Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.52 n.2 Pretoria Aug. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2021/vol52n2a4

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Exploring the clergy's role in supporting family caregivers of relatives living with stroke

Thuli G. MthembuI, *; Kathy KniepmannII

IDepartment of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1140-7725

IIProgram in Occupational Therapy, Washington University in St. Louis Missouri, USA http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0768-4201

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Stroke is an acute neurological event that creates extensive life changes for survivors and their family caregivers. Religion, spirituality, and congregational resources can support caregivers' quality of life, but little is known about the role that the clergy has in support of caregivers.

AIM: This study explored clergy's roles in supporting family caregivers of relatives with stroke.

METHODS: An exploratory-descriptive qualitative study was conducted with nine participants who were in a purposeful sample recruited from the faith organisations. A focus group discussion and interviews were performed for data collection. Data were thematically analysed in a credible manner through prolonged engagement and peer examination to enhance trustworthiness.

RESULTS: Fives themes that contextualised the abilities of the clergies and their role in supporting families were identified: 1) the importance of spirituality; 2) occupational role of clergy and congregational contributions; 3) family dynamics; 4) caregiver's responsibilities and 5) vision of possibilities.

CONCLUSION: This study provided insight into the roles of the clergy of clergies as part of the interprofessional teams that support family caregivers of relatives with stroke. Furthermore, the study highlights that there is a need for clinicians, clergies, and families to collaborate so that they may exchange ideas for community stroke support programmes.

Keywords: Spirituality, religion, interprofessional collaborative practice, family dynamics, community support programmes

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a leading cause of disability which tends to influence "several cognitive and motor deficits and limitation in daily living"11445. With short hospitalisation and improved survival rates, the need for family assistance is extensive2. While the health care system focuses on the diagnosed person, family members receive minimal guidance or support to manage after discharge. Therefore, families of relatives with stroke often experience what has been called the "unexpected career of caregiver and facing multifaceted, complex and stressful life situations that can have important consequences"3:1.

It has been reported that families tend to experience a lack of knowledge and skills to understand how symptoms affect everyday life and how to assist the relative with a stroke4,5,6 The Stress Process Model of Caregiving7 emphasises social support and coping as important mediators of the stresses that disrupt physical and mental health for families. A systematic review by Pindus et al.8 revealed that families felt unprepared to cope with the challenges of caring for relatives with stroke and they felt abandoned by the lack of services. Corallo et al.1 concur that caregivers should be assisted to "find better coping strategies to minimise a possible physical and emotional burden"11448. It is suggested that health services and professionals should acknowledge spouses of people with mild stroke by educating and supporting them about the unknown impairments that the person with a mild stroke may experience9.

Previous studies have shown that some family caregivers experienced a sense of accomplishment, purpose, and fulfilment from caring for their relatives with strokes101112. Despite the positive effects, a number of studies have found that other families seem to experience strain and burden and many report a combination of positive and negative effects13,14,155 Families' psychological functioning and well-being tend to be challenged by unfamiliar and unpredictable responsibilities related to their role of being a caregiver9,16. It has been reported that caregiving demands and activity restriction have been associated with depressive symptomatology17,18. This is evident in the previous studies, which indicated that family caregivers' new responsibilities are associated with role strain, decline in social routines and decreased leisure participation19,20,21. It is clear that caregiving can restrict socialization, work and other activities; identity and expectations may be profoundly disrupted18,22.

Upheaval of daily life can be overwhelming - physically, emotionally, and spiritually23. Spiritual dimensions of caregiving have received limited attention. Participation in a faith community may improve well-being through social support and guidance for coping24. Spiritual and religious coping strategies are associated with better sense of well-being, resilience, and lower levels of depression among caregivers, to decrease the possibility of experiencing physical and emotional burden1,25.

Religion, spirituality, and congregational involvement contribute to health and quality of life1. Support through congregational networks has been inversely related to emotional distress and depression regardless of health status24,26. Religious or spiritual individuals with chronic conditions report a better sense of purpose, optimism, and gratitude27. Social dimensions of religion help caregivers navigate uncertainty to maintain meaningful identities and be resilient1,24,28. Pastors and parishioners report that participation in religious services enhanced mental health and social support29. Religious participation involving social connection contributes to subjective well-being for adults30. This corroborates with studies highlighting that religious coping tends to be an effective strategy to deal with the occupational demands of stressful events of caregiving for a relative with stroke1,18,31. These studies have accentuated that religious participation seemed to be a useful mechanism families could use; however, the role of clergy needs to be explored further, to gain insight into their perspectives about their services to relatives of people with strokes.

Religious involvement can support coping with the challenges of caregiving16. Pearce32 described religious coping as sacred cognitions, rituals, and supportive relationships within congregations; such coping contributes to caregiver well-being. Clergy are seen as trusted, key resources for individuals facing difficulties15,24,33 and are a valuable resource for mental health concerns and spiritual guidance32,34. However, there is paucity of studies that focused on the support that clergy provide to caregivers of relatives with stroke.

Congregations provide a sense of community, and such social support can be a bridge to health professionals17,35,36. Clergy, lay leaders and fellow congregants are uniquely positioned to provide informal mental health services and social service linkage without stigma or financial strain37. The clergy are assets that support families' transitions through discharge from hospitals to home, illness, end of life, bereavement, grief, marriage, and diverse crisis37. Yet, little is known about the role that clergy have in support of caregivers through the journey of caregiving for relatives with stroke. This study aimed to explore the clergy's role in supporting family caregivers of relatives with stroke.

