Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

On-line version ISSN 2310-3833

Print version ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.50 n.1 Pretoria Apr. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2020/vol50n1a2

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Patient characteristics, therapy service delivery and patient outcomes following pyrocarbon proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty

Nureesah HendricksI; Thayananthee NadasanII; Oladapo Michael OlagbegiIII; Nomzamo ChemaneIV

IBSc Physio (UWC), M Hand Rehab (UKZN). Lead Physiotherapist, Cape Hand and Upper Limb Unit, Life Orthopaedic Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5820-5717

IIB Physio (UDW), M Physio (UDW), PhD (UKZN). Senior Lecturer, Discipline of Physiotherapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

IIIBMR Physio (Ife), MSc Physio (Ibadan), PhD (Ibadan) Postdoctoral Fellow, Discipline of Physiotherapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1320-7567 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2023-0324

IVB Physio (UDW), M Hand Rehab (UKZN). Lecturer, Discipline of Physiotherapy, School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6877-2339

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND/AIM: Studies on likely sociodemographic and pre-surgical determinants of hand function and satisfaction following pyrocarbon proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty (PPIJA) are scarce. The primary aim of this study was to explore the association between pre-surgical sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and post-surgical hand function and satisfaction of patients who underwent PPIJA. A secondary aim was to evaluate the effects of the procedure on pain and active range of movement (AROM) using retrospective data and on-site follow-up assessment.

METHODS: A panel survey of 48 patients (male = 13; female = 35) with median age of 64 years, who had PPIJA between 2001 and 2012, with a total of6l arthroplasties, was conducted. During follow-up, participants' pain and satisfaction, AROM, and hand disability were assessed using the Pain and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ), goniometer, and the Disability of the Shoulder, Hand and Elbow (DASH) Questionnaire respectively.

RESULTS: The main reason for surgery amongst participants was joint stiffness (68%) while 33.3% of the participants had a repeat surgery. Participants' median satisfaction and DASH scores at final assessment were 3 and 22.55 respectively. Patients who underwent arthroplasty once had significantly higher median PSQ scores (p = 0.011) than those who had their surgery repeated. Pain significantly reduced (p < 0.001) while AROM significantly increased (p = 0.001) from pre-operative assessment to final follow-up assessment

CONCLUSIONS: Pyrocarbon arthroplasty improved treatment outcomes regarding pain and joint motion; post-operative satisfaction may be associated with patients having a repeat surgery.

Keywords: Pyrolytic carbon, proximal interphalangeal joint replacement, arthritis, treatment outcome

INTRODUCTION

The hand is comprised of structures and joints that require optimum alignment and control for normal hand function to occur. Hand function relies on anatomic integrity, mobility, muscle strength, sensation and coordination1. Muscle activity is a major determinant of forces acting on the finger joints, with hand grip being a common task, and during which increased muscle forces are sustained at the interphalangeal joints of the fingers2. The proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint is central to hand function3, however the joint has been reported as the third most commonly affected by the presence of osteoarthritis in the hand4. Rheumatoid arthritis and primary or post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the hand are also linked to contractures and pain which account for reduced occupational performance5. Pinch and grip strength in the hand may be substantially reduced as a direct consequence of pain or decreased mobility in the PIP joint4 which can negatively impact on the individual's quality of life6.

Arthritis of the PIP joint is a debilitating condition which can be treated surgically with either joint arthroplasty or arthrodesis.

Arthroplasty involves the excision and replacement of damaged arthritic joint surfaces with a prosthetic joint or an artificial implant while arthrodesis is the surgical fixation of an arthritic joint to promote bone fusion and immobilisation7. However, arthroplasty is a more common form of treatment and a favourable alternative to arthrodesis because arthroplasty offers the advantage of joint mobility8.

Pyrocarbon semi-constrained implants have been in use in Europe and in the United States since 2000 and 2002 respectively9. Pyrocarbon is popular for its durability, strength, resistance to wear and having an elastic modulus similar to cortical bone10. The implant is also beneficial in terms of low rates of periprosthetic fracture, low inflammatory reactions and good opacity for X-ray viewing9. Pyrocarbon as a surgical option of salvaging a degenerated PIP joint5 and the approach is gaining favour due to reported outcomes which included excellent pain relief and implant survival10. Pyrocarbon arthroplasty of the PIP joint is commonly indicated for patients with symptomatic arthritis who have intact collateral ligaments, adequate bony stock and intact extensor tendons or extensor tendons that can be reconstructed11. The presence of arthritic pain remains a major indication for almost every proximal interphalangeal joint procedure12.

