Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.51 n.2 Pretoria Aug. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2021/vol51n2a6

ARTICLES

Learning styles in Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy students: an exploratory study

Benita OlivierI, *; Lizelle JacobsII; Vaneshveri NaidooIII; Nikolas PautzIV; Rulaine SmithV; Paula Barnard-AshtonVI; Adedayo Tunde AjidahunVII; Hellen MyezwaVIII

IB. Sc; MSc Physiotherapy (Wits); MSc Motion Analysis (Dundee); PhD (Wits). http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9287-8301; Professor, Department of Physiotherapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIB. OT (Pret); MSc OT (Brunel); PhD (Wits). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5373-2155; Lecturer, Occupational Therapy Department, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Therapeutic Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIBSc (Physiotherapy); MSc (Physiotherapy). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4513-8666; Lecturer, Department of Physiotherapy, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVBA Psych (UNISA); MSc (UKZN); PhD (UKZN). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4513-8666; Research Associate, Nottingham Trent University, Department of Psychology, United Kingdom

VB.OT (Pret); Dip Vocational Rehabilitation (Pret). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0513-7423; Lecturer, Occupational Therapy Department, Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Therapeutic Sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIBSc OT (Wits); MSc OT (Wits); PhD (Wits). http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3236-7803; Senior Lecturer and Manager of eFundanathi, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIIBMR PT (Ife); MSc Physiotherapy (UWC); PhD (Wits). http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5265-4212; Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Department of Physiotherapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIIIMCSP (UK); MSc Community rehabilitation (Pret); MA Leadership Management and Executive Coaching (Wits); PhD (Wits). http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4562-6413; Professor, Head of School, School of Therapeutic Sciences, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Learning styles of health care professionals are unique and tend to be profession- specific. This study aimed to compare the learning styles of undergraduate occupational therapy and physiotherapy students and to determine the relationship between preferred learning styles, demographic factors, and academic performance

METHOD: The study design was a cross-sectional, descriptive study. Undergraduate occupational therapy and physiotherapy students completed a self-developed questionnaire and the Grasha-Reichmann Learning Style Inventory

RESULTS: A total of 313 students with a mean age of 19.6±1.58 years participated in this study. The results showed that students preferred the collaborative (75%) learning style, with the first-year students scoring significantly higher in the collaborative style (3.97±0.48; p<0.001). The male students (2.67±0.65) scored higher in the competitive learning style than female students (2.20±0.62; p=0.001, d=0.757). The competitive learning style, when controlling for sociodemographic variables, is a significant predictor of an increase in academic performance in English language (B=2.28, [0.60-3.96]), physics (B=3.62, [0.22-7.02]) and overall academic performance (B=2.12, [0.34-3.90

CONCLUSION: The predominant preferred learning styles are the collaborative and participant styles. The application in the teaching space should be carefully considered for the selection of teaching approaches and activities. This study points to the Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy programmes need to align to the collaborative style and respond with a variety of teaching methods. The associations shown between preferred learning styles and demographic variables point to the need to pay attention to diversity when selecting teaching approaches and activities

Keywords: Grasha-Reichmann Learning Style Inventory, learning styles, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, undergraduate students

INTRODUCTION

The South African higher education landscape is heavily burdened with the pressures of massification while striving to compete in the global knowledge economy. In the past two decades the enrolment rate in the occupational therapy and physiotherapy degrees at the University of the Witwatersrand have increased drastically, resulting in much higher lecturer: student ratios. In the strive to maintain the standard of education and continue to produce highly skilled occupational therapy and physiotherapy graduates, this study seeks to increase our understanding of how our student body prefers to learn.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Since the 1950s, many theories related to learning style and learning preferences have emerged, yielding over 70 different scales attempting to measure the identified constructs1,2. Rice and McK-endree2 suggest that there are three primary categories of learning style measures: consitutional, ability and instructional preference measures. Critics of the value of learning style theories have sought to debunk the notions of a relationship between learning style, actual learning behaviours and academic performance3, but focus largely on the consitutional and ability measures which tend to categorise a learner as a single type that remains stable, such as being a kinaesthetic learner. Rice and McKendree2 suggest that the instructional preference measures contextualise learning behaviour and approach to study, offering the position that learning preference is flexible, with the best learners having the ability to adapt their learning preference, style and behaviour with changing contexts and demands. The Grasha-Riechmann Student Learning Style Survey (GRSLSS) is an instructional preference scale.

