Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versión On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versión impresa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.50 no.1 Pretoria abr. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2020/vol50no1a3

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

The use of appreciative inquiry with mental health service consumers -towards responsive occupational therapy programmes

Michelle Elizabeth UysI; Lizahn Gracia CloeteII

IBA Humanities (SU), B OT (SU), M OT (SU) Occupational Therapist, Private Practice, Stellenbosch. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2565-9402

IIMSc (UCT), PhD (UCT) Senior Lecturer, Department of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences, Division Occupational Therapy, Stellenbosch University

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Common ways of planning and evaluating occupational therapy services include the clinical judgement of therapists and cause-effect interpretation of statistics. Patient-informed methods of planning occupational therapy services are yet to be explored within occupational therapy, and more specifically within the provision of in- and out-patient mental health services in South Africa. An Appreciative Inquiry was conducted to explore the views of a group of out-patients on a craft group at a tertiary mental health hospital in the Western Cape, South Africa.

OBJECTIVES: To highlight the use of Appreciative Inquiry to explore the perspectives of out-patient mental health consumers. To identify the enabling elements contained in an Occupational Therapy out-patient craft group.

METHODOLOGY: A social constructivist paradigm framed the research process. The 4-D model of Appreciative Inquiry was used. Six participants selected via purposive sampling were recruited as co-researchers. Five data collection sessions of 90 minutes each were conducted. Inductive analysis was used.

FINDINGS: The research participants come from differing ethnic and social backgrounds which contributed to the richness and transferability of the findings. Participants identified ten elements that enabled them to improve their mental health and enhanced their sense of belonging to the group. These included non-judgement, being able to redo the craft activity at home, no pressure, the stimulating effect of the group, being able to talk to the therapist about anything, feeling like a family, socialising nicely, a calm environment, feeling safe at the group and a quiet environment. It may be unrealistic for an occupational therapist to have the time available to evaluate their clinical services using the Appreciative Inquiry model. However, it may be beneficial for occupational therapists to apply the principles of Appreciative Inquiry in the evaluation of their groups.

CONCLUSION: Appreciative Inquiry is a valuable method for exploring patient views of useful aspects of occupational therapy outpatient art groups.

Key words: Psychiatry, Craft Groups, Outpatients, Appreciative Inquiry

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), mental health is defined as a "state of wellbeing whereby the individual realises their own potential" and can work productively to contribute to society1. Persons who live with mental health conditions may experience challenges in attaining and sustaining their wellbeing. Although collaborating with clients as partners in the recovery process is consistent with the occupational therapy approach of client-centeredness, occupational therapy mental healthcare rehabilitation in some mental healthcare settings in South Africa remains to be delivered within a deficit-based model2. South Africa reformed its healthcare policies in the Western Cape in 2014 when the provincial cabinet endorsed a societal approach to health and wellness through Healthcare 20303. Communication about the appropriateness of services between mental healthcare service users and the healthcare team in service planning may improve service delivery4.

Mental healthcare services in South Africa are provided as part of a comprehensive healthcare provision5. The variation in budget and resource allocation between provinces is based on the size of the catchment areas and population sizes in each province. Within the current healthcare system, mental health services are provided in 3460 out-patient mental health facilities, 80 day-treatment facilities and 41 psychiatric units located in general hospitals6. Comprehensive healthcare provision, which extends into the home and

community environment, should include a focus on facilitating the transition from hospital-based services to out-patient and community-based services7. It is crucial to establish out-patient groups in tertiary hospitals to continue occupational therapy intervention and to reduce readmissions.

Appreciative Inquiry lends itself to involving service users as partners in co-creating ideal conditions8. The delivery of responsive and appropriate occupational therapy programmes requires the input of both the occupational therapy practitioner and the mental healthcare service user. Incorporating the views of mental healthcare service users as co-participants enables critical and honest communication between the occupational therapist as a mental healthcare service provider and other service users9. Eliciting patient perspectives on occupational therapy service provision is a valuable feedback method. Occupational therapists are central service providers for mental healthcare users.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Internationally, the importance of patient-perspectives on mental health care service users is emphasised10. However, conducting participatory action research with mental health service consumers in occupational therapy is not common. An ethnographic study demonstrated the healing value of craft activities in occupational therapy11. Creative activities as a therapy developed in the 1800s to 1900s, concurrent to psychiatry12. The use of craft activities as a therapeutic medium in the mental healthcare team is unique to occupational therapists11.

