Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.52 no.3 Pretoria Dez. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2022/vol52n3a4

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Occupational therapists' perspectives on the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on their clients in Gauteng, South Africa - a qualitative retrospective study

Nthabiseng PhalatseI; Daleen CasteleijnII; Eileen du PlooyIII; Henry MsimangoIV; Veronica RamodikeV

ISchool of Healthcare Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9749-0226

IISchool of Healthcare Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0611-8662

IIISchool of Healthcare Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/000-0002-4032-2384

IVSchool of Healthcare Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9684-9644

VSchool of Healthcare Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2678-9463

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: In March 2020, the South African government responded to the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic by issuing a national lockdown, calling a halt to all non-essential services and movements, including most occupational therapy services. Occupational therapy clients had no access to treatment during this time and may have experienced occupational injustices.

AIM: We explore occupational therapists' perceptions of the influence of COVID-19 lockdowns on rehabilitation clients in Gauteng, South Africa.

METHODOLOGY: We analysed secondary data collected in July 2020. The original qualitative study assessed occupational therapists' perceptions of the influence of COVID-19 on their service delivery. Sixteen occupational therapists participated in asynchronous on-online focus group discussions. The therapists worked in public and private settings in Gauteng. This study focussed on the influence of COVID-19 lockdowns on clients as perceived by occupational therapists. All data relating to the influence of COVID-19 lockdowns on clients were extracted from the original dataset using ATLAS. ti and then thematically analysed using deductive reasoning.

RESULTS: Five themes emerged from the data. Occupational therapists felt that clients had altered clinical presentation due to infection prevention and control measures (Theme 1). Therapists also felt that the quality of services was negatively impacted, which was detrimental for clients (Theme 2); that their clients experienced occupational injustice due to disrupted services (Theme 3) that vulnerable populations experienced the greatest challenges (Theme 4) and that clients' experienced positive impacts or benefits during the COVID-19 lockdown (Theme 5).

CONCLUSIONS: In future pandemics, decision-makers need to carefully consider the impact of disrupted service delivery for occupational therapy clients, especially vulnerable populations. A syndemic approach is recommended for occupational therapy service delivery during a pandemic. Tailor-made recommendations that are needed for vulnerable populations in South Africa are proposed.

Keywords: COVID-19, syndemic approach, occupational injustice, occupational deprivation, occupational imbalance, occupational alienation, vulnerable populations

INTRODUCTION

In March 2020, the South African government implemented a nationwide lockdown to curb the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, also known as coronavirus1. The spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has impacted health systems across the globe. During the early days of the pandemic, the South African government imposed a level five lockdown, halting most economic activities, except for essential services which were permitted to continue working on site1. In South Africa, many clients had even less access to rehabilitation services during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

South African communities are affected by economic inequalities, high unemployment rate, existing non-communicable diseases, people living with disabilities and almost 30% of the population depending on social grants from the government2. Almost 70% of South Africa's population depends on public health care provided by the government3. Some researchers have described the COVID-19 pandemic as a syndemic4-6. A syndemic is when a health condition is aggravated by contextual and social factors such as poverty, discrimination and structural inequalities, which lead to unfavourable outcomes7. In South Africa, the interactions between social structures (such as poverty, population density, poor access to health care and homelessness) and a health condition such as COVID-19 may have led to increased morbidity and mortality8. Lockdowns are likely to have reduced access to health care and rehabilitation services, placing a greater responsibility on clients to manage their own disabilities or conditions. These circumstances which occupational therapy clients encountered support the views of McMahon4, Singer and Rylko-Bauer5 and Bragazzi6 that COVID-19 is a syndemic rather than a pandemic.

The COVID-19 lockdowns affected both clients' access to health care and their human rights, including the right to privacy, safety, food, security, information, freedom of expression, and freedom of movement9. From an occupational therapy perspective, people may experience occupational injustices if they are unable to meet their needs due to social, environmental and political factors beyond their control and are unable to engage successfully in meaningful occupations10. Occupational injustice may manifest as occupational deprivation, imbalance or alienation. Occupational deprivation occurs when people are deprived of their normal occupations10. Occupational imbalance happens when people work too hard or too little10, and occupational alienation includes the subjective experiences of isolation, powerlessness, frustration, loss of control and estrangement from society or the self, due to engagement in an occupation that does not satisfy inner needs11. To date, the level of occupational injustice experienced by clients seeking occupational rehabilitation during COVID-19 lockdowns has not been explored.

