Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.51 n.4 Pretoria Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2021/vol51n4a3

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

SPECIAL EDITION

Human Praxis as Possible Innovation for Occupational Therapy Practice: An Interpretivist Description from People who Enact Praxis

Tania Rauch van der MerweI, *; Lindi BassonII; Roxanne BuschowIII; Tihani CrousIV; Armunay GillmerV; Melicia MullerVI; Jean-Marie NiemannVII

IB. Occ. Ther. (UFS); M. Occ. Ther. (UFS); PhD Higher Education Studies, Interdisciplinary (UFS). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5751-2707; Senior Lecturer, Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Health Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa

IIB. Occ. Ther. (UFS). https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1453-0355; Occupational Therapist, Greymil Rehabilitation, Bloemfontein, Free State, South Africa; All co-authors were B.OT students at the University of the Free State (UFS) at the time of carrying out this study

IIIB. Occ. Ther. (UFS). http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4134-3977; Private Practitioner, Rita Hen & Partners Inc. Bloemfontein, Free State, South Africa; All co-authors were B.OT students at the University of the Free State (UFS) at the time of carrying out this study

IVB. Occ. Ther. (UFS). https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5759-0433; Private Practitioner, N. Burger Occupational Therapists, Kathu, Northern Cape, South Africa; All co-authors were B.OT students at the University of the Free State (UFS) at the time of carrying out this study

VB. Occ. Ther. (UFS). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1801-0755; Occupational Therapist, Lantern School, Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa; All co-authors were B.OT students at the University of the Free State (UFS) at the time of carrying out this study

VIB. Occ. Ther. (UFS). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9711-9133; Private Practitioner, Juliet Shehab Occupational Therapists, Bloemfontein, Free State, South Africa; All co-authors were B.OT students at the University of the Free State (UFS) at the time of carrying out this study

VIIB. Occ. Ther. (UFS). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4713-2639; Occupational Therapist, Bloemfontein, Free State, South Africa; All co-authors were B.OT students at the University of the Free State (UFS) at the time of carrying out this study

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The term 'human praxis' has been referred to in an array of theoretical frameworks: philosophy, institutional change, education, and critical theory. Broadly, human praxis denotes human agency towards personal and collective transformation in the wake of various kinds of constrictions, regardless of external interventions. If occupational therapy can understand the mechanisms of human praxis, it could be used as a potential therapeutic tool leading to the improvement of health and well-being within communities at large

METHOD: Eight individuals actively living human praxis participated in semi-structured interviews. Purposive sampling, and eligibility criteria based on a description of human praxis synthesized from literature, were employed. Six researchers independently performed a manual qualitative thematic analysis of the transcribed interviews, which served as method triangulation

FINDINGS: Data analysis revealed that human praxis exists as a dynamic, and recursive two-phase process, consisting of initiators (Theme I), and continuous enablers (Theme II). In addition, seven categories (constituents) emerged from each of the two themes

CONCLUSION: Human praxis can be applied in the conscious facilitation of the interdependence between the various constituents such as the individual and the collective, personal and ongoing shared responsibility, and between conditions of constraint and resilience toward self-determination and growth

Keywords: wound management, hand therapy, occupational therapy, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

INTRODUCTION

Human praxis, a form of human agency, is a concept that is more general than abstract as it is employed in several disciplines for discipline-specific purposes, which will be discussed below. In occupational therapy, human praxis would most closely relate to the notion of agency or internal motivation1. Though, the process of human praxis is far more complex and resonates strongly with the characteristics of complexity theory, e.g.: consisting of several interactive elements; marked by small actions having large, continuous, and ongoing effects and influence; and its process being is non-linear2. The carrying out of human praxis is intrinsically connected to the person's holistic functioning and the contextual environment s/he forms part of 3|4,5. However, while occupational therapy would understand the complexity of human function, and theoretically understands the ripple effects that internal motivation has for human health and well-being, it also does not yet quite understand fully, how to elicit internal motivation that is ongoing and has constant effects when working with adults. Why is it that some people fail to continuously build on the occupational therapy interventions they receive? Or, why do some people with little or no therapeutic intervention after, or during injury, or illness or trauma, manage to not only reconfigure their own lives but also exert that change and transformation beyond themselves into the communities they form part of? Think of for example Helen Keller (1880-1968), the iconic scholar, poet, and political activist who was born deaf and blind. Another striking example is the narrative of Zama Mofokeng, 26 years old and who set a Guinness Book record in 2017 and again in 2021, for the most single hand backflips. He lives in a township in Gauteng, taught himself gymnastics after a car accident and subsequent epilepsy, and set the world record to prove resilience despite epilepsy, and demonstrate to the children in his community that one can overcome challenges6. Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, perhaps the most striking example of collective human praxis is the development of a vaccine in less than a year7. That may bring us to the following question: what value can praxis have for universal health care?

