Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.50 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2020/vol50no3a4

ARTICLES

'The hand belongs to someone': a therapist perspective on patient compliance

Kirsty van Stormbroek

BSc (Occ Ther) MSc (Occ Ther) UCT. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4890-5063; Lecturer, Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Therapeutic Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Compliance is considered to be a central element of effective health systems. In terms of rehabilitation, both non-attendance and non-compliance ofpatients with hand injuries in South Africa have been reported. This study explored how occupational therapists practicing in the field of hand therapy, understand compliance and its perceived barriers and supports

METHODS: A qualitative descriptive research design was employed. Nine occupational therapists who routinely treat patients with have conditions were purposively sampled. In-depth interviews were conducted, transcribed and inductive thematic analysis undertaken

RESULTS: Therapists' understanding of compliance demonstrated elements of consensus and difference. Four themes captured participants' views of barriers and supports: compliance is enabled when a powerful collaboration exists between the client and the therapist. For this to be possible, the therapist needs to understand the life and times of an injured hand, co-constructing therapy on the foundation of understanding the patient as an occupational being. Powerful collaboration is further enabled by effective communication for collaboration, and lastly the characteristics of systems and services that work hold power to hinder or enhance compliance

CONCLUSION: Results suggest that collaborative co-authoring of the hand rehabilitation process is central to enabling compliance. Therapists require a robust understanding of the person they are treating and the complex context in which the person participates. Accessible communication, effective education and enabling systems and services are also vital. Furthermore, the way in which occupational therapists conceptualise compliance matters. Critical reflection is necessary to interrogate the philosophical assumptions that underpin the terminology that occupational therapists choose and how power is navigated in relationships with patients with hand injuries

Key words: Hand therapy, adherence, shared decision making, low to middle income country

INTRODUCTION

Compliance has been defined as 'active engagement in the rehabilitation process'1:18 and is critical to successful intervention. Although hand rehabilitation constitutes the focus of this article, compliance bares relevance to all areas of occupational therapy practice.

In South Africa, both non-attendance and non-compliance with rehabilitation programmes have been reported as being problematic2-4. A local trial that compared the outcomes of an early active motion and early passive motion protocol for flexor tendon injury, found no significant difference in outcomes3. Compliance was suggested as one of the factors that contributed to this unexpected result3. Another South African flexor tendon injury longitudinal observational study reported a 49.5% rate of follow-up of non-attendance. Patients who received a controlled active motion protocol achieved better results than patients who received passive motion protocols but outcomes for both protocols were markedly worse than those achieved internationally5. A number of factors were statistically related to these poor outcomes including a language barrier. The authors suggested that if a language barrier did not exist, patients would be able to more readily comply4, linking compliance to the achievement of outcomes.

If non-attendance and non-compliance substantially influence the outcomes of patients with hand injuries, then compliance warrants investigation. However, this is only justified if hand injuries constitute a sizable burden in South Africa. Hand injuries

are common worldwide6 and evidence suggests the same in South Africa given the high levels of interpersonal violence7, road accidents8 and work-related conditions9,10. Hand injuries often result in permanent disability, which is notable given South Africa's large manual labourer population11. Hand injuries influence patients' functioning in daily life11, their livelihood12 and by implication the South African economy that already supports more than one million South Africans through disability grants13. This highlights the importance of effective hand rehabilitation11. Patient compliance is critical to the success of rehabilitation1 and thus, by implication, the return of individuals to participation in daily life.

Much of the author's clinical experience occurred at a large public hand surgery unit. "Patient was not compliant" frequently explained unsuccessful intervention or justified patient ineligibility for intensive intervention. To the researcher, it felt that a figurative box labelled "non-compliant" became the depository for all the stories of obstinate patients or patients that the team did not understand or relate to due to differing beliefs, language barriers, and the pressures associated with one of the busiest outpatient clinics in the hospital. Within a context of scarce resources, health professionals are obligated to make ethical judgements on which patients should be awarded limited resources. Without adequate insight into context-specific 'non-compliance', decisions are at risk of being ill informed at best, and unethical at worst. This calls for developing an understanding of compliance from the perspective of both patient and service provider.

'Compliance' has intentionally been used within this study despite scholars alerting us to the concerning implications of the term14,15 and recommending 'adherence' as a more appropriate alternative16. However, 'compliance' is commonly used in the South African health care system which has a complex socio-political history17. Against this backdrop, this study set out to explore how occupational therapists routinely treating hand-injured patients understand patient compliance, what they perceive to be barriers to compliance, as well as aspects that support or strengthen patient compliance.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Literature on medical compliance is abundant. After a dearth of literature on compliance in hand therapy was reported in 200218, a number of texts have been published16,19-21. In an Australian study the views on compliance of patients with hand-injury and therapists was compared18. A significant difference in perception was noted for 24 items of the 33 items that measured patient and therapist's views on compliance (p<0.01, adjusted alpha rate). However, both groups tended to identify similar reasons for non-compliance with the difference largely lying in therapists' belief that these reasons occurred more frequently. Both groups believed that compliance with home programmes was largely influenced by a lack of time, patients' resentment of the programme and pain experienced through doing the programme. Compliance with appointments was thought to be due to organisational factors including transport, daily routines and responsibilities.

Various internal and external factors have been reported to influence patient compliance1,16. Groth and Wulf1 reviewed factors in the literature that had been correlated to compliance and categorised them as internal or external. The latter category included time between referral and appointment, waiting time at the appointment, the relationship between doctor and therapist, the duration of rehabilitation, the presence of a local and cohesive family, financial resources, work situation, clinic accessibility, transportation and patient literacy. In South Africa, a few studies have indicated that external factors tend to have an influence on hand rehabilitation22,23 and rehabilitation in general24. These factors include inaccessible health care facilities, costly transport, language discordance, and attitudes of health care professionals.

Internal factors as defined by Groth and Wulf1 are "related to the patient's belief system"1:19. Drawing from the Health Belief Model25, internal components described by the authors included injury severity and the perceived risk of losing hand function, perceived rehabilitation efficacy and its cost benefit ratio, self-efficacy, and the relationship between patient and health professional1.

