Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.50 n.3 Pretoria Dec. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2020/vol50no3a2

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

The role of Occupational Therapy in Africa: A scoping review

Julia Jansen van VuurenI; Christiana OkyereII; Heather AlderseyIII

IBOcc Ther (Hons) (University of Queensland, Australia) http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5232-976X; PhD Candidate, Queen's University, Canada

IIBA (University of Ghana, Ghana); MA (Kofi Annan International Center for Conflicts, Peace and Security, Ghana); PhD (Queen's University, Canada) http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0098-3049; Hegarty Post-Doctoral Fellow, Department of Counselling, Educational Psychology, and Special Education, Michigan State University, USA

IIIBA (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA); MSc (University of Kansas, USA); PhD (University of Kansas, USA) http://orcid.org/0000-000l-7763-5934; Associate Professor (Queen's National Scholar), School of Rehabilitation Therapy, Queen's University, Canada

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: This scoping review explores the role of occupational therapy in African countries including major practice areas, specific activities within practice areas, and potential considerations unique to the African context

METHOD: Two authors independently reviewed articles from online database searches and manual searches of reference lists and specific Occupational Therapy journals using a combination of keywords related to 'Occupational Therapy', 'Africa', and 'role'. Articles were included based on pre-determined eligibility criteria (i.e., peer-reviewed, English articles that describe occupational therapists' tasks/ activities) and discussion to reach consensus. The authors charted data through content analysis of the articles based on the review's objectives prior to drawing out common themes relevant to the African context

RESULTS: Thirty-two articles were included covering twelve African countries, though predominantly focused on South Africa. Findings demonstrate that, despite having tasks specific to practice areas, the overarching role of occupational therapy is facilitating engagement in meaningful occupation. Additionally, the findings highlight a vital role for African therapists in community-based services and the need to consider the unique cultural context in practice

CONCLUSION: Congruent with universal occupational therapy principles, Occupational Therapy in Africa aims to facilitate engagement in meaningful occupation, but therapists should consider their unique cultural context to ensure meaningful and sustainable outcomes whilst maintaining a valuable universal identity

Key words: Occupational Therapy, Occupational Therapists, Africa, role, culture, community-based

INTRODUCTION

"Occupational therapy in Africa; changing lives positively" was the theme emphasised by the Occupational Therapy Africa Regional Group (OTARG) during their 2017 Congress in Ghana. But how exactly do occupational therapists change lives positively, and what is their role, specifically in an African context? The aim of this scoping review is to analyse published literature to better understand the role of occupational therapy in Africa by: (a) identifying major practice areas for occupational therapists in Africa; (b) identifying the specific tasks and activities of occupational therapists in Africa; and (c) exploring the contextual considerations for occupational therapy in African contexts.

Globally, occupational therapists work with people across the lifespan, from infants to older adults, supporting their engagement in meaningful occupation, including self-care tasks, domestic and community activities, work (paid and volunteer), education, leisure, and social interactions1. Despite originating in Europe and North America, occupational therapy's foundational principles regarding health promotion by enabling participation in meaningful occupation is globally relevant, and the profession has spread to low and middle-in come countries, including African countries. The official inauguration of the World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT) by ten countries in 1952, united the profession more globally, although South Africa was the only African country represented2. Currently, there are twelve African countries with full WFOT membership (Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Morocco, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe) and three countries with associate membership (Namibia, Nigeria and Tunisia). The WFOT also encouraged the formation of regional groups to promote the international development of occupational therapy, hence the initiation of the African regional group in 1996, which currently has sixteen member countries (although not all of them offer established occupational therapy education or services).

Occupational therapists in Africa work across a broad spectrum of areas including, but not limited to: public and private hospitals, non-government organisations, insurance companies and private rehabilitation centres, for people of all ages, in physical and mental health, HIV/AIDS, palliative care, trauma, and Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR)3,4. The 2010 publication of 'Occupational Therapy: An African Perspective' provides an overview of the occupational therapy role by describing the influence of diverse cultures on practice, as well as chapters focused on specific practice areas5. Roles are broadly categorised into several main activities: (a) planning and consulting (e.g., team meetings, programme development); (b) networking/liaising (e.g., with funders, stakeholders, raising awareness); (c) administration (e.g., finances, reports, funding proposals, client records); (d) capacity building (e.g., teaching and supervising students/ health workers, research, facilitating groups); (e) 'hands-on' therapy (e.g., education, functional assessments, pressure garments, splinting, hand therapy, treatment plans, assistive aids, environmental modifications, cognitive and daily-living tasks re-training); and (f) advocacy (e.g., lobbying for human rights and inclusion)4. A more recent article, 'An Overview of Occupational Therapy in Africa' identifies occupational therapy practice and education locations and briefly describes various practice areas from a selection of African countries3. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no formal review systematically summarising published literature on the role (practice settings, clients, activities, and goals) of occupational therapy in African contexts. Most published literature related to Occupational Therapy in Africa tend to focus on specific practice areas and highlight a great need for occupational therapy as well as a range of challenges3,4,6,7. Although it is impossible to define a singular, static list of roles for occupational therapy in Africa (as it is a vast continent with a diverse range of cultures, traditions, and spiritual practices)7, identifying common themes as well as unique differences in specific contexts, can contribute to a deeper understanding of this global profession. In addition, understanding the role of occupational therapists in other African contexts can assist to inform the development of occupational therapy education, research and practice in African contexts where there is a great need for rehabilitation professionals but where occupational therapy is less established8,9. Clarifying the occupational therapy role can also promote the profession globally and mitigate role overlap or conflict with other health professions10,11, particularly when, in many African contexts, the profession can be unfamiliar or misunderstood 12-14. Thus, this scoping review builds on previous knowledge by systematically identifying and synthesising what is known from published literature about the role of occupational therapy in various African countries and to explore what makes the role unique in an African context.

METHOD

Guided by Arksey and O'Malley's15 methodological framework for scoping reviews, we initially identified the purpose of the study and a broad research question - What is the role of Occupational Therapy in Africa? Based on descriptions from the 'Occupational Therapy: An African Perspective' textbook5, as well as WFOT16, and the American17, Canadian18, and Australian19 Occupational Therapy Associations, we defined 'role' as incorporating what occupational therapists do (e.g., tasks/activities, assessment, intervention), who they work with (e.g., clients), where they work (e.g., practice settings, positions), and the goals of occupational therapy (e.g., participation, quality of life). The following steps, identifying relevant studies and study selection, began with consulting a Health Sciences librarian to determine appropriate databases and search terms based on the research question. Two authors then met to discuss inclusion/exclusion criteria (see Table I) and in June 2019 they searched the following databases: CINAHL, Embase, Medline, Global Health, and PsycINFO. Search terms included: 'Occupational Therapy' or 'Occupational Therapists' and 'Africa'. (See Appendix I for sample database search strategy on p.14.)

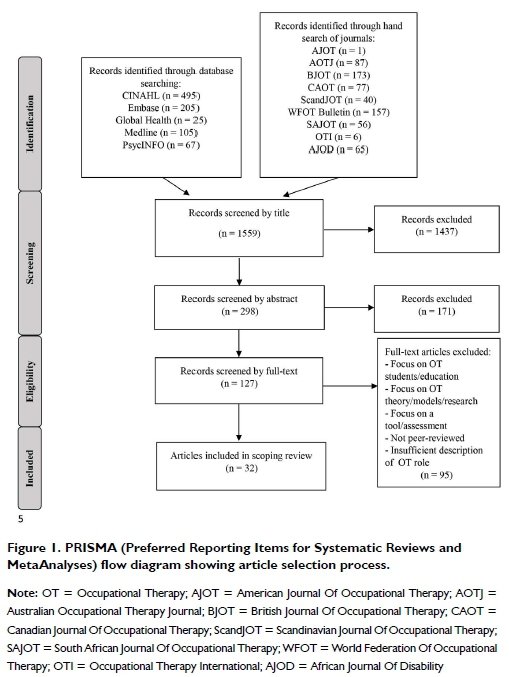

Title screening was completed together, whereas abstract, and subsequent full-text reviews were conducted independently before the authors met again to discuss and resolve discrepancies. In addition, we manually searched relevant occupational therapy and Africa-specific journals under Africa', 'role' or 'Occupational Therapy', including the South African, American, Canadian, Australian, British, and Scandinavian Journals of Occupational Therapy, Occupational Therapy International, the WFOT Bulletin, and African Journal of Disability, to identify appropriate articles. We also checked reference lists of identified articles to ensure we had not missed other potentially relevant articles. Figure 1 (on p5 ) provides a representation of study selection.

