Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.52 no.2 Pretoria ago. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2022/vol52na2

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Occupational therapy clinical report writing in South Africa - factors influencing current practice

Julie JayI, *; Denise FranzsenII, **; Matty van NiekerkIII; Patricia de WittIV

IPrivate Practitioner, London, United Kingdom /orcid.org/0000-0002-8999-4384

IIDept of Occupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8295-6329

IIIDept of Occupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7505-5709

IVDept of Occupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3612-0920

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Report writing is considered an essential competency for all health professionals. Current research indicates that this area of professional practice appears to be routinely neglected or poorly executed. Previous studies have aimed at understanding the reasons for this neglect; however studies specific to occupational therapy practice are lacking.

PURPOSE: This study aimed to explore occupational therapists' perceptions of the factors influencing current practice in report writing within the South African context.

METHOD: This qualitative study included six focus group interviews with occupational therapy participants from a variety of clinical sites, fields of practice and health sectors in South Africa, with the exception of medicolegal practice. The qualitative data were inductively analysed to determine specific themes to understand the research question.

RESULTS: While occupational therapists voiced uncertainty about ethical and legal aspects concerning report writing, certain profession-specific challenges, such as professional identity and the use of professional language, are perceived to cause a disconnect between the occupational therapists' reporting and their clinical practice.

CONCLUSIONS: The findings of the study indicate that participants were unsure of the details regarding the legal and ethical requirements of practice for report writing and voiced both positive and some negative sentiments in terms of reflecting professional identity and profession-specific, occupation-based language, acknowledging the challenge of being in a medical setting. The complexity of writing occupational therapy reports was perceived to be influenced by the audience receiving reports, which varied widely.

Keywords: report writing, professional language, professional identity, occupation-based language, clinical practice, professional practice, ethical and legal concerns.

.

INTRODUCTION

Reporting on patient assessment and intervention is accepted as an essential and legal requirement for health and rehabilitation professionals1,2. Rehabilitation professionals, including occupational therapists, compile written reports firstly to provide an accountable record of both assessments and intervention, and secondly to communicate findings with stakeholders, i.e., family members, other health and educational professionals and health funders. There is anecdotal evidence that occupational therapists neglect reporting, which can have serious implications for patient care, therapists' accountability, as well as professional and institutional reputation, but there is limited research into this area3,4.

International studies have indicated the need to consider occupational therapists' perspectives and anxieties about their reports and have described additional professional dilemmas and concerns which influence report writing. Clinical, legal and ethical issues are impacted in occupational therapy by incomplete and inadequate documentation which fails to demonstrate the effectiveness of the service provided4. Other specific challenges that occupational therapists face in producing effective reports include the terminology and language used to communicate the philosophy and values of the profession. The understanding of occupational therapy reports may therefore be influenced, as the readers may not be familiar with concepts included in the report1,5-8. While other professionals, referral services and funding administrators may find occupational therapy terminology difficult to comprehend, this may be even more difficult for clients. Many South African citizens have difficulty accessing healthcare services, and limited health literacy has a profound effect on their ability to understand communication and reports around the health care process for themselves and their families9,10. Occupational therapy reports therefore need to be formulated to best suit various recipients so the use of terminology and the complexity of the language used must be considered depending on who will read and understand the report. It has been recommended that reports for clients and family members should be accompanied by a discussion explaining the terminology and the implications of the contents of the report.

These challenges for occupational therapists within the South African context, highlighted the need to explore report writing in the profession.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Report writing and documentation (also referred to as record keeping) is described as a chronological written record of all that has happened to the patient or healthcare user during any health care process. This method of communication aims to ensure that assessment outcomes and continuity of care are not only recorded accurately but are also reported efficiently between various professionals11. In addition to being a chronological record of care, documentation is legal proof of assessment and intervention. This legal requirement concerning report writing and the storage and protection of those records for many health professions is prescribed by the health professions regulatory bodies who advise that every patient has the right to have sufficient evidence of their care process documented to ensure the safety of the patient and to protect the clinician5. Occupational therapy reports also advocate for the contribution of the profession to the patient's care. Furthermore, well written client records can be used to support research, so progress in the domains of practice provide the evidence for the efficacy of the profession12. Since record keeping should also justify service provision, it can similarly be seen as a means of marketing the profession1,13 and serves to demonstrate the clinical competence of the health professional12.

Much of the research on documentation and report writing within health care has been in medicine, nursing, dentistry, and mental health. Most of these studies are related to the writing, distribution and storing of patient records and explore the validity of electronic health records, as well as the legal requirements for record keeping1,14. Studies focussing on the writing of profession-specific reports often refer to generic issues that affect report writing across all health professions. These generic issues include having a sound professional knowledge and understanding of ethical and legislative implications which apply to reporting and report writing3,15.

Providing reports which are appropriate for other professionals and recipients of occupational therapy services therefore present a challenge and both novice and experienced clinicians have been found to have difficulties with report writing3.

Literature suggests professional reports require a high level of reading ability, which acts as an exclusionary factor for many in understanding professional reports16. International studies have indicated that the reading level required to understand health professional reports is at a university or higher level, which may mean that many South African healthcare users, including occupational therapy service users, may be unable to understand issues around their health and well-being provided in such written reports1,14.

