Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.52 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2022/vol52n3a8

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Enablers and inhibitors to quality of life as experienced by substance abusers discharged from a rehabilitation centre in Gauteng, South Africa

Marusa Lebogang LefineI; Ramadimetja Annah LesunyaneII

IDepartment of Occupational Therapy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Gauteng, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4293-8756

IIDepartment of Occupational Therapy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Gauteng, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2468-0683

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The impact of substance-related and addictive disorders is a serious health problem affecting society. Occupational therapy intervention for people with substance-related disorders is ultimately directed at enhancing the quality of life. This article aims to present participants' experiences regarding their quality of life on their journey to sobriety.

METHODS: A qualitative study, where an exploration of participants' perceptions and description thereof was used to gain insight into participants' experiences of their quality of life after discharge from a rehabilitation centre. Individual, semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from a purposive sample of 20 participants. The interviews were based on the Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life: A Direct Weighting Procedure for Quality-of-Life Domains (SEIQoL - DW). Data collected were analysed using thematic content analysis.

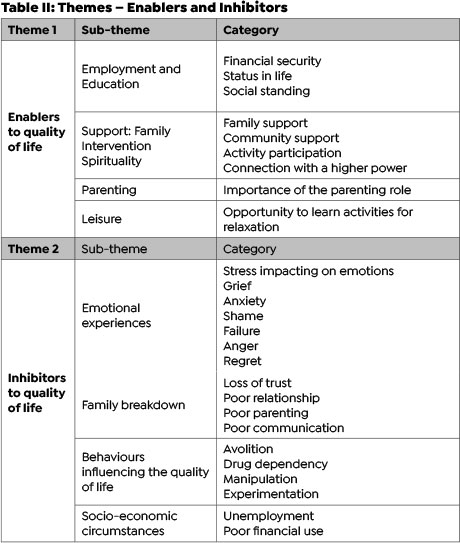

FINDINGS: Two themes, namely (1) "enablers of quality of life", and (2) "quality of life inhibitors", emerged from the interviews. The participants described the enablers of quality of life as employment, education, support, parenting and leisure; while emotions experienced, family breakdown, harmful behaviours and socioeconomic status were described as the inhibitors of quality of life.

CONCLUSIONS: Engagement in occupations is important for the substance user to enhance their quality of life. Occupation-based occupational therapy intervention is therefore crucial in enhancing quality of life, particularly in the life of a substance user whose lifelong journey to sobriety is challenged daily by the barriers they encounter.

Key words: Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life, SEIQoL - DW, occupation-based occupational therapy, socioeconomic status, employment and education, drug rehabilitation.

INTRODUCTION

"Drug/alcohol use refers to the general use of drugs/alcohol and usually starts on an experimental basis"1 Drug/alcohol abuse resulting from experimentation can cause individuals to become addicted despite the harmful and dangerous effects1. Repeated substance use over time causes intense activation of the brain reward system, resulting in the neglect of normal activities. According to the DSM-52483, "The essential feature of a substance use disorder is a cluster of cognitive, behavioural, and physiological symptoms indicating that the individual continues using the substance despite significant substance-related problems". With the continued use of substances, quality of life is negatively impacted, resulting in reduced life satisfaction and wellbeing3. Quality of life is defined as a client's dynamic appraisal of life satisfaction (perceptions of progress toward identified goals), self-concept (the composite of beliefs and feelings about themselves), health and functioning (including health status, self-care capabilities), and socio-economic factors (vocation, education, income)4.

Occupations are pertinent to the client's health status, identity, and competence, influencing the quality-of-life experienced4. Occupations are central to health and wellbeing as they provide identity, meaning and structure to peoples' lives5. In occupational therapy, occupations are understood as the activities one does in everyday life. It is through occupational performance that the client is able to function in their context. Occupations contribute to a well-balanced lifestyle that enhances the quality of life5. Furthermore, occupations are reported to include daily activities that enable people to sustain themselves, contribute to the lives of their families and participate in society6. Crowe7 reports that young people in South Africa who persistently abuse substances find themselves experiencing an array of challenges in occupational engagement that include academic difficulties, health-related problems, poor peer relationships and ultimately, falling foul of the law. The challenges not only end with them but also extend to their family members, the community, and society. The implication of these challenges poses difficulties for young persons recently discharged from a rehabilitation unit, to change their behaviour, and adopt productive lifestyles through engagement in meaningful occupations7. A study by Denis8 on alcohol-dependent patients in Pennsylvania (US) indicated that substance use had a significantly negative impact on the quality of life in education, employment, and social participation. He further found a higher impact on participants' mental functions than physical functions, ultimately negatively affecting their quality of life.

The primary outcome of occupational therapy intervention is to assist clients who are using substances to maintain a lifestyle without using drugs and improve their quality of life1. Furthermore, occupational therapy intervention with substance-related disorders is directed at changing the behaviour and lifestyle of the individual as occupational therapists have a holistic focus on skills in occupational engagement9.

The intervention, therefore, assists the client in gaining insight into their condition and behaviour by equipping the client with relevant coping strategies and skills to improve their occupational performance in their life roles1. Occupational therapy intervention facilitates personal change by enabling the clients to identify the problems and consequences, realise their need for help, and learn to be constructive in how they live with this challenge of substance use1. Ribeiro et al10 reaffirm that occupational therapy aims to improve clients' lives by facilitating the ability to acquire the required occupational performance skills that are essential to a balanced lifestyle to cope with life effectively.

Therefore, occupational therapists play a vital role in the enhancement of the quality of life of their clients11. The intervention is therefore important in changing the habits and routines of clients' lifestyles to maintain and restore roles they lost because of substance use12. Ryan and Boland13 support the understanding that occupational therapy is well-positioned to treat substance users and is most effective and supportive when going beyond teaching of skill to prioritise occupational engagement and client-centered practice.

