Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.51 n.2 Pretoria Aug. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2021/vol51n2a2

ARTICLES

Promotion of Access to Information Act: Key issues for occupational therapists

Matty van Niekerk*

B.Proc (UFS); B.Arb (UP); DipVocRehab (UP); MSc Med (Bioethics & Health Law (Wits). http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7505-5709; Lecturer, Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Increasingly, healthcare practice, including occupational therapy, is influenced by non-medical legislation, such as the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA), which regulates the right to access information held by others. While the PAIA does not intend to limit existing access to information rights, such as a patient's right to access their health information in terms of the National Health Act, the PAIA does provide better clarity regarding access to patients' information than health-related legislation and policies, including those of the Health Professions Council of South Africa

METHOD: Using normative analysis of a desktop review of relevant legislation, case law and literature, this paper aims to provide guidance to occupational therapists about patients' right to access their information in terms of five themes: Theme 1: What is the difference between a public and a private body?

Theme 2: Who may request access to information?

Theme 3: Is there a prescribed process to be followed when requesting access to information?

Theme 4: What is the nature of information to which access is granted?

Theme 5: Are there any circumstances under which access may reasonably be refused?

CONCLUSION: The paper concludes that, while existing health-related legislation and policies already provide the right to access to information, application of specific guidance from the PAIA e.g., using prescribed forms to request access, could serve to better protect patients' and practitioners' interests alike

Key words: PAIA, National Health Act, healthcare practitioners, patient records, access to information, occupational therapy record-keeping, health-related legislation and policies.

INTRODUCTION

Internationally and locally, healthcare practice, including occupational therapy, is increasingly influenced by legislation other than medically-oriented laws such as the National Health Act (NHA)1. Healthcare practitioners (HCPs) must be familiar with, and abide by, an increasing amount of relevant legislation2, not only to ensure compliance, but also to guide decision-making in clinical and ethical/professional situations. The law describes the minimum standard of what ought to be done2. Healthcare practitioners, therefore, can no longer rely solely on their knowledge of the rules and guidelines of the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) to guide their clinical and ethical decision-making, but must familiarise themselves with non-medical legislation relevant to their fields of practice. This paper will focus on one of two sets of legislation pertaining to information, namely the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA)3. The PAIA must be distinguished from the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA)4. While sometimes collectively referred to as freedom of information legislation, the PAIA aims to facilitate access to information held by others, while the POPIA pertains to information security, privacy, and confidentiality. Importantly, the POPIA has introduced important concepts that must be considered when interpreting the PAIA5 and has resulted in some amendments to PAIA and redrafting of PAIA regulations. POPIA changes, as well as issues arising from the new draft PAIA regulations, will be highlighted where necessary.

As HCPs, occupational therapists are legally required to gather and keep information about people who use their services. The HPCSA requires HCPs to keep information for at least six years from the date of becoming dormant6; in other words since the last interaction with a patient (such as at discharge). In the case of children, records must be kept until three years after the child's eighteenth birthday and in the case of persons who are "mentally incompetent"6, records must be kept for the duration of such a person's lifetime6.

Since the Constitution of South Africa6 in Section 32 guarantees everyone the right to access information that someone else holds about them, especially where this information is required to exercise or protect any right7, it follows that HCPs must know how to give persons access to their information. The PAIA was enacted to give effect to this Constitutional right. It applies to all records, since the creation of the record (Section 3)3, and thus also applies to records that came into existence prior to the Act5,8,9.

To date, there has been no paper which describes in detail how the PAIA affects occupational therapists (and other South African healthcare practitioners). Two previous papers aimed at informing healthcare practitioners about the PAIA are either too brief, looking at broad, general principles of the PAIA2, or too narrow, looking only at providing access to information when a third party has an interest in the information being accessed5. This paper attempts to expand on the earlier papers about access to information, and to provide practical answers to questions practitioners may encounter in everyday practice regarding a patient's right to their information, both in the public and private sectors. Recent developments, including amendments to PAIA regulations, necessitates an updated paper on PAIA. The aim of this paper is to propose guidance for practitioners and is based on a normative analysis of the PAIA as well as relevant case law literature, further distinguishing this paper from its predecessors. Five themes, including the nature of information/ documentation to which access is given, were used to guide the analysis and provide direction to occupational therapists in practice.

