Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.52 no.1 Pretoria Abr. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2022/vol52n1a5

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Challenges related to worker characteristics in the workplace for people with mental illness, as rated by employees with and without mental illness

Danielle MichaelI, *; Jonathan WrightII

IBSc OT (Wits); European MSc Occupational Therapy (Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences). https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5885-2159; Occupational therapist, Danielle Michael Occupational Therapy, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIDip COT (West London Institute of Higher Education), MSc Health Psychology (with distinction) (City University), Senior Examination Qualification (Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences), Postgraduate Certificate in Education (University of Brighton), PhD (University of Brighton). https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2457-1732; Principal Lecturer, University of Brighton, Eastbourne, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Research on the workplace accommodation of people with a mental illness, considering their needs, abilities, and the required work competencies, is limited. Perceptions of which worker characteristics limit the abilities of those with mental illness in the workplace may influence both the understanding of accommodations required in terms of the work as well as the capabilities of these employees. This study, conducted in South Africa, aimed to determine how employees with and without a mental illness, employed in different work sectors, rated the likelihood that worker characteristics present a challenge in the workplace for people with mental illness

METHOD: A quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional design was used. An online questionnaire was completed by 271 participants with a mental illness and 455 without a mental illness. Participants were employed in the public, business, retail, manufacturing, and construction sectors. The impacts of work sector, gender and age were examined

RESULTS: There was a significant difference (p<0.05) for all 38 worker characteristics in the ratings between participants with and without mental illness. Work sector, age and gender contributed to this difference: Ratings only differed significantly in the construction sector on 19 characteristics, for the age group 35-46 years on 16 characteristics, and for males on 5 characteristics

CONCLUSION: People who do not have a mental illness rate the challenge presented by worker characteristics in those with mental illness differently from people who do have a mental illness. This may impact perceptions of work accommodations required

Keywords: work competencies, level of challenge, perceptions of work accommodations, vocational rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT)1, engaging in work is one of the main contributors to the meaning and purpose in the lives of many adults. Thus, occupational therapists focus on people's well-being in their working life, including those who present with a mental illness2. According to the Mental Health Care Act of South Africa3, a mental illness refers to "a positive diagnosis of a mental health related illness in terms of accepted diagnostic criteria made by a mental health care practitioner authorised to make such diagnosis"310. Vocational rehabilitation is provided by occupational therapists for people with mental illnesses prior to their return to work. The therapist may suggest reasonable accommodations in the workplace to ensure an uncomplicated transition back into the workplace, productivity, and success at work, after a period of illness1. In South Africa however, there is a lack of follow-through with return-to-work plans and suggested accommodations, due to limited buy-in by the employee's colleagues and employers4.

This may be due in part to insufficient awareness, knowledge and understanding of the challenges that the employees with mental illness face in the workplace. Thus, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO)5, the difficulties faced by people who suffer from mental illnesses in the workplace may include lack of acknowledgement, the allocation of boring/repetitive tasks, poor interpersonal relationships, uncertainty of their roles, poor communication from supervisors and/or conflict with other colleagues. People with a mental illness also often struggle to engage in work due to decreased productivity as well as poor behavioural and/or emotional control'6.

In studies conducted on the views of employers on employees with a mental illness78 (including one on worker characteristics by Diksa & Rogers9) reported that employers perceived the quantity and quality of work of people with a mental illness as poor with brief tenure, absenteeism, and low flexibility. Additional concerns included the belief that people with mental illnesses needed excessive supervision, took little pride in work, had a low acceptance of their worker roles, difficulty following instructions, poor ability to socialize, and low work endurance. Employers reported negative views and perceptions of worker characteristics of employees with a mental illness, such as poor motivation to work, an increased likelihood of injury as well as becoming angry with little provocation7,8.

There is limited available literature regarding the perceived challenge that these work characteristics of employees with a mental illness pose at work4. No research could be found on how employees with and without a mental illness from different work sectors in South Africa, rate the likelihood of specified characteristics challenging the ability of people with a mental illness in the workplace. This information could be beneficial to those occupational therapists who provide vocational rehabilitation interventions for patients who have a mental illness, when considering an enabling environment as a potential facilitator in the return-to-work process1.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Mental health in the workplace

Mental illness is reported to affect one's cognitive functioning, including, memory, attention, thinking, concentration, problem solving and reasoning10,11. People with a mental illness often take medication, which further impacts their cognitive functioning due to the various side effects such as fatigue, restlessness, lethargy, drowsiness, and memory lapses11,12. These side effects, as well as the behavioural symptoms of their diagnosis, challenge their ability to cope consistently with the demands of work. Coping skills, work modifications and compensatory techniques are therefore needed to help accommodate people with a mental illness to better manage their work tasks and demands13,14.

