Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.51 n.2 Pretoria Aug. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2021/vol51n2a12

ARTICLES

The meaning that undergraduate Occupational Therapy students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal attach to the Occupation of dance

Thanalutchmy LingahI, *; Juwairiyya ParukII

IB.OT (UKZN); MBA (Wales). https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9183-4072; Lecturer, Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIB.OT (UKZN). https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1973-6785; Lecturer, Occupational Therapy Department, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Occupational Engagement is an inextricable component of life and is considered essential to human survival. Doing an occupation that is positively perceived (such as dance) can lead to the experience and expression of meaning which then enhances quality of life. This study aimed to explore the meaning that undergraduate Occupational Therapy students studying at the University of KwaZulu-Natal attach to dance as an occupation

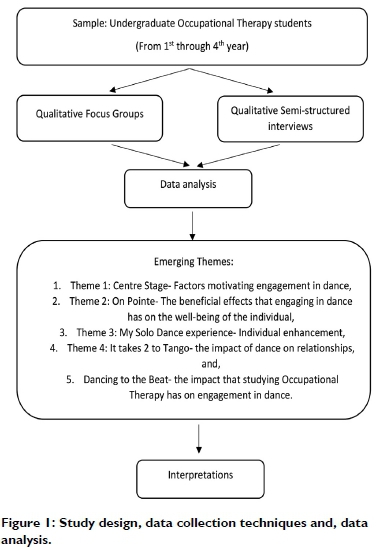

METHOD: The study followed an exploratory qualitative research design with purposive sampling. Focus groups and semi-structured interviews were utilized to collect data which were analysed thematically

RESULTS: Five themes emerged: Centre stage (an exploration of factors motivating engagement); On Pointe (beneficial effects of dance); My Solo Dance Experience (the individual's journey whilst engaging); It Takes 2 to Tango (exploring the role of relationships) & Dancing to the Beat (exploring time available for engagement). The hidden complexities of 'meanings' attached to the occupation of dance emerged which were experienced as subjective and multi-dimensional

CONCLUSION: The study revealed that the meanings attached to dance were based on individual experiences with the occupation, others and the environment. Engagement in the occupation of dance (doing) enhances personal growth (becoming) and becomes a part of the individual (being

Keywords: doing; being; becoming; belonging; occupational engagement; occupational balance; occupation; dance; meaning

INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Among the amplitude of survival requirements lies a dynamic construct: Occupational Engagement. Engaging with the environment through participation in occupation is a collective human need, essential to survival1. Humans participate in occupations to meet certain physical, psychological, and social needs. Occupations allow for humans to realise their aspirations and experience a sense of well-being. The inherent properties of an occupation allow for the experience of satisfaction and can thus improve quality of life2,3. For the purpose of this study, occupations will be explored as a complex concept which refers to a synthesis of doing, being, becoming and belonging4.

Doing refers to purposeful and goal-directed task engagement; humans engage in doing to complete tasks of necessity (as perceived by the individual), as well as tasks deemed as enjoyable4,5. Doing an occupation holds both positive and negative aspects, and these will be stimulated according to the task being undertaken. Being refers to existing and living4. It is a stillness allowing one to exist within the moment, whilst everything else ceases to be5,6. The state of being enables reflection, as it is nothing but thought itself 7. Becoming refers to potential and growth, transformation and self-actualization4. Becoming allows an individual to envision possibility, within themselves and their lives5. Belonging describes a sense of connectedness that arises from participating in occupations. Occupations allow individuals to form connections with others, and this positively impacts upon socialization3.

Meaning and occupation are fundamentally interrelated as meaning is the driving force behind occupational engagement, and occupations are performed due to the meaning/s linked to them3.

Meaning is defined as the intent, significance, and importance that something has for an individual3:196. Occupations have impacts attached to them and are a central source of life's meaning5. The meaning an individual attaches to an occupation are unique to them, meaning is therefore subjective and cannot be objectively defined. However, "the same individual may define an occupation differently at different times, dependent upon mood, goals, context and the presence of other people"5297. Furthermore, a single occupation can hold multiple meanings for the individual engaging. "The meanings occupations hold are understood to motivate individuals' performance of specific occupations"3:297.