The health department of South Africa's mission states: "To improve health status through the prevention of illnesses and the promotion of healthy lifestyles and to consistently improve the healthcare delivery system by focusing on access, equity, efficiency, quality, and sustainability"81. If the occupational therapy profession can access and understand the mechanisms of human praxis as a therapeutic tool, it may be able to contribute to a health care model in which people are consciously facilitated to act as change agents, not only for themselves but also to expand this form of agency to the rest of immediate communities. This study explores how people who enact praxis; describe their process of human praxis.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The concept of human praxis and its assimilation in occupational therapy

The concept of human praxis is referred to in similar versions across disciplines and theoretical frameworks such as philosophy, institutional change theory, education, and critical theory, 9,10,11,12,13. For example, in philosophy, Aristotle, an ancient Greek philosopher and scientist, denoted praxis as a human activity undergirded by practical knowledge as a means, ultimately toward action through doing, as an end12. Within organizational change theory, Seo and Creed (2002) define praxis as collective human action that involves a highly dialectic process in responding to the inertia of organizational status quo, and the desired changes for the good11. Pertaining occupational therapy, for example, in a study exploring the interface between Galvaan and Peter's14 Occupation-based Community Development approach, and praxis, Mackenzie Krenzer15 relies on Freire's definition of praxis as a point of departure: i.e. the iteration between reflection and action in the real world toward transformation16,17. Based on readings (included in this article's reference list), observation, and innumerous discussions with interlocutors (see Acknowledgements) on the phenomenon of human praxis, the first author describes human praxis as: An astute awareness of oneself and the environment one forms part of, as well as the informed and accurate historical self-reflection that enables one to see both the challenges and the opportunities at once. This posture results in actions, in the sense of 'doing in the real world' that not only lead to a transformation of that person but also the community and environment that the person forms part of. An internal locus of control and an openness to learning, also form part of praxis18.

Within occupational therapy, praxis is also a term that is used in Sensory Integration to denote motor planning in the sense of how to plan, organize and carry out a sequence of unfamiliar actions within one's physical environment; how to do what one intends in an efficient manner19. However, the concept of human praxis as a form of human agency seems yet to be assimilated in occupational therapy theory. Human agency is partly explained in occupational therapy to consist of one or more occupational therapy components such as levels of motivation and specifically internal locus of control. The Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability20 to a certain extend, encapsulates the levels of volition that result in various levels of action. Imbibing the notion of human praxis into the theory of occupational therapy for practise, may therefore be very helpful to occupational therapists within the context of primary health care and scarce resources in South Africa.

Global health care reform and the need for self-sustaining communities in the South African context

Global health care reform, perhaps amidst a global pandemic now more than ever, refers to the global shift of maximum health care to all of a country's citizens that is affordable, effective, dignified, and sustainable. However, the ratio of health carers to people who need health care services in South Africa far exceeds the feasibility of quality health care. Less than 20% of South Africans have access to full or partial medical health insurance21. In 2020, there were 5 638 registered occupational therapists and 59 308 690 citizens in South Africa22,23. Thus the ratio of occupational therapists to citizens is 1:10 500. In striving towards quality health care, and overcoming this impossible ratio, community-based occupational therapy practice can act as an approach to reach more people who need occupational therapy. Against the backdrop of the South African Government's plan of implementation of the National Health Insurance, the focus has increasingly been moved to primary health care, which renders occupational therapy community-based intervention more relevant. However, given the increasing socio-economic challenges in South Africa, and a low number of occupational therapists employed in primary health care, the change appears to be incremental.

Within the field of organization theory, human praxis has been identified as an essential aspect of change and humans are viewed as being able to act as active agents in intentionally bringing about change11. If occupational therapy can access and understand the mechanisms of human praxis as a therapeutic tool for conscious facilitation of human agency, occupational therapists can better enable communities' potential growth and self-determination, and contribute to health care having a more far-reaching effect. It may therefore contribute to the responsiveness of a public health care system, an important component highlighted by the WHO24.

It is evident that clients who have the capacity of autonomy, play a significant role in protecting their health, understanding the cause of their illness, and taking suitable action. Therefore, it is imperative for health care strategies to be put in place to support these roles on the one hand25. On the other hand, a balance needs to be struck without burdening health care users with the notion that their illness/injury is their duty to overcome26. There is however a gap in the literature with regards to what constitutes human praxis and how this links to agency for self and others in occupational therapy. Specifically, against the backdrop of questions such as: Why do some people transcend constraints and enact a transformation in an entire community that they form part of? How do some people with or without occupational therapy intervention, not only radically change their circumstances but also manage to carry over this change to the nucleus community they are part of?

AIM

The study aimed to describe the process of human praxis through the subjective accounts of people who enact human praxis.

METHODOLOGY

The study method drew from the interpretive research paradigm and a qualitative descriptive type of inquiry toward understanding the world from the subjective experiences of individuals27. This study design is thus fitting since it gives the researchers the research lens to describe the process of human praxis through the subjective accounts of people who enact it in their lives.

Participants

The study's population included individuals from three districts in the Free State Province in South Africa. These districts vary from peri-rural to urban. The individuals were from various races, gender, age, and socio-economic descriptors as shown in Table I (above). This heterogeneity of demographics was a potential contributor to the internal validity of the findings. The researchers made use of purposive expert sampling. Firstly, the researchers approached an expert occupational therapy clinician who oversees community-based practice and education within the ambit of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of the Free State. In collaboration with this expert, eight participants were identified. The eligibility criteria were compiled mainly based on the description of human praxis synthesized from literature as provided in the introduction of this article (See Appendix A, p2l). Two of the eight participants were approached for the exploratory study and the data generated during the study was included since the interview questions were not altered.