METHODS

Study design

An explorative-descriptive qualitative research design was used to gain an understanding of and insight into the phenomenon of clergy's role in supporting families with a relative living stroke. It was further employed to allow the participants to share, compare and co-construct their meaning of their occupational role. Explorative-descriptive research could be used to refine the health practice problems and religious support services provided to families affected by stroke38.

Participant recruitment and selection

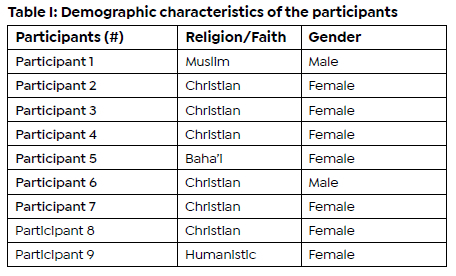

In this study, the population was comprised of clergy from multiple religions or faiths in the metropolitan area of St. Louis, Missouri in the United States. The recruitment of the participants was done through an interfaith organisation that included all religions or faiths in the area. The organisation assisted the authors to have access to clergy from a variety of denominations. Purposive sampling was employed to recruit participants from multiple faiths who met the inclusion criteria for the current study39. Inclusion criteria were at least two years of formal or informal pastoral counselling and English-speaking skill. Potential participants were invited to a focus group. Anyone who was interested but unable to attend the focus group discussion was given the option of an individual interview. Two participants were male and seven were female (Table I page below).

Data collection

A focus group discussion (FDG) and individual interviews were used to gather information from clergy about their experiences and perspectives on family caregivers of relatives with stroke40. Five participants engaged in the FGD, which lasted 90-minutes. The FGDs provided the participants with an opportunity to engage in an interactive conversation about their experiences of working with the family caregivers of relatives with stroke. During the FGD, the participants were consistently reminded that the conversation would be kept confidential, and anonymity was ensured.

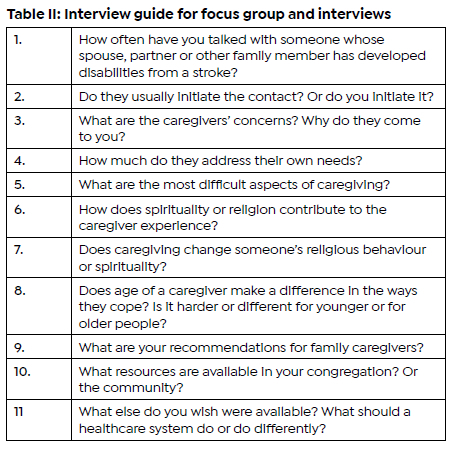

Four semi-structure interviews were conducted with participants whose schedules did not allow them to come together as a group, which took 25 to 45 minutes. An interview guide was used to ask questions on clergies' perspectives and experiences regarding family caregivers of relatives with stroke. This guide was used for the focus group and for semi-structured interviews (Table II page below). Topics included their perspectives on family member spirituality, religious coping, quality of life and their experiences at guiding, supporting, or assisting caregivers. The focus group session and individual interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim then rechecked twice for accuracy.

Data Analysis and trustworthiness

Thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke41 was used to analyse the data from the transcripts. The authors carefully read each transcript at least three times to familiarize themselves with the data as part of prolonged engagement. In addition, codes were generated independently by the study team members who did initial data-driven coding as part of researcher triangulation. This led the study team members to convene a meeting to enhance credibility through peer debriefing and discussion of the codes they generated. Comparisons of that coding revealed minimal discrepancies that were resolved through discussions which resulted in formation of categories by grouping of codes with similar patterns. Themes were formulated by grouping the categories which appeared to relate to each other by the team members based on their vetting of the categories. For trustworthiness, credibility was enhanced through peer evaluation and discussions until consensus was reached about identified themes from the data analysis. Confirmabil-ity was enhanced using audit trail and purposive sampling method to keep track of the study's processes for collation of the themes and writing up the report.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Protection Office (HRPO) at the Washington University St. Louis and ethical clearance number: HRPO#08-0463. Informed consent was obtained from the participants as they signed the consent form before any data collection began. The participants were informed that they may withdraw from the study without repercussions, as they were not coerced to be part of the study. Anonymity was used to protect the privacy and confidentiality of the participants as only numbers were used to identify them.

RESULTS

Five themes related to the perceptions and experiences of the clergy regarding provision of support to family caregivers of relatives with stroke were identified. These themes include 1) the importance of spirituality ("Like a tree in the storm");2) occupational role of clergy and congregational contributions ("Sharing the journey"); 3) family dynamics ("Things changing so quickly";4) caregiver's responsibilities ("Trying to juggle it all"); and5) Vision of possibilities to assist caregivers.