Dance as an occupation is seen as transformative, having the power to transport an individual, and envelop one in a meaningful experience that lies outside the realms of daily stress. An individual's physical being enables the enactment of creative expression through the occupation of dance. This expression then enables the individual to freely convey their thoughts, ideas and feelings through the artistic endeavour6. The meanings attached to the occupation of dance enable the formulation of connections with oneself, those around oneself, as well as the wider world7. Creative activities provoke the senses, give pleasure, and seem to help one connect to higher phenomenon. Dance as a psychotherapeutic agent has been found to contribute the improvement in one's mood, body image and self-esteem8. Seeing as dance requires the use of the body in its entirety, it has numerous physical benefits as well9. Thus, dance as an occupation may have multiple benefits including physical, psychological, social, therapeutic, cultural and recreational3,4.

Student populations spend a significant amount of time engaging in the occupation of studying5. Balance in all areas of occupation is fundamental to ensure well-being. When an individual is restricted from engaging in the occupations that are significant and meaningful to them, this then leads to occupational imbalance, which in turn negatively affects wellbeing. A healthy occupational balance is portrayed when an individual can engage in their occupations of choice, without a sense of deprivation (due to limited time available for occupational engagement)10. There is limited time available for undergraduate students to engage in other occupations (aside from the occupation of studying), and this may have a negative impact on their quality of life11,12,13.

It is therefore important to focus on other occupational performance areas that the student population engage in (such as leisure) and identify the meaning attached to such occupations. The student population face an innumerable number of stressors daily. Occupational therapy students in particular, are vulnerable to multiple academic and university related stressors14, and these can be potentially minimized through participating in other meaningful occupations- such as the occupation of dance.

The purpose of this study was therefore to explore the various meaning/s attached to dance as an occupation by undergraduate occupational therapy students, to explore whether engagement in the occupation of dance has an impact on well-being. Furthermore, the study aimed to explore the impact that the occupation of studying has on undergraduate occupational therapy students' engagement in the occupation of dance.

It is essential to understand the occupations that a person chooses to engage in, as this allows occupational therapists to better understand their clients, their needs and thereby determine the focus of intervention whilst working with the client in order to maximize their quality of life. Understanding human engagement in occupation, and why people do the things that they do, forms the basis of occupational therapy2,15.

METHOD

Study Design

A qualitative, exploratory design was selected to conduct the study. Meanings attached to occupations are subjective, and an interpretative design thus enabled the exploration of the phenomena of interest16. Qualitative research enables the formation of a holistic picture and accurately allows for the detailed views of participants to be reflected17.

Population and Sampling

Participants were recruited using maximum variation purposive sampling. In purposive sampling "the researcher decides what needs to be known and sets out to find people who can and are willing to provide the information by virtue of knowledge or experience" 18:147. Thus, participants were recruited based on a predetermined set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Maximum variation sampling was utilised to ensure a heterogeneous sample. The study sample consisted of twelve participants in total (Table l, p93).

Inclusion Criterion

Participants were all undergraduate students studying occupational therapy and were selected if they were currently or previously engaged in the occupation of dance.

Data collection procedures and management

A combination of focus groups, and semi-structured interviews were utilized for data collection. These were recorded using two audio-recording devices, and later transcribed verbatim. The audio recordings had been saved onto an external hard drive and locked in a safe19. The focus groups and semi-structured interviews had been conducted in a lecture theatre where privacy had been ensured. Questions utilized for the focus groups and semi-structured interviews were guided by the research aim. Two focus groups (made up of 6 participants each) and six semi-structured interviews were conducted. For the purpose of this study, the combination of methods had been used for data completeness. Through the use of Triangulation, the limitations of one method were counteracted by the strengths of the other17,20.