Data collection

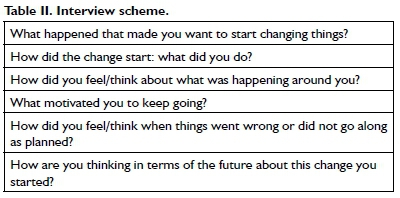

Data collection procedures entailed employing individual, semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions. The interviews commenced with the following statement and question: "You have been identified as an individual who has made a significant change within your community. Please tell me this story?" An interview scheme was used to prompt conversations further when needed (Table II, p16). This interview scheme was compiled from the descriptions of human praxis synthesized from literature. One interviewer interviewed all eight of the participants, individually. One observer formed part of each interview with the role of taking field notes. All interviews were voice recorded for which written informed consent was obtained. All questions according to the interview scheme were answered at the time the interview ended. Each interview was transcribed verbatim, shortly after each interview, in preparation for data analysis.

Data analysis

The first set of three interviewers independently performed a manual qualitative thematic analysis of the interviews before sending the coding to the second set of three researchers. This served as method triangulation. Each set of researchers made use of inductive, open coding to explore the participants' experiences rather than fitting the findings to theory (Figure 1, above). Following the coding done by the second set of researchers, codes were collectively consolidated toward about 23 categories (units of meaning). Following this step, a second coder (occupational therapist with postgraduate qualifications) followed all of the above steps after which the final names of the themes and consolidation of 23 categories into a total of 14 were done. Code saturation28, especially in terms of the two main themes, commenced during the analysis of the sixth interview. In terms of trustworthiness, credibility was ensured by using field notes, triangulation in terms of data sources and literature, as well as negative case analysis. Dependability was maintained by using one consistent interviewer per participant with a set interview scheme and having a detailed description of data collection. Confirmability was done by auditing the data collection process, as well as submitting for peer-reviewing (the study supervisor). The purpose of this study was however not to necessarily attain transferability as it is contextual, and transferability is therefore for the reader to infer.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Free State with the ethics number UFS-HSD20I8/0I45/2404. The overarching principles for research ethics namely beneficence and non-maleficence, respect for persons (dignity and autonomy), and distributive justice (equality), were adhered to. The informed consent sheets included the stipulation of the findings possibly being published. The participants were given the choice to keep their information anonymous because of honouring their egalitarian position as a participant, and contributions made in the various communities. Only the researchers and authors of this study have access to the raw data and it will be destroyed as soon as its relevance for publication and dissemination for the greater good has been met (according to Sections 13-14 of the POPIA draft Code of Conduct for Research)29.

FINDINGS

After analyzing the data, two themes emerged comprising of seven categories each. The first theme is Initiators of praxis and the second theme is Continuous enablers (Figure 2 above, constructed by the authors). This process egresses as being recursive, dynamic, and non-linear, with both parts influencing each other.

Theme I: Initiators of praxis

The first theme surfacing represents the first phase in the process of human praxis, which expands into seven categories that all participants of this study had in common. These categories appear to be the origin of the process of enacting praxis, and the reason behind initiating change. An initiator, when referred to as an object, can be described as something that "starts the decision-making process by recognizing that a particular problem needs to be addressed to satisfy a specific need."30:1

The first category expresses how all eight participants described having a vision as one of the reasons for wanting to initiate change. Participants explained that they had to have a full understanding of the past, and a vision that is used as a guide towards the future. This helps them guide their actions to reach their desired outcome. The person's future vision might grow as s/he continues to walk the chosen path, but it is still in correspondence with the envisioned destination31,32. The following participant explained it as:

"I started a skate park in Bloemfontein about four years ago where I had the same dream to make a difference -uhm just to give the kids a different set of role models and a different environment..." LM

The second category is having a personal reason to start. All eight participants articulated that the need for change was, without exception, personal to the respective individual. All of the participants became active change agents because something happened in their lives that made them want to bring about a transformation, starting with the self but also because they identified with others in the community having similar struggles. The following verbatim quote of a participant in a peri-rural area teaching children how to play chess as a recreational activity, depicts this:

"I wanted to change things in the community because of myself. I was in special needs class before, and I know how it feels". GM

All eight participants reported the notion of doing it in everyday life for the self and the community as a form of an initiator to praxis and a third category. People who enact praxis in their lives, see the needs in the community as well as their purpose and meaning in life. A community consists of more than just an individual's geographical location but can be defined as a group of people who have a diverse set of characteristics though they are all linked by means of a common goal. Furthermore, a community refers to a person's natural habitat, and where these individuals experience meaning in life. Humans want to engage in purposeful and meaningful activities and experience a sense of mastery33. If an individual identifies with a purpose in life, this purpose can drive the person's actions and doings in daily life toward the collective good and what s/he does on a daily basis32,34. The following verbatim quote illustrates this notion:

"I wanted to change things in the community because of myself. I was in special needs class before, and I know how it feels... And I would like someone if I'm getting older like you say I would like someone else, younger to come and do the same thing over and over cause that's a good thing". GM

The data revealed that individuals who enact human praxis daily, make use of their fields of expertise to initiate change within themselves and the community. The fourth category - working with what you know, describes how knowledge, skills, and experience true to each individual, guides their decision toward the change they are working towards. This refers to the facts, information, and skills that they have acquired through practical involvement and life experience35,36,37. The following participant who has started a running club in a peri-rural area among members of a marginalized community illustrates this:

