Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.52 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2022/vol52n3a6

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Promoting the play of children with autism spectrum disorders: Contributions of teachers and caregivers

Pamela GretschelI, *; Nyaradzai MunambahII, *; Kayla CampodonicoIII, *; Marcelle JacobsIV, *; Ntwanano MabasaV, *; Aphiwe MasinyanaVI, *; Hannah NassenVII, *; Tinhlalu NghuleleVIII, *

IDivision of Occupational Therapy, University of Cape Town, South Africa http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7890-3635

IIUniversity of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0957-3783

IIIOccupational Therapist, Eastern Cape Department of Health, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2801-7122

IVOccupational Therapist, Eastern Cape Department of Health, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5256-2852

VEducation Therapist, Gauteng Department of Education, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3853-3964

VIOccupational Therapist, Eastern Cape Department of Health, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4560-7327

VIIEducation Therapist, Western Cape Department of Education, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5140-8968

VIIIEducation Therapist, Western Cape Department of Education, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9914-8907

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The play of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be negatively impacted on by difficulties linked to their diagnosis, however, people present in the children's contexts can positively influence their engagement in play. Teachers and caregivers, being significant role players participating in the contexts of children, are well positioned to promote the engagement of children in play.

RESEARCH DESIGN: This paper reports the findings of a qualitative descriptive study which employed semi-structured interviews to explore and describe the ways in which three teachers and two caregivers supported the engagement of children with ASD in play

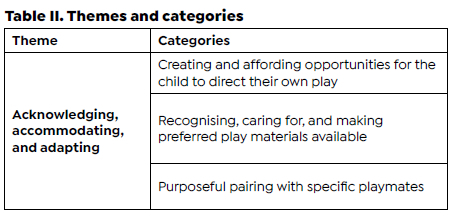

FINDINGS: The theme, Acknowledging, Accommodating, and Adapting, describes how the caregivers and teachers supported the play of children with ASD. The multiple ways in which they promoted the children's engagement in play is unpacked in the following categories: creating and affording opportunities for the child to direct their own play; recognising, caring for, and making preferred play materials available, and purposeful pairing with specific playmates.

DISCUSSION: Caregivers and teachers have experiential knowledge of the play interests and the ways in which children with ASD play. They skilfully draw on this knowledge to implement an array of strategies to promote the play of children with ASD.

CONCLUSION: Given their instrumental role in supporting the play of children with ASD, occupational therapists should be encouraged to continue to partner with and learn from care-givers and teachers. This will align with collaborative practice and enhance the development and implementation of relevant and sustained interventions focused on the occupation of play in children with ASD.

Keywords: play and ASD, self-directed play, preferred play material, play promotion, scaffolding play.

INTRODUCTION

Play is primary occupation of children and occupational therapists aim to promote children's participation in play in order to advance their development, health and well-being1. Playfulness refers to a child's approach and disposition to play and is determined by the child's skill in demonstrating the four elements of playfulness: intrinsic motivation; internal control; the freedom to suspend reality; and framing2.

A child's play should be explored in context to identify how various human and non-human factors in these contexts, shape their engagement in play3,4. A structured context is one in which there is adult facilitation and play is shaped by a set of guidelines for children to follow3. In contrast, unstructured play environments are child-centred, familiar to the child and their interests, responsive to the cues which the child initiates and supportive of the child's cognitive development, independence and playfulness3. Ideally play needs to be framed in an unstructured way so that the child can engage with flexibility and spontaneity5. Some children may however require more assistance from people in their environments to promote their engagement in play. One such group, are children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who are often reliant on people in their environments to promote their play and playfulness5,6.

ASD is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition7 characterised by rigid ways of thinking and a limited range of interests8. Children with ASD experience challenges with engagement in play9. They tend to be less playful than their typically developing (TD) counterparts and their play has a repetitive element10. Prominent people present in the contexts of children are caregivers and teachers, who spend a lot of time with children and thus have the potential to shape their engagement in play through altering and adapting the play environments of the child in ways that create opportunities for sustained engagement in play6,11,12. Gaining information from these significant people in the lives of children has the potential to build on the collaborative intent of occupational therapy practice13 and generate knowledge which can inform the development of family-centred occupational therapy play-based interventions for children with ASD.