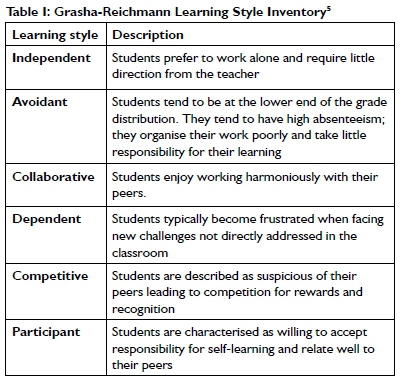

The learning styles of students in health professions have been studied using the GRSLSS internationally4 and locally, focused on the relationship of physiotherapy students' learning style preferences and their performance in gross anatomy1. The Grasha-Reichmann Learning Style Scales Inventory identifies six learning style preferences, and it is believed that students make use of a combination of these learning styles to a greater or lesser extent5. This system of classification prevents learning style stereotyping and provides an incentive for growth in under-used learning style areas. The GRLSS was developed in the USA and although it has been used in another South African study1, no research on the South African contextual validity could be found. The six learning styles are described as Independent, Avoidant, Collaborative, Dependent, Competitive and Participant (Table I, adjacent).

Learning styles are unique for health care disciplines and tend to be profession-specific 6. Medical students generally favour competitive, collaborative or participative learning styles7,8, while students studying pharmacy are more inclined to adopt the 'converger' learning style (similar to the independent learning style of the GRSLSS)4,6. Studies comparing learning style preferences amongst physiotherapy and occupational therapy students are scarce9,10, although various individual studies have been conducted on the respective disciplines' learning styles1,11,12. Furthermore, the majority of studies focusing on learners in these fields have made use of other learning style inventories, particularly Kolb's Learning Style Inventory (LSI)9-11. In a review of different learning-styles instruments, Ferrell13 found that while a small overlap does exist between constructs, "the instruments were clearly not measuring the same thing"13:1. Thus, different models of learning styles may provide novel insights. As such, the GRSLSS was chosen for this study as researchers were most familiar with this tool.

In a Turkish study4, the dominant learning style for physiotherapy students was the 'collaborative' learning style. Additionally, it was found that the academic performance of the sample was negatively correlated with 'avoidant' learning styles and positively correlated with 'participant' learning styles4. A South African study found the most popular learning styles for physiotherapy students to be 'dependent' and 'independent' learning styles1. Most of the learning style studies in physiotherapy and occupational therapy disciplines used Kolb's model13. In an Australian study, the dominant learning style for physiotherapy students was identified as the 'assimilator' while the two dominant learning styles for occupational therapy students were identified as 'converger' and 'diverger' learning styles9. Another study reported the majority of physiotherapy students as 'reflective observers'14.

Students entering higher education in South Africa hail from highly diverse schooling contexts, with a stark disparity in access to resources, quality education, cultural experiences and rural to urban divide. Other studies have not reported differences in learning styles based on contextual categories. It is therefore important to consider the potential impact of these demographic factors on students' learning strategies. Factors influencing learning styles may include gender15, year of study16, culture17 and academic performance4. Considering the link between academic performance and physical fitness, sports participation may play a role, but this relationship has not yet been explored18.

It has been reported that up to 30% of students prefer multiple learning styles when measured using a constitutional measure such as the VARK (Visual, Aural, Read/write, Kinaesthetic) scale; however, the majority of medical students preferred a single learning style8. A student preferring a single learning style may need an appropriate teaching style aligned with their preferred learning style, to in turn, maximise efficiency. It is important to expose the single style learner to a variety of learning styles to produce a more balanced learner19. Exposing students to various learning styles may optimise the students' learning experience and throughput. Awareness of the preferred learning styles among occupational therapy and physiotherapy students, as well as the factors associated with the preferred learning style, are therefore crucial. The primary aim of this study was to establish and compare the learning styles of undergraduate occupational therapy and physiotherapy students and to determine the relationship between demographic factors and students' learning styles. A secondary aim was to establish the relationship between learning styles and academic performance.

METHOD

Study design

The study design was a cross-sectional, descriptive study. Quantitative analysis was used to analyse the demographic information and GRSLSS. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were adhered to20.

Study setting and participants

Total population sampling was used for the 2017 undergraduate students, specifically first-, second- and third-year students at the Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy Department, University of the Witwatersrand. No exclusion criteria were set and all first- to third-year students within the respective departments were invited to participate. *Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the associated tertiary institution in the spirit of the Helsinki Declaration (M140540).

Assessment tools

A questionnaire was developed and administered to collect information on age, gender, career field of interest, year of study, physical activity participation and previous year's marks in the main subjects, as well as an open-ended question related to teaching philosophy. Content validity was established by a panel of experts consisting of four occupational therapists and four physiotherapists. Panel members had between 10 and 40 years of professional experience. The outcome of the open-ended question of the study is not presented in this paper.

Learning style was evaluated by using the GRSLSS, which is a 60-item standardised, self-administered questionnaire that determines an individual's preferred learning style. Six learning styles are described: independent, avoidant, collaborative, dependent, competitive and participant21. Cronbach alpha coefficient for internal consistency was 0.89 for the GRSLSS22. The GRLSS was developed in the USA and although it has been used in another South African study1, no research on the South African contextual validity seems to exist. The learning styles were calculated according to the guidelines put forward by Grasha21 and the sum of the scores for each of the learning styles was divided by 10. The learning styles were further categorised into low, moderate and high as shown in Table II (above).

