Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.51 n.1 Pretoria Apr. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2021/vol51n1a5

ARTICLES

Novice Occupational Therapist's Experience of Working in Neonatal Intensive Care Units in KwaZulu-Natal

Michaela HardyI, *; Pragashnie GovenderII; Deshini NaidooIII

IB.OT (UKZN), M.OT (UKZN). https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8928-6137; Occupational Therapist at Linden Lodge School, 61 Princes Way, London, United Kingdom

IIB.OT (UDW), M.OT (UKZN), PhD (UKZN). https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3155-3743; Associate Professor at UKZN, Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu Natal (Westville Campus), South Africa

IIIB.OT (UDW), M.OT (UKZN), PhD (UKZN). https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6276-221X; Academic Leader at UKZN, Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Health Sciences University of KwaZulu Natal (Westville Campus), South Africa

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The neonatal intensive care unit, an environment designed to meet the needs of severely ill neonates, is an area of practice for occupational therapists. However, there is limited evidence available around the training and practice of South African occupational therapists in these units

AIM: To explore community service occupational therapists' experiences of working in neonatal intensive care units in the KwaZulu-Natal public health sector

METHODOLOGY: This study followed an explorative qualitative design. Homogenous purposive sampling was employed to recruit 12 therapists that participated in in-depth interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Data were analysed thematically by inductive reasoning initially, followed by categorisation via deductive reasoning using the theory of occupational adaptation

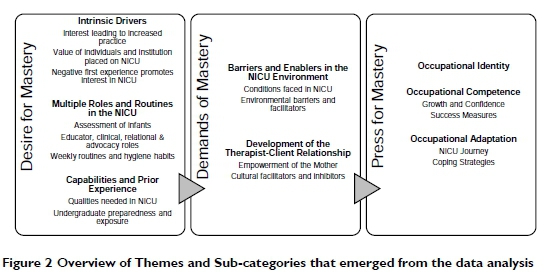

RESULTS: Three themes emerged; the desire for mastery (including intrinsic drivers, multiple roles and routines in the NICU and capabilities and prior experiences); demand for mastery (including barriers and enablers in the NICU environment and development of the therapist-client relationship) and press for mastery (development of occupational identity, competence and adaptation

CONCLUSIONS: The newly qualified occupational therapists who participated in this study appeared to be able to overcome the challenges of working in the highly technical environment of the NICU. There is a need for greater support and training of community service occupational therapists in this specialised field of practice

Key words: occupational therapy training, community service occupational therapists, neonatal intensive care units, clinical experiences, public health sector

INTRODUCTION

The neonatal period is a vulnerable phase posing many health risks. Preventing deaths during this period is a major global concern1. In a middle-income country such as South Africa, spontaneous pre-term births and birth trauma are leading causes of death2. The World Health Organisation (WHO) established 'goal three' of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), which aims to reduce neonatal deaths to 12 per 1000 live births and eliminate all preventable deaths in children under the age of five by the year 20301. Accordingly, the South African Department of Health (DOH) has aligned their vision of reducing maternal and child mortality as a priority in the National Service Delivery Agreement3.

The neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a specialised environment designed to meet the needs of severely ill neonates4. The Nurturing Care Framework, endorsed by WHO, promotes a holistic view of care by focusing on infant health, nutrition, competent caregivers, security and safety, as well as early learning opportunities1. Given this holistic view, the occupational therapist has an important role to play, as part of the multidisciplinary team (MDT), within the NICU5. However, this may be daunting for new therapists delivering services in this high-risk environment6,7, as the services provided by occupational therapists require specific knowledge, skills, and equipment to ensure neonate safety4. Globally, the role of the occupational therapists in a NICU is well defined, and the occupational therapist is viewed as a valuable member of the MDT, performing functions such as splinting, positioning and handling, feeding, providing caregiver support, and implementing environmental alterations7. However, many occupational therapists may feel incompetent in delivering specialised NICU services due to lack of training or not having prior experience8.