Previous research describes various strategies used by caregivers and teachers to promote the play of children with ASD. Román-Oyola et al(2018)14 described how caregivers sought out interactions and play activities that were intrinsically motivating for their child. They deliberately created play opportunities that the child was interested in doing and immersed themselves in the type of play the child had already established. Parent education, modification of play materials or environments and modelling an adult, peer, or a video, were beneficial strategies used by the caregivers to improve the play participation of children with ASD15.

While the above research findings document some of the strategies to promote play, it is important to recognise that play differs in context16 and in turn, the strategies that are used to promote play engagement, may also differ across contexts. Promoting play in context, calls for perspectives from the caregivers and the teachers living in these different contexts.

In this paper, we present the findings of a study which explored and described how caregivers and teachers living in Cape Town promote the play of children with ASD, highlighting their consideration of the environmental factors (play space, play objects and playmates) that supported and/or hindered the play of the children with ASD. The strategies used by the caregivers and teachers are described in relation to the method of scaffolding presented in Vygotsky's17 social cultural theory of the zone of proximal development. This theoretical framework was selected after an inductive approach to analysing the data, to help with interpreting the findings. Vygotsky introduced the concept of the zone of proximal development to describe the actual development and the potential development of the child. Scaffolding refers to the actions which people in the child's context take to support the child to develop in line with their developmental trajectory17. Scaffolding in relation to the child's play would involve systematically adjusting, first increasing, and then withdrawing the amount of assistance offered to a child to initiate and sustain their engagement in play17.

METHODOLOGY

The ways in which caregivers and teachers promote the engagement of the child with ASD in play is a poorly understood phenomenon in South Africa, as evidenced by paucity of literature in this area. A qualitative descriptive research design (QD) adopting an exploratory approach was thus well suited to gain insights from the participants about the strategies and approaches they used18. Participants were purposely selected in line with the below inclusion criteria, due to their knowledge and experience of the nature of the children's play and their perspectives of their role in promoting the play of children between three and eight years of age.

Teachers were the primary educators of children (spending no less than 15 hours per week with the children) and who had interacted with the children for at least three months (one school term).

Caregivers were those persons who provided the most consistent form of care to the children (spending no less than 48 hours per week with the children).

Convenience and snowball purposive sampling techniques were used to recruit participants. The final sample consisted of five participants (three teachers and two caregivers). Table I (page 45) gives an overview of their demographics. The three teachers worked in one inclusive primary school in a middle to high income suburb in Cape Town. The Blue school (pseudonym) adopts a play-based curriculum to accommodate the diverse learning needs of both typically developing children and children with various barriers to learning between the ages of 0-7 years of age. The care-givers who took part in the study were both mothers of a male children with ASD. Both lived in Cape Town and shared similar demographic characteristics.

A total of five (four face-to-face and one telephonic) semi-structured interviews were conducted with the participants at a time and place convenient to them. The development of the questions presented in the interview guides was informed by play theory8 and included questions encouraging caregivers and educators to share how they promoted the engagement of the children in play in line with their consideration of play space, play materials and play mates. A pilot study was undertaken to ensure the questions were clearly formulated and related to the study aim and objectives. An occupational therapist supervising final year occupational therapy students working with children with ASD, and one caregiver of a child with ASD, reviewed the interview guide. They suggested that two separate interview guides be created, i.e., one for the caregivers and one for the teachers, and they also advised on the inclusion of further probing questions. These suggestions were included in the final versions of the caregiver and teacher interview guides.