Providing appropriate support and accommodation for people with a mental illness in the workplace, is often a struggle for companies in South Africa, which impacts on the return to work and reintroduction to work processes and demands for these individuals. Maja et al.4 questioned employers in South Africa about their experiences in accommodating disabled people in the workplace and the barriers which exist. Their findings showed that the employers and colleagues lacked adequate knowledge, understanding and awareness of disability, which their study reported contributed to the ineffective integration of people with disabilities into the work force. They also found that although the South African legislation encourages and enforces a quota of employment of people with disabilities, the employers reported difficulty in meeting these requirements due to the struggle of locating skilled and qualified people with disabilities4.

Sharac et al.15 conducted a systematic review regarding the stigma and discrimination that people with a mental illness face from employers and colleagues in their work setting, as well as the economic impact of employing workers with mental illnesses on companies. They concluded that stigma and discrimination had a negative impact on the employees with a mental illness and their income, as well as the company's views regarding resource allocation and healthcare costs. Results indicated a large negative economic effect for both the employees with a mental illness, as well as the companies. They reported interventions, to reduce and prevent stigma in the workplace, to be economically beneficial15. In a study by Schulze and Angermeyer16, the researchers questioned participants who had schizophrenia, regarding their experiences of stigma in the working environment. The participants reported that they tended to avoid their colleagues and isolate themselves as they perceived they were being treated differently to other workers due to the stigma attached to their illness. They also highlighted that they did not discuss their illness with their colleagues and reported no one in their work environment talked about mental illnesses16. These experiences are common problems encountered by people with mental illnesses in their daily working life, which is consistent with other studies6,15.

Even though obtaining and maintaining a job is hard for people with a mental illness, different studies17,18 have shown that such employees are more determined to engage in work than those without a mental illness. Employees with mental illnesses are aware of their struggles and concerns but are determined to try and use accommodations and changes to help them succeed17. This emphasises the point that being engaged in work and participating in a job is beneficial and important to people with mental illnesses and should not be overlooked in their rehabilitation18.

Views of people with a mental illness in the workplace

In order to correctly place a person with a mental illness in a job, occupational therapists often conduct worksite visits to ensure the work environment is supportive and accommodating. Reasonable accommodations are often discussed with line managers during the worksite visit to facilitate the employee's work performance on return to work19. This is consistent with the work of Waddell and Burton14, who explained that for well-being and optimal performance in a workplace, an employee with a mental illness needs to be in a conducive work setting and be allocated an appropriate type of work consistent with their capabilities. These changes need to be supported by the employers and colleagues for adherence to the work accommodation programme19.

According to the Employment Equity Act 1998 No. 55 of South Africa20:5, "employers should reasonably accommodate the needs of people with disabilities. The aim of the accommodation is to reduce the impact of the impairment of the person's capacity and to fulfil the essential functions of a job". Even though this legislation to accommodate employees in South Africa exists, employers often struggle to do so21. Employers lack understanding of the impact of mental illness on the employee's ability to perform and these views are often not addressed by the employee or the occupational therapist. This in turn may affect the understanding of the difference in the worker characteristics that challenge ability to work between people with and without a mental illness, which should enable appropriate accommodations in the workplace of people with mental illness, from the perspective of all stakeholders21.

The aim of this research was to compare how employees with and without a mental illness rate the worker characteristics that pose a challenge for people with mental illness in the workplace as well as to determine whether the work sector, gender and age of the employees impact the difference in ratings between the two groups.

