Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.50 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2020

POSITION STATEMENT

Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa position paper on vocational rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

Goal 8 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aims ''to promote sustained and inclusive economic growth, full and productive growth and decent work for all'1:21 Thus, work is an important occupation for adult humans2. However, the ability to do so can be affected by injury, illness, impairment or congenital or acquired disability3.

Vocational rehabilitation is a multi-professional evidence-informed approach that is provided in different settings, services and activities to working age individuals with health-related impairments, limitations, or restrictions with work functioning, and where the primary aim is to optimise work participation4 at the different phases of an individual's work cycle.

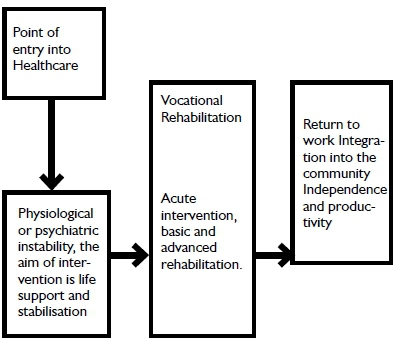

Within this field of rehabilitation the occupational therapist is an established and recognised role player5. The occupational therapy profession recognises the occupation of work as an important occupation in an adults life6, an essential contributor to the individuals socio-economic well-being, as an integral part of their treatment process and as the planned outcome of rehabilitation7. The vocational rehabilitation process consists of a set of steps, which in theory, follow consecutively but in practice may not be as neatly packaged, as the needs of each individual client are unique. The steps include : Prevention, Screening, Assessment and Evaluation, Intervention, Placement, Follow-up8. The following diagram shows the integration of vocational rehabilitation into the larger scope of occupational therapy.

STATEMENT OF POSITION

Vocational rehabilitation in the public sector South Africa is fragmented between the Departments of Health, Transport, Labour, Correctional Services, Social Welfare and Basic Education. Legislation indicates that vocational rehabilitation should be located with the Department of Labour18. Vocational assessments - and to a lesser extent rehabilitation - is provided in the private sector and funded by insurance and commercial enterprises.

Occupational therapists providing vocational rehabilitation can be found in all sectors but at present they are predominantly employed in either the healthcare sector, which is often the first port of call for injured or sick workers19, or in schools for learners with special educational needs to provide transition services for learners from school into the world of work.

Within a healthcare facility, be it private or public, occupational therapists are usually the team members that identify and promote the need to address, from the onset of intervention, the work associated aspect of a healthcare user as part of the holistic management of their condition20. Early intervention is also an important indicator for successful return to work21.

Until the Department of Labour employs enough occupational therapists and rolls out extensive vocational rehabilitation service centres, the status quo will remain. Occupational therapists can, and do, offer valuable contributions within skills training, sheltered and protected workshops and the entrepreneurial field. To ensure effective vocational rehabilitation services for all, an inter-sectorial approach22 with transparent collaboration is a requirement for all stakeholders if the SDG are to become a reality for people with disabilities and reduce their reliance on social welfare support.

It is important to establish a unified 'language' and consolidate the current assorted terminology when discussing the human occupation of work. OTASA recommends that occupational therapists comply with the terminology as established at an international consensus congress of experts chosen by WHO23. A unified understanding of the steps in the vocational rehabilitation process (Prevention, Screening, Assessment and Evaluation, Intervention, Placement, Follow-up) is also important.

Prevention is a professional educative service for the prevention of injury and maintenance of physical and mental health and well-being at work, as well as creating an awareness of good work practice, averting the development and/or exacerbation of pathology24. Such services could include back-programmes and spinal care education, ergonomics, stress management, energy conservation and the teaching of precautionary measures related to joint care and spinal hygiene.

Screening of general or specific work related skills is a short prescriptive process used to filter and effectively refer patients to more experienced therapists, specialised services or facilities and supports efficient service delivery25.

Assessment and evaluation services involve the assessment of the ability of a person, who has an injury or illnesses, to be able to work26 or do vocational tasks27. Such services would include workplace assessment, functional capacity evaluations, medico legal assessments, pre-placement screening and disability determination.

Intervention services are programmes aimed at correcting, adapting or compensating for ability to work deficits28. There are various intervention programmes, which can be offered to correct work deficits or improve work performance. These are important for the successful and sustainable placement into the open labour market or sheltered and protected work environments. Examples of such services could be job modification, case management, pain management, work trials, work hardening, work preparation or readiness, work visits, work guidance, work-place accommodation, work adaptation, job seekers groups, entrepreneurial and self-employment initiatives, support groups and other return to work efforts.