"...so, I check that they, I just because I know, I have had some experience with the athlete, so I try to teach them how you can run and maybe all the time prepare for the competition..." TN

Taking the first step at the face of apprehension, was the fifth category that all eight participants agreed upon. Though all of the participants mentioned having doubts, it did not stop them. They continued even though they did not necessarily expect success38,39,40. The following participant - a healthcare worker who started and maintains a day-care centre for people with severe disabilities:

"Initially, I was very nervous, because it was something completely new, someone else has not tried it, do you understand? There was no one who I could ask for advice". BA (Translated from Afrikaans to English)

Within the process of praxis, conditions of constraint are not only a given but also a decisive initiator (sixth category). Conditions of constraint can be defined as an intrinsic or extrinsic state, leading to restrictions such as time, cost and scope, which determine limitations within a certain project. Limitations can pertain to a project's quality, effectiveness, or successes4l,42,43.

"...it's never going to be smooth sailing uhm, so there, there have been obstacles and challenges along the way, uhm but the team of people that are involved have been very supportive to coming up with the best possible solution for that specific challenge or obstacle". JM

As a final and seventh category, all participants shared a common quality of readiness to solve problems. This refers to being prepared for something, and so being able to respond rapidly when an opportunity for problem-solving arises. People who enact praxis, can be creative when dealing with problematic situations to respond most effectively44,45,46. The following verbatim depicts this category:

"So I build this sit-to-stand standing frame and what, it was very expensive, it cost like 30 grands, and we built it for something like, R3 000 [ZAR] or something like that, it was crazy... we gave it to the family and the first day that child came to test out the apparatus, the child started like smiling and laughing and the parents started crying, like really like, they started like bawling... and the parents said that it was the first time they saw their child like, laugh". AS

Theme II: Continuous enablers of human praxis

The second theme emerged, also from seven categories that together form the second phase in human praxis. These continuous enablers follow from the initiators of praxis. They indicate the threshold of where the person who enacts practice, takes the changes/turnaround experiences within him/herself toward application, with ongoing effects in the broader community s/he forms part of. The person seems to then become a change agent, and proceeds by transposing the change experienced in the self to the surrounding community and collective. Of note is to see how a personal responsibility, becomes an ongoing shared responsibility. Following are the findings of each of the seven categories of continuous enablers.

The first continuous enabling category for ongoing human praxis is a person's ability to sustain her/his eye on the future, meaning the ability of the person on how to ideate changes as sustainable and enduring in the future:

"I want to see it carry on and grow higher and higher." TN

All eight participants identified with the second category, the ability to use opportunities when they arise. The participants enacting human praxis in this study are able to see opportunities that are aligned with the desired change, which they subsequently can make the most of, toward change for the better of the common good47,48.

"So...that is what I saw then, it is...where the gap is. That gap is those guys who are now too big and then next gap which...we realised, is the children all go to school until they are 18 years old...but at the moment when they turn 18 years old, when they have passed that period then there is no other care for them". BA (Translated from Afrikaans to English)

"...then I told myself, [the participant referring to himself by name], that when an opportunity comes your way, please take it". GM

With human praxis being an ongoing process, the sharing of information between individuals, businesses, communities, teams, or organizations takes place - an element that all eight participants referred to.The third category - sowing seeds for change describes how the sharing of knowledge feeds the cycle of growth within the human praxis process and is used to continue creating something novel49,50,51. As two participants describe when referring to their projects:

"So, the idea is to sow into their lives, and then at the end they have to sow into others' lives through what they received'. PK (Translated from Afrikaans to English)

"I think the change that I started, somebody else will continue. The ones that I've helped will always, also wants to help others, because they have also been helped by someone..." AR

Within the process of human praxis, the findings reflect that the projects for change often have a snowball effect and expand as a result of knowledge being shared (fourth category). Furthermore, for the process of human praxis to continuously grow, balance is to be kept between all forces in play. At a specific point in time, the joint effect of these forces is significantly greater than the sum of their parts52,53,54. All participants reflected on how the journeys they embark on, snowball to something greater. One example illustrates:

"So, once we can officially launch the project, and get the word out there, I think then it's really going to be a snowball effect and I'm looking forward to seeing the effects and outcomes of the project". JM

The fifth category of the theme 'continuous enablers', shaping partnerships emerged strongly from all eight of the participants' transcriptions. A partnership is a shared relation as well as commitment among people across various ambits such as a business, community, family, or team. All partners have the obligation in terms of their personal strengths and resources, to be of advantage to each other and possibly their surrounding community55,56. This is depicted by the following verbatim:

"If you are willing to do things in the organisation and to be available, then there are other people that will buy into the project and yes it was nice to realise: you don't have to do everything alone". PK (Translated from Afrikaans to English)

Six of the eight participants reported spirituality (the sixth category) in one or another form, as being part of their consciousness. Theoretically, spirituality seems to be an intrinsic part of being human. This links with human agency because humans are spiritual beings who tend to seek connectedness to the world around them, as well as often to a higher power. The innate need to both connect with fellow human beings, as well as a higher power, is often used to guide the behaviour of people who enact praxis, and give meaning to their actions17,57,58,59. Participants described this as follows:

"That... what's for me, it's that pure fact that you feel close to your Creator when you create, and I think for me that's, that what really drives me, I think innovation and creativity". AS

"...actually, [as human beings] we are supposed to go out and help where we are needed and where there is a big need". PK (Translated from Afrikaans to English)

