Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.50 n.1 Pretoria Apr. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2020/vol50n1a6

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Being a mother of a child with HIV-related Neurodevelopmental Disorders in the Zimbabwean Context

Nyaradzai MunambahI; Pam GretschellII; Amshuda SondayIII

IBSc. OT (UZ), MSc OT (UCT). Lecturer: Department of Rehabilitation, College of Health Sciences, University of Zimbabwe. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0957-3783

IIB OT (US), M ECI (UP), PhD (UCT). Senior Lecturer: Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7890-363

IIIBSc OT (UWC), M ECI (UP), PhD (UCT). Senior Lecturer: Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9973-7413

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: There is a growing population of mothers caring for their biological children who are infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), in Zimbabwe. Many of these children present with HIV-related Neuro Developmental Delays (NDDs). The occupation of being a mother is a complex and multifaceted role geared towards caring for and nurturing children. The different ways in which mothers negotiate the unique circumstances linked to the occupation of being a mother to a child with diagnosis of HIV-related NDDs warrants exploration.

AIM: The aim of the study was to describe the mother's experiences of engaging in daily occupations relating to caring for their child with HIV-related NDDs.

METHODOLOGY: A descriptive qualitative study using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach was used to uncover the mothers' lived experiences of caring for their child with HIV-related NDDs. Data generated from phenomenological interviews conducted with five mothers were analysed inductively using a simplified version of the StevickColaizzKeen method

FINDINGS: Two major themes, namely 'Ndozvazviri' (Resilient Acceptance) and 'Rekindled hope for the future' emerged from the findings. These themes revealed that caring for a child with HIV-related NDDs is a difficult and demanding role. Despite this, mothers accepted and found meaning in this caring role. Their meaning was expressed through the opportunity to care for their own child and to observe their progress in occupational development and engagement. These interactions created positive experiences for the mothers and rekindled their hope for the future of their child.

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS: Despite the huge demands associated with being a mother of a child with HIV-related NDDs, mothers were committed to this role and were reluctant to entrust this role to others. The findings of this study encourage occupational therapists designing interventions for families, to carefully consider how the mothering role positively shapes the identities of mothers caring for children with HIV-related NDDs.

Key words: mothering, HIV-related NDDs, caregiver

INTRODUCTION

The academic discipline of occupational science supports the exploration of occupational roles in order to increase our understanding of identity and the daily activities that are associated with these roles1. The occupational role of mothering is defined as a social practice geared toward nurturing and caring for dependent children2. It is a complex and dynamic role in which mothers devote their time to caring for children as well as being involved in other occupations geared to meet the demands of being a mother3. Caring for children constitutes an opportunity for mothers to generate meaning and construct their individual identity as a mother and carer of the child4.

Research in the profession of occupational therapy and the academic discipline of occupational science has focused on describing the lived experiences of mothers caring for their children with various physical and mental disabilities3,5,6. These studies report that caring for a child with a disability impacts on a mother's occupation in different ways. A study by Bourke-Taylor et al5, highlighted that some mothers developed emotional distress and mental health problems that affected their day to day functioning. At the time of this study, there had been no exploration of the experiences of mothers caring for their HIV positive children who have Neuro-developmental Delays (NDDs).

Prior to the onset of medical interventions in the form of An-tiretroviral Therapy (ART) / Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) it was common for most carers of HIV infected children in Africa to be either grandmothers, siblings or extended family members because most biological mothers would have died or would have been too ill as a result of their own HIV/AIDS diagnosis7. Advances in healthcare practices for HIV/AIDS, linked to the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART/HAART), have increased the life expectancy and quality of life of HIV infected people. Thus, parents of children with HIV are now able to continue with their role of caring for their children.

The diagnosis of a child as HIV positive almost always means that at least the mother (and possibly, the father) is also infected8. This makes caring for an HIV infected child by a biological mother unique because the mother has to deal with her own diagnosis, and the possibility that both the child and their partner/s have the disease as wel19. Many mothers only learn about their HIV status at the time that they find out that they are pregnant. They deal with feelings of shock, anxiety, fear and guilt linked to this discovery10.

