Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Occupational Therapy

versão On-line ISSN 2310-3833

versão impressa ISSN 0038-2337

S. Afr. j. occup. ther. vol.49 no.3 Pretoria Dez. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2019/vol49n3a6

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES

Medical Incapacity Management in the South African Private Industrial Sector: The role of the occupational therapist

Ravashni GovenderI, *; Pragashnie GovenderII; December MpanzaIII

IBOccTh (UKZN); DHT (UP); MOT (UKZN) Private Practitioner. https://orcid.org/0000=0003-3083-4973

IIBOccTh (UDW); MOT (UKZN); PhD (UKZN) Associate Professor, Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Allied Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu Natal. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3155-3743

IIIBOT (UKZN); MOT (UKZN) Lecturer, Discipline of Occupational Therapy, School of Allied Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu Natal. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2777-9256

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Occupational therapists working in the field of occupational health in South African private industrial sectors may find themselves involved in management of medical incapacity due to their expertise in vocational rehabilitation

AIM: In this study, the authors explored how South African Acts guide the role and scope of occupational therapists in medical incapacity management, in addition to determining the scope, role and value of occupational therapy in medical incapacity management from the perspectives of occupational therapists currently working in the field

METHOD: An exploratory qualitative design with use of two concurrent methods of data collection (document analysis and semi structured interviews) was undertaken. Data were analysed thematically, via deductive reasoning, and pooled to provide a picture of how occupational therapists can function within medical incapacity management

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: Six themes emerged from the data. Occupational therapists' role and scope within legislature appears to lack detail with a disjuncture between legislation that guides medical incapacity management and current practice of occupational therapists. Notwithstanding this, the findings of this study show that occupational therapists play a critical role within management of medical incapacity.

Key words: Vocational rehabilitation, medical incapacity management, occupational therapy

INTRODUCTION

"Incapacity management is the investigation, evaluation, management and reasonable accommodation of employees that are not able to perform their duties at the required standard due to a chronic or acute health challenge"l .

South African legislation directs and offers guidelines to employers and employees on how medical incapacity management (MIM) should be carried out via two national departments2,3. The Department of Mineral Resources governs mines through the Mine Health and Safety Act and the Department of Labour governs other sectors through the Occupational Health and Safety Act2,3. MIM occurs in both public and private industrial settings, and is guided by the nature of the industry. As such, involvement of stakeholders from various disciplines are included within the process. Occupational therapists working in the field of Occupational Health in South Africa may find themselves involved in the process of MIM due to their expertise in the field of vocational rehabilitation4 but their role may not be clearly defined and their contribution in this area of practice may not be well recognised. Moreover, there does not appear to be research into the way in which South African Occupational Health legislation guides occupational therapy in MIM.

In this study, the authors aimed to explore how legislation guides the occupational therapist's scope and role in MIM in the private industrial sector, as well as the current role and scope and perceived value of occupational therapy in MIM in the private industrial sector from the perspectives of occupational therapists working in vocational rehabilitation.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Occupational Therapy and Vocational Rehabilitation within the South African and International arena

Within Occupational Therapy work evaluation, the occupational therapist integrates information pertaining to the employee's physical, psychological and behavioural characteristics4 as well as the intricate relationship between the employee's attributes, the work demands, the work environment and psychosocial aspects5. The inclusion of these aspects contribute to comprehensive interventions geared towards ensuring that an employee can be involved in work activities post illness, injury or disability. A study by Buys6, on identifying key professional competencies of South African occupational therapists working in vocational rehabilitation, highlighted that occupational therapists need to display a good understanding of the medical condition and the impact it may have on work. Additionally, occupational therapists should be involved in case/ disability management and disability prevention, be able to assist with placement of persons with disabilities, understand legislation surrounding the occupational therapist's role in vocational rehabilitation, be competent in written and verbal communication with all stakeholders, and be able to carry out a comprehensive evaluation of the employee. Furthermore, occupational therapists should be able to provide appropriate recommendations, perform job analyses, develop return-to-work intervention plans, ensure follow up to establish successful return to work and have good clinical reasoning. An extension of these roles include involvement in health and injury promotion and prevention by providing education on ergonomics and pain management; advice on changes to the work environment and work duties; work hardening and conditioning programmes; and working within a multidisciplinary team to achieve return to work goals for the employee7.