The distinction between internal and external factors, however, may not always be that clear. An alternative conceptualisation of factors affecting compliance is the World Health Organisation [WHO]'s Multidimensional Adherence Model (MAM)16,26. This model is considered to be appropriate for application to hand rehabilitation compliance16. It comprises five dimensions or categories that influence compliance to long term therapies26, but importantly acknowledges that these dimensions interact with one another. These dimensions are health care team and system factors, social and economic factors, therapy related factors, patient-related factors and condition-related factors26.

The MAM assists us in understanding the factors that influence the compliance of patients with hand injuries, but also provides a framework for thinking about strategies to support or enable compliance. In a guest editorial for the Journal of Hand Therapy, O'Brien16 provided a narrative review on improving compliance to hand rehabilitation and described the evidence according to the five MAM dimensions. Health care team and health system related interventions were reported by O'Brien to be an understudied aspect of compliance within hand therapy. However, low level evidence for the importance of trust and effective communication (between patient and provider) has been reported in the literature of the discipline16. The importance of these factors to compliance has also been reported in medical literature27 and trust emerged as theme in a more recent hand rehabilitation qualitative study28. Continuity of care (including consistent communication from the multi-disciplinary team), supporting patient self-efficacy, and incorporating patients' needs and viewpoints from the start of the therapy process were also cited as strategies to optimise compliance in hand therapy16 .

Despite a relationship between social and economic factors and compliance being reported as it relates to medication compliance29, this association has yet to be consistently established within the hand therapy literature16,30. Although evidence is yet to confirm this, there is an assumption that for some patients with hand injuries, compliance is impacted by family support, access to services, and treatment costs16. Local anecdotal evidence would confirm this and further qualitative evidence has highlighted the impact of treatment costs28 and employment status31 on compliance to hand rehabilitation. However, further evidence needs to be generated in this area. Available evidence for social and economic interventions in hand rehabilitation included strengthening patient skill in self-management and developing capacity of health workers already in the patients' communities16.

Therapy-related factors included the use of meaningful activity in intervention, splints that are comfortable and look acceptable, and strategies for the management of pain16. Local evidence suggests that the absence of a language barrier in hand rehabilitation supports compliance5, implying the need for use of South African languages (or appropriate alternatives) that are accessible to patients32.

Evidence for patient-related interventions16 are largely related to supporting patients' sense of agency and hope in the recovery process, and therapist skill development in behavioural interventions16. Clinicians have also recently expressed the need for patient differences and temperaments33 as well as their hobbies and lifestyles to be taken into account when attempting to support compliance31.

Finally, condition-related factors included therapists identifying and managing psychosocial co-morbidities, therapists facilitating appropriate expectations of prognosis and rate of recovery, as well as the rationale for each intervention28. The importance of addressing patient expectations has been reiterated in a qualitative study that reported "patients expecting the treating therapists to be an expert and fix their problem"28:1262.

The literature demonstrates that evidence on compliance is abundant and that evidence within the hand rehabilitation literature is growing. Various categorisations have been suggested to assist in understanding the factors that impact on compliance and strategies to strengthen it. Although South African studies have linked poor hand rehabilitation outcomes to compliance, no studies on hand rehabilitation compliance in low-to-middle income countries (LMICs) could be found.

METHODS

Design:

A qualitative descriptive research design34 was employed.

Participant selection:

Nine occupational therapists who routinely treat patients with hand injuries were purposively sampled. Given the diversity that characterises South Africa35, attempts were made to diversify the sample through maximum variation sampling and to select information-rich sources from two urban and two rural provinces ("provinces where more than half of the population is rural"36:9). The South African Society of Hand Therapists' website was used to obtain therapist contact details. An invitation to participate was also sent to rural therapists via Rural Rehabilitation South Africa. A rural-based occupational therapist known to the researcher and a hand rehabilitation expert were asked to recommend potential participants. A therapist known to the researcher, who obtained a postgraduate diploma in hand therapy while working rurally, was invited to participate. Two rural participants spontaneously referred the researcher to other potential participants who they felt were information-rich and thus aspects of snowball sampling were included.

Data collection, management and analysis

The author conducted in-depth interviews with each participant. Interviews lasted between 25 and 62 minutes each and were held at participants' places of work, or an alternative convenient location where this was not suitable. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and checked for transcription accuracy. Inductive thematic analysis37 was conducted using MAXQDA 1236 software38 with the research objectives guiding inductive analysis. As patterns emerged that spoke to the objectives, codes were named37 and related codes clustered into sub-categories. Conceptually related sub-categories37 were organised into categories and these distilled into themes. The interrelation of themes was considered and the meaning of themes interpreted39. Data that related to how therapists understood the term 'compliance' lacked qualitative depth, thus quantitative content analysis was employed with text being sorted into categories and the frequencies of these categories being recorded37.

Trustworthiness

A number of strategies were used to pursue rigor. Prior to data collection, the author pursued reflexivity by reflecting on her assumptions and perspectives around compliance in a journal. This made the author aware of a potential tendency to probe views that resonated with her own. The author opted to adopt a neutral tone in interviews, attempting to intentionally explore all perspectives. Despite these strategies, it is acknowledged that neutrality is not possible and that the author's views unavoidably affect data interpretation37.

Credibility was strengthened through member checking40. All participants were sent a podcast of the preliminary findings. Three participants responded stating their satisfaction. A fourth participant had difficulty accessing the podcast but attended a separate presentation of the preliminary findings and accepted the findings as the author presented them.

Analysis was exposed to peer examination40. An academic colleague coded one interview. The coding schedule developed by the colleague was compared to the one generated by the author. These were discussed and extensive similarity was noted. Furthermore, codes, sub-categories, categories and themes were presented to the colleague confirming that the analysis had generated credible data. Minor recommendations were made. Feedback on the inter-relationship between themes was integrated and the name of one of the themes was adjusted.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (M170841). Informed consent was obtained from each participant. To maintain confidentiality only the researcher had access to participant names and data were stored on the author's password protected computer. Given that the occupational therapy profession is small and limited in diversity, providing demographic detail can compromise anonymity. For this reason, the names of provinces where data was collected was omitted. Participants were given gender-neutral pseudonyms so that they remained anonymous when quoted.