For the purposes of this paper, the person about whom the occupational therapist keeps information will be referred to as a patient, even though in the fields of medico-legal assessment, vocational rehabilitation or work practice, these service users are not necessarily patients in the traditional sense of the word. The use of patient rather than client, is to avoid confusion, as the word client may refer to both claimants and instructing parties such as attorneys or insurers in the mentioned fields of practice. This paper aims to inform general practice, regardless of practice area.

METHOD

The author uses a normative analysis method. A normative analysis entails a desktop review of legislation, policies and other relevant literature10 in order to derive an answer to the question as to how people should act, or what should/ought to be done in a given situation. It is derived from normative ethics, which is the branch of ethics attempting to answer normative questions, as well as finding reasons behind norms for behaviour11. This paper thus attempts to provide guidance to occupational therapists in dealing with requests for access to information, using five themes arising from the PAIA, relevant case law and literature:

Theme 1: What is the difference between a public and a private body?

Theme 2: Who may request access to information?

Theme 3: Is there a prescribed process to be followed when requesting access to information?

Theme 4: What is the nature of information to which access is granted?

Theme 5: Are there any circumstances under which access may reasonably be refused?

These five themes were developed based on a (desktop) document review12 of PAIA and the literature. The themes were specifically informed by the process of requesting access to information and having regard for the practice contexts of occupational therapists.

The PAIA, POPIA, case law, grey and peer-reviewed literature were purposively selected for the (desktop) document review to explain rights and duties in relation to requesting access to information in general, but also in healthcare, and more specifically, occupational therapy contexts. The paper poses arguments that differ from the usual medical interpretation of a patient's rights to access (as primarily expressed in HPCSA policies and guidelines), defended through interpretation of PAIA, POPIA, the existing literature and case law.

DISCUSSION

Provisions from the PAIA, literature and case law are discussed under the five themes identified above.

1. What is the difference between a public and a private body?

The PAIA aims at improving transparency regarding information and applies to the records kept by both private and public bodies. To understand who may request information as well as the processes to request access to information, it is necessary to understand the distinction the PAIA makes between public and private bodies, as well as the categories of each. O'Connor9 explains that there are three categories of public bodies and three categories of private bodies in terms of Section 1, as can be seen in Table I above. The difference between the categories of public persons is important because different duties and rights exist for the different categories. Importantly, occupational therapists are employed by a variety of public and private bodies, further necessitating an understanding of these bodies to ensure fair access to information.

The PAIA separates provisions regarding public and private bodies, although in many instances the requirements are similar. Part 2 (Sections 11-49) of the PAIA describes access provisions pertaining to public bodies, and Part 3 (Sections 50-73) describes access provisions pertaining to private bodies.

Both public and private bodies have a duty to produce a PAIA manual that explains, among others, how information should be requested from the respective bodies and to whom access to information requests should be directed8,14. The PAIA manuals must be submitted to the Information Regulator (previously these were to be submitted to the Human Rights Commission)14 and should be easily accessible by the public (thus it could be published on the body's website and should be available at its offices)8,9,14. Public hospitals may not necessarily have their own PAIA manuals, though will adhere to the PAIA manual of the National or Provincial Department of Health.

An important differentiation between public and private bodies is that private bodies in specified sectors, with fewer than 50 employees, and whose turnover are below Gazetted thresholds, are exempt from producing PAIA manuals until 31 December 202115 (the date has been extended a number of times and is correct at the time of publishing). This exemption also applies to private occupational therapy practices with a turnover below R15 Million,5,15 as they fall in the sector of "Community, Special and Personal Services". However, it has been argued that private practitioners who regularly gather information about claimants on behalf of others such as insurance companies, ought to produce PAIA manuals, or at the very least have a policy regarding access to information5. Other differences in duties and rights related to public and private bodies (e.g., in relation to the process of requesting access) will be highlighted in the sections below.