In 1943, craft activities were incorporated into the occupational therapy trainig curriculum in South Africa and were central in the treatment of mental healthcare service users13. The philosophical underpinning of the occupational therapy profession emphasises the power of activities and occupations for improving quality of life. The use of arts and crafts in assessment and intervention is at the epicenter of in-hospital mental health care treatment.

The philosophical underpinning of the occupational therapy profession emphasises the power of activities and occupations for improving quality of life. In a qualitative descriptive study, Bell et al.14 found that most participants were not able to identify the value and reasoning behind the arts and craft group in therapy. This study therefore used an appreciative inquiry approach to create an equal partnership in the research process, whereby mental health service consumers as co-researchers could share their views on what they would like to achieve from the research process15. Appreciative inquiry creates the opportunity to focus on positive past experiences as a means of problem solving in a group context, while it simultaneously provided the researchers with an effective framework for refining service delivery in a mental health care craft group15.

Appreciative inquiry offers a multitude of benefits when used as a research approach16. Additionally, Appreciative inquiry, if used correctly, can create a platform from which to evaluate practice17. Appreciative inquiry builds on positive, past experiences. This positive focus may allow for an easier transition into the change process that draws on the strengths of service users as partners, in co-creating mental health services that best suit their needs18. Appreciative inquiry concentrates on identifying the specific strengths of a group of people through asking particular, positive questions, to motivate and induce positive action, and ultimately change.

ETHICS

This research study adhered to ethical policies in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Stellenbosch University Ethics Principles. The study received ethics clearance from the Human Research Ethics committee at Stellenbosch University (HREC ethics number U16/02/002). Participants took part voluntarily in the study and gave informed consent. Their identities were kept confidential with pseudonyms.

METHODS

Study Aim

To explore and describe the elements that contribute to a successful occupational therapy out-patient craft group from the patients' perspective, using an Appreciative Inquiry model.

Objectives

✥ To highlight the use of Appreciative Inquiry to explore the perspectives of out-patient mental health consumers.

✥ To identify the enabling elements contained in an Occupational Therapy out-patient craft group.

Research Design

Appreciative Inquiry concentrates on identifying the specific strengths of a group of people through asking particular, positive questions to motivate and induce positive action towards the desired change19. This approach operates within a multi-step framework consisting of four phases, namely Discover, Dream, Design and Destiny. Step 1 is the discovery phase, where the group would identify the processes that work well with the group. Step 2 is the dream phase, where group members envision processes that would work well in the future. Step 3 is the design phase, where processes that work well will be prioritised and planned. Step 4, the destiny phase of the model refers to the implementation of the proposed design20. The application of these steps within the context of this study will be explained under the section on data collection.

Appreciative Inquiry creates the opportunity to focus on positive past experiences as a means of problem solving in a group context. This action research methodology also provided the researchers with a useful framework for refining service delivery in a mental healthcare craft group15. A supportive, trusting study environment was created to enable participant co-researchers to voice their opinions on the successful elements of an out-patient craft group. The participants' anecdotes were used to comment on participant participation in occupational therapy craft groups.

The Researchers

Members of the research team performed different tasks but assumed equal responsibility as co-researchers. The research team consisted of five student researchers, six mental healthcare service users referred to as the mental healthcare service user participant co-researchers (MHCSU) and the occupational therapy practitioner (key informant). The six MHCSU participant co-researchers were selected from a group of out-patient arts and craft group attendees according to the selection criteria as highlighted in the following section. During the introduction session, they received information on the research process and their roles as co-researchers. They also made suggestions for the structure and planning of sessions. Table 1 on page 14 depicts the team members and their roles.

Study population and sampling strategy for mental healthcare service user participant co-researchers

A list of craft group attendees was received from the key informant. Convenience sampling, a non-probabilistic sampling technique was used. All the outpatient craft group members met our inclusion criteria. The occupational therapist who facilitated the out-patient group assisted with selecting participants who met the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

✥ Compliance with prescribed medication and effective communication about their mental health needs.

✥ Ability to travel independently to all data collection sessions.

✥ Older than 18 years of age.

✥ Confirmed chronic mental health condition and registered as an out-patient.

Exclusion criteria

✥ Non-compliance with prescribed medication.