Theme One: Importance of spirituality - "Like a tree in the storm"

Theme one contextualises the importance of spirituality as an intrinsic resource that enabled the tree to be flexible and resilient during the time of the storm. Furthermore, the first theme highlighted that there was a need for more emphasis to focus on the family caregivers' physical, psychological, and spiritual health. Family caregivers seldom mentioned their own needs; participants had to introduce the topic, since caregivers focused on helping their relatives while ignoring their own needs. It was evident from the participants' discourse that spirituality and/or religion was recognized as an anchor for comfort and hope amidst disruption and uncertainty. One participant explained that spirituality tended to be a source of energy:

"... where caregivers draw strength and encouragement." Participant # 3

This was supported by another participant who explained that:

"In order to handle that toll from day-to-day, your inner strength comes from spirituality." Participant # 3

It seems that both faith and spirituality were considered as roots of a flowering tree that needed to be nurtured by the participants. From the analysis, it was clear that the participants in the journey of being a clergy in their communities happened to come across families who appeared to struggle with caring for a relative with stroke. For instance, one of the participants shared an experience about an active member who had abandoned church in despair after grappling with difficult family caregiving demands:

"It's like a tree in a storm that you've seen fall over. It was a really strong, beautiful tree but you look inside and it's hollow." Participant # 2

Other participants agreed, providing these examples of inner strength from strong spiritual roots. It was evident that the participants' explanation about the inner strength seemed to be related to occupational resilience and connection with God:

"You have some people who are really not only rooted in their faith, but they're really rooted in understanding what the meaning of life is. So going to church is not just rote habit. They're really trying to experience the presence of God." P# 6

"For some people, God is a great source of strength through that time and for others." Participant # 8

Participants observed that caregivers tend to get very involved with their immediate tasks of caring for their relatives with stroke. As a result, they end up neglecting themselves, particularly their spiritual well-being, which appeared as an adversity. In a voice of caregiving role, the study participants felt compelled to shift their focus onto the family caregivers' needs. One of them explained:

"The spiritual issue for people is kind of remembering to recognise their own worth as well as the worth of the person that they're taking care of ... [but] our own worth and dignity is important. So that's the kind of spiritual aspect I think that people struggle with." Participant # 9

Another participant related a range of contrasting responses among family members who are helping their relatives:

"Some become closer to God...[others] become distant because they were just worn out and they didn't have the energies to focus on any relationship other than that of caregiving ... I've seen some people angry with God you know for allowing this to happen- why to my loved one? and why to me?" Participant # 7

Theme Two: Clergy roles, congregation responses - "Sharing the journey"

The second theme deals with the role of being a clergy in communities and congregations facing the difficulties of caring for relatives with stroke. It was noted that the participants had a role in maintaining the spiritual well-being of the family caregivers. They felt that part of their role as clergy included providing support to family caregivers and their relatives with stroke. The participants believed that support from clergy and congregations could galvanise spirituality, social support, and coping skills of caregivers.

This theme further highlights that the journey of caring for relatives living with strokes is a daily occupation that can disrupt family function, health, well-being, and quality of life. The participants shared how life trajectories for family members could dramatically change after a stroke. Managing such changes can be rewarding and fulfilling, but it should be also noted that caregivers experienced mixed emotions, such as exhaustion and feeling overwhelmed with confusion and anxiety. Consequently, the participants shared that compassionate presence appeared to be a useful strategy, when they serve caregivers within their congregation. Listening helps families manage guilt and worries; sometimes caregivers just need a chance to share concerns:

"I'm not a professional counsellor, so you know I'm really there in a role that's more supportive. My biggest job is just to listen, to be those ears." Participant # 8

In relation to sharing the journey of caregiving, the clergy wanted to develop partnerships that could build pathways to link caregivers with their congregations and the larger community, thereby reducing isolation and strengthening faith. One participant underlined the importance of encouraging caregivers not to keep a secret about their experiences of caring for relatives with stroke. Several participants indicated that many caregivers remained silent and isolated so they would not seem weak; they felt they should be able to handle everything on their own. However, the participants felt that caregivers should reach out and ask for help from the members of the ministry that have training to serve as congregational friends. One participant in an educative role declared that it is important:

"Not to hide ... out of shame or being afraid to let people know what's going on. Walk with somebody for as long as it takes through whatever it is." Participant # 7

The participants identified a variety of strategies as external resources that may be used to support caregivers struggling with caring for relatives with strokes. Those strategies formed part of compassionate presence, which included offering encouragement, posing questions, and listening deeply. Therefore, the participants incorporated these strategies in their contacts with caregivers.

"Church becomes family... having support from people who know their situation and probably love both of them (the caregivers) and the care receivers, becoming accepted no matter what can be enormously powerful and healing." Participant # 7

"For people that are active in the church, there's a community fellowship that surrounds them and cares and supports them as well. Whenever we're walking through anything in life . it's a little bit harder to walk through. When we've got communities of care and support all around us, it's an easier journey." Participant # 8

Regarding the congregation's responses, activities were identified that may provide respite and support caregivers. Several participants explained that their congregations provide volunteers to stay with the relative, so the caregivers feel comfortable to attend services to get some respite from the occupation of caring for relatives. Congregation members provide support by visiting the households and engaging in activities such as singing or praying together, bringing communion, blessings, or services into homes of families with disabilities. The concept of a 'faith family' was echoed repeatedly as demonstrated by phone calls, visits, meals, and household help. Some groups established networks for providing meals, transportation, and other services so such assistance was a norm.