Procedure

Data were gathered using a self-administered questionnaire as described under assessment tools. A pilot study was performed and included 26 participants from the Department of Nursing Education. Following the pilot study, no changes were made to the questionnaire.

However, the suggested time taken to complete the questionnaire was increased. Instructions were adapted to include more detail. The time taken to complete the two questionnaires was twenty minutes.

For the main study, researchers made appointments with the sample groups via the student class representatives of the first, second and third year of study. Verbal, as well as written information about the study was provided to both groups. Participation was voluntary, and completion of the questionnaires implied consent. No identifiable information was collected to ensure anonymity. Students knew the researchers and to reduce participant bias, students could return the completed questionnaires to the class representatives or the departmental secretaries, from whom the completed questionnaires were then collected for analysis.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using IBM SPSS (v25) and JASP (v0.9.2) software programmes. Frequencies and descriptive statistics were produced for all variables. The Fisher 2-tail exact test was used to compare the following demographic information: Field of study, year of study, gender, and ethnicity. Comparisons of the preferred learning styles which were identified amongst (1) occupational therapy and physiotherapy students, and (2) the gender of the participants, were made using the independent t-test, except where Levene's test was significant (p<0.05), suggesting a violation of the equal variance assumption. In such cases, the Mann Whitney U test was used. For the independent t-test, the effect size is given by Cohen's d while for the Mann-Whitney test, the effect size is given by the rank bi-serial correlation. Cohen's d can generally be interpreted as 'small' effect size (0.2), 'medium' effect size (0.5), and 'large' effect size (> 0.8).

The rank bi-serial correlation (r) can be interpreted as small (0.1), medium (0.3), and large (0.5). MANOVA tests were run comparing differences in learning styles based on (1) ethnicity, (2) home province, and (3) year of study. Partial eta-squared statistics were used as measures of effect size: here an effect size of 0.01 is small, 0.06 is medium and 0.14 is large. Where significant differences were found, Bonferroni post hoc tests were run to investigate these differences further. Linear regression models were computed to determine whether learning styles predicted academic performance (Matric English, First Year Physics, Second Year Anatomy, and the average of these scores) while controlling for age, department and gender. All tests were performed using an alpha of 0.05. Missing data points were excluded on a list-wise basis.

RESULTS

Study participants

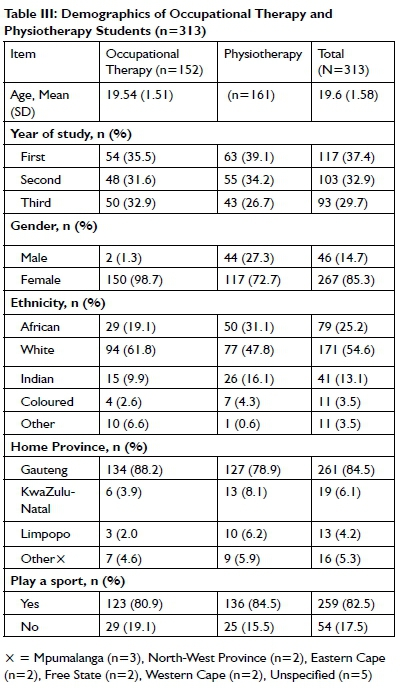

A total of 313 students with a mean age of 19.6 ± 1.58 years participated in the study and their demographics shown in Table III (p42). The group consisted of 152 (48.6%) occupational therapy students and 161 (51.4%) physiotherapy students. The majority of students were female (n=267; 85.3%), and 259 (82.5%) of the students participated in at least one sport.

Low, moderate, and high ranking of learning style preference

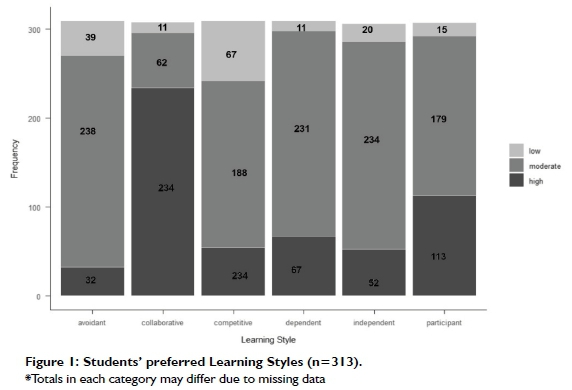

Using the classification of the learning style preference into low, moderate and high as defined by Grasha5 (Table II, p41), students' learning styles are shown in Figure 1 (p43). The majority (n=234; 75.0% of 308) of students scored in the high preference range for the collaborative learning style, followed by the participant learning style with 36.8% (n=113 of 307) of the students scoring in the high preference range. The competitive learning style was least preferred with 21.7% (n = 67 of 309) of the students scoring in the low preference range (Figure 1, p43).

The majority of students, 58.4% (n=180), scored in the high preference range for two or more learning styles, while 9.7% (n = 30) showed no learning style scoring high enough to indicate a preference for any of the six learning styles.

