications, specifically diplomas. Five had completed some ECD level training, of which only two completed all five levels. Four participants had ten years or less experience and the remaining five had more than ten years of experience as ECD practitioners.

These ECD practitioners were distributed over eight ECD centres as two participants were from the same ECD centre. Table III (page 76) presents a general setup of the ECD centres, as described by the ECD practitioners

From Table III, it can be deducted that their ECD centres varied in building types, number of classes, availability of resources and equipment, yet marginally similar environments. Therefore, these ECD centres were concurrent with the description of typical rural South African ECD centres3,19.

Data collection and management

Data were collected through two methods: A questionnaire presented in English and Setswana was completed by the participant right before the interview commenced. The questionnaire aimed at collecting demographic information in order to describe the participants' context in detail. Most of the information generated from the questionnaire was used to describe the population in the previous section.

Semi-structured interviews were held with each participant. During these interviews, the experiences from the participants were elicited by having face-to-face discussions. An interview protocol21 was formulated to guide the structure of the interview, whilst allowing for a semi-structured interview process. The interviews were recorded with the help of two voice recordings to capture both the English and translated questions and answers. These were copied to an external hard drive after each day of interviews to ensure safe storing. Data from the transcriptions were coded and analysed with the help of one co-coder. Side notes were taken during the interviews for personal use to assist with referring to specific moments in the interview21. These were filed for safekeeping.

The process of member checking (participant review or validation) occurred once all the statements were summarised and presented during a brief follow-up interview with each of the nine participants, which was recorded and transcribed. Consensus was reached with each participant during this process21.

Data analysis

The data received from the interviews were analysed using a flexible, yet widely used process namely, thematic analysis22. The process of coding was done manually by two of the authors. As coding is a cyclical process rather than linear22, two coding cycles were employed, allowing for coding, recoding, and comparing. For the first cycle of coding, a Descriptive coding22 method was used to create an inventory of the data, from which patterns and reoccurring topics were created. As this method does not necessarily allow for much insight into the participants' thoughts, a second coding cycle was conducted using Pattern Coding 22. This was used to cluster similar codes into pattern codes, which formed valuable codes for recognising emergent categories and themes.

The demographic information obtained by the questionnaire was analysed by the University of the Free State Department of Biostatistics to calculate descriptive statistics for continuous data. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical data.

Trustworthiness

In this study, multiple strategies were used to ensure trustworthiness. The translator of the documents and interviews holds a BA Education and Setswana degree, has over 15 years of experience in ECD and is qualified as a registered nurse. External reviewing by an external critical reader 21 and the involvement from the Education and Research Committee of the School of Allied Health Professions of the University of the Free State. Furthermore, member checking, prolonged engagement with the participants, using a thick description and keeping an audit trail further increased trustworthiness in this study 21.

Ethics

Ethical approval was received from the Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Free State (HSREC 67/2017, dated 19 June 2017). Informed consent was received from the participating ECD practitioners and their ECD centre principal. Participants were allotted pseudonyms and all their information has been kept confidential.

FINDINGS

Three major themes emerged from the cyclical process as discussed in the data analysis section. These were formulated as the Great Imbalance, the CTP Enabling Occupation, and the CTP Disabling Occupation.

Each theme and category from Figure 1 (page 76) will be briefly discussed below with quotes from some of the participants.

THEME 1: THE GREAT IMBALANCE

The Great Imbalance summarises the difficulties experienced by the ECD practitioners during the process. This theme is aimed at portraying the imbalance between the ECD practitioners' love and passion for children and the difficulties they experience in their occupation of work.

Category A: Behind the choice of becoming ECD practitioners for the majority was the love and passion they have for children. They noticed a need in their communities for children to be cared for, kept safe and educated and felt the urge to take responsibility. It is due to their love and passion that they endeavoured to becoming and growing as ECD practitioners but they face many hindrances in doing so.

"My favourite part of being a practitioner is because I love children; I have a long heart [laughs]." (Cathy)

"I cannot live without kids; that's my life. So being a practitioner is a call. I am not here by mistake... I've never used ECD as business; I use it as my life." (Dora)"...the kids need someone to look after them. So, to us, we are just going to look after these kids... but it started from that love." (Anna)

"...the kids need someone to look after them. So, to us, we are just going to look after these kids... but it started from that love." (Anna)

Category B: One of the hindrances mentioned by the majority of participants was having an inadequate foundation as ECD practitioners. They explained that they felt they had a lack of knowledge and felt unqualified to be ECD practitioners due to their background.