Community service in South Africa is a compulsory year of supervised practice for health professionals, after a four-year occupational therapy undergraduate degree, followed by registration as an independent occupational therapy practitioner with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA). Community service occupational therapists (CSOTs) have raised issues related to their lack of preparedness for delivering specialised services in NICUs due to their limited exposure during undergraduate training9. Despite this limited training, newly qualified occupational therapists in South Africa are still required to assume roles in high-care settings such as the NICU within the public sector7. In the South African context, there is limited literature about the role and scope of occupational therapists in the NICU. Additionally, there is limited literature that explores how community service therapists adapt to the demands of working in NICUs in public sector hospitals. This study therefore aimed at gaining an understanding of occupational therapist CSOTs' experiences of working in NICUs in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) public health sector. It is important to understand the process of adaptation the CSOTs undergo, as this aids in the development of their identity and the role they play within NICUs, which ultimately influences service delivery in this area.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The NICU is a setting that caters for high-risk neonates and new-born infants who demonstrate signs of the increased possibility of morbidity or mortality, focusing on family-based care4. NICU's require adequate facilities and highly trained professionals to deal with the infants' specific needs4. Globally, working in a NICU is recognised as an advanced area of practice, and health professionals are required to have advanced clinical reasoning skills and specialist abilities to deal with this technical and emotionally taxing field of work10. Every year, approximately four million neonates die globally, with most deaths occurring within the first 24 hours of life11. The most common causes of death of neonates worldwide include infections, pre-term births and asphyxia, with low birth weight (LBW) being a serious risk factor for further complications11. Modern advances in neurodevelopment have led to a shift towards focusing more on the future developmental outcomes of the infant12. This has resulted in increased research into how the NICU environment, parental stress and healthcare providers influence the infant's neurodevelopment; with the importance of the parental role being recognised worldwide and increased efforts have been made to encourage family participation7,8,11.

Most neonatal deaths in South Africa are caused by asphyxia, prematurity, LBW and infections, which parallels global statistics2,13. A retrospective study at a rural hospital in the KZN province, which focused on monitoring the neonatal admissions, deaths, and discharges in the NICU, found that a very low birth weight (VLBW) and prematurity were high predictors of death, usually occurring within the first three days following admission2. The authors of this study concluded that many of these deaths could be avoidable with a better quality of care2. Similarly, a study that accessed participants in the central and eastern regions of Tshwane, found many preventable factors associated with neonatal mortality including poor accessibility to NICU beds with ventilators, hospital-acquired infections, delayed seeking of medical help and inadequately trained health-professionals14. Despite of the mentioned South African research, early intervention is often not initiated in diverse contexts due to inaccessible resources, poverty factors and a lack of help-seeking behaviour because of low education levels and services not made well known to the public13. NICU facilities are required at all regional and tertiary hospitals in South Africa. However, most births occur in district hospitals or community health centres; therefore, it is crucial that neonatal services are available at these levels with a high care facility15. Occupational therapists working in district hospitals, mainly community service therapists, may be required to deliver services to this vulnerable population16.

Occupational therapists working in the NICUs in KwaZulu-Natal are often faced with the burden of increasingly large numbers of patients due to the high birth rate in this province15. Additionally, most persons living in KZN (89, 9%) have a low to middle socioeconomic status, with high poverty and unemployment rates15. Furthermore, KwaZulu-Natal also has the highest number of social grant beneficiaries out of all nine provinces in South Africa (23,2%), with high numbers of Care Dependency and Child Support Grant beneficiaries15. This means that the CSOT may also have to consider severe financial restrictions and supplying low-cost interventions to the families in the NICU. The South African context is unique and therefore the effect of the environment is required to understand service delivery. Culture is an important aspect to consider especially when providing maternal and child healthcare17. Many cultural practices, especially regarding mother and infant care, continue despite limited knowledge of potential health benefits or possible harm, specifically in developing countries. This is usually due to family pressure, set routines or convenience17.

Many neonatal deaths are preventable with good quality of care; therefore, to reach the SDGs, certain standards need to be established and achieved. Lincare18 postulated that specific standards should be in place to provide quality child healthcare. This includes referrals to advanced or specialist care units for complex cases and an appropriate number of nursing staff working in NICUs18. It was suggested that all staff working in the NICU should have a thorough introduction and training on arrival as well as periodic in-services to ensure continual professional development in this setting18. Additionally, the NICU's physical environment requires careful consideration such as ensuring adequate lighting, ventilation, temperature, and the availability of hand-washing facilities18. Excessively loud noises and bright lights can be stressful to the high-risk neonate.

The role of the occupational therapist in the NICU cannot be understated. Combining the vulnerable infant, distressed parents and technically advanced environment can make the NICU a challenging area to work within. Vergara and colleagues10 divided the roles of an occupational therapist into three areas within the NICU context, namely 'infant-orientated', 'family-orientated' and 'therapist-orientated'. Within the area of 'infant-orientated', the occupational therapist would perform duties such as splinting, positioning and modulating the external environment. The area of 'family-orientated' would focus on assisting the parents in effectively fulfilling their parental role, and 'therapist-orientated' refers to the occupational therapist using their time and resources as well as their therapeutic use of self to produce favourable outcomes and prevent burnout10. There have been rapid advances in neonatology; therefore, intervention has also quickly evolved; moving from sensory supplementation programmes to a more hands-off approach that prioritised family collaboration12. An unmatched case-control, retrospective study that investigated the effect of cultural practices on neonatal survival in Indonesia, found that many cultural factors impacted on the neonate such as inapt antenatal care, specific breastfeeding practices, knowledge of hypothermia and the use of Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) as well as poor neonatal follow-ups17. This study highlighted the importance of family and community education to increase safety for neonates. Services also include discharge planning, neonatal assessments, and education, while the occupational therapist aims to match the infant's capabilities with the surrounding environment19. The occupational therapist works within an MDT; therefore, roles may overlap with other professions5.