Report writing by occupational therapists within the South African context has been reported to carry some additional challenges. A South African study cited poor attitude of staff, lack of resources as well as a lack of standardisation for reporting and use of occupational therapy jargon as contributing to poor documentation standards17

The literature around documentation highlights an important conundrum in occupational therapy; in that what occupational therapists do may appear easy, but the professional knowledge and reasoning behind their actions are more complex and not easily understood by others and most occupational therapists battle to put what they do into words18. International studies have highlighted a lack of professional identity in occupational therapy, as also impacting on what and how occupational therapists report on their observations and interventions4,19. This may result in a lack of clarity in terms of assessment and intervention goals which can influence effective collaboration due to a lack of understanding of the profession's role and scope20. This may be especially true in the patriarchal world of healthcare where occupational therapists tend to report the presence of illness and remediating impairment, rather than activity and participation, which is key to occupational therapy21. The complexity of the occupational therapy language for other medical professionals and service users has also been highlighted as one of the most important barriers to occupational therapy reporting in service delivery contexts22. Even though reporting may be challenging, occupational therapy documentation should present occupational therapy as distinct from other services to highlight its unique contribution within a multi-disciplinary team and within service delivery.

The question that arises is whether occupational therapists within the South African context understand the importance of representing their unique identity of their profession through occupational therapy reports that are appropriate and unambiguous for different users. These reports need to meet the requirements for professional records despite the complexity of the occupational therapy language and despite limited guidance from the professional bodies.

The purpose of this study was thus to explore occupational therapists' views on factors influencing profession-specific report writing within the South African context.

RESEARCH METHOD

A descriptive qualitative research method23 was used in order to explore the occupational therapists' lived experiences of writing clinical reports in the context of their daily practice. This study was conducted in two phases, however only the first phase will be reported in this article.

Purposive sampling was used to select participants for this study24 from a population of clinical occupational therapist working in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Occupational therapists who were invited to participate in the study22 had a range of clinical experience, worked in a variety of settings and health sectors, namely public, private and academia, had more than 6 months' experience and were required to write clinical reports as part of their daily practice, or who evaluated clinical reports in an educational setting. Occupational therapists who worked in insurance, medico-legal or forensic practices were excluded from participating as their reports are specifically written for legal, disability insurance claims purposes and are based on assessments alone and seldom include intervention.

Data were collected through focus group interviews25. A focus group topic guide was created to facilitate and focus the discussion within the focus group interviews. The topic guide consisted of open-ended questions which were carefully sequenced starting with general questions and ending with more specific questions, to enable conversation around what the participants believed should be included in an occupational therapy report as well as the factors influencing the writing of these reports. This topic guide was piloted with two subject matter experts prior to the data colection26. The purpose of piloting the topic guide was to check for relevance and understanding, as well as to ensure the objectives of the study would be met27.

Ethical clearance for this study was granted by the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical), Certificate number M.140490. Permission for participants to participate in the study was obtained from the heads of departments and chief executive officer/managing committee of hospitals where participants worked. Potential participants were recruited in their individual capacity and were provided with an approved information sheet. They understood confidentiality could not be assured as they participated in group sessions. All occupational therapists who agreed to participate signed informed consent and permission for the focus group interviews to be audio recorded.

Focus group interviews were organised at a convenient time and venue for participants. At the start of the focus group interview participants were required to complete a short demographic questionnaire. Each focus group interview was facilitated by the researcher and lasted approximately an hour.

To ensure rigor of the findings the following principles of trustworthiness were employed: credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability28. The researcher recorded field notes during the focus group interviews and kept a reflective journal. Entries were made after each focus group interview which assisted with reflections on the discussion and research process and allowed the researcher to be aware of her own biases. The principle of data saturation was also applied during the data collection process, where the researcher and supervisors conducted a preliminary analysis of the data to determine when sufficient evidence had been collected29. The researcher did not limit the number of planned focus groups, but continued the data collection until it was apparent that data redundancy had been reached30

A conventional inductive content analysis, using the six steps proposed by Creswell22 was used to identify codes, was undertaken to identify the perceptions of participants of the factors influencing occupational therapy clinical report writing. A stage-by-stage process was adopted in applying inductive principles using open coding once the researcher had bracketed to avoid any preconceived perceptions impacting the analysis. The coding process identified important statements and encoding these before identifying themes and categories from the data which were peer reviewed by the two supervisors of the project31.

FINDINGS

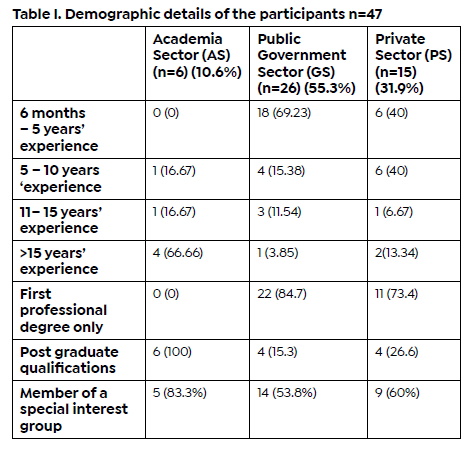

Forty seven occupational therapists participated in six focus group interviews, the point at which data saturation had been reached32. As can be seen from Table I (below) most participants worked in the public government sector and the minority in academia. Most participants had between 6 months to 5 years' experience 51% (n=24) and most had only the first professional degree 65.9% (n=31).