Since the establishment of OTARG in 1996 marked some cohesion of the profession within the African continent, we included sources from 1996 onwards and full-text articles in English. Step 4, charting the data, involved two authors meeting to develop a data charting form which comprised a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet with headings: author, title, date, research design, country, practice area, role (including tasks/activities), and additional information or themes related to African contexts specifically. These variables provided general information about the distribution of studies as well as information related specifically to our research objectives. To extract information about the occupational therapy role, we returned to our definition and searched for descriptions of what occupational therapists do, who they work with, where they work, and their goals. In order to answer our final objective (contextual considerations), we extracted information from each article that related to contextual influences on the practice of occupational therapy. The authors independently extracted data from the selected studies using qualitative content analysis where we each familiarised ourselves with the articles and systematically searched for descriptions, concepts and themes related to our definition of the occupational therapy role as well as contextual influences. The data extraction involved an iterative process where we met several times to discuss our findings and any discrepancies, so as to capture all of the relevant information and to ensure consistency20. Finally, we collated, summarised and reported the results by systematically analysing the data extracted from each article and describing the articles' characteristics, before identifying broader qualitative themes in relation to the overall purpose and research question (i.e., major practice areas, activities, contextual considerations). We subsequently discussed overarching implications for occupational therapy practice, research, and policy in African contexts.

RESULTS

Overview of the literature

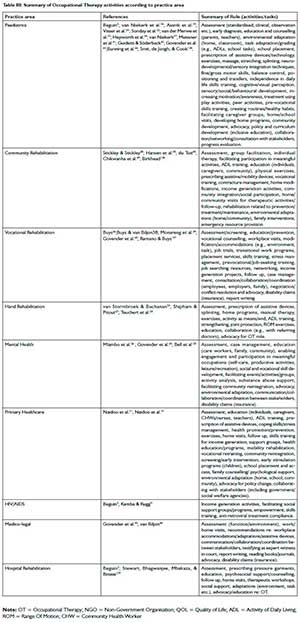

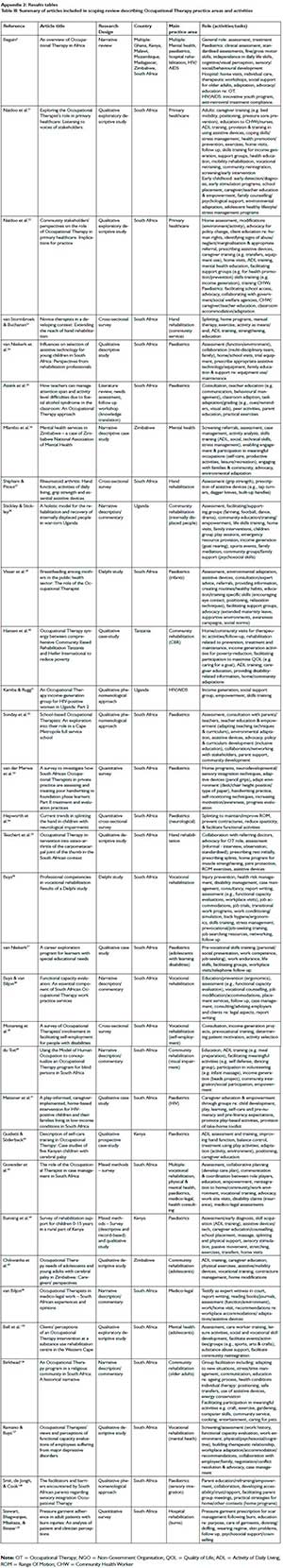

Out of 1559 articles screened by title, and 127 full texts screened, we included 32 articles in the scoping review (Figure 1), of which 24 related to South Africa, two each from Kenya, Uganda, Zimbabwe, one from Tanzania, and one covering multiple African countries (Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Madagascar, Zimbabwe and South Africa). South Africa dominated the literature as it has the most long-established practice and even a specific Occupational Therapy journal. The articles covered the occupational therapy role across diverse practice areas with the majority focused on paediatrics (n = 11), community rehabilitation (n = 5), and vocational rehabilitation (n = 4). Other practice areas included hand rehabilitation (n = 3), mental health (n = 2), primary healthcare (n = 2), HIV/AIDS (n = 1), hospital rehabilitation (n = 1), medico-legal practice (n = 1), and multiple practice areas (n = 2). Due to overlapping practice areas, it was sometimes difficult to clearly delineate between them (e.g., mental health and vocational rehabilitation). The authors of these articles discussed various occupational therapy activities within these practice areas, shown in Table II (Appendix 2, p15). Occupational therapy activities are also summarised according to practice areas in Table III (Appendix 2, p15). Table III describes several overarching themes aligned with our objectives regarding the role of occupational therapy in Africa.

Major practice area for occupational therapy in Africa: Co m m unity-based services

Although our findings indicate that occupational therapists work in a variety of practice areas, many authors highlight the need for therapists in communities rather than urban institutions, whether they work in paediatrics, vocational rehabilitation, or any another area. With limited human resources and large proportions of the population living rurally, occupational therapy services need to be accessible to communities. South Africa has attempted to address this need with their compulsory community service for newly graduated occupational therapists21-23. However, they often face multiple challenges in rural settings. For example, van Niekerk, Dada, and Tonsing discuss how some assistive technology supplies never reach the most rural areas because drivers offload everything at one centre and claim they are "tired of driving"24:919. Hence, occupational therapists need to be resourceful, flexible, and creative, ensuring realistic interventions that require minimal cost/ effort, use local materials, and are appropriate to the environment2427. Therapists also often receive limited support when working rurally and van Stormbroek and Buchanan23 emphasise the need for more professional development and mentoring for community-based therapists.

Several authors encourage occupational therapists to adopt a population approach rather than focusing on individual clients, as many African cultures value collectivism and interdependence with rich family and community networks. This involves collaboration with multiple community stakeholders, including families, community health workers, and local leaders, to ensure sustainable, appropriate service provision with meaningful outcomes for the whole community21,22,24,28,29. One example from Tanzania demonstrates the role of occupational therapy in a collaboration between a local CBR program and an international aid organisation supporting children with disabilities, highlighting the need to address issues of poverty, drought, and malnutrition by empowering the entire family and community through income generation projects30. Several authors highlight how occupational therapists engage groups of people rather than focusing exclusively on individuals, including in a Ugandan HIV/AIDS income-generation group31 and South African paediatric services32,33. Health promotion and disability prevention are also described as important aspects of the occupational therapy role in a community-based approach21,22.

Occupational Therapists' activities: Empowering people to engage in meaningful occupation

Regardless of country or practice area, most of the articles demonstrate that the essential role of an occupational therapist is empowering people to engage in meaningful occupations through holistic, client-centred practice - whether it be for a child or adult, within an institution or community. Although many of the generic tasks and activities mentioned in the articles appear to be the same for occupational therapists in any country (e.g., assessment, education, environmental adaptation, skills training), the context influences therapists' priorities and approach. For example, several authors describe how, in assessment, occupational therapists often rely on informal methods (e.g., observation, interview) or adapt formal measures because most standardised tools are developed in Western countries34,35. In terms of interventions, the prevalence of poverty and limited employment opportunities for people with disabilities in various African contexts behoves occupational therapists to focus on vocational skills36-38, facilitating self-employment39 and other options for income generation30,31,40.