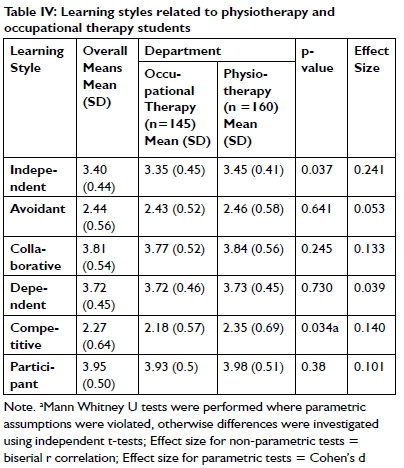

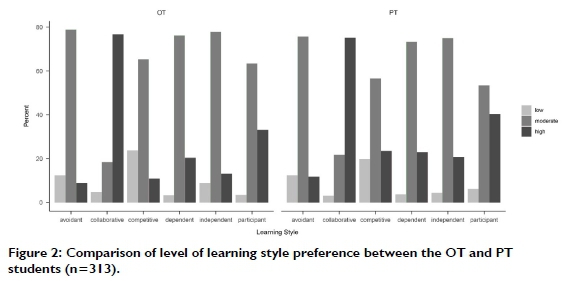

Learning style preferences between physiotherapy and occupational therapy students

Table IV (above) shows the comparison of learning style preferences between physiotherapy students and occupational therapy students. There was a significant difference between the two professions in the independent learning style (p=0.037) and the competitive learning style (p=0.034). However, the effect size for both these findings was small (d=0.241 and d=0.140, respectively). This is further illustrated by the categorical data presented in Figure 2 (p43), where more occupational therapy students scored in the low preference range for the independent (occupational therapy n=13, 9.0%; physiotherapy n=7, 4.4%) and competitive learning styles (occupational therapy n = 35, 23.8%; physiotherapy n = 32, 19.9%) and more physiotherapy students scored in the high preference range for both styles (Independent: occupational therapy n=19, 13.1%; physiotherapy n=33, 20.6% Competitive: occupational therapy n=16, 10.9%; physiotherapy n=38, 23.6%), indicating that should a student show preference for either of these styles they are more likely to be a physiotherapy student.

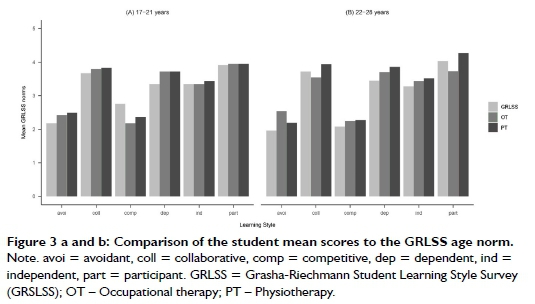

Age norms and degree enrolment

Figure 3a and 3b (p43) illustrate how the occupational therapy and physiotherapy student learning style preferences compare to the norms for the age range 17-21 years5 and 22-28 years respectively. The younger students of both degrees scored generally above the age norm in all learning styles except for the competitive style, for which both groups scored well below the Grasha-Reichmann Learning Style Scales Inventory norm of 2.76 (Figure 3a, p43). Interestingly, the older student groups both score well above the Grasha-Reichmann Learning Style Scales Inventory age norm for the avoidant learning style and the occupational therapy students mean scores fall below the Grasha-Reichmann Learning Style Scales Inventory norms for the collaborative and participant learning styles.

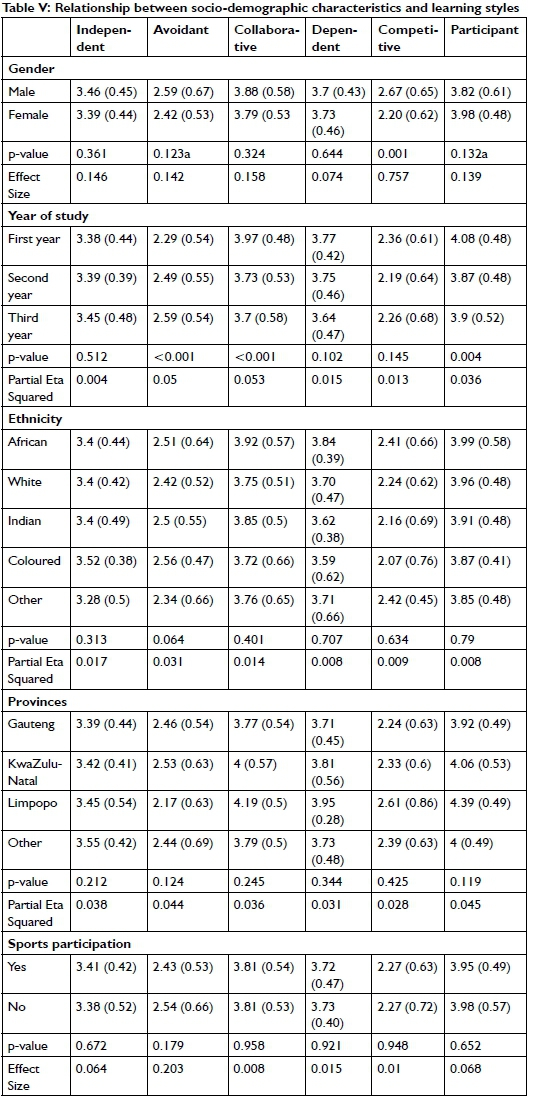

Relationship between demographic characteristics and learning styles.