Data Analysis

The data collected were inductively analysed using the six phases of thematic analysis as indicated by Clarke and Braun20. When conducting qualitative research, a large amount of data is usually generated. Thematic analysis allowed for data reduction and simplification17. Inductive analysis allowed for the researchers to move from specifics gathered in data generation to a more general set of propositions.

Trustworthiness

Throughout the study, trustworthiness was ensured by adhering to the principles of credibility, dependability and confirmability and transferability. Credibility was achieved by consulting appropriate literature, as this enabled the researchers to become immersed in understanding the occupation of dance. A pilot study was done by the researchers to determine if the proposed research questions were eliciting responses relevant to the research question21. Questions were posed in a focus group consisting of 4 undergraduate health science students from various disciplines. The results of the pilot work displayed ambiguity in some of the proposed questions, questions were thus refined and altered for the main study. Credibility and dependability are closely related as demonstrating credibility will later ensure dependability22. To ensure credibility and dependability the researchers reported in detail the process utilized. Furthermore, the researchers had taken steps to reduce bias by performing data coding separately, to ensure that the ideas were reflective of the data generated and not influenced by the researcher20, hence ensuring conformability22,23.

*Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations pertaining to informed consent, right to privacy and confidentiality, non-maleficence and beneficence were adhered to. The research proposal had been submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), and ethical clearance had been granted. Approved by Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSSREC) at UKZN (Ref: HSS/0387/017U). Following this, a permission letter had been submitted to the registrar of Health Sciences, to begin the process of data gathering. Informed consent was obtained by providing participants with a detailed explanation of the study and intended use of information obtained from the study. Participants were provided with the opportunity to terminate participation at any point during the study without facing any repercussions. Pseudonyms are used throughout the report to ensure participant anonymity.

Bias Declaration

No funding or affiliations were associated with this study.

RESULTS

Data collected from focus groups and semi-structured interviews were analysed and coded separately and then co-clustered into subthemes. Analysis then merged at the point where themes were determined and, relevant subthemes grouped together to form the study's five main themes - Centre Stage, On Pointe, My Solo Dance Experience, It takes two to Tango and Dancing to the Beat.

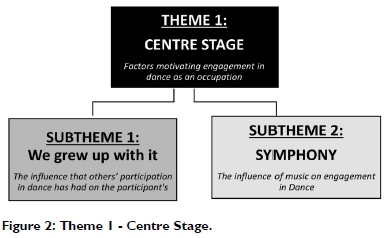

Theme 1: Centre Stage

The theme of Centre Stage focuses on the various motivating factors, existing external to the individual, and encouraging participants' performance in the occupation of dance.

Sub-Theme 1 - We grew up with it: Factors motivating participation in dance included opportunities offered by the university which entailed dance clubs catering for a variety of genres, it was identified that, through observing other students dancing, participants' motivation to engage in dance increased.

"When I saw other people dancing, I decided to join them and got motivated because I also wanted to learn those dance moves"-John*

Early exposure to dance, motivated and influenced the individuals' participation in the occupation.

"My twin sister and I started dancing at a young age, around five or six, due to the influence of my older sister"- Sonam*

Sub-Theme 2 - Symphony: It emerged that the music arouses feelings and emotions encouraging spontaneous dance. Music harmoniously speaks to as it influences and supports rhythm.

"The music, Igqomu, calls your name. If you feel the music, you are going to dance. Automatically your body will respond to it, you will just go Vosho. It's like an automatic reaction."-Gugu*

Theme 2 : On Pointe

The theme On Pointe refers to the beneficial effects that engaging in dance had on the well-being of the participants.

Sub-Theme 1 - Physical enhancement: Participants mentioned weight loss and subsequent improvements in physique. It was also indicated that dance serves to increase endurance, enables the building of muscle strength and improvement of flexibility.

"I feel a lot stronger and have become a lot more flexible."-Michaela*

Sub-Theme 2 - Emotional enhancement: Participants reported that when engaged in dance a sense of happiness is evoked. This sense of happiness can be internal but can also be shared with the external world.