"Lot of times we'll get respite from people in the community who volunteer their time. A lot of times as an assembly member, we'll look for references, good references for people. Sometimes we can try some of the neighbours." Participant # 5

"The whole community pretty much goes into action as far as helping whether to bring in meals. So, we are supportive of everything. The actual patient and to the family support." Participant # 4

Theme Three: Family dynamics during caregiving - "Things change so quickly"

The third theme captures perceptions of the participants about the dynamics linked with caregiving that could result in an abrupt change in families. In contemplating the abrupt changes, participants reported that caregiving efforts tend to fall primarily on the spouse.

"It dramatically changes the dynamics of a marriage. Who you've been as a couple and what you've been able to do - all those things change so quickly?" Participant # 8

Although participants felt that the entire family's psychological and spiritual health deserve attention, they were unsure about the best way to address these important aspects of the families. They were keen to help caregivers about sharing responsibilities, take breaks, and care for themselves. Regarding family dynamics, participants noted that proximity of relatives and financial resources tended to shape the caregiving experience. The participants reported that some families seemed to share responsibilities with relatives but noted that other caregivers had no additional family willing to help. Conflict about what to do and how to do it, could be painful. Those with limited funds had greater difficulty getting services or equipment.

"Some are concerned that they're not doing enough, some are concerned that they're being overburdened because other family members are doing ... nowhere near their share so they feel they're being left with a burden." Participant # 3

Gender and age both appeared to influence the distribution of caregiving effort. Women were almost always the ones providing care within the family, which worried the participants. When a male was the primary helper, congregations likely responded immediately with assistance. However, female caregivers were expected to manage on their own. The influence of age was debated. Some believed it was harder for young caregivers who likely have jobs, children, and other responsibilities.

"I think being younger brings some of the dynamics that we talked about, you know, certainly that you don't expect at that age." Participant # 8

Others thought older caregivers may have decreased energy and physical limitations, which automatically add strain. Some clergy feared that seniors might have fewer surviving friends or peers and children who are too busy or live far away.

"I've seen situations where there have been older people wanting to give care, but they really couldn't. And they needed their kids to come in, but the kids are not available. And that has created problems." Participant # 5

Receptiveness to 'outside help' varied. Several participants reported that congregants were somewhat comfortable using community day care and home services but to a lesser extent with nursing homes. One of the participants who was an Imam accentuated that family taking care of each other is a major mandate of Muslim faith; it is an extreme dishonour for the entire family if a relative is neglected or moved to an institution.

"It is embarrassing for the family if the person who gets involved in this disability is left in the nursing home or anywhere else. That is the family's problem, and the family takes care of it. It is, ah, considered a dishonour if somebody doesn't take care of the older people. So, they live with the family, they're not alone." Participant # 1

Theme Four: Caregiver challenges - Trying to juggle it all

The fourth theme incorporates participants' discussion of the occupational imbalances that family caregivers experience. Participants noted that caregivers have so many new responsibilities and feel like they are jugglers who are continuously trying to balance precarious competing demands.

Participants were aware that the occupation of caregiving involves new roles, new tasks, and unpredictable demands that can become a major endurance test.

"Having to hold together so many pieces of life, not only the responsibilities of, you know, your house, your job, or the kind of things you do anyway but now the whole caregiving piece ... It can be exhausting and trying to figure out a way to self-care through that and not feel guilty." Participant # 8

Participants shared concern about the inflexibility among caregivers of relatives with stroke. They mentioned that caregivers seemed to be at high risk of developing compassion fatigue because of the constant demands of caring for their relatives. Even though some of the relatives and friends helped, the caregivers strived to handle it all and were reluctant to share responsibilities.

"Even people who have connections ... still seem to feel overwhelmed. They don't want to rely too much on other people. They feel badly about that ... The person who needs care is upse t... feeling like a burden on their spouse. And then this spouse is feeling like they're both burdens on other members of the family or on friends... . There's just a lot of anger ... A lot of frustration." Participant # 9

One of the participants shared that the "American super independence thing" (Participant # 9) tends to be a challenge for majority of the caregivers because they are unwilling to accept any help from other people. Hence, the participant urged that the caregivers should consider the importance of reaching out for assistance early and often. Additionally, the participants shared that the congregants should be encouraged to actively help rather than wait for requests.

"I think it's easier in other cultures, accepting the idea that we're all here to help each other." Participant # 9

Participants also worried that caregivers seemed to neglect themselves as human beings with human needs that should be fulfilled besides attending to caregiving responsibilities. The participants felt that the caregivers' refusal of help can lead to unintentional self-neglect. As a result, the participants felt that caregivers should be encouraged to take time for themselves.

"Relatives strive to do a thorough job out of love and since there's no respite care, they are 'trying to juggle it all'." Participant # 8

"... and that's not selfish. If they break down, then who's going to continue to care? ... Take care of yourself, seek help, and ask of what you need!" Participant # 7

Theme Five: Vision of possibilities to assist caregivers

I n theme five, the vision of possibilities deals with the course of actions that may be used to provide support to family caregivers of relatives with stroke. This theme captures the activities that were suggested by the participants to address some of the challenges of caregiving. The participants were very concerned that family caregivers face many new demands but have few resources available for respite care, assistance, and support. In relation to respite care, the participants echoed each other that caregivers are worn down because of the duties attached to their roles of caring for their relatives. In addressing the need for respite care, the participants felt that caregivers should be open to opportunities by creating time for themselves and allowing other people to support them. "Someone who can come in for an hour or two and just keep an eye on things while they go for a walk." Participant # 9

Regarding peer support, the participants felt that the caregivers could benefit from connections with others within their communities who were facing similar challenges. Lack of family preparation before discharge was a common concern from the discourse with participants. Most of them highlighted that the benefits of participating in peer support could enable caregivers to socialise, exchange information and provide mutual encouragement but they noted that finding such groups was difficult. Additionally, the participants identified a need of asset-based community development related to family caregivers' support because they believed that this could help easily identify what was available in the community.