People seeking rehabilitation services are generally vulnerable or may have certain disabilities, and feel the effects of emergencies such as climate change, natural disasters, health crises and warfare more acutely due to societal barriers12-14. Vulnerable populations may feel the effects of occupational deprivation, imbalance and alienation more acutely when they cannot do what is necessary and meaningful in their lives due to external restrictions15. These restrictions may include unemployment, poverty or poor access to health care services15. During the early COVID-19 lockdowns, especially levels four and five, infection prevention protocols deprived many clients of the opportunity to participate in groups, access leisure participation and manage their health independently. In South Africa, the elderly and those with comorbidities were most deprived since they had to stay home to protect their health and could not participate in activities outside their homes16. Rehabilitation services were not prioritised during the early lockdowns, and people with disabilities who relied on services such as wheelchair upgrading, seating and maintenance were negatively affected17. The restrictions and protocols to control the COVID-19 pandemic were foreign to most people, who had to change routines and perform tasks differently, which may have caused frustration and loss of control.

In South Africa, people with disabilities in rural areas experience occupational injustices and barriers to accessing health care, particularly rehabilitation services. COVID-19 lockdowns caused further restrictions and more barriers to maintaining levels of functioning in the community. In addition, fear of contracting the virus made it more difficult for people to access healthcare services, and this made them vulnerable to survive the COVID-19 pandemic18.

The effectiveness of infection prevention control (IPC) measures to control the spread of the virus has been recognised by the medical fraternity. Still, little is known about the impact of IPCs on clients who need to manage their non-communicable diseases or continue their lives with a disability. The influence of having to forfeit rehabilitation services in a pandemic has not been investigated. Many clients in South Africa suffered unanticipated negative consequences during the pandemic5, and this study presents a narrow glimpse of the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on public and private healthcare rehabilitation clients from the perspectives of occupational therapy clinicians.

METHODOLOGY

This study forms part of a qualitative study by Uys et al19 who explored the perceptions of occupational therapy clinicians in private and public healthcare settings on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown restrictions on rehabilitation services in Gauteng, South Africa in July 2020. The services of occupational therapists in South Africa were severely impacted as they were categorised as non-essential services and not permitted under level five lockdown restrictions. Only telehealth options could be provided to some service users19. Sixteen participants were purposively selected to include occupational therapy clinicians registered with the HPCSA who work in private or public settings; postgraduate occupational therapy students working as clinicians in different fields of practice or clinical occupational therapy supervisors from University of Pretoria and University of the Witwatersrand with access to email and virtual meeting platforms. Stratified sampling was applied to ensure different settings and practices were sampled. The variations included private and public settings, and various types of practices including paediatrics, mental health, vocational rehabilitation, physical rehabilitation, and school-based occupational therapy clinicians19.

The sixteen participants were randomly divided into two groups of eight and invited to participate in online focus groups. The focus groups were facilitated on Blackboard, the University of Pretoria's learning management system. Participants completed an online consent form and a demographic questionnaire before accessing the asynchronous, online focus groups which were facilitated over a period of one week19. Online focus groups were preferred over face-to-face groups as they were convenient and comfortable for participants19, provided access to diverse participants, and adhered to the South African social distancing regulations during the Covid-19 lock-down restrictions during the data collection period of July 2020. Six main questions were posed to the participants of the focus groups on the influence of Covid-19 on their practice as a clinician and on their ability to provide compassion and care to their service users. Participants were able to respond to the questions electronically in their own time, within the allocated week. Probing questions were used to obtain rich information from participants. The participant responses were collated and the transcription used for analysis. The data were analysed using ATLAS.ti software (version 8)20 and guided by Braun and Clarkes'21 six steps of thematic analysis to generate codes and themes which were identified from the responses to form a coherent presentation of findings and identify the topic of conversation.

The need for the secondary analysis was identified after the original data were analysed. Unexpectedly the original transcriptions contained rich information on the effect of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions on occupational therapy clients which was beyond the scope of the original study. Participants' responses were reanalysed to explore the influence of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on clients in a variety of settings from the perspectives of occupational therapy clinicians. A retrospective, secondary analysis design permits re-analyses of the data outside the limits of the original study objectives22.