"I can't not smile when I'm on stage. I can't keep a straight face, so I look and feel like I'm having the time of my life."- Michaela*

In both focus groups and semi-structured interviews, it emerged that dance is a means of 'letting go', an escape mechanism enabling the expression of tension via an alternate means.

"When I'm dancing, I don't think about anything else."-Jean*

Participants mentioned that their confidence increased when provided with positive gratification and feedback from others. Professional dancing participants have mentioned that the manner in which they dress and carry themselves in both the dance world and external to it has improved, which serves as a confidence booster.

Participants responsible for choreographing and teaching dances to fellow dancers indicated that sharing their own creativity was inspirational and watching their creativity come to life was awe inducing.

"I love working with other people, especially young kids as I am able to share my knowledge, skills and passion with them."- Kiki*

Positive and negative emotions can be portrayed through dance. Emotions are expressed through bodily movements and facial expressions.

"Life is filled with hidden complexities and deep emotions. When I dance, I am able to project these feelings and express myself in a more constructive way."- Winnie*

Theme 3 : My Solo Dance

The role of the occupation of dance in individual enhancement emerged. The theme My solo dance experience explores the individual's journey whilst engaging in the occupation of dance, and in essence reveals a layer of meaning to the individual.

Sub-Theme 1 - Passion: A common idea held by participants, was that dance is viewed as a deeply rooted passion, an element encompassing the being and world of the individual engaging.

"Dance means the world to me, without it I don't think I'd be able to function normally."- Jean*

The passion for engagement is further stimulated by the feelings and emotions fuelled by engagement. The passion for engagement and associated freedom arises from voluntary engagement.

Sub-Theme 2 - Personal growth: Personal growth refers to self-competition, which enables internal and external growth to feed off of each other, as confidence leads to an improvement in one's performance and vice versa.

Within the sub-theme of personal growth working toward a personal goal was revealed on numerous occasions. Goals were inclusive of moving up to a higher level or grade within their specific genre, in order to achieve this the participants revealed that they had to work on their technique.

Sub-Theme 3 - My everything: Most participants engaging in dance professionally and socially view dance as a non-extractable component of life itself. Dance has been woven into the material of their very being and core.

"... to me it means everything."- Winnie*

Dance cannot be separated from life as merely an occupation that one engages in. Dance is viewed as a person or being because of the sense of connectedness that participants feel toward the occupation.

"Dance is my best friend; I communicate with it and through it."- John*

Theme 4 : It takes 2 to tango

The theme It takes 2 to Tango relates to the relationships emphasized by participants. Dance plays a role in the formation of relationships - either positive or negative, as dance is often conducted with, or amongst, others. Connections range from superficial to deep, depending on the type of dance and the individual/s engaging in.

Sub-Theme 1 - Make dance: Dance has the capacity to draw people together based on mutual love or passion for the occupation. Dance allows for networking with others who engage in the same occupation on a professional level. Dance also builds a community within the studio that that the person attends.

"... it has allowed me to establish a new extended family."- Jean*

According to participants who engage in Latin dance, dance can serve as a means to build an emotional and intimate connection with one's dance partner. Dance is a soulful language, expressing the contents of one's soul in the presence of another can lead to intimacy as barriers are broken down.

Together with building new relationships, dance has the ability to enhance relationships within the person's life, both within and external to the context of dance. Relationships discussed are representative of those between people as well as those between a person and a higher being.

"In Bharathanatyam there is often a dance that is performed for the different deities in the Hindu culture and when I am performing each of these dances, I feel spiritually connected with that specific God. or Goddess." - Sonam*

Dance solidifies relationships, as one may share the occupation with a family member or friend- allowing for mutual engagement and practice. Participants who have an intimate partner have mentioned that dance has strengthened their relationship, as their partner grew a deeper attraction and appreciation for them when watching their passion come to life.

Sub-Theme 2 - Break dance: Dance can lead to competitiveness, which can often border on being unhealthy, as this occurs amongst friends or family members and then leads to a strain on these relationships. Competitiveness also often leads to dancers critiquing the appearance, ability and technique of other dancers.

Jealousy can often result as comparisons do occur, this can further impact upon relationships.