METHODOLOGY

Study design

A quantitative two-group comparative research design was used. A quantitative research design was chosen as literature suggests that the evidence from quantitative studies is more likely to be implemented than those based on of a qualitative study design22. A descriptive cross-sectional design was used to collect descriptive data using an online questionnaire specifically developed for this study. The questionnaire (completed at one point in time23) determined the views of employees with mental health issues and employees who had worked with individuals with mental health issues, by rating the worker characteristics of those with mental health issues, within the South African employment sectors

Population and sampling:

In 2018, the top five work sectors in South Africa were reported as public (which included health, social services, education, government, and recreation), business, retail, manufacturing and construction24. Thus, the population for this study were employees from these five work sectors. Convenient sampling was used to recruit potential participants which formed five sub-groups based on the top five working sectors described above from two sources. Participants were recruited by the human resources departments of companies, which distributed the on-line questionnaire to their employees who met the inclusion criteria and consented to participate in the study. Participants were also recruited via social media platforms, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Linkedln.

Two groups of participants were included in the study. Employees who formed the 'Participants with mental illness' (PWMI) group were included if they worked in the public, business, retail, manufacturing, or construction sectors in South Africa, and had been formally diagnosed with a mental illness by a health care practitioner authorised to do so. Employees who formed the 'Participants without mental illness' (PWOMI) group worked in the public, business, retail, manufacturing, or construction sectors in South Africa. They had not been diagnosed with mental illness but had worked with a person who had a mental illness in the past year. All participants needed to be able to read and understand English in order to complete the questionnaire.

The online questionnaire was distributed to approximately 12,000 workers in companies but the exact number of people accessing the questionnaire was unknown. It was estimated that a return rate of more than 720 participants would provide a rate of more than 15 participants per item on the questionnaire - a sufficiently large sample according to Tomita25 and Cohen et al.26 to analyse two groups in quantitative research. The sample achieved was 726 participants (271 PWMI and 455 PWOMI).

Measurement

The online questionnaire compiled by the researcher specifically for this study was based on two previously published American questionnaires: Permission was granted to use the Person with Mental Illness Possessing Worker Characteristics questionnaire by Hand and Tryssenaar27, and work characteristics listed in this questionnaire were combined with those identified in the Employer Attitude Questionnaire developed by Diksa and Rogers9. The terminology used to describe worker characteristics in the questionnaire compiled for the current study was found to be consistent with the client factors and performance skills laid out in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework IV19. Prior to circulating the online questionnaire, the content validity from an end-user perspective and comprehensiveness of the questionnaire was determined by pilot-testing. The draft questionnaire was sent to and completed by two PWMI and two PWOMI in each work sector, thus a total of twenty pilot participants across the five work sectors. The participants were asked to indicate if all questions were easily understood, had no ambiguity and were relevant to the study purpose. No revisions to the questionnaire were suggested. Thus, the items on the questionnaire were assumed to be appropriate for the retrieval of information for the study.

The online questionnaire used was made up of two parts:

Part one: Demographic profile of participants

This section had four questions formatted as multiple-choice questions. The first three demographic questions were completed by all participants and included age, gender and working sector of the participants. Age was categorised into 8-year intervals and five workplace sectors of public, business, retail, manufacturing, and construction were listed.

Question four differed for the two sub-groups in the sample: The workers who had been diagnosed as having a mental illness were asked to record their diagnosis, while the workers who had worked with a person who had a mental illness were asked to indicate the time in which this had occurred in intervals of 3-month periods. The time period was capped at 12 months to ensure the participants were able to report on their experience of working with a person with mental illness from a recent account.

Part two: Worker characteristics

This section listed 38 worker characteristics (Table I, above) based on concerns regarding work ability, symptomatology, behaviour, and work performance9.

Each of the participants was asked to rate their perception of each of the 38-worker characteristics in relation to a worker with mental illness in their workplace using a 5-point Likert scale with a midpoint of 3, "some challenge" and end points of 1, "no challenge", and 5, "big challenge".

Data collection

Data were collected online using Survey Monkey, which was sent out to participants across South Africa. Participants received an information sheet with the questionnaire explaining the study and what was expected from them. Restriction on the Survey Monkey program only allowed the questionnaire to be completed once per device to achieve a unique entry from each device. To ensure confidentially, no reminders were sent out and it was left at the discretion of the participants to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire was available for completion for one month.

Data analysis

The returned questions were divided into two groups: PWMI and those PWOMI who had worked with a person who had a mental illness in the past year. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the demographic data collected for each group, including frequencies related to participants' age group, gender, working sector and either diagnosis or time since the PWOMI worked with a person with mental illness in their workplace.