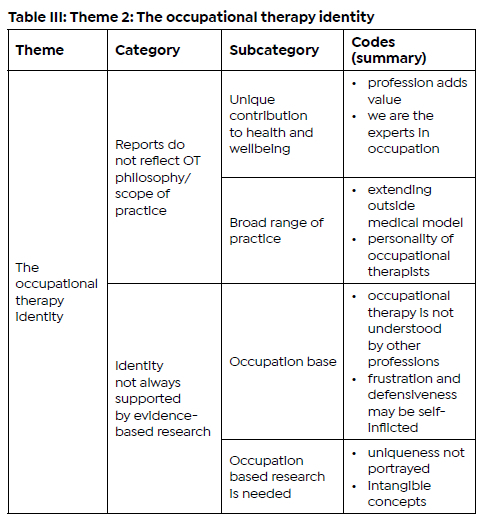

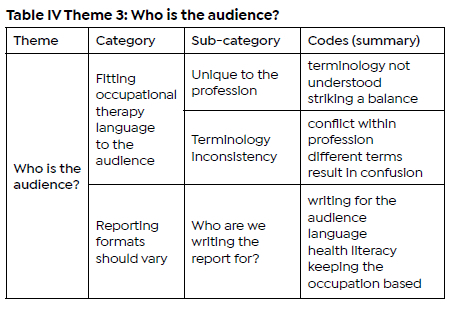

Table II to IV report the themes, categories, sub-categories,and codes that emerged from the qualitative data collected from the six focus group interviews. Although therapists from different sectors had different experiences, the issues discussed were similar and were therefore analysed together rather than separately. Three themes emerged, Theme1: Ethical and legal concerns, Theme 2: The occupational therapy identity and Theme 3: Who is the audience.

Theme 1: Ethical and legal concerns

Two categories emerged within this theme as can be seen from Table II (page above).

Confidentiality

This was a concern for all participants and much of the information shared pertained to managing sensitive information such as the clients' HIV status or information that could have negative consequences for the client. Participants were aware of the possible implications of divulging sensitive information to employers and teachers. Participants acknowledged that their knowledge of the process was unclear.

"... will someone from HR read it and then you are not quite sure, especially with HIV and psychiatry with the stigma and so it's a little bit tricky." GS2. p. 8

The approach by participants was to omit this information, rather than understand the legal and ethical policies that govern this. There was some consensus that practitioners have the right to withhold certain information if they felt it was too much for the patient or family to handle.

"... so, then you are covered because as long as you know the patient could harm himself or would have a problem seeing this report then you don't have to give it to them." PS1. p. 2

This statement was contested by another participant based on personal experience.

"My brother had a head injury and I had to deal with it ... I want to know what's in that report ... Each family is different (but) I still think they need to be able to have access to that. You can't control how everybody is going to react." PS1. p. 3

Further debate was then around to whom the report belonged. Confusion was also apparent around to whom the information belonged.

"Technically it doesn't (belong to the OT), it's yours (the patient's) because you paid for it." PS1. p. 4

Participants commented on the importance of getting consent from the client before releasing any information to others where there may be limited control over who sees the information.

"I think for me also just to keep in mind all the legal aspects and that the report is not only going to be seen by you. There are other people that have access to it." GS2. p. 5

It was acknowledged that health care professionals are bound by ethical principles to manage confidentiality. Participants were unclear about adherence to confidentiality principles once the report is viewed by others or enters the public domain.

"I am concerned where the focus is on people bound by professional council rules and not everyone who requests our reports are held by those legals (rules)." AS. p. 4

Knowing the rules

Participants gave the impression that they were concerned about what they should know and reported being unsure of all the legal requirements for reports.

"But I'm embarrassed to say I don't know that legalese like you can't use pencil you have to use pen, I don't know that." PS1. p. 1

"Like according to HPCSA you have to write in English?" "GS1. p. 1

Understanding the rules which apply in the context to billing for clinical reports was a focus of discussion in some contexts. Report writing is time-consuming which limits other clinical services. The insecurity around billing for reports also affected the occupational therapists' perceptions of themselves as being undervalued compared to their counterparts within the health care system.

"So, we should be charging for all the reports and any extra time we use on the patient but unfortunately, we don't ..." PS1. p. 1

"What should we ethically be able to charge for ... your clinical expertise?" PS1. p. 2

"Also, the fact that we're devalued compared to physio. Our billing is a lot less than physio." PS2. p. 3

There was also apprehension regarding where the responsibility lies for dissemination of information. It was apparent that some participants (particularly those working in a private practice) felt insecure about procedures and policies informing this.

"Where does the responsibility lie? Does it lie with you as a therapist to inform XYZ or does it lie with the patient??" PS1. p. 4

There was some exasperation however, as participants felt that clients generally did not take responsibility for their own health as they do not routinely request or agree to be copied into reports.

"... we do offer them that option if they want to be copied into the report, but they never do." GS2. p. 9

A concern identified by participants was who is dictating report content? It was perceived that when someone other than the client is paying for the report, this may allow them some license around dictating the content of the report.

"You need to identify who you are writing this for first of all. I think that is very important and then who is paying for it? Who's paying for it, where is it going to and for that you got to tailor your report accordingly." PS1. p. 1

This was contradicted by various participants who felt that other professionals did not have the right or knowledge to dictate what should be in an occupational therapy report, as this would be an infringement on the scope of practice of occupational therapy and occupational therapists should have autonomy over what they report.

"So why are we trying to make ours more (like) doctors? Because at the end of the day you're not sending an OT report then, you're sending a report then that you think the doctor wants to hear, but then there's nothing about OT." GS1. p. 8

Theme 2: The occupational therapy identity

Two categories emerged in this theme as can be seen in Table III (above).

Reports do not reflect OT philosophy/scope of practice

Participants felt the profession's unique contribution to health and wellbeing is sometimes lost when reporting on occupational therapy services. They reflected a degree of patriotism and expressed pride in the profession and the unique contribution which should be evident in occupational therapy reports. They felt occupational therapists are most qualified to make recommendations about an individual's or community's occupational performance and participation and this should be clearly reflected in reports.