Byrne8, in his study on the role of occupational therapists in the South African group life insurance industry, stated that future roles of occupational therapists in an industrial environment may include aiding employers with compliance to labour law; assisting with case management; vocational rehabilitation; and in advocacy for employees. In the case management role, the occupational therapist would facilitate return to work by collaborating with stakeholders and coordinating and evaluating the return to work programme9. The role of a case manager within vocational rehabilitation appears to be new and details about how and when occupational therapists can be involved is unavailable, indicating a need for further exploration. Buys6, Byrne8, Larson and Ellexson7 provide a clear outline of competencies, role and value for occupational therapy involvement in vocational rehabilitation. However, the role and scope of occupational therapy still seems to be not well recognised in MIM in the private industrial sector, which affects the inclusion of the occupational therapist within the process.

Occupational Therapy Scope within South African Legislation

The Health Professions Council of South Africa' (HPCSA) Scope of Profession for occupational therapists is outlined as the:

"evaluation, improvement or maintenance of the health, development, functional performance and self-assertion of those in whom these are impaired or at risk, through the prescription and guidance of the patient's or client's participation in normal activities, together with the application of appropriate techniques preceding or during participation in normal activities which facilitate such participation"101.

Guidance for the scope and role of occupational therapists in MIM, would prove difficult to extract from this statement, as the purpose of this statement is to provide a generic description of all categories of occupational therapy intervention and is therefore not meant to inform specific roles in different categories of occupational therapy practice.

Currently, there is a paucity of literature guiding occupational therapists in the private industrial sector, on their role and scope in MIM, and thus it would prove necessary to identify the occupational therapist's role and scope as set out in current South African MIM legislature as well as from their own perspectives to establish a stance.

The validation of occupational therapy, by an illumination of its role and scope in MIM is a valuable exercise in that it has the ability to empower occupational therapists in their role within the private industrial sector. Over time, the scope of occupational therapy practice within the occupational health field has expanded, and with this change, comes new knowledge and expertise. It is anticipated that the outcome of this research study will (a) contribute to growth and exchange of knowledge about current practice of occupational therapists in MIM, (b) create awareness of the value of occupational therapy within MIM, (c) inform legislation on the role, scope and value of occupational therapy in South Africa in MIM and, (d) contribute to building awareness of the critical role occupational therapists play within MIM in the private industrial sector.

METHODS

Study Design

An exploratory qualitative design11 was used with two concurrent methods of data collection.

Selection and Sampling strategy

Sampling and retrieval of South African legislation, policies and guideline documents occurred via a Google search to identify South African legislative documents, policies and/or guidelines that are applicable to MIM in the private industrial sector. Figure 1 below highlights the process followed. Sixteen documents were retrieved that included the terms related to "medical incapacity management in South Africa". Further reduction occurred via scanning of the documents, to determine which of these included terms related to "occupational therapy and/or occupational therapist and/or rehabilitation". Based on this reduction, only three documents were eligible for analysis. Table I (page 32) provides a description of the selected documents.

Opinions on scope, role and value were gathered from occupational therapists in South Africa who have worked, or are currently working for South African companies or vocational rehabilitation practices that offer a service to companies in the private industrial sector and who have experience in MIM. Occupational therapists were invited to participate in the study by email, telephone and verbal communication.

Data Collection

To gather opinions of occupational therapists on their role, scope and value in MIM in South Africa, an initial interview schedule was developed. This was piloted on two Occupational Therapists who met the inclusion criteria. The pilot study aimed to scrutinise the interview questions for ambiguity and to ensure that questions yielded information relevant to the research study. Revision of the interview schedule involved re-ordering of questions and removal of questions that were either redundant or not directly linked to the purpose of the study. Data redun-dancy15 was achieved following eight interviews with the revised interview schedule. Each participant was required to complete a separate biographical information questionnaire prior to the face-to-face interview.

Data Analysis

Data from the South African Acts were analysed using thematic analysis, in which data extracted from documents were grouped according to codes, subthemes and themes. Interview transcripts were compiled verbatim followed by thematic analysis16. All authors ensured coding consistency by individually coding one interview transcript. Once inconsistencies in method was identified and resolved, all transcripts were analysed and reviewed by all authors. Identified codes, sub- themes and themes were then categorised in Microsoft Excel version 2016.