Placement services are efforts aimed at the actual work site and are focused on return to- or starting to work29. It involves the returning of clients to their own, alternative or new work in the open labour market, starting an entrepreneurial enterprise or going to sheltered or protected workshops. Work site visits would be essential and could include services such as job analysis, accessibility, ergonomic audits and advice to managers and employers. Additional placement services would be vocational guidance and counselling, outpatient support groups, job acquainting, adaptation and accommodation efforts and the redesigning of architectural barriers. It could also entail assistance with starting up or continuing of self-employment or other forms of entrepreneurial endeavours. For those not able to meet open labour market requirements, placement in sheltered or protected workshop could be explored.

Follow-up is done for all occupational therapy clients who used vocational rehabilitation services30. This could be with employers, referral sources, family members and the clients themselves, and could be done telephonically, electronically or during physical work visits. The follow-up of users of the vocational rehabilitation services demonstrates the occupational therapist's commitment to a case and serves to conclude a comprehensive service. This service is fundamental to a sustainable and successful outcome in the context of case management.

Screening, follow-up and some of the intervention services may be offered by newly qualified occupational therapists, with no special skills or knowledge, but who have been orientated to the relevant standard clinical protocols. No tools, equipment or venues other than what is available in a generic and basic occupational therapy department are required. Such services could be offered as regular programmes or as the need arises and could require work site and resource visits.

Prevention, assessment, placement and some of the intervention services need to be offered by occupational therapists with experience of a wide variety of pathologies, good clinical reasoning skills and additional knowledge and clinical competencies vocational rehabilitation and the labour market. The use of standardised assessment tools and activities within a designated work area, work site visits and resource visits would be necessary. Buys30 established a comprehensive list of competencies such therapists need.

In South Africa, the Medico legal work14 and Driving Rehabilitation31 fields are closely associated with vocational rehabilitation but applied knowledge and advanced clinical competencies. These fields are separate autonomous fields of practice and should not be superimposed onto vocational rehabilitation.

CONCLUSION

OTASA believes that the occupational therapist's role in vocational rehabilitation is justified by their knowledge of development, pathology, injury, illness, impairment and/or disability and their knowledge of the functional requirements of work. The occupational therapist in vocational rehabilitation in South Africa works within a multidis-ciplinary team in a multi-sectoral manner to respond to the needs of their clients32.

All occupational therapists can and should be able to offer basic vocational rehabilitation. Newly qualified occupational therapists have to be able to work independently at a basic level in a variety of vocational rehabilitation settings. Those vocational rehabilitation services that require competencies beyond a basic level need to be referred to therapists who have acquired, and can provide proof of the additional necessary competencies that provide competent, professional, contextually relevant vocational rehabilitation services to clients32. Post-graduate training should be available for therapists who wish to develop additional levels of competencies. Research in the field needs to generate contextually relevant evidence that has practical value to the field.

The primary aim of occupational therapy's vocational rehabilitation intervention needs to be relevant and of therapeutic value to the client so as to meet SDG9 as far as it is possible. The type of vocational rehabilitation service that occupational therapists in South Africa offer should be dictated by the vocational needs and aspirations, social structures and contextual realities33 of the clients they see.

AUTHORS:

• Hester van Biljon, B Occ Ther (UFS), M Occ Ther (UFS), PhD (Wits) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4433-6457; Private Practitioner at Work-Link Vocational Rehabilitation Practice and Post-doctoral Fellow Stellenbosch University

• Simon Rabothata, B Occ Ther UL (Medunsa), Post Grad Dip Voc Rehab UP https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9102-9893; Assistant Director, Therapeutic & Medical Support Services, Gauteng Health Department, Johannesburg

• P A de Witt, Nat Dip OT (Pretoria), MSc OT (Wits), PhD (Wits).https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3612-9020; Post-retirement Sessional Senior Lecturer, Occupational Therapy Department, University of Witwatersrand.

Date Ratified: Council 2019

REFERENCES

1. United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable evelopment. New York: United nations, 2015. [ Links ]

2. Kielhofner G, Braveman B, Baron K, Fisher G, Hammel J and Littleton M. The model of human occupation: understanding the worker who is injured or disabled. Work. 1999; 12: 37-45. [ Links ]

3. Cancelliere C, Donovan J, Stochkendahl MJ, et al. Factors affecting return to work after injury or illness: best evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Chiropractic & Manual Therapies. 2016; 24. [ Links ]

4. Escorpizo R, Finger ME, Glässel A and Cieza A. An international Expert Survey on Functioning in Vocational Rehabilitation Using the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health. Journal Occupational Rehabilitation. 2011; 21: 147-55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-010-9276-y [ Links ]

5. Ross J. Occupational Therapy and Vocational Rehabilitation. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons, 2007. [ Links ]

6. de Witt P The "Occupation" in Occupational Therapy -19th Vona du Toit memorial lecture.. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002; 32: 2-7. [ Links ]

7. Bade S and Eckert J. Occupational therapists' expertise in work rehabilitation and ergonomics. Work. 2008; 31: 1 - 3. [ Links ]