"I think we are the most qualified to recommend changes (to enhance participation)." GS3. p. 5

" We're proving that what we do is valuable." GC1. p. 6 "Our reports are good and they like our recommendations and they use them. GS2. p. 6

Occupational therapy ascribes to a broad range of practice and not just to the reductionistic medical model definition of health, considering the biopsychosocial and environmental factors associated with health, well-being, and disability. This view enables occupational therapists to work and contribute professionally beyond the traditional medical institutions and reports therefore need to focus on occupational performance and independent functioning in all aspects of life.

"Which we as OTs are quite good at, the chameleon of changing into whatever our setting most wants at the precise moment" AS. p. 2

"But the fact that they're now able to brush their teeth and have a bath by themselves and dress themselves no one sees. OT is so broad that no one ever gets the full picture." PS2. p. 4

It was acknowledged that practitioners themselves tend to bend or flex into what a situation requires, indicating it could be a disadvantage, and why the audience has difficulty identifying with occupational therapy reports. Overall, however, there was a sense of pride that

"We don't fit for a reason" GS1. p.4

Identity not always supported by evidence-based research

There was a perception that philosophy of the profession and the occupation base of occupational therapy led to misunderstanding of reports by other health professionals, practicing in the medical model, and the public.

"... like I think we're ... are actually just purely lost in translation, literally." GS1. p. 1

"But I mean on a professional basis we should not be having to explain ourselves in terms of this: what occupational therapy is." PS2. p. 3

It was acknowledged that the profession has evolved quickly, which has made it difficult for occupational therapists - never mind other professionals and the public - to understand occupational therapy reports.

"Because there are so many things that we do ... But it is also not a very old profession. They are aware of it, but don't know what it is about." GS3. p. 5

It was also acknowledged that the frustration and defensive-ness of occupational therapists may be self-inflicted. There seems to be a need to prove the worth of the profession with evidence, to support occupation-based outcomes reflected in writing reports and justify its existence within the health care team.

"Our profession is growing, and doctors don't exactly know what we do, I feel like if I explain myself in simple terms, it sort of undermines me." GS1. p. 4

"But maybe some do not reflect the occupations in their reports and that is why they feel they have to justify." AS. p. 3

The perceived personality of the occupational therapists as unassertive and their gentler nature contribute to the profession's lack of respect in a highly competitive medical environment. It was felt this contributed to occupational therapists not contesting other professions expanding into the occupational therapy scope of practice and reporting similar outcomes.

"We are very gentle people ... We are not assertive enough. So other professions like physios are using play and doing washing and dressing." GS.3 p. 3

More occupation-based research is needed to provide evidence to support the efficacy of occupational therapy, specifically around having a measurable outcome so that reports can be based on research.

"We're all trying to make our therapy outcome based, so that there's a distinct, measurable outcome at the end of the day." GS1. p. 1

Participants felt that there are many aspects of occupational therapy that are intangible. ". you know obviously there's certain things that can't be measured in what we do." PS2. p. 1.

These aspects are often difficult to justify in occupational therapy reports and outcomes which can be measured scientifically as required.

Theme 3: Who is the audience?

Two categories emerged from Theme 3 as can be seen in Table IV (below).

Fitting occupational therapy language to the audience

Concern was expressed that the audience receiving the occupational therapy reports do not understand the terminology used. This is because the language of occupation-based practice is unique to the profession and others do not understand occupational therapy terminology.

"Some of the other medical professionals do not understand our words" GS1. p. 4.

It is important to strike a balance between use of occupational therapy terminology and more simple terms while keeping the report professional.

"Sometimes for me I think it links with the professional word but writing my report in a way that it's easy for the parents to understand but I can take it to the principal as well and it won't seem too plain or simple" GS2. p. 4

Practitioners also acknowledged conflict of terminology within the profession. Different areas of work or personal preference may influence the occupational therapy framework or model use influencing the terminology in reports.

"Everyone uses the basic occupation framework. Except we use different terms for it and we use some terms that others do not use" AS. p. 5

It was acknowledged therefore that the lack of uniformity in the terminology results in some confusion for occupational therapists themselves and the profession needs to develop some uniformity in terminology to enable better understanding of occupational therapy reports.

"(what) we probably should get right within our profession is terminology and make sure that all OTs are using the same terminology" PS2. p 1.

Reporting formats should vary

Participants perceived that they had to write different types of reports, due to varied audiences and the demands that are made by those paying for the reports and queried who are we writing the report for?

"The referral comes into it and knowing where it is going and whose level of lingo to include ... and things to include play a role" GS2. p. 8

Again, the South African contextual conundrum was discussed, where language, education and health literacy may affect the ability to understand a 'jargon-filled' report. Participants acknowledged the difficulty in striking a balance in wanting to make the reports simple enough for a lay person to understand, but at the same time not making it too simple, so that other professionals still see it as a professional report.

"But like say the family is this uneducated family, you're not going to try and give them your OT jargon-filled report, you're going to give them what they need to know, which is in normal English language" GS1. p. 4

Whilst many participants were eager to adapt the report to the receiver, it was acknowledged that ensuring the report was occupational therapy 'based' so that it reads like an occupational therapy report was important.

"Ja, I think you do your OT report, but you adapt it according to the reader. But it still is OT based" GS.1 p. 6

DISCUSSION

The participants in this study were from three different practice settings and had different levels of experience. This provided a heterogeneous sample which allowed for a wide exploration of issues in report writing to gain greater insights and common concerns related to report writing in different contexts24.