The final and seventh category, resilience means the ability to adapt and insightfully move forward after one has experienced some adversity or form/s of disruptions in life. This adaptation is consciously located in human agency and from an internal locus of control, where the person believes in his or her abilities to bring about change. Being resilient means that one is positive, persistent and can see failure as helpful feedback60,61,62. Resilience is illustrated by the following verbatim by a participant who is a teacher at high school in a peri-rural area, supporting children to academically achieve so they qualify for university bursaries. AR is well known in the region and the school as some of the students he had taught, and who are recipients of education bursaries, opt to return to their alma mater to intern as teachers at this school where the participant is still teaching:

"I always have this thing, uhm, the first try it's not your best. You must try again and again and again until what you want becomes a reality. So, keep on trying for the second time and make the first mistake right and then you get it right". AR

DISCUSSION

This discussion puts forward an interpretation of human praxis as a dynamic, recursive11,62,63, and two-phase process consisting of initiators and enablers. This process is recursive because both the initiators and the enablers are defined in terms of each other, and are therefore interdependent. For example, all the participants enacting praxis, shared how change was initiated with both a personal reason to start as well as doing it in everyday life for the self and the community. The person starts by reflecting accurately on a situation that needs to change for the better because of personal experience64, which may inform the practical wisdom needed for praxis65,66. This reflection involves an accurate assessment of how the past has given shape to the present and seems to be at once followed by taking the responsibility of ideating a real-world solution toward transformation and change16,32 (by having a vision). To give form to the ideated change, people who enact praxis embrace the importance of shaping partnerships, by sharing their vision that often leads to a snowball effect toward collective change67,68,69. In this way, a personal responsibility evolves into a shared, and ongoing responsibility because of being aware of, and understanding themselves to be part of a whole. Perhaps one can here then argue for the initial, atomistically perceived individual-collective-divide, to be re-situated in a majority world context that illustrates less a dichotomy than an interconnectedness between the individual and the collective70. A point strongly resonating with Ramugondo and Kronenberg's explanation of collective occupation and the implicit recursive nature of Ubuntu as an 'African interactive ethic"7111.

Furthermore, the human praxis process seems more looping than iterative, because it does not have an endpoint, but is ongoing. For example, the person initiating praxis by having a vision for change employs this foresight and practical reasoning to sustain an eye on the future as a continuous enabler for changes to be ongo-ing72. Another example is how the person who enacts praxis, accurately reflects on their own ability and skills, subsequently utilizes this knowledge (working with what you know) as an initiator of praxis. The person then continuously and with intent71, shares this knowledge with the collective/immediate community that serves as a continuous enabler - feeding an ongoing cycle of growth49,51 (sowing seeds for change).

However, central to the mechanisms of human praxis appears to be also the given of conditions of constraint, as an initiator, and resilience as an enabler. It seems that people who enact praxis, consciously anticipate conditions of constraint as well as probable failure with initial attempts. They are however not deterred by it but deliberately use the lessons learned to occupationally adapt toward realizing a solution to occupational challenges73. This posture underscores an openness to learning: not taking failures personally or viewing them as defeat, but purposely applying gained insights to grow and develop existing knowings74,75.

The exploration of how people who enact praxis, describe praxis, is a first step toward unearthing further how human praxis operates as a form of human agency. The following implications for research and practice may be relevant:

In terms of research, several expansions are suggested. First, replicating the research in various geographic and cultural contexts and with larger numbers of people to explore and compare similarities. Second, exploring specifically how each of the various constituents of the initiators and enablers of human praxis function, their relation to one another, as well as their relation to, for example, occupational needs and occupational well-being76,77. Third, to unearth, also in practice, how the critical relation between individual and collective agency intersect with the implicit recursive nature of Ubuntu75, especially so for the global South context, and the inherent collective nature of praxis. In other words, how does individual agency, and responsibility, link with collective agency and responsibility, and how does the collective contribute to shaping the human praxis process into a recursive ongoing process?

Regarding practice, we recommend exploring to which extent the various constituents of initiators and enablers are present within transformative projects in various communities, and collectively articulating them in our work with community-based stakeholders, including stakeholders who are potential partners for community-based projects.

Furthermore, to facilitate with intent, each of the constituents of human praxis during therapeutic sessions.

Finally, to consciously facilitate the posture of openness to learning that requires anticipating conditions of constraints, the willingness to make mistakes, and subsequently move forward with insights gained.

LIMITATIONS

Possible limitations include the small number of participants (though coding saturation was reached), as well the fact that the study is bound by geographical limitations. It is therefore recommended that the study is repeated in various contexts e.g. all provinces of South Africa that include metropolitan and rural areas, and with a larger number of participants toward reaching meaning saturation29 as alluded to above.