Many authors describe education as an important aspect of empowering people; for example, providing caregiver education to increase understanding and acceptance of children with disabilities in South Africa21,41, Kenya42, and Tanzania30. Additionally, several authors highlight community education as crucial for reducing stigma, for example, of women escaping abduction in war-torn Uganda28 or of people with mental health conditions in Zimbabwe26. Educating community workers around health promotion and rehabilitation as well as task shifting is also mentioned as an important role for therapists to promote sustainable, relevant service provision21.

Advocacy is highlighted as another crucial role for occupational therapists in supporting people with disabilities to engage and participate in their communities; for example, lobbying governments to change policies for more accessible transport or inclusive education for children with disabilities in South Africa22. Occupational therapists have a major advocacy role in facilitating people to return to work38,43, as well as advocating for extended maternity leave and supportive environments for breastfeeding mothers29.

In addition to advocating for their clients, several authors emphasise that occupational therapists need to advocate for their profession due to limited awareness and understanding of the occupational therapy role3. For example, authors highlight that therapists need to advocate for the value of their role in schools32, primary health care22, and case management43. Some authors mention challenges for therapists to find jobs and the prevalence of 'brain drain' because their role is not well known or understood in their own countries3,26.

What makes the role of occupational therapy unique in Africa: Contextual considerations

Most of the articles refer to contextual considerations that influence the role of occupational therapy in Africa. As mentioned previously, poverty is prevalent in many African contexts and often guides the priorities and focus of occupational therapy interventions. For example, poverty and malnutrition for families of children with disabilities in Tanzania30, Kenya44, and South Africa29,41, and adolescents in Zimbabwe45 require therapists to consider the whole family's needs, not just the individual child. Poverty is often connected with lower education levels affecting how therapists provide information and therapy. For example, therapists collaborating with illiterate caregivers may preference simpler assistive technology for their children with disabilities24, or avoid focusing on writing as a goal for older adults with arthritis in South Africa27. Minimal government funding and support perpetuates the challenges for people accessing services and limits resources available for occupational therapists to implement effective interventions3.

Several authors discuss how violence and political instability influence the role of occupational therapy. Stickley and Stickley28 highlight the role of occupational therapy to support occupational engagement and improve wellbeing for internally displaced people in Uganda who have experienced trauma from war. South African researchers also discuss high rates of violence and crime which affect the occupational therapy role. For example, children losing their primary caregivers perpetuates the cycle of poverty and creates a young population21,24; the prevalence of poverty, violence and road accidents increases hand and other injuries requiring more specialist hand therapists, medico-legal and vocational rehabilitation23,46.

Although evident in high-income contexts, stigma and discrimination against people with disabilities tend to have more severe consequences in African contexts, often due to limited disability knowledge and beliefs about aetiology, thus requiring a greater role for therapists in advocacy and education24,44. For example, the literature demonstrates that occupational therapists are involved in reducing stigma and isolation and promoting sustainable community reintegration for people with mental health conditions in Zimbabwe26, supporting families of children with disabilities in Kenya44, and educating communities to improve acceptance of girls who were abducted, raped and escaped during war in Uganda28. Stigma appears common amongst people with HIV/AIDS which is widespread in several African contexts, hence occupational therapists facilitate groups for social support and income-generation in Uganda31, or provide education and empower caregivers of South African children with HIV41.

With a diverse variety of cultures and languages across the African continent as well as within individual countries, many authors promote the imperative for culturally sensitive practice. For example, Guidetti and Söderback42 highlight that Kenyan paediatric therapists must be conscious of the climate and traditional clothing styles when teaching children dressing skills, but also holistically support the whole family and allow flexibility in scheduling appointments. Naidoo et al.21,22 emphasise that occupational therapists in rural South African settings need to be particularly sensitive to culture and context, including communicating in local languages and partnering with community health workers to ensure culturally relevant practice. The literature also indicates that occupational therapists need to be aware of cultural gender roles when using occupation or providing education. For example, in Zimbabwe mothers are the main caregivers45, whilst in Uganda women may be unfamiliar with leadership roles outside of their home31, and war can cause people to lose traditional gender roles and subsequent aspects of self-identity28. Additionally, when recommending assistive technology and environmental adaptations, occupational therapists need to consider the unique environment such as age-appropriate wheelchairs for Zimbabwean adolescents with cerebral palsy45, or appropriate symbols for communication devices for South African children24.

DISCUSSION

The findings from this scoping review demonstrate that African occupational therapists are working in diverse practice areas, from paediatrics to medico-legal practice to working with those with HIV/ AIDS; however, an overarching theme that emerged was the need to develop rural community-based services to reach the majority of the population. Regardless of country or practice area, the primary role of occupational therapists in African contexts is congruent with the universal goal of occupational therapy: to promote engagement in meaningful occupations. Thus, broadly speaking, African occupational therapists engage in universally practiced tasks and activities such as assessment, education, environmental adaptation and equipment prescription. However, contextual considerations also significantly influence the priorities and specific ways that occupational therapists undertake their role and it is crucial for all therapists to be aware of and address these unique considerations to ensure sustainable, culturally relevant practice. These findings have important broader implications for occupational therapy practice, policy, and research within African contexts which we discuss further below.

How does context influence the role of occupational therapy?

Occupational therapy goals often focus on roles and occupations which are substantially influenced by cultural and contextual assumptions; hence, assessments and interventions need to be culturally meaningful to align with the profession's universal principles of client-centred, holistic practice47-50. In fact, several authors have criticised some of the profession's dominant assumptions as privileging a minority Western, middle-class perspective and disregarding diverse cultural values51-57. For example, Western occupational therapy principles tend to emphasise independence, personal autonomy, performance, and achievement, which can undermine collectivist values of interdependence and relationships that are often more important in African contexts47,52,54,58. Beagan51 explores various approaches to diversity and culture and encourages occupational therapists to move beyond the more established concept of cultural competence towards cultural humility and critical reflexivity, recognising power imbalances and seeking to rectify these through flexible, humble, and client-centred processes.

Although Africa comprises a multitude of diverse cultures and occupational therapists need to understand the unique culture that they work within, there are some common challenges as well as overarching principles that can be considered. For example, 'ubun-tu' is a widely shared philosophy across Sub-Saharan Africa, where interdependence and relationships are highly valued, and individual identity is defined through belonging within a community59-61. The principles of 'ubuntu' include respect and dignity, solidarity, spirituality, reciprocity, harmony, mutuality, affinity and kinship60. Many of these principles are congruent with the profession's own foundations and, regardless of context, the occupational therapy role should "promote concern for humankind and address broader occupational needs in society"62:4.

The role of occupational therapy in Africa related to practice

The findings from this review indicate that occupational therapy practice in Africa should perhaps adopt a more community approach rather than the traditional individual focus. As mentioned above, 'ubuntu' highlights the importance of family and community in many African contexts. Ramugondo and Kronenberg explore the concept of 'ubuntu', "emphasising collective occupational well-being as a principal focus of practice"63:12, whilst demonstrating that individual and collective occupational needs are interactive and not necessarily dichotomous. In her dissertation, Chikwanha64 explores the influence of family involvement on occupational participation for adults recovering from substance abuse in Zimbabwe. Using a decolonial approach, she highlights how families are affected and the crucial role they play in supporting recovery and demonstrating resilience. She recommends a "collective occupational reconstruction treatment framework... [a] contextually relevant multidisciplinary occupation based framework that would respond to the unique occupational needs of the families in Zimbabwe"64:190 where families are involved at each level and collaboration with families and other community stakeholders is key. Similarly, for occupational therapists in South Africa working with adolescents with traumatic brain injuries, "[b]uilding the resources of informal supports notably that of a family is of importance, specifically as they tend to play an active and ongoing part of the adolescent's life and are therefore potential long-term consistent sources of support"65:12. Caregivers, particularly, must be included in occupational therapy interventions for children with disabilities, and Fewster, Uys and Govender66 suggest that more interventions need to directly focus on promoting caregiver quality of life, which then indirectly support the children and the whole family. However, despite the importance of involving family and the broader community, this does unearth potential ethical tensions for African occupational therapists, such as negotiating conflicts in goals between the therapist, family and client, or confidentiality issues with disclosing personal information67. Hence, to maintain the core principles of client-centred, holistic practice, occupational therapists need to consider the influence and needs of the family and community, whilst still prioritising and respecting the individual client61,62.