The stigma linked to a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS adds an additional layer to the burden of care, compelling mothers to deal with the tension between the preference for secrecy surrounding the disease9 and the openness required for them to access health and educational services for their child and seek and accept social support11. In Burkina Faso, Hejoaka9 explored the life experiences of being a mother of a child with HIV/AIDS. The study findings revealed that often HIV positive mothers tend to silence their own needs and attend to the needs of their children. In most instances, the mothers ignore their physical, psychological and social needs and/or seek services and support late, thus negatively impacting on their own general health and, consequently, the health of their child. These unique challenges, related to the caregiving experience, motivate the need for an inquiry into the lived experiences of mothers caring for their own children with HIV-related NDDs. This paper aims to explore how personal and contextual factors shaped the occupation of caring for a child with HIV The research is located in Zimbabwe12**, the home country of the researcher, where 9.4% of children contracting HIV from their mothers are at risk of developing NDD in Zimbabwe13.

METHODOLOGY

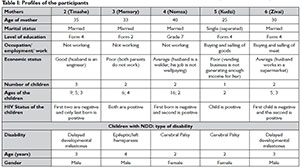

A descriptive qualitative study using a hermeneutic phenomenologi-cal approach was employed in this study as it allows the researcher to elicit and understand how the phenomenon of being a caregiver of a child with a HIV-related neurodevelopmental disorder is lived and experienced14. Qualitative research provides individuals with a voice to relay their unique experiences in a way that they can be well represented and understood15. Mothers were recruited from the Harare Hospital Children's Rehabilitation Unit (CRU), the country's largest referral unit for children with disabilities in Zimbabwe. Through the assistance of the administrator, children whose biological mothers were registered as primary caregivers were identified and listed and using purposive sampling, a list of fourteen mothers who met the selection criteria was obtained. Using the maximum variation criteria, five mothers who had different marital statuses, economic backgrounds and had different numbers of children were selected for the study. See table 1 below for profiles of the participants). All the mothers agreed to the use of pseudonyms during the study. On the initial appointment, the researcher explained the details of the study to mothers. This allowed the mother to make an informed choice as to whether or not to consent to participate in the study.

All the selected and contacted mothers agreed to take part in the study. For each mother, three indepth interviews of 60-90 minute durations were used to capture the experiences and the feelings of mothers from their point of view. Interviews were guided by open-ended questions, linked to the study objectives and information gained from the literature review.

Mothers were given the option to be interviewed in the language they were most comfortable in. All mothers chose their home language Shona (the researcher is also fluent in this language). The first interview transcripts were translated to English and analysed before the second interviews took place. This allowed the researcher to gradually uncover provisional themes within the phenomenological interviews and guided the direction of the second interviews16. The third interview sessions were carried out for member checking purposes to increase credibility, clarification and further explanations from participants17. During the process of member checking, a combination of analysed data from both interview one and two were brought to the mothers, who in turn reviewed it to ensure that the findings were a true reflection of what they had said. All the mothers agreed that the data were true reflections of their caring experience of coping with a HIV positive NDD child.

Data analysis was guided by a simplified version of the Stevick-ColaizzKeen method detailed in Creswell18 and Moustakas19. Steps for data analysis included bracketing, familiarisation, horizontalisa-tion, textual description, structural description and the overall essence of the caring experience. The data analysis procedure followed an iterative process whereby the researcher moved between the different steps of the analysis to eventually describe the mothers' experiences of caring for their HIV positive child with NDD.

This study received ethical clearance from the University of Cape Town, Department Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC REF: 182/2013) before data collection commenced. In Zimbabwe, where the data were collected, the Medical Research Council also reviewed the study and approval was granted (MRCZ/B/501). The permission to carry out the study at Harare Central Hospital (CRU) was sought from the hospital administrative offices. Records of children with HIV-related neurodevelopmental disorders were sourced from the Harare Central Hospital Children's Rehabilitation Unit's administration office.