Review of studies9,11,13-15 investigating the outcomes following pyrocarbon PIP joint arthroplasty has shown conflicting findings regarding treatment outcomes. Although pain relief seems common to all aforementioned studies, there seems no consensus regarding results on range of motion (ROM). While authors like Meier et al11, McGuire et al16 and Jordaan et al17 reported a significant increase in PIP joint ROM following pyrocarbon arthroplasty, researchers like Bravo et a19, Wijk et al5 and Watts et al18 did not observe appreciable improvement in the outcome. Surgeons are reportedly opting to discontinue using pyrocarbon arthroplasty due to the issue of post-operative complications such as subsidence17,19. Subsidence refers to any change in position of the implant in relation to the bone when comparing the first postoperative radiograph to the radiograph at final follow-up17.

To date, two studies16,17 have been published on PIP joint arthroplasty in South Africa. In 2012, McGuire et al16 reported on a series of 57 uncemented pyrocarbon PIP joints and noted subsidence in 40% of the joints. Recently, Jordaan et al17 examined whether changing to a cemented implant would improve subsidence rates. They observed 26% subsidence with significant improvement in terms of ROM and patient satisfaction. We viewed patient satisfaction and perception of disability as subjective outcomes that may be influenced by other factors besides the success or failure of surgical procedure. At the time of this study, socio-demographic, therapeutic and clinical characteristics that are likely to determine a patient's level of hand function and disability post-operatively, had not been reported. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to investigate the association between pre-surgical sociodemo-graphic and clinical characteristics and post-surgical hand function and satisfaction of patients who underwent PIP joint arthroplasty. A secondary aim was to evaluate the effects of the procedure on pain and active range of movement (AROM) using retrospective data and on-site follow-up assessment.

METHODOLOGY

The study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (HHS/I476/2010M) of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, the permission of management of the specialist clinic involved was also obtained.

Study Population and Sample

The participants were 48 individuals who had pyrocarbon Proximal Interphalangeal (PIP) joint arthroplasty at a specialist clinic in Cape Town, South Africa, from 2002 -2012. A convenience sampling frame was used to recruit available and consenting patients who had undergone pyrocarbon arthroplasty of the PIP joint for the study. All participants were literate in English, as the language is predominant in the Southern suburbs of Cape Town. All particpants gave their signed informed consent prior to their participation in the study once the purpose and procedures of the study were explained to them.

Inclusion criteria were male and female patients aged 40 to 75 years; osteoarthritis and post-traumatic arthritis as an indication for surgery; pyrocarbon arthroplasty for PIP joints of index, middle, ring and little fingers; those with right and left dominant hands; and minimum of six months post-surgery in view of tissue healing time frames.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis as an indication for surgery and those with a previous history of complex regional pain syndrome (as this affects the course, frequency and duration of post-operative rehabilitation and post-operative outcomes) were excluded from the study.

Study Design

This study is a panel survey with both a retrospective component and a post-operative on-site assessment at the clinic.

Procedure

Data collection was carried out in 3 phases: a retrospective review of patients' clinical notes, physical examination of the PIP joint and patient satisfaction.

Retrospective patient chart review

Prospective participants attending rehabilitation sessions at the clinic were informed of the planned study and gave their signed informed consent to allow researchers access to their medical records and contact details prior to the commencement of the research. So-ciodemographic, clinical and treatment-related information such as age, gender, race, educational level, occupation and hobbies, hand dominance, digit affected, details of surgery: stage of joint degeneration and surgical approach used, reason for arthroplasty, frequency of treatments, splinting choices; compliance with treatment schedule, and complications was extracted from patient's files and clinic cards and recorded on a data recording sheet. Baseline pain intensity and ROM (before surgery and at 6th month follow-up) of the PIP joint were also sourced and recorded from participants' medical records.