Twinley14302 states, "It is possible to explore the dark side of a person's occupations and gain an understanding of the underlying and associated values, interests, motivations, skills, abilities, capacities, roles, meanings and satisfactions attributed to this engagement". Following this observation, it is evident that since substance use is an occupation of choice, it is also shaped or perpetuated by the contexts that these individuals find themselves in14. Thandi and Browne15 in their study on social contextual factors on substance abuse in British Columbia (Canada) report on the social and sociopolitical factors, including health and social inequities, stigma and discrimination as perpetuating factors to substance abuse use. Additionally, Amaro et al16 affirm that societal and contextual influences on substance use are numerous and widespread. Their study findings report that societal stressors play a role in creating vulnerability to the use of substances16. These stressors range from socioeconomic and political stressors to psychosocial factors, which include disproportionately distributed population groups in communities16. Furthermore, Sibanda and Batisai17 conducted a study at a SANCA rehabilitation center in Gauteng (SA) and identified structural unemployment, poverty, fractured families and communities as contributing to the perpetuation of engagement in negative occupations as a survival strategy. Regardless of the satisfaction, it may bring to the individuals, occupations associated with substance use are not the sort that would be encouraged by the occupational therapist as they result in the deterioration of quality of life, negatively affecting life roles and occupations. This position is supported by the fact that quality of life and wellbeing from an occupational therapy perspective is understood in terms of engagement in those constructive activities that can improve the overall health of an individual! Hammel18 states that numerous qualitative studies in occupational therapy suggest that filling one's time with personally meaningful occupations restores the sense of value, purpose and quality in one's life.

Stoffel and Moyers19 emphasise the need to dedicate money and time to support research on the specific role occupational therapists play in treating people with substance use disorders. Gutman20 is of a similar opinion and emphasises a need for research to effectively treat substance use disorders in occupational therapy. The adverse effects of substance dependence on the quality of life underline the need to focus on enhancing the quality of life.

The significant cognitive, behavioral and psychological problems clients with substance dependence experience negatively affect meaningful engagement in the occupational environments and diminish the experience of quality of life8. Furthermore, their quality of life is affected when they reintegrate into their society and find that they are unable to fulfil the roles they had before their admissions. Individuals who define their quality of life by their roles and occupations find themselves in positions where they either have lost the roles or are deprived of meaningful/adequate engagement in occupations8. With the quality of life, being apparent when one lives well and feels good, problems arising from substance use can consequently affect life satisfaction3.

This article is based on a study that was conducted on the quality of life of substance abusers at a rehabilitation centre in Gauteng, South Africa. The purpose of the study was to describe the experiences of participants regarding their quality of life on their journey to sobriety. Some studies focus on how occupational therapists can support people with substance use disorders21 and the interventions used in the field22.

However, there are limited studies on the experiences of substance abusers on their quality of life after discharge. This study will provide insights that will inform the development of occupational therapy interventions that enhance quality of life. While expanding on the existing body of knowledge regarding substance use disorders in occupational therapy, the study will furthermore aid in the development of rehabilitation programmes, strategies and policies used in the field.

Literature Review

Substance use is a global concern and is rapid in its growth. Epidemiological studies of substance-related disorders are immense and provide data that is fast growing nationally and throughout the world23,16. The World Drug Report for 2018 released by United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) states that the use of substances is rapidly increasing globally. The report highlighted, for example, that the estimated global annual prevalence of drug use between 2006 and 2016 grew from 4.9% - 5.6% for ages between 15 and 64 years24. Furthermore, the UNODC statistics demonstrated that the prevalence of cannabis use among clients in Europe in 2016 showed the hig hest prevalence at 13.9%, with the United States of America at 11.6%, Africa at 6.6%, and Asia at the lowest at 2.7%. The statistics for all these regions have increased compared to 2016. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has put an enormous strain on mental health. Czeisler et al25 reports that 40.9% of respondents reported at least one mental or behavioural health condition, which included symptoms of anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, trauma and stressor-related disorders related to the pandemic having started and significantly increased substance use to cope with stress and/or emotions related to COVID-19. Furthermore, they state that 1 in 5 people over the age of 12 used illicit drugs as a coping mechanism during the hard lockdown periods25.

South Africa's National Drug Master Plan (NDMP) 2019-2024 aims to have a South Africa "free of substance abuse"26. The methods proposed to achieve this aim are reducing supply and demand of drugs for non-medical use. This is achieved by increasing harm reduction treatment, which entails the development of programmes that are directed at reducing social, economic, and health-related harm that results from substance use, controlling drugs for medical use, and preventing new drugs from entering the market. An integrated approach, including demand reduction, supply reduction, and harm reduction, will advance the realisation of this goal26. The NDMP 2019 - 2024 further states that substance use destroys communities, families and, even more concerning, the developing youth of the country26.

Moreover, a strong relationship is reported to exist between substance use and poverty, crime, reduced productivity, unemployment, dysfunctional family life, escalation of chronic diseases and premature death. This, therefore, emphasises that the quality of life of a substance user may be significantly impacted in almost all occupations. A survey done by the Central Drug Authority (CDA) of South Africa from 2019 - 2020 contains alarming findings, including the fact that the youth were addicted to drugs and alcohol by the age of 12, which in South Africa is pre-high school age.

Drugs such as 'nyaope'1, a narcotic substance typically comprising heroin, marijuana and other substances smoked as a recreational drug in some parts of South Africa and can-nabis have been commonly used. They are readily available in the local communities of South Africa, a situation that undermines the goal of the NDMP27. According to Census 2011, approximately 2 million of the 57 million South Africans were classified as substance users28. The COVID-19 pandemic has also exacerbated the mental health challenges in South Africa; the Human Sciences Research Council29 reported that 33% of South Africans were depressed, 45% experiencing anxiety symptoms and 29% experienced severe loneliness. This, therefore, led to the predisposition to substance use disorders. Naidu30 further reported that COVID-19 might lead to mental health challenges such as post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, anxiety disorders and substance use disorders. Substance use disorders result in a maladaptive pattern of use leading to significant impairment in occupations and perpetuating occupational risks.