FINDINGS

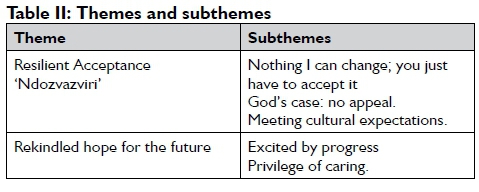

Two major themes emerged: Resilient Acceptance 'Ndozvazviri' and "Rekindled hope for the future". (See Table 2 below for the themes and subthemes). These two themes will be presented below drawing on the sub-themes to support the description of each theme.

Theme One: 'Ndozvazviri' (Resilient acceptance)

The first theme 'Ndozvazviri' describes how the mothers were consistent in adapting to the multiple and significant sources of stress they encountered during the process of firstly finding out their own positive HIV status and then the HIV positive status of the child; followed soon thereafter by a growing realisation that their child was not developing typically because of an HIV-related NDD, and then also facing the prospect of the long term dependence of their child on them.

The mothers were devastated and described in detail their traumatic experiences of receiving the news of their own HIV positive status and that of their children,

I was so devastated...! was just a worrying mother. (Zivai)

I was so devastated; such issues are worrisome in life. (Kudzi)

The sub-theme Nothing I can change; you just have to accept it, however captures their commitment to accepting the responsibility they held for the care of their child.

There is nothing I can change! His pregnancy came without being planned. I thought I was gaining weight until my husband advised me to go to the clinic. I went there and the reports from scan showed that I had a three months old pregnancy. I walked away from that place and I said to myself whatever.. .(Tinashe)

The word 'whatever' here is a close translation of the Shona phrase 'chero zvazvaita' which portrays a sense of despair and confusion. It describes the essence of Tinashe's helplessness, of not knowing how to handle this situation, or what to do.

In all the cases, the whole experience of having a child with HIV-related NDD was never imagined or thought of.

My son just woke up one day with a hot temperature. I did not understand what it was. I took him to hospital and the doctors did their stuff assuming that it was meningitis and what they were saying I do not know much about it. I don't know much about that. So I stayed with him in hospital then was later discharged after 3 weeks. He could not sit, he could not walk or do anything and he had fits, he is now epileptic. And to think of it that he is also HIV positive...I just didn't know what else to do. (Memory)

The doublebarrelled condition of the child being HIV positive, as well having a NDD, resulted in the mothers experiencing mothering as a role consisting of all-consuming, difficult and demanding tasks. The mothers spoke of how the caring role for the child with NDDs was different from that of their other children because of their increased levels of dependence on their mothers for a wider array of activities than the other siblings.

Caring for him is different from other children, it is much more demanding because my child cannot do most of the things alone like other four year olds whom you can send to go and fetch water and they go. (Tinashe)

She (his sister) could go to the toilet but he (the child) cannot. He needs me all the time. (Zivai)

The mothers however demonstrated resilience in the face of these multiple negative insults. They described how they needed to come to terms with the fact that their child had HIV/AIDS. This was a situation that was not going to change, and thus it was best to accept their situations and move on with life. Their resilience, reflected in their ability to accept, adapt and respond to these many demands is evident in the quotes below:

I did not panic, because already I knew my child was HIV positive and anything could happen. I just told myself that this is the way it just supposed to be (Zvazviri ndozvazviri). (Memory)

It was difficult for me to accept it. What else can you do? But you just have to accept it. (Nomsa)

There is nothing I can change.. ndozvazviri.. .just have to accept it. (Zivai)

The term 'ndozvazviri' is widely used in the Shona language. It signifies a very difficult situation that one encounters and has no power to change. In response, the individual has to accept the situation as it is, as nothing can be done to change it.

All the mothers who participated in this study were Christian. Their belief in God contributed to their acceptance of the condition of the child and their caring role. This is represented in the sub-theme God's case, no appeal. Mothers believed that whatever God would have done was final and no one had the power to change it. Having a child with HIV-related NDD was in accordance with God's plan. The mothers thus felt this was reason enough to accept their situation as is.

Nomsa who, after spending 12 years trying to have a baby, eventually gave birth to a child who developed an HIV-related neurodevelopmental disorder. She believed that this was God's will:

I used to cry that why was I given one child, should I stay with only one. If only God was to see and bless me with another child and it happened ... Aaah ...am happy with that, I have to be, God gave, to whom could it had been done to.