"A lot of folks feel kind of at sea ... they talk to their doctors, but when they get home, then what do you do? Caregivers did not know where to turn, especially how to deal with confusing personality or behaviour changes after a stroke." Participant # 9

A collaborative partnership was identified as one of the possible actions that may be used to strengthen relationships between healthcare teams from hospitals and community clergy as well as lay leaders. The participants wanted an exchange of information about how they could support families and develop community programs focused on needs of minorities. They suggested a central resource directory to share with their congregations.

DISCUSSION

This study provided an insight into the role of clergy in supporting family caregivers of relatives with stroke. Overall, the themes that emerged from the study highlighted that clergy's role and congregational resources could be viewed as potential mediators or mitigators of strain among family caregivers and their relatives.

On the importance of spirituality "like a tree in the storm" and the contributions of clergy and congregations through "sharing the journey," the findings demonstrated that these clergy believed that spirituality was one of the sources of strength and encouragement that enables caregivers to persevere in their occupation of caring for a relative living with stroke. These findings corroborate Mthembu et al.'s18 claim that religion and spirituality could be reinforced through involvement of clergy in support of family caregivers of relatives with chronic diseases. Additionally, the findings resonate with previous findings that spiritual and religious coping strategies could be used in an effective manner to overcome the caregiver burden31,42. Moreover, the findings of the study revealed that the clergy's support could reinforce resourcs that may be used to help the family caregivers to meet their own needs while caring for relatives with stroke. This study makes valuable contributions for understanding the importance of faith networks that might provide social support and assist with coping strategies.

Two other themes to emerge from the study were family dynamics related to the "Things changing so quickly" as well as caregiver responsibilities linked with "Trying to juggle it all."

These findings relate to occupational imbalances whereby caregivers tend to spend most of their time on caregiver-related duties and neglect other occupations such as sleep, leisure, social participation, and religious observations18,43.

When providing compassionate presence to family caregivers of relatives with stroke, clergy should be alert to occupational imbalance, which can affect the quality of life. Family caregiving can require extensive time and energy for new, unpredictable responsibilities and changes in daily life. These demands reduce time for social connections, changing caregivers' identity and undermining their sense of a meaningful life. Involvement with clergy and one's faith community can buttress caregivers who are dealing with those changes.

Findings from this study further revealed that clergy and congregations are very concerned about helping family caregivers. They believe that religion and spirituality were resources that contribute to coping, social support and families' occupational resilient to successful care for the relative with stroke. Clergy perceive themselves and their congregation members as players who can share the journey and maintain valuable connections for a sense of belongingness. This emphasis on clergy and congregation members as social supports or sanctuaries parallel findings from previous studies24,37. Given the evidence regarding the social support, the findings indicated that sharing was part of interconnectedness and interdependence between the clergy, congregation and family caregivers and the community, which contributed to the psychological and relatedness well-being needs.

The findings in Theme 4 (Caregiver challenges - "Trying to juggle it all") indicated that family caregivers were overworked and unhappy, which is resonant with occupational imbalance and the dark side of occupations relating to positive and negative values and consequences44. Therefore, clergy bemoaned caregiver tendencies to ignore themselves. It was further evident that caregivers were occupationally alienated because the pattern of self-neglect echoes other research that labelled family caregivers as hidden patients45, shadow workforce46, and unsung heroes47. Several participants expressed difficulty convincing family caregivers that they deserve to take time and energy for self-care, relaxation, and fun. This indicates that caregivers should be assisted to make informed decision about respite care services or taking breaks because they tended to be fraught with guilt about doing things for fun on their own or taking care of themselves. Further research should be undertaken to investigate how clergy pass on their capacities related to occupational resilience.

From the findings of the current study, it was noted that the clergy forged partnerships with caregivers through active listening and "sharing the journey." Some congregations utilise outreach networks to maintain connections and provide support for families with stroke or other disabilities. Rather than wait for someone to reach out, members initiate contact that combined respite with social outings. One congregant would stay home with the relative while another congregant was available to accompany the caregiver for a social activity or religious service.

Another theme that emerged from the study is a vision of possibilities that can be used in providing support to family caregivers. As far as the vision of possibilities is concerned, this study found a need for program development to support family caregivers of relatives with strokes. This finding buttresses the growing consensus that early intervention on risk factors for family caregivers should focus on providing relevant information about relatives' conditions, behavioural and emotional changes, burden, and distress, and problem-solving9,31,43. It also resonates with Serfontein et al.'s43 recommendation that the intervention program should provide support for both the relative with stroke and family caregivers' post-discharge. These intervention programs might help caregivers to adapt and be equipped for their new roles with demanding responsibilities.