A population approach also aligns with CBR which seeks to empower whole communities, promote equal opportunities and social inclusion, reduce poverty and improve quality of life, and is designed for contexts with limited resources68,69. In fact, the South African Association's position statement on rehabilitation asserts that "Occupational therapists are committed to community based rehabilitation"70:53, and WFOT's position statement on CBR describes how: "Occupational therapists have been and are working in CBR as trainers and educators, with the aim of facilitating and developing programs and transferring knowledge and skills to community members. Others work 'hands-on' in the community, are accessible on a referral basis or work in the position as program leaders."71:1. However, Geberemichael et al.72 highlight the overall lack of effective implementation of CBR within African countries, primarily because such programs are not being implemented in rural communities and lack focus on health-related services. With appropriate support and infrastructure, occupational therapists could play a crucial role in addressing this gap by adopting CBR strategies to facilitate better access to services and promote occupational justice73. For example, South African occupational therapists working in primary healthcare, align with CBR strategies to foster community partnerships and facilitate long-term, sustainable outcomes22,74. Witchger-Hansen and Blaskowitz75 demonstrate a successful occupational therapy community-based vocational training program for Tanzanians with physical disabilities, finding improvements in occupational performance ratings specifically in regards to involvement in income-generating activities. Understandably, this requires African occupational therapy educational programs to incorporate CBR skill development, including skills in program development, evaluation and management, particularly through practice placements in local community settings, to ensure therapists are knowledgeable and competent in CBR practice approaches75-78.

In addition, our findings highlight the importance of advocacy as a crucial role for African occupational therapy practice, particularly in contexts where there are chronic issues of poverty, violence, social inequality, stigma, and limited resources3,4,6,7,22,70,79-82. The World Federation's position paper on human rights states that all occupational therapists "are obligated to promote occupational rights as the actualisation of human rights."82:1. However, this is perhaps more imperative in contexts where cultural beliefs around disability (including spiritual causation, stigma, and undervaluing people with disabilities) can lead to social exclusion, affecting the utilisation and effectiveness of rehabilitation services as well as major breaches in human rights83-86. HIV/AIDS, specifically, is often associated with 'sin' and false beliefs about contagion; hence occupational therapists can play a critical role in increasing hope and respect through education, empowerment, and support, and decreasing stigma through role modelling justice, inclusion, and tolerance3,87,88.

African occupational therapists must also consider practical implications for their role based on the context where they work. Our findings highlight the prevalence of poverty and the chronic lack of resources available to provide services in many African countries. As such, it is imperative that occupational therapists are adaptable and creative in their practice, able to utilise locally sourced materials and equipment, and focus on locally acceptable and feasible occupations24,30. This may require therapists to expand their view of 'occupation', for example supporting people who are involved in street vending89 or even gang membership90. In relation to home programs for South African children with cerebral palsy, Davies9' , highlights how therapists also need to be aware and empathetic towards families' priorities in light of poverty in order to address the underlying reasons for lack of engagement in occupational therapy activities. In addition, occupational therapists should be familiar with local languages or develop trustworthy relationships with translators, as language has a strong influence on service provision and outcomes21,91. Richards and Galvaan go further to discuss a socially transformative approach, where occupational therapists are more critically aware of socio-political influences on their clients' health and participation: "Therapists need to be intentional about researching and remaining up to date with current happenings in communities from which their patients come by reading local newspapers, listening to local radio stations and learning from patients. In doing so, the patient becomes the expert of their community and power is shared more equally between therapist and patient" 78:8.

The role of occupational therapy in Africa related to policy

Globally, occupational therapists work with people who face occupational deprivation and breaches in human rights; therefore, they need to move beyond individual level interventions and advocate for policy changes and community initiatives that address broader social inequalities and barriers to occupational participation92,93. Lencucha and Shikako-Thomas warn that: "If occupational therapy is not involved in shaping policy, it will find itself reacting to or being compelled to work with policy that may not be conducive to the values of the profession"94:191. From an African context, Chichaya, Joubert and McColl analyse disability policy in Namibia, finding "a disparity between perceptions of disability policymakers and persons with disabilities on the occupational needs of persons with disabilities. This disparity results in policymakers designing and approving disability policies that are inconsiderate of the need to ensure occupational participation among persons with disabilities."95:10. African occupational therapists should be aware of their own country's policies towards persons with disabilities and rehabilitation, and use their expertise in occupational participation and justice to advocate for their clients at all levels, lobbying governments to change discriminatory policies and minimise the gap between legislation and practice4,22,86,96,97. Our findings indicate the tremendous barriers people face to engage in meaningful occupations; hence, African occupational therapists can be involved in developing broader national policies to reduce such barriers, whether it be policies supporting persons with disabilities to work97 or for extended maternity leave for working mothers29. Talley and Brintnell98 reviewed the barriers to successful implementation of policies for inclusive education for children with disabilities in Rwanda, and the opportunities for occupational therapists to play a role. They found inadequate clarity and enforcement of inclusive education policy as well as limited consideration of cultural context within policies (i.e., focusing on Western-based models), hence they suggest that occupational therapists are well positioned to implement change and should collaborate with government and key community stakeholders to re-operationalise policy and legislation. Understanding national and international policy is also important to ensure that occupational therapy services (current and future) can align with government agendas, such that they are acceptable and supported by local governments29.

As well as advocating for favourable policy for their clients, the findings from this review emphasise the need for raising awareness and advocating for the role and value of occupational therapy as a profession13,99. Healthcare in African countries primarily focuses on curative measures rather than prevention and health promotion; rehabilitation in general, but occupational therapy in particular, is little known and under-prioritised12,79,80,83. Occupational therapists require more funding, resources, and professional support to deliver effective, quality services that can demonstrate their value3,4,23,79,100. Hence, advocating for and developing policies outlining role descriptions, resource allocation, employment positions, and professional development requirements are important considerations for the profession in African contexts.

The role of occupational therapy in Africa related to research

Several authors from the review highlight the necessity of rigorous, reliable, contextually relevant research to inform evidence-based practice (EBP). The Canadian Association of Occupational Therapy defines evidence-based occupational therapy as "client-centred enablement of occupation based on client information and a critical review of relevant research, expert consensus and past experience"101:3. EBP is a professional requirement for all occupational therapists throughout the world and is informed by rigorous research. Buchanan102 argues that EBP is perhaps even more critical for occupational therapists in low-income African countries where knowledge and skills can be limited due to the lack of human resources and professional support23,102. However, simply relying on research from vastly different contexts (i.e., high-income countries) does not necessarily imply effectiveness within the unique African context and there is limited EBP in low-income settings specific to African countries102-104. Research exploring the role and effectiveness of occupational therapy in practice areas particularly pertinent to the African context include HIV/AIDs rehabilitation31,87 and CBR69,105. Additionally, finding appropriate assessment tools can be challenging for African occupational therapists, as most conventional models and assessments are developed in high-income countries, requiring further research to develop and validate contextually-based models and assessment tools42,75,105,106. Currently the only African-developed model (specifically in South Africa) is the Vona du Toit model of Creative Ability which has been used primarily in mental health and vocational rehabilitation107-110.

Research has other important implications for the development and sustainability of occupational therapy in African countries. Further research is needed from the users' perspectives in specific contexts to ensure relevant and effective practice. For example, Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi, Swart, and Soeker interviewed South African adolescents with traumatic brain injuries to understand their perceptions and experiences of high school transition in order to inform the role of occupational therapy, finding "Occupational therapists have a crucial role in fostering an enabling environment (directly and indirectly) through fulfilling various roles including that of a facilitator, intermediary, coach, collaborator, supporter, and advocator" 65:1. Research is also necessary to explore the role of occupational therapists in non-mainstream or role-emerging practice areas (e.g. disaster management, internally displaced people/refugees, human trafficking) to expand the scope and value of occupational therapy specifically in African contexts13,75. Finally, research has a significant bearing on the development of occupational therapy educational programs to design appropriate curriculum, maintain quality standards, and develop partnerships with relevant stakeholders locally and internationally9,111.