The original online focus groups were recorded and available as digital transcriptions. Although the data for this study were extracted a year after the primary data were collected, the data are still applicable to understanding how occupational therapy clients were impacted by early COVID-19 lockdown restrictions.

The data were imported from a Microsoft Word document into ATLAS-ti software (version 8)20 for analysis. Using the software, codes were generated from the data, and sorted into themes and subthemes. Quotations that support the subthemes were selected and reported with a participant code. The participant codes reflect the setting where the occupational therapy clinicians treated their clients. The first two digits represent the participant number, the third digit is the gender of the participant (Male of Female), the fourth and fifth digit represent the field of practice (Sb being school-based; Pa paediatrics; Ph physical and/or neurological conditions; Di being a district hospital; LP being long term psych and AP acute psych; Mx a mix of conditions and VR vocational rehabilitation. The last two digits indicated whether the participant delivered services in private (Pr) or public (Pu) healthcare settings.

Data were analysed using the observe, think, test and revise (OTTR) process described by Basakarada23. This is an iterative process which ends when all data have been organised into themes and subthemes. The researchers also did cross-case comparisons to see if occupational therapy clinicians reported similar or unique experiences in public or private settings.

Ethical considerations

Ethical principles such as confidentiality and non-maleficence were considered, and data were already de-identified in the original dataset. The authors used professional judgement regarding informed consent for the use of the primary dataset for secondary analysis24. Participants had consented to the original study and were aware that their opinions would be used for research purposes. The study was approved by the University of Pretoria's Faculty of Health Sciences, Research Ethics Committee prior to commencing the study (Ethics ID: 436-2020). Permission was obtained from the principal investigator to perform a secondary qualitative analysis to answer a new research question on the existing primary dataset containing data from the two asynchronous, online focus groups19.

RESULTS

Five themes evolved from the data. Themes and subthemes are supported with quotations. The frequency of quotations per subtheme indicates the richness of the data.

Theme 1: Influence of IPC measures on the clinical presentation of service users

Occupational therapy clinicians reported that IPC measures had a large impact on the clinical presentation of clients, especially children, mental health care users (MHCUs), the elderly and on the families of clients. According to occupational therapy clinicians, many children did not understand why the restrictions were implemented, including masks, changed routines and not being allowed to interact with friends. These regulations increased anxiety and confusion in children. In occupational therapy settings, clinicians reported that some children were stimulated by the odour of cleaning products. Due to social distancing protocols, these children could not use sensory integration equipment, including swings and hammocks to modulate their behaviour, which aggravated their insecurity (Table I, page 26).

In hospital settings, social isolation rules prevented mothers from comforting their children in burns wards and those with acute malnutrition. Occupational therapy clinicians reported that MHCUs in long term facilities could not be visited by their families and could not receive extra food and cigarettes. In some cases, forensic wards were closed down and MCHUs could not leave the wards (Table I, page 27). Due to social distancing rules, MHCUs were not allowed to attend occupational therapy pre-vocational programmes. Most MHCUs earn a stipend from the products they make in the pre-vocational programmes and thus their limited incomes were further restricted. The effects of institutionalisation for MHCUs were further compounded by IPC regulations.

Occupational therapy clinicians reported that MHCUs were negatively affected by mask wearing which limited their ability to communicate. Many MHCUs could not rely on facial expressions, a smile for acknowledgement or lipreading to find comfort. Occupational therapy clinicians reported an increase in symptoms of anxiety, irritation and depression among MHCUs. Group therapy was restricted to three to five members due to social distancing. Mask wearing also disrupted the dynamics of group therapy, and curative factors could not be facilitated. Occupational therapy clinicians reported that MHCUs were less interactive in group therapy sessions, where group members started to communicate through the therapist and not with each other. The loss of therapeutic impact resulted in MHCUs being less motivated to attend groups.

Occupational therapy clinicians reported that the elderly was severely affected by IPC regulations, especially those in care homes. In care homes, the elderly was forced to eat in their rooms and no longer in the dining hall. Many residents socialise in the dining hall, which could not happen due to IPC measures. These elderly residents experienced loss of appetite; they stopped taking in fluids and lost weight. Elderly residents could not visit their family members and friends, which increased feelings of loneliness, blunted affect and depression. One occupational therapy clinician reported that the elderly stopped their usual complaints and talked less. Some residents were scared of being infected and imposed self-isolation on themselves, not even attending the groups that were still available. Physically, the elderly became less mobile due to staying in their rooms and exercising less, which increased their risk of falls.