Most of the mothers also held the belief that a child is a blessing from God. Because the mothers have been blessed with a child, no matter his/her condition, they could not complain or reject a blessing from God. Mothers drew their strength and energy from spirituality. In some difficult situations mothers narrated how they would ask for God's intervention; which no man could change or go against. The personal connection with a superior being brought comfort, hope and strength to continue with the occupation of caring for a child with HIV-related NDD.

She (her child) got admitted to hospital and doctor said an operation has to be done because her intestines are not functioning very well. I prayed to God. I was praying every day and God heard me. (Tinashe)

Although the mothers had a high regard for the power of their God, some mothers highlighted that they did not have trust in the church. Mothers felt that disclosing their status and that of their children would make them vulnerable to stigma from family, friends and the community.

The church is just the same as in the location (suburb), like at church it depends if pastor's wife can keep a secret because you can tell her and she discloses to people. (Kudzi)

Mothers who participated in this study shared the Shona culture, a culture which gives the responsibility of caring for others, especially children, to the mothers.

The sub-theme Meeting cultural expectations captures how cultural expectations contributed to their committed approach to caring for their child.

"It is not easy but I am the mother. I have to do it." (Nomsa)

The experience of getting to know about their HIV status as well as the NDD condition of the child was difficult for the mothers and there was a feeling of resigned acceptance 'ndozvazviri' (That is the way it is). The belief in God as a spiritual being and the anchoring foundation of their culture played a role in guiding mothers to this resigned acceptance.

Theme Two: "Rekindled hope for the future"

The second theme of 'Rekindled hope for a future', unpacks the positive and gratifying aspects of the mothers' experiences of their caregiving occupation. These included instances where mothers, while caring for and playing with their children, noted improvements in the developmental milestones and overall health of the child. Mothers expressed that taking care of their children was something very important and meaningful to them and they would want to continue doing it.

The sub-theme Privilege of caring reflects the mothers' positive attitudes towards their caregiving role despite this being a role associated with many challenges.

What I value most is caring for my child as well as planning for his future. Like any other child, you would want to be able to take good care of him, see him grow, go to school and have a better life. (Zivai)

Because it is just so difficult to take care of such a child in such a condition and being able (to do so) is so important to me. (Nomsa)

Mothers valued the times and opportunities for engagement and participation in play of the child. It was important for the mothers to set time aside to play with their child. Mothers eagerly shared their experiences of engaging in play with their child. Two of the mothers reported that they felt happy to watch the child play safely with siblings or other children in the community. Watching their children being included in play with other children brought a sense of happiness and joy to the mothers. This could be linked to the sense of belonging the mothers experienced because their child was doing what other children in the community were doing, despite the disability.

I was happy to watch my child play with others. He can now safely play with others. You see that he has a lot of potential and it is beginning to show. (Memory).

Excited by progress

The privilege to care for their children allowed them to note the progress of the child and the positive changes happening in the child, which brought a sense of joy, hope and relief to the mothers. This applied even more when the mothers had experienced situations where they had been told their child would not able to do anything in life or that the child's life expectancy would not be long. As the child showed progress, emotions of grief, sorrow and despair were complemented with hope for the future.

I am just happy with the improvements I am noticing. Yes I feel so happy because you know if you are in closed doors and you hear doctors saying this and that and on top of that, he (the child) got tested and found to be HIV positive. (I) ...would say now he is an invalid cabbage, he won't do anything in life. So now with the improvements I feel so happy. (Memory)

Some of the mothers had heard of various myths and beliefs that a child with HIV and disability had a short life expectancy. These beliefs worried the mothers and made them uncertain of the future of their children. In one of the interviews, Nomsa mentioned that she had been told that children infected with HIV die before the

These days I am celebrating the fact that my child is able to say a word mama...huya (mom... come) what an improvement! (Memory)

I am excited! At first he could not do anything but now he is able to do this (bringing hands together) so now he can hold things. (Nomsa)