Participants expressed concern about ethical issues in report writing in their current practice. Although some factors had some specific contextually influential elements in the different work settings, similarities were concerns with sensitive information and how to handle these within a written report. An issue around divulging this information was raised and there was some consensus that practitioners have the right to withhold certain information. The withholding of information, however, brought up a moral conflict, since omission can impact the autonomy of the patient and the family and may likely be in contravention of some South African legislation favouring access and the right to information.

It is of concern that the participants seem unaware of existing professional practice guidelines and legislation which provide for report writing. However, some statements in the existing guidelines may be open to interpretation about the best interest of the person (beneficence) such as that in the Occupational Therapy Association of Southern Africa (OTA-SA) Code of Ethics, which states: "The practitioner should not withhold any information or mislead the client in any matter that would limit his or her autonomy. Such information should be provided in a form and language which makes it possible for the information to be useful and understood without causing undue harm or engendering feelings of helplessness"33:2. Thus, it raises the question whether omitting information which may result in the unnecessary loss of a job or stigma and bias is therefore justified?

Consideration around the confidentiality of the report was also discussed. Legislation such as the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA)34 and other government policies have been established to guarantee minimum requirements for the management of personal information to ensure that the rights of persons regarding their personal information are not violated. Practitioners should keep themselves informed about and adhere to this legislation. There is also legislation and policies that entrench an individual's right to give consent before their information is disseminated34. The right to consent to disclosure is echoed in the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) Booklet9, Guidelines on the keeping of patient records5 which define the principles according to which reports can be submitted to other parties and state that all information should be kept confidential unless consent is given by the client. Despite these regulations, the participants questioned the rights of corporate and funding bodies, such as medical funders who are paying for the therapy and referral agencies who request an occupational therapy report. There is no agreement on the ownership of records internationally with Terry35:1 indicating that "while patients have a legal right to their medical records" if they ask for them, the professional is the caretaker of the records and should control access to the records35. Nonetheless, Van Niekerk36 in 2019 attempted to clarify the South African situation using the POPIA34 and the Promotion of Access to Information Act37 to explain under which circumstances the healthcare practitioner controls access to records and when, despite authoring a report/record, a third party controls access and the healthcare practitioner must defer an answer about accessing records to that third party.

Participants working within the private practice context, voiced ethical concerns around the billing for report writing. Therapists perceive the corporate and funding bodies as making report writing more expensive than necessary so that services are paid for. The ethical repercussions of the commodification of healthcare and rehabilitation practices are complex. If the emphasis of health and rehabilitation intervention is on making profit, this may result in the replacement of professional ethics with business ethics38. Thus, a professional report may then be seen as a product, which is owned, rather than a reflection of the patients care pathway.

Even though participants could name policies and legal guidelines, they admitted that they did not know the specifics and were not sure how these impacted on the writing of reports. Therefore, they were unaware of best practice according to these guidelines when writing occupational therapy reports. These findings have been supported by other research on report writing in South Africa4,39,40. A concern addressed in prior studies is the possibility that reports can be used for legal purposes, where a therapist can unwittingly become involved in litigation. It would be in the therapists' best interests to be members of professional organisations and special interest groups, where they can seek guidance, support and be kept up to date on the legislation around report writing and dissemination of information which may change from time to time.

Ethical concerns were voiced, related to the patients' rights and their ability to take responsibility for dealing with their reports. Participants' concern supported the role that professionals play in ensuring maintenance and dissemination of reports while maintaining client-centeredness during intervention, as stipulated by governing bodies such as the HPCSA - "Health care practitioners should honour the right of patients to self-determination, to make their own informed choices, and to live their lives by their own beliefs, values and preferences"50. Participants reported that clients often appeared apathetic in taking responsibility for understanding the implications of the reports and their healthcare needs and therefore felt that providing patients with written reports often did not achieve any outcome. This perceived indifference or apathy to involvement in patients' own care could be related to aspects of poor health literacy where poor understanding alienates health care users from access and effectively participating in the health care process 9, 10.

The view of participants regarding the identity of the profession, as viewed by occupational therapists themselves and others, is felt to have an impact on the quality of the reports. There was much discussion around the fact that many other healthcare professionals do not understand the role of occupational therapy. This was frequently met with some exasperation that at a professional level this should not be occurring. This is not just a problem in South Africa but has emerged through studies done globally. This lack of understanding of the occupational therapy role, as well as the lack of confidence and assertiveness felt by therapists, may influence their practice through reporting on generic health activities as opposed to the specifics of an occupational framework20,41,42. Davis, et al. stated in 2008 that the: "...external forces that shape the documentation of occupational therapy should be examined if the profession is to communicate to stakeholders the evidence upon which treatment is based"43:249.

There was a strong call from the participants to support intervention with evidence, specifically around having measurable outcomes, which may be more recognisable and respected by the health community. This call for evidence-based practice is of a global nature, with occupational therapists around the world identifying that it is necessary to protect the scope of the profession and the livelihood of the professionals43. The participants also identified that part of the challenge is that occupational therapy happens behind closed doors due to the intimate nature of the problems which are dealt with. This may contribute to the misunderstanding of other professionals with regards to what is done or achieved within occupational therapy sessions, as it is not overtly observable. These concerns have been found to be true in other studies8,44. The participants felt that evidence-based practice carries inherent challenges within the profession, as there are many aspects to occupational therapy that are intangible or that cannot be measured using traditional scientific methods45. Describing occupational therapy practice is therefore difficult as it requires therapists to use a range of knowledge from different realms of theory, which can be scientific, practical, social and occasionally spiritual in nature46. But this description is critical in helping therapists to resist the pressure to conform to knowledge and techniques borrowed from other disciplines41. An additional challenge is that the use of occupational therapy terminology which is often seen as being the use of jargon, which many feel is unethical and poor practice1,6,14.