In the context of South Africa, there is limited literature on the role and scope of occupational therapy within the NICU setting. A quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive survey, which focused on the training and role of occupational therapists in NICU, was used to access occupational therapists practicing within South Africa. They were members of the Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa (OTASA) and previous experience in the NICU was not an inclusion criterion7. The results indicated that there was a lack of skills and knowledge about the NICU which could be the result of a lack of undergraduate training in this field and/ or uncertainty on the exact role of the occupational therapist in the NICU7. In addition, there is the need for in-depth orientation programmes for new graduates, especially when working in remote rural healthcare settings and specialised environments, which is not always provided to community service professionals20. These highlight some of the underlying causes behind the challenges that community service occupational therapists face in delivering a NICU service.

Additionally, poor awareness and understanding of occupational therapy, as well as overlapping roles with other members of the MDT, negatively affected occupational identity9. Occupational identity refers to developing a sense of self and who the individual wants to become through repetitive occupational participation21. This is closely related to occupational competence21. There is limited literature on how working in the NICU impacts on the CSOT's occupational identity as no previous studies, specifically done in a South African context, is currently available and a need was thus identified to investigate novice occupational therapists' experiences of working in NICUs.

METHODS

This study's methodology is reported against the relevant domains of the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ), which is advised for explicit and comprehensive reporting of qualitative studies22.

Reflexivity and Research Team

The first author was a newly qualified occupational therapist, having a year of experience post community service at the time of this study. The study was developed out of her own experiences as a CSOT. Several of the participants were known to the first author in her professional capacity; hence her positionality was declared by a series of reflexive statements through this study. A hybrid stance as researcher-therapist was occupied in this study. Strategies to ensure trustworthiness in this study included reflexive journaling, peer debriefing, investigator triangulation in data analysis and respondent validation, and developing and maintaining an audit trail23.

Study Design

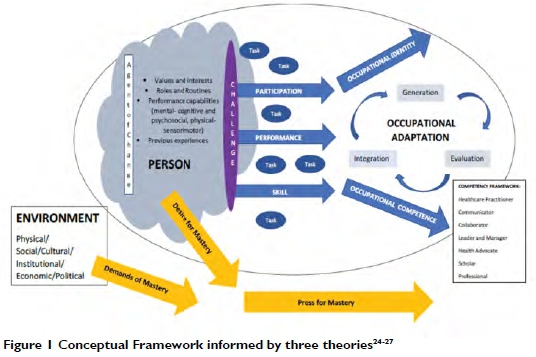

Methodological and Theoretical Orientation: This study followed an explorative qualitative design with the use of in-depth interviews. Three theories formed the basis of the conceptual framework that also aided in the analytical process for this study. This framework was developed using three main theories, namely the Model of Human Occupation24, the Theory of Occupational Adaptation25,26 and The Ecology of Human Performance27. The conceptual framework highlights how the person is inextricably linked to their environment, which places various demands on them. To be competent, the process of occupational adaptation is undertaken to overcome the occupational challenge.

Setting: The study was located in KZN Province of South Africa. Interviews were conducted face-to-face, either at a mutually agreed venue in person or via Skype; with the presence of the first author and participant/s only (there were no non-participants present).

Participants: Homogenous purposeful sampling23 was employed to recruit participants who (i) were currently registered with the HPCSA, (ii) had completed their community service at a KZN facility between 2014 and 2017, and (iii) had a minimum of one month's exposure to a NICU as a CSOT. Of the 12 participants in this study, one was male, and the rest were female (n=11). The mean age of the participants was 26 years old. Majority of the participants attended the University of KwaZulu-Natal for their undergraduate training (n=9), while others were from Stellenbosch University (n=1), the University of Pretoria (n=1) and the University of Witwatersrand (n=1). Majority of the participants completed their community service at district hospitals (n=8), with a few at regional hospitals (n = 3) and one at a tertiary hospital. Most participants had a year of NICU exposure (n=8) while the others had between three to five months. The participants completed their community service across nine different districts in KZN, with more than half (n=7) participants reporting that they had permanent supervision by an occupational therapist. Few participants (n = 3) had attended additional formal training on neonatal intensive care during their community service year.