Ensuring Trustworthiness in the Study

To ensure credibility, clear guidelines were set prior to analysing the data and the data were reviewed by all authors to ensure that the correct processes were followed17. Transferability was ensured by providing readers with a description of the context and the research methods18. Information about research methods and a document trail ensured dependability18.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from a Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSS/0986/017M) prior to data collection. Each participant received an information letter outlining details of the research study and written consent was obtained prior to involvement in the study. Participant personal information was stored safely and securely (electronic documents were password protected and hardcopies were stored in a locked cabinet). All identifying information for participants were excluded in descriptions. The place of employment was only in reference to the PI of this study (R Govender).

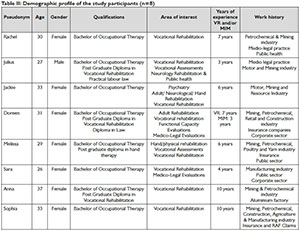

Table II (below) displays the demographic characteristics of the participants.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The sample comprised of eight participants, of which seven were female. Participant ages ranged between 26 to 37 years with a mean age of 30.75 years. Participants' experience in vocational rehabilitation and MIM ranged from three to 10 years, with a mean of seven years' experience. Participants worked in various private industrial sectors, including petrochemical, mining, motor, retail, construction and agriculture.

Collectively, from a review of the three South African Acts and the eight interview transcripts, six major themes emerged in this study, and are presented with their respective sub-themes supported by verbatim quotes.

THEME ONE: LEGISLATIVE GUIDELINES

Assessment for Return to Work

Legislation states that occupational therapists perform work assessments to establish suitability for further rehabilitation.

"The possibility of further medical treatment available and the expected response to such treatment has to be taken into account to evaluate an employee's ability to improve on the existing functional and work capacity assessment results". (S.8(l)(4)(l) of the Mine Health and Safety Act code of practice on MIM)l3.

Early return to work decisions are informed by a multidisci-plinary approach and the occupational medical practitioner should consult with a "safety specialist, occupational hygienist, occupational therapist, treating specialists, clinical psychologist, etc". (S.8(l)(5) (2) of the Mine Health and Safety Act code of practice on MIM)l3.

Rehabilitation professionals that may assist with return to work recommendations include the following:

"Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy and Biokineticist functionality evaluation reports may assist the occupational medical practitioner with fitness to work recommendations". (S.8 (5)(8) Mine Health and Safety Act code of practice on minimum standards of fitness)1420.

Additionally, occupational therapists should be consulted when identifying suitable occupations for persons with disabilities in companies.

"The employer could seek guidance from organizations that represent people with disabilities or relevant experts, for example in vocational rehabilitation and Occupational Therapy". (S.l6(4) Employment Equity Act code of practice on employment of Persons with Disabilities)1223.

Although Occupational Therapy services in MIM is recognised in the South African Acts, clear and detailed description of the occupational therapist's role and scope is not included. Moreover, the description of Occupational Therapy in MIM legislation does not encompass the whole range of professional competencies of occupational therapists6. The role and scope of occupational therapists in MIM legislation should ideally match current practices in South Africa, as well as actual competencies of occupational therapists. The inclusion of these specifics in the legislation will both guide occupational therapists' practice in this field, and stakeholders on how and when occupational therapy services should be used. The inadequate descriptions or lack of professional specific information might be suggestive of poor professional consultation or due to changes and/or expansion in professional scope following compilation of this legislation.

THEME TWO: THE OCCUPATIONAL THERAPIST: EXPERT IN ENABLING OCCUPATION

Continuum of Evaluation and Intervention

One participant referred to occupational therapists as Occupation analysts" (Julius1), when he was invited to contribute his understanding on the role and scope of occupational therapists in MIM. All participants (n=8) indicated that Occupational Therapy assessments are 'holistic', and information is gathered to get the "bigger picture" and that "an evaluation is performed to assess impact of disability or impairment on function" (Julius). An Occupational Therapy evaluation was said to include:

• an interview, which provides in-depth information about the patient (Melissa)

• an assessment of activities of daily living in the work sphere (Rachel)

• functional capacity evaluations (Sophia)

• identification of return to work barriers (Sophia)

• work site visits to perform job analysis (Rachel)

• to establish reasonable accommodation options and ergonomic assessments (Rachel)

• identifying injury risk in the workplace and absenteeism management (Sara).