Table V (p44) outlines the comparative statistics to describe the relationship between the demographic variables and learning styles. More male students preferred the competitive learning style when compared to female students, and this finding had a large effect size (p=0.001; r=0.757). No gender difference in terms of any of the other learning styles existed (Table V, p44). First year students had significantly lower avoidant scores than both second (p=0.027) and third years (p<0.001) while having significantly higher collaborative scores than both second (p=0.003) and third-year students (p=0.001). Additionally, first-year students had significantly higher participant learning style scores than both second year (p=0.007) and third-year students (p=0.007) (Table 5 p44). No significant differences in learning styles were found based on the self-selected ethnicity of the participants. No significant differences in learning styles were found based on the home province of the students in the sample. Students could indicate whether they participated in sport or not. This information was compared to the students' learning styles. There was no significant difference between students' learning styles and their participation in sport (p > 0.05) (Table V, p44).

Academic performance and learning styles

To determine the association between academic performance and learning styles, linear regression models with individual subject scores (percentages) including matric English (77.51±6.51), first-year physics (65.32±10.59), and second-year anatomy (69.21±8.65) as well as the average of these scores (69.02±10.75) were set as the dependent variables, while the learning style scores were set as predictors. The age, department, and gender of the participants were controlled for. As illustrated in Table VI (p45), participants with competitive learning were more likely to achieve higher grades in Matric English as well as first-year physics. No learning styles were significant predictors of second-year anatomy grades. When testing the means of these grades, it was found that only the competitive learning style was a significant predictor of academic achievement in the sample.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Learning style is how a person prefers to learn and can be based on knowledge and/or experience23. Previous studies confirmed that although students often have a preferred learning style, most students are multimodal learners, using more than one learning style24,25, Similarly, 58.4% of the occupational therapy and physiotherapy students at the University of the Witwatersrand preferred more than one learning style when measured using the GRSLSS. The importance of understanding the learning style lies in its use and therefore for meaningful contribution, a facilitator needs to explore different strategies in learner self-awareness and articulation with learning style. Furthermore, learners can be encouraged to explore beyond their formal learning style26. However, to produce a more balanced learner, a variety of learning styles need to be employed and the application in the teaching space should be carefully considered for the selection of teaching approaches and activities19.

Interestingly, in this group of students, the learning styles that were dominant and in the high category as categorised through the GRSLSS ranking (Table II, p42), were the collaborative followed by participant style (Figure 1, p43), similar to the results of the Turkish study4. Those in the moderate category were avoidant, independent and dependent, similar to the results of the South African study1. Although students presented with a combination of learning styles, most students in this study scored in the high preference range for the collaborative learning style. Chen et al.27:4 describe collaborative learning as "the extent to which the environment allows for interactions among the learners to acquire knowledge and skills and complete the tasks". The teacher needs to create opportunities for students and be approachable while students need to acquire information and share it with peers and teacher28. The occupational therapy and physiotherapy departments already include a variety of teaching activities to cater for the collaborative learning style such as working in small groups (projects and discussions), flipped classrooms and problem-based learning.

The learning styles of the students in this study were varied (Figure 1, p43). The learning activities these students prefer are also likely to be diverse. Students with a competitive learning style are motivated by doing better than their peers29. As such, due to their desire to be the dominant figure in the classroom, they would prefer group activities where they can receive recognition in the company of their peers30. The independent learner, on the other hand, prefers to work alone at his or her own pace29. Also, these students who are

Note. Differences in learning styles scores for the variables of Gender and Sports Participation were analysed using independent t-tests, or a Mann Whitney Ua test where assumptions of normality were violated. All other variables were analysed using MANOVA. Effect size for non-parametric testsa = biserial r correlation; Effect size for parametric tests = Cohen's d.

independent learners participate in projects independently and determine their personal goals and learning process15. From the results of our study, both occupational therapy and physiotherapy students prefer the collaborative style, although more physiotherapy students preferred the independent and competitive styles (Figure 2, p43). Also, physiotherapy students scored higher in the competitive style although this finding needs to be interpreted with caution due to the small effect size (Table IV, p42).

Interestingly, despite knowing students' learning styles and adapting to them in terms of teaching approaches, the outcomes in terms of academic performance remain unchanged in a study by Dinçol et al.31. They explained that students' preferred learning style might vary depending on their age, the subject matter and the environment. Students may therefore benefit from a more nuanced approached where facilitators adapt to the learning styles by taking into consideration these anticipated changes in age, environment and subject matter31. This study then sought to understand how the different demographic variables namely age, gender, ethnicity, place of origin, year of study and sport participation, relate to the learning styles.