CONCLUSION

The phenomenon of human praxis is found to occur within a two-phase process that is dynamic, and recursive. These phases each include seven elements that are interdependent, and which initiate human praxis and enable the ongoing process of human praxis. Given the scarcity of resources (including occupational therapy services) as well as the high prevalence of people who are poor in a developing country such as South Africa, intentionally facilitating human praxis as a therapeutic tool that may ignite human agency to bring about change within communities, could alleviate these imbalances.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly the authors would like to acknowledge with gratitude the participants' willingness to share their open-mindedness and insights. Secondly, thank you to the interlocutors during the conceptualization, protocol development, and data analysis of this project. In particular, Ms. Heidi Morgan from the Department of Occupational Therapy at the University of the Free State who assisted also in the purposive expert sampling; Mr. André Zaaiman from Mindsight Intelligent Enterprises Systems who has a longstanding experience of human praxis across the African continent; and Mrs. Juanita Swanepoel from the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of the Free State, who assisted also as co-coder. Finally, sincere appreciation for the reviewers' comments and suggestions in sharpening arguments and clarity.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST AND FUNDING DECLARATION

The authors declare that there were no conflict of interest in carrying out this study. Students received a budget of RI000 from the Department of Occupational Therapy at the UFS for traveling to the interviews, and communication costs. Remaining (minimal) costs were absorbed by the researchers.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The principal author, Tania Rauch van der Merwe, conceptualised the study, provided input and supervision throughout the research process, and co-wrote the article, including submission of the article. Jean-Mari Niemann, Melicia Muller, Armunay Gillmer, Roxanne Bruschow, Lindi Basson and Tihani Crouse were all involved in the research process and with writing the article.

REFERENCES

1. Wilcock AAA. Occupation for Health, Volume 1, A Journey from Self-Health to Prescription. London, UK: British College of Occupational Therapists; 2001. [ Links ]

2. Cilliers P Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding Complex Systems. London: Routledge; 1998. [ Links ]

3. Yerxa EJ. 1966 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. Authentic occupational therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1966; 21(1): 1-9. [ Links ]

4. Grootenboer P, Hardy I. Contextualizing, orchestrating and learning for leading: The praxis and particularity of educational leadership practices. SAGE Publications. 2015; 45(3): 402-418. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1741143215595418 [ Links ]

5. Bauman Z. Culture as praxis. London: SAGE Publications; 1999 [ Links ]

6. Masweneng K. Tembisa gymnast flips his way to Guinness World Records glory. 2021 [accessed 2021 May 12]. https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/lifestyle/2021-05-02-watch-flippin-amazing-zama-mofokeng-breaks-records-with-one-hand/ [ Links ]

7. McCallum K. How Was the COVID-19 Vaccine Developed So Fast? The Houston Methodist on Health. 2020 [accessed 2021 May 14]. https://www.houstonmethodist.org/blog/articles/2020/dec/how-was-the-covid-19-vaccine-developed-so-fast/ [ Links ]

8. Goverment Communication and Information System - Health. 2016/17 South Afirca Yearbook. 2017 [accessed 2021 May 14]. https://www.gcis.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/resourcecentre/year-book/Health2017.pdf [ Links ]

9. Alligood M, Fawcett J. Rogers' Science of Unitary Human Beings and Praxis: An Ontological Review. Practice Colum. 2012; 19(1): 65-74. [ Links ]

10. Glassman M, Patton R. Capability Through Participatory Democracy: Sen, Freire and Dowey. Educational Philosophy and Theory. 2014; 46(12): 1353-1365. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.828582 [ Links ]

11. Seo M, Creed WED. Institutional Contradictions, Praxis, and Institutional change: A dialectical perspective. The Academy of Management Review. 2002; 27(2): 222-247. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134353 [ Links ]

12. Morrow G. Praxis. In: The Dictionary of Philosophy. DD Runes, Editor. Littlefield: Paterson, NJ; 1979; 248. [ Links ]

13. Oxford Reference. Praxis. 2021 [accessed 2021 September 15]. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100342205 [ Links ]

14. Peters L, Galvaan R. Occupation-based Community Development: A Critical Approach to Occupational Therapy. In: Concepts in Occupational Therapy, Understanding Southern Perspectives. SA Dsouza, R Galvaan, EL Ramugondo, Editors. Manipal, India: Manipal University Press; 2017:32-48. [ Links ]

15. Krenzer, MLM. A case study exploring the application of the Occupation-based Community Development Framework: Co-constructing humanising praxis. R Galvaan, Supervisor. Minor Dissertation, Cape Town, UCT; 2019. [ Links ]

16. Freire P Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Penguin Books; 1970. [ Links ]

17. Soomar N, Mthembu T, Ramugondo E. Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa (OTASA) Position Statement: Spirituality in occupational therapy. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 47(3):172-187. [ Links ]

18. Basson L, Buschow R Crous T, Gillmer A, Muller M, Niemann J. Human praxis as possible innovation for occupational therapy practice: An interpretivist description from people who enact praxis. T Rauch van der Merwe, Supervisor. Undergraduate Research Protocol, Bloemfontein, UFS, 2018. [ Links ]

19. May-Benson TA, Cermak, CA. Development of an Assessment for Ideational Praxis. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007; 62(2): 148. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.6L2.148 [ Links ]

20. Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability Foundation. Introduction to the VdTMoCA. 2018. https://www.vdtmocaf-uk.com/introduction-to-the-vdtmoca [ Links ]

21. Ataguba JE. Health financing and NHI in South Africa. 2018. [accessed 15 February 2018]. http://www.hst.org.za/hstconference/hstconference2016/Presentations/presentation_04-05-2016.pdf#search=medical%20health%20insurance%20coverage [ Links ]

22. Health Professions Council of South Africa Annual Report. 2019/2020. [accessed 17 September 2021]. https://www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/Publications%202019/Annual%20Report/HPCSA%20_ANNUAL_REPORT_20192020.pdf [ Links ]