Additionally, these findings indicate the need for a collaborative-partnership nexus between healthcare professionals, caregivers, relatives with strokes and clergy/ congregational networks. Although recent studies stress the importance of intervention programmes for supporting family caregivers of relatives with stroke1,9,31,43, they tend to neglect the role of clergy in supporting caregivers. Thus, in collaboration with all stakeholders of interprofessional collaborative practice, clergy can establish reciprocal relationships that would enable the development of programmes at micro- and mesosystem levels.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the small convenience sample from a diverse but limited number of faiths/ denominations. Several other clergies expressed interest but were too busy. The study was done in the metropolitan area of a medium size city in the Midwestern United States and did not include rural or small-town clergy who may have different perspectives or norms. Seven of the nine participants were Christian from a variety of different specific denominations. They requested identification with the broader label of Christian rather than specify their specific denomination. The number of female clergies has been increasing but is still the minority, however this study had predominantly female participants. It may be reflecting that female clergy are more concerned about this topic and therefore more likely to join the study. It could be illuminating to recruit more male clergy in future research to identify possible differences. None of the clergy identify themselves as specifically working with families of people with stroke. While the findings of this study cannot be generalised to all clergy or denominations, the information provides a foundation for further exploration in other locations and with a wider range of denominations, needs assessment and development of resources.

Implications

A key policy priority should therefore be to plan for the long-term rehabilitative stroke support and care in Africa using the assets-based strategy to respond to the ubiquitous poor intersectoral collaboration identified in the joint World Stroke Organisation (WSO)48. The long-term rehabilitation support and care should be geared towards "emotional support, for the patient with stroke and concerned family members"49*47

There is, therefore, potential need for the clergy to form part of the long-term support so that they may indicate how the referral system can be facilitated between health facilities and religious institutions. This is line with the Sustainable Development Goal 17 that encourages collaboration between community leaders, and leaders of the faith-based organisation, public, public-private, and civil society partnerships. The partnership will assist in building on the experience of the stakeholders so that they may disseminate the knowledge about stroke and rehabilitation.

A recent review on stroke profile, progress, prospects, and priorities in Africa indicates that there is "a higher burden of stroke on the psychological and emotional domains of quality of life of caregivers"4*638. The evidence from this study suggests that occupational therapists should focus on the positive and negative values and consequences that illuminate the dark sides of the occupation of caregiving for relatives with stroke44. This suggestion may support and enable occupational therapists to ameliorate the occupational injustices (occupational imbalance and occupational alienation) that persisted to influence the psychological, emotional, physical, social, and spiritual domains of quality of life through participation in valued occupations, as part of occupation-based approach. This promotes occupational therapists to reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being. Stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality with extensive effects on family caregivers, therefore occupational therapists must address the needs of this population.

Interprofessional teams comprise clergy, health and social service professionals should form part of the pragmatic and context-sensitive approach that address the needs of family caregivers of relatives living with stroke. The results indicated that clergy in this study wish they could do more but are very busy and have limited familiarity with effects of stroke or with relevant community health resources. For occupational therapy practice, occupational therapists can build alliances with clergy, community leaders, and leaders of faith-based organisations to support the family members' and caregivers' transitions from discharge into the community in several ways. One strategy is to inform congregations about ways to support family caregivers. Another is to facilitate conversations with clients about congregational resources. On a larger scale, they could promote development of resources such as support groups; respite services; equipment loan programs within and across congregations.

CONCLUSION

This combination of findings provides some support spiritual, caregiving, and educative roles that clergy engaged in supporting family caregivers of relatives living stroke. The evidence from this study suggests that spirituality is one of the internal resources that strengthened the caregivers to be resilient and flexible during the storm of their occupational engagement. This study will prove useful in expanding our understanding of how clergy and congregations espoused interconnectedness and interdependence through spiritual, emotional, and instrumental support. However, the findings further highlighted the dark sides of the occupation of caregiving, as family caregivers tend to be reluctant to acknowledge their psychological, emotional and relatedness needs. This information can be used to develop targeted interventions aimed at ameliorating the occupational injustices hindering caregivers' engagement in their valued occupations.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Both authors contributed equally to writing the article. KK conducted the research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We like to thank the faith-based organisations and the participants for sharing their experiences of providing support to the family caregivers of relatives with stroke.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST (COI)

The authors declare that they have no conflict, financial, belief, and personal interests that could affect their objectivity.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the author who was the principal investigator [Kathy Kniepmann], upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

1. Corallo F, Bonanno L, Formica C, Corallo F, De Salvo S, Lo Buono V, Di Cara M, Alagna A, Rifici C, Bramanti P, Mariono S. Religious coping in caregiver of patients with Acquired Brain Injuries. Journal of Religion and Health. 2019; 58: 1444-1452. https://doi.org//10.1007/s10943-019-00840-8 [ Links ]

2. Benjamin EEA, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017; 135, e146-e603. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 [ Links ]

3. Roberts E, Struckmeyer KM. The Impact of Respite Programming on Caregiver Resilience in Dementia Care: A Qualitative Examination of Family Caregiver Perspectives. Inquiry: a journal of medical care organization, provision, and financing. 2018; 55: 46958017751507. http://doi.org/10.1177/0046958 017751507 [ Links ]

4. Lee KW, Choi SJ, Kim SB, Lee JH, Lee SJ. A Survey of Caregivers' Knowledge About Caring for Stroke Patients. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2015; 39(5): 800-815. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2015.39.5.800 [ Links ]

5. Lutz BJ, Camicia M. Supporting the needs of stroke caregivers across the care continuum. Journal Clinical Outcomes Management. 2016; 23(12): 557-566. [ Links ]