"I never dreamed that I would be a teacher because of my background, you know, less qualified." (Anna)

Category C: Additionally, they explained that experience is key and that often only after years of experience do they feel confident enough in being ECD practitioners.

"Right now, nothing is difficult 'cause what I'm doing it's what I've already done before." (Cathy)

Category D: The barrier of funding posed another issue disabling their occupations, their biggest challenge being the parents not paying the fees for the children to attend their ECD centres. This causes stress for the ECD practitioners, as they are dependent on the monthly fees to buy materials, equipment, and food for the children.

"Because I'm working with the parents in the rural area and then the payments starve." (Grace)

"Sometimes they bring the children, they don't bring the money for the school fees. That's the challenge." (Edith)

Category E: On top of slacking on payments, parental opposition was also mentioned as a frustration for the ECD practitioners as some participants explained that they often experience high expectations from parents whilst not receiving their monthly payments. This often results in the wanting to quit, but their love for the children motivates them to press on regardless.

"...most of the time parents are difficult... You can find other that are on the same page as you...what would make me say 'ai, ai, I'll quit this crèche'. But on the other side, I feel for other children who their parents don't have that difficulties." (Cathy)

Category F: The absence of the children results in low progress of their development. Many children had a poor attendance at the ECD centre due to various reasons and consequently a low understanding of the work.

It is difficult when I am teaching and a child stays away from school. The child falls behind and stays behind through the year, which reflects badly on me. (Paraphrased by translator - Frieda)

This theme shows how the ECD practitioners constantly need to overcome barriers to live out their passion and to take responsibility for the needs of the children. The following two themes are aimed at portraying how the CTP may enable or disable their occupations as experienced by the ECD practitioners. The findings will be discussed briefly for each theme.

THEME 2: THE CTP ENABLING OCCUPATION

This theme looks at how the ECD practitioners found the CTP enabled their occupation. Many of the hindrances discussed in the previous theme were actually addressed in some way by the CTP.

Category G: It was found that the CTP fills the gaps mentioned in the previous theme by giving them more knowledge, fuelling their growth as ECD practitioners and consequently boosting their confidence. Some participants also mentioned that they received positive feedback from the parents since implementing the CTP in their ECD centres.

"So 2015, after using these books [CTP], there was light now and I started realising, seeing my way forward." (Irene)

"Since I met the CTP I am brave enough to do the things that I never thought I would do, the things I never thought I knew how to do." (Dora)

Category H: The participants expressed that the CTP has helped regarding the issue of funding in two ways. Firstly, that the CTP modified the way they thought about equipment and activities by guiding them to make their own or improvise with what they have. Secondly, that the CTP was in most instances the only equipment they needed, as they only have to implement the daily activities from the lesson plans using the supportive materials in the books.

"Yes, it has given me different ideas..." (Edith)

She said, before she started with the CTP she had to get a lot of things. But since she started with CTP, she's got everything. Everything is just compact (Indirectly translated - Hester)

Category I: Additionally, the guidance given by the CTP assisted the ECD practitioners through directing their lesson plans and time management, in turn lightening their workload.

"I helped me about how to plan, lesson plan." (Grace) "It leads me, gives me direction where to go." (Dora)

CategoryJ: Some participants also mentioned how the CTP is practical while enjoyable.

"It helps me a lot with activities... we read there, then we do the practicaL.and it's enjoyable."(Edith)

Category K: According to the ECD practitioners the CTP was easily understood, as the CTP was easy for them to implement and easy enough for the children to understand the content.

"...it [CTP] gets easily into children." (Cathy)

Category L: Simply implementing the CTP also positively affected them to taking more responsibility and even taking initiative to add to the CTP activities.

"So it pushed my responsibility that I have to focus on my work." (Grace)

From these categories, it can be seen that the CTP enables their occupations especially by bringing solutions to what they would generally find hindering them.

THEME 3: THE CTP DISABLING OCCUPATION

In constructing this theme, disabling factors were derived by the changes the participants wanted to see in the CTP as well as other problems they brought up during the interviews. The three categories that emerged were:

Category M: Some mentioned changes to the CTP they would like to see, which included translating the CTP to Setswana (as it is only available in English at this point) and adding more pictures for them to use. However, it is important to note that the majority of participants explicitly said the CTP did not need to change in any way.