Many occupational therapy clinicians reported that families were negatively impacted by lockdown regulations. In rural areas, support groups for mothers with children with disabilities were discontinued and therapists could not do home visits. Families were not allowed in the wards, which resulted in insufficient family education and families could not support their family members emotionally.

Theme 2: Influence on service quality for service users

This theme reflects that occupational therapy clinicians felt that clients did not have access to good quality rehabilitation services due to IPC measures. The types of services rendered changed due to COVID-19 restrictions and other services could not be rendered at all. Therapeutic relationships between therapists and clients were affected and resources were limited.

Occupational therapy clinicians reported that certain resources were in great demand during the COVID-19 lock-down. Participants in hospital settings reported that wheelchairs were in high demand because many clients were discharged before receiving optimal rehabilitation. While the turnover of patients was high, procurement of resources for rehabilitation was delayed (Table II, page 27). Many clients did not receive therapy or assistive devices during the COVID-19 lockdown. Some occupational therapy clinicians chose to provide services through Telehealth which came with difficulties. Not all clients had access to technology therefore they received limited services. Occupational therapy clinicians tried to compensate for limited hospital inpatient stays by providing more elaborate home programmes. Some occupational therapy clinicians felt that home programmes were not as efficient as face-to-face therapy.

COVID-19 restrictions such as social distancing, reduced contact time and wearing of masks affected general therapeutic programmes. Some occupational therapy clinicians mentioned that group therapy in their work environments was cancelled. Some clients opted not to return for group therapy when restrictions were eased due to fear of contracting the virus.

According to occupational therapy clinicians, therapeutic relationships were negatively impacted by COVID-19 restrictions. This was primarily seen in group therapy, especially with MHCUs and young children (Table II, above). Some occupational therapy clinicians mentioned that therapeutic relationships are essential when working with autistic children. Not being able to interact personally with these children limited their therapeutic relationships.

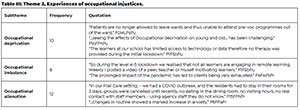

Theme 3: Experiences of occupational injustice

Occupational therapy clinicians felt that clients experienced occupational injustices during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Occupational injustices included occupational deprivation, occupational imbalance, and occupational alienation (Table III, above).

Occupational therapy clinicians reported many examples of occupational deprivation experienced by clients. Therapy in schools was stopped during school closures (Table III). Learners who relied on therapy in schools were severely deprived during closures. At this time, many learners had to engage in remote learning, and lack of cellular data and resources meant no therapy during the first lockdown.

Hospitals could treat a limited number of outpatients, and consequently, some clients experienced long intervals without receiving therapy. High-risk populations such as preterm babies, babies with hypoxic ischaemic encepha-lopathy, adults with cerebrovascular incidents and parents with children with cerebral palsy stopped going to hospitals for their sessions because families and clients feared contracting the virus.

Occupational therapy clinicians reported that MHCUs in long term wards could not attend pre-vocational programmes which provided them with a stipend (Table III, page 28). These MHCUs were deprived of income. The elderly in residential care facilities were also isolated, could not enjoy meals in the dining halls and experienced occupational deprivation and social seclusion.

COVID-19 lockdowns disrupted therapy programmes and daily routines, resulting in occupational imbalance for clients. Even when learners returned to school in a phased approach, many learners still could not receive optimal or balanced therapy because they did not attend school daily. The prolonged occupational imbalance of COVID-19 lock-downs has resulted in pandemic fatigue for many clients (Table III, page 28).

Change or loss of roles, fear and the "new norm" resulted in occupational alienation for many clients. Occupational therapy clinicians reported that some families became overwhelmed and struggled to cope with all the changes and caring for their loved ones. Family education was limited because family members were not allowed into wards. Children were confused by all the new restrictions and struggled to understand why they had to wear masks, sanitise and social distance. Some patients experienced disorientation to time and place due to a lack of routine. Group therapy to facilitate interpersonal learning was done with masks, fewer members in the group and social distancing. These new rules alienated clients, who could not see facial expressions or communicate clearly, choosing to speak through the therapist. Occupational therapy clinicians reported that clients could not achieve therapeutic goals, which led to increased levels of anxiety and fear (Table III, page 28).