Physical observation and examination of the PIP joint

Physical examination of the PIP joint was carried out and incidences of deformities such as: Swan neck deformity; Boutonniere deformity; Hyperextension, and scarring were recorded

Outcome measures Pain and Satisfaction

Pain intensity and participants' level of satisfaction with the status of their finger were assessed using the Pain and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ). A pre-coded pain and satisfaction questionnaire that incorporated all relevant aspects of hand surgery reviewed in the literature was constructed. The following response categories (specific to arthroplasty) were identified: pain using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)20; joint appearance and squeaking; participants' satisfaction and willingness to have the same surgery again.

The same principle as the VAS for pain was applied for the evaluation of a satisfaction score. The only difference is in the descriptors found at either end of the scale. For pain assessment, scores of 0 and 10 represent no pain and severe/excruciating pain respectively, in the case of level of satisfaction, 0 and 10 denote very dissatisfied and extremely satisfied respectively.

The VAS is highly reliable with Pearson correlations in the range of 0.40 - 0.80 and the intra-class coefficient of 0.020.

Range of movement of PIP joint

A Sammons Preston Goniometer was used to measure the AROM at participants' replaced PIP joint. Dorsal method of goniometric placement was used as the method has been shown to have a higher inter-rater reliability2I. The participant was requested to position the upper limb on the table with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees and the wrist in neutral position. Using the dorsal aspect of the PIP joint as the axis, the stationary arm of the goniometer was placed along the dorsal midline of the proximal phalanx while the movable arm was placed along the dorsal midline of the middle phalanx. Participants were requested to actively flex the replaced PIP joint. Records showed that this same approach was used by previous assessors to measure AROM.

Level of hand disability

The Disability of the Shoulder, Hand and Elbow (DASH) Questionnaire was used to assess participants' perception of their level of disability22. It is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 30 questions that explore symptom severity, physical activity and the effect of surgery on daily, social and work activity. At least 27 of the 30 items must be completed for a score to be calculated: DASH disability/ Symptom score = [(sum of n responses)-!] x 25n. Where n is equal to the number of responses. The score ranges from 0 (no disability) to 100 (severe disability)22.

The DASH questionnaire is a valid measure of health status in patients with upper extremity complaints; its Pearson correlation coeffecients to the SF-36 subscales ranged from -0.36 to -0.62. Further, the questionnaire had fewer ceiling and floor scores than most of the SF-36 subscales23.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS 25.0 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Shapiro Wilk test24 for normality performed on age, AROM, satisfaction, DASH, and VAS scores data indicated that the data were not normally distributed. Categorical variables were summarised using frequency tables and percentages while continuous variables such as age, satisfaction and DASH scores were summarised using median, mean, range and interquartile ranges.

The Mann Whitney U test (for two independent variables) and Kruskal Wallis test (for three or more independent variables) were used respectively to compare satisfaction and DASH scores across participants' socio-demographics, clinical profile and therapeutic history.

To examine the effects of athroplasty on pain and AROM, VAS pre-operative and final scores were compared using Wilcoxon Signed Ranked test while AROM pre-operative, 6 month and final were compared using Friedman ANOVA. Multiple pairwise post-hoc analysis (for Friedman ANOVA) was computed to identify time points that significantly differ. Level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Participants' demographic characteristics/clinical profile

Data regarding 48 participants, with a total of 61 PIPJ arthroplas-ties, were reviewed and analysed. For the purpose of this study, the most symptomatic joint (i.e. the joint with higher/highest VAS scores) was chosen for patients with multi-digit arthroplasty.

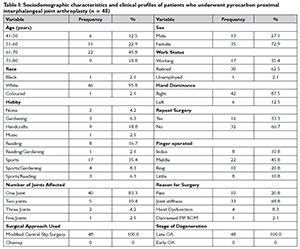

The median age of the participants at final follow-up assessment was 64 years. The summary of participants' sociodemographic characteristics and clinical profile is presented in Table I below. It was observed that 35 of the participants (73%) were female while 30 (62.5%) of the participants were retired. All participants (100%) presented with late OA as the stage of degeneration. The digit most operated on was the middle finger with 22 arthroplasties. Participants' main reason for surgery was joint stiffness (68.8%). All participants (100%) had the modified central slip surgical approach. Of the 48 patients who had surgery, 40 (83.6%) only had one joint operated on while the remaining 8 had surgery for more than one joint. Sixteen patients (33%) however, required repeat surgery.