Within their EBP competency standards, the WFOT asserts that all occupational therapists need appropriate knowledge, skills, and attitudes to implement EBP, specifically the ability to identify knowledge needs, find relevant sources (including client input), critically appraise evidence and apply it to practice, communicate evidence effectively, and identify research gaps112.

Unfortunately, there can be discrepancy between evidence and practice, often due to the challenges associated with accessing appropriate research evidence34,113. Therefore, research skills are an important component in occupational therapy education in African contexts, and even in countries where research is incorporated as part of standard training (i.e., South Africa), further development is needed103,114. However, Keikelame and Swartz115 also challenge conventional Eurocentric research approaches, arguing for decolonising and culturally appropriate research methodologies through consideration of issues of power, trust, cultural competence, respectful and legitimate practice, and recognition of individual and communities' assets. Given that research is a crucial component in education and practice, stakeholders including students, clinicians and academics as well as managers and policy makers who may be removed from practice and unaware of specific needs, must engage in collaborative research116-118. In addition, several authors recommend international partnerships as an important step to foster quality research and EBP activities through shared resources and expertise, provided there is mutual respect and understanding, clear and ongoing communication, and commitment from both sides119-121.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations to this review. Firstly, although we attempted to incorporate a broad range of literature, it was beyond the scope of this review to include grey literature. A significant amount of African research is not published internationally122,123; however, we only incorporated published material from database searches due to difficulty accessing local information or unpublished documents from a diverse range of countries. Secondly, for pragmatic reasons, we only included English articles; hence we may have missed important literature published in other languages. Thirdly, South African-based research dominated the review, giving a distinct bias towards this specific context, thus our findings may not accurately represent the role of occupational therapy in Africa broadly. Whilst this review covered the role of occupational therapy in Africa from an academic perspective (i.e., published literature), it would be interesting to explore the perspectives of other stakeholders - such as people with disabilities, community members, policy makers, other health professionals, and occupational therapists themselves - on the role of occupational therapy in various African contexts.

Implications for occupational therapy practice

• Occupational therapists have a valuable role in engaging people in meaningful occupations to promote health and quality of life, but context influences the practice approach.

• Community-based practice should be considered a priority for occupational therapy services in African contexts to ensure greater accessibility.

• Focusing on families, communities and collective occupations, beyond the individual client, is also pertinent for occupational therapists in African contexts.

• Advocacy and empowerment are crucial roles for all occupational therapists, but particularly in African contexts where disability can hold greater stigma and exclusion often due to cultural beliefs around disability.

• Occupational therapists could consider commonly held values such as 'ubuntu' to promote inclusion, dignity, and respect for persons with disabilities in African contexts.

• African occupational therapists need appropriate support and resources to embrace a more prominent role in national and international policy development and research.

CONCLUSION

Occupational therapists in African contexts have an important and ambitious role to facilitate engagement in meaningful occupation and optimise quality of life. However, genuine client-centred, holistic practice necessitates that occupational therapists consider their unique cultural context to ensure meaningful and sustainable outcomes whilst maintaining a valuable universal identity. The findings from this review reinforce that African occupational therapists, in particular, should perhaps be more community-orientated and focus on the collective needs and occupations of the family and community as well as the individual. One avenue for advancing community-level occupational therapy services is through CBR and further research is needed to explore the role and effectiveness of occupational therapy in CBR settings. Results from the literature also emphasise the crucial role of advocacy for occupational therapists: both in championing human rights, occupational justice, and inclusion for their clients, as well as promoting the profession itself. In 'Occupational Therapies Without Borders: Integrating Justice with Practice', Garcia-Ruiz discusses an imperative for 'glocalized' occupational therapy (global thinking, local action) affirming that "Occupational therapists are political subjects who are actors who can transform and help in transforming the lives of those with whom they interact"124:192. As well as influencing priorities in practice, the advocacy role compels African occupational therapists to be more involved in policy development and implementation both nationally and internationally. Finally, occupational therapists in African contexts must advance local research initiatives to strengthen EBP and further establish the profession's value and universal relevance. Research is foundational in practice for developing culturally appropriate and effective assessment tools, models, and interventions; in education for developing curriculum and competency standards; and in policy for promoting global standards and reducing gaps between legislation and practice. In all aspects of their role and regardless of context, African occupational therapists require consistent critical reflection and self-awareness, as they work with "humility, enthusiasm and great hope"61:76. Indeed, occupational therapists in African contexts face challenges and responsibility, yet also tremendous opportunities and potential.

Acknowledgments: The first author receives funding from a Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee scholarship. However, the funders had no influence on the research process, writing, or publication. We would also like to sincerely thank the Queen's University Health Sciences librarian, Ms. Paola Durando for all of her time and support in assisting us with database searches for this review.

REFERENCES

1. Occupational Therapy Australia (OTAUS). About Occupational Therapy Australia. 2020. http://aboutoccupationaltherapy.com.au/ [ Links ]

2. World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT). World Federation of Occupational Therapists. 2016. www.wfot.org/ [ Links ]

3. Beguin RB. An overview of occupational therapy in Africa. WFOT Bulletin. 2013; 68: 51 -8. https://doi.org/10.1179/otb.2013.68.1.013 [ Links ]

4. Sherry K. Voices of occupational therapists in Africa. In: Alers VM, Crouch RB, editors. Occupational therapy: an African perspective. Johannesburg, South Africa: Sarah Shorten Publishers; 2010. p. 2647. [ Links ]

5. Alers VM, Crouch RB, editors. Occupational Therapy: An African Perspective: Johannesburg, South Africa: Sarah Shorten Publishers; 2010. [ Links ]

6. Buchanan H, van Niekerk L, Galvaan R. The first WFOT Congress in Africa: History in the making. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 80: 271-2. https://doi.org/10.1179/otb.2011.64.L008 [ Links ]

7. Crouch RB. What makes occupational therapy in Africa different? British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010; 73(10): 445. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12865330218140 [ Links ]

8. Crouch RB. Education and research in Africa: Identifying and meeting the needs. Occupational Therapy International. 2001; 8(2): 139-44. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.141 [ Links ]

9. Agho AO, John EB. Occupational therapy and physiotherapy education and workforce in Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa countries. Human Resources for Health. 2017; 15(37): 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0212-5 [ Links ]

10. Jackson BN, Purdy SC, Cooper-Thomas HD. Role of professional confidence in the development of expert allied health professionals: A narrative review. Journal of Allied Health. 2019; 48(3): 226-32. https://proxy.queensu.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pro-quest.com%2Fdocview%2F2292895586%3Faccountid%3D6180 [ Links ]

11. Ennion L, Rhoda A. Roles and challenges of the multidisciplinary team involved in prosthetic rehabilitation, in a rural district in South Africa. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2016; 9: 565-73. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S116340 [ Links ]

12. Olaoye OA, Emechete AAI, Onigbinde AT, Mbada CE. Awareness and knowledge of Occupational Therapy among Nigerian medical and health sciences undergraduates. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 27: 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hkjot.2016.02.001 [ Links ]

13. Eleyinde ST, Amu V Eleyinde AO. Recent development of occupational therapy in Nigeria: Challenges and opportunities. WFOT Bulletin. 2018; 74(1): 65-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14473828.2018.1426543 [ Links ]

14. Jansen-van Vuuren J, Aldersey HM, Lysaght R. The role and scope of occupational therapy in Africa. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2020: 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1743779 [ Links ]

15. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005; 8(1): 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 [ Links ]

16. World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT). About Occupational Therapy. 2020. https://www.wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy. [ Links ]

17. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). About Occupational Therapy: What is Occupational Therapy? 2020. https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy.aspx. [ Links ]

18. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT). About OT: What is Occupational Therapy? 2020. https://www.caot.ca/site/aboutot/whatisot?nav=sidebar. [ Links ]

19. Occupational Therapy Australia (OTAUS). About Occupational Therapy: What do Occupational Therapists do? 2020. http://aboutoccupationaltherapy.com.au/what-do-occupational-therapists-do/20. [ Links ]

20. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010; 5(69). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [ Links ]

21. Naidoo D, Van Wyk J, Joubert RW. Exploring the occupational therapist's role in primary health care: Listening to voices of stakeholders. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine. 2016; 8(1): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v8i1.1139 [ Links ]

22. Naidoo D, Van Wyk J, Joubert R. Community stakeholders' perspectives on the role of occupational therapy in primary healthcare: Implications for practice. African Journal of Disability. 2017; 6: 25567. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v6i0.255 [ Links ]

23. van Stormbroek K, Buchanan H. Novice therapists in a developing context: Extending the reach of hand rehabilitation. Hand Therapy. 2017; 22(4): 141-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758998317720951 [ Links ]

24. van Niekerk K, Dada S, Tonsing K. Influences on selection of assistive technology for young children in South Africa: perspectives from rehabilitation professionals. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2019;41 (8): 912-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1416500 [ Links ]

25. Assink EMS, Rouweler BJ, Minis M-AH, Hess-April L. How teachers can manage attention span and activity level difficulties due to Foetal Alcohol Syndrome in the classroom: An occupational therapy approach. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009; 39: 10-6. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2310-38332009000300004 [ Links ]

26. Mlambo T, Munambah N, Nhunzvi C, Murambidzi I. Mental Health Services in Zimbabwe - a case of Zimbabwe National Association of Mental Health. WFOT Bulletin. 2014; 70(1): 18-21. https://doi.org/10.1179/otb.2014.70.L006 [ Links ]

27. Shipham I, Pitout SJ. Rheumatoid arthritis: Hand function, activities of daily living, grip strength and essential assistive devices. Curationis. 2003; 26(3): 98-106. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v26i3.857 [ Links ]

28. Stickley A, Stickley T. A holistic model for the rehabilitation and recovery of internally displaced people in war-torn Uganda. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010; 73(7): 335-8. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12759925544461 [ Links ]

29. Visser M, Nel M, la Cock T, Labuschagne N, Lindeque W, Malan A, et al. Breastfeeding among mothers in the public health sector: the role of the occupational therapist. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 46: 65-72. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n2a11 [ Links ]

30. Hansen AMW, Chaki AP, Mlay R. Occupational therapy synergy between Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation Tanzania and Heifer International to reduce poverty. African Journal of Disability. 2013; 2(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v2i1.48 [ Links ]

31. Kamba M, Rugg S. An occupational therapy income-generation group for HIV-positive women in Uganda: Part 2. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2008; 15(2): 74-82. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2008.15.2.28190 [ Links ]

32. Sonday A, Anderson K, Flack C, Fisher C, Greenhough J, Kendal R et al. School based occupational therapists: An exploration into their role in a Cape Metropole Full Service School. The South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 42(1): 2-6. http://www.sajot.co.za/index.php/sajot/article/view/120/70 [ Links ]

33. van der Merwe J, Smit N, Vlok B. A survey to investigate how South African Occupational Therapists in private practice are assessing and treating poor handwriting in foundation phase learners: Part II - Treatment and evaluation practices. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 41: 11-7. http://www.sajot.co.za/index.php/sajot/article/viewFile/106/57 [ Links ]

34. Hepworth LM, Govender P Rencken G. Current trends in splinting the hand in children with neurological impairments. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 47(1). https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/v47n1a4 [ Links ]

35. Teuchert R, de Klerk S, Nieuwoudt HC, Otero M, van Zyl N, Coetzé M. Occupational therapy intervention into osteo-arthritis of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb in the South African context. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 47: 41-5. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/v47n1a8 [ Links ]

36. Buys T. Professional competencies in vocational rehabilitation: Results of a Delphi study. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 45: 48-54. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/v45n3/a9 [ Links ]

37. van Niekerk M. A career exploration programme for learners with special educational needs. Work. 2007; 29(1): 19-24. https://content.iospress.com/articles/work/wor00636 [ Links ]

38. Buys T, van Biljon H. Functional capacity evaluation: An essential component of South Africa occupational therapy work practice service. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation. 2007; 29(1): 31-6. https://content.iospress.com/articles/work/wor00638 [ Links ]

39. Monareng LL, Franzsen D, van Biljon H. A survey of occupational therapists' involvement in facilitating self-employment for people with disabilities. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 48: 52-7. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vol48n3a8 [ Links ]

40. du Toit SH. Using the Model Of Human Occupation to conceptualize an occupational therapy program for blind persons in South Africa. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2008; 22(2-3): 51-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380570801989424 [ Links ]

41. Meissner RJ, Ferguson J, Otto C, Gretschel P Ramugondo E. A play-informed, caregiver-implemented, home-based intervention for HIV-positive children and their families living in low-income conditions in South Africa. WFOT Bulletin. 2017; 73(2): 83-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14473828.2017.1375068 [ Links ]

42. Guidetti S, Söderback I. Description of self-care training in occupational therapy: Case studies of five Kenyan children with cerebral palsy. Occupational Therapy International. 2001; 8(1): 34-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/M823869/ [ Links ]

43. Govender K, Christopher C, Lingah T. The role of the occupational therapist in case management in South Africa. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 48: 12-9. https://doi.org/10.17159/23103833/2018/vol48n2a3 [ Links ]

44. Bunning K, Gona JK, Odera-Mung'ala V Newton CR, Geere JA, Hong CS, et al. Survey of rehabilitation support for children 0-15 years in a rural part of Kenya. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2014; 36(12): 1033-41. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.829524 [ Links ]

45. Chikwanha TM, Chidhakwa S, Dangarembizi. Occupational therapy needs of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy in Zimbabwe: Caregivers' perspectives. The Central African Journal of Medicine. 2015; 61(5-8): 38-44. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e1d4/733f182e6d2a228d58ae22e02a91f2a67f40.pdf [ Links ]

46. van Biljon H. Occupational therapists in medico-legal work - South African experiences and opinions. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013; 43(2): 27-33. http://www.sajot.co.za/index.php/sajot/article/view/190/111 [ Links ]

47. Awaad J. Culture, cultural competency and occupational therapy: A review of the literature. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2003; 66(8): 356-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260306600804 [ Links ]

48. Hocking C. The challenge of occupation: Describing the things people do. Journal of Occupational Science. 2009; 16(3): 140-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686655 [ Links ]

49. Watson RM. Being before doing: The cultural identity (essence) of occupational therapy. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2006; 53(3): 151-8. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00598.x [ Links ]

50. Crouch RB. The relationship between culture and occupation in Africa. In: Alers VM, Crouch RB, editors. Occupational Therapy: an African perspective. Johannesburg, South Africa: Sarah Shorten Publishers; 2010. p. 50-9. [ Links ]

51. Beagan BL. Approaches to culture and diversity: A critical synthesis of occupational therapy literature. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 82(5): 272-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417414567530 [ Links ]

52. Hammell KRW. Sacred texts: A sceptical exploration of the assumptions underpinning theories of occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009; 76(1): 6-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740907600105 [ Links ]

53. Hammell KRW. Occupation, well-being, and culture: Theory and cultural humility. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013; 80(4): 224-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417413500465 [ Links ]

54. Kantartzis S, Molineux M. The Influence of Western Society's Construction of a Healthy Daily Life on the Conceptualisation of Occupation. Journal of Occupational Science. 2011; 18(1): 62-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2011.566917 [ Links ]

55. Reid HAJ, Hocking C, Smythe L. The making of occupation-based models and diagrams: History and semiotic analysis. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019; 86(4): 313-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419833413 [ Links ]