Data Collection: A biographical questionnaire was completed prior to the interviews. In-depth interviews followed. These included individual Skype interviews (n=3), individual face-to-face interviews (n=4), one dyad and one triad interview. The afore-mentioned conceptual framework (Figure 1) informed the interview schedule; with questions centred round the person (volition, habituation, and performance capacity), environment (physical and social) as well as outcomes (competence, identity and adaptation) related to NICU practice as a CSOT. The interviews spanned a maximum of 90 minutes and were audio-recorded, and manually transcribed.

Data analysis

Data were analysed thematically23,28 by inductive reasoning initially, resulting in first level codes followed by categories identified by the first author. These were exposed to review and critique by two additional coders (co-authors) as part of investigator triangulation. These were then subjected to categorisation via deductive reasoning using the theory of occupational adaptation25 and aligned to the conceptual framework (Figure 1, p30) by all coders. Respondent validation occurred by ensuring that participants had the opportunity to view the resultant themes.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from a Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BE084/I8), and the Health Research and Knowledge Management directorate of the KZN Department of Health (DOH) (KZ_20I804_003). Ethical principles adhered to in the study included confidentiality (by the use of pseudonyms and limited linking and de-identified data); autonomy (through voluntary participation and informed consent), and ensuring the participants were aware of their right to withdraw without prejudice.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was ensured by using purposeful sampling23 techniques to enrich the content of the data collected and to heighten credibility. A secure setting was created during the interviews to increase the likelihood of honest and genuine responses. Thie interviews were audio-recorded on a digital recorder an d transcribed allowing for the nse of verbatim quotes. The same interview schedule, guided by the conceptual framework (Figure 1 above) was used with all participants, with additional probing questions to facilitate deeper discussion. This allows for the research to be replicated to ensure dependability. Sampling continued until redundancy was reached. Confirmability was ensured through reflexivity (via reflexive statements and journaling) and analyst triangulation23 (all three authors assisted in the data analysis and interpretation). Transferability was ensured th rough the use of thick description of themethods, findings, and data analysis as part of the audit trail23.

Findings and Discussion

The study findings resulted in three emergent themes and related sub-categories (Figure 2).

These are augmented by relevant verbatim quotes [Table I, p31] and supported by the available empirical literature. Generally, newly qualified CSOTs have to overcome the challenges of working in the highly technical environment of the NICU, despite their lack of advanced knowledge, skills and prior experience. The therapists revealed progression from the experience of challenges in fulfilling roles in the NICU, towards a desire to master the environment and gaining more confidence in the process. The working environment created pressures and demands for them to deliver services, which inevitably led to the adoption of coping strategies, thereby enabling adaptation to their roles as occupational therapists in NICUs.

Desire for Mastery

Every professional, especially when newly qualified, has the innate desire for mastery and competence in their chosen field of work29. A perceived occupational challenge acts as motivation to generate an adaptive response to become competent30. The participants in this study experienced a negative first visit to the NICU due to feelings of incompetence. Schultz31 highlights this as part of the evaluation phase in the internal adaptive response. Intrinsic factors also influenced the CSOTs' desire to excel in the tasks in their environment. The passion and volition of the CSOTs, which is described as the driving force behind initiating a task30,32, influenced their level of involvement in the NICU and their process of occupational adaptation. Those who were interested in paediatrics sought to develop their competence in this area. This was achieved by becoming autonomous learners, seeking mentorship from more experienced professionals, and attending additional courses or in-service training. Additionally, the participants had to be resilient and emotionally strong and had to be able to communicate openly with team members. Other participants mentioned the need to be empathetic and supportive of the parents. These findings corroborate Eraut's30 finding that learning from others is the most common means of on-the-job training.

The participants reported a few enabling factors of the physical environment, including the warmth, cleanliness, and suitable hygiene protocols. Some participants found it beneficial to have the mothers staying close to the NICU so that they were able to get more involved with their infants and increase the mothers' sense of empowerment. Despite many reporting being at under-resourced facilities, the majority stated that they could always use whatever they had available to carry out their intervention. Some partidpants did have KMC wraps and proper nesting equipment, whereas others used linen and towels.

The need to fulfil pre-determined professional roles was another intrinsic factor identified. Assessment to identify potential developmental delays and abnormalities was an important occupational therapy role, which concurs with findings in an earlier South African study7. According to Vergara et al.10, the NICU occupational therapist should be competent in both formal and informal assessments of neonates. Despite many formal assessment tools being used internationally in NICUs12, CSOTs mainly used informal observations. This could impact the comprehensiveness and reliability of assessments, as standardised tools guide more holistic, consistent, valid and reliable results.