Data were analysed thematically, drawing on an inductive approach. The audio data were transcribed and checked for accuracy by research pairs. The transcribed data were then reviewed extensively to generate codes manually in a code book. Codes were then grouped together in categories. The categories were then collated and organised into two themes. The first theme, Playful, but on their own terms, was generated from the descriptions the caregivers and educators shared about how the children with ASD played. These descriptions reflected their detailed understanding of the diagnostic features of ASD and the impact of these features on the play engagement of the children. The second theme Acknowledging, accommodating and adapting which is the focus of this article, details the specific ways in which the caregiver and educators promoted the engagement of the children with ASD in play. This theme is foregrounded to acknowledge the significant contributions which caregivers and educators make to promoting the engagement of children with ASD in the occupation of play. The following strategies were applied to ensure trustworthiness: member checking with the participants to ensure an accurate and complete account of their interviews was captured, gaining, and presenting a rich description of the participants and their contexts, peer reviewing by a skilled research supervisor, and maintaining a detailed audit trail.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town (Ethical clearance number 2018/0838). Ethical principles of informed consent, privacy, and beneficence were adhered to throughout the research process. Each potential participant was adequately informed about the study process and their right to abstain or withdraw from participation without reprisal. To ensure privacy, all data collected were held in confidence and pseudonyms were used to ensure anonymity. Furthermore, personal information which could be linked back to the participants was not presented. The caregivers and teachers were assured that the focus of the study was not evaluative of their performance but rather, an appreciation of their strengths in promoting the play engagement of children with ASD.

FINDINGS

The theme Acknowledging, accommodating and adapting and its associated categories presented in Table II (below) describe the various ways in which caregivers and teachers promoted the play of the children with ASD.

Category one: Creating and affording opportunities for the child to direct their own play

Participants acknowledged the need of the children to be in control of the focus and flow of their play. They shared how they created and encouraged opportunities for the children to direct their own play by adopting a non-directive approach and following the lead of the children during play. They also recognised the positive impact of this approach on sustaining the children's engagement in play.

"So I don't force him to play with anyone or play a certain game...and if he's okay then we do it and if he doesn't want to do it, I, I don't let him do it." (Tamara)

"...they just go where they go and we follow..." (Sam)

"The benefit is to teach him independent play and my son, it (play) relaxes him, it (play) unwinds him so they kind of like de-stress." (Michelle)

Participants facilitated the autonomy of the children, encouraging the children to choose the play activities that they wanted to engage with.

"So, I will allow him to choose what play he wants to, whether he wants to play with the TV or play with the equipment." (Michelle)

"So, whatever it is that they like, they can go and fetch it and then go play on their own, if they want to do that" (Sam)

A wide variety of different types of play materials were made available in the play spaces to ensure that the children had options that they could freely choose from.

"we have our educational toys, we have our story books, we have our art materials, we have uh, for the fine motor, we have objects for children that's very uh, uh, weak in their fine motor we have our own little um, um, toys that we work with them, so ja, we have, we have quite a lot of toys for them, so we see to all, to all the kids." (Allison)

"They can play with anything that they like. There's a little (feely) box that we have, so whenever they feel the need to go and play with it or take it out, and then they can go and fetch it." (Sam)

Category two: Recognising, caring for, and making preferred play materials available

In line with affording opportunities to play through adopting a child-led approach and structuring the environment to create opportunities for the children to choose what to play, participants also drew on their knowledge of the specific play material preferences of the children and prioritised creating opportunities for the children to play with the play materials aligned with their interests.

"So, whatever he loves we have at our disposal..." (Candice)

"Okay um, I mentioned too that I cannot plan so it's basically what comes to mind and what I know your (child), you know like(s), like, the park example or kicking the ball or just leaving him and he's now lately into marbles, like he's got something new now, marbles is like now his in thing" (Tamara)

"I ask the assistant just to take him out. Just go and play outside. Go and run. Go and jump on the trampoline. Go and play in the sandpit because he loves to play." (Candice)

"...so, when you have a very big book and you start with music which he loves then Shaun will take note of that book, see, so he loves, uh, Shaun actually learns through music as well, he loves music. I'll put stuff there that I know that he likes" (Allison)

Candice and Sam drew on what they had learnt about the children's fondness for various types of sensory play and set up their contexts with play materials which afforded the children the chance to engage in multi-sensory play.

"...the children learn through their senses and we are taught that, so everything that we do in the class, we make sure that we are, they are engaged in activities that they can touch, feel, smell, listening as well." (Candice)

"And we make it colourful and they know where the resources are, and inviting and attractive as possible as we can. It has to be colourful, adorable, it must be attractive to them so that they might want to go play." (Sam)

Michelle recognised the play materials her son enjoyed playing with at school and provided these play materials in the home context.