Participants' therapeutic history

Table II (page 6) shows the therapeutic history of the participants. The average total follow-up time was 18.4 months (range, 2 - 70 months) with most participants (41.7%) having been followed up between 11-20 months.

Post-operatively, all participants (100%) had been fitted with a dorsal blocking splint combined with the modified early active protocol. Twenty-one participants (43.8%) and 28 (58.3%) attended a total of 5-10 sessions of physiotherapy and occupational therapy respectively. Only 25 participants (52.1%) were consistent in attending therapy sessions, while the remaining 23 participants (48%) missed or cancelled between 1 and 4 sessions each.

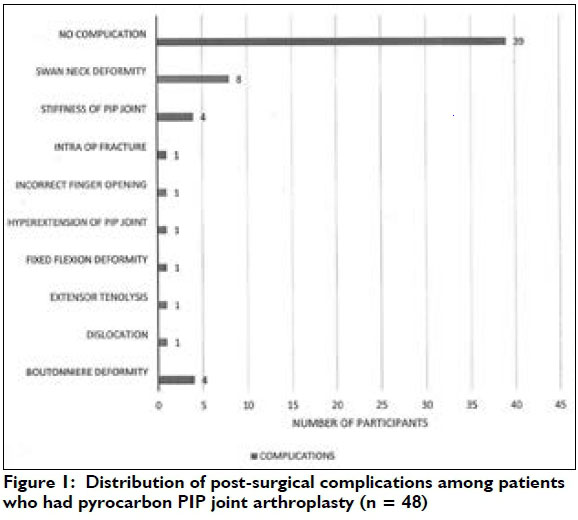

Twenty-two (36.1%) of the 61 fingers operated presented with post-surgical complications. Swan neck deformity was the most prevalent (13.1%) complication observed.

The distribution of post-surgical complications observed among the participants is presented in Figure I opposite. Swan neck deformity occurred in 8 joints (13.1%) this was followed by boutonniere deformity and stiffness of PIP joint which each affected 4 joints.

Treatment outcomes

The median satisfaction and DASH scores were 3 (Interquartile Range (IQR): 2.00, 5.00) and 22.55 (IQR: 12.42, 32.12) respectively. Participants' satisfaction and DASH scores are compared across socio-demographic characteristics and clinical profiles categories in Table III (page 7) and across therapeutic history categories in Table IV (page 8). Patients who underwent arthroplasty once [median: 4.00 (IQR: 2.00, 5.75)] had significantly higher (p = 0.011) satisfaction scores than those who had their surgery repeated [median: 2.50 (IQR: 2.00, 3.00)]. Median satisfaction and DASH scores were not significantly different (p > 0.05) across the categories of other sociodemographic characteristics, clinical profiles and therapeutic history.

Participants' pre-operative (baseline) VAS and final VAS scores, as well as AROM at the three-time points of pre-operative, 6 month and final assessment, are compared in Table V (on this page). VAS scores significantly reduced (p < 0.001) from baseline assessment [median: 7.50 (IQR: 6.25, 8.00)] to postoperative final assessment [median: 2.00 (iQR: 1.00, 3.00)]. Results also showed that AROM significantly increased (p = 0.001) from baseline assessment [median: 37.50 (IQR: 26.25, 60.00) degrees] to postoperative final assessment [median 60.00 (IQR: 40.00, 70.00) degrees]. Post-hoc analysis showed that AROM at 6-month follow-up and the final assessment was significantly higher than the value obtained at baseline but values obtained at 6-month follow-up was not significantly different from those obtained during the final assessment.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the study was to explore the association between pre-surgical socio-demographic and clinical characteristics and post-surgical hand function and satisfaction of patients who had pyrocarbon PIPJ arthroplasty and to evaluate the effects of the procedure on pain and AROM. A large proportion of the patients were very dissatisfied with the post-operative status of their hand while about half of them reported mild disability. The participants, however, had significantly less pain and improved AROM of the PIP joint.