6. Muhrodji P, Wicaksono HDA, Satiti S et al. Roles and Problems of Stroke Caregivers: A Qualitative Study in Yogyakarta, Indonesia [version 1; peer review: 1 approved with reservations] F1000Re-search 2021, 10:380 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.52135.1 [ Links ]

7. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990; 30(5: 583-94.https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583 [ Links ]

8. Pindus DM, Mullis, R, Lim L, Wellwood I, Rundell AV, Abd Aziz NA, Mant K. Stroke survivors' and informal caregivers' experiences of primary care and community healthcare services-A systematic review and meta-ethnography. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2): e0192533. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192533 [ Links ]

9. Hodson T, Gustafsson L, Cornwell P. The lived experiences of supporting people with mild stroke. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019; https://doi.org./10.1080/11038128.2019.1633401 [ Links ]

10. Cameron JI, Stewart DE, Streiner DL, Coyte PC, Cheung AM. What makes family caregivers happy during the first 2 years post stroke? Stroke. 2014; 45(4): 1084-1089. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004309 [ Links ]

11. Mackenzie A, Greenwood N. Positive experiences of caregiving in stroke: a systematic review. Disability Rehabilitation. 2012; 34(17): 1413-1422. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.650307 [ Links ]

12. Sanchez-Izquierdo M, Prieto-Ursua M, Caperos JM. Positive aspects of family caregiving of dependent elderly. Education Gerontology. 2015; 41(11): 745-756. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2015.1033227 [ Links ]

13. Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA. 2014; 311(10): 1052-1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.304 [ Links ]

14. Paradise M, McCade D, Hickie IB, Diamond K, Lewis SJ, Naismith SL. Caregiver burden in mild cognitive impairment. Aging & Mental Health. 2015;19(1): 72-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.915922 [ Links ]

15. Pindus DM, Mullis R, Lim L, Wellwood I, Rundell AV, Abd Aziz NA, Mant J. Stroke survivors' and informal caregivers' experiences of primary care and community healthcare services-A systematic review and meta-ethnography. PLoS ONE. 2018. 13(2): e0192533. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192533 [ Links ]

16. Asadi P, Feridooni-Moghadam M, Dashtbozorgi B, Masoudi R. Relationship between care burden and religious beliefs among family caregivers of mentally ill patients. Journal of Religion and Health. 2019; 58: 1125-1134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0660-9 [ Links ]

17. Wan-Fei K, Hassan S, Sann LM, Ismail S, Raman RA, Ibrahim F. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in stroke survivors and their family caregivers: A pilot study using an actor/partner interdependence model. Electronic physician. 2017; 9(8): 4924-4933. https://doi.org/10.19082/4924 [ Links ]

18. Mthembu TG, Brown Z, Cupido A, Razack G, Wassung D. Family caregivers' perceptions and experiences regarding caring for older adults with chronic diseases. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 46(91): 83 - 88. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n1a15 [ Links ]

19. Jellema S, Wijnen MAM, Stueltjens EMJ, Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden MWG, Van Der Sande R. Valued activities and informal caregiving in stroke: a scoping review. Disability Rehabilitation. 2018;1-12. https://doi.org./10.1080/09638288.2018.1460625 [ Links ]

20. Kniepmann K. Female family caregivers for survivors of stroke: Occupational loss and quality of life. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 75(5): 208-216. https://doi.org/10.4276%2F030802212X13361458480207 [ Links ]

21. Kniepmann K. Family caregiving for husbands with stroke: An occupational perspective on leisure in the stress process. OTJR: Occupation Participation Health Journal. 2014; 34(3): 131- 140. https://doi.org/10.3928/15394492-20140325-01 [ Links ]

22. Delgado RE, Peacock K, Wang CP, Pugh MJ. Phenotypes of caregiver distress in military and veteran caregivers: Suicidal ideation associations. PloS one. 2021; 16(6): e0253207. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253207 [ Links ]

23. Damianakis T, Wilson K, Marziali E. Family caregiver support groups: spiritual reflections' impact on stress management. Aging & Mental Health. 2018; 22(1): 70-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1231169 [ Links ]

24. Ngenye L. Our family portrait: The church as a model of social support. Qualitative Research in Medicine and Healthcare. 2018; 2(1): 45 -54. https://doi.org.10.4081/qrmh.2081.6996 [ Links ]

25. Simpson GK, Anderson M, Jnoes K, Genders M, Gopinath B. Do spirituality, resilience and hope mediate outcomes among family caregivers after traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury? NeuorRehabilitation. 2020; 46(1): 3-15. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-192945 [ Links ]

26. Chatters LM, Mattis JS, Woodward AT, Taylor RJ, Neighbors HW, Grayman NA. Use of ministers for a serious personal problem among African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal Orthopsychiatry. 2011; 81(1): 118-127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01079.x [ Links ]

27. Koenig HG, Berk LS, Daher NS, Pearce MJ, Bellinger DL, Robins CJ, Nelson B,Shaw SF, Cohen HJ, King MB. Religious involvement is associated with greater purpose, optimism, generosity and gratitude in persons with major depression and chronic medical illness. Journal Psychosomatic Research. 2014; 77(2): 135-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.002 [ Links ]