Occupations are multi-layered because there are positive and negative occupations14. Good occupations may provide a productive, meaningful life, whereas harmful occupations offer a false sense of meaning as they limit the ability of one to grow and thrive5. Occupations include what people do daily by themselves and collectively (core occupations). These occupations structure the habits and routines that promote health31. Occupational risks (occupational imbalance, alienation and deprivation) may be evident when there is a loss of harmony between lifestyle and environment32. The result of these risk factors are the unending results of stress and can manifest as boredom, anxiety and depression which perpetuate health risk behaviors such as substance use33. According to Crowe7, the youth of South Africa who falls prey to substance use encounter an array of challenges resulting in bad occupations that predispose them to academic difficulties, health-related problems, and poor relationships - all of which may lead to youths finding themselves in the South African Juvenile Justice System. Given that drugs are readily available in South Africa, it is challenging for a diagnosed substance user to refrain from using substances and maintain sobriety. Additionally, families of youths who use drugs are adversely impacted by substance use behaviour7.

A study done in a South African community by Cloete and Ramugondo34 showed how alcohol consumption in pregnant women was not merely just "substance use", but also an occupation that provided meaning for some of these women. Cloete and Ramugondo34 further stated that one's environment and historical context shape occupations such as these. Although viewed by society as harming the wellbeing of an individual, individuals who partake in these activities seem to derive some satisfaction from them. Wilcock35 further states that a decline in quality-of-life experience is caused by occupational imbalance, occupational deprivation and occupational alienation. Occupational imbalance describes the experience of compromised health and quality of life due to being under-occupied. Occupational deprivation is a state of prolonged preclusion from engagement in occupations of necessity or meaning due to factors outside of an individual due to societal factors. Occupational alienation refers to engagement in occupations that do not satisfy personal needs related to meaning and purpose causing a significant decline in the experience of quality of life. Without engagement in purposeful occupations, abstinence and sobriety are not adequate predictors of quality of life for a substance user35. Therefore, it is of paramount importance that people with substance-related disorders are exposed to occupational therapy programmes to re-establish balance and participation in meaningful activity and ultimately enhance their quality of life1.

Occupational therapy interventions are well-positioned in supporting people with substance use disorders; however, there is limited literature on the outcomes of these interventions on the quality of life11, 14. A few studies attest to the complexity of quality of life and the difficulty in reaching a consensus in defining the concept36. The understanding of quality of life from available literature encompassed different perspectives related to life satisfaction, self-concept, health and functioning and socio-economic factors. These factors are identified as concepts of interest in occupational therapy practice.

METHODS

This study's methodology was guided by the relevant domains of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ), which are essential in reporting qualitative data37

Study Design

An explorative descriptive design embedded in the qualitative paradigm was used in this study38, 39. This research design allowed for exploration and description of the participants' quality of life40. Furthermore, the design is flexible and allowed the researcher the opportunity to describe this broad subject of substance use and quality of life38. This study aimed to explore the participants' post-discharge perceptions regarding enablers and inhibitors of their quality of life and to describe the influence of substance dependence on their quality of life prior to the rehabilitation.

Study Setting

The study was based at a 200-bed rehabilitation facility located in Gauteng, South Africa. The clients at the centre are voluntary in-patients aged 19 - 56. The centre operates under the auspices of the Department of Social Development. The centre runs a 6-week programme using a multidisciplinary team approach, including an occupational therapist, psychologist, social worker, and nurses.

Participants

The occupational therapist employed at the centre assisted with the recruitment of participants who met the inclusion criteria. The key inclusion criteria were that the participants be aged 18 years and above and be outpatients within the six weeks follow-up period and have participated in the occupational therapy programme during their admission as stipulated by the centre. Additional demographic characteristics considered were gender, educational level, occupation, and marital status.

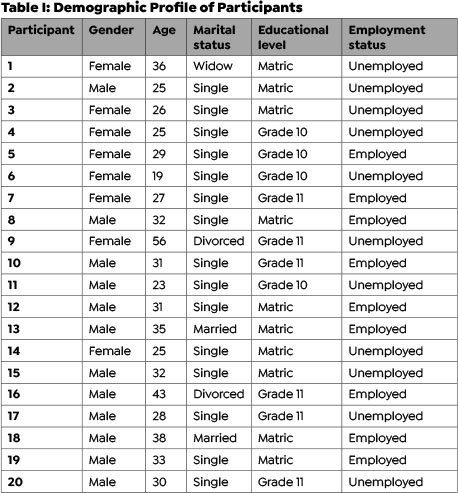

Purposive sampling, specifically the heterogeneous type, was used in this study to select participants41. Data were collected from 20 participants who consented to participate in the study and met the inclusion criteria. Participants were aged between 19 and 56, with a majority (60%) being male and 75%, single, 10% were in the educational process whilst an equal percentage of 45% were employed and unemployed. The participants used a variety of substances with 'nyaope' being the most common.

Data Collection

The researcher used one-to-one in-depth interviews, which entailed demographics in section A, Section B developed from the Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQoL): A Direct Weighting Procedure for Quality of Life Domains (SEIQoL-DW) to collect the data42 and Section C, based on intervention received by participants. The SEIQoL-DW was developed to establish the quality of life of a population or patient group and its usefulness was established in some studies43. Section B (Quality of Life) was explained to the participants as per the definition of quality of life used in the study. Based on the SEIQoL, it was possible to explore the factors related to the quality of life of substance users. The interview guide allowed the researcher to probe and follow-up on responses that required clarification. Each participant was given a pseudonym and the interviews were audio-recorded to enable the researcher to transcribe verbatim. Data collected from the participants comprised socio-demographic data, and factors enhancing and inhibiting quality of life. Due to the detailed information required from the participants, each participant was interviewed until data saturation was reached.