✥ Irregular arts and craft group attendance.

✥ Inability to articulate if they required assistance with certain tasks related to the research process.

Table II on page 14 depicts the biographies of the MHCSU co-researchers.

Study setting

As part of the occupational therapy psychosocial programme available to out-patients of the mental health facility, the out-patient craft group offered a space where discharged patients could engage in socialising with other out-patients while doing crafts. The out-patient craft group took place every fortnight. Participant co-researchers were established out-patient craft group members with one or more mental health diagnoses. The study took place at a tertiary mental health hospital in the Western Cape, South Africa. The participants originated from the surrounding catchment areas, five of the six having previously been admitted to a tertiary hospital.

Data collection

Data collection took place twice a week for two weeks. Each session was one hour (therefore amounting to over five hours) and took place independently of the time required for the craft group. The researchers aimed to conduct the data collection sessions prior to the start of the craft group. A total of four data collection and one-member checking session was conducted. Data collection sessions were conducted in Afrikaans. One researcher acted as the session facilitator during the contact sessions. This ensured consistency in the communication of instructions and explanation of terms where needed. Having a constant facilitator of sessions assisted participant co-researchers to become familiar with the main facilitator and enabled them to express their opinions freely. The occupational therapist as a key informant was also present in all contact sessions, adding to the familiarity of the environment. The main student facilitator attended all five contact sessions while the other four students rotated so that each co-facilitated one data collection session.

These sessions consisted of semi-structured interviews, group discussions and activities used by the student researchers to collect data with the mental healthcare service user participant co-researchers. The activities included the MHCSU participant co-researchers creating a mural in data collection stage four and the arrangement of group elements in data collection stage three and the identification of group elements on a diagram of a scale in stage 2. Open-ended questions were posed to the MHCSU participant co-researchers to encourage storytelling. All sessions were audio recorded. The first four data collection sessions correlated with the 4-D model of Appreciative Inquiry15, namely "discovery", "dream", "design" and "destiny". See Figure 1 on page 15.

Session 1: Discovery

During phase one of the 4-D model of Appreciative Inquiry, the aim was to capture the MHCSU participant co-researchers' collective reasons for attending the occupational therapy craft groups as well as the value of this group. Storytelling facilitated the discovery of a variety of experiences among participant co-researchers. A discussion was held in which the participant co-researchers reflected on how the structure and nature of the current craft group assisted them in meeting personal and group outcomes.

Session 2: Dreaming

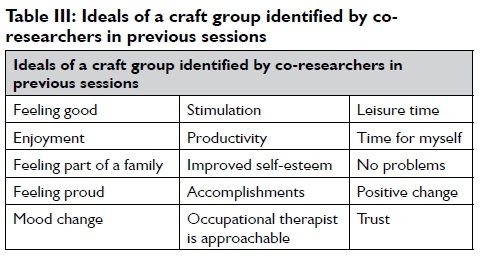

In session 2, the craft MHSCU group envisioned the processes within the group that would work well in the future. See Table III below. Based on co-researchers opinions on the value of the out-patient craft group, an exploration was conducted regarding the features of an ideal out-patient craft group that could aid in enabling participation in patient-identified experiences. This stage created an opportunity to identify gaps in the existing group with storytelling. A discussion was held in which the MHSCSU participant co-researchers reflected on how the structure and nature of the current craft group assisted them to meet personal and group outcomes.

Session 3: Design

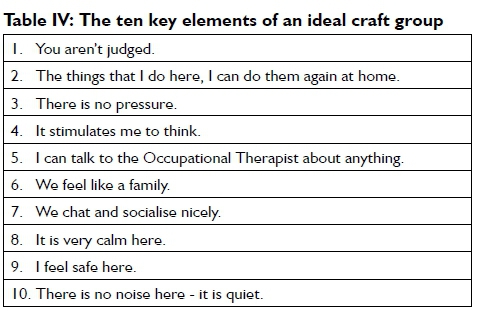

In session 3, the processes that worked well were prioritised. During the analysis of data from sessions 1 and 2, the student researchers identified the main group elements by selecting descriptions that were repeated in the data. These group elements were then arranged in order of importance by the MHCSU co-researchers. See Table IV (in the next column). These co-researchers were invited to make suggestions for the structure and nature of the ideal out-patient occupational therapy craft group that would facilitate meeting patient identified outcomes.