When the occupational therapy and physiotherapy students' learning style preferences were compared to the age norms suggested by Grasha5, it was evident that the younger students, aged 17-21 years, scored well below the normative mean for the avoidant learning style. This result was consistent with findings by Shead et o/.1. Further consistent with Shead et o/.1 the older students (aged 22-28 year) scored notably above the normative mean for the avoidant learning style, particularly evident with the occupational therapy students. These older occupational therapy students also scored below the mean for the collaborative and participant learning styles. Twelve of the 15 occupational therapy students in this age group were in their third year of study, which is well known to be a high-pressure year, juggling five subject courses and their first exposure to assessing and treating clinical cases in a variety of settings. The older physiotherapy students were more evenly distributed across the four years of study (first to fourth year), possibly accounting for the consistency of their scores compared to their younger physiotherapy counterparts. Contextual differences between the population in which the norms were established and the population included in this study need to be considered, however, no norms of the GRLSS in the South African context exist.

Gender played a role in the competitive learning style category where male students scored higher than female students. This was the only learning style where a large effect size in terms of gender comparison was present. In another South African study, Shead et o/.1 found that female physiotherapy students preferred the dependent learning style, while the majority of male students preferred the participant learning style as measured using the GRLSS. In their study, the competitive style was the least preferred style amongst both male and female students. Although it should be noted that their study only included 17 male students, compared to the 46 male students included in this study. However, no difference in the competitive learning style was found amongst science and humanities students, while differences were detected in all other styles (female n=493; male n = 546)7. The higher scores attained by male students in the competitive category, therefore seem to be unique to our study and further research is needed to explore this finding. Physiotherapy students also showed a higher score in the competitive style, when compared to occupational therapy students. However, the majority of male students (n=44) formed part of the physiotherapy cohort, while only two were occupational therapy students. Therefore, the difference between the two departments may just be a function of the number of male vs female students who formed part of the cohorts.

When looking at students' preferred learning style in this study, it is interesting to note the students' learning style seems to vary over the four years of study, with first-year students scoring higher in the collaborative and participant styles in comparison to second- and third-year students who presented with higher average scores in the avoidant learning style. First-year students come to university often excited, motivated and open to new learning experiences32. These students are probably used to didactic learning in school and are now exposed to a variety of teaching methods, including more group work33. In this study, even though first-year students appear to be less avoidant compared to second and third-year students, Amira and Jelas34 found that age was not a predictive factor for the avoidant learning style. Avoidant learners do not participate in activities and appear to be disinterested5. Second- and third-year students, on the other hand, have already been exposed to collaborative and group work in their first and second year of university and may dislike this type of learning. In this study, these students appeared to be less collaborative and participative than the first-year students. Students are often marks-driven and working in groups with challenging dynamics is likely to impact on a student's marks. It is, therefore, possible that second- and third-year students prefer to work more independently and rely on their own effort rather than working in groups. It is further possible, due to the exponential increase in workload and the complexity of the work from first to second to the third year that older students struggle to manage their workload and therefore present with a more avoidant learning style5. It is important to consider this finding in light of being a trained professional, as the ability to work collaboratively is vital for health care professionals to provide quality patient care35. Raising students' awareness of their preferred learning style will be of benefit as students with a propensity for dependent and avoidant learning styles may experience difficulties in adapting to participative learning environments that emphasise teamwork, motivation, individual responsibility, and team dependence. Çolak36 reports that such students have a propensity for surface learning and become withdrawn, employ more surface learning, and aim for attaining minimum requirements. Students with cooperative and competitive learning styles have been reported to achieve better deep learning scores36. Facilitators who create an environment to expose students to a variety of learning styles will likely gain better results.

The group of students in this study were diverse in their background and ethnicity (Table I, p40). Inequalities within the education system in South Africa created by the legacy of apartheid has called on all higher education institutes to engage with diversity actively. Diversity awareness is thus currently on the agenda of all South African Universities due to the political history of the country. Diversity should be considered and incorporated into all aspects of teaching. The results of this study, however, found no relationship between students' ethnicity or the province that they came from and their learning styles. Amira and Jelas34 also found that ethnicity did not affect learning styles of students at the Universiti Kebangsaan in Malaysia. Students presented with a variety of learning styles regardless of their ethnicity or where they came from. According to Zoghi et al.37, learning styles are seen as patterns of behaviour influenced by various factors such as experience, values and roles and not merely personality characteristics. This is important, as teachers need to include a variety of activities to suit different learning styles based on the students' inherent learning style regardless of ethnicity, providing an opportunity for learning in a way that different students within different subject areas and environment can engage.

In our study, no relationship between sports participation and preferred learning style could be determined. We hypothesised that those who participate in at least one sport as opposed to those who do not, may prefer certain learning styles considering that there is a link between sports participation and academic performance18. A relatively low number of students did not participate in sports (n=54; 17.5%), which may have influenced our results. Future research should explore learning styles as a confounding factor in the search for predictors of academic performance.