"I put up a white board for him to write which he was very excited at the beginning because he does it at school." (Michelle)

The children's intense interest in and preference for particular play materials led to the participants seeking out play materials which were durable and going to great lengths to care for these play materials.

"So the things that is set out is durable... " (Candice)

"Like I know the ball, where they need to sit on the ball just to strengthen their core, they can't sit still, that we don't leave out because then the other children will play with it also. So, we also want to keep their resources for them. You know, that is for them, and we have, like in movement, I'll take it out and everybody can experience it. But for them specifically, we keep it separate for them so that the other learners know that, you know, these are the things that they play." (Sam)

Category three: Purposeful pairing with specific playmates

Caregivers and teachers strategically promoted the social play of the children with ASD by purposefully pairing the children with playmates who due to their own skill in play or age, were well positioned to support the engagement of the children with ASD in social play. The educators and caregivers also involved themselves in the play activities of the children as playmates, to initiate and sustain their engagement in play.

"You know, I will have two of my strong boys playing with him...because they talk more, and they, and they, they play with the ball so it's not that rough games that they normally play and Shaun likes these two boys to play with, so they you know he likes the ball and then they will show him what else to do, so when we do a movement he will show, they will show him, so he will follow these boys as they are playing." (Allison)

Sam described how the children with ASD often preferred to play with younger playmates. She drew on this preference, encouraging them to play with younger playmates.

"But you'll find that sometimes they adapt more to theyounger children. You know, because they feel, that there are certain things that they can do that's on the younger level whereas they struggle. So our motto is that rather be leaders in a younger group than struggle and tag along in the older group. We mostly, we encourage them to play with the younger ones also." b (Sam)

Sam described how the children with ASD did not engage with other children in the absence of their preferred playmates. To address this, she encouraged other children in the class to befriend and play with the children.

"They (the children with ASD), there are the ones that plays with just specific children. So when the child is not here, they feel lost, but then you encourage them to play with others or encourage the friends just to take that one along because their friend is absent today." (Sam)

The caregivers and teachers also strategically involved themselves in the play activities of the children, as playmates, to initiate and support the sustained engagement of the children in play.

"....so I'll just join in on him playing marbles and, and board games" (Tamara)

"...but I, I must be in that circle, so then he plays with, say, he likes playing with them and they like playing with him, but the moment I move out of the circle then Shaun moves, so if I will say to him Shaun, we need to play with the other children then he will say "NO!" So I said no, but if I leave, he follows" (Allison)

"So I would go to them, and I would ask him to come join me, and then I will initiate play... " (Sam)

Sam described herself to be a constant playmate, who drew on her own playful nature to engage the children with ASD in play.

"So we play all the time. They, I'm the teacher that will be on the floor, roll with them and they will jump on me and stuff like that. So that's how we play or if we're in the playground I'd go and play with them, I go on their level and play with them, like in the sand. But wherever they are, I would play with them." (Sam)

In summary, the participants recognised that opportunities to engage in play were increased when they acknowledged and accommodated the need of the child to direct their own play. Participants were intentional in providing the children with access to their preferred play materials to sustain their engagement in play. They purposefully paired the children with ASD with specific playmates who supported their engagement in play. They also strategically positioned themselves as playmates in the play engagements of the children with ASD, eliciting their own playfulness, to encourage the social play of the children with ASD.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to explore and describe the ways in which caregivers and teachers promoted the play of children with ASD. Participants drew on their understandings of the unique play styles of the children with ASD and adapted their approaches to accommodate the children's need to direct their play. They also altered and adapted the environment to create opportunities and motivate the children to engage in play.

Child directed play is facilitated by creating spaces that foster the children's internal locus of control and their motivation to play

Participants recognised the value of following the lead of the children in play. Child-directed play was facilitated by acknowledging the children's need to be in control of how they would engage in play. Participants were not coercive in their approach to encouraging the play of the children. They allowed the children to choose what they wanted to play with, and where they wanted to play. Participants described how the children engaged longer in play when they were in control of the conditions of their play, choosing how they wanted to play, and what they wanted to play with. Allowing choice in play fosters a sense of control and sustains the intrinsic motivation of children to engage in the play activity19,20.