RESULTS

Demographic information

The average age of participants was 29.78 years (Range 24-36). Eight participants were female and one participant male. The home language of participants was sePulana (n=1), Afrikaans (n=4) and English (n=4). Two therapists worked in the private sector. The seven participants that worked in the public sector worked at varying levels of care including primary (n=1), district (n=2), provincial (n=1) and tertiary (n = 3). Five participants worked in rural provinces and four were based in urban provinces. Therapists had a median of 4 years and 11 months of hand rehabilitation experience (range 22-178 months). Four participants had completed a postgraduate qualification in hand rehabilitation with one other therapist in the process of completion.

Participants' understanding of the term 'compliance'

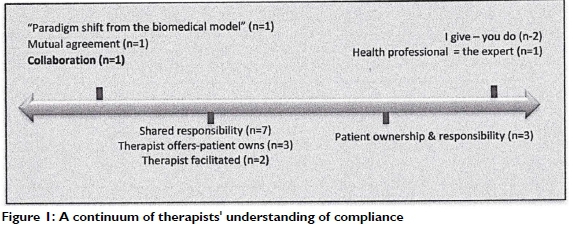

A majority of the participants n= 8 (89%) stated that compliance was about 'adhering to appointments and treatment'. Beyond this, participants' descriptions of compliance clustered on a continuum (Figure 1).

On the far right a stance was described where the health professional is the expert and I (therapist) give and you (patient) do. Moving centrally, therapists spoke about compliance being about patients taking ownership and responsibility. Most positioned their own views further left describing compliance as a shared responsibility where the therapist facilitates the therapeutic process or offers therapeutic direction which the patient owns. One therapist, illustrated on the far left, described her paradigm shift from the medical model. According to the therapist, compliance is about mutual agreement (n=1), a co-authoring process between patient and therapist, which is ultimately perceived as a collaboration (n=1).

Compliance: barriers and supports

Coded data that spoke to the barriers to and supports for patient compliance were distilled into categories, subcategories and ultimately four themes (Figure 2).

Powerful Collaboration

The first theme captured the therapists' views that compliance is supported or enabled when hand rehabilitation is a collaborative process between client and therapist. Shared power and collaboration highlighted an understanding of patients as disempowered service users, having unequal power to health professionals:

This community is ... so disempowered, they almost don't think that they can ask for better or... more or ... allowed to say, 'Listen, what you've given me is not right'...Participant 5

The participant perceived that patients' experiences of having limited power and autonomy in their communities, could affect therapy and compliance. Their experience in their community may limit their ability to express themselves and their preferences in therapy, potentially restricting the tailoring of therapy to their needs, and thus hindering compliance.

Participant 5 further made a link between patients' ability to 'speak up' in their community and 'speak up' in therapy:

I think a lot of the ladies in this community ...they are not allowed to speak up ... to stand up for themselves and it is often, 'You are nothing, we are everything'. * Men are everything, the ladies are not...they often get hushed and shushed and... it... just...plays over into all areas in life where they just feel like they are worth nothing and they are not receiving what we may be used to in other areas.I am struggling to get the message across. but it is maybe like an underlying aspect of them not verbalising or speaking up, they are ... from a young age being (told), 'Don't speak. You are not allowed to speak. Participant 5.

In addition to the restricted patient power described above, participants seemed to suggest that the dominance of the medical model might further hinder patient autonomy and choice. As a result, patients may submit or defer responsibility to the health professional. Participant 3 described a situation in which patients appeared to take very little ownership for their hand injury and unquestioningly accept whatever course of action was recommended by the health professional:

...It's not working, this thing (their hand) is broken.' And I'm (therapist) like, 'This thing is your hand!' And then whatever surgery or treatment is then prescribed is then, 'Yes and amen. Yes, doctor' or, 'yes' whatever I (therapist) say. Participant 3

Findings suggested the idea that health professionals who assume authoritarian positions over their patients may augment restricted patient ownership, emphasising the need for therapists to share power with their patients. Potentially as a means to achieving this, participants described the value of formally documenting patient's understanding, obtaining informed consent, effectively communicating the diagnosis, therapist role, goals of therapy, and the expected recovery and rehabilitation process. Participants mentioned the importance of therapists' reasoning being transparent and facilitating clients' choice and decision-making. This could enable clients' goals to direct therapy, and allow for collaborative problem solving.

Authentic client-centred services were perceived to support the powerful collaboration that supports compliance. Highlighting key elements of the therapeutic relationship, participants felt that building trust, rapport and respect with clients, as well as demonstrating authentic interest and care were essential:

Trust falls into buy-in to therapy... if they trust that you know what you are doing, that you are there for them.. .sometimes they feel that you are distant.just here for a pay-cheque.not actually here to listen to them or to understand what they're going through. Participant 2

Additional features of authentic client-centred services emphasised by therapists included 'being present' and listening actively, demonstrating cultural sensitivity and humility41, and using an approach that affirms clients' dignity, value and worth.

A potential barrier to compliance that was highlighted was conflicting belief systems between the health professional and patient. By implication, navigating this difference in a client-centred manner would be important to support compliance:

We live in...a very diverse country...some people.. believe.. .take it to religion ...they might say, 'I will pray about this and then I should be fine after that'... Maybe they'll go to church, to their pastor...They might go to see a traditional healer, because it also depends on what they think caused the problem. Even if to you (therapist), 'You had an injury because something heavy fell on your arm'... then they will tell you, 'No there is somebody behind the scene, there is witchcraft going on . I have been doing this (job) for so many years, it didn't happen so I believe so and so did this', so . they will seek the help in response to what they believe the cause is. Participant 1

Some felt that compliance could be predicted whilst others found it unpredictable and needed to be tested. Allowing clients to prove compliance and an approach that grades intervention sensitively to clients' responses was believed to be important. Grading goals from simple to more complicated, was highlighted while one participant conversely felt that prescribing numerous exercises meant that patients would at least remember some.