Our results show that participants with a competitive learning style were significantly more likely to achieve higher grades in matric English, first-year physics and overall marks, however this only applies to a 17.5% (n = 54 of 309) of our sample who scored in the high range for this learning style (Figure 1 p43). The avoidant learning style did not show any significant relationship with the specific subjects of physics, English and anatomy but in the overall average mark, a significant decrease was evident. These results show that the 10.4% (n = 32 of 309) of students in this study who scored in the high range for the avoidant learning style may perform in individual subjects but cumulatively their performance may be declining (Figure 1, p43). This is unsurprising given that avoidant learners are known to withdraw slowly and participate less36. A study by ilçin et al.4 among physiotherapy students in Turkey, reported similar results where there was a negative correlation between avoidance learning styles and academic performance. Amira and Jelas34, found a decrease in academic performance in students with a collaborative learning style, which was not the case in this study. The competitive learning style in this study was however associated with an increase in academic performance which was the opposite in the study by Amira and Jelas34. Competitive learners compete with other learners and prefer a teacher-centred classroom where activities are provided, while the participatory learner wants to participate in activities and prefer discussion-based lectures15. Further research is warranted to explore the exact mechanisms which explain the link between a competitive learning style and higher academic performance.

CONCLUSION

Overall, there is little difference between the learning styles of the occupational therapy and physiotherapy students in this study, with the predominant preferred learning styles being the collaborative and participant learning styles. Both programmes are well suited to cater for the collaborative and participant learnings styles through small group teaching and the active nature of clinical skills development. Demographic variables such as age, gender and year of study seem to play a role in the choice of preferred learning style. The competitive learning style was a significant predictor of academic achievement. There may be benefit in monitoring the students who develop a tendency towards the avoidant style (which tends to happen more in the older students and later years of study), as they may be more at risk of poor academic performance than their peers. While it is important to understand learning styles for both the students and the facilitator, the application in the teaching space should be carefully considered for the selection of teaching approaches and activities.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Benita Olivier, Lizelle Jacobs, Vaneshveri Naidoo, Nikolas Pautz, Paula Barnard-Ashton, Rulaine Smith, Hellen Myezwa and Adedayo Tunde Ajidahun, contributed to the conceptualisation of the study, collection of the data and statistical analysis of the findings. All the authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Prof Douglas Maleka, Prof Patricia de Witt and Mrs. Julie Jay in this research.

Competing interest and Funding

The authors declare no competing interest. The Faculty of Health Sciences' Research Committee of the University of the Witwa-tersrand partially funded this research project.

REFERENCES

1. Shead D, Roos R, Olivier B, Ihunwo A. Learning styles of physiotherapy students and teaching styles of their lecturers in undergraduate gross anatomy education. African Journal of Health Professions Education. 2018;10(4):228-34. https://10.7196/AJHPE.2018.v10i4.1070. [ Links ]

2. Rice S, McKendree J. e-Learning. In: Swanwick T editor. Understanding medical education: evidence, theory and practice. 2nd ed. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2013. p. 161-73. [ Links ]

3. Husmann PR, O'Loughlin VD. Another nail in the coffin for learning styles? Disparities among undergraduate anatomy students' study strategies, class performance, and reported VARK learning styles. Anatomical sciences education. 2019;12(1):6-19. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1777. [ Links ]

4. ilçin N, Tomruk M, Yesilyaprak SS, Karadibak D, Savci S. The relationship between learning styles and academic performance in TURKISH physiotherapy students. BMC Medical Education. 2018;18(1):291. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1400-2. [ Links ]

5. Grasha AF. Teaching with style: A practical guide to enhancing learning by understanding teaching and learning styles. Pittsburgh: Alliance publishers; 1996. [ Links ]

6. Crawford SY Alhreish SK, Popovich NG. Comparison of learning styles of pharmacy students and faculty members. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2012;76(10):1-6. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7610192. [ Links ]

7. Baneshi AR, Tezerjani MD, Mokhtarpour H. Grasha-richmann college students' learning styles of classroom participation: Role of gender and major. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism. 2014;2(3):103-7. [ Links ]

8. Barman A, Jaafar R, Rahim AFBA. Medical Students' Learning Styles in Universiti Sains Malaysia. International Medical Journal. 2009;16(4):257-60. [ Links ]

9. Brown T, Cosgriff T, French G. Learning Style Preferences of Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy and Speech Pathology Students: A Comparative Study. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 2008;6(3):1-12. [ Links ]

10. Brown T, Vryens V, Williams B, Jaberzadeh S, Roller L, Palermo C, McKenna L, Hewitt L, Sim J. The learning styles of undergraduate occupational therapy and physiotherapy students from one Australian university using the Kolb learning style inventory. Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009;37(2):22-8 [ Links ]

11. French G, Cosgriff T, Brown T. Learning style preferences of Australian occupational therapy students. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2007;54:S58-S65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00723.x. [ Links ]