Play spaces have the potential to either promote or limit play3. Caregivers and teachers skilfully adapted play spaces in ways that allowed the children to select from a wide variety of play opportunities which they recognised as being favoured by the children. Some of the adaptations to play spaces included the provision of preferred play materials in easily accessible places and allowing time to play with these materials. Participants also tried to ensure that the child's preferred play materials were available across contexts, that is in both the home and school context. Similar findings were reported in a study by Román-Oyola et al.14 who described how parents deliberately created play opportunities that the child was interested in. Skaines, Rodger, and Bundy8 describe the provision of secure play spaces, inclusive of a variety of toys, to encourage engagement in play.

Play materials selected to elicit the internal control and motivation of the children

Play materials are important in fostering motivation and supporting the participation of children in play21. The participants in this study were keenly aware of the specific play interests of the children, describing in detail their preferences for specific play materials. They made these play materials available to the children and went to great lengths to ensure that these materials were kept safe when the children were not playing with them. They also recognised the importance of selecting play materials which were durable. Drawing on the knowledge they had gained via their training, participants also created play stations containing different types of sensory play materials, which the children could explore, and which could provide them with multi-sensory stimulation opportunities. Bentenuto et al.22 describes how multi-sensory play materials sustain the play engagement of the child with ASD.

Playmates supporting the development of social play selected to promote the children's framing

Children with ASD are likely to have deficits in social skills23. Participants described how the children tended to choose solitary play. They extended on their promotion of the social play of the children by purposefully pairing the children with ASD with specific playmates, who they had observed to show skill in scaffolding play with the children with ASD. Their intentional choice of the pairing demonstrated the participants' skill in promoting the social play engagement of the children with ASD. These highly supportive measures to support play engagement have been described in prior studies6, 23-25.

Vousden et al.26 found that children with ASD struggle with framing, an important aspect of social play, referring to the ability of the child to interpret and respond to both verbal and non-verbal social cues2. In a study by Román-Oyola et al.14 parents of children with ASD explained that the best way to encourage the social play of their children was to enter into the type of play the children had already established. This was displayed in the present study when participants described when and how they would join the existing play scheme of the children often as a playmate, to initiate and sustain the engagement of the children with ASD in play with them and/or their peers.

Participants were committed to promoting the play engagement of the children. They drew on their understanding of the play of the children and described a variety of ways in which they promoted their play. These ways resonated with the method of scaffolding, described in Vygotsky's17 social-cultural theory of the zone of proximal development. Vygotsky introduced the concept of the zone of proximal development to describe the actual development and the potential development of the children. Scaffolding is a central approach which allows support for the child to develop in line with their developmental trajectory. In action, scaffolding play involves systematically adjusting the amount of assistance offered to a child to match or slightly exceed the level at which the child can independently play with peers17. The process relies on finding the right amount of support without impeding the natural flow of play. The adult might initially provide intensive support by directing the play and modelling behaviour. As the children gain confidence in their play together with peers, the adult begins to withdraw the intensity of their support, offering only intermittent and subtle support. As the children become fully engaged in reciprocal play with peers, the adult withdraws to the periphery of the group, allowing the children to practice and try out new activities on their own.

The participants showed skill in recognizing the zone of proximal development of the children in relation to their play. They used their knowledge about the specific nature of the children's play engagement and linked this with an experiential understanding of the children's playfulness, to promote the play of the children. They drew on various scaffolding approaches, such as, adapting, altering, and accommodating to promote the play engagement of the children. They acknowledged that they needed to be non-coercive and follow the lead of the children. They were fluid with structure and altered the context and routine to create opportunities for play, with consideration of where the children were at in terms of their play engagement, as well as their specific play preferences. They adapted their approaches to encourage interactions with specific playmates, and subtly immersed themselves into the play of the children to encourage more extensive and sustained engagement, when needed. They also withheld their support when the children initiated their own engagement in play.

Strengths and Limitations

This study only reflects the perspectives of five participants drawn from two groups of significant others, that is, caregivers and teachers, from one school context. All participants were female and living in middle to upper income contexts. Subsequent studies should aim to include the perspectives of male participants, female children, and participants from lower income contexts. A case study design, inclusive of observation, will generate data which will enhance the description of how a child's play engagement takes place in context, as well as how it can be promoted in context.