"My sister is a brilliant dancer. As much as I do love dancing with her, it is sometimes really difficult watching her being in the front row, whilst I am in the back row."- Jean*

This can lead to feelings of inferiority and self-doubt and can result in viewing the occupation of dance in a more negative light.

Theme 5 : Dancing to the Beat

The theme Dancing to the Beat focuses on the impact that studying Occupational Therapy as an undergraduate student has on the engagement of dance as an occupation as well as the manner in which engagement had altered over time.

Sub-Theme 1 - Time: A common consensus by participants was that limited time is available to engage in dance owing to the occupation of studying consuming the majority of the participant's time. It became evident that being a student limits the time available to engage in dance on a professional level. The participants expressed enjoying going out to bars, clubs and formal events and engaging in the occupation of dance. The times used to engage in social dance do not coincide with university hours and therefore, participation is not limited.

As with most occupations the less time spent practicing the skills involved in the occupation as well as less time engaging in the occupation will ultimately affect one's performance and skill. This serves as a limitation to their participation.

"Since studying OT, I am hardly able to attend dance classes and I feel like my endurance is not as good, and my fitness is not as great. That has dampened my self-esteem not being as fit and lean as the other dancers."- Michaela*

DISCUSSION

Based on the five themes that emerged from the study, the subsequent discussion explores the main ideas emerging through an integration of the findings with the literature sourced.

Invoking the senses in order to 'do':

The study revealed that observation or association with others participating in the occupation is a significant factor motivating 'doing'.

Although dance can be performed in the absence of music, dance and music exist in symphony with each other. "Music is universal. Listening to music can soothe the soul and excite the emotions"24:284. Through the emotions that have been elicited, participants expressed that they had experienced a loss of inhibition, allowing them to engage in dance.

Although this view was held amongst many participants, limited research has explored the effects of external influencers in the engagement in occupation. It is therefore evident through the findings obtained, that external influences (inclusive of viewing the engagement of others, and music) promote engagement in dance as an occupation.

'Doing' leading to 'becoming':

The occupation of dance is most often associated with the physical benefits that it possesses. However, these were far outweighed by the psychological benefits that had emerged.

Findings revealed that participants experienced physical enhancement owing to 'doing' the occupation of dance. The occupation of dance has its own impact on the individual, as dance is a creative art form, and the movements required when dancing draw upon both the individual's mind and body. Many participants reported an improved physique which further assisted in improving emotional well-being, as their body image and self-confidence had improved.

Occupations are valued for the experience they provide, and the feelings they stimulate5. This was reflected in the findings of the study, which indicated that engaging in the occupation of dance aroused positive feelings and emotions in a number of the participants. Human beings instinctively seem to utilize creative occupations like that of dance to relieve certain emotional symptoms experienced1. Participants use the occupation of dance to externalize negative feelings, which provides an outlet for participants to express themselves in a more constructive way. A participant revealed that the occupation of dance is used as a means of releasing inner tension and frustration, without dance-she felt as though a channel for such expression would not be possible (Sonam*).

The study had revealed that feelings of happiness and elevated mood can also be shared with others engaging in the occupation. Dance serves as a platform for sharing joy and positive emotions. This in essence leads to the belief that occupational engagement can lead to the transference of emotions amongst persons engaging, and amongst those viewing engagement.

Recognition received from family, friends and strangers, serves as positive appraisal, and provides an opportunity for socialization whereby individuals can practice and utilize social behaviors to formulate social interactions. According to literature, socialization assists in alleviating stress and the incidence of depression6.

Growth and self-enhancement through engaging in the occupation of dance

A positive sense of consciousness is said to be experienced when an individual's skills are used to meet the challenges of an environ-mentl. Purposeful engagement in dance to achieve goals set out, was a common reason for engagement. Goals as a reason for engagement within the occupation is supported by literature, which indicates that occupations are viewed as having a goal or purpose for the person engagingl3.