Session 4: Destiny

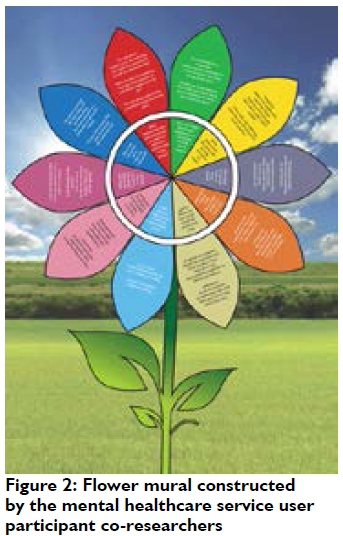

In session 4, the MHSCU co-researchers identified the strategies that would facilitate the maintenance of existing best practice. The group members were given pieces of colour paper to write their responses to questions down. Using the coloured pieces of paper on which the MHSCU co-researchers answered the questions posed, a flower was constructed. A corresponding question represented each petal of the flower. See Figure 2 (above) and Table VII (page 18). At the end of session four, all researchers discussed the progress made in the research process and reflected on the previous contact sessions. Table VII provides the content of the flower mural produced by the mental healthcare service user participant co-researchers.

Data analysis

Weft Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) is a tool used for processing qualitative textual data such as the conversations held between researchers and participants within this study. Raw data were transcribed and, where required, translated from Afrikaans into English before using Weft QDA for analysis. Each transcript was analysed before the following session by the student researchers. An inductive data analysis produced recurrent features such as patterns and themes. Each theme consisted of clusters of coded information known as nodes. After three rounds of data analysis, nodes were clustered into 12 subcategories. The fourth and last round of data reduction generated four themes.

Trustworthiness and Rigor

Credibility was ensured by prolonged engagement and ensuring that the researchers were immersed in the research environment. Member checking was completed after all data was collected to ensure the accurate interpretation of the findings. During this session, the participant MHCSU co-researchers were invited to confirm the analysed themes21 and offer additions/corrections where needed. Member checking was used to verify that the client-participants could recognise their own words in the analysis and were able to verify our interpretations and conclusions. Transcription of raw data, translation of transcribed data, and three rounds of analysis and corroboration of coded themes ensured the dependability of the research process. Since data were collected in Afrikaans, the quotes that were included in the findings were translated into English for reporting purposes. Back translation into Afrikaans ensured the credibility of translation. Throughout data analysis, the researchers worked under the guidance of an expert in qualitative research, who did not form part of the research team. There were five student researchers and six co-researchers, which ensured the triangulation of the research. During research meetings, peer debriefing contributed to the rigour of the findings. An audit trail was kept by recording meetings with the research supervisor and the careful documentation of plans throughout the research process.

FINDINGS

Two main themes emerged, namely feeling accepted and that of individual improvement. Table V below summarises the themes and subcategories.

The theme of feeling accepted comprised of three main categories (Table V on this page). I feel relaxed when attending the craft group pertains to the peaceful atmosphere created by the elements present in the group. Feelings of safety within the craft group were brought about by the trust and understanding evident amongst members within the setting. Lastly, the craft group provided the group members with a sense of belonging associated with that of a family.

The theme relating to individual improvement is comprised of three categories (Table V). In the category about positive thinking, the members described feelings of pride after attending the group and a more positive emotional state. The group was also said to assist the members in clearing their minds and this time was referred to as "me time". Finally, a category of transference emerged due to members repeating the crafts outside of the group due to increased motivation.

Feeling Accepted

Contributing to the feeling of not being pressurised is that there was always sufficient time to complete the activity and an absence of competition between group members. The group members feeling comfortable with one another as they view the group as a family, facilitated this. Family qualities depicted within the group are that of understanding and being able to speak openly with one another, made possible by the absence of judgement and the overall feeling of acceptance within the group.

Quotes from the semi-structured interviews reflected the support that participant co-researchers experienced a trusting and understanding relationship with other group members:

Tayla: Yes, we all went through the same process, each one was different; this one is divorced, this one has lost a child and so uh, that type of stuff it is. However, in the end, we understand each person, and each person went through a heart sore process, so we understand one another well.

Danny: [We] can help to encourage each other; I think that it is just us that can help each other because we understand each other better than the others do.