Other essential roles included clinical and relational/ consultancy roles, which were similar to other studies7,10. Clinical roles included positioning and handling neonates, facilitating KMC, providing family support and modifying the environment, aligned with the findings of Müller et al. Many of the CSOTs advocated for a less stimulating environment. The environment is significant as it substitutes for the intra-uterine environment for a pre-term infant and plays a role in shaping the infant's developing central nervous system33. It is widely accepted that occupational therapists are involved with environmental adaptations, even in NICUs10. The participants mainly focused on auditory and visual adaptations, as constant bright lights and loud noises can be harmful to neonates and cause significant distress33. However, limited attention was paid to olfactory, gustatory, proprioceptive-vestibular, and tactile stimuli in this study10 which are also important sensory aspects that could impact neonatal stress.

The participants' educational efforts were directed predominantly at mothers or caregivers and towards increasing awareness of the role of occupational therapy with team members. The educational and advocacy roles of CSOTs in a NICU in this study differed from Müller et al.'s7study. The different findings were attributed to new graduate occupational therapists not having sufficient experience to deal with the resistance encountered.

Demands of Mastery

As the CSOTs moved towards mastery, specific demands were placed on them that were contextually dependent, creating an occupational challenge. Participants reported facing high patient loads and lack of adequate time to fulfil all duties, which negatively influenced service delivery in the NICU. This highlighted the need for on-the-job training and mentorship. The lack of privacy when dealing with mothers was unsuitable to building relationships. Establishing a trust relationship between the mother and the therapist is vital to ensure compliance with interventions. Lincare18 stated that counselling rooms and comfortable seating for mothers should be accessible in all units. However, many participants did not experience this at their facilities and recognised it as a necessity.

Family-centred intervention has become the gold standard for the healthcare of infants34, with greater parent responsiveness and warmth being correlated with improved developmental outcomes35. The occupational therapist's role in the NICU should be both infant- and parent-orientated12. The CSOTs aimed at forming strong relationships with the parents and focused on parent education and empowerment. This was especially important in the KZN setting, where the low maternal education levels, poverty, younger age of mothers and a language barrier were noted as hindrances to early childhood development programmes, in keeping with Clements and colleagues study36. Most of the participants reported that it was difficult to measure the success of their intervention in the NICU setting. Most of the participants measured their success by the frequency of follow-ups and measuring developmental milestones over the long-term, which proved difficult due to high turnover rates and poor compliance of parents. Despite many CSOTs providing developmental follow-ups at primary healthcare (PHC) clinics with the infant's primary caregiver, there was little other community engagement or education, correlating with another South African study37. This could be attributed to a lack of undergraduate training on relevant PHC services in infant health.

According to the HPCSA38, undergraduate training programmes in South Africa must equip health science students to fulfil the roles of a healthcare practitioner, communicator, collaborator, manager, leader and advocate, scholar, and professional. The participants agreed that occupational therapists require more than just knowledge in the field to work effectively in NICUs. In the KZN context, particular importance was placed on perseverance and creative problem-solving skills, needed for dealing with under-resourced facilities, a lack of undergraduate training and the lack of awareness of the occupational therapist's role in NICUs. This could be due to the poor understanding of the occupational therapist's role in the NICU within South Africa, as well as the limited policies in place to generate relevant protocols7.

Press for Mastery

The study found a press for mastery throughout the community service year, as the CSOTs developed their identity and competence and sought ways to cope with NICU practice. Initially, the CSOTs felt incompetent and ill-equipped in dealing with neonates. However, through exposure to NICU tasks, identity was built, which shaped the CSOTs' interactions in this environment. Many participants also felt that their work in NICU made them more holistic as therapists and felt they made a difference. A few of the participants believed that delivering services in the NICU increased their pride in the occupational therapy profession as they viewed their role as valuable. Therefore, the CSOTs' identity was built through personal motivators, social support, and feelings of productivity or success2l. The CSOTs felt an increased sense of identity when there was less overlap with physiotherapists. In contrast, poor understanding of the occupational therapist's role challenged their identity, concurring with Van Stormbroek and Buchanan's9 study.

Participants reported a lack of orientation to their new environment, which is required to improve feelings of confidence20. According to Hodgetts and colleagues29, it takes a therapist six months to two years to develop feelings of competence. Increased competence at the end of community service was evidenced when CSOTs needed less supervision, integrated their skills, applied learnt knowledge, and made dynamic changes in the environment, mainly through in-services.