2. Who may request information?

For the purposes of this discussion, the PAIA provisions will be related to patients' information, although the PAIA is not limited to medical information only. In terms of Section 1 of the PAIA, someone who is requesting access to information is called a requester. Natural (human beings) or juristic persons (e.g., companies, universities, and statutory bodies such as the HPCSA), or someone acting on their behalf, may request access to information from either public or private bodies. Occupational therapists may therefore receive access requests from patients, their parents/ spouses/partners, lawyers acting on behalf of the patient or even a medical aid scheme who insures the patient. A restriction is placed on public bodies, who cannot request information from other public bodies, but may request information from private bodies3,9, thus, the HPCSA cannot request information from the Gauteng Department of Health, but they may request information from an insurance company or medical aid.

The PAIA provides for the mandatory protection of the privacy of natural people (both living and deceased) where others request access to their information. This protection is addressed in Sections 34 and 63 where public and private bodies hold a patient's information. Aligned to the protection of natural people's privacy, a requester may only access a patient's information, if:

• The patient has consented in writing that their information may be disclosed to the requester, or

• The information is already public, in which case no consent is necessary, or

• The person whose information is requested has been informed at the time of providing the information to the public/private body that the information is part of a category of information that could be made public (e.g., information contained on the HPCSA register, including a practitioner's registration number and qualification details which are publicly available on the HPCSA's website, or contact details that appear in a telephone directory), or

• The information is about the patient's physical or mental health, and the patient is under the requester's care, and it is in the patient's best interests to disclose the information, and the patient is either a child (i.e., under 18), or is an adult who cannot understand the nature of the request for access to information, as may be the case with adults with severe cognitive impairment, or

• The information is about a deceased person and the requester is their next of kin, or has been authorised in writing by the next of kin to access the information, or the person has been deceased for more than 20 years; or

• The information is about a person's tenure (employment history) at a private or public body, including among others, information about the person's job description and salary.

If none of these conditions are met, and it would be an unreasonable disclosure of personal information, a requester's request to access a patient's (someone else's) information must be denied.

With respect to information about a patient's physical or mental health mentioned above, it should be noted that a requester must meet all the requirements indicated under the fourth point above. Should the patient not be in the requester's care, or can understand the nature of the access request, information cannot be disclosed without the patient's consent. Practically speaking, where an occupational therapist treats a patient with an intellectual disability, the occupational therapist will be permitted to provide information about the patient to a parent. Where such a patient does not have a living parent, but is under the care of an adult sibling, the sibling will be entitled to access information.

Children whose parents are divorced have additional considerations. Most importantly, the occupational therapist must always act in the child's best interests and record not only a decision, but also the reasons for the decision. While both parents usually retain parental rights and responsibilities and thus should be able to access their children's information, it is sufficient to obtain consent for treatment from the parent with custody and guardianship (but they must consider the views of the other parent). By virtue of Sections 13(1) (b) and (c) and Section 13(2) of the Children's Act children must have access to their own health information, regardless of their age. This information must be provided in such a way that they can understand it16. Requiring adherence to the PAIA's procedural requirements, particularly completion of Form C (described below), will enable the occupational therapist to make a decision about disclosing information to any parent (or anybody else) about a child. In instances of acrimonious divorces, an occupational therapist must seek her own legal counsel about acting in the child's best interests.

3. How must access to information be requested?

It is important to note that the Act provides for access to information requests to be made to either the information officer of a public body, or the head of a private body as identified in their respective PAIA manuals (but in terms of the POPIA, both public and private bodies must have information officers from 1 July 2021). Where private practices have been exempted from producing PAIA manuals, patients nonetheless have the right to request access to any information held about them (and they are not exempted from registering an information officer with the Information Regulator in terms of POPIA). The author urges private occupational therapy practice owners not to delegate the function of handling access requests. Practice owners are urged to register themselves as the information officer and rather appoint another employee such as the accountant or receptionist as deputy information officer. Furthermore, all employees and independent contractors must know what the practice policy and procedures are about access to information requests, to ensure uniformity and consistency in handling access requests. Sections 11 (public bodies) and 50 (private bodies) of the PAIA both indicate that persons must be granted access to information if they have complied with the procedural requirements of the PAIA and the information is not subject to grounds for refusal in terms of the PAIA (as described in Theme 2 related to Sections 34 and 63, and Theme 5 of this paper). The question then arises as to the procedure to be followed when requesting access to information (see Table II, above).