In view of the nature and distribution of osteoarthritis in the hand, multi-digit surgery in an individual patient is common10,18. Participants' median age of 64 years at the time of surgery is consistent with the literature15,18,25,26, as PIPJ osteoarthritis predominantly affects the ageing population. There was a higher proportion of females in the study sample which highlights the higher incidence of PIPJ osteoarthritis in females as it appears to be a common trend in the literature27. The average total follow-up of 18 months observed in the study appears a relatively short follow-up compared to a minimum 7 year follow-up review reported by Storey et a128.

The main indication for surgery was joint stiffness followed by pain and decreased hand function. The literature supports pyrocar-bon PIPJ arthroplasty as the primary surgical indication to address PIPJ osteoarthritis as it provides pain relief and improvement of functional ROM9,16,18,25,26,28,29. The digit most involved was the middle finger which was operated on followed by the ring finger. There is minimal evidence in the literature regarding whether a specific isolated digit shows better or improved treatment outcomes.

The modified central slip splitting surgical approach was used for all 48 patients in this study. This approach involves making a dorsal curvy linear skin incision and performing a midline split of the central slip; the central slip is split and sharply dissected off the middle phalanx while the collateral ligaments are preserved16,17. The rehabilitation technique adopted at this study venue could be described as an early active protocol in view of the fact that it is slightly accelerated in comparison to the standard pyrocarbon arthroplasty protocol16. An early active mobilisation protocol has been associated with minimal complications with postoperative stiffness5,16,26. All participants followed the modified early active protocol with a dorsal blocking splint for protection. Only 6 (12.5%) patients required a dynamic extension splint to address or prevent extensor tendon deficit (extensor lag). The choice of splinting following arthroplasty may affect patient compliance with rehabilitation and exercise protocols30. This study found that only 25 participants (52.1%) were compliant with rehabilitation sessions.

A low average satisfaction score of 3 suggests that a larger proportion of the participants were not happy with the postoperative status of their operated finger. Patients' expectations of surgical outcomes appeared not fully met. This finding further implies that the level of satisfaction might be due to other factors besides pain and reduced ROM, such as the aesthetic appearance of the joint, audible 'squeaking' on active movement and stiffness. A total of 9 participants presented with at least one complication and swan neck deformities was observed in 8 joints. This could have also contributed to the perception of low satisfaction among the participants. Bone quality is another issue with the use of pyrocarbon arthroplasty for post-traumatic PIP joint which could affect outcome of satisfaction, because sclerotic bone may affect component fixation14. Unfortunately, record of bone quality was not available for review in the present study.

The significant improvement observed in terms of pain and AROM outcomes appears not to align with the level of satisfaction reported by the majority of the participants. There is evidence that pain relief and patient satisfaction are generally good after pyrocarbon PIPJ arthroplasty as a large percentage (71-84%) of participants have been reported to be very satisfied9'16,18,26. The works of Bravo et a19, McGuire et al16 and Watts et al18 were retrospective studies with average follow-up of 24, 27 and 60 months respectively. On the other hand, the present study comprised both retrospective and onsite one-time assessment with median follow-up of 12 months. Furthermore, there exists differences in outcome measures used for assessment of patient satisfaction; in the present study, patient satisfaction was assessed using PSQ while Bravo et a19, McGuire et al16 and Watts et al18 used verbal rating (yes or no), likert scale (1-5) and Patient Evaluation Measure respectively for evaluation of patient satisfaction outcome. Nunley et al14 in a prospective cohort of an average follow-up of 17 months, had only 1 (20%) out of 5 patients reported being satisfied. They attributed poor treatment outcomes and high perception of dissatisfaction among their patients to pre-arthroplasty finger contractures (observed in all five patients) and patients' sclerotic bones.

The median DASH score of 22.55 observed in the study suggests that performing daily tasks and activities was associated with a certain degree of disability for some of the participants. This seems to align with reviews conducted by other authors12,18,19. McGuire et al16 argued that functional scores don't offer a meaningful interpretation in a progressive polyarthritic condition like osteoarthritis. McGuire and colleagues16 are of the opinion that postoperative improvement in one particular joint of the hand may not be a reflection of improvements in the functional score as the diseased adjacent fingers may affect pain levels and skew the result. Contrary to this opinion, Dieppe and Lohmander31, submitted that reduction in pain may improve movement and functional ability.