"No, now I just think that if the books can be... some of it must also Setswana. I think it's easier." (Anna)

"In most cases, almost every day I'm teaching the themes. Sometimes it becomes more difficult when I don't have material. Then, at least, if I can have some picture or get something, it can make it very simple." (Dora)

"No, according to my observation, I don't think should change." (Grace)

Category N: This further stirred the question of the CTP and

context. The fact that the books are only available in English is a disabling factor as most children's home language is Setswana in that area and the primary schools expect ECD centres to teach the children in Setswana (main language in the area). As a solution, they opt to translate the lessons themselves.

"...because if you keep teaching them English, to them at the end of the day is hard at school." (Anna)

"I translate it in Setswana for them and they understand." (Edith)

Two participants mentioned that they found the demand on the ability of the children too high and that they had to adapt some of the lessons for the children.

Category O: Lastly, the participants expressed that they feel the insufficient involvement from the CTP hindered their occupation. This was evident as some explained their need for more regular monitoring, more assistance with administration and more opportunities for other ECD practitioners to be trained as well.

"I just think this CTP can make like more time for us; they can workshop us again... all teachers must go there..." (Betty)

"...it doesn't mean I'm stuck if you don't come. It's just; I get strength when someone comes.even if you can just call." (Dora)

"...Yes, even if you can just phone." (Anna)

It is clear that the language and the limited involvement from the CTP are the major disabling factors in this theme.

DISCUSSION

THE GREAT IMBALANCE

It was apparent throughout this theme that the participants truly chose to become ECD practitioners due to having a love for children, calling it a passion, not only a career choice. Moreover, they recognised a need in their communities for a safe place for children to grow and develop and that their ECD centres provided that safe place. This correlates with findings from other studies23-25 and links with the occupational enablement foundation of justice, advocating a belonging and participating in society12.

However, the participants shared significant inequities they experience as they endeavoured in doing what they are passionate about, being ECD practitioners, becoming competent, and belonging in their communities. They felt hindered by their inadequate training, limited experience, personal background, financial barriers, parental opposition, and low attendances. Therefore, when considering the enablement or disablement of their occupation, it needed to be in light of these hindrances.

THE CTP ENABLING OCCUPATION

Enabling occupation refers to providing the necessary opportunities and means for individuals, groups and communities to shape their own lives and enable their occupation12. The CTP uniquely enables the occupation of work in a few ways and according to the ECD practitioners, the CTP brought solution to most hindrances mentioned in the first theme. The enablers are discussed in light of the six occupational enablement foundations as previously defined.

The CTP encouraged the ECD practitioners to make their own choices, take new risks or transcend existing risks, and to take responsibility in their ECD centre and the lessons12. The ECD practitioners are encouraged to adapt the CTP activities to suit their context and means. Implementing the CTP resulted in them being drawn in to be actively involved and taking more responsibility. This was increased even more as they were given necessary skills to participate, which in turn promoted more participation from the ECD practitioners12, 13.

Visions of possibility12 increased by the CTP through availing knowledge, boosting their confidence, fuelling their growth as practitioners, and modifying their thinking on the equipment that is necessary for activities. Since the CTP, they have believed themselves to be capable of doing previously unthinkable tasks, mastering their skills, and embracing new opportunities. These necessary changes12 enabled their occupation.

The CTP strengthens their belonging in society as ECD practitioners by increasing their knowledge and confidence, alleviating the issue of funding, and guidance. Providing guidance through directing lesson plans and time management and in turn lightening their workload, a unique but contextu-ally specific way of pursuing justice12. Power-sharing was evident throughout the interviews as they shared that they were able to implement, adapt and change where necessary and therefore collaborate with the CTP in the process of teaching the children12. Although they enjoyed much autonomy in practice, it is in light of their minimal resources and limited assistance from the government that qualifies this collaborative approach as enablement. Furthermore, in another study it was found that following a generic ECD curriculum would achieve very little if anything at all23.

Therefore, the CTP contributed through all the enablement foundations to the enablement of their occupation as ECD practitioner.

THE CTP DISABLING OCCUPATION

Just as anything or anyone could potentially enable occupation, this much is true towards disabling occupation12. To disable also refers to preventing, restricting or even discouraging a person from doing something26. The term disabling occupation was also coined and defined by Townsend and Polatajko12.

From the findings it can be seen that the CTP hindered the occupation of the ECD practitioners in two ways.

The first is regarding the alignment of their context, particularly concerning three aspects: not having the CTP in their main teaching language, the level of difficulty of some of the activities, and the need for more visual aids or pictures in the lessons. Although the minority of participants mentioned these aspects, it is still important to note as a disabling factor.