28. Gibbs LAL, Anderson MI, Simpson GK, Jones KF. Spirituality and resilience among family caregivers of survivors of stroke: A scoping review. NeuroRehabilitation. 2020; 46: 41-52. https://doi.org/10.3233.NRE-192946 [ Links ]

29. Banerjee AT, Boyle MH, Anand SS, Strachan PH, Oremus M. The relationship between religious service attendance and coronary heart disease and related risk factors in Saskatchewan, Canada. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014; 53(1): 141-156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9609-6 [ Links ]

30. Wilmoth JD, Adams-Price CE, Turner JJ, Blaney AD, Downey L. Examining social connections as a link between religious participation and well-being among older adults. Journal of Religion Spirituality & Aging. 2014; 26(2-3): 259-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528030.2013.867423 [ Links ]

31. Corallo F, Bonanno L, Lo Buono V, De Salvo S, Rifici C, Bramanti P, Mariono S. Coping strategies in caregivers of disorders of consciousness patients. Neurological Sciences. 2018; 39: 1375-1381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-018-3431-1 [ Links ]

32. Kes D, Aydin Yildirim T. The relationship of religious coping strategies and family harmony with caregiver burden for family members of patients with stroke. Brain injury. 2020; 34(11): 1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1810317 [ Links ]

33. Gertrude N, Kawuma R, Nalukenge Winifred N, Kamacooko O, Yperzeele L, Cras P, Ddumba E, Newton R, Seeley J. Caring for a stroke patient: The burden and experiences of primary caregivers in Uganda- A qualitative study. Nursing Open. 2019; 1551-1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.356 [ Links ]

34. McCain MRC. A grounded theory exploration of clergy's counseling referral practices in black churches. Public Access Theses and Dissertations from the College of Education and Human Sciences. 259. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cehsdiss/25.2016. [ Links ]

35. Pierce B. Book Review: Neighborhood Church: Transforming Your Congregation into a Powerhouse for Mission, Discernment: Theology and the Practice of Ministry. 2020; 6(1): 22-24. Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/discernment/vol6/iss1/ [ Links ]

36. Potgieter SD. Communities: Development of church-based counselling teams. HTS Theological Studies. 2015; 71(2): 01-08. https://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i2.2050 [ Links ]

37. Sielaff AM, Davis KR, McNeil JD. Literature review off clergy resilience and recommendations for future research. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 2020; 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091647120968136 [ Links ]

38. Grove SK, Gray JR, Burns N. Understanding nursing research: Building an evidence-based practice. Elsevier. 2015 [ Links ]

39. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoag-wood K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Administration and policy in mental health. 2015; 42(5): 533-544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [ Links ]

40. Platts C, Smith A. Outsiders on the inside: focus group research with elite youth footballers. In A New Era in Focus Group Research, edited by R. Barbour and D. Morgan, 17-34. Basingstoke: PalgraveMacmillan. 2017. [ Links ]

41. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research Psychology. 2006; 3(2): 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

42. Pearce MJ, Medoff D, Lawrence RE, Dixon L. Religious Coping Among Adults Caring for Family Members with Serious Mental Illness. Community Mental Health Journal. 2016; 52(2): 194-202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9875-3 [ Links ]

43. Serfontein L, Visser M, van Schalkwyk M, van Rooyen C. The perceived burden of care among caregivers of survivors of cerebrovascular accident following discharge from a private rehabilitation unit. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019; 49(2): 24-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2019/vol49n2a5 [ Links ]

44. Morris K. Chapter 13, Occupational engagement in forensic settings: Exploring the occupation of men living within a forensic health unit. In: Illuminating the dark side of occupation: International perspective from occupational therapy and occupational science. In R Twinley, Editor. London: Routledge; 2021: 122-129. [ Links ]

45. Eifert EK, Adams R, Dudley W, Perko M. Family caregiver identity development: A literature review. American Journal of Health Education. 2015; 46(6): 357-367. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2015.1099482 [ Links ]

46. DeokJu K. Relationships between caregiving stress, depression, and self-esteem in family caregivers of adults with a disability. Occupational Therapy International. 2017; Article ID 1686143, 9 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1686143 [ Links ]

47. Iheanacho T, Nduanya UC, Slinkard S, Ogidi AG, Patel D, Itanyi IU, Naeem F, Spiegelman D, Ezeanolue EE. Utilizing a church-based platform for mental health interventions: exploring the role of the clergy and the treatment preference of women with depression. Global mental health (Cambridge, England). 2021; 8, e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2021.4 [ Links ]

48. Fisher M, Martins S. Update of the World Stroke Organization activities. Stroke. 2021; 52: e356 - e357. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035357 [ Links ]

49. Akinyemi RO, Ovbiagele B, Adeniji OA, Sarfo FS, Abd-Allah F, Adoukonou T, Ogah OS. Naidoo P, Damasceno A, Walker RW, Ogunniyi A, Kalaria RN, Owolabi M. Stroke in Africa: profile, progress, prospects, and priorities. Nature Reviews Neurology 2021; 17: 634-656. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00542-4 [ Links ]

Submitted: 26 July 2021

Reviewed: 20 September 2021

Revised: 25 October 2021

Accepted: 27 October 2021

EDITOR: Blanche Pretorius

DATA AVAILABILITY: On request from corresponding author

FUNDING: None

* Corresponding author: Thuli Mthembu tmthembu@uwc.ac.za