The CSOTs sought methods to adapt to the NICU demands, including research using internet and textbook resources and contacting supervisors or mentors. Internet resources are commonly used to enhance professional development, especially in our technological advancing world39,40,41,42. They are beneficial to professionals needing to access information rapidly and cost-effectively, especially in rural areas40. This study found Google and YouTube were familiar internet sources used to obtain information, which correlates with previous studies39,41. Authenticity and accessibility of the online information are essential to consider as some information may be outdated, not evidence-based, or even irrelevant to the context40. This study highlighted the lack of permanent supervision for CSOTs, which correlated with Van Stormbroek and Buchanan's9 findings. External mentors are beneficial to CSOTs, who have no supervisors at their facility18. This is often the case in South Africa, where there is inadequate social, administrative, and clinical support for CSOTs20. Therefore, providing contact lists of experienced occupational therapists familiar with KZN NICUs, who have gained advanced skills in this area of practice, could be a more practical solution in this context.

Very few participants attended NICU-related courses as CSOTs. Nevertheless, those who did, stated this was invaluable for their clinical practice. Low attendance could be attributed to the poor availability of NICU-related courses in KZN, and limited finances. The most common course attended was the 'Little Steps: Neurodevelopmental Supportive Care of the Preterm Infant', similar to Müller et al.'s7 findings. The training recommendations reported in this study included provision of affordable NICU-related courses for CSOTs. Additionally, it was recommended that undergraduates are exposed to NICU indirectly, through practical videos or NICU-related projects, and sensitised to the negative effects of poor clinical practice with neonates.

CONCLUSIONS

The desire, demand and press for mastery by occupational therapists working in the field of neonates were highlighted in this study. Newly qualified CSOTs appear to be able to overcome the challenges of working in the NICU's highly technical environment, despite their lack of advanced knowledge, skills, and prior experience, by the end of their community service year. In this study, the participants' first negative visit to the NICU and their innate passion for paediatrics, were drivers towards their need to become more competent in the field. Personal characteristics such as emotional resilience, empathy and open communication were essential to work in NICUs. However, high patient loads and lack of adequate time to fulfil all duties negatively influenced service delivery in the NICU and highlighted the need for on-the-job training and mentorship as support. A focus on establishing a strong rapport with the parents and on parent education was noted, which resulted in enhanced compliance with intervention, especially given the young age and low education level of several mothers.

Occupational identity appeared to be established on personal motivators and feelings of productivity. A few of the participants believed that working in the NICU increased their pride in the occupational therapy profession as they felt their role was invaluable. The participants experienced an increased perception of competence by the end of community service. They believed they required less supervision, integrated their skills, applied learnt knowledge, and made active changes in the environment. The coping methods used to increase this sense of competency included conducting further research on unknown topics, consulting supervisors or mentors and attending NICU-related courses as CSOTs.

LIMITATIONS

Transferability is limited due to the study being conducted in the province of KZN with a small sample size. Although the training and experiences of an occupational therapist practicing in KZN may be applicable in various provinces in South Africa, the health system variances, including availability of resources and infrastructure, may also limit transferability. Findings are limited to the experiences of CSOTs between 2014 and 2017, with many participants from the same university, which could have biased the results. A response bias may have been created as occupational therapists with a negative attitude towards neonatal intensive care or who felt incompetent in this practice area may not have responded to the invitation to participate.

ROLE OF AUTHORS

Michaela Hardy was the primary investigator in this study and was responsible for study design, sourcing relevant literature, contacting, and interviewing participants, transcribing interviews, and data analysis. Pragashnie Govender and Deshini Naidoo were supervisors of the study who assisted in the conceptualisation and design of the study, data analysis and interpretation together with Michaela Hardy. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organisation [WHO]. Nurturing care for early childhood development, A framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. 2018. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/nurturing-care-early-childhood-development/en/ (16 September 2018). [ Links ]

2. Hoque M, Haaq S, Islam, R. Causes of neonatal admissions and deaths at a rural hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The South African Journal of Epidemiology and Infection. 2011: 26(1), 26-29. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10158782.2011.11441416 (15 July 2017). [ Links ]

3. Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Maternal and Child Health. 2017. http://www.health.gov.za/index.php/gf-tb-program/113-maternal-and-child-health (7 August 2017). [ Links ]

4. Askin DF Wilson D. In Wong's Nursing care of infants and children. Chapter 10, The High-Risk New-born and Family. 2011: 314-389. https://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/evolve/E2/book_pages/wongncic/docs/Hockenberry_Chapter10.pdf (15 July 2017). [ Links ]