Theme 4: Exposing vulnerable populations

Occupational therapy clinicians from public hospitals and residential care facilities were concerned about the impact of the pandemic on vulnerable populations, including unemployed people, the elderly and children (Table IV, above). Pre-COVID-19 socio-economic challenges were amplified during the pandemic.

Occupational therapy clinicians reported that clients were struggling to cope with life as it is. According to occupational therapy clinicians, many clients had no intention of going for COVID-19 testing if they experience symptoms because they would rather not know their status. Occupational therapy clinicians also reported that clients were afraid of travelling to hospital using public transport due to the risk of contracting the virus. Many clients missed their rehabilitation sessions and further struggled to cope with everyday challenges.

Occupational therapy clinicians mentioned that children were a vulnerable population since many school-going children with disabilities depended on school nutrition programmes. Staying at home during COVID-19 lockdowns meant that many children experienced hunger. Where possible therapists contacted families and put them in contact with government feeding schemes. Participants reported that this was hard to observe and to see the effects of poverty on children (Table IV, above).

Occupational therapy clinicians also felt that the elderly in residential care settings were in the vulnerable population group as they were affected by the isolation and not receiving any visitors. With COVID-19 outbreaks in these residences, they had to stay in their rooms, were not allowed to eat in the dining room and all therapy groups were terminated (Table IV, above). This impacted their mobility and general emotional state.

Theme 5: Positive impact on service users

Even though COVID-19 lockdowns caused difficulties, challenges and sudden changes, Occupational therapy clinicians still felt there were positive outcomes for clients (Table V, page 30). Occupational therapy clinicians had to invent alternative ways to continue services. Occupational therapy clinicians could interact regularly with their clients using Telehealth. Intervention plans were sent to families who could not visit due to the COVID-19 restrictions using videos and voice notes. Occupational therapy clinicians reported that some parents were able to call them with feedback on their clients' progress at home. Many clients appreciated the alternative communication and services they received through Telehealth.

Occupational therapy clinicians reported that clients took a greater responsibility for their therapy, were more aware of their ability to help themselves, and did not depend only on therapy received through face to face contact. According to occupational therapy clinicians, they could still help their clients, even indirectly, by supporting their strengths and empowering them to take responsibility for their own treatment.

One occupational therapy clinician reported that clients with orthopaedic conditions were more compliant with home programmes. Parents took greater responsibility and ownership for managing their children with clubfeet than before the COVID-19 lockdowns (Table V, above). Occupational therapy clinicians reported that feedback and communication with their clients improved.

These five themes represent the complex nature of the impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns on occupational therapy clients' experiences, according to occupational therapy clinicians. Although these themes share several commonalities, each theme had unique features. Figure 1, adjacent depicts the occupational therapy client at the nexus of the themes. Our analysis shows that clients may have been impacted by multiple factors and in some cases, one client could have been affected by all five themes. For example, an elderly person in a care facility can be viewed as a vulnerable person who has been severely affected by the IPC measures (no visitation from family) which led to occupational deprivation (no social contact with the outside world and aggravated by not being allowed to go to the dining hall) and in the end receiving poor quality of care (could not benefit from Telehealth as the resources were not available).

DISCUSSION

One of the major theoretical underpinnings of occupational therapy is that of occupational justicelO and this study highlights the occupational deprivation, imbalance and alienation experienced by occupational therapy clients during the initial stages of lockdown in Gauteng. The implementation of IPC measures such as isolation and face masks have mitigated viral transmission. These benefits may have been at the cost of other important therapeutic factors associated with occupational therapy. According to occupational therapy clinicians, lockdown restrictions had many unanticipated negative consequences which impacted families, children, MHCUs and the elderly.

A position paper on mental health care, compiled by a group of experts, including clinicians, mental health experts and MHCUs reported similar consequences of COVID-19 regulations and came up with recommendations for better service delivery in the future25. These experts recommend acknowledging the mental health consequences of IPCs for MHCUs, families, the elderly and children and providing support via therapeutic programmes25. These recommendations are commendable but are suitable for high-income countries. In our study, occupational therapy clinicians reported specific challenges such as children with burns who could not be comforted by their mothers, the elderly who were isolated and long term institutionalised MHCUs not being allowed any visitors. Tailor-made recommendations are needed for these populations during a pandemic, such as empowering service users to take more responsibility on their intervention as well as having access to Telehealth.