Data Analysis

The thematic content analysis method described by Bur-nard, Gill, Stewart, Treasure and Chadwick44 was used to analyse data. This method of analysis enabled the researcher to analyse the transcripts to understand the data. Units of meaning were gathered from the transcripts; these units of meaning were then put into categories. The researcher further combined categories where similarities were shared and then the theme was developed (e.g. Enablers to quality of life). Each participant was given a pseudonym to keep their identity confidential. This was done following the order of transcription, the first letter of the pseudonym and page number on which the transcript appears to give, for example, T1K3 where T stands for a transcript,1 for the first transcript analysed, K for the first letter of the pseudonym and 3 for the page number the unit of meaning was quoted from. The data analysis was subjected to peer review in which the methodology employed, and analysis procedures were subjected to scrutiny by experts in the field45. This process aided the researcher in ensuring trustworthiness. Trustworthiness was further ensured by confirmability by having audit trails that gave a record of how the study was conducted from its inception, through data collection, field notes, audiotapes, supervisor feedback and analysis, and concluding on the findings46- 47. To further ensure trustworthiness, the researcher was noted her thoughts and wrote them alongside the responses. Noting these thoughts limited bias and ensured reflexivity and trustworthiness 48.

Ethical Considerations

The Research and Ethics Committee at Sefako Mak-gatho Health Sciences University in Gauteng, South Africa approved the study (SMUREC/H/92/2015). Permission to conduct the study was also granted by the rehabilitation center where data were collected, and the Department of Social Development. Participants were given consent forms to read through and sign before commencing the interview and were allowed to seek clarity regarding issues pertaining to the study. They were made aware that they could withdraw from the study at any point. By so doing, the researcher ensured that participation was voluntary and informed. The researcher maintained respect and sensitivity towards the participants throughout the data collection.

FINDINGS

Description of participants

The demographic profile of the participants considered aspects like age, gender, the highest level of education, occupation, and marital status. Adult males (60%) and females (40%) with ages ranging between 19 and 56 participated in the study (See Table I adjacent). The popular substance of use was 'nyaope', followed by cannabis and other substances (KAT, rock, heroin, alcohol, nicotine and crystal meth).

Themes

Two themes emerged from the study and are illustrated in (Table II adjacent): (1) Enablers to quality of life; (2) Inhibitors to quality of life.

Theme 1: Enablers to Quality of Life

This theme shed light on the factors related to participants' quality of life; in essence, it describes the participants' perceptions of those factors which enabled their quality of life. The participants provided insights about their life satisfaction and self-concept as they shared their experiences about the occupations, they were involved in that brought about quality of life.

Employment and education were cited as occupations that brought a great quality of life for the participants as these two provided the participants with a sense of financial security. Financial security or the ability to make money came out strongly from the participants:

"It is work; it helps feed me and my family" (T5 G4).

"Financial security will help at home. (It gives) some sort of stability." (T7 L3)

The ability to provide for loved ones brought a sense of fulfilment and life satisfaction to those who were employed. Employment and education delivered the means to provide financially for loved ones and gave participants the improved life status that many of them aspired to. These two occupations thus furthermore improved the social standing of participants. People in their communities respected them because they were educated or had a job. They were not a burden to their family or society.

"...a job e ka thusa (it can help) 'cause I need money for a better life". (T17 J4)

"I really want to further my studies, because I want to make something of my life and be somebody." (T1 K3)

The second category that emerged from this theme was support - family support, intervention received and spirituality. These three factors determined a sense of self-concept for the participants. Family for the participants played a vital role in recovery by keeping them grounded and giving them a sense of belonging and worth, as evidenced by the responses below:

"...family is what I grew up with, family, we are a family we stick together, cover each other. Weekends and during the week we're together, I would go from one to the other, I was surrounded by family." (T11 D7)

". what makes me feel great is when my mother gives me support so that I can find a job." (T2 E2)

The participants identified the intervention at the rehabilitation centre, community support groups and the enhancement of activity participation as key. The participants saw the vital role of community intervention when discharged from the Centre. Activity participation, which is also critical in community occupational therapy, was reported as part of what brings about a quality of life:

"Because ja, it's just this challenge of support groups outside. Ja, it's a major thing really, and I think more people wouldn't be on drugs if there were things like that on the outside." (T7 L13)

"And there must be activities when you get out here, there must be where we can go to do some activities to learn something there, because we wasted a lot of time doing drugs and doing nothing". (T10 S11)

Spirituality is a form of support that the participants noted as an occupation that brought connectedness to a higher power. Participants drew strength and peace from the higher power and felt that there was a sense of resolution and change that could be found in that connectedness:

"Finding inner peace with God 'cause there are people coming in here [Centre] speaking to us about God" (T1 K7). "...also going to church, so it [substance use behaviour] wants a person to go to churches to change." (T4 P8)

The third category in this theme was parenting. The majority of the participants that were interviewed were parents. They found meaning and purpose in this role because it required responsibility to their children. They realised that substance use made them unable to perform this role effectively, yet this role brought so much meaning to them.

"I want to be a good mother to my children like I used to be 'cause that is important" (T1 K3).

"I neglected my child as a parent, and stopped giving him motherly love, I need to stop and be a good mother to my child, 'cause he needs me." (T6 B3).

Leisure participation was the last category of this theme. Leisure and recreation were reported as enhancing the quality of life of these participants because they were able to find themselves relaxed and learning something new, a skill that brought meaning.