Access to information must be requested in writing. The PAIA prescribes that Form A (public bodies) or Form C (private bodies) must be completed and submitted to the body's information officer by hand, post, fax or e-mail, in terms of Sections 18 and 53 respectively3,9,17. The author recommends that in the case of exempted practices, practitioners use Form C (private bodies) for access to information requests. Practitioners who work in the public sector, or in the private sector in non-exempted workplaces should familiarise themselves with their employer's PAIA manual to aid patients in requesting access to their information where necessary. Both forms A and C require the requester to provide their details, as well as the details of the record to be accessed. The most important difference when requesting access to information from public and private bodies, is that when requesting access to information from a private body, in terms of Section 50, the requester must describe the right they are exercising or protecting and why the information being requested is necessary to protect or exercise this right. Thus, Section 50 places one additional requirement on requesters that is not required by Section 11, i.e. reasons for accessing information3,9. In the case of healthcare practitioners, the right being accessed is likely as simple as a patient's right to their information in terms of the NHA1. It should be noted that in the draft PAIA regulations published for comment in April 202118, a single form to request access to information is suggested. Form 2 of the draft regulations requires particulars of the right being exercised or protected and a description of why the record is required to exercise or protect the right. Should Form 2 be promulgated, the distinctions in the process of accessing information from public and private bodies brought about by Forms A and C will no longer be in effect.

When a person who is illiterate or has a disability requests access to information from a public body, the request can be made orally (in terms of Section 18(3)) and the information officer must complete the form and provide a copy to them. Importantly, private bodies do not have a corresponding duty. Nonetheless, since occupational therapists work with people with a variety of disabilities, they may carry a greater burden to accommodate disabled requesters. Practitioners are reminded that the HPCSA and the NHA1 prescribe that patients have access to their information, without a prescribed processes to request such access to information. Furthermore, the PAIA cannot be interpreted to remove access already granted by other legislation/provisions9. To deny access based on a formality such as inability to complete a form, would therefore be unreasonable for a private body such as an occupational therapy practice/ practitioner. Additionally, requiring the use of Form C (or A), should not be seen as an obstacle or a reversal of an already existing right in terms of the NHA1 and/or HPCSA policies, but as an attempt to clarify issues which may be hidden or unclear, such as the identity of the requester in relation to the person whose information is sought, particularly if they are not the same person.

In terms of Section l9, public bodies must provide reasonable assistance to any requester with completing Form A, not only people with disabilities or people who are illiterate. Private bodies do not have a corresponding duty9, but in the case of occupational therapists, it would be reasonable to provide assistance with completing the form.

There is a prescribed fee that is payable for requesting access to information in respect of both public and private bodies3,17. Public and private bodies may not levy fees that are different from the prescribed fees. The fees are not intended to provide a barrier, but to cover reasonable costs of producing access.

Public and private bodies must respond to a request for access to information within 30 days. Both public and private bodies may request a 30-day extension. If access is refused by a national or provincial government department or a municipality, the requester must submit an internal appeal within 60 days, upon receipt of which the governmental department has 30 days to make a decision17,19. A requester must be furnished with reasons for refusal of access, and where an internal appeal process is not available, the requester will have to approach the high court to appeal the decision of other public and private bodies.

There are instances when PAIA cannot be used to access records/information. In terms of Section 7 of PAIA a requester cannot rely on the provisions of PAIA to access records after criminal or civil court proceedings have commenced. Expanding on this section of PAIA, the Supreme Court of Appeal found in the case of Unitas Hospital v Van Wyk20that PAIA does not intend to change the rules of court in relation to discovery procedures. When court proceedings between parties have been initiated, the parties must abide by the rules of discovery and cannot circumvent those rules by requesting access via PAIA9,20. This is another reason to insist on procedural compliance with respect to requesting access using Forms A or C. An occupational therapy example would be that a claimant cannot request access to the occupational therapy records based on PAIA after they have started litigation against the occupational therapist for malpractice.