Despite these limitations, the study data presented ca-regiver and educator perspectives of the insightful ways in which they promoted play in children with ASD, in both the home and school context. Gaining this information is an important step in advancing collaborative practice, as sharing experiences will positively inform interventions focused on promoting play in children with ASD.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Caregivers and teachers used a variety of strategies to promote the play engagement of children with ASD. These strategies aligned with scaffolding in that the participants maintained a careful balance between providing and withholding structure and assistance to promote the play of children with ASD, with consideration of the children's zone of proximal development. To advance collaborative, relevant and family centred practice, it is recommended that spaces be created for caregivers, teachers, and occupational therapists to come together to share knowledge, resources, and strategies so that children with ASD can receive the benefit of multiple inputs intending to support their play in and across contexts.

Author contributions

Pamela Gretschel conceptualised and supervised the study and prepared the original draft for this paper. Nyaradzai Munambah guided further conceptualisation and assisted with editing of the manuscript. All other authors collected and analysed the data. All authors edited and finalised the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the caregivers and educators who graciously gave of their time to share their insights and experiences with us. We also wish to acknowledge Ms Kirsty Beamish and Ms Fatima Ebrahim who assisted the authors with the review of the final draft of this article.

Conflicts of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare

REFERENCES

1. Lynch H, Moore A. Play as an occupation in occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy [Internet]. SAGE Publications; 2016 Sep;79(9):519-20. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0308022616664540 [ Links ]

2. Skard G, Bundy AC. Test of Playfulness. Play in Occupational Therapy for Children [Internet]. Elsevier; 2008;71-93. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/b978-032302954-4.10004-2 [ Links ]

3. Rigby P, Gaik S. Stability of Playfulness Across Environmental Settings. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics [Internet]. Informa UK Limited; 2007 Jan;27(1):27-43. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/j006v27n01_03 [ Links ]

4. Truong S, Mahon M. Through the lens of participatory photography: engaging Thai children in research about their community play centre. International Journal of Play [Internet]. Informa UK Limited; 2012 Mar;1(1):75-90. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2012.658647 [ Links ]

5. Hamm EM. Playfulness and the Environmental Support of Play in Children with and without Developmental Disabilities. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health [Internet]. SAGE Publications; 2006 Jun;26(3):88-96. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/153944920602600302 [ Links ]

6. Chiu, H-M, Chen K-L, Lee Y-C, Chen C-T, Lin C-H, Lin Y-C. The Relationship Between Pretend Play and Playfulness in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy [Internet]. AOTA Press; 2017 Jul 1;71 (4_Supplement_1) :7111505096p1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.71s1-po2051 [ Links ]

7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; 2013 May 22; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [ Links ]

8. Skaines N, Rodger S, Bundy A. Playfulness in Children with Autistic Disorder and their Typically Developing Peers. British Journal of Occupational Therapy [Internet]. SAGE Publications; 2006 Nov;69(11):505-12. Available from: http://dx.doi.org//10.1177/030802260606901104 [ Links ]

9. Kent C, Cordier R, Joosten A, Wilkes-Gillan S, Bundy A, Speyer R. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Interventions to Improve Play Skills in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders [Internet]. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2019 Jul 29;7(1):91-118. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00181-y [ Links ]

10. Hobson RP, Lee A, Hobson JA. Qualities of Symbolic Play Among Children with Autism: A Social-Developmental Perspective. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders [Internet]. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2008 May 29;39(1):12-22. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0589-z [ Links ]

11. Pinchover S, Shulman C, Bundy A. A comparison of playfulness of young children with and without autism spectrum disorder in interactions with their mothers and teachers. Early Child Development and Care [Internet]. Informa UK Limited; 2016 Mar 4;186(12):1893-906. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1136622 [ Links ]

12. Reed CN, Dunbar SB, Bundy AC. The Effects of an Inclusive Preschool Experience on the Playfulness of Children with and without Autism. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics [Internet]. Informa UK Limited; 2000 Jan;19(3-4):73-89. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/j006v19n03_07 [ Links ]