5. Barbosa BM. Teamwork in the Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Paediatrics. 2013: 33(1): 5-26. http://www.rheapaul.com/Files/Teamwork%20in%20NICU.pdf (27 July 2017). [ Links ]

6. Hunter J, Lee A, Altimier L. Chapter 21, Neonatal Intensive Care Units. In Case-Smith J, O'Brien, JC. Occupational Therapy for Children and Adolescents. Seventh Edition. 2015: 595- 635. [ Links ]

7. Müller M, Myburgh A, Stock R. The Training and Role of Occupational Therapists in South African Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Unpublished manuscript. Submitted to the Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Therapeutic Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the Bachelor of Science (Occupational Therapy). 2016. [ Links ]

8. Dewire A, White D, Kanny E, Glass R. Education and Training of Occupational Therapists for Neonatal Intensive Care Units. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1996: 50(7): 486- 494. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8819600 (27 July 2017). [ Links ]

9. Van Stormbroek K, Buchanan H. Community Service Occupational Therapists: striving or just surviving?' South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016: 46(3): 63- 72. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2310-38332016000300011&lng=pt&nrm=iso (28 July 2017). [ Links ]

10. Vergara E, Anzalone M, Bigsby R, Gorga D, Holloway E, Hunter J. Specialized Knowledge and Skills for Occupational Therapy Practice in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006: 60, 659-668. http://ajot.aota.org/article.aspx?articleid=1870011 (15 July 2017). [ Links ]

11. Gauchan E, Basnet S, Koirala D P Rao K S. Clinical profile and outcome of babies admitted to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). Journal of Institute of Medicine. 2011: 33(2). http://jiom.com.np/index.php/jiom-journal/search/authors/view?firstName=Gauchan%20E%2C%20Bas-net%20S&middleName=&lastName=Koirala%20D%20P%2C%20Rao%20K%20S&affiliation=&country= (l5 July 2017). [ Links ]

12. Gorga D. The Evolution of Occupational Therapy practice for infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1994: 48 (6), 487-489. https://ajot.aota.org/article.aspx?articleid=1873289 (23 January 2018). [ Links ]

13. Lloyd L, De Witt W. Neonatal mortality in South Africa: How are we doing and can we do better? Editorial. South African Medical Journal. 2013: 103(8), 518-519. http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/view/7200/5281 (11 February 2019). [ Links ]

14. South African Speech-Language- Hearing Association [SASLHA]. Guidelines: Early Communication Intervention. Ethics and Standards Committee. 2011. https://www.mm3admin.co.za/documents/docmanager/55e836d5-3332-4452-bb05-9f12be8da9d8/00012503.pdf (15 July 2017). [ Links ]

15. Province of KwaZulu-Natal. Socio-economic Review and Outlook 2015/2016. 2016. http://www.kzntreasury.gov.za/Socio%20Economic/SERO_FINAL_4_March_2016.pdf (2 August 2017). [ Links ]

16. Dayal H. Provision of rehabilitation services within the District Health System-the experience of rehabilitation managers in facilitating this right for people with disabilities. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010: 40(1), 22-26. [ Links ]

17. Sutan R, Berkat S. Does cultural practice affect neonatal survival- a case control study among low birth weight babies in Aceh Province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014: 14(342). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25269390 (12 August 2018). [ Links ]

18. Lincare. Norms and Standards for Essential Neonatal Care. 2013. http://www.lincare.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Chapter-2-Norms-and-Standards-for-Essential-Newborn-Care.pdf (7 August 2017). [ Links ]

19. Nightlinger K. Developmentally Supportive Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: An Occupational Therapist's Role. Neonatal Network. 2011: 30(4), 243-248. https://search.proquest.com/openview/f9d328c01d69f31c5fb12306de53150a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cb1=646499 (11 February 2019). [ Links ]

20. Beyers B. Experiences of community service practitioners who are deployed at a Rural health facility in the Western Cape. Unpublished manuscript. A mini thesis submitted for the degree of Magister Curations at the School of Nursing, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape. 2013. http://etd.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11394/3321/Beyers_MCUR_2013.pdf?sequence=1 (28 July 2017). [ Links ]

21. Phelan SK, Kinsella EA. Occupational identity: Engaging socio-cultural perspectives. Journal of Occupational Science. 2009: 16(2), 85-91. file:///D:/Users/micst/Downloads/PhelanKinsella2009JOS.pdf (12 August 2018). [ Links ]

22. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care. 2007 Dec 1;19(6):349-57. [ Links ]

23. Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage publications; 2014 Oct 29. [ Links ]

24. Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation: Theory and application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [ Links ]

25. Schkade JK, Schultz S. Occupational adaptation: Toward a holistic approach for contemporary practice, part l. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1992 Sep 1;46(9):829-37. [ Links ]

26. Schultz S, Schkade JK. Occupational adaptation: Toward a holistic approach for contemporary practice, part 2. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1992 Oct 1;46(10):917-25. [ Links ]

27. Dunn W, Brown C, McGuigan A. The ecology of human performance: A framework for considering the effect of context. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1994 Jul 1;48(7):595-607. [ Links ]

28. Clarke V Braun V Hayfield N. Thematic analysis. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. 2015 Jan 1:222-48. [ Links ]

29. Hodgetts S, Hollis V,Triska O, Dennis S, Madill H, Taylor E. Occupational therapy students' and graduates' satisfaction with professional education and preparedness for practice. The Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sandra_Hodgetts/publication/6221920_Occupational_Therapy_Students%27_and_Graduates%27_Satisfaction_with_Professional_Education_and_Preparedness_for_Practice/links/58f7a3b94585158d8a6c17d5/Occupational-Therapy-Students-and-Graduates-satisfaction-with-Professional-Education-and-Preparedness-for-Practice.pdf?origin=publication_detail (19 October 2018). [ Links ]

30. Eraut M. How Professionals Learn through Work. University of Surrey. 2008. http://surreyprofessionaltraining.pbworks.com/f/How+Professionals+Learn+through+Work.pdf (1 November 2018). [ Links ]

31. Schultz S. Theory of Occupational Adaptation. In Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Schell BA. Willard's & Spackman's Occupational Therapy. 11th Edition. Philadelphia. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009. [ Links ]

32. Forsyth K, Kielhofner G. Model of Human Occupation. Ergoterapeuten. 2008. https://www.noexperiencenecesarybook.com/oQEb2/the-article-presents-a-current-overview-of-the-ergoterapeuten.html (12 October 2017). [ Links ]

33. Aucott S, Donohue PK, Atkins E, Allen MC. Neurodevelopmental care in the NICU. MRDD Research Reviews. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. 2002. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b04e/579976367540682cc580230f3075244784db.pdf (7 February 2018). [ Links ]

34. King G, Strachan D, Tucker M, Duwyn B, Desserud S, Shillington M. The Application of a Transdisciplinary Model for Early Intervention Services. Infants and Children. Wolters Kluwer Health. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009. https://depts.washington.edu/isei/iyc/22.3_King.pdf (4 November 2018). [ Links ]

35. Hadders-Algra M. Challenges and limitations in early intervention. Developmental medicine and child neurology. Netherlands, 2011. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04064.x/pdf (15 July 2017). [ Links ]

36. Clements KM, Barfield WD, Kotelchuck M, Wilber M. Maternal Socio-Economic and Race/Ethnic Characteristics Associated with Early Intervention Participation. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18026825 (29 September 2018). [ Links ]

37. Naidoo D, Van Wyk J, Joubert RW. Exploring the occupational therapist's role in primary health care: Listening to voices of stake-holders. African Journal of Primary Health Care Family Medicine. 2016: 8(1). http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/phcfm/v8n1/30.pdf (4 November 2018). [ Links ]

38. Health Professions Council of South Africa [HPCSA]. Core competencies for undergraduate students in clinical associate, dentistry and medical teaching and learning programmes in South Africa. 2014. http://www.hpcsa.co.za/uploads/editor/UserFiles/downloads/medical_dental/MDB%20Core%20Competencies%20-%20ENGLISH%20-%20FINAL%202014.pdf (29 September 2018). [ Links ]

39. MacWalter G, McKay J, Bowie P. Utilisation of internet resources for continuing professional development: a cross-sectional survey of general practitioners in Scotland. BMC Medical Education. 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4721189/pdf/12909_2016_Article_540.pdf (21 October 2018). [ Links ]

40. Herrington AJ, Herrington JA. Using the internet for professional development: the experience of rural and remote professionals. University of Wollongong. Australia. 2006. https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.co.za/&httpsredir=1&article=1911&context=edupapers (21 October 2018). [ Links ]

41. Govender P Mostert K. Making sense of knowing: Knowledge creation and translation in student occupational therapy practitioners. African Journal of Health Professions Education. 2019;11(2):38-40. [ Links ]

42. Naidoo D, Govender P Stead M, Mohangi U, Zulu F Mbele M. Occupational therapy students' use of social media for professional practice. African Journal of Health Professions Education. 2018;10(2):101-5. [ Links ]

* Corresponding Author: Michaela Hardy. Email: michardy22@gmail.com