4. What information can a person access?

Information that is accessed in terms of PAIA must be in the form of a record. In Section 1 of the PAIA, a record is defined as recorded information, regardless of the form or medium of such a record. It could therefore be a written record, an audio-recording or a vid-eorecording, clinical session notes and any other notes an occupational therapist has made about a patient. Thus, one cannot request access to information if there is no record of such information. Similarly, where a record exists, no matter how informal, access must be provided. Practitioners are reminded that the Protection of Personal Information Act4 (POPIA) has greatly expanded the definition of personal information, which also includes someone's opinion about a patient. Unless occupational therapists are willing to disclose their opinions about a patient to the patient, they are advised to keep their opinions out of records.

Importantly, the record must be in the control of an official of the public or private body from whom access is requested in their capacity as official of the private or public body. The record could also be in possession of an independent contractor of such a private or public body in their capacity as independent contractor, e.g., an occupational therapist who conducts a functional capacity evaluation on behalf of an insurer. The POPIA introduced a new concept in respect of persons controlling information about others, namely that of the responsible party (RP). The RP has rights and duties in relation to the record and information, including its safe storage, preservation and providing access4. Patients must always be informed who the RP is when their information is gathered, thus it has been argued that an independent contractor such as an occupational therapist acting on behalf of an insurer, is not the RP but an Operator, in terms of POPIA. The insurer is the RP and thus access should be sought not from the independent contractor, but the RP5. In usual clinical contexts, depending on the rules of a public body, the head of the occupational therapy department or the practice owner is likely to be the RP. Since promulgation of the POPIA, PAIA has been amended to bring PAIA into better alignment with POPIA. However, it should be noted that even with the publication of the revised PAIA regulations in April 2021, the important distinction between a RP and operator does not appear to have found its way into PAIA yet. Thus, Van Niekerk's argument5 remains unique.

Originality is not relevant for the right to request access21. This means that one does not have to request access from the original author, owner or creator of a record or access an original record. This is important, especially in the case of HCPs for two reasons: firstly, a HCP may need their original records at some point to mount a defence either in a professional conduct or a malpractice matter. Secondly, even though the HCP may be the original creator of a record, they may not be the RP and thus, it may be better to request access from the RP5. The information officer may give access to copies of the original, but not necessarily the original record itself. In the case of occupational therapists who use standardised tests, care should be taken to ensure that the copies facilitate the purpose of requesting access. For example, where the request is to obtain a second opinion, it must be possible to interpret the copies of the tests. Copies should therefore be clear, and where possible in colour. If this is not possible, the requester may view the original at the occupational therapist's practice.

In the case of Claase v Information Officer of South African Airways22 the Supreme Court of Appeal further clarified that a record means the actual record, not a summary thereof. A requester, therefore, does not have to be satisfied with an information holder's summary or interpretation of the record's contents - they can insist on accessing the actual record9,22. For occupational therapists, this judgement may mean that it would not be sufficient to merely give access to a report. Access should also be granted access to the documents on which the report is based, e.g., clear copies of standardised test booklets. Providing access to the actual record is another reason why practitioners should not record unnecessary opinions about a patient in their records.

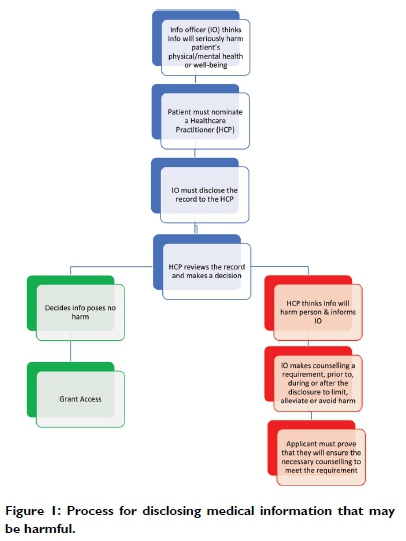

There is a special provision regarding accessing medical records, which is governed by Sections 30 and 61 when requesting access from public and private bodies, respectively. Should the information officer (or head of the private body) believe that granting access to medical information will cause serious harm to the requester or the patient's physical or mental health or well-being, the information officer may consult with a health practitioner nominated by the requester or the patient prior to granting access. Figure 1 below describes the procedure:

Where the nominated HCP agrees that the information may cause harm, the nominated HCP may recommend that the patient/requester receives counselling prior to, during, or after the disclosure. Both the nominated HCP and the counsellor must therefore be granted access to the actual record (not a summary) in order to execute their respective duties in terms of PAIA.