13. Hagedorn, R. (1995). Occupational therapy: Perspectives and processes. London: Churchill Livingstone, pp. 21-50. [ Links ]

14. Román-Oyola R, Figueroa-Feliciano V, Torres-Martínez Y, Torres-Vélez J, Encarnación-Pizarro K, Fragoso-Pagán S, et al. Play, Playfulness, and Self-Efficacy: Parental Experiences with Children on the Autism Spectrum. Occupational Therapy International [Internet]. Hindawi Limited; 2018 Oct 1;2018:1-10. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2018/4636780 [ Links ]

15. Schiavone N, Szczepanik D, Koutras J, Pfeiffer B, Slugg L. Caregiver Strategies to Enhance Participation in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health [Internet]. SAGE Publications; 2018 Jul 11;38(4):235-44. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1539449218786713 [ Links ]

16. Lynch H, Hayes N, Ryan S. Exploring socio-cultural influences on infant play occupations in Irish home environments. Journal of Occupational Science [Internet]. Informa UK Limited; 2015 Nov 30;23(3):352-69. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2015.1080181 [ Links ]

17. Vygotsky LS. Mind in Society. Cole M, Jolm-Steiner V, Scribner S, Souberman E, editors. Harvard University Press; 1980 Oct 15; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4 [ Links ]

18. Polit DF, Beck CT. International Differences in Nursing Research, 2005-2006. Journal of Nursing Scholarship [Internet]. Wiley; 2009 Mar;41(1):44-53. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01250.x [ Links ]

19. Cordier R, Bundy A, Hocking C, Einfeld S. Empathy in the Play of Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. OTJR: Occupation, Participation, Health [Internet]. SAGE Publications; 2010 Jun 23;30(3):122-32. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/15394492-20090518-02 [ Links ]

20. Cordier R, Bundy A, Hocking C, Einfeld S. A model for play-based intervention for children with ADHD. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal [Internet]. Wiley; 2009 Oct;56(5):332-40. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00796.x [ Links ]

21. Ray-Kaeser S, Perino O, Costa M, Schneider E, Kindler V, Bonarini A. 7 Which toys and games are appropriate for our children/? Guidelines for supporting children with disabilities' play [Internet]. De Gruyter Open; 2018 Dec 31;67-84. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110613445-011 [ Links ]

22. Bentenuto A, De Falco S, Venuti P. Mother-Child Play: A Comparison of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Down Syndrome, and Typical Development. Frontiers in Psychology [Internet]. Frontiers Media SA; 2016 Nov 22;7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01829 [ Links ]

23. Henning B, Cordier R, Wilkes-Gillan S, Falkmer T. A pilot play-based intervention to improve the social play interactions of children with autism spectrum disorder and their typically developing playmates. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal [Internet]. Wiley; 2016 Apr 26;63(4):223-32. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12285 [ Links ]

24. Chang Y-C, Shih W, Landa R, Kaiser A, Kasari C. Symbolic Play in School-Aged Minimally Verbal Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders [Internet]. Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2017 Nov 23;48(5):1436-45. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3388-6 [ Links ]

25. Nadel J, Martini M, Field T, Escalona A, Lundy B. Children with autism approach more imitative and playful adults. Early Child Development and Care [Internet]. Informa UK Limited; 2008 Jul;178(5):461-5. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004430600801699 [ Links ]

26. Vousden B, Wilkes-Gillan S, Cordier R, Froude E. The play skills of children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder in peer-to-peer interactions with their classmates: A multiple case study design. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal [Internet]. Wiley; 2018 Oct 9;66(2):183-92. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12530 [ Links ]

Submitted: 28 September 2021

1st Review: 12 October 2021

Resubmitted: 29 March 2022

2nd Review: 22 May 2022

Revised: 10 June 2022

Accepted: 10 June 2022

Corresponding author: Pamela Gretschel pam.gretschel@uct.ac.za

EDITOR: Pragashnie Govender

DATA AVAILABILITY: Upon reasonable request from corresponding author

FUNDING: No funding was obtained for this study.

* Final year occupational therapy students, University of Cape Town, South Africa at the time of research