"I would say gardening, I love gardening. It helps to keep my mind off stuff". (T9 A2)

"And there must be activities when you get out here, there must be where we can go to do some activities, to learn something there." (T10 S11)

It is therefore evident in this theme that participants drew on roles and occupations as what brought meaning into their lives. This is what brought about quality of life for the participants.

Theme 2: Inhibitors to Quality of Life

Participants reported on factors that hindered them from attaining optimal quality of life before admission in this theme. This brought to the researcher's attention how substance dependence affected the participants' quality of life. It was vital for the researcher to explore this with the participants, as it would aid them to find quality of life.

The first category of this theme was that of emotions, and from the data, the researcher established that the emotions were all negative. These emotions hindered the participants from experiencing quality of life, thus impacted negatively on their emotional wellbeing. Some of these emotions were stress-related, resulting in grief, anxiety, shame, failure, anger and regret. These emotions came at different times of the participants' dependence journey. Some experienced the emotions before commencing substances, meaning that the experienced emotion led them to use substances as relief or "cry out." For some of the participants, the emotions came after exposure to drug dependence:

"...in 2010 after finishing my matric I did not have money to study further, it stressed me and that is when I started using nyaope." (T3 M4)

"I tried my best and I even failed in that [parenting role] (eyes watery, as if about to cry) so I lost a lot of contact with my children." (T1 K4)

The second category was that of family breakdown. The family systems of the participants broke down because of their substance dependence. The participants shared how the loss of trust toward them from their family affected them. This lack of trust further led to poor relationships with their family members and in some cases, led to ineffective communication or estrangement. The self-worth they once derived from their family had also been lost due to negative behaviours emanating from substance dependence. Participants also cited poor parenting and poor communication due to substance dependence as they could no longer fulfil the parenting role and communicate effectively.

"My parents don't trust me anymore; even my sisters don't trust me anymore because of this drug". (T12 T6)

"It [substance] has affected me because I'm irritable then next I don't want to speak to them [family], the next I'm high and it's killing my mother to see me like that, but I think I'm fine and sometimes I don't even want to be with them [family] and just kept going for months on end. And it's [substance use] just debilitated the whole relationship." (T7 L6)

The third category of this theme was that of behaviours that influenced quality of life negatively, namely avolition of drug dependence, manipulation, and experimentation. Participants recognised these behaviours as having inhibited them from achieving quality of life. Concerning avolition, a key factor in occupational therapy, participants lacked the drive and energy to participate in their occupations as they were fully consumed by the "new-found" occupation of drug dependency. Participants found themselves having to use substances to cope with the demands of their occupations. The participants also manipulated their family, friends and colleagues for them to pursue their substance dependence. For many of them, experimentation was the behaviour that caused the start of the substance dependence journey.

"It [substance use] did affect me a lot, yoh! 'Cause where I used to work, I was working as a government employee, it means I was helping the community about these drugs. So I was not able to finish up my contract. I ended up leaving my work in the middle". (T5 G5)

"It has affected me a lot, because you can't do something else if you don't have the drug in yet, so I felt I need the drug every day to help me in life.". (T1 K5)

Socio-economic circumstances posed a barrier to the participants in their recovery towards sobriety. The poor socio-economic circumstances that the participants found themselves in inhibited their experience of a quality of life. Unemployment and poor finances were robust features in this category. The lack of money or a way of making money precipitated and perpetuated the participants' drug use. Emanating from this also was the behaviour itself of substance use, because when the participants found employment, their income was directed at buying and using more drugs. The quotes below attest to this:

"Uhm, not having a job I get bored and have nothing to do and there is no support group and finances." (T2 E5)

"Yes, I would be able to make 300% profit, but I did not see progress because of my addiction". (T8 Q4)

DISCUSSION

The participants' responses were mainly around their occupations and experiences of quality of life. Participants described their family relations as critical to their quality of life. They reported that their family members' opinions and perceptions of them defined their quality of life. The family included the immediate family they lived with, and for some, it was the family they had estranged themselves from because of their substance use behaviour. As De Maeyer et al49 highlighted, family support and good family structure tend to influence the quality of life for participants significantly. Navabi et al50 further report in their study that erosion of quality of life does happen to the individual using substances and the entire family unit. For this reason, their study found that the quality of life of the family was a strong determinant of the individual's quality of life and vice versa. The same finding applied to this study.

Employment was also a factor that came out strongly from the participants, as they indicated that with employment came the financial advantage that maintained their lifestyle and that of their family; hence, it brought about quality of life for them. Schnohr et al51 conducted a study which showed a relationship between educational attainment, employment and substance use. They found that individuals with low or no educational attainment and unemployed showed lower quality of life. Regarding the education factor, it was mainly because the level of education allows them the opportunities to better their lives and seek better employment prospects51. It is evident in this current study that jobless participants with low educational qualifications had an inhibited quality of life.

Participants also perceived family support, involvement in support groups and spirituality to enhance their quality of life. Participants felt a sense of calm and hope regarding their spiritual affiliation. Heinz et al52 conducted groups that discussed the influence of spirituality on substance use behaviour. In their study, they reported that most participants agreed that making spirituality a part of formal treatment assisted in their recovery52. The NA and AA groups use a 12-step programme that holds spirituality in high regard53. In this study, participants identified support groups (Narcotics Anonymous, South African National Council on Alcoholism)53as an essential part of their recovery upon discharge. One limitation that they mentioned was that their population was deeply spiritual. Spirituality, however, does not necessarily have to do with the connection to a higher power only; spirituality is also an integral part of an individual's identity and well-being54. The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework recognises that spirituality can influence the clients' ability to cope, rehabilitate, connect with others and ultimately enhance quality of life54 given that it reduces distress and enhances health and recovery. Jones et al55 reported that occupational therapists play a vital role in addressing the interferences in wellbeing and quality of life by facilitating the spiritual coping strategies for clients to be restored and their sense of meaning and purpose gained. "Therefore, spirituality is considered as one of the significant elements of the holistic approach that promotes the health, quality of life and wellbeing of individuals, groups and communities in the South African context"56 (p.16).