Thus, participants' views of engaging as a means to enhance personal growth - which encompasses internal growth (building upon confidence and self-esteem) as well as external growth (which looks at technique improvement, and the improvement of bodily functions) - is in keeping with literature2,13,25,26.

Engaging in the occupation of dance, which is ultimately 'doing', enables the participants to experience growth and transformation through the process of self-actualization, hence enabling the process of 'becoming'. According to literature, occupations are purposefully chosen by individuals as a channel to shape, build upon and express their identity25,26. According to a participant, "If I don't dance for like a week, I just don't feel like myself." - John*. This view is consistent with literature as it speaks to an occupation contributing toward the identity of the participant. Furthermore, a lack of engagement in meaningful occupations can deconstruct one's identity, thereby negatively impacting well-being25.

Meaning as a subjective experience within the occupation of dance (Being):

A common consensus amongst existential theorists, is that 'meaning' is an essential property of occupational engagement7,25,27,28,29 A powerful stimulant for occupational engagement is the meaning that the occupation holds for the individual engaging. Participants had stated that if enjoyment were not derived from occupational engagement, their participation within the occupation would have ceased.

A participant had mentioned that "dance means freedom." -Sam*. The feeling of freedom arises from engaging in the occupation of dance out of one's own free will. Such engagement imbues greater value to the occupation. This is supported by literature, as engagement in meaningful occupations can occur despite the lack of external rewardsl.

Flow is a construct separate from occupational science literature, however, its contribution within occupational engagement is indisputable, and formulates a dimension of meaning. According to several participants, dance is a part of who people are. This was consistent with findings from literature, which suggests that people who have experienced occupational flow report a feeling of being at one with the movements they are making1:67. These views are in essence the embodiment of the concept of being outlined by multiple occupational science theorists, being refers to existing within the occupation itself, and not beyond it5,30

A unique concept that had emerged from the participants' perspective, was that dance is viewed by multiple participants as more than purely an occupation. Dance had been spoken of as a person with whom the participants connect. There is little known research to support this view. However, formulating a bond with an occupation that is viewed as meaningful is not unfathomable, as the occupation may elude its constraints and become to the engager anything, they perceive it to be.

The shared experience of occupational engagement (shared meaning and the process of belonging):

The role of occupations in enabling the formation of relationships has been theorised by a multitude of occupational scientists over time2,4. Occupations enable a sense of connectedness- in essence, a sense of sharing an element of oneself5. Thus, participants viewing engagement in dance as a means to formulate relationships is not a novel concept. According to a participant "It [dance] also brings people together." - Amanda*. This view indicates that occupational engagement can foster connections amongst persons with a common interest in the occupation, as the feelings stimulated by engagement may be shared, and the joint experience may enhance these feelings. Several participants had indicated that dance with others has led to the formation of a sense of community.

Support received when engaging in dance serves to solidify bonds between the engager and members of their family, as they feel a sense of wholeness through the provision of support. Furthermore, dancing with a friend/partner or family member can intensify the bond through a shared positive experience. This is in keeping with literature which states that occupations play a role in enhancing relationships5.

A view that has not been extensively explored in literature is building of intimate connections through engagement in the occupation of dance. Participants had indicated that shared engagement in the occupation together with a partner leads to the development of a bond so profound, that it may lead to the stimulation of deep feelings and emotional connections with the partner. This was the case specifically in forms of dance requiring extensive eye-contact, and physical touch, notably Latin dance, as participants are required to be in sync with one another's steps which requires a certain level of trust.

Occupational engagement can further lead to the formation of connections beyond the tangible. Feelings of spiritual connections are elicited through complex perceptions and emotions elicited by occupational engagement. The views of participants regarding the formation of spiritual connectedness that emerged from engagement in the occupation of dance is supported by literature, as creative occupations (like that of dance) enable connections to higher phenomenon1.

Although occupations are said to have a role in the development and maintenance of positive relationships - a role less common but irrefutable - is the formation of negative relationships through occupational engagement. According to literature, occupational engagement is widely understood as a platform enabling the development of relationships- either positive or negative13. Although less common, a few participants pointed out that engagement in dance can lead to negative relationships.