This impacts the occupational therapy identity, where a pervasive feeling of low professional self-esteem is noted. Interestingly, the low professional self-esteem is perceived to be self-perpetuated when practitioners do not use words unique to the profession, or do not describe occupational performance in their reports, resulting in a continuous need to justify the profession. Another counterproductive habit arising from the fear of not being taken seriously and low professional self-esteem, is occupational therapists' need to sound more professional by using elaborate words in an attempt to garner more respect from other health care professionals1,8, which could have the unfortunate by-product of making the reports more difficult to understand. Another concern the participants reported was that many occupational therapy reports do not contain 'occupational' words but rather use the term 'function', as opposed to occupation, when talking about occupational performance, to the detriment of the profession.

Regardless of the frustration, participants also identified a sense of occupational therapy patriotism emerging. They were proud of the profession and the unique service it offered. Participants acknowledged that occupational therapists in many situations, fields of practice and contexts tend to bend or flex into what a situation requires, indicating this could be a disadvantage possibly caused by loss of the profession's unique identity. This "hyper-flexibility" is possibly indicative of the profession still being in an adolescence stage of development as reasoned by Turner in the Elizabeth Casson memorial lecture in 201145. Even though occupational therapy was born under the medical profession, its philosophy and values differ from medicine. Occupational therapists however, often document/define their practice in medical terms in order to communicate with audiences47 and to receive funding from sources that are related to medical care48.

The occupational therapy profession is starting in part to realise that it often does not fit fully under the narrow medical umbrella but a degree of uncertainty was noted by a participant with international work experience as being a worldwide issue, not just specific to South Africa41, 42, 45. These professional identity dilemmas affect report writing in the sense that occupational therapists are uncertain both of what to include in their reports and how their views on occupational performance will be received, particularly by role players steeped in the medical model.

The heterogeneous audience of occupational therapy reports also influences report writing. Occupational therapy reports generally have a wide audience, ranging from other health care professionals, caregivers, corporate/provincial bodies, and funders1,4,39. A heterogeneous audience complicates report writing because, the greater the variety in the audiences, the greater the range of expectations from occupational therapy reports. Furthermore, having a diverse audience makes creating standardised templates and uniform reports difficult or even impossible to comply with. Interestingly, occupational therapists are not unique: other professions, such as psychology, have been reported to struggle with writing reports to heterogeneous audiences and its resultant challenges as well14.

This has occupational therapists confused as to how they should write the report in terms of professional language and what content to include. Should the reports be perceived as unprofessional, practitioners fear that they will not be taken seriously by other professionals, who also read the reports. These challenges make it difficult for occupational therapists to articulate their findings as well as what they do. There is extensive debate in the literature about using occupational therapy jargon or not1,8 since, as expressed by some participants in this study, the audience does not generally understand occupational therapy language in the reports. Several studies have identified that receivers of occupational therapy reports frequently find the occupational therapy jargon difficult to understand and that it should be written in layman's terms1,6. This issue may be exacerbated by compromised health literacy in the South African population, who have had inadequate education and commonly speak English as an additional language.

Participants felt that occupational therapists' poor ability to articulate their actions and philosophy of occupational therapy, subsequently affecting the quality of report writing, was further influenced by the different occupational therapy models of practice, which are taught at different universities and used in different workplaces. The few studies done on reporting in South Africa acknowledge that this lack of standardisation of terminology can lead to an incongruity between professional beliefs and what is reported, which can cause ambiguity of the occupational viewpoint17,39.

The challenge of using universal language for the profession is historical, with many theorists identifying that it is impossible to reproduce all the facets of human occupational life into writing a single professional report49. This, however, is a challenge that South African occupational therapists need to tackle in order to establish what is acceptable terminology to maintain the occupational therapy identity within the South African context50. The importance of clear and precise articulation cannot be overemphasised. Indeed, as stated by Wilding in 2008, occupational therapists need to become more articulate and assertive about what they do or risk other professionals moving in on the scope of occupational therapy practice8.

Participants also noted that different fields of practice in occupational therapy would call for reports to have a different 'look and feel'. Again, participants were divided over this issue. Some participants felt that as occupational therapists, the main focus of the report should be on occupation for all fields and areas of expertise with the reason for dysfunction being the only difference. Other participants, however, were adamant that the different areas of practice called for very specific information, otherwise the essence of the report would be lost. Literature in this regard is limited, but one could link this argument to the use of occupational-based language. The argument of using occupational therapy specific terminology and only covering information around occupation, which is the core value of the profession, should help with defining the scope and the individuality of the profession. If therapists write in terminology or report on areas not specific to occupation, there is a risk of extending beyond the defined scope of practice of the occupational therapy profession, and other professionals adopting areas of our scope8,44.

The issue of clear, uniform articulation of occupational performance then leads to the challenge of whether occupational therapists should write one report or a variety, depending on the audience. It was frequently identified by the participants that those who requested the report would influence how the report should be written and the language that would be used. The South African contextual conundrum of multilingualism, low literacy and inexperienced consumers is again noted, which would result in difficulty understanding a 'jargon-filled' report. The implication described by participants was the sense that they are then required to write the report in simpler language or with reduced content. Such a simple report may, however, not meet the needs of a professional audience and so, two reports would need to be written, which has been recommended in other studies6. The challenges placed on the practicing therapist need to be noted, as writing two reports is likely to increase the time demands, in addition to increasing the risk of omitting important information as noted by some of the participants. Some participants suggested that maintaining an occupationally specific outline for all reports8, 47 may negate the writing of more than one report applicable to all receivers, but the complexity of the language used by the profession cannot be ignored. Not all participants were in agreement with the above suggestion. It was voiced that if a receiver was paying, the report should be tailored specifically to their needs. This highlights the dichotomy of occupational therapy trying to survive and promote itself within the medical model, and the risk of other professions, health funders and others dictating the occupational therapy scope of practice8,45,47.