To guide the data analysis, several hypotheses were determined. A primary null hypothesis was generated which stated that: there would be no significant difference in the mean scores, for each worker characteristic, as rated by the PWOMI and the PWMI participants. Three secondary null hypotheses determined that there would be no significant difference in the mean scores of the worker characteristics associated with the demographic profile of the participants: including the gender, age, and work sector.

The data set was first analysed to determine differences in rating between the PWMI and the PWOMI groups. The two groups of the data set were further subdivided according to working sector, gender, and age, to determine if these demographic factors demonstrated any differences between the worker characteristics. Parametric, independent, sample t-tests were used to compare differences in ratings by the PWOMI and the PWMI on the questionnaires, owing to the large sample size and the normal distribution of the data reflected in the similar values for the mean, median and mode. Significance was set at (p-value) <0.05, and only data where rating between the two groups had no significant difference, with a p value > 0.05 for which the null hypotheses were rejected, are presented.

No data were excluded from the data set and data were analysed using the SPSS Software Program, version 24.0.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was applied for and received from the Human Science Research Council (HSRC) of South Africa, ethical clearance number REC 6/22/08/18. Autonomy was implemented by making the participation in the study voluntary. Confidentiality was followed by not requesting any identifying information from the participants on the questionnaires. The use of an online survey meant there was also no way to connect the participants to their answered questionnaire.

RESULTS

Of the 726 participants completed the questionnaire, 271 (37,3%) reported having a mental illness and 455 (62,6%) reported having worked with a person with a mental illness in the past year. In both groups the highest frequency of participants were females and in the 26-35-year age band. (Table II, page 38). In both groups most participants worked in the public sector and the least in the construction sector.

The majority of the PWOMI (38.2%) had worked with a person who has a mental illness in their workplace in the past 9-12 months, while 37.4% of the participants reported to having worked with a person with a mental illness in their workplace in the preceding month. The most common diagnosis reported by the PWMI was Major Depressive Disorder with General Anxiety Disorder (43,4%) being second (32.9%) and Bipolar Mood Disorder being third (12.1%). The remainder diagnoses made up only 11.7% of the sample.

Comparison of challenge worker characteristics present in the workplace by participants with and without mental illness

The primary null hypothesis was rejected since a significant difference was found between the two groups for all 38 characteristics when the mean ratings of the PWMI were compared to those of the PWOMI. The PWOMI consistently rating more challenges posed by worker characteristics for those with mental illness in the workplace, than the PWMI (Table III, page 39).

Characteristic 25, 'Requiring supervision', had the greatest difference in mean rating (1.35), with 'Having problem-solving skills' (1.2) (Characteristic 5) the second, and 'Showing adequate judgement' (1.08) (Characteristic 26) the third greatest mean difference.

The smallest differences were related to characteristics of 'Withdrawing from others' (0.30) (Characteristic 20), 'Handling criticism without emotional upset' (0.42) (Characteristic 6) and 'Tolerating physical demands of the job' (0.48) (Characteristic 36). All these characteristics had higher ratings with 'handling criticism without emotional upset' being rated as "some challenge" by both groups.

Comparison of the challenges worker characteristics present in the workplace in different work sectors

The secondary null hypothesis for work sector was rejected for the business sector which had a significant difference, between the PWMI and the PWOMI (p<0.05) for all 38 questions. Table IV (page 40) represents the results in the other four sectors where no significant difference was found when comparing the mean ratings, for the PWMI and PWOMI. Only 'Withdrawing from others' (Characteristic 20) was assessed as presenting a bigger challenge, with no significant difference in all four work sectors (Table VI, page 41)

In the public sector only two characteristics had no significant difference in ratings between, PWMI and PWOMI. While the manufacturing sector had five. The retail and construction sectors had a similar number of variables that were not significant (16 and 19 ratings respectively). This indicates that the ratings of variables by PWOMI in the construction sector's scores were more consistent to those of PWMI than the other four sectors.

Comparison of challenges worker characteristics present in the workplace according to gender

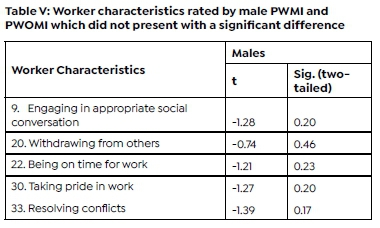

Results show that the secondary null hypothesis for gender could be rejected for the female PWOMI and PWMI with a significant difference between the groups for all 38 characteristics. However, Table V (page 40) shows there was no significant difference in the rating between the male PWOMI and PWMI on five of the work characteristics present in Table V.