The role of time in occupational engagement:

"Occupational therapy, since its inception, has a core interest in time use as an indicator of health and well-being"1:60. Limitations for engagement occur because of insufficient time available, owing to the occupation of studying.

Time reveals itself as a vacuum, inviting us to fill it with meaningful doing1. A healthy occupational balance is represented by a healthy working adult engaging in equal amounts of leisure related, self-care and productive activities, disproportionate engagement in certain daily occupations often has an impact on the well-being of the individual. Occupational imbalance occurs when one occupation monopolizes a person's time so that there is decreased participation in other occupations13. Participants who engaged in dance on a more professional level have found that they have been deprived of this balance because they cannot participate in dance as often as they had previously.

Humans have a creative nature and to withhold or block that inherited ability is a denial of our true essence7. Participants had revealed that limited time available to engage in the occupation of dance has affected their technique. Although the time available to engage in professional dance is limited, participants indicated that they are able to engage in social dance as times do not coincide with those of lectures. This suggests that participant have sought a manner in which to achieve balance between their various occupational performance areas.

Implications:

Findings indicated that external influences promote occupational engagement within the occupation of dance (as participants had been motivated by the engagement of others in the occupation of dance, as well as music). It is therefore suggested that this concept be further investigated, as external influences may encourage occupational engagement within other occupations.

The study outlined that music plays a significant role in motivating engagement in the occupation of dance. It is therefore suggested that the role of music within the occupation of dance and possibly other occupations (productivity at work) be further explored. Findings have indicated that emotions and feelings may be transferred through the process of occupational engagement within the occupation of dance which is a phenomenon worth exploring for other occupations as well.

LIMITATIONS

As occupational therapy students were previously exposed to the concepts of meaning and occupation (as a part of their curriculum), they may have answered the questions in accordance with what they perceived that the researchers may have wanted from them.

The study sample consistent primarily of females, and hence the study may lack a male perspective on the meaning attached to the occupation of dance.

Both the focus groups and semi-structured interviews had been conducted in English, and certain participants' primary language was that of isiZulu. This may have prevented these participants from revealing certain nuances of meaning due to not being able to fully express themselves in their second language.

CONCLUSION

The meaning attached to the occupation of dance by participants was highly subjective, which is in keeping with literature: "It is impossible to give an individual's occupation any meaning other than the meaning that they, themselves, choose to give it"31:169. This view is consistently held amongst theorists and has been described by several theorists (i.e. viewing meaning as a subjective experience)4,5. The study has also led to the possibility that there may be a process through which meaning is generated and the following could be a formula that warrants further exploration: Doing (an occupation) + Being (immersing oneself within the occupation, a state in which all else ceases to be) + Becoming (growth and self- actualization) + Belonging (the formation of connections with others and the wider world) = Meaning.

Acknowledgements:

The authors of the article would like to acknowledge the contribution and permission of: Thishari Naicker, Nontuthuko Shongwe, Nontuthuko Sibiya, and Ziyanda Mayeza. Thank you for your role in the dissertation (as undergraduate Occupational Therapy students in 20l7), without you, the article would not have been possible.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Thanalutchmy Lingah supervised the project and contributed to writing the article. Juwairiyya Paruk conducted the study together with peers as undergraduate students, and contributed to writing the article.

REFERENCES

1. Molineux M. Occupation for Occupational Therapists. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishers, 2004. [ Links ]

2. Kennedy J, Davis JA. Clarifying the Construct of Occupational Engagement for Occupational Therapy Practice. Occupation, Participation and Health, 2017, 37(2): 98 -108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449216688201 [ Links ]

3. Hocking C. The challenge of occupation: Describing the things people do. Journal of Occupational Science, 2009; 16(3): 140-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686655 [ Links ]

4. Borges da Costa AL, Cox DL. The experience of meaning in circle dance. Journal of Occupational Science, 2016; 23(2): 196-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2016.1162191 [ Links ]

5. Hammell KW. Opportunities for well-being: The right to occupational engagement. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2017; 84 (4-5): 209-222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417417734831 [ Links ]