The intervention process was said to entail carrying out:

vocational rehabilitation, work conditioning or work hardening, remediation and rehabilitation of skills, post-acute management, post upper limb rehabilitation (Julius), education on ergonomics and lifting techniques, assistance with reasonable accommodation and disability sensitivity training (Sophia).

Recommendations within the intervention process may be provided by an occupational therapist to guide; re-deployment, return to work, to inform compensation claims and to inform stakeholders if further rehabilitation is required (Rachel). Recommendations were remarked to be ...realistic and I normally try to make it as practical for the job... (Jackie).

Contextualising the Role of Occupational Therapy in MIM

Within the MIM process, the occupational therapist liaises with several stakeholders as indicated by Sophia:

...the patient, the employer that might be his direct line management or higher up, his management, human resources the Doctor or the occupational medical practitioner or the occupational health nurse depending on the company that you work... and ...if they want the unions involved...someone that is familiar with the design of the processes or a hygienist.

Jackie and Doreen added that clients are referred from either insurance companies or occupational medical practitioners respectively.

A differentiation between in-house (exclusively working for industrial company) and out-house occupational therapy services (works for various industrial companies) in MIM were made by all participants. Rachel expressed that:

Occupational therapists who work in-house have better access to patients, the work environment and is better able to monitor rehabilitation.

Consistency in type of assessments used and recommendation outcomes were reported in in-house occupational therapists due to use of 'standardised' assessment tools.

Melissa expressed that better access to patients and stakeholders, ensured that recommendations are followed up and are carried out appropriately:

...ff you're on the inside...I think you have better access...

Working exclusively for an industrial company allows the occupational therapist to build a relationship with stakeholders. In addition, the therapist is exposed to company or industry-specific ways of working as well as company policies:

...Because you kinda know the role players a little better, so it makes it a lot easier if you (are) actually inside the company... (Melissa)

I think you would be more hands on if you are in-house, you learn the company's policies and procedures better... (Jackie)

Contrary to the previous statements, Julius and Doreen indicated that working as an independent occupational therapist, ensured that potential bias towards the company is eliminated, due to possible limited knowledge of company policies:

.when you are outsourced by a company. what you put in the report will not be influenced by the company politics, procedure. (Julius)

Contextual Barriers to Occupational Therapy Practice

Participants reported that the role and scope of occupational therapy in medical incapacity legislation is vague (Sophia), a bit broad (Jackie) and insufficient (Doreen). Additionally, all participants reported a lack of knowledge by stakeholders about the role of occupational therapy in MIM. The resultant impact of stakeholders' lack of knowledge of occupational therapy results in poor utilisation and recognition of the scope and role of occupational therapy with MIM. Occupational therapists experience negative attitudes from employers as their involvement is not mandated in MIM legislation; and occupational therapists need to gain stakeholder trust to ensure continued inclusion. One participant indicated that stakeholders were not willing to pay for services as they viewed occupational therapy as a luxury service (Sophia).

These responses from occupational therapist participants in this study were in keeping with literature that indicate that occupational therapists evaluate the employee, occupation, the environment and the interaction thereof4,6,19. All participants in the study emphasised the importance of the occupational therapist gaining a holistic view of the employee during the assessment process which is considered the core of occupational therapy practice5.

Participants indicated that occupational therapy practice differs and is influenced by context and environment. To make good clinical decisions in the MIM process, knowing the environment and context and identification of return to work barriers is vital as it shapes intervention strategies. Participants in this study expressed a willingness to follow through with return to work however contextual barriers such as poor implementation or implementation of recommendations without occupational therapy consultation was often experienced. Additionally, a lack of acknowledge of occupational therapists by stakeholder's are often experienced due to their lack of knowledge of the role and scope of occupational therapists. This study therefore adds to the current knowledge of organisational and contextual factors that restrict occupational therapists in utilising their skills set within vocational rehabilitation settings and more specifically in MIM20.