Comparison of ratings of challenge related to worker characteristics according to age group

Table VI (page 41) represents the results for the PWMI and PWOMI mean rating, within each age group. In two of the five age groups (age 26-35 and 56-65 years old), all ratings were significantly different (p<0.05) between the two groups for all 38 characteristics. Thus, the secondary null hypothesis for age was rejected for these age groups. The 18-25 age group had five questions with no significant difference for PWMI and PWOMI mean ratings while the 46-55 years age group had six. The 36-45 years age group had no significant difference for 19 characteristics. Thus, it appears that the PWOMI and PWMI who are aged 36-45 years, had more similar ratings for challenges related to worker characteristics than the other four age groups. Only 'Handling criticism without emotional upset' (Characteristic 6) and 'Withdrawing from others' (Characteristic 20) were assessed as presenting a bigger challenge, and 'Grooming' (Characteristic 12) less of a challenge with no significant difference, by both PWMI and PWOMI in these age groups

DISCUSSION

This study determined how employees who do and do not have a mental illness rate the level of challenge presented by worker characteristics in the workplace for employees who have a mental illness. The main findings of this study were that PWOMI and PWMI rated the challenges for most work characteristics differently and that the 'work sector', 'gender' and 'age group' of the participants impact these ratings.

When rating the work characteristics, PWOMI rated 'Handling criticism without emotional upset', 'Controlling emotions' and 'Resolving conflicts' as the greatest challenges that PWMI have in the workplace. PWMI rated 'Handling criticism without emotional upset', 'Controlling emotions' and 'Withdrawing from others' as their greatest challenges. Two characteristics were, however, rated as posing the biggest challenge by both groups, the ratings differed between the groups, showing a difference in the perception of the level of challenge these characteristics present for people with mental illness in the workplace. In the PWMI group of this study, the majority of the participants had a mood-related diagnosis, thus the rating of 'Controlling emotions' could be anticipated to be a higher challenge since there is a link between emotional regulation and mental illness, well-being and job sataifaction28.

PWOMI often have limited knowledge and education regarding mental illness, thus relying on what they observe and on stereotypes for information27. The differences in the ratings may suggest that the PWOMI are interpreting or understanding the challenges faced by their colleagues who have a mental illness, differently from PWMI. This may result in stigma, which is a universal struggle faced by people with a mental illness in the workplace16. Therefore, the people may not be transparent about their mental illness in the workplace. Also, some South Africans still believe that a mental illness is a result of a spirit possession29 and are unlikely to admit to having a mental illness and discussing it with their support system at work. This may explain the different rating that PWOMI gave for people with mental illness due to receiving a limited amount of information and having a limited understanding of their colleagues or employees with a mental illness

This lack of understanding may affect the perception that PWOMI have about those with a mental illness, the way in which they view a mental illness and the challenges that people who have a mental illness face in their everyday life16. Krupa et al.30 support this finding in their research on understanding the stigma around mental illness and employment. They found that there were five assumptions made in the workplace regarding workers with a mental illness. These were (1) the assumption of incompetence, (2) the assumption of danger and unpredictability, (3) the belief that mental illness is not a legitimate illness, (4) the belief that working is unhealthy for persons with mental illnesses, and (5) the assumption that employing these individuals represents an act of charity inconsistent with workplace needs.

In this current study, five different work sectors were explored. In the business sector all the PWOMI rated the level of challenge posed by worker characteristics of people with mental illness as significantly greater than the PWMI themselves. There was also a significant difference for all 38 characteristics for the participants who work in the public sector, which includes health, social services, education, government, and recreation. It is expected that some of these participants would have a more comprehensive knowledge of mental illness as the topic of mental illness is covered in their training, namely psychology and sociology. The sector that had the least significant difference between the means rating challenges related to worker characteristics was the construction sector. The participants in this sector may or may not have any tertiary education, but often undergo practical training. In research conducted by The Centre for Construction Research and Training31, the education level of those employees working in the construction field is lower than those in most other industries and some of the worker characteristics listed such as 'possessing adequate academic skills' (Characteristic28), may not apply in this sector. The construction sector has jobs that require little contact or difficult interactions with the public. They are less likely to be challenged by worker characteristics in low-skilled jobs with little need for adapting to different job tasks and resolving conflicts, which may result in lower levels of stress and mental illness in this sector32. The worker's exposure to formal education regarding people with a mental illness may not be as great for those who work in this sector32. This may account for the lower number of significant differences in ratings between PWMI and PWOMI, in this sector.