In South Africa, occupational therapy clinicians reported that the quality of services dropped due to procurement procedures. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, health executives worldwide started competing for medical resources that were in high demand such as personal protective equipment26. With the high demand for certain resources, procurement of other resources became slow. In our study, occupational therapy clinicians reported a high demand for wheelchairs for clients, which was seldom met. Some clients were discharged without receiving assistive devices and could not be rehabilitated or cared for at home. COVID-19 lockdowns also limited access to occupational therapy interventions and rehabilitation services27.

In our study, occupational therapy clinicians reported that group therapy, which is especially valuable for psychiatric patients28, was extremely difficult to facilitate during the early COVID-19 lockdowns. However, the findings of this study indicate that a large number of service users were deprived of the benefits of group therapy due to restrictions such as wearing masks and social distancing. This affected the therapeutic relationships of therapists with the service users and amongst service users themselves28. In South Africa, many clients stopped participating in therapy, especially if the therapy was difficult to access in the first place. This may have aggravated illnesses, requiring more intervention from occupational therapy clinicians. Many people from low socio-economic backgrounds cannot access services such as Telehealth27. Even though some clients had access to Telehealth, occupational therapy clinicians felt that these services could not replace face to face intervention, which is similar to views expressed in Luck et al.29 In our study, occupational therapy clinicians reported that certain clients benefitted from Telehealth interventions. Parents were able to send video clips of their children at home to demonstrate how they implemented the home programmes given by therapists. The occupational therapy clinicians in turn gave feedback on those videos. It is likely that these clients were private sector clients, who had access to cellular data.

COVID-19 lockdown restrictions constituted a serious barrier for providing and accessing care29, which resulted in occupational injustices. Occupational therapy clinicians reported that elderly care home residents were restricted to their rooms, could not eat in dining halls, had reduced mobility and had limited or no interaction with other patients. These isolation measures disrupted programmes and clients became disorientated and more isolated due to fear of contracting COVID-19, and experienced a decline in mobility and balance. The elderly could not participate in meaningful occupations because they were deprived of participating in daily activities, had no alternative treatment programmes and were alienated due to the 'new normal'.

Learners who relied on occupational therapy intervention were deprived of therapy when schools closed down. A policy brief by The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)30 also indicated that vulnerable children from low-income families and those with disabilities/special educational needs fall behind when isolated and deprived of learning opportunities and extra services such as therapy.

In our study, occupational therapy clinicians reported that certain clients were empowered by the additional challenges of having to deal with COVID-19 lockdowns. Therapists reported that clients started to take greater responsibility for their own therapy, resulting in positive outcomes at home. Luck et al.29 also reported that clients had to prioritise self-management and start to rely more on themselves during the pandemic.

In South Africa the unemployment rate (expanded definition) was at 44.4% in the second quarter of 20214 and more than 18 million people (30% of the population) were receiving social grants from the government3. This paints a bleak picture of the economic status of the country and it should thus not come as a surprise that participants in this study reported on the suffering of vulnerable populations (children, the elderly, mental health care users and those with socio economic challenges) during COVID-19. Even without a pandemic, these populations need support and are more prone to infections and other health conditions.

There is a need for a syndemic approach5,7 to the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa since rehabilitation clients often have to deal with social injustices, as well as their own impairments. Many clients had to deal with the crisis of the pandemic without access to therapy. This study highlighted the crisis that service users experienced and this triggers a need to address the inequalities that a large portion of service users experience in South Africa. It is thus the responsibility of occupational therapists to review their preparedness and response to the rehabilitation needs of clients during a pandemic or similar event. The experiences reported in our study are similar to those experienced by people with disabilities during the influenza pandemic31. Vincent et al.31 recommended that adequate health communication and planning should involve people with disabilities to ensure services continue during the influenza pandemic. This is important for South Africa since there were no clear guidelines to ensure that COVID-19 measures were disability-inclusive during the initial stages of lockdown17.