Function-focused therapy was believed to be important to building a collaborative treatment partnership and promoting compliance:

What I tend to do is (even) in our first session already I ask them very specific things... 'What are your responsibilities at home?', 'Doyou need to wash the dishes sometimes?...mop?.. fold clothes?' ... At work do you need to lift heavy things... push and pull ...or only...press buttons?' ...These are the type of things that we need to get you back to? Participant 7

Combining the medical model and client-centred practice was also thought to be important where protocols and approaches were tailored and sound clinical reasoning rather than 'recipes' used:

The problem with the medical model is 'you do what I say and I'm telling you this is right'... the patient doesn't matter because they fit in the model...Once you've shown them that you can bring therapy into their context, 'Okay, I see you for who you are therefore I'm willing...I'm going to adapt my explanation, my treatment slightly to you... So you don't travel, can you do this? Can we do it at that time...?'... so I'm adapting, (thepatient) sees I'm trying to fit it into his life. Participant 3

The life and times of an injured hand

The second theme that emerged suggested that collaboration is enabled, and compliance supported, when therapists do not only understand the hand injury, but also understand the person that they are treating. This involves developing a robust and holistic understanding of their client, the life that they lead in a multi-dimensional context and what a hand-injury means to them within the context of their lives:

... The hand belongs to someone so we try not to only focus on the hand but ... treat holistically. We obviously have boundaries ... but we do try ... get the story behind the story. identify what are the other factors that actually play a role in this. Participant 7

Your hand is your life. Participant 1

Participants identified various factors that they considered to influence compliance and are described in four categories. Firstly, participants explained that clients' have personal factors that positively or negatively affect compliance including personality, drive, determination and creative ability. Some patients were believed to have an extrinsic locus of control, failing to take responsibility and believing that 'the health professional will fix it'. Participants frequently highlighted the role that motivation played. Some patients reportedly demonstrate extreme motivation, waking up very early and walking long distances to get to treatment. If patients have family that they need to support this may strongly motivate their participation. However, participants perceived that motivation for rehabilitation might be poor when injuries are severe, and rehabilitation lengthy. Motivation to comply with therapy may also be hindered when patients judge a more impaired hand with a disability grant as being preferable to a slightly more functional hand. Participants also believed that substance abuse was frequently impaired compliance.

Beyond an appreciation of personal factors, participants believed that compliance is supported when therapists understand their patients' life and context. This speaks to understanding the context in which the patient lives, allowing patients to speak and be understood, and taking an accurate history and thorough assessment. Participants also mentioned the importance of addressing the psychosocial components of the injury and understanding the impact of the injury on patients' function. In addition, participants highlighted the need to understand patients' goals, concerns and expectations. Understanding what motivates patients, appreciating their narratives and being aware of their beliefs and roles was also perceived by participants to be needed to support their compliance.

Participants felt that it was necessary to understand the 'bigger scheme of patients' lives' and appreciate that 'life happens' and patients are compelled to fulfil roles and responsibilities, potentially to the detriment of their hand:

In the big scheme of their lives how important is it for them to come to... hand therapy, to do their hand therapy when they have to feed their child who're starving? When they have to protect their home because they live in a... dangerous environment when they...have to walk how far to get water? . in the greater scheme of their lives, how important is it for them to sit every two hours and do their blocking exercises? Participant 9

Participants also felt it necessary to understanding the extreme hopelessness that some patients experience. For some patients, therapy may make no difference to their stricken circumstances and future prospects, and this reality may thus hinder compliance.

Participants considered support to be key to compliance. Patients with family support were thought to fare better with therapists being considered wise to harness this support. Supportive and involved employers were believed by participants to enable compliance, while poor working conditions and the loss of wage or employment hampered it. Encouragement and support of fellow patients was also considered to be instrumental to compliance.

Finally, participants appeared to highlight the importance of therapists understanding the impact of a fractured society on patients' compliance. Violence, bad weather, long distances to facilities, transport difficulties and severely restricted patient resources all hindered compliance. Participants explained:

The infrastructure isn't great ... like rain ... if (patients) used to walk ... because of the rain and floods ... the bridges are like this ...they cannot cross over the river". Participant 1

At my other primary health clinics . I have a higher compliance rate than here. Purely I think it's easier to get to the clinic and the violence is less. Participant 2

Therapists believed that health system and service limitations affect compliance, including conflicting appointments, waiting times, poor hospital resources, late or lost referral, delayed surgery and an absence of therapists at primary level facilities:

We need therapists at every single clinic... we only have permanent therapists at four clinics. And those therapists have to go to other clinics ...it's a huge problem...we need ... a wider spread of our services so that patients don't have to travel far to get to us. Participant 9

Patients may also have had previous negative experiences with the health care system, or may have negative perceptions related to the experiences of others:

I think they see it as people go to (the hospital) to die. And it's true, a lot of people do come and then die... they don't wanna come because they feel like they're gonna go have an operation and die, cause their friend has died. from an operation... Participant 6

Within the fractured system, participants identified barriers that restricted health professionals from providing quality services, including high workloads and time constraints:

When I was working in a very busy government hospital, you lost the kind of empathy. we were passionate, but sometimes the patients didn't see it. Because you had 10 minutes and you just had to get it done and half of the time you forget to even introduce yourself. Participant 4

Furthermore, the state disability grant may hinder compliance to rehabilitation as it offers hope of financial resource within a society burdened by systemic poverty, even if this is at the expense of a functional hand:

A big number of the community live(s) off... child support and disability grants. There's very little employment in this area... Unfortunately.. .patients come in and say they had an injury, their hand can't work, they want a disability grant. Then as a therapist we find it very frustrating to put our bias...our frustration aside and say 'ok I understand ... that you are also desperate and you won't be able to find a job because there aren't any but also your hand isn't... you need to do your job'...When that comes into play we often see them .not really motivated in therapy because 'If I am going to do what you tell you me, my hand is going to get better and then I won't qualify for disability grant'... Participant 5