The second disabling factor was their experience of insufficient involvement from the CTP, specifically regarding these three aspects: minimal monitoring, the need for more administrative help, and seldom opportunities for training. The participants expressed that they need more regular monitoring, administrative assistance and opportunities for training from the CTP. This correlates with other South African programmes and organisations 27, 28 also involved in training ECD practitioners, as they practise a higher level of involvement through more regular follow-ups, administrative aid, and regular training.

It was also found from numerous other studies and ECD programmes that increased levels of monitoring positively affects the fidelity of the ECD practitioners and therefore the efficacy of the programme23-27, 28.

Limitations of this study

Three limitations occurred in this study, which could otherwise have potentially added additional information and depth to the study. The first is that the culture of the participants was not explicitly considered during the research process, limiting contextual description. The second was that during the conduction of the interviews, the participants preferred to speak English instead of their home language, which may not have rendered the potential depth of discussion in some cases. The third is not taking field notes, which could have contributed to a thick description.

Recommendations

Further research is recommended on the CTP, occupational enablement, and the South African ECD practitioners. This could include conducting a similar study on a wider population in South Africa, a comparative study on the occupational enablement from different ECD programmes, a study on the occupational enablement of the CTP on the occupation of the children, a study using PAR (participatory action research) towards developing a tailor-made programme for each ECD centre.

Based on the findings and the experiences of the ECD practitioners, I would like to render a few recommendations that could improve the CTP: adding more pictures in the CTP books, increasing administrative assistance, training opportunities and monitoring, and translating the CTP to the main educational languages of South Africa.

CONCLUSION

The ECD practitioners painted a picture of the great imbalance as they want to fill a need in their communities because of their passion for children, but are hindered by feelings of inadequacy, the reality of their backgrounds, finances, and cooperation from the parents of the children. The participants mentioned how the CTP has given them more knowledge, confidence, creative alternatives to resources, and guidance in managing their time.

The CTP mainly disables their occupation by not having the programme available in their main teaching languages, by feeling unsure on how to scale lessons, and insufficient involvement from the CTP. These can simply be bettered by investing in translating the programme, adding more options to the activities, and increasing the level of involvement.

In conclusion, upon implementing these necessary changes, the CTP is a valuable programme towards the occupational enablement of South African ECD practitioners and the children in their centres.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the participants of this study. To Emily Thloloe-Megalane we express our gratitude for her invaluable guidance and assistance as our contact in the field. We have great appreciation for the Crossroads Educational Foundation team and Eddie Schoch for their involvement and commitment in the South African ECD sector.

Author contributions

Adeleigh Homan conceptualised and completed the research for a master's level postgraduate degree in occupational therapy. Santie van Vuuren and Danette de Villiers were supervisors and contributed with the conceptualisation, supervised the data gathering and analysis, drafting, revision and completion of the article.

Conflict of interest

During the time of conducting the study, the corresponding author was appointed by Crossroads Educational Foundation to investigate the efficacy of the Crosstrainer Programme. This was not to prove the value of the CTP, but to discover both the value and the limitations of the programme.

REFERENCES

1. Hall K, Sambu W, Berry L, Giese S, Almeleh C. South African Early Childhood Review. 2017 (Vol. 1). Cape Town: Children's Institute; 2017. Available from: http://ilifalabantwana.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/SA-ECR_2017_WEB-new.pdf. [ Links ]

2. Hall K, Sambu W, Berry L, Giese S, Almeleh C, Rosa S. South African Early Childhood Review. 2016. Cape Town: Children's Institute; 2016. Available from http://ilifalabantwana.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/SA-ECD-Review-2016-low-res-for-web.pdf [ Links ]

3. Department of Education. Education White Paper 5 on Early Childhood Education: Meeting the Challenge of Early Childhood Development in South Africa. Pretoria: Department of Education, 2001. [ Links ]

4. Republic of South Africa. National Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy. 2015. Pretoria: Government Printers; 2015. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/reports/national-inte-grated-early-childhood-development-policy [ Links ]

5. South African Schools Act No.84 of 1996, Government Gazette 34620 [statute on the Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017 June 1]. Available from: http://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=aIolZ6UsZ5U=&tabid=185&mid=1828 [ Links ]

6. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Profile of Practice of Occupational Therapists [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2016 August 22]. http://www.caot.ca/pdfs/2012otprofile.pdf [ Links ]