According to Tagil et al12, pain and stiffness remain the major indications for almost every osteoarthritic procedure but overall hand function would likely improve when pain-free movement at the PIPJ is restored or maintained. Further, when tasks considered important to the patient are performed with ease and minimal pain, a higher satisfaction score can be expected32. The finding regarding participants who underwent arthroplasty once having significantly higher satisfaction scores than those who had a repeat surgery suggests that not having need for a repeat surgery is linked with lesser post-surgical complications and associated impaired hand functions. Watts et al18 found factors like stiffness (due to postsurgi-cal complications), deformity and other issues like retained sutures as reasons for repeat surgery among patients who had pyrocarbon PIP joint arthroplasty. Findings from a related study33 also showed that unplanned re-operation was independently associated with younger age, surgeon inexperience, and index procedure type among patients who had trapeziometacarpal arthroplasty.

Consistent pain relief and reduction of preoperative pain appear to be the most uniform finding in published literature9,16,18,25. The significant reduction in pain observed in this study may be directly attributed to arthroplasty which involves removal of subchondral bone cysts and osteophytes along the articular joint surfaces of the arthritic PIPJ33. Pyrocarbon arthroplasty has been associated with decreased pain by the majority of previous studies9,11,13,14.

A statistically significant increase (median increase of 220) in ROM of PIP joint observed in this study suggests that PIP joint pyrocarbon arthroplasty is also beneficial regarding the outcome. Improvement in ROM is an anticipated and expected postoperative outcome. However, it is important to consider the extent or magnitude of the recorded increase in ROM. It is clinically relevant to identify whether ROM follows a trend of plateauing, increasing or decreasing over a period of time.

Herren et al13 reported an increase of 8 degrees with a mean follow-up of 19 months. The retrospective review of 50 pyrocarbon PIP joints arthroplasty in 35 subjects at a 27-month follow-up by Bravo et a19 showed an insignificant ROM increase of 7 degrees. Wijk et al5 and Nunley et a19 both reported a decrease in active range of movement, -8 degrees and -2 degrees respectively. Watts et al18 did not find a significant difference in ROM following a retrospective review on 97 pyrocarbon PIP joint arthroplasties at a five-year follow-up. The findings of the highlighted authors seem inconsistent with the results of the present study. Interrater assessments and differences in duration of follow-up assessments may have accounted for the observed difference. Perhaps, a prospective study with intra assessor assessments could be an investigation for future perspective in this regard.

Active ROM at 6 months and final assessment were comparable. This finding is in agreement with the report of Reissner et al19 which indicated that postoperative findings may show a decrease or plateau in ROM at a longer follow-up period19. The plateau in AROM has been attributed to a combination of scar tissue formation and patients decreasing their exercise intensity and frequency35.

Limitations

The follow-up time of about 18 months appears relatively short and not conducive for detection of deformity and/or a decrease in the active range of movement at the PIPJ as most complications are expected to occur beyond 2 years post-surgery. The small sample size and convenient sampling from a single clinic may limit the generalisability of results. Another limitation of this study is that pain was not assessed at the 6th month follow-up because the record was not available for review. In addition, there were no pre-operative satisfaction and DASH scores assessments according to available records.

Patients were treated and assessed by more than one therapist and the time of final follow-up was not the same for all participants; these could have impacted the validity of the findings.

CONCLUSION

Pyrocarbon proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty improved treatment outcomes regarding pain and range of motion. However, perception of dissatisfaction was relatively high while perception of disability appeared mild among patients who had PIP joint py-rocarbon arthroplasty. A patient having a repeat surgery is a likely predictor of post-operative level of satisfaction and should be considered in planning of rehabilitation programmes for patients who underwent pyrocarbon proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty.

A qualitative study may be necessitated to identify reasons why patients were not satisfied with the outcome of the surgical procedures carried out on their fingers. Future researchers should consider conducting a prospective cohort study with intra assessor assessments to examine clinical changes in the outcomes of patient satisfaction and hand function.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N. Hendricks, N. Thayananthee and N. Chemane conceptualized the study and were involved in data acquisition; O.M. Olagbegi performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript. N. Thayan-anthee and O.M. Olagbegi critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all patients who participated in the study.