Concerning leisure participation, the participants viewed it as a means of learning a new skill and using their time more wisely. Chen and Chippendale57 report that leisure should be viewed as an end goal of intervention in the occupational therapy practice, as this will enhance the health and wellbeing of clients. Furthermore, Mayasich and Tyce58 also report on the importance of leisure as an occupation that enhances health and quality of life. This current study argues that occupation is vital to the substance user in enhancing the experience of quality of life.

The participants identified the inhibitors of quality of life as related to negative emotions that resulted from their substance use behaviour. Fooladi et al59 reported in their study how an unhealthy emotional status exacerbated substance use behaviour and reduced quality of life. The negative emotions reported by participants in this current study made them experience a lack of control, leading them to use substances to numb the negative feelings they had.

The behaviours that arose from substance use behaviour inhibited the participants from experiencing a quality of life. Avolition, which was indicated by participants, reduced quality of life significantly. While dependent on a drug, the participants had neither drive nor purpose to participate in the various occupations and this caused a reduction in functioning. A study done by McLellan et al60 reported that drug dependence is mainly a social problem that produces functional problems, influencing an individual's day-to-day functioning. In another study by Denis8, substance dependence impacted quality of life since the results showed that mental functions were impacted negatively, causing a barrier to the experience of quality of life.

Through the misuse of financial resources, participants experienced a reduction in their quality of life. The participants reported this as money wrongfully used to sponsor their addiction at the expense of their financial responsibilities in everyday life. Participants who lost their jobs found that lack of income drove them to substance use, leading to the inability to support themselves and their families, ultimately leading to a reduced quality of life experience.

It was therefore evident in the study that the factors that determined quality of life for the participants were their occupations (e.g., employment and education, social and leisure participation), and support (family support, intervention, spirituality). Occupational therapy intervention can contribute to enhancing the quality of life among substance users where family support and support groups aim to improve life satisfaction, self-concept, motivation and insight as well as to re-establish the roles of the participants to have quality of life after being discharged from the Center. Furthermore, the barriers to quality-of-life stem from the emotional status of the participants, their family dynamics (social interactions) and behaviours. It is therefore recommended that occupational therapy address the emotional wellbeing and motivation of substance users.

The limitations of the study dwell in the management and analysis of data, which was large in volume, and therefore time-consuming for the researcher. Another limitation was the challenge the researcher encountered in finding literature on quality of life in occupational therapy. Occupational therapy practice should focus on addressing the contextual factors leading to substance use to establish a holistic, context-specific and client-centred approach.

CONCLUSION

Literature has shown that substance use indeed affects an individual's life in many different ways. This study brought to the surface the participants' experience of the enablers and inhibitors of quality of life. Furthermore, it demonstrated the understanding that substance use inhibits quality of life because of the negative emotions that individuals with substance use disorders encounter. The participants also reported family breakdown, negative behaviours and poor socio-economic status as inhibitors of their quality of life in the occupations they found themselves in. The participants also shared the enablers of their quality of life, which included employment and education, which afforded them the ability to provide for their loved ones and maintain a good socio-economic status. Leisure participation enhanced quality of life as it provided a sense of relaxation and meaning to the individuals. Support in terms of family, intervention (support groups and occupational therapy intervention) and spirituality enhanced their quality of life because it provided satisfaction and wellness.

Therefore, the study found that participants described enablers and inhibitors to their quality of life, which influenced engagement in their occupations and experience of independence. The occupations (activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, education, work, leisure, social participation, play and rest and sleep) in the field of occupational therapy form part of the occupational therapy domain. Therefore, the occupational therapist's role is of great importance when it comes to the rehabilitation of persons with substance use disorders.

Quality of life is also what occupational therapy strives toward for their clients. As such, the skills of occupational therapists are important for the full recovery of the client to sobriety. Therefore, the occupational therapist needs to provide a holistic approach to the individual's treatment programme. The intervention programme focusing on the enablers of quality of life will ensure quality of life is addressed in therapy. Therefore, engagement in occupation is as important as the engagement itself, therefore when these occupations are not engaged in, an individual will be deprived of quality of life, which may lead to ill health.

Recommendations can therefore be made for more effective programmes in the treatment centers. These programmes should use an inter-professional collaboration that is impactful in holistically addressing the client's needs. Effective outpatient programs are essential for clients to be exposed to various concepts like prevention strategies, psychoeducation for the caregivers/family, and the critical acquisition of life skills. Aftercare programmes are essential in establishing successful reintegration into society and further assist in relapse prevention.

Author contributions

Marusa L Lefine and Ramadimetja A Lesunyane conceptualised and operationalised the research project. They collected and analysed the data and wrote the journal article.

Conflicts of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare

REFERENCES

1. Crouch R, Wegner L. Substance Use and Abuse in Occupational Therapy in Psychiatry and Mental Health. 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118913536.ch28 [ Links ]

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5 (R). 5th ed. Arlington, TX: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.190656 [ Links ]

3. Moreira T de C, Figueiró LR, Fernandes S, Justo FM, Dias IR, Barros HMT, et al. Quality of life of users of psychoactive substances, relatives, and non-users assessed using the WHOQOL-BREF. Cien Saude Colet. 2013;18(7):1953-62. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-81232013000700010 [ Links ]

4. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process-fourth edition. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2020;74 (Supplement_2):7412410010p1. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74s2001 [ Links ]

5. Brown HV, Hollis V. The meaning of occupation, occupational need, and occupational therapy in a military context. Phys Ther. 2013; 93:1244-1253. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20120162 [ Links ]

6. Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Schell BAB. Willard& Spackman's Occupational Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 2003. ISBN:9781975106584 [ Links ]