12. Llorens LA, Adams SP. Learning style preferences of occupational therapy students. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1978;32(3):161-4. [ Links ]

13. Ferrell BG. A factor analytic comparison of four learning-styles instruments. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1983;75(1):33-9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.75.1.33. [ Links ]

14. Mountford H, Jones S, Tucker B. Learning styles of entry-level physiotherapy students. Advances in Physiotherapy. 2006;8(3):128-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14038190600700278. [ Links ]

15. Azarkhordad F, Mehdinezhad V. Explaining the students' learning styles based on Grasha-Riechmann's student learning styles. Journal of Administrative Management Education and Training. 2016;12(6):241-7. [ Links ]

16. Auyeung P, Sands J. A cross cultural study of the learning style of accounting students. Accounting & Finance. 1996;36(2):261-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.1996.tb00310.x. [ Links ]

17. Gündüz N, Özcan D. Learning styles of students from different cultures and studying in Near East University. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2010;9:5-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.107. [ Links ]

18. Santana C, Azevedo L, Cattuzzo MT, Hill JO, Andrade LP Prado W. Physical fitness and academic performance in youth: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2017;27(6):579-603. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12773. [ Links ]

19. Kolb AY, Kolb DA. Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2005;4(2):193-212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.17268566. [ Links ]

20. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vanden-broucke JP Initiative S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61(4):344-9. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [ Links ]

21. Grasha AF. The dynamics of one-on-one teaching. College Teaching. 2002;50(4):139-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567550209595895. [ Links ]

22. Babadogan C, Kilic G. Learning modalities of sixth grade students and the learning and teaching modalities of the English teachers at primary schools. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012;46:2467-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.504. [ Links ]

23. Hsieh S-W, Jang Y-R Hwang G-J, Chen N-S. Effects of teaching and learning styles on students' reflection levels for ubiquitous learning. Computers & Education. 2011;57(1):1194-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.004. [ Links ]

24. Nuzhat A, Salem RO, Hamdan NA, Ashour N. Gender differences in learning styles and academic performance of medical students in Saudi Arabia. Medical Teacher. 2013;35(sup 1):S78-S82. https://10.3109/0142159X.2013.765545. [ Links ]

25. Alkhasawneh IM, Mrayyan MT, Docherty C, Alashram S, Yousef HY. Problem-based learning (PBL): assessing students' learning preferences using VARK. Nurse Education Today. 2008;28(5):572-9. https://10.1016/j.nedt.2007.09.012. [ Links ]

26. Sadler-Smith E, J. Smith P Strategies for accommodating individuals' styles and preferences in flexible learning programmes. British Journal of Educational Technology. 2004;35(4):395-412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0007-1013.2004.00399.x. [ Links ]

27. Chen C, Jones KT, Xu S. The Association between Students' Style of Learning Preferences, Social Presence, Collaborative Learning and Learning Outcomes. Journal of Educators Online. 2018;15(1):1-16. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1168958. [ Links ]

28. Grasha AF. A matter of style: The teacher as expert, formal authority, personal model, facilitator, and delegator. College Teaching. 1994;42(4):142-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.1994.9926845. [ Links ]

29. Diaz DP Cartnal RB. Students' learning styles in two classes: Online distance learning and equivalent on-campus. College Teaching. 1999;47(4):130-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567559909595802. [ Links ]

30. Amir R Jelas ZM, Rahman S. Learning styles of university students: Implications for teaching and learning. World Applied Sciences Journal. 2011;14(2):22-6. http://www.idosi.org/wasj/wasj14(IPDL)11/5.pdf. [ Links ]

31. Dinçol S, Temel S, Oskay ÖÖ, Erdogan ÜI, Yilmaz A. The effect of matching learning styles with teaching styles on success. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011;15:854-8. https://10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.198. [ Links ]

32. Kantanis T. The role of social transition in students': adjustment to the first-year of university. Journal of Institutional Research. 2000;9(1):100-10. [ Links ]

33. Ramnarain U, Schuster D. The pedagogical orientations of South African physical sciences teachers towards inquiry or direct instructional approaches. Research in Science Education. 2014;44(4):627-50. https://10.1007/s11165-013-9395-5. [ Links ]

34. Amira R, Jelas ZM. Teaching and learning styles in higher education institutions: Do they match? Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2010;7:680-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.10.092. [ Links ]

35. Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;8(3):1-26. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub2. [ Links ]

36. Çolak E. The effect of cooperative learning on the learning approaches of students with different learning styles. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research. 2015;15(59):17-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2015.59.2. [ Links ]

37. Zoghi M, Brown T, Williams B, Roller L, Jaberzadeh S, Palermo C, McKenna L, Wright C, Baird M, Schneider-Kolsky M. Learning style preferences of Australian health science students. Journal of Allied Health. 2010;39(2):95-103. [ Links ]

* Corresponding Author: Benita Olivier. Email address: benita.olivier@wits.ac.za

* Ethical clearance for this study was granted prior to the enactment of the amended POPIA on 2021-07-01