5. Are there any circumstances under which access may reasonably be refused?

The PAIA does make provision for reasonable grounds of refusal. When read together with the POPIA, it is clear that access to a patient's healthcare information must be dealt with circumspectly, not only because POPIA places strict limitations on who may process healthcare information, but also due to the duty of confidentiality on HCPs about patients' information. Where there is a duty of confidentiality in terms of an agreement between a HCP and a patient, Sections 37(1) (a) and 65 of the PAIA in relation to public and private bodies respectively, hold that confidentiality may be a reasonable ground to refuse access to a patient's information where the patient is not the requester. Nonetheless, the provisions of Sections 34 and 63 discussed above in Theme 2, must be applied and thus could constitute reasonable grounds of refusal, except where the patient is under the care of the requester and is either a child or an adult who cannot understand a request to information.

It should be noted that where the occupational therapist is not the RP that is not an acceptable ground for refusal. In fact, Van Niekerk5 makes this clear in her argument about referral to the RP: the requester must be informed (again) who the RP is, and that the request will be transferred to the RP. Such referral must occur within l4 days of receiving the access request. The occupational therapist should not refuse access and instruct the requester to request access from the RP as that would constitute unjust refusal of access. Instead, the occupational therapist should transfer the request after informing the requester of the transfer5.

There are limited instances when an occupational therapist may use a requester's non-compliance with procedural aspects of access requests as grounds for refusal. Public bodies may only refuse access based on non-compliance with procedural requirements in terms of Section 19 (i.e., completing Form A), if the information officer has notified the requester of the intention to refuse access. The information officer must also notify the requester that they can receive assistance from an official of the public body, give them time to access such assistance and provide the assistance before rejecting the request. Furthermore, the requester must have reasonable opportunity to comply with the procedural requirements before the public body denies their request based on non-compliance3,9,17. No corresponding provision for private bodies exists, thus, private bodies may be able to refuse access on the basis of non-compliance with the procedural requirements9. However, in view of the fact that persons have the right to access their health information both in terms of the NHA1 and HPCSA guidelines (e.g. Booklet 5) and neither of these prescribe a procedure to access information, it will be ill-advised for HCPs to refuse access due to non-compliance with procedural requirements. Occupational therapists especially should rather assist patients where necessary to comply with procedural requirements. Because patients have a right to access their information, practitioners need to be careful when refusing access. Reasons for refusing access must be recorded.

CONCLUSION

The paper highlighted how the PAIA (and to a lesser extent, POPIA) provides important guidance to occupational therapists regarding access to patients' information and records. The normative analysis highlighted how occupational therapists should implement the PAIA in relation to five key topics, namely (1) the distinction between private and public bodies and the implications for processing access requests, (2) who may request information, (3) the nature of information that may be accessed, (4) the process to request information and (5) reasonable grounds of refusal of access. While private practices are exempt from producing PAIA manuals15, practitioners are not exempt from following the provisions of the PAIA and other legal provisions when handling requests for access to information.

Importantly, the PAIA favours access to information9. Where patients request access to their own information, access could be granted in terms of the NHA1 , which is less onerous than the PAIA in terms of procedural requirements for accessing one's own information2. However, where people like teachers, parents of competent adults, and others, request access to information about a patient, it is advisable that practitioners follow the provisions of the PAIA.

Access to information requests should preferably be in writing, and in the case of private bodies exempted from producing PAIA manuals, this paper recommends that practitioners use Form C to facilitate access to information requests. Requests should be made to the practice owner, and the paper recommends that practitioners do not delegate this function to others in the practice.

Where a practitioner who acted as an independent contractor (and is thus not the RP for access to information purposes) receives a request for access to information held by another body (who is the RP), it is prudent to transfer the request to the RP as soon as possible, preferably within 14 days of receipt5. Because PAIA cannot be used to access records after litigation has commenced, it would be better for an occupational therapist to transfer the access request to the RP, since the occupational therapist may not know whether a requester or a patient is litigating against the RP and thus could inadvertently be in breach of the rules of discovery by providing access. Avoiding breaching the rules of discovery is an additional pragmatic reason for transferring a request, beyond what Van Niekerk5 has already argued.