23. Worldometers. South Africa Population. 2020. [accessed 17 September 2020]. http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/south-africa-population/ [ Links ]

24. World Health Organization. World Health Organization Assesses the World's Health Systems. 2000. [accessed 18 March 2018]. http://www.who.int/whr/2000/media_centre/press_release/en/ [ Links ]

25. Coulter A, Parsons S, Askham J. World Health Organisation, on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems. 2008. [accessed 24 January 2018]. http://www.who.int/management/general/decisionmaking/WhereArePatientsinDecisionMaking.pdf [ Links ]

26. Laliberte Rudman D. Risk, Retirement, and the 'Duty to Age Well': Shaping Productive Aging Citizens in Canadian Newsprint Media. In Polzer J, Power E, editors "Neoliberal Governance and Health". Montreal: McGill-Queen's University; 2016:108-131. [ Links ]

27. Botma Y Greeff M, Mulaucfzi FM, Wright SCD. Research in Health Sciences. Cape Town: Pearson; 2010. [ Links ]

28. Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough?. Qualitative Health Research. 2017; 27(4): 608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344 [ Links ]

29. Adams R, Adeleke F, Anderson D, Bawa A, Branson N, Christoffels A et al. Corrigendum: POPIA Code of Conduct for Research. South African Journal of Science. 2021;117(5/6):1-12. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2021/10933 [ Links ]

30. Master of Business Administration School. Marketing and strategy. 2008. [accessed 15 February 2018]. https://www.mbaskool.com/business-concepts/marketing-and-strategy-terms/7166-initiator.html [ Links ]

31. Quigley JV. Vision: How Leaders develop it, share it, and sustain it. Business Horizons. 1994; 37(5): 37-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(94)90017-5 [ Links ]

32. Masuda AD, Kane TD, Shoptaugh CF, Minor KA,. The Role of a Vivid and Challenging Vision in Goal Hierarchies. Journal of Psychology. 2010; 144(3): 221-242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223980903472235 [ Links ]

33. Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. 4. Baltimore MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [ Links ]

34. MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, Kegeles S, Strauss RP Scotti R, Blanchard L, Trotter RT. What is Community? An Evidence-Based Definition for Participatory Public Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001; 91(12): 1929-1938. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1929 [ Links ]

35. Lexico. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Experience. 2018. [accessed 16 June 2018]. https://www.lexico.com/definition/readiness [ Links ]

36. Lexico. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Knowledge. 2018. [accessed 19 June 2018]. https://www.lexico.com/definition/knowledge [ Links ]

37. Lexico. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Skill. 2018. [Online]. [accessed 19 June 2018]. https://www.lexico.com/definition/skill [ Links ]

38. Brownson CA. Funding community practice: Stage I. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998; 52(1): 60-64. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.52.L60 [ Links ]

39. Smith MK. Paulo Freire and informal education. In: The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. 1997, 2002. [accessed 27 Junly 2018]. http://infed.org/mobi/paulo-freire-dialogue-praxis-and-education/ [ Links ]

40. Lavery SH, Smith ML, Esparza AA, Hrushow A, Moore M, Reed DF. The Community Action Model: A Community-Driven Model Designed to Address Disparities in Health. American Journal of Public Health, 2005; 95(4): 611-616. https://dx.doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2004.047704 [ Links ]

41. Lexico: Condition. 2018 [accessed 2018 July 16]. https://www.lexico.com/definition/condition [ Links ]

42. Lexico: Constraint. 2018 [accessed 2018 July 16]. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/constraint [ Links ]

43. Tech Target Contributor: Constraint (Project constraint). 2018 [accessed 2018 July 16]. https://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/constraint-project-constraint [ Links ]

44. Culatta R: Structural Learning Theory (Joseph Scandura). 2018 [accessed 2018 July 16]. http://www.instructionaldesign.org/theories/structural-learning [ Links ]

45. D'Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM, Maydeu-Olivares A. Chapter 1, Social problem solving: Theory and Assessment. In: Social Problem Solving: Theory, Research, and Training. EC Chang, TJ D'Zurilla, LJ Sanna, Editors. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2004: 11-27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/10805-001 [ Links ]

46. Lexico: Readiness. 2018 [accessed 2018 July 16] https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/readiness [ Links ]

47. English Oxford Living Dictionaries: Opportunity. 2018 [accessed 2018 July 16] https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/opportunity [ Links ]

48. Collins Dictionary: Opportunity. 2018 [accessed 2018 July 26]. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/opportunity [ Links ]

49. van den Hoof B, de Ridder JA. Knowledge sharing in context: the influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and CMC use on knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2004; 8(6): 117-130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270410567675 [ Links ]

50. Paulin D, Suneson K. Knowledge Transfer, Knowledge Sharing and Knowledge Barriers - Three Blurry Terms in KM. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 2012; X(1): 81-91. [ Links ]

51. Savolainen R. Information sharing and knowledge sharing as communicative activities. Information Research, 2017; XX11(3). [ Links ]

52. Chen SX. Harmony. In Lopez SJ, editor. "The Encyclopedia of Positive Psychology," Londen: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2009: 464-467. [ Links ]

53. Lexico: Interact. 2018 [accessed 2018 June 15]. https://www.lexico.com/definition/interact [ Links ]

54. Kasim RM. Interaction Effect. In: Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. PJ Lavrakas, Editor. California: SAGE Publication; 2008: 339-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412963947.n226 [ Links ]