REFERENCES

1. McPhee SD. Functional hand evolution: A review. Am Journal Occup Ther. 1987; 41(3): 158-63. [ Links ]

2. Chiasson CE, Zhang Y, Sharma L, Kannel W, Felson DT. Grip strength and the risk of developing radiographic hand OA: results from the Framingham study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001; 42 (1): 33-38. [ Links ]

3. Lewis AR, Nolan MJ, Hodgson RJ, Benjamin M, Ralphs JR, Archer, CW, Tyler JA, Hall, LD. High resolution magnetic imaging of the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint: Correlation with histology and production of three-dimensional data set. J Hand Surg Eur. 1996; 21(4): 488-495. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-7681(96)80053-2 [ Links ]

4. Sweets TM, Stern PJ. 2011). Pyrolytic carbon resurfacing arthro-plasty for osteoarthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint of the finger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011; 93(15): 1417-25. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.J.00832 [ Links ]

5. Wijk U, Wollmark M, Kopylov P Tãgil M. Outcomes of Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Pyrocarbon Implants. J Hand Surg. 2010; 35(1): 38-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.08.010 [ Links ]

6. Ng M, Clarkson J, Wilmshurst A. Pyrocarbon proximal interphalangeal arthroplasty: Outcome audit in patient's environment. Internet J Hand Surg. 2006; 1: 1-7. https://print.ispub.com/api/0/ispub-article/8404 [ Links ]

7. Chung KC, Ram A, Shauver M. Outcomes of pyrolytic carbon arthroplasty for the proximal interphalangeal joint. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 123 (5): 1521-1532. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a2059b [ Links ]

8. Rizzo M. Metacarpophalangeal joint arthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2011; 36(2): 345-53.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.11.035 [ Links ]

9. Bravo CJ, Rizzo M, Hormel, KB, Beckenbaugh RD. Pyrolytic carbon proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty: Results with a minimum 2-year follow-up evaluation. Am J Hand Surg. 2007;32(1): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.10.017 [ Links ]

10. Dickson DR Nuttall D, Watts AC, Talwalkar SC, Hayton M, Trail IA. Pyrocarbon Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Arthroplasty: Minimum Five-Year Follow-Up. The J Hand Surg. 2015; 40(1 l): 2142-2148.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.08.009 [ Links ]

11. Meier R Schultz M, Krimmer H, Stutz N, Lanz U. Proximal interphalangeal joint replacement with pyrolytic carbon prosthesis. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007; 19: I-15. [ Links ]

12. Tagil M, Geijer M, Abramo A, Kopylov P Ten years' experience with a pyrocarbon prosthesis replacing the proximal interphalangeal joint. A prospective clinical and radiographic follow-up. J Hand Surg (Eur Vol). 2014; 39(6): 587-595. https://doi.org/10.l177/17531934l3479527 [ Links ]

13. Herren DB, Schindele S, Goldhahn, J, Simmen, BR. Problematic bone fixation with pyrocarbon implants in proximal interphalangeal joint replacement: short-term results. Br Journal Hand Surg. 2006; 31: 643-51 [ Links ]

14. Nunley RM, Boyer MI, Goldfarb CA. Pyrolytic Carbon Arthroplasty for post traumatic arthritis. J Hand Surg (Am volume). 2006; 31(9):1468-1472. [ Links ]

15. Tuttle HG, Stern PJ. Pyrolytic carbon proximal phalangeal joint resurfacing arthroplasty. J Hand Surg (Am volume). 2006; 3 1A: 930-93 [ Links ]

16. McGuire DT, White CD, Carter SL, Solomons MW. Pyrocarbon proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty: outcomes of a cohort study. J Hand Surg (Eur Vol). 2012; 37(6): 490-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193411434053 [ Links ]

17. Jordaan PW, McGuire D, Solomons MW. Surface Replacement Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Arthroplasty: A Case Series. HAND. 155894471876003. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558944718760035 [ Links ]