This study showed that the difference in ratings between female PWOMI and PWMI was significant for all worker characteristics. This finding was expected since research has shown that mental illness is more common in women than in men5 and the intensity and persistence of mental illness may be higher in women33,34 and that women would be more understanding of the challenges mental illness presents in the workplace. Results suggest, however, that male PWOMI, who had no significant difference compared to male PWMI on five worker characteristics, are more understanding and more realistic than female PWOMI, about the challenges PWMI face around social engagement in the workplace, punctuality and taking pride in their work.

When looking at the affect that age group had on the difference in the mean ratings between the two groups, the participants who were in the age group 36-45 years had the most ratings with no significant difference (19 out of 38) for worker characteristics. These participants may have more work experience and thus more exposure to people with a mental illness. It is plausible that, at a company, employees who are in the 36-45 years age group are in managerial positions and are accustomed to assisting and guiding their subordinates. This may explain the better understanding and perception they have of people with a mental illness. The youngest age group, 18-25 years old, had five characteristics with no significant difference in the mean ratings. This younger age group may be more active on social media35 and their awareness and exposure to mental illness may be better, thus explaining more similar ratings than some of the other age groups. Currently, there are many campaigns36 and increased awareness of people with a mental illness on social media. In a study by Latha et al.37 using social media to promote mental health campaigns was found to be an effective initiative as many people can be reached and exposed to the campaign over a short space of time. They also found that there is an increasing trend in mental health awareness due to digital media as a way of distributing information.

The participants in the 26-35-year age group have most likely just started working or have a few years work experience, thus their association with people with a mental illness may be lower, explaining mean ratings for all 38 characteristics having a significant difference. The participants in the highest age group (56-65 years), also showed a significant difference in the mean ratings for all 38 characteristics. Although they are expected to have the most work experience in the sample and, as such, more exposure to employees with a mental illness, the discussion of mental illness is a recent subject in society. In the past, mental illness was a taboo topic38 with a negative connotation attached to it. These older participants have only recently started becoming aware and more accommodating of people with a mental illness.

The results of the study have implications for occupational therapy practice when providing or suggesting reasonable accommodations for people with a mental ill-ness19. Although there was a significant difference in all 38 characteristics, PWOMI, can identify some of the struggles that PWMI are having in the workplace, although the level of the challenge the worker characteristics present is perceived as greater. Possible resolutions to this would be more education and awareness of mental illness in the workplace for a better understanding of the struggles and challenges that people with a mental illness face. Focus can be applied to PWOMI that are females, working in the public and business work sectors and in the age ranges 26-35 and 56-65 years.

Understanding worker characteristics seen to present challenges in the workplace can assist occupational therapists in providing education to improve support from work colleagues and employers and suggesting specific accommodations to facilitate work performance for employees with mental illness. Qualitative research could be used with PWOMI to establish what education or information they need to better accommodate and understand PWMI in the workplace. Other research could focus on PWMI or PWOMI separately, to determine their ideas and suggestions for change and accommodations in their workplace. These can then be reviewed and implemented for a better cohesion and understanding between PWOMI and PWMI.

Limitations of the study

Not all diagnoses are present in the sample and the frequency of some of the diagnoses were limited, thus impacting the generalisability of the findings. The severity and accuracy of the reported mental illnesses were not considered, which may have further explained the findings in the study, as this may impact the number of challenges they face in their workplace. The visibility of the mental illness symptoms may also influence the way PWOMI view people with mental illness and their understanding of their functioning.

It was anticipated that the sample size would be restricted by limited access to online facilities and low levels of literacy in the South African context. This was due to the online nature of questionnaire needing internet access and the questionnaire only being available in English, one of the eleven official languages in South Africa. Many South Africans may not have access to internet, which therefore limited participation in some of the working sectors, mainly construction and manufacturing, with a lower response-rate found in these sectors. Printed questionnaires may have allowed for inclusion of more participants from these sectors.