Limitations of the study

The study only pertains to therapists in Gauteng, affecting nationwide generalisability. Some focus group interviews were carried out at participants' place of work, which may have placed participants in a non-neutral situation. This was tolerated to promote participation and to reduce costs for the study participants. The exclusion of medico-legal reports and those for insurers may also be considered a limitation. This study explored occupational therapy reports from the perspective of the occupational therapist and did not consider the view of the recipients of such reports.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the study indicate that participants were aware of the need to be ethical but were unsure of the details regarding legal and ethical requirements of report writing practice. This raises concerns about undergraduate training as well as continuous professional education in this regard. Occupational therapy identity emerged as a factor that influenced report writing. This extracted positive and some negative sentiments from the participants. Participants were proud of the profession and valued the unique contribution it offers to health and wellness, however they also acknowledged that occupational therapists could be the cause of their own demise, by practicing with insufficient evidence to support effective practice, using variable terminology as well as being too adaptable to the needs to the public and other professions. This adaptability was related to the audience for whom the report is written. The audience played a role in the complexity of writing occupational therapy reports, particularly as the audience receiving reports is widely varied and may not understand occupational therapy language. It was also noted that the audience may dictate what is needed from the reports, which raises some ethical concerns about professional independence. The participants were concerned about writing a variety of reports depending on the audience and speciality and whether occupational therapists should use profession specific language acknowledging the challenge of being occupation- based in a medical setting.

Declaration of conflicting interests

No conflict of interests to declare.

Authors contributions

Jay, J conceptualised and completed the research for a postgraduate degree.

Franzsen, D supervised the research and peer reviewed data, conceptualised and contributed to the article van Niekerk, M supervised the research and peer reviewed data. de Witt, P conceptualised and contributed to the article

REFERENCES

1. Donaldson N, McDermott A, Hollands K, Copley J, Davidson B. Clinical reporting by occupational therapists and speech pathologists: Therapists' intentions and parental satisfaction. Advances in Speech Language Pathology. 2004;6(1):23-38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14417040410001669471. [ Links ]

2. Backman A, Kawe K, Bjorklund A. Relevance and focal view point in occupational therapists' documentation in patient records. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008;15(2):212-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/11038120802087626. [ Links ]

3. van Biljon H. Occupational Therapists in Medico-Legal Work -South African Experiences and Opinions. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013;43(2):27-33. [ Links ]

4. Buchanan H, Jelsma J, Siegfried N. Practice-based evidence: evaluating the quality of occupational therapy patient records as evidence for practice. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016;46(1):65-73. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n1a13 [ Links ]

5. Health Professions Council of South Africa. Guidelines on the Keeping of Patient Records. Guidelines for Good practice in the Health Care Professions. Pretoria 2016. [ Links ]

6. Makepeace E, Zwicker JG. Parent perspectives on occupational therapy assessment report. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;77(11):538-45. doi: https://doi.org/10.4276/030802214X14151078348396. [ Links ]

7. Sames KM. Documentation in Practice. In E.B. Crepeau, E.S. Cohn, & B.A.B. Schell (Eds.). Willard and Spackman's Occu pational Therapy 11th Ed. 2009:403-10. [ Links ]

8. Wilding C, & Whiteford, G. . Language, identity and representation: Occupation and occupational therapy in acute settings. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2008;55(3):180-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00678.x. [ Links ]

9. Kickbusch IS. Health literacy: addressing the health and education divide. Health Promotion International. 2001;16(3):289-97. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/16.3.289. [ Links ]

10. Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(12):2072-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [ Links ]

11. Pessian F, Beckett H. Record keeping by undergraduate dental students: A clinical audit. British Dental Journal. 2004;197(6):703-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811866. [ Links ]

12. Bradshaw KM, Donohue B, Wilks C. A review of quality assurance methods to assist professional record keeping: Implications for providers of interpersonal violence treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2014;19(3):242-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.04.010. [ Links ]

13. Ram MB, Carpenter I, Williams J. Reducing risk and improving quality of patient care in hospital: the contribution of standardized medical records. Clinical Risk. 2009;15(5):183-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1258/cr.2009.090018. [ Links ]

14. Harvey VS. Variables affecting the clarity of psychological reports. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(1):5-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20196. [ Links ]

15. Hazelwood T, BakerA, Murray CM, Stanley M. New graduate occupational therapists' narratives of ethical tensions encountered in practice. Australian occupational therapy journal. 2019;66(3):283-91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12549. [ Links ]

16. Lingard L, Hodges B, Macrae H, Freeman R. Expert and trainee determinations of rhetorical relevance in referral and consultation letters. Medical Education. 2004;38(2):168-76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01745.x. [ Links ]

17. Mlambo T, Amosun SL, Concha ME. Assessing the Quality of Occupational Therapy Records on Stroke Patients at One Academic Hospital in South Africa. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;34(3):10-3. [ Links ]

18. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International journal of qualitative methods. 2006;5(1):80-92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107. [ Links ]

19. Suter E, Arndt J, Arthur N, Parboosingh J, Taylor E, Deutschlander S. Role understanding and effective communication as core competencies for collaborative practice. Journal of interprofessional care. 2009;23(1):41-51 . doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802338579. [ Links ]

20. Fortune T. Occupational Therapists: is our Therapy truly Occupational or are we merely Filling Gaps? The British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2000;63(5):225-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260006300507. [ Links ]