THEME 3: COLLABORATOR AND COMMUNICATOR

Case Management

Participants indicated that when occupational therapists are assigned the role of a case manager, they ensure that; (a) stakeholder meetings are arranged (Sophia), (b) legislative guidelines are followed by stakeholders (Sara), (c) goal setting is guided (Anna) and (d) there is stakeholder role clarification (Melissa). When reporting to a case manager, the occupational therapist provides feedback on occupational therapy recommendations through meetings, or written communication (such as the medical file). In supporting return to work, the occupational therapist will offer support to employers on the implementation of recommendations, assist with resolution of return to work barriers, and offer post-placement follow-up by communicating with employers and employees.

Patient and Family Intervention

Providing relevant information and education for the patient and his/her family, was indicated as essential in ensuring adherence to treatment and monitoring needs within the process:

...giving the relevant details to the patient....or giving it to their families and you know giving them all the relevant information that they would be required... (Rachel)

Occupational therapists as collaborators and communicators recognise that successful return to work outcomes lay in the collaboration and co-operation of all stakeholders within the process. Communication is facilitated by occupational therapists by documenting intervention and offering support and advise to stakeholders2l,22.

THEME FOUR: CHANGE AGENT AND PRACTICE MANAGER

Advocacy to Effect Change in the Workplace

Occupational therapists should encourage companies to create an inclusive work force by eliminating obstacles to productivity (Anna) for persons with disability. Participants noted that their roles extended to effecting change in policy for persons with disability, as part of their own advocacy role:

Occupational therapists can also get involved in companies directly. Taking on advisory roles when drafting workplace policies that affect persons with disability. (Anna).

Patient Education and Empowerment

Participants indicated that empowerment of patients occur through education on their rights and assessment outcomes:

...we don't just write the report we always give feedback to the client... (Melissa).

The occupational therapist should be the advocate for the patient's rights... This includes giving the patient the best possible rehabilitative care (within the scope of practice of the occupational therapist), educating the patient on their rights. (Anna).

Advocate for the Occupational Therapy Profession

Occupational therapists own their role within MIM by using evidence based practice:

I was able to prove most of my reasoning with research (Sara), by showing stakeholders the value of occupational therapy in practice; the more easier straight forward cases sort of proved the value of occupational therapy and then that got carried over to more difficult cases, to keep them on board (Sara) and .collaboration between occupational therapists ... (Anna) to achieve alignment.

In the change agent role, advocacy is the key to ensuring changes within the workplace and empowerment of the employee, this is done to support and encourage the employee's occupational performance23. This is facilitated by affecting change on a policy level, being involved in and initiating health initiatives, implementing research projects that improve the health and well-being of em-ployees5. Within the practice manager role, occupational therapists need to be proactive in advocating for the profession by ensuring successful outcome in return to work by integration of evidence based practice, expert skills, client factors and context24.

THEME FIVE: SCHOLAR ENSURING CONTINUOUS PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Knowledge of Legislation in Practice

Participants expressed the need for occupational therapists to be aware of and educate themselves on legislation guiding MIM when working in vocational rehabilitation. They highlighted that; we can back up our reasoning for making recommendations based on legislation (Rachel) and ...the occupational therapist should be very familiar with these pieces of legislation, because she can use this to negotiate with the employer (Anna).

Preparedness and Gaps in Practice and Training in MIM

Participants expressed that occupational therapists need to prepare themselves for practice by; attending relevant courses (Melissa), through reading legislation and vocational rehabilitation material (Rachel), and onsite training and learning from experienced therapists (Sara). Participants shared concerns that they initially did not feel prepared working within MIM due to lack of awareness of legislation related to MIM and lack of experience and exposure. Melissa shared, we did not do that much legislation especially in terms of work, disability and you know medical incapacity type of legislation. Sara indicated that there should be development of a formal qualification in case management to assist with practice. Participants alluded to undergraduate training as not sufficiently preparing them for work in MIM and re-iterated the importance of relevant post-graduate qualifications.

Within the scholar role, occupational therapists need to be aware of legislation that guides their practice25 and contribute to professional development through courses and mentoring26. Studies indicate that continuous professional activities not only improve skills and knowledge but also improve job performance27.