18. Watts AC, Hearnden AJ, Trail IA, Hayton MJ, Nuttall D, Stanley JK. Pyrocarbon proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty: Minimum two-year follow-up. J Hand Surg. 2012; 37(5): 882-888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.02.012 [ Links ]

19. Reissner, L., Schindele, S., Hensler, S., Marks, M., & Herren, D. B. (2014). Ten year follow-up of pyrocarbon implants for proximal interphalangeal joint replacement. J Hand Surg (Eur Vol). 2014; 39(6): 582-586. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193413511922 [ Links ]

20. Brokelman RB, Haverkamp D, van Loon C, Hol A, van Kampen A, Veth R. The validation of the visual analogue scale for patient satisfaction after total hip arthroplasty. Eur Orthop Traumatol. 2012; 3(2): 101-105. [ Links ]

21. Groth GN, VanDeven KM, Phillips EC, Ehretsman RL. Goniometry of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints, Part II: placement, preferences, interrater reliability, and concurrent validity. J Hand Ther. 2001; 14(1): 23-9. [ Links ]

22. Beaton DE, Davis AM, Hudak P Mconnel S. The DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) outcome measure: What do we know about it now? Br J Hand Ther. 2001; 6 (4), 109-118. [ Links ]

23. SooHoo NF McDonald AP Seiler JG, McGillivary GR. Evaluation of the construct validity of the DASH questionnaire by correlation to the SF-36. J Hand Surg (Am Volume). 2002; 27(3): 537-41. [ Links ]

24. Pellant J. SPSS survival manual. A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. 6th edition. Berkshire, England, McGraw Hill Education; 2016. [ Links ]

25. Branam BR, Tuttle HG, Stern PJ, Levin L. Resurfacing arthroplasty versus silicone arthroplasty for proximal interphalangeal joint os-teoarthritis. J Hand Surg. 2007; 32(6): 775-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.04.006 [ Links ]

26. Mashhadi SA, Chandrasekharan L, Pickford MA. Pyrolytic carbon arthroplasty for the proximal interphalangeal joint: results after minimum 3 years of follow-up. J Hand Surg (Eur Vol). 2012; 37(6): 501-5. https://doi.org/10.1177/17531934l2443044 [ Links ]

27. Srikanth VK., FryerJL, Zhai G, Winzenberg TM, Hosmer D, Jones G. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005; 13(9): 769-781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.0l4 [ Links ]

28. Storey PA, Goddard M, Clegg C, Birks ME, Bostock SH. Pyrocarbon proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasty: a medium to long term follow-up of a single surgeon series. J Hand Surg (Eur Vol). 2015; 40(9): 952-956.https://doi.org/10.1177/I7531934I4566552 [ Links ]

29. Wagner ER, Luo TD, Houdek MT, Kor DJ, Moran SL, Rizzo M. (2015). Revision proximal interphalangeal arthroplasty: An outcome analysis of 75 consecutive cases. J Hand Surg. 2015; 40(10): 1949-1955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.05.015 [ Links ]

30. Riggs JM, Lyden AK, Chung KC, Murphy SL. Static versus dynamic splinting for proximal interphalangeal joint pyrocarbon implant ar-throplasty: A comparison of current and historical cohorts. J Hand Ther. 2011; 24: 231-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2011.03.003 [ Links ]

31. Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2005; 365 (9463): 965-973. [ Links ]

32. Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, Stewart D, Rigby P Letts L. The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: A Transactive Approach to Occupational Performance. Canadian J Occup Ther.1996; 63(I): 9-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103 [ Links ]

33. Wilkens SC, Xue Z, Mellema JJ, Ring D, Chen N. Unplanned reop-eration after trapeziometacarpal arthroplasty: rate, reasons, and risk factors. HAND. 2016; 12(5): 446-452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558944716679605 [ Links ]

34. Goldring SR, Goldring MB. Clinical aspects, pathology and patho-physiology of osteoarthritis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006; (6): 376-378. [ Links ]

35. Yang G, McGlinn EP, Chung KC. Management of the stiff finger: evidence and outcomes. Clin Plast Surg. 2014; 41(3): 501-512. https://doi.prg/10.1016/j.cps.2014.03.011] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

OM Olagbegi

Email: olagbegioladapo@yahoo.com