7. Pollard N, Alsop A, Kronenberg F. Reconceptualising occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2005; 68(11): 524-532. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260506801107 [ Links ]

8. National Development Agency. Best Practitioner of the Year: Entry Form [form on the Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 March 30]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/southafrica/SAF__ecdawards_practitioner2015.pdf [ Links ]

9. Crossroads Educational Foundation. Crosstrainer Programme [Internet]. Wordpress.com; 2017 [cited 2018 August 22]. https://crossroadseducationalfoundation.com/ [ Links ]

10. De Villiers D, Homan A, Van Rooyen, C. Early Childhood Development and the Crosstrainer Programme in Rural Mahikeng. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019; 49(2): 18-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/23103833/2019/vol49n2a4 [ Links ]

11. Pierce D. Occupational Science for Occupational Therapy. NJ: SLACK Incorporated; 2014. [ Links ]

12. Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-being, & Justice through Occupation. Second Edition. Ottawa, Ontario: CAOT Publications ACE; 2013. [ Links ]

13. Janse van Rensburg, E. Chapter 1, Enablement - A Foundation For Community Engagement Through Service Learning in Higher Education. In: Knowledge as Enablement. Erasmus M, Albertyn R (eds). Stellenbosch: SUN PRESS; 2014: 42-61. https://doi.org/10.18820/9781920382636/01 [ Links ]

14. Kielhofner G, Posetary Burke J. A Model of Human Occupation, Part 1. Conceptual Framework and Content. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1980; 34(9): 572-581. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.34.9.572 [ Links ]

15. Kielhofner G, Posetary Burke J, Heard Igi C. A Model of Human Occupation, Part 4. Assessmet and Intervention. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1980; 34(12): 777-788. [ Links ]

16. World Federation of Occupational Therapists. Definitions of Occupational Therapy from Member Organisations. WFOT. 2013: 11. Available from: https://wfot.org/checkout/1213/22040 [ Links ]

17. Gray DE. Doing Research in the Real World. Third Edition. London: SAGE; 2014. Available from: http://www.uk.sagepub.com/books/Book239646#tabview=toc. [ Links ]

18. Guba EC. The Paradigm Dialog. London: Sage Publications; 1990. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357527032000140352 [ Links ]

19. Onwuegbuzie AJ, Collins KMT. A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The Qualitative Report. 2007; 12(2): 281-316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2003.12.001 [ Links ]

20. Gardiner M. Education in Rural Areas. Fourth Edition. Johannesburg: Centre for Education Policy Development; 2008. Available from: https://www.saide.org.za/resources/Library/Gardin-er,%20M%20-%20Education%20in%20Rural%20Areas.pdf [ Links ]

21. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Research design Qualitative quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Fourth Edition. California: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2 [ Links ]

22. Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Third Edition. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181ddfd0a [ Links ]

23. Brink S. Employing a multifocal view of ECD curriculum development at a rural settlement community in South Africa: Themes from a 'design by implementation'early childhood education programme. South African Journal of Childhood Education. 2016; 6(1): a405. http://dx.di.org/10.4102/sajce.v6i1.405 [ Links ]

24. UNICEF. Early Childhood Development Knowledge Building Seminar. Pretoria: UNICEF; 2014. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/reports/early-child-hood-development-knowledge-building-seminar [ Links ]

25. Vorster A, Sacks A, Amod Z, Seabi J, Kern A. The everyday experiences of early childhood caregivers: Challenges in an under-resourced community. South African Journal of Childhood Education. 2016; 6(1): a257. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v6i1.257 [ Links ]

26. Oxford University Press [Internet]. Disable. 2018 [cited 2018 May 22]. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/disable [ Links ]

27. Bafenyi Trust [Internet]. Dinaledi Program. 2018 [cited 2018 June 8]. https://bafenyi.org.za/index.html [ Links ]

28. Sikhula Sonke Early Childhood Development [Internet]. Im-bewu: Seeds of Success. 2018 [cited 2018 June 8]. http://www.sikhulasonke.org.za/programmes.html [ Links ]

Submitted:31 August 2020

Reviewed: 15 October 2021

Revised: 6 August 2022

Accepted:8 August 2022

Corresponding author:Adeleigh Homan adeleigh7@gmail.com

DATA AVAILABILITY: On request from corresponding author.

EDITOR: Hester van Biljon

FUNDING: No funding was obtained for this study.

* Was a post graduate student at the University of the Free State, South Africa, at the time of the research. "Currently retired.