This therapist went on to share a perspective on the challenges of practicing within a system that contends with complex social and economic problems of a fractured society:

So it's kind of (a) messed up system but we ... understand why they are so desperate and they often would embrace an injury because if it means.they can actually support the family. Participant 5

Communication for collaboration

The third theme deals with the centrality of communication in promoting collaboration that facilitates compliance. Participants considered accessible and effective communication to be essential however, various barriers to this were identified. Participants highlighted the difficulty of communicating concepts that patients cannot relate to, linking this to language barriers, translation limitations and therapists making assumptions about what the client knows. Therapists require skill for communicating and explaining rehabilitation concepts in understandable ways. Use of the patients' first language is ideal and translation considered a second-best option. Testing patients' understanding was deemed necessary and illustrations to assist communication were considered helpful.

Patients are struggling to understand therapy.the older generation...they have never been to school, they don't understand the concept... never been exposed to the thing of, 'I give you information, you listen to that information and now you need to remember this information and apply what I tell you'...I found a benefit in actually drawing out my programmes with them, drawing little pictures because otherwise they just don't remember the exercise. Participant 5

Secondly, education for understanding and realistic expectations captured the view that communication is only successful when patients understand and have realistic expectations of the rehabilitation process:

I will find that patients think, 'Okay I'll have this operation and it will all be fixed'. (They) don't realise that that's not the case. 'You will have the operation which will allow for healing to occur but we need to facilitate return to function. We need to facilitate that healing'. And, and that takes time. Rehab takes time and that's what I try to explain." Participant 9

Restricted patient insight was perceived to be a barrier as well as limited understanding linked to patients' intellectual or educational limitations, or the unfamiliarity of the occupational therapy role. Participants believed that patients should understand the consequences of non-compliance, with fear sometimes being used by therapists to facilitate this. Providing education for understanding spoke to patients developing insight into the impact of their hand injury on their function, education on the role of the occupational therapist, using activity to assist patient understanding, education of the family, and essentially "going the extra mile" until patients understand.

Systems and services that work

The last theme covers participants' perception that services and systems affect patients' compliance in hand rehabilitation. Firstly, participants believed that patient compliance was supported by competent care. This implies that therapists should instil confidence and should be able to demonstrate positive outcomes to their patients:

If you seem confident in what you are doing ... if one of the (junior therapists) are in the same room as I am, they ask me questions...the patient turns to me... so, if you don't seem like 'I'm not sure', that also influence(s) the patient in feeling ... confident. Participant 8

Secondly, participants shared that compliance is supported by a dynamic multidisciplinary team (MDT) that co-ordinates responsibilities, communicates effectively and whose members all tell the patient the same thing. Potential hindrances identified by participants included inconsistency between team members and a lack of clarity around MDT roles. Additional hindrances were related to hierarchy within the MDT and patients attributing excessive weight to health professionals' words:

Patients.. put a lot of power into what the doctor's saying... they have a lot of power and I (therapist) don't... I feel that they will listen. to what the doctor has to say sometimes more than what we have to say even though perhaps .we show them evidence. So, I would say to her, 'Okay you say that your hand's not getting better but have a look here.. where you were before and where you are now. Would you still say that your hand's...not getting better?' And she said, 'No because the doctor said so'. Participant 9

This quote demonstrated the power of the doctor's words but also, within the context of the interview, showed how the patient used the doctor's words to justify her application for a disability grant.

Although the disability grant could impede patients' compliance, the final category systems and services captured the view that temporary grants that support the client during the rehabilitation process could enhance compliance. However, this enabler is not unaffected by inefficiency within the system:

With most cases they want the disability grant because they feel that they can't work while ...going through the rehab process... that's fair. But many of them...after they've gone through that whole (application) process. they are at a functional level. Participant 9

Other factors that were considered to enhance compliance included minimising time waiting for medical folders, seeing the doctor and therapist on the same day at similar times, text-message appointment reminder systems, hospital transport, clinic outreaches and successful referral pathways.

DISCUSSION WITH IMPLICATIONS

Participant demographics

Participants were purposively sampled and attempts were made to obtain a variety of perspectives by seeking diversity in age, gender, home language, province (broadly categorised as urban or rural36) health sector, level of care, experience and postgraduate training. Despite these attempts, diversity remained relatively limited and participant demographics and its potential influence on compliance warrants discussion.

The average age of participants was substantially lower than the age of hand therapist reported in the USA42. Younger participants were included in the sample given that novice therapists are frequently required to treat hand-injured patients in South Africa43 and the majority (67.7%) of the South African occupational therapy population is under 40 years of age44. Only one of the participants was male and spoke an African home-language. This is indicative of an occupational therapy workforce in South Africa that remains 95% female and is only 1 7% Black African45.

It is reasonable to assume that the pre-dominance of English and Afrikaans-speaking therapists, typical within the hand rehabilitation community46 and occupational therapy profession, contributes to communication difficulties between patients and therapists23. The impact that language barriers have on compliance5 reiterate the need to address communication difficulties. The need for training in language and cultural competencies at an undergraduate and continuous professional development (CPD) level has been emphasized23. The opportunity for innovation within interpreter services also exists. However, it is acknowledged that patients "will be best served when the profile of the profession mirrors that of the general population because of language, culture and other contextual factors"44:10. This therefore needs to be considered as we explore ways to optimise compliance and seek to develop the occupational therapy workforce strategically.

Compliance - does the term matter?

Participants almost unanimously understood compliance as patients adhering to appointments and prescribed treatment. Beyond this, their understanding of the term demonstrated variation in the power relationship between patient and therapist and the level of responsibility of patients. The literature suggests that the use of different terms captures these nuances. Trostle argued that beyond a mere term, compliance is an ideology that reinforces the authority of health professionals over patients14. Concordance has been suggested as an alternative term that appears to flatten power relations and captures the act of agreement between patient and professional47. Recent hand rehabilitation literature has recommended that the term adherence be used as it speaks to occupational therapy's core value of client-centred practice16 and also captures the concept of agreement16.