A set of guidelines on how to manage a pandemic with a syndemic approach in occupational therapy could include: monitoring the health and coping needs of service users; assessing the social determinants of health on the everyday life of service users; food security programmes (including small-scale food production at home such as food gardens); alternatives to continue outpatient services; advocate special permission for community health workers to continue with home visits and extend rehabilitation services to the homes of clients, issuing of wheelchairs and assistive devices in times of crisis; long-term institutions with adapted visitation rules and more support for homeless persons and the elderly.

Limitations of the study

One of the limitations of this study is that we report on the perceptions of occupational therapy clinicians and not their clients. The researchers identified the need for a secondary analysis since occupational therapy clinicians expressed valuable insights into the effects of the COVID-19 lockdowns on their clients. The source of data is thus not a comprehensive account of the service users' point of view. A follow-up study with the voices and lived experience of the clients is needed. These findings cannot be generalised to other settings. The study was done during the first wave of COVID-19 in South Africa. Experiences of the impact of consequent waves after the first wave (from August 2020) are thus not captured in this study. A longitudinal perspective with more focus on changes over time is necessary.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the lives of people in many different ways: how people live, learn, work, play and socialise. Occupational therapists in this study shared their perspectives of how their clients were affected during the initial stages of the pandemic. The five themes indicate that different areas of occupations were affected for clients. Vulnerable populations were mainly affected and needed more support which could not be easily provided due to COVID-19 restrictions. Occupational therapy clinicians highlighted challenges as well as positive points and strategies such as the use of Telehealth, which could help to empower clients in the future.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Cheryl Tosh for editing

Conflict of interest (COI) declaration

The authors declare that there are no opposing interests that may affect this study.

Author contributions

Nthabiseng Phalatsewas the lead author who planned and organised the study. The sections of the article were divided among authors, Eileen du Plooy, Henry Msimango and Veronica Ramodike each contributed to the writing of the article. Daleen Casteleijn did the final editing and references.

REFERENCES

1. Tegally H, Wilkinson E, Giovanetti M, Iranzadeh A, Fonseca V, Giandhari J, et al. Emergence and rapid spread of a new severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) lineage with multiple spike mutations in South Africa. medRxiv. 2020;2. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.21.20248640 [ Links ]

2. South African Social Security Agency. 2019/2020 Annual Report. South Africa, Social Development. 2021 [Accessed 2021 November 30]. https://www.sassa.gov.za/annual%20reports/Documents/SASSA%20Annual%20Report%202020.PDF [ Links ]

3. House I, Street K. Mid-year population estimates [Accessed 2021 November 30]. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022018.pdf [ Links ]

4. McMahon NE. Understanding COVID-19 through the lens of 'syndemic vulnerability': possibilities and challenges. International Journal of Healing Promotion and Education. 2021;59(2):67-69. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2021.1893934 [ Links ]

5. Singer M, Rylko-Bauer B. The Syndemics and Structural Violence of the COVID Pandemic: Anthropological Insights on a Crisis. Open Anthropological Research. 2021;1(1):7-32. https://doi.org/10.1515/opan-2020-0100 [ Links ]

6. Bragazzi NL. The COVID-19 pandemic seen from a syndemic perspective: The LGBTQIA2SP+ community. Infectious Disease Report. 2021;13(4):865. https://doi.org/10.3390/idr13040078 [ Links ]

7. Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. The Lancet. 2017 March 4;389(10072):941-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30003-x [ Links ]

8. Ahmed F, Ahmed N, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. The Lancet Public Health. 2020 May 1;5(5):e240. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30085-2 [ Links ]

9. Adeniyi OO. The Human Rights Impact of COVID-19 on African Women: Focus on Nigeria and South Africa. African Journal of Gender, Society and Development (formerly Journal of Gender, Information and Development in Africa). 2021;10(3):13-31. doi: https://doi.org/10.31920/2634-3622/2021/v10n3a1 [ Links ]

10. Townsend E, Wilcock AA. Occupational justice and client-centred practice: A dialogue in progress. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;71(2):75-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740407100203 [ Links ]

11. Wilcock AA. An occupational perspective of health. Slack Incorporated; 2006. [ Links ]

12. Schiariti V. The human rights of children with disabilities during health emergencies: the challenge of COVID-19. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2020;62(6):661. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14526 [ Links ]