8. van Biljon H, Casteleijn D, du Toit S and Soulsby L. Opinions of Occupational Therapists on the Positioning of Vocational Rehabilitation Services in Gauteng Public Healthcare. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 1: 45-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n1a10 [ Links ]

9. du Toit V Patient Volition and Action in Occupational Therapy. Hillbrow: Vona & Marie du Toit Foundation; 1991. [ Links ]

10. Strasheim P and Buys T. Vocational rehabilitation under new constitutional, labour and equity legislation in a human rights culture. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1996; 26: 14-28. [ Links ]

11. van Biljon H. Occupational Therapy, the New Labour Relations Act and Vocational Evaluation: A Case Study. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1997; 27: 23-30. [ Links ]

12. van Biljon H. Transforming vocational rehabilitation in public healthcare. OTASA Congress: Harnessing the Changing Winds. Johannesburg; 2016. [ Links ]

13. Byrne L. The Current and Future Role of Occupational Therapists in the South African Group Life Insurance Industry. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2003; 33: 2-10. [ Links ]

14. van Biljon H. Occupational Therapists in Medico-Legal Work -South African Experiences and Opinions. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013; 43: 27-33. [ Links ]

15. van Biljon HM, du Toit SHJ, Masango JJ and Casteleijn D. Exploring service delivery in occupational therapy: The use of convergent interviewing. Work-A Journal of Prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation. 2017; 57: 221-32. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-172557 [ Links ]

16. Ramukumba TA. The 23rd Vona du Toit Memorial Lecture 2nd April 2014. Economic Occupations: The 'hidden key' to transformation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 45: 4-8. [ Links ]

17. Abasa E, Ramukumba TA, Lesunyane RA and Wong SKM. Globalization and Occupation: Perspectives from Japan, South Africa, and Hongkong. New Jersey: Pearson, 2010. [ Links ]

18. Office of the Deputy President and Mbeki TM. Integrated National Disability Strategy. In: Health Do, (ed.). Republic of South Africa1997: 81. [ Links ]

19. van Biljon HM, Casteleijn D, Du Toit SHJ and Rabothata S. An Action Research Approach to Profile an Occupational Therapy Vocational Rehabilitation Service in Public Healthcare. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 45: 40 - 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45n3/a8 [ Links ]

20. Soeker MS, Van Rensburg V and Travill A. Are rehabilitation programmes enabling clients to return to work? Return to work perspectives of individuals with mild to moderate brain injury in South Africa. Work: A Journal of Prevention, Assessment and Rehabilitation. 2012; 43: 171-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-1413 [ Links ]

21. Sheppard DM and Frost D. A new vocational rehabilitation service delivery model addressing long-term sickness absence. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 79. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0308022616648173 [ Links ]

22. Coetzee Z. Re-conceptualising vocational rehabilitation services towards an inter-sectoral model. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 41: 32 - 6. [ Links ]

23. Finger ME, Escorpizo R, Glässel A, et al. ICF Core Set for vocational rehabilitation: results of an international consensus conference. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2012; 34: 429 - 38. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.608145 [ Links ]

24. Pomaki G, Franche RL, Murray E, Khushrushahi N and Lampinen TM. Workplace-Based Work Disability Prevention Interventions for Workers with Common Mental Health Conditions: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2012; 22: 182 - 95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9338-9. [ Links ]

25. Vocational Rehabilitation Task Team. Occupational Therapy Vocational Ability Screening Tool. In: Health and Social Development, (ed.). Johannesburg: Gauteng Provinc;, 2013. [ Links ]

26. Buys T and van Biljon H. Occupational Therapy in Occupational Health and Safety: Dealing with Disability in the Work Place. Occupational Health. 1998; 4: 30-3. [ Links ]

27. Gibson L and Strong J. A conceptual framework of functional capacity evaluation for occupational therapy in work rehabilitation. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2001; 50: 64 - 71. https://doi.org/10.1046/jJ440-1630.2003.00323.30. [ Links ]

28. Sturesson M, Edlund C, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Falkdal AH and Ber-nspâng B. Work ability as obscure, complex and unique: Views of Swedish occupational therapists and physicians. Work. 2013; 48: 117 - 28. https://doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-1416. [ Links ]

29. Russo D and Innes E. An organizational case study of the case manager's role in a client's return-to-work programme in Australia. Occupational Therapy International. 2002; 9: 57-75. https://DOI10.1002/oti.156 [ Links ]

30. Buys T. Professional competencies in vocational rehabilitation: Results of a Delphi study. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 45: 48-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45n3/a9 [ Links ]

31. Davis ES, Stav WB, Womack J and Kannenberg K. Driving and community mobility. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 70. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.706S04 [ Links ]

32. Watson R. A population approach to transformation. London: Whurr Publishers, 2004. [ Links ]

33. Crouch R. Occupational Therapy in Psychiatry and Mental Health, 5th Edition. Wiley-Blackwell, 20l4: 480. [ Links ]