It can be argued however that each of the above three terms can hold similar meaning, depending on the definition used47,48. This is not to suggest that the choice of term does not matter as changing a term may in itself facilitate a change in thinking49. However, merely switching terms may not necessarily change practice and the power sharing that occurs within it. Terms that are used tend to be an indication of prevailing societal ideas49. Engaging in critical reflection and conversations around the philosophical assumptions that underpin the terms that are used is thus important. This may be essential to promoting client-centred50 practice and for therapists to remain life-long learners that practice in a contextually responsive manner.

Enabling compliance through: addressing barriers and harnessing supports

Participants' perspective on the factors impacting hand-injured patient compliance strongly resonated with the dimensions described by the WHO's Multidimensional Adherence Model (MAM)26. Participants described a number of patient-related factors but spoke more extensively of multi-level contextual features. Agreeing that compliance is a product of more than patient-related factors26, hand therapy literature has called for hand therapists to "stop blaming our patients"16249- This study reiterates the WHO recommendation that the simultaneous influence of multiple factors be acknowledged and interventions targeted at all dimensions26.

All of the themes that emerged in is study in some way speak to health care team and system factors26having an influence on compliance to hand rehabilitation. This dimension is believed to be understudied within hand rehabilitation and development in this area is needed as it constitutes an area where health professionals are able to exercise change16. The findings in the study provided description of a failing primary health care (PHC) system that has necessitated a re-engineering of PHC and National Health Insurance in South Africa35. Although the MDT may not be able to exert influence at all levels of health care, opportunities exist to change systems and services to support compliance.

The WHO's MAM agrees with participants who believed that a dynamic MDT approach should be followed26, where patients' goals and preferences are elicited and integrated early into MDT treatment planning, and all team members communicate a shared message to patients16. The hand-injury care MDT would benefit from training about compliance and the interventions required to facilitate this26. In the diverse South African context, training to develop cultural humility and language and communication competencies may be essential to this23.

Similar to a previous hand therapy study1, participants believed that compliance is supported when intervention is responsive to the patients' lived reality. This speaks to the WHO's recommendation for treatment tailored to individual patient need26. It also resonates with the work of Donovan and Blake who suggest that for each intervention offered, patients "weigh up the costs and benefits...as they perceive them within the contexts and constraints of their everyday lives and needs"15207. It thus stands to reason that if intervention is tailored to fit the life and times of an injured hand, then compliance is supported.

This study highlighted the perceived negative influence of an inequitable society, disempowerment, passivity and a paternalistic health system. These subtle yet impactful features are not overtly described in the MAM26. Donovan and Blake argue that "patients are not on the whole passive or powerless" but "quite capable of making decisions about treatments and lifestyles rationally within the contexts of their beliefs, responsibilities and preferences"15:508. The views of these scholars working in the British National Health System may not hold true for the South African context where the health system has been shaped by systemic discrimination and inequality over centuries17. Although patient empowerment and active participation in health care decision making is ethically and legally supported, patient passivity or deferment of decision-making to doctors is commonplace49.

The powerful collaboration perspective offered by this study addresses the problem of a passive patient role, and reiterates the recommendations of previous research1,15. It has been suggested that therapists should balance their goals for therapy with their patients' intervention goals18. If hand rehabilitation were likened to a journey, this recommendation may be akin to 'meeting the patient halfway'. Findings, however, seemed to suggest a subtly nuanced posture where patient and therapist start out on the therapy journey together. From the start, the destination is envisioned together, directions negotiated, and the therapist and patient become partners or co-authors of the rehabilitation process. Participant views seem to suggest that it is within this relational positioning that power, which is frequently inequitably distributed, can be shared and harnessed for enhancing patient outcomes.

Another element considered to facilitate powerful collaboration was therapy that was directed towards enabling occupational participation and combined aspects of the medical model and client-centred practice. Within the hand rehabilitation literature, functional or occupation-based intervention has been recommended as a therapy-related factor that can be used to improve patient compliance16. An occupation-based approach, along with flexibly and collaboratively tailoring protocols, has been recommended for rural hand rehabilitation practice51. Although challenges exist to implementing such an approach22, a growing body of evidence52,53 suggests that opportunities be provided for therapists to develop their occupation-based knowledge and skill.

The dimension of social and economic factors26was evident in each of the themes in this study. "Your hand is your life" captured the influence of hand injuries and the compounded loss when injury to the so-called earning tool54 occurs within an impoverished context. Participants described complex social and economic and social factors that significantly hindered compliance and outcomes. This highlights the need for research that investigates the relationship between hand injury care and the social determinants of health. While on-going research, education and training should be invested in curative and rehabilitative care, the need for the hand-injury care community to take up its role in hand-injury prevention and hand health promotion is evident.

To the author's knowledge, this is the first study to report a therapist perspective on compliance in a LMIC. This paper, however, does not communicate patients' views on compliance. This perspective is critical, especially given the socio-political history of the South African health system, and leaves room for a patient voice in future research. A further limitation of the study relates to the transferability of the findings. Although the demographic characteristics of participants is reported, a lack of dense description of the participants and their contexts restricts the readers ability to judge the transferability of the findings40.

CONCLUSION

Against the backdrop of an impending healthcare overhaul in South Africa35 and challenged healthcare systems globally55, patient compliance is considered critical to health system effectiveness and the improvement of healthcare outcomes26. Within the field of hand rehabilitation, scholars have highlighted the importance of changing the term that we use from compliance to adherence16. Of equal importance, however, is the need for occupational therapists to interrogate the beliefs and assumptions that underpin the terms that we use and which influence our actions and dispositions within the therapeutic relationship.