The underlying perceptions and ideas were not explored, thus limiting the amount of reasoning underlying the selection of the ratings for the participants.

The effect-size of the data was not calculated to show the magnitude of the phenomenon of the mean differences between PWOMI and PWMI. However, it is not expected that this would affect or influence the results of the study as a large sample was used with high significant values found to reject the null hypotheses.

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded that PWOMI rate the likelihood of people with mental illness having greater challenges related to specified worker characteristics at work than PWMI; although age, gender and work sector may impact on the significant difference. PWOMI who were male, working in construction and in the 36-45 age group, had more ratings that were not significantly different from those of the PWMI, indicating their perceptions of the challenges faced by people with mental illness in the workplace were more comparable. These results have implications for occupational therapy practice, as reasonable accommodations for people with a mental illness often need to be made at their work and this research gives insight into which worker characteristics are viewed by PWOMI and PWMI as presenting challenges for people who have a mental illness in the workplace.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Upon reasonable request the data is available from the principal author, Danielle on danielle.michael@hotmail.com

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no known conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

This research was conducted by Danielle Michael for a European MSc. OT degree through the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. Danielle Michael was the primary researcher, conducted the research and wrote the first draft of the article. John Wright supervised the study, guided the research, co-authored and edited the article.

REFERENCES

1. World Federation of Occupational Therapy. [Online].; 2018 [cited 2019 June 4. Available from: http://www.wfot.org/AboutUs/AboutOccupationalTherapy/DefinitionofOccupationalTherapy.aspx [ Links ]

2. Desiron HA, de Rijk A, Van Hoof E, Donceel P. Occupational therapy and return to work: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11(1): Article 615. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-615 [ Links ]

3. The Republic of South Africa. The Mental Health Care Act. Act No. 17. Government Gazette. 2002; 449(24024): 10. [ Links ]

4. Maja P, Mann W, Sing D, Steyn A, Naidoo P. Employing people with disabilities in South Africa. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 41(4): 24-32. [ Links ]

5. World Health Organization. WHO. [Online].; 2019 [cited 2019 June 4. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/gen-derwomen/en/. [ Links ]

6. Blank L, Peters J, Pickvance S, Wilford J, MacDonald E. A Systematic Review of the Factors which Predict Return to Work for People Suffering Episodes of Poor Mental Health. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2008; 18(1): 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-008-9121-8 [ Links ]

7. Follmer KB, Jones KS. Mental illness in the workplace: An interdisciplinary review and organizational research agenda. Journal of Management. 2018; 44(1):325-51. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0149206317741194 [ Links ]

8. Jansson I, Gunnarsson AB. Employers' views of the impact of mental health problems on the ability to work. Work. 2018;59(4):585-98. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-182700 [ Links ]

9. Diksa E, Rogers E. Employer concerns about hiring persons with psychiatric disability: results of the employer attitude questionnaire. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin. 1996; 40(1): 31-44 [ Links ]

10. Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk S, Czobor P. A Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Remediation for Schizophrenia: Methodology and Effect Sizes. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011; 168(5): 472-485. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060855 [ Links ]

11. Spaulding W, Sullivan M. From laboratory to clinic: psychological methods and principles in psychiatric rehabilitation. In RP L, editor. Handbook of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1992. P. 30-55. [ Links ]

12. Kvaale E, Haslam N, Gottdiener WH. The 'side effects' of medicalization: A meta-analytic review of how biogenetic explanations affect stigma. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013 Auguat; 33(6): 782-794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.06.002 [ Links ]

13. McDowell C, Fossey E. Workplace Accommodations for People with Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2015 March; 25(1): 197-206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9512-y [ Links ]

14. Waddell G, Burton K. Is work good for your health and well-being? Norwich: The Stationery Office; 2006 [ Links ]

15. Sharac J, Mccrone P, Clement S, Thornicroft G. The economic impact of mental health stigma and discrimination: A systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2010 September; 19(3): 223-232. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1121189X00001159 [ Links ]

16. Schulze B, Angermeyer M. Subjective experiences of stigma. A focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives and mental health professionals. Social Science & Medicine. 2003 January; 52(2): 299-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00028-X [ Links ]