56. Turpin M, Iwama MK. Using occupational therapy models in practice: A fieldguide. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier; 2011. [ Links ]

57. Gerlach AJ, Teachman G, Laliberte-Rudman D, Aldrich RM, Huot S. Expanding beyond individualism: Engaging critical perspectives on occupation. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 25(1): 35-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2017.1327616 [ Links ]

58. Bonikowsky S, Musto A, Suteu KA, MacKenzie S, Dennis D. Independence: An analysis of a complex and core construct in occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 75(4): 18895. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802212X13336366278176 [ Links ]

59. Crouch RB. The impact of poverty on the service delivery of occupational therapy in Africa. In: Alers VM, Crouch RB, editors. Occupational Therapy: an African perspective. Johannesburg, South Africa: Sarah Shorten Publishers; 2010. p. 98-110. [ Links ]

60. Nolte A, Downing C. Ubuntu-the essence of caring and being: A concept analysis. Holist Nurs Pract. 2019; 33(1): 9-16. https://doi.org/10.1097/hnp.0000000000000302 [ Links ]

61. Sherry K. Culture and cultural competence for occupational therapists in Africa. In: Alers VM, Crouch RB, editors. Occupational Therapy: an African perspective. Johannesburg, South Africa: Sarah Shorten Publishers; 2010. p. 60-77. [ Links ]

62. Mahoney WJ, Kiraly-Alvarez AF Challenging the status quo: Infusing non-western ideas into occupational therapy education and practice. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019; 7(3): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1592 [ Links ]

63. Ramugondo EL, Kronenberg F. Explaining collective occupations from a human relations perspective: Bridging the individual-collective dichotomy. Journal of Occupational Science. 2015; 22(1): 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2013.781920 [ Links ]

64. Chikwanha TM. Exploring factors shaping family involvement in promoting the participation of adults with substance use disorders in meaningful occupations [dissertation]. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Stellenbosch University; 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/105954 [ Links ]

65. Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi L-A, Swart E, Soeker MS. A service user perspective informing the role of occupational therapy in school transition practice for high school learners with TBI: An African perspective. Occupational Therapy International. 2019: 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1201689 [ Links ]

66. Fewster DL, Uys C, Govender P Interventions for primary caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder: A cross-sectional study of current practices of stakeholders in South Africa. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2020; 50(1). https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2020/vo150no1a7 [ Links ]

67. Bushby K, Chan J, Druif S, Ho K, Kinsella EA. Ethical tensions in occupational therapy practice: A scoping review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 78(4): 212-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022614564770 [ Links ]

68. Iemmi V Gibson L, Blanchet K, Kumar KS, Santosh R Hartley S, et al. Community-based rehabilitation for people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2016; 11(15): 368-87. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2015.15 [ Links ]

69. M'kumbuzi VRP Myezwa H. Conceptualisation of community-based rehabilitation in Southern Africa: A systematic review. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2016; 72(1): 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajp.v72i1.301 [ Links ]

70. Occupational Therapy Association of South Africa (OTASA). OTASA Position statement on rehabilitation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 47(3): 53-4. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/v47n3a10 [ Links ]

71. World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT). Position statement on Community Based Rehabilitation. 2004. https://wfot.org/resources/community-based-rehabilitation [ Links ]

72. Geberemichael SG, Tannor AY Asegahegn TB, Christian AB, Vergara-Diaz G, Haig AJ. Rehabilitation in Africa. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 2019; 30(4): 757-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2019.07.002 [ Links ]

73. Sinclair K, Fransen H, Sakellariou D, Pollard N, Kronenberg F. Reporting on the WFOT-CBR master project plan: the data collection subproject. WFOT Bulletin. 2006; 54(1): 37-45. https://doi.org/10.1179/otb.2006.54.L006 [ Links ]

74. Jejelaye AO. Intergration of occupational therapy services at primary healthcare level in South Africa [dissertation]. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand; 2019. https://hdl.handle.net/10539/28217 [ Links ]

75. Witchger Hansen AM, Blaskowitz M. From dependence to interdependence: A holistic vocational training program for people with disabilities in Tanzania. Annals of International Occupational Therapy. 2018; 1(3): 157-68. https://doi.org/10.3928/24761222-20180926-01 [ Links ]

76. Ndlovu T, Chikwanha TM, Munambah N. Learning outcomes of Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy students during their community-based education attachment. African Journal of Health Professions Education. 2017; 9(4): 189-93. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2017.v9i4.958 [ Links ]

77. Naidoo D, Van Wyk J, Waggie F. Occupational therapy graduates' reflections on their ability to cope with primary healthcare and rural practice during community service. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 47(3): 39-45. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/v47n3a7 [ Links ]

78. Richards L-A, Galvaan R. Developing a socially transformative focus in Occupational Therapy: Insights from South African practice. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 48(1): 3-8. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vo148n1a2 [ Links ]

79. Bateman C. 'One size fits all' health policies crippling rural rehab - therapists. South African Medical Journal. 2012; 102(4): 200-8. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/samj/v102n4/06.pdf [ Links ]

80. Ned L, Cloete L, Mji G. The experiences and challenges faced by rehabilitation community service therapists within the South African Primary Healthcare health system. African Journal of Disability. 2017; 6: 311. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v6i0.311 [ Links ]

81. Watson R, Duncan EM. The 'right' to occupational participation in the presence of chronic poverty. WFOT Bulletin. 2010; 62(1): 2632. https://doi.org/10.1179/otb.2010.62.L006 [ Links ]

82. World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT). Position statement on human rights. 2019. https://wfot.org/resources/occupational-therapy-and-human-rights [ Links ]

83. Hammarlund S. An occupational therapy needs assessment for an organization attending to children with autism spectrum disorder in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 2015. http://hj.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:854443/FULLTEXT01.pdf [ Links ]

84. Ngubane-Mokiwa SA. Ubuntu considered in light of exclusion of people with disabilities. African Journal of Disability. 2018; 7: 460. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v7i0.460 [ Links ]

85. Wegner L, Rhoda A. The influence of cultural beliefs on the utilisation of rehabilitation services in a rural South African context: Therapists' perspective. African Journal of Disability. 2015; 4(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v4i1.128 [ Links ]

86. Reynolds S. Disability culture in West Africa: Qualitative research indicating barriers and progress in the greater Accra region of Ghana. Occupational Therapy International. 2010; 17(4): 198-207. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.303 [ Links ]

87. Sherry K, Martin IZ. HIV occupational performance and the role of occupational therapy. In: M. AV, Crouch RB, editors. Occupational Therapy: an African perspective. Johannesburg, South Africa: Sarah Shorten Publishers; 2010. p. 232-50. [ Links ]

88. van der Reyden D, Joubert R Christopher C. HIV/AIDS in psychiatry and issues facing occupational therapists regarding practice: Moral and ethical dilemmas. In: Crouch RB, Alers VM, editors. Occupational Therapy in Psychiatry and Mental health. 5th ed. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. p. 85-105. [ Links ]

89. Gamieldien F, van Niekerk L. Street vending in South Africa: An entrepreneurial occupation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 47(1): 24-9. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vo147n1a5 [ Links ]

90. Wegner L, Behardien A, Loubser C, Ryklief W, Smith D. Meaning and purpose in the occupations of gang-involved young men in Cape Town. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 46(1): 53-8. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n1a11 [ Links ]

91. Davies L. Current occupational therapy and physiotherapy practice in implementing home programmes for young children with cerebral palsy in South Africa [Master's thesis]. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand; 2016. http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10539/21369/_Lauren%20Davies%200418620%20M%20IMPLEMENTING%20HOME%20PRO-GRAMMES%20FOR%20YOUNG%20CHILDREN%20WITH%20CEREBRAL%20PALSY%20%20.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1 [ Links ]

92. Hammell KW. Participation and occupation: The need for a human rights perspective. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 82(1): 4-5. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417414567636 [ Links ]