Results of this study suggest that collaborative co-construction, or co-authoring of the hand rehabilitation process is central to enabling compliance. Therapists require a robust understanding of the person they are treating and the complex context in which they participate in daily life. Communication should be accessible and education effective to support a collaborative relationship, and this should be reinforced by a foundation of systems and services that work.

REFERENCES

1. Groth GN, Wulf MB. Compliance with Hand Rehabilitation: Health Beliefs and Strategies. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1995; 8(1): 18-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0894-1130(12)80151-7 [ Links ]

2. Mncube NM, Puckree T. Rehabilitation of repaired Flexor Tendons of the Hand: Therapists' perspective. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2014; 70(2). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajp.v70i2.270 [ Links ]

3. Wentzel R van Velze C, Rudman E. Comparison of the Outcomes of 2 Rehabilitation Protocols After Flexor Tendon Repair of the Hand at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa. University of Pretoria; https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/61677 [ Links ]

4. Spark T, Ntsiea V Godlwana L. The Impairments and Functional Outcomes of Patients Post Flexor Tendon Repair of the Hand. Hand. 2016; 11(1suppl): 1415-1415. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558944716660555jv [ Links ]

5. Spark T, Godlwana L, Ntsiea M. Range of movement, power and pinch grip strength post flexor tendon repair. SA Orthopaedic Journal. 2018;1 7(1): 47-54.Mhttp://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8309/2018/v17n1a7 [ Links ]

6. Dias JJ, Garcia-Elias M. Hand injury costs. Injury. 2006; 37(1 1): 1071-1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2006.07.023] [ Links ]

7. Johnson W, Onuma O, Owolabi M, Sachdev AS. BulleJohnson, W., Onuma, O., Owolabi, M., & Sachdev, A. S. Stroke: a global response is needed. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2016; 94:(Feb):634-634A. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.181636 [ Links ]

8. Norman R, Bradshaw D, Schneider M, Pieterse D, Groenewald P Revised Burden of Disease Estimates for the Comparative Risk Factor Assessment , South Africa 2000. Medical Research Councel of South Africa. 2006. Avaiable at: https://www.samrc.ac.za/sites/default/files/files/2017-07-03/RevisedBurdenofDiseaseEstimates1.pdf [Accessed: 22nd January 2019] [ Links ]

9. Industrial Health Resource Group. Organising for Health and Safety. A guide for trade unions. 2nd ed: Section 8 Compensation for injured or ill workers. 2011. Avaiable at: http://www.ihrg.org.za/oid/downloads/4/10_8_6_47_31_AM_Section08-Compensation (Final).pdf [Accessed: 4th March 2017] [ Links ]

10. Schultz G, Mostert K, Rothmann I. Repetitive strain injury among South African employees: The relationship with burnout and work engagement. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2012; 42(5): 449-456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2012.06.003 [ Links ]

11. Jeebhay M, Jacobs B. Occupational health services in South Africa. South African health review; 1999. Available at: https://www.hst.org.za/publications/South_African_Health_Reviews/sahr1999.pdf [Accessed: 17th Feburary 2020] [ Links ]

12. Clark G. The Case for Hand therapy. TCM. 2002;78: 75-78. [ Links ]

13. Kelly G. Regulating access to the disability grant in South Africa , 1990-2013. Report number: 330, 2013. Avaiable at: http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/cssr/pub/wp/330 [Accessed:2nd June 2020] [ Links ]

14. Trostle JA. Medical compliance as an ideology. Social Science and Medicine. 1988; 27(12): 1299-1308. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(88)90194-3 [ Links ]

15. Donovan JL, Blake DR. Patient non-compliance: Deviance or reasoned decision-making? Social Science and Medicine. 1992; 34(5): 507-513. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(92)90206-6 [ Links ]

16. O'Brien L. The evidence on ways to improve patient's adherence in hand therapy. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2012; 25(3): 247-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2012.03.006 [ Links ]

17. Coovadia H, Jewkes R Barron P Sanders D, McIntyre D. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. Lancet. 2009; 374(9692): 817-834. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60951-X [ Links ]

18. Kirwan T, Tooth L, Harkin C. Compliance with hand therapy programs: Therapists' and patients' perceptions. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2002; 15(1): 31-40. https://doi.org/10.1053/hanthe.2002.v15.01531 [ Links ]

19. Sandford F Barlow N, Lewis J. A Study to Examine Patient Adherence to Wearing 24-Hour Forearm Thermoplastic Splints after Tendon Repairs. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2008; 21(1): 44-53. https://doi.org/10.1197/j.jht.2007.07.004 [ Links ]

20. Kingston GA, Williams G, Gray MA, Judd J. Does a DVD improve compliance with home exercise programs for people who have sustained a traumatic hand injury? Results of a feasibility study. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. 2014; 9(3): 188-194. https://doi.org/10.3109/17483107.2013.806600 [ Links ]

21. Cole T, Robinson L, Romero L, O'Brien L. Effectiveness of interventions to improve therapy adherence in people with upper limb conditions: A systematic review. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2019; 32(2): 175-183.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2017.11.040 [ Links ]

22. de Klerk S, Badenhorst E, Buttle A, Mohammed F, Oberem J. Occupation-based hand therapy in South Africa: challenges and opportunities. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 46(3): 10-15. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3a3 [ Links ]

23. van Stormbroek K, Buchanan H. Novice occupational therapists: Navigating complex practice contexts in South Africa. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2019; 66(4): 469-481. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12564 [ Links ]

24. Sherry K. Disability and rehabilitation: Essential considerations for equitable, accessible and poverty-reducing health care in South Africa. South African Health Review 2014/2015. 2015; Number 1: 89 - 99. Avaiable at: https://journals.co.za/docserver/fulltext/healthr/2014/1/healthr_2014_2015_a9.pdf?expires=1579870078&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=4D177B0C7EC7AB2A0A2DE0A56FE18050 [Accessed: 5th March 2020] [ Links ]

25. Becker MH, Maiman LA, Kirscht JP, Haefner DP, Drachman RH, Taylor DW. Patient perceptions and compliance: recent studies of the Health Belief Model. In: Haynes R DW T, DL S (eds.) Compliance in healthcare. Johns Hopkins University Press; 1979: 78-109. [ Links ]