7. Crowe A. Drug identification and testing in the juvenile justice system: (380652004-001). PsycEXTRA Dataset. American Psychological Association (APA); 1998. https://doi.org/10.1037/e380652004-001 [ Links ]

8. Denis C. Does substance use affect quality of life? Factors associated with quality of life in alcohol-dependent and alcohol and cocaine dependent patients. Treatment Research Center, University of Pennsylvania, United States; 2012. https://nida.nih.gov/international/abstracts/does-sub-stance-use-affect-quality-life-factors-associated-quality-life-in-alcohol-dependent-alcohol [ Links ]

9. Amorelli CR. Psychosocial Occupational Therapy Interventions for Substance-Use Disorders: A Narrative Review. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 2016; 32:2, 167-184, DOI: 10.1080/0164212X.2015.1134293 [ Links ]

10. Ribeiro J, Mira E, Lourenço I, Santos M, Braúna M. The intervention of Occupational Therapy in drug addiction: a case study in the Comunidade Terapêutica Clínica do Outeiro - Portugal. Intervenção da Terapia Ocupacional na toxicodependência: estudo de caso na Comunidade Terapêutica Clínica do Outeiro - Portugal. Cien Saude Colet. 2019;24(5):1585-1596. Published 2019 May 30. doi:10.1590/1413-81232018245.04452019 [ Links ]

11. Letts L, Edwards M, Berenyi J, Moros K, O'Neill C, O'Toole C, et al. Using occupations to improve quality of life, health and wellness, and client and caregiver satisfaction for people with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65(5):497-504. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.002584 [ Links ]

12. Bell T, Wegner L, Blake L, Jupp L, Nyabenda F and Turner T. Clients' perceptions of an occupational therapy intervention at a substance use rehabilitation center in the Western Cape. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. [Internet]. 2015 Aug [cited 2022 Feb 21] ; 45( 2 ): 10-14. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2310-38332015000200003&lng=en. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/V45N2A3. [ Links ]

13. Ryan, DA and Boland, P. A scoping review of occupational therapy interventions in the treatment of people with substance use disorders. Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2021, 49(2), 104-114. DOI:10.1108/IJOT-11-2020-0017 [ Links ]

14. Twinley R. The dark side of occupation: a concept for consideration. Aust Occup Ther J. 2013;60(4):301-3. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12026 [ Links ]

15. Thandi MKG, Browne AJ. The social context of substance use among older adults: Implications for nursing practice. Nursing Open. 2019;6: 1299-1306. DOI:10.1002/nop2.339. [ Links ]

16. Amaro H, Sanchez M, Bautista T, Cox R. Social vulnerabilities for substance use: Stressors, socially toxic environments, and discrimination and racism. Journal of Neuropharmacology. 2021;108518. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021;108518 [ Links ]

17. Sibanda A, Batisai K. The intersections of identity, belonging and use disorder: struggles of male youth in post-apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2021;26(1):143-157. http://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2021.1899945 [ Links ]

18. Hammell KW. Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of daily life. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71(5):296-305. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740407100509 [ Links ]

19. Stoffel VC, Moyers PA. An evidence-based and occupational perspective of interventions for persons with substance-use disorders. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58(5):570-86. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.58.5.570 [ Links ]

20. Gutman SA. Why addiction has a chronic, relapsing course. The neurobiology of addiction: Implications for occupational therapy practice. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2006;22(2):1-29. https://doi.org/10.1300/j004v22n02_01 [ Links ]

21. Godoy-Vieira, A., Soares, C.B., Cordeiro, L. and Sivalli Campos, C. "Inclusive and emancipatory approaches to occupational therapy practice in substance use contexts", Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018, Vol. 85 No. 4, pp. 307-317, https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417418796868. [ Links ]

22. Lakshmanan, S. "Occupational therapy structured activities for substance use recovery", World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin. 2014, Vol. 70 No. 1, pp. 30-31. doi: 10.1179/otb.2014.70.1.008. [ Links ]

23. Merikangas KR, McClair VL. Epidemiology of substance use disorders. Hum Genet. 2012;131(6):779-89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-012-1168-0 [ Links ]

24. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Introduction [Internet]. United Nations Publications; 2018. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18356/d29e3f27-en [ Links ]

25. Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. (2020). Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 69(32), 1049-1057. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [ Links ]

26. National Drug Master Plan 2019 - 2024 (2018). [Internet]. Available from: <http://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_docu-ment/202006/drug-master-plan.pdf> [Accessed 15 July 2021]. [ Links ]

27. Lubaale EC, Mavundla SD. Decriminalisation of cannabis for personal use in South Africa. Afr Hum Rights Law J [Internet]. 2019;19(2). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2019/v19n2a13 [ Links ]

28. South Africa (republic) - census, standards & statistics. Foreign Law Guide. Brill; 2015. https://doi.org/10.1163/2213-2996_flg_com_172160 [ Links ]

29. Human Sciences Research Council . (2020). HSRC responds to the COVID-19 outbreak. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/11529/COVID-19.pdf [ Links ]

30. Naidu, T. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 559-561. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000812 [ Links ]

31. Whiteford, G., & Townsend, E. (2011). Participatory occupational justice framework (POJF 2011): Enabling occupational participation and inclusion. In F. Kronenberg, N. Pollard, & D. Sakellariou (Eds.), Occupational therapy without borders: Learning from the spirit of survivors (pp. 6584). London: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN: 9780702031038 [ Links ]

32. Fieldhouse, J. Occupational Science and Community Mental Health: Using Occupational Risk Factors as a Framework for Exploring Chronicity. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000, 63(5), 211-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260006300505 [ Links ]

33. Wilcock AA (1993a) A theory of the human need for occupation. Journal of Occupational Science: Australia, 1(1), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.1993.9686375 [ Links ]