13. Banks LM, Davey C, Shakespeare T, Kuper H. Disability-inclusive responses to COVID-19: Lessons learnt from research on social protection in low- and middle-income countries. World development. 2021;137:105178. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105178 [ Links ]

14. Pineda VS, Corburn J. Disability, Urban Health Equity, and the Coronavirus Pandemic: Promoting Cities for All. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97(3):336-41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00437-7 [ Links ]

15. Stadnyk R, Townsend E, Wilcock A, Christiansen C TE. Introduction to occupation: the art and science of living. In: When people cannot participate: occupational deprivation. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle Creek, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2010. p. 303-328 [ Links ]

16. D'cruz M, Banerjee D. 'An invisible human rights crisis': The smarginalisation of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic - An advocacy review. Psychiatry Research. 2020;292:113369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113369 [ Links ]

17. Lieketseng N, McKinney MEL, Victor M, Leslie S. COVID-19 pandemic and disability: essential considerations. Social and Health Sciences. 2020;18(2):136-48. [ Links ]

18. Sherry K. Disability and rehabilitation: Essential considerations for equitable, accessible and poverty-reducing health care in South Africa. South African Health Review. 2014;2014(1):89-99. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC189294 [ Links ]

19. Uys K, Casteleijn D, Van Niekerk K, D'Oliviera J, Balbadhur R MH. The impact of COVID-19 on Occupational Therapy services in Gauteng Province, South Africa: a qualitative study. South African Health Review. 2021:154. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-healthr-v2021-n1-a17 [ Links ]

20. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH [ATLAS. ti 8 Windows]. (2017). [Accessed 2020 July 27]. Retrieved from https://atlasti.com [ Links ]

21. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

22. Stuckey H, Peyrot M. Living with diabetes: literature review and secondary analysis of qualitative data. Diabetic Medicine. 2020;37(3):493-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14255 [ Links ]

23. Baskarada S. Qualitative Case Study Guidelines. The Qualitative Report. 2014;19:1-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2014.100 [ Links ]

24. Long-Sutehall T, Sque M, Addington-Hall J. Secondary analysis of qualitative data: A valuable method for exploring sensitive issues with an elusive population? Journal of Research in Nursing. 2011;16(4):335-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987110381553 [ Links ]

25. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, Nordentoft M, Cross-ley N, Jones N, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pan-demic.The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(9):813-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30307-2 [ Links ]

26. Kavanagh MM, Erondu NA, Tomori O, Dzau VJ, Okiro EA, Maleche A, et al. Access to lifesaving medical resources for African countries: COVID-19 testing and response, ethics, and politics. The Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1735-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31093-x [ Links ]

27. Hoel V, Zweck C von, Ledgerd R. The impact of Covid-19 for occupational therapy: Findings and recommendations of a global survey. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin. 2021;77(2):69-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/14473828.2020.1855044 [ Links ]

28. Radnitz A, Christopher C, Gurayah T. Occupational therapy groups as a vehicle to address interpersonal relationship problems: mental health care users' perceptions. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019;49(2):4-10. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2019/vol49n2a2 [ Links ]

29. Luck KE, Doucet S, Luke A. Occupational disruption during a pandemic: Exploring the experiences of individuals living with chronic disease. Journal of Occupational Science. 2021;25:1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2020.1871401 [ Links ]

30. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The impact of COVID-19 on student equity and inclusion: supporting vulnerable students during school closures and school re-openings. OECD Publication. 2020;1-37. [Accessed 2022 April 30]. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/ view/?ref=434_434914-59wd7ekj29&title=The-impact-of-COVID-19-on-student-equity-and-inclusion [ Links ]

31. Campbell VA, Gilyard JA, Sinclair L, Sternberg T, Kailes JI. Preparing for and responding to pandemic influenza: Implications for people with disabilities. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(S2):S294-300. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.162677 [ Links ]

Submitted: 4 December 2021

1st Review: 19 February 2022

Revised: 22 May 2022

2nd Review: 27 May 2022

Revised: 21 June 2022

3rd Review: 8July2022

Accepted: 14 August 2022

Corresponding author: Nthabiseng Phalatse Nthabiseng.Ramodisa@up.ac.za

EDITOR: Pragashnie Govender

DATA AVAILABILITY: Upon reasonable request from corresponding author

FUNDING: Funding for this project was obtained from University of Leeds: COVID-19 Rapid Response Innovation Fund