THEME SIX: PROFESSIONALISM

Current Professional Identity in MIM

Rachel indicated that she felt that companies valued our opinion and that occupational therapist's recommendations play a crucial role in the decisions that are made around the employees. The concept of professionalism in occupational therapy is regarded as an overlap between competencies, behaviour and values28. Creating a professional identity within MIM, is entrenched in core values of occupational therapy found in concepts of client centred practice and occupation-focused interventions29.

Value of Occupational Therapy in MIM

The value of occupational therapy in MIM is illustrated through characteristics found in occupational therapists in current practice. The characteristics that an occupational therapist working in MIM should encompass is detailed in Table III below, as expressed by the participants in this study.

CONCLUSION

South African legislature guiding MIM encourages early return to work, removal of return to work barriers and encourages a reduction of the impact of disability by implementation of reasonable accommodation strategies within MIM13,14. The emphasis is on creating an inclusive productive workforce so that employees, who suffer from illness, injury or disability, while in employment, are not hindered in return to work. While it is evident that key features to guide MIM appear in relevant legislature, there are concerns that the short or inadequate descriptions of professions such as

Occupational therapy, is suggestive of a reduced understanding of the professional role and scope of occupational therapists by policy makers and stakeholders. In everyday practice, this has significant implications for occupational therapists working in MIM in the South African private industrial sector. Results from this study indicate that occupational therapists working in the field of vocational rehabilitation are well positioned to assist in MIM. Relevant undergraduate training and education, through on the job training, equips occupational therapists with a unique ability to assess the interrelated nature of person, environment and occupation factors through evidence based methods5,6,19,30. Therefore, ensuring a clear role and scope within MIM will not only ensure that occupational therapists apply themselves appropriately, but will ensure that stakeholders utilise the services of occupational therapists aptly and optimally.

AUTHOR'S CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were responsible for the conceptualisation of the study. R.G. was the primary researcher with PG. and D.M. serving as supervisors of the study. R.G. drafted the initial manuscript and P.G. and D.M. provided critical review. R.G. and PG. were responsible for amendments through the review process. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. EOH Health Solutions. Absenteeism, Incapacity and Disability Management. 2019 <http://www.eohworkplacehealth.co.za/absenteeism-incapacity-and-disability-management> (22 September 2019). [ Links ]

2. Department of Mineral Resources. Mine Health and Safety Act, 1996 (No.29 of 1996) [Internet]. <https://www.miningsafety.co.za/mininglaws?p=l&sp=&ssp=&ssspsssp=> (22 September 2019) [ Links ]

3. Department of Labour. Occupational Health and Safety Act, 1993 (No. 85 of 1993) [Internet].<https://www.gov.za/documents/occupational-health-and-safety-act> (22 September 2019) [ Links ]

4. Bade S, Eckert J. Occupational Therapists' Expertise in Work Rehabilitation and Ergonomics. Work. 2008; 31(1): 1-3. [ Links ]

5. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. CAOT Position Statement Occupational Therapy and Workplace Health. [Internet].2015. <https://caot.inltouch.org/document/3709/O-OTandWorkplaceHealth.pdf> [ Links ]

6. Buys T. Professional competencies in vocational rehabilitation: Results of a Delphi study. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 45(3): 48-54. http://dx.doi.org/l0.l7l59/2310-3833/2015/v45n3/a9 [ Links ]

7. Larson B, Ellexson M. Occupational therapy services in facilitating work performance. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2005; 59(6): 676-9. https://doi.org/l0.50l4/ajot.59.6.676 [ Links ]

8. Byrne LJ. The Current and Future Role of Occupational Therapists in the South African Group Life Insurance Industry (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria). 2001. <https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/30255/0ldissertation.pdf?sequence=l> [ Links ]

9. Jensen S. The role of case management and care coordination in improving employee health and productivity. Professional case management. 2012; 17(6): 294-6. https://l0.l097/NCM.0b0l3e31826c83dl [ Links ]

10. Department of Health. Health Professions Act 56 of1974. Regulations defining the Scope of the Profession of Occupational Therapy [Internet]. 1992. <http://www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/editor/UserFiles/downloads/legislations/ regulations/ocp/regulations/regulations_gnr2l45_92.pdf> [ Links ]

11. Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications; 2017. [ Links ]

12. Department of Labour. Employment Equity Act, 1998 (No.55 of 1998). Code of Good Practice on the Employment of Persons with Disabilities [Internet]. 2015. <http://www.sapayroll.co.za/Portals/l2/Documents/TaxIn-fo/2015/38872_gen58l-EmploymentEquity-PersonswithDisabilitiesCodeofGoodPractice.pdf> [ Links ]

13. Department of Mineral Resources. Mine Health and Safety Act, 1996 (No. 29 of 1996). Guideline for a Mandatory Code of Practice for the Management of Medical Incapacity due to IIl-health and Injury [Internet]. 2016.. <http://eohlegalservices.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016./02/MHSA-Management-of-Incapacity.pdf> [ Links ]

14. Department of Mineral Resources. Mine Health and Safety Act, 1996 (No.29 of 1996). Guideline for a Mandatory Code of Practice on the Minimum Standards of Fitness to Perform Work on a Mine [Internet]. 2016.. <https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/39656_rgl0556_gonl47_.pdf> [ Links ]

15. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oakes. 2015. [ Links ]

16. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008; 62(1): 107-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.l365-2648.2007.04569.x [ Links ]

17. Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in nursing science. 1993 Dec;16(2):1-8. https://doi.org/l0.l097/000l2272-199312000-00002. [ Links ]

18. Gunawan J. Ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research. Belitung Nursing Journal. 2015 Dec 7;1(1): 10-1. [ Links ]

19. Joss M. Occupational Therapists and Returns to Work. Personnel Today. [Internet]. 2010. <https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/occupational-therapists-and-returns-to-work/> (2 April 2018) [ Links ]

20. Ver Loren Van Themaat DC. The practice profile of occupational therapists delivering work practice services in South Africa. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town). 2015. <https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/l5764/thesis_hsf_2015_ver_lor en_van_themaat_dorita_cornelia. pdf?sequence=l> [ Links ]

21. Coole C, Radford K, Grant M, Terry J. Returning to Work after Stroke: Perspectives of Employer Stakeholders: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2013; 23(3): 406-18. https://doi.org/l0.l007/sl0926-0l2-940l-l [ Links ]

22. Clark GF Youngstrom MJ. Guidelines for Documentation of Occupational Therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2008; 62(6): 684. [ Links ]

23. Dhillon SK, Wilkins S, Law MC, Stewart DA, Tremblay M. Advocacy in Occupational Therapy: Exploring Clinicians' Reasons and Experiences of Advocacy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010; 77(4): 24l-8. https://doi.org/l0.2l82/cjot.2010.77.4.6 [ Links ]

24. Occupational Therapy Australia. Occupational Therapy Scope of Practice Framework 2017. [Internet]. <https://www.otaus.com.au/sitebuilder/advocacy/knowledge/asset/files/2l/occupationalthe-rapyscopeofpracticeframeworkl3june2017.pdf> (28 May 2018) [ Links ]

25. Van Der Reyden D. Legislation for everyday occupational Therapy practice. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2010; 40(3): 27-35. [ Links ]

26. Johnson Coffelt K, Gabriel LS. Continuing Competence Trends of Occupational Therapy Practitioners. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017; 5(l): 4. https://doi.org/l0.l5453/2l68-6408.l268 [ Links ]

27. Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, Boucher A. CanMEDS 2015. Physician Competency Framework Series I. 2015.[Internet] <http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/canmeds/re-sources/publications> (12 May 2018) [ Links ]

28. Hordichuk CJ, Robinson AJ, Sullivan TM. Conceptualising Professionalism in Occupational Therapy through a Western lens. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2015; 62(3): 150-9. https://doi.org/l0.1111/l440-l630.l2204 [ Links ]

29. Gupta J, Taff SD. The Illusion of Client-Centred Practice. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 22(4): 244-51. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1020866 [ Links ]

30. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002; 56: 609-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.682006 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ravashni Govender

ravashni.govender@gmail.com

* In order to uphold the conditions of ethical clearance and gatekeeper permissions for this study, employment details are withheld as per conditions agreed upon prior to commencement of this study.

1 *pseudonym