26. De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00091-4 [ Links ]

27. Chandra S, Mohammadnezhad M, Ward P Trust and Communication in a Doctor- Patient Relationship: A Literature Review. Journal of Healthcare Communications. 2018; 03(03): 1-6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-1654.100146 [ Links ]

28. Smith-Forbes E, Howell D, Willoughby J, Armstrong H, Pitts D, Uhl T. Adherence of Individuals in Upper Extremity Rehabilitation: A Qualitative Study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016; 97(8): 1262-1268.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2015.11.008 [ Links ]

29. Moomba K, van Wyk B. Social and economic barriers to adherence among patients at Livingstone General Hospital in Zambia. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine. 2019; 11(1): 1-6. https://doi.org/I0.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1740 [ Links ]

30. O'Brien L. Adherence to therapeutic splint wear in adults with acute upper limb injuries: A systematic review. Hand Therapy. 2010; 15(1): 3-12. https://doi.org/10.1258/ht.2009.009025 [ Links ]

31. Moran ME, Eskander P Cronin K, Cohen N, Jones R, Frisch K. Client Factors Affecting Adherence to CMC Orthosis Usage: A Qualitative Approach. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2016; 29(3): 382-383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2014.08.038 [ Links ]

32. Department of Health Republic of South Africa. National Department of Health: Language Policy; 2015. Avaiable at: http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/150527healthlanguagepolicy.pdf [Accessed: 16th April 2020] [ Links ]

33. Scott J, Castelli J, Valdes K. The use of a temperament test to increase HEP adherence. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2019.03.011 [ Links ]

34. Lambert V Lambert C. Qualitative Descriptive Research: An Acceptable Design. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research. 2013; 16(4): 255-256. [ Links ]

35. Department of Health Republic of South Africa. White Paper: National Health Insurance Policy - Towards Universal Health Coverage. Department of Health; 2017. Avaiable at: https://www.gov.za/about-government/government-programmes/national-health-insurance-0 [Accessed: 21st May 2020] [ Links ]

36. Rural Health Advocacy Project. Rural Health Fact Sheet 2015; 2015. Avaiable at: http://www.rhap.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/RHAP-Rural-Health-Fact-Sheet-2015-web.pdf [Accessed: 17th March 2020] [ Links ]

37. Marks D, Yardley L. Content and Thematic Analysis. In: Marks D, Yardley L (eds.) Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology. Sage Publications; 2011: 56-68. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209793.n4 [ Links ]

38. VERBI GmbH. MAXQDA. 2018. Avaiable at: https://www.maxqda.com/products/new-in-maxqda-12 [Accessed: 4th April 2020] [ Links ]

39. Creswell J. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches.. 4th ed. Research design. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2013:1-26 . [ Links ]

40. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991; 45(3): 214-222. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.3.214 [ Links ]

41. Foronda C, Baptiste D, Reinholdt M, Ousman K. Cultural Humility: a concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2016; 27(3): 210-217. [ Links ]

42. Stegink-Jansen CW, Collins PM, Lindsey RW, Wilson JL. A geographical workforce analysis of hand therapy services in relation to US population characteristics. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2017; 30(4): 383-396.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2017.06.004 [ Links ]

43. van Stormbroek K, Buchanan H. Novice therapists in a developing context: Extending the reach of hand rehabilitation. Hand Therapy. 2017; 22(4): 141-152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758998317720951 [ Links ]

44. Ned L, Tiwari R Buchanan H, Van Niekerk L, Sherry K, Chikte U. Changing demographic trends among South African occupational therapists: 2002 to 2018. Human Resources for Health. Human Resources for Health. 2020; 18(1): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-0464-3 [ Links ]

45. The Health Professions Council of South Africa. Report on the demographics of registered occupational therapists. Pretoria; 2019. [ Links ]

46. The South African Society of Hand Therapy The South African Society of Hand Therapists Members Booklet. Members Booklet. Avaiable at: https://www.sasht.org.za/MEMBERS%20BOOK-LET%20Version%208%20as%20of%2012%20October%20%202020.pdf [Accessed: 20th July 2020] [ Links ]

47. Aronson JK. Compliance, concordance, adherence. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2007; 63(4): 383-384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02893.x [ Links ]

48. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge Dictionary; 2019. Avaiable at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/adherence [Accessed: 11th July 2019] [ Links ]

49. Rowe K, Moodley K. Patients as consumers of health care in South Africa: The ethical and legal implications. BMC Medical Ethics. 2013; 14(1): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-14-15 [ Links ]

50. Hammel KRW. Client-centred occupational therapy: the importance of critical perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 22: 237-243. [ Links ]

51. Kingston GA. Commentary: Rehabilitation for Rural and Remote Residents Following a Traumatic Hand Injury. Rehabilitation Process and Outcome. 2017; 6: 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179572717734204 [ Links ]

52. Grice KO. The use of occupation-based assessments and intervention in the hand therapy setting - A survey. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2015; 28(3): 300-306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2015.01.005 [ Links ]

53. Che Daud AZ, Yau MK, Barnett F Judd J, Jones RE, Muhammad Nawawi RF. Integration of occupation based intervention in hand injury rehabilitation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Hand Therapy.; 2016; 29(1): 30-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2015.09.004 [ Links ]

54. Rabiul Islam S. 'Acute Occupational Hand Injuries With Their Social and Economic Aspects: A Hospital Based Cross Sectional Study'. Orthoplastic Surgery & Orthopedic Care International Journal. 2017; 1(1): 15-18. https://doi.org/10.31031/ooij.2017.01.000505 [ Links ]

55. Sanchez-Serrano I. The world's health care crisis: from the laboratory bench to the patient's bedside. 2011; Elsevier Inc. London. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kirsty van Stormbroek

kirsty.vanstormbroek@wits.ac.za

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Kirsty van Stormbroek conceptualised and conducted the research.