Alex: Sometimes I came here and felt that I wanted to collapse into the earth and then someone would just give me a hug, and that hug for me meant so much that I could carry on and made me feel courageous again, full of life and excited about life. So we are all here for each other.

Tayla: I feel [like] a person, we speak our hearts out here with each other, hey?

Participant co-researchers experienced the group to be calm, relaxing and a safe place where they felt unconditional acceptance:

Joe: There is no judgement here.

Danny: And it is so nice, it [the quiet environment] feels like it gives your mind a chance to rest. Because there is a busyness in my head and when you come here, a calmness comes over you.

Alex: I was always negative and it [craft group] feels like a family where in the beginning I felt um, that I did not want to be here, I was afraid. Will they [other group members] accept me? Will they push me out? And they accepted me and it is like a family for me now.

Sue: I reckon it is also the space where we can also talk about what our issues are at the time.

Tayla: Um, like I can now relate [to] her, she has the autistic children and I have a cerebrally disabled child, so uh, she is going to understand more or less, how I feel about my child. What my child does. What I have to live with because it is not his fault that he is like that, see? Like uh, she will understand me.

Sue: We are family you know uh, orientated and we are like a family.

The participant co-researchers felt that the group influenced them positively:

Tayla: I started to think positively.

Joe: Yes, you feel much better, more positive. It is very positive, it is very nice.

Five out of six participant co-researchers confirmed that they felt accepted and safe when they come to the craft group. The craft group members serve as a family away from home.

I Have Improved

It was indicated that determination was learned through participation in the craft activities, resulting in the group members being able to complete their crafts; something they were previously unable to achieve. The craft group members repeating these crafts at home with family and friends, an act, which aided in the formation of bonds and provided a sense of personal accomplishment, identified this progress. These crafts are displayed or given as gifts, resulting in improved self-confidence and self-esteem.

Tayla: I have learned here, to finish one thing at a time.

Sue: So now with doing craft things, I'm must actually start to think of starting to do that [drawing] again. But to get the motivation to do it and get - going through all the drawing that I used to do.

Participant co-researchers were invited to make suggestions regarding the structure and nature of the ideal out-patient occupational therapy craft group that would facilitate meeting consumer identified outcomes. The list that was generated is depicted in Table VI below.

Alex's comment demonstrated the craft group as a means for getting better and transferring learned skills to the home environment. She was the only participant co-researcher who reflected on how she repeats the craft activities at home as a leisure time pursuit, or with family members, thereby aiding in the formation of bonds with people outside of the craft group:

Alex: That what I do here I am going to do again at home.

Alex: If my brother's daughter, grandchildren come, grandchildren then they always ask me what I made then I show them, then I say to them I must show them how to make it [the craft] then I teach them again how to make it.

Furthermore, 10 key elements were identified to contribute to the feelings of acceptance and progress experienced by the members, namely, no-judgement, being able to redo the craft activity at home, no pressure, the stimulating effect of the group, being able to talk to the therapist about anything, feeling like a family, socialising nicely, a calm environment, feeling safe at the group and a quiet environment.

Action plans were created to identify what an outpatient craft group occupational therapist could do to maximise the success of the group. The MHCSU Mental healthcare service user participant co-researchers suggested that a flower mural should be created as a means to identify the factors that will ensure a successful craft group. The student researchers formulated the questions based on the findings from the previous sessions which were verified by the mental healthcare service user participant co-researchers. Table VII (page 18) displays the findings from the flower mural.

DISCUSSION

The discussion outlines the value of using an appreciative inquiry method with participant co-researchers, who were also out-patient mental healthcare service users. Participatory methods are useful for appraising occupational therapy out-patient services in mental healthcare facilities.

Involving consumers in the planning and evaluation of occupational therapy services

Appreciative Inquiry allows us to build on aspects, which occur naturally within the experience of co-researchers and enabled further understanding into the value of occupational therapy out-patient groups from the patient's perspective. The use of the Appreciative Inquiry model shifted power relations existent in the clinical setting, in which a transactional relationship exists between the practitioner and the client, to a research process, which created an environment in which participant co-researchers, could express a sense of belonging and empowerment, feeling safe and accepted by others. Participant co-researchers could identify the positive features of the craft group, such as how attending the craft group helped them to improve their mood and ability to organise their lives.