34. Cloete LG, Ramugondo EL. "I drink": Mothers' alcohol consumption as both individualised and imposed occupation. S Afr J Occup Ther. 2015;45(1):34-40. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45no1a6 [ Links ]

35. Wilcock AA. Occupation for health: Re-activating the regimen sanitatis. J Occup Sci. 2001;8(3):20-4. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2001.10597271 [ Links ]

36. Chaturvedi, S.K., Muliyala, K.P. The Meaning in Quality of Life. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 3, 47-49 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-016-0069-2 [ Links ]

37. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research. PsycTESTS Dataset [Internet]. American Psychological Association (APA); 2007; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/t74064-000 [ Links ]

38. Yin R. How to do better case studies: (with illustrations from 20 exemplary case studies). In: The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2014. p. 254-82. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483348858.n8 [ Links ]

39. Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among Ave approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2012. ISBN 978-1-4129-9530-6 [ Links ]

40. Lambert VA, Lambert CE. Qualitative Descriptive Research: An Acceptable Design. PRIJNR [Internet]. 1 [cited 2021Sep.14];16(4):255-6. Available from: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/PRIJNR/article/view/5805 [ Links ]

41. Etikan I. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am j theor appl stat. 2016;5(1):1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11 [ Links ]

42. SEIQoL-DW: Schedule for the evaluation of individual quality of life-direct weighting. In: Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014. p. 5742-5742. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_103690 [ Links ]

43. Becker G, Merk CS, Meffert C, Momm F. Measuring individual quality of life in patients receiving radiation therapy: the SEIQoL-Questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(7):2025-2030. doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0661-4 [ Links ]

44. Burnard P, Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Analysing and presenting qualitative data. Br Dent J. 2008;204(8):429-32. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292 [ Links ]

45. Kelly J, Sadeghieh T, Adeli K. Peer Review in Scientific Publications: Benefits, Critiques, & A Survival Guide. EJIFCC. 2014;25(3):227-243. Published 2014 Oct 24. PMCID:PMC4975196 [ Links ]

46. de Kleijn R, Van Leeuwen A. Reflections and Review on the Audit Procedure: Guidelines for More Transparency. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. December 2018. doi:10.1177/1609406918763214 [ Links ]

47. Carcary, M. The Research Audit Trail: Methodological Guidance for Application in Practice. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. 2020; 18(2), pp. 166-177, available online at www.ejbrm.com https://doi.org/10.34190/JBRM.18.2.008 [ Links ]

48. Haynes K. Reflexivity in qualitative research. In Cassell C, Symon G, editors, The Practice of Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges. SAGE. 2012 https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526435620.n5 [ Links ]

49. De Maeyer J, Vanderplasschen W, Lammertyn J, van Nieu-wenhuizen C, Sabbe B, Broekaert E. Current quality of life and its determinants among opiate-dependent individuals five years after starting methadone treatment. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(1):139-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9732-3 [ Links ]

50. Navabi N, Asadi A, Nakhaee N. Impact of drug abuse on family quality of life. Addict Health. 2017;9(2):118-9. 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5742419/PMID29299215;PMCID: PMC5742419 [ Links ]

51. Schnohr C, H0jbjerre L, Riegels M, Ledet L, Larsen T, Schultz-Larsen K, et al. Does educational level influence the effects of smoking, alcohol, physical activity, and obesity on mortality? A prospective population study. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32(4):250-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/140349480403200403 [ Links ]

52. Heinz AJ, Disney ER, Epstein DH, Glezen LA, Clark PI, Preston KL. A focus-group study on spirituality and substance-user treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(1-2):134-53. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826080903035130 [ Links ]

53. Sussman S, Arriaza B, Grigsby TJ. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug misuse prevention and cessation programming for alternative high school youth: a review. J Sch Health. 2014;84(11):748-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12200 [ Links ]

54. Humbert T, editor. Spirituality and occupational therapy: A model for practice and research. AOTA Press; 2019. https://doi.org/10.7139/2017.978-1-56900-451-7 [ Links ]

55. Jones J, Topping A, Wattis J and Smith J. A Concept Analysis of Spirituality in Occupational Therapy Practice. Journal for the Study of Spirituality. 2016;6:1, 38-57. http://doi.org/10.1080/20440243.2016.1158455 [ Links ]

56. Mthembu TG, Wegner L, Roman NV. Spirituality in the occupational therapy community fieldwork process: A qualitative study in the South African context. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. [Internet]. 2017 Apr [cited 2022 Feb 17] ; 47( 1 ): 16-23. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2310-38332017000100004&lng=en.http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3a4. [ Links ]

57. Chen SW, Chippendale T. Leisure as an End, Not Just a Means, in Occupational Therapy Intervention. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018;72(4):p1-5. doi:10.5014/ajot.2018.028316 [ Links ]

58. Mayasich O and Tyce A. Using Leisure as a Therapeutic Activity to Enhance Health, Well-Being, and Quality of Life among Long Term Care Residents. (2019). Occupational Therapy Capstones. 425. https://commons.und.edu/ot-grad/425. [ Links ]

59. Fooladi N, Jirdehi R, Mohtasham-Amiri Z. Comparison of depression, anxiety, stress and quality of life in drug abusers with normal subjects. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;159:712-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.459 [ Links ]

60. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-95. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.13.1689 [ Links ]

Submitted: 1 September 2021

Reviewed: 29 April 2022

Revised: 23 May 2022

Accepted: 4 August 2022

Corresponding author: Lebogang Lefine lebo.moti@outlook.com

EDITOR: Pragashnie Govender

DATA AVAILABILITY: Upon reasonable request from corresponding author.

FUNDING: Self-funded - The authors received no funding for this research

1 Nyaope is mixture of low-grade heroin, cannabis products, antiretroviral drugs and other materials added as bulking agents.