6. Haboush A, Floyd M, Caron J, LaSota M, Alvarez K. Ballroom dance lessons for geriatric depression: An exploratory study. The Arts In Psychotherapy, 2006; 33(2): 89-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2005.10.001 [ Links ]

7. Coetzee Z. Every dance has its own story- how participation in dance empowered youth living in a rural community to buffer an intergenerational cycle of poverty. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2011; 41: 50-55. [ Links ]

8. Strassel JK, Cherkin DC, Steuten L, Sherman KJ, Vrijhoef, HM. A systematic review of the evidence for the effectiveness of dance therapy. Alternative Therapies in Health And Medicine, 2011; 17(3): 50-59. [ Links ]

9. Alpert P The Health Benefits of Dance. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 2010; 23(2): 155-157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822310384689 [ Links ]

10. Naidoo D. Aligning occupational therapy with primary healthcare: A multi-stakeholder perspective (doctoral thesis). University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, 2017. [ Links ]

11. Bojuwoye O. Stressful experiences of first year students of selected universities in South Africa. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 2002; 15(3): 277-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070210143480 [ Links ]

12. Shertzer B, Stone SC. Fundamentals of Guidance. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1971. [ Links ]

13. Greenberg GJ. A study of stressors in the college student population. Health Education, 1981; 12: 8-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00970050.1981.10616807 [ Links ]

14. Govender P, Mkhabela S, Hlongwane M, Jalim K, Jetha C. Occupational Therapy student's experiences of stress and coping. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2015; 45(3): 34-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45n3/a7 [ Links ]

15. Wilcock AA. Occupation for health. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1998; 61(8): 340-345. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802269806100801 [ Links ]

16. Polgar S, Thomas SA. Introduction to Research in the Health Sciences. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2013. [ Links ]

17. Carpenter C, Suto M. Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists: A practical guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2008. [ Links ]

18. Dolores M, Tongo C. Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection. Ethnobotany Research and Applications,2007; 5: 147-158. [ Links ]

19. McMillan J, Schumacher S. Research in education. Edinburgh, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2014. [ Links ]

20. Creswell JW. Qualitative & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. London: Sage, 2013. [ Links ]

21. Van Teijlingen E, Hundley V The importance of pilot studies. Nursing Standard, 2002; 16(40): 33-36. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns2002.06.16.40.33.c3214 [ Links ]

22. Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 2004; 22: 63-75. [ Links ]

23. Dunn WR, Lyman S, Marx R. Research methodology. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, 2003; 19(8): 870-873. [ Links ]

24. Towell JH. Motivating students through music and literature. The Reading Teacher, 1999; 53(4): 284-287. [ Links ]

25. Watters AM, Pearce C, Backman CL, Suto MJ. Occupational Engagement and Meaning: The Experience of Ikebana Practice, Journal of Occupational Science, 2013; 20(3): 262-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2012.709954 [ Links ]

26. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Enabling occupation. An occupational therapy perspective (Rev. ed.). Ottawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE, 2002. [ Links ]

27. Kelly JR, Kelly JR. Multiple dimensions of meaning in the domains of work, family and leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 1994; 26: 250-274. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1994.11969959 [ Links ]

28. Hasselkus BR. The meaning of everyday occupation. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 2002. [ Links ]

29. Hammell KW. Intrinsicality: Reflections on meanings and mandates. In McColl MA (Ed.), Spirituality and occupational therapy. Ottawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE, 2003. [ Links ]

30. Wilcock AAA. Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1998; 65: 248-256. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174.x [ Links ]

31. Weinblatt N, Avrech-Bar M. Postmodernism and its application to the field of occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2001; 68: 164-170. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740106800305 [ Links ]

* Corresponding Authors: Thanalutchmy Lingah. Email: lingaht@ukzn.ac.za; Juwairiyya Paruk. Email: juwairiyya.paruk@wits.ac.za

* Ethical clearance for this study was granted prior to the enactment of the amended POPIA on 2021-07-01