55. Carnwell R Carson A: McGraw-Hill Education. 2018 [accessed 2018 June 19]. https://www.mheducation.co.uk/openup/chapters/0335214371.pdf. [ Links ]

56. UpCounsel: Types of Business Partnerships: Everything YOu Need to know. 2018 [accessed 2018 July 19]. https://www.upcounsel.com/types-of-business-partnerships [ Links ]

57. Misiorek A, Janus E. Spirituality in Occupational Therapy Practice According to New Graduates. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2018; 39(4):197-203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449218808278 [ Links ]

58. Puchalski CM, Vitillo R Hull SK, Reller N. Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: Reaching National and International Consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2014; 17(6): 642-656. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.9427 [ Links ]

59. Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-being and Justice through Occupation. Ottowa, Canada: CAOT Publications, 2007. [ Links ]

60. American Psychological Association. Building your resilience. 2020. [Accessed 9 June 2018]. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx [ Links ]

61. Psychology today. Resilience. [Accessed 9 June 2018]. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/resilience [ Links ]

62. Southwick SM, George A, Bonanno ASMAS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2014; 5: 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338 [ Links ]

63. Maturana HR, Valera FJ. The Tree of Knowledge, the Biological Roots of Human Understanding. Revised edition. Boston: Shambhala Publications Inc; 1987. [ Links ]

64. Huth C, Kelly B, Sell S. Interdependence: A Concept Analysis. International Journal of Nursing & Clinical Practices. 2017; 4(1): 255. https://doi.org/10.15344/2394-4978/2017/225 [ Links ]

64. Miller WR, Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. New York: The Gillford Press; 2013. [ Links ]

65. Aristotle. The Nicomachean ethics. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [ Links ]

66. Ofori MD. Grounding Twenty-first-Century Public Relations Praxis in Aristotelian Ethos. Journal of Publics Relations Research. 2019; 31(1-2): 50-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2019.1634074 [ Links ]

67. Wiig KM. Knowledge Management Foundations- Thinking about Thinking- How People and Organizations Create, Represent, and Use Knowledge. Arlington, Texas: Schema Press, Ltd; 1993. [ Links ]

68. Jagosh J, Bush L, Salsberg J, Macaulay AC, Greenhalgh T Wong G. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health. 2015; 15(725): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1 [ Links ]

69. Hawe P Shiell A Riley T. Theorising Interventions as Events in Systems. Journal of Community Pshycology. 2009; 43(3-4): 267-276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9 [ Links ]

70. Motimele M, Peters L, Dsouza SA, Galvaan R Ramugondo EL. Understanding human occupation. In: Concepts in Occupational Therapy, Understanding Southern Perspectives. Editor. Manipal: Manipal University Press; 2017:1-15. [ Links ]

71. Ramugondo EL, Kronenberg F Explaining Collective Occupations from a Human Relations Perspective: Bridging the Individual-Collective Dichotomy. Journal of Occupational Science. 2015; 21(1): 3-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.781920 [ Links ]

72. Bratman ME. Shared Agency, A Planning Theory of Acting Together. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [ Links ]

73. Walder K, Molineux M, Bisset M, Whiteforld G. Occupational adaptation - analysing the maturity and understanding of the concept through concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 201 9; 28(1): 26-40. [ Links ]

74. Argyris C. Teaching smart people to learn. Harvard Business Review. 1991; 4(2): 4-15. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1072.5181&rep=repl&type=pdf [ Links ]

75. Guillem SM. The edges of praxis: embracing constraints in (whiteness) theorizing. Journal of Multicultural Discourses. 2016; 11(3): 262-268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2016.1221410 [ Links ]

76. Dsouza SA, Galvaan R Ramugondo EL. Human Occupation and Health. In: Concepts in Occupational Therapy, Understanding Southern Perspectives. Manipal: Manipal University Press; 2017:32-48. [ Links ]

77. Doble SE, Santha J. Occupational wellbeing: Rethinking occupational therapy outcomes. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 75(3) 184-190. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F000841740807500310 [ Links ]

* Tania Rauch van der Merwe. Email: tania.vandermerwe@wits.ac.za

APPENDIX A:

Eligibility criteria

a) Participants need to be over the age of l8 as they can then consent to participating in this research project. Specifics such as gender, sex, race, and socio-economic levels are irrelevant.

b) Participants need to be proficient in English and/ or Afrikaans by virtue of the student's language capacity and for the feasibility of the study especially in view of making use of the methodology as stated below.

c) Participants will be identified by means of purposive sampling and consulting an expert in the research setting to assist in identifying individuals who demonstrate the following characteristics (with regards to the operational definition of praxis)

i) reflexive awareness (including self-awareness about constraints they face and/or have to overcome as well potential possibilities),

ii) internal locus of control ( in other words are self-driven)

iii) openness to learn from one and others' mistakes

iv) action toward change - not only for that person but also to effect change in the community of which that person/s are part of.

d) Participants are chosen based on a general awareness within the occupational therapy community, of the fact that they see themselves as change agents as well as that they enacted that in the environment in which they work and live. This general awareness can be known by means of word of mouth or general knowledge.

e) Participants will not be eligible if they are not available to partake in an interview within the time allocated toward data collection.