21. Creek J. Occupational Therapy New Perspectives. London: Whurr Publishers Ltd; 1998. [ Links ]

22. Creswell JW. Educational Research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research 4th ed. 4th ed. Boston: Pearson Education; 2012. [ Links ]

23. Kim H, SefcikJS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health. 2017;40(1):23-42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21768. [ Links ]

24. Leard Dissertaion. Purposive sampling: Lund Research Ltd; 2012. Available from: https://dissertation.laerd.com/purposive-sampling.php#types. [ Links ]

25. Ciesielska M, Jemielniak D. Qualitative Methodologies in Organization Studies Volume II: Methods and Possibilities: McMillian; 2018. [ Links ]

26. Davis SL, Morrow AK. Creating usable assessment tools: A step-by-step guide to instrument design 2004 [cited 30]. 2013]. Available from: http://www.docdatabase.net/more-creating-usable-assessment-tools-a-step-by-step-guide-to-1141299.html. [ Links ]

27. Krueger RA, Casey M. Focus Groups: A practical guide for applied health research. London: Sage Publications; 2014. [ Links ]

28. Connelly LM. Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nursing. 2016;25(6):435. [ Links ]

29. Kidd PS, Parshall MB. Getting the focus and the group: enhancing analytical rigor in focus group research. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10(3):293-308. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/104973200129118453. [ Links ]

30. Schell BA, Schell JW. Clinical and Professional Reasoning in Occupational Therapy. Philadelphia USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008. [ Links ]

31. Chandra Y, Shang L. Inductive coding. Qualitative research using R: A systematic approach: Springer; 2019. p. 91-106. [ Links ]

32. Rassafiani M, Zivani J, Rodger S, Dalgleish L. Identification of occupational therapy clinical expertise: Decision making characteristics. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2009;56(3):156-66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00718.x. [ Links ]

33. Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa. Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct. 2005. [ Links ]

34. South African Government. Protection of Personal Information Act. Act no 4 of 2013. Government Gazette 2013. [ Links ]

35. Terry K. Patient records: the struggle for ownership. Medical economics. 2015;92(23):22. [ Links ]

36. Van Niekerk M. Providing claimants with access to information: A comparative analysis of the POPIA, PAIA and HPCSA guidelines. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law. 2019;12(1):32-7. doi: https:/doi.org/10.7196/SAJBL.2019.v12i1.656. [ Links ]

37. South African Government. Promotion ofAccess to Information Act 2 2000 [cited 2021 05.11]. Available from: https://www.gov.za/documents/promotion-access-infor-mation-act#:~:text=The%20Promotion%20of%20Access%20 to,provide%20for%20matters%20connected%20theretith. [ Links ]

38. Rowe K, Moodley K. Patients as consumers of health care in South Africa: the ethical and legal implications. BMC medical ethics. 2013;14(1):1-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-14-15. [ Links ]

39. Rischmuller R, Franzsen D. Assessment of Record Keeping at Schools for Learners with Special Educational Needs in the Western Cape. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012;42(2):13-20. [ Links ]

40. van Biljon H, Casteleijn D, du Toit S. Developing a vocational rehabilitation report writing protocol-a collaborative action research process. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015;45(2):15-21. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/V45N2A4 [ Links ]

41. Ashby SE, Ryan S, Gray M, James C. Factors that influence the professional resilience of occupational therapists in mental health practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2013;60(2):110-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12012. [ Links ]

42. Hayes R, Bull B, Hargreaves K, Shakespeare K. A survey of recruitment and retention issues for occupational therapists working clinically in mental health. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2008;55(1):12-22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00615.x. [ Links ]

43. Davis J, Zayat E, Urton M, Belgum A, Hill M. Communicating evidence in clinical documentation. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2008;55(4):249-55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00710.x. [ Links ]

44. Lundgren Pierre B. Occupational Therapy as Documented in Patients' Records - Part III. Valued but not documented. Underground Practice in the Context of Professional Written Communication. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;8(4):174-83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/110381201317166531. [ Links ]

45. Turner A. The Elizabeth Casson Memorial Lecture 2011: Occupational Therapy-A Profession in Adolescence? British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011;74(7):314-22. doi: https://doi.org/10.4276/030802211X13099513661036. [ Links ]

46. Trevithick P. Revisiting the knowledge base of social work: A framework for practice. British Journal of Social Work. 2008;38(6):1212-37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm026. [ Links ]

47. Lundgren Pierre B, Sonn U. Occupational Therapy as Documented in Patient Records: Part II What is proper documentation? Contradictions and Aspects of Concern from the Perspective of OTs. . Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1999;6(1):3-10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/110381299443799. [ Links ]

48. McIntyre D, DohertyJ, Gilson L. A tale of two visions: the changing fortunes of Social Health Insurance in South Africa. Health Policy and Planning. 2003;18(1):47-58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/18.1.47. [ Links ]

49. Yerxa EJ. Dreams, dilemmas, and decisions for occupational therapy practice in a new millennium: An American perspective. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1994;48(7):586-9. doi: https:/doi.org/10.5014/ajot.48.7.586. [ Links ]

50. Clark GF, Youngstrom MJ. Guidelines for Documentation of Occupational Therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008;62(6). doi: https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2013.67S32. [ Links ]

Submitted: 15 December 2021

Reviewed: 21 March 2022

Revised: 3 May 2022

Accepted: 12 May 2022

DATA AVAILABILITY: On request from correspoding author

FUNDING: Individual Grant from the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand.

* At time of study: Dept of Occupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

** Denise Franzsen: Denise.Franzsen@wits.ac.za