Their child's improved ability to initiate and do activities alone meant a lot to the mothers especially when a child had not been able to do anything before. Noticing the child achieving a new 'doing' - no matter how big or small, good or bad - these mothers cherished every 'doing' of their child with happiness. These small tasks included the child bringing two hands together, eating alone, playing, saying a word or even choosing what they wanted to wear. Also, engagement and participation of the child in play was a key factor that brought relief and excitement to the mothers. This could have been attributed to the fact that, engaging in play, for both children and adults, is identified in the Shona culture as a significant measure of health and wellbeing in children. If a sick child was still able to engage in play, then nature of illness was not viewed as serious. Shona nurses also use play as a yardstick to determine the severity of illness and often nurses ask mothers if the child is playing when they take case histories. Engagement in play for a child with NDD signified a sense of health and well-being, thus, mothers were excited when their children engaged in play.

What excites me is that my child can play, he enjoys playing even with other children. (Zivai)

Despite the negative moments described by the mothers about caring for a child with HIV-related NDDs, they also reported experiencing some positive moments. The positive experiences mainly occurred when mother noticed progress in the child as well as when playing with the child. Progress in the child rekindled hope in the mother and it brought some sense of joy and excitement. Also, instances when the child was able to engage in play and do as other children would be doing add to the positive experience of the mothers.

DISCUSSION

Caregiving occupations presented challenges and opportunities which mothers used to create and transform their lives, pursue aims, overcome barriers, learn new ways of achieving health and happiness and also discover their purpose in life20. Wilcock21 supports the notion that people engage in occupations that are meaningful. However, there can be situations where mothers engaged in the caring occupation, not because it was meaningful to them, but where the occupation has been forced by circumstance. In this study some mothers reported that the pregnancy was not planned and to those who had planned to have a child, no one hoped for a child with HIV-related NDD. Despite these challenges mothers committed to their role as caregivers and found meaning through engagement in this role over time.

What people do is shaped by the context and the external structures of society that shape the individual's aspirations, expectations and lifestyle4,22. This emphasises the need to consider not only the individual but also the impact of the environment when striving to understand the occupational engagement of people23. The caring experience of the mothers could not be described outside of the influence of their contexts. The mothers described the trauma linked to the process of discovering their own HIV status, the HIV status of their child and then the child's diagnosis of NDD. Despite the impact of various environmental factors (discussed below) on their ability to deal with this trauma, it also supported their ability to meet challenges of their care giving role.

Culture is an occupational determinant which shapes what people do24 and how they experience their engagement in meaningful occupations. In this study the mothers' experiences of caring for their children were guided by the sociocultural norms of the Shona culture25, a culture that dictates the implicit rules and expectations of being a good mother. The Shona culture gives the responsibility of caring for children, to mothers. Mothers are expected to be the custodians of children and answerable to health issues of the child. The mothers in this study strongly aligned themselves with the expectations of the Shona culture and took on the responsibility of caring for their child with HIV-related NDD with diligence. The mothers' motivation to care was fuelled by their cultural obligations26.

Despite accepting and undertaking the caring role, mothers often experienced situations that brought despair. God was viewed as a source of inspiration, comfort and hope for the future in these times, usually during a period of illness of the child. Similar to a study on early responses of HIV positive mothers to the birth of a HIVexposed infant10, the mothers prayed and depended on God during stressful moments. The mothers were at times ambivalent toward the church as an entity of support. Demmer's27 study, based in South Africa, reported that while caregivers attended church they did not receive support from the church. Their fear of stigma and lack of trust in church personnel in keeping their confidences were some of the reasons that mothers would not have shared their stories to obtain support from the church and why they eagerly drew on the support offered to them at the CRU.

The views of Cutchin et al's22 on occupational transaction, describes the goal of engagement in occupation as having 'ends in view', constantly changing and adapting. As mothers engaged in the caring role, their acceptance of this role was built upon by positive experiences within the caregiving role. They drew meanings from these experiences, gaining a sense of fulfilment when they were able to care and provide for their children. Mothers reported exciting moments, such as watching the child grow and play, as well as the improvements in the health of the child. Kuo20 states that caregiving situated by habits and context provide a means through which mothers creatively improvise everyday activities to ultimately achieve desirable outcomes. Progress in the child was confirmation of being a good mother. Noting the positive changes happening in the child brought a sense of joy, hope and relief to the mothers who had previously experienced negative situations when the child was severely ill and not able to do anything. The recovery of the seriously ill child brought back a sense of joy to the mothers and assurance that they were doing the right thing. Mothers especially valued positive changes in the 'doing' of the child, for example when child was able to crawl, walk, feed and engage in play. The term 'doing' has gained popularity in the occupational science and occupational therapy profession and Wilcock28 discusses how the concepts of doing, being and becoming are integral to occupational therapy philosophy, process and outcomes. Mothers echoed the same notion as Wilcock20 considering 'doing' as a determinant of health and wellbeing. Mothers valued even the smallest things that the child could do. The experience of watching one's own child exhibit a sense of 'doing' and autonomy generated meaning and fulfilment for the mothers. In some instances, the mother would be happy even if the child exhibited wilful behaviours. 'Doing' meant less dependence on the mother and, as the child was able to engage and participate in more occupations (such as feeding, toileting and play), mothers could be free to engage in other occupations. There is potential for occupational therapists to continue to build on the meaning of the mothers in their caring role by promoting 'doing' in the children with HIV-related NDD.

Implications for practice

The study highlighted the transactional occupation of caring for a child with HIV-related NDD as shaped by both personal and contextual factors. Thus, occupational therapy is encouraged to enlarge its scope of practice from focusing on the child with impairment, to include the mother as the primary caregiver who is engaged in the occupation of caring for the child, in relation to both their context and their own personal attributes. There is a need for assessment procedures and interventions that take cognisance of the interplay of personal factors and context for mother and child. Also, the various ways in which these mothers orchestrate their daily occupations to accommodate the care of their child as well as the value they place on the care of their child, warrants further investigation.

CONCLUSION

The study reveals the transactions that happen between the mother and the context (environment) in which the occupation of caring for a child with NDD takes place. The role of the context - which included culture and spirituality - in shaping the experiences of the mothers, should not be underestimated and it would be unjust to look at the mother as an individual outside her context. The findings of this study have also highlighted the interplay and interdependence between the contextual and the personal factors that shape the experience of the occupation of caring for a child with HIV-related NDD. Thus, the findings of this study should encourage occupational therapists to carefully consider the transactional nature of occupation and how the mothering role positively shapes these mothers' identities, when they design interventions for this population group.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Munambah and Gretschel developed the concept and design of the study. Munambah submitted the proposal draft for ethical approval and conducted the data collection. Munambah and Gretschel conducted the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. Sonday played on oversight role during data collection and analysis. All the authors assisted in revising the manuscript for submission to a journal. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and Munambah was the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

1. Ikiugu M, Pollard N, Cross A, Willer M, Everson J, Stockland J. Meaning making through occupations and occupational roles: a heuristic study of worker-writer histories. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; 75(6): 289-95. https://doi.org/10.4276/0308022l2X13383757345229 [ Links ]

2. Lin F-Y Rong J-R, Lee T-Y Resilience among caregivers of children with chronic conditions: a concept analysis. Journal of Multidisci-plinary Healthcare. 2013; 6: 323. https://dx.doi.org/10.2I47%2FJMDH.S46830 [ Links ]

3. Larson E. Identifying indicators of well-being for caregivers of children with disabilities. Occup Ther Int. 2010; 17(1): 29-39. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.284 [ Links ]

4. Phelan SK, Kinsella EA. Occupation and identity: Perspectives of children with disabilities and their parents. Journal of Occupational Science. 2014; 21(3): 334-56. [ Links ]

5. Bourke-Taylor H, Howie L, Law M. Impact of caring for a school-aged child with a disability: understanding mothers' perspectives. Aust Occup Ther J. 2010; 57(2): 127-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.I440-I630.2009.00817.x [ Links ]

6. Donovan ML, Corcoran MA. Description of dementia caregiver uplifts and implications for occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 2010; 64(4): 590-5. https://doi.org/10.50I4/ajot.2010.09064 [ Links ]

7. Kuo C, Operario D. Health of adults caring for orphaned children in an HIV-endemic community in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011; 23(9): 1128-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.554527 [ Links ]

8. Potterton J, Stewart A, Cooper P, Goldberg L, Gajdosik C, Baillieu N. Neurodevelopmental delay in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus in Soweto, South Africa. Vulnerable children and youth studies. 2009; 4(1): 48-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450120802183728 [ Links ]

9. Hejoaka F Care and secrecy: being a mother of children living with HIV in Burkina Faso. Social science & medicine. 2009; 69(6) :869-76. [ Links ]

10. D'Auria JP Christian BJ, Miles MS. Being there for my baby: Early responses of HIV-infected mothers with an HIV-exposed infant. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2006; 20(I): 11-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.08.008 [ Links ]

11. Van Graan A, Van der Walt E, Watson M. Community-based care of children with HIV in Potchefstroom, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2007; 6(3): 305-13. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085900709490426 [ Links ]

12. Mangezi W, Chibanda D. Mental Health in Zimbabwe: Country Profile. International Psychiatry. 2010; 7(4): 95-96. [ Links ]

13. Kandawasvika GQ, Ogundipe E, Gumbo FZ, Kurewa EN, Mapingure MP Stray-Pedersen B. Neurodevelopmental impairment among infants born to mothers infected with human immunodeficiency virus and uninfected mothers from three peri-urban primary care clinics in Harare, Zimbabwe. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2011; 53(11): 1046-52. https://doi.org/10.IIII/j.l469-8749.2011.04l26.x [ Links ]

14. Lala AF? Kinsella EA. A phenomenological inquiry into the embodied nature of occupation at end of life. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 78(4): 246-54. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2011.78.4.6 [ Links ]

15. Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction: Sage; 2006. [ Links ]

16. Savin-Baden M, Claire H. Major. Qualitative Research The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice London and New York: Routledge; 2013. [ Links ]

17. Lincoln YS. en GUBA, EG, Naturalistic Inquiry, Beverly Hills. CA: Sage; 1985. [ Links ]

18. Creswell JW. Designing and Conducting Mixed-Methods Research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA; 2007. [ Links ]

19. Moustakas C. Phenomenological research methods: Sage; 1994. [ Links ]

20. Kuo A. A transactional view: Occupation as a means to create experiences that matter. Journal of Occupational Science. 2011; 18(2): 131-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.554527 [ Links ]

21. Wilcock AA. An occupational perspective of health: Slack Incorporated; 2006. [ Links ]

22. Cutchin MPAldrich RM, Bailliard AL, Coppola S. Action theories for occupational science: The contributions of Dewey and Bourdieu. Journal of Occupational Science. 2008; 15(3): 157-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/I4427591.2008.9686625 [ Links ]

23. Dickie V Cutchin MP Humphry R. Occupation as transactional experience: A critique of individualism in occupational science. Journal of Occupational Science. 2006; 13(1): 83-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2006.9686573 [ Links ]

24. Townsend E, Stone SD, Angelucci T, Howey M, Johnston D, Lawlor S. Linking occupation and place in community health. Journal of Occupational Science. 2009; 16(1): 50-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/I442759I.2009.9686642 [ Links ]

25. Nota A, Chikwanha TM, January J, Dangarembizi N. Factors contributing to defaulting scheduled therapy sessions by caregivers of children with congenital disabilities. Malawi Med J. 2015; 27(I): 25-8. https://doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v27iL7 [ Links ]

26. Moghimi C. Issues in caregiving: The role of occupational therapy in caregiver training. Topics in geriatric rehabilitation. 2007; 23(3): 269-79. https://doi.org/10.1097/0I.TGR.0000284770.39958.79 [ Links ]

27. Demmer C. Experiences of families caring for an HIV-infected child in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: an exploratory study. AIDS Care. 2011; 23(7): 873-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.542123 [ Links ]

28. Wilcock AA. Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1999; 46(I): I-II. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

N Munambah

Email: nyariemnambah@live.com