While not intending to limit existing rights of access to information, e.g., in terms of the NHA1 and HPCSA policies, the PAIA is prescriptive regarding the process of requests for access to information. Compliance with the PAIA ensures clarity of procedures for both practitioners and patients.

REFERENCES

1. South Africa. National Health Act No 61 of 2003. Available from https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a61-03.pdf [ Links ]

2. Van Der Reyden D. Legislation for everyday Occupational Therapy practice. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 2010, vol. 40 no. 3 27-34. Available from http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/sajot/v40n3/07.pdf [ Links ]

3. South Africa. Promotion of Access to Information Act No 2 of 2000. [ Links ]

4. South Africa. Protection of Personal Information Act No 4 of 2013. Available from https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/20l409/3706726-llact4of20l3protectionofperson-alinforcorrect.pdf [ Links ]

5. Van Niekerk M. Providing claimants with access to information: A comparative analysis of the POPIA, PAIA and HPCSA guidelines. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law 2019 vol. 12: 32-37. http://doi.org10.7196/SAJBL.2019.v12il.656 [ Links ]

6. Health Professions Council of South Africa. Guidelines on the Keeping of Patient Records, Booklet 9. 2016. https://www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/Professional_Practice/Conduct%20%26%20Ethics/Booklet%209%20Keeping%20of%20Patient%20Records%20September%20%2020l6.pdf (Accessed 2 Dec 2020). [ Links ]

7. South Africa. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 108 of 1996. [ Links ]

8. Currie I, Klaaren J. The Promotion of Access to Information Act Commentary. Claremont: Siber Ink, 2002. [ Links ]

9. O'Connor T. PAIA unpacked: a resource for lawyers and paralegals. Braamfontein: Freedom of Information Programme: South African History Archive. 20l3 https://foip.saha.org.za/static/paia-unpacked-a-resource-for-lawyers-and-paralegals (accessed 2 Dec 2020). [ Links ]

10. Mathibe-Neke JM. Ethical practice in the nursing profession: A normative analysis. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law 2020 vol 13 no 1: 52-56. [ Links ]

11. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF (eds). Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. [ Links ]

12. Payne G, Payne J. Key Concepts in Social Research. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2014: 60-66. [ Links ]

13. M & G Limited and Others v 2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee South Africa Limited and Another 2011 (5) SA 163 (GSJ). [ Links ]

14. South African Human Rights Commission. 20l4 Guide on How to Use the Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000. Johannesburg. 2014. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_documents/SAHRC-PAIA-guide2014.pdf (Accessed 5 November 2020). [ Links ]

15. South Africa. 202l. Promotion of Access to Information Act 2000: Exemption of certain private bodies from compiling manual. Government Gazette No 44785, 30 June 2021 (Published under Government Notice No. 397), pp. 3-4. [ Links ]

16. Mahery P, Proudlock P, Jamieson L. A guide to the Children's Act for health professionals, Fourth Edition, 2010. https://ci.org.za/depts/ci/pubs/pdf/resources/general/ca_guide_health%20prof_20l0.pdf (Accessed l0 November 2020). [ Links ]

17. South African Human Rights Commission. Guide on how to use the Promotion of Access to Information Act 2 of 2000. 2014. English Edition. Johannesburg: South African Human Rights Commission, https://www.sahrc.org.za/home/21/files/Section%2010%20guide%2020l4.pdf (Accessed 12 September 2017). [ Links ]

18. South Africa. Promotion of Access to Information Act 2000: Draft Regulations Relating to the Promotion of Access to Information Act, Government Gazette No 44479. 23 April 2021 (Published under Government Notice GON 221). [ Links ]

19. South African History Archive. PAIA poster - Accessing Information Using PAIA, 2017 https://foip.saha.org.za/static/visual-training-tools (Accessed 2 December 2020). [ Links ]

20. Unitas Hospital v Van Wyk [2006] SCA 32 (RSA). [ Links ]

21. CCII Systems (Proprietary) Ltd v Fakie Nomine Officio and Others 2002 JDR 0897 (T) [ Links ]

22. Claase v Information Officer of South African Airways [2006] SCA 163 (RSA). [ Links ]

* Corresponding Author: Matty van Niekerk Email: Matty.Vanniekerk@wits.ac.za