93. Hocking C, Townsend E. Driving social change: Occupational therapists' contributions to occupational justice. WFOT Bulletin. 2015; 71(2): 68-71. https://doi.org/10.1179/2056607715Y.0000000002 [ Links ]

94. Lencucha R, Shikako-Thomas K. Examining the intersection of policy and occupational therapy: A scoping review. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy (1939). 2019; 86(3): 185-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419833183 [ Links ]

95. Chichaya TF Joubert RWE, McColl MA. Analysing disability policy in Namibia: An occupational justice perspective. African Journal of Disability. 2018; 7: 401-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v7i0.401 [ Links ]

96. Govender R, Govender P Mpanza D. Medical incapacity management in the South African private industrial sector: The role of the occupational therapist. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019; 49: 31-7. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2019/vo149n3a6 [ Links ]

97. Mavindidze E, van Niekerk L, Cloete L. Inter-sectoral work practice in Zimbabwe: Professional competencies required by occupational therapists to facilitate work participation of persons with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2019: l-ll. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2019.1684557 [ Links ]

98. Talley L, Brintnell ES. Scoping the barriers to implementing policies for inclusive education in Rwanda: An occupational therapy opportunity. International Journal of Inclusive Education. 2016; 20(4): 364-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1081634 [ Links ]

99. Lamb AJ, Metzler CA. Defining the value of Occupational Therapy: A health policy lens on research and practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 68(1): 9-14. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.681001 [ Links ]

100. van Stormbroek K, Buchanan H. Community service occupational therapists: Thriving or just surviving? South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 46: 63-72. https://dx.doi.org/10.17159/23103833/2016/v46n3a11 [ Links ]

101. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT). Joint position statement on evidence-based Occupational Therapy. Ottawa, Canada; 1999. https://www.caot.ca/document/3697/J%20%20Joint%20Position%20Statement%20on%20Evidence%20based%20OT.pdf [ Links ]

102. Buchanan H. The uptake of evidence-based practice by occupational therapists in South Africa. WFOT Bulletin. 2011; 64(1): 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1179/otb.2011.64.L008 [ Links ]

103. Pitout H. Research orientation of South African occupational therapists. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013; 43: 5-11. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1759952564/ [ Links ]

104. Nhunzvi C, Mavindidze E. Occupational Therapy Rehabilitation in a Developing Country: Promoting Best Practice in Mental Health, Zimbabwe. Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR). 2016; 2(12): 685-91. https://www.academia.edu/34325446/Occupational_Therapy_Rehabilitation_in_a_Developing_Country_Promoting_Best_Practice_in_Mental_Health_Zimbabwe [ Links ]

105. Fransen H. Challenges for occupational therapy in community-based rehabilitation: occupation in a community approach to handicap in development. In: Kronenberg F, Algado Simo S, Pollard N, editors. Occupational Therapy without borders: Learning from the spirit of survivors. Churchill Livingstone, UK: Elsevier; 2005. p. 165-79. [ Links ]

106. Owen A, Adams F Franszen D. Factors influencing model use in occupational therapy. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 44(1): 41-7. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/sajot/v44n1/09.pdf [ Links ]

107. Casteleijn D, de Vos H. The Model of Creative Ability in vocational rehabilitation. Work. 2007; 29: 55-61. https://content.iospress.com/articles/work/wor00641 [ Links ]

108. Casteleijn D. The use of core concepts and terminology in South Africa. WFOT Bulletin. 2012 ;65(1): 20-7. https://doi.org/10.1179/otb.2012.65.L005 [ Links ]

109. de Bruyn M, Wright J. Joining the dots: Theoretically connecting the Vona du Toit Model of Creative Ability (VdTMoCA) with supported employment. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 20l7; 47: 49-52. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/v47n2a9 [ Links ]

110. de Witt P Creative ability: A model for individual and group occupational therapy for clients with psychosocial dysfunction. In: Crouch R, Alers, Vivyan, editors. Occupational Therapy in Psychiatry and Mental Health. 5th ed. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. p. 3-32. [ Links ]

111. Olsen M, Wilson A, Beeson J. Developing a curriculum in occupational therapy for Zambia. WFOT Bulletin. 2016; 72(2): 71-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/14473828.2016.1227653 [ Links ]

112. World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT). Evidence-based practice competency standards for Occupational Therapists. 2014. http://www.wfot.org/ResourceCentre.aspx [ Links ]

113. Van Rensburg ZJ. Occupational therapy practice used for children diagnosed with a dual diagnosis of cerebral palsy and visual impairment in South Africa [Master's thesis]. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand; 2016.. http://hdl.handle.net/10539/21397 [ Links ]

114. Schoonees A, Rohwer A, Young T. Evaluating evidence-based health care teaching and learning in the undergraduate human nutrition; occupational therapy; physiotherapy; and speech, language and hearing therapy programs at a sub-Saharan African academic institution. PLoS ONE. 2017; 12(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172199 [ Links ]

115. Keikelame MJ, Swartz L. Decolonising research methodologies: Lessons from a qualitative research project, Cape Town, South Africa. Global Health Action. 2019; 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1561175 [ Links ]

116. du Toit S, Wilkinson A. Publish or perish: A practical solution for research and publication challenges of occupational therapists in South Africa. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009; 39: 2-7. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/sajot/v39n1/02.pdf [ Links ]

117. Buys T. Professional competencies in occupational therapy work practice: What are they and how should these be developed? Work. 2007; 29(1): 3-4. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b6c9/3ac48ffaa9f2cc355e1f1a3b80ee126bccf2.pdf [ Links ]

118. Vermaak ME, Nel M. From paper to practice - academics and practitioners working together in enhancing the use of occupational therapy conceptual models. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016; 46: 35-40. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2016/v46n3a7 [ Links ]

119. Boum li Y Burns BF Siedner M, Mburu Y Bukusi E, Haberer JE. Advancing equitable global health research partnerships in Africa. BMJ Global Health. 2018; 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000868 [ Links ]

120. Coker-Bolt P Ramey SL, DeLuca S. Promoting evidence-based practices abroad: Developing a constraint-induced movement therapy program in Ethiopia. OT Practice. 2016; 21(2): 21-3. https://search-proquest-com.proxy.queensu.ca/docview/1771409807/fulltextPDF/8F06DF4DD2B347BFPQ/1?accountid=6180 [ Links ]

121. Njelesani J, Stevens M, Cleaver S, Mwambwa L, Nixon S. International research partnerships in occupational therapy: a Canadian-Zambian case study. Occupational Therapy International. 2013; 20(2): 78-87. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1346 [ Links ]

122. Tarkang EE, Bain LE. The bane of publishing a research article in international journals by African researchers, the peer-review process and the contentious issue of predatory journals: A commentary. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2019; 32: 119. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2019.32.119.18351 [ Links ]

123. Tijssen R, Kraemer-Mbula E. Research excellence in Africa: Policies, perceptions, and performance. Science and Public Policy. 2018; 45(3): 392-403. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipo1/scx074 [ Links ]

124. Garcia-Ruiz S. Occupational Therapy in a Glocalized World. In: Sakellariou D, Pollard N, editors. Occupational Therapies Without Borders: Integrating Justice with Practice. 2 ed. HS, USA: Elsevier 2017. p. 185-93. [ Links ]

125. Bell T, Wegner L, Blake L, Jupp L, Nyabenda F Turner T. Clients' perceptions of an occupational therapy intervention at a substance use rehabilitation centre in the Western Cape. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 45(2). https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2015/V45N2A3 [ Links ]

126. Birkhead S. An occupational therapy programme in a religious community in South Africa: A historical narrative. Occupational Therapy International. 2011; 18(1): 59-66. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.313 [ Links ]

127. Ramano E, Buys T. Occupational therapists' views and perceptions of functional capacity evaluations of employees suffering from major depressive disorders. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 48: 9-15. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vol48n1a3 [ Links ]

128. Smit J, de Jongh JC, Cook RA. The facilitators and barriers encountered by South African parents regarding sensory integration occupational therapy. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 201 8; 48: 44-51. https://doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2017/vo148n3a7 [ Links ]