Appreciative Inquiry as an appraisal tool

Service users' input into existing programmes could increase the participation of mental healthcare service users in their recovery9. Within the study, the use of Appreciative Inquiry enabled participant co-researchers to make suggestions regarding how service could be improved, created opportunity to appraise the structure, function and process of the existing craft group, and identify how they could contribute to the success of the group. Participant co-researchers expressed feelings of belonging, and an ability to thrive in an atmosphere of the arts and craft group where they trust fellow group members and feel accepted by the group. Appreciative Inquiry provided the researchers with an opportunity to uncover the enabling elements of the arts and craft group, which subsequently allowed for suggestions for improving the craft group even further.

Transferring skills learned in the craft group

The strength of Appreciative Inquiry as a method for facilitating 'possibility thinking' enabled participant co-researchers to create a vision for the ideal out-patient craft group. Maintaining mental health and preventing relapse with out-patient craft groups could, therefore, enrich rehabilitation service models of mental healthcare provision at primary levels of care. Participation in out-patient arts and craft groups inspired participant co-researchers to take their crafts and their skills home, achieving the goal of mental health rehabilitation in occupational therapy to re-integrate mental healthcare service users successfully into their home and community environment. Involving mental healthcare service users by facilitating their provision of feedback on how best occupational therapy out-patient services facilitate mental wellbeing contributes to designing responsive, patient-informed occupational therapy services.

LIMITATIONS

Due to the limited number of participant co-researchers the findings of this study cannot be generalised. However, efforts were made by the researchers to ensure the transferability of the findings. The research participants come from differing ethnic and social backgrounds which contributed to the richness and transferability of the findings. The authors aimed to limit biases by ensuring that they used the co-researchers' words and ideas are presented as accurately as possible. It is unrealistic that an occupational therapist facilitating out-patient craft groups will have this amount of time available to evaluate their clinical services using the Appreciative Inquiry model. However, it may be beneficial for occupational therapists to do shorter sessions and facilitate a more structured discussion. One of the limitations of using the Appreciative Inquiry model with chronic mental healthcare users was the fact that participant co-researchers only reported on success factors. Appreciative Inquiry has a positive focus. However, it can elicit discussions on negative barriers, something that did not take place in this study.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The use of appreciative inquiry as an appraisal tool may facilitate the identification of elements that enable the rehabilitation and recovery of mental health care service users. Participatory research approaches may also enable psychiatric facilities to identify enabling and hindering factors to their recovery in the ward. Occupational therapists facilitating craft groups can monitor and review outpatient and inpatient arts and craft group activities through implementation of the action plans developed by the mental healthcare service users themselves. The continuous implementation of Appreciative Inquiry will ensure that the craft group remains the best version that it can be and that the group members can be involved in the "brainstorming" and "implementation" of their treatment. It is recommended that occupational therapists use the Appreciative Inquiry model as part of their strategic planning process to plan appropriate, responsive out-patient interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of crafts in out-patient mental health service occupational therapy groups is poorly investigated. Despite the evidence that arts and craft groups are valuable in the rehabilitation of mental health care users, little is known about the elements that support recovery and transference of life skills into real-life situations. It has been highlighted that the use of Appreciative Inquiry can be used as an approach to eliciting responses from mental healthcare service users which could assist occupational therapy practitioners in identifying, maintaining and improving out-patient mental health services in South Africa. Appreciative inquiry as an action research method, was able to successfully identify the elements contained in an occupational therapy out-patient craft group for the service users' perspective, which can be used as a baseline for occupational therapists running groups for mental healthcare service consumers across South Africa.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Both authors conceptualised, drafted, developed and edited the manuscript.

ME Uys was the main facilitator and therefore present at all data collection sessions and was involved with the transcription, translation and analysis of the data.

LG Cloete provided mentorship, conceptual and editing contributions throughout the research and manuscript writing process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to acknowledge Kirsty Eckersley, Tenille Brewer, Dominique Roberts and Tracey-Lee Sam for their contribution as student co-researchers during the phases of data collection, data transcription, data translation and data analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We declare that there are no competing interests.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Promoting mental health: Summary report - A report of the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and The University of Melbourne, 2004. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/promoting_mhh.pdf [ Links ]

2. Clossey L, Mehnert K, & Silva S. Using Appreciative Inquiry to facilitate the implementation of the recovery model in mental health agencies. Health and Social Work. 2011; 36(4): 259-266. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/36.4.259 [ Links ]