17. Leufstadius C, Eklund M, Erlandsson L. Meaningfulness in daily occupations among individuals with persistent mental illness. Journal of Occupational Science. 2009 April; 15(1): 27-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686604 [ Links ]

18. Eklund M, Hansson L, Bejerholm U. Relationships between satisfaction with occupational factors and health-related variables in schizophrenia outpatients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2001; 36(2): 79-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050293 [ Links ]

19. American Occupational Therapy Association, "Occupational Therapy Practise Framework: Domain & Process 4th Edition," The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 202; 74(Suppl. 2):. 7412410010 https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001 [ Links ]

20. The Republic of South Africa, , "The Equity Employment Act," Government Cazette, p. 400 19370, 1998 [ Links ]

21. Khalema N, Shankar J. Perspectives on Employment Integration, Mental Illness and Disability, and Workplace Health. Advances in Public Health. 2014; 2014: 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/258614 [ Links ]

22. Yilmaz K. Comparison of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Traditions: epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. European Journal of Education. 2013 June; 48(2): 311-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12014 [ Links ]

23. Kielhofner G. Descriptive Quantitative Designs. In Kielhofner G. Research in Occupational Therapy - Methods of Inquiry for Enhancing Practice. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company; 2006. P. 58-64. [ Links ]

24. STATS SA. Quarterly employment statistics. Statistical Release. Pretoria: Republic of South Africa, Statistics South Africa; June 2018. Report No.: P0277 [ Links ]

25. Tomita M. Methods of Analysis: From Univariate to Multivariate Statistics. In Keilhofner G. Research in Occupational Therapy: Methods of Inquiry for Enhancing Practice. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company; 2006. p 243. [ Links ]

26. Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research methods in education. London: Routledge; 2018. [ Links ]

27. Hand C, Tryssenaar J. Small business employers' views on hiring individuals with mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2006; 29(3): 166-173. https://doi.org/10.2975/29.2006.166.173 [ Links ]

28. Arndt J, Fujiwara E. Interactions Between Emotion Regulation and Mental Health. Austin Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2014 May; 1(5): 1-8. [ Links ]

29. Mamacos E. careers24. [Online].; 2016 [cited 2019 June 5. Available from: https://careeradvice.careers24.com/career-advice/work-life/mental-illness-disability-south-africa-work-place-20160601 [ Links ]

30. Krupa T, Kirsh B, Cockburn L, Gewurtz R. Understanding the stigma of mental illness in employment. Work. 2009; 33(4): 413-425. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2009-0890 [ Links ]

31. The Center for Construction Research and Training,, "Educational Attainment and Internet Usage in Construction and Other Industries," 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.cpwr.com/research/data-center/the-construction-chart-book/chart-book-6th-edition-education-and-training-educational-attainment-and-internet-usage-in-construction-and-other-industries/. [Accessed 19 March 2021] [ Links ]

32. "Depression Among Demographics and Professions," 24 February 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.mentalhelp.net/depression-among-de-mographics-and-professions/. [Accessed 16 May 2020] [ Links ]

33. Herman A, Stein D, Seedat S, Heeringa S, Moomal H, Williams D. The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. South African Medical Journal. 2009; 99(5): 339-344. [ Links ]

34. Meintjes I, Field S, van Heyningen T, Honikman S. Creating capabilities through maternal mental health interventions: A case study at Hanover Park, Cape Town. Journal of International Development. 2015 March; 27(2): 234250. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3063 [ Links ]

35. Villanti AC, Johnson AL, Ilakkuvan V, Jacobs MA, Graham AL, Rath JM. Social media use and access to digital technology in US young adults in 2016. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2017;19(6):e7303. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7303 [ Links ]

36. Mental Health Foundation. Mental Health Foundation. [Online].; 2019 [cited 2019 June 5. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/s/stigma-and-discrimination. [ Links ]

37. Latha K, Meena K, Pravitha M, Dasgupta M, Chaturvedi S. Effective use of social media platforms for promotion of mental health awareness. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2020;9(1):124. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_90_20 [ Links ]

38. Stuart H. Fighting the stigma caused by mental disorders: past perspectives, present activities, and future directions. World Psychiatry. 2008 October; 7(3): 185-188. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00194.x [ Links ]

* Corresponding Author: Danielle Michael. Email: danielle.michael@hotmail.com