3. Western Cape Government (Department of Health). Healthcare 2030. The Road to Wellness, 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/departments/health/health-care2030.pdf. [ Links ]

4. Newman D, O'Reilly P Lee S, Kennedy C. Mental health service users' experiences of mental health care: an integrative literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2015; (22): 171 - 182. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ez.sun.ac.za/doi/epdf/10.1111/jpm.12202 [ Links ]

5. Department of Health (Republic of South Africa). National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan (2013-2020); 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.health-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/National-Mental-Health-Policy-Framework-and-Strategic-Plan-2013-2020.pdf [ Links ]

6. World Health Organization. WHO-AIMS Report on mental health system in South Africa: A report of the assessment of the mental health system in South Africa using the World Health Organization - Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS). Cape Town; South Africa: WHO and Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of Cape Town, 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/south_africa_who_aims_report.pdf [ Links ]

7. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M & Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequality, and inefficiency. The Lancet. 2007; 370(9590): 878-889. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2 [ Links ]

8. Gallagher R A, Heyne M E. Appreciative Inquiry: The pluses and the minuses. Draft Document; 2011. Retrieved from: http://staticI.I.sqspcdn.com/static/f/630204/16788918/1330119981937/Appreciative+inquiry-+The+pluses+and+the + minuses-as+of+2-24-12.pdf?token=txIuqfjMr0qjWWRtCa7UGq5uqqA%3D [ Links ]

9. Meagher A M, Fowke T. National Consumer and Carer Forum of Australia: A framework for the mental health sector. National Consumer and Carer Forum of Australia; 2005. Retrieved From: https://nmhccf.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/nmhccf_-_evalua-tion_-_nmhccf_key_facts_and_observations_-_june_20I7_0.pdf [ Links ]

10. Grim K, Rosenberg D, Svedberg P Schön U-K. Shared decisionmaking in mental health care-A user perspective on decisional needs in community-based services. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Health and Well-being. 2016; 11. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4862955/ [ Links ]

11. Horghagen S, Fostvedt B, Alsaker S. Craft activities in groups at meeting places: Supporting mental health users' everyday occupations. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014; 21: 145-152. http://doi.org/10.3109/I1038128.2013.866691 [ Links ]

12. Malchiodi C. Expressive therapies: History, theory and practice. Gilford Publications; 2005. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/files/attachments/231/mal-chiodi3.pdf [ Links ]

13. Hutcheson C, Ferguson H, Nish G, Gill L. Promoting mental well-being through activity in a mental health hospital. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010; 73(3): http://doi.org/12110.4276/030802210X12682330090497 [ Links ]

14. Bell T, Wegner L, Blake L, Jupp J, Nyabenda F. Clients' perception of an Occupational Therapy intervention at a substance use rehabilitation centre in the Western Cape. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 45(2): 10-I4. [ Links ]

15. Bathje M Art in occupational therapy: An introduction to occupation and the artist. Open Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012; I. https://doi.org/10.15453/2I68-6408.1034 [ Links ]

16. Rubin R, Kerrell R, Roberts G. Appreciative Inquiry in occupational therapy education. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 75(5): 233-240. https://dx.doi.org/10.4276/0308022IIX13046730II6533 [ Links ]

17. Hennessy J L, Hughes F. Appreciative inquiry: A research tool for mentalhealth services. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Support Workers. 2014; 52(6): 34-40. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20140127-02 [ Links ]

18. Rogers P J, Fraser D. Appreciating Appreciative Inquiry. New Directions for Evaluation. 2003; 100: 75-83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.101 [ Links ]

19. Gallagher R A, Heyne M E. Appreciative Inquiry: The pluses and the minuses. Draft Document. 2012. Retrieved from: http://staticI.I.sqspcdn.com/staticf/630204/I6788918/1330I19981937/Appreciative + inquiry-+ The+pluses+and+the+minuses-as+of+2-24-12.pdf?token=txIuqfjMr0qjWWRtCa7UGq5uqqA%3D [ Links ]

20. Cooperrider D L. Appreciative Inquiry: Toward a methodology for understanding and enhancing organisational innovation. Department of Organizational Behaviour, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio;1986. [ Links ]

21. Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qualitative Health Research. c; 26(13): 1802-1811 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Michelle Uys

